Abstract

Although the gross and microscopic features of squamous cell carcinoma arising from ovarian mature cystic teratoma (MCT‐SCC) vary from case to case, the spatial spreading of genomic alterations within the tumor remains unclear. To clarify the spatial genomic diversity in MCT‐SCCs, we performed whole‐exome sequencing by collecting 16 samples from histologically different parts of two MCT‐SCCs. Both cases showed histological diversity within the tumors (case 1: nonkeratinizing and keratinizing SCC and case 2: nonkeratinizing SCC and anaplastic carcinoma) and had different somatic mutation profiles by histological findings. Mutation signature analysis revealed a significantly enriched apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme catalytic subunit (APOBEC) signature at all sites. Intriguingly, the spread of genomic alterations within the tumor and the clonal evolution patterns from nonmalignant epithelium to cancer sites differed between cases. TP53 mutation and copy number alterations were widespread at all sites, including the nonmalignant epithelium, in case 1. Keratinizing and nonkeratinizing SCCs were differentiated by the occurrence of unique somatic mutations from a common ancestral clone. In contrast, the nonmalignant epithelium showed almost no somatic mutations in case 2. TP53 mutation and the copy number alteration similarities were observed only in nonkeratinizing SCC samples. Nonkeratinizing SCC and anaplastic carcinoma shared almost no somatic mutations, suggesting that each locally and independently arose in the MCT. We demonstrated that two MCT‐SCCs with different histologic findings were highly heterogeneous tumors with clearly different clones associated with APOBEC‐mediated mutagenesis, suggesting the importance of evaluating intratumor histological and genetic heterogeneity among multiple sites of MCT‐SCC.

Keywords: APOBEC, genomic diversity, malignant transformation, mature cystic teratoma, squamous cell carcinoma

We demonstrated that two squamous cell carcinomas arising from mature cystic teratoma of the ovary with different histologic findings were highly heterogeneous tumors with clearly different clones associated with APOBEC‐mediated mutagenesis, suggesting the importance of evaluating intratumor histological and genetic heterogeneity among multiple sites of this tumor.

Abbreviations

- APOBEC

apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme catalytic subunit

- BAM

binary alignment map

- FF

fresh‐frozen

- FFPE

formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded

- HPD

highest posterior density

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- Indels

short insertions/deletions

- LOH

loss of heterozygosity

- MAF

mutant allele frequency

- MCT

mature cystic teratoma

- MCT‐SCC

squamous cell carcinoma arising from ovarian mature cystic teratoma

- PD‐L1

programmed cell death ligand 1

- SBS

single‐base substitution

- SCC

squamous cell carcinomas

- SNVs

somatic single‐nucleotide variants

1. INTRODUCTION

Mature cystic teratoma (MCT) is the most common ovarian germ cell tumor, accounting for 10%‐20% of all ovarian tumors. Malignant transformation occurs in very rare cases, about 0.17%‐2% of MCTs, of which approximately 80% are squamous cell carcinomas (SCC). 1 , 2 Squamous cell carcinoma arising from ovarian mature cystic teratoma (MCT‐SCC) has been characterized by difficulty of preoperative diagnosis, especially in the early stage. It is often diagnosed unexpectedly based on postoperative pathological examination. 3 Because of its rarity, the standard treatment for MCT‐SCC has not been established. Furthermore, approximately 50% of MCT‐SCC are stage II‐IV cases with extraovarian extension, and the prognosis of these cases is poor because of treatment resistance. 1 , 2 , 4 Therefore, it is particularly important to detect the potential for malignant transformation early and develop novel therapies for advanced cases.

The molecular mechanisms of malignant transformation and treatment resistance in MCT‐SCC were not elucidated although several comprehensive genomic, transcriptomic, and miRNA analyses were performed in a small number of cases. 4 , 5 , 6 We previously performed an integrated omics analysis of MCT‐SCC and revealed a specifically high frequency of TP53 and PIK3CA mutations. 4 Our previous study analyzed a cancer site of the primary tumor and the spatial spreading of gene alterations within the primary or metastatic tumor remains unclear although TP53 and PIK3CA mutations may play a crucial role in MCT‐SCC development. The gross and microscopic features of MCT‐SCC vary from case to case, and the malignant component may overgrow the remaining part of MCT and cause diagnostic difficulties. 7 Moreover, various histologic types of malignant tumors arise from MCT, including adenocarcinoma, carcinoid tumor, thyroid carcinoma, sarcoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, and melanoma. 8 Furthermore, several studies reported on different cancer components that coexist within the tumor. 9 , 10 , 11 These findings suggest that carcinomas arising from MCT may be a specifically highly heterogeneous tumor. Intratumor heterogeneity was observed in many tumors in cross‐sectional carcinoma studies and implicated in tumor evolution, therapeutic resistance, and genomic instability. 12 , 13 Cooke et al performed targeted sequencing of 151 cancer‐associated genes in 25 cases, of which five were evaluated at two or more cancer sites. They reported some shared or different somatic mutations, 5 but no previous comprehensive molecular analysis has focused on intratumor genomic heterogeneity in MCT‐SCC.

Thus, this study collected 16 samples (nine fresh‐frozen [FF] samples and seven formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded [FFPE] samples) from histologically different parts of two advanced MCT‐SCCs and performed whole‐exome sequencing. We demonstrated the spatial genomic diversity and the clonal evolution pattern from nonmalignant epithelium to cancer sites in two MCT‐SCCs by evaluating somatic mutation profiles, copy number alterations, and mutation signatures at multiple sites, thereby elucidating the mechanisms of malignant transformation and treatment resistance in MCT‐SCC.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients and samples

Both patients had advanced MCT‐SCC and underwent primary debulking surgery. We collected surgical samples from multiple sites within the primary and disseminated tumor.

2.2. DNA extraction from FF samples

We extracted DNA from FF samples and blood samples as previously described. 14 Tumor DNA extraction was performed with the Tissue Genomic DNA Extraction Mini Kit (Favorgen) and blood DNA was extracted with the QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions. Genomic DNA was quantified using a Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.3. DNA extraction from FFPE samples

DNA was collected from FFPE samples using laser microdissection to evaluate specimens from sites where FF samples could not be collected and for a more detailed evaluation of differences in each histological type. Laser microdissection was performed as described in our previous study. 15 DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA micro kit (Qiagen).

