Abstract

Cobweb disease is a fungal disease that can cause serious damage to edible mushrooms worldwide. To investigate cobweb disease in Morchella sextelata in Guizhou Province, China, we isolated and purified the pathogen responsible for the disease. Through morphological and molecular identification and pathogenicity testing on infected M. sextelata, we identified Cladobotryum mycophilum as the cause of cobweb disease in this region. This is the first known occurrence of this pathogen causing cobweb disease in M. sextelata anywhere in the world. We then obtained the genome of C. mycophilum BJWN07 using the HiFi sequencing platform, resulting in a high-quality genome assembly with a size of 38.56 Mb, 10 contigs, and a GC content of 47.84%. We annotated 8428 protein-coding genes in the genome, including many secreted proteins, host interaction-related genes, and carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) related to the pathogenesis of the disease. Our findings shed new light on the pathogenesis of C. mycophilum and provide a theoretical basis for developing potential prevention and control strategies for cobweb disease.

Keywords: Morchella sextelata, cobweb disease, identification, Cladobotryum mycophilum, whole genome sequencing

1. Introduction

Morels (Morchella spp.) are a rare edible and medicinal mushroom known for their high nutritional value, including high protein and low-fat content, and rich variety of essential minerals, vitamins, and other nutrients. They also have antioxidant, anti-tumor, and immune-regulating properties, making them a promising source of medicinal benefits with broad development prospects [1,2,3,4,5,6].

Wild morels are mainly found in Yunnan, Sichuan, Gansu, Heilongjiang, and Xinjiang provinces in China [7]. Morels have been cultivated for over 130 years, with the cultivation area expanding from 6.67 ha in 2003 to 10,050 ha in 2020 [7]. As of today, morels are cultivated almost everywhere in China, except for Hainan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao, and have become an important tool for poverty alleviation and rural revitalization [8].

In recent years, the cultivation and scale of morels have increased, but this has also led to new challenges. These challenges include changing and abnormal weather patterns and disease problems resulting from improper cultivation management. These factors have become important reasons for serious production losses or crop failure [9], which significantly hinder the stable development of the morel industry. Currently, reported morel diseases mainly include white mold disease caused by Paecilomyces penicillatus infection [9], handle rot disease caused by Fusarium sp. infection [10], rot disease caused by Lecanicillium aphanocladii infection [11], and cobweb disease caused by Cladobotryum protrusum infection [12]. These diseases have greatly reduced the economic benefits of the morel industry.

Cobweb disease is caused by the Cladobotryum genus, which is a significant threat to edible mushroom cultivation worldwide [13]. This disease can cause production losses of up to 40% [14] and is considered one of the most destructive diseases of edible mushrooms [15]. Different species of Cladobotryum can infect a wide range of cultivated edible fungi, causing varying degrees of damage. For example, C. dendroides mainly infects Lentinus edodes [16] and Agaricus bisporus [17], while C. varium (teleomorph sexuales: Hypomyces aurantius) mainly infects Hypsizygus marmoreus [18], Flammulina filiformis [19], and Oudemansiella raphanipies [20]. C. semicirculare mainly infects Ganoderma tsugae [21], C. cubitense mainly infects Auricularia polytricha [22], and C. protrusum mainly infects Coprinus comatus [23] and M. importuna [12]. C. mycophilum (teleomorph sexuales: H. odoratus) has been reported to infect a relatively wide range of edible mushrooms, including A. bisporus [24], G. lucidum [25], and Pleurotus eryngii [26,27]. Although the pathogen responsible for cobweb disease in M. importuna in Shandong Province was identified as C. protrusum [12], our investigation of the incidence of cobweb disease in M. sextelata in Guizhou suggests that there may be more than one pathogen causing this disease.

High-throughput sequencing technology has become more prevalent in recent years due to its rapid development and decreasing costs. This has led to increased exploration and study of fungal genomic information. Recently, the genomes of two species of Cladobotryum, C. protrusum and C. dendroides [28,29], commonly responsible for causing cobweb disease in edible mushrooms, have been sequenced. Analysis of these genomes has revealed a large number of pathogenic genes, including those involved in peptidase, carbohydrate-active enzyme, cytochrome P450 enzyme, and secondary metabolites such as mycotoxins and pigments [28,29]. These genomic findings have provided valuable insights into identifying genes related to growth, evolution, host-pathogen interactions, and pathogenicity in Cladobotryum fungi.

This study aimed to identify the pathogen responsible for cobweb disease in M. sextelata in Guizhou Province, China. We identified the pathogen of cobweb disease as C. mycophilum and sequenced its whole genome using the HiFi sequencing platform. This was the first time the genome of C. mycophilum had been sequenced. The main objectives of the study were to identify the pathogen causing cobweb disease and to provide a high-quality reference genome for comparative genomic studies of the fungal family Hypocreaceae and other mycoparasites. Additionally, we analyzed the genes responsible for the pathogenicity and fungal parasitism of C. mycophilum. The high-quality genome assembly of C. mycophilum will expand the genome database and aid in comparative genomic studies. This study’s findings will help analyze how cobweb disease develops and spreads, leading to more effective control strategies against the disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Surveys

In June 2022, a field survey was conducted to investigate the incidence and symptoms of cobweb disease in M. sextelata during the off-season at a forest cultivation base in Weining County, Bijie City, Guizhou Province, China. A total of 300 M. sextelata fruiting bodies were investigated in triplicate, with 100 fruiting bodies being studied in different M. sextelata arch sheds. Additionally, 10 M. sextelata fruiting bodies with typical cobweb disease symptoms were collected for further studies. The aim was to determine the incidence and symptoms of the disease and disease occurrence period as well as to isolate and culture the pathogen responsible for the disease.

2.2. Isolation and Purification of the Fungal Pathogens

To isolate and purify the fungal pathogens responsible for cobweb disease in M. sextelata, small tissue blocks were taken from the healthy junction of new fruiting bodies displaying cobweb disease symptoms. Before inoculating these tissue blocks onto PDA plates, they were disinfected with a 75% ethanol solution for 30 s, followed by a 1% sodium hypochlorite solution, and washed three times with sterile water. The plates were then cultured in a dark 25 °C incubator. Once the mycelium of the fungi had grown, single spores were isolated from these cultures to obtain pure cultures of the pathogen.

2.3. Morphological and Molecular Biological Characterization of Pathogens

2.3.1. Morphological Identification

The purified pathogens were inoculated on PDA plates and cultured in the dark at 25 °C for 5, 10, and 20 days to observe the morphological characteristics of the fungal colony, including the appearance of the mycelium, conidiophores, conidia, and chlamydospores. In addition, the sizes of 60 conidia were measured. The morphological identification of the fungal pathogens followed the method described in a book titled “The Genera of Hyphomycetes” [30].

2.3.2. Molecular Biology Identification

Genomic DNA was extracted using the novel plant genomic DNA extraction kit NuClean Plant Genomic DNA Kit (CWBIO, Beijing, China), and the genome extraction quality was determined by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Primers ITS4 and ITS5 [31], EF1-983f [32] and EF1-2218r [33], and RPB2-5f and RPB2-7cR [34] were used for PCR amplification. PCR amplifying system (25 μL): ddH2O 14.5 μL, 5 μL 5 × TranStart Faspfu Buffer, dNTPs (2.5 mM) 2 μL, 1 μL forward primer, 1 μL reverse primer, 1 μL genomic DNA, and 0.5 μL TranStart Faspfu DNA Polymerase (5 U/μL). PCR reaction conditions: 95 °C pre-denaturation for 5 min, followed by 95 °C denaturation for 30 s, 55 °C (ITS), 59 °C (TEF1), and 58 °C (RPB2) annealing for 30 s, 72 °C extension for 1 min, a total of 30 cycles, and finally 72 °C extension for 5 min. The PCR amplification products were confirmed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and then sent to Beijing Qingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) for sequencing.

