Abstract

Numbers of gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-producing cells reactive to ESAT-6 antigen were increased in recent converters to purified protein derivative positivity and in tuberculosis patients but not in unvaccinated or Mycobacterium bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy donors. ESAT-6-reactive IFN-γ-producing cells in recent converters and tuberculosis patients recognized similar synthetic peptides. Thus, ESAT-6 is a potential candidate for use in detection of early, as well as active, tuberculosis and for control of the disease.

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the leading infectious diseases in adults, causing around 2 million deaths annually (18). The human immunodeficiency virus pandemic and the emergence of resistant strains of the causative bacilli have led to an elevated incidence of TB (3). New diagnostic methods for early detection of TB are urgently needed to replace or support identification of sputum-positive cases. Intradermal skin tests using Mycobacterium tuberculosis purified protein derivative (PPD) have proved to be unreliable because PPD is a poorly defined mycobacterial antigen mixture that contains antigens which are common to strains from the M. tuberculosis complex, environmental nontuberculous strains, and the vaccine substrain Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) (5). Thus, the value of PPD skin testing for TB diagnosis is questionable.

In the early or active phase of infection, secreted proteins are produced by metabolically active mycobacteria (1). The M. tuberculosis-specific early-secreted antigenic target 6-kDa protein (ESAT-6) stimulates T cells from TB patients to proliferate and produce gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (6, 7, 10, 11, 14, 16). ESAT-6 has been considered a possible candidate for use in the diagnosis of TB because of its high specificity and sensitivity (1, 2). Therefore, we investigated the frequencies of human IFN-γ spot-forming cells (SFCs) reactive to ESAT-6 by using the highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay in order to define host sensitivity to M. tuberculosis infection in recent converters to PPD skin test positivity and in patients with active TB.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from 16 healthy donors (HDs) (8 BCG-vaccinated HDs [blood bank, Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany] and 8 unvaccinated HDs [Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Mass.]) with no history of mycobacterial infection or prior contact with infected material and from 12 unvaccinated HDs (Boston) who had recently converted to PPD positivity (recent converters [RCs] and who had had positive PPD skin tests (diameter of induration, >15 mm) less than 6 months before the study was initiated. No RC had signs or symptoms of TB, and all were immediately treated with anti-TB chemotherapy; therefore, there is no evidence of development of the disease in these individuals. PBMCs from 15 untreated Caucasian TB patients at the Chest Hospital Heckeshorn-Zehlendorf (Free University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany) were collected after informed consent was obtained. Active pulmonary TB was confirmed by culture of M. tuberculosis from sputum, or by PCR in those patients without positive cultures, and the extent of disease was assessed by X-ray (4). The investigation protocol was approved by the Ethics Commission of the Free University of Berlin.

