Abstract

Introduction

Scarce health resources and differing views between persons with hand osteoarthritis (OA) and health professionals concerning care preferences contribute to sustaining a gap between actual needs and existing clinical guidelines for hand OA. The aim of this study is to explore the experiences of persons diagnosed with hand OA in their encounters with health services and how those experiences influence negotiations and decision‐making in hand OA care.

Methods

Data from 21 qualitative interviews with persons diagnosed with hand OA were collected, transcribed verbatim and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Results

Three main themes were developed: symptoms are perceived as ordinary ageing in everyday life, consultations are shaped by trust in healthcare and the responsibilities of prioritisation and self‐care govern interactions.

Conclusion

Ideas of ageing, professional knowledge and self‐management dominate hand OA health encounters and contribute to shaping illness perceptions, preferences and opportunities to negotiate decisions in consultations.

Patient or Public Contribution

Two patient research partners with hand OA are members of the study project group. One of them is also a co‐author of this manuscript.

Keywords: agenda‐setting, chronic condition, decision‐making, hand osteoarthritis, healthcare consultations, self‐management

1. INTRODUCTION

The global burden of osteoarthritis (OA) accelerates with an ageing population, 1 posing challenges for health services. 2 Hand OA services aim to care, not cure. Progress is limited in developing effective treatments. 3 , 4 While hand OA has recently gained increased attention, 5 interventions do not fully consider persons with hand ailment in their encounters with the health system. 6 Poor access to treatment, 5 low consultation rates, 7 , 8 delayed contact with health services 9 , 10 and symptoms perceived as inevitable with ageing 11 are reported. This contributes to hesitance in seeking health services attention 12 , 13 and beliefs that the condition does not justify treatment. 7 , 14

The health‐seeking process is complex, 15 and people with hand symptoms report a lack of information 16 , 17 and dissatisfaction with consultations and treatments, 18 , 19 contributing to their experiences of having a condition that does not get the attention it deserves. 9 Differences between people with hand symptoms and health providers on OA care 16 , 20 , 21 underline the importance of enhancing the perspectives of people with hand ailment to reduce the gap between their perceived needs and existing guidelines for hand OA. Current research is limited to experience with recommended treatments, where shared decision‐making 22 does not fully address the complex nature of negotiations and governing motives in consultations. Our study aimed to contribute to the limited set of studies on decision‐making in healthcare consultations from the perspective of persons with a chronic condition.

We saw consultations between people with hand ailments and health professionals as encounters where negotiation takes place. Erving Goffman 23 inspired our understanding of the concept of ‘encounter’ as a social organisation where certain rules exist. Thus, consultations encompass obligations and expectations, serving as a location for interaction. 23 By using the concept of encounter, we highlighted consultations as structured and governed by layers of rules, norms and societal values while also acknowledging that negotiations within encounters are less formal and point to adjustments made in consultations to comply with institutional demands. 24

We included power dimensions to our analysis through Steven Lukes' 25 work to enable situations of ‘being liberated from certain power relations and of the reduction of power within a relation’. 26 ,p.27 We argue that hand‐OA discursive ideas influence participation. Lukes' emphasis on power dimensions is useful to our analysis as it allows us to think through how power is exercised within healthcare, where asymmetry and power in relations might be difficult to observe. This conceptualisation of power is generative for grasping how power relations play out, impact encounters and subsequently influence negotiations to reach decisions in healthcare.

Lukes' 25 three power dimensions are decision‐making, agenda setting and ideological power. The decision‐making power, overt and direct, aims to reach specific results in conflict situations. The agenda‐setting power, indirectly exercised, portrays how decisions linked to the potential conflict are prohibited from being taken. Ideological power, concealed and embedded in structures and institutions, rises beyond individual actors so that the exercise of power is taken for granted.

The decision‐making process in healthcare has gradually shifted from one of the passive patients to one of the responsible patients, 27 with the aim of redistributing power. 28 , 29 These processes, framed within the democratisation of health services, contribute to new understandings of health encounters. 30 By linking actual negotiation processes in encounters with larger structural considerations of power, we ask how decisions are made in hand OA healthcare consultations.

2. METHODS

2.1. Context

The Norwegian state plays a central role in providing access to fundamental goods, including healthcare. 30 In Norway, due to poor access to relevant hand OA services in primary healthcare, persons with hand symptoms are referred for hospital consultations with rheumatologists and occupational therapists. The two hospitals from which participants in this study were recruited specialise in rheumatology and were chosen based on their similarities in providing services to persons with hand OA while also featuring different local processes. 31 The diagnosis is made based on patient history and clinical examination. 32 Symptoms are hand pain and stiffness, which affect one in two women and one in four men. 33 Recommended general treatment includes information on hand OA and exercises for the hands, whereas orthotics, pain medication and surgery are considered individually. 5

2.2. Research team

This study is part of a three‐phase project that aims to understand current hand OA pathways, including patient experiences and professional practices. A randomised controlled trial (RCT) was initiated in 2017 (400 participants), 34 followed by an ongoing qualitative study and a Delphi consensus process planned from 2023. The first author, H. J. M., is a PhD student and a physiotherapist with 20 years of clinical and managerial health and humanitarian experience. The co‐authors include professors, an associate professor, clinicians and a patient research partner. We also consulted with an international advisory board of researchers with various professional backgrounds.

