Abstract

Objective.

To provide updated guidelines for pharmacologic management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), focusing on treatment of oligoarthritis, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) arthritis, and systemic JIA with and without macrophage activation syndrome. Recommendations regarding tapering and discontinuing treatment in inactive systemic JIA are also provided.

Methods.

We developed clinically relevant Patient/Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes questions. After conducting a systematic literature review, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach was used to rate the quality of evidence (high, moderate, low, or very low). A Voting Panel including clinicians and patients/caregivers achieved consensus on the direction (for or against) and strength (strong or conditional) of recommendations.

Results.

Similar to those published in 2019, these JIA recommendations are based on clinical phenotypes of JIA, rather than a specific classification schema. This guideline provides recommendations for initial and subsequent treatment of JIA with oligoarthritis, TMJ arthritis, and systemic JIA as well as for tapering and discontinuing treatment in subjects with inactive systemic JIA. Other aspects of disease management, including factors that influence treatment choice and medication tapering, are discussed. Evidence for all recommendations was graded as low or very low in quality. For that reason, more than half of the recommendations are conditional.

Conclusion.

This clinical practice guideline complements the 2019 American College of Rheumatology JIA and uveitis guidelines, which addressed polyarthritis, sacroiliitis, enthesitis, and uveitis. It serves as a tool to support clinicians, patients, and caregivers in decision-making. The recommendations take into consideration the severity of both articular and nonarticular manifestations as well as patient quality of life. Although evidence is generally low quality and many recommendations are conditional, the inclusion of caregivers and patients in the decision-making process strengthens the relevance and applicability of the guideline. It is important to remember that these are recommendations. Clinical decisions, as always, should be made by the treating clinician and patient/caregiver.

INTRODUCTION

Reflecting the changing medical landscape, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) regularly updates clinical practice guidelines and plans to review these annually and update as needed. The process for updating the 2011 and 2013 juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) guidelines (1,2) began in 2017. Important clinical topics for consideration were first identified at a meeting to define the scope of the guidelines. Advances in the treatment of JIA and better understanding of pathogenesis dictated separating this clinical practice guideline into several parts due to the breadth of topics. The first part, addressing polyarthritis, sacroiliitis, enthesitis, and uveitis, was published in 2 articles in 2019 (3,4). The second part, presented here in 2 articles, covers 1) oligoarthritis, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) arthritis, and systemic JIA, and 2) nonpharmacologic treatments, patient monitoring, immunizations, and imaging (5). The methods and literature review described below reflect the unified process used for the second part of these guidelines, including both articles. Recommendations were intended to be complementary to the 2019 guidelines and are grouped based on disease phenotype and severity, not by specific classification criteria, reflecting decision-making in clinical practice.

Following the selection of topics, we developed clinically relevant Patient/Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes (PICO) questions. Using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, recommendations were then developed based on the best available evidence for commonly encountered clinical scenarios. Prior to final voting, input was sought from relevant stakeholders, including a panel of young adults with JIA and caregivers of children with JIA, to consider their values and perspectives in making recommendations. Both the patient/caregiver and guideline Voting Panels stressed the need for individualized treatment while being mindful of available evidence.

METHODS

This guideline followed the ACR guideline development process and ACR policy guiding management of conflicts of interest and disclosures (https://www.rheumatology.org/Practice-Quality/Clinical-Support/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines), which include GRADE methodology (6,7) and adheres to Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation criteria (8). Supplementary Appendix 1 (available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42037/abstract) includes a detailed description of the methods. Briefly, the Core Leadership Team (KBO, DBH, DJL, SS) drafted clinical PICO questions. PICO questions were revised and finalized based on feedback from the entire guideline development group and the public. The Literature Review Team performed systematic literature reviews for each PICO (for search terms, see Supplementary Appendix 2, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42037/abstract), graded the quality of evidence (high, moderate, low, or very low), and produced the evidence report (Supplementary Appendix 3, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42037/abstract). It should be noted that GRADE methodology does not distinguish between lack of evidence (i.e., none) and very low–quality evidence. The Core Team defined multiple critical study outcome(s) for PICOs relevant to each JIA phenotype (Supplementary Appendix 4, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42037/abstract).

A panel of 15 members, including young adults with JIA and caregivers of children with JIA, met virtually (moderated by the principal investigator [KBO]), reviewed the evidence report, and provided input to the Voting Panel. Two members of this panel were also members of the Voting Panel to ensure that the patient voice was part of the entire process. The Voting Panel reviewed the evidence report and patient/caregiver perspectives and then discussed and voted on recommendation statements. Consensus required ≥70% agreement on both direction (for or against) and strength (strong or conditional) of each recommendation, as per ACR practice. A recommendation could be either in favor of or against the proposed intervention and either strong or conditional. According to GRADE, a recommendation is categorized as strong if the panel is very confident that the benefits of an intervention clearly outweigh the harms (or vice versa); a conditional recommendation denotes uncertainty regarding the balance of benefits and harms, such as when the evidence quality is low or very low, or when the decision is sensitive to individual patient preferences, or when costs are expected to impact the decision. Thus, conditional recommendations refer to decisions in which incorporation of patient preferences is a particularly essential element of decision-making. Examples of each class of pharmacologic intervention addressed in the recommendations are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Classes of interventions

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs | Any at therapeutic dosing (ibuprofen, naproxen, tolmetin, indomethacin, meloxicam, nabumetone, diclofenac, piroxicam, etodolac, celecoxib) |

| Conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs | Methotrexate, sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporin A, tacrolimus) |

| Biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs | Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol); other biologic response modifiers (abatacept, tocilizumab, anakinra, canakinumab) |

| Glucocorticoids | Oral (any); intravenous (any); intraarticular (triamcinolone acetonide, triamcinolone hexacetonide) |

Rosters of the Core Leadership Team, Literature Review Team, and both panels are included in Supplementary Appendix 5 (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42037/abstract).

Guiding principles

The development of the recommendations presented herein was guided by the following principles:

Consistent with the ACR’s 2019 JIA guidelines, these recommendations are for persons already diagnosed as having JIA.

Aside from poor prognostic features specified within the recommendations themselves (e.g., specific joints for oligoarthritis, macrophage activation syndrome [MAS]), coexisting extraarticular conditions that would influence disease management, such as uveitis, psoriasis, or inflammatory bowel disease, are not addressed within these guidelines.

Recommendations are intended to be used by all clinicians caring for persons with JIA and assume that patients do not have contraindications to the recommended pharmacologic treatments.

Longer-term glucocorticoid therapy in childhood is not appropriate because of its effects on bone health and growth. Thus, wherever glucocorticoids are suggested, recommended treatment should be limited to the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration possible.

Shared decision-making with families and patients is important when considering treatment options.

RESULTS/RECOMMENDATIONS

The initial literature review included topics addressed in this report and in the second report (9), and identified 4,308 articles in searches for all PICO questions through August 7, 2019. A July 9, 2020 search update identified 367 more references, for a total of 4,675 articles after duplicates and non-English publications were removed. After exclusion of 2,291 titles and abstracts, 2,384 full-text articles were screened. Of these, 1,939 were excluded (Supplementary Appendix 6, on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42037/abstract), leaving 445 articles to be considered for the evidence report. Ultimately, 336 articles were matched to PICO questions and included in the final evidence report. Quality of evidence was uniformly low or very low; 17 PICO questions lacked any associated evidence and as per GRADE methodology were categorized as very low (Tables 2–7). The recommendations that follow are based on 62 PICO questions. Several PICO questions were split into 24 sub-PICO questions to improve specificity. Nine questions initially posed were discarded by the Voting Panel because of redundancy or lack of relevance. Final recommendations are described below and in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, which include reference(s) to which PICO question(s) in the evidence report correspond to the recommendation statement.

Table 2.

