Abstract

Background

Harmful alcohol use is defined as unhealthy alcohol use that results in adverse physical, psychological, social, or societal consequences and is among the leading risk factors for disease, disability and premature mortality globally. The burden of harmful alcohol use is increasing in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) and there remains a large unmet need for indicated prevention and treatment interventions to reduce harmful alcohol use in these settings. Evidence regarding which interventions are effective and feasible for addressing harmful and other patterns of unhealthy alcohol use in LMICs is limited, which contributes to this gap in services.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of psychosocial and pharmacologic treatment and indicated prevention interventions compared with control conditions (wait list, placebo, no treatment, standard care, or active control condition) aimed at reducing harmful alcohol use in LMICs.

Search methods

We searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) indexed in the Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group (CDAG) Specialized Register, the Cochrane Clinical Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and the Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) through 12 December 2021. We searched clinicaltrials.gov, the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, Web of Science, and Opengrey database to identify unpublished or ongoing studies. We searched the reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles for eligible studies.

Selection criteria

All RCTs comparing an indicated prevention or treatment intervention (pharmacologic or psychosocial) versus a control condition for people with harmful alcohol use in LMICs were included.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

We included 66 RCTs with 17,626 participants. Sixty‐two of these trials contributed to the meta‐analysis. Sixty‐three studies were conducted in middle‐income countries (MICs), and the remaining three studies were conducted in low‐income countries (LICs). Twenty‐five trials exclusively enrolled participants with alcohol use disorder. The remaining 51 trials enrolled participants with harmful alcohol use, some of which included both cases of alcohol use disorder and people reporting hazardous alcohol use patterns that did not meet criteria for disorder.

Fifty‐two RCTs assessed the efficacy of psychosocial interventions; 27 were brief interventions primarily based on motivational interviewing and were compared to brief advice, information, or assessment only. We are uncertain whether a reduction in harmful alcohol use is attributable to brief interventions given the high levels of heterogeneity among included studies (Studies reporting continuous outcomes: Tau² = 0.15, Q =139.64, df =16, P<.001, I² = 89%, 3913 participants, 17 trials, very low certainty; Studies reporting dichotomous outcomes: Tau²=0.18, Q=58.26, df=3, P<.001, I² =95%, 1349 participants, 4 trials, very low certainty). The other types of psychosocial interventions included a range of therapeutic approaches such as behavioral risk reduction, cognitive‐behavioral therapy, contingency management, rational emotive therapy, and relapse prevention. These interventions were most commonly compared to usual care involving varying combinations of psychoeducation, counseling, and pharmacotherapy. We are uncertain whether a reduction in harmful alcohol use is attributable to psychosocial treatments due to high levels of heterogeneity among included studies (Heterogeneity: Tau² = 1.15; Q = 444.32, df = 11, P<.001; I²=98%, 2106 participants, 12 trials, very low certainty).

Eight trials compared combined pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions with placebo, psychosocial intervention alone, or another pharmacologic treatment. The active pharmacologic study conditions included disulfiram, naltrexone, ondansetron, or topiramate. The psychosocial components of these interventions included counseling, encouragement to attend Alcoholics Anonymous, motivational interviewing, brief cognitive‐behavioral therapy, or other psychotherapy (not specified). Analysis of studies comparing a combined pharmacologic and psychosocial intervention to psychosocial intervention alone found that the combined approach may be associated with a greater reduction in harmful alcohol use (standardized mean difference (standardized mean difference (SMD))=‐0.43, 95% confidence interval (CI): ‐0.61 to ‐0.24; 475 participants; 4 trials; low certainty).

Four trials compared pharmacologic intervention alone with placebo and three with another pharmacotherapy. Drugs assessed were: acamprosate, amitriptyline, baclofen disulfiram, gabapentin, mirtazapine, and naltrexone. None of these trials evaluated the primary clinical outcome of interest, harmful alcohol use.

Thirty‐one trials reported rates of retention in the intervention. Meta‐analyses revealed that rates of retention between study conditions did not differ in any of the comparisons (pharmacologic risk ratio (RR) = 1.13, 95% CI: 0.89 to 1.44, 247 participants, 3 trials, low certainty; pharmacologic in addition to psychosocial intervention: RR = 1.15, 95% CI: 0.95 to 1.40, 363 participants, 3 trials, moderate certainty). Due to high levels of heterogeneity, we did not calculate pooled estimates comparing retention in brief (Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.00; Q = 172.59, df = 11, P<.001; I2 = 94%; 5380 participants; 12 trials, very low certainty) or other psychosocial interventions (Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.01; Q = 34.07, df = 8, P<.001; I2 = 77%; 1664 participants; 9 trials, very low certainty). Two pharmacologic trials and three combined pharmacologic and psychosocial trials reported on side effects. These studies found more side effects attributable to amitriptyline relative to mirtazapine, naltrexone and topiramate relative to placebo, yet no differences in side effects between placebo and either acamprosate or ondansetron.

Across all intervention types there was substantial risk of bias. Primary threats to validity included lack of blinding and differential/high rates of attrition.

Authors' conclusions

In LMICs there is low‐certainty evidence supporting the efficacy of combined psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions on reducing harmful alcohol use relative to psychosocial interventions alone. There is insufficient evidence to determine the efficacy of pharmacologic or psychosocial interventions on reducing harmful alcohol use largely due to the substantial heterogeneity in outcomes, comparisons, and interventions that precluded pooling of these data in meta‐analyses. The majority of studies are brief interventions, primarily among men, and using measures that have not been validated in the target population. Confidence in these results is reduced by the risk of bias and significant heterogeneity among studies as well as the heterogeneity of results on different outcome measures within studies. More evidence on the efficacy of pharmacologic interventions, specific types of psychosocial interventions are needed to increase the certainty of these results.

Keywords: Humans, Male, Acamprosate, Alcoholism, Alcoholism/prevention & control, Amitriptyline, Developing Countries, Disulfiram, Mirtazapine, Naltrexone, Ondansetron, Topiramate

Plain language summary

Interventions to reduce harmful alcohol use in low‐ and middle‐income countries

Why is this review important?

Harmful alcohol use is one of the main contributors to the global burden of disease. In low‐ and middle‐income countries, harmful alcohol use is increasing. However, services to prevent and treat harmful alcohol use are limited. One contributor to the lack of available services is the limited information about which intervention approaches are effective in reducing harmful alcohol use and whether these approaches are feasible and acceptable in low‐resource settings. In order to prevent the physical, psychological, and societal burden of harmful alcohol use, it is important that effective interventions are available to reduce alcohol‐related harm.

What is the goal of this review?

The goal of this review is to summarize evidence on whether psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions are able to reduce harmful alcohol use in low‐ and middle‐income countries. We also aim to evaluate the safety of treatments and how many people remain in treatment until its completion.

What does the research say?

We identified 66 randomized controlled trials that evaluated the effect of interventions on reducing harmful alcohol use. Most of these studies assessed psychosocial interventions (n = 52 studies), six assessed pharmacologic interventions alone, and eight assessed combined pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions.

