Abstract

All aerobic organisms have mechanisms that protect against oxidative compounds. Catalase, peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione, and thioredoxin are widely distributed in many taxa and constitute elements of a nearly ubiquitous antioxidant metabolic strategy. Interestingly, the regulatory mechanisms that control these elements are rather different depending on the nature of the oxidative stress and the organism. Catalase is well documented to play an important role in protecting cells from oxidative stress. In particular, pathogenic bacteria seem to use this enzyme as a defensive tool against attack by the host. To investigate the significance of catalase in hostile environments, we made catalase deletion mutations in two different B. abortus strains and used two-dimensional gel analysis, survival tests, and adaptation experiments to explore the behavior and role of catalase under several oxidative stress conditions. These studies show that B. abortus strains that do not express catalase activity exhibit increased sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide. We also demonstrate that catalase expression is regulated in this species, and that preexposure to a sublethal concentration of hydrogen peroxide allows B. abortus to adapt so as to survive subsequent exposure to higher concentrations of hydrogen peroxide.

Catalase activity is widely regarded as essential or nearly essential for aerobic life because oxidative metabolism produces superoxide and hydrogen peroxide as inevitable by-products (15). Pathogens face the additional challenge of oxidative intermediates produced by neutrophils and macrophages. Upon infection, these phagocytes suddenly increase oxygen consumption and produce oxygen intermediates, such as H2O2, superoxide, HOCl, hydroxyl radical, and singlet oxygen (2–4, 33).

Brucella abortus is an intracellular parasite that causes bovine brucellosis, a disease characterized by fever and reproductive failure due to abortion, epididymitis, and male sterility (18, 48, 52). Within hours after exposure of a host animal to B. abortus by ingestion or via the conjunctiva, most bacteria are found in phagocytic cells. In chronic disease, the bacteria persist and multiply inside phagocytic cells (9, 21, 41, 47, 49, 75).

The genus Brucella consists of a very closely related group of pathogens classified into six species (48). These species have a very similar genetic makeup but exhibit different host species virulence. They are estimated to differ from one another by only a few percent in nucleotide sequence (73). Two strains of B. abortus were used in this study. Strain 2308 is fully virulent in cattle, while strain 19 was used for many years as a live cattle vaccine. It is thought to have become attenuated through prolonged passage in the laboratory. Both strains cause persistent infections in many animals including humans. The only known genetic differences between strain 19 and more virulent strains are subtle alterations in outer membrane characteristics and the inactivation of the erythritol catabolic pathway in strain 19 (58). In other respects, strain 19 represents a convenient model for the entire Brucella genus.

Generally, pathogenic bacteria possess adaptive and defensive mechanisms that allow survival in the hostile phagocyte environment (6, 13, 24, 38, 41). Those that survive inside the phagosome are thought to change their physiology by altering their protein expression patterns in response to the new environment. The physiological changes undergone by Escherichia coli in response to oxidative stress have been extensively studied (19, 70, 74). Since superoxide and H2O2 are central to the chemistry of the oxidative burst, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase are considered to be important aspects of bacterial defenses (2, 17, 20, 30, 32), but the overall responses are much more complicated than two enzymatic activities. In E. coli, 30 proteins are induced by external H2O2 (70). E. coli expresses two types of catalase, a periplasmic peroxidase-catalase (HPI, encoded by katG), and a cytoplasmic catalase (HPII, encoded by katF). E. coli exhibits 40 superoxide-inducible proteins, some of which are also inducible by H2O2 (28, 74). E. coli expresses three SODs: constitutive Fe-SOD, superoxide-inducible Mn-SOD (32), and periplasmic Cu-Zn SOD (5). The distinctive functions of the three enzyme types are not well understood. Heat shock proteins are induced by oxidative stress in E. coli and may play an important role through general mechanisms that protect cellular proteins from a wide variety of stress conditions (8, 26, 53, 69, 70).

Brucella species express a Mn-SOD in the cytoplasm (65) and a Cu-Zn SOD in the periplasm (66). The only known catalase activity is restricted to the periplasm (63). Due to their periplasmic location, Cu-Zn SOD and catalase are thought to be involved in protecting the bacteria from external sources of oxidative compounds (63). Deletion of the Brucella Cu-Zn SOD has only a moderate effect on survival in vivo (42, 71). A direct test of the importance of catalase in B. abortus has not been previously reported, although catalase activity has long been considered to be a virulence factor (36). In vitro studies with neutrophil extracts, showing that oxygen-dependent killing is more potent than oxygen-independent killing of B. abortus (55), and the observation that addition of exogenous catalase protects brucellae from being killed by cultured murine peritoneal macrophages and J774A.1 cells (39) indirectly confirm the importance of catalase to this species.

In this study, we directly explored the importance of the catalase gene in protecting B. abortus from oxidative stress, and we present evidence that catalase and Cu-Zn SOD are regulated in response to external H2O2 and superoxide.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and medium.

