Abstract

Human in vitro oogenesis provides a framework for clarifying the mechanism of human oogenesis. To create its benchmark, it is vital to promote in vitro oogenesis using a model physiologically close to humans. Here, we establish a foundation for in vitro oogenesis in cynomolgus (cy) monkeys (Macaca fascicularis): cy female embryonic stem cells harboring one active and one inactive X chromosome (Xa and Xi, respectively) differentiate robustly into primordial germ cell‐like cells, which in xenogeneic reconstituted ovaries develop efficiently into oogonia and, remarkably, further into meiotic oocytes at the zygotene stage. This differentiation entails comprehensive epigenetic reprogramming, including Xi reprogramming, yet Xa and Xi remain epigenetically asymmetric with, as partly observed in vivo, incomplete Xi reactivation. In humans and monkeys, the Xi epigenome in pluripotent stem cells functions as an Xi‐reprogramming determinant. We further show that developmental pathway over‐activations with suboptimal up‐regulation of relevant meiotic genes impede in vitro meiotic progression. Cy in vitro oogenesis exhibits critical homology with the human system, including with respect to bottlenecks, providing a salient model for advancing human in vitro oogenesis.

Keywords: epigenetic reprogramming, in vitro oogenesis, meiotic prophase, primates, X‐chromosome reprogramming

Subject Categories: Development, Methods & Resources, Stem Cells & Regenerative Medicine

In vitro maturation of monkey pluripotent stem cells into fetal oocytes provides a unique model for advancing human oogenesis.

Introduction

Germ cells are a source of totipotency and evolution. They function for the generation of new individuals, thereby propagating and diversifying genetic and epigenetic information across generations. On the other hand, anomalies in germ‐cell development result in critical consequences, including infertility and genetic/epigenetic disorders of offspring. Human in vitro gametogenesis (IVG) aims at reconstituting multi‐stepped human oogenic or spermatogenic development in vitro using pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) as a starting material (Saitou & Hayashi, 2021). IVG will provide a vital tool for elucidating the mechanism of human germ cell development, including the disease states, as well as for opening up novel therapeutic possibilities.

For the reconstitution of human oogenic development, based on the concepts underlying in vitro oogenesis in mice (Hayashi et al, 2012; Hikabe et al, 2016), human PSCs (hPSCs) are first induced into human primordial germ cell‐like cells (hPGCLCs; Irie et al, 2015; Sasaki et al, 2015; Yokobayashi et al, 2017), which, upon aggregation with mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells [xenogeneic reconstituted ovaries (xrOvaries)], differentiate into oogonia with epigenetic reprogramming and then into early oocyte‐like cells in preparation for meiotic recombination [“retinoic acid (RA)‐responsive” cell‐like cells, corresponding to the pre‐leptotene stage prior to the first meiotic prophase] (Li et al, 2017; Yamashiro et al, 2018, 2020). On the other hand, the efficiency for the differentiation of hPGCLCs into oogonia and RA‐responsive cell‐like cells in xrOvaries under the current condition is generally low, and the precise mechanisms underlying the progression and the arrest of the oogenic pathway remain unclear (Yamashiro et al, 2018, 2020).

For the goal of promoting human in vitro oogenesis, a key parameter requiring careful evaluation is the activity of X chromosomes. Females have two copies of gene‐rich X chromosomes, whereas males bear one X and one gene‐poor Y chromosome. To ensure a balanced X‐chromosome gene dosage between the sexes, epigenetic mechanisms inactivate one X chromosome (Xi) in females early in development (Lyon, 1961; Ohno, 1967; Zylicz & Heard, 2020). Concurrently, to compensate for the X chromosome:autosome (X:A) gene dosage, one active X chromosome (Xa) gains hyperactivation (X‐chromosome up‐regulation: XCU) in both females and males (Ohno, 1967; Deng et al, 2014; Larsson et al, 2019). As a result, somatic cells acquire and maintain one hyperactive Xa and one Xi. On the other hand, in female germ cells, epigenetic reprogramming reactivates Xi (X‐chromosome reactivation: XCR) and erases XCU on Xa, and consequently, fetal oocyte development proceeds with two Xa with little/no XCU, a dosage compensation state unique to fetal oocytes (Monk & McLaren, 1981; Tam et al, 1994; Sugimoto & Abe, 2007; Sangrithi et al, 2017; Vertesy et al, 2018; Chitiashvili et al, 2020; Mizuta et al, 2022). This reprogramming is critical not only for oocyte development but also, upon meiosis, for passing on an epigenetically equivalent X chromosome to the next generation (Monk & McLaren, 1981; Tam et al, 1994; Sugimoto & Abe, 2007; Vertesy et al, 2018). While hPSCs typically bear one hyperactive Xa and one Xi, they exhibit substantial epigenetic instability on Xi (Mekhoubad et al, 2012; Nazor et al, 2012; Vallot et al, 2015; Patel et al, 2017; Sahakyan et al, 2017; Bar et al, 2019; Yokobayashi et al, 2021), and the impact of such instability on human in vitro oogenesis remains unclarified. Thus, more detailed characterization and further development of human in vitro oogenesis are important areas of investigation.

As a parallel effort, in order to further foster human in vitro oogenesis while simultaneously creating a benchmark for its critical assessment, it is important to promote in vitro oogenesis research using a model with close physiology to humans, such as non‐human primates. Such investigations will also provide evolutionary insight into the mechanism of mammalian germ cell development. Cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis; cy) are a primate closely related to humans (~8 million years of evolutionary difference from humans) and are a robust model for various biomedical investigations, including studies on developmental biology (Nakamura et al, 2021). They are thus highly suitable for use in in vitro oogenesis research. Accordingly, cyPSCs have been induced into cyPGCLCs (Sakai et al, 2019), and a recent study has shown that cy fetal oocyte development involves transcriptome dynamics similar to those in humans and that cy and human fetal ovarian reaggregates undergo appropriate maturation under the same in vitro culture condition, during which oogonia enter and complete the meiotic prophase, that is, mitotic oogonia differentiate into “RA‐responsive” (pre‐leptotene/leptotene), “meiotic” (zygotene/pachytene), and “oogenic” (diplotene) cells to form primordial follicles with granulosa cells in vitro (Mizuta et al, 2022).

Building on the above rationale/findings, we here set out to conduct in vitro oogenesis in cynomolgus monkeys. We found that in xrOvaries, cyPGCLCs differentiate rapidly into oogonia, then into “RA‐responsive” cell‐like cells, and then, remarkably, into “meiotic” cell‐like cells at the zygotene/pachytene stage. The progression from cyPGCLCs to oogonia to fetal oocyte‐like cells entails complete epigenetic reprogramming and broadly normal X‐chromosome dosage compensation. Nonetheless, Xi reactivation is partial, and characteristic epigenetic asymmetry remains between Xa and Xi, which is also partly observed in vivo. Based on a comparison between cy fetal oocyte‐like cells and human oogonia‐like cells, we then defined the Xi epigenetic state in PSCs as an Xi reprogramming determinant. Finally, a single‐cell transcriptome analysis delineated an in vitro versus in vivo transcriptome divergence upon oogonia‐to‐oocytes transition, with the in vitro pathway over‐activating a distinctive developmental program with suboptimal up‐regulation of some “RA‐responsive”/“meiotic” genes. Thus, by creating a foundation for cy in vitro oogenesis, our study uncovered the critical homology between human and cy in vitro oogenesis, including their bottlenecks, providing critical insights for advancing human in vitro oogenesis.

Results

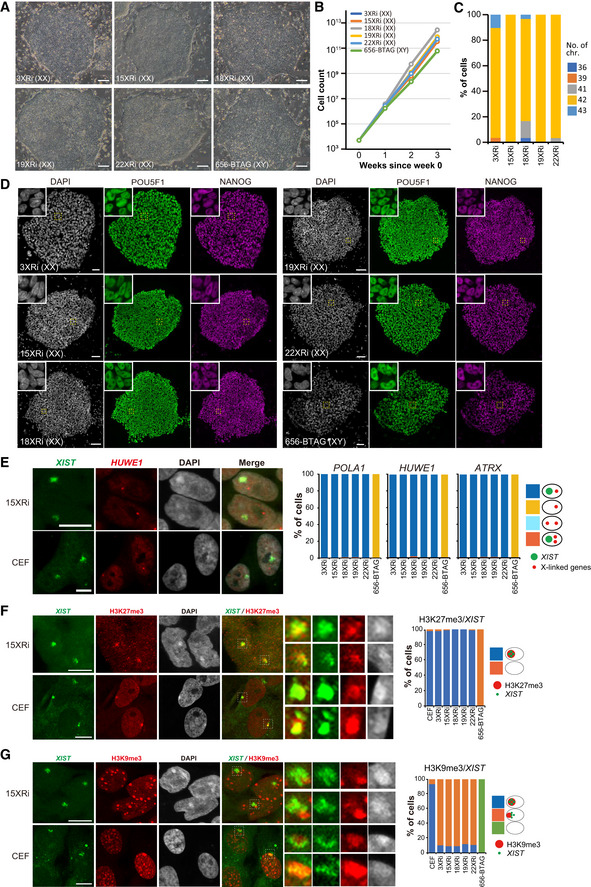

Female cyESCs stably maintain one Xa and one Xi

To set out to conduct in vitro oogenesis in cynomolgus monkeys, we derived five independent female cyESC lines (3/15/18/19/22XRi lines) and cultured them in a primed state of pluripotency (see Materials and Methods; Sakai et al, 2019). Under this condition, all five lines (passage numbers 6–18, Dataset EV9) as well as one male line that bears a robust competence for cyPGCLC induction [656 Blimp1‐tdTomato:TFAP2C‐EGFP (BTAG) #42] (passage numbers 34–35, Dataset EV9; Sakai et al, 2019) formed flat and compacted colonies and grew exponentially with the maintenance of normal karyotype (Fig 1A–C). All lines uniformly expressed the key pluripotency markers POU5F1, SOX2, and NANOG (Fig 1D, Appendix Fig S1A).

Figure 1. Female cyESC lines and their X‐chromosome properties.

-

APhase‐contrast images of five female (XX: 3/15/18/19/22XRi) cyESC lines and one male (XY: 656‐BTAG) cyESC line. Scale bars, 100 μm.

-

BGrowth curve of the cyESC lines. cyESCs were passaged every week (circles).

-

CKaryotype of the female cyESC lines. cyESCs were passaged 6–18 times before analysis. Thirty nuclei were analyzed for quantification for each line.

-

DImmunofluorescence (IF) images of cyESC colonies stained for pluripotency markers (POU5F1, NANOG). The colonies were counterstained with DAPI. Magnified images of the dotted boxed areas are shown in the insets. Scale bars, 100 μm.

-

E−GX‐chromosome properties of cyESC lines and cy embryonic fibroblasts (CEFs). (E) XIST (green), and HUWE1 (red) expression analyzed by RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (RNA‐FISH). Representative images for 15XRi and CEFs are shown. The bar graphs, including the data for POLA1 and ATRX, show the percentages of cells with the indicated staining patterns. (F and G) XIST expression (green) and histone modifications (red) [H3K27me3 (F) and H3K9me3 (G)] analyzed by RNA‐FISH followed by IF. Representative images for 15XRi and CEFs are shown. Representative XIST‐positive areas (X chromosomes, dotted boxed areas) were magnified in the right panels. The bar graphs show the percentages of cells with the indicated staining patterns (n = 100 nuclei in each cell line). Scale bars, 10 μm.

Source data are available online for this figure.