The sequencing results were subjected to BLAST sequence analysis in GenBank (NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.gov (accessed on 12 November 2022)), the correct sequences of the same and similar species as the pathogens were selected from GenBank and downloaded, and the multiple sequence comparison was performed by BioEdit v7.2.5 software [35]. Phylogenetic analyses were performed based on ITS, TEF1, and RPB2 sequence data. Maximum likelihood analysis (ML) was performed using the GTR + G + I model of RAxML-8.0.26 [36], and Bayesian inference (BI) analysis was performed using MrBayes v3.2 [37] to determine the posterior probability (PP). The identification of the pathogen strains was determined according to the phylogenetic relationship. The gene sequences used to construct the phylogenetic tree are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences and GenBank accession numbers of Cladobotryum and Hypomyces isolates used in the phylogenetic analyses.

| Species | Strain | Genbank Accession Numbers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | TEF | RPB2 | ||

| C. asterophorum | CBS 676.77 | FN859395 | FN868712 | FN868649 |

| C. cubitense | G.A. m643.w | FN859397 | FN868714 | FN868651 |

| TFC 2007-13 | AM779857 | FN868715 | FN868652 | |

| C. heterosporum | CBS 719.88 | FN859398 | FN868716 | FN868653 |

| C. indoafrum | FSU 5807 | FN859399 | FN868717 | FN868654 |

| TFC 03-7 | FN859400 | FN868718 | FN868655 | |

| TFC 201277 | FN859401 | FN868719 | FN868656 | |

| C. multiseptatum | CBS 472.71 | FN859405 | FN868723 | FN868659 |

| C. mycophilum | BJWN07 | OP714368 | OP759638 | OP718561 |

| BJWN12 | OP714369 | OP759639 | OP718562 | |

| BJWN24 | OP714393 | OP759640 | OP718563 | |

| C. paravirescens | TFC 97-23 | FN859406 | FN868724 | FN868660 |

| C. penicillatum | CBS 407.80 | FN859407 | FN868725 | FN868661 |

| C. protrusum | CBS 118999 | FN859408 | FN868726 | FN868662 |

| FSU 5044 | FN859409 | FN868727 | FN868663 | |

| FSU 5077 | FN859410 | FN868728 | FN868664 | |

| C. purpureum | CBS 154.78 | FN859415 | FN868733 | FN868669 |

| C. rubrobrunnescens | CBS 176.92 | FN859416 | FN868734 | FN868670 |

| C. semicirculare | CBS 705.88 | FN859417 | FN868735 | FN868671 |

| TFC 03-3 | FN859418 | FN868736 | FN868672 | |

| C. tenue | CBS 152.92 | FN859420 | FN868738 | FN868674 |

| H. aconidialis | TFC 201215 | FN859455 | FN868774 | FN868710 |

| H. armeniacus | TFC 02-86/2 | FN859424 | FN868742 | FN868678 |

| H. aurantius | TFC 95-171 | FN859425 | FN868743 | FN868679 |

| H. australasiaticus | TFC 99-95 | FN859427 | FN868745 | FN868680 |

| TFC 03-8 | FN859428 | FN868746 | FN868681 | |

| H. australis | TFC 07-18 | AM779860 | FN868747 | FN868682 |

| H. dactylarioides | CBS 141.78 | FN859429 | FN868748 | FN868683 |

| H. gabonensis | TFC 201156 | FN859430 | FN868749 | FN868684 |

| H. khaoyaiensis | G.J.S. 01-304 | FN859431 | FN868750 | FN868685 |

| H. lactifluorum | TAAM 170476 | FN859432 | FN868751 | EU710773 |

| H. odoratus | C.T.R. 72-23 | FN859433 | FN868752 | FN868687 |

| G.A. m329 | FN859434 | FN868753 | FN868688 | |

| TFC 03-16 | FN859437 | FN868756 | FN868691 | |

| H. rosellus | TFC 99-229 | FN859441 | FN868759 | FN868695 |

| TFC 01-25 | FN859442 | FN868760 | FN868696 | |

| TFC 200847 | FN859438 | FN868761 | FN868692 | |

| H. samuelsii | CBS 536.88 | FN859444 | FN868763 | FN868698 |

| G.J.S. 96-41 | FN859448 | FN868766 | FN868702 | |

| InBio 3-233 | FN859450 | FN868768 | FN868704 | |

| H. subiculosus | TFC 97-166 | FN859452 | FN868770 | EU710776 |

| H. virescens | G.A. i1906 | FN859454 | FN868772 | FN868708 |

Note: Isolates in bold are of the present study.

2.4. Pathogenicity Determination

To determine the pathogenicity of the isolated and purified pathogen strains, they were grown on PDA plates in a constant temperature dark environment at 25 °C for 15 days. After collecting the conidia, a spore suspension was prepared by diluting them with sterile water to a concentration of 5 × 106 spores/mL. This suspension was sprayed onto the foundation soil of healthy M. sextelata fruiting bodies in a controlled cultivation shed with a temperature range of 10~18 °C, and the relative humidity was 85~95%.

Nine fresh and healthy M. sextelata fruiting bodies were inoculated with a 10-µL droplet of the conidial suspension of each pathogen strain. In contrast, fresh M. sextelata fruiting bodies inoculated with sterile water were used as controls for each experiment. The disease incidence was observed and recorded daily in both inoculated and uninoculated fruiting bodies. The pathogen was reisolated from new symptomatic M. sextelata fruiting bodies to fulfil Koch’s postulate. This pathogenicity test was repeated three times.

2.5. Genome Sequencing and Assembly

The genomic DNA of C. mycophilum BJWN07 was extracted using the SDS method [38]. The DNA was assessed for quantity, quality, and integrity using agarose gel electrophoresis, Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Foster City, CA, USA), and Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). For PacBio sequencing, the DNA was sheared with Covaris g-TUBE (Covaris, MA, USA) into target fragment size, and DNA damage and fragments were repaired. The DNA fragment was then purified and selected using AMpure PB magnetic beads (PacBio, CA, USA) to construct the SMRT Bell Library. The BluePippin system (SageScience, MA, USA) was used to select an insert size of 20 kb. The SMRT Bell library was sequenced on the PacBio RSII platform (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA).

For Illumina sequencing, the DNA library was constructed with an insert size of 350 bp using the NEBNext® Ultra™ DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA). The sequencing libraries were analyzed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Once the library inspection was qualified, the whole genome was sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq PE150 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). High-precision HiFi reads were generated and assembled using the CCS software. The polished consensus sequences were corrected using Illumina sequencing data for the final assembly. All sequencing and library preparation was carried out at the Beijing Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

2.6. Genome Component Prediction

We used seven databases GO (Gene Ontology) [39], KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) [40,41], KOG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups) [42], NR (Non-Redundant Protein Database databases) [43], TCDB (Transporter Classification Database) [44], P450, and Swiss-Prot [45] to predict gene functions. We performed a whole genome BLAST search with an E-value lower than 1e-5 and a minimum alignment length percentage larger than 40% against these seven databases. Additionally, we used Signal P [46] to predict secretory proteins and the antiSMASH tool [47] to analyze secondary metabolism gene clusters. For pathogenic fungi, we added pathogenicity using the PHI (Pathogen Host Interactions) [48] and DFVF (database of fungal virulence factors databases). The carbohydrate-active enzymes were predicted using the dbCAN web server (https://bcb.unl.edu/dbCAN2/) (accessed on 16 November 2022) [49].

