Abstract

Background

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare and aggressive skin cancer, associated with a worse prognosis. The Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs) avelumab and pembrolizumab have been recently approved as first-line treatment in metastatic MCC (mMCC). The clinical observation of improved outcomes in obese patients following treatment with ICIs, known as the “obesity paradox”, has been studied across many types of tumors. Probably due to the rarity of this tumor, data on mMMC patients are lacking.

Patients and methods

This is an observational, hospital-based, study to investigate the role of Body Mass Index (BMI) as predictive biomarker of ICI response in mMCC patients treated with avelumab as first-line treatment. The study population included the patients treated from February 2019 to October 2022 in an Italian referral center for rare tumors. Clinico-pathological characteristics, BMI, laboratory parameters (NLR and platelet count), and response to avelumab were analyzed from a MCC System database prospectively collected.

Results

Thirty-two (32) patients were included. Notably, the presence of pre-treatment BMI ≥ 30 was significantly associated with longer PFS [BMI < 30 Group: median PFS, 4 months (95% CI: 2.5-5.4); BMI ≥ 30 Group: median PFS, not reached; p<0.001)[. Additionally, the median PFS was significantly higher in patients with higher PLT (median PFS: 10 months in the “low PLT” Group (95% CI: 4.9, 16.1) vs 33 months (95% CI: 24.3, 43.2) in the “high PLT” Group (p=0.006). The multivariable Cox regression model confirmed these results.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that investigates the predictive role of BMI in MCC patients. Our data were consistent with the clinical observation of improved outcomes in obese patients across other tumor types. Thus, advanced age, a weakened immune system, and the obesity-associated “inflammaging”, are key factors that could impact the cancer immune responses of mMCC patients.

Keywords: Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), avelumab, body mass index - BMI, predictive factors, immunotherapy, skin cancer non melanoma

1. Introduction

Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC) is a rare primary cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinoma usually involving the sun-exposed skin of elderly individuals, but sometimes also the trunk and limbs (1). Immunosuppression, chronic ultraviolet (UV) exposure, and old age are known predisposing factors (2), and MMC incidence is rising in Western countries (3). Clinical presentation is a rapidly growing, painless, erythematous/violaceous nodule or plaque (4). MCC is an aggressive tumor, as synchronous nodal and/or systemic metastases are present in about one-third of cases (2). Merkel Cell Polyomavirus (MCPyV) seems to be the pathogenic factor for about 80% of MMCs in the northern hemisphere, as viral DNA was shown to be integrated within the tumor genome (1, 5). The genetic damage induced by UV radiation accounts for the pathogenesis of the MCPyV-negative MCCS, showing a high tumor mutational burden (TMB) and a UV mutational signature (6).

The Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs), anti-PD-L1 avelumab and anti-PD-1 pembrolizumab, have been recently approved as first-line treatment in metastatic MCC, although only a minority of patients exhibit long-term response (7, 8). Response to ICI therapy did not correlate either with MCPyV or with UV mutational signature status (9). An association with PD-1/PD-L1 tumor tissue expression was found (9, 10), but current assays remain imperfect to predict which patient will benefit from immunotherapy (11). Thus, further predictors of response are needed.

Recently, the clinical, contrasting, observation of improved outcomes in obese patients following treatment with immune checkpoint blockade, known as the “obesity paradox”, has been studied across many types of tumors (12). Cancer patients with high body mass index (BMI) seem to respond better to ICI therapy when compared to those with normal BMI (13–17). Probably due to the rarity of this tumor, data on the relationship between BMI and response to ICI treatment among MMC patients are lacking. Although the mechanistic link between metabolic state and immunotherapy benefit was not clearly elucidated, clinical data linking excess adiposity to ICI response in MCC patients could give more insights into the complex immune-metabolic interactions, serving as both predictive and stratification factors in future clinical trials.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and patient selection

This was an observational, hospital-based, study to investigate the role of BMI as a predictive biomarker of immunotherapy response in metastatic MCC (mMCC) patients treated with the ICI avelumab.

The study population included adult patients with a pathologically confirmed diagnosis of MCC and advanced disease, treated with avelumab in the first-line setting, according to medical choice and current therapeutic options. The patients were treated from February 2019 to October 2022 in an Italian referral center for rare tumors: the “Sicilian Regional Center for the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Rare and Heredo-Familial Tumors” of the University Hospital Policlinico “Paolo Giaccone” of Palermo. Patients data were analyzed from a MCC System database prospectively collected. The pathological information collected on primary MCC included the histology, the Ki-67 (%) value and chromogranin A expression from pathology reports for clinical use. The clinical data on disease stages, comorbidities and hepatopathy, second tumor history, the primary site of the tumors, number of metastatic sites, dose, and duration of avelumab treatment, were abstracted from the clinical records. Pre-treatment BMI, Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) and platelet count (PLT) were recorded. The NLR was extracted from the routinely performed blood cell count, as the absolute count of neutrophils divided by the absolute count of lymphocytes from peripheral blood samples collected at baseline. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Normal weight (BMI=18.5-24.9), overweight (BMI=25-29.9), and obesity (BMI ≥ 30) were classified based on the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations (nota).