To examine their X‐chromosome states, we performed RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (RNA FISH) for XIST (X‐inactive‐specific transcript), the long non‐coding RNA that is typically expressed from and marks Xi (Brockdorff et al, 1992; Brown et al, 1992; Okamoto et al, 2011, 2021), and three representative X‐linked genes, POLA1, HUWE1, and ATRX, which are expressed from Xa. In nearly all nuclei in the female lines (passage numbers 9–21, Dataset EV9), XIST was detected as a single, relatively diffuse signal and localized in the DAPI‐dense area, most likely Xi, whereas the X‐linked genes were detected as single punctate signals with distinct localizations from XIST, most likely on Xa (Fig 1E, Appendix Fig S1B). The expression/localization of XIST and the X‐linked genes in cyESCs were similar to those in female cy embryonic fibroblasts (CEFs), except that in CEFs, the XIST signals were more compact and more frequently associated with the nuclear periphery with high DAPI density (Xi; Fig 1E, Appendix Fig S1B). We performed XIST RNA FISH followed by immunofluorescence (IF) analysis for two representative repressive histone modifications, histone H3 lysine 27 tri‐methylation (H3K27me3) and histone H3 lysine 9 tri‐methylation (H3K9me3). In CEFs, Xi with an XIST coating and high DAPI density was enriched with both H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 (Fig 1F and G). Notably, in nearly all nuclei in female cyESCs (passage numbers 9–21, Dataset EV9), H3K27me3 was strongly enriched in the XIST‐positive areas, whereas H3K9me3 did not show such an enrichment, but was often localized to a periphery of the XIST‐positive domains (Fig 1F and G, Appendix Fig S1C and D). Full‐length RNA sequencing analysis verified that the five female cyESCs expressed XIST and the X‐linked genes at a similar level (Appendix Fig S1E). Thus, unlike typical human female PSCs, all female cyESCs cultured under our condition bear one Xa and stably maintain one Xi, which is associated with a high level of H3K27me3 but not H3K9me3.

cyPGCLCs differentiate robustly into oogonia with faster kinetics than hPGCLCs

To induce cyPGCLCs, we cultured five female cyESC lines and one male cyESC line under a floating condition in the presence of key cytokines including bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4; Sakai et al, 2019; Appendix Fig S2A). On day 8 (d8) of induction, we performed fluorescence‐activated cell sorting (FACS) by surface markers for cyPGCLCs, PDPN, and ITGA6 (Sakai et al, 2019), which revealed that cyPGCLC induction efficiency varied among the cyESC lines: 3/15/22XRi showed a high induction efficiency comparable to that of the male line (~40–70%), whereas 18/19XRi exhibited a lower efficiency (~10–30%; Appendix Fig S2B and C). The PDPN‐positive(+)/ITGA6+ cells expressed key pluripotency markers (POU5F1, NANOG) and transcription factors for cyPGC specification (SOX17, TFAP2C, PRDM1), but were negative for oogonia markers (DDX4, DAZL; Appendix Fig S2D). IF analyses of the floating aggregates gave a consistent result (Appendix Fig S2E).

We next explored whether, like hPGCLCs (Yamashiro et al, 2018, 2020), cyPGCLCs differentiate into oogonia in xrOvaries with mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells. We sorted d8 PDPN+/ITGA6+ cells induced from the five female lines and BT+AG+ cells induced from the male line (5,000 cells), aggregated them with mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells at embryonic day (E) 12.5 (75,000 cells), and following aggregate formation under a floating condition for 2 days, transferred the aggregates to an air–liquid interface culture (Appendix Fig S2A). All xrOvaries maintained an integrated morphology at least until around day 21 of the air–liquid interface culture (ag21), but some began to exhibit a disintegrated morphology, presumably due to de‐differentiation of PDPN+/ITGA6+ cells, from around ag28, and all xrOvaries with PDPN+/ITGA6+ cells from the 3XRi line showed highly aberrant morphology with extensive expansion of de‐differentiated cells by ag35 (Appendix Fig S3A). Nonetheless, a substantial fraction of xrOvaries with PDPN+/ITGA6+ cells from the other lines remained integrated at least until ag35 (Appendix Fig S3A). All xrOvaries with BT+AG+ cells from the male line showed an integrated morphology until ag35 (Appendix Fig S3A).

We performed IF analyses to examine the differentiation of the PDPN+/ITGA6+ cell‐derived cells, which are positive for human mitochondrial antigen (hMit), in xrOvaries at ag35, except those xrOvaries containing the 3XRi‐derived cells. All xrOvaries contained many TFAP2C+ cells (Appendix Fig S3B and D), and while the TFAP2C+/hMit+ cell ratio was high in xrOvaries with BT+AG+ cells from the male line (~80% on average), it was relatively low in xrOvaries with PDPN+/ITGA6+ cells from the female lines (~10–55% on average; Appendix Fig S3D), confirming the notion that some PDPN+/ITGA6+ cells de‐differentiate into TFAP2C‐negative(−) non‐cyPGCLCs in xrOvaries. On the other hand, remarkably, a substantial fraction (~5–20%) of the TFAP2C+ cells in all xrOvaries expressed DDX4 (Appendix Fig S3C and D), indicating that cyPGCLCs differentiate into oogonia with faster kinetics than hPGCLCs, which exhibit an equivalent differentiation only after ag77 (Yamashiro et al, 2018, 2020).

cyPGCLCs differentiate into oocyte‐like cells at the zygotene stage of the meiotic prophase

To more precisely examine the differentiation dynamics of cyPGCLCs in xrOvaries, we isolated cyESC lines expressing EGFP and tdTomato under the control of TFAP2C and DDX4, respectively [TFAP2C‐EGFP; DDX4 (cy vasa homologue)‐tdTomato (AGVT)], using the CRISPR/Cas9‐based homologous recombination technology (Cong et al, 2013; Appendix Fig S4A and B). We used 15XRi as the parental line, since it differentiates into cyPGCLCs and then into DDX4+ oogonia at a high efficiency, with a modest de‐differentiation in xrOvaries (Appendix Fig S3D). We cloned two independent AGVT lines (15XRi AGVT #7 and #105; passage numbers 15–25; Dataset EV9), which showed a normal karyotype and were robustly induced into AG+ cyPGCLCs (Appendix Fig S4C–F).

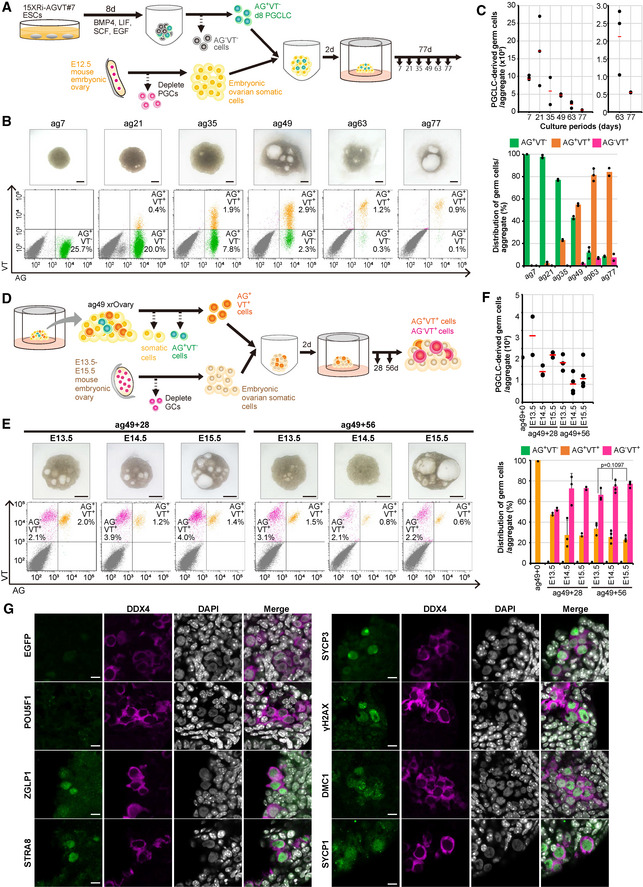

We generated xrOvaries with d8 AG+VT− cells (d8 cyPGCLCs) from the 15XRi AGVT #7 line (Fig 2A). At ag7, the xrOvaries showed a round, compacted morphology, and FACS analysis revealed the presence of an abundant number of AG+VT− cyPGCLCs (~10,000 cells/xrOvary; Fig 2B and C). At ag21, the xrOvaries became enlarged in size with increased numbers of AG+VT− cyPGCLCs (~17,000 cells/xrOvary) and, notably, incipient AG+VT+ oogonial cells (AG+VT+/AG+: ~2%; Fig 2B and C). At ag35, the xrOvaries appeared to somewhat flatten at their peripheries, and the AG+ cell number declined (~5,000 cells/xrOvary), but with an increase of AG+VT+ cells (AG+VT+/AG+: ~20%; Fig 2B and C). At ag49, the xrOvaries maintained a similar structure but with several cystic enlargements, and the AG+ cell number remained relatively constant (~5,000 cells/xrOvary) with a further increase of AG+VT+ cells (AG+VT+/AG+: > ~50%; Fig 2B and C). At ag63 and 77, the AG+ cell number declined substantially (~2,000 and 500 cells/xrOvary, respectively), with the majority being AG+VT+ and a small number of the cells differentiated into the AG−VT+ state (Fig 2C). In good agreement with this finding, IF analysis at ag77 revealed that a majority of DDX4+ cells expressed EGFP (AG) and were negative for “RA‐responsive” (SYCP3) or “meiotic” (γH2AX/DMC1/SYCP1) markers, indicating their oogonia identity (Appendix Fig S5A). Compared to the xrOvaries with PDPN+/ITGA6+ cells, those with d8 AG+VT− cells showed a lesser tendency for disintegration (Fig 2B, Appendix Fig S3A), most likely because AG+VT− cells represent a purer population of cyPGCLCs.

Figure 2. Induction of cyPGCLCs and their differentiation in xrOvaries.

- Scheme of xrOvary culture. cyPGCLCs induced from the 15XRi AGVT line were aggregated with mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells at E12.5 (xrOvaries) and cultured as indicated.

- (top) Bright‐field images of xrOvaries at the indicated time points. Scale bars, 1 mm. (bottom) AGVT expression dynamics analyzed by FACS. Percentages (/all live cells in xrOvaries) of germ cells with the indicated expression profiles are indicated.

- (top) Numbers of cyPGCLC‐derived germ cells/xrOvary at the indicated time points. Red lines indicate the average of two or three biological replicates. (bottom) Percentages of the indicated cells/germ cells. Standard deviations (SDs) are shown as error bars. Total numbers of cyPGCLC‐derived germ cells and AG+VT−/AG+VT+/AG−VT+ proportions were plotted based on the quantification of whole xrOvaries by FACS analysis. Dots represent individual data points of two or three biological replicates.

- Scheme of xrOvary passage culture. AG+VT+ cells in xrOvaries at ag49 were re‐aggregated with mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells at E13.5/14.5/15.5 and cultured for an additional 28 or 56 days (ag49+28 or +56).

- (top) Bright‐field images of xrOvaries at ag49+28 or +56 with mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells at the indicated embryonic days. Scale bars, 2 mm. (bottom) AGVT expression dynamics analyzed by FACS. Percentages (/all live cells in xrOvaries) of germ cells with the indicated expression profiles are indicated.

- (top) Numbers of AG+VT+ cell‐derived cells/xrOvary at the indicated time points. Red lines indicate the average of two or more biological replicates. (bottom) Percentages of the indicated cells/germ cells. SDs are shown as error bars. Total numbers of cyPGCLC‐derived germ cells and AG+VT−/AG+VT+/AG−VT+ proportions were plotted based on the quantification of whole xrOvaries by FACS analysis. The P‐value was calculated using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The numbers of xrOvaries analyzed were 2, 3, 2, 3, 4, and 4 for ag49+28 and +56 xrOvaries with E13.5, E14.5, and E15.5 mouse ovarian somatic cells. Dots represent individual data points.

