Abstract

Background:

Patients eligible for lung cancer screening (LCS) are those at high risk of lung cancer due to their smoking histories and age. While screening for LCS is effective in lowering lung cancer mortality, primary care providers are challenged to meet beneficiary eligibility for LCS from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, including a patient counseling and shared decision-making (SDM) visit with the use of patient decision aid(s) prior to screening.

Methods:

We will use an effectiveness-implementation type I hybrid design to: 1) identify effective, scalable smoking cessation counseling and SDM interventions that are consistent with recommendations, can be delivered on the same platform, and are implemented in real-world clinical settings; 2) examine barriers and facilitators of implementing the two approaches to delivering smoking cessation and SDM for LCS; and 3) determine the economic implications of implementation by assessing the healthcare resources required to increase smoking cessation for the two approaches by delivering smoking cessation within the context of LCS. Providers from different healthcare organizations will be randomized to usual care (providers delivering smoking cessation and SDM on site) vs. centralized care (smoking cessation and SDM delivered remotely by trained counselors). The primary trial outcomes will include smoking abstinence at 12-weeks and knowledge about LCS measured at 1-week after baseline.

Conclusion:

This study will provide important new evidence about the effectiveness and feasibility of a novel care delivery model for addressing the leading cause of lung cancer deaths and supporting high-quality decisions about LCS.

Trial registration:

BACKGROUND

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in February 2015 added lung cancer screening (LCS) with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) as a covered service for high-risk persons with a heavy smoking history and 55–77 years of age.1 They provided specific beneficiary eligibility criteria for screening with LDCT that included patient counseling about smoking cessation and shared decision making (SDM) with the use of patient decision aids prior to screening.1

There is a gap in our understanding about how best to implement effective strategies for the required smoking cessation counseling and SDM visit for LCS.2–17 Decision making about LCS provides an opportunity to deliver evidence-based smoking cessation treatments to an engaged audience of persons who smoke and are at high risk for lung cancer. However, considerable discrepancies already exist among primary care providers (PCPs) in the delivery of guideline-based smoking cessation treatment. Evidence from the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) showed that while providers typically advised their patients who smoke to quit, the majority failed to engage in further supportive actions18 recommended by smoking cessation guidelines.19 An alternative approach to meeting the counseling and SDM for LCS is a centralized care model where persons who currently smoke are referred to a dedicated tobacco treatment program (TTP) where they receive both the SDM for LCS and smoking cessation counseling prior to their scheduled visit with a PCP.

The primary aim of this study will be to compare the effectiveness of PCP delivering guideline-based smoking cessation and SDM versus certified tobacco treatment specialists, hereafter referred to as TTP counselors, delivering remote smoking cessation and SDM on smoking abstinence and knowledge of LCS. The study will also examine the quality of these discussions. Our secondary aims will be to evaluate the reach, acceptability, feasibility, and fidelity of the two strategies. We will also assess the budgetary impact and cost-effectiveness of the two strategies.

METHODS

The report of this protocol follows Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI),20 Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist of information to include when reporting a cluster randomized trial,21 the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR),22 and the reporting guidelines for implementation and operational research.23 The reporting of cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis follows the good research practice guide published by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR).24–27

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of The University of Texas, MD Anderson Cancer Center. We will request reciprocity agreements for participating health care organizations.

Framework

Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) will guide this study’s implementation strategies and evaluation.28 PRISM examines how the program or intervention design, recipients, implementation and sustainability infrastructure, and the external environment influences adoption, implementation (fidelity), and maintenance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Practical, Robust, Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM).

The PRISM model identifies potential predictors of implementation success and effectiveness outcomes. The counseling and SDM visit (intervention) will impact recipients and vice-versa. The implementation and sustainability infrastructure, recipients, and external environment all impact each other and whether the intervention is adopted, implemented with fidelity, and sustained. We will evaluate the reach and effectiveness of our intervention and implementation strategy. The boxes outlined in bold will serve as targets for the selected implementation strategies.

Design

We will use an effectiveness-implementation type I hybrid study29 to determine the effectiveness and implementation potential of TTP counselor or PCP delivered counseling and SDM visit for LCS in real-world clinical settings. The purpose of effectiveness-implementation hybrid design is to blend clinical effectiveness research and implementation science into a single study.29 Implementation outcomes include reach, fidelity, acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness.30

There are three types of effectiveness-implementation trials. Type I focuses primarily on determining whether the intervention is effective and collecting information regarding implementation. Type II focuses both on the effectiveness of the intervention and implementation. Type III focuses primarily on testing the implementation strategy and collecting information regarding the intervention’s effectiveness. A type I hybrid design is appropriate for our study because research personnel will identify potentially eligible patients instead of clinic personnel.