Strength of recommendations and quality of supporting evidence*

| Strength of recommendation |

Quality of supporting evidence |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of recommendations | Conditional | Strong | Very low | Low | Moderate | High | |

| Oligoarthritis | 9 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

|

| |||||||

| TMJ arthritis | 7 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| |||||||

| Systemic JIA | 9 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| |||||||

| Total | 25 | 16 | 9 | 23 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

TMJ = temporomandibular joint; JIA = juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Table 7.

Systemic JIA with inactive disease*

| Recommendation | Certainty of evidence | PICO evidence report(s) basis | Page no(s). of evidence tables† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tapering and discontinuing glucocorticoids is strongly recommended after inactive disease has been attained. | Very low | PICO 28. In patients with systemic JIA with inactive disease treated with oral steroids, is taper to discontinuation of steroids superior to continuing long-term stable-dose steroids for preventing disease flare and minimizing side effects/medication toxicity? | 139 |

| Tapering and discontinuing biologic DMARDs is conditionally recommended after inactive disease has been attained. | Very low | PICO 29. In patients with Systemic JIA in clinical remission with biologic monotherapy, is tapering by decreasing dosage superior to tapering dosing interval at preventing disease exacerbation, preventing development of antidrug antibodies, and minimizing medication toxicity? | 140–143 |

JIA = juvenile idiopathic arthritis; PICO = Patient/Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes; DMARDs = disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

In Supplementary Appendix 3, on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42037/abstract.

Table 3.

Oligoarticular JIA*

| Recommendation | Certainty of evidence | PICO evidence report(s) basis | Page no(s). of evidence tables† |

|---|---|---|---|

| A trial of scheduled NSAIDs is conditionally recommended as part of initial therapy. | Very low | PICO 1. in children with oligoarticular JIA, should a trial of scheduled NSAIDs be recommended? | 6–9 |

| IAGCs are strongly recommended as part of initial therapy. | Very low | PICO 2. In children with oligoarticular JIA, should adding IAGCs to initial therapy be recommended? | 10–19 |

| Triamcinolone hexacetonide is strongly recommended as the preferred agent. | Low | PICO 4. In children with oligoarticular JIA, should a specific steroid type be recommended for intraarticular injection? | 21–27 |

| Oral glucocorticoids are conditionally recommended against as part of initial therapy. | Very low | PICO 3. In children with oligoarticular JIA, should adding oral steroids to initial therapy be recommended? | 19–20 |

| Conventional synthetic DMARDs are strongly recommended if there is inadequate response to scheduled NSAIDs and/or IAGCs. MTX is conditionally recommended as a preferred agent over LEF, SSZ, and HCQ (in that order). | Low (MTX); Very low (LEF, SSZ, HCQ) |

PICO 5. In children with oligoarticular JIA, should DMARD therapies be recommended, and should there be any preferred order of treatment: MTX (subcutaneous or oral), LEF, SSZ, and/or HCQ? | 28–41 |

| Biologic DMARDs are strongly recommended if there is inadequate response to or intolerance of NSAIDs and/or IAGCs and at least 1 conventional synthetic DMARD. There is no preferred biologic DMARD. |

Very low | PICO 6. In children with oligoarticular JIA, should biologic therapies be recommended, and should there be any preferred order of treatment: TNFi treatment, biologic treatments with other mechanisms of action? | 42–47 |

| Consideration of risk factors for poor outcome (e.g., involvement of ankle, wrist, hip, sacroiliac joint, and/or TMJ, presence of erosive disease or enthesitis, delay in diagnosis, elevated levels of inflammation markers, symmetric disease) is conditionally recommended to guide treatment decisions. | Very low | PICO 9. In children with oligoarticular JIA, should poor prognostic features alter the treatment paradigm? PICO 19. In children with JIA with active TMJ arthritis, should poor prognostic features alter the treatment paradigm? |

51–52 60 |

| Use of validated disease activity measures is conditionally recommended to guide treatment decisions, especially to facilitate treat-to-target approaches. | Very low | PICO 10. In children with oligoarticular JIA, should disease activity measures alter the treatment paradigm? | 52 |

JIA = juvenile idiopathic arthritis; PICO = Patient/Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; IAGCs = intraarticular glucocorticoids; DMARDs = disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; MTX = methotrexate; LEF = leflunomide; SSZ = sulfasalazine; HCQ = hydroxychloroquine; TNFi = tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; TMJ = temporomandibular joint.

In Supplementary Appendix 3, on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42037/abstract.

Table 4.

TMJ arthritis*

| Recommendation | Certainty of evidence | PICO evidence report(s) basis | Page no(s). of evidence tables† |

|---|---|---|---|

| A trial of scheduled NSAIDs is conditionally recommended as part of initial therapy. | Very low | PICO 11. In children with JIA with active TMJ arthritis, should a trial of scheduled NSAIDs be recommended, and should there be any preferred NSAID treatment? | 53 |

|

| |||

| IAGCs are conditionally recommended as part of initial therapy. | Very low | PICO 12. In children with JIA with active TMJ arthritis, should adding intraarticular glucocorticoids to initial therapy be recommended? | 53–57 |

| There is no preferred agent. | Very low | PICO 14. In children with JIA with active TMJ arthritis, should a specific steroid type be recommended for intraarticular injection? | 58 |

|

| |||

| Oral glucocorticoids are conditionally recommended against as part of initial therapy. | Very low | PICO 13. In children with JIA with active TMJ arthritis, should adding oral glucocorticoids to initial therapy be recommended? | 58 |

|

| |||

| Conventional synthetic DMARDs are strongly recommended for inadequate response to or intolerance of NSAIDs and/or IAGCs. MTX is conditionally recommended as a preferred agent over LEF. |

Very low | PICO 15. In children with JIA with active TMJ arthritis, should DMARD therapies be recommended, and should there be any preferred order of treatment: MTX (subcutaneous and oral), LEF, SSZ, and/or HCQ? | 58–59 |

|

| |||

| Biologic DMARDs are conditionally recommended for inadequate response to or intolerance of NSAIDs and/or IAGCs and at least 1 conventional synthetic DMARD. There is no preferred biologic agent. |

Very low | PICO 16. In children with JIA with active TMJ arthritis, should systemic biologic therapies be recommended, and should there be any preferred order of treatment: TNFi, biologic treatments with other mechanisms of action? | 59 |

|

| |||

| Consideration of poor prognostic features (e.g., involvement of ankle, wrist, hip, sacroiliac joint, and/or TMJ, presence of erosive disease or enthesitis, delay in diagnosis, elevated levels of inflammation markers, symmetric disease) is conditionally recommended to guide treatment decisions. | Very low | PICO 19. In children with JIA with active TMJ arthritis, should poor prognostic features alter the treatment paradigm? | 60 |

TMJ = temporomandibular joint; PICO = Patient/Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; JIA = juvenile idiopathic arthritis; IAGCs = intraarticular glucocorticoids; DMARDs = disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; MTX = methotrexate; LEF = leflunomide; SSZ = sulfasalazine; HCQ = hydroxychloroquine; TNFi = tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

In Supplementary Appendix 3, on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42037/abstract.

Table 5.

