Abstract

Background:

Drug use is prevalent among people who attend electronic dance music (EDM) parties at nightclubs or festivals. This population can serve as a sentinel population to monitor trends in use of party drugs and new psychoactive substances (NPS) that may diffuse through larger segments of the population.

Methods:

We surveyed adults entering randomly selected EDM parties at nightclubs and dance festivals in New York City about their drug use in 2017 (n=954), 2018 (n=1,029), 2019 (n=606), 2021 (n=229), and 2022 (n=419). We estimated trends in past-year and past-month use of 22 drugs or drug classes based on self-report from 2017–2022 and examined whether there were shifts pre- vs. post-COVID (2017–2019 vs. 2021–2022).

Results:

Between 2017 and 2022, there were increases in past-year and past-month use of shrooms (psilocybin), ketamine, poppers (amyl/butyl nitrites), synthetic cathinones (“bath salts”), and novel psychedelics (lysergamides and DOx series), increases in past-year cannabis use, and increases in past-month use of 2C series drugs. Between 2017 and 2022, there were decreases in past-year heroin use and decreases in past-month cocaine use, novel stimulant use, and nonmedical benzodiazepine use. The odds of use of shrooms, poppers, and 2C series drugs significantly increased after COVID, and the odds of use of cocaine, ecstasy, heroin, methamphetamine, novel stimulants, and prescription opioids (nonmedical use) decreased post-COVID.

Conclusions:

We estimate shifts in prevalence of various drugs among this sentinel population, which can inform ongoing surveillance efforts and public health response in this and the general populations.

Keywords: new psychoactive substances, club drugs, epidemiology, methamphetamine, ketamine

Introduction

It is important to monitor trends in drug use because timely identification of shifting patterns can facilitate appropriate decision-making processes that underpin public health responses, interventions, policies, and prevention and harm reduction education. The most accurate trend data are based on self-reported drug use, and common sources include national surveys.

Despite the usefulness of national surveys, they are still bound by several limitations. Most national surveys, for example, rely on people who are noninstitutionalized or live in households, which can lead to underestimates of use—especially of more stigmatized drugs, such as heroin and methamphetamine (Reuter, Caulkins, & Midgette, 2021). National surveys are also limited insofar as the release of results typically lag by at least one year. Furthermore, some national studies do not survey the population every year, and less common drugs, such as new psychoactive substances (NPS), are inadequately queried. Indeed, the three major national drug surveys in the United States (US) are subject to most of these limitations (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality [CBHSQ], 2021; Jones, et al., 2020; Miech et al., 2023), as are major surveys in Europe (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction [EMCDDA], 2022; Home Office, 2021) and Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2020). Further still, some national surveys ask about NPS use as a general category (AIHW, 2020; Home Office, 2021), while others only ask about one or two specific NPS categories, such as synthetic cannabinoids (Miech et al., 2023). Others do not ask about common or particularly problematic NPS or other novel drugs until many years after their emergence (CBHSQ, 2021). Additionally, national surveys in the US do not query fentanyl or synthetic opioid use, despite these compounds being associated with tens of thousands of deaths per year (Hedegaard, Miniño, Spencer, & Warner, 2021). Surveillance data focusing on drug seizures, wastewater, and on poisonings and deaths related to use, are informative for drug availability, consumption, and adverse drug-related outcomes, respectively, but additional sources focusing on self-report are needed to address the knowledge gaps left across available surveillance sources.

There exists an important gap in drug use epidemiology as it relates to monitoring trends in use of party drugs and less common drugs such as NPS. Smaller ongoing or repeated cross-sectional studies can aid in detecting possible trends in drug use among both at-risk populations and the general population. People who attend nightclubs and dance festivals—particularly those featuring electronic dance music (EDM)—typically report high levels of drug use, especially common “party drugs” such as ecstasy/MDMA, cocaine, and ketamine, as well as NPS (Hughes, Moxham-Hall, Ritter, Weatherburn, & MacCoun, 2017; Kelly, Parsons, & Wells, 2006; Mohr, Fogarty, Krotulski, & Logan, 2020; Palamar & Keyes, 2020; Ramo, Grov, Delucchi, Kelly, & Parsons, 2011). Moreover, certain drugs originally popular among nightclub-attending populations have been theorized to subsequently diffuse throughout the general population (Hamid, 1992; Palamar JJ, 2020), hence focusing on use within this population can potentially inform potential downstream trends among the general population as well. In fact, recent evidence suggests this party-going population may be able to serve as a bellwether for trends in drug-related outcomes in the general population (Palamar, Le, Rutherfold, & Keyes, 2022). As such, we believe EDM party attendees may be regarded as a sentinel population for certain drug trends among the general population at wide.

Indeed, multiple studies have examined or estimated trends in use of various psychostimulants and other drugs among people in this or similar populations (Palamar & Keyes, 2020; Price et al., 2022, 2023), but we believe it is useful to focus on a wider array of psychoactive substances. Further, given that prevalence of use often shifts over time, it is important to continue to estimate trends that include recent data (e.g., collected in 2022). As such, more recent trend data can help inform prevention and harm reduction efforts both in the sentinel population in which the data were collected and in the general population, while updated trend estimates can also inform surveillance in other countries. In this study, we estimate trends in use of 22 drugs and drug classes among EDM party attendees in New York City (NYC) between 2017 and 2022, as such trends can inform public health efforts with a particular focus on prevention and harm reduction.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

This repeated cross-sectional study used time-space sampling (MacKellar et al., 2007) to survey adults about to enter EDM parties at nightclubs or dance festivals about their drug use during summer months (typically June through September) of 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, and 2022. Each week, events were randomly selected using R 3.1 software (R Core Team) based on an ongoing list of parties listed on a popular EDM party ticket website and based on recommendations of key informants. Recruitment typically occurred on 1–2 nights per week on Thursday through Sunday. While most participants were surveyed entering nightclubs, participants were also surveyed outside of 1–2 daytime EDM dance festivals each year. Individuals were eligible if they were age ≥18 and were about to enter the selected venue. Surveys were taken on tablets after informed consent was provided, and survey completers were compensated $10 USD. The survey took an average of ten minutes to complete. Participants were surveyed entering 188 events—39 in 2017, 24 in 2018, 80 in 2019, 23 in 2021, and 22 in 2022, and survey response rates were 74%, 73%, 65%, 63%, and 82%, respectively. The total sample size was 3,237, with 954 surveyed in 2017, 1,029 in 2018, 606 in 2019, 229 in 2021, and 419 in 2022. We were unable to survey participants in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All methods were approved by the New York University Langone Medical Center institutional review board.