- Representative IF images for the indicated marker expression in xrOvaries at ag49+56 with mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells at E13.5. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Since the integrity/quality of xrOvary culture declined after ag49, we explored whether a passage of cyPGCLC‐derived cells in xrOvaries with mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells at later developmental stages would promote further differentiation of cyPGCLC‐derived cells. We dissociated xrOvaries at ag49 into single cells, sorted AG+VT+ cells, and re‐aggregated them with mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells at E13.5, E14.5, or E15.5 (2,500 ag49 AG+VT+ cells and 75,000 mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells; Fig 2D). At 28 days after the passage (ag49+28), all xrOvaries appeared healthy and exhibited an integrated morphology, and FACS analysis revealed that the number of AG+VT+ cell‐derived cells was increased/maintained (~2,000–4,000 cells/xrOvary) and, notably, a majority of AG+VT+ cells differentiated into AG−VT+ cells (Fig 2E and F). At ag49+56, all xrOvaries remained apparently healthy, while the number of AG+VT+ cell‐derived cells declined (~1,000–2,000 cells/xrOvary), with most of them being in the AG−VT+ state and with an increase in VT highly positive (VTh+) cells (Fig 2E and F). We noted a tendency for AG+VT+ cells to differentiate into AG+VT− cells at faster kinetics in xrOvaries with E14.5 and E15.5 mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells (Fig 2E and F). On the other hand, IF analysis at ag49+56 revealed that in all xrOvaries, most DDX4+ cells were negative for EGFP (AG) and POU5F1, and some were positive for “RA‐responsive” (ZGLP1/STRA8/SYCP3) or “meiotic” (γH2AX/DMC1/SYCP1) markers, with the acquisition of condensed, thread‐like chromatin (Fig 2G, Appendix Fig S5B; also see below). These findings indicate that AG+VT+ cells differentiate into AG−VT+ cells, and some of them enter the meiotic prophase in xrOvaries with mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells at E13.5, E14.5, and E15.5.

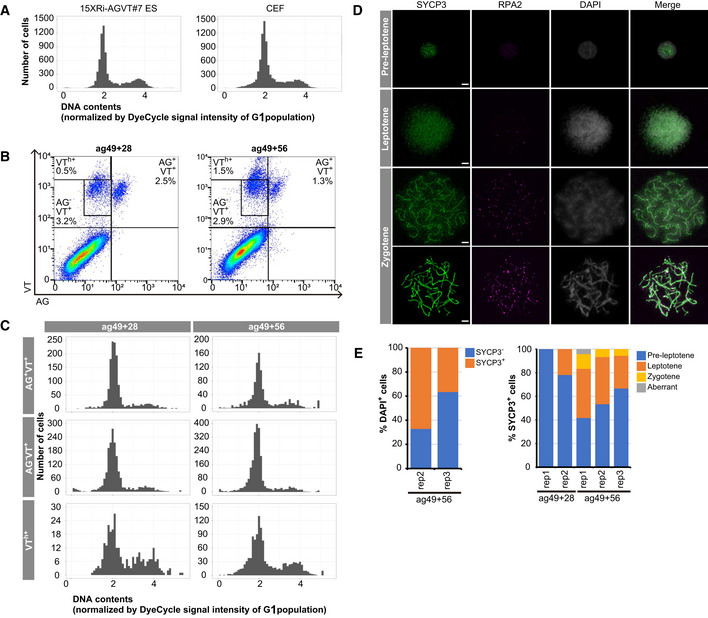

To explore this point further, we analyzed the cell cycle state of the AG+VT+ and AG−VT+ cells at ag49+28 and ag49+56 (we used E14.5 and E15.5 mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells for xrOvary formation). The distributions of DNA contents of these cells were similar to each other and to those of cyESCs and CEFs, with a majority being in the G1 phase (~78%) and a minority in the S/G2/M phases (~22%; Fig 3A−C), indicating that cells in the meiotic prophase with 4N are a minor population. Notably, however, the VTh+ cells at both ag49+28 and ag49+56 were enriched with 4N cells, with an increase in such cells at ag49+56 (Fig 3B and C). We then performed a spread analysis of the meiotic state of AG−VT+ cells at ag49+28 and ag49+56. At ag49+28, a great majority of SYCP3+ cells (~80%) expressed SYCP3 diffusely throughout their nuclei, did not show characteristic chromatin pairing, and were negative for RPA2, a key component of the RPA complex that binds to single‐stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs of DNA double‐strand breaks (DSBs) created upon meiotic recombination (Brown & Bishop, 2014; Hinch et al, 2020), and were considered to be in the pre‐leptotene stage (Fig 3D and E). On the other hand, the remaining SYCP3+ cells (~22%) exhibited numerous thread‐like SYCP3 localizations for chromatin pairings and a number of RPA2+ foci, indicating that they are in the leptotene stage (Fig 3D and E). At ag49+56, among SYCP3+ cells (36–67%/AG−VT+ cells), 42–67% were in the pre‐leptotene and 28–42% were in the leptotene stage, and remarkably, 5–13% showed typical SYCP3+ synaptonemal complex structures and many RPA2+ foci along the chromatin, which are characteristics of the zygotene stage (Fig 3D and E). Collectively, these results led us to conclude that in xrOvaries, cyPGCLCs differentiate robustly into oogonia and then enter the meiotic prophase, progressing at least up to the zygotene stage.

Figure 3. Progression of the meiotic prophase by cyPGCLC‐derived cells.

- Distributions of DNA contents in cyESCs (15XRi‐AGVT#7) and CEFs. DyeCycle signal intensity was normalized with that of the G1 cells (i.e., 2N cells).

- AGVT expression analyzed by FACS of cyPGCLC‐derived cells in xrOvaries at ag49+28 and +56. Percentages (/all live cells in xrOvaries) of the indicated cells are shown. Mouse embryonic somatic cells at E15.5 were used. VTh +: VT highly positive.

- Distributions of DNA contents in the indicated cells. Representative plots of three independent experiments are shown. Mouse embryonic somatic cells at E15.5 were used.

- Representative images of chromosome spreads of AG−VT+ cells at ag49+56 stained with SYCP3 (green) and RPA2 (magenta). The cells were classified as pre‐leptotene, leptotene, zygotene, or aberrant (as in E). Mouse embryonic somatic cells at E14.5 or E15.5 were used. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- (left) Percentages of SYCP3+ or SYCP3− cells/all AG−VT+ and DAPI+ cells at ag49+56. Mouse embryonic somatic cells at E14.5 (rep2) and E15.5 (rep3) were used. For quantification, 351 (rep2) and 131 (rep3) nuclei were analyzed. (right) Percentages of the indicated cells in xrOvaries at ag49+28 and ag49+56. Mouse embryonic somatic cells at E14.5 (rep1 and 2) and E15.5 (rep3) were used. For quantification, 12–54 SYCP3+ nuclei were analyzed for each biological replicate.

Source data are available online for this figure.

A transcriptome diversification upon oogonia‐to‐oocytes transition in vitro

Global transcriptome

To explore the transcriptome basis of the development from cyPGCLCs to oogonia to fetal oocyte‐like cells, we performed RNA sequence (RNA‐seq) analysis of the relevant cell types [cyESCs, d8 cyPGCLCs, ag7/21/35 AG+VT− cells, ag35/49/77 AG+VT+ cells, and ag49+52 AG−VT+ cells (with E13.5, E14.5, and E15.5 mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells)], as well as cy germ cells at 8 weeks post‐fertilization (8 wpf), which consisted predominantly of oogonia (Mizuta et al, 2022), isolated from dissociated cy ovaries using PDPN and c‐KIT as surface markers. When the cells were sorted in this manner, germ cells accounted for ~60–80% of the sorted cells, with the remaining ~20–40% being ovarian somatic cells (Appendix Fig S6A and B). Thus, the data from this cell population are not only primarily representative of oogonia but also provide some information arising from minor somatic cell contamination; note that ovarian somatic cells are much smaller in volume and contain fewer transcripts than oogonia (Mizuta et al, 2022), and thus the impact of somatic cell contamination on the transcriptome would be minor.

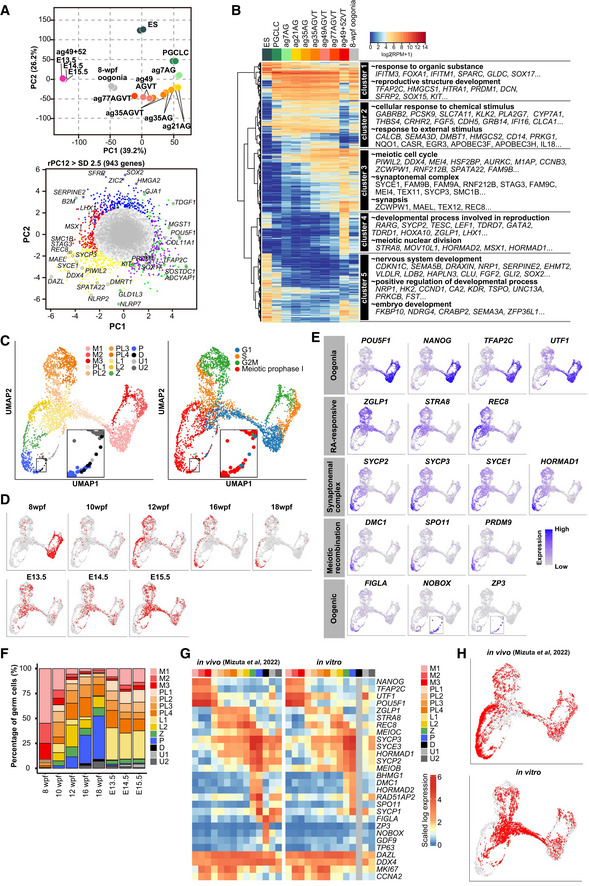

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering (UHC) classified these cells into four major clusters that represent cyESCs, cyPGCLCs (d8, ag7/21/35 AG+VT−), oogonia (ag35/49/77 AG+VT+, germ cells at 8 wpf), and fetal oocyte‐like cells (ag49+52 AG−VT+), respectively (Appendix Fig S6C). Principal component analysis (PCA) delineated a pathway for their developmental progression and highlighted the acquisition of a distinct transcriptome in fetal oocyte‐like cells (ag49+52 AG−VT+; Fig 4A). We determined the 943 genes with significantly positive or negative scores of PC1 and PC2 loading [standard deviation (SD) > 2.5] (Fig 4A), which were classified roughly into five clusters that exhibited characteristic expression during the progression from cyPGCLCs to oogonia to fetal oocyte‐like cells (Fig 4B). In particular, ag49+52 AG−VT+ cells expressed the cluster 3 and 4 genes at a high level, which were enriched with genes for gene ontology (GO) terms such as “meiotic cell cycle,” “developmental process involved in reproduction,” and “meiotic nuclear division” (Fig 4B, Dataset EV2), in accord with the notion that they represent fetal oocyte‐like cells in preparation for or in the meiotic prophase.

Figure 4. Transcriptome dynamics during the development of cyESCs to fetal oocyte‐like cells.

- (top) PCA of the transcriptomes of cyESC‐derived cells and cy oogonia [cell populations enriched with cy oogonia at 8 weeks post‐fertilization (wpf)]. (bottom) Scatter plot of the normalized loading scores of PCA. Genes bearing PC1/2 loading scores ± 2.5 SDs are colored according to the clusters in (B): green: cluster 1; purple: cluster 2; yellow: cluster 3; red: cluster 4; blue: cluster 5. Key genes are annotated on the plot. AG: AG+VT−; AGVT: AG+VT+; VT: AG−VT+.

- (left) UHC and heatmap of the expression of the 943 genes in (A, bottom). The average expression levels in two biological replicates except in the case of ag77 (one replicate) and ag49+52 (three replicates) are shown. The color coding is as indicated. (right) GO enrichments and representative genes in each cluster.

- UMAP plot and Louvain clustering of cy oogonia/fetal oocytes in vitro and in vivo (Mizuta et al, 2022; left) and their cell cycle stage prediction (right). M: mitotic; PL: pre‐leptotene; L: leptotene; Z: zygotene; P: pachytene; D: diplotene; U: unclassified. Diplotene cells are magnified in the inset. The color coding is as indicated.