2.3. Participant recruitment, eligibility and demographics

Between December 2020 and December 2021, we recruited 21 persons diagnosed with hand OA who had received primary and specialised healthcare. An occupational therapist in each hospital identified participants and informed them about the study before their inclusion. These gatekeepers were instructed to draw on varying age, gender and hand OA duration in the purposive participant sampling. Twelve participants were recruited from one hospital based on prior inclusion in the completed RCT. The other nine participants were recruited from a hospital in a different geographical area based on their participation in a hand OA education programme. Interviews were scheduled within 1 month from recruitment. Two persons withdrew prior to interviews, reporting time constraints and long‐term illness. To reduce the risks of obligatory participation when recruited by an occupational therapist on whom they depended for services, H. J. M. presented study objectives, consent form and her nonaffiliation with the hospitals to participants before interviews. Fifteen women and 6 men aged 47–86 were included. They had symptoms that had been present for the previous 2–20 years. Participants included 13 in retirement, 5 in full‐time positions, 1 jobseeker and 2 with disability benefits. Only two participants were under 60 years, which may be due to perceptions linking symptoms to ageing and subsequent delays in seeking healthcare. Additionally, we only succeeded in recruiting one participant with an immigrant background, which may reflect barriers to accessing specialised healthcare and participating in research for immigrants. Busy clinical gatekeepers may also have resulted in recruiting those most accessible.

2.4. Data collection

Through a qualitative research design, informed by a constructionist epistemology, 35 we collected data using qualitative interviews. An interview guide (Supporting Information: Appendix 1), piloted with two patient research partners, including content about initial contact with health services, encounters with health professionals, treatment and self‐care strategies. Nineteen interviews took place in person, while two participants chose digital interviews. One participant had his spouse present upon request. Interviews lasted 55–90 min each and were audio‐recorded. Data were stored on the secure platform services for sensitive data, in compliance with the Norwegian privacy regulation, including immediate encrypted audio files transfer post‐interviews. Participant anonymity was safeguarded through separate participant information and data file storage. Through research team discussions, information power was reached after 21 interviews. 36 The broad study aim and cross‐case analysis required more participants, while H. J. M.'s experiences as a qualitative researcher with some theoretical knowledge and skills to establish a good dialogue called for fewer participants.

2.5. Data analysis

We applied reflexive thematic analysis 37 to endorse the process of researcher subjectivity and the situated generation of knowledge to report patterns. 38 NVivo (released in March 2020) was used to structure the data. H. J. M. conducted all interviews and subsequent verbatim transcriptions, 39 reading and rereading transcripts to become familiar with the breadth and depth of the content while taking reflective notes. Postinterview debriefs with co‐authors took place to emphasise how H. J. M. influenced the research process and data construction. Our orientation to data was to interpret meaning beyond what participants explicitly communicated. We engaged empirical data and theoretical understandings in parallel. 40 H. J. M. developed semantic and latent codes inductively from reading the data, alternating with personal experiences and academic literature with a focus on microlevel interactions. 41 After several rounds of research team discussions, including one session discussing two different interview transcripts in detail, we sorted main codes into potential themes before presenting preliminary results to the advisory board. Themes were thereafter reviewed and refined to ensure relevance to the coded extracts and that we had captured patterns of shared meaning across the data set. 42 In reviewing themes, we added power dimensions to our analysis in an effort to grasp the complex decision‐making process where sociocultural factors were seen to influence perceptions and actions. This iterative process helped us to gain a deeper understanding of the themes and how they connect in telling an overall interpretive story (Table 1). 43

Table 1.

Codes and themes development.

| Examples of data‐driven recurring codes | Refined codes | Preliminary themes | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hand OA is a common condition | Adapting to the ailment | The common person with a hand ailment | Symptoms of ordinary ageing in everyday life |

| Changes in hands go unnoticed | Does not regard own ailments as illness | ||

| Have gotten used to the discomfort | Minimising the severity of the condition | ||

| Hand OA is not a severe condition | |||

| Found ways to live with hand OA | |||

| Hand ailment addressed by chance | Serendipitous ways to health attention | The fortunate person with a hand ailment | |

| Hand ailment expected with age | Does not deserve healthcare | The unobtrusive person with a hand ailment | |

| Do rarely make use of health services | Having a disease with low status | ||

| Delay in initiating contact with health services | |||

| Challenging to speak up about hand ailment | Moderation in health encounters | ||

| Difficult to know what questions to ask in consultations | |||

| Discomfort difficult to explain | |||

| Could have made stronger demands in consultations | Does not want to become a liability | ||

| Don't want to be seen as a difficult patient | |||

| Open‐minded towards health services upon entering | Placing confidence in health service | The trusting person with a hand ailment | Consultations shaped by trust in healthcare |

| Confidence in people who know what they do | Health professionals have expert knowledge | ||

| In the hands of competent professionals | Confidence in healthcare professionals to safeguard their interests | ||

| Respecting the work of health professionals | |||

| Entered the consultation with a blank slate | Underestimating knowledge about one's own illness | ||