Randomization

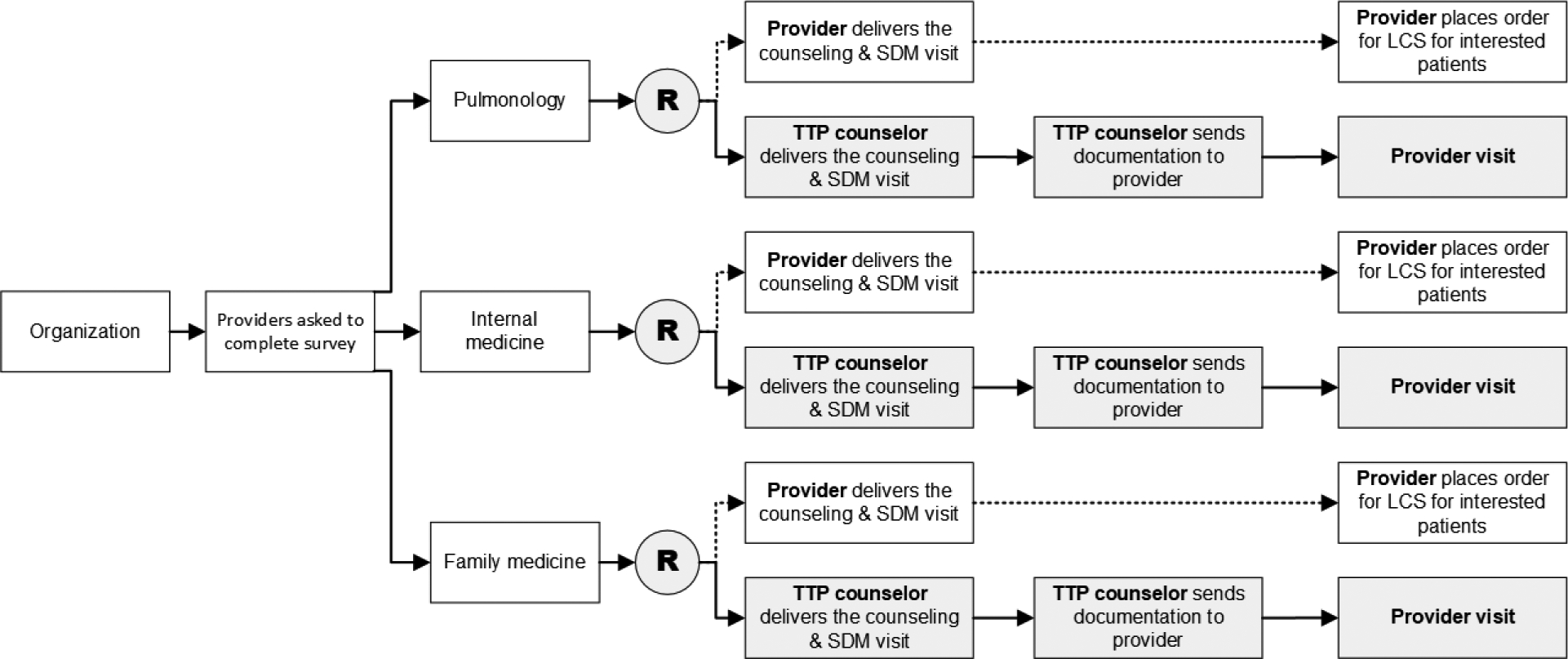

Randomization will be at the level of the provider (Figure 2). We will first stratify providers by organization and specialty, and will randomize them to one of two care delivery strategies in a 1:1 ratio. The two strategies will be usual care (provider delivered smoking cessation and SDM) and centralized care (TTP counselor delivered smoking cessation and SDM). The randomization will be conducted by an analyst not involved in the study intervention nor assessment.

Figure 2. Study Schema.

The figure shows the schema for a single organization, which will be repeated for each additional organization added to the study. The trial will be a cluster randomized trial with the unit of randomization at the provider level. Providers will be stratified by organization and type. All providers, regardless of study arm, will receive the same training on LCS and tobacco cessation counseling. Providers in the usual care arm will deliver the counseling and SDM visit. Providers in the centralized arm will have their visit with the patient and document the counseling and SDM visit delivered by TTP counselors.

The participating health care organizations will contribute up to 40 providers to this study. Each provider will enroll up to 12 patients who currently smoke and meet eligibility criteria for LCS.

Setting

All organizations will be in the southeastern region of the United States and will have large patient populations that will allow us to recruit individuals who are eligible for LCS.

Participants

Provider Participants.

Eligible providers will include family physicians, internal medicine physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs; nurse practitioners and physician assistants), and pulmonary medicine physicians. Providers must have a minimum of a one-half day of outpatient care per week. Providers who are retired or do not have patient care responsibilities will not be eligible.

Provider Recruitment.

We will send an electronic survey with up to three reminders via email. The survey will assess providers’ characteristics (i.e., sex, specialty, year of graduation from residency training, practice location, and amount of time spent in outpatient care per week). Additionally, the survey will include questions about their practice patterns regarding LCS and smoking cessation. We will use the results of the survey to group providers into three specialties: 1) family medicine and family nurse practitioners, 2) general internal medicine and geriatrics, and 3) pulmonary medicine and acute care nurse practitioners in pulmonary medicine.31

Patient Participants.

Eligible patients will be persons who currently smoke (i.e. have smoked in the last month) and meet LCS eligibility criteria from CMS: a) 55–80 years of age, b) 30 pack-year smoking history, c) no history of lung cancer or significant lung disease or other chronic health problems that preclude LCS, and d) asymptomatic for lung cancer.

