Abstract

Infection with the nematode parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis induces a pronounced type-2 T-cell response that is associated with marked polyclonal immunoglobulin E (IgE) and IgG1 production in mice. To examine the differential roles of the infection and products produced by nematodes, we investigated a soluble extract of N. brasiliensis for the ability to mediate this type-2 response. We found that the extract induced a marked increase in IgE and IgG1 levels, similar to that induced by the infection. The extract did not affect the level of IgG2a in serum, showing that the effect was specific to IgE and IgG1 (type-2-associated immunoglobulin) rather than inducing a nonspecific increase in all immunoglobulin isotypes. This response was also associated with increased interleukin-4 production in vitro. These results confirm that the extract, like infection, is a strong inducer of polyclonal type-2 responses and a reliable model for investigating the regulation of nematode-induced responses. The extract induced the production of IgG1 when added to in vitro cultures of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated B cells. This provides evidence for the induction of class switch. It did not induce upregulation of IgG1 in naive (unstimulated) B cells or expand B cells in in vitro cultures. Analysis of DNA from the spleens of mice treated with the extract by digestion-circularization PCR demonstrated a marked increase in the occurrence of γ1 switch region gene recombination in the cells in vivo. These results provide strong evidence that soluble worm products are able to mediate the marked polyclonal γ1/ɛ response and that infection is not required to mediate this response. Furthermore, these data provide evidence that the soluble nematode extract induces this effect by causing de novo class switch of B cells and not by an expansion of IgG1 B cells or an increase in antibody production by IgG1 plasma cells.

Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection in mice has been widely used to address the mechanisms involved in the regulation of the type-2 responses associated with nematodes. One significant aspect of the type-2 shift induced by this worm in mice is the bias of the immunoglobulin (Ig) response towards IgE and IgG1 (29, 72, 75). A compelling characteristic of this response is the fact that most of this antibody is not directed against the parasite; only a small fraction is specific to nematode antigens (20, 21). This clearly indicates that nematode infection induces a polyclonal activation of reaginic antibodies. Further to this, there is strong evidence that nematode infection will bias the developing immune response to unrelated antigens towards IgE and reaginic IgG. For example, we (31) have shown dramatic effects on the developing antibody response to third-party antigens by treatment with nematodes and nematode extracts. This observation is significant in that it suggests that the influence of nematodes on immune responses is far reaching and may have profound effects on developing immune responses to unrelated antigenic challenge. This could have significant effects on the outcome of vaccination strategies in areas where nematode infection is endemic.

Currently, the prevailing evidence supports important roles for both interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 in IgE and IgG1 production, including such antibody production following nematode infection. This has been confirmed by cytokine blocking experiments (1, 2, 10, 27, 72) and gene knockout experiments (25, 26, 40, 41, 51). Several in vitro culture studies have shown that production of both IgE and IgG1 is dependent on IL-4, as the addition of antibodies to either IL-4 or the IL-4 receptor completely inhibits IgE and IgG1 production (12–14).

This cytokine dependence is likely due to the role of these cytokines in mediating class switch. For example, it has been demonstrated that the addition of IL-4 to cultures of either lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- or anti-CD40 antibody-stimulated murine B cells induces high levels of germline ɛ and γ1 transcripts that correlate with the amount of IgE and IgG1 induction, respectively (5–7, 16, 23, 37, 57). Similar observations have been reported in a number of in vivo model systems (73, 74). The production of both IgE and reaginic IgG has common regulatory elements (15, 38, 52, 59, 62); there is now convincing evidence in mice of a sequential switch from μ to γ1 and then to ɛ (38, 59, 74). Such a sequential switch has also been documented in other species (43).

It is clear that IL-4 and IL-13 are involved in reaginic antibody production in response to nematodes. What remains to be addressed, however, is the relationship between the inflammatory parameters of infection, the products produced by the nematode, and the immunoglobulin response that follows. It is unclear whether the large polyclonal γ1/ɛ response seen after nematode infection is due to infection per se or to the elaboration of factors which either directly or indirectly mediate class switch by nematodes. The evidence that cytokine-like molecules can be produced by nematodes (17, 47) is suggestive of a direct role for nematode factors in the mediation of the γ1/ɛ response. This is of significant interest since it could form the foundation for nematode-based therapeutics.