The tumor response [progressive disease (PD), stable disease (SD), partial response (PR), complete response (CR)] according to Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST version 1.1.), objective response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS) to avelumab treatment, and overall survival (OS) were assessed. The association between clinic-pathological variables, BMI, and clinical outcomes was evaluated. All clinical characteristics were anonymously recorded and coded.

The protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the University-affiliated Hospital A.O.U.P. “Paolo Giaccone” (approval number 1122), and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

2.2. Statistical considerations

Descriptive analyses were used to assess patients’ characteristics. The differences between subgroups were evaluated by Fisher’s exact test. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to define the relationship between age and BMI.

The primary outcome of the study was progression-free survival (PFS). PFS was calculated from the beginning of the immunotherapy treatment to death by any cause or disease progression or last follow-up (censored patients). Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the start of immunotherapy treatment to death by any cause or last follow-up (censored patients). The analysis of PFS and OS between groups was compared using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves analysis was used to determine the optimal cut-off for PLT count and NLR.

To identify independent prognostic factors for PFS and OS, univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models were built. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 29.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Study population

From February 2019 to October 2022, thirty-two (32) patients were included in the study. The median age was 75 (range 43-89). Seventeen patients were men (53%) and fifteen were women (47%). All the patients had an ECOG Performance status of 0 or 1. Twenty-one patients (66%) had two or more comorbidities (cardiovascular, endocrinological and/or another concomitant disease). In particular, twelve (12) patients (38%) were obese (BMI ≥ 30), while twenty (20) patients had a BMI <30 (62%). Additionally, seven (7) patients had a previous hepatopathy and eight (8) patients had a second hematological or solid tumor. The most common tumor primary site was the lower limb (21 patients, 66%), followed by unknown origin (5 patients, 16%). Fifteen (15) patients had only lymph node involvement (47%), and 17 patients (53%) showed other metastatic sites (visceral or soft tissues, alone or along with lymph node metastasis). Pathological and clinical patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Patients’ and disease characteristics.

| Characteristic | All patients No. (%) |

BMI<30 No. (%) |

BMI≥ 30 No. (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients (%) | 32 (100) | 20 (62.5) | 12 (37.5) | – |

|

Gender

Male Female |

17 (53.1) 15 (46.1) |

10 (50.0) 10 (50.0) |

7 (58.3) 5 (41.7) |

0.2 |

|

Age (years),

median (range) <75 y ≥75 y |

75 (43–89) 16 (50.0) 16 (50.0) |

7 (35.0) 13 (65.0) |

9 (75.0) 3 (25.0) |

0.02 |

|

ECOG

0 1 |

23 (71.9) 9 (28.1) |

15 (75.0) 5 (25.0) |

8 (66.7) 4 (33.3) |

0.2 |

|

No of Comorbidities

<2 ≥2 |

11 (34.4) 21 (65.6) |

6 (30.0) 14 (70.0) |

5 (41.7) 7 (58.3) |

0.4 |

|

Hepatopathy

No Yes Unknown |

22 (68.8) 7 (21.9) 3 (9.3) |

13 (65.0) 5 (25.0) 2 (10.0) |

9 (75.0) 2 (16.7) 1 (8.3) |

0.3 |

|

Second Tumor

No Yes |

24 (75.0) 8 (25.0) |

14 (70.0) 6 (30.0) |

10 (83.3) 2 (16.7) |

0.7 |

|

Primary site

Head and neck Trunk Upper limb Lower limb Unknown |

2 (6.3) 2 (6.3) 2 (6.3) 21 (65.6) 5 (15.6) |

1 (5.0) 0 (0.0) 2 (10.0) 14 (70.0) 3 (15.0) |

1 (8.3) 2 (16.7) 0 (0.0) 7 (58.3) 2 (16.7) |

0.03 |

|

KI67%

<90 ≥90 Unknown |

11 (34.4) 17 (53.1) 4 (12.5) |

6 (30.0) 11 (55.0) 3 (15.0) |

5 (41.7) 6 (50.0) 1 (8.3) |

0.4 |

|

Chromogranin-A

Negative Positive Not specified |

1 (3.1) 23 (71.9) 8 (25.0) |

0 (0.0) 14 (70.0) 6 (30.0.0) |

1 (8.3) 9 (75.0) 2 (16.7) |

0.7 |

|

Metastatic at diagnosis

No Yes |

13 (40.6) 19 (59.4) |

10 (50.0) 10 (50.0) |

3 (25.0) 9 (75.0) |

0.1 |

|

N. of metastatic sites

<2 ≥2 |

12 (37.5) 20 (62.5) |

8 (40.0) 12 (60.0) |

4 (33.3) 8 (66.7) |

0.7 |

|

Common site of metastasis

Lymph nodes Others |

15 (46.9) 17 (53.1) |

10 (50.0) 10 (50.0) |

5 (41.7) 7 (58.3) |

0.6 |

|

NLR

<2, ≥2 Unknown |

7 (21.9) 17 (53.1) 8 (25.0) |

5 (25.0) 10 (50.0) 5 (25.0) |

2 (16.7) 7 (58.3) 3 (25.0) |

0.5 |

|

PLT

<207 ≥207 Unknown |

11 (34.4) 15 (46.8) 6 (18.8) |

8 (40.0) 8 (40.0) 4 (20.0) |

3 (25.0) 7 (58.3) 2 (16.7) |

0.2 |

BMI, Body Mass Index; NLR, Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR); PLT, platelet count.