2.7. Phylogenomics Analysis of C. mycophilum

The protein-coding genes from 14 species, including C. mycophilum, H. rosellus [29], C. protrusum [28], H. perniciosus [50], Trichoderma longibrachiatum [51], Neurospora crassa [52], Magnaporthe grisea [53], Pyricularia oryzae [54], Fusarium solani, F. oxysporum [55], Tolypocladium inflatum [56], T. virens [57], T. reesei [58], and Clonostachys rosea [59] (Table S1), were compared using BLASTP with an E-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5. The OrthoMCL (v.2.0.9) [60] method was then used to identify direct orthologous groups. Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis was performed using RAxML-8.0.26 [36] with 1000 bootstrap repeats.

3. Results

3.1. Cobweb Disease Symptoms and Incidence

Cobweb disease symptoms were observed in a morel farm located in Weining County, Bijie City, Guizhou Province, China. The disease incidence ranged from 5% to 60%. The most common symptoms observed were a small amount of white flocculate aerial mycelium on the surface of the stipe (Figure 1A), thick white mycelium covering the fruiting body (resembling cotton catkins), and the fruiting body becoming soft (Figure 1B). In severe infections, the entire fruiting body was covered with white hyphelium, the stipe was lodged, and, eventually, the whole mushroom died (Figure 1C). During the later stage of the infection, the pathogens produced numerous conidia, and the mycelium changed from white to pink (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Field symptoms and pathogenicity of M. sextelata cobweb disease. (A–D) Field symptoms at different stages of the disease. (A): initial disease symptoms; (B,C): middle disease symptoms; (D): late disease symptoms. (E–H) Pathogenicity test where a spore suspension with a concentration of 5 × 106 spores/mL was sprayed. (E): The symptoms of M. sextelata fruiting bodies 7 days after inoculation; (F): after 12 days of inoculation M. sextelata fruiting bodies stopped developing and suffered from soft rot; (G): after 15 d of inoculation, the fruiting bodies collapsed and died; (H): control, no disease symptoms appeared after 15 d of inoculation with sterile water.

3.2. Identification of Pathogen

3.2.1. Morphological Characterization of the Pathogen

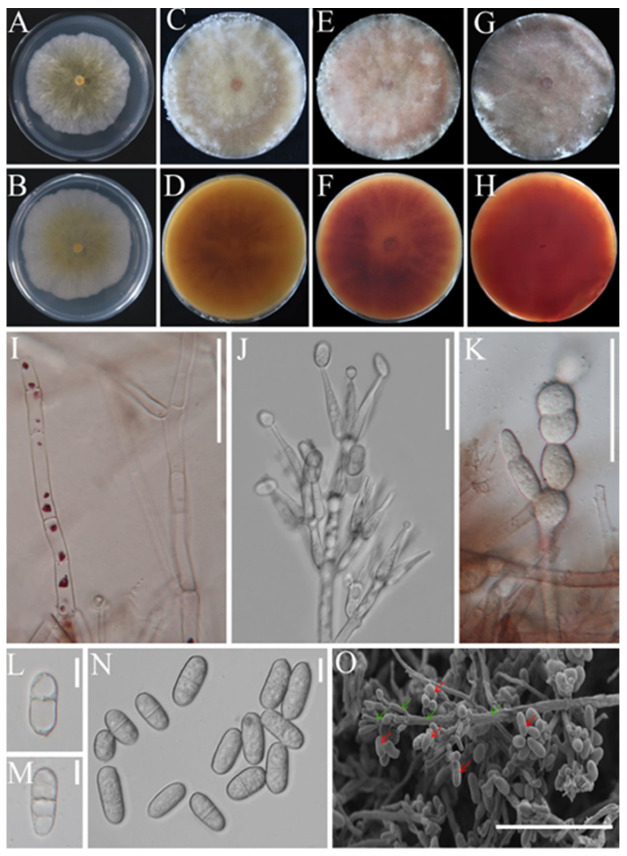

To begin with, strains BJWN07, BJWN12, and BJWN24 showed consistent morphological and micromorphological features. These strains grew rapidly on PDA plates after 5 days of cultivation and formed colonies that reached 60–75 cm in diameter with abundant aerial hyphae that resembled cotton wool (Figure 2A,B). Initially, the colonies were white, but over time they turned yellow from the center and became progressively darker, reaching a dark yellow color after 25 days (Figure 2C,D), pink after 50 days (Figure 2E,F), and dark pink after 60 days (Figure 2G,H). The conidial stem had a septum and branches that were either broom or round in shape (Figure 2I,J). The fungus produced chlamydospores, and cells expanded into a string (Figure 2K). The conidia were colorless, oval-shaped, blunt round at both ends, and measured 17.2–19.8 × 8.4–9.3 μm. They had 1–3 diaphragms and were slightly bent at the diaphragm (Figure 2L–O).

Figure 2.

Colony and microscopic characteristics of C. mycophilum. (A,B): Depict the colony on PDA after 5 days and the reverse side, respectively; (C,D): depict the colony on PDA after 25 days and the reverse side, respectively; (E,F): depict the colony on PDA after 50 days and the reverse side, respectively; (G,H): depict the colony on PDA after 60 days and the reverse side, respectively. (I,J): Conidiophores, bar = 50 μm; (K): chlamydospores, bar = 50 μm; (L–N): conidiophores, bar = 10 μm; (O): conidiophores (green arrow) and conidiophores (red arrow) under the scanning electron microscope, bar = 100 μm.

3.2.2. Molecular Identification of the Pathogen

The internal transcribed spacer (ITS), TEF1, and RNA polymerase II largest subunit (RPB2) regions of three strains, BJWN07, BJWN12, and BJWN24, were amplified by PCR and sequenced. The ITS fragment length was between 562–566 bp (GenBank accession numbers OP714368, OP714369, and OP714393), the TEF1 fragment length was between 927–939 bp (GenBank accession numbers OP759638, OP759639, and OP759640), and the RPB2 fragment length was between 1118–1121 bp (GenBank accession numbers OP718561, OP718562, and OP718563). After searching and comparing the sequences with the NCBI database BLAST, it was found that they were 100% similar to the accession numbers MH185858 (ITS), HF911622 (TEF1), and OK458561 (RPB2), respectively.