- UMAP plot as in (C), with the annotation of in vivo and in vitro cells. wpf: weeks post‐fertilization for in vivo cells (Mizuta et al, 2022); E13.5/14.5/15.5: embryonic days of mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells used for xrOvaries.

- UMAP plot as in (C), with the expression of genes representative of oogonia (POU5F1, NANOG, TFAP2C, UTF1), RA‐responsive cells (ZGLP1, STRA8, REC8), synaptonemal complex (SYCP2, SYCP3, SYCE1, HORMAD1), meiotic recombination (DMC1, SPO11, PRDM9), and oogenic cells (FIGLA, NOBOX, ZP3). Note that TFAP2C+ cells were essentially AG+VT+, while TFAP2C− cells were AG−VT+. The color coding is as indicated.

- Proportion of the 13 clusters in (C) in the indicated samples. For in vivo cells, the averages of two samples are shown for each stage except in the case of 10, 12 and 18 wpf (one replicate). The color coding is as indicated.

- Heatmaps of the expression of key genes associated with cy fetal oocyte development in the 13 clusters in (C). Separate heatmaps are shown for in vivo (left; Mizuta et al, 2022) and in vitro (right) cells. The color coding is as indicated.

Single‐cell transcriptome: Cell‐type classification and developmental progression

To examine the progression of fetal oocyte‐like cell development at a single‐cell resolution, we performed single‐cell RNA‐seq (scRNA‐seq) analysis of ag49+52 xrOvaries with E13.5, E14.5, and E15.5 mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells using a 10X Chromium platform, and analyzed the data in comparison to those of cy fetal oocyte development from 8 to 18 wpf (Mizuta et al, 2022). We processed a total of 18,769 cells in vitro (7,827 AG+VT+/AG−VT+ cells and 10,942 mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells), and with sequencing, 1,986 AG+VT+/AG−VT+ cells passed key quality filters (Appendix Fig S6D, Dataset EV1F; Wolock et al, 2019) and were subject to an integrated analysis with cy fetal oogonia/oocytes in vivo (Mizuta et al, 2022).

Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) for dimensionality reduction and Louvain clustering classified the relevant in vitro and in vivo cells into 13 clusters (Fig 4C−E). Based on the expression of key markers, we annotated them as mitotic 1/2/3, pre‐leptotene 1/2/3/4, leptotene 1/2, zygotene, pachytene, diplotene [some pachytene cells were manually classified as diplotene, as reported previously (Mizuta et al, 2022)], and unclassified (Fig 4C−E). The cell‐type compositions of ag49+52 xrOvaries with E13.5, E14.5, and E15.5 mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells were very similar to each other and similar to those of cy fetal ovaries at ~12 wpf, but with enrichment of pre‐leptotene 1 and leptotene 1 cells (Fig 4D and F).

Mitotic 1/2/3 cells expressed oogonia markers (POU5F1, NANOG, TFAP2C, UTF1) and consisted mainly of in vitro AG+VT+ cells and in vivo cells at 8 wpf, but included in vivo cells from all developmental stages (Fig 4E and F), and were predicted to be primarily in the G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle, respectively (Tirosh et al, 2016; Fig 4C). There were no overt differences in the expression of key markers between in vitro and in vivo mitotic cells (Fig 4G). Pre‐leptotene 1 cells began to repress oogonia markers and to up‐regulate “RA‐responsive” markers (ZGLP1, STRA8, REC8), and were in the G1 phase (Fig 4C, E, and G). Pre‐leptotene 2/3/4 cells more fully repressed oogonia markers, expressed “RA‐responsive” markers, and initiated up‐regulation of genes for the synaptonemal complex, such as SYCP2/3, SYCE1, and HORMAD1, with pre‐leptotene 2 cells mainly in the S phase and pre‐leptotene 3/4 cells mainly in the G2 phase (Fig 4C, E, and G). Pre‐leptotene cells consisted of in vitro AG−VT+ cells and in vivo cells from all developmental stages, with the pre‐leptotene 1 cells being enriched with in vitro cells (Fig 4D and F). Compared to the in vivo cells, the in vitro pre‐leptotene cells were variable in oogonia marker repression and “RA‐responsive”/synaptonemal complex gene expression (Fig 4G). Leptotene 1/2 cells repressed oogonia markers, expressed “RA‐responsive” markers, and up‐regulated synaptonemal complex genes, but were negative/weak for key genes for meiotic recombination, such as DMC1, SPO11, and PRDM9, with leptotene 2 cells expressing “RA‐responsive”/synaptonemal complex genes at a higher level (Fig 4E and G). Leptotene 1 cells consisted nearly exclusively of in vitro cells, whereas the vast majority of leptotene 2 cells were in vivo cells (Fig 4D and F). Accordingly, on the UMAP plots, the developmental trajectories of in vitro and in vivo cells diverged upon pre‐leptotene‐to‐leptotene transition (Fig 4H). Zygotene/pachytene cells up‐regulated key genes for meiotic recombination, with pachytene cells expressing such genes at a higher level; zygotene/pachytene cells consisted predominantly of in vivo cells after 10 wpf (Fig 4D−G). Nonetheless, in accord with the cytologic analysis (Fig 3D and E), ~4% of in vitro cells were classified as zygotene, and notably, a small number of them (25 cells) were classified as pachytene (Fig 4F). On the UMAP plots, in vitro zygotene/pachytene cells were continuous from in vitro leptotene cells, that is, leptotene 1 cells, whereas in vivo zygotene/pachytene cells were continuous from in vivo leptotene cells, that is, leptotene 2 cells (Fig 4C, D, and H). Accordingly, in vitro zygotene/pachytene cells expressed genes for synaptonemal complex/meiotic recombination at lower/more variable levels than in vivo zygotene/pachytene cells (Fig 4G). Diplotene cells maintained genes for the synaptonemal complex, repressed those for meiotic recombination, and began to express “oogenic” genes (FIGLA, NOBOX, ZP3); diplotene cells consisted of in vivo cells at 16 and 18 wpf (Fig 4E−G).

On the UMAP plots, unclassified cells were divided into two clusters, U1 and U2: the U1 cells (nUMI: ~50,000; nGenes: ~8,750) consisted predominantly of in vitro cells, were predicted to be mainly in the G1 phase, and exhibited relatively high correlation with pre‐leptotene/leptotene cells (Fig 4C, D, and F, Appendix Fig S6D and E; see below). We noted that the U1 cells expressed some genes characterizing “oogenic” cells (SOHLH1, ZAR1, NPM2) and, somewhat unexpectedly, genes involved in male germ‐cell development such as NANOS2, PIWIL4, and EGR4 (Li et al, 2017; Hwang et al, 2020; Guo et al, 2021; Appendix Fig S6F). Thus, U1 cells were aberrantly differentiated cells in the xrOvary environment. On the other hand, the U2 cells consisted of both in vitro and in vivo cells and most likely represented low‐quality/aberrant pachytene cells, as they showed fewer nUMI (~10,000)/nGenes (~2,500) and relatively high correlation with pachytene cells, and were predicted to be in the meiotic prophase (Fig 4C, D, and F, Appendix Fig S6D and E; see below).

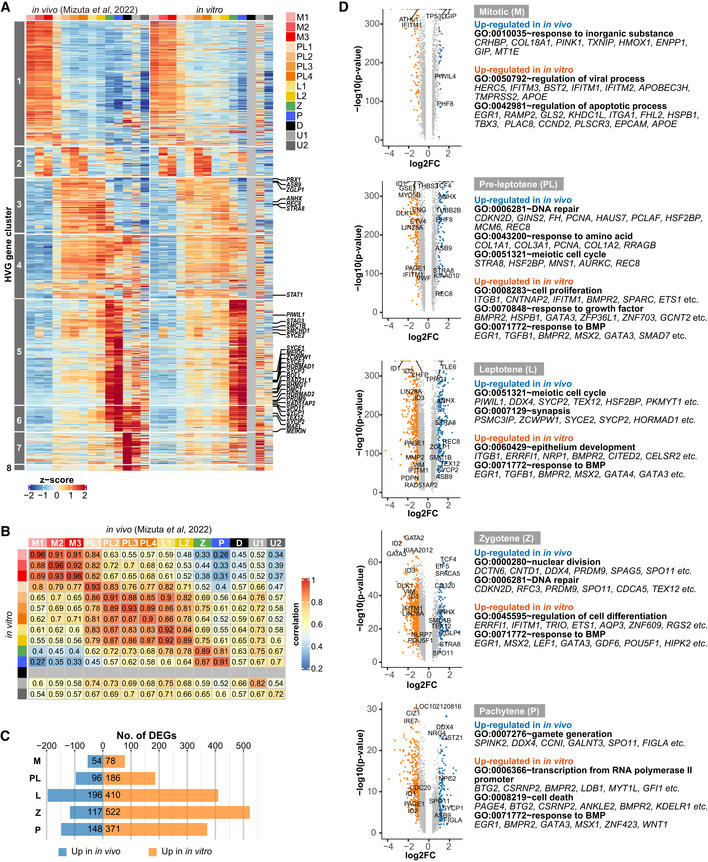

In vitro versus in vivo cell types

To gain further insight into the properties of fetal oocyte‐like cells in vitro, we examined the expression of highly variable genes (HVGs: 1,481 genes) that define the progression of cy fetal oocyte development and consist of eight clusters (Mizuta et al, 2022; Fig 5A). The in vitro and in vivo cells exhibited high concordance for HVG expression until the pre‐leptotene 1 stage (Fig 5A and B), but began to manifest a discernable difference from the pre‐leptotene 2 stage onward, with lower/variable expression of genes up‐regulated in the pre‐leptotene/leptotene cells (cluster 3/4 genes), which were enriched in genes for “regulation of transcription, DNA‐templated,” “pattern specification process,” and “meiotic cell cycle” (Fig 5A and B, Dataset EV3; Mizuta et al, 2022). Nonetheless, in vitro pachytene cells up‐regulated pachytene genes at a high level, which were enriched with those for “synapsis,” “double‐strand break repair,” and “reciprocal DNA recombination” (cluster 5/6 genes), although their expression profiles were somewhat discordant from those of in vivo cells (Fig 5A and B, Dataset EV3; Mizuta et al, 2022).

Figure 5. Comparison of cy oogonia/fetal oocytes in vivo and in vitro .

- Heatmaps of the expression of highly variable genes [HVGs (1,481 genes)] associated with cy fetal oocyte development (Mizuta et al, 2022) in cy oogonia/fetal oocytes in vivo (left) and in vitro (right). The HVG cluster numbers (left) and representative genes of clusters 3/4/5/6 (right) are shown. The color coding is as indicated.

- Correlation heatmap of the in vivo and in vitro cell clusters based on the expression of HVGs in (A). Diplotene cells were not found in vitro.

- Numbers of differentially expressed genes [DEGs: log2 (fold change) > 1] between the five comparison groups. M: M1–3; PL: PL1–4; L: L1–2.

- Volcano plots for DEGs in the five comparison groups. Blue: up‐regulated in vivo; orange: up‐regulated in vitro. GO enrichments and representative genes are shown.