| Agreeing with what health professionals recommend | Health professional agenda setting | ||

| Healthcare providers are gatekeepers to goods and services | |||

| Dependence on health professionals | |||

| Health professionals showed an interest | Well‐being in consultations with health personnel | ||

| Importance of being believed in consultations | Health professional's recognition of hand ailment | ||

| Health professionals provided explanations | Recommendations from healthcare professionals are taken seriously | ||

| Health professionals came up with solutions | Health professionals are seen to safeguard patient interests | ||

| Do not want to be a burden | The ideal is to be a considerate patient | The responsible person with a hand ailment | The responsibilities of prioritisation and self‐care govern interactions |

| Politeness in consultations | Comparing one's own needs with the needs of others | ||

| Others with larger needs deserve healthcare more | Do not want to burden the healthcare system | ||

| Other own ailments are more in focus | Priorities amongst own conditions/ailments | ||

| Few opportunities to get better | The initiative is with the person with a hand ailment | ||

| No available treatment | Responsibility for providing relevant information in consultations | ||

| Own effort expected | Lack of own openness reason for not receiving relevant support | ||

| Home exercises are the only solution | |||

| Active in consultations | |||

| Hand OA is one's own fault | Own fault that the illness progressed | ||

| Could have spoken up earlier | Delay in health seeking | ||

| One must ask to get answers | Lack of preparedness in advance of consultations | ||

| Not well prepared for consultations | Own responsibility when improvement is not achieved | ||

| Not good enough to follow up on recommendations | |||

| Keep consultation time | Accountable to healthcare professionals | ||

| Health professionals have a busy schedule | Do not want to burden the health system | ||

| Facilitates efficiency at the expense of one's own needs |

Abbreviation: OA, osteoarthritis.

3. RESULTS

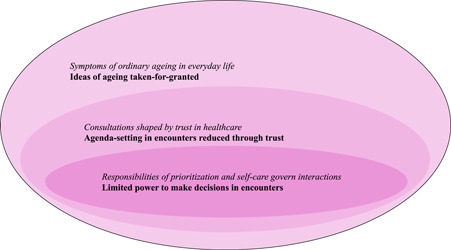

We developed three main themes from codes as presented in Table 1 to capture how decisions are made in healthcare consultations (Figure 1). First, persons with hand ailment bring taken‐for‐granted ideas about symptoms of ordinary ageing in everyday life (outer circle) into consultations that are shaped by trust in healthcare (middle circle). This limits the power to make decisions in encounters when the responsibilities of prioritisation and self‐care govern interactions (inner circle).

Figure 1.

Illustration of the study results, inspired by Goffman's encounter concept combined with Lukes' power dimensions.

3.1. Symptoms of ordinary ageing in everyday life

Hand pain and functional limitations were described by many participants as common, a product of ageing and nontreatable, contributing to limit contact with health services: ‘There is nothing that can be done about it, and it is so common. And of course, when you age as well, then there is more of it’ (Woman86). When linking it both to ageing and the notion that nothing can be done to address the challenges, she reduces the hand OA significance and accompanying needs. This might explain why most study participants also described symptom onset years before initiating contact with the healthcare system, keeping diffuse symptoms to themselves.

Some participants frequently used the word discomfort rather than pain in interviews when they talked about their hand condition, further underplaying the severity. ‘Well, it probably has something to do with age and the fact that I am more than 75 years old and have experienced almost everything, for better or worse. So, that is how it is, and if you don't have more severe pain than what I have, then I must live with that’ (Man75). The man also points to old age as a factor in explaining hand symptoms. Simultaneously, he highlights a situation that he takes for granted and adapts to without expecting health interventions.

When participants finally entered health services, it was often in conjunction with another health‐related matter, substantial symptoms of deterioration or by chance. As one participant with an accident resulting in a thumb fracture for which X‐rays identified the hand OA said: ‘I must feel like I am ill to go to see a doctor. I have probably not perceived this as being illness and that might be one of the reasons for not following up on it myself or making demands in consultations’ (Man70). This man had noticed changes in his hands for years prior to the accident and had not considered investigating them further or positioning the condition of his hands within an illness narrative. Another participant said the following: ‘Even though my hands hurt, I am not ill’ (Woman68). When discomfort does not constitute illness, it becomes difficult to justify seeking healthcare, strengthening the taken‐for‐granted notion of not being entitled to healthcare. This presents challenges for having the condition assessed and managed on time.

3.2. Consultations shaped by trust in healthcare

Participants in the study talked about trust on various levels, from their trust in the overall health system through trust in health providers as a professional group to trusting individual health providers. As one participant said: ‘I do have this genuine trust in the healthcare system telling me that if I can make it inside, I will be well cared for’ (Man70). This man channels the genuine trust embedded in him to the system level of healthcare, expressing confidence and good faith as part of health‐seeking, expecting to be cared for upon entering. Through this trust, he attributes good intentions to the healthcare system for assisting him with hand changes that he is no longer able to fully understand or manage. Correspondingly, another participant said that he was not in the driver's seat, further illustrating how participants leave it to health professionals to set the agenda for consultations. This social form of trust provides scaffolding for interactions and was also expressed by one participant who, at the same time, extended her trust beyond the institution.