Measures

Participants were asked about demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, sexual orientation) and about their frequency of past-year EDM party attendance. They were then asked about their lifetime, past-year, and past-month use of various drugs. Classes of NPS and other ‘novel’ drugs were grouped together and queried on the same page (see Supplemental Figure 1 for sample survey page). Each year, we asked about use of 12 common drugs and nonmedical use of 8 prescription opioids and 10 benzodiazepines. Nonmedical use was defined as use without a prescription or use in a manner in which the drug was not prescribed, such as to get high (Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration, 2015). Regarding NPS and more novel drugs, we queried 13–24 synthetic cathinones (“bath salts”), 8–25 tryptamines, 5–18 2C series drugs, 1–6 NBOMe series drugs, 5–8 novel dissociatives (arylcyclohexylamines), 9–11 other novel psychedelics (lysergamides and DOx series), synthetic cannabinoids (via a single item), 4–7 novel opioids, and 9–14 novel stimulants. A list of specific drugs queried each year is presented in Supplemental Table 1. The full drug list was presented over 12–13 survey pages. Lists of specific NPS were shortened in later years due to low (or no) reported use and to ensure that lists of compounds were not too long for participants. Importantly, compounds removed from lists in later years were instead listed below “other” compounds in that class not listed. For example, 3-FMC was removed from the synthetic cathinone checklist in 2018, but this compound was then listed below “other” drugs in this class as an example. An affirmative response to any drug in a class was coded as an affirmative response to use of that class. Test-retest reliability of drug questions in this study has been shown to be high (κ=0.88–1.00) (Palamar, Le, Acosta, & Cleland, 2019).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were weighted to account for the complex survey design. Specifically, we calculated and applied sample weights based on response rates and on self-reported frequency of party attendance because more frequent attendees have a higher likelihood of being sampled across venues. For attendance, weights were inversely proportional to frequency of attendance (e.g., the weight for attending only once per year attendees was 52 times larger than the weight for those who attended weekly). For the response rate component, weights were inversely proportional to the night-level response rate. The two weight components were then combined via multiplication and normalized (i.e., the sum of weights was equal to the total sample size). As such, estimates for frequent attendees were down-weighted and estimates for infrequent attendees were up-weighted. Weights thus make results more generalizable to all party attendees rather than frequent attendees.

We first calculated descriptive statistics to estimate the weighted prevalence of self-reported use of each drug or drug class (past-year and past-month use) within each year. We used three methods to examine trends—all using multivariable logistic regression controlling for participant age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, sexual orientation, and recruitment venue type (nightclub vs. festival). First, we fit an indicator for each year (with 2017 as the comparison) and used the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for 2022 to determine whether there was a significant difference in prevalence between the first and last year. Next, we estimated whether there was a linear association between use of each drug and time (year). Specifically, we determined whether there was a linear trend by estimating log-odds of use as a linear function of time as a continuous predictor. Year was coded as 0, 1, 2, 4, and 5 for 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, and 2022, respectively. Finally, we determined whether there was a significant change in prevalence after COVID (2021–2022) compared to pre-COVID years (2017–2019) by including this as a binary indicator variable in each model. Statistical significance for all tests was determined at the two-sided α<0.05 level. Missingness of demographic characteristics was 0.0% and missingness of drug use responses (due to respondents not completing the full survey) ranged from 0.0% to 2.4% (average missingness: 0.9%). Cases missing data for use of a specific drug were excluded in analyses focusing on use of that drug. Data were analyzed using Stata 17 SE (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and survey commands were used to generate estimates (Heeringa, West, & Berglund, 2010) with randomly selected party specified as the primary sampling unit.

Results

Overall, the majority of participants were age ≥26 (53.8%), male (55.8%), heterosexual (79.1%), and had a college degree or higher (60.6%), with the plurality identifying as white (46.5%). The majority (66.2%) were surveyed entering nightclubs as opposed to festivals. Sample characteristics by year are presented in Supplemental Table 2. Of note, between 2017 and 2022, there were increases in the proportion of participants identifying as female, gay/lesbian, or bisexual, and those having attended any graduate school; concomitantly, the proportion of participants identifying as black, as having attended some college, and those recruited at festivals, decreased.

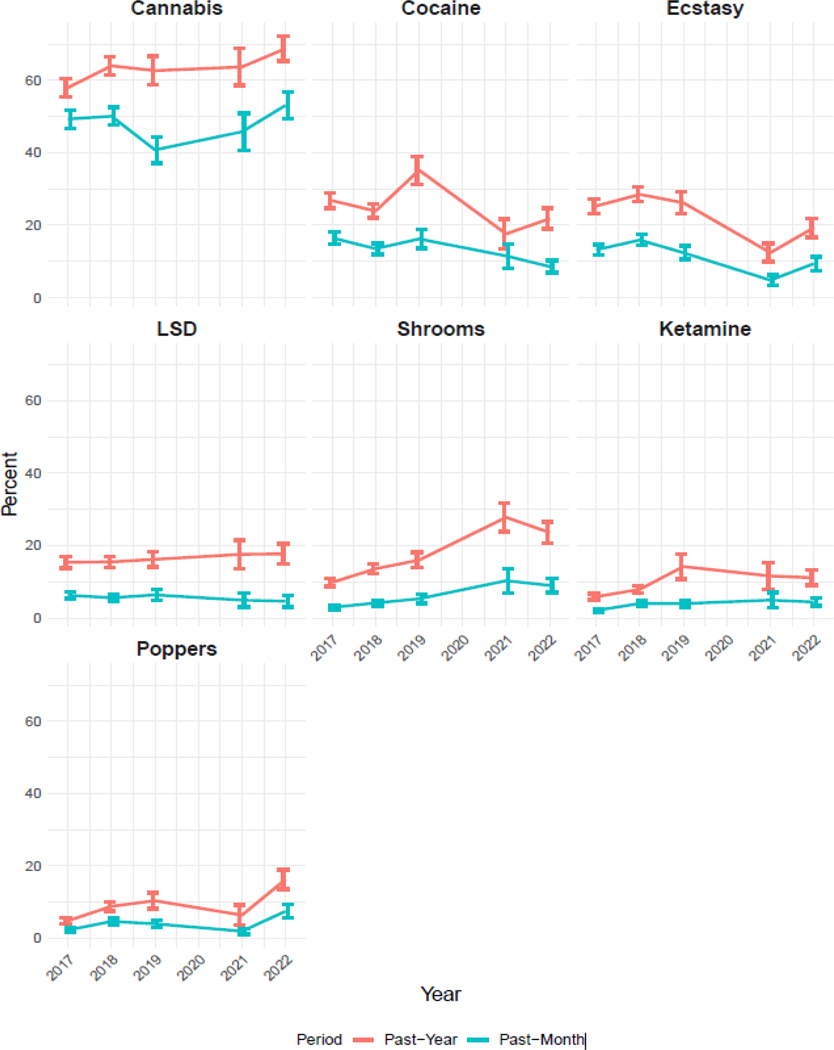

Table 1 presents prevalence estimates in 2017 and 2022 and associated trend statistics for all drugs and Supplemental Table 3 presents prevalence estimates for all years. Estimates of the seven most prevalent common drugs are plotted in Figure 1. Both the contrast between 2017 with 2022 (aOR=1.54, 95% CI: 1.05–2.25) and the linear trend (aOR=1.07, 95% CI: 1.00–1.15) indicate an increase in past-year cannabis use. Significant shifts were not detected for past-month use or for use in relation to COVID. With respect to cocaine use, there was a decrease in past-month use as indicated by a decrease in prevalence between 2017 and 2022 (aOR=0.41, 95% CI: 0.25–0.67), a decreasing linear trend (aOR=0.87, 95% CI: 0.79–0.95), and reduced odds of use after COVID (aOR=0.59, 95% CI: 0.38–0.91). We did not detect a significant change in past-year use in 2022 compared to 2017, although results did suggest a downward linear trend (aOR=0.92, 95% CI: 0.86–0.99) and decreased odds of use after COVID (aOR=0.61, 95% CI: 0.44–0.86). With respect to ecstasy use, the contrast between 2017 and 2022 was not significant, although we did detect a significant downward linear trend in past-year (aOR=0.89, 95% CI: 0.83–0.95) and past-month use (aOR=0.88, 95% CI: 0.81–0.96), and both odds for past-year (0.52, 95% CI: 0.39–0.70) and past-month use (aOR=0.49, 95% CI: 0.33–0.72) decreased after COVID. No significant trends were detected for LSD use, but past-year use of shrooms (psilocybin) increased from 9.8% to 23.6% (a 140.1% increase; aOR=2.76, 95% CI: 1.78–4.27), and past-month use increased from 2.9% to 9.0% (a 207.2% increase; aOR=3.17, 95% CI: 1.70–5.91). Increasing linear trends were found for past-year (aOR=1.25, 95% CI: 1.16–1.35) and past-month use (aOR=1.28, 95% CI: 1.14–1.44), and odds for both past-year (aOR=2.29, 95% CI: 1.69–3.11) and past-month use (aOR=2.56, 95% CI: 1.55–4.24) increased after COVID.