3.2. Outcome analysis

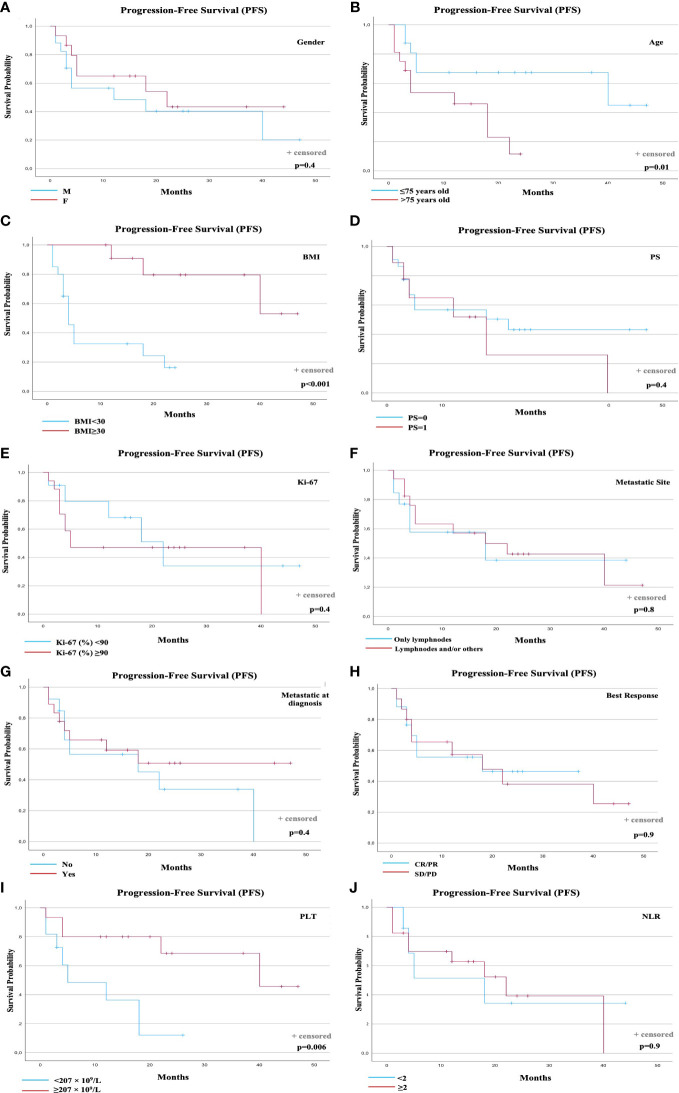

Overall, the median PFS was 18 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 6.6-31.1). At the time of data analyses, 17 events (progression or death) occurred (53.1%). Notably, the presence of pre-treatment BMI ≥ 30 was significantly associated with longer PFS ( Figure 1C ). A total of 14 events were observed in the group of 20 patients with BMI <30 (70.0%), and 3 events in the group of 12 patients with BMI ≥ 30 (25.0%). Median PFS was 4 months for the BMI < 30 Group (95% CI: 2.5-5.4), and not reached for the group of patients with BMI ≥ 30 (p<0.001). The presence of age <75 years old was significantly associated with longer PFS (p=0.01)( Figure 1B ). A statistically significant and clinical meaningful correlation between BMI and age was shown using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (p=0.008).

Figure 1.

PFS according to prognostic factors. PFS according to: (A) Gender; (B) Age; (C) Baseline BMI; (D) Performance status (PS); (E) Ki-67 (%); (F) Metastatic Sites; (G) Metastatic disease at diagnosis; (H) Best Response to avelumab; (I) Baseline PLT count; (J) Baseline NLR. BMI, Body Mass Index; NLR, Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio; PLT, Platelets; PFS, Progression-free Survival.

Regarding the outcome data according to PLT count, the pre-treatment value was available for 26 patients. Eight (8) events were observed in the group of 11 patients with PLT count < 207 × 109/L (72.7%), and 5 events in the group of 15 patients with PLT count ≥ 207 × 109/L (33.3%). Median PFS was 10 months for the low PLT Group (95% CI: 4.9, 16.1), and 33 months (95% CI: 24.3, 43.2) for the high PLT Group (p=0.006) ( Figure 1I ). No other prognostic factors (gender, Performance Status, Ki-67 (%), metastatic sites, metastatic stage at diagnosis, best response to avelumab, and NLR at baseline) were statistically associated with PFS ( Figures 1A, D–F, G, H, J ).