2.4. Whole‐exome sequencing and analysis

Whole‐exome sequencing was performed as described in our previous study. 16 Briefly, DNA samples were fragmented using a NEBNext dsDNA Fragmentase (New England Biolabs). DNA collected from FFPE samples was repaired with a NEBNext FFPE DNA Repair Mix (New England Biolabs). Sequencing libraries were constructed with a NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs). Target gene enrichment was conducted with an IDT xGen Exome Research Panel v2 (Integrated DNA Technologies). The libraries were sequenced via an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with a 2 × 150 bp paired‐end module (Illumina). The Illumina adapter sequences were trimmed using TrimGalore (version 0.6.3) (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/) as a quality control step. Low‐quality sequences were excluded or trimmed with Trimmomatic (version 0.39). 17 The filtered sequence reads were aligned with the human reference genome (GRCh38) containing sequence decoys and virus sequences generated by the Genomic Data Commons of the National Cancer Institute using BWA‐MEM (version 0.7.17). 18 , 19 The sequence alignment map files were sorted and converted to the binary alignment map (BAM) file format with SAMtools (version 1.9). 20 The BAM files were processed using Picard tools (version 2.20.6) (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) to remove polymerase chain reaction duplicates. Base quality recalibration was conducted using GATK (version 4.1.3.0). 21 , 22 The average depths and the coverages of the target regions were calculated with SAMtools. 20 BEDOPS (version 2.4.36) 23 and BEDTools (v2.28.0) 24 were used in the handling of FASTA, VCF, and BED files. The average depths and the coverages of the target regions in all samples are shown in Table S1.

2.5. Variant detection and mutation annotation

Variant detection and mutation annotation were performed as described in our previous study. 16 Somatic single‐nucleotide variants (SNVs) and short insertions/deletions (Indels) in coding exons and splice sites were called using Strelka2 (version2.9.10). 25 We utilized the information about candidate Indel sites provided by Manta (version 1.6.0) for somatic Indel calling. 26 Empirical variant scores provided by Strelka2 of >13.0103 (= −10 × log10 0.05) were used for subsequent analyses. Additionally, variants whose frequencies were ≥0.001 in any of the general populations from the 1000 Genomes Project; 27 the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute GO Exome Sequencing Project; 28 and the Genome Aggregation Database 29 were excluded to avoid false‐positive variant calls. Functional annotations for protein coding and transcription‐related effects of the identified variants were implemented by Ensembl VEP. 30 Curated information about cancer‐associated genes and their functional roles in cancer development was retrieved from the COSMIC database. 31

The following criteria were used to identify somatic variants with high confidence in FF samples and an FFPE sample (disseminated tumor in the fallopian mesentery [D] in case 1): (i) the sequencing depth of ≥20; (ii) the number of reads that supported the mutant allele in a tumor sample of ≥8; (iii) the mutant allele frequency (MAF) in the matched blood sample of not >0.05; and (iv) the number of reads supporting the mutant allele in the matched blood sample of <2. We compiled MAF profiles for the mutation sites identified in FF samples and a FFPE sample (disseminated tumor in the fallopian mesentery [D] in case 1) for the other six FFPE samples with low‐quality DNA by counting the sequence reads supporting the reference and mutant alleles with SAMtools mpileup. 20 This analysis used the reads mapped with high confidence (mapping quality of >30). Then, the allele‐specific counts were measured using only high‐confidence base calls (base quality of >20) at the mutation sites.

2.6. Detection of somatic copy number alterations

Somatic copy number alterations were sought using FACETS based on the information about the total sequence read count and allelic imbalance in tumor or nonmalignant epithelium samples and the matched blood samples. 32 Germline polymorphic sites were retrieved from the VCF file generated by the 1000 Genomes Project. 27 The ploidy and purity were estimated using FACETS. 32 The calculated ploidy and purity in all samples are shown in Table S2. The disseminated tumor in case 2 was excluded from the copy number analysis because of the low purity. Genome‐wide profiles of somatic copy number alteration and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in all samples are shown in Table S3.

2.7. Detection of mutation signatures

The mutation signature was detected as described in our previous study. 16 We used the identified somatic SNVs with high confidence in FF samples and an FFPE sample (disseminated tumor in the fallopian mesentery [D] in case 1) for mutational signature analysis. The samples were separately analyzed for histological types in each patient to detect mutational signatures that were active in each histological type. The somatic SNVs were classified into 96 mutation classes defined by the six pyrimidine substitutions (C>A, C>G, C>T, T>A, T>C, and T>G) in combination with the flanking 5′ and 3′ bases. The 96‐mutation catalog was fitted to a predefined list of known signatures for our mutational signature analysis. 33 , 34 We did not select an approach for de novo signature extraction because the number of somatic mutations was not large enough in this study. We used the COSMIC mutational signatures version 3 as a reference set of known mutational signatures. 35 We selected a total of six single‐base substitution (SBS) signatures (SBS1, SBS2, SBS5, SBS13, SBS18, and SBS40) with activities in SCC from various sites based on a previous study. 35 We implemented a fitting approach using sigfit. 36 We ran four Markov chains with a total of 50,000 iterations, including a burn‐in of 25,000 samples. We estimated the highest posterior density (HPD) interval for each of the SBS signatures. We considered the SBS signature as a significantly active signature if the 90% lower end of the HPD interval for an SBS signature was above the threshold (0.01, default value). The frequency of somatic SNVs in the respective type of trinucleotide context is presented in Table S4, and the data used to generate a bar plot for the contributions of mutational signatures is shown in Table S5.

2.8. Human papillomavirus (HPV) genotyping

For nine frozen samples from multiple sites in two cases, HPV‐DNA testing targeting 16 high‐ and low‐risk HPV genotypes (genotypes 6, 11, 16, 18, 30, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 66) was performed using the multiplex PCR method (PapiPlex) at the GLab Pathology Center Co., Ltd. 37

2.9. Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemical staining of FFPE samples was performed as described in our previous study. 38 Briefly, after deparaffinization, antigen retrieval was carried out with Target Retrieval Solution (10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0; Dako) in a microwave for 30 minutes at 96°C. Subsequently, the sections were incubated overnight with primary antibody (Cat#7001; RRID:AB_2206626, Dako; dilution ratio 1:50) at 4°C and biotinylated anti‐mouse secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories) were added, followed by incubation with ABC reagent (Dako) and 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine (Sigma). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. p53 overexpression pattern was defined as strong and diffuse nuclear expression in at least 60% of tumor cells. 39 FF samples were used for nonkeratinizing SCC in case 2 because FFPE samples were unavailable. For FF samples, we fixed frozen tissue sections with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 20 minutes followed by methanol at −20°C for 10 minutes. The immunohistochemical staining protocol after fixation was the same as the protocol for FFPE tissue sections. 40

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sharing of somatic mutations and copy number alterations at multiple sites in case 1

Case 1 was a 57‐year‐old patient with clinical stage IIB (pT2bNXM0) MCT‐SCC. The right ovarian tumor measured 15 cm and had ruptured, and the ascitic fluid cytology was positive. The disseminated tumors of 3 cm in the right fallopian mesentery and 2 cm in the peritoneum of the Douglas pouch were observed. The primary right ovarian tumor contained polypoid lesions (predominantly keratinizing SCC) and an invasively spreading lesion (predominantly nonkeratinizing SCC). The histology of the disseminated tumors was nonkeratinizing SCC. She was diagnosed with malignant transformation of MCT because of the presence of hair and fatty components in the primary tumor. FF samples of the nonmalignant epithelium away from the cancer site (N), two polypoid lesions (P1 and P2), the invasively spreading lesion (IS), and an FFPE sample of disseminated tumor in the fallopian mesentery (D) were analyzed (Figure 1). The average sequencing depth in five samples was 227 (range: 117‐275). The average percentage of the target region that covered at least 20 reads was 97.5% (range: 97.0%‐97.7%). A total of 864 SNVs and nine Indels were detected in five samples (Table S6).