In general, I have trust in the healthcare system and in the people who are there because they know their jobs. I believe that trust is important to bring along. I am not very sceptical, like why are they saying that, why are they doing this. People talk and are present and provide information, and that brings trust, I think. In addition, I know that they are professionals. (Woman73)

This woman extends her trust in the institutional health system to the individuals who conduct the work. Her trust in their expertise is based on their knowledge and skills, and she highlights their positions as professionals as a factor in trusting them. Participants in the study considered health professionals as experts in addressing hand OA challenges.

However, several participants said that they were not comfortable expressing their own opinions beyond politeness during consultations and, in retrospect, could have made stronger demands. They found it difficult to know what questions to ask when marginalising their own knowledge about hand OA, as conveyed by one participant: ‘I have not been in what we can call situations of conflict with health professionals in that way. Absolutely not. It has been like an open dialogue. For the most part, I have agreed to what they have suggested. I don't have the knowledge to oppose that’ (Man70). He talks about an open dialogue where consensus prevails and where he does not question professional suggestions in consultations due to his own lack of knowledge. Thus, professional knowledge is not up for debate when taken for granted by the participants.

The trust described by participants is present independently of the health system level or profession and further encompasses personal trust in individual health providers: ‘She is genuinely nice like that, sees you and is present. Yes. Like it is just you there. Not all the others, like it is just you’ (Woman68). This participant points to the health providers' ability to acknowledge the symptoms and to recognise the participant as a unique individual. In this way, the participant experiences being the focus of the consultation through the professional and interpersonal skills of the health professional.

Some participants also referred to situations in which trust was absent. The two participants on the state disability pension, for example, expressed a lack of trust in the health system stemming from not being trusted by that same system. They do not trust an institution they believe questions their narrative, while at the same time expressing positive experiences with health professionals in hand OA consultations: ‘It was good for me that someone said, “I see that it is painful.” I felt I got help, really. And was believed in. That is the most important thing. To be believed in’ (Woman60). In this consultation, the lack of institutional trust was outweighed by trust in an individual health provider with the ability to acknowledge the woman's pain, demonstrating how trust in an individual can be present despite the absence of institutional trust.

3.3. Responsibilities of prioritisation and self‐care govern interactions

Notwithstanding the trust, participants also described a social responsibility when comparing their own illness with others whom they perceived to need healthcare more: ‘I think it is something inside me telling me that I should not annoy that doctor. Because he probably has many others who are more ill than I. That is where I am at, yes’ (Woman70). This illustrates how the participants' social responsibility to not burden the healthcare system is prominent when pointing out that other individuals deserve medical attention more than she does. Thus, participants see it as an obligation on behalf of society at large to downgrade their own needs by prioritising. This loyalty towards society shows a complex process of seeking and receiving healthcare, where their understandings and actions cannot be detached from the environment in which their lives play out. Consequently, moderation in seeking and obtaining healthcare prevails. Moderation in encounters is accentuated amongst numerous participants beyond the downgrading of their own condition in comparison with others, as shared by another participant:

Well, there is this thing about being open about my situation. I know that myself. I am not open about myself all the time. That I can exit the doctor's office and think to myself, why did I not address that? But it is something about the time they have set aside. You know that they have scheduled a fixed time. And then you are not supposed to exceed their time. (Woman72)

This woman finds it challenging to bring her hands to the health professionals' attention. She remains quiet about her own needs in an effort to avoid becoming a burden. Upon exiting the consultation, she reflects on why she did not bring forward concerns about her hands and pointed to a time. In this way, time becomes a responsibility factor when participants talk about the importance of not exceeding consultation time. They express an obligation to keep consultations short, adhering to the rules of the encounter. Hence, the norm of time outweighs one's own concerns and becomes a barrier to present needs.

In contrast, one younger participant in the study who found it challenging to conduct his work as a craftsman said: ‘I can sit for a long time if there is a need for that. Others must wait, then. When it is my turn’ (Man58). The man is not concerned with consultation time and does not adapt his own needs to the health provider's schedule. As such, the responsibility to address one's own needs triumphs over the health providers' busy schedule and societal needs. One explanation for his differing opinion might be that there is more at stake for people for whom functional hands are a prerequisite for employment and income. Accordingly, a moderate approach is replaced by more direct attention to one's own situation when decisions are made in consultations.

With few treatment options available for hand OA, most participants talked about a responsibility to respond to their own needs, as expressed by one participant: ‘You should preferably get well by yourself’ (Man71). The man points to self‐care as the proper way to respond to needs in the absence of other relevant treatment. In this way, few expectations exist for health system interventions. This social responsibility to prevent social expenses on healthcare is seen as directing personal decision‐making processes. By taking on individual responsibilities for self‐care, participants at the same time attribute a lack of progress and result in managing the condition to their own lack of initiative.

4. DISCUSSION

Our study aim was to explore the experiences of persons diagnosed with hand OA in their encounters with health services and how these experiences influence decision‐making in hand OA care. The results show that people with hand ailments bring trust into encounters with health professionals for a condition they perceive to be age‐related and ordinary. They also give accounts of responsibilities to prioritise and self‐care in a process shaped by hand OA as a chronic condition, influencing the definition of needs, how those needs are responded to and by whom.