In this study, we examined the effects of a soluble Nippostrongylus protein extract on IgE and IgG1 responses in mice. We confirmed that soluble worm products are able to mediate the heightened polyclonal γ1/ɛ response and that infection is not required to mediate this response. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the soluble nematode extract induces the effect by causing de novo class switch of B cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Female nude (nu−/nu−) BALB/cBYJ mice and control littermates (nu+/nu+) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). All mice were used at 8 to 12 weeks of age. Male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats (220 to 250 g) used in the maintenance of N. brasiliensis and in the preparation of adult worm homogenate (AWH) were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis, Ind.). All animals were maintained in compliance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines, with food and water provided ad libitum.

Parasites.

Third-stage (infective) larvae of N. brasiliensis were obtained from Dean Befus (University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada). The life cycle of the worms was maintained regularly by passage in Sprague Dawley rats as previously described (30).

Nippostrongylus adult worm extract preparation.

A whole adult worm extract (AWH) was prepared essentially as previously described by Nawa and coworkers (46). Briefly, SD rats were infected by subcutaneous injection of 5,000 third-stage larvae in 0.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 100 U of penicillin and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml (PBS-PS). Rats were sacrificed 8 days later, the abdominal cavity was exposed and adult worms were recovered from the small intestine using a modified Baermann apparatus. The adult worms were washed at least 10 times with sterile PBS-PS. The last two washes were done in PBS alone. After washing, the worms were counted, transferred into a glass tube, and homogenized in 1 to 2 ml of PBS with a glass tissue homogenizer. The homogenate, in addition to 3 to 5 ml of PBS used to rinse the homogenizer, was transferred into 15-ml polypropylene tubes. To eliminate large particles, the homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and then further clarified (to eliminate fine particles) by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The homogenate was sterilized through syringe filters (0.22 μm; Millipore Corp.), aliquoted into 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes (Fisher Scientific, Nepean, Ontario, Canada), and stored at −20°C. No protease inhibitors were added at any stage of the procedure. Protein content of the extract was determined with the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce Laboratory, Rockford, Ill.) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

In vivo treatment.

For in vivo experimentation, BALB/c mice were injected subcutaneously with 200 μl (200 μg of protein) of either AWH or killed mycobacteria (Sigma-Aldrich Co., Oakville, Ontario, Canada). Control animals were either untreated (naive) or injected with either PBS or Freund's incomplete adjuvant (FIA; Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Prior to use, AWH was emulsified in FIA (ratio, 1:1). For nematode infections, mice were injected subcutaneously with 600 larvae in 200 μl of PBS. At each time point postinfection, mice in the various groups were bled through the retroorbital plexus, and the serum obtained was stored at −20°C until analyzed for immunoglobulin levels using antibody capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Some mice from each group were sacrificed; spleen cells were obtained and used for both cytokine mRNA and protein profile analyses.

Cell isolation.

Single spleen cell suspensions from either naive or treated mice were prepared in RPMI 1640 (ICN, Aurora, Ohio) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies, Burlington, Ontario, Canada), 20 mM HEPES (Life Technologies), 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 2 mM l-glutamine (Life Technologies), and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich Co.). The cell suspension was purged of red blood cells by hypotonic lysis with ammonium chloride lysing buffer. B cells were isolated from nude mouse spleen cell preparations by adherent cell depletion (1 h at 37°C). B cells were isolated from control littermates by negative selection as previously described (32). This treatment consistently yielded a B-cell purity of >95% as determined by flow cytometry. The viability of the cells was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion. Cells from these preparations and nude mouse B cells were tested for reactivity to the T-cell mitogen concanavalin A (ConA), and no residual T-cell activity was detected.

Proliferation assay.

B cells (2 × 105/well) were cultured in 96-well flat-bottomed plates (Nalge Nunc Inc., Roskilde, Denmark) in a total volume of 200 μl per well. Each well was stimulated with LPS (5 μg/ml; from Escherichia coli serotype O55.55; Sigma-Aldrich Co.) in the presence or absence of AWH at different concentrations. The cultures were incubated for 72 h at 37°C, followed by an additional 18-h pulse with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine (ICN) per ml. The cells were harvested onto glass fiber mats with a cell harvester (Skatron Instrument Inc., Sterling, Va.). Proliferation was assessed by measuring [3H]thymidine incorporation with a scintillation counter (Beckman, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). In all experiments, wells were set up in triplicate. Data are expressed as disintegrations per minute (dpm) ± standard deviation (SD) in each triplicate.

In vitro stimulation of B cells for immunoglobulin production.