Systemic JIA without MAS*

| Recommendation | Certainty of evidence | PICO evidence report(s) basis | Page no(s). of evidence tables† |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSAIDs are conditionally recommended as initial monotherapy. Oral glucocorticoids are conditionally recommended against as initial monotherapy. |

Very low | PICO 20. In patients with treatment-naive, newly diagnosed Systemic JIA without MAS, should non-DMARD treatment (NSAIDs, glucocorticoids) be used as initial therapy? | 61–67 |

| Conventional synthetic DMARDs are strongly recommended against as initial monotherapy. | Very low | PICO 21. In patients with treatment-naive, newly diagnosed Systemic JIA without MAS, should DMARD treatment (MTX, calcineurin inhibitor) be used as initial therapy, and is there a preferred order? | 67–68 |

| Biologic DMARDs (IL-1 and IL-6 inhibitors) are conditionally recommended as initial monotherapy. There is no preferred agent. |

Very low | PICO 22. In patients with treatment-naive, newly diagnosed Systemic JIA without MAS, should biologic treatment (anakinra, canakinumab, tocilizumab, or others) be used as initial therapy, and is there a preferred order? | 69–71 |

| IL-1 and IL-6 inhibitors are strongly recommended over a single or combination of conventional synthetic DMARDs for inadequate response to or intolerance of NSAIDs and/or glucocorticoids. | Very low | PICO 23. In patients with Systemic JIA without MAS who do not respond to initial therapy with nonbiologic treatments (NSAIDs, glucocorticoids, DMARDs), should nonbiologic treatments be combined or biologic treatment started? | 72–130 |

| Biologic DMARDs or conventional synthetic DMARDs are strongly recommended over long-term glucocorticoids for residual arthritis and incomplete response to IL-1 and/or IL-6 inhibitors. There is no preferred agent. |

Very low | PICO 27. In patients with Systemic JIA in whom inactive disease is not achieved despite treatment with both IL-1 and IL-6 agents and/or who are chronically steroid dependent, is long-term stable steroid treatment superior to nonsteroid treatments (cyclophosphamide or abatacept or rituximab or IVIG or mesenchymal stem cell transplant or bone marrow transplant) for achievement of inactive disease, achievement of partial response, growth, ability to taper/discontinue steroids, and minimization of side effects/medication toxicity? | 138 |

JIA = juvenile idiopathic arthritis; MAS = macrophage activation syndrome; PICO = Patient/Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; MTX = methotrexate; IL-1 = interleukin-1; IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulin.

In Supplementary Appendix 3, on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42037/abstract.

Table 6.

Systemic JIA with MAS*

| Recommendation | Certainty of evidence | PICO evidence report(s) basis | Page no(s). of evidence tables† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formal recommendation deferred | Very low | PICO 24. In patients with Systemic JIA, does the presence of subclinical MAS alter the treatment paradigm? | 130 |

| IL-1 and IL-6 inhibitors are conditionally recommended over calcineurin inhibitors alone to achieve inactive disease and resolution of MAS. Glucocorticoids are conditionally recommended as part of initial treatment of systemic JIA with MAS. There is no preferred agent. |

Very low | PICO 25. In patients with Systemic JIA and overt MAS, is biologic therapy superior to calcineurin inhibitors for achievement of inactive disease and resolution of MAS? | 131–136 |

| Formal recommendation deferred | Very low | PICO 26. For nonresponse or partial response to biologic therapy, is addition of a calcineurin inhibitor superior to etoposide or IVIG or plasmapheresis for achievement of inactive disease and resolution of MAS? | 137–138 |

| Biologic DMARDs or conventional synthetic DMARDs are strongly recommended over long-term glucocorticoids for residual arthritis and incomplete response to IL-1 and/or IL-6 inhibitors. There is no preferred agent. |

Very low | PICO 27. In patients with Systemic JIA in whom inactive disease is not achieved despite treatment with both IL-1 and IL-6 agents and/or who are chronically steroid dependent, is long-term stable steroid treatment superior to nonsteroid treatments (cyclophosphamide or abatacept or rituximab or IVIG or mesenchymal stem cell transplant or bone marrow transplant) for achievement of inactive disease, achievement of partial response, growth, ability to taper/discontinue steroids, and minimization of side effects/medication toxicity? | 138 |

JIA = juvenile idiopathic arthritis; MAS = macrophage activation syndrome; PICO = Patient/Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes; IL-1 = interleukin-1; IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulin; DMARDs = disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

In Supplementary Appendix 3, on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42037/abstract.

Active oligoarthritis (Figure 1 and Table 3)

Figure 1.

Treatment algorithm for oligoarthritis.

Oligoarthritis refers to JIA presenting with involvement of ≤4 joints without systemic manifestations. It may include patients with different categories of JIA (10) but who share in common limited numbers of joints involved; guidance for patients with active uveitis, sacroiliitis, or enthesitis can be found in the 2019 guidelines (3,4). TMJ arthritis is discussed separately.

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

A trial of scheduled NSAIDs is conditionally recommended as part of initial therapy for active oligoarthritis.

NSAIDs have long been the cornerstone of treatment for oligoarthritis and can ease discomfort (11–13). However, the initial NSAID trial should be brief due to potential adverse effects (e.g., gastritis, bruising) and limited efficacy (unless inactive disease is achieved). Voting panelists could not agree on the appropriate duration of initial use before escalating therapy, as some panelists prefer that the use of NSAIDs be avoided altogether.

Glucocorticoids

Intraarticular glucocorticoids (IAGCs) are strongly recommended as part of initial therapy for active oligoarthritis.

Triamcinolone hexacetonide is strongly recommended as the preferred agent.

Although the evidence is of low quality, IAGCs are strongly recommended due to low potential of adverse effects and high likelihood of sustained response (14–16). Patients and caregivers agreed with regard to the utility of IAGC but voiced concerns over the need for sedation in younger children and associated risks.

Despite an overall grading of the evidence as low, the panel was convinced by published randomized trials and large observational studies (17–19) that triamcinolone hexacetonide results in more durable clinical responses than triamcinolone acetonide, leading to the strong recommendation. Triamcinolone hexacetonide has been unavailable in the US for several years. However, very recently, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has allowed the importation of one particular formulation of triamcinolone hexacetonide specifically for joint injections in patients with JIA to address this identified unmet medical need.

Oral glucocorticoids are conditionally recommended against as part of initial therapy for active oligoarthritis.

If, despite recommendations against, oral glucocorticoids are given to quickly alleviate severe symptoms when an IAGC is not available or feasible, or prior to the onset of action of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), treatment should be limited to the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration possible (20,21).

Conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs)

Conventional synthetic DMARDs are strongly recommended if there is an inadequate response to scheduled NSAIDs and/or IAGCs for active oligoarthritis.

Methotrexate is conditionally recommended as a preferred agent over leflunomide, sulfasalazine, or hydroxychloroquine (in that order).

Despite an absence of comparator trials, methotrexate is the preferred agent, given the preponderance of evidence showing its long-term safety and efficacy in children (22–24). Because the tolerability of methotrexate is variable, additional treatment options are provided (25–28).

With regard to the route of administration of methotrexate, the 2019 JIA guidelines conditionally recommended subcutaneous over oral administration for polyarthritis (3). This recommendation was conditional because the supporting evidence was of very low quality and patient preferences may guide choice of route of administration. There is little reason to suggest that methotrexate should be used differently in oligoarthritis than in polyarthritis.

Biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs)

Biologic DMARDs are strongly recommended if there is inadequate response to or intolerance of NSAIDs and/or IAGCs and at least 1 csDMARD for active oligoarthritis.

There is no preferred bDMARD.

Biologic DMARDs are preferred over combining csDMARDs or switching to a different csDMARD, due to a greater likelihood that bDMARDs will yield rapid and sustained improvement in JIA (29,30). While combination csDMARDs have been used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in adults, in children the combination appears to be less effective and less tolerable (31). For these reasons, this recommendation is strong.

Although tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) are the most commonly used bDMARDs in children (32–34), other bDMARDs of proven efficacy in the treatment of JIA may be used. In the absence of head-to-head trials in children with oligoarthritis (35), bDMARD selection may be driven by specific provider and patient/caregiver preferences and circumstances, with the exception of interleukin-1 (IL-1) inhibitors, which are preferentially used for the treatment of systemic JIA (29,36–38).

Risk factors for poor prognosis and disease activity measures

Consideration of risk factors for poor outcome (e.g., involvement of ankle, wrist, hip, sacroiliac joint, and/or TMJ, presence of erosive disease or enthesitis, delay in diagnosis, elevated levels of inflammation markers, symmetric disease) is conditionally recommended to guide treatment decisions.