The majority of included trials were funded by government agencies (36 trials) followed by multiple public and private funders (8 trials) or private foundations (5 trials). Seventeen trials did not report the funding source.

We are uncertain whether brief psychosocial interventions and other psychosocial interventions reduce harmful alcohol use. Combined pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions may reduce harmful alcohol use relative to psychosocial interventions combined with placebo, yet the certainty of the evidence has been assessed as low. No studies were found that looked at the effect of pharmacologic interventions alone on harmful alcohol use. We did not find evidence that rates of retention differed between study conditions for any of the intervention types.

Certainty of evidence: The certainty of evidence on the effect of brief and other psychosocial interventions on harmful alcohol use was very low due to lack of masking, differential attrition and missing data, selective outcome reporting, high heterogeneity, and differences in patient populations. The certainty of evidence on the effect of combined pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions on harmful alcohol use was low due to lack of blinding, incomplete outcome data, and heterogeneity in the pharmacologic interventions under investigation. No studies evaluated the effect of pharmacologic interventions alone on harmful alcohol use.

The evidence is current to 12 December 2021.

What are the next steps?

Future research on interventions to reduce harmful alcohol use is needed to address some of the limitations described in this review. Studies evaluating similar interventions across studies and contexts are needed to improve generalizability and understand the necessary characteristics of and conditions for effective intervention. Studies must utilize measurement tools that are valid in the population they are studying. Lastly, studies must be designed to reduce the risk of bias leading to the high degree of uncertainty in the results reported in this review.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Pharmacologic intervention compared to placebo for individuals with alcohol use disorder.

| Pharmacologic intervention compared to placebo for individuals with alcohol use disorder | |||||

| Patient or population: individuals with alcohol use disorder Setting: Low‐ and middle‐income countries Intervention: Pharmacologic intervention Comparison: placebo | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) Follow‐up | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk difference with Pharmacologic intervention | ||||

| Harmful alcohol use | 0 (0 RCTs) | ‐ | not estimable | Study population | |

| 0 per 1,000 | 0 fewer per 1,000 (0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ||||

| Retention | 247 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1 2 | RR 1.13 (0.89 to 1.44) | Study population | |

| 562 per 1,000 | 73 more per 1,000 (62 fewer to 247 more) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1 Variability in study conditions (experimental and/or comparison groups)

2 Includes the null, small sample size, and appreciable benefit and harm included in confidence interval

Summary of findings 2. Pharmacologic intervention along with psychosocial intervention compared to psychosocial intervention alone for individuals with alcohol use disorder.

| Pharmacologic intervention along with psychosocial intervention compared to psychosocial intervention alone for individuals with alcohol use disorder | |||||

| Patient or population: individuals with alcohol use disorder Setting: Low‐ and middle‐income countries Intervention: Pharmacologic intervention along with psychosocial intervention Comparison: psychosocial intervention alone | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) Follow‐up | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with psychosocial intervention alone | Risk difference with Pharmacologic intervention along with psychosocial intervention | ||||

| Harmful alcohol use (continuous) | 475 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1 2 | ‐ | The mean harmful alcohol use (continuous) was 0 SD | SMD 0.43 SD lower (0.61 lower to 0.24 lower) |

| Harmful alcohol use (dichotomous) | 102 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1 3 | RR 0.62 (0.16 to 2.47) | Study population | |

| 96 per 1,000 | 37 fewer per 1,000 (81 fewer to 141 more) | ||||

| Retention | 363 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 3 | RR 1.15 (0.95 to 1.40) | Study population | |

| 491 per 1,000 | 74 more per 1,000 (25 fewer to 196 more) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1 High risk of bias due to limited blinding of participants, personnel, and/or outcome assessors. Most studies reported incomplete outcome data with high or unclear risk of bias

2 Different pharmacologic interventions evaluated across studies for this outcome

3 Includes the null, small sample size, and appreciable benefit and harm included in the confidence interval

Summary of findings 3. Pharmacologic intervention compared to another pharmacologic intervention for individuals with alcohol use disorder.

| Pharmacologic intervention compared to another pharmacologic intervention for individuals with alcohol use disorder | |||||

| Patient or population: individuals with alcohol use disorder Setting: Low‐ and middle‐income countries Intervention: Pharmacologic intervention Comparison: another pharmacologic intervention | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) Follow‐up | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with another pharmacologic intervention | Risk difference with Pharmacologic intervention | ||||

| Harmful alcohol use ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Retention | 190 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1 | RR 0.95 (0.76 to 1.19) | Study population | |

| 873 per 1,000 | 44 fewer per 1,000 (209 fewer to 166 more) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval;RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1 Differences in comparators

Summary of findings 4. Pharmacologic intervention compared to another pharmacologic intervention in addition to psychosocial intervention for individuals with alcohol use disorder.

| Pharmacologic intervention compared to another pharmacologic intervention in addition to psychosocial intervention for individuals with alcohol use disorder | |||||

| Patient or population: individuals with alcohol use disorder Setting: Low‐ and middle‐income countries Intervention: Pharmacologic intervention Comparison: another pharmacologic intervention in addition to psychosocial intervention | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) Follow‐up | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with another pharmacologic intervention in addition to psychosocial intervention | Risk difference with Pharmacologic intervention | ||||

| Harmful alcohol use ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Retention | 200 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1 | RR 1.02 (0.96 to 1.08) | Study population | |

| 940 per 1,000 | 19 more per 1,000 (38 fewer to 75 more) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1 Different comparators

Summary of findings 5. Brief interventions compared to brief advice, information, or assessment only for individuals with hazardous or harmful alcohol use.

| Brief interventions compared to brief advice, information, or assessment only for individuals with hazardous or harmful alcohol use | |||||

| Patient or population: individuals with hazardous or harmful alcohol use Setting: Low‐ and middle‐income countries Intervention: Brief interventions Comparison: brief advice, information, or assessment only | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) Follow‐up | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with brief advice, information, or assessment only | Risk difference with Brief interventions | ||||

| Harmful alcohol use (continuous) | 3913 (17 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1 2 3 | ‐ | The mean harmful alcohol use (continuous) was 0 SD | see comment |

| Harmful alcohol use (dichotomous) | 1349 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1 2 3 | not pooled | Study population | |

| not pooled | not pooled | ||||

| Retention | 5380 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1 2 3 | not pooled | Study population | |

| not pooled | not pooled | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1 Lack of blinding of participants, personnel, and/or outcome assessor

2 High levels of heterogeneity

3 Differences in comparison condition and, to a lesser extent, the brief interventions

Summary of findings 6. Other psychosocial intervention compared to usual care, brief intervention, or wait list for individuals with hazardous or harmful alcohol use.