Purified B cells (2 × 106/ml) were stimulated with 10 μg of LPS per ml alone or LPS in combination with AWH (20 μg/ml) or IL-4 (5 ng/ml; Genzyme, Cambridge, Mass.). The cells were incubated in 1 ml of supplemented RPMI in 24-well plates (Nalge Nunc Inc.) at 37°C. Culture supernatants were harvested 7 days later, centrifuged to eliminate cells, and stored at −20°C until analyzed for immunoglobulin levels using antibody capture ELISA.

Antibody ELISA.

The level of IgE, IgG1, and IgG2a in mouse serum and IgG1 and IgM levels in B-cell culture supernatants were determined by standard capture ELISA. Flat-bottomed 96-well maxiSorb immuno-plates (Nalge Nunc Inc.) were coated with 2 μg of the respective capture anti-immunoglobulin antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG1, goat anti-mouse IgG2a, or goat anti-mouse IgM; Cedarlane Laboratories, Hornby, Ontario, Canada) or anti-mouse IgE monoclonal antibody (Pharmingen, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) per ml overnight at 4°C. After blocking, the wells were seeded with 100 μl of either serum or B-cell culture supernatants and appropriate standards and incubated overnight at room temperature. Immunoglobulins were detected using secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Cedarlane Laboratories), a substrate solution that consisted of 0.4 μg of o-phenylenediamine substrate (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) per ml in citrate buffer (pH 5.0) and hydrogen peroxide (0.04%; Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Absorbance was read at a wavelength of 490 nm using a Titertek plate reader (ICN).

Cytokine ELISA.

Supernatants from the spleen cell cultures were analyzed for the levels of IL-4 by a sandwich ELISA as described previously (33). Briefly, flat-bottomed 96-well ELISA plates were coated with anti-mouse IL-4 (1 μg/ml; Pharmingen); in 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at 100 μl per well and incubated overnight at 4°C. After blocking, test culture supernatants and recombinant IL-4 were applied to the wells, and the plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. Following this, biotinylated anti-IL-4 antibody (Pharmingen) was added to the wells at 0.5 μg/ml and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Detection was by extravidin-peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich Co.), with the detection substrate being 3,3′5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine plus H2O2.

RT-PCR.

Total cellular RNA was isolated from spleen cells of mice injected with AWH or worms or naive (untreated) mice using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies). RNA was isolated from 107 spleen cells as previously described (30). Reverse transcription (RT) reaction of each RNA sample was performed on 1 μg of total RNA using Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). Each reaction mixture (total volume, 20 μl) contained first-strand buffer (1×), dithiothreotol (0.01 M), deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs; 0.5 mM), random hexamer primers (1 μg), M-MLV reverse transcriptase enzyme (200 U), and RNA solution (1 μg).

PCR was performed on cDNA products (3 μl) for IL-4 and IL-13 sequences in the presence of reaction mixtures made up of PCR buffer (2 M KCl, 1 M Tris [pH 8.4], 1 M MgCl2, 1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml), 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.5 μM each of the primer sets, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Life Technologies). Each reaction was adjusted to a final volume of 50 μl with distilled water. The conditions used for PCR were 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C for DNA denaturation, 1 min at 55°C for primer annealing, and 1 min at 72°C for primer extension, at the end of which the product was subjected to a final incubation period of 5 min at 72°C to ensure complete product extension. Amplification of β-actin sequences served as control transcripts for the reaction and for semiquantitative purposes. PCR products were resolved on 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Gels were photographed with a DS/34 Polaroid camera (Bio/Can) using a Foto/Prep 1 UV transilluminator (Bio/Can) or digitally captured with Micro Analyst software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). The primers used in the PCR (obtained from Life Technologies) are as follows: β-actin, 5′ primer, CTGGAGAAGAGCTATGAGC, and 3′ primer, TTCTGCATCCTGTCAGCAATG; IL-4 5′ primer, CGAAGAACACCACAGAGAGTGAGCT, and 3′ primer, GACTCATTCATGGTGCAGCTTATCG; IL-13 5′ primer, ATGGCGCTCTGGGTGACTGCAG, and 3′ primer, GAAGGGGCCGTGGCGAAACAGTTG.

DC-PCR.

For digestion-circularization-PCR (DC-PCR), genomic DNA was isolated from spleen cells of naive (untreated) mice or treated mice by standard methods as previously described (18, 64) or with DNAzol reagent as recommended by the manufacturer (Life Technologies).