Table 1.

Estimated shifts in past-year and past-month use of each drug or drug class.

| 2017 Weighted % (95% CI) | 2022 Weighted % (95% CI) | Relative Change (2022 vs. 2017) % | 2022 vs. 2017 aOR (95% CI) | Linear Trend aOR (95% CI) | Post- vs. Pre-COVID aOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis | ||||||

| Past-Year | 58.0 (53.0, 62.8) | 68.8 (61.6, 75.2) | 18.3 | 1.54 (1.05–2.25) | 1.07 (1.00–1.15) | 1.21 (0.90–1.65) |

| Past-Month | 49.3 (44.3, 54.3) | 53.1 (45.8, 60.4) | 7.7 | 1.21 (0.85–1.74) | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) | 1.11 (0.84–1.48) |

| Cocaine | ||||||

| Past-Year | 26.8 (22.9,31.0) | 21.8 (16.8, 27.9) | −18.7 | 0.68 (0.46–1.01) | 0.92 (0.86–0.99) | 0.61 (0.44–0.86) |

| Past-Month | 16.5 (13.4, 20.0) | 8.6 (5.9, 12.5) | −48.1 | 0.41 (0.25–0.67) | 0.87 (0.79–0.95) | 0.59 (0.38–0.91) |

| Ecstasy | ||||||

| Past-Year | 25.3 (21.6, 29.5) | 19.3 (14.7, 25.0) | −23.7 | 0.70 (0.47–1.04) | 0.89 (0.83–0.95) | 0.52 (0.39–0.70) |

| Past-Month | 13.2 (10.6, 16.4) | 9.4 (6.21,13.9) | −29.0 | 0.72 (0.43–1.21) | 0.88 (0.81–0.96) | 0.49 (0.33–0.72) |

| LSD | ||||||

| Past-Year | 15.4 (12.6, 18.7) | 17.7 (12.8, 23.9) | 14.9 | 1.31 (0.83–2.09) | 1.07 (0.98–1.16) | 1.24 (0.88–1.77) |

| Past-Month | 6.3 (4.6, 8.5) | 4.6 (2.4,8.9) | −26.2 | 0.81 (0.37–1.77) | 0.97 (0.85–1.10) | 0.81 (0.46–1.45) |

| Shrooms | ||||||

| Past-Year | 9.8 (7.8, 12.4) | 23.6 (18.3, 30.0) | 140.1 | 2.76 (1.78–4.27) | 1.25 (1.16–1.35) | 2.29 (1.69–3.11) |

| Past-Month | 2.9 (2.0, 4.3) | 9.0 (5.9, 13.6) | 207.2 | 3.17 (1.70–5.91) | 1.28 (1.14–1.44) | 2.56 (1.55–4.24) |

| Ketamine | ||||||

| Past-Year | 5.9 (4.5, 7.6) | 11.1 (7.6, 15.9) | 88.8 | 1.90 (1.12–3.24) | 1.14 (1.04–1.25) | 1.38 (0.87–2.19) |

| Past-Month | 2.1 (1.5, 2.9) | 4.4 (2.7, 7.1) | 111.5 | 1.99 (1.05–3.76) | 1.12 (1.00–1.26) | 1.47 (0.83–2.59) |

| Poppers | ||||||

| Past-Year | 4.9 (3.4, 6.9) | 16.3 (11.7, 22.3) | 235.4 | 3.49 (1.97–6.19) | 1.18 (1.07–1.32) | 1.64 (1.05–2.53) |

| Past-Month | 2.3 (1.5, 3.6) | 7.5 (4.6, 12.0) | 224.2 | 3.35 (1.66–6.77) | 1.14 (1.00–1.31) | 1.45 (0.87–2.45) |

| Methamphetamine | ||||||

| Past-Year | 2.0 (1.0, 3.9) | 4.8 (2.2, 10.3) | 147.7 | 2.04 (0.69–6.09) | 1.15 (0.96–1.38) | 1.48 (0.68–3.19) |

| Past-Month | 0.6 (0.3, 1.2) | 0.3 (0.1, 1.3) | −44.2 | 0.53 (0.11–2.50) | 0.89 (0.77–1.04) | 0.19 (0.05–0.68) |

| GHB | ||||||

| Past-Year | 1.5 (0.8, 2.8) | 1.3 (0.3, 5.9) | −12.0 | 0.86 (0.17–4.43) | 0.91 (0.74–1.13) | 0.33 (0.07–1.49) |

| Heroin | ||||||

| Past-Year | 1.3 (0.6, 2.8) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.3) | −96.8 | 0.02 (0.00–0.20) | 0.58 (0.36–0.96) | 0.15 (0.03–0.80) |

| Amphetamine | ||||||

| Past-Year | 13.4 (10.8, 16.6) | 12.2 (8.1, 18.2) | −9.0 | 0.81 (0.47–1.37) | 0.97 (0.89–1.07) | 0.85 (0.56–1.30) |

| Past-Month | 8.8 (6.7, 11.5) | 6.6 (3.6, 11.8) | −25.4 | 0.66 (0.33–1.34) | 0.90 (0.79–1.02) | 0.65 (0.38–1.12) |

| Benzodiazepines | ||||||

| Past-Year | 12.4 (9.6, 15.9) | 7.2 (4.1, 12.4) | −41.9 | 0.52 (0.26–1.04) | 0.90 (0.78–1.03) | 0.72 (0.40–1.29) |

| Past-Month | 6.0 (4.2, 8.6) | 1.8 (0.6, 4.8) | −70.8 | 0.24 (0.08–0.74) | 0.76 (0.59–0.98) | 0.56 (0.23–1.38) |

| Prescription Opioids | ||||||

| Past-Year | 8.9 (6.4, 12.2) | 3.5 (1.3, 8.8) | −60.7 | 0.40 (0.14–1.14) | 0.76 (0.64–0.91) | 0.26 (0.11–0.58) |

| Past-Month | 4.2 (2.4, 7.1) | 1.2 (0.2, 5.6) | −71.9 | 0.27 (0.04–1.63) | 0.72 (0.52–0.98) | 0.22 (0.05–0.94) |

| Synthetic Cannabinoids | ||||||

| Past-Year | 2.4 (1.3, 4.4) | 3.6 (1.9, 6.8) | 48.8 | 1.78 (0.75–4.24) | 1.05 (0.88–1.25) | 1.16 (0.58–2.31) |

| Past-Month | 1.0 (0.4, 2.3) | 3.1 (1.5, 6.4) | 223.3 | 4.57 (1.61–12.94) | 1.25 (0.99–1.57) | 2.24 (0.97–5.16) |

| Novel Stimulants | ||||||

| Past-Year | 2.1 (1.3, 3.2) | 1.0 (0.5, 2.0) | −51.6 | 0.56 (0.23–1.37) | 0.93 (0.78–1.11) | 0.63 (0.27–1.48) |