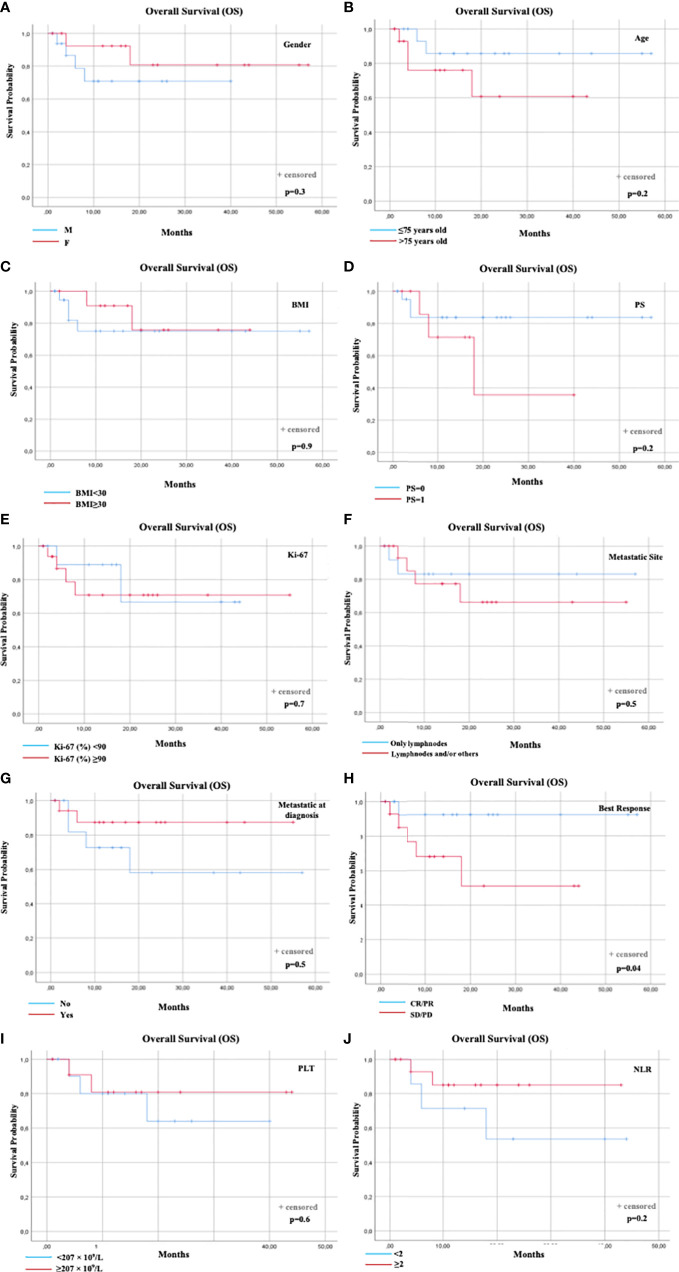

Overall median OS was not reached. Six (6) total events (deaths) were observed (18.7%). The only prognostic factor statistically associated with OS was the best response to avelumab (p=0.04). The distribution of events according to best response was: 1 event1 in 17 patients with best response CR or PR (5.9%) and 5 events in 15 patients with best response SD or PD (33.3%). Median OS was not reached for the patients with CR/PR or SD/PD ( Figure 2H ). No other prognostic factors were statistically associated with OS ( Figures 1A–G, I, J ).

Figure 2.

OS according to prognostic factors. OS according to: (A) Gender; (B) Age; (C) Baseline BMI; (D) Performance status (PS); (E) Ki-67 (%); (F) Metastatic Sites; (G) Metastatic disease at diagnosis; (H) Best Response to avelumab; (I) Baseline PLT count; (J) Baseline NLR. BMI, Body Mass Index; NLR, Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio; PLT, Platelets; Overall Survival.

3.3. Objective response rate (ORR) and timing of response

Seventeen (17) out of 32 mMCC patients (53.1%) achieved objective tumor responses, including 3 patients who obtained CRs (9.4%) ( Table 2 ). The majority of patients with BMI < 30 achieved a PR (50%) as the best response. In the group with BMI ≥ 30, the SD was the most frequent response achieved (41.7%), followed by PR (33.3%). The median time to objective response was of 4 months (range, 2–7 months) in the overall population. Tumor responses were more rapid in the group of patients BMI < 30 [3.5 months (range, 2-7 months)[ than in those with BMI ≥ 30 [6 months (range, 3-7 months)].

Table 2.

Objective responses and timing of responses to avelumab.

| All patients | BMI<30 | BMI≥ 30 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients (%) | 32 (100) | 20 (62.5) | 12 (37.5) |

|

Time to

Response, Median (range), months |

4 (2-7) | 3.5 (2-7) | 6 (3-7) |

|

Overall Response

(CR + PR), No. (%) |

17 (53.1) | 12 (60.0) | 5 (41.7) |

|

Best Response, No. (%)

CR PR SD PD |

3 (9.4) 14 (43.8) 8 (25.0) 7 (21.8) |

2 (10.0) 10 (50.0) 3 (15.0) 5 (25.0) |

1 (8.3) 4 (33.3) 5 (41.7) 2 (16.7) |

CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

3.4. Univariable and multivariable analysis

Table 3 summarizes the results of the univariable and multivariable prognostic factor analysis for PFS and OS. Variables included in the univariate analysis were: (1) gender (male or female); (2) age at avelumab start (≤ 75 or > 75 years); (3) pre-treatment BMI (< 30 or ≥ 30); (4) performance status (1 or 0); (5) Ki-67 (%) (<90 or ≥90); (6) metastatic sites (only lymph nodes or lymph nodes and/or other sites); (7) metastatic at diagnosis (no or yes); (8) best response to avelumab (CR/PR or SD/PD); (9) pre-treatment PLT count (< 207 or ≥ 207 × 109/L); (10) pre-treatment NLR (<2 or ≥ 2).