| Other psychosocial intervention compared to usual care, brief intervention, or wait list for individuals with hazardous or harmful alcohol use | |||||

| Patient or population: individuals with hazardous or harmful alcohol use Setting: Low‐ and middle‐income countries Intervention: Other psychosocial intervention Comparison: usual care, brief intervention, or wait list | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) Follow‐up | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with usual care, brief intervention, or wait list | Risk difference with Other psychosocial intervention | ||||

| Harmful alcohol use | 2106 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1 2 3 | ‐ | The mean harmful alcohol use was 0 | see comment |

| Retention | 1664 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1 2 3 4 | not pooled | Study population | |

| not pooled | not pooled | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval;RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1 High risk of bias due to lack of blinding participants, personnel, and/or outcome assessors

2 High levels of heterogeneity in estimated effects

3 Variability in experimental and control conditions

4 Appreciable risk and benefit

Background

Description of the condition

Harmful alcohol use, which is broadly defined by the World Health Organization as an unhealthy pattern of alcohol use that "causes detrimental health and social consequences for the drinker, the people around the drinker and society a large, as well as patterns of drinking that are associated with increased risk for adverse health consequences" (WHO 2010), is responsible for more harm to individuals and communities collectively than any other substance type and is among the leading causes of disability and premature mortality worldwide (Murray 2012; Whiteford 2013; Connor 2016). Harmful alcohol use encompasses a spectrum of unhealthy patterns of alcohol use including hazardous drinking, single episodes of harmful alcohol use, harmful drinking patterns, and alcohol use disorder (including alcohol dependence; WHO 2018a; WHO 2010). Individuals are considered to meet criteria for alcohol use disorder when their harmful patterns of alcohol use "lead to clinically significant impairment or distress" (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Definitions and terminology used to describe unhealthy patterns of alcohol use and disorder vary across diagnostic classification systems (American Psychiatric Association 2013; WHO 2018b). However, all definitions include alcohol‐related harms and consequences as a necessary criterion for alcohol use disorder. Thus, for this review, we consider harmful alcohol use to encompass unhealthy patterns of alcohol use that lead to physical, psychological, social, or societal consequences. Other forms of harmful alcohol use that may not meet diagnostic criteria for disorder include hazardous alcohol use, misuse, problem drinking, risky drinking, and heavy episodic/binge‐drinking. These sub‐threshold patterns of harmful alcohol use also contribute substantially to the biologic, psychological, and social harms of alcohol globally despite not meeting clinical criteria for alcohol use disorder (WHO 2014). In this review we focus on interventions that aim to reduce harmful alcohol use either by preventing the transition from sub‐threshold patterns of unhealthy alcohol use to disorder, or the treatment of alcohol use disorder.

Harmful patterns of alcohol use are associated with over 200 other adverse health and social conditions, including liver disease, cancer, cardio‐ and cerebrovascular disease, epilepsy, injury, interpersonal violence, and others (Nutt 2010; Medina‐Mora 2016). Data from the Global Burden of Disease Study found alcohol use to be the leading risk factor for disease and injury among people up to 49 years of age globally, and the leading risk factor in Eastern Europe, Andean Latin America, and southern Africa. Furthermore, alcohol use was responsible for 2,735,511 deaths in 2010, which represents a rise in number and risk factor ranking since the late 1990s (Lim 2012). These challenges disproportionately and increasingly affect low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) where the majority of premature mortality attributable to alcohol use occurs (Medina‐Mora 2016; Ferreira‐Borges 2017). Despite the lower, but increasing prevalence of harmful alcohol use in many LMICs relative to high‐income countries (HICs) in Australia, Europe, and North America, the harm derived from the same levels of alcohol consumption are greater in LMICs due to higher risk drinking patterns and more prevalent and severe alcohol‐related health consequences, such as unintentional injury, in these settings (Anderson 2006; Degenhardt 2008; Medina‐Mora 2016). Certain subgroups also experience an elevated burden related to harmful drinking in LMICs. For example, women in many LMICs experience greater social consequences of harmful drinking relative to women in most HICs given that alcohol use is sometimes seen as socially or culturally inappropriate for women (Medina‐Mora 2001). Furthermore, despite the lower prevalence of alcohol use among women in LMICs, women in some LMICs who do drink, including during high‐risk periods such as pregnancy, engage in more harmful patterns of drinking (Popova 2017). There is a similar pattern for people of low socioeconomic status. Although the prevalence of any drinking tends to be lower among low socioeconomic groups, those who report any alcohol use tend to participate in more harmful patterns of drinking, which increases their vulnerability to alcohol‐related consequences, despite having fewer resources to cope and to access health and social services (Room 2002; Johnson 2019).

Given the biologic, psychological, and social burden attributable to harmful alcohol use and its role as a causal risk factor in an array of prevalent health conditions, identifying effective interventions to reduce harmful alcohol use through treatment and indicated prevention are critically important. Furthermore, examining evaluations of a broad range of interventions in LMICs is important as contextual factors unique to these settings may modify their feasibility, acceptability, and clinical effectiveness.

Description of the intervention

Interventions to reduce harmful alcohol use include pharmacologic interventions for alcohol use disorder, psychosocial interventions for hazardous and harmful alcohol use (i.e. non‐pharmacologic and 12‐step programs), and combined (i.e. pharmacologic and psychosocial) strategies. Guidelines often recommend combined interventions for individuals with alcohol use disorder (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment 2009); however, whether to provide pharmacologic, psychosocial, or combined interventions should be informed by the person's treatment goals (e.g. abstinence, moderation), preferences, and what is locally available and acceptable (Connor 2016; Soyka 2017).

Pharmacologic treatments

Pharmacologic treatments approved and recommended for the treatment of alcohol use disorder and dependence include disulfiram, naltrexone, and acamprosate (Table 7; Kleber 2006; WHO 2011; NICE 2011; Franck 2013; Winslow 2016). Disulfiram is an oral medication administered daily that produces significant unpleasant biologic reactions when alcohol is consumed. This aversive medication is intended to promote abstinence and prevent impulsive drinking via anticipation of its adverse effects (Skinner 2014). Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, can be administered daily through its oral formulation or monthly via injection. Naltrexone is designed to reduce the euphoric effects of alcohol, thereby attenuating subsequent craving (Rosner 2010a). Acamprosate is intended for maintenance of abstinence among people with alcohol dependence who have undergone detoxification. It is administered orally three times per day and reduces symptoms of protracted abstinence including anxiety, insomnia, dysphoria, and craving (Plosker 2015). Other pharmaceuticals including nalmefene, baclofen, and topiramate are under evaluation by regulatory agencies or early‐stage clinical trials to assess their efficacy in treating alcohol dependence (Minozzi 2018; Franck 2013).