| Past-Month | 1.0 (0.6, 1.8) | 0.2 (0.04, 0.8) | −84.0 | 0.15 (0.03–0.79) | 0.65 (0.49–0.88) | 0.15 (0.04–0.56) |

| Tryptamines | ||||||

| Past-Year | 1.7 (1.0, 2.9) | 2.0 (0.5, 7.2) | 17.4 | 1.60 (0.42–6.04) | 1.15 (0.91–1.44) | 1.82 (0.69–4.82) |

| Past-Month | 0.5 (0.2, 1.4) | 1.5 (0.3, 8.0) | 221.8 | 3.45 (0.74–16.06) | 1.26 (0.93–1.70) | 1.90 (0.47–7.68) |

| 2C Series | ||||||

| Past-Year | 1.1 (0.5, 2.5) | 2.4 (0.8, 7.3) | 113.2 | 2.07 (0.54–8.02) | 1.20 (0.97–1.48) | 1.93 (0.89–4.17) |

| Past-Month | 0.2 (0.1, 0.4) | 2.1 (0.6, 7.4) | 895.3 | 11.04 (2.80–43.56) | 1.58 (1.26–1.97) | 4.50 (1.89–10.76) |

| Synthetic Cathinones | ||||||

| Past-Year | 1.1 (0.5, 2.27) | 3.5 (1.2, 9.7) | 229.9 | 4.79 (1.34–17.09) | 1.14 (0.97–1.35) | 1.14 (0.49–2.64) |

| Past-Month | 0.1 (0.05, 0.25) | 2.5 (0.7, 8.7) | 2224.1 | 34.38 (7.62–155.20) | 1.14 (0.94–1.38) | 0.94 (0.33–2.68) |

| Novel Psychedelics | ||||||

| Past-Year | 0.7 (0.3, 1.6) | 3.0 (1.3, 6.7) | 344.8 | 5.95 (1.74–20.35) | 1.16 (0.98–1.38) | 1.10 (0.43–2.86) |

| Past-Month | 0.1 (0.02, 0.4) | 2.8 (1.1, 6.6) | 2547.6 | 45.01 (7.63–265.49) | 1.26 (1.05–1.53) | 1.41 (0.49–4.03) |

| NBOMe | ||||||

| Past-Year | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) | 1.4 (0.2, 8.3) | 235.0 | 3.49 (0.55–22.22) | 0.94 (0.71–1.24) | 0.55 (0.12–2.43) |

| Novel Dissociatives | ||||||

| Past-Year | 0.4 (0.1, 1.7) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.1) | −37.5 | 1.19 (0.26–5.46) | 0.90 (0.72–1.11) | 0.48 (0.17–1.39) |

| Novel Opioids | ||||||

| Past-Year | 0.9 (0.3, 2.3) | 0.1 (0.02, 0.9) | −86.3 | 0.09 (0.01–0.85) | 1.01 (0.76–1.35) | 1.68 (0.44–6.20) |

Note. Pre-COVID is defined as 2017–2019 and post-COVID is defined as 2021–2022. aOR = adjusted odds ratio, controlling for participant age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, sexual orientation, and recruitment venue type (nightclub vs. festival); CI = confidence interval. Bold estimates indicate statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Trends in past-year and past-month use of cannabis, cocaine, ecstasy, LSD, shrooms (psilocybin), ketamine, and poppers.

Between 2017 and 2022, past-year ketamine use increased from 5.9% to 11.1% (an 88.8% increase; aOR=1.90, 95% CI: 1.12–3.24) and past-month use increased from 2.1% to 4.4% (a 111.5% increase; aOR=1.99, 95% CI: 1.05–3.76). Results suggest increasing linear trends for both past-year (aOR=aOR=1.14, 95% CI: 1.04–1.25) and past-month use (aOR=1.12, 95% CI: 1.00–1.26), although neither significantly shifted after COVID. Past-year poppers (amyl/butyl nitrite) use increased from 9.8% to 24.5% (a 234.5% increase; aOR=3.49, 95% CI: 1.97–6.19) as did past-month use (from 2.3% to 7.5%, a 224.2% increase; aOR=3.35, 95% CI: 1.66–6.77) with significant linear increases in both past-year (aOR=1.18, 95% CI: 1.07–1.32) and past-month use (aOR=1.14, 95% CI: 1.00–1.31), and a significant increase in past-year use after COVID (aOR=1.64, 95% CI: 1.05–2.53). Estimates of the three less prevalent common drugs are presented in Figure 2. Past-year heroin use decreased by 96.8% (aOR=0.02, 95% CI: 0.00–0.20). This was a linear decrease (aOR=0.58, 95% CI: 0.36–0.96), and odds for use decreased after COVID (aOR=0.15, 95% CI: 0.03–0.80). Between 2017 and 2022, although there was a decrease in odds of past-month methamphetamine use after COVID (aOR=0.15, 0.03–0.80). Prevalence of GHB use did not significantly increase or decrease.

Figure 2.

Trends in past-year and past-month use of methamphetamine, and trends in past-year use of GHB and heroin.

Figure 3 presents estimates of nonmedical use of three commonly prescribed classes of drugs. Between 2017 and 2022, there was a decrease in nonmedical benzodiazepine use from 6.0% to 1.8% (a 70.8% decrease; aOR=0.24; 95% CI: 0.08–0.74) and a decreasing linear trend (aOR=0.76, 95% CI: 0.59–0.98). No differences were detected for past-year misuse, however. We did not detect significant changes in prevalence of nonmedical prescription opioid use between 2017 and 2022 via contrast of 2017 with 2022, although we did detect significant downward linear trends in past-year (aOR=0.76, 95% CI: 0.64–0.91) and past-month nonmedical use (aOR=0.72, 95% CI: 0.52–0.98), and odds of past-year (aOR=.026, 95% CI: 0.11–9.58) and past-month use (aOR=0.22, 95% CI: 0.05–0.94) decreased after COVID. No significant shifts were detected with respect to nonmedical amphetamine use.

Figure 3.

Trends in past-year and past-month nonmedical use of amphetamine, benzodiazepines, and prescription opioids. Nonmedical use was defined as use without a prescription or use in a manner in which the drug was not prescribed such as to get high.

Figure 4 presents estimates from the nine NPS and novel drugs. Between 2017 and 2022, past-month synthetic cannabinoid use increased from 1.0% to 3.1% (a 223.3% increase). Although this was a significant increase (aOR=4.57, 95% CI: 1.61–12.94), the linear increase only approached significance (aOR=1.25, 95% CI: 0.99–1.57). There was a significant decrease in past-month use of novel stimulants with use decreasing from 1.0% to 0.2% (an 84.0% decrease; aOR=0.15, 95% CI: 0.03–0.79), a decreasing linear trend (aOR=0.65, 95% CI: 0.49–0.88), and the odds for use decreased after COVID (aOR=0.15, 95% CI: 0.04–0.56). Past-month use of 2C series drugs significantly increased from 0.2% to 2.1% (an 895.3% increase; aOR=11.04; 95% CI: 2.80–43.56), an increasing linear trend (aOR=1.58, 95% CI: 1.26–1.97), and the odds for use increased after COVID (aOR=4.50, 95% CI: 1.89–10.76). Past-year synthetic cathinone use increased from % to 3.5% (aOR=4.79, 95% CI: 1.23–17.09) and past-month use increased from 1.1% to 3.5% (aOR=34.38, 95% CI: 7.62–155.20) and linear trends were not significant, nor were the contrasts of COVID periods. Past-year use of novel psychedelics significantly increased from 0.7% to 3.0% (a 344.8% increase; aOR=5.95, 95% CI: 1.74–20.35) and past-month use significantly increased from 0.1 % to 2.8% (aOR=45.01, 95% CI: 7.63–265.49). While a linear increase was detected for past-month use (aOR=1.26, 95% CI: 1.05–1.53), no significant shifts occurred after COVID. Past-year use of novel opioids significantly decreased by 86.3% between 2017 and 2022 (aOR=0.09, 95% CI: 0.01–0.85), but the linear trend was not significant, nor was the contrast of COVID periods. We did not detect changes in prevalence regarding use of tryptamines, NBOMe, or novel dissociatives.