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable analysis of prognostic factors for PFS and OS in MCC patients treated with avelumab.

| PFS | Univariable Cox Regression | Multivariable Cox Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | p-value | HR (95%CI) | p-value | |

| Gender (F vs M) |

0.67 (0.25-1.78) | NS | ||

| Age (>75 vs ≤75 years old) |

3.28 (1.13-9.55) | 0.02 | 1.58 (0.39-6.39) | 0.51 |

| BMI (≥30 vs <30) |

0.12 (0.03-0.53) | 0.005 | 0.18 (0.03-0.93) | 0.04 |

| Performance status (PS) (1 vs 0) |

1.47 (0.54-4.02) | NS | ||

| Ki-67 (%) (≥90 vs <90) |

1.44 (0.48-4.28) | NS | ||

| Metastatic Sites (Lymphnodes and/or others vs only lymphnodes) |

0.90 (0.32-2.51) | NS | ||

| Metastatic at diagnosis (yes vs no) |

0.69 (0.26-1.83) | NS | ||

| Best Response (SD/PD vs CR/PR) |

1.05 (0.39-2.81) | NS | ||

| PLT (≥207 vs < 207 × 109/L) |

0.22 (0.06-0.74) | 0.01 | 0.23 (0.06-0.85) | 0.02 |

| NLR (≥2 vs <2) |

1.01 (0.31-0.71) | NS | ||

| OS | Univariable Cox Regression | Multivariable Cox Regression | ||

| HR (95%CI) | p-value | HR (95%CI) | p-value. | |

| Gender (F vs M) |

0.44 (0.08-2.47) | NS | ||

| Age (>75 vs ≤75 years old) |

2.81 (0.51-15.39) | NS | ||

| BMI (≥30 vs <30) |

0.61 (0.11-3.37) | NS | ||

| Performance status (PS) (1 vs 0) |

2.53 (0.50-12.76) | NS | ||

| Ki-67 (%) (≥90 vs <90) |

1.36 (0.25-7.46) | NS | ||

| Metastatic Sites (Lymphnodes and/or others vs only lymphnodes) |

1.59 (0.29-8.68) | NS | ||

| Metastatic at diagnosis (yes vs no) |

0.34 (0.06-1.87) | NS | ||

| Best Response (SD/PD vs CR/PR) |

6.41 (0.74-55.34) | 0.04 | ||

| PLT (≥207 vs < 207 × 109/L) |

0.65 (0.11-3.92) | NS | ||

| NLR (≥2 vs <2) |

0.35 (0.06-2.12) | NS | ||

Gender, age, BMI, Performance Status, Ki-67 (%), metastatic sites, metastatic stage at diagnosis, best response to avelumab, PLT and NLR at baseline, were evaluated in the Cox regression model.

NS, Not Significant.

Age, BMI, and PLT were found to be statistically significantly associated with PFS in univariable analyses. In the final multivariable Cox regression model, BMI (p=0.04, HR: 0.18), and PLT (p=0.02, HR: 0.23) were significant.

Regarding OS, only best respone to avelumab was statistically significantly associated in univariable analyses. In the final multivariable model, no prognostic factor considered remains statistically significant.

Therefore, these results showed that, in metastatic MCC patients treated with the PD-L1-inhibitor avelumab, BMI ≥ 30 and PLT ≥ 207 × 109/L were significant independent prognostic factors for longer PFS.

PFS and OS curves were plotted according to each prognostic factor ( Figures 1 , 2 ).

4. Discussion

MCC is an uncommon and highly aggressive neuroendocrine neoplasm difficult to treat (4). Until some years ago the treatment of choice for advanced MCC has been chemotherapy, as well as in poorly differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasms, showing a median PFS of 3–4 months, median OS of less than 10 months, and significant toxicity (4, 18). The association between increased MCC incidence in the elderly and/or immunocompromised subjects and pathological immune dysfunction always suggested a significant role of the immune system in MCC development (19, 20).

Recently, immunotherapy has become the mainstay of treatment of metastatic disease, with durable responses in some cases (21). To date, three immune checkpoint inhibitors (avelumab, pembrolizumab and nivolumab) (7, 22, 23), and the combined nivolumab and ipilimumab (24) resulted to be active in the treatment of advanced MCC. Avelumab was the first approved anti-PD-L1 treatment for patients with metastatic MCC, based on efficacy and safety data observed in the JAVELIN Merkel 200 trial (22). However, as well as for other cancers, only around half of the patients with mMCC respond to the immune‐checkpoint blockade, and a substantial number of patients developed acquired resistance. Consequently, there is a clinical need for predictive factors of immunotherapy response, and understanding the underlying tumor immune escape mechanisms following the ICI treatment is urgently warranted (25).

