Abstract

To identify Mycobacterium leprae-specific human T-cell epitopes, which could be used to distinguish exposure to M. leprae from exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis or to environmental mycobacteria or from immune responses following Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination, 15-mer synthetic peptides were synthesized based on data from the M. leprae genome, each peptide containing three or more predicted HLA-DR binding motifs. Eighty-one peptides from 33 genes were tested for their ability to induce T-cell responses, using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from tuberculoid leprosy patients (n = 59) and healthy leprosy contacts (n = 53) from Brazil, Ethiopia, Nepal, and Pakistan and 20 United Kingdom blood bank donors. Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) secretion proved more sensitive for detection of PBMC responses to peptides than did lymphocyte proliferation. Many of the peptides giving the strongest responses in leprosy donors compared to subjects from the United Kingdom, where leprosy is not endemic, have identical, or almost identical, sequences in M. leprae and M. tuberculosis and would not be suitable as diagnostic tools. Most of the peptides recognized by United Kingdom donors showed promiscuous recognition by subjects expressing differing HLA-DR types. The majority of the novel T-cell epitopes identified came from proteins not previously recognized as immune targets, many of which are cytosolic enzymes. Fifteen of the tested peptides had ≥5 of 15 amino acid mismatches between the equivalent M. leprae and M. tuberculosis sequences; of these, eight gave specificities of ≥90% (percentage of United Kingdom donors who were nonresponders for IFN-γ secretion), with sensitivities (percentage of responders) ranging from 19 to 47% for tuberculoid leprosy patients and 21 to 64% for healthy leprosy contacts. A pool of such peptides, formulated as a skin test reagent, could be used to monitor exposure to leprosy or as an aid to early diagnosis.

The completion of the sequencing of the genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (7) and the availability of almost 98% of the genome sequence of Mycobacterium leprae (http://www.sanger.ac.uk) provide a unique opportunity to identify specific antigens within these pathogens, which could be used as diagnostic tools. One approach, which has been used previously to develop M. tuberculosis-specific diagnostic antigens, is to identify genes present in M. tuberculosis which have been deleted from Mycobacterium bovis BCG (20), in order to distinguish M. tuberculosis infection from BCG vaccination. For example, genes within the RD1 region of M. tuberculosis, such as ESAT-6, encode antigens recognized by T cells from mice infected with M. tuberculosis and patients with tuberculosis (17, 27) but not by T cells from mice infected with M. bovis BCG or in human BCG vaccinees.

Previous studies of the human T-cell response in leprosy patients have identified a number of antigens that induce T-cell responses, measured by lymphocyte proliferation or gamma interferon (IFN-γ) secretion, in patients with tuberculoid leprosy. Such antigens include the M. leprae 70-kDa, 65-kDa, 45-kDa, 35-kDa, 18-kDa, and 10-kDa antigens (1, 2, 6, 12, 16, 29, 31). The members of the heat shock family of proteins are highly conserved, and homologues of the M. leprae 70-kDa, 65-kDa, and 10-kDa antigens show over 90% homology between M. leprae and M. tuberculosis. It is therefore not possible to use such antigens as diagnostic reagents. Other antigens were initially thought to be M. leprae specific, such as the M. leprae 35-kDa antigen, which has been shown to have homologues in Mycobacterium intracellulare and Mycobacterium avium and to contain both specific and conserved T-cell epitopes (31). Despite such extensive cross-reactivity within the whole proteins, particular regions can show sequence divergence, and specific T-cell epitopes have been identified, for example, in the M. leprae 10-kDa antigen (6). The present study therefore set out to identify such peptides, capable of inducing an M. leprae-specific T-cell response in leprosy patients who were infected with M. leprae; a pool of such peptides could then be used to monitor exposure to M. leprae within communities.

The 4.4-Mb genome of M. leprae contains sufficient information to encode approximately 1,500 genes, and thus the antigens studied in recombinant form to date represent a very small fraction of the potential antigens expressed by M. leprae (8). Previous studies using M. leprae antigens fractionated on nitrocellulose indicated that many additional proteins might be recognized as antigens (4). It is also likely that within fractionated M. leprae preparations such as the M. leprae cell wall antigenic fraction and the M. leprae cytosolic antigen fraction, which induce strong T-cell responses in peripheral blood cells from tuberculoid leprosy patients (21, 30), there are many as yet unidentified antigens. The objective of the current study was to utilize available genomic information from M. leprae to identify some of these additional, as yet unidentified antigens and, in particular, those which might be specific for M. leprae. In order to increase the likelihood of identifying such specific T-cell epitopes, peptides were selected by screening for HLA-DR binding motifs identified using the FINDPATTERNS program and sequence dissimilarity from the M. tuberculosis genome sequence sought using FASTA. The identified peptides were then tested for their recognition by T cells from leprosy patients and their contacts in four countries where leprosy is endemic, in order to identify M. leprae-specific peptides which may be suitable for development as a skin test.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Leprosy patients, contacts, and controls from areas where leprosy is not endemic.

Polar-borderline tuberculoid leprosy patients (true tuberculoid-borderline tuberculoid [TT/BT]) (n = 59) were selected as individuals known to be infected with M. leprae and likely to make good T-cell responses to leprosy antigens. Patients were diagnosed according to clinical symptoms and bacterial index of skin slit smear samples. Some of the patients tested in each center were untreated; the remainder had received up to 6 months of multidrug therapy. Lepromin skin test results were not available for the patients tested here. None of the patients were in type 1 (reversal) reaction at the time of testing. Staff from leprosy hospitals (n = 53), free of signs of clinical leprosy, who had remained healthy despite working with infectious leprosy cases were recruited in the four countries of leprosy endemicity, as subjects known to be exposed to infectious cases of leprosy. Leprosy patients and contacts were recruited in Pakistan, Nepal, Ethiopia, and Brazil to provide a variety of ethnic groups and HLA types. All subjects gave their informed consent prior to venipuncture. In the United Kingdom, where leprosy is not endemic, 20 anonymous blood bank donations supplied as buffy coat packs were used. Approval for this study was granted by the appropriate local ethics committees.

Peptide selection and synthesis.

One hundred ninety-three peptides were selected for synthesis. Of these, 55 came from M. leprae antigens with known homologues in M. tuberculosis. An additional 138 peptide sequences were selected from predicted open reading frames within the M. leprae genome sequence. All the peptides contained 3 or more of 10 known HLA-DR binding motifs [DR 1, 2a, 4(4), 4(10), 4(14), 4(15), 5, 7, 8, and 17] (24), identified using FINDPATTERNS and appropriate search patterns for each motif, and ≥5 of 15 amino acid mismatches with all other open reading frames in the GenBank-EMBL databases (using GCG-TFASTA). This T-cell epitope selection was confirmed using the EpiMer algorithm (22). The 81 peptides tested here were derived from 33 M. leprae genes, 20 of which were derived from genes with known homologues in M. tuberculosis: Rv215c (ATPase), Rv1309 (ATPase), Rv3423c (alanine racemase), Rv1886c (antigen 85B), Rv0129 (antigen 85C), Rv1568 (BioA), Rv1569 (BioF), Rv2589 (GabT), Rv1300 (HemF), Rv2587c (SecD), Rv3021c (serine-rich PPE family [7]), Rv0655 (ATP binding cassette transporter), Rv1300 (HemK), Rv1302 (Rfe), Rv1297 (Rho), Rv0750 (unidentified reading frame [URF]), Rv2727v (RecA), Rv0003 (RecF), Rv3648c (cold shock protein), and Rv2586c (SecF). The remainder were derived from URFs. None of the peptides were derived from the RD1 region of M. tuberculosis, which is deleted from M. bovis BCG (20). As the full M. leprae genome sequence was not available at the time that the study was performed, the peptides were given identifiers based on their order of synthesis and original pools.