B. abortus strain 19, which is used as a cattle vaccine, and strain 2308 were obtained in lyophilized form from the National Animal Disease Center, Ames, Iowa, and reconstituted as instructed. Growing brucellae were maintained on tryptose agar (Difco). For two-dimensional (2-D) gel analysis, bacteria were grown in liquid minimal medium. Minimal medium was constituted as described by Gerhardt (25), except that glutamine replaced asparagine. The Cu-Zn SOD deletion mutant, S19ΔsodC, was described previously (71).

For adaptation experiments, B. abortus was grown on tryptose agar plates for 2 days. Bacteria were scraped from the agar and resuspended in tryptose broth. The cell concentration was adjusted to 0.01 absorbance at 600 nm (A600) unit. Cultures were pretreated with 1 mM H2O2, 100 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, plus 1 mM H2O2 for 1 h or left untreated, and then different concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (10 to 100 mM) were added. After 30 min of H2O2 treatment, diluted liquid culture was spread onto tryptose agar plates.

Gene replacement.

ColE1-based plasmids have been previously shown not to replicate in B. abortus (29). Plasmid pCat5 is based on pUC119, which has a ColE1 replication origin and a gene for ampicillin resistance. The catalase replacement plasmid (see Results) was introduced into B. abortus by electroporation, and double recombinants were selected for kanamycin resistance and ampicillin sensitivity. The procedure followed the method of Tatum et al. (71). Briefly, B. abortus was prepared by washing with water and kept frozen in 10% glycerol. A 2-μg portion of plasmid was mixed with Brucella and electroporated at a setting of 25 μF and 2.5 kV, with the pulser controller set at 200 Ω, using a Gene Pulser transfection apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories). After electroporation, bacteria were plated on tryptose agar containing 50 μg of kanamycin per ml and replica plated on tryptose agar containing 50 μg of ampicillin per ml.

2-D protein gel analysis.

The procedures for 2-D protein gel analysis were based on those of O'Farrell (51). The detailed methods are described in the Millipore manual (Millipore investigator 2-D electrophoresis system operating and maintenance manual, 1991, Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.). B. abortus strain 19 was grown to log phase (A600 of 0.2 to 0.5) in liquid minimal medium. Bacteria were divided among small tubes, and 50 μCi of [35S]methionine was added. Then, either nothing, 10 mM H2O2, or superoxide mixture (0.04 U of xanthine oxidase per ml, 10 mM xanthine) was added to the liquid cultures and the bacteria were incubated for 1 h. After the labeling, bacteria were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 5,000 × g. Bacteria were then mixed with sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer I (0.3% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.6 M β-mercaptoethanol, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.4]), boiled for 5 min, and treated with DNase and RNase for 10 min. The mixture was precipitated with 5% trichloroacetic acid to remove unincorporated radioactivity. Pellets were extracted with acetone to remove the trichloroacetic acid and redissolved in sample buffer containing 8 M urea, 3.2% NP-40, and 1.8% ampholytes, and 100,000 cpm of each sample was loaded on the first-dimension tube gel. Isoelectric focusing was done for 17 h at 1,000 V. Then, the first gel was placed on a 12% polyacrylamide second-dimension gel and run for 3.5 h at 14,000 mW per gel. Each gel was fixed with 5% acetic acid solution and placed on X-ray film after treatment with 1 M sodium salicylate for 30 min (14).

A series of exposures were taken to ensure that spot densities were within the working range of the film. Each fluorograph was scanned and analyzed with Millipore Bioimage software running on a Sun workstation. This software normalizes the density of each spot to the total spot density present on the film. The entire experiment was repeated three times. Values reported are from one complete set of experiments. The other experiments yielded similar but not identical results.

Western blot analysis.

Antibodies used for the Western blots were polyclonal rabbit antisera. Antisera for this study were developed in our laboratory and described in detail previously (10, 16, 27, 29, 62). The Western blot procedure used was based on that of Towbin et al. (72). After the 2-D gel electrophoresis had been performed, the proteins were electrophoretically transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (Micron Separations Inc.) membrane. The membranes were blocked with 1% nonfat dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The blots were incubated with one of the antisera (anti-catalase, anti-Cu-Zn SOD, anti-DnaK, or anti-GroEL) and then washed four times for 10 min with PBS containing 0.03% Tween 20. The membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Immuno Select Inc.) in PBS containing 1% nonfat milk and rinsed twice with 0.03% Tween 20 in PBS and twice with PBS. The blots were visualized by the color reaction (57) of H2O2 and 4-chloro-1-naphthol (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Catalase assay.