Recent pan-cancer outcome analyses on patients with or without obesity treated with ICIs showed that presenting with a BMI of 30 or higher was associated with prolonged survival than having BMI less than 30. This study was performed across many cancer types, such as melanoma, NSCLC and SCLC, renal cell carcinoma, bladder cancer, breast cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, sarcoma, and others (12), and the final results were in agreement with some previous published studies that hypothesized the “paradoxical effects” of obesity on cancer immunotherapy across multiple tumor types.

To our knowledge and based on the best data available today, this is the first study that investigates the role of BMI in patients affected by Merkel Cell Carcinoma treated with checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. In our survival analyses, obese mMCC patients showed improved PFS following avelumab treatment than patients with overweight or normal weight. Multivariable Cox regression analyses confirmed these results.

This is consistent with the notion that obesity might lead to an immune aging effect, which could be particularly highlighted in elderly MCC patients. These patients seem to be often immunocompromised, not only for the physiological age-related immune senescence, but also for the frequent history of solid organ and/or hematological stem cell transplantation, and hematological malignancies, especially B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (20). Notably, obesity is often accompanied by a chronic low-grade systemic inflammation (26–28), stimulated by the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, which alters the microenvironment of expanded adipose tissue. Chronic inflammation can induce immunosuppression as a result of a T cells exhaustion by persistent antigenic stimulation, ultimately inducing dysfunction of the immune system in obese patients (28).

Thus, advanced age, a weakened immune system, and the potential obesity-associated “inflammaging” (28), are key factors that could impact the cancer immune responses in the context of immunotherapy treatment of mMCC patients.

Despite our results showed that most of obese mMCC patients were younger [9 out 12 patients <75 years old (75%) had BMI ≥ 30] than patients with normal weight or overweight, MCC is a tumor of elderly individuals, and the median age of these patients, stratified as younger, were 63 years. In agreement with the known causes of progressive disease or death during avelumab treatment, this result linking higher BMI and younger age was not influenced by clinical factors beyond the metastatic cancer diagnosis.

Although our study focuses on obesity and outcomes of ICI, we further observed a predictive value of platelet counts at baseline before immunotherapy. Interestingly, according to a growing body of evidence, a direct cross-talk between platelets and host immunity seemed to exist (29). Pre-clinical studies have suggested the contribution of platelets to systemic and local responses against cancers (30). Platelets lack a nucleus and DNA available for the transcription of new RNA molecules. However, they can sequester molecules, including RNA and protein transcripts, altering their spliced RNA profiles (31, 32). Specific splice events may be induced in response to signals released by tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment (33). Thus, the resulting “tumor-educated platelets (TEPs) represent dynamic biomolecules with a rich and highly variable repertoire of mRNA, transported from the tumor microenvironment forward multiple anatomic sites (30, 34).

Furthermore, tumor-associated thrombocytosis has been linked to poor clinical outcomes in several cancers, including pancreatic cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma or glioblastoma (15, 35–38), and it recently has been significantly associated with a poorer prognosis in lung cancer and melanoma patients receiving immunotherapy (39–41). Rachidi et al. (42) showed that platelets can suppress T-cell responses against tumors through the production and activation of immunosuppressive factors, including TGFβ, demonstrating how platelet-related TGFβ activation contributes dominantly to the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.

In our study population, we observed that mMCC patients with higher platelet counts assessed at baseline had improved PFS following first-line avelumab treatment. The multivariable model confirmed the independent prognostic value of this finding. The biological reason remains speculative. A possible explanation is that the higher immunosuppression associated with elevated basal platelets may lead to a greater effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors in reinvigorating the T-cell immune response against the tumor following avelumab treatment.

Limitations of our study include the small sample size due to the rarity of this cancer and the retrospective data analysis. On the other hand, all the patients studied were consecutively collected from our single referral Center, thus patients’ data, although retrospective, should be homogenous, limiting possible biases. In addition, BMI is not a perfect assessment of obesity because it cannot distinguish muscle from body fat (43). Accordingly, more specific body fat assessment methods should be used in future prospective studies on larger cohorts.