1. Summary of medication assisted treatment approved for harmful alcohol use.

| Medication | Administration | Indication | Intended effect |

| Acamprosate | Oral (3 times daily) | Maintenance of abstinence from alcohol | Reduces symptoms of protracted abstinence (e.g. anxiety, craving) |

| Disulfiram | Oral (once daily) | Promote abstinence from alcohol | Produces adverse effects when alcohol is consumed |

| Naltrexone | Oral (once daily) Injection (once monthly) |

Prevent alcohol craving | Reduces the euphoric effects of alcohol |

Psychosocial interventions

Psychosocial interventions include all non‐pharmacologic interventions. Psychosocial interventions recommended for the indicated prevention and treatment of varying levels of harmful alcohol use severity include psychological treatments, 12‐step facilitation (TSF) programs, and brief interventions (Hamza 2014). Historically, in HICs, mutual‐help organizations, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, were developed out of a lack of available and accessible services in the general population. This was followed by a rise in alcohol treatment centers and providers, which served as the foundation for the development and evaluation of psychological interventions for harmful alcohol use beginning in the mid‐20th century (McCrady 2014). Currently, there is a range of psychological and behavioral interventions available for treatment of harmful alcohol use including cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT), psychodynamic therapies, relapse prevention, contingency management, community reinforcement, TSF, family therapy, and brief interventions (including motivational interviewing). The theoretical orientations underpinning these interventions have followed ideological shifts in clinical psychology beginning with psychoanalytic approaches, which were popularized in the 1940s, to skills‐ and motivation‐based cognitive‐behavioral therapies. These interventions vary in their purported mechanisms of behavior change, delivery format (e.g. individual versus group‐based), duration, frequency, and provider (Kleber 2006). For the purpose of this review we differentiate brief interventions from other psychosocial treatment interventions. Brief interventions may include indicated prevention interventions aimed to prevent to the transition from hazardous alcohol use to harmful alcohol use, including alcohol use disorder, and have also been tested as a treatment strategy. Generally, these interventions apply motivational interviewing techniques, are shorter in duration relative to other psychosocial interventions, and include individuals with sub‐threshold harmful alcohol use (i.e., hazardous alcohol use) with the intention of preventing the onset of alcohol use disorder. We classified the remaining non‐pharmacologic interventions as 'other psychosocial interventions', which often focus on reducing harmful alcohol use using the range of psychological and behavioral modalities described above.

Mutual‐help organizations include traditional 12‐step programs, secular mutual‐help organizations, and other religious mutual‐help organizations. Alcoholics Anonymous, the largest community‐based 12‐step organization for alcohol‐related problems, aims to strengthen emotional, social, and spiritual coping strategies through peer support groups and step‐work (Greenfield 2013). Non‐12‐step mutual‐help organizations include secular groups that focus on non‐spiritual coping strategies for recovery (e.g. SMART (Self‐Management And Recovery Training) Recovery) as well as other religious groups that are not based on the 12‐step framework (e.g. Celebrate Recovery), but do maintain spirituality as a central component of their groups and discussion (Humphreys 2004). These groups have been incorporated into treatment systems through TSF approaches; however, 12‐step groups may also be accessed without engagement through the formal treatment system (Tonigan 2003). The evolution of psychosocial interventions has been well documented in high‐income settings, but little is known about the implementation and utilization of these and other approaches in LMICs (National Institute on Drug Abuse 2000).

Combined pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions

Guidelines for treatment of alcohol use disorder often recommend providing pharmacologic treatment in combination with psychosocial approaches. Combining these intervention modalities is believed to improve compliance with medication, enhance person's willingness to engage in psychosocial treatments and maintain or increase periods of abstinence and promote successful treatment outcomes (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment 2009).

How the intervention might work

In this review we included indicated prevention and treatment interventions to reduce harmful alcohol use. Indicated prevention interventions focus on preventing the transition from hazardous to harmful alcohol use. Treatment interventions aim to increase remission (i.e. abstinence or low‐risk drinking) and reduce harmful alcohol use among individuals with alcohol use disorder. Both indicated prevention and treatment interventions were included because some treatment modalities, particularly brief motivation‐based psychosocial modalities, are used as both indicated prevention and treatment strategies for people with hazardous or harmful alcohol use (NICE 2011). The mechanisms by which these interventions are expected to work vary by type of intervention. Pharmacologic interventions aim to alter the reward system by reducing stimuli that positively reinforce drinking or introducing aversive stimuli that counter‐condition alcohol use (Douaihy 2013). Psychosocial interventions are intended to reduce harmful alcohol use or prevent alcohol use disorder through several mechanisms. Psychosocial treatments for harmful alcohol use (e.g. CBT, contingency management, relapse prevention) are largely predicated on the theory that alcohol use and misuse is reinforced by internal and external cues, psychological and physical responses to alcohol consumption, and lack of adaptive coping skills. Thus, these interventions aim to modify conditioned responses to triggers, reinforce abstinent or moderated drinking behaviors, strengthen adaptive coping skills that reduce harmful alcohol use, or a combination of these (McCrady 2014). Brief motivation‐based interventions aim to increase one's motivation for behavior change through personalized feedback, participant‐directed behavior change and goal‐setting, regardless of the person's readiness to change their alcohol use (Miller 1983; Rollnick 1992). TSF programs encourage participation in self‐ and mutual‐help organizations (e.g. Alcoholics Anonymous), which aim to reduce alcohol use via changes in the composition of one's social network, increases in abstinence self‐efficacy and spirituality, and reductions in negative affect (National Institute on Drug Abuse 2000; Kelly 2012; Humphreys 2014).

Why it is important to do this review

Effective treatment and prevention of harmful alcohol use has significant potential to reduce the burden of disease globally. Populations in LMICs display unique epidemiological patterns of alcohol use and related consequences, socio‐cultural contexts and norms, and health care delivery systems (WHO 2014), all of which have implications for intervention implementation, acceptability, and efficacy. With the disproportionately high burden in LMICs coupled with the lack of evidence regarding effectiveness of treatment and prevention programs in these countries and the large treatment gap (Benegal 2009), a review focused on the treatment and indicated prevention of harmful alcohol use in these settings is needed.

The need for this review is evidenced by the recent increase in the number of published systematic reviews of alcohol interventions for a subset of interventions, populations, or settings that are covered in the current review. These reviews include one systematic review and one meta‐analysis of the efficacy or effectiveness of brief interventions for harmful and hazardous alcohol use in low‐ and/or middle‐income countries (Ghosh 2022;Joseph 2017). These reviews suggest an initial benefit of brief interventions on reducing hazardous and harmful alcohol use that attenuates over time with some heterogeneity explained by the intervention dose and provider type (Ghosh 2022). Both of these reviews noted the heterogeneity among included studies; however, there was mixed agreement on the methodological quality of included studies (Ghosh 2022; Joseph 2017). Two additional reviews examined the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions more generally on hazardous and harmful alcohol use in Sub‐Saharan Africa and LMICs, respectively (Preusse 2020; Sileo 2021). The systematic review and meta‐analysis conducted in Sub‐Saharan Africa identified 19 intervention trials (including randomized and non‐randomized designs) of moderate quality that showed some evidence of the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for promoting the odds of abstinence, but did not identify effects on hazardous or harmful alcohol use or consumption. The authors also noted the substantial heterogeneity that was present across all meta‐analytic models (Sileo 2021). The systematic review that included 21 randomized controlled trials of psychosocial interventions in LMICs reported small effect sizes and clear gaps in coverage of specific populations, such as conflict‐affected populations (Preusse 2020). The current review aims to cover a broader set up interventions (including pharmacologic and combined psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions) and explore a range of factors that explain heterogeneity in the observed effects. This review will add to this growing evidence of the efficacy of psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions for reducing harmful alcohol use in LMICs.