We determined the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between in vitro and in vivo cells representing the same developmental stages (Appendix Fig S6G). In accord with the correlation analysis of HVGs, in vitro and in vivo mitotic cells were very similar, showing a small number of DEGs (Fig 5B and C). From the pre‐leptotene stage onward, the number of DEGs increased, with larger numbers of genes up‐regulated in in vitro cells (Fig 5C). From the pre‐leptotene to pachytene stage, genes up‐regulated in in vitro cells were enriched with those involved in developmental processes such as “response to growth factors,” “epithelium development,” “regulation of cell differentiation,” and “transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter,” and included GATA2/3/4, MSX1/2, TBX1/3/5, HAND1/2, NKX2‐5, TFAP2A, ID1/2/3/4, HES1, SMAD7, BAMBI, SPRY4, SHISA2, and DUSP6, among many other relevant genes (Fig 5D, Dataset EV4). On the other hand, genes higher in in vivo cells were enriched with those involved in meiosis such as “DNA repair,” “meiotic cell cycle,” “synapsis,” and “nuclear division,” and included STRA8, REC8, SYCE2, SYCP2, SMC1B, HORMAD1, PRDM9, and SPO11 (Fig 5D, Dataset EV4). Taking these results together, we concluded that cyPGCLCs‐to‐oogonia development in xrOvaries is a robust process that faithfully recapitulates the corresponding in vivo development, and that upon oogonia‐to‐oocytes transition, the in vitro pathway diverges from the in vivo pathway, with mis‐regulation of genes for developmental processes and suboptimal up‐regulation of genes for meiosis, progressing up to the zygotene/pachytene stage and arresting further development of the oocytes.

A comprehensive epigenetic reprogramming during the progression from cyPGCLCs to oogonia to fetal oocyte‐like cells

To explore whether epigenetic reprogramming accompanies the progression of cyPGCLCs to oogonia to fetal oocyte‐like cells, we performed enzymatic methyl sequencing (EM‐seq) analysis (Vaisvila et al, 2021) for genome‐wide DNA methylation (5‐methylcytosine: 5mC) profiles of the relevant in vitro cell types [cyESCs, d8 cyPGCLCs, ag7/21/35 AG+VT− cells, ag35/49 AG+VT+ cells, ag49+52 AG−VT+ cells (with E15.5 mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells), and CEFs], as well as the cell populations enriched with cy oogonia at 8 wpf (oogonia). We also performed whole‐genome sequencing (WGS) of the paternal individual whose spermatozoa were used for the derivation of 15XRi cyESCs and CEFs (Okamoto et al, 2021), and defined single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that discriminate methylation and expression on two parental alleles of the 15XRi‐derived cells and CEFs (Dataset EV10).

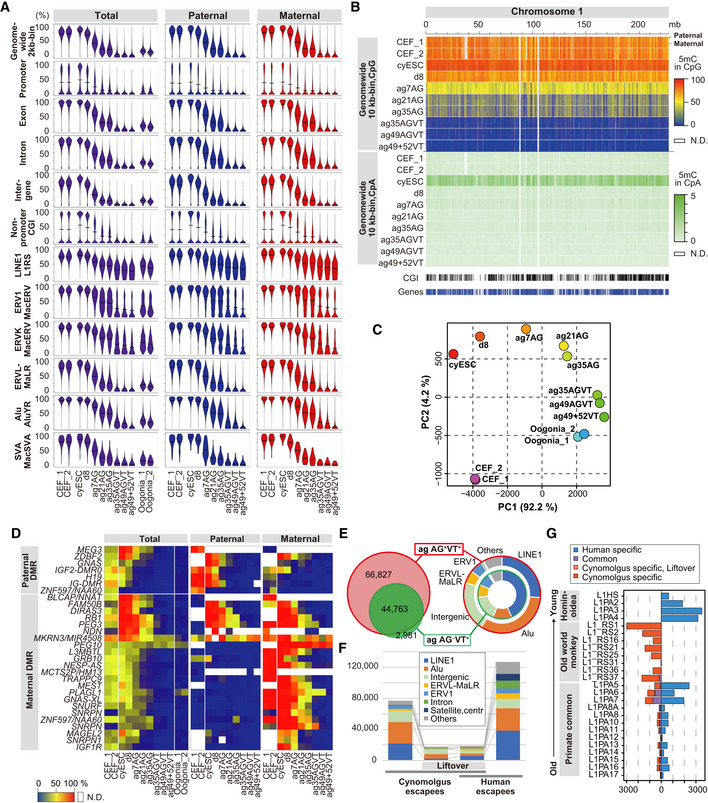

DNA methylation reprogramming on autosomes

cyESCs bore autosome‐wide 5mC levels of ~80%, and these levels showed a progressive and remarkable decrease during the progression from cyPGCLCs to oogonia to fetal oocyte‐like cells, reaching as low as ~6% in ag49+52 AG−VT+ cells (Fig 6A–C, Appendix Fig S7A, Dataset EV12). The autosome‐wide 5mC levels of the cell populations enriched with cy oogonia at 8 wpf were ~20% (Fig 6A, Dataset EV12), in accord with the idea that cyPGCs/oogonia in vivo undergo autosome‐wide DNA demethylation to an extent similar to that in ag35/49 AG+VT+ cells (~5%), while contamination of ovarian somatic cells (~20–40%) elevated the overall DNA methylation levels. DNA demethylation occurred on promoters, exons, introns, intergenic regions, and non‐promoter CpG islands (CGI) in a similar manner on paternal and maternal chromosomes (Fig 6A). Regarding differentially methylated regions (DMRs) of the imprinted genes, unlike CEFs, cyESCs exhibited aberrant methylation on some paternal (MEG3, ZDBF2) and maternal (BLCAP, FAM50B, DIRAS3, RB1, PEG3, NDN, MKRN3) DMRs (Fig 6D, Dataset EV11). Nonetheless, nearly all imprints, including those of aberrantly methylated DMRs (except the aberrantly methylated DMRs of MKRN3 and PEG10) were erased in ag35/49 AG+VT+/ag49+52 AG−VT+ cells (Fig 6D, Dataset EV11).

Figure 6. DNA methylation reprogramming on autosomes during the development of cyESCs to fetal oocyte‐like cells.

- Violin plots of the average 5mC (5‐methylcytosine) levels on the indicated genomic loci on the autosome for the indicated cell types. Data for the paternal and maternal alleles were generated using the reads overlapping with allelic SNPs. AG: AG+VT−; AGVT: AG+VT+; VT: AG−VT+.

- Heatmap of the 5mC [CpG (top) or CpA (bottom)] levels on chromosome 1 in the indicated samples. Data were generated using the reads overlapping with allelic SNPs. mb, megabases. The color coding is as indicated. N.D.: bins without enough CpGs (4) with read depth ≥ 4 in CpG or bins without enough mC + C calls (≥ 10) in CpA.

- PCA of indicated samples using the 5mC levels in the genome‐wide 2‐kb bins. Oogonia: cell populations enriched with cy oogonia at 8 wpf.

- Heatmap of the 5mC levels of the differentially methylated regions (DMRs) of the imprinted genes. Data for the paternal and maternal alleles were generated using the reads overlapping with allelic SNPs. The color coding is as indicated. N.D.: bins without enough CpGs (4) with read depth ≥ 4.

- (left) The relationship of the DNA demethylation escapees in ag35/49 AGVT cells (112,350 loci) and ag49+52 VT cells (49,495 loci). (right) Composition of the escapees in ag35/49 AGVT (outer) and ag49+52 VT cells (inner).

- Comparison and composition of the DNA demethylation escapees in cy and human germ cells. The data for human germ cells are from Tang et al (2015). The color coding is as indicated.

- Comparison and composition of the DNA demethylation escapees on LINE1 in cy and human germ cells.

We defined the “escapees” that showed resistance to autosome‐wide DNA demethylation in ag35/49 AG+VT+/ag49+52 AG−VT+ cells, which consisted predominantly of retrotransposons, including long interspersed nuclear elements 1 (LINE1), Alu sequences, endogenous retrovirus (ERV) 1, ERVK, and ERVL‐MaLR (Fig 6E, Dataset EV15). We compared cy and human escapees (Tang et al, 2015): Around half of cy escapees were lifted over to the human genome, and around half of these lifted‐over escapees were cy specific, with the remaining half being held in common by cynomolgus monkeys and humans (Fig 6F, Dataset EV15), indicating that a majority of the escapees consisted of species‐specific retrotransposons. Accordingly, for LINE1, a majority of the escapees belonged to either macaque‐specific (L1‐RS) or human‐specific (L1HS, L1PA2/3/4) classes of evolutionarily young age, while, for Alu, although the trend was similar, many also belonged to the primate‐common class with cy‐ or human‐specific sequences (Fig 6G, Appendix Fig S7B).

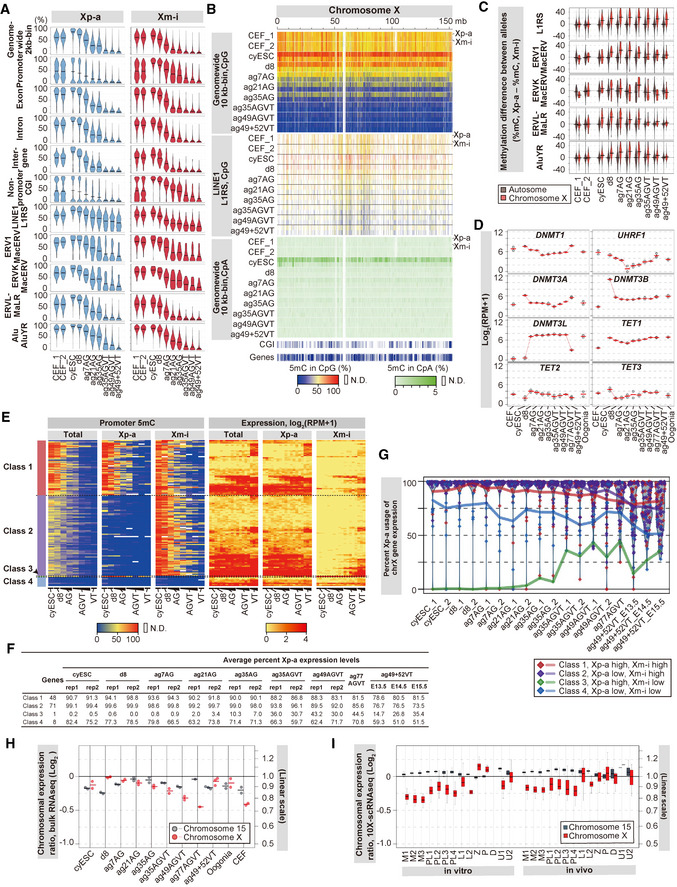

DNA methylation reprogramming on X chromosomes

The 15XRi‐AGVT #7 cyESCs expressed XIST and X‐linked genes from the maternal and paternal allele, respectively (Appendix Fig S7C and D), and at levels similar to those of their parental line and the other female cyESCs (Appendix Fig S1E), indicating that the 15XRi‐AGVT #7 cyESCs bear paternal Xa (Xp‐a) and maternal Xi (Xm‐i). In contrast, CEFs expressed the X‐linked genes from both the paternal and maternal alleles at a ratio of 1:1 (Appendix Fig S7C and D), indicating that they are a polyclonal population for parental X‐chromosome inactivation.

In cyESCs, Xp‐a exhibited a higher chromosome‐wide 5mC level (~85%) than Xm‐i (~70%); Xp‐a showed higher 5mC levels on exons, introns, and intergenic regions (Fig 7A, Dataset EV12). On the other hand, while Xp‐a showed a bimodal methylation profile on promoters/non‐promoter CGIs, Xm‐i exhibited globally methylated promoters/non‐promoter CGIs (Fig 7A). These findings are consistent with a previous report that Xa bears a higher chromosome‐wide 5mC level than Xi in part due to gene body‐specific methylation on Xa (Hellman & Chess, 2007). During the progression from cyPGCLCs to oogonia to fetal oocyte‐like cells, both Xp‐a and Xm‐i showed progressive, chromosome‐wide DNA demethylation, and like autosomes, acquired a highly demethylated state in ag49+52 AG−VT+ cells (Xp‐a: ~7.7%; Xm‐i: ~3.9%; Fig 7A and B, Dataset EV12). We noted that while Xp‐a showed chromosome‐wide demethylation highly similar to autosomes, Xm‐i exhibited unique profiles: Xm‐i showed resistance to demethylation on some promoters/non‐promoter CGIs, which retained > ~50% of 5mCs in ag35/49 AG+VT+/ag49+52 AG−VT+ cells (Figs 6A and 7A). In contrast, Xm‐i demethylated the escapees, particularly LINE1, more efficiently than Xp‐a (Fig 7A and B), and Xp‐a showed ~16% higher 5mC levels on average over 386 LINE1 loci than Xm‐i in ag35/49 AG+VT+/ag49+52 AG−VT+ cells (Fig 7C).