FIGURE 1.

Gross and microscopic findings of tissue sampling sites in case 1. A, The gross findings of nonmalignant epithelium away from the cancer site (N), two polypoid lesions (P1, P2), the invasively spreading lesion (IS), and disseminated tumor in the fallopian mesentery (D) in case 1 are shown. B, Microscopic findings of each sample are shown (200× magnification; scale bar, 100 μm)

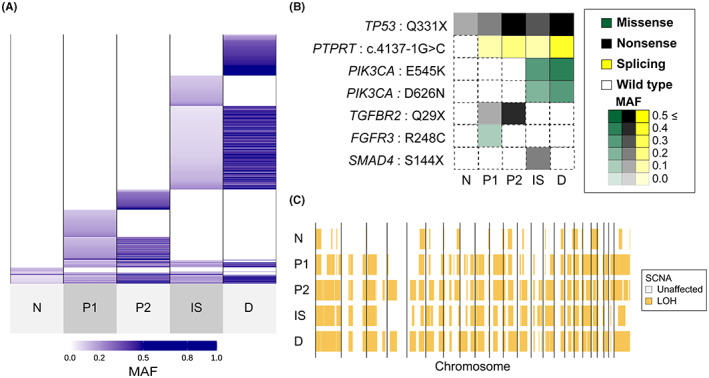

First, we evaluated the somatic mutations shared by each site. A part of the mutations was shared by all samples, including nonmalignant epithelium. Somatic mutations were almost shared by histological types. The somatic mutation profiles of keratinizing SCC (P1 and P2) and nonkeratinizing SCC (IS and D) were different. The samples with the same histology shared many mutations, and each sample had additional unique mutations (Figure 2A, Table S7). Representative shared cancer‐associated gene mutations are shown in Figure 2B. TP53 (Q331X) was shared by all samples, including nonmalignant epithelium; PTPRT (c.4137‐1G>C) was shared except for nonmalignant epithelium; PIK3CA mutations (E545K and D626N) only in nonkeratinizing SCCs (IS and D); TGFBR2 (Q29X) only in the keratinizing SCCs (P1 and P2); and FGFR3 (R248C) and SMAD4 (S144X) in only one sample each with the same histology (P1 and IS, respectively) (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Sharing pattern of genomic alterations in case 1. A, Sharing pattern of somatic single‐nucleotide variants (SNVs) and short insertions/deletions (Indels) among five tissues. Color density indicates the mutant allele frequency (MAF) of each somatic mutation. B, Heatmaps demonstrate the representative oncogenic alterations in case 1. Color and density indicate the type and MAF of each somatic mutation, respectively. C, Genome‐wide profiles of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in the five samples. Vertical lines correspond to chromosome numbers

Then, we performed immunohistochemical staining using FFPE samples to evaluate p53 protein expression and its expression sites in the tumor and confirmed that p53 protein expression was observed widely in the epithelial components of the tumor including the nonmalignant epithelium distant from the cancer site, but not in stromal components (Figure S1).

Genome‐wide copy number alterations were detected in all samples (Figure S2A). The evaluation of copy number change relative to ploidy confirmed that the pattern of segments with copy number change was similar in all samples (Figure S2B). Furthermore, the LOH analysis more clearly confirmed that the segmental changes occurring in the nonmalignant epithelium were shared by all samples. The genome‐wide profiles of LOH were strongly similar in four cancer samples (P1, P2, IS, and D) (Figure 2C).

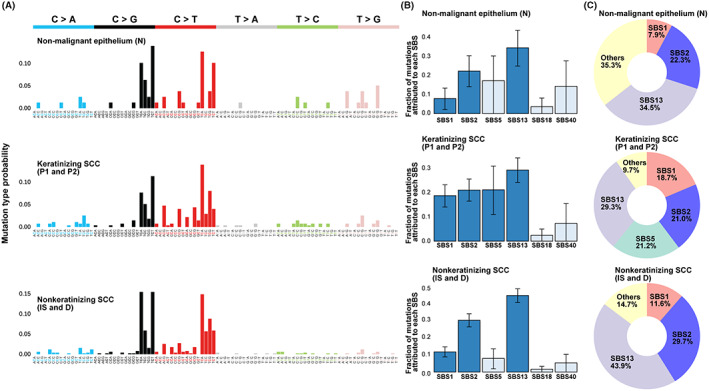

Mutation spectrum analysis showed a high number of C>T or C>G mutations in the TCA and TCT contexts in all histological types (nonmalignant epithelium, keratinizing SCC, and nonkeratinizing SCC), suggesting the involvement of apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme catalytic subunit (APOBEC) signature (Figure 3A). When we estimated the contributions of the six SCC‐associated SBSs based on the COSMIC mutational signatures, 35 APOBEC signature (SBS2 and SBS13) was significantly enriched in all histological types. Of the total gene mutations, 56.8% were associated with APOBEC signature in the nonmalignant epithelium, 50.3% in keratinizing SCCs, and 73.6% in nonkeratinizing SCCs. Associations with clock‐like signatures (SBS1 and/or SBS5) were also observed in all histological types (Figure 3B,C).

FIGURE 3.

Mutational spectrum and signatures in case 1. A, High‐resolution mutational spectrum of differential histological type (nonmalignant epithelium, keratinizing SCC, and nonkeratinizing SCC) in case 1. Each of the six possible point mutations is subdivided into 16 subclasses based on the nucleotides on both mutation sides. B, Bar chart representing the results of Bayesian inference using sigfit to determine the contribution of the COSMIC mutational signatures to somatic SNVs with high mutant allele frequency (MAF). Data are presented as the estimated contributions of significant mutational signatures and the lower and upper limits of the 90% highest posterior density interval. Signatures that were significantly involved are presented in dark blue. Source data are provided in Table S3. C, The inset is a doughnut chart summarizing the contributions of six significant mutational signatures (SBS1, SBS2, SBS5, SBS13, SBS18, and SBS40)

To investigate the cause of the high proportion of APOBEC signatures, we focused on the status of HPV infection. 41 We evaluated HPV status at multiple sites (N, P1, P2 and IS) and found no HPV‐positive sites.