Systematic reviews of population‐level interventions for alcohol use and misuse have been conducted focusing primarily on supply‐side policy strategies (e.g. alcohol prohibition, regulation of alcohol outlets and advertisement, taxation) and have found promising results for reducing alcohol consumption and related harms (Sornpaisarn 2013; Medina‐Mora 2016; Petersen 2016). These types of interventions have great public health impact, but are less likely to be effective for addressing the challenges for individuals with harmful alcohol use. Economic analysis of addictive behaviors has found demand to be less responsive to price increases or supply‐side regulations (i.e. lower price elasticity of demand) in people with a substance use disorder relative to consumers without problematic use (Xu 2011).

Despite the treatment and prevention of harmful alcohol use being recognized as a public health and global mental health priority, there is still a dearth of evidence regarding what is most effective for treating harmful alcohol use and disorder within the unique context of LMICs, which often face limited availability of treatment and services, high levels of adversity, and increasingly severe alcohol use patterns and related consequences (Baingana 2015; Medina‐Mora 2016).

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of psychosocial and pharmacologic treatment and indicated prevention interventions compared with control conditions (wait list, placebo, no treatment, standard care, or active control condition) aimed at reducing harmful alcohol use in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

This review included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in LMICs. We excluded observational studies, quasi‐experimental studies, implementation and process evaluation studies (i.e. containing no outcome evaluation), and population‐level interventions.

Types of participants

We included studies that enrolled individuals with harmful alcohol use. Consistent with the definition provided by the World Health Organization (WHO), this includes individuals with patterns of alcohol use that "causes detrimental health and social consequences for the drinker, the people around the drinker and society a large, as well as patterns of drinking that are associated with increased risk for adverse health consequences" (WHO 2010). Therefore, we include participants with a range of unhealthy patterns of alcohol use including hazardous drinking, single episodes of harmful alcohol use, harmful drinking patterns, and alcohol use disorder (including alcohol dependence; WHO 2018a; WHO 2010). We excluded studies enrolling participants with no or low‐risk alcohol use, unless subgroup analyses for the participants with harmful alcohol use at baseline were reported. We included studies of all age groups and applied no restrictions based on demographic characteristics. We defined LMICs using the World Bank Country Lending Group classification of a given country at the time the study was conducted (World Bank 2015). For the 2018 fiscal year, the World Bank defined LMICs as those with a Gross National Income per capita less than USD 12,336 (approximately two‐thirds of countries in the world); however, this cutoff is adjusted each year to account for inflation and changes in exchange rates (World Bank 2017). Studies conducted in countries that were classified as low‐income, lower‐middle‐income, or upper‐middle‐income during the period of study recruitment were included. Historical data on Gross National Income per capita as well as the World Bank cutoffs for classifying countries as low‐, middle‐, or high‐income are available through the World Bank DataBank Development Indicators (World Bank 2021).

Types of interventions

Any type of individual level pharmacologic or psychosocial intervention, or combination therein, focused on treatment or indicated prevention of harmful alcohol use were included. Pharmacologic interventions specifically focused on treating individuals who met criteria for alcohol use disorder; whereas, psychosocial interventions included those meeting criteria for alcohol use disorder or individuals with unhealthy drinking patterns who were at high risk for alcohol use disorder. We did not include policy interventions or universal campaigns (e.g. media awareness programs). We excluded universal and selective prevention programs targeting the prevention of any alcohol use. Indicated prevention programs were included if they focused on preventing the onset of alcohol use disorder among individuals with high levels of risk based on their current drinking patterns.

We included studies with active (i.e. comparative effectiveness) and inactive (e.g. no‐treatment, placebo, standard care, wait‐list) control groups.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Reduction in harmful alcohol use. We selected this as the primary outcome given that this outcome has been commonly used in research on alcohol use in LMICs (Ghosh 2022; Joseph 2017; Preusse 2020; Sileo 2021). Harmful alcohol use must have been measured using a self‐report measurement tool.

Retention, defined as number of participants who completed treatment.

Secondary outcomes

Change in alcohol consumption (self‐report or biomarker) compared across studies with similar time scales.

Remission compared across studies with similar time scales. Remission was defined as the number of participants with a prior history of harmful alcohol use who were abstinent, did not relapse, or were classified as low‐risk drinkers at follow‐up (Grella 2013).

Adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

We aimed to identify all relevant RCTs regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Electronic searches

Published, unpublished, and ongoing studies were identified by searching the following databases from their inception:

Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group (CDAG) Specialized Register (most recent);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (2021, issue12);

PubMed (from 1946 to 12 December 2021);

Embase (Ovid) (from January 1974 to 12 December 2021);

PsycINFO (EBSCOhost) (from 1800 to 12 December 2021);

CINAHL (EBSCOhost) (from 1982 to 12 December 2021);

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/trialsearch);

Latin American & Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) (from 1982 to 12 December 2021).

The search strategies for each database are provided in Appendices 1‐10. Where appropriate, these were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying RCTs and controlled clinical trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Box 6.4.b.; Higgins 2011).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of all included studies and relevant review articles identified during the screening process for other eligible studies. We searched the Opengrey database to identify unpublished literature that met our eligibility criteria (opengrey.edu). We searched Web of Science to identify studies not available in English or the other databases included in the search strategy, or both.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts using Covidence (Covidence) with discrepancies resolved through discussion or, if necessary, by a third review author. We excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same trial, so that each trial rather than each report was the unit of analysis in the review. Review authors classified studies as 'yes' if the title and abstract discussed alcohol use, an alcohol treatment or indicated prevention intervention, and LIMICs. Studies were labeled 'maybe' if they mentioned alcohol use, an intervention, and LMICs, or if the study setting was unclear. Studies were marked 'no' if they were not RCTs or intervention studies, if they did not mention alcohol or substance use, or if they were conducted in HICs. We retained all articles classified as 'yes' or 'maybe' for full‐text review. Two review authors independently screened the full text of retained articles based upon the full eligibility criteria. Studies were classified as 'eligible' at this stage if they fit the criteria outlined in the Criteria for considering studies for this review section. Full‐text review screening was similarly completed using Covidence (Covidence).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently entered study characteristics and data into piloted and standardized forms. The review authors piloted the data extraction forms on five included studies and any modifications to the forms were made prior to data extraction for the remaining studies. Any discrepancies in data extraction were reviewed and, if necessary, arbitrated by a third review author. We collected and entered the following data from all included studies.