Use of validated disease activity measures is conditionally recommended to guide treatment decisions, especially to facilitate treat-to-target approaches.

Treatment for oligoarthritis can and should be modified based on the involvement of specific joints or disease features (39,40). This could include rapid escalation of treatment (e.g., if there is TMJ involvement or erosive disease at presentation) or alternative medication choice (e.g., sulfasalazine or bDMARD rather than methotrexate for sacroiliitis) (3).

Voting panelists conditionally recommended formal assessment of disease activity using validated measures. There are several validated disease activity measures for childhood arthritis (41). The lack of demonstrated superiority of specific measures and the likelihood of future changes led voting panelists to defer stating formal preferences for particular measures. Measures that can be considered include Wallace preliminary criteria for Clinical Remission, ACR provisional criteria for inactive disease, Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS), and clinical JADAS, among others (42–46).

Treat-to-target approaches have been strongly endorsed for polyarticular JIA (47), and preliminary data have demonstrated feasibility as well as improved outcomes (48,49). Despite the limited number of studies in oligoarticular disease, one would expect a similar response. Presence of risk factors for poor outcomes may justify rapid escalation of treatment.

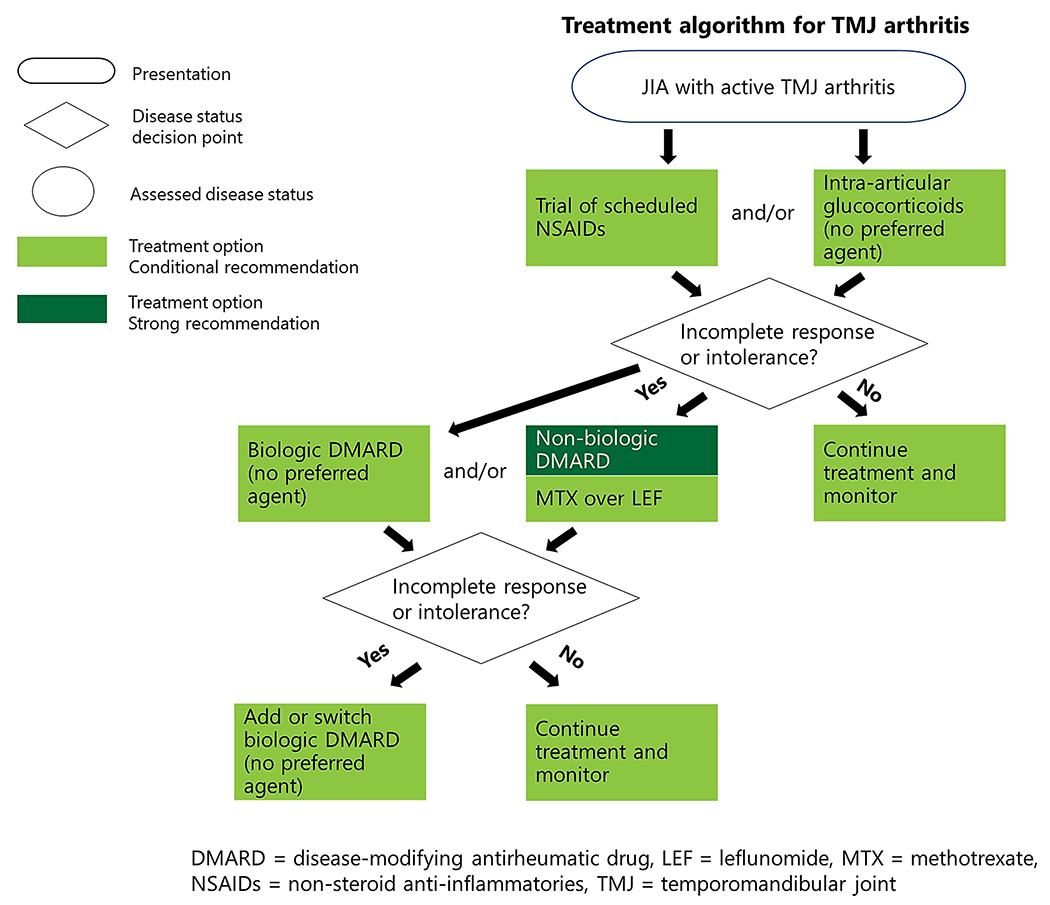

Active TMJ arthritis (Figure 2 and Table 4)

Figure 2.

Treatment algorithm for temporomandibular joint arthritis.

TMJ disease may be isolated or part of generalized arthritis. Treatment of TMJ arthritis is critical, as patients/caregivers noted high impact on oral health–related quality of life and challenges with diagnosis and effective pharmacologic treatment (50,51). In this guideline, therefore, treatment of TMJ arthritis is recommended regardless of presence of clinical symptoms. While NSAIDs and/or IAGCs may be sufficient treatment for some patients, rapid escalation to bDMARDs (potentially in combination with csDMARDs) is often appropriate despite limited evidence, given the impact and destructive nature of TMJ arthritis (52).

NSAIDs

A trial of scheduled NSAIDs is conditionally recommended as part of initial therapy for active TMJ arthritis.

NSAIDs have long been the cornerstone of treatment for JIA and can ease discomfort (11). However, the initial NSAID trial should be brief due to potential adverse effects (e.g., gastritis, bruising) and limited efficacy (unless inactive disease is achieved). Voting panelists could not agree on the appropriate duration of initial use before escalating therapy, as some panelists prefer that the use of NSAIDs be avoided altogether.

Glucocorticoids

IAGCs are conditionally recommended as part of initial therapy for active TMJ arthritis.

There is no preferred agent.

IAGCs may alleviate joint symptoms and help restore function. This recommendation is conditional, as there have been unique TMJ-specific serious adverse events, including heterotopic ossification and impaired growth (52–55). Therefore, IAGCs for TMJ arthritis should be used sparingly for symptomatic children, preferably those who are skeletally mature (53–56). There are no comparative data between different IAGC formulations for TMJ injections.

Oral glucocorticoids are conditionally recommended against as part of initial therapy for active TMJ arthritis.

If, despite recommendations against, oral glucocorticoids are given to quickly alleviate severe symptoms prior to the onset of action of DMARDs, treatment should be limited to the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration possible (20).

Conventional synthetic DMARDs

Conventional synthetic DMARDs are strongly recommended for inadequate response to or intolerance of NSAIDs and/or IAGCs for active TMJ arthritis.

Methotrexate is conditionally recommended as a preferred agent over leflunomide.

The TMJ is a high-risk joint due to major impact on activities of daily living, and thus, early use of csDMARD therapy is encouraged. The limited available evidence supports the use of methotrexate (57). However, because not all patients tolerate methotrexate well, leflunomide is recommended as an alternative, if needed.

Biologic DMARDs

Biologic DMARDs are conditionally recommended for inadequate response to or intolerance of NSAIDs and/or IAGCs and at least 1 csDMARD for active TMJ arthritis.

There is no preferred bDMARD.

Voting panelists deferred recommending a specific bDMARD because current studies of TMJ arthritis have been small and observational (52,58). TNFi treatment has been most commonly used. As noted above, the use of IL-1 inhibitors is restricted to the treatment of systemic JIA.

Systemic JIA with and without MAS (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Treatment algorithm for systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Systemic JIA is distinct from all other categories of JIA due to fever, rash, and visceral involvement and is considered by some to be an autoinflammatory disorder (59). Disease pathogenesis and cytokine involvement in systemic JIA are different than in other JIA categories (60–62). Up to 40% of cases of systemic JIA are associated with MAS, a secondary hemophagocytic syndrome that is a life-threatening complication requiring urgent recognition and treatment. MAS presents with fevers, high ferritin levels, cytopenias, elevated liver enzyme levels, low fibrinogen levels, and high triglyceride levels (63,64). As it may occur at any point during the disease course, careful monitoring is necessary for children with or without MAS at presentation.