3.2. Assessment of shared somatic mutations at multiple sites in keratinizing and nonkeratinizing SCCs

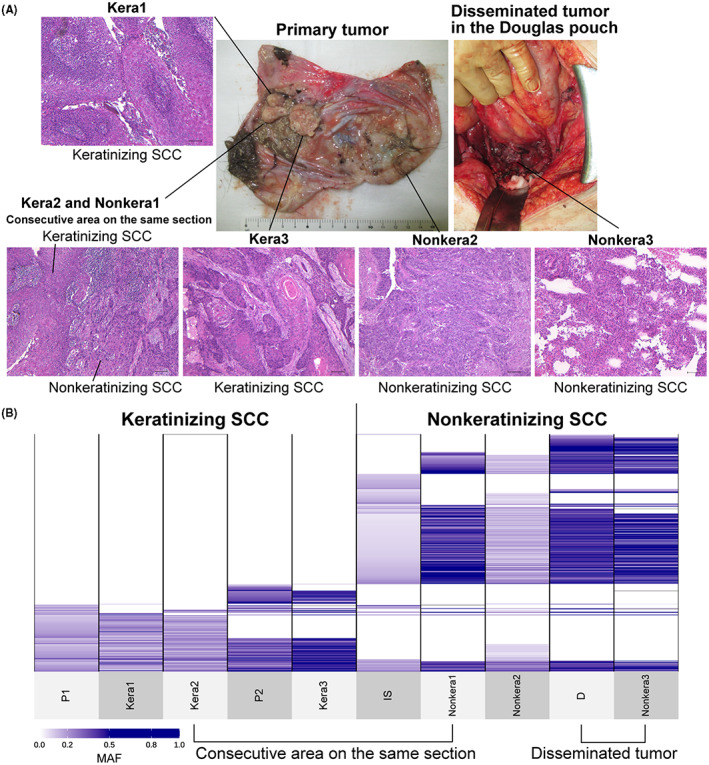

To further evaluate the differences between keratinizing and nonkeratinizing SCCs in case 1, DNA samples were additionally collected from multiple sites using laser microdissection and subjected to whole‐exome sequencing. The keratinizing SCC in the polypoid lesion next to P1 (Kera1), the area around P1 where keratinizing and nonkeratinizing SCCs were contiguous on the same section (Kera2 and Nonkera1), and the area in the same polypoid lesion as P2 where keratinizing SCC (Kera3) within the same polypoid lesion as P2 were analyzed. We also analyzed the disseminated tumor in the Douglas pouch (Figure 4A). To assess the clonal relationship among keratinizing and nonkeratinizing SCC, we constructed mutation profiles for the mutations detected in the four cancer samples (N, P1, P2, IS, and D; Figure 2A).

FIGURE 4.

Sharing of somatic mutation profiles defined by multiregional sequencing of keratinizing and nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) in primary and disseminated tumors. A, Gross findings of the sample collection sites of the primary and disseminated tumors in the Douglas pouch are shown, as well as the microscopic findings of each sample (100× magnification; scale bar, 100 μm). Kera2 and Nonkera1 were in the consecutive area on the same section. B, Sharing pattern of somatic single‐nucleotide variants (SNVs) and short insertions/deletions (Indels) among 10 samples, including five samples in Figure 2. The multiregional analysis in Figure 4 was limited to the mutation sites identified in Figure 2 because formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded (FFPE) samples included low‐depth samples. All shared somatic SNVs and Indels and MAF are shown in Table S8

Consistent with the results in bulk tumors (Figure 2), keratinizing and nonkeratinizing SCC samples differently shared many somatic mutations across sites within the tumor according to histological types. Kera2 and Nonkera1, which were contiguous regions in the same section (Figures 4A, S3), showed different somatic mutation profiles, strongly suggesting different clonal origins by histological types. At the same time, site‐specific mutations were observed in both histological types. Two polypoid lesions (P1, Kera1, Kera2, P2, and Kera3) shared the same somatic mutations indicating the same clonal origin. Then, the polypoid lesions on the left side (P1, Kera1, and Kera2) and the right side (P2 and Kera3) diversified by acquiring distinct somatic mutations. IS and Nonkera1, which were nonkeratinizing SCCs from different sites within the primary tumor, had a substantial number of shared and unique mutations, suggesting their common clonal origin and subsequent diversification. Nonkera2 had a similar mutation profile with Nonkera1, but also shared some of the mutations unique to IS. Furthermore, Nonkera2 shared some mutations common to keratinizing SCCs, suggesting that keratinizing and nonkeratinizing SCC clones were intermixing in some regions. Disseminated tumors (D and Nonkera3) showed similar mutation profiles with the nonkeratinizing SCCs within the primary tumor (IS, Nonkera1, and Nonkera2) and acquired different mutations that were shared between these disseminated tumors (Figure 4B, Table S8), suggesting both of the disseminated tumors were derived from the common ancestral clone of nonkeratinizing SCC.

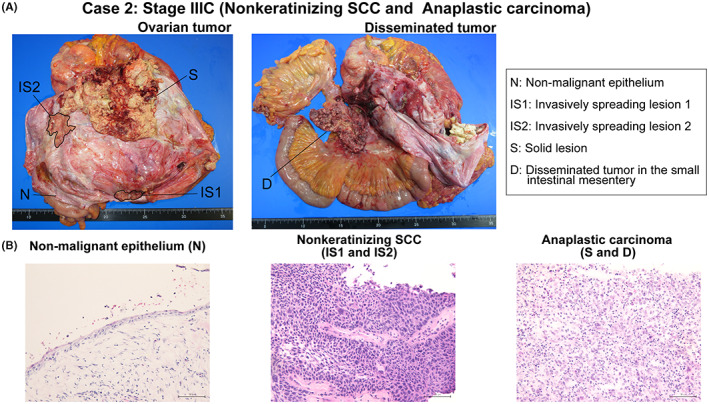

3.3. Sharing of somatic mutations and copy number alterations at multiple sites in case 2

Case 2 was a 70‐year‐old patient with stage IIIC (pT3cNXM0) MCT‐SCC. The right ovarian tumor measured 19 cm and had not ruptured, and the ascitic fluid cytology was negative. A disseminated tumor measuring 5 cm in size was observed in the small intestinal mesentery, and no other disseminated tumors were observed. The primary right ovarian tumor contained a large solid lesion (anaplastic carcinoma) and an IS lesion (nonkeratinizing SCC). The majority of the malignancies were large solid lesions with scattered IS lesions, which were not contiguous. The histology of the disseminated tumor was anaplastic carcinoma. She was diagnosed with malignant transformation of MCT because of the presence of respiratory epithelial, hair components, grossly visible odontoblasts, and bone components.