Methods: study design, randomization, allocation concealment procedures, blinding, eligibility criteria, study setting/location, duration of follow‐up, informed consent procedures, and ethical approvals.

Participant characteristics: age group, sex, race/ethnicity or other indicators of ancestry, marital status, baseline harmful alcohol use, co‐occurring disorders, sample size, description of the target population, including whether the intervention targeted certain special populations (e.g. HIV‐infected, women during the perinatal period, etc.).

Interventions: type of intervention (pharmacologic, psychological, brief, mutual‐help, etc.), brief description of intervention, duration of intervention, frequency of intervention, intervention delivery and provider, comparison group.

Outcomes: harmful alcohol use, retention, alcohol consumption, remission, adverse events, measurement tool, summary measures of central tendency/variance, timing of outcome ascertainment.

Results: total number of participants randomized, missing data, post‐treatment mean and variance/standard deviation/standard error for continuous outcomes, group count, and proportions for categorical outcomes.

Country.

Study funding and conflict of interest of study's authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently evaluated the included studies for risk of bias according to the parameters recommended by Cochrane (Higgins 2011). The criteria examined for risk of bias were random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and personnel; blinding of outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; and selective outcome reporting. These parameters are described in more detail below.

Random sequence generation referred to the method used to randomize people to study conditions. Adequate random sequence generation that was considered low risk of bias included use of a random number generator or random number table. Improper (e.g. allocation by date) or lack of random sequence generation may introduce selection bias. Thus, we labeled studies with inadequate methods of random sequence generation at high risk of bias. We labeled risk of bias as unclear if the study did not report their method of random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment referred to methods that prevent study personnel from foreseeing participant study assignments. Adequate allocation concealment, which we labeled as having low risk of bias included methods such as central allocation or the use of sequentially numbered opaque, sealed envelopes/drug containers that contained study assignments. Methods with a high risk of bias included those that produced a predictable pattern of allocation (e.g. date of birth) or when the allocation sequence was available to study personnel prior to allocation. We labeled a study as having unclear risk of bias if allocation concealment methods were not described or if it was unclear whether the method would prevent anticipating the allocation of participants. Poor allocation concealment may result in selection bias.

Blinding of participants and personnel referred to preventing the participants and study personnel from being aware of the participant's study condition as a means to reduce performance bias. Study personnel here referred to those that delivered the intervention. Unblinding participants and personnel may have impacted engagement, intervention fidelity, interactions between the participant and personnel, outcome reporting, or a combination of these, all of which may have induced performance bias. Blinding of participants and personnel is very challenging particularly for psychosocial interventions. We classified studies as low risk of bias if the participants and personnel were blinded to study condition. In contrast, we classified studies as high risk of bias if the participants or study personnel, or both, were unblinded. If this information was not included in the manuscript for interventions that could reasonably be blinded, we labeled risk of bias as unclear. Non‐pharmacologic interventions that were impossible to blind due to the nature of the intervention were automatically considered at high risk of bias.

Blinding of outcome assessors referred to preventing the study personnel involved in data collection from being aware of a participant's study condition. Similar to concerns with blinding of participants and other study personnel, unblinded outcome assessors may introduce detection bias, whereby their knowledge of participant study condition may influence how data were recorded, how they asked questions or engaged with the participant. Self‐reported outcomes, such as the primary and many of the secondary outcomes included in this review, were particularly vulnerable to differential reporting arising from the participant's awareness of intervention assignment. The outcomes related to harmful alcohol use included in this review were measured using self‐report instruments typically administered by data collection personnel, which were prone to differential recording based on expectations regarding the effects of participation in a given study condition. We classified studies as low risk of bias if the outcome assessor and participant were blinded to study condition. In contrast, we classified studies as high risk of bias if the outcome assessor or participant was unblinded. If this information was not included in the manuscript, we labeled risk of bias as unclear.

Incomplete outcome data included differential attrition between groups as well as proper handling of missing data. We compared the magnitude and reasons for missingness and attrition between groups. Furthermore, we considered how missing data were handled and whether the researchers conducted an intention‐to‐treat analysis, whereby all participants were analyzed as randomized. Studies with low risk of bias had non‐differential attrition between groups and must have been analyzed according to the intention‐to‐treat principle. Studies with high risk of bias had a large amount of missing data that were poorly handled, differential reasons, and magnitude of attrition between groups, or only employed a per‐protocol analysis. We labeled studies that did not clearly fall into either category as unclear risk of bias.

Reporting bias referred to consistency in the outcomes reported in the methods or study protocol (if available) and those reported in the results. If outcomes were postulated, but not reported in the results, this would be an indication of reporting bias and these studies were classified as high risk of bias. We only classified studies at low risk of bias if a protocol or prior publication was available whereby outcomes were clearly designated a priori and were reported in the included study. Otherwise, we classified studies as unclear risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Continuous data

We assessed the effect of the intervention on harmful alcohol use and other continuous secondary outcomes as differences in changes from baseline to follow‐up between groups. We transformed study‐specific effects to standardized mean differences (SMDs), which allowed us to compare continuous outcomes across studies that applied different outcome measurement tools (Faraone 2008). We also included estimates of variability and uncertainty (e.g. standard deviation (SD), confidence intervals (CIs), range). We used outcome data from the follow‐up closest to the modal post‐randomization time point reported in the included studies for the primary analysis. If we had identified substantial variation in follow‐up time, we planned to conduct analyses at multiple time points.

Dichotomous data

We anticipated that some studies might have applied clinical cutoffs to these continuous measures of harmful alcohol use, consumption, and other secondary outcomes. For dichotomous outcomes, including remission, retention, and dichotomized indicators of harmful alcohol use, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) and associated 95% confidence interval (CI).

Unit of analysis issues

We conducted all analyses at the individual level. We evaluated outcomes from cluster‐RCTs reported at the individual level accounting for clustering in the data using the generic inverse‐variance method.