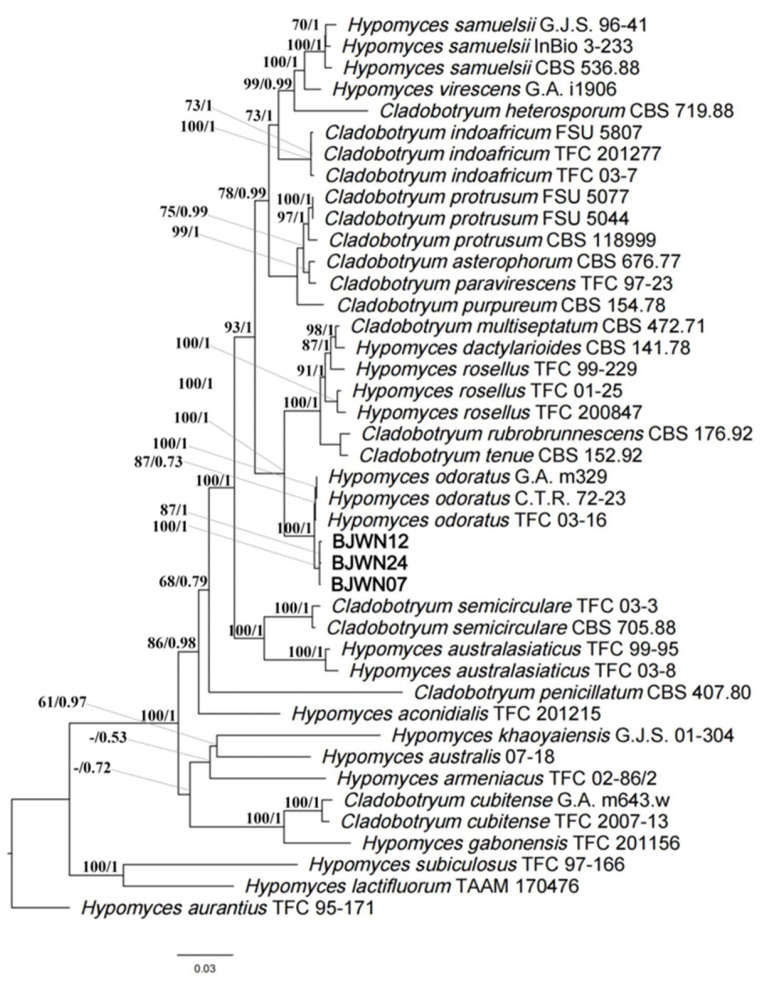

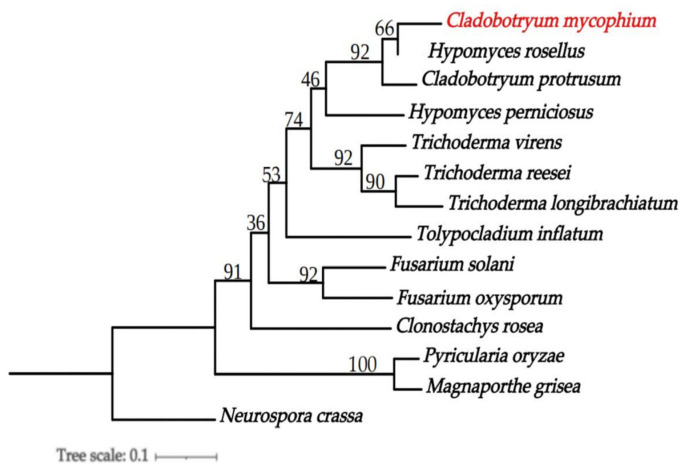

Next, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the rDNA ITS regions and partial sequences of TEF1 and RPB2 genes. The sequences of strains BJWN07, BJWN12, and BJWN24 were found to be in the same branch as H. odoratus (asexual type: C. mycophilum) (Figure 3) and were most closely related with high statistical support (ML/BI: 100/1). The strains BJWN07, BJWN12, and BJWN24 were identified as C. mycophilum based on morphological and molecular phylogenetic analyses.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree based on rDNA ITS regions and partial sequences of TEF1 and RPB2 genes sequences for our three strains and selected reference isolates retrieved from GenBank of Hypomyces/Cladobotryum. Maximum likelihood (ML) values > 50% and Bayesian inference (BI) values > 0.50 are shown next to topological nodes and separated by “/”. Bootstrap values < 50% and BI values < 0.50 are labeled with “-”. H. aurantius was used as an outgroup. Newly generated sequences are indicated in bold.

3.3. Pathogenicity Determination

The pathogenicity of three strains (BJWN07, BJWN12, and BJWN24) was investigated by inoculating healthy fresh soil with spore suspensions at the base of the stipe (Figure 1E). After seven days, white, cobweb-like mycelia appeared, infecting the stipe’s base and gradually spreading to the cap (Figure 1F). The fruiting body became soft, and the mycelium covered it entirely, leading to lodging and death (Figure 1G). These symptoms were consistent with those observed under natural conditions. Inoculation with sterile water had no effect (Figure 1H). Koch’s postulates were verified, and molecular identification confirmed the presence of the same pathogen.

3.4. Genome Sequencing and Assembly

The representative strain BJWN07 was sequenced using the HiFi sequencing platform, generating a total of 4.91 Gb of data with a sequencing depth of approximately 130×. The assembled genome is 38.56 Mb, consisting of 10 contigs, with a GC content of 47.84% and an N50 value of 5.42 Mb. The genome assembly resulted in the identification of 8428 protein-coding sequences (CDS) and 330 RNA genes, including 264 tRNA, 53 5S rRNA, 6 18S rRNA, and 7 28S rRNA genes (Table 2). The prediction of repeated DNA sequences in the BJWN07 genome identified 2198 long terminal repeats, which make up 0.4237% of the genome, with a total length of 171,302 bp. Additionally, there were 2239 DNA transposons that constituted 0.7662% of the genome, with a total length of 309,760 bp. The genome also contained 977 scattered repeats that added up to 83,955 bp, representing 0.2077% of the genome. Among these scattered repeats were 47 short scattered repeats, 104 rolling rings, and 70 unknown scattered repeats. Tandem repeat prediction identified 11,990 tandem repeats with a total length of 492,550 bp, making up 1.2183% of the genome. The genome also contained 7609 small-satellite DNA sequences, which added up to 311,395 bp, representing 0.7702% of the genome. In addition, there were 3071 microsatellite DNA sequences with a total length of 118,888 bp, representing 0.2941% of the genome.

Table 2.

Cladobotryum mycophilum BJWN07 genome features.

| Terms | BJWN07 |

|---|---|

| The number of reads | 300,757 |

| Data size (bp) | 5,272,956,422 |

| Minimum sequencing read length (bp) | 78 |

| N50 Contig Length (bp) | 18,317 |

| Maximum sequencing read length | 49,868 |

| Genome size (Mb) | 38.56 |

| Number of contigs | 10 |

| GC content | 47.84% |

| Coverage | 130× |

| Number of coding genes | 8428 |

| The number of RNAs | 330 |

3.5. Gene Function Annotation

A total of 8428 protein-coding genes were predicted. The protein-coding genes had an average length of 11.43 Mb, representing 29.64% of the total gene length. These protein-coding genes were annotated in various databases such as GO, KEGG, KOG, NR, Pfam, Swiss-Prot, TCDB, CAZy, Secretory_Protein, cytochrome P450, PHI, and DFVF databases (Table 3). Among these databases, the Nr database annotated 7766 protein sequences, which had the closest matches to Escovopsis weberi (1344), T. arundinaceum (1182), T. harzianum (572), T. virens (453), and T. asperellums (419) (Figure S1).

Table 3.

Number of genes annotated in each database for the coding gene.

| Database Used for Gene/Protein Annotation | Number of Genes |

|---|---|

| Nr | 7766 |

| GO | 5683 |

| KEGG | 7447 |

| KOG | 1964 |

| Pfam | 5683 |

| SwissProt | 3049 |

| TCDB | 551 |

| CAZy | 499 |

| Secretory_Protein | 661 |

| P450 | 155 |

| PHI | 1429 |

| DFVF | 443 |

The GO functional category predicted a total of 5683 genes, which accounted for 67% of the total predicted genes (Table S2). The top 10 most abundant function categories were “catalytic activity”, “metabolic process”, “binding”, “cellular process”, “cell”, “cell part”, “localization”, “establishment of localization”, “organelle”, and “biological regulation” (Figure S2).

The KEGG database was used to map the predicted genes, and 7447 gene models (87.80% of the total number of genes) were functionally classified. Several categories related to metabolism and membrane transport were highly enriched, including “Global and overview maps” (876), “Translation” (298), “Carbohydrate metabolism” (278), “Transport and catabolism” (269), “Amino acid metabolism” (246), “Signal transduction” (232), and “Folding, sorting and degradation” (223) (Figure S3).

In the KOG category, there were 1964 genes (Figure S4). The category with the highest number of genes was “Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones” with 222 genes, followed by “General function prediction only” with 210 genes, “Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis” with 208 genes, “Energy production and conversion” with 166 genes, and “Amino acid transport and metabolism” with 166 genes.