B. abortus was grown in tryptose broth to an A600 of 0.2 to 0.5. Then 10 mM H2O2 or superoxide mixture was added, and after 1 h the culture was centrifuged and resuspended in PBS. The resuspended cells were sonicated and filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size Millipore filter disc. Catalase activity was measured as described in the Worthington enzyme manual (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Freehold, N.J., 1972). Decomposition of hydrogen peroxide was measured spectrophotometrically at 240 nm. Measurements were made at 10-s intervals for the first 1 min after the cells were mixed with the substrate. One unit of catalase is defined as the amount catalyzing the decomposition of 1 μmol of hydrogen peroxide per min in 0.05 M hydrogen peroxide at 25°C.

Hydrogen peroxide sensitivity assays. (i) Liquid culture challenge.

Overnight cultures of B. abortus were diluted to 104 cells/ml in tryptose medium, and different amounts of H2O2 were added to each tube. After the contents were mixed, the tubes were incubated at room temperature for 15 min and the contents were diluted into tryptose broth containing 1 mg of bovine catalase per ml. The cultures were serially diluted and plated in duplicate. Colonies were counted after 3 days at 37°C.

(ii) Halo assay.

B. abortus culture was spread evenly on tryptose agar plates. A 5-mm-diameter filter disc was placed on the center of the plate. Then, various concentrations of H2O2 were applied to the filter discs. The diameter of the clear zone surrounding each filter disc was measured after 3 days of incubation at 37°C. Each experiment was done in triplicate and repeated at least three times.

RESULTS

Deletion mutants.

The Cu-Zn SOD deletion mutant (S19ΔsodC) of B. abortus strain 19 used in this study was previously described (71). Catalase deletion mutants of strains 2308 and strain 19 were constructed in a similar manner by gene replacement. Plasmid pCat5 (62), which contains the entire Brucella catalase coding sequence and flanking sequences, was doubly digested with BglII and PstI to remove 759 bp of the catalase coding region. The staggered ends were polished to blunt ends by incubation with the Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I, and the neomycin-kanamycin resistance gene from Tn5 was inserted into the plasmid, effectively replacing the 3′ half of the catalase gene in the plasmid (29). Both the 5′ and 3′ ends of the replacement were sequenced to confirm the construction. The resulting plasmid was electroporated into B. abortus, and kanamycin-resistant, ampicillin-sensitive colonies were selected and further tested by PCR and Southern blot analysis to confirm the gene deletion. The respective mutant strains are designated S2308Δcat and S19Δcat. Catalase deletion mutants did not express detectable levels of catalase activity.

Response of catalase deletion mutants to oxidative stress.

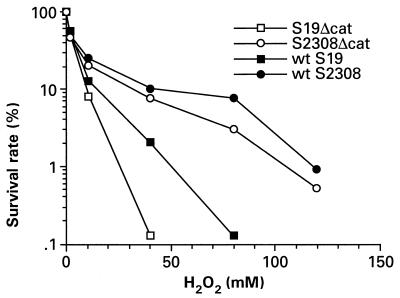

Survival of bacteria in response to oxidative stress is sensitive to the details of the experiment. Figure 1 compares the survival of the catalase-deficient strains when exposed to H2O2 while growing in liquid tryptose medium. H2O2 challenge in liquid culture represents an acute exposure for catalase-expressing strains since H2O2 is destroyed in a short time. Under these conditions, a functional catalase provides significant protection to strain 19 but is much less important to the survival of strain 2308.

FIG. 1.

Survival of strains 19, S19Δcat, 2308, and S2308Δcat in liquid culture. Bacteria were grown in liquid tryptose medium, different concentrations of H2O2 were added for 15 min, and the cultures were plated.

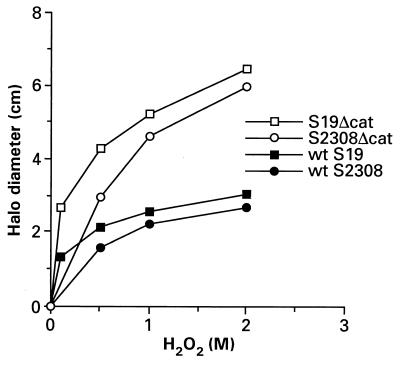

The halo assay provides a test of resistance to longer-term exposure to H2O2. In this test, a filter disc is placed on a lawn of newly seeded bacteria and different concentrations of hydrogen peroxide are applied to the discs. H2O2 diffuses from each disc, providing chronic exposure to different concentrations of H2O2 depending on the distance from the disc. The diameter of the clear zone surrounding each filter provides a measure of the bacterial sensitivity to the diffusing agent. Figure 2 shows that strain 2308 and strain 19 respond similarly and that catalase plays an important protective role for both strains in this assay.

FIG. 2.

Halo assay comparing the hydrogen peroxide sensitivities of strains 19 and S19Δcat. Liquid culture was grown to mid log phase and then spread on tryptose agar plates to form a bacterial lawn. A filter disc containing the indicated concentration of hydrogen peroxide was placed at the center of each plate. After incubation for 3 days, the clear zone surrounding each filter disc was measured and plotted against the hydrogen peroxide concentration.