Figure 4.

Trends in past-year and past-month use of synthetic cannabinoids, novel stimulants, tryptamines, 2C series drugs, synthetic cathinones, and novel psychedelics, and past-year use of NBOMe, novel dissociatives, and novel opioids.

Discussion

We estimated trends in use of various drugs and drug classes in this repeated cross-sectional study of a sentinel population known for high prevalence of drug use. We detected various upward and downward trends in use, which can guide public health efforts including education (particularly for new initiates), general prevention, and harm reduction efforts, such as drug checking and overdose response.

We detected increases in use of nine drugs or drug classes. Shrooms (psilocybin) use demonstrated the most consistent upward trend with increases in past-year and past-month use between 2017 and 2022. These findings align with results other national studies in the US (Walsh, Livne, Shmulewitz, Stohl, & Hasin, 2022), including results from a recent national panel study of young adults that showed use of common psychedelics, including shrooms, reaching an all-time high in 2021 since the survey began in 1988 (Patrick et al., 2022). Moreover, it is worth noting that there has been a recent uptick in research focusing on the medical benefits of psilocybin in treating psychiatric disorders (Castro Santos & Gama Marques, 2021), with many studies having received extensive media attention. It is unknown to what extent positive media attention has influenced increases in recreational use, but self-medication is a common reason for use (Matzopoulos, Morlock, Morlock, Lerer, & Lerer, 2021), and microdosing has recently gained popularity for reasons such as performance enhancement (Hutten, Mason, Dolder, & Kuypers, 2019).

Prevalence of past-year ketamine use also increased, which may likewise be related to increased media attention about medical benefits associated with use. The US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) approved a nasal spray containing esketamine (an enantiomer of ketamine) to treat depression in 2019 (US FDA, 2019), and such media coverage appears to be related to a greater number of people wanting to use or initiate the drug (Palamar & Le, 2022). Although rare compared to many other drugs, past-year use, seizures, and poisonings related to ketamine use have been increasing in the US (Palamar, Fitzgerald, et al., 2022; Palamar, Rutherford, & Keyes, 2021; Walsh, et al., 2022), which appear to corroborate our findings. Use also appears to be increasing in Australia (AIHW, 2020).

Past-year poppers use greatly increased in this population. Poppers have been prevalent in the US nightclub scene since the 1970s (Lowry, 1982), particularly among gay and bisexual men (Schuler & Ramchand, 2023) as this drug is often used to facilitate anal sex (Giorgetti et al., 2017). Little is known about trends in use, in part, because inhalants are typically queried as a general category, but in 2021, the US FDA published a press release to alert the public to an increase in hospitalizations and deaths related to use (US FDA, 2021), which may indicate increased prevalence in use. Therefore, our findings may warrant more nuanced surveillance of poppers use.

We also detected increases in past-year and past-month use of novel psychedelics and past-month use of 2C series drugs, which corroborates increases in overall use of psychedelics in the US (Livne, Shmulewitz, Walsh, & Hasin, 2022). 2C series use remains rare, though other data have suggested prevalence of lifetime use increasing in the US between 2005 and 2017 (Palamar & Le, 2019). Furthermore, there were increases in detection of 2C series drugs among forensic samples, consumer samples, and poison center exposures in the Netherlands between 2013 and 2017 (Hondebrink, Nugteren-van Lonkhuyzen, Van Der Gouwe, & Brunt, 2015). Self-reported synthetic cannabinoid use also increased in this population. It is unknown if this increase is due to overreporting as cannabis vape products, which recently increased in popularity (Miech et al., 2023). In any case, we estimate that prevalence is currently very low. Prevalence of use was highest in the US a decade ago, and use and related poisonings have dropped substantially since (American Association of Poison Control Centers, 2022; Miech et al., 2023). Given the changing landscape of cannabis availability in the US, we recommend that researchers clearly differentiate synthetic cannabinoids from other novel products that contain actual cannabis or THC.

Past-year cannabis use increased in this population, which was not unexpected given the recent legalization of recreational use in New York and general increases in use nationally (Patrick et al., 2022). Of note, however, were the increases in use of synthetic cathinones, commonly referred to as “bath salts” in the US. A hair testing study of EDM party attendees in NYC detected a decrease in unknown and suspected exposure to these compounds between 2016 and 2019 (Palamar & Salomone, 2021), while a study testing saliva of festival attendees in Miami, Florida also detected decreases between 2014 and 2017 (Mohr et al., 2020). Fewer synthetic cathinones have been discovered in recent years compared to 2014/15, but the number of seizures and amount seized has actually recently increased in Europe (EMCDDA, 2022). Self-reported use of synthetic stimulants, such as “bath salts”, on national surveys in the US also remains rare. For example, only 0.2% of adults ages 18–25 in the US were estimated as having engaged in lifetime use in 2021 (CBHSQ, 2022). Further, reported use among 12th graders in the US declined from 1.3% in 2012 to 0.6% in 2018, and questions about use were then removed from this survey, likely due to low prevalence (Miech et al., 2023). Indeed, detection of specific compounds, such as eutylone, have increased in the US in recent years based on forensic investigations into drug-related poisonings and deaths (Gladden, Chavez-Gray, O’Donnell, & Goldberger, 2022; NPS Discovery, 2023). We believe most of such use is via unknown exposure through adulterated drugs. More attention should be diverted towards possible increases in synthetic cathinone use among this population.

We detected decreases in prevalence of use of seven drugs or drug classes in this population—with particularly notable dips among two of the most common party drugs—ecstasy and cocaine. Both also demonstrated a marked dip after the onset of COVID-19. While use in general has decreased over the past two decades in the US (Miech et al., 2023), studies focusing on high school students and nightclub attendees in the US, studies focusing on wastewater and drug-checking services in Europe, and studies of frequent psychostimulant users in Australia, have likewise noted particular decreases in ecstasy use since the COVID-19 pandemic (EMCDDA, 2022; Miech et al., 2023; Price et al., 2022).

Similarly, we found that past-year and past-month cocaine use decreased in this population, which—at least immediate post-pandemic—may have also been attributable to a decrease in nightlife attendance due pandemic-related closures (Bendau, et al., 2022; EMCDDA, 2020; EMCDDA & Europol, 2020). However, deaths related to cocaine use have increased dramatically in recent years—both in the US and in the UK, often due to co-use with opioids (Hedegaard et al., 2021; Mattson et al., 2021; Palamar, Le et al., 2022). Although opioid use is not as prevalent as party drug use among EDM venue attendees, we recommend continued monitoring of cocaine use among this population as well as the general population as cocaine use is still commonly associated with adverse effects particularly related to polydrug use (Gummin, et al., 2022).