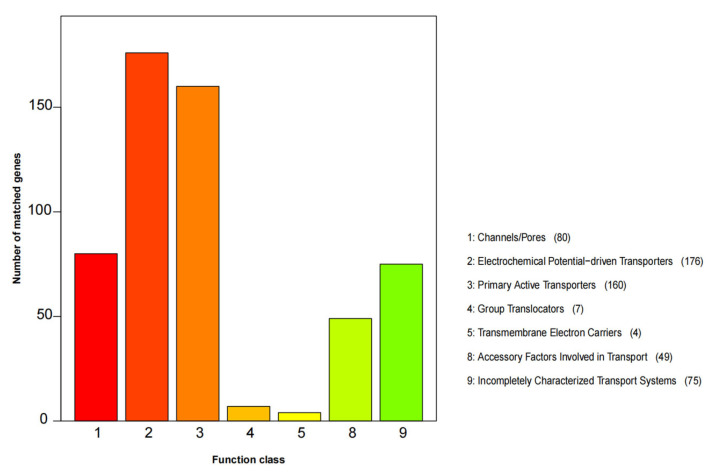

The TCDB database annotation assigned 551 protein-coding genes to seven functional categories, including “Channels/pores”, “Electrochemical Potential-driven Transporters”, “Primary Active Transporters”, “Group Translocators”, “Transmembrane Electron Carriers”, “Accessory Factors Involved in Transport”, and “Incompletely Characterized Transport Systems” (Figure 4). The categories with the highest number of genes were “Electrochemical Potential-driven Transporters” with 176 genes and “Primary Active Transporters” with 160 genes.

Figure 4.

TCDB function classification of C. mycophilum BJWN07.

The BJWN07 genome contained 499 annotated CAZymes, which included various families of carbohydrate-binding molecules (CBM), carbohydrate esterases (CE), glycoside hydrolases (GHs), glycosyltransferases (GTs), polysaccharide lyases (PLs), and auxiliary activities (AA) (Table 4). The GHs family had the most genes, with 249 genes accounting for 49.90% of the total number of CAZymes. The next largest family was the GTs family, with 111 genes accounting for 22.16% of the total number of CAZymes. Among the GHs families, GH18 had the highest number of genes at 31, while in the GTs family, GT31 had the highest number of genes at 15.

Table 4.

Carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation results of C. mycophilum BJWN07.

| Classification | Number |

|---|---|

| Carbohydrate-binding molecule (CBM) | 50 |

| Carbohydrate Esterase (CE) | 28 |

| Glycoside hydrolases (GHs) | 249 |

| Glycosyltransferases (GTs) | 111 |

| Polysaccharide lyases (PLs) | 9 |

| Auxiliary activities (AA) | 52 |

| Total | 499 |

The antiSMASH analyses identified 78 secondary metabolic gene clusters and 773 secondary metabolic genes (Table 5). Of these, 23 clusters were identified as type 1 polyketide synthase (T1PKS) gene clusters containing 229 genes, accounting for 29.62% of the total secondary metabolic genes. The analysis also identified 18 non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) gene clusters containing 175 genes, representing 22.64% of the total secondary metabolic genes. Additionally, 12 terpene gene clusters were identified, containing 59 genes. There were eight NRPS-T1PKS gene clusters containing 79 genes and seven NRPS-like gene clusters containing 69 genes. Overall, this analysis provides insight into the metabolic potential of C. mycophilum BJWN07 and the types of secondary metabolites it may produce.

Table 5.

Secondary metabolic gene cluster and gene number statistics.

| Clusters | Clusters_Number | Gene_Number |

|---|---|---|

| T1PKS | 23 | 229 |

| siderophore | 1 | 2 |

| NRPS | 18 | 175 |

| T1PKS, terpene | 2 | 25 |

| NRPS-like, T1PKS | 2 | 21 |

| NRPS, NRPS-like, T1PKS | 4 | 85 |

| NRPS, T1PKS | 8 | 79 |

| NRPS, NRPS-like, T1PKS, indole, terpene | 1 | 29 |

| NRPS-like | 7 | 69 |

| terpene | 12 | 59 |

| Total | 78 | 773 |

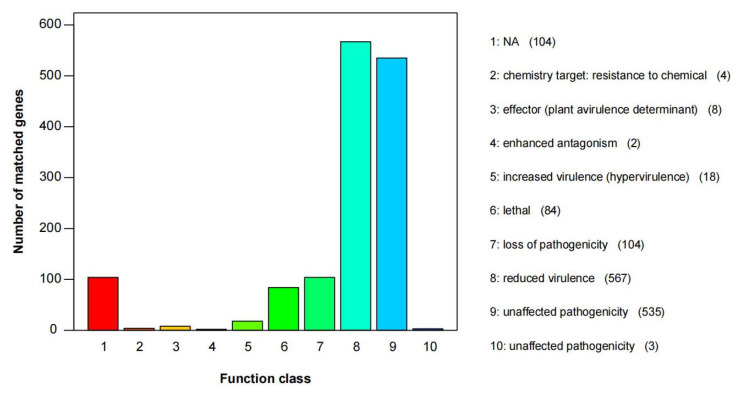

Annotation of the genome by the PHI database identified 1429 proteins related to pathogenicity, representing 16.85% of all the encoded proteins in the genome (Figure 5). Among these, the most abundant category is “reduced virulence,” which includes 567 proteins and accounts for 39.68% of the total candidate pathogenicity-related proteins. The second most abundant category is “unaffected pathogenicity,” which includes 535 proteins and accounts for 37.44% of the total candidate pathogenicity-related proteins. Additionally, 104 proteins belong to the “loss of pathogenicity” category, and 84 proteins belong to the “lethal” category.

Figure 5.

PHI functional annotation of C. mycophilum BJWN07.

3.6. Phylogenomics Analysis of C. mycophilum

From the 14 species, a total of 16,159 direct orthologous groups were identified. To construct a phylogenetic tree, 1731 single-copy orthologous genes were used. The analysis revealed that C. mycophilum BJWN07, H. rosellus (asexual type was C. dendroides), and C. protrusum belong to the same genus. However, C. mycophilum BJWN07 is distantly related to the outgroup N. crassa (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree of C. mycophilum and 13 other fungal species. Maximum likelihood (ML) values > 50% were placed close to topological nodes. The tree was rooted to N. crassa. The newly sequenced genome is indicated in red.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated cobweb disease affecting M. sextelata in Weining County, Bijie City, Guizhou Province, China. Our findings revealed that the disease had a median incidence of 15%. The causal agent was identified as C. mycophilum, which was previously unreported as causing cobweb disease in M. sextelata in China or globally. Cobweb disease, caused by different Cladobotryum species [61,62,63], has been observed in many countries, including China [12,22,25,64,65], Korea [26,63], South Africa [24], and Spain [27,66,67], causing significant economic losses in the edible mushroom industry [13,15]. C. mycophilum has a broad host range and produces a large number of conidia in the form of dry powder in the later stages of infection, making it easily transmitted by wind and humidity, resulting in outbreaks and epidemics [26,27,61,62,63]. Due to the expansion of the morel industry and inadequate adoption of good agricultural practices, cobweb disease has become a significant challenge in various cultivation areas in Guizhou Province. Therefore, we recommend a comprehensive investigation of cobweb disease in the primary morel cultivation areas in China, particularly Guizhou Province, to identify pathogen species and their genetic diversity in different regions. This approach may provide a theoretical basis for the scientific prevention and control of cobweb disease, which is crucial for sustaining the morel industry.