4.1. Ideas of ageing taken for granted

In this study, participants viewed symptoms as part of ordinary ageing. Moreover, they downplayed severity, which strengthened the notion of not being entitled to healthcare when comparing their own situation with that of others. This aligns with other studies, 15 , 44 in which the perceived worthiness of the illness was judged through social comparison when considering whether to consult health services. The ‘ordinary ageing’ narrative generated in our analysis corroborates previous findings. 11 , 12 , 45 The meaning our participants attributed to symptoms is an ongoing and complex social process. It is influenced by how symptoms are perceived within a wider socio‐political context where power over worldview, as Lukes 25 writes, contributes to shaping the roles and identities of ageing people with chronic conditions. 46

Participants similarly pointed to the ordinary role that hands play in everyday life despite symptoms, referring to diffuse and unnoticed changes. When considerations of healthcare attention are marginalised, and ageing takes prominence, the actions of persons with hand ailments are shaped prior to, during and after consultations. As such, they accept their position within an existing order and bring society's view of themselves into encounters, as said by Goffman. 23 When wider society's identity beliefs position hand OA within a natural ageing frame, symptoms are accepted as normal. Contrasting Henselmans and colleagues' 47 reports of active patients with chronic illnesses in consultations, our analysis shows how moderation in the illness experience impacts the actions taken, if any, by persons diagnosed with hand OA.

Severity and acuteness dominate health policy priority‐setting and resource allocation. 48 , 49 Our participants conveyed that other people with more severe conditions should have priority over them and deserve healthcare more. In this way, participants in our study acted on the limited power given to them by overarching health priorities, positioning hand OA at the lower end of the prestige hierarchy 50 and thus surrendering their spot to others becomes the action. As such, participants get responsibilities beyond catering to their own needs when they feel obliged to also preserve collective interests. Our results show attitudes of modesty as a response to efforts to align with expectations.

When a hegemony linking hand OA with ageing and the low societal priority becomes significant in regulating how persons diagnosed with hand OA negotiate in consultations, the characteristics and stability of such encounters are intertwined with the wider social world. We argue that accepted understandings in society regarding ageing govern interaction in consultations.

4.2. Agenda‐setting in encounters reduced through trust

In our study, trust in health professionals as experts dominated encounters. Grimen 26 argues that there are few alternatives to trusting in interactions between patients and health professionals, where patients are structurally inferior and dependent. He points to a knowledge gap, making it difficult for patients to challenge health professionals' judgements. As such, the taken‐for‐granted position of epistemic superiority of health professionals over patients shapes the definition of and response to needs. 51

The literature points to an understanding of health professionals as experts, 15 , 52 where high trust levels coincide with a passive patient role 53 and where unvoiced patient agendas in consultations influence outcome, 21 , 54 resonating with our study results where health professionals control the agenda. As such, the dominant values and beliefs embedded in expert knowledge shape the consultation. The domination of the task‐oriented agenda of health professionals based on technical skills and clinical guidelines oriented towards the disease is reported in several studies 20 , 55 and might not cohere with the agenda of the silent person with an illness. 21

Conversely, Porcheret and colleagues 56 found shared preferences for a biomedical approach during OA consultations, while Feddersen and colleagues 57 found that the biomedical knowledge of nurses facilitated dialogue on the illness experience of women with rheumatoid arthritis, resulting in shared decision‐making. Our results, in contrast, show a knowledge gap in which persons diagnosed with hand OA talk about their own lay knowledge as substandard compared with health professionals' elevated knowledge.

Additionally, when hand OA consultations become procedural, the negotiation space of patients narrows as adherence to rules defines action more than active and negotiated processes. This leaves aspects unspoken in consultations, consequently preventing decisions from being made when applying Lukes' 25 agenda‐setting power lens to the participants in our study saying that they could have made stronger demands in consultations in which they did not actively control the time or direction. This shows how dynamics in encounters are framed by invisible structures governing the actors' thoughts and actions to sustain order.

The perceived lay knowledge inferiority might also contribute to the consensus portrayed by participants when health professionals' opinions are taken for granted, which is harmonious with Lukes' 25 third dimension of power. As such, an absence of conflict prevails in interactions, even though the interests of persons diagnosed with hand OA might not be in line with health professionals' knowledge or actions. This resonates with a study by Lian and colleagues 58 in which patients in consultations responded politely to questions, rarely asking questions and making few attempts to set the agenda. In our study, when persons diagnosed with hand OA did not express their concerns, those concerns were not addressed.

Although trust within healthcare is seen as contributing to health system functioning 59 and enhanced health outcomes, 60 we argue that trust also contributes to sustaining the agenda‐setting power of health professionals when persons with hand ailments take expert knowledge for granted. Expert knowledge reinforces the power hierarchy when persons diagnosed with hand OA influence healthcare provisions less than the health professionals with whom they interact.