While our findings did not suggest significant increases or decreases in methamphetamine use between 2017 and 2022 specifically, we did detect a decrease in use post-COVID. However, nationally, there have been upward trends in use, greater risk patterns have increased, as has the prevalence of methamphetamine use disorder (Han, Compton, Jones, Einstein, & Volkow, 2021). Moreover, psychostimulant-related deaths—primarily driven by methamphetamine use—have increased greatly in the US, especially among people who use opioids (Hedegaard et al., 2021; Mattson et al., 2021). More severe methamphetamine use and related harms have also been increasing in Australia (Man et al., 2022). Prevalence is much higher in this population than in the general population, so we believe prevention and harm reduction efforts need to continue.

Availability and pricing of cocaine and ecstasy post-COVID in particular could have played a role in lowering prevalence, and most research suggesting higher-than-normal prices and lower availability and drug quality was the case soon after the onset of COVID (Bendau et al., 2022; EMCDDA & Europol, 2020; Farhoudian et al., 2021; Price O et al., 2022, 2023). More information is needed regarding more current availability and prices, but seizure data in the US suggest that cocaine has remained available post-COVID despite some price fluctuations (US Drug Enforcement Administration, 2021). Use of these drugs warrant continued surveillance, and more research is needed to determine whether decreased availability of these common party drugs influence people to use different, more available drugs (Zaami, Marinelli, & Varì, 2020). Regardless of whether prevalence of use remains lower or rebounds, harm reduction is still needed to diminish risk of effects such as overheating and dehydration while using.

Not only were there decreases in use of the common psychostimulants—ecstasy, cocaine, and methamphetamine—but we detected decreases in past-month use of novel stimulants between 2017 and 2022. A hair testing study of NYC nightclub and festival attendees also found that unknown exposure to stimulants such as 4-FA and 5/6-APB diminished between 2016 and 2019 (Palamar & Salomone, 2021). Results of psychostimulants, taken together, suggest overall decreases in psychostimulant use in this population.

Nonmedical use of prescription opioids and benzodiazepines also dropped in this population, which largely reflects decreased prevalence of use in the US population (Miech et al., 2023; Schepis, McCabe, & Ford, 2022). Indeed, deaths related to commonly prescribed opioids have also leveled in recent years, but recent large increases in deaths related to use of synthetic opioids, such as fentanyls, have increased (Hedegaard et al., 2021). Deaths related to benzodiazepine use have also been increasing, though most involve co-use of opioids (Liu, O’Donnell, Gladden, McGlone, & Chowdhury, 2021). Moreover, it should be noted that detection of novel benzodiazepines in forensic samples in the US greatly increased from 2018 through 2021 (Krotulski, Papsun, Walton, Fogarty, & Logan, 2021). As such, it is possible that such compounds were adulterants leading to unknown exposures. Past-year heroin use also decreased among the EDM attendees, which also reflects national estimates of use (Miech et al., 2023). Deaths related to heroin use increased from 2005 through 2016 but have since decreased (Hedegaard et al., 2021). Finally, the prevalence of use of novel opioids decreased among EDM venue attendees despite deaths related to use greatly increasing in the US in recent years (Hedegaard, et al., 2021). However, concern remains regarding use of novel opioids as these compounds may be included as adulterants or contaminants in other drugs and thus can lead to unintentional exposure. Given that this is becoming a more widespread issue, people who use drugs in powder form in the US in particular need to be cognizant about the possibility of accidental fentanyl exposure and drug checking can be a first-line defense (along with continued education).

Prevalence of use of six drugs or drug classes in this study did not significantly increase or decrease. LSD use did not significantly increase or decrease in this population despite the fact that LSD use increased in the US between 2002 and 2019 (Livne, et al., 2022), with an increase in reported exposures to Poison Control (Ng, Banerji, Graham, Leonard, & Wang, 2019). However, an Australian study of frequent psychostimulant users also found that LSD was among the most consistently used drugs during the pandemic (Price et al., 2022). Similarly, we did not detect changes in prevalence of use in tryptamines or NBOMe. While tryptamine use increased in the US between 2007 and 2014, overall prevalence of use remains rare (Palamar & Le, 2018; Walsh et al., 2022). Despite increases in GHB-related emergencies through 2019 in countries like Australia (Arunogiri et al., 2020), use appears to have remained stable in the US (Palamar, 2022), even despite an international online survey suggesting increases during COVID-19 (Bendau et al., 2022). We did not detect a shift in nonmedical amphetamine use despite use of amphetamines decreasing among adolescents in the US (Miech et al., 2023) and despite a current shortage in Adderall (US FDA, 2022), the main amphetamine drug nonmedically used in the US. Finally, we did not detect shifts in use of novel dissociatives among attendees. Many novel dissociatives have emerged in the past decade (Morris & Wallach, 2014), with methoxetamine in particular receiving a lot of attention as a ketamine replacement (Winstock, Lawn, Deluca, & Borschmann, 2016). However, despite a small uptick in discoveries of new dissociatives in 2020, discovery of new compounds since 2013 has been rare (EMCDDA, 2022). Use was also rare among EDM party attendees.

Limitations

Estimates were based on self-report, which is susceptible to respondents underreporting use either intentionally (e.g., due to stigma) or unintentionally (e.g., due to unknown exposure via adulterants or contaminants). We have found that this population has underreported use of some common drugs, particularly cocaine and ketamine (Palamar & Salomone, 2021). We cannot accurately deduce the proportions of intentional versus unintentional underreporting (or underreporting due to some participants answering the survey in a hurry), but we do believe that previously detected high levels of underreported use of methamphetamine and synthetic cathinones is due to unknown exposure to these compounds through ecstasy or other drugs (Palamar & Salomone, 2021). There is evidence that some ketamine and cocaine products now also contain fentanyl or novel opioids (Fresno County Sheriff’s Office, 2017; NSW Health, 2022; Park et al., 2021; Zibbell, Aldridge, Cauchon, DeFiore-Hyrmer, & Conway, 2019), which can lead to underreporting of novel opioid use and increase risk for poisoning or overdose. As such, it is important to keep in mind that there may be substantial underreporting of use or exposure—not just in this study, but in many studies. As such, future studies can benefit from comparing self-report and results from biological testing, and studies using a combination of methods to query use can be valuable (Betzler et al., 2019). With respect to trends, is it further unknown whether underreporting shifted across time.

Various participant characteristics shifted across time, but it is unknown to what extent this reflects the populations attending such events, who was present during recruitment times, or who ultimately consented to participation. In addition, fewer people were surveyed at festivals (vs. nightclubs) over time and this can also suggest somewhat differing populations. In light of such shifts, we controlled for these variables in our models to reduce the influence of such shifts. It is also possible that some participants were confused regarding drug names, which can lead to over- or underreporting. For example, some may think LSZ is the same drug as LSD and therefore overreport use of novel psychedelics. Finally, we only estimated prevalence of use, not frequency or “severity” of use. Therefore, it is unknown to what extent increases or decreases in use should alert public health practitioners to alter prevention or harm reduction methods.