Individuals previously screened for lung cancer who currently smoke will be eligible for this study because they may benefit substantially from smoking cessation interventions. We will exclude patients with a history of self-reported lung cancer and current use (last seven days) of smoking cessation medications.

Patient Recruitment.

Study coordinators at each study site will review upcoming (within the next four weeks) non-acute care appointments with an enrolled provider. Eligible patients will be called to assess smoking status and pack-year history, and asked about their interest in participating in the study. Central study coordinators will contact interested patients and complete the verbal informed consent and baseline assessments.

Study Arms

Usual Care Arm.

Providers (i.e., physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) in the usual care arm will deliver the counseling and SDM for LCS and place the order for LCS with LDCT. It is possible that providers may elect to use other qualified office staff to deliver the counseling and SDM visit. However, primary providers must be enrolled for their patient to be enrolled.

Providers will have the option to use any decision aid, and we will track their choice. They will also have access to an abbreviated decision aid, which will be developed by the study team. The abbreviated decision aid will be designed to be used during the visit. The decision aid will be a two-page document with one side for the patient and the other for the provider. The patient side will depict five steps to guide the discussion (Table 1). The provider side will provide a summary of the literature supporting LCS with LDCT.

Table 1.

Steps on the Patient Decision Aid

| Step 1: You have a decision to make | States that lung cancer screening is a choice. |

| Step 2: Who should be screened for lung cancer? | Outlines the eligibility criteria for lung cancer screening. |

| Step 3: What to think about when making a decision | States that screening must be done every year. Individuals need to consider their health and willingness to have treatment. Lists the potential benefits and harms associated with lung cancer screening. |

| Step 4: Making a decision | Patients are asked to answer three questions:

|

| Step 5: What is your decision? | Patients are asked to make a decision about screening

|

Counseling and SDM for LCS + Decision Coaching for LCS and Smoking Cessation Counseling.

Patients of providers in the intervention arm will receive SDM for LCS using decision coaching35 and smoking cessation counseling delivered by TTP counselors. The decision coaching intervention will be adapted from a web-based script used in a prior study.35

The TTP counselors will attend an educational session (webinar) about LCS and decision coaching for SDM. We will adapt a training for decision coaching35 to be delivered virtually. In addition to the webinar training, TTP counselors will complete two additional SDM practice sessions with study team members.

Before the telephone visit, the TTP counselor will send the abbreviated decision aid and a link to a video-based decision aid via email. The video-based decision aid will be adapted from a previous study and will follow standards from the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration.36

TTP counselors will use the modified decision coaching intervention for the SDM counseling.35 Decision coaching will include four steps. In the first step, the TTP counselor will clarify that LCS is a choice and assess the patient’s readiness to identify decision-making needs. In the second step, the TTP counselor will assesses the patient’s understanding, provide information about LCS, explore the patient’s values about screening, and further explore decision-making needs (e.g., decision support from others). In the third step, the TTP counselor will administer the Sure of myself, Understand information, Risk-benefit ratio, Encouragement (SURE) scale items to re-evaluate the patient’s readiness to make a decision. The SURE scale is a 4-item patient-reported measure that helps to identify decisional conflict.37 In the last step, the TTP counselor will re-evaluate readiness to make a decision, assess screening preferences and questions about the next steps based on the patient’s preferences.

After the SDM discussion, the TTP counselor will provide guideline-based phone counseling and over-the-counter (OTC) nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) using the nicotine patch (as appropriate). The guideline-based phone counseling will include an initial intake call to develop a quit plan and five, 15 to 20 minute telephone sessions over approximately 5- to 6-weeks with a provision for additional sessions if clinically warranted. Phone sessions will be scheduled in accordance with patient preferences.

The guideline-based phone counseling will include motivational approaches (motivational interviewing) and cognitive behavioral therapy to address barriers to cessation including: stressors associated with medical issues, family, finances; mental health concerns (e.g., depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, alcohol use, etc.) as well as craving, withdrawal, and negative affect.

The counseling protocol will also include a discussion of the risks and benefits of NRT and other pharmacological treatment options, which will prepare patients for an informed discussion with their provider about other pharmacological approaches. The nicotine patch will be provided in 4-week installments for up to 8-weeks of pharmacotherapy, contingent upon patient preference and appropriateness for the patch as well as having at least one contact with the centralized care provider in the preceding interval. The nicotine patch will be shipped directly to the patient. The duration (in minutes) and content areas of counseling calls will be recorded and medication disbursement will be tracked.

Implementation Strategies

The study will use implementation strategies to address known barriers to implementing smoking cessation counseling and SDM for LCS: revising professional roles, identifying and preparing champions, developing education materials, and conducting educational sessions. Table 2 outlines the definition, actor, action, action target, temporality, dose, implementation outcome, and theoretical justification for the selected implementation strategies.

Table 2.