Then, FF samples of the nonmalignant epithelium away from the tumor site (N), the invasively spreading lesion (IS1 and IS2), the solid lesion in tumor (S), and the disseminated tumor in the small intestinal mesentery (D) were collected (Figure 5). The average sequencing depth in five samples was 156 (range: 128‐177). The average percentage of the target region that covered at least 20 reads was 97.5% (range: 97.4%‐97.5%). A total of 852 SNVs and six Indels were detected (Table S9).

FIGURE 5.

Gross and microscopic findings of tissue sampling sites in case 2. A, The gross findings of the nonmalignant epithelium away from the cancer site (N), two invasively spreading lesions (IS1 and IS2), the solid lesion (S), and disseminated tumor in the small intestinal mesentery (D) in case 2 are shown. The spread of IS1 and IS2 is traced in black. B, Microscopic findings of each sample are shown (200× magnification; scale bar, 100 μm)

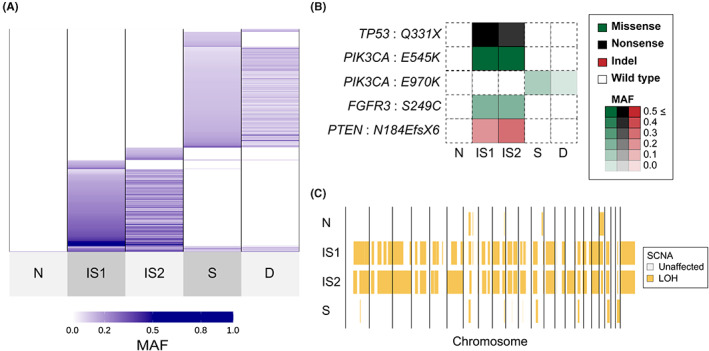

We evaluated the somatic mutations shared by each site. Similar to case 1, the samples with the same histology shared many mutations, and each sample had additional unique mutations. Nonmalignant epithelium distant from the tumor (N) had almost no mutations in case 2, unlike case 1. Nonkeratinizing SCC (IS1 and IS2) and anaplastic carcinomas (S and D) have different mutation profiles, with almost no shared mutations (Figure 6A, Table S10). TP53 (Q331X), FGFR3 (S249C), and PTEN (N184EfsX6) were identified only in nonkeratinizing SCCs. PIK3CA showed pathological mutations in all samples; however, PIK3CA mutation sites differed among the histological types (nonkeratinizing SCC: E545K, anaplastic carcinoma: E970K). No obvious driver mutations, other than PIK3CA mutation, could be identified in anaplastic carcinomas (Figure 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Sharing pattern of genomic alterations in case 2. A, Sharing pattern of somatic single‐nucleotide variants (SNVs) and short insertions/deletions (Indels) among five tissues. Color density indicates the mutant allele frequency (MAF) of each somatic mutation. B, Heatmaps demonstrate the representative oncogenic alterations in case 2. Color and density indicate the type and MAF of each somatic mutation, respectively. C, Genome‐wide profiles of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in the four samples. Vertical lines correspond to chromosome numbers. The disseminated tumor in the small intestinal mesentery (D) was excluded from the copy number analysis because of the low purity (Table S2)

Then, we performed immunohistochemical staining using FFPE and FF samples to evaluate p53 protein expression and confirmed that p53 protein overexpression was observed only in nonkeratinizing SCC with TP53 mutation but not in anaplastic carcinoma and nonmalignant epithelium without TP53 mutation (Figure S4).

Copy number variation analysis showed little copy number variation in the nonmalignant epithelium, while the other three samples showed genome‐wide copy number variation (Figure 5A,B). LOH analysis showed that two nonkeratinizing SCC samples (IS1 and IS2) were similar to each other but different from anaplastic carcinoma (S) (Figure 6C).

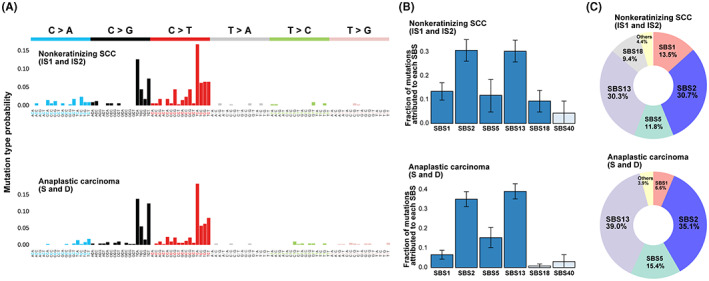

Mutation spectrum analysis showed a high number of C>T or C>G mutations in the TCA and TCT contexts in all specimens in both histological types (nonkeratinizing SCC and anaplastic carcinoma) (Figure 7A). APOBEC (SBS2 and SBS13) and clock‐like signature mutations (SBS1 and SBS5) were significantly enriched in both histological types in case 2, similar to case 1. In particular, 61.0% of all somatic mutations were APOBEC‐mediated mutations in nonkeratinizing SCC and 74.1% in anaplastic carcinomas (Figure 7B,C). As in case 1, we evaluated HPV status at multiple sites (N, IS1, IS2, S, and D) and found no HPV‐positive sites.

FIGURE 7.

Mutational spectrum and signatures in case 2. A, High‐resolution mutational spectrum of differential histological type (nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinomas [SCC] and anaplastic carcinoma) in case 2. Nonmalignant epithelium (N) away from the tumor showed little mutation and is not shown. Each of the six possible point mutations is subdivided into 16 subclasses based on the nucleotides on both mutation sides. B, Bar chart representing the results of Bayesian inference using sigfit to determine the contribution of the COSMIC mutational signatures to somatic single‐nucleotide variants (SNVs) with high mutant allele frequency (MAF). Data are presented as the estimated contributions of significant mutational signatures and the lower and upper limits of the 90% highest posterior density interval. Significantly involved signatures are presented in dark blue. Source data are provided in Table S3. C, The inset is a doughnut chart summarizing the contributions of six significant mutational signatures (SBS1, SBS2, SBS5, SBS13, SBS18, and SBS40)