4.3. Limited power to make decisions in encounters

Our study shows how participants describe managing hand OA on their own when few other options are made available to them. In this process, they also become accountable for the lack of improvements when the aim is to care for, not cure, hand OA. Support for self‐management is recognised as central in responding to chronic health needs. 61 Self‐management in hand OA care aims to improve patient autonomy, 5 and shared responsibilities between health professionals and patients are reportedly facilitating self‐management in rheumatology. 62 Subsequently, the decision to self‐manage hand OA can be viewed as a shared responsibility where negotiation in consultations evolves around the interests of persons with hand OA.

Concurrently, significant disparities have been reported between patients with arthritis and health professionals regarding whether support for self‐management has occurred. 63 Moreover, what happens in consultations is influenced beyond individual interactions through socio‐political factors. Norwegian health policy and practice position self‐management as central in responding to growing demands for healthcare even though there is inconclusive evidence to support the cost‐effectiveness of such approaches. 61 , 64 , 65 Self‐management strategies can be seen as shifting responsibilities from policy and professional levels to individuals, 66 in line with the experiences of participants in our study. Thus, the allocation of resources becomes a driving force more than the actual needs of individuals with chronic conditions, contributing praise for those who have the capacity to take on such responsibility while marginalising those who do not. 67 , 68

Persons with ordinary diseases that are expected with age and have no cure in our case accepted self‐management within a frame of patient autonomy and the politics of health resources. In this way, the interests of persons with chronic diseases are shaped by pre‐existing and overarching ideological patterns in society, presenting self‐management as the norm in chronic care. Thus, the interests of persons diagnosed with hand OA are silenced by larger societal considerations where a transfer of responsibilities in the name of patient autonomy and empowerment can be seen as influencing persons with a chronic condition to accept self‐management.

Even though the intentional actions of persons with a chronic hand condition cannot be excluded from consultations, we argue that negotiations in hand OA care, when exercised under dominant age and self‐management influences, limit the agenda and participation of persons with perceived age‐related chronic conditions in defining and responding to needs.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

The present study addresses a knowledge gap by shedding light on multiple factors influencing consultation dynamics and opportunities for decision‐making in hand OA care, which might be relevant given the large population of persons with chronic conditions. While a single analyst allowed for prolonged and deep engagement with the data, continuous discussions between authors throughout the analytical process generated important reflections about H. J. M.'s engagement with participants and the data.

Although Goffman 23 and Lukes 25 provided the lens for understanding interactions in consultations, certain facets of the results were not captured through encounters or power dimensions. The lack of trust by participants in disability pensions and the experiences of individual needs outweighing social responsibilities are examples of how participants also break norms and make independent choices when they act on unstable and varying interests influenced by relations and circumstances.

We recognise that the time between symptom onset and consultations, as well as experiences with other conditions and services, shaped what our participants found acceptable, emphasised and conveyed during interviews. This might be a limitation, but it might also strengthen potential applicability to chronic conditions beyond hand OA.

5. CONCLUSION

Our study shows how symptoms are seen as ordinary and expected with age, which subsequently delays health‐seeking and influences decision‐making. The trusting person with a chronic hand condition rarely sets the agenda in encounters with health professionals when negotiating over a condition expected with age and with few interventions beyond self‐management. As such, persons with chronic conditions become responsible for addressing their own needs. We highlight health consultation complexities with relevance for persons with chronic conditions, health professionals and policymakers when optimising clinical practice and active participation, contributing to reduce gaps between patient needs and clinical recommendations. Stronger awareness amongst health professionals about power dimensions in consultations can accelerate opportunities for persons with chronic conditions to increasingly influence the consultation agenda and outcome. Moreover, alternatives to prominent self‐management approaches, such as increased health professional involvement for patients needing stronger support, should be considered in providing relevant and equitable healthcare.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (case number 2017/742, 2020/8450) and the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (reference number 197320) approved the research project, which was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was provided by participants before interviews and continuously negotiated. We informed participants of their rights to withdraw from the study anytime, without consequences, and that their data would be anonymised. We strived to be well prepared, attentive to participants, maintain their integrity and continuously reflect on the processual, relational and situational nature of the study. For example, when participants expanded their illness experiences well beyond hand osteoarthritis, H. J. M. made efforts to respectfully get back on track. Even though H. J. M. is also a health professional, the researcher's role was sustained throughout the interviews. Clinical requests from participants were, upon their approval, channelled to the gatekeeper for follow‐up. The PhD student role was emphasised, aiming to reduce the distance between H. J. M. and participants, where participants were perceived as experts in sharing their experiences.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the participants for their time and insights. They would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback. The study is funded by the Research Council of Norway (Grant 300823/H40) as a part of the study development of a care pathway for patients with hand osteoarthritis.