Table of Implementation Strategies

| Implementation Strategy | Revise Professional Roles | Develop & Distribute Education Materials | Conduct Educational Meetings | Identify and Prepare Champions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Tobacco treatment specialists will deliver the SDM for LCS using decision coaching | Slides providing background information on LCS, shared decision making, videos to cover smoking cessation interventions, and decision coaching manual | Didactic sessions on LCS and tobacco cessation | Identify clinicians who are interested in LCS and tobacco cessation |

| Actor | Tobacco treatment specialists | Research team | Research team | Research team |

| Action | Deliver the counseling and SDM for LCS in addition to medical providers | Developed training materials for providers to review smoking cessation interventions, lung cancer screening, and shared decision making | Develop and deliver webinar based training sessions | Identify collaborator in developing the application |

| Action target | Persons who currently smoke and are aged 55 to 80 yearsa | Medical providers; Tobacco treatment specialists | Medical providers and tobacco treatment specialists | Clinician champions |

| Temporality | Before the visit with the medical provider | Before implementation begins | Before implementation begins | Project development stage |

| Dose | Once per patient | Once | Once | Once |

| Implementation Outcome | Reach Fidelity | None | Knowledge Acceptability Feasibility Appropriateness | None |

| Justification | PRISM: Implementation and Sustainability | PRISM: Recipient characteristics | PRISM: Recipient characteristics | PRSIM: Implementation and sustainability |

The age criteria was changed after CMS updated its coverage determination in February 2022.

Revising Professional Roles.

The primary implementation strategy will be adding the delivery of the counseling and SDM for LCS by TTP counselors. By having TTP counselors deliver the counseling and SDM for LCS, we will alleviate the burden on providers by preparing patients to talk with their providers about LCS.

Identifying and Preparing Champions:

We will identify clinical co-investigators who will serve as clinical champions at participating sites.

Developing and Distributing Educational Materials and Conducting Educational Meetings for Providers.

We will distribute slides on LCS, the LuCa National Training Network training for SDM,38 and a 60-minute video or self-paced narrated slide set about tobacco use disorders. The training will include a brief description of the general epidemiology of tobacco use disorders, the biologic basis of nicotine dependence, first line and second line pharmacological treatment options, and screening for treatment and information on treatment pathways. The materials will also present standardized tools to assess suitability for medication (or not) and discussion points to guide the conversation about potential risks, while taking into account patient preference.

Data Collection Procedures

The patient flow is shown in Figure 3. Research study coordinators will contact patients by telephone to complete the informed consent process, assess abstinence, and complete any baseline assessments that were not completed prior to the visit. These contacts will occur within 4-weeks of the patient’s scheduled appointment with the provider. Patients seen by providers in the usual care group will have their scheduled office visit as planned. Patients seen by providers in the centralized care group, an initial call will be scheduled with the TTP counselor. The initial call with the TTP counselor will occur before the scheduled appointment with the provider. Follow-up assessments will occur 1-week after the provider delivered counseling and SDM visit for usual care group and the initial call with the TTP counselor delivered counseling and SDM visit for the centralized care group, and then at 8-weeks, and 12-weeks. We will use an online, HIPAA compliant, institutionally-approved data management system for survey data collection. Patients will receive a secure, unique link to the study survey to complete online. We will call patients who do not complete surveys within five days and will attempt to complete the survey via telephone. If we are unable to reach the patient after three attempts, we will mail the survey to the patient with a self-addressed return envelope. This multipronged assessment approach will maximize follow-up rates in addition to offering compensation for completing assessments.

Figure 3. Patient flow through the trial.

Patients at participating sites will be recruited from participating organizations and then shared with the central site for consent and enrollment. All follow-up assessments will be based upon when the patient receives the counseling and SDM visit whether delivered by the provider in the usual care arm or TTP counselor for providers in the centralized arm. Patients of providers in the centralized arm have their visit after the counseling and SDM visit with the TTP counselor. Note. We followed the 2014 USPSTF32 recommendation when the study was initiated. We changed the eligibility criteria to reflect the March 2021 USPSTF33 recommendations after CMS released its updated criteria in February of 2022.34 Abbreviations: SDM, shared decision making; TTP, tobacco treatment program.

Evaluation of Effectiveness

Table 3 summarizes study outcomes and the corresponding assessment timepoints.

Table 3.

Assessments and Timepoints for Patient-level Data

| Construct | Assessment | Assessment Timepoint | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1 week | 8 weeks | 12 weeks | ||

| Evaluation of Effectiveness | |||||

| Tobacco Dependence | FTND | X | |||

| Demographics, health, & smoking history | Baseline visit questionnaire | X | |||

| Psychological distress | K-6 | X | X | X | |

| Motivation to quit smoking | TSAMS | X | |||

| Nicotine withdrawal | WSWS | X | X | X | X |

| Affect | PANAS | X | X | X | X |

| Smoking risk perception | Risk Perception Questionnaire | X | X | X | X |

| Smoking cessation medication use and compliance | Self-report | X | X | X | |

| Medical record review | Xe | ||||

| Lung cancer screening information | Self-report | X | X | X | |

| Medical record review | Xe | ||||

| Smoking abstinence assessmenta | Timeline Follow Back | X | X | X | X |

| Smoking abstinence assessmentc | Urine cotinine | X | X | X | |

| Knowledge of LCS and benefits of smoking cessationa | LCS-12 | X | X | ||

| Decisional conflict | Decisional Conflict Scale® | X | X | ||

| Evaluation of Implementation | |||||

| Quality of the Shared Decision Making Process | Shared Decision Making Process Survey | X | |||

| 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire | X | ||||

| Reach | Self-reported receipt of SDM and smoking cessation counseling | X | |||

| Medical Record Review | Xe | ||||

| Implementation (Fidelity)d | Fidelity checklist | X | |||

| Acceptability | Ottawa Acceptability Measure | X | |||

| Economic Evaluation | |||||

| Health-related quality of life | EQ-5Db | X | X | X | X |

Primary effectiveness outcomes.