At the time of synthesis, using the gene sequence data available at that time, all 193 peptides had five or more amino acid differences from the equivalent M. tuberculosis sequence, and ≥5 of 15 amino acid mismatches with any other known protein. With the subsequent completion of the M. tuberculosis genome sequencing project and the correction of sequencing errors in the M. leprae and M. tuberculosis genomes, only 15 of the 81 peptides tested here still showed ≥5 of 15 amino acid mismatches with the equivalent M. tuberculosis sequence. This allowed a comparison of the sensitivities and specificities of peptides with identical, or nearly identical, sequences in M. leprae and M. tuberculosis with those that had ≥5 of 15 amino acid mismatches.

Synthetic peptides, 15 amino acids long, were synthesized using solid-phase tert-butoxycarbonyl methods. The identity and purity of the peptides were confirmed by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. A selection of the peptides, as listed in Table 3, were screened for endotoxin contamination; endotoxin contamination was <0.1 endotoxin unit per ml, giving a final concentration in the assays of <0.01 endotoxin unit per ml. The peptides were initially screened as pools of 10 or 11 peptides, and the peptides within 8 of the 19 pools (n = 81), which had given strong T-cell responses in leprosy patients in one or more centers, were selected for further testing as individual peptides. Due to restrictions on the volume of blood available, it was possible to test individual leprosy patients and contacts with a maximum of only 41 peptides at one time. Each leprosy center therefore tested the component peptides from only four of eight pools, which had given good lymphocyte transformation test (LTT) and IFN-γ responses in the first round of testing with the peptide pools. As the use of buffy coat blood packs in the United Kingdom provided an excess of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), United Kingdom blood donors were tested with all 81 peptides. Peptides were dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline or phosphate-buffered saline containing 5% dimethyl sulfoxide and added to the cultures at 20 μl/well, giving a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. The presence of 0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide in cultures did not inhibit T-cell responses to antigen or mitogen (results not shown).

TABLE 3.

Correlation between presence of predicted HLA-DR binding motifs and HLA-DR alleles expressed by responder and nonresponder United Kingdom control subjectsa

| Peptide, alleles, and responder status | No. of subjects

|

|

|---|---|---|

| With alleles | Without alleles | |

| D8963 (DR 1, 4, 7) | ||

| Responder | 3 | 2 |

| Nonresponder | 8 | 7 |

| P8965 (DR 1, 4, 8) | ||

| Responder | 2 | 1 |

| Nonresponder | 6 | 11 |

| S9047 (DR 1, 4, 7) | ||

| Responder | 6 | 5 |

| Nonresponder | 5 | 4 |

| S9062 (DR 1, 4, 7, 15) | ||

| Responder | 4 | 1 |

| Nonresponder | 10 | 6 |

United Kingdom subjects were tested for their ability to secrete IFN-γ in response to individual peptides as described in Materials and Methods. Responders were defined as making ≥50 pg of IFN-γ per ml. HLA typing was performed by PCR. Subjects were divided into those expressing the HLA-DR alleles for which the peptide contained predicted binding motifs or lacking the correct alleles.

Antigens.

M. leprae sonicate (batch no. CD212) was obtained from R. Rees, National Institute for Medical Research, Mill Hill, London, United Kingdom, and was used at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. Tuberculin purified protein derivative (batch no. RT49) was supplied by Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark, and was used at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. Phytohemagglutinin (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom) was used as a positive control at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml.

Lymphocyte proliferation assays.

PBMC were isolated from blood by centrifugation on a Ficoll-Histopaque gradient (Sigma). PBMC were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO BRL, Paisley, United Kingdom) supplemented with 10% autologous plasma, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 2 mM l-glutamine. PBMC (2 × 105) were cultured in 96-well round-bottomed plates, together with 20 μl of antigen or peptide in a total volume of 200 μl in each well. The antigens were diluted in RPMI 1640 containing penicillin-streptomycin and l-glutamine and used at the concentrations described above, and a negative control consisted of PBMC in medium alone. Tests were carried out in triplicate, and the assay mixtures were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator for 5 days. Aliquots of 120 μl of cell-free supernatants were removed and stored at −20°C until tested for cytokine IFN-γ by capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using PharMingen antibodies. Fresh growth medium (100 μl) and 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine per well were then added to each culture well, and the cultures were harvested 18 h later. [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured using a liquid scintillation beta counter.

Proliferation responses are given as mean Δ counts per minute of triplicate wells minus the mean counts per minute from triplicate unstimulated wells and as the stimulation index (SI) defined as the mean counts per minute in antigen-stimulated wells divided by the mean counts per minute in unstimulated wells. Positive proliferative responses were defined by at least a twofold increase (SI of ≥2 and Δ counts per minute of >2,000) in stimulated cultures compared to the value in unstimulated cultures containing medium alone. IFN-γ responses were calculated in picograms per milliliter from the mean of duplicate ELISA wells after subtraction of any nonspecific IFN-γ production in nonstimulated cultures. The background levels of IFN-γ produced by unstimulated PBMC in cultures containing autologous plasma were below the detection limit of the ELISA (median, 5.9 pg/ml) in the majority (74.5%) of tuberculoid leprosy patients and in 97 of 132 (73.5%) total subjects tested; direct measurement of IFN-γ in leprosy patient and contact plasma has failed to demonstrate detectable IFN-γ (R. Owen and H. M. Dockrell, unpublished results). A positive IFN-γ response was taken as any IFN-γ response above the detection limit of the IFN-γ ELISA (50 pg/ml). The rationale for setting the cutoff values for positivity in the two assays is described in the Results.

Statistical analysis.

Intergroup comparisons were carried out using the Wilcoxon rank sum test and the Kruskal-Wallis and χ2 tests as indicated.

RESULTS

Data from all the centers were initially evaluated to decide what to select as the most appropriate cutoffs for positivity in the two assays. Responses to individual peptides may be rather weak, and it was necessary to allow for variations between the background responses in unstimulated cultures in the different centers. Mean backgrounds in the five centers varied from 395 to 2,013 cpm, with a range of 251 to 5,524 cpm for Brazil, 160 to 829 cpm for Ethiopia, 572 to 3,288 cpm for Nepal, 263 to 1,263 cpm for Pakistan, and 91 to 3,698 cpm for the United Kingdom. Proliferation measurements show a normal distribution, and unlike with IFN-γ assays that contain detection limits (identified within the standard curve), there are no threshold criteria that can be used to define a clear responder or nonresponder. So instead of assignment of an arbitrary cutoff value, the threshold for positive responses in each assay was calculated from background measurements from unstimulated cultures (counts per minute of triplicate cultures) from each subject in each center. Analyzing the IFN-γ data from the five centers showed that for most subjects no IFN-γ was detected in the unstimulated cultures (below the ELISA detection limit of 50 pg/ml). IFN-γ levels of ≥50 pg/ml were therefore used to define positive responses. The cutoff thresholds for positivity were therefore defined as a Δ counts per minute of 2,000 and an SI of ≥2 for the proliferation assays and ≥50 pg of IFN-γ/ml.