Magnussen HJ, Kjeken I, Pinxsterhuis I, et al. Participation in healthcare consultations: a qualitative study from the perspectives of persons diagnosed with hand osteoarthritis. Health Expect. 2023;26:1276‐1286. 10.1111/hex.13744

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are not available due to ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hunter DJ, March L, Chew M. Osteoarthritis in 2020 and beyond: a Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10264):1711‐1712. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32230-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Safiri S, Kolahi A‐A, Smith E, et al. Global, regional and national burden of osteoarthritis 1990‐2017: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(6):819‐828. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Felson DT. Priorities for osteoarthritis research: much to be done. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(8):447‐448. 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Conaghan PG, Kloppenburg M, Schett G, Bijlsma JWJ. Osteoarthritis research priorities: a report from a EULAR ad hoc expert committee. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(8):1442‐1445. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kloppenburg M, Kroon FP, Blanco FJ, et al. 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(1):16‐24. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kloppenburg M, Kwok W‐Y. Hand osteoarthritis—a heterogeneous disorder. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8(1):22‐31. 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dziedzic K, Thomas E, Hill S, Wilkie R, Peat G, Croft PR. The impact of musculoskeletal hand problems in older adults: findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Rheumatology. 2007;46(6):963‐967. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gravås EMH, Tveter AT, Nossum R, et al. Non‐pharmacological treatment gap preceding surgical consultation in thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis—a cross‐sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):180. 10.1186/s12891-019-2567-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Conaghan PG, Porcheret M, Kingsbury SR, et al. Impact and therapy of osteoarthritis: the Arthritis Care OA Nation 2012 survey. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(9):1581‐1588. 10.1007/s10067-014-2692-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hill S, Dziedzic K, Thomas E, Baker SR, Croft P. The illness perceptions associated with health and behavioural outcomes in people with musculoskeletal hand problems: findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Rheumatology. 2007;46(6):944‐951. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grime J, Richardson JC, Ong BN. Perceptions of joint pain and feeling well in older people who reported being healthy: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(577):597‐603. 10.3399/bjgp10X515106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sanders C, Donovan J, Dieppe P. The significance and consequences of having painful and disabled joints in older age: co‐existing accounts of normal and disrupted biographies. Sociol Health Illn. 2002;24(2):227‐253. 10.1111/1467-9566.00292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coxon D, Frisher M, Jinks C, Jordan K, Paskins Z, Peat G. The relative importance of perceived doctor's attitude on the decision to consult for symptomatic osteoarthritis: a choice‐based conjoint analysis study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(10):e009625. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoon EA, Gill TK, Pham C, Gray J, Beilby J. A population analysis of self‐management and health‐related quality of life for chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Health Expect. 2017;20(1):24‐34. 10.1111/hex.12422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morden A, Jinks C, Ong BN. Understanding help seeking for chronic joint pain: implications for providing supported self‐management. Qual Health Res. 2014;24(7):957‐968. 10.1177/1049732314539853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paskins Z, Sanders T, Croft PR, Hassell AB. The identity crisis of osteoarthritis in general practice: a qualitative study using video‐stimulated recall. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(6):537‐544. 10.1370/afm.1866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bukhave EB, Huniche L. Activity problems in everyday life—patients' perspectives of hand osteoarthritis: “try imagining what it would be like having no hands”. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(19):1636‐1643. 10.3109/09638288.2013.863390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hill S, Dziedzic KS, Nio Ong B. Patients' perceptions of the treatment and management of hand osteoarthritis: a focus group enquiry. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(19‐20):1866‐1872. 10.3109/09638288.2010.550381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vitaloni M, Botto‐van Bemden A, Sciortino R, et al. A patients' view of OA: the Global Osteoarthritis Patient Perception Survey (GOAPPS), a pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):727. 10.1186/s12891-020-03741-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alami S, Boutron I, Desjeux D, et al. Patients' and practitioners' views of knee osteoarthritis and its management: a qualitative interview study. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19634. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morden A, Ong BN, Jinks C, Healey E, Finney A, Dziedzic KS. Resistance or appropriation?: uptake of exercise after a nurse‐led intervention to promote self‐management for osteoarthritis. Health. 2022;26(2):221‐243. 10.1177/1363459320925879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision‐making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681‐692. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00221-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goffman E. Encounters: Two Studies in the Sociology of Interaction (Advanced studies in sociology). Vol. 1. Bobbs‐Merrill; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Strauss AL. Negotiations: Varieties, Contexts, Processes, and Social Order. Jossey‐Bass; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lukes S. Power: A Radical View (Studies in sociology). Macmillan; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grimen H. Power, trust, and risk. Med Anthropol Q. 2009;23(1):16‐33. 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2009.01035.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Armstrong D. Actors, patients and agency: a recent history. Sociol Health Illn. 2014;36(2):163‐174. 10.1111/1467-9566.12100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Greenhalgh T. Patient and public involvement in chronic illness: beyond the expert patient. BMJ. 2009;338(7695):b49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Malterud K, Elvbakken KT. Patients participating as co‐researchers in health research: A systematic review of outcomes and experiences. Scand J Public Health. 2019;48:617‐628. 10.1177/1403494819863514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mik‐Meyer N. The Power of Citizens and Professionals in Welfare Encounters: The Influence of Bureaucracy, Market and Psychology (Social and political power). Manchester University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eisenhardt KM. Building theories from case study research. Acad Managemen Rev. 1989;14(4):532‐550. 10.2307/258557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang W, Doherty M, Leeb BF, et al. EULAR evidence‐based recommendations for the diagnosis of hand osteoarthritis: report of a task force of ESCISIT. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(1):8‐17. 10.1136/ard.2007.084772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Qin J, Barbour KE, Murphy LB, et al. Lifetime risk of symptomatic hand osteoarthritis: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Rheum. 2017;69(6):1204‐1212. 10.1002/art.40097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kjeken I, Bergsmark K, Haugen IK, et al. Task shifting in the care for patients with hand osteoarthritis. Protocol for a randomized controlled non‐inferiority trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):194. 10.1186/s12891-021-04019-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Holstein JA, Gubrium JF. Handbook of Constructionist Research. Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753‐1760. 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18(3):328‐352. 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77‐101. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tavory I. Abductive Analysis: Theorizing Qualitative Research. University of Chicago Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Earl Rinehart K. Abductive analysis in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Inq. 2021;27(2):303‐311. 10.1177/1077800420935912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Braun V, Clarke V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Int J Transgender Health. 2022;24:1‐6. 10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Braun V, Clarke V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual Psychol. 2022;9(1):3‐26. 10.1037/qup0000196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jinks C, Ong BN, Richardson J. A mixed methods study to investigate needs assessment for knee pain and disability: population and individual perspectives. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8(1):59. 10.1186/1471-2474-8-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gignac MAM, Davis AM, Hawker G, et al. “What do you expect? You're just getting older”: a comparison of perceived osteoarthritis‐related and aging‐related health experiences in middle‐ and older‐age adults. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(6):905‐912. 10.1002/art.22338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Grenier A. Transitions and the Lifecourse: Challenging the Constructions of ‘Growing Old’. Policy Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Henselmans I, Heijmans M, Rademakers J, van Dulmen S. Participation of chronic patients in medical consultations: patients’ perceived efficacy, barriers and interest in support. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):2375‐2388. 10.1111/hex.12206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services . Prioritisation principles for municipal health and care services and publicly funded dental health services (NOU 2018:16); 2018.