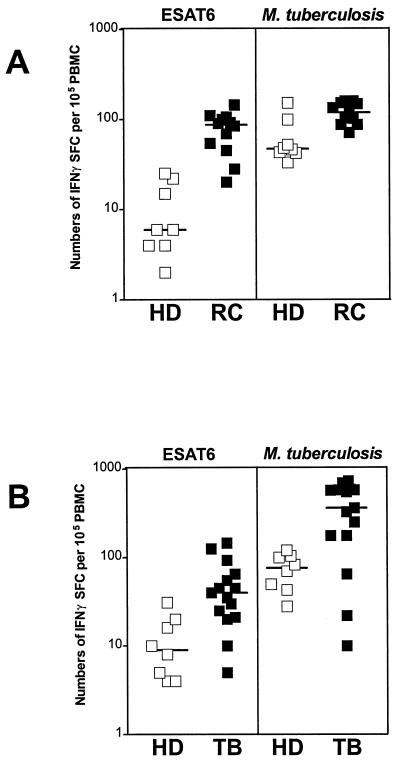

We compared the numbers of IFN-γ SFCs reactive to recombinant ESAT-6 protein (3 μg/ml; kindly provided by M. L. Gennaro, Public Health Research Institute, New York, N.Y.), lysed M. tuberculosis H37Ra (3 μg/ml; Difco Laboratories, Augsburg, Germany), or synthetic ESAT-6 peptides (10 μg/ml; see below) in HDs, RCs and TB patients by ELISPOT assay (9). Anti-human IFN-γ monoclonal antibodies (MAB285; R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany) and goat biotinylated anti-human IFN-γ antibodies (BAF285; R&D Systems) were used to detect IFN-γ-producing cells. For each individual, control values were subtracted from those obtained for antigen-stimulated cells, and results are expressed as the number of IFN-γ SFCs per 105 PBMCs. A positive designation for an individual was given when antigen-specific IFN-γ SFCs exceeded the mean + 3 standard deviations of values for antigen-free controls. Figure 1 shows that numbers of ESAT-6-specific IFN-γ SFCs were increased in 10 of 12 RCs (median [range] of IFN-γ SFCs = 87 [20 to 144]) and in 8 of 15 TB patients (40 [5 to 145]), compared with 0 of 16 HDs (7 [2 to 31]) (P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test). The lower levels of IFN-γ SFCs produced in response to ESAT-6 in TB patients compared to those in RCs are probably due to the well-described transient immunosuppression observed in persons with active pulmonary TB (15). Furthermore, numbers of M. tuberculosis-specific IFN-γ SFCs were higher in 11 of 15 TB patients (360 [10 to 725]), compared with 0 of 11 RCs (119 [71 to 159]) and 0 of 16 HDs (51 [28 to 152]) (P < 0.05). Note that BCG vaccination may have an influence on the background levels of IFN-γ SFCs to M. tuberculosis in vaccinated HDs. Importantly, none of the RCs was BCG vaccinated, strongly suggesting that the high-level IFN-γ SFCs to ESAT-6 in these donors reflects infection with M. tuberculosis.

FIG. 1.

Numbers of IFN-γ SFCs among HDs, PPD-positive RCs, and TB patients. Freshly isolated PBMCs (105/ml) from 8 unvaccinated HDs and from 12 RC donors from Boston (A) and from 8 BCG-vaccinated HDs and 15 TB patients (TB) from Berlin (B) were incubated in the presence of medium, M. tuberculosis lysate (3 μg/ml), or ESAT-6 (3 μg/ml) for 48 h, and numbers of IFN-γ SFCs were determined afterward. Control values were subtracted from those obtained after antigen stimulation, and results from three different experiments are expressed as numbers of IFN-γ SFCs per 105 PBMCs. Bars indicate median values.