The genome size of C. mycophilum assembled in this study is 38.56 Mb, which is the first high-quality genome of C. mycophilum published and similar to those of the other two species of the same genus reported previously viz C. protrusum (39.09 Mb) [28] and C. dendroides (36.69 Mb) [29]. However, the genome of another species in the same genus, H. perniciosus (44.0 Mb) [50], is larger and contains a higher proportion of repeated DNA sequences (25.27%). These findings suggest that genome size and repeat sequences can vary across species within the same genus, which could have implications for the evolution and ecology of these fungi [68].

During the early stages of infection by pathogenic fungi, the use of cell wall degrading enzymes to destroy the host cell wall is crucial for successful host infection [69]. The number of CAZymes in the genome of C. mycophilum is 499, which is higher than that of C. protrusum (412) [28] and C. dendroides (327) [29], possibly contributing to C. mycophilum’s ability to infect more hosts. The genome of C. mycophilum contains 30 GH18 genes, the most abundant type of the GH family. This family of genes produces a chitinase-like protein that aids in chitin degradation [70]. Since the mushroom cell wall primarily consists of chitin, we speculate that a large number of GH18 family members in the C. mycophilum genome are mainly utilized for the early infection stage of mushroom cell wall degradation, enabling C. mycophilum to invade mushroom cells and cause diseases.

Furthermore, the C. mycophilum genome also contains five GH75 genes that are associated with chitin degradation [71]. C. mycophilum genome contains 111 CAZymes genes encoding GT, the most among the family Hypocreaceae, with GT31 (15) being the most abundant. These GT gene families are mainly involved in chitin synthesis, cell wall biosynthesis, and glycosylation [50]. Therefore, the results suggest that CAZymes play a significant role in C. mycophilum’s ability to infect hosts.

Pathogenic fungi produce various secondary metabolites, including toxins, pigments, antibiotics, repellents, insecticides, anti-tumor, and cholesterol-lowering substances. In the case of C. mycophilum BJWN07, its secondary metabolite genes produce toxins, pigments, and compounds with potential resistance to harsh environmental conditions. One of these genes is aur1, which produces aurofusarin and possibly the red pigment in C. mycophilum. This pigment was first discovered in another fungus, F. graminearum [72]. There are also many unknown secondary metabolites in C. mycophilum BJWN07, suggesting that this strain has the potential to produce bioactive compounds.

When a pathogen infects a host, it produces a large number of virulence factors, including effector proteins, which play a crucial role in pathogenesis [73,74]. The genome of C. mycophilum BJWN07 contains 661 genes of secreted proteins, 1429 pathogen and host interaction-related genes, and 499 carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZy) associated with the fungal host cell wall. All 1429 candidate disease-related proteins contained the PHI-base, which provides a valuable genetic resource for subsequent functional genomics research and in-depth investigation of disease-related proteins. These findings can aid in analyzing the pathogenic mechanism of C. mycophilum infection on mushrooms and developing effective prevention and control strategies for cobweb disease.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the morel cultivation base in Weining County, Bijie City, Guizhou Province, China, for their assistance in disease investigation and sample collection.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jof9040411/s1. Figure S1: Predicted proteins from C. mycophilum BJWN07 genome to the NCBI non-redundant proteins database among different bacteria species. Figure S2: GO functional classification of C. mycophilum BJWN07. Figure S3: Classification of KEGG metabolic pathways in C. mycophilum BJWN07. Figure S4: KOG functional classification of C. mycophilum BJWN07. Table S1: Genome features and background information of C. mycophilum and other representative fungi analyzed in this study. Table S2: The Number of Genes Predicted by GO database in the Genome of C. mycophilum BIWN07.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and J.K.; methodology, Y.C.; software, F.L.S.; validation, Z.L., Y.L. (Yongzhong Lu) and J.K.; formal analysis, Z.L. and F.L.S.; investigation, Y.C. and Z.L.; data curation, Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L., F.L.S. and J.K.; supervision, J.K.; project administration, Z.L. and J.K.; funding acquisition, Y.L. (Yu Li), Z.L. and Y.L. (Yongzhong Lu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This paper’s genome sequence data and assembly are linked with NCBI BioProject: PRJNA917475 and BioSample: SUB12509998.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Guizhou Provincial Department of Education Young Science and Technology Talent Growth Project (grant No. Qian Jiao Ji [2022] 119); Guizhou University Natural Science Special (Special Post) Scientific Research Fund Project (grant No. Guida Tegang Hezi (2022) 17); Strategic Pilot Science and Technology Project of Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant No. XDA28080304); The National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant No. 2021YFD1600401); and The Natural Science Foundation of Guizhou Province (grant No. Qian Ke He Zhi Cheng (2021) Generally 200).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Zhang Q., Wu C., Sun Y., Li T., Fan G. Cytoprotective Effect of Morchella esculenta Protein Hydrolysate and Its Derivative Against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2019;69:255–265. doi: 10.31883/pjfns/110134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang Y., Chen J., Li F., Yang Y., Wu S., Ming J. Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Modified Polysaccharides Originally Isolated from Morchella angusticepes Peck. J. Food Sci. 2019;84:448–456. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu C., Sun Y., Mao Q., Guo X., Li P., Liu Y., Xu N. Characteristics and Antitumor Activity of Morchella esculenta Polysaccharide Extracted by Pulsed Electric Field. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:E986. doi: 10.3390/ijms17060986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z., Wang H., Kang Z., Wu Y., Xing Y., Yang Y. Antioxidant and Anti-Tumour Activity of Triterpenoid Compounds Isolated from Morchella Mycelium. Arch. Microbiol. 2020;202:1677–1685. doi: 10.1007/s00203-020-01876-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cui H.-L., Chen Y., Wang S.-S., Kai G.-Q., Fang Y.-M. Isolation, Partial Characterisation and Immunomodulatory Activities of Polysaccharide from Morchella esculenta: Properties of Polysaccharide from M. esculenta. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011;91:2180–2185. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wen Y., Peng D., Li C., Hu X., Bi S., Song L., Peng B., Zhu J., Chen Y., Yu R. A New Polysaccharide Isolated from Morchella importuna Fruiting Bodies and Its Immunoregulatory Mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;137:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.06.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Q., Lv M., Li L., Huang W., Zhang Y., Hao Z. Temptation and Trap of Morel Industry in China. J. Fungal Res. 2021;19:232–237. doi: 10.13341/j.jfr.2021.1447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Q. Current Situation, Prospect and Suggestions of Morchella Industry in China. Edible Med. Mushrooms. 2018;26:148–151. [Google Scholar]