Systemic JIA without MAS: initial therapy (Table 5)

Biologic DMARDs

Biologic DMARDS (IL-1 and IL-6 inhibitors) are conditionally recommended as initial monotherapy for systemic JIA without MAS.

There is no preferred agent.

IL-1 and IL-6 inhibitors are extremely effective and well-tolerated treatments for systemic JIA (60–62) and have been rapidly adopted in clinical practice (65,66). Use of IL-1 and IL-6 inhibitors to treat systemic JIA has allowed for marked reduction in glucocorticoid use (60,61,67). Patients/caregivers agreed with this recommendation, given historical delays and limits in clinical response and toxicities from other medications before the bDMARD era.

Some voting panelists preferred starting with a short-acting agent such as anakinra, but in the absence of controlled studies, no preferred agent was endorsed. Patients/caregivers noted preference for fewer injections, if possible. As response to individual agents is variable, switching among and between IL-1 and IL-6 inhibitors when needed due to lack of efficacy or poor tolerability is appropriate.

Concerns were expressed regarding a highly fatal lung disease observed in some children with systemic JIA, most of whom were treated with bDMARDs. Observed risk factors include younger age with MAS, a history of reactions to tocilizumab, and trisomy 21 (68,69). The exact etiology of systemic JIA–associated lung disease and recommendations for screening remain under investigation. Affected children often present with acute digital clubbing, which should raise immediate concern (68,69). However, voting panelists noted the need to balance the effectiveness and relative safety of bDMARDs with the rarity of this serious outcome. Voting panelists were also motivated by the extent of morbidity from undertreated systemic JIA and glucocorticoid-associated toxicities before the bDMARD era (70,71).

NSAIDs

NSAIDs are conditionally recommended as initial monotherapy for systemic JIA without MAS.

Studies suggest that a small proportion of patients with systemic JIA will respond to NSAIDs alone (72). Patients/caregivers agreed with a short trial of NSAIDs for those children. If clinical response is not rapid and complete, rapid escalation of therapy is recommended. Voting panelists could not agree on the appropriate duration of initial use before escalating therapy, as many panelists prefer that the use of NSAIDs be avoided altogether for systemic JIA.

Glucocorticoids

Oral glucocorticoids are conditionally recommended against as initial monotherapy for systemic JIA without MAS.

In most cases, oral glucocorticoids should not be used as initial monotherapy in patients with systemic JIA without MAS and, if used, should be limited to the lowest effective dosage for the shortest duration possible. This recommendation is conditional, as bDMARDs may not always be immediately available, and glucocorticoids may help control systemic and joint manifestations until IL-1 or IL-6 inhibitors can be started.

Conventional synthetic DMARDs

Conventional synthetic DMARDs are strongly recommended against as initial monotherapy for systemic JIA without MAS.

This recommendation is strong despite limited evidence, as the Voting Panel noted multiple small studies of systemic JIA that documented lack of efficacy at controlling systemic features that are typically present at onset of disease, leading to a continued need for glucocorticoids (66,73). Conventional synthetic DMARDs in combination with bDMARDs can be considered for children with prominent arthritis (74). In areas where biologic therapy is not rapidly attainable, thalidomide has been used to treat systemic JIA (75). However, given ready bDMARD availability in North America and risks of thalidomide toxicity, use of thalidomide was not considered as part of this guideline.

Systemic JIA without MAS: subsequent therapy (Table 5)

IL-1 and IL-6 inhibitors are strongly recommended over a single or combination of csDMARDs for inadequate response to or intolerance of NSAIDs and/or glucocorticoids for systemic JIA without MAS.

Most physicians and patients/caregivers preferred quickly starting IL-1 or IL-6 inhibitors for insufficient response to NSAIDs or glucocorticoids (66). Panel members were persuaded by trials that documented resolution of systemic signs and ability to discontinue glucocorticoids (60,76–78).

Biologic DMARDs or conventional synthetic DMARDs are strongly recommended over long-term glucocorticoids for residual arthritis and incomplete response to IL-1 and/or IL-6 inhibitors.

There is no preferred agent.

Given the potential toxicities from long-term use of glucocorticoids (20), patients should receive steroid-sparing treatments for residual arthritis. There are many options (e.g., adding methotrexate, switching to abatacept or a TNFi), and ample evidence supports the use of DMARDs for systemic JIA–associated synovitis (23,79).

Systemic JIA with MAS: initial therapy (Table 6)

Infections can trigger MAS; therefore, all persons with MAS should be evaluated for infection concurrently with or prior to initiation of therapy (80,81).

Biologic DMARDs

IL-1 or IL-6 inhibitors are conditionally recommended over calcineurin inhibitors alone to achieve inactive disease and resolution of MAS for systemic JIA with MAS.

There is no preferred agent.

IL-1 and IL-6 inhibitors have proven to be very helpful in the treatment of systemic JIA and MAS (82–84). Some voting panelists noted that monotherapy may not be sufficient for severely ill patients (83). Biologic DMARDs combined with glucocorticoids and calcineurin inhibitors may be necessary to control MAS in some patients (85).

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids are conditionally recommended as part of initial treatment of systemic JIA with MAS.

The benefits of glucocorticoids for MAS often outweigh their risks, even in patients whose MAS is triggered by infection. Systemic glucocorticoids may be necessary for severely ill patients because they can have a rapid onset of action. However, although treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids may be required for disease control, subsequent glucocorticoid therapy should be limited to the lowest effective dosage for the shortest duration possible. Longer-term glucocorticoid therapy in children is not appropriate because of its effects on bone health and growth (20).

Systemic JIA with MAS: subsequent therapy (Table 6)

Biologic DMARDS or csDMARDs are strongly recommended over long-term glucocorticoids for residual arthritis and incomplete response to IL-1 and/or IL-6 inhibitors.

Inactive systemic JIA with or without history of MAS (Table 7)

Tapering and discontinuing glucocorticoids is strongly recommended after inactive disease has been attained in systemic JIA.

The risk of flare from systemic JIA that is well controlled is considerably outweighed by possible harms from long-term glucocorticoid use, even at low doses (86), accounting for this strong recommendation. If a patient is receiving both DMARDs and glucocorticoids, systemic glucocorticoids should be tapered and discontinued first before attempting to taper bDMARDs or csDMARDs. It is unclear how soon or rapidly these can be safely discontinued in patients with inactive systemic JIA.

Tapering and discontinuing bDMARDs is conditionally recommended after inactive disease has been attained in systemic JIA.

In children with systemic JIA whose disease is inactive, it may be possible to maintain this inactive disease state with lower doses of, or discontinuation of, bDMARDs (74,87). It is unclear how soon after achievement of inactive disease these can be tapered. No method of tapering is specified (e.g., decreasing dosage versus increasing intervals between doses) given lack of evidence (86), but patients/caregivers tended to prefer increasing intervals.

DISCUSSION

The recommendations presented herein are a companion to those published in 2019 (3,4) and cover areas not previously addressed: oligoarthritis, TMJ arthritis, and systemic JIA with and without MAS. In many ways, one must view this guideline as a road map for future study. Most of the available evidence for the relevant PICO questions was of very low quality, contributing to 16 of the 25 recommendations being conditional. None of the recommendations were supported by moderate- or high-quality evidence. Similar to the 2019 guidelines, recommendations are grouped based on disease phenotype and not by specific classification criteria, reflecting clinical practice, in which disease characteristics, severity, and risk of damage generally drive treatment decisions. These recommendations differ quite substantially from those published in 2011 and 2013 (1,2), reflecting increased experience with and availability of bDMARDs as well as a deeper understanding of JIA pathogenesis and long-term risks of undertreatment.