Conclusions

We estimated shifts in prevalence of various drugs among this sentinel population. We believe these estimates are important as these may help inform monitoring of drug use and related outcomes both in this population and in the general population—both in the US and internationally. Results can also inform policy, such as laws allowing better or more legal access to drug checking and drug education without people who administer or use such tests being subject to arrest. Not only does monitoring of prevalence of use need to continue, but monitoring of frequency and “severity” of use, unknown exposure to adulterants or contaminants through use, and drug-related adverse effects (e.g., poisonings, hospitalizations) could better inform public health response. Even drugs that are rarely used in this population need to be monitored, first, because use can shift; and second, because some rarer drugs (e.g., NBOMe, fentanyls) actually tend to have higher risk for adverse effects than common party drugs. While increases in prevalence do not necessarily indicate increases in harm, we believe that drugs that are increasing in prevalence in particular require additional monitoring and additional targeted prevention and harm reduction efforts.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

We estimated trends in drug use among nightclub/festival attendees from 2017 to 2022

There were increases in past-year use of poppers, ketamine, and shrooms

There were increases in past-month use of 2C series drugs and novel psychedelics

There were decreases in use of ecstasy, cocaine, and prescription opioids after COVID

Results can inform ongoing surveillance efforts and public health response

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01DA044207, K01DA038800, and P30DA01104. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Palamar has consulted for Alkermes. The authors have no other potential conflicts to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Association of Poison Control Centers. (2022). Synthetic Cannabinoids Data. Retrieved from https://aapcc.org/track/synthetic-cannabinoids

- Arunogiri S, Moayeri F, Crossin R, Killian JJ, Smith K, Scott D, & Lubman DI (2020). Trends in gamma-hydroxybutyrate-related harms based on ambulance attendances from 2012 to 2018 in Victoria, Australia. Addiction, 115(3), 473–479. 10.1111/add.14848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020). National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019. In Drug Statistics series no. 32. PHE 270: Canberra: AIHW. Retieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/national-drug-strategy-household-survey-2019/contents/summary [Google Scholar]

- Bendau A., Viohl L., Petzold MB., Helbig J., Reiche S., Marek R., … Betzler F. (2022). No party, no drugs? Use of stimulants, dissociative drugs, and GHB/GBL during the early COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Drug Policy, 102, 103582. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betzler F, Ernst F, Helbig J, Viohl L, Roediger L, Meister S, … Köhler S (2019). Substance use and prevention programs in Berlin’s party scene: Results of the SuPrA-Study. European Addiction Reseach, 25(6), 283–292. 10.1159/000501310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro Santos H, & Gama Marques J (2021). What is the clinical evidence on psilocybin for the treatment of psychiatric disorders? A systematic review. Porto Biomed Journal, 6(1), e128. 10.1097/j.pbj.0000000000000128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2021). Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. In. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2020-nsduh-detailed-tables [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2022). Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. In. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-nsduh-detailed-tables [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2020). EMCDDA Trendspotter briefing: Impact of COVID-19 on patterns of drug use and drug-related harms in Europe. Lisbon. Retrieved from https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/ad-hoc-publication/impact-covid-19-patterns-drug-use-and-harms_en [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2022). European Drug Report 2022: Trends and Developments. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. Retrieved from https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/edr/trends-developments/2022_en [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, & Europol. (2020). EU Drug Markets — Impact of COVID-19. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Retrived from https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/joint-publications/eu-drug-markets-impact-of-covid-19_en [Google Scholar]

- Farhoudian A, Radfar SR, Mohaddes Ardabili H, Rafei P, Ebrahimi M, Khojasteh Zonoozi A, … Ekhtiari H (2021). A global survey on changes in the supply, price, and use of illicit drugs and alcohol, and related complications during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 646206. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.646206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresno County Sheriff’s Office. HIDTA drug task force seizes $6.8 million in fentanyl and ketamine. Retrived from https://www.fresnosheriff.org/media-relations/hidta-drug-task-force-seizes-6-8-million-in-fentanyl-and-ketamine.html

- Giorgetti R, Tagliabracci A, Schifano F, Zaami S, Marinelli E, & Busardò FP (2017). When “chems” meet sex: A rising phenomenon called “chemsex”. Current Neuropharmacology, 15(5), 762–770. 10.2174/1570159X15666161117151148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladden RM, Chavez-Gray V, O’Donnell J, & Goldberger BA (2022). Notes from the field: Overdose deaths involving eutylone (psychoactive bath salts) – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 71(32), 1032–1034. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7132a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MC, Spyker DA, Rivers LJ, Feldman R, … Weber JA. (2022). 2021 Annual report of the National Poison Data System(©) (NPDS) from America’s Poison Centers: 39th annual report. Clinincal Toxicology, 60(12), 1381–1643. 10.1080/15563650.2022.2132768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid AJ (1992). The developmental cycle of a drug epidemic: The cocaine smoking epidemic of 1981–1991. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 24(4), 337–348. 10.1080/02791072.1992.10471658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Compton WM, Jones CM, Einstein EB, & Volkow ND (2021). Methamphetamine use, methamphetamine use disorder, and associated overdose deaths among US adults. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(12):1329–1342. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Spencer MR, & Warner M (2021). Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2020. NCHS Data Brief, 426, 1–8. 10.15620/cdc:112081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, West BT, & Berglund PA (2010). Applied survey data analysis. London: Chapman and Hall: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Home Office. (2021). Crime in England and Wales: Year ending December 2020. Office of National Statistics. Retrived from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/crimeinenglandandwales/yearendingdecember2020 [Google Scholar]

- Hondebrink L, Nugteren-van Lonkhuyzen JJ, Van Der Gouwe D, & Brunt TM (2015). Monitoring new psychoactive substances (NPS) in The Netherlands: Data from the drug market and the Poisons Information Centre. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 147, 109–115. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.11.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CE, Moxham-Hall V, Ritter A, Weatherburn D, & MacCoun R (2017). The deterrent effects of Australian street-level drug law enforcement on illicit drug offending at outdoor music festivals. International Journal of Drug Policy, 41, 91–100. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutten N, Mason NL, Dolder PC, & Kuypers KPC (2019). Motives and side-effects of microdosing with psychedelics among users. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacol, 22(7), 426–434. 10.1093/ijnp/pyz029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Clayton HB, Deputy NP, Roehler DR, Ko JY, Esser MB, … Hertz MF (2020). Prescription opioid misuse and use of alcohol and other substances among high school students – Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Suppl, 69(1), 38–46. 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, Parsons JT, & Wells BE (2006). Prevalence and predictors of club drug use among club-going young adults in New York City. Journal of Urban Health, 83(5), 884–895. 10.1007/s11524-006-9057-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krotulski AJ, Papsun DM, Walton SE, Fogarty MF, & Logan BK (2021). NPS Discovery: Year in review 2021. United States: Center for Forensic Science Research and Education. Retrived from https://www.cfsre.org/nps-discovery/trend-reports