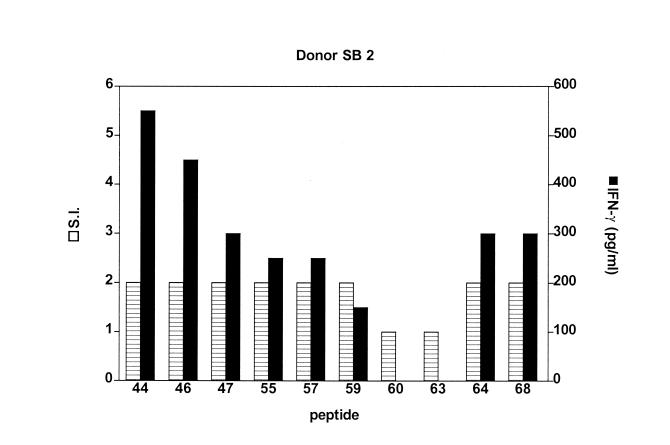

Using these cutoffs, it was found that a greater proportion of subjects were responders to individual peptides in the IFN-γ assay than by use of lymphocyte proliferation measurements. The higher IFN-γ responses were not due to the presence of IFN-γ in the autologous plasma used in the culture medium for each subject; no IFN-γ could be detected in unstimulated cultures of 73.5% of the subjects, irrespective of their diagnosis, and where detectable IFN-γ was present, this was subtracted from the values measured in cultures containing peptide. Figure 1 shows the response of a single United Kingdom donor to 10 peptides in the two assays. Minimal proliferation (SI = 2) was seen in PBMC cultures which produced significant amounts of IFN-γ. This is also illustrated in Fig. 2 for 10 peptides derived from one of the original pools and was observed in data from all the centers and to all the peptides tested. Data from the IFN-γ assays were therefore used as the defining factor for determining responses to the peptides.

FIG. 1.

Lymphocyte proliferation and IFN-γ responses to leprosy peptides in a United Kingdom control subject. PBMC were stimulated with peptides from pool D. The graph shows that both lymphoproliferation (SI) and IFN-γ responses are detected for 8 of 10 peptides. It also shows that with minimal proliferation of PBMC (SI of ≥2) significant amounts of IFN-γ are detected in the more sensitive IFN-γ assay.

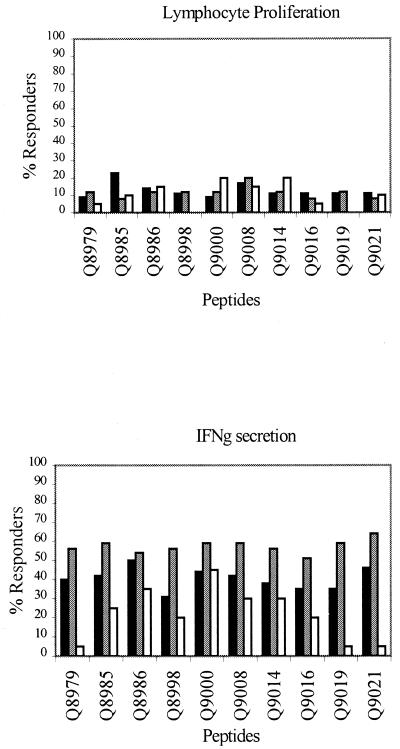

FIG. 2.

Lymphocyte proliferation and IFN-γ production in response to M. leprae peptides. PBMC were stimulated with peptides as described in Materials and Methods, and lymphocyte proliferation and IFN-γ production were measured. TT/BT (solid bars), tuberculoid leprosy patients (n = 35 for LTT and 45 for IFN-γ); contacts (shaded bars), healthy staff leprosy contacts (n = 25 for LTT and 39 for IFN-γ); UK (open bars), United Kingdom nonexposed blood bank controls (n = 20 for both LTT and IFN-γ).

Response to antigens.

Fifty-nine TT/BT leprosy patients and 53 healthy staff leprosy contacts were tested with M. leprae sonicate, phytohemagglutinin or concanavalin A, and peptides using a standardized protocol. The IFN-γ group median responses of TT/BT patients, contacts, and United Kingdom controls to M. leprae sonicate, which is known to contain many conserved antigens with sequence similarity to those from other mycobacteria, were 1,183 (range, 0 to 14,843), 1,696 (range, 0 to 17,325), and 1,525 (range, 0 to 13,500) pg/ml, respectively. The median SIs to M. leprae sonicate for TT/BT leprosy patients, leprosy contacts, and United Kingdom controls were 6 (range, 0 to 31), 7 (range, 1 to 57), and 5 (range, 1 to 19).

Recognition of peptides by patient and control groups.

PBMC from tuberculoid leprosy patients, healthy leprosy contacts, and the United Kingdom controls were tested with the individual peptides, and the results of proliferation and cytokine assays were converted to percent responders. Responses to 10 of the peptides are illustrated in Fig. 2. Some peptides, such as Q8979, Q9019, and Q9021, showed much stronger responses in the leprosy-infected and -exposed groups than in the United Kingdom controls. Other peptides, such as Q8986 and Q9000, induced strong responses in all three groups. The lymphoproliferative and IFN-γ responses to the peptides in the M. leprae-exposed subjects (patients and contacts) and United Kingdom nonexposed donors were then grouped depending on the type of responses made, as shown in Table 1. For this analysis, the results from both tuberculoid leprosy patients and leprosy contacts were pooled, as the exposed leprosy contacts had T-cell recognition of the leprosy peptides equivalent to, or often greater than, that of the M. leprae-infected leprosy patients.

TABLE 1.