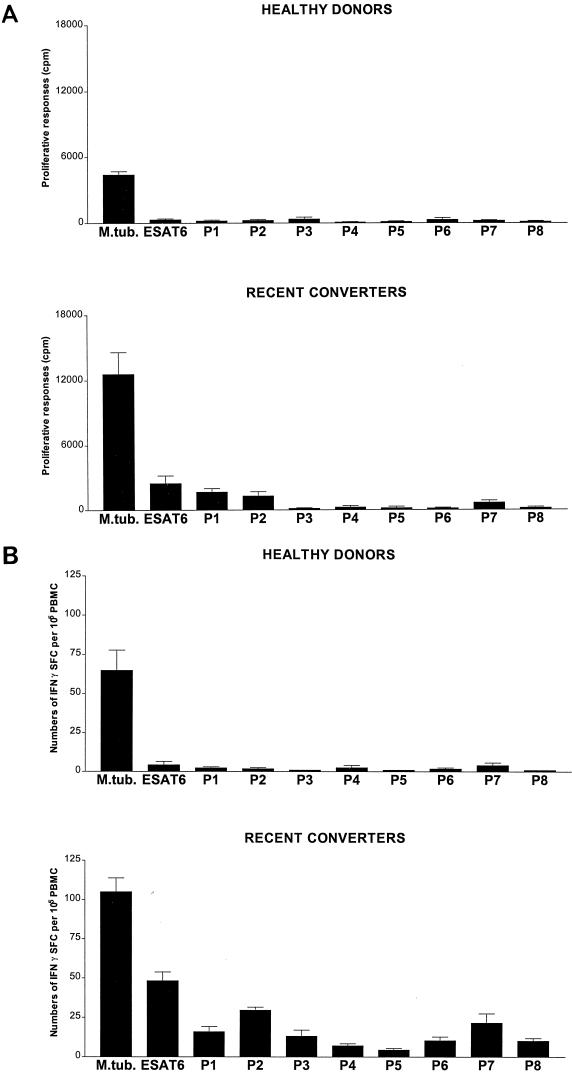

In order to define specific responses to ESAT-6 in more detail, we analyzed proliferative responses and IFN-γ SFCs of HD and RC PBMCs cultured with overlapping synthetic peptides of ESAT-6 (Fig. 2). Overlapping synthetic peptides of ESAT-6 were prepared by Jerini Bio Tools GmbH (Berlin, Germany), using a modified synthesis protocol, on an ABI 433A peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany) as previously described (16). The amino acid sequences of the ESAT-6 synthetic 20-mer peptides that span the ESAT-6 sequence are shown in Table 1. For proliferation assays, PBMCs (106/ml) were incubated in 96-well plates with ESAT-6 (3 μg/ml), lysed M. tuberculosis (3 μg/ml), or synthetic ESAT-6 peptides (10 μg/ml) for 5 days and cultures were pulsed with [3H]thymidine for the last 18 h. Figure 2A shows that after 5 days, T-cell proliferative responses of PBMCs from RCs were preferentially directed against P1, P2, and P7, while HD PBMCs did not respond. Thus, the proliferative response of PBMCs from RCs, but not HDs, exhibited a preferential recognition of the N-terminal synthetic peptides of ESAT-6, similar to that of T cells from patients with active TB, as previously shown (16). However, the ELISPOT assay shows a broader pattern of recognition for the overlapping synthetic peptides of ESAT-6 in RC (Fig. 2B). Our data indicate that PBMCs from RCs recognize several epitopes of ESAT-6, particularly those at the N terminus, and suggest that the ELISPOT assay is more sensitive than measurement of proliferative responses.

FIG. 2.

Proliferative and IFN-γ SFC responses to synthetic peptides. Freshly isolated PBMCs from 8 HDs and from 8 PPD-positive ESAT-6 RCs were incubated in the presence of medium, M. tuberculosis (3 μg/ml), ESAT-6 (3 μg/ml), or eight overlapping synthetic ESAT-6 peptides(P1 to P8). Proliferative responses (A) and numbers of IFN-γ SFCs (B) were determined after 5 or 2 days, respectively. Control values were subtracted from those obtained after antigen stimulation, and results are expressed either as mean counts per minute ± standard deviation or numbers of IFN-γ SFCs per 105 PBMCs in three independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

Amino acid sequences of the ESAT-6 overlapping synthetic 20-mer peptides

| ESAT-6 peptide | Amino acid sequence |

|---|---|

| P1 | MTEQQWNFAGIEAAASAIQG |

| P2 | GIEAAASAIQGNVTSIHSLLD |

| P3 | NVTSIHSLLDEGKQSLTKLA |

| P4 | EGKQSLTKLAAAWGGSGSEA |

| P5 | AAWGGSGSEAYQGVQQKWDA |

| P6 | YQGVQQKWDATATELNNALQ |

| P7 | TATELNNALQNLARTISEAG |

| P8 | NLARTISEAGQAMASTEGNV |

The present investigation has focused on the potential use of ESAT-6 for early diagnosis of TB infection. New tests for diagnosis of TB should be both highly sensitive and specific to allow the identification of active infection or paucibacillary disease. Our results show that numbers of IFN-γ SFCs reactive to ESAT-6 are increased in patients with active TB and, to a lower but significant extent, in RCs. Of importance, positive T-cell responses to ESAT-6 do not distinguish individuals with active disease from those previously infected with M. tuberculosis. However, the occurrence of low levels of IFN-γ-producing cells in response to ESAT-6 in PPD-negative HDs, compared to higher levels of SFCs in PPD-positive RCs, may indicate either past M. tuberculosis infection in HDs, latent TB, or recent infection with M. tuberculosis where PPD responses are not yet detectable. Furthermore, recognition of overlapping synthetic ESAT-6 peptides by T cells from RCs encompasses regions within the ESAT-6 molecule similar to that recognized by T cells from TB patients (16). Recently, it has been shown that PBMCs from Ethiopian TB patients express a pattern of reactivity similar to that seen in RCs in our study (11). Thus, our data indicate a parallel between the positive responses to ESAT-6 in RCs and TB patients and suggest that ESAT-6 may have potential for use as an antigen in the diagnosis of subclinical as well as active TB(1).

Different secreted mycobacterial antigens have been used for diagnostic purposes (1). MPT64, which is specific for the M. tuberculosis complex, has been used in skin tests of immunized animals and humans, but results have been controversial (12). The recent identification of regions of the M. tuberculosis genome that are absent in BCG provides a unique opportunity to develop new and highly specific diagnostic reagents (8, 19). Both ESAT-6 and the closely linked antigen CFP10 have consistently been shown to be promising candidates for TB diagnostics due to their high degree of specificity and sensitivity (7, 10, 11, 13, 16, 17). Our data further support the possibility of using ESAT-6 for detection of early subclinical and active TB and for monitoring of the disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Schaberg and S. Ziege, Chest Hospital Heckeshorn-Zehlendorf, Berlin, Germany, for medical support; M. L. Gennaro, Public Health Research Institute, New York, N.Y., for ESAT-6; and Gert Hausdorf, Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany, for helpful discussions.