The Voting Panel and Patient/Caregiver Panel both engaged in vigorous discussions over the use of NSAIDs and oral glucocorticoids (88) in the treatment of JIA, regardless of phenotype. Given the availability of safer, effective alternatives, both panels agreed that these medications should be used sparingly and largely as a bridge until more definitive treatment is available. This is a marked change from previous clinical practice, in which both were mainstays of treatment and subsequent risk of chronic disability was high (89,90).

Another major change in recommendations for the treatment of systemic JIA is the use of bDMARDs as initial treatment or upon inadequate response to a short course of NSAIDs. The addition of csDMARDs is recommended only for persistent synovitis despite treatment with bDMARDs. This recommendation reflects growing understanding about the roles of specific cytokines in systemic JIA and the ability to induce remission with targeted therapy against IL-6 and IL-1 (62,74,91). Reports of a highly fatal lung disease in some bDMARD-treated young children with systemic JIA (68,69) temper this enthusiasm, and additional investigation is needed to determine what role, if any, bDMARDs play in the pathogenesis of this complication.

This guideline’s focus on oligoarthritis complements previously published recommendations for polyarthritis (3). However, it was clear in Voting Panel discussions that the number of involved joints alone was insufficient to tailor treatment decisions. Specific involvement of key joints (e.g., TMJ, wrist, sacroiliac, hip, and ankle) and other features (e.g., erosions) were considered reasonable justification for early escalation of therapy (92). This approach is reflected in a distinct set of recommendations specifically addressing TMJ arthritis.

The use of IAGCs was extensively discussed. Recommendations from 2011 and 2019 to preferentially use triamcinolone hexacetonide for oligoarthritis (1,3) were reaffirmed, while no specific formulation for TMJ IAGC injection was noted. Triamcinolone hexacetonide has been shown to be superior to alternative injectable glucocorticoids in achieving and maintaining remission in children with JIA (17–19). Triamcinolone hexacetonide has been commercially unavailable in the US for many years, forcing physicians to consider less effective, more toxic, or more costly alternatives. However, very recently the FDA allowed the importation of one particular formulation of triamcinolone hexacetonide specifically for joint injections in patients with JIA (93) to address an identified unmet medical need.

There is much that remains to be learned. Studies must be performed to obtain high-quality data to fill in the evidentiary gaps (Supplementary Appendix 7, available on the Arthritis & Rheumatology website at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.42037/abstract). There remain important areas with little or no evidence to guide management, suggesting an agenda for future research. Head-to-head trials are needed to understand the optimal order and roles of csDMARDs and bDMARDs for children with JIA. We need improved understanding of which class of medication is best for a particular child, allowing for more precise treatment and less time before remission is attained. Biosimilars were not addressed in this guideline, as these medications were not included in the literature review, and there was no available evidence assessing their use in JIA. More widespread use of biosimilars will add more questions about their relative safety and effectiveness in children who start or switch to them for JIA treatment.

Patient/caregiver input was instrumental in creating these recommendations. Several major themes emerged from their participation. Patients/caregivers stressed the need for individualizing treatments because what works for one does not work for all (94). To facilitate individualization, no rigid time frames were required for an advancement of treatment. Moving quickly may be needed for a patient whose condition is rapidly worsening, while moving more slowly may be appropriate for one whose condition has improved substantially but not fully. Panel participants emphasized the critical importance of shared decision-making that considers patients’ and caregivers’ values, goals, and preferences (95). The depth and breadth of the impact of JIA on the lives and well-being of affected children and their families cannot be overstated (96,97). It is hoped that in the future, more effective, reliable treatments for this disease will be available (98).

This guideline breaks new ground in recommending treatment withdrawal for children with systemic JIA, who may have lower risks of flare than are associated with other forms of JIA (99,100). As we look toward the future, we can only hope that similar recommendations around tapering medications can be made for every JIA category. There is a need for biomarkers that can help distinguish disease that still requires treatment from that which has completely resolved, as currently the risk of relapse remains high upon medication tapering.

The low quality of evidence supporting these recommendations underscores the importance of clinical judgment and shared decision-making in everyday care of individuals with JIA. Similarly, this guideline and the many uncertainties acknowledged herein represent a powerful reminder of the need for more high-quality evidence to support (or refute) current practices and to improve the management of JIA and well-being of all individuals living with the disease.

Supplementary Material

Guidelines and recommendations developed and/or endorsed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) are intended to provide guidance for patterns of practice and not to dictate the care of a particular patient. The ACR considers adherence to the recommendations within this guideline to be voluntary, with the ultimate determination regarding their application to be made by the physician in light of each patient’s individual circumstances. Guidelines and recommendations are intended to promote beneficial or desirable outcomes but cannot guarantee any specific outcome. Guidelines and recommendations developed and endorsed by the ACR are subject to periodic revision as warranted by the evolution of medical knowledge, technology, and practice. ACR recommendations are not intended to dictate payment or insurance decisions, and drug formularies or other third-party analyses that cite ACR guidelines should state this. These recommendations cannot adequately convey all uncertainties and nuances of patient care.

The ACR is an independent, professional, medical and scientific society that does not guarantee, warrant, or endorse any commercial product or service.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jennifer Horonjeff who (along with author Katherine Murphy) participated in the Patient Panel meeting. We thank the ACR staff, including Regina Parker for assistance in coordinating the administrative aspects of the project and Cindy Force for assistance with manuscript preparation. We thank Janet Waters for assistance in developing the literature search strategy as well as performing the initial literature search and update searches.

Supported by the American College of Rheumatology. Dr. Horton’s work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, NIH (grant K23-AR-070286). Dr. Ombrello’s work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, NIH (grant AR-041198).