Digestion of each DNA sample was performed in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes with 5 to 10 μg of DNA in a 100-μl volume using EcoRI as the restriction endonuclease. Each reaction mixture contained 10 μl of 10× React 3 buffer (1× final; Life Technologies), EcoRI (2 U/μg of DNA; Life Technologies), DNA solution, and the appropriate volume of double-distilled water required to adjust the volume to 100 μl. The reaction mixtures were then incubated overnight in a 37°C waterbath, following which the enzyme was inactivated by incubation at 70°C for 20 min. For ligation (circularization), 10 to 20 μl of digested DNA samples was placed in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes to which 20 μl of 5× T4 DNA ligase buffer (1× final; Life Technologies), 2 μl (20 U) of T4 DNA ligase (Life Technologies), and double-distilled water were added to a final volume of 100 μl. The reaction mixtures were incubated overnight in a 16°C waterbath. Ligated DNA samples were kept at −20°C until amplification by PCR.

PCR was performed on ligated DNA products for the detection of Sμ-Sγ1 recombination and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChRe) β subunit gene with appropriate primers in clean 0.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes. Portions (5 to 20 μl) from the ligation reaction were placed into PCR tubes with the reaction mixture containing 5 μl of 10× GeneAmp PCR buffer II (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 500 mM KCl), 2 μl (1.0 mM) of MgCl2, 0.2 mM each of the dNTPs, 0.5 μM each of the primer set, and 2.5 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (AmpliTaq Gold; Perkin Elmer Corp., Norwalk, Conn.). Each reaction was adjusted to a final volume of 50 μl with distilled water. Amplification of the samples for the detection of Sμ-Sγ1 rearrangement and nAChRe gene was performed in an automated thermal cycler subjected to the following cycling parameters: 94°C for 9 min to activate the enzyme, initial 5 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 65°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min; further 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, stringent annealing at 68°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min; and complete extension of PCR products at 72°C for 7 min. Amplification of the nAChRe gene served as a control for DNA preparation, restriction digestion, and ligation in the DC-PCR procedure and for semiquantitative purposes. PCR products were kept at −20°C until analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR products were resolved as stated in the section above.

The primer sequences used in the PCR (initially published by Chu et al. [6]) were purchased from Life Technologies and are as follows: nAChRe sense, 5′-AGGCGCGCACTGACACCACTAAG-3′; nAChRe antisense, 5′-GACTGCTGTGGGTTTCACCCAG-3′ (generated a 753-bp PCR product from the digested and circularized genomic DNA template); Sμ antisense, 5′-GGCCGGTCGACGGAGACCAATAATCAGAGGGAAG-3′; Sγ1 sense, 5′-GCGCCATCGATGGAGAGCAGGGTCTCCTGGGTAGG-3′ (generated a 219-bp PCR product from the digested and circularized genomic DNA template). Nucleotides in bold are linker sequences containing a SalI or ClaI site; the remaining nucleotides represent mouse genomic sequences. Primers were reconstituted upon receipt with sterile double-distilled water, aliquoted in autoclaved 500-μl microcentrifuge tubes, and stored at −20°C.

Statistics.

Statistical analyses were performed by the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparisons between multiple treatments and Student's t test for comparisons between two treatments. Comparisons with a probability value of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