Used for economic analysis for Aim 3.

Only collected for patients who indicate they are abstinent on the timeline follow back.

Patients will be asked questions on the content required by CMS for the smoking cessation counseling and SDM. See provider-level measures for the description of the Implementation (Fidelity) checklist and Aim 2 analysis.

After 12 weeks.

Primary outcomes.

The primary outcomes will be smoking abstinence and knowledge of LCS. Our primary outcome, 7-day point-prevalence abstinence, will be defined as a self-report of no smoking (no combustible product use)39 during the previous seven days and verified with urine cotinine to biochemically verify abstinence.40 To measure smoking abstinence (continuous, prolonged, point prevalence) we will use the timeline follow back.41 Research staff members, not involved in counseling, will verbally guide participants using a calendar to assist recall of special events and other memory cues to report smoking estimates, including other tobacco/e-cigarette products if applicable, for each day since the last assessment. Given previous data42 suggesting a high concordance between self-report and biochemical confirmation, patients who self-report quitting and continued use of NRT or other non-combustible products will be counted as abstinent.

The second primary outcome, LCS knowledge will be assessed with the updated LCS-12.43,44 This is a patient-reported measure that addresses patients’ knowledge of risk factors for lung cancer, eligibility criteria for screening, predictive value of screening, false positives and false negatives, over-diagnosis, mortality reduction, and secondary findings.43,44 We will score the scale as the percent of correct responses.

Secondary outcomes.

We will assess nicotine dependence with the Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence.45,46 This scale assesses various components of smoking behavior such as daily intake, difficulty in refraining from smoking, and time to first cigarette since awake.

We will use the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale to measure distress.47 We will assess motivation to quit smoking with the Texas Smoking Abstinence Motivation Scale.48 The Wisconsin Smoking Withdrawal Scale will be used to assess withdrawal symptoms.49 We will use the subscales to ascertain the effects of quitting on mood and urges to smoke. The Positive and Negative Affect Scale will assess positive and negative affect.50 The Risk Perception Questionnaire will measure smoking risk perception in a LCS environment.51,52 Patients will be asked to estimate personal likelihood of developing a smoking related disease, relative to comparison groups (average person; current or former smoker, etc.) and to indicate their knowledge of and worry about lung cancer.

The Decisional Conflict Scale will measure the degree to which patients feel clear about the options and sure about the choice they make.53 The Shared Decision Making Process Survey will assess the SDM process.54 We will also assess the level of patient involvement with the 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire,55,56 from the perspective of the patient and from the perspective of the provider.

Smoking Cessation Medication Use.

Patients will self-report use of smoking cessation medications. We will conduct a medical record review to abstract information regarding smoking cessation use and compliance, and smoking cessation counseling.

Lung Cancer Screening.

Patients will self-report whether they have received and completed LCS. We will review the medical record to abstract information regarding SDM for LCS, LCS referral, LCS orders, LCS completion, and LCS results including LungRADS.

We will also collect demographic characteristics, health and mental health history, alcohol, and smoking history (e.g., years smoked, previous quit attempts, relapse, current smoking rate, and other nicotine/tobacco use).

Evaluation of implementation

Reach.

To assess reach, we will track the number of patients who received smoking cessation counseling and SDM over the number of patients consented to participate in the study. For all patients, we will verify the receipt of the SDM and smoking cessation counseling through patient report and medical record review.

Implementation (Fidelity).

To assess fidelity, all patients will complete a checklist reporting receipt of the smoking cessation counseling and SDM. We will also assess fidelity of the counseling and SDM visit among providers and TTP counselors using the checklist described above within 1-week for three patients randomly selected for each provider.

Counseling and SDM Visit (Intervention).

To assess acceptability of the intervention from patients’ perspectives, we will use the Ottawa Acceptability Measure adapted for LCS.57

To assess the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility among providers and counselors, we will use the Acceptability of Intervention Measure, Intervention Appropriateness Measure, and Feasibility of Intervention Measure58 at 3-months, 12-months, and 18-months after the study kick-off and training.

Recipient – Organizational Perspective.

We will assess their knowledge of LCS evidence using the updated LCS-12 to identify provider characteristics that may affect implementation.

Implementation and Sustainability Infrastructure.

We will use key informant interviews with providers and field notes from communications to assess the impact on clinical workflow and staff roles, time to implement the SDM visit, staff resources needed, who delivered the counseling and SDM visit and placed the order for LCS, and barriers and facilitators. We will also collect data on when the visit with the provider occurred for the centralized arm, although we do not expect the timing to vary.