Regulation of catalase in response to oxidative stress.

Standard stress conditions selected for this study were 10 mM H2O2 or 10 mM xanthine plus 0.04 U of xanthine oxidase per ml to generate superoxide, in tryptose medium. Because the response in minimal media is often different from that in rich media, the survival of B. abortus strain 19 in minimal medium plus 10 mM H2O2 for 1 h was tested. Under these conditions, the survival of strain 19 and the S19ΔsodC mutant was greater than 95% whereas the catalase deletion mutant, S19Δcat, was rapidly killed (data not shown). The survival of B. abortus strain 19 in minimal medium plus superoxide mixture for 1 h was 100% for the wild type and S19Δcat and 70% for S19ΔsodC.

Catalase enzyme activity increased approximately fourfold after 1 h of exposure to either 10 mM hydrogen peroxide or superoxide mixture (Table 1) in tryptose broth. This result indicates that the bacteria respond to this level of oxidative stress and that catalase activity is regulated.

TABLE 1.

Induction of catalase activity in Brucella strain 19 by 10 mM H2O2 or superoxide mixture for 1 h

| Treatment | Catalase activity (U/mg) | Increase (fold) |

|---|---|---|

| None (control) | 0.65 | |

| H2O2 | 2.35 | 3.6 |

| Superoxide mixture | 2.80 | 4.7 |

To confirm the apparent regulation of catalase, we conducted 2-D protein gel analysis. This technique also allowed a comparison of catalase expression with that of other polypeptides of interest. The 2-D gel system used typically resolves about 1,000 polypeptide spots. In this study, we used specific rabbit antisera to identify DnaK heat shock protein, GroEL heat shock protein, Cu-Zn SOD, and catalase on the 2-D gel electrophoresis pattern. Identification of the catalase and SOD spots was confirmed by comparison with 2-D gels of the S19Δcat and S19ΔsodC mutants. DnaK and GroEL were both revealed as multiple spots on 2-D gels, catalase was revealed as an elongated smear, and Cu-Zn SOD was revealed as a simple but minor spot.

Strain 19 wild type, S19ΔsodC, and S19Δcat were each grown in minimal medium until the A600 reached 0.2 to 0.5. Then 10 mM hydrogen peroxide or superoxide mixture was added to the culture along with [35S]methionine for 1 h, and 100,000 cpm of each pulse-labeled sample was subjected to 2-D gel analysis. The autoradiographs were analyzed with Millipore Bioimage software. As previously observed by others, many spots increased or decreased in intensity in response to oxidative stress (17, 43, 54). Focusing only on spots which changed intensity by 10-fold or more, 31 increased and 14 decreased in intensity in response to 10 mM H2O2 while 8 spots increased and 15 decreased in intensity in response to the superoxide mixture. The magnitude of this response is typical of bacteria which have been stressed.

The behavior of the four identified spots was different and is reported in Table 2. The heat shock proteins, DnaK and GroEL, exhibited little change (or a possible slight increase) in intensity. The intensity of the Cu-Zn SOD spot increased two- and fivefold in response to H2O2 and superoxide, respectively, and the catalase spots increased in intensity more than 10-fold (from slightly visible to a major streak) under both conditions. Because of the difficulty in clearly delimiting polypeptide spots from one another, the numbers should be considered approximate.

TABLE 2.

Observed polypeptide changes on 2-D gelsa

| Strain and treatment | Change observed for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GroEL | DnaK | Cu-Zn SOD | Catalase | |

| 19, H2O2 | Small | Small | 2-fold | >10-fold |

| 19, superoxide | Small | Small | 5-fold | >10-fold |

| S19Δcat, H2O2 | Small | Small | 3-fold | |

| S19Δcat, superoxide | Small | Small | 5-fold | |

| S19ΔsodC, H2O2 | Small | Small | >10-fold | |

| S19ΔsodC, superoxide | Small | Small | >10-fold | |

Integrated spot density increases following treatment.

The experiment was repeated for S19ΔsodC and S19Δcat. In general, deletion of the Cu-Zn SOD gene (S19ΔsodC) had only a minor effect on the spot pattern observed in response to oxidative stress. The overall changes in spot pattern were similar, and DnaK and GroEL behaved similarly to the wild type. Catalase was induced somewhat less by H2O2 and somewhat more by the superoxide mixture than for the wild type. These observations indicate that catalase induction is not dependent on Cu-Zn SOD.

Because S19Δcat was killed by 10 mM H2O2, 100 μM H2O2 was used to stimulate this mutant. Under these conditions, the overall spot pattern was quite similar with and without H2O2 stimulation, the DnaK and GroEL levels were unchanged, and Cu-Zn SOD was induced fivefold. The superoxide mixture also had little effect on DnaK and GroEL expression for this mutant, while Cu-Zn SOD expression was induced threefold.