N. brasiliensis extract induces IgE and IgG1 production.

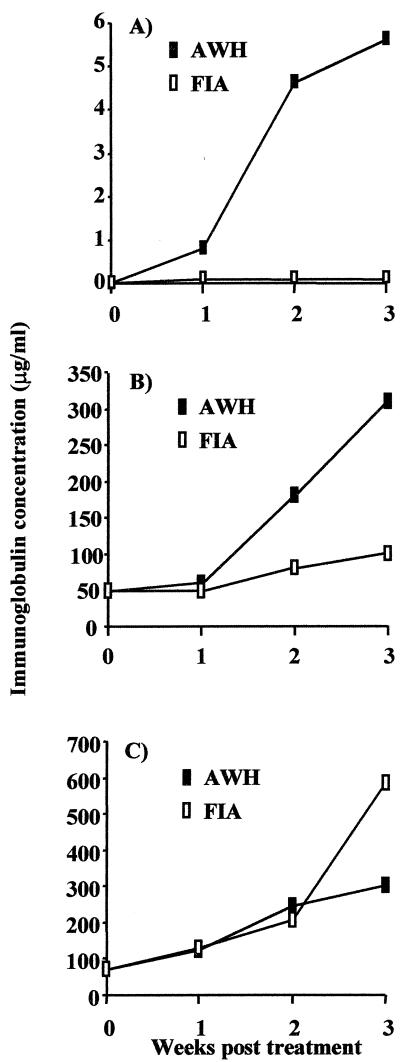

Increased production of circulating IgE and IgG1 in mice infected with nematodes has been widely reported (15, 29, 75), but the mechanism involved in this response is unclear. We adopted a reductive approach using an extract (AWH) of N. brasiliensis. We found that, like infection, injection of mice with AWH (200 μg of protein, which is equivalent to about 200 worms) resulted in a marked increase in the level of total IgE in the serum (Fig. 1A). This was about five- to sixfold higher than the control level at 3 weeks post-AWH injection. In mice injected with the vehicle alone, no increase in IgE level was detected. In fact, in these mice the baseline level at day 0 was maintained at all time points examined. In addition, a marked increase in the level of IgG1 was observed in mice injected with AWH (Fig. 1B). The pattern of the increase in IgE and IgG1 levels in the serum of mice injected with AWH is very similar to the pattern observed in mice infected with the worm (75). However, the final absolute levels were always higher in nematode-infected (IgE, 30 μg/ml; IgG1, 2 mg/ml) than in AWH-treated mice.

FIG. 1.

AWH induces IgE and IgG1 production in the serum of BALB/c mice. Female BALB/c mice in groups of three were injected subcutaneously at the back of the neck with AWH emulsified in FIA (100 to 200 μg of protein in a 200-μl volume). The control group was injected with the vehicle alone (FIA). Each group of mice was bled for serum each week for 3 weeks, and the sera within the groups were pooled. The pooled serum samples were assayed for IgE (A), IgG1 (B), and IgG2a (C) levels by capture ELISA. The data are from one experiment and are representative of three (IgE), five (IgG1), and four (IgG2a) independent experiments.

N. brasiliensis is a strong inducer of type-2-associated immune response (15, 28, 30, 33). To verify whether the induction of increased IgE and IgG1 levels by AWH is specific to these type-2 immunoglobulins, the level of IgG2a, a type-1 immunoglobulin isotype, was also examined. The level of IgG2a in the serum of the AWH-injected mice was similar to that observed in the mice that were injected with the vehicle control (Fig. 1C). These observations show that AWH induces an immune response that is biased toward type-2 immunoglobulins, similar to our observations with N. brasiliensis infection (data not shown).

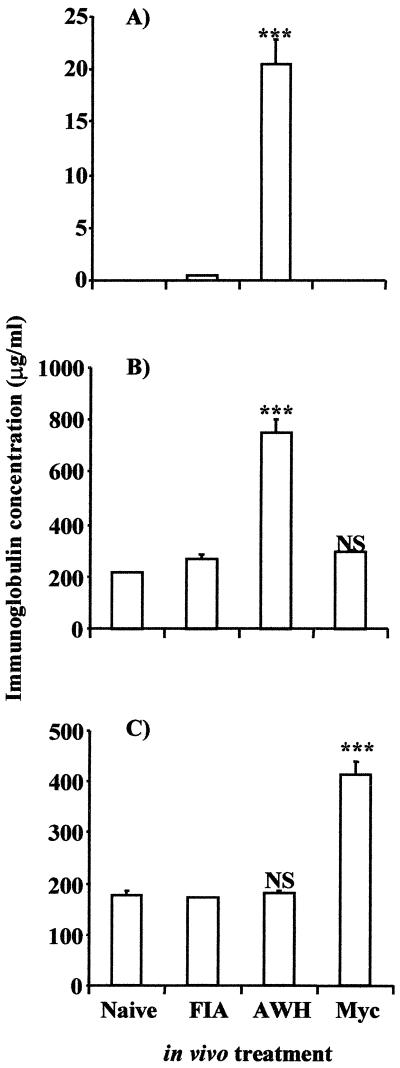

To confirm that the response induced by AWH is not simply a response to a complex antigen, the immune response induced by AWH was compared to the immune response induced in mice injected with killed mycobacteria in the same vehicle as AWH. As shown in Fig. 2A, IgE was detected in significant amounts in mice injected with AWH (reaching a level of 20 μg/ml) but was not detected in the serum of mice injected with mycobacteria. The level of IgG1 in mycobacteria-treated mice was not greater than that observed in mice injected with the vehicle control or in naive (untreated) mice (Fig. 2B). In contrast, mice injected with mycobacteria showed much higher levels of IgG2a in the serum than control animals, from 150 to about 450 μg/ml (Fig. 2C). In the same experiment, mice injected with AWH did not show increased levels of IgG2a in comparison to naive (untreated) or vehicle-injected mice (Fig. 2C). These data provide strong evidence that the Nippostrongylus extract, and not just a response to the injection of a complex antigen mixture, specifically induced the increased type-2-associated immunoglobulin response observed.