Percent responders to M. leprae peptides measured by lymphocyte proliferation and IFN-γ secretiona

| Peptideb | % Respondersc in assay of subject type

|

Putative functiond | No. of amino acid mismatches with equivalent M. tuberculosis sequence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTT

|

IFN-γ

|

|||||

| Leprosy exposed or infected | Nonexposed and noninfected (United Kingdom) | Leprosy exposed or infected | Nonexposed and noninfected (United Kingdom) | |||

| Group 1 | ||||||

| E8977 | 2 | 0 | 29 | 0 | DNA polymerase III | 2/15 |

| P8972 | 6 | 0 | 49 | 0 | ATP synthase gamma chain | 2/15 |

| Group 2 | ||||||

| R9022 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 10 | RecA | 10/15 |

| Q9021 | 10 | 10 | 56 | 5 | URF | 9/15 |

| E8980 | 7 | 0 | 20 | 10 | ABAT | 9/15 |

| S9048 | 16 | 5 | 39 | 5 | Serine-rich antigen | 8/15 |

| P8975 | 0 | 5 | 46 | 0 | AOS | 7/15 |

| E8990 | 9 | 0 | 27 | 10 | AOS | 5/15 |

| K8988 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 10 | AOAT | 4/15 |

| E8978 | 2 | 0 | 27 | 5 | DNA polymerase III | 4/15 |

| E8983 | 9 | 0 | 29 | 10 | HemK protein homologue | 3/15 |

| I9073 | 16 | 0 | 42 | 5 | ATP-dependent Clp protease | 1/17 |

| I9065 | 22 | 0 | 33 | 10 | Aspartyl-tRNA synthetase | 1/15 |

| K8982 | 5 | 0 | 27 | 5 | Aminoglucosamine-F-P-transferase | 1/15 |

| E8973 | 22 | 5 | 24 | 0 | AOAT | 1/15 |

| S9061 | 19 | 0 | 39 | 5 | SecF | 1/15 |

| D8946 | 10 | 0 | 40 | 10 | Putative ATPase | 0/16 |

| Q9019 | 12 | 0 | 48 | 5 | Rho | 0/15 |

| D8959 | 20 | 0 | 47 | 10 | Putative ATPase | 0/15 |

| E8987 | 4 | 0 | 24 | 5 | ATP binding protein | 0/15 |

| E8976 | 11 | 0 | 22 | 10 | DNA polymerase III | 0/15 |

| R9024 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 5 | RecA | 0/15 |

| Group 3 | ||||||

| I9063 | 18 | 5 | 40 | 15 | Serine-rich antigen | 11/15 |

| I9070 | 10 | 20 | 46 | 10 | Hypothetical 15-kDa protein | 11/15 |

| Q9008 | 18 | 15 | 49 | 30 | ATP binding protein | 10/15 |

| K8948 | 5 | 5 | 25 | 55 | URF | 8/15 |

| S9047 | 19 | 15 | 43 | 55 | Serine-rich antigen | 7/15 |

| D8957 | 5 | 20 | 39 | 10 | Putative ATPase | 6/15 |

| D8963 | 12 | 20 | 37 | 30 | Alanine racemase | 5/15 |

| K8941 | 3 | 5 | 25 | 15 | 70-kDa antigen | 5/15 |

| S9062 | 16 | 5 | 36 | 25 | Serine-rich antigen | 5/15 |

| P8965 | 6 | 10 | 46 | 15 | ATPase synthase alpha chain | 4/15 |

| P8956 | 12 | 15 | 54 | 15 | ATP synthase gamma chain | 4/15 |

| E8992 | 4 | 10 | 31 | 25 | DNA polymerase III | 4/15 |

| S9058 | 23 | 10 | 40 | 30 | SecD | 3/15 |

| P8967 | 18 | 25 | 51 | 65 | ATPase synthase alpha chain | 2/15 |

| S9045 | 9 | 15 | 37 | 20 | SecF | 2/15 |

| Q9000 | 10 | 20 | 52 | 45 | ATP binding protein | 1/15 |

| D8944 | 10 | 10 | 49 | 80 | ATPase | 1/15 |

| S9046 | 16 | 10 | 30 | 15 | SecF | 1/15 |

| Q8986 | 12 | 15 | 54 | 35 | ATP binding protein | 0/15 |

| Q8985 | 17 | 10 | 51 | 25 | ATP binding protein | 0/15 |

| S9057 | 19 | 20 | 42 | 35 | SecD | 0/15 |

| K8958 | 6 | 25 | 31 | 65 | ATPase | 0/15 |

Boldface indicates peptides having amino acid mismatches with M. tuberculosis sequences of 5 or more of 15.

Group 1, peptides inducing responses in leprosy-exposed or -infected subjects but not in United Kingdom donors; group 2, peptides inducing stronger responses in leprosy-exposed or -infected subjects than in United Kingdom donors; group 3, peptides inducing good responses in both leprosy-exposed or -infected subjects and United Kingdom donors.

The numbers of leprosy-exposed or -infected subjects tested varied according to the peptide used and are indicated by the peptide prefix as follows: D, 51 and 57; E, 45 and 45; I, 51 and 57; K, 65 and 83; P, 17 and 35; Q, 60 and 84; R, 20 and 38; and S, 43 and 67 for LTT and IFN-γ assays, respectively. Twenty nonexposed and noninfected United Kingdom controls were tested for both the LTT and IFN-γ assays. LTT and IFN-γ were measured following PBMC stimulation with peptide for 5 days. Percent responders were defined as having an SI of ≥2 with a Δ counts per minute of ≥2,000 or ≥50 pg of IFN-γ per ml.

Abbreviations: ABAT, aminobutyrate aminotransferase; AOS, amino-oxononanoate synthase; AOAT, amino-oxononanoate aminotransferase.

Two peptides gave no detectable responses in any of the United Kingdom controls but gave a significant proportion of responders in the IFN-γ assay (group 1). When the sequences of these peptides were analyzed, these peptides were found to have only two amino acid mismatches with those in M. tuberculosis. It is therefore possible that these peptides have not been recognized by the United Kingdom subjects because they have not been exposed to either M. leprae or M. tuberculosis, and further testing would be required to establish if they were M. leprae specific.

A second group of peptides induced greater responses in leprosy-exposed and -infected subjects than in United Kingdom nonexposed donors (group 2). The peptide sequences of this group of peptides vary in their homologies to those found in M. tuberculosis, and peptides E8980, E8990, Q9021, P8975, R9022, and S9048 have a high number of amino acid mismatches with M. tuberculosis sequences (indicated in boldface in Table 1). A small proportion of the United Kingdom controls responded to these peptides.

High lymphoproliferative and IFN-γ responses in both leprosy-exposed subjects and United Kingdom nonexposed donors to a third group of peptides were observed (group 3). The percent responders within the leprosy-infected or -exposed group was similar to those for peptides shown in group 2, but this was matched by equivalent responses in the United Kingdom controls. This group includes peptides such as D8963, I9063, I9070, K8948, Q9008, and S9047, which also have large numbers of amino acid mismatches with the corresponding M. tuberculosis sequences, shown in boldface in Table 1.