S.H.E.K. acknowledges financial support from the German Leprosy Relief Association and the Federal Ministry for Science and Technology; M.E.M. acknowledges the receipt of a Marie Curie Individual Fellowship from the European Commission.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen, P., M. E. Munk, J. M. Pollock, and T. M. Doherty. Towards highly specific immune-based diagnosis of tuberculosis: the next generation of tuberculin. Lancet, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Arend S M, Andersen P, van Meijgaarden K E, Skøjt R L V, Subronto Y W, van Dissel J T, Ottenhoff T H M. Detection of active tuberculosis infection by T cell responses to early-secreted antigenic target 6-kDa protein and culture filtrate protein 10. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1850–1854. doi: 10.1086/315448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom B R, Murray C J. Tuberculosis: commentary on a reemergent killer. Science. 1992;257:1055–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falk A, O'Connor J B, Pratt P C. Classification of pulmonary tuberculosis. In: Falk A, O'Connor J B, Pratt P C, Webb J A, Wier J A, Wolinsky E, editors. Diagnosis standards and classification of tuberculosis. Vol. 12. New York, N.Y: National Tuberculosis and Respiratory Disease Association; 1969. pp. 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harboe M. Antigens of PPD, old tuberculin, and autoclaved Mycobacterium bovis BCG studied by crossed immunoelectrophoresis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;124:80–87. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1981.124.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufmann S H. Immunity to intracellular bacteria. In: Paul W, editor. Fundamental immunology. 4th ed. New York, N.Y: Philadelphia Lippincott-Raven; 1998. pp. 1335–1371. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lalvani A, Brookes R, Wilkinson R, Malin A, Pathan A, Anderson P, Dockrell H, Pasvol G, Hill A. Human cytolytic and interferon gamma-secreting CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:270–275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahairas G G, Sabo P J, Hickey M J, Singh DC, Stover C K. Molecular analysis of genetic differences between Mycobacterium bovis BCG and virulent M. bovis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1274–1282. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1274-1282.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moller S A, Borrebaeck C A. A filter immuno-plaque assay for the detection of antibody secreting cells in vitro. J Immunol Methods. 1985;79:195–204. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mustafa A S, Amoudy H A, Wiker H G, Abal A T, Ravn P, Oftung F, Andersen P. Comparison of antigen specific T cell responses of tuberculosis patients using complex or single antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 1998;48:535–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1998.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravn P, Demissie A, Eguale T, Wondwosson H, Lein D, Amoudy H, Mustafa A S, Jensen A K, Holm A, Rosenkrands I, Oftung F, Olobo J, von-Reyn C F, Andersen P. Human T cell responses to the ESAT-6 antigen from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:637–645. doi: 10.1086/314640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roche P W, Winter N, Triccas J A, Feng C G, Britton W J. Expression of Mycobacterium tuberculosis MPT64 in recombinant Mycobacterium smegmatis: purification, immunogenicity and application to skin tests for tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;103:226–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skjøt R L V, Oettinger T, Rosenkrands I, Ravn P, Brock I, Jacobsen S, Andersen P. Comparative evaluation of low-molecular-mass proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis identifies members of the ESAT-6 family as immunodominant T-cell antigens. Infect Immun. 2000;68:214–220. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.214-220.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sørensen A L, Nagai S, Houen G, Andersen P, Andersen Å B. Purification and characterization of a low-molecular-mass T-cell antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1710–1717. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1710-1717.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toossi Z, Ellner J J. Mechanisms of anergy in tuberculosis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;1:221–238. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80166-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulrichs T, Munk M E, Mollenkopf H, Behr-Perst S, Colangeli R, Gennaro M L, Kaufmann S H. Differential T cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT-6 in tuberculosis patients and healthy donors. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3949–3958. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<3949::AID-IMMU3949>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Pinxteren L A H, Ravn P, Agger E M, Pollock J, Andersen P. Diagnosis of tuberculosis based on the two specific antigens ESAT-6 and CFP10. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:155–160. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.2.155-160.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. The world health report 1999. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zumarraga M, Bigi F, Alito A, Romano M I, Cataldi A. A 12.7 kb fragment of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome is not present in Mycobacterium bovis. Microbiology. 1999;145:893–897. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-4-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]