Studies with more than two groups

If studies included multiple intervention or comparison groups, we first assessed whether more than two study conditions met criteria for types of interventions and comparison groups included in this review. We described all relevant study conditions in the qualitative data synthesis. Conversely, in the quantitative data synthesis, we combined relevant experimental or control conditions to create a single pair‐wise comparison for inclusion in the meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors of studies that had missing information or did not report all results on primary outcomes and important study characteristics. If we did not receive a response within two weeks, we considered the data missing. We excluded studies that were missing data on our primary outcomes from quantitative analyses, but we retained these studies in the qualitative synthesis. We conducted all analyses using intention‐to‐treat; however, we excluded studies with high attrition in a sensitivity analysis to examine the possible effect of missingness on the pooled treatment effect estimate.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We explored clinical, methodologic, and statistical heterogeneity qualitatively and then quantitatively using Cochrane's Q, tau2, and I2 statistical tests. The qualitative evaluation included a comparison of studies with regards to study setting, sampling, eligibility criteria, intervention details, and outcome definitions to identify sources of clinical heterogeneity. We assessed methodologic heterogeneity through comparisons of study procedures (e.g. recruitment, duration of follow‐up), case definition for harmful alcohol use, risk of bias, and measurement methods. We produced forest plots stratified by intervention type to visually inspect variability in the intervention effects of included studies (Sutton 2000). Cochrane's Q, tau2, and I2 statistics quantified statistical heterogeneity. Cochrane's Q tested the null hypothesis that the effect size is equivalent across studies. Statistically significant (P < 0.10) findings suggested that heterogeneity is present. The tau2 statistic described variance in the effect estimate between studies and was used to quantify the distribution of intervention effects. The I2 statistic described the proportion of variability due to statistical heterogeneity regardless of scale or number of included studies. I2 values greater than 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2003; Borenstein 2009). We did not estimate pooled intervention effects for outcomes with substantial heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

To minimize reporting biases, we searched and included both published and unpublished literature. We assessed publication bias visually by producing and examining funnel plots. We considered study characteristics that may affect symmetry of the funnel plot (e.g. differences in study quality, true heterogeneity, number of studies).

Data synthesis

We analyzed pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions separately. We further stratified by intervention type and study population to align the intervention comparisons with their appropriate clinical indications. See Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of evidence.

Qualitative data synthesis

We synthesized results of included studies in a narrative review discussing the effects of each treatment modality on harmful alcohol use. We explored differences in results between studies and discussed how they may relate to study design, study population, measurement methods, etc. We discussed patterns, notable findings, and limitations of the studies and the available literature more broadly.

Quantitative data synthesis

We performed a meta‐analysis with study‐level data using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We anticipated that the treatment effects would vary by study setting, population, and other study‐level factors, and therefore used the random‐effects model for all analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not conduct planned subgroup analyses specified in the study protocol due to the paucity and heterogeneity of study results (seeDifferences between protocol and review).

Sensitivity analysis

We did not conduct planned sensitivity analyses that were specified in the study protocol due to the paucity and heterogeneity of study results (see Differences between protocol and review).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Summary of findings tables

We produced a summary of findings table for each of the following comparisons:

any pharmacologic intervention versus placebo among participants with alcohol use disorder or dependence;

any pharmacologic intervention versus placebo in addition to psychosocial intervention among participants with alcohol use disorder;

any pharmacologic intervention versus another pharmacologic intervention among participants with alcohol use disorder;

any pharmacologic intervention versus another pharmacologic intervention in addition to psychosocial intervention among participants with alcohol use disorder;

brief psychosocial intervention versus brief advice, information, or assessment only among participants with hazardous or harmful alcohol use;

other psychosocial intervention versus usual care or wait list among participants with hazardous or harmful alcohol use.

We included the primary outcomes in the summary of findings tables: harmful alcohol use and retention.

Grading of evidence

We assessed the overall certainty of the evidence for primary and secondary outcomes using the GRADE system. The GRADE Working Group developed a system for grading the quality/certainty of evidence which takes into account issues related to internal validity and external validity, such as directness, consistency, imprecision of results, and publication bias (Schünemann 2013). The summary of findings tables present the main findings of a review in a transparent and simple tabular format. In particular, they provide key information concerning the certainty of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the summary of available data on the main outcomes.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grades of evidence:

high: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect;

moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different;

low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect;

very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Grading was decreased for the following reasons:

serious (–1) or very serious (–2) study limitation for risk of bias;

serious (–1) or very serious (–2) inconsistency between study results;

some (–1) or major (–2) uncertainty about directness (the correspondence between the population, the intervention, or the outcomes measured in the studies actually found and those under consideration in our systematic review);

serious (–1) or very serious (–2) imprecision of the pooled estimate (–1);

publication bias strongly suspected (–1).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

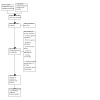

Of the 8740 records identified from searches through December 2021 we identified 309 articles that, based on their title and abstract, were included in the full‐text review. One hundred and three articles, representing 66 unique RCTs, were included in the systematic review. There was a total of 17,626 participants enrolled in the 66 included RCTs (see Characteristics of included studies). We identified six cluster‐randomized trials and the remaining 60 RCTs were individually randomized. We identified 16 ongoing studies that may meet our eligibility criteria and 12 studies (17 articles) that are awaiting classification. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies.

Setting

Of the 66 included trials, 34 were conducted in upper‐middle income countries, 27 in lower‐middle‐income countries, three in low‐income countries, and two multi‐site trial conducted in a combination of upper‐middle and lower‐middle income countries. Twelve trials were conducted in Brazil, one in Chile, one in China, 14 in India, one in Iran, four in Kenya, one in Mongolia, one in Nepal, one in Nigeria, one in Poland, three in Russia, five in South Africa, nine in Thailand, one in Turkey, one in Uganda, two in Ukraine, one in Vietnam, three in Zambia, two in Zimbabwe, and two were multi‐site trials that included study sites in Belarus, Brazil, India, Kenya, Mexico, Russia, and Zimbabwe.

Participants

Fifty‐two out of 66 trials recruited participants from health centers including general outpatient and primary care settings, emergency departments, psychiatric/substance use services, and infectious disease clinics. Other recruitment venues included police stations, universities, farms, hotlines or websites, nightclubs and other community settings. Several trials recruited specific vulnerable populations including refugees (n = 1 trial), female sex workers (n = 2 trials), people living with HIV/AIDS (n = 10 trials), and people with tuberculosis (n = 3 trials). Eighteen trials only enrolled males, while only four exclusively enrolled females. Most of the trials that exclusively enrolled females targeted high‐risk subgroups including female sex workers (n = 2 trials) or females at high risk of alcohol‐exposed pregnancy (n = 1 trial). The remaining trial recruited women seeking primary care services. Among those that recruited both males and females, the median percentage of males enrolled was 89.1%. All studies that reported age enrolled a sample with an average age over 18 years. Very few studies explicitly described ethnicity or nativity characteristics of the sample. Sample sizes ranged from 33 in Bolton 2014 to 1400 in Schaub 2021 (Median = 157.5, interquartile range (IQR) = 92.5 to 371).

Harmful alcohol use eligibility criteria varied across studies. Twenty‐five trials recruited participants who met criteria for alcohol use disorder. Thirty‐one trials used cutoffs for hazardous, harmful, or risky drinking, most commonly assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT). Other trials used specific indicators of risky drinking (e.g. extended periods of binge‐drinking, average consumption volume; n = 2 trials), seeking care in the emergency department as a result of alcohol‐related health problems or injury (n = 1 trial), self‐reported alcohol problems (n = 3 trials), partner‐reported alcohol problems (n = 2 trials), enrollment in alcohol treatment services (n = 1 trial), or calling into a support line to stop drinking (n = 2 trials) as a proxy for harmful alcohol use.