- 9.He X., Peng W., Miao R., Tang J., Chen Y., Liu L., Wang D., Gan B. White Mold on Cultivated Morels Caused by Paecilomyces penicillatus. FEMS Microbio. Lett. 2017;364:fnx037. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu T., Zhou J., Wang D., He X., Tang J., Chen Y., Wang J., Peng W. A New Stipe Rot Disease of the Cultivated Morchella sextelata. J. Fungal Res. 2021;40:2229–2243. doi: 10.13346/j.mycosystema.210055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lv B., Sun Y., Chen Y., Yu H., Mo Q. First Report of Lecanicillium aphanocladii Causing Rot of Morchella sextelata in China. Plant Dis. 2022;106:3202. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-12-21-2656-PDN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan Y.F., Cong Q.Q., Wang Q.W., Tang L.N., Li X.M., Yu Q.W., Cui X., An X.R., Yu C.X., Kong F.H., et al. First Report of Cladobotryum protrusum Causing Cobweb Disease on Cultivated Morchella importuna. Plant Dis. 2020;104:977. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-08-19-1611-PDN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fletcher J., Gaze R. Mushroom Pest and Disease Control: A Colour Handbook. 1st ed. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2007. pp. 1–160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adie B., Grogan H., Archer S., Mills P. Temporal and Spatial Dispersal of Cladobotryum Conidia in the Controlled Environment of a Mushroom Growing Room. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:7212–7217. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01369-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrasco J., Navarro M.J., Gea F.J. Cobweb, A Serious Pathology in Mushroom Crops: A Review. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2017;15:e10R01. doi: 10.5424/sjar/2017152-10143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu X.Y., Fu Y.P., Li Y. Biological characteristics of Cladobotryum dendroides, a causal pathogen of Lentinula edodes cobweb disease. J. Fungal Res. 2019;38:646–657. doi: 10.13346/j.mycosystema.180310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potocnik I., Rekanovic E., Milijašević-Marčić S., Biljana T., Stepanovic M. Morphological and Pathogenic Characteristics of the Fungus Cladobotryum dendroides, the Causal Agent of Cobweb Disease of the Cultivated Mushroom Agaricus Bisporus in Serbia. Pesticidi i Fitomedicina. 2008;23:175–181. doi: 10.2298/PIF0803175P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Q.-H., Wang W., Li C.-H., Wen Z.-Q. Biological characteristics of Hypomyces aurantius parasitic on Hypsizygus marmoreus. J. Fungal Res. 2015;34:350–356. doi: 10.13346/j.mycosystema.140248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H.-K., Seok S.-J., Kim G.-P., Moon B.-J., Terashita T. Occurrence of Disease Caused by Cladobotryum varium on Flammulina velutipes in Korea. Kor. J. Mycol. 1999;27:415–419. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin W.T., Li J., Zeng Z.Q., Wang S.X., Gao L., Rong C.B., Gao Q., Liu Y. First Report of Cobweb Disease in Oudemansiella raphanipes Caused by Cladobotryum varium in Beijing, China. Plant Dis. 2021;105:4171. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-02-21-0265-PDN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirschner R., Arnold G., Chen C.-J. Cladobotryum semicirculare sp. nov. (Hyphomycetes) from Commercially Grown Ganoderma tsugae in Taiwan and Other Basidiomycota in Cuba. Sydowia. 2007;59:114–124. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang G.Z., Ma C.J., Zhou S.S., Põldmaa K., Tamm H., Luo Y., Guo M.P., Ma X.L., Bian Y.B., Zhou Y. First Report of Cobweb Disease of Auricularia polytricha Caused by Cladobotryum cubitense in Xuzhou, China. Plant Dis. 2018;102:1452. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-11-17-1827-PDN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang G.Z., Guo M.P., Bian Y.B. First Report of Cladobotryum protrusum Causing Cobweb Disease on the Edible Mushroom Coprinus comatus. Plant Dis. 2015;99:287. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-14-0757-PDN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chakwiya A., Van der Linde E.J., Chidamba L., Korsten L. Diversity of Cladobotryum mycophilum Isolates Associated with Cobweb Disease of Agaricus bisporus in the South African Mushroom Industry. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2019;154:767–776. doi: 10.1007/s10658-019-01700-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuo B., Lu B., Liu X., Wang Y., Ma G., Wang X., Yang L., Liu X., Gao J. First Report of Cladobotryum mycophilum Causing Cobweb on Ganoderma lucidum Cultivated in Jilin Province, China. Plant Dis. 2016;100:1239. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-12-15-1431-PDN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim M.K., Lee Y.H., Cho K.M., Lee J.Y. First Report of Cobweb Disease Caused by Cladobotryum mycophilum on the Edible Mushroom Pleurotus eryngii in Korea. Plant Dis. 2012;96:1374. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-01-12-0015-PDN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gea F.J., Navarro M.J., Suz L.M. First Report of Cladobotryum mycophilum Causing Cobweb on Cultivated King Oyster Mushroom in Spain. Plant Dis. 2011;95:1030. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-11-0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sossah F.L., Liu Z., Yang C., Okorley B.A., Sun L., Fu Y., Li Y. Genome Sequencing of Cladobotryum protrusum Provides Insights into the Evolution and Pathogenic Mechanisms of the Cobweb Disease Pathogen on Cultivated Mushroom. Genes. 2019;10:124. doi: 10.3390/genes10020124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu R., Liu X., Peng B., Liu P., Li Z., Dai Y., Xiao S. Genomic Features of Cladobotryum dendroides, Which Causes Cobweb Disease in Edible Mushrooms, and Identification of Genes Related to Pathogenicity and Mycoparasitism. Pathogens. 2020;9:232. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9030232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seifert K.A., Gams W. The Genera of Hyphomycetes—2011 Update. Persoonia. 2011;27:119–129. doi: 10.3767/003158511X617435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White, Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. In: Innis M.A., Gelfand D.H., Sninsky J.J., White T.J., editors. PCR Protocols. A Guide to Methods and Applications. Academic Press; San Diego, CA, USA: 1990. pp. 315–322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carbone I., Kohn L.M. A Method for Designing Primer Sets for Speciation Studies in Filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia. 1999;91:553–556. doi: 10.1080/00275514.1999.12061051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Primers for Elongation Factor 1-α-AFTOL-Douding Web. [(accessed on 5 November 2022)]. Available online: https://www.docin.com/p-1613748809.html.