Figure 7. DNA methylation reprogramming on the X chromosomes during the development of cyESCs to fetal oocyte‐like cells.

-

AViolin plots of the average 5mC (5‐methylcytosine) levels on the indicated genomic loci on the X chromosomes for the indicated cell types. Data for the active paternal (Xp‐a) and inactive maternal (Xm‐i) X‐chromosome alleles were generated using the reads overlapping with allelic SNPs. CEF: cy embryonic fibroblasts; AG: AG+VT−; AGVT: AG+VT+; VT: AG−VT+.

-

BHeatmap of the 5mC [CpG (top: genome‐wide 10‐kb bins; middle: LINE1) or CpA (bottom)] levels on the X chromosome in the indicated samples. Data were generated using the reads overlapping with allelic SNPs. mb, megabases. The color coding is as indicated. N.D.: bins without enough mC + C calls (≥ 10) or annotation (L1RS) with mC + C calls ≥ 10.

-

CViolin plots (bar: average) of the differences in the 5mC levels between paternal and maternal alleles on the indicated retrotransposons on the autosomes (black) and the X chromosomes (red) in the indicated samples.

-

DExpression dynamics of genes for DNA methylation/demethylation during the development of cyESCs to fetal oocyte‐like cells. Oogonia: cell populations enriched with cy oogonia at 8 wpf.

-

EHeatmap of the promoter 5mC (left) and expression (right) level dynamics of the genes on the X chromosome during the development of cyESCs to fetal oocyte‐like cells. The Xp‐a and Xm‐i allelic data were generated using the reads overlapping allelic SNPs. The genes were classified according to their promoter 5mC levels on the Xp‐a and Xm‐i alleles in cyESCs: class 1 genes with high (≥ 50%) 5mC on both Xp‐a and Xm‐i (48 genes), class 2 genes with low (< 50%) 5mC on Xp‐a and high 5mC on Xm‐i (71 genes), a class 3 gene with high 5mC on Xp‐a and low 5mC on Xm‐i (XIST), and class 4 genes with low 5mC on both Xp‐a and Xm‐i (8 genes; Dataset EV13). (left) AG: ag7/21/35 AG; AGVT: ag35/49 AGVT; and VT: ag49+52 VT. (right) AG: ag7/21/35 AG_1 and _2; AGVT: ag35/49 AGVT_1 and _2/ag77 AGVT; and VT: ag49+52 VT_E13.5, _E14.5, and _E15.5. The progression of culture dates and the embryonic days of mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells are indicated by progressively broadening underlines. The color coding is as indicated. N.D., promoters with insufficient read depths.

-

FAverage X‐pa usage ratio of X‐linked genes during the development of cyESCs to fetal oocyte‐like cells. The percent Xp‐a expression levels were calculated as . Average X‐pa‐derived SNP usage was calculated for the genes (the gene numbers are shown in the “Genes” column) selected in (E) and plotted in (G).

-

GExpression dynamics from the Xp‐a and Xm‐i alleles during the development of cyESCs to fetal oocyte‐like cells. Proportions of the expression from the Xp‐a allele in the four gene classes in (E) are plotted, with individual values plotted as diamonds and their averages shown as colored lines. The distributions of the Xp‐a ratio of all genes are shown as violin plots. Data points at 100% are dispersed within the range of 5% for better visualization. Raw data are available in Dataset EV13.

-

H, IDynamics of the X chromosome:autosome ratio (X:A ratio) of gene‐expression levels during the development of cyESCs to fetal oocyte‐like cells based on the bulk RNA‐seq (H) or 10X Chromium single‐cell data (I). The ratios of the 75%‐tile expression values of the genes from chromosome X or chromosome 15, relative to those of all genes are plotted in the log2 scale in (H) and as boxplots in the log2 scale in (I). In the boxplots, the central bands represent the median values; the lower/upper hinges represent the 25th/75th percentiles, respectively; the upper limits of the whiskers represent the largest values no further than 1.5 IQR (interquartile range) from the upper hinges; the lower limits of the whiskers represent the smallest values no further than 1.5 IQR from the lower hinges.

Mechanism for DNA methylation reprogramming

To gain insight into the mechanism for DNA methylation reprogramming, we examined the expression of genes associated with DNA methylation/demethylation. Upon cyPGCLC specification, the de novo DNA methyltransferases DNMT3A and especially DNMT3B were acutely down‐regulated, and their expression remained essentially low during the progression from cyPGCLCs to oogonia to fetal oocyte‐like cells (Fig 7D). It was somewhat unexpected that DNMT3L, a co‐factor for DNMT3A/B, was up‐regulated in cyPGCLCs and oogonia‐like cells (Fig 7D). The maintenance DNA methyltransferase DNMT1 was also down‐regulated, but its essential co‐factor UHRF1 was more dramatically repressed in oogonia‐like cells (Fig 7D). TET1/2/3, which oxidizes 5mC to generate 5‐hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) or further oxidized species that can in turn be either passively or enzymatically removed from DNA (Tahiliani et al, 2009; Wu & Zhang, 2014), showed relatively constant expression in the relevant cell types (Fig 7D). Accordingly, the CpA methylation, an index for de novo DNMT activity (Ramsahoye et al, 2000; Liao et al, 2015), was detected at a high level in cyESCs (for X chromosomes, predominantly on Xp‐a), but was very low/absent in cyPGCLC‐derived cells (Figs 6B and 7B, Appendix Fig S7E). These findings suggest that genome‐wide DNA demethylation involves, at least in part, a replication‐coupled, passive mechanism, either directly from 5mC or from 5hmC generated by the TET proteins, in cyPGCLC‐derived cells. Taking these results together, we conclude that the progression from cyPGCLCs to oogonia to fetal oocyte‐like cells entails nearly complete DNA methylation reprogramming, creating an epigenetic framework for oocyte development. This exhaustive reprogramming notwithstanding, unlike parental autosomes, Xa and Xi remain epigenetically asymmetric on some promoters/non‐promoter CGIs and LINE1 elements in oogonia/fetal oocyte‐like cells.

X‐chromosome reactivation and X‐chromosome dosage compensation

It has been shown that during female cyPGCs‐to‐oogonia development, cyPGCs/oogonia reactivate Xi (X‐chromosome reactivation: XCR) and erase hyperactivation of Xa (X‐chromosome up‐regulation: XCU), most likely through epigenetic reprogramming, and subsequently, fetal oocyte development proceeds with two Xa with little, if any, XCU, which represents an X‐chromosome dosage compensation unique to fetal oocytes (Okamoto et al, 2021; Mizuta et al, 2022). Accordingly, we next explored whether X‐chromosome DNA methylation reprogramming in cyPGCLC‐derived cells leads to XCR and an X‐chromosome dosage compensation state unique to fetal oocytes. The 128 X‐linked genes bore informative SNPs and EM‐seq reads and showed appropriate expression levels (Fig 7E, Dataset EV13), and we classified them into four classes based on their promoter 5mC levels in cyESCs: class 1 genes with high 5mC on both Xp‐a and Xm‐i (48 genes), class 2 genes with low 5mC on Xp‐a and high 5mC on Xm‐i (71 genes), a class 3 gene with high 5mC on Xp‐a and low 5mC on Xm‐i (XIST), and class 4 genes with low 5mC on both Xp‐a and Xm‐i (8 genes; Dataset EV13). In cyESCs, the vast majority of class 1/2 genes were expressed exclusively from Xp‐a, while XIST (class 3) was expressed exclusively from Xm‐i and class 4 genes were more biallelic, with ~75% on average being expressed from Xp‐a (Fig 7E−G, Dataset EV13). During the progression from cyPGCLCs to oogonia to fetal oocyte‐like cells, class 1/2 genes on Xm‐i were substantially reactivated, with, on average, ~30% of class 1/2 genes deriving from Xm in ag35/49 AG+VT+/ag49+52 AG−VT+ cells, and, remarkably, XIST (class 3) on Xm‐i was fully reactivated and class 4 genes became fully biallelic (Fig 7E−G, Appendix Fig S7D).

We then examined the X‐chromosome dosage compensation state in cyPGCLC‐derived cells by measuring their X chromosome:autosome ratio (X:A ratio) of gene expression levels. The bulk RNA‐seq data revealed that the X:A ratio increased to ~1.0 during the differentiation of cyESCs to cyPGCLCs, gradually decreased to ~0.8 during oogonia‐like cell differentiation, and then was elevated to ~1.0 in cy fetal oocyte‐like cells (Fig 7H, Dataset EV5). Consistent with these findings, the 10× scRNA‐seq datasets showed that the X:A ratio was ~0.8 in mitotic/pre‐meiotic (pre‐leptotene) cells and increased to ~1.0 in early meiotic (leptotene/zygotene) cells (Fig 7I, Datasets EV6 and EV7). The X:A ratio dynamics in vitro were in accordance with those observed during in vivo development (Fig 7I; Mizuta et al, 2022). Taken together, these findings indicate that XCR progresses substantially, although it is not completed, and X‐chromosome dosage compensation proceeds in a broadly normal manner during the progression from cyPGCLCs to oogonia to fetal oocyte‐like cells.

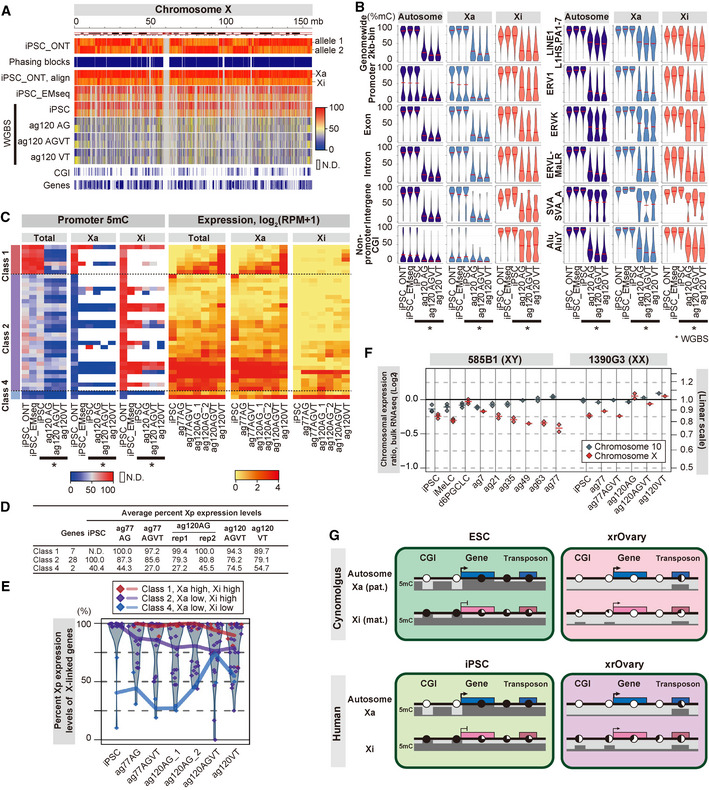

Xi epigenetic property in PSCs can be a determinant of Xi reprogramming in humans and monkeys

It has been reported that human PGCLCs (hPGCLCs) induced from a human iPSC (hiPSC) line (1390G3‐AGVT#526) differentiate into oogonia and then into “RA‐responsive” cell‐like cells (most likely, pre‐leptotene‐stage cells) in xrOvaries (Yamashiro et al, 2018), but their X‐chromosome reprogramming remains to be elucidated. In contrast to the 15XRi AGVT cyESC line bearing Xi with abundant H3K27me3 and little H3K9me3 (Fig 1), the 1390G3 AGVT hiPSC line showed Xi with little H3K27me3 and abundant H3K9me3 (Yokobayashi et al, 2021), and this difference should be informative when comparing the dynamics and extents of X‐chromosome reprogramming and reactivation between oogonia/fetal oocyte‐like cells induced from these two lines. To explore this point, we performed a long‐read sequencing of 1390G3 AGVT #526 using Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT; Jain et al, 2018; Miga et al, 2020) and reconstructed the X‐chromosome allelic sequences based on DNA methylation profiles of the phasing blocks co‐determined by ONT, given that Xa bears a higher 5mC level than Xi (Fig 8A). The 5mC distributions determined by ONT across phased Xa and Xi were consistent with those determined by EM‐seq and by whole‐genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS; Fig 8A; Yamashiro et al, 2018), corroborating the correct phasing of Xa and Xi.