4. DISCUSSION

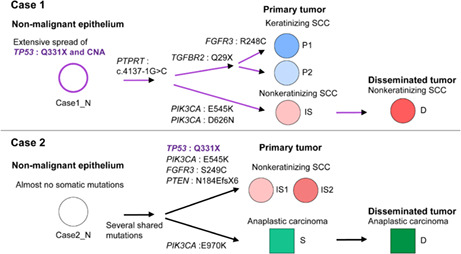

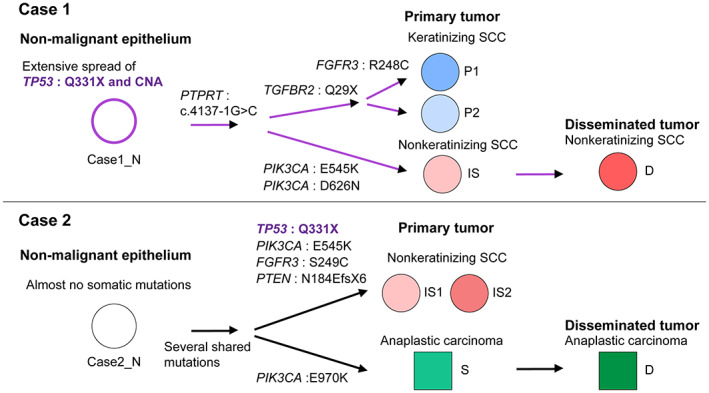

This study clarified the spatial genomic diversity in two cases of advanced MCT‐SCCs by performing a comprehensive genomic analysis of multiple sites. Figure 8 summarizes the genomic diversity and the predicted clonal evolution model of the nonmalignant epithelium, primary tumor, and disseminated tumor in the two cases. TP53 mutations and copy number alterations might be an early event in malignant transformation, but their spread within the tumor differed between cases. Most importantly, we showed that MCT‐SCCs shared many somatic mutations by histological findings within the tumor, suggesting that each histological type originated from a common ancestral clone. In addition, each sample was differentiated by the occurrence of unique somatic mutations. Both cases were advanced with abdominal peritoneal dissemination, and only clones of nonkeratinizing SCC or anaplastic carcinoma were detected in the disseminated tumor. The presence of multiple clones is a poor prognosis in many types of cancer 12 and should be stratified as targeted therapy response according to the tumor cell proportion in which the driver is identified. 42 The remarkable spatial genomic diversity in MCT‐SCC may be associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis. Our study suggests the importance of considering the presence of multiple clones with different histological findings when treating MCT‐SCC.

FIGURE 8.

Summary of spatial genomic diversity and the predicted clonal evolution model in malignant transformation and cancer progression in two squamous cell carcinomas arising from ovarian mature cystic teratoma (MCT‐SCCs). The flow chart shows the differences in histological findings and the diversity of key genomic abnormalities in the progression from nonmalignant epithelium to primary and disseminated tumors in the two MCT‐SCCs

More than half of the detected somatic mutations in each sample were associated with the APOBEC signature, suggesting APOBEC‐mediated mutagenesis is a crucial factor for malignant transformation and cancer progression in MCT‐SCC. Cytidine deaminases of the APOBEC family function as viral protection and RNA editing and may be a major cause of mutations in human cancer. 43 , 44 , 45 Alexandrov et al revealed APOBEC signatures in approximately 17% (signature 2: 14.4%, signature 13: 2.2%) of 4,938,362 mutations in 7042 cancer samples. 46 The proportion of APOBEC signatures was especially high in cervical cancer (signature 2: 74.7% and signature 13: 0%), which is strongly associated with HPV infection. 47 The frequency of APOBEC signature mutations in MCT‐SCC is as strikingly high as in cervical cancer, implying that HPV infection might be involved in APOBEC‐mediated mutagenesis in MCT‐SCC. A previous report suggested an association between MCT‐SCC and HPV infection 48 ; however, several larger studies have ruled out an association with HPV infection. 4 , 5 We confirmed that there were no HPV‐positive sites in two cases. These results suggest that the unique tumor microenvironment within MCT rather than HPV infection may activate APOBEC and induce malignant transformation at various sites.

The enriched APOBEC signature and the molecular characteristics of MCT‐SCC may be related. We have previously reported that MCT‐SCC had a specifically high frequency of TP53 and PIK3CA mutations and more than half of the cases showed high CD8 infiltration and high programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD‐L1) expression in the tumor. 4 APOBEC activity was associated with increased mutation load and TP53 mutations. 49 , 50 A link between APOBEC‐mediated cytosine deamination and PIK3CA helical domain mutations (E542K and E545K) in head and neck SCC was suggested by several reports, 51 , 52 as well as the association between APOBEC activation and PD‐L1 expression and T‐cell infiltration, which may be a biomarker to predict the immune checkpoint inhibitor response. 53 , 54 Furthermore, a pan‐cancer data analysis revealed that APOBEC‐enriched tumors have higher gene expressions associated with tumor immunity and immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy beyond primary sites. 55 Consistently, several reports revealed that immune checkpoint inhibitors were effective against MCT‐SCC. 56 , 57 , 58 Further elucidation of the relationship between genomic abnormalities and tumor immunity in MCT‐SCC may lead to novel therapeutic strategies using immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Both patients had TP53 and PIK3CA mutations, which play a crucial role in MCT‐SCC development, 4 , 5 and their spread within the tumor was different between the two cases. TP53 mutation in case 1 spread extensively within the tumor, including nonmalignant epithelium away from the cancer site, whereas TP53 mutation in case 2 was identified only in the nonkeratinizing SCC. Cooke et al reported rare TP53 mutations in benign MCT within MCT‐SCC, accounting for 1/21 (4.8%). 5 TP53 mutations are more likely to spread to localized areas within the tumor than widely within the tumor in MCT‐SCC. TP53 mutations are associated with enhanced chromosomal instability, including increased oncogene amplification and deep tumor suppressor gene deletion. 59 Consistently, copy number analysis showed similarities in genome‐wide somatic copy number alteration and LOH patterns according to the intratumor spread of TP53 mutations. Our study suggests that TP53 mutation occurred early in the malignant transformation of MCT, followed by copy number changes in both cases.

We confirmed that TP53 mutation status at each site in the two MCT‐SCCs correlated with the pattern of p53 protein expression. All parts of the two cases with TP53 nonsense mutation (Q331X) showed p53 overexpression by immunohistochemical staining. Disrupted (truncations, frameshifts, splice site mutations, and deep deletions) TP53 mutations generally cause nonsense‐mediated decay and premature cleavage of mRNA, resulting in a null pattern of p53 immunohistochemical staining. 60 , 61 However, several recent studies have reported a high frequency of p53 overexpression in tumors with TP53 nonsense mutations in the carboxyl terminus, as in the two cases in this study. 62 , 63 , 64 Although the mechanism of p53 overexpression in these cases has not been fully elucidated, it is possible that these mutations were not subject to nonsense‐medicated decay. 62 Moreover, the p53 oligomerization domain (amino acids: 325‐356) nonsense mutants could have received transcriptional feedback regulation. These mutants also may cause less activity with protein degradation machinery, both of which increase the presence of protein. 64 Our data suggest that assessing the p53 protein expression at multiple sites with different histological findings may help evaluate genomic diversity and evolution in MCT‐SCC.