5. Conclusion

MCC has long been considered to be immunogenic cancer because it occurs more frequently and has a worse prognosis in immunosuppressed individuals. Despite the therapeutic impact of reinvigorating the antitumor immune response by immunotherapy, the clinical benefit of ICIs in mMCC is still limited to selected patients. From previous studies across many cancer types, we have learned that in metastatic patients treated with ICIs, obesity is often associated with better clinical outcomes. Our findings validate this concept also in mMCC patients following avelumab treatment, demonstrating a positive effect on PFS of a BMI > 30. The association between basal platelet count and PFS seemed to suggest that a cross-talk platelets-host immunity exists. It remains to be elucidated whether other clinical, immunological or biological factors not yet investigated, may have a further relevant impact on tumor response and clinical outcomes.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethical committee of the University-affiliated Hospital A.O.U.P. “Paolo Giaccone” (Palermo 1)(approval number 1122). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: LI, VB, AR, and GB. Data collection: AD, LA, LM, IL, RS, AB, TB, FL, MP, DG, IF, FT, AC, and AF. Analysis and interpretation of results: LI, AD, CB, EP, AP, VG, AGi, AGa and GB. Draft manuscript preparation: LI, AD, LM, AP, CB, EP, and GB. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Walsh NM, Cerroni L. Merkel cell carcinoma: A review. J Cutan Pathol (2021) 48(3):411–21. doi: 10.1111/cup.13910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harms KL, Healy MA, Nghiem P, Sober AJ, Johnson TM, Bichakjian CK, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors from 9387 merkel cell carcinoma cases forms the basis for the new 8th edition AJCC staging system. Ann Surg Oncol (2016) 23(11):3564–71. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5266-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Paulson KG, Park SY, Vandeven NA, Lachance K, Thomas H, Chapuis AG, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. J Am Acad Dermatol (2018) 78(3):457–63.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Becker JC, Stang A, DeCaprio JA, Cerroni L, Lebbé C, Veness M, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Prim (2017) 3:17077. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human merkel cell carcinoma. Science (2008) 319(5866):1096–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mazziotta C, Cervellera CF, Lanzillotti C, Touzé A, Gaboriaud P, Tognon M, et al. MicroRNA dysregulations in merkel cell carcinoma: molecular mechanisms and clinical application. J Med Virol (2022) 95(1):e28375. doi: 10.1002/jmv.28375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nghiem PT, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, Kudchadkar RR, Miller NJ, Annamalai L, et al. PD-1 blockade with pembrolizumab in advanced merkel-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med (2016) 374(26):2542–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. D'Angelo SP, Russell J, Lebbé C, Chmielowski B, Gambichler T, Grob JJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of first-line avelumab treatment in patients with stage IV metastatic merkel cell carcinoma: A preplanned interim analysis of a clinical trial. JAMA Oncol (2018) 4(9):e180077. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Knepper TC, Montesion M, Russell JS, Sokol ES, Frampton GM, Miller VA, et al. The genomic landscape of merkel cell carcinoma and clinicogenomic biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Clin Cancer Res (2019) 25(19):5961–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-4159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giraldo NA, Nguyen P, Engle EL, Kaunitz GJ, Cottrell TR, Berry S, et al. Multidimensional, quantitative assessment of PD-1/PD-L1 expression in patients with merkel cell carcinoma and association with response to pembrolizumab. J Immunother Canc (2018) 6(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0404-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhao X, Bao Y, Meng B, Xu Z, Li S, Wang X, et al. From rough to precise: PD-L1 evaluation for predicting the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 blockades. Front Immunol (2022) 13:920021. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.920021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yoo SK, Chowell D, Valero C, Morris LGT, Chan TA. Outcomes among patients with or without obesity and with cancer following treatment with immune checkpoint blockade. JAMA Netw Open (2022) 5(2):e220448. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cortellini A, Bersanelli M, Buti S, Cannita K, Santini D, Perrone F, et al. A multicenter study of body mass index in cancer patients treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors: When overweight becomes favorable. J Immunother Canc (2019) 7(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0527-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kichenadasse G, Miners JO, Mangoni AA, Rowland A, Hopkins AM, Sorich MJ. Association between body mass index and overall survival with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol (2020) 6(4):512–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.5241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ichihara E, Harada D, Inoue K, Sato K, Hosokawa S, Kishino D, et al. The impact of body mass index on the efficacy of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Canc (2020) 139:140–5. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McQuade JL, Daniel CR, Hess KR, Mak C, Wang DY, Rai RR, et al. Association of body-mass index and outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or chemotherapy: A retrospective, multicohort analysis. Lancet Oncol (2018) 19(3):310–22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30078-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Spyrou N, Vallianou N, Kadillari J, Dalamaga M. The interplay of obesity, gut microbiome and diet in the immune check point inhibitors therapy era. Semin Cancer Biol (2021) 73:356–76. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nghiem P, Kaufman HL, Bharmal M, Mahnke L, Phatak H, Becker JC. Systematic literature review of efficacy, safety and tolerability outcomes of chemotherapy regimens in patients with metastatic merkel cell carcinoma. Future Oncol (2017) 13(14):1263–79. doi: 10.2217/fon-2017-0072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaae J, Hansen AV, Biggar RJ, Boyd HA, Moore PS, Wohlfahrt J, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Incidence, mortality, and risk of other cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst (2010) 102(11):793–801. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harms PW, Harms KL, Moore PS, DeCaprio JA, Nghiem P, Wong MKK, et al. The biology and treatment of merkel cell carcinoma: Current understanding and research priorities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2018) 15(12):763–76. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0103-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, Blom A, Bataille V, Dreno B, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Canc (2022) 171:203–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kaufman HL, Russell J, Hamid O, Bhatia S, Terheyden P, D'Angelo SP, et al. Avelumab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic merkel cell carcinoma: A multicentre, single-group, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol (2016) 17(10):1374–85. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30364-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walocko FM, Scheier BY, Harms PW, Fecher LA, Lao CD. Metastatic merkel cell carcinoma response to nivolumab. J Immunother Canc (2016) 4:79. doi: 10.1186/s40425-016-0186-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim S, Wuthrick E, Blakaj D, Eroglu Z, Verschraegen C, Thapa R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab with or without stereotactic body radiation therapy for advanced merkel cell carcinoma: A randomised, open label, phase 2 trial. Lancet (2022) 400(10357):1008–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01659-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Russo A, Incorvaia L, Malapelle U, Del Re M, Capoluongo E, Vincenzi B, et al. The tumor-agnostic treatment for patients with solid tumors: A position paper on behalf of the AIOM- SIAPEC/IAP-SIBioC-SIF Italian scientific societies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol (2021) 165:103436. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Santoni M, Massari F, Bracarda S, Procopio G, Milella M, De Giorgi U, et al. Body mass index in patients treated with cabozantinib for advanced renal cell carcinoma. A New Prognost Factor? Diagnost (Basel) (2021) 11(1):138. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11010138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vincenzi B, Badalamenti G, Armento G, Silletta M, Spalato Ceruso M, Catania G, et al. Body mass index as a risk factor for toxicities in patients with advanced soft-tissue sarcoma treated with trabectedin. Oncology (2018) 95(1):1–7. doi: 10.1159/000487266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang Z, Aguilar EG, Luna JI, Dunai C, Khuat LT, Le CT, et al. Paradoxical effects of obesity on T cell function during tumor progression and PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Nat Med (2019) 25(1):141–51. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0221-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Honrubia-Peris B, Garde-Noguera J, García-Sánchez J, Piera-Molons N, Llombart-Cussac A, Fernández-Murga ML. Soluble biomarkers with prognostic and predictive value in advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) (2021) 13(17):4280. doi: 10.3390/cancers13174280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dong X, Ding S, Yu M, Niu L, Xue L, Zhao Y, et al. Small nuclear RNAs (U1, U2, U5) in tumor-educated platelets are downregulated and act as promising biomarkers in lung cancer. Front Oncol (2020) 10:1627. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nilsson RJ, Balaj L, Hulleman E, van Rijn S, Pegtel DM, Walraven M, et al. Blood platelets contain tumor-derived RNA biomarkers. Blood (2011) 118(13):3680–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sol N, Wurdinger T. Platelet RNA signatures for the detection of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev (2017) 36(2):263–72. doi: 10.1007/s10555-017-9674-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leto G, Incorvaia L, Flandina C, Ancona C, Fulfaro F, Crescimanno M, et al. Clinical impact of cystatin C/Cathepsin l and Follistatin/Activin a systems in breast cancer progression: A preliminary report. Cancer Invest (2016) 34(9):415–23. doi: 10.1080/07357907.2016.1222416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Best MG, Wesseling P, Wurdinger T. Tumor-educated platelets as a noninvasive biomarker source for cancer detection and progression monitoring. Cancer Res (2018) 78(13):3407–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lu L, Su Z, Zheng P, Wu Z, Zhang Y, He H, et al. Association between platelet count and hepatocellular carcinoma overall survival: A large retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open (2020) 10(11):e038172. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brown KM, Domin C, Aranha GV, Yong S, Shoup M. Increased preoperative platelet count is associated with decreased survival after resection for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Am J Surg (2005) 189(3):278–82. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brockmann MA, Giese A, Mueller K, Kaba FJ, Lohr F, Weiss C, et al. Preoperative thrombocytosis predicts poor survival in patients with glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol (2007) 9(3):335–42. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Inoue K, Kohashikawa K, Suzuki S, Shimada M, Yoshida H. Prognostic significance of thrombocytosis in renal cell carcinoma patients. Int J Urol (2004) 11(6):364–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00808.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang H, Li C, Yang R, Jin J, Liu D, Li W. Prognostic value of the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in lung cancer patients receiving immunotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One (2022) 17(5):e0268288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lu X, Wan J, Shi H. Platelet-to-lymphocyte and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios are associated with the efficacy of immunotherapy in stage III/IV non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett (2022) 24(2):266. doi: 10.3892/ol.2022.13386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guida M, Bartolomeo N, Quaresmini D, Quaglino P, Madonna G, Pigozzo J, et al. Basal and one-month differed neutrophil, lymphocyte and platelet values and their ratios strongly predict the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors immunotherapy in patients with advanced BRAF wild-type melanoma. J Transl Med (2022) 20(1):159. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03359-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rachidi S, Metelli A, Riesenberg B, Wu BX, Nelson MH, Wallace C, et al. Platelets subvert T cell immunity against cancer via GARP-TGFβ axis. Sci Immunol (2017) 2(11):eaai7911. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aai7911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Incorvaia L, Rinaldi G, Badalamenti G, Cucinella A, Brando C, Madonia G, et al. Prognostic role of soluble PD-1 and BTN2A1 in overweight melanoma patients treated with nivolumab or pembrolizumab: Finding the missing links in the symbiotic immune-metabolic interplay. Ther Adv Med Oncol (2023) 15(15):17588359231151845. doi: 10.1177/17588359231151845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.