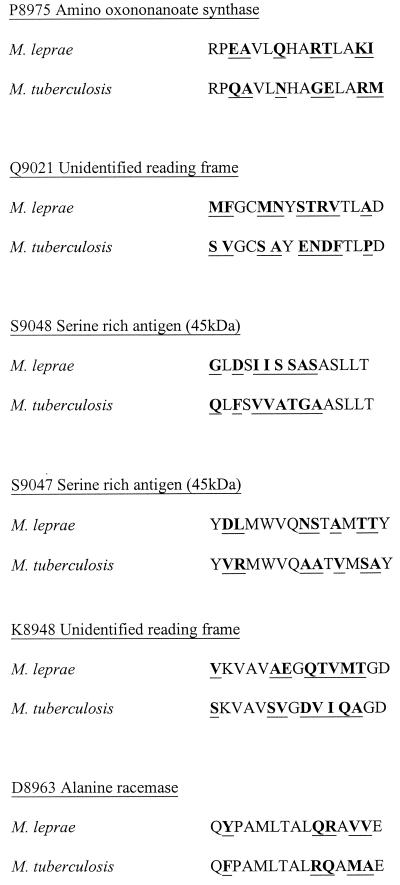

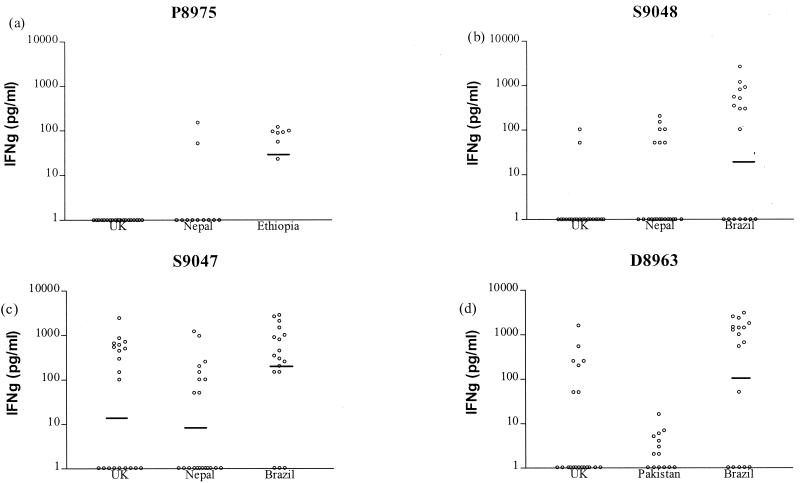

As a higher proportion of positive responses were detected in the IFN-γ assay, which measures cytokine accumulated over the culture period, than in the proliferation assay, in which thymidine incorporation is measured only over a 16-h incubation period, IFN-γ responses were used to assess the specificity of peptide recognition. Table 2 shows the 15 peptides identified as M. leprae specific using the criterion of ≥5 of 15 amino acid mismatches with the IFN-γ responses that they induced in PBMC from TT/BT leprosy patients, leprosy contacts, and United Kingdom nonexposed donors. Due to the uncertainty as to whether leprosy patient contacts have definitely been infected with M. leprae or whether they might develop leprosy at a later date, sensitivity has been calculated separately for the leprosy patient and contact groups. Specificity was defined as the percentage of United Kingdom donors who were nonresponders to the peptides in the IFN-γ assay. Sensitivity was defined as the percentage of TT/BT patients, or leprosy contacts, who made a positive response (≥50 pg of IFN-γ/ml) to the peptides. As can be seen from Table 2, peptides P8975, Q9021, and S9048 showed good specificities of 100, 95, and 90%, respectively. From analyzing the IFN-γ responses of individuals to these peptides, it appears that the recognition of peptides P8975, Q9021, and S9048 by leprosy patients is significantly higher (P < 0.001) than that by United Kingdom unexposed donors. The leprosy contact group often showed greater recognition of these peptides than did the leprosy patients, indicating that they may be useful subjects with which to detect exposure to M. leprae, although this was statistically significant for only peptide S9048 (P = 0.016, χ2 test). However, Table 2 also includes peptides classed as M. leprae specific in terms of having ≥5 of 15 amino acid mismatches, which clearly have lower specificities, such as S9047, K8948, and D8963 (45, 45, and 75%, respectively). The amino acid sequence comparisons of these peptides are shown in Fig. 3 with the corresponding sequences from homologues in M. tuberculosis obtained from the Sanger Centre Database. The peptides with higher specificities have very little homology between the equivalent sequences; the three peptides with lower specificities have five to eight amino acid mismatches, although the distribution of these mismatches varies. The IFN-γ responses of individuals to two representative peptides from each set are also shown in Fig. 4. This illustrates the variation that was observed between centers in the recognition of individual peptides, which may reflect differences in HLA types in the different ethnic groups. An analysis of statistical variance between the responses observed in the different leprosy centers revealed that there were significant differences in the IFN-γ responses to all four peptides (P8975, Nepal versus Ethiopia, P = 0.006; S9048, Nepal versus Brazil, P = 0.023; S9047, Nepal versus Brazil, P = 0.002; D8963, Pakistan versus Brazil, P = 0.011, Kruskal-Wallis test).

TABLE 2.

Performance of potentially M. leprae-specific peptides (≥5 of 15 amino acid mismatches with the equivalent M. tuberculosis sequences) in IFN-γ assay as described in Materials and Methodsa

| Peptide | Specificityb | Sensitivityc

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Contacts | ||

| P8975 | 100 | 39 | 53 |

| Q9021 | 95 | 47 | 64 |

| S9048 | 95 | 26 | 55 |

| I9070 | 90 | 45 | 46 |

| R9022 | 90 | 33 | 29 |

| D8957 | 90 | 32 | 46 |

| E8990 | 90 | 24 | 29 |

| E8980 | 90 | 19 | 21 |

| I9063 | 85 | 42 | 38 |

| K8941 | 85 | 19 | 32 |

| S9062 | 75 | 29 | 45 |

| D8963 | 75 | 32 | 46 |

| Q9008 | 70 | 42 | 59 |

| S9047 | 45 | 37 | 52 |

| K8948 | 45 | 21 | 29 |

The numbers of tuberculoid leprosy patients and leprosy contacts tested varied according to the peptide used and are indicated by the peptide prefix as follows: D, 31 and 26; E, 21 and 24; I, 31 and 26; K, 42 and 41; P, 18 and 17; Q, 45 and 39; R, 21 and 17; and S, 38 and 29, respectively. Twenty United Kingdom controls were tested with each peptide.

Percentage of United Kingdom donors who were nonresponders to the peptides.

Percentage of TT/BT leprosy patients or staff contacts of leprosy patients who made a positive response (≥50 pg of IFN-γ/ml) to the peptides. The responses of the TT/BT leprosy patients and contacts were measured in Nepal, Ethiopia, Brazil, and Pakistan. Differences between the sensitivities obtained for the tuberculoid leprosy patients and the healthy leprosy contacts were not significant with the exception of peptide S9048 (P = 0.0163).

FIG. 3.

Amino acid sequence comparisons between M. leprae and M. tuberculosis. Peptides P8975, Q9021, and S9048 have 7, 9, and 8, respectively, of 15 amino acid mismatches with those from M. tuberculosis and induced strong responses in leprosy patients and minimal responses in United Kingdom subjects. However, peptides S9047, K8948, and D8963, which also have ≥5 of 15 amino acid mismatches with the equivalent M. tuberculosis sequences (7, 8, and 5 of 15, respectively), induced responses in United Kingdom nonexposed donors and are therefore not as specific in terms of the response generated.

FIG. 4.