The PIK3CA mutation status in cancerous areas differed by histological type. E545K was identified only in nonkeratinizing SCC in both cases, suggesting its involvement in differentiating nonkeratinizing SCC in MCT‐SCC. E542K and E545K in the helical domain are the most common hotspot gene mutations in MCT‐SCC, with a high frequency of 4/4 (100%) or 13/17 (76.5%) of all PIK3CA missense mutations in previous studies. 4 , 5 Nonkeratinizing SCCs in case 1 had D626N in addition to E545K. Mutations in multiple locations in PIK3CA were reported to be associated with the enhanced oncogene function although the biological significance of D626N is unclear. 65 , 66 Anaplastic carcinomas in case 2 had E970K, unlike the nonkeratinizing SCC. E970K is an activating kinase domain mutation that likely enhances membrane lipids similar to the canonical kinase domain mutant H1047R. 67 This study suggests the use of the spread and complexity of TP53 and PIK3CA mutations at multiple sites in MCT‐SCC to assess the genomic evolution of individual cases, as well as the presence of multiple clones.

The current study has several important limitations. Multisampling could only be performed during the surgery in only two cases because MCT‐SCC is a rare disease and preoperative diagnosis is difficult. Analysis using other previous specimens was impossible due to the poor quality of samples. Thus, prospectively collecting more cases is necessary to further clarify the intratumor heterogeneity of MCT‐SCC. The mechanism of APOBEC activation in this disease remains to be elucidated. We could not obtain any MCT or MCT‐SCC resources, such as the cancer cell line, to perform functional analysis at present. Additional analysis of cases with malignant transformation of other histologic types and MCT without malignant transformation may clarify the significance of APOBEC signature in malignant transformation of MCT.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that two MCT‐SCCs with different histologic findings were highly heterogeneous tumors with clearly different clones associated with APOBEC‐mediated mutagenesis, suggesting the importance of evaluating intratumor histological and genetic heterogeneity among multiple sites of MCT‐SCC. Further large‐scale studies focused on intratumor heterogeneity in MCT‐SCC will provide new insights into the mechanisms of malignant transformation and treatment resistance in MCT‐SCC.

Supporting information

Figure S1.

Table S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Anna Ishida, Kenji Ohyachi, Junko Kajiwara, Junko Kitayama, Yumiko Sato, and Keiko Nishikawa for their technical assistance.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI grant number JP18K16760 (Grant‐in‐Aid for Young Scientists for R.T.), JP21K16785 (Grant‐in‐Aid for Young Scientists for R.T.), the Takeda Grant for Niigata University Medical Research for R.T., the Kanzawa Grant for R.T., the Tsukada Grant for Niigata University Medical Research for R.T., the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research Grant for K.Y. and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development grant number 22ck0106694h0002 for K.Y.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol by an institutional review board: This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional ethics review boards of Niigata University (approval number G2016‐0005).

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Registry and registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: N/A.

Tamura R, Nakaoka H, Yachida N, et al. Spatial genomic diversity associated with APOBEC mutagenesis in squamous cell carcinoma arising from ovarian teratoma. Cancer Sci. 2023;114:2145‐2157. doi: 10.1111/cas.15754

Ryo Tamura and Hirofumi Nakaoka equally contributed to this work.

References

- 1. Hackethal A, Brueggmann D, Bohlmann MK, Franke FE, Tinneberg HR, Munstedt K. Squamous‐cell carcinoma in mature cystic teratoma of the ovary: systematic review and analysis of published data. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1173‐1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li C, Zhang Q, Zhang S, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma transformation in mature cystic teratoma of the ovary: a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mori Y, Nishii H, Takabe K, et al. Preoperative diagnosis of malignant transformation arising from mature cystic teratoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:338‐341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tamura R, Yoshihara K, Nakaoka H, et al. XCL1 expression correlates with CD8‐positive T cells infiltration and PD‐L1 expression in squamous cell carcinoma arising from mature cystic teratoma of the ovary. Oncogene. 2020;39:3541‐3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cooke SL, Ennis D, Evers L, et al. The driver mutational landscape of ovarian squamous cell carcinomas arising in mature cystic Teratoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:7633‐7640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoshida K, Yokoi A, Kagawa T, et al. Unique miRNA profiling of squamous cell carcinoma arising from ovarian mature teratoma: comprehensive miRNA sequence analysis of its molecular background. Carcinogenesis. 2019;40:1435‐1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kurman RJ. Blaustein's pathology of the female genital tract. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Akazawa M, Onjo S. Malignant transformation of mature cystic Teratoma: is squamous cell carcinoma different from the other types of neoplasm? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2018;28:1650‐1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Allam‐Nandyala P, Bui MM, Caracciolo JT, Hakam A. Squamous cell carcinoma and osteosarcoma arising from a dermoid cyst – a case report and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010;3:313‐318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aryal V, Maharjan R, Singh M, Marhatta A, Bajracharya A, Dhakal HP. Malignant transformation of mature cystic teratoma into undifferentiated carcinoma: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:e05240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ikota H, Kaneko K, Takahashi S, et al. Malignant transformation of ovarian mature cystic teratoma with a predominant pulmonary type small cell carcinoma component. Pathol Int. 2012;62:276‐280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Andor N, Graham TA, Jansen M, et al. Pan‐cancer analysis of the extent and consequences of intratumor heterogeneity. Nat Med. 2016;22:105‐113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caswell DR, Swanton C. The role of tumour heterogeneity and clonal cooperativity in metastasis, immune evasion and clinical outcome. BMC Med. 2017;15:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sugino K, Tamura R, Nakaoka H, et al. Germline and somatic mutations of homologous recombination‐associated genes in Japanese ovarian cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2019;9:17808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yachida N, Yoshihara K, Suda K, et al. Biological significance of KRAS mutant allele expression in ovarian endometriosis. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:2020‐2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yamaguchi M, Nakaoka H, Suda K, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of clonal selection and diversification in normal endometrial epithelium. Nat Commun. 2022;13:943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114‐2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows‐Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754‐1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA‐MEM. arXiv Preprint arXiv:13033997 ; 2013.