Adaptation to external hydrogen peroxide.

Adaptation is an important strategy for bacterial survival in changing environments. To test for adaptation, log phase cultures of strain 19 growing in tryptose broth were divided into three groups of small cultures. One group received no pretreatment, one was exposed to 1 mM H2O2 for 1 h, and one was exposed to 1 mM H2O2 plus 100 μg of chloramphenicol per ml for 1 h. Immediately following pretreatment, either 0, 10, 20, 30, or 100 mM hydrogen peroxide was added and each culture was incubated for an additional 30 min, and the cultures were then plated. The results are presented in Table 3. The data show that simple pretreatment with a sublethal concentration of H2O2 provided dramatic protection. The amount of protection depended on the concentration of H2O2 in the challenge. With a 10 mM challenge, the protective effect was only 2-fold, while at 100 mM, pretreatment enhanced survival more than 25-fold. Chloramphenicol abrogated the protective effect of pretreatment, indicating that protein synthesis is required for adaptation.

TABLE 3.

Adaptation to hydrogen peroxide

| H2O2 treatment | % Survival after 30 min of H2O2 at:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 mM | 20 mM | 30 mM | 100 mM | |

| No pretreatment | 20.8 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.012 |

| Pretreatment | 44.6 | 6.4 | 4.3 | 0.45 |

| Pretreatment plus chloramphenicol | 33.0 | 1.2 | 0.26 | 0.017 |

DISCUSSION

It is well established that phagocytic cells release active oxygen species which kill invading bacteria. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide are toxic in their own right and are required for the production of more toxic molecules such as hydroxyl radical and HOCl (31, 33). Direct inactivation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide would seem to be an effective strategy for pathogenic bacteria. Because some bacteria such as Salmonella (23) and Brucella (21) survive inside phagocytes for prolonged periods, it seems likely that these species alter their metabolism in response to the phagocytic environment. In fact, previous studies have shown that both Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and B. abortus change their protein synthetic patterns when ingested by macrophages (17, 43, 54).

Pulse-labeling with [35S]methionine followed by 2-D gel electrophoresis gives a rough measure of synthetic rates for individual polypeptides. In this study, we determined the effect of H2O2 and superoxide on the synthetic rate of DnaK, GroEL, Cu-Zn SOD, and catalase by this technique. In one report on B. abortus strain 2308 (54), both DnaK and GroEL exhibited decreased protein expression after a 60-min exposure to 50 mM H2O2. In contrast, we found that the synthetic rate of DnaK and GroEL did not change in response to oxidative stress. Both studies agree that the synthetic rates of both DnaK and GroEL respond very little to oxidative stress. Abshire and Neidhardt (1) reported that S. enterica serovar Typhimurium DnaK, GroEL, and GroES production did not increase significantly in the phagocyte. Ericsson et al. (22) showed that Francisella tularensis DnaK production was increased about fivefold but GroEL production did not increase greatly when the organism was phagocytized by macrophages. In another study of phagocytosis, virulent strains of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium increased heat shock protein synthesis but avirulent strains did not (11). Even though it is difficult to compare 2-D gel electrophoresis results from different laboratories, it is clear that macrophage-induced proteins are quite often different from those induced by chemical stimulation in vitro. For B. abortus, heat shock proteins do not seem to change synthetic rates greatly in response to intracellular conditions or to external oxidative stress.

Our results indicate that expression of Cu-Zn SOD is increased two- to fivefold in log-phase bacteria in response to oxidative stress, with the higher stimulation in response to superoxide. Log-phase synthesis of this enzyme is never very high, as judged by the intensity of the 2-D gel spot. In contrast, synthesis of catalase increases from nearly invisible to a major spot pattern in response to both H2O2 and superoxide.

B. abortus expresses both Cu-Zn SOD and catalase in the periplasmic space. Because of the cellular location, we previously hypothesized that these two enzymes play a role in protecting the cells from external sources of oxidative damage (66). E. coli (44), Pseudomonas syringae (40), Sinorhizobium meliloti (64), and Bacillus subtilis (43a) are known to have more than one catalase, whereas Helicobacter pylori (50), Haemophilus influenzae (7), Bacteroides fragilis (56), and B. abortus (63) seem to have only one catalase. Brucella catalase exhibits sequence homology to the E. coli cytoplasmic catalase (HPII) but is regulated differently. Brucella catalase is regulated in response to external H2O2, in a manner similar to E. coli catalase-peroxidase (HPI) (59), H. influenzae catalase (7), and Rhizobium meliloti catalase A (34).