Economic evaluation

We will conduct cost-effectiveness and budget impact analyses. For the cost-effectiveness analysis, the primary effectiveness measures will be the number of patients who quit smoking, years of life saved, and quality adjusted life years (QALYs). To calculate QALYs, we will plan to use the EuroQoL 5-level version (EQ-5D-5L) to generate patient utilities for the cost-effectiveness analysis.59,60

Costs associated with implementing smoking cessation plus SDM intervention will include personnel, hardware, and delivering materials to patients. For the usual care group, we will use key informant interviews to estimate the time healthcare providers spent delivering smoking cessation as well as SDM. For the centralized care group, we will collect the qualification of personnel (education level, field of specialization) from human resource record and keep track of time spent in delivering interventions from project logs. For both interventions, any hardware and material costs necessary for implementing the intervention will be tracked through invoices. For participating providers, we will identify the office manager of each provider, discuss resources relevant to the implementation, and engage the officer managers to co-develop strategies to collect information on these resources from their internal accounting systems. All intervention-related costs will be expressed in local market terms for personnel, office space, furnishings, and equipment. Personnel costs will be estimated by multiplying the hourly wage rate of each study personnel by the respective number of hours each spends on delivering the intervention. For patients who received medications to help quit smoking, we will obtain the quantity and type of medications from patients’ medical records. We will then obtain cost per standard unit of dosage for each medication from the average wholesale price reported in the Red Book.61

We will plan to present results of cost-effectiveness analysis as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), by calculating the ratio of additional costs associated with the centralized care approach (compared to usual care) divided by the additional effectiveness (i.e., number of patients who quit smoking, life year gained, or QALY gained) achieved by centralized care. We will plan to conduct a budget impact analysis to inform practices of the financial impact of converting from usual care to centralized care.

Sample size

In this study we will examine the two primary outcomes as individual hypotheses with separate practical clinical implications. For this reason, we will not assume a joint hypothesis (either disjunctive or conjunctive), hence, the significance level of each hypothesis will not be adjusted for multiplicity.62–65 We will expect an abstinence rate of approximately 18% based on data from recent studies in the centralized care arm.66,67 We will expect a lower abstinence rate of approximately 8% in the usual care group.68,69 We will assume unpooled standard errors and an intraclass correlation of 0.01 and will need 210 subjects per study arm to have 80% power. Our sample size calculations will assume 12.5% attrition from the initial sample (N = 480), with the primary outcome modeled in intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses as non-abstinent. We will have sufficient power for this analysis because effect sizes for the lung cancer knowledge outcome will likely be much larger than the abstinence outcome. For evaluating the power of the study we utilized the ClusterPower library in R.

Analysis

The overall purpose of the data analysis will be to estimate the effects between the two strategies on abstinence and smoking behavior, on knowledge of benefits of cancer screening, and on the benefits of cessation in lung cancer risk. Due to the clustered longitudinal design, we will plan to use a three level (i.e., individual, cluster, time point) generalized linear mixed model (GLMM).70 For the implementation outcomes, we will plan to use descriptive analysis, explore variations across providers, and perform thematic analysis on the qualitative interviews to examine practices’ culture. For the economic evaluation, deterministic cost-effectiveness analysis to obtain point estimates of the ICER for short-term and long-term cost-effectiveness will be planned. We will plan to employ non-parametric bootstrapping method to assess statistical uncertainty of the ICER, and will report the 95% confidence interval based on the percentile method.71,72 The budget impact analysis will consider the implementation costs (e.g., personnel time) faced by the clinic.27 Missingness will be treated as Missing-at-Random within maximum likelihood estimation, which produces similar results to multiple imputation approaches, and we will utilize Not-Missing-at-Random approaches (e.g. pattern mixture, selection modeling) if non-ignorable missingness is suspected.73

DISCUSSION

This study will use an effectiveness-implementation type I hybrid design to test the effectiveness of two strategies aimed to increase smoking abstinence rates and the knowledge of LCS, quality of the SDM conversation, factors related to their implementation, and costs of implementation. If successful, this study will provide important new evidence about effective and feasible methods for addressing the leading cause of lung cancer, smoking, and providing patients with an opportunity to make high-quality decisions about whether screening is right for them in real-world clinical settings. The study may lead to improved adherence rates to current guidelines and ultimately decrease the burden of lung cancer.

This study was impacted by the change in eligibility criteria for LCS. Patient recruitment started in March of 2021 and our first patient was enrolled in April of 2021. Although the USPSTF updated its recommendation in March of 2021,33 CMS did not finalize its updated coverage determination for LCS until February 2022. Eligibility criteria for the study were changed after that time to reflect the updated coverage for LCS.34

CMS updated decision for LCS34 has opened the door for innovative care delivery models. The updated decision removed the restriction on who can deliver the counseling and SDM visit, meaning that tobacco treatment specialists (i.e. TTP counselors) could deliver the counseling and SDM visit in appropriate healthcare settings.

This study’s approach to having trained TTP counselors deliver the counseling and SDM visit for LCS will provide a direct test of the updated CMS coverage determination.34 Additionally, it will add to the existing body of work12,14,35 regarding implementation of the counseling and SDM visit for LCS. A centralized approach to the patient counseling and SDM visit requirement represents a potentially feasible and cost-effective alternative to relying on PCPs to be the sole providers to deliver these interventions.

Funding:

The Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RP190210); National Institutes of Health, The National Cancer Institute under award number P30CA016672 using the Shared Decision Making Core and Clinical Protocol and Data Management System.