Figure 8. DNA methylation reprogramming on the X chromosomes during human oogonia/RA‐responsive cell‐like cell development.

- Heatmap of the 5mC levels on the X chromosome (chromosome‐wide 10 kb bins) in the indicated samples (*) during human oogonia/RA‐responsive cell‐like cell development from a hiPSC line (1390G3 AGVT #526) reported in Yamashiro et al (2018). Data were generated using the reads overlapping with allelic SNPs. The X‐chromosome allelic sequences were phased based on the 5mC levels of the promoters, non‐promoter CGIs, and genome‐wide 10 kb bins. iPSC_ONT: 5mC levels of the phasing blocks; iPSC_ONT, align: 5mC levels of the phased X chromosome assigned as Xa and Xi; and iPSC_EMseq: 5mC levels of the hiPSCs determined by EM‐seq. mb, megabases. The color coding is as indicated. AG: AG+VT−; AGVT: AG+VT+; VT: AG−VT+.

- Violin plots of the average 5mC levels on the indicated genomic loci on the autosomes and the X chromosomes for the indicated cell types. Data for Xa and Xi were generated using the reads overlapping with allelic SNPs. iPSC_ONT: the methylome data of 1390G3‐AGVT#526 iPSCs analyzed by ONT whole‐genome sequencing; iPSC_EMseq: the methylome data of 1390G3‐AGVT#526 iPSCs analyzed by EM‐seq.

- Heatmap of the promoter 5mC (left) and expression (right) level dynamics of the genes on the X chromosome during the development of hiPSCs to human oogonia/RA‐responsive cell‐like cells. The Xa and Xi allelic data were generated using the reads overlapping allelic SNPs. The genes were classified according to their promoter 5mC levels on the Xa and Xi alleles in hiPSCs: class 1 genes with high (≥ 50%) 5mC on both Xp‐a and Xm‐i (7 genes), class 2 genes with low (< 50%) 5mC on Xp‐a and high 5mC on Xm‐i (28 genes), and class 4 genes with low 5mC on both Xp‐a and Xm‐i (3 genes; Dataset EV14). The color coding is as indicated. N.D.: bins without enough mC + C calls (≥ 10).

- Average Xa usage ratio of X‐linked genes during the development of hiPSCs to human oogonia/RA‐responsive cell‐like cells. The percent Xa expression levels were calculated as . Average Xa‐derived SNP usage was calculated for the genes (the gene numbers are shown in the “Genes” column) selected in (C) and plotted in (E). Note that the X reactivation rates of all informative genes were not significantly different between cy fetal oocyte‐like cells (ag49+52 VT cells with E13.5/14.5/15.5 mouse embryonic ovarian somatic cells) and human RA‐responsive cell‐like cells (ag120 VT cells; P > 0.22).

- Expression dynamics from the Xa and Xi alleles during the development of hiPSCs to human oogonia/RA‐responsive cell‐like cells. Proportions of the expression from the Xa allele in the three gene classes in (C) are plotted, with the individual values plotted as diamonds and their averages shown as colored lines. The distributions of the Xa ratio of all genes are shown as violin plots. Data points at 100% are dispersed within the range of 5% for better visualization. Raw data are available in Dataset EV14.

- X:A ratio of gene expression levels during human oogonia/RA‐responsive cell‐like cell development from hiPSCs based on the bulk RNA‐seq data (Yamashiro et al, 2018). The ratios of the 75%‐tile expression values of the genes from chromosome X or chromosome 10, relative to those of all genes are plotted in the log2 scale.

- A model for DNA methylation reprogramming in cy/hPGCLC‐derived cells in xrOvaries. 5mC levels on the representative genomic loci [CpG islands (CGIs), high CpG promoters, gene bodies, intergenic regions, and transposons] are show in dark (high 5mC) and pale (low 5mC) gray and by pie charts (black: methylated; white: unmethylated). Autosomes and Xa in PSCs show an essentially identical reprogramming profile, while Xi in PSCs exhibits a unique reprogramming profile that is dependent on the Xi epigenetic state in PSCs.

In hiPSCs, Xa (chromosome‐wide 5mC level: ~85%) exhibited a higher 5mC level than Xi (~70%) in exons, introns, and intergenic regions, and bimodal methylation on promoters/non‐promoter CGIs, while Xi exhibited globally methylated promoters/non‐promoter CGIs (Fig 8B, Dataset EV16). During the progression from hPGCLCs to oogonia to RA‐responsive cell‐like cells, Xa showed DNA methylation reprogramming similar to autosomes, whereas Xi exhibited demethylation resistance; irrespective of genomic elements, Xi showed ~40% 5mC levels in oogonia/RA‐responsive cell‐like cells (ag120 AGVT/VT cells; Fig 8B, Dataset EV16), and the demethylation resistance on Xi was similar to that on demethylation escapees consisting of retrotransposons on autosomes (Fig 8B), resulting in substantial epigenetic asymmetry on parental X chromosomes in oogonia/RA‐responsive cell‐like cells. Given the contrasting Xi epigenetic properties between 15XRi AGVT cyESCs and 1390G3 AGVT hiPSCs, that is, high H3K27me3 versus high H3K9me3 (Fig 1; Yokobayashi et al, 2021), these findings suggest the possibility that the Xi epigenetic properties in PSCs are a determinant of Xi reprogramming during in vitro oogenesis.

Despite the resistance of Xi to demethylation, Xi reactivation occurred to a good extent; on average, ~20% of informative genes were expressed from Xi in oogonia/RA‐responsive cell‐like cells (Fig 8C−E, Dataset EV14), and their X:A ratio of gene expression levels was ~1.0, a value expected for human fetal oocyte‐like cells (Chitiashvili et al, 2020; Mizuta et al, 2022; Fig 8F, Dataset EV17). Collectively, these findings led us to propose that in both humans and cynomolgus monkeys, PSC‐derived oogonia/fetal oocyte‐like cells remain epigenetically asymmetric on parental X chromosomes and incompletely, albeit substantially, reactivate Xi, with the reactivation extent depending on the epigenetic properties of Xi in PSCs (Fig 8G). Nevertheless, PSC‐derived oogonia/fetal oocyte‐like cells undergo broadly normal X‐chromosome dosage compensation, likely in part through remaining XCU (Ohno, 1967; Deng et al, 2014; Larsson et al, 2019).

Discussion

Oogenesis consists of three distinct phases: the first phase begins with PGC specification followed by oogonia differentiation with epigenetic reprogramming; the second phase involves oogonia‐to‐oocytes differentiation with the progression of meiotic prophase I to form oocytes at the diplotene stage, which are organized into primordial follicles with ensheathing granulosa cells; and the third phase entails oocyte growth and maturation (i.e., development of primordial follicles to fully grown follicles) with ensuing meiotic resumption. Here, we have demonstrated in vitro oogenesis up to the middle of the second phase using cyESCs as a starting material, thereby creating a foundation for the study of in vitro oogenesis in primates as well as a benchmark for critically evaluating human in vitro oogenesis.

We have shown that all female cyESCs cultured under our condition (see Materials and Methods) maintain one Xa and one Xi with XIST expression over a substantial number of passages (9–21 passages; Fig 1E–G, Appendix Fig S1B–E, Dataset EV9). This is in contrast to hPSCs cultured under a conventional condition, which exhibit a progressive “erosion” of Xi with XIST repression and de‐repression of genes on Xi over a comparable number of passages (4–20 passages; Mekhoubad et al, 2012; Nazor et al, 2012; Vallot et al, 2015; Patel et al, 2017; Sahakyan et al, 2017; Bar et al, 2019; Yokobayashi et al, 2021). Accordingly, Xi in hPSCs shows an unstable and impaired epigenetic state, including chromosome‐wide erasure of H3K27me3 and aberrant deposition of H3K9me3 (Mekhoubad et al, 2012, Nazor et al, 2012, Vallot et al, 2015, Patel et al, 2017, Sahakyan et al, 2017, Bar et al, 2019, Yokobayashi et al, 2021). Although it has been shown that DNA methylation of the XIST promoter on Xi is involved in Xi erosion (Fukuda et al, 2021), the detailed mechanism underlying Xi erosion remains unclear. Notably, however, a recent study has shown that lithium chloride (LiCl), a component of conventional hPSC culture media such as mTeSR1, activates WNT signaling and induces Xi erosion, and the removal of LiCl from the medium prevents hPSCs from Xi erosion (Cloutier et al, 2022). LiCl also induces Xi erosion in mouse epiblast stem cells (EpiSCs; Cloutier et al, 2022). These observations are consistent with the present findings that cyESCs cultured under our condition that includes a WNT inhibitor (IWR1; see Materials and Methods), but not those cultured under a conventional condition (Okamoto et al, 2021), evade Xi erosion, suggesting that the impact of WNT signaling on Xi stability is conserved among humans, monkeys, and mice, and likely other mammalian species. It would be interesting to explore whether hPSCs can be cultured with stable Xi in the presence of a WNT inhibitor. Also, to define the appropriate X‐chromosome epigenetic states for human/primate in vitro oogenesis, it is critical to explore the epigenetic‐state dynamics of Xa and Xi in the pre‐ and the early post‐implantation epiblast in humans/primates, and to evaluate the Xi epigenetic state in PSCs.

Using allele‐specific analyses, we have demonstrated nearly complete DNA methylation reprogramming on autosomes and Xa, and unique reprogramming dynamics on Xi during the progression from cyPGCLCs to oogonia to fetal oocyte‐like cells (Figs 6 and 7). In oogonia/fetal oocyte‐like cells, compared to autosomes/Xa, Xi retained higher 5mC levels on some promoters/non‐promoter CGIs, while Xi bore lower 5mC levels on LINE1, leaving some epigenetic asymmetry between Xa and Xi (Fig 7A–C). In oogonia/fetal oocyte‐like cells, Xi reactivation was incomplete, albeit substantial, with ~30% of X‐linked genes being expressed from Xi (Fig 7E–G, Dataset EV13). On the other hand, the X:A ratio transitions in vitro were highly similar to those during in vivo development, with fetal oocyte‐like cells showing an X:A ratio of ~1.0 (Fig 7H and I), indicating a broadly normal X‐chromosome dosage compensation, although careful gene‐by‐gene analysis would be required for a formal conclusion. We assume that such X‐chromosome dosage compensation is attained at least in part through residual XCU (Ohno, 1967; Deng et al, 2014; Larsson et al, 2019), a possibility that warrants investigation. In good agreement with these findings, it has been shown in both mice and humans that Xi reactivation is incomplete and somewhat heterogeneous in embryonic oocytes that enter the meiotic prophase (Sugimoto & Abe, 2007; Vertesy et al, 2018). Collectively, these findings support the idea that DNA methylation reprogramming during the progression from cyPGCLCs to oogonia to fetal oocyte‐like cells creates an epigenetic state permissive for oocyte development. To formally demonstrate this idea, it is important to define the genome‐wide epigenetic landscape of X chromosomes in an allele‐specific manner in human/cy oogonia/fetal oocytes and to explore whether the epigenetic asymmetries we observed in vitro, for example, those on the promoters/non‐promoter CGIs and LINE1, do exist and when such asymmetry is resolved during oocyte development.