It has been reported that periplasmic Cu-Zn SOD protects cells from external superoxide in Caulobacter crescentus (67). Even though superoxide itself is not very toxic and in the ionized form cannot easily pass through membranes, it can react with H2O2 in the presence of transition metals to produce hydroxyl radical, which is very toxic to cells (3, 4, 35). Cu-Zn SOD is upregulated in response to external superoxide in C. crescentus (67). We report here that B. abortus Cu-Zn SOD is upregulated in response to oxidative agents. Under the conditions tested in this study, the increased synthesis of the enzyme was modest, no more than fivefold. This is less than the induction reported for C. crescentus (60, 67, 68) but does not rule out the possibility that regulation of Brucella Cu-Zn SOD might be more responsive under other growth conditions. For example, E. coli Cu-Zn SOD is expressed at high levels only very late in stationary phase (37). Several reports indicate that overexpression of SOD in the absence of a parallel increase in catalase expression causes cells to become more susceptible to oxidative damage (46, 61). This is probably because the product of Cu-Zn SOD activity, H2O2, is more toxic to cells than is superoxide. The observation that for B. abortus, both Cu-Zn SOD and catalase levels increase in response to superoxide is consistent with this principle.

Survival studies with the catalase deletion mutants (Fig. 1 and 2) clearly indicate that B. abortus catalase protects against hydrogen peroxide. Regulation of this enzyme is presumably one aspect of the adaptation process that allows the bacteria to survive under hostile conditions. During repeated experiments, we noticed that survival rates depended on cell density. This phenomenon is well documented in other species and is believed to be a consequence of the high diffusion rate of hydrogen peroxide (12, 45). In this study, the hydrogen peroxide stress condition (10 mM H2O2, A600 of 0.2 to 0.5) used for 2-D gel analysis resulted in greater than 90% survival. However, for the adaptation experiments (Table 2), only 20.8% of Brucella organisms survived in 10 mM H2O2 when the A600 was 0.01. The lower cell density was used for the adaptation experiment to reduce this density effect and to allow adaptation to be observed.

Adaptation may partially explain the different responses illustrated in Fig. 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows that strain 2308 is much more resistant to acute exposure to H2O2 whether or not catalase is present. The halo assay (Fig. 2) is based on prolonged exposure. Under these conditions, adaptation may play a more dominant role. Table 3 shows that adaptation can increase the resistance of strain 19 to H2O2 by 20-fold. This adaptive response is more than enough to account for the observation that strain 19 is nearly as resistant to H2O2 as is strain 2308 in the halo assay.