Interventions and comparators

The majority of interventions (n = 52 trials, 77.6%) were psychosocial. Brief interventions were the most common type of psychosocial intervention (n = 27 trials, 51.9% of psychosocial trials, 40.3% of all included trials), followed by other psychosocial interventions, which were sometimes delivered in combination with or in comparison to brief intervention elements (n = 25 trials, 48.1% of psychosocial trials, 37.3% of all included trials). Brief interventions ranged from one session to seven sessions and focused primarily on motivational interviewing techniques. Some brief interventions also incorporated elements of cognitive behavioral therapy, risk reduction, relapse prevention, and/or self‐help. Providers were specialist and non‐specialist health workers, including nurses, HIV counselors, general counselors, social workers, psychologists, physicians as well as lay counselors, trained university students, and telephone hotline workers. One brief intervention used a self‐help booklet to supplement the single session delivered by health providers. Comparison conditions for brief interventions included informational controls, brief advice, brief intervention for tobacco use, usual care, a list of available treatment and recovery support services, equal attention nutrition control, assessment only, or a wait‐list control.

Other psychosocial interventions included the following: a transdiagnostic psychotherapy, Common Elements Treatment Approach (CETA) that included cognitive‐behavioral therapy (CBT) and motivational interviewing components; 25‐ to 30‐day inpatient treatment programs; a contingency management program combined with counseling and/or home visits; four to 10 sessions of combined motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy; 20 group psychotherapy sessions incorporating motivational interviewing, cognitive therapy, coping skills training and relapse prevention supplemented with home visits; seven sessions of relapse prevention within an inpatient detox and treatment setting; eight to 10 sessions of family‐ or individual‐based relapse prevention; 20 sessions of rational emotive psychotherapy; six to eight sessions of CBT; two five to six sessions behavioral interventions; four sessions of alcohol counseling; and a six‐week self‐guided web‐based self‐help program. Comparison conditions for psychosocial treatment interventions included a motivational intervention, Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP)/enhanced usual care, attention‐matched control, usual care, brief motivation, risk reduction, or wellness intervention; information only, assessments only, and a wait‐list control.

Six trials compared the efficacy of various pharmacologic treatments to other active conditions or placebo on treating alcohol use disorder (9.0% of all included trials). Active pharmacologic study conditions tested acamprosate, baclofen, disulfiram, gabapentin, mirtazapine, and naltrexone. The two trials of gabapentin were placebo‐controlled as was one of the acamprosate trials. The remaining trials compared mirtazapine to amitriptyline, acamprosate to disulfiram, and a three‐arm trial comparing acamprosate, baclofen, and naltrexone. One of the pharmacologic trials encouraged participants to attend Alcoholics Anonymous and, after completion of the 12 weeks of pharmacologic treatment, transitioned participants into 12 weeks of non‐pharmacologic treatment. One of the placebo‐controlled gabapentin trials also included weekly compliance sessions.

Eight trials combined pharmacologic and psychosocial treatments for alcohol use disorder (11.9% of all included trials). The primary objective of seven of these studies was to evaluate the efficacy of a pharmacologic treatment as compared to a placebo or other active pharmacologic treatment. In these trials, the investigators combined the pharmacologic treatments under study with psychosocial interventions. The studies included the following comparisons: 12 weeks of naltrexone with counseling versus placebo with counseling; usual psychosocial care and encouragement to attend Alcoholics Anonymous along with 12 weeks of naltrexone, topiramate, or placebo; naltrexone with brief intervention or placebo with brief intervention, 12 weeks of brief CBT and encouragement to attend Alcoholics Anonymous and either ondansetron or placebo; 12 months of weekly group psychotherapy with either naltrexone or disulfiram; nine months of weekly group psychotherapy with either disulfiram or topiramate; and three to five counseling sessions along with 12 weeks of either topiramate or placebo. The final study combined six months of naltrexone with brief intervention and compared it to either naltrexone alone, brief intervention alone, or placebo.

Outcomes

Sixty‐two of the 66 included trials provided quantitative data that enabled their inclusion in the meta‐analysis. For the primary clinical outcome, harmful alcohol use, 33 trials provided data. Thirty‐five reported harmful alcohol use as a continuous outcome. The primary efficacy analysis examining continuous or dichotomous measures of harmful alcohol use included zero participants enrolled in pharmacologic trials, 5262 participants enrolled in 21 trials of brief interventions, 2106 participants enrolled in 12 trials of psychosocial treatment interventions, and 577 participants enrolled in five combined interventions. All included pharmacologic interventions aimed to reduce harmful alcohol use among individuals with alcohol use disorder, but reported different outcomes. Harmful alcohol use was most commonly measured using standardized tools, such as the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST), or the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT/AUDIT‐C), which assess hazardous or harmful alcohol use, or by measuring the different patterns of consumption (frequency, volume, and/or binge‐drinking). The modal follow‐up duration was six months, and thus we selected the outcome data nearest to six months to include in our meta‐analysis for all efficacy outcomes.

The safety outcomes included retention and adverse events. Three placebo‐controlled pharmacologic trials with 247 participants reported on completion of pharmacologic treatment. Similarly, three combined intervention trials including 363 participants reported on completion of treatment. Five pharmacologic and combined trials also reported on adverse events, which were reported as lists of frequencies or proportions of participants in each study condition that experienced adverse events. The four comparative effectiveness pharmacologic trials also reported on retention. Twelve brief psychosocial interventions reported on retention. In these brief psychosocial trials, retention was often defined as receiving the allocated intervention, which was most typically either a single brief motivational interviewing session or brief advice/information. Nine other psychosocial interventions reported retention by study condition, which was operationalized as either receiving or completing the allocated intervention. Ten trials reported on retention in the intervention in the experimental group only. In seven trials it was unclear whether retention was reported in reference to the intervention or the research follow‐up assessments and thus these results were excluded from the meta‐analysis.

Regarding secondary outcomes, 19 trials provided data on alcohol consumption, 19 trials provided data on remission, and five trials provided data on adverse events. The analysis of the efficacy of alcohol interventions on reducing alcohol consumption included 94 participants from one pharmacologic trial, 1779 participants from nine brief intervention trials, 1609 participants from seven psychosocial treatment trials, and 71 participants from one combined intervention trial. Alcohol consumption was measured using the Alcohol Consumption Risky Questionnaire, the ASSIST, the AUDIT, the Timeline Followback, the Form‐90, the Healthy Lifestyle Questionnaire, the Rapid Alcohol Problems Screen, the Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire, a breathalyzer, or self‐reported consumption. Ten trials also included biomarkers. The analysis of the efficacy of alcohol interventions on increasing remission included 534 participants from five placebo‐controlled pharmacologic trials, 371 participants from four comparative effectiveness pharmacologic trials, 2240 participants from five brief intervention trials, and 1519 participants from seven psychosocial intervention trials. Remission was most often operationalized as a defined period of abstinence and measured using the alcohol consumption measures described above as well as self‐reported consumption. Several studies, particularly brief intervention studies, also included low‐risk or non‐problematic drinking in their definition of remission.