Competing Interests:

Dr. Cinciripini served on the scientific advisory board of Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, conducted educational talks sponsored by Pfizer on smoking cessation (2006–2008), and has received grant support from Pfizer.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

ClinicalTrials.gov Protocol Registration: NCT04200534

Declaration of interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Availability of data materials

The results of this study will be disseminated via publications in peer reviewed journals and conference presentations. All data will be securely stored as per ethical requirements. Data inquiries can be made to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision Memo for Screening for Lung Cancer with Low Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439N). https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274. Published 2015. Accessed February 5, 2015.

- 2.Ersek JL, Eberth JM, McDonnell KK, et al. Knowledge of, attitudes toward, and use of low-dose computed tomography for lung cancer screening among family physicians. Cancer. 2016;122(15):2324–2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman RM, Sussman AL, Getrich CM, et al. Attitudes and Beliefs of Primary Care Providers in New Mexico About Lung Cancer Screening Using Low-Dose Computed Tomography. Preventing chronic disease. 2015;12:E108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanodra NM, Pope C, Halbert CH, Silvestri GA, Rice LJ, Tanner NT. Primary Care Provider and Patient Perspectives on Lung Cancer Screening. A Qualitative Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(11):1977–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis JA, Petty WJ, Tooze JA, et al. Low-Dose CT Lung Cancer Screening Practices and Attitudes among Primary Care Providers at an Academic Medical Center. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2015;24(4):664–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Triplette M, Kross EK, Mann BA, et al. An Assessment of Primary Care and Pulmonary Provider Perspectives on Lung Cancer Screening. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(1):69–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volk RJ, Foxhall LE. Readiness of primary care clinicians to implement lung cancer screening programs. Preventive medicine reports. 2015;2:717–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeliadt SB, Hoffman RM, Birkby G, et al. Challenges Implementing Lung Cancer Screening in Federally Qualified Health Centers. American journal of preventive medicine. 2018;54(4):568–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodson JD. POINT: Should Only Primary Care Physicians Provide Shared Decision-making Services to Discuss the Risks/Benefits of a Low-Dose Chest CT Scan for Lung Cancer Screening? Yes. Chest 2017;151(6):1213–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powell CA. COUNTERPOINT: Should Only Primary Care Physicians Provide Shared Decision-making Services to Discuss the Risks/Benefits of a Low-Dose Chest CT Scan for Lung Cancer Screening? No. Chest. 2017;151(6):1215–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodson JD. Rebuttal From Dr Goodson. Chest. 2017;151(6):1217–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanner NT, Banas E, Yeager D, Dai L, Hughes Halbert C, Silvestri GA. In-person and Telephonic Shared Decision-making Visits for People Considering Lung Cancer Screening: An Assessment of Decision Quality. Chest. 2019;155(1):236–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter-Harris L, Gould MK. Multilevel Barriers to the Successful Implementation of Lung Cancer Screening: Why Does It Have to Be So Hard? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(8):1261–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alishahi Tabriz A, Neslund-Dudas C, Turner K, Rivera MP, Reuland DS, Elston Lafata J. How Health-Care Organizations Implement Shared Decision-making When It Is Required for Reimbursement: The Case of Lung Cancer Screening. Chest. 2021;159(1):413–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith HB, Ward R, Frazier C, Angotti J, Tanner NT. Guideline-Recommended Lung Cancer Screening Adherence Is Superior With a Centralized Approach. Chest. 2022;161(3):818–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazzone PJ, Silvestri GA, Souter LH, et al. Screening for Lung Cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2021;160(5):e427–e494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiCarlo M, Myers P, Daskalakis C, et al. Outreach to primary care patients in lung cancer screening: A randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2022;159:107069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park ER, Gareen IF, Japuntich S, et al. Primary care provider-delivered smoking cessation interventions and smoking cessation among participants in the National Lung Screening Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1509–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update, Clinical Practice Guideline. Published 2008. Updated 04.03.2015. Accessed.

- 20.Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Group C. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2012;345:e5661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hales S, Lesher-Trevino A, Ford N, Maher D, Ramsay A, Tran N. Reporting guidelines for implementation and operational research. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(1):58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mauskopf JA, Sullivan SD, Annemans L, et al. Principles of good practice for budget impact analysis: report of the ISPOR Task Force on good research practices--budget impact analysis. Value Health. 2007;10(5):336–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramsey S, Willke R, Briggs A, et al. Good research practices for cost-effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials: the ISPOR RCT-CEA Task Force report. Value Health. 2005;8(5):521–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramsey SD, Willke RJ, Glick H, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials II-An ISPOR Good Research Practices Task Force report. Value Health. 2015;18(2):161–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan SD, Mauskopf JA, Augustovski F, et al. Budget impact analysis-principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 Budget Impact Analysis Good Practice II Task Force. Value Health. 2014;17(1):5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(4):228–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez-Olivo MA, Minnix JA, Fox JG, et al. Smoking cessation and shared decision-making practices about lung cancer screening among primary care providers. Cancer Med. 2021;10(4):1357–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moyer VA, U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of internal medicine. 2014;160(5):330–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Krist AH, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for Lung Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2021;325(10):962–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Screening for Lung Cancer with Low Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT). In:2022.