The data presented here indicate that B. abortus catalase and Cu-Zn SOD are regulated in response to oxidative stress and that under certain conditions the periplasmic catalase protects the bacteria from external hydrogen peroxide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abshire K Z, Neidhardt F C. Analysis of proteins synthesized by Salmonella typhimurium during growth within a host macrophage. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3734–3743. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3734-3743.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babior B M. Oxygen-dependent killing by phagocytes. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:659–668. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197803232981205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badwey J A, Karnovsky M L. Active oxygen species and the functions of phagocytic leukocytes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:695–726. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.003403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaman L, Beaman B L. The role of oxygen and its derivatives in microbial pathogenesis and host defense. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1984;38:27–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.38.100184.000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benov L T, Fridovich I. Escherichia coli expresses a copper- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25310–25314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertram T A, Canning P C, Roth J A. Preferential inhibition of primary granule release from bovine neutrophils by a Brucella abortus extract. Infect Immun. 1986;52:285–292. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.285-292.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bishai W R, Howard N S, Winkelstein J A, Smith H O. Characterization and virulence analysis of catalase mutants of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4855–4860. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4855-4860.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogelen R A V, Kelly P M, Neidhardt F C. Differential induction of heat shock, SOS, and oxidation stress regulons and accumulation of nucleotides in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:26–32. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.26-32.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braude A I. Studies in the pathology and pathogenesis of experimental brucellosis. II. The formation of the hepatic granuloma and its evolution. J Infect Dis. 1951;89:87–94. doi: 10.1093/infdis/89.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bricker B J, Tabatabai L B, Judge B A, Deyoe B L, Mayfield J E. Cloning, expression, and occurance of the Brucella Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2935–2939. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.2935-2939.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchmeier N A, Heffron F. Induction of Salmonella stress proteins upon infection of macrophages. Science. 1990;248:730–732. doi: 10.1126/science.1970672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchmeier N A, Libby S J, Xu Y, Loewen P C, Switala J, Guiney D G, Fang F C. DNA repair is more important than catalase for Salmonella virulence in mice. J Clin Investig. 1995;95:1047–1053. doi: 10.1172/JCI117750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canning P C, Roth J A, Deyoe B L. Release of 5′-guanosine monophosphate and adenine by Brucella abortus and their role in the intracellular survival of the bacteria. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:464–470. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamberlain J P. Fluorographic detection of radioactivity in polyacrylamide gels with the water-soluble fluor, sodium salicylate. Anal Biochem. 1979;98:132–135. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90716-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chance B, Sies H, Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chin E C L. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of Brucella abortus heat shock 70 gene. Ph.D. thesis. Ames: Iowa State University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christman M F, Morgan R W, Jacobson F S, Ames B N. Positive control of a regulon for defenses against oxidative stress and some heat-shock proteins in Salmonella typhimurium. Cell. 1985;41:753–762. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corbel M J. Brucellosis: epidemiology and prevalence worldwide. In: Young E J, Corbel M J, editors. Brucellosis: clinical and laboratory aspects. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1989. pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demple B. Regulation of bacterial oxidative stress genes. Annu Rev Genet. 1991;25:315–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.001531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demple B, Amabile-Cuevas C F. Redox redux: the control of oxidative stress responses. Cell. 1991;67:837–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enright F M. The pathogenesis and pathobiology of Brucella infection in domestic animals. In: Nielsen K, Duncan J R, editors. Animal brucellosis. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 301–320. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ericsson M, Tarnvik A, Kuoppa K, Sandstrom G, Sjostedt A. Increased synthesis of DnaK, GroEL, and GroES homologs by Francisella tularensis LVS in response to heat and hydrogen peroxide. Infect Immun. 1994;62:178–183. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.178-183.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fields P I, Groisman E A, Heffron F. A Salmonella locus that controls resistance to microbial proteins from phagocytic cells. Science. 1989;243:1059–1062. doi: 10.1126/science.2646710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frenchick P J, Markham R J F, Cochrane A H. Inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion in macrophages by soluble extracts of virulent Brucella abortus. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:332–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerhardt P. The nutrition of Brucella. Microbiol Rev. 1958;22:81–98. doi: 10.1128/br.22.2.81-98.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goff S A, Berg A J G. Production of abnormal proteins in E. coli stimulates transcription of lon and other heat shock genes. Cell. 1985;41:587–595. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gor D. Characterization and immunogenicity of the heat shock protein, hsp60, of Brucella abortus. Ph.D. thesis. Ames: Iowa State University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenberg J T, Monach P A, Chou J H, Josephy P D, Demple B. Positive control of a global antioxidant defense regulon activated by superoxide-generating agents in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6181–6185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halling S M, Detilleux P G, Tatum F M, Judge B A, Mayfield J E. Deletion of the BCSP31 gene of Brucella abortus by replacement. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3863–3868. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.3863-3868.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris E D. Regulation of antioxidant enzymes. FASEB J. 1992;6:2675–2683. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.9.1612291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hassan H M. Determination of microbial damage caused by oxygen free radicals and the protective role of superoxide dismutases. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:404–412. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hassan H M. Microbial superoxide dismutases. Adv Genet. 1984;26:65–97. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hassett D J, Cohen M S. Bacterial adaptation to oxidative stress:Implications for pathogenesis and interaction with phagocytic cells. FASEB J. 1989;3:2574–2582. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.14.2556311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herouart D, Sigaud S, Moreau S, Frendo P, Touati D, Puppo A. Cloning and characterization of the katA gene of Rhizobium meliloti encoding a hydrogen peroxide-inducible catalase. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6802–6809. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6802-6809.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang T-T, Carlson E J, Leadon S A, Epstein C J. Relationship of resistance to oxygen free radicals to CuZn-superoxide dismutase activity in transgenic, transfected, and trisomic cells. FASEB J. 1992;6:903–910. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.3.1740238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huddleson I F, Stahl W H. Catalase activity of the species of Brucella as a criterion of virulence. Mich Tech Bulp. 1943;182:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Imlay K R C, Imlay J A. Cloning and analysis of sodC, encoding the copper-zinc superoxide dismutase of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2564–2571. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2564-2571.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang X, Baldwin C L. Effects of cytokines on intracellular growth of Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1993;61:124–134. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.124-134.