We have shown that Xi in human oogonia/RA‐responsive cell‐like cells induced from a hiPSC line (1390G3 AGVT #526) exhibited a chromosome‐wide demethylation resistance similar to that of autosomal demethylation escapees (Fig 8A and B). This might be due to the highly repressive nature of Xi in 1390G3 hiPSCs, that is, chromosome‐wide H3K9me3 with no/minimal H3K27me3 (Yokobayashi et al, 2021), which is unlike the nature of Xi in cyESCs—that is, in cyESCs, Xi is associated predominantly with H3K27me3 but not with H3K9me3 (Fig 1F and G, Appendix Fig S1C and D)—suggesting that the Xi epigenetic properties in PSCs are a determinant of Xi reprogramming during human/cy in vitro oogenesis. A more systematic study using multiple female human/cyPSC lines is necessary to draw a formal conclusion. In order to further advance human in vitro oogenesis, it will be crucial to establish a culture condition for hPSCs that allows them to maintain an appropriate epigenetic state of Xi. As discussed above, an hPSCs culture with a WNT inhibitor would be one possible means of stabilizing their Xi epigenetic state.

In xrOvaries, cyPGCLCs differentiated robustly into oogonia‐like cells with appropriate transcriptome progression, whereas oogonia‐like cells took a divergent pathway toward oocytes, over‐activating genes for developmental processes with suboptimal up‐regulation of meiosis genes, progressing up to the zygotene/pachytene stage and arresting their further development (Fig 4). Given that oogonia‐like cells acquire an apparently appropriate transcriptome and DNA methylome for oocyte differentiation, including an apparently appropriate up‐regulation of germline reprogramming‐responsive genes (this was also the case for human oogonia/RA‐responsive cell‐like cell development; Appendix Fig S7F and G; Hill et al, 2018), their failure to robustly differentiate into oocytes can be attributed, at least in part, to a defect in extrinsic conditions, that is, the signaling/environment in xrOvaries. In particular, we noted that in vitro fetal oocyte‐like cells over‐activated genes downstream of BMP (GATA2/3/4, MSX1/2, TBX1/3/5, HAND1/2, NKX2‐5, TFAP2A, ID1/2/3/4, SMAD7, BAMBI) and FGF (SPRY4, DUSP6) signaling (Fig 5D, Dataset EV4). Attenuation of such over‐activated signaling pathways at an appropriate timing may lead to more proper oogonia‐to‐oocyte differentiation in xrOvaries.

It is also of note that U1 cells expressed genes characterizing “oogenic” cells (SOHLH1, ZAR1, NPM2) as well as those for male germ cell development (NANOS2, PIWIL4, EGR4; Appendix Fig S6F). These findings suggest that cues from xrOvaries might be sufficient to induce the oogonia‐to‐oocytes transition, but unlike syngeneic cues, they also over‐activate developmental programs on the reprogrammed “naive” epigenome of oogonia‐like cells, and the latter blocks a proper progression of the former, preventing the progress of the meiotic prophase beyond the zygotene/pachytene stage. On the other hand, human/cy oogonia enter and complete the meiotic prophase to form primordial follicles during an in vitro culture of human/cy fetal ovarian reaggregates (human/cy rOvaries); nonetheless, notably, many oogonia are arrested also at the pre‐leptotene stage likely due to suboptimal up‐regulation of key genes for the pre‐leptotene‐to‐leptotene transition, indicating that the pre‐leptotene‐to‐leptotene transition may be a vulnerable, rate‐limiting step for human/cy fetal oocyte development (Mizuta et al, 2022). Accordingly, to achieve a robust in vitro reconstitution of the first and second phases of oogenesis using PSCs as starting materials, it will be important to establish a culture of oogonia‐like cells in syngeneic rOvaries under a condition that allows an efficient oogonia‐to‐oocytes transition. It will also be vital to understand the signaling and transcriptional mechanism involved in the human/cy oogonia‐to‐oocytes transition, which appears to be divergent from that in mice (Mizuta et al, 2022). Such endeavors will be decisive for a step‐by‐step realization of in vitro oogenesis in humans and relevant primate species.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Experimental procedures using cynomolgus monkeys were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Shiga University of Medical Science. The procedures for oocyte collection, intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), and pre‐implantation embryo culture in cynomolgus monkeys were performed as described previously (Yamasaki et al, 2011). All ICR mice used in this study were purchased from the Shimizu Laboratory (Kyoto, Japan).

cyESC derivation from cynomolgus monkey embryos and cyESC culture

The female cyESC lines, 3‐, 15‐, 18‐, 19‐, and 22XRi, were established as described previously (Sakai et al, 2019). Briefly, inner cell masses (ICMs) of day 8 cy blastocysts were cultured on mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). The ICMs were cultured until primary colonies were obtained in the culture medium [Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM)/F12 (Thermo Fisher, 10565018), 20% (v/v) Knockout Serum Replacement (KSR; Thermo Fisher, 10828028), non‐essential amino acids (NEAAs; Thermo Fisher, 1140050), penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher, 15140122), sodium pyruvate (Sigma Aldrich, S8636), L‐glutamine (Sigma Aldrich, G7513), 10 ng/ml basic FGF (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, 6805384), and 10 μM XAV939 (Calbiochem, 575545)]. The obtained colonies were passaged several times onto the fresh MEFs, and were dissociated with TrypLE Select (Thermo Fisher, 12563029) for further expansion. Cynomolgus ESCs were cultured on MEFs (5.0 × 105 cells per well on a six‐well plate) at a seeding density of 2.5 × 103 cells. The culture medium, AITS+IF20 (Sakai et al, 2019), consists of 50% Advanced RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher, 12633012), 50% Neurobasal (Thermo Fisher, 12348017), 1.6% (w/v) Albumax (Thermo Fisher, 11020062), 1 × ITS (Thermo Fisher, 41400045), 1 × NEAA, 2 mM L‐glutamine (Thermo Fisher, 25030081), 25 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin, 20 ng/ml bFGF (Wako, 060‐04543), and 2.5 μM IWR1 (Sigma Aldrich, IO161). The cells were passaged onto the fresh MEFs at around day 7–8 by dissociation with CTK solution [0.25% Trypsin (Sigma‐Aldrich, T4799‐5), 0.1% type IV collagenase (MP Biomedicals, 195110), 0.1 M CaCl2 (Sigma‐Aldrich, C3306), and 20% KSR (GIBCO, 10828‐028) in PBS] and TrypLE select.

Culture of cy embryonic fibroblasts (CEFs)

Cy embryonic fibroblasts were prepared as described previously (Okamoto et al, 2021). They were maintained in DMEM (Thermo Fisher, 10313‐021) and supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1× GlutaMAX™ Supplement (Thermo Fisher, 35050061). At a fully confluent state, the cells were passaged by treating with 0.25% Trypsin/EDTA (Thermo Fisher, 25200072) at 37°C for 3 min.

Generation of the 15XRi AGVT reporter cyESC lines

The donor vector for the TFAP2C‐p2A‐EGFP knock‐in cell lines was constructed as described previously (Sakai et al, 2019). To generate VASA‐p2A‐tdTomato knock‐in cyESC lines, homology arms extending 1.2 kb and 1.3 kb from the stop codon of cy DDX4 were amplified by PCR using the 3XRi genomic DNA as a template with KOD plus Neo DNA polymerase (TOYOBO, KOD‐401). The primer pairs were listed in Dataset EV18. The amplified homology arms were sub‐cloned into pCR™2.1 TOPO vector (Thermo Fisher, K4500‐40) and sequencing analysis was performed by Sanger sequencing. The donor vector with homology arms was amplified by inverse PCR to exclude the stop codon using KOD Plus Neo DNA polymerase. p2A‐tdTomato fragments with pgk‐Neo flanked by LoxP sequences were amplified by PCR using the donor vector used for BLIMP1‐p2A‐tdTomato (Sakai et al, 2019) and inserted in frame prior to the stop codon using an In‐Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Takara Bio, 639633).

A pair of the guide RNAs for the homologous recombination of the target vectors into the DDX4 locus using the CRISPR/Cas9 system were designed within 100 bp upstream and downstream of the stop codon by using the CRISPR direct website (https://crispr.dbcls.jp/). The 5′ ends of the designed oligo DNAs with compatible ends with the BbsI site were phosphorylated by T4 kinase (Takara Bio, 2021S) at 37°C, and then denatured at 95°C and annealed by gradually decreasing the incubation temperature down to 35°C. The annealed oligos were inserted into the BbsI site of the pX335‐U6‐Chimeric BB‐CBh‐hSpCas9n (D10A) vector (Addgene plasmid, 42335). The recombination activities of the designed guide RNAs were examined by single‐strand annealing (SSA) assay (Sakuma et al, 2013).

The introduction of both TFAP2C‐p2A‐EGFP and DDX4‐p2A‐tdTomato targeting vectors into the 15XRi cyESC line was performed as reported previously (Sakai et al, 2019). Briefly, 5.5 × 105 of 15XRi cyESCs (at p4) were mixed with 1 μg of the TFAP2C‐p2A‐EGFP donor vector and 1 μg of guide RNAs/Cas9 expression vectors for the TFAP2C locus in 100 μl of Opti‐MEM (Thermo Fisher, 31985062) using the NEPA21 type II (Nepagene) at 130 V for 3.5 ms. The electroporated cells were seeded onto 5.0 × 105 cells of puromycin/neomycin/hygromycin‐resistant (3r‐) MEFs in a 6 cm dish and cultured for 2 days. The cells were then cultured in the presence of 1 μg/ml puromycin (Thermo Fisher, A1113803) for 8 days. 5.5 × 105 of the surviving 15XRi cyESCs were transfected with 1 μg of the DDX4‐p2A‐tdTomato vector and 1 μg of guide RNAs/Cas9 expression vectors for the DDX4 locus in 100 μl of Opti‐MEM. After electroporation with NEPA21 type II at 130 V for 3.5 ms, the cells were cultured on the 3r‐MEFs for 2 days. The transfected cells were selected by antibiotic selection with 200 μg/ml G418 (Gibco, 10131035) for 7 days. Finally, 5.5 × 105 of the surviving 15XRi cyESCs were suspended in 100 μl Opti‐MEM containing 5 μg of the expression vector of Cre recombinase and plated onto wild‐type MEFs. One hundred colonies were picked up for expansion and genotyping by PCR.

For the genotyping, the genomic DNA was extracted by using a GenElute Mammalian Genome Purification Kit (Sigma, G1N350), and the successful insertion of the gene cassette and the absence of random integration of the vector sequence were confirmed by PCR using the primer pairs listed in Dataset EV18 and KOD one DNA polymerase (TOYOBO, KMM‐101). To verify the targeted/non‐targeted alleles, the sequences around the stop codon were amplified by PCR using the primer pairs listed in Dataset EV18 and KOD one DNA polymerase, and sequenced by Sanger sequence.

Karyotyping

cyESCs at 6 days after the passage in AITS+IF20 were treated with 80 ng/ml KaryoMAX Colcemid (Thermo Fisher, 15210040) at 37°C for 3 h, and then dissociated by CTK solution and TrypLE select. The cells were incubated in 2 ml of Buffered Hypotonic Solution (Genial Helix, GGS‐JL‐006b) and fixed with Carnoy's Solution (75% methanol and 25% acetic acid) on ice. Then, the fixed cells were washed twice and resuspended in 5 ml of Carnoy's solution. After spreading onto a glass slide, the chromosomes were stained with 0.1 μg/ml DAPI (Dojindo, D523) and mounted in VECTASHIELD mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, H‐1000). Chromosome spreads were observed with an FV‐1000D confocal microscope (Olympus) and the number of chromosomes was counted manually.

cyPGCLC induction