- 34.Liu Y.J., Whelen S., Hall B.D. Phylogenetic Relationships among Ascomycetes: Evidence from an RNA Polymerse II Subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999;16:1799–1808. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall T. Bioedit: A User-Friendly Biological Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Program for Windows 95/98/ NT. Nucl. Acids. Symp. Ser. 1999;41:95–98. doi: 10.14601/Phytopathol_Mediterr-14998u1.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stamatakis A. RAxML Version 8: A Tool for Phylogenetic Analysis and Post-Analysis of Large Phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ronquist F., Teslenko M., van der Mark P., Ayres D.L., Darling A., Höhna S., Larget B., Liu L., Suchard M.A., Huelsenbeck J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and Model Choice across a Large Model Space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim H.J., Lee E.H., Yoon Y., Chua B., Son A. Portable Lysis Apparatus for Rapid Single-Step DNA Extraction of Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Soc. Appl. Bact. 2016;120:379–387. doi: 10.1111/jam.13011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashburner M., Ball C.A., Blake J.A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J.M., Davis A.P., Dolinski K., Dwight S.S., Eppig J.T., et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the Unification of Biology. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanehisa M., Goto S., Kawashima S., Okuno Y., Hattori M. The KEGG Resource for Deciphering the Genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D277–D280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kanehisa M., Goto S., Hattori M., Aoki-Kinoshita K.F., Itoh M., Kawashima S., Katayama T., Araki M., Hirakawa M. From Genomics to Chemical Genomics: New Developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D354–D357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galperin M.Y., Makarova K.S., Wolf Y.I., Koonin E.V. Expanded Microbial Genome Coverage and Improved Protein Family Annotation in the COG Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D261–D269. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W., Jaroszewski L., Godzik A. Tolerating Some Redundancy Significantly Speeds up Clustering of Large Protein Databases. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:77–82. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saier M.H., Reddy V.S., Tsu B.V., Ahmed M.S., Li C., Moreno-Hagelsieb G. The Transporter Classification Database (TCDB): Recent Advances. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D372–D379. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bairoch A., Apweiler R. The SWISS-PROT Protein Sequence Database and Its Supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:45–48. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petersen T.N., Brunak S., von Heijne G., Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: Discriminating Signal Peptides from Transmembrane Regions. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Medema M.H., Blin K., Cimermancic P., de Jager V., Zakrzewski P., Fischbach M.A., Weber T., Takano E., Breitling R. AntiSMASH: Rapid Identification, Annotation and Analysis of Secondary Metabolite Biosynthesis Gene Clusters in Bacterial and Fungal Genome Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W339–W346. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Urban M., Pant R., Raghunath A., Irvine A.G., Pedro H., Hammond-Kosack K.E. The Pathogen-Host Interactions Database (PHI-Base): Additions and Future Developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D645–D655. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang H., Yohe T., Huang L., Entwistle S., Wu P., Yang Z., Busk P.K., Xu Y., Yin Y. dbCAN2: A meta server for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W95–W101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li D., Sossah F.L., Sun L., Fu Y., Li Y. Genome Analysis of Hypomyces perniciosus, the Causal Agent of Wet Bubble Disease of Button Mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) Genes. 2019;10:417. doi: 10.3390/genes10060417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Druzhinina I.S., Chenthamara K., Zhang J., Atanasova L., Yang D., Miao Y., Rahimi M.J., Grujic M., Cai F., Pourmehdi S., et al. Massive Lateral Transfer of Genes Encoding Plant Cell Wall-Degrading Enzymes to the Mycoparasitic Fungus Trichoderma from Its Plant-Associated Hosts. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Galagan J.E., Calvo S.E., Borkovich K.A., Selker E.U., Read N.D., Jaffe D., FitzHugh W., Ma L.-J., Smirnov S., Purcell S., et al. The Genome Sequence of the Filamentous Fungus Neurospora crassa. Nature. 2003;422:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nature01554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dean R.A., Talbot N.J., Ebbole D.J., Farman M.L., Mitchell T.K., Orbach M.J., Thon M., Kulkarni R., Xu J.-R., Pan H., et al. The Genome Sequence of the Rice Blast Fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Nature. 2005;434:980–986. doi: 10.1038/nature03449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ray S., Singh P.K., Gupta D.K., Mahato A.K., Sarkar C., Rathour R., Singh N.K., Sharma T.R. Analysis of Magnaporthe oryzae Genome Reveals a Fungal Effector, Which Is Able to Induce Resistance Response in Transgenic Rice Line Containing Resistance Gene, Pi54. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1140. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Warmington R.J., Kay W., Jeffries A., O’Neill P., Farbos A., Moore K., Bebber D.P., Studholme D.J. High-Quality Draft Genome Sequence of the Causal Agent of the Current Panama Disease Epidemic. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2019;8:e00904–e00919. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00904-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bushley K.E., Raja R., Jaiswal P., Cumbie J.S., Nonogaki M., Boyd A.E., Owensby C.A., Knaus B.J., Elser J., Miller D., et al. The Genome of Tolypocladium inflatum: Evolution, Organization, and Expression of the Cyclosporin Biosynthetic Gene Cluster. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kubicek C.P., Herrera-Estrella A., Seidl-Seiboth V., Martinez D.A., Druzhinina I.S., Thon M., Zeilinger S., Casas-Flores S., Horwitz B.A., Mukherjee P.K., et al. Comparative Genome Sequence Analysis Underscores Mycoparasitism as the Ancestral Life Style of Trichoderma. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R40. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martinez D., Berka R.M., Henrissat B., Saloheimo M., Arvas M., Baker S.E., Chapman J., Chertkov O., Coutinho P.M., Cullen D., et al. Genome Sequencing and Analysis of the Biomass-Degrading Fungus Trichoderma reesei (Syn. Hypocrea jecorina) Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:553–560. doi: 10.1038/nbt1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karlsson M., Durling M.B., Choi J., Kosawang C., Lackner G., Tzelepis G.D., Nygren K., Dubey M.K., Kamou N., Levasseur A., et al. Insights on the Evolution of Mycoparasitism from the Genome of Clonostachys rosea. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015;7:465–480. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li L., Stoeckert C.J., Roos D.S. OrthoMCL: Identification of Ortholog Groups for Eukaryotic Genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Back C.-G., Lee C.-Y., Seo G.-S., Jung H.-Y. Characterization of Species of Cladobotryum Which Cause Cobweb Disease in Edible Mushrooms Grown in Korea. Mycobiology. 2012;40:189–194. doi: 10.5941/MYCO.2012.40.3.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gea F.J., Navarro M.J., Suz L.M. First Report of Cobweb Disease Caused by Cladobotryum dendroides on Shiitake Mushroom (Lentinula edodes) in Spain. Plant Dis. 2018;5:1030. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-17-1481-PDN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gea F.J., Carrasco J., Navarro M. Characterization and Pathogenicity of Cladobotryum mycophilum in Spanish Pleurotus eryngii Mushroom Crops and its Sensitivity to Fungicides. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2016;147:189–194. doi: 10.1007/s10658-016-0986-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu X.Y., Li Y. First Report of Cobweb Disease Caused by Cladobotryum mycophilum on Cultivated Shiitake Mushroom (Lentinula edodes) in China. Plant Dis. 2020;104:573. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-19-1434-PDN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tian F.H., Li C.T., Li Y. First Report of Cladobotryum varium Causing Cobweb Disease of Pleurotus eryngii var. tuoliensis in China. Plant Dis. 2018;102:826. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-05-17-0741-PDN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gea F.J., Navarro M.J., Suz L.M. Cobweb Disease on Oyster Culinary-Medicinal Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Caused by the Mycoparasite Cladobotryum mycophilum. J. Plant Pathol. 2019;101:349–354. doi: 10.1007/s42161-018-0174-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carrasco J., Navarro M., Santos M., Diánez F., Gea F.J. Incidence, Identification and Pathogenicity of Cladobotryum mycophilum, Causal Agent of Cobweb Disease on Agaricus bisporus Mushroom Crops in Spain. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2016;168:214–224. doi: 10.1111/aab.12257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mohanta T.K., Bae H. The diversity of fungal genome. Biol. Proced Online. 2015;17:8. doi: 10.1186/s12575-015-0020-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bashyal B.M., Rawat K., Sharma S., Kulshreshtha D., Gopala Krishnan S., Singh A.K., Dubey H., Solanke A.U., Sharma T.R., Aggarwal R. Whole Genome Sequencing of Fusarium fujikuroi Provides Insight into the Role of Secretory Proteins and Cell Wall Degrading Enzymes in Causing Bakanae Disease of Rice. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:2013. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.02013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang Q.-S., Xie X.-L., Liang G., Gong F., Wang Y., Wei X.-Q., Wang Q., Ji Z.-L., Chen Q.-X. The GH18 Family of Chitinases: Their Domain Architectures, Functions and Evolutions. Glycobiology. 2012;22:23–34. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Seidl V. Chitinases of Filamentous Fungi: A Large Group of Diverse Proteins with Multiple Physiological Functions. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2008;22:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.fbr.2008.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Frandsen R.J.N., Nielsen N.J., Maolanon N., Sørensen J.C., Olsson S., Nielsen J., Giese H. The Biosynthetic Pathway for Aurofusarin in Fusarium graminearum Reveals a Close Link between the Naphthoquinones and Naphthopyrones. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:1069–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.De Wit P.J.G.M., Mehrabi R., Van den Burg H.A., Stergiopoulos I. Fungal Effector Proteins: Past, Present and Future. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2009;10:735–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sperschneider J., Gardiner D.M., Dodds P.N., Tini F., Covarelli L., Singh K.B., Manners J.M., Taylor J.M. EffectorP: Predicting Fungal Effector Proteins from Secretomes Using Machine Learning. New Phytol. 2016;210:743–761. doi: 10.1111/nph.13794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This paper’s genome sequence data and assembly are linked with NCBI BioProject: PRJNA917475 and BioSample: SUB12509998.