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang X, Leonard B, Benson R, Baldwin C L. Macrophage control of Brucella abortus: role of reactive oxygen intermediates and nitric oxide. Cell Immunol. 1993;151:309–319. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1993.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klotz M G, Hutcheson S W. Multiple periplasmic catalases in phytopathogenic strains of Pseudomonas syringae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2468–2473. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2468-2473.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kreutzer D L, Dreyfus L A, Robertson D C. Interaction of polymorphonuclear leukocytes with smooth and rough strains of Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1979;23:737–742. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.3.737-742.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Latimer E, Simmers J, Sriranganathan N, Roop II R M, Schurig G G, Boyle S M. Brucella abortus deficient in copper/zinc superoxide dismutase is virulent in BALB/c mice. Microb Pathog. 1992;12:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin J, Ficht T A. Protein synthesis in Brucella abortus induced during macrophage infection. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1409–1414. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1409-1414.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43a.Loewen P C, Switala J. Multiple catalases in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3601–3607. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3601-3607.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loewen P C, Switala J, Triggs-Raine B L. Catalase HPI and HPII in Escherichia coli are induced independently. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;243:144–149. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90782-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma M, Eaton J W. Multicellular oxidant defense in unicellular organisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7924–7928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mao G D, Thomas P D, Lopaschuk G D, Poznansky M J. Superoxide dismutase (SOD)-catalase conjugates. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:416–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCullough N B. Microbial and host factors in the pathogenesis of brucellosis. In: Mudd S, editor. Infectious agents and host reactions. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1970. pp. 325–345. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meyer M E. Current concepts in the taxonomy of the genus Brucella. In: Nielsen K, Duncan J R, editors. Animal brucellosis. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nicoletti P, Winter A J. The immune response to Brucella abortus: the cell mediated response to infections. In: Nielsen K, Duncan J R, editors. Animal brucellosis. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Odenbreit S, Wieland B, Haas R. Cloning and genetic characterization of Helicobacter pylori catalase and construction of a catalase-deficient mutant strain. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6960–6967. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6960-6967.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O'Farrell P H. High resolution two-dimentional elecrophoresis of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:4007–4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Payne J M. The pathogenesis of experimental brucellosis in the pregnant cow. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1959;78:447–463. doi: 10.1002/path.1700780211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pelham H R B. Speculation on the function of the major heat shock and glucose-regulating proteins. Cell. 1986;46:959–961. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90693-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rafie-Kolpin M, Essenberg R C, Wyckoff J H., III Identification and comparison of macrophage-induced proteins induced under various stress conditions in Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5274–5283. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5274-5283.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riley L K, Robertson D C. Brucellacidal activity of human and bovine polymorphonuclear leukocyte granule extracts against smooth and rough strains of Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1984;46:231–236. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.1.231-236.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rocha E R, Selby T, Coleman J P, Smith C J. Oxidative stress response in an anaerobe, Bacteroides fragilis: a role for catalase in protection against hydrogen peroxide. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6895–6903. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6895-6903.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sangari F J, García-Lobo J M, Agüero J. The Brucella abortus vaccine strain B19 carries a deletion in the erythritol catabolic genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:337–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schellhorn H E, Hassan H M. Transcriptional regulation of katE in E. coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4286–4292. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4286-4292.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schnell S, Steinman H M. Function and stationary-phase induction of periplasmic copper-zinc superoxide dismutase and catalase/peroxidase in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5924–5929. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5924-5929.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott M D, Meshnick S R, Eaton J W. Superoxide dismutase-rich bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:3640–3645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sha Z. Purification, characterization and cloning of a periplasmic catalase from B. abortus and the role it plays in the pathogenesis of Brucella. Ph.D. thesis. Ames: Iowa State University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sha Z, Stabel T J, Mayfield J E. Brucella abortus catalase is a periplasmic protein lacking a standard signal sequence. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7375–7377. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7375-7377.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sigaud S, Becquet V, Frendo P, Puppo A, Herouart D. Differential regulation of two divergent Sinorhizobium meliloti genes for HPII-like catalases during free-living growth and protective role of both catalases during symbiosis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2634–2639. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2634-2639.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sriranganathan N, Boyle S M, Schurig G G, Misra H. Superoxide dismutases of virulent and avirulent strains of Brucella abortus. Vet Microbiol. 1990;26:359–366. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(91)90029-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stabel T J, Sha Z, Mayfield J E. Periplasmic location of Brucella abortus Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase. Vet Microbiol. 1994;38:307–314. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)90149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Steinman H M. Function of periplasmic copper-zinc superoxide dismutase in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1198–1202. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1198-1202.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Steinman H M, Ely B. Copper-zinc superoxide dismutase of Caulobacter crescentus: cloning, sequencing, and mapping of the gene ane periplasmic location of the enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2901–2910. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.2901-2910.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Storz G, Imlay J A. Oxidative stress. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:188–194. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Storz G, Tartaglia L A, Farr S B, Ames B N. Bacterial defenses against oxidative stress. Trends Genet. 1990;6:363–368. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(90)90278-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tatum F M, Detilleux P G, Sacks J M, Halling S M. Construction of Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase deletion mutants of Brucella abortus: analysis of survival in vitro in epithelial and phagocytic cells and in vivo in mice. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2863–2869. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2863-2869.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Verger J M, Grimont F, Grimont P A D, Grayon M. Taxonomy of the genus Brucella. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol. 1987;138:235–238. doi: 10.1016/0769-2609(87)90199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Walkup L K B, Kogoma T. Escherichia coli proteins inducible by oxidative stress mediated by the superoxide radical. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1479–1484. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1476-1484.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Young E J, Borchert M, Kretzer F L, Musher D M. Phagocytosis and killing of Brucella by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:682–690. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.4.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]