- 35.Lowenstein LM, Godoy MCB, Erasmus JJ, et al. Implementing Decision Coaching for Lung Cancer Screening in the Low-Dose Computed Tomography Setting. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(8):e703–e725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volk RJ, Lowenstein LM, Leal VB, et al. Effect of a Patient Decision Aid on Lung Cancer Screening Decision-Making by Persons Who Smoke: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(1):e1920362–e1920362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Legare F, Kearing S, Clay K, et al. Are you SURE?: Assessing patient decisional conflict with a 4-item screening test. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2010;56(8):e308–314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LuCa National Training Network. Lung Cancer Screening and Shared Decision Making for Primary Care Providers. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/luca-training-network-cme/interactive/18674317?resultClick=1&bypassSolrId=M_18674317. Published 2021. Accessed March 28, 2022.

- 39.Piper ME, Bullen C, Krishnan-Sarin S, et al. Defining and Measuring Abstinence in Clinical Trials of Smoking Cessation Interventions: An Updated Review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2019;22(7):1098–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benowitz NL, Ahijevych K, Hall S, et al. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002;4:149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12(2):101–112. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Studts JL, Ghate SR, Gill JL, et al. Validity of Self-reported Smoking Status among Participants in a Lung Cancer Screening Trial. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2006;15(10):1825–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lowenstein LM, Richards VF, Leal VB, et al. A brief measure of Smokers’ knowledge of lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography. Preventive medicine reports. 2016;4:351–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Housten AJ, Lowenstein LM, Leal VB, Volk RJ. Responsiveness of a Brief Measure of Lung Cancer Screening Knowledge. Journal of cancer education : the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fagerström KO. A comparison of psychological and pharmacological treatment in smoking cessation. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1982;5(3):343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heppner WL, Ji L, Reitzel LR, et al. The role of prepartum motivation in the maintenance of postpartum smoking abstinence. Health Psychology. 2011;30(6):736–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welsch SK, Smith SS, Wetter DW, Jorenby DE, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Development and validation of the Wisconsin Smoking Withdrawal Scale. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;7(4):354–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park ER, Gareen IF, Jain A, et al. Examining whether lung screening changes risk perceptions: National Lung Screening Trial participants at 1-year follow-up. Cancer. 2013;119(7):1306–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park ER, Ostroff JS, Rakowski W, et al. Risk perceptions among participants undergoing lung cancer screening: Baseline results from the national lung screening trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;37(3):268–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Medical decision making : an international journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making. 1995;15(1):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sepucha KR, Stacey D, Clay CF, et al. Decision quality instrument for treatment of hip and knee osteoarthritis: a psychometric evaluation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scholl I, Kriston L, Dirmaier J, Buchholz A, Härter M. Development and psychometric properties of the Shared Decision Making Questionnaire – physician version (SDM-Q-Doc). Patient Education and Counseling. 2012;88(2):284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kriston L, Scholl I, Hölzel L, Simon D, Loh A, Härter M. The 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9). Development and psychometric properties in a primary care sample. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;80(1):94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O’Connor A, Cranney A. User Manual - Acceptability. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Acceptability.pdf. Published 1996. Updated 2002. Accessed October 10, 2012.

- 58.Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2011;20(10):1727–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care. 2005;43(3):203–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.RED BOOK. https://www.ibm.com/products/micromedex-red-book. Accessed December 28, 2022.

- 62.Rubin M. When to adjust alpha during multiple testing: a consideration of disjunction, conjunction, and individual testing. Synthese. 2021;199(3):10969–11000. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Armstrong RA. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2014;34(5):502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sinclair J, Taylor P, Hobbs S. Alpha level adjustments for multiple dependent variable analyses and their applicability – A review. International Journal of Sport Science and Engineering. 2013;7. [Google Scholar]

- 65.O’Keefe DJ. Colloquy: Should Familywise Alpha Be Adjusted? Human Communication Research. 2003;29(3):431–447. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith SS, McCarthy DE, Japuntich SJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of 5 smoking cessation pharmacotherapies in primary care clinics. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169(22):2148–2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ferketich AK, Otterson GA, King M, Hall N, Browning KK, Wewers ME. A pilot test of a combined tobacco dependence treatment and lung cancer screening program. Lung Cancer. 2012;76(2):211–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, Sanchez G, Hartmann-Boyce J, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;5:CD000165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Meyer C, Ulbricht S, Gross B, et al. Adoption, reach and effectiveness of computer-based, practitioner delivered and combined smoking interventions in general medical practices: A three-arm cluster randomized trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;121(1–2):124–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Application and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barber JA, Thompson SG. Analysis of cost data in randomized trials: an applicantion of the non-parametric bootstrap. Stat Med. 2000;19(23):3219–3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Glick H. Economic evaluation in clinical trials. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schafer JL, Olsen MK. Multiple Imputation for Multivariate Missing-Data Problems: A Data Analyst’s Perspective. Multivariate Behav Res. 1998;33(4):545–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The results of this study will be disseminated via publications in peer reviewed journals and conference presentations. All data will be securely stored as per ethical requirements. Data inquiries can be made to the corresponding author.