- Liu S, O’Donnell J, Gladden RM, McGlone L, & Chowdhury F (2021). Trends in nonfatal and fatal overdoses involving benzodiazepines - 38 States and the District of Columbia, 2019–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 70(34), 1136–1141. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7034a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livne O, Shmulewitz D, Walsh C, & Hasin DS (2022). Adolescent and adult time trends in US hallucinogen use, 2002–19: any use, and use of ecstasy, LSD and PCP. Addiction, 117(12):3099–3109. 10.1111/add.15987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry TP. (1982). Psychosexual aspects of the volatile nitrites. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 14(1-2), 77–79. 10.1080/02791072.1982.10471914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKellar DA, Gallagher KM, Finlayson T, Sanchez T, Lansky A, & Sullivan PS (2007). Surveillance of HIV Risk and Prevention Behaviors of Men who Have Sex with Men—A National Application of Venue-Based, Time-Space Sampling. Public Health Reports, 122 Suppl 1, 39–47. 10.1177/00333549071220S107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man N, Sisson SA, McKetin R, Chrzanowska A, Bruno R, Dietze PM, … Peacock A (2022). Trends in methamphetamine use, markets and harms in Australia, 2003–2019. Drug and Alcohol Review, 41(5), 1041–1052. 10.1111/dar.13468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, Kariisa M, Patel P, & Davis NL (2021). Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths – United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 70(6), 202–207. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzopoulos R, Morlock R, Morlock A, Lerer B, & Lerer L (2021). Psychedelic mushrooms in the USA: Knowledge, patterns of use, and association with health outcomes. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 780696. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.780696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, Patrick ME, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2023). Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2022: Secondary School Students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. Retrived from https://monitoringthefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/mtf2022.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mohr ALA, Fogarty MF, Krotulski AJ, & Logan BK (2020). Evaluating trends in novel psychoactive substances using a sentinel population of electronic dance music festival attendees. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 45(5):490–497. 10.1093/jat/bkaa104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris H, & Wallach J (2014). From PCP to MXE: A comprehensive review of the non-medical use of dissociative drugs. Drug Testing and Anal, 6(6–7), 614–632. 10.1002/dta.1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng PC, Banerji S, Graham J, Leonard J, & Wang GS (2019). Adolescent exposures to traditional and novel psychoactive drugs, reported to National Poison Data System (NPDS), 2007–2017. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 202, 1–5. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NPS Discovery. NPS stimulants and hallucinogens in the United States. Retrieved from https://www.cfsre.org/nps-discovery/trend-reports/nps-stimulants-and-hallucinogens/report/49?trend_type_id=3

- NSW Health. Cocaine and ketamine may contain the dangerous opioids fentanyl and acetylfentanyl. Retrieved from https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/aod/public-drug-alerts/Pages/cocaine-or-ketamine-contains-fentanyl.aspx

- Palamar JJ (2022). Prevalence and Correlates of GHB Use among Adults in the United States. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 1–6. 10.1080/02791072.2022.2081948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Palamar JJ (2020). Diffusion of ecstasy in the electronic dance music scene. Substance Use & Misuse, 55(13), 2243–2250. 10.1080/10826084.2020.1799231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Fitzgerald ND, Grundy DJ, Black JC, Jewell JS, & Cottler LB. (2022). Characteristics of poisonings involving ketamine in the United States, 2019–2021. Journal of Psychopharmacology, in press. 10.1177/02698811221140006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Palamar, & Keyes KM. (2020). Trends in drug use among electronic dance music party attendees in New York City, 2016–2019. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 209, 107889. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, & Le A (2022). Media coverage about medical benefits of MDMA and ketamine affects perceived likelihood of engaging in recreational use. Addiction Research & Theory, 30(2), 96–103. 10.1080/16066359.2021.1940972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Le A, Acosta P, & Cleland CM (2019). Consistency of self-reported drug use among electronic dance music party attendees. Drug and Alcohol Review, 38(7), 798–806. 10.1111/dar.12982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Le A, Rutherfold C, & Keyes KM (2022). Exploring potential bellwethers for drug-related mortality in the general population: A case for sentinel surveillance of trends in drug use among nightclub/festival attendees. Substance Use & Misuse, 58(2):188–197. 10.1080/10826084.2022.2151315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, & Le A (2018). Trends in DMT and other tryptamine use among young adults in the United States. American Journal on Addictions, 27(7), 578–585. 10.1111/ajad.12803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, & Le A (2019). Use of new and uncommon synthetic psychoactive drugs among a nationally representative sample in the United States, 2005–2017. Human Psychopharmacology, 34(2), e2690. 10.1002/hup.2690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Rutherford C, & Keyes KM (2021). Trends in ketamine use, exposures, and seizures in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 111(11), 2046–2049. 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, & Salomone A (2021). Shifts in unintentional exposure to drugs among people who use ecstasy in the electronic dance music scene, 2016–2019. American Journal on Addictions, 30(1), 49–54. 10.1111/ajad.13086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JN, Rashidi E, Foti K, Zoorob M, Sherman S, & Alexander GC (2021). Fentanyl and fentanyl analogs in the illicit stimulant supply: Results from U.S. drug seizure data, 2011–2016. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 218, 108416. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price O, Man N, Sutherland R, Bruno R, Dietze P, Salom C, … Peacock A (2023). Disruption to Australian heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine and ecstasy markets with the COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions. International Journal of Drug Policy, in press. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.103976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Price O, Man N, Bruno R, Dietze P, Salom C, Lenton S… Peacock A (2022). Changes in illicit drug use and markets with the COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions: Findings from the Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System, 2016–20. Addiction, 117(1), 182–194. 10.1111/add.15620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Grov C, Delucchi KL, Kelly BC, & Parsons JT (2011). Cocaine use trajectories of club drug-using young adults recruited using time-space sampling. Addictive Behaviors, 36(12), 1292–1300. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter P, Caulkins JP, & Midgette G (2021). Heroin use cannot be measured adequately with a general population survey. Addiction, 116(10):2600–2609. 10.1111/add.15458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis TS, McCabe SE, & Ford JA (2022). Recent trends in prescription drug misuse in the United States by age, race/ethnicity, and sex. American Journal on Addictions, 31(5), 396–402. 10.1111/ajad.13289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, & Bachman JG. (2022). Monitoring the Future Panel Study annual report: National data on substance use among adults ages 19 to 60, 1976–2021. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. Retrieved from https://monitoringthefuture.org/results/publications/monographs/panel-study-annual-report-adults-1976-2021/ [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MS, & Ramchand R (2023). Examining inhalant use among sexual minority adults in a national sample: Drug-specific risks or generalized risk? LGBT Health, 10(1), 80–85. 10.1089/lgbt.2022.0042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration. (2015). CBHSQ Methodology Report: National Survey on Drug Use and Health: 2014 and 2015 Redesign Changes. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/national-survey-drug-use-and-health-2014-and-2015-redesign-changes [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Federal Drug Administration. (2019). FDA approves new nasal spray medication for treatment-resistant depression; available only at a certified doctor’s office or clinic. FDA Press Release. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-nasal-spray-medication-treatment-resistant-depression-available-only-certified [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration. (2021). FDA advises consumers not to purchase or use nitrite “poppers”. Retrived from https://www.fda.gov/food/alerts-advisories-safety-information/fda-advises-consumers-not-purchase-or-use-nitrite-poppers#:~:text=Purpose,death%2C%20when%20ingested%20or%20inhaled

- US Food and Drug Administration. (2022). FDA Announces Shortage of Adderall. Retrived from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-announces-shortage-adderall

- US Drug Enforcement Administration. (2021). 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment. DEA-DCT-DIR-008–21. Retrieved from https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2021-02/DIR-008-21%202020%20National%20Drug%20Threat%20Assessment_WEB.pdf

- Walsh CA, Livne O, Shmulewitz D, Stohl M, & Hasin DS (2022). Use of plant-based hallucinogens and dissociative agents: U.S. Time Trends, 2002–2019. Addictive Behavior Reports, 16, 100454. 10.1016/j.abrep.2022.100454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstock AR, Lawn W, Deluca P, & Borschmann R (2016). Methoxetamine: An early report on the motivations for use, effect profile and prevalence of use in a UK clubbing sample. Drug and Alcohol Review, 35(2), 212–217. 10.1111/dar.12259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaami S, Marinelli E, & Varì MR (2020). New trends of substance abuse during COVID-19 pandemic: An international perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 700. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zibbell JE, Aldridge AP, Cauchon D, DeFiore-Hyrmer J, & Conway KP (2019). Association of law enforcement seizures of heroin, fentanyl, and carfentanil with opioid overdose deaths in Ohio, 2014–2017. JAMA Network Open, 2(11), e1914666. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.