IFN-γ responses induced by M. leprae peptides with ≥5 of 15 amino acid mismatches with the equivalent M. tuberculosis sequence. PBMC were stimulated for 5 days, and IFN-γ was measured in the culture supernatants by ELISA. Concentrations of ≥50 pg of IFN-γ per ml were used to define a positive response. (a) n = 20 for the United Kingdom, 11 for Nepal, and 7 for Ethiopia. (b) n = 20 for the United Kingdom, 21 for Nepal, and 17 for Brazil. Peptides P8975 and S9048 induced responses in TT/BT leprosy patients but not in most United Kingdom nonexposed donors. (c) n = 20 for the United Kingdom, 21 for Nepal, and 17 for Brazil. (d) n = 20 for the United Kingdom, 14 for Pakistan, and 17 for Brazil. Peptides S9047 and D8968 induced responses in both TT/BT leprosy patients and nonexposed United Kingdom donors. The cutoff value for positive responses was ≥50 pg of IFN-γ per ml. The geometric mean of each group is indicated.

Correlation between HLA type and response to individual peptides.

Information on the major HLA-DR alleles expressed by the United Kingdom subjects, but not the leprosy patients or contacts, was available. We therefore analyzed the correlation between the presence of predicted HLA-DR binding motifs in the peptides and the HLA types expressed by the 20 United Kingdom subjects for the 15 peptides included in Table 2. In some cases, there was a much higher response rate to the peptides in subjects expressing the HLA-DR types to which the peptides were predicted to bind (for example, four of five responders to peptide S9062 had DR 1, 4, 7, or 15). However, other peptides also showed equivalent responses in subjects with or without the correct HLA-DR type (for example, only 6 of 11 responders to S9047 expressed DR 1, 4, or 7). The presence of the correct DR type did not imply that the individual would make a positive IFN-γ response to a particular peptide. Table 3 illustrates these data for two of the peptides illustrated in Fig. 4 (D8963 and S9047) and two additional peptides which also induced good responses in the same United Kingdom control group (P8965 and S9062). Overall, selection using the presence of three or more predicted HLA-DR binding motifs seemed to have resulted in a high proportion of the peptides showing promiscuous binding by a range of different HLA-DR alleles. For example, positive responses to peptide D8963, predicted to bind to DR 1, 4, and 7, were observed for five donors expressing DR 1, 15, and 51; DR 11, 13, and 52; DR 1, 15, and 51; DR 15, 17, and 51; and DR 7, 17, and 52.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of leprosy is declining worldwide, with dramatic decreases in the number of registered patients since shorter courses of multidrug therapy were introduced in the 1980s. However, in countries with the highest incidence, no decrease in the number of new cases detected has occurred (26). This paradox means that, whereas global support and funding for leprosy control are declining, as leprosy is thought to be on the verge of elimination, a real challenge still faces those countries with the highest incidence of leprosy. Improved tools to monitor the extent of M. leprae exposure within communities would be a major help to control programs, allowing their efforts to be focused in areas of greatest need. The existing reagents, lepromin and leprosin, contain cross-reactive mycobacterial antigens and can induce positive skin test responses in BCG-vaccinated individuals (11, 28). A number of current initiatives therefore aim to develop new skin test reagents for leprosy. One approach is to fractionate the antigens of the leprosy bacillus to provide a skin test reagent (4); such fractions are highly antigenic but may not have the requisite specificity (30). Another approach is to identify synthetic peptide epitopes specific for M. leprae, which could be combined to give a reagent capable of inducing a positive skin test response in the majority of individuals from varying ethnic backgrounds and HLA types.

T-cell epitopes can be predicted using a number of algorithms, including the Rothbard model based on amphipathicity (22), and motifs predicting binding to HLA-DR (24). Although such algorithms may miss potential T-cell epitopes which can be identified using overlapping peptides spanning the protein of interest, they can be used as a screen to increase the success rate in identifying regions with the potential to induce T-cell immunity. To be included in a skin test reagent, it would be ideal if peptides contained promiscuous epitopes, such as those identified in the M. leprae 70-kDa antigen (1). In the current study, the sequences were selected to have at least three HLA-DR binding motifs, using FINDPATTERNS and appropriate search patterns, and further screened using the EpiMer algorithm (22). Using this stringent approach, all of the peptides screened as individual peptides induced a T-cell response in one or more of the subjects tested. Thus, although additional epitopes may be missed using such predictive algorithms, they are remarkably successful in predicting peptides capable of inducing T-cell activation, and the method is less labor-intensive and time-consuming than the use of overlapping synthetic peptides.

One unexpected result of the screening performed to date was the identification of many M. leprae enzymes, most of which would be involved in general, housekeeping metabolic processes, as containing epitopes recognized by human T cells. This reinforces the prediction that the immune system can recognize epitopes from within a far greater number of antigens than had previously been studied. The only peptide identified here from a previously known antigen comes from the 45-kDa serine-rich antigen (10, 29). One peptide from the 45-kDa serine-rich antigen, S9048, showed stronger responses in the leprosy patients than in the nonexposed United Kingdom donors. Another of the 45-kDa peptides tested here, S9047, was strongly recognized by both tuberculoid leprosy patients and United Kingdom blood bank donors, even though only 7 of 15 of the amino acids within peptide S9047 were identical in M. tuberculosis. As these serine-rich antigen peptides induced both specific and cross-reactive responses, it seems likely that this antigen contains both M. leprae-specific and conserved T-cell epitopes.

In the current study, both lymphocyte proliferation and IFN-γ secretion were used as readouts of a human T-cell response. Although the lymphocyte proliferation test is often used as the “gold standard” for a memory T-cell or recall response, it is clear that protective immunity to mycobacterial infection may require activation of T cells secreting type 1 cytokines, such as IFN-γ (5, 9). In the current study, measurement of IFN-γ proved a more sensitive readout of the T-cell response to individual peptides than did the incorporation of tritiated thymidine. This may reflect the accumulation of IFN-γ in the culture supernatants over the 5-day culture period, rather than the incorporation of [3H]thymidine into proliferating cells at a single time point. Although phenotype analysis of the cells producing the IFN-γ has not been performed in the centers in areas of leprosy endemicity, flow cytometric analysis on United Kingdom subjects has shown that CD3+ T cells form the majority of the cells making IFN-γ after 1, 3, or 5 days of stimulation with peptides and that CD56+ (NK) cells accounted for <10% of the IFN-γ-secreting cells on days 3 and 5; we have also been able to derive peptide-specific T-cell lines from responder subjects (S. Brahmbhatt and H. M. Dockrell, unpublished observations). As the precursor frequency of T cells responding to single peptides may be on the order of only 1 in 104 to 1 in 105, very small numbers of peptide-specific cells may be present within the cultures as produced here and the assays may lack sufficient sensitivity to detect a positive response. The thymidine incorporation assays gave more variable background responses in the five different centers participating in the study than did the IFN-γ assays, which were usually negative in unstimulated cultures. In a study by Sitz et al. (25), although peptide-specific responses could not be detected in PBMC cultures using a standard proliferation assay, CD4+ T-cell lines responsive to the same human immunodeficiency virus gp120 peptides could be derived from the subjects. Interestingly, these peptides produced delayed-type hypersensitivity responses in vivo, which correlated with the epitopes previously identified in vitro using CD4+ T-cell lines.