- 20. Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078‐2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next‐generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297‐1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next‐generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491‐498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Neph S, Kuehn MS, Reynolds AP, et al. BEDOPS: high‐performance genomic feature operations. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1919‐1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:841‐842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim S, Scheffler K, Halpern AL, et al. Strelka2: fast and accurate calling of germline and somatic variants. Nat Methods. 2018;15:591‐594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen X, Schulz‐Trieglaff O, Shaw R, et al. Manta: rapid detection of structural variants and indels for germline and cancer sequencing applications. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1220‐1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Genomes Project C , Auton A, Brooks LD, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68‐74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tennessen JA, Bigham AW, O'Connor TD, et al. Evolution and functional impact of rare coding variation from deep sequencing of human exomes. Science. 2012;337:64‐69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434‐443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McLaren W, Gil L, Hunt SE, et al. The Ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol. 2016;17:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, et al. COSMIC: the catalogue of somatic mutations In cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D941‐D947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shen R, Seshan VE. FACETS: allele‐specific copy number and clonal heterogeneity analysis tool for high‐throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baez‐Ortega A, Gori K. Computational approaches for discovery of mutational signatures in cancer. Brief Bioinform. 2019;20:77‐88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maura F, Degasperi A, Nadeu F, et al. A practical guide for mutational signature analysis in hematological malignancies. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alexandrov LB, Kim J, Haradhvala NJ, et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature. 2020;578:94‐101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gori K, Baez‐Ortega A. Sigfit: flexible Bayesian inference of mutational signatures. bioRxiv. 2020;372896. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nishiwaki M, Yamamoto T, Tone S, et al. Genotyping of human papillomaviruses by a novel one‐step typing method with multiplex PCR and clinical applications. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1161‐1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tamura R, Yoshihara K, Saito T, et al. Novel therapeutic strategy for cervical cancer harboring FGFR3‐TACC3 fusions. Oncogene. 2018;7:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yemelyanova A, Vang R, Kshirsagar M, et al. Immunohistochemical staining patterns of p53 can serve as a surrogate marker for TP53 mutations in ovarian carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and nucleotide sequencing analysis. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1248‐1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yachida N, Yoshihara K, Suda K, et al. ARID1A protein expression is retained in ovarian endometriosis with ARID1A loss‐of‐function mutations: implication for the two‐hit hypothesis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:14260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Smith NJ, Fenton TR. The APOBEC3 genes and their role in cancer: insights from human papillomavirus. J Mol Endocrinol. 2019;62:R269‐R287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McGranahan N, Favero F, de Bruin EC, Birkbak NJ, Szallasi Z, Swanton C. Clonal status of actionable driver events and the timing of mutational processes in cancer evolution. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:283ra254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Burns MB, Temiz NA, Harris RS. Evidence for APOBEC3B mutagenesis in multiple human cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45:977‐983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Roberts SA, Lawrence MS, Klimczak LJ, et al. An APOBEC cytidine deaminase mutagenesis pattern is widespread in human cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45:970‐976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Petljak M, Maciejowski J. Molecular origins of APOBEC‐associated mutations in cancer. DNA Repair (Amst). 2020;94:102905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Alexandrov LB, Nik‐Zainal S, Wedge DC, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415‐421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cancer Genome Atlas Research N . Integrated genomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature. 2017;543:378‐384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chiang AJ, Chen DR, Cheng JT, Chang TH. Detection of human papillomavirus in squamous cell carcinoma arising from dermoid cysts. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54:559‐566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jakobsdottir GM, Brewer DS, Cooper C, Green C, Wedge DC. APOBEC3 mutational signatures are associated with extensive and diverse genomic instability across multiple tumour types. BMC Biol. 2022;20:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Burns MB, Lackey L, Carpenter MA, et al. APOBEC3B is an enzymatic source of mutation in breast cancer. Nature. 2013;494:366‐370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cannataro VL, Gaffney SG, Sasaki T, et al. APOBEC‐induced mutations and their cancer effect size in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2019;38:3475‐3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Henderson S, Chakravarthy A, Su X, Boshoff C, Fenton TR. APOBEC‐mediated cytosine deamination links PIK3CA helical domain mutations to human papillomavirus‐driven tumor development. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1833‐1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Boichard A, Tsigelny IF, Kurzrock R. High expression of PD‐1 ligands is associated with kataegis mutational signature and APOBEC3 alterations. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;6:e1284719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang S, Jia M, He Z, Liu XS. APOBEC3B and APOBEC mutational signature as potential predictive markers for immunotherapy response in non‐small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2018;37:3924‐3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Takamatsu S, Hamanishi J, Brown JB, et al. Mutation burden‐orthogonal tumor genomic subtypes delineate responses to immune checkpoint therapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Song XC, Wang YX, Yu M, Cao DY, Yang JX. Case report: Management of Recurrent Ovarian Squamous Cell Carcinoma with PD‐1 inhibitor. Front Oncol. 2022;12:789228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wu M, Bennett JA, Reid P, Fleming GF, Kurnit KC. Successful treatment of squamous cell carcinoma arising from a presumed ovarian mature cystic teratoma with pembrolizumab. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2021;37:100837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li X, Tang X, Zhuo W. Malignant transformation of ovarian teratoma responded well to immunotherapy after failed chemotherapy: a case report. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:8499‐8505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Donehower LA, Soussi T, Korkut A, et al. Integrated analysis of TP53 gene and Pathway alterations in the cancer genome atlas. Cell Rep. 2019;28:3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sung YN, Kim D, Kim J. p53 immunostaining pattern is a useful surrogate marker for TP53 gene mutations. Diagn Pathol. 2022;17:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kobel M, Piskorz AM, Lee S, et al. Optimized p53 immunohistochemistry is an accurate predictor of TP53 mutation in ovarian carcinoma. J Pathol Clin Res. 2016;2:247‐258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rabban JT, Garg K, Ladwig NR, Zaloudek CJ, Devine WP. Cytoplasmic pattern p53 Immunoexpression in pelvic and endometrial carcinomas with TP53 mutation involving nuclear localization domains: an uncommon but potential diagnostic pitfall with clinical implications. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45:1441‐1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cole AJ, Dwight T, Gill AJ, et al. Assessing mutant p53 in primary high‐grade serous ovarian cancer using immunohistochemistry and massively parallel sequencing. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Park E, Han H, Choi SE, et al. p53 immunohistochemistry and mutation types mismatching in high‐grade serous ovarian cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Saito Y, Koya J, Araki M, et al. Landscape and function of multiple mutations within individual oncogenes. Nature. 2020;582:95‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Saito Y, Koya J, Kataoka K. Multiple mutations within individual oncogenes. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:483‐489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Jin N, Keam B, Cho J, et al. Therapeutic implications of activating noncanonical PIK3CA mutations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e150335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1.

Table S1.