Footnotes

Author disclosures are available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/action/downloadSupplement?doi=10.1002%2Fart.42037&file=art42037-sup-0001-Disclosureform.pdf.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beukelman T, Patkar NM, Saag KG, Tolleson-Rinehart S, Cron RQ, DeWitt EM, et al. 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: initiation and safety monitoring of therapeutic agents for the treatment of arthritis and systemic features. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011; 63:465–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ringold S, Weiss PF, Beukelman T, DeWitt EM, Ilowite NT, Kimura Y, et al. 2013 update of the 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: recommendations for the medical therapy of children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and tuberculosis screening among children receiving biologic medications. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2499–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringold S, Angeles-Han ST, Beukelman T, Lovell D, Cuello CA, Becker ML, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: therapeutic approaches for non-systemic polyarthritis, sacroiliitis, and enthesitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:846–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angeles-Han ST, Ringold S, Beukelman T, Lovell D, Cuello CA, Becker ML, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the screening, monitoring, and treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis–associated uveitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:864–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onel KB, Shenoi S. 2021. American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA): therapeutic approaches for oligoarthritis, temporomandibular joint arthritis (TMJ), and systemic JIA, medication monitoring, immunizations and non-pharmacologic therapies. Presented at ACR Convergence; 2020 November 3–10; Atlanta, Georgia. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrews JC, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Pottie K, Meerpohl JJ, Coello PA, et al. GRADE guidelines. 15. Going from evidence to recommendation—determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:726–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010;182:E839–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onel KB, Horton DB, Lovell DJ, Shenoi S, Cuello CA, Angeles-Han ST, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: recommendations for nonpharmacologic therapies, medication monitoring, immunizations, and imaging. Arthritis Rheumatol 2022. doi: 10.1002/art.42036. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petty RE, Southwood TR, Baum J, Bhettay E, Glass DN, Manners P, et al. Revision of the proposed classification criteria for juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Durban, 1997. J Rheumatol 1998;25:1991–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chhabra A, Oen K, Huber AM, Shift NJ, Boire G, Benseler SM, et al. Real-world effectiveness of common treatment strategies for juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from a Canadian cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020;72:897–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brik R, Gepstein V, Berkovitz D. Low-dose methotrexate treatment for oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis nonresponsive to intra-articular corticosteroids. Clin Rheumatol 2005;24:612–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kvien TK, Hoyeraal HM, Sandstad B. Naproxen and acetylsalicylic acid in the treatment of pauciarticular and polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: assessment of tolerance and efficacy in a singlecentre 24-week double-blind parallel study. Scand J Rheumatol 1984;13:342–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato JD, Fernandes TA, Nascimento CB, Corrente JE, Saad-Magalhaes C. Probability of remission of juvenile idiopathic arthritis following treatment with steroid joint injection. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014;32:291–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marti P, Molinari L, Bolt IB, Seger R, Saurenmann RK. Factors influencing the efficacy of intra-articular steroid injections in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Eur J Pediatr 2008;167:425–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breit W, Frosch M, Meyer U, Heinecke A, Ganser G. A subgroup-specific evaluation of the efficacy of intraarticular triamcinolone hexacetonide in juvenile chronic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2000;27: 2696–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zulian F, Martini G, Gobber D, Agosto C, Gigante C, Zacchello F. Comparison of intra-articular triamcinolone hexacetonide and triamcinolone acetonide in oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:1254–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zulian F, Martini G, Gobber D, Plebani M, Zacchello F, Manners P. Triamcinolone acetonide and hexacetonide intra-articular treatment of symmetrical joints in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a double-blind trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:1288–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eberhard BA, Sison MC, Gottlieb BS, Ilowite NT. Comparison of the intraarticular effectiveness of triamcinolone hexacetonide and triamcinolone acetonide in treatment of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2004;31:2507–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guzman J, Kerr T, Ward LM, Ma J, Oen K, Rosenberg AM, et al. Growth and weight gain in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the ReACCh-Out cohort. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2017;15:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sadeghi PA, Yahya A, Ziaee V, Moayeri H. Adrenal insufficiency in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) treated with prednisolone. J Compr Ped 2019;10:e64681. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravelli A, Davi S, Bracciolini G, Pistorio A, Consolaro A, van Dijkhuizen EH, et al. Intra-articular corticosteroids versus intra-articular corticosteroids plus methotrexate in oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet 2017;389:909–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albarouni M, Becker I, Horneff G. Predictors of response to methotrexate in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2014;12:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bava C, Mongelli F, Pistorio A, Bertamino M, Bracciolini G, Dalpra S, et al. A prediction rule for lack of achievement of inactive disease with methotrexate as the sole disease-modifying antirheumatic therapy in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2019;17:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franova J, Fingerhutova S, Kobrova K, Srp R, Nemcova D, Hoza J, et al. Methotrexate efficacy, but not its intolerance, is associated with the dose and route of administration. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2016;14:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imundo LF, Jacobs JC. Sulfasalazine therapy for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1996;23:360–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foeldvari I, Wierk A. Effectiveness of leflunomide in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in clinical practice. J Rheumatol 2010;37: 1763–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haapasaari J, Kautiainen H, Isomaki H, Hakala M. Hydroxychloroquine does not decrease serum methotrexate concentrations in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis [letter]. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1621–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexeeva E, Dvoryakovskaya T, Denisova R, Sleptsova T, Isaeva K, Chomahidze A, et al. Comparative analysis of the etanercept efficacy in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis under the age of 4 years and children of older age groups using the propensity score matching method. Mod Rheumatol 2019;29:848–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anink J, Otten MH, Prince FH, Hoppenreijs EP, Wulffraat NM, Swart JF, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-blocking agents in persistent oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the Dutch Arthritis and Biologicals in Children Register. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:712–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tynjala P, Vahasalo P, Tarkiainen M, Kroger L, Aalto K, Malin M, et al. Aggressive combination drug therapy in very early polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ACUTE-JIA): a multicentre randomised open-label clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1605–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff A, Cawkwell GD, Silverman ED, Nocton JJ, et al. , Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. Etanercept in children with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2000;342:763–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mannion ML, Xie F, Horton DB, Ringold S, Correll CK, Dennos A, et al. Biologic switching among non-systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients: a cohort study in the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance Registry. J Rheumatol 2020;48:1322–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armaroli G, Klein A, Ganser G, Ruehlmann MJ, Dressler F, Hospach A, et al. Long-term safety and effectiveness of etanercept in JIA: an 18-year experience from the BiKeR registry. Arthritis Res Ther 2020;22:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horneff G, Klein A, Klotsche J, Minden K, Huppertz HI, Weller-Heinemann F, et al. Comparison of treatment response, remission rate and drug adherence in polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients treated with etanercept, adalimumab or tocilizumab. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minden K, Horneff G, Niewerth M, Seipelt E, Aringer M, Aries P, et al. Time of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug start in juvenile idiopathic arthritis and the likelihood of a drug-free remission in young adulthood. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019;71:471–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kearsley-Fleet L, Davies R, Lunt M, Southwood TR, Hyrich KL. Factors associated with improvement in disease activity following initiation of etanercept in children and young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology Etanercept Cohort Study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55:840–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ilowite N, Porras O, Reiff A, Rudge S, Punaro M, Martin A, et al. Anakinra in the treatment of polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: safety and preliminary efficacy results of a randomized multicenter study. Clin Rheumatol 2009;28:129–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rypdal V, Arnstad ED, Aalto K, Berntson L, Ekelund M, Fasth A, et al. Predicting unfavorable long-term outcome in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the Nordic cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rypdal V, Guzman J, Henrey A, Loughin T, Glerup M, Arnstad ED, et al. Validation of prediction models of severe disease course and non-achievement of remission in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: part 1—results of the Canadian model in the Nordic cohort. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21:270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trincianti C, Consolaro A. Outcome measures for juvenile idiopathic arthritis disease activity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020;72 Suppl:150–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallace CA, Huang B, Bandeira M, Ravelli A, Giannini EH. Patterns of clinical remission in select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3554–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wallace CA, Giannini EH, Huang B, Itert L, Ruperto N, for the Childhood Arthritis Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA), the Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group (PRCSG), and the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO). American College of Rheumatology provisional criteria for defining clinical inactive disease in select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:929–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Consolaro A, Ruperto N, Bazso A, Pistorio A, Magni-Manzoni S, Filocamo G, et al. Development and validation of a composite disease activity score for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:658–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McErlane F, Beresford MW, Baildam EM, Chieng SE, Davidson JE, Foster HE, et al. Validity of a three-variable Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score in children with new-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1983–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tibaldi J, Pistorio A, Aldera E, Puzone L, El Miedany Y, Pal P, et al. Development and initial validation of a composite disease activity score for systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59:3505–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ravelli A, Consolaro A, Horneff G, Laxer RM, Lovell DJ, Wulffraat NM, et al. Treating juvenile idiopathic arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77:819–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klein A, Minden K, Hospach A, Foeldvari I, Weller-Heinemann F, Trauzeddel R, et al. Treat-to-target study for improved outcome in polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:969–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buckley L, Ware E, Kreher G, Wiater L, Mehta J, Burnham JM. Outcome monitoring and clinical decision support in polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2020;47:273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahimi H, Twilt M, Herlin T, Spiegel L, Pedersen TK, Kuseler A, et al. Orofacial symptoms and oral health-related quality of life in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a two-year prospective observational study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2018;16:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frid P, Nordal E, Bovis F, Giancane G, Larheim TA, Rygg M, et al. Temporomandibular joint involvement in association with quality of life, disability, and high disease activity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69:677–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bollhalder A, Patcas R, Eichenberger M, Muller L, Schroeder-Kohler S, Saurenmann RK, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging followup of temporomandibular joint inflammation, deformation, and mandibular growth in juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients receiving systemic treatment. J Rheumatol 2020;47:909–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stoll ML, Amin D, Powell KK, Poholek CH, Strait RH, Aban I, et al. Risk factors for intraarticular heterotopic bone formation in the temporomandibular joint in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2018;45:1301–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ringold S, Thapa M, Shaw EA, Wallace CA. Heterotopic ossification of the temporomandibular joint in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1423–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lochbuhler N, Saurenmann RK, Muller L, Kellenberger CJ. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of temporomandibular joint involvement and mandibular growth following corticosteroid injection in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2015;42:1514–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Resnick CM, Vakilian PM, Kaban LB, Peacock ZS. Quantifying the effect of temporomandibular joint intra-articular steroid injection on synovial enhancement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016;74:2363–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ince DO, Ince A, Moore TL. Effect of methotrexate on the temporomandibular joint and facial morphology in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000;118:75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stoustrup P, Twilt M, Herlin T. Systemic treatment for temporomandibular joint arthritis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2020; 47:793–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ombrello MJ, Arthur VL, Remmers EF, Hinks A, Tachmazidou I, Grom AA, et al. Genetic architecture distinguishes systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis from other forms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: clinical and therapeutic implications. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:906–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Benedetti F, Brunner HI, Ruperto N, Kenwright A, Wright S, Calvo I, et al. Randomized trial of tocilizumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2385–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruperto N, Brunner HI, Quartier P, Constantin T, Wulffraat N, Horneff G, et al. Two randomized trials of canakinumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2396–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pascual V, Allantaz F, Arce E, Punaro M, Banchereau J. Role of interleukin-1 (IL-1) in the pathogenesis of systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis and clinical response to IL-1 blockade. J Exp Med 2005;201:1479–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ravelli A, Minoia F, Davi S, Horne A, Bovis F, Pistorio A, et al. 2016 classification criteria for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology/Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:566–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Minoia F, Davi S, Horne A, Demirkaya E, Bovis F, Li C, et al. Clinical features, treatment, and outcome of macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a multinational, multicenter study of 362 patients. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66:3160–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.DeWitt EM, Kimura Y, Beukelman T, Nigrovic PA, Onel K, Prahalad S, et al. Consensus treatment plans for new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1001–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kimura Y, Grevich S, Beukelman T, Morgan E, Nigrovic PA, Mieszkalski K, et al. Pilot study comparing the Childhood Arthritis & Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis consensus treatment plans. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2017;15:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vastert SJ, de Jager W, Noordman BJ, Holzinger D, Kuis W, Prakken BJ, et al. Effectiveness of first-line treatment with recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in steroid-naive patients with new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results of a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:1034–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schulert GS, Yasin S, Carey B, Chalk C, Do T, Schapiro AH, et al. Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated lung disease: characterization and risk factors. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1943–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saper VE, Chen G, Deutsch GH, Guillerman RP, Birgmeier J, Jagadeesh K, et al. Emergent high fatality lung disease in systemic juvenile arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:1722–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bsila RS, Inglis AE, Ranawat CS. Joint replacement surgery in patients under thirty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1976;58:1098–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mertelsmann-Voss C, Lyman S, Pan TJ, Goodman SM, Figgie MP, Mandl LA. US trends in rates of arthroplasty for inflammatory arthritis including rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:1432–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sura A, Failing C, Sturza J, Stannard J, Riebschleger M. Patient characteristics associated with response to NSAID monotherapy in children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2018;16:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Woo P, Southwood TR, Prieur AM, Doré CJ, Grainger J, David J, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of low-dose oral methotrexate in children with extended oligoarticular or systemic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1849–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ter Haar NM, van Dijkhuizen EHP, Swart JF, van Royen-Kerkhof A, El Idrissi A, Leek AP, et al. Treatment to target using recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist as first-line monotherapy in new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from a five-year follow-up study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1163–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lehman TJ, Schechter SJ, Sundel RP, Oliveira SK, Huttenlocher A, Onel KB. Thalidomide for severe systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a multicenter study. J Pediatr 2004;145:856–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ruperto N, Quartier P, Wulffraat N, Woo P, Ravelli A, Mouy R, et al. A phase II, multicenter, open-label study evaluating dosing and preliminary safety and efficacy of canakinumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis with active systemic features. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64:557–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff AO, Kimura Y, Li S, Hashkes PJ, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of rilonacept in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2486–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Quartier P, Allantaz F, Cimaz R, Pillet P, Messiaen C, Bardin C, et al. A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ANAJIS trial). Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:747–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Otten MH, Prince FH, Anink J, Ten Cate R, Hoppenreijs EP, Armbrust W, et al. Effectiveness and safety of a second and third biological agent after failing etanercept in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the Dutch National ABC Register. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:721–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Davies SV, Dean JD, Wardrop CA, Jones JH. Epstein-Barr virus-associated haemophagocytic syndrome in a patient with juvenile chronic arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 1994;33:495–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McPeake JR, Hirst WJ, Brind AM, Williams R. Hepatitis A causing a second episode of virus-associated haemophagocytic lymphohistio-cytosis in a patient with Still’s disease. J Med Virol 1993;39:173–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Aytac S, Batu ED, Unal S, Bilginer Y, Cetin M, Tuncer M, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome in children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int 2016;36:1421–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Eloseily EM, Weiser P, Crayne CB, Haines H, Mannion ML, Stoll ML, et al. Benefit of anakinra in treating pediatric secondary hemophago-cytic lymphohistiocytosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72:326–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ohmura SI, Uehara K, Yamabe T, Tamechika S, Maeda S, Naniwa T. Successful use of short-term add-on tocilizumab for refractory adult-onset still’s disease with macrophage activation syndrome despite treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids, cyclosporine, and etopo-side. Mod Rheumatol Case Rep 2020;4:202–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sonmez HE, Demir S, Bilginer Y, Ozen S. Anakinra treatment in macrophage activation syndrome: a single center experience and systemic review of literature. Clin Rheumatol 2018;37:3329–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shenoi S, Nanda K, Schulert GS, Bohnsack JF, Cooper AM, Edghill B, et al. Physician practices for withdrawal of medications in inactive systemic juvenile arthritis, Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) survey. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2019;17:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Quartier P, Alexeeva E, Tamas C, Chasnyk V, Wulffraat N, Palmblad K, et al. Tapering canakinumab monotherapy in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis in clinical remission: results from an open-label, randomized phase IIIb/IV study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;73:336–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rice JB, White AG, Scarpati LM, Wan G, Nelson WW. Long-term systemic corticosteroid exposure: a systematic literature review. Clin Ther 2017;39:2216–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zak M, Pedersen FK. Juvenile chronic arthritis into adulthood: a long-term follow-up study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39: 198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oen K, Malleson PN, Cabral DA, Rosenberg AM, Petty RE, Cheang M. Disease course and outcome of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in a multicenter cohort. J Rheumatol 2002;29:1989–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yokota S, Imagawa T, Mori M, Miyamae T, Aihara Y, Takei S, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebocontrolled, withdrawal phase III trial. Lancet 2008;371:998–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Al-Matar MJ, Petty RE, Tucker LB, Malleson PN, Schroeder ML, Cabral DA. The early pattern of joint involvement predicts disease progression in children with oligoarticular (pauciarticular) juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:2708–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.US Food and Drug Administration. Current and resolved drug shortages and discontinuations reported to FDA: triamcinolone hexacetonide. URL: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scrpts/drugshortages/dsp_ActiveIngredientDetails.cfm?AI=Triamcinolone%20Hexacetonide%20Injectable%20Suspension%20(Aristospan)&st=c.

- 94.Lipstein EA, Muething KA, Dodds CM, Britto MT. “I’m the one taking it”: adolescent participation in chronic disease treatment decisions. J Adolesc Health 2013;53:253–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lipstein EA, Lovell DJ, Denson LA, Kim SC, Spencer C, Britto MT. Parents’ information needs and influential factors when making decisions about TNF-α inhibitors. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2016; 14:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Foster HE, Marshall N, Myers A, Dunkley P, Griffiths ID. Outcome in adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a quality of life study. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:767–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]