In the initial screening reported here, tuberculoid (TT/BT) leprosy patients were selected as a group known to be infected with M. leprae and who make good T-cell responses to leprosy antigens. To define the specificity of the peptides, a group of anonymous United Kingdom blood bank donors were used. These subjects should not have been exposed to M. leprae in the United Kingdom, and as United Kingdom blood donors are not accepted as donors if they have spent long periods living overseas, there is little chance that they have come into contact with M. leprae. Although there are a small number of leprosy cases detected in the United Kingdom each year, these are all individuals who have lived or worked in areas of leprosy endemicity overseas, and the United Kingdom can be regarded as an area where leprosy is nonendemic. Most United Kingdom blood donors would have received BCG vaccination and may in addition have been exposed to other environmental mycobacteria as well as to M. tuberculosis. This may account for the limited recognition of some of the potentially M. leprae-specific peptides by the United Kingdom subjects tested here, and further testing will include donors of known BCG vaccination status. To confirm whether the lead peptides are truly specific for M. leprae, further specificity testing will need to include patients infected with M. tuberculosis and other mycobacteria such as M. avium. Those peptides showing the highest specificity will also need to be tested in larger groups of leprosy patients in Brazil, Ethiopia, Nepal, and Pakistan and in groups of endemic controls in those countries. Subsequent studies could compare the responses to a group of lead peptides in areas of high or low endemicity for leprosy within countries. It will also be important to compare responses to such lead peptides with those induced by the fractionated M. leprae antigens currently being developed as skin test reagents for leprosy (4, 21).

One would also predict that M. leprae-specific peptides would be recognized by healthy leprosy contacts, individuals who had been in regular contact with infectious cases of leprosy over relatively long periods and who had not contracted leprosy. In most cases, the level of recognition by the leprosy contacts of the peptides tested here was similar to or greater than that seen for the tuberculoid leprosy patients, although these differences were mostly not statistically significant. Previous studies have demonstrated good recognition of leprosy proteins by healthy leprosy contacts (12) who may, following years of contact with infectious leprosy patients, have developed protective immunity with T-cell responses that are stronger than those measured in tuberculoid patients with clinical disease. However, due to uncertainty as to whether such contacts have definitely been infected with M. leprae, the leprosy patient group provides a more stringent analysis for the calculations of sensitivity. The strong T-cell responses to many of the M. leprae peptides seen with the healthy staff contacts do, however, imply that, if formulated as a skin test reagent, such peptides are likely to induce a positive response in exposed subjects who have mounted a protective immune response, as well as in contacts who may subsequently develop clinical leprosy and in those patients with clinical leprosy with demonstrable T-cell immunity. Lepromatous leprosy patients were not included in this study but would not be expected to give positive T-cell responses in vitro, nor delayed-type hypersensitivity responses in vivo to such M. leprae-specific peptides. Thus, such an M. leprae-specific skin test would provide a test for leprosy exposure rather than for the diagnosis of all forms of leprosy.

To our knowledge, no M. leprae peptides have, to date, been used as skin test reagents in humans, although dominant T-cell epitopes have been identified in a number of antigens following in vitro testing (for examples, see references 1 and 6). Previous studies have demonstrated skin test responses to mycobacterial antigens in mice or guinea pigs (3, 13, 19). A number of other studies have demonstrated the usefulness of in vitro assays for T-cell proliferation or IFN-γ secretion as good correlates of skin test responsiveness in humans (14, 18). We have also recently obtained new data from a large-scale study in Malawi which has shown that, although there are exceptions (individuals who are skin test positive and yet IFN-γ negative, or IFN-γ positive and skin test negative), there is a very strong correlation between the amount of IFN-γ-secreted in whole blood cultures in response to purified protein derivative and the diameter of the skin test induration induced in the Mantoux skin test (G. F. Black, H. M. Dockrell, and P. E. Fine, unpublished results). We therefore predict that M. leprae peptides such as those identified here will prove to be able to induce good skin test responses in humans, as previously shown for two human immunodeficiency virus peptides (25).

None of the peptides tested in the present study have induced positive IFN-γ responses in more than 46% of the tuberculoid leprosy patients, and there was also evidence of stronger recognition of certain peptides in particular ethnic groups. In view of this heterogeneity in response, it is likely that a number of peptides will need to be pooled to generate a cocktail of M. leprae-specific peptides capable of inducing positive skin test responses in the majority of those infected with M. leprae, irrespective of their ethnic background. It is, however, encouraging that many of the peptides inducing positive responses in the United Kingdom controls appear to show relatively promiscuous binding to major histocompatibility complex (MHC antigens), as shown by positive responses in subjects who expressed a number of different HLA-DR types. Such promiscuous epitopes have previously been identified in other mycobacterial antigens such as the M. leprae 65-kDa heat shock protein (23) and the M. tuberculosis 19-kDa antigen (15) and would be particularly suitable for inclusion in a skin test reagent to be used in a variety of ethnic groups. It was interesting that not all donors expressing the appropriate MHC types made a positive IFN-γ response to peptide; this may reflect a lack of priming or boosting with cross-reactive mycobacterial antigens, resulting in the absence or low frequencies of peptide-specific T cells.

It was interesting that using the presence of ≥5 of 15 amino acid mismatches between the equivalent M. leprae and M. tuberculosis sequences as an indicator of specificity did not predict functional specificity, as defined by positive responses in leprosy-exposed or -infected individuals compared to United Kingdom control subjects who would not have been exposed to leprosy. Obviously, the location and nature of any amino acid substitutions will affect antigenicity, with changes at the ends of the peptide being less critical than those which affect the MHC binding or T-cell receptor contact residues. However, the failure of such a simple criterion to predict specificity may also indicate that T-cell responses to homologous antigens in other members of the mycobacterial family may also induce cross-reactive responses. This issue will be clarified as the sequencing of additional mycobacterial species is completed. The converse was, however, equally true—peptides with an identical sequence in M. tuberculosis and M. leprae could produce good cell responses in leprosy patients but not in United Kingdom controls. It is possible that such peptides are not expressed by M. tuberculosis, and if so, they should fail to stimulate T cells from tuberculosis patients. On the other hand, United Kingdom subjects may also have very little exposure to M. tuberculosis. Within countries of leprosy endemicity, the prevalence of tuberculosis is often much higher and such peptides would therefore not be suitable as a diagnostic tool. With the completion of the M. leprae genome project, it may, however, be possible to identify whole genes that are present in M. leprae and not in M. tuberculosis, and which might contain peptide epitopes with greater specificity for M. leprae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the clinicians, leprosy technicians, and field workers who helped provide the clinical samples used in the study; Kate Britton, LSHTM, United Kingdom, for technical assistance; Thomas Chiang and Shahid Zafar, Marie Adelaide Leprosy Centre, Karachi, Pakistan; Ruth Butlin, Anandaban Leprosy Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal; and José Nery, Harrison M. Gomes, and Eliane B. Oliveira, Leprosy Laboratory, FIOCRUZ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. We also thank Anne de Groot for performing the EpiMer analysis and Sian Floyd for performing the statistical analyses. We also thank Nick Davey of the Hammersmith Hospital, London, for performing HLA typing. We thank Paul Fine, Patrick Corran, Stewart Cole, and Gilla Kaplan for helpful discussions.