- 49. Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services . Principles for priority setting in health care—summary of a white paper on priority setting in the Norwegian health care sector (Meld. St. 34 (2015–2016)); 2016.

- 50. Album D, Westin S. Do diseases have a prestige hierarchy? A survey among physicians and medical students. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(1):182‐188. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Johnson T. Professions and Power. Macmillan; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Henwood F, Wyatt S, Hart A, Smith J. “Ignorance is bliss sometimes”: constraints on the emergence of the informed patient in the changing landscapes of health information. Sociol Health Illness. 2003;25(6):589‐607. 10.1111/1467-9566.00360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kraetschmer N, Sharpe N, Urowitz S, Deber RB. How does trust affect patient preferences for participation in decision‐making? Health Expect. 2004;7(4):317‐326. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00296.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Barry CA. Patients' unvoiced agendas in general practice consultations: qualitative study. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1246‐1250. 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Grime JC, Ong BN. Constructing osteoarthritis through discourse‐a qualitative analysis of six patient information leaflets on osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8(1):34. 10.1186/1471-2474-8-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Porcheret M, Grime J, Main C, Dziedzic K. Developing a model osteoarthritis consultation: a Delphi consensus exercise. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14(1):25. 10.1186/1471-2474-14-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Feddersen H, Kristiansen TM, Andersen PT, Hørslev‐Petersen K, Primdahl J. Interactions between women with rheumatoid arthritis and nurses during outpatient consultations: a qualitative study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2019;17(4):363‐371. 10.1002/msc.1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lian OS, Nettleton S, Wifstad Å, Dowrick C. Modes of interaction in naturally occurring medical encounters with general practitioners: the “One in a Million” study. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(6):1129‐1143. 10.1177/1049732321993790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Meyer S, Ward P, Coveney J, Rogers W. Trust in the health system: an analysis and extension of the social theories of Giddens and Luhmann. Health Sociol Rev. 2008;17(2):177‐186. 10.5172/hesr.451.17.2.177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mechanic D. The functions and limitations of trust in the provision of medical care. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1998;23(4):661‐686. 10.1215/03616878-23-4-661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bodenheimer T. Patient self‐management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2469‐2475. 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dures E, Hewlett S, Ambler N, Jenkins R, Clarke J, Gooberman‐Hill R. A qualitative study of patients' perspectives on collaboration to support self‐management in routine rheumatology consultations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:129. 10.1186/s12891-016-0984-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. McBain H, Shipley M, Newman S. Clinician and patient views about self‐management support in arthritis: a cross‐sectional UK survey. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70(11):1607‐1613. 10.1002/acr.23540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Oppong R, Jowett S, Lewis M, et al. Cost‐effectiveness of a model consultation to support self‐management in patients with osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2018;57(6):1056‐1063. 10.1093/rheumatology/key037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Boyers D, McNamee P, Clarke A, et al. Cost‐effectiveness of self‐management methods for the treatment of chronic pain in an aging adult population: a systematic review of the literature. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(4):366‐375. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318250f539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ayo N. Understanding health promotion in a neoliberal climate and the making of health conscious citizens. Crit Public Health. 2012;22(1):99‐105. 10.1080/09581596.2010.520692 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lupton D. Medicine as Culture: Illness, Disease and the Body. 3rd ed. Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gustafsson K, Kvist J, Eriksson M, Dahlberg LE, Rolfson O. Socioeconomic status of patients in a Swedish national self‐management program for osteoarthritis compared with the general population—a descriptive observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):10. 10.1186/s12891-019-3016-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not available due to ethical restrictions.