This study was performed by a task force set up by the IMMYC Steering Committee of the World Health Organization and was funded by the World Health Organization. Shweta Brahmbhatt is supported by a studentship from the Hospitals and Homes of St. Giles, United Kingdom.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams E, Britton W, Morgan A, Sergeantson S, Basten A. Individuals from different populations identify multiple and diverse determinants on mycobacterial HSP70. Scand J Immunol. 1994;39:588–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1994.tb03417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson D C, Van Schooten W C A, Barry M E, Janson A A M, Buchanan T M, De Vries R R P. A Mycobacterium leprae-specific human T cell epitope cross reactive with an HLA-DR2 peptide. Science. 1988;242:259–261. doi: 10.1126/science.2459778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashbridge K R, Backstrom B T, Liu H-X, Vikerfors T, Englebretsen D R, Harding D R K, Watson J D. Mapping of T helper cell epitopes by using peptides spanning the 19-kDa protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Evidence for unique and shared epitopes in the stimulation of antibody and delayed-type hypersensitivity responses. J Immunol. 1992;148:2248–2255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan P J, Cho S N, Klatser P R. Immunodiagnostics, including skin tests. Int J Lepr. 1996;64:58–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caruso A M, Serbina N, Klein E, Triebold K, Bloom B R, Flynn J L. Mice deficient in CD4 T cells have only transiently diminished levels of IFNg, yet succumb to tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1999;162:5407–5416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chua-Intra B, Peerapakorn S, Davey N, Jurcevic S, Busson M, Vordermeier H M, Pirayavaraporn C, Ivanyi J. T-cell recognition of mycobacterial GroES peptides in Thai leprosy patients and contacts. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4903–4909. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4903-4909.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davis R, Devlin K, Feltwell K, Gentles N, Hamlin S, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail M A, Rajandream M-A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Sulston J E, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole S T. The Mycobacterium leprae genome project. Int J Lepr. 1998;66:589–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper A M, Dalton D K, Stewart T A, Griffin J P, Russell D G, Orme I M. Disseminated tuberculosis infection in interferon-gamma gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243–2247. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Wit R T F, Clark-Curtiss J E, Abebe F, Kolk A H J, Janson A A M, van Agterveld M, Thole J E R. A Mycobacterium leprae-specific gene encoding an immunologically recognized 45kDa protein. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:829–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dharmendra D B, Jaikaria S S. Studies of the Lepromin test. Results of the test in healthy persons in endemic and non-endemic areas. Lepr India. 1941;13:40–47. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dockrell H M, Stoker N G, Lee S P, Jackson M, Grant K A, Jouy N F, Lucas S B, Hasan R, Hussain R, McAdam K P W J. T-cell recognition of the 18-kilodalton antigen of Mycobacterium leprae. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1979–1983. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.7.1979-1983.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estrada G I C E, Gutierrez M C, Esparza J, Quesada-Pascual F, Estrada-Parra S, Possani L D. Use of synthetic peptides corresponding to sequences of M. leprae proteins to study delayed type hypersensitivity response in sensitized guinea pigs. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1992;60:18–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiavey K, Frankenburg S. Appraisal of the total blood lymphocyte proliferation assay as a diagnostic tool in screening for tuberculosis. J Med Microbiol. 1992;37:283–285. doi: 10.1099/00222615-37-4-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris D P, Vordermeier H M, Arya A, Moreno C, Ivanyi J. Permissive recognition of a mycobacterial T cell epitope: localisation of overlapping epitope core sequences recognised in association with multiple major histocompatibility complex class II I-A molecules. Immunology. 1995;84:555–561. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter S W, Rivoire B, Mehra V, Bloom B R, Brennan P J. The major native proteins of the leprosy bacillus. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14065–14068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lalvani A, Brookes R, Wilkinson R J, Malin A S, Pathan A S, Andersen P, Dockrell H, Pasvol G, Hill A V. Human cytolytic and interferon gamma-secreting CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:270–275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lein A D, Von Reyn C F. In vitro cellular and cytokine responses to mycobacterial antigens: application to diagnosis of tuberculosis infection and assessment of response to mycobacterial vaccines. Am J Med Sci. 1997;313:364–371. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199706000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mackall J C, Bai G H, Rouse D H, Armoa G R G, Chuidian F, Nair J, Morris S L. A comparison of the T cell delayed-type hypersensitivity epitopes of the 19-kDa antigens from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium intracellulare using overlapping synthetic peptides. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;93:172–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb07961.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahairas G G, Sabo P J, Hickey M J, Singh D C, Stover C K. Molecular analysis of genetic differences between Mycobacterium bovis BCG and virulent M. bovis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1274–1282. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1274-1282.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manandhar R, LeMaster J W, Butlin C R, Brennan P J, Roche P W. Interferon gamma responses to candidate leprosy skin test reagents detect exposure to leprosy in an endemic population. Int J Lepr. 2000;68:40–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meister G E, Roberts C G P, Berzofsky J A, De Groot A S. Two novel T cell epitope prediction based on MHC-binding motifs; comparison of predicted and published epitopes from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and HIV protein sequences. Vaccine. 1995;13:581–591. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)00014-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mustafa A S, Lundin K E, Meloen R H, Shinnick T M, Oftung F. Identification of promiscuous epitopes from the mycobacterial 65-kilodalton heat shock protein recognized by human CD4+ T cells of the Mycobacterium leprae memory repertoire. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5683–5689. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5683-5689.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rammensee H-G, Freide T, Stevanovic S. MHC ligands and peptide motifs: first listing. Immunogenetics. 1995;41:178–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00172063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sitz K V, Loomis-Price L D, Ratto-Kim S, Kenner J R, Sau P, Eckels K H, Redfield R R, Birx D L. Delayed type hypersensitivity skin testing using third variable loop peptides identifies T lymphocyte epitopes in HIV-infected persons. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1085–1089. doi: 10.1086/516517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith W C S. We need to know what is happening to the incidence of leprosy. Lepr Rev. 1997;68:195–200. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19970026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorensen A L, Nagai S, Houen G, Andersen P, Andersen A B. Purification and characterization of a low-molecular-mass T-cell antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1710–1717. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1710-1717.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas J, Joseph M, Ramanujam K, Chacko C J G, Job C K. The histology of the Mitsuda reaction and its significance. Lepr Rev. 1980;51:329–339. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19800035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vega-Lopez F, Brooks L A, Dockrell H M, De Smeet K A L, Thompson J K, Hussain R, Stoker N G. Sequence and immunological characterization of a serine-rich antigen from Mycobacterium leprae. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2145–2153. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2145-2153.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weir R E, Brennan P J, Butlin C R, Dockrell H M. Use of a whole blood assay to evaluate in vitro T cell responses to new leprosy skin test antigens in leprosy patients and healthy subjects. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;116:263–269. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00892.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkinson R J, Wilkinson K A, Jurcevic S, Hills A, Sinha S, Sengupta U, Lockwood D N J, Katoch K, Altman D, Ivanyi J. Specificity and function of immunogenic peptides from the 35-kilodalton protein of Mycobacterium leprae. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1501–1504. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1501-1504.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]