FIG. 2.

Increased IgE and IgG1 response is specific to AWH treatment. BALB/c mice in groups of three were injected with killed mycobacteria (Myc) or AWH emulsified in FIA (vehicle). The third group received vehicle alone (FIA). Mice in each group were bled for serum at 14 and 21 days posttreatment. Serum samples were pooled within each group. Serum samples were assayed for IgE, IgG1, and IgG2a levels by capture ELISA. Data shown are the IgE (A), IgG1 (B), and IgG2a (C) levels at 21 days posttreatment. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicate wells and are representative of three experiments (A) ∗∗∗, P < 0.0004, two-tailed, unpaired Student's t test; (B and C) ∗∗∗, P < 0.001; NS, not significant (P > 0.05), one-way ANOVA.

AWH induces IL-4 and IL-13 production.

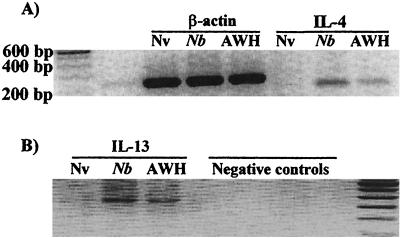

Increased IgG1 and IgE levels are associated with increased IL-4 and IL-13 production (1, 15, 41, 69). In nematode infections, the levels of mRNA and protein for these cytokines have been demonstrated to be increased in both spleen and mesenteric lymph node cells (19, 28, 39, 67, 69). If our hypothesis regarding the increase in IgE and IgG1 activity induced by AWH is correct, we would expect that the increased levels of these immunoglobulins would likewise be associated with an increase in the levels of these cytokines. To investigate this possibility, spleen cells from mice treated with AWH were analyzed for increased IL-4 production. Figure 3A demonstrates IL-4 mRNA expression in spleen cells from AWH-treated mice. A similar increase in IL-13 mRNA was also observed in the spleen cells from AWH-treated mice (Fig. 3B). In agreement with the data on levels of IgE and IgG1 in serum, the cytokine mRNA level was higher in worm-infected animals than in AWH-treated mice. Amplicons for IL-4 and IL-13 could not be detected by RT-PCR of spleen cells from naive (untreated) mice.

FIG. 3.

IL-4 and IL-13 mRNA induction by AWH. Spleen cells were isolated from mice 21 days after treatment with AWH or N. brasiliensis (Nb). For assessment of IL-4 (A) and IL-13 (B) mRNA expression, total cellular RNA was isolated with TRIzol and reverse-transcribed into single-stranded cDNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase and random hexamers as described in Materials and Methods. The resulting cDNA template was used in a PCR with primers specific for either IL-4 or IL-13. β-Actin mRNA levels were also determined by RT-PCR to control for equal RNA loading. PCR amplicons were resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel with ethidium bromide staining. Results are representative of three experiments. Nv, naive (untreated). The negative controls in panel B were no enzyme in RT reaction, no RNA in RT reaction, no cDNA in PCR, and no primers in PCR (left to right, respectively).

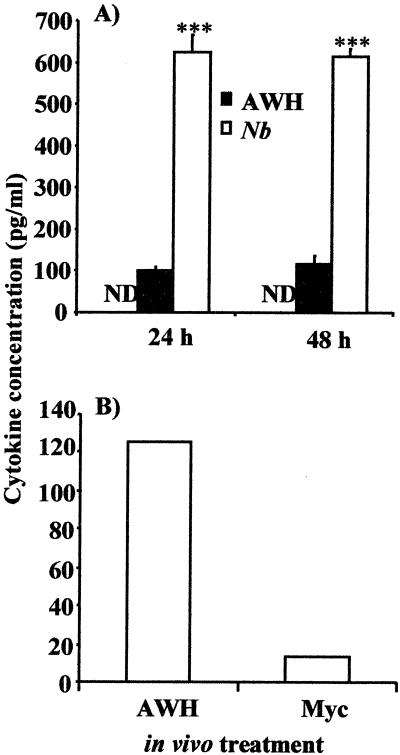

Since an increase in mRNA levels does not always reflect increased protein production, IL-4 protein levels were also assessed. Spleen cells isolated from mice 2 and 3 weeks posttreatment, were stimulated with ConA in vitro; supernatants were collected and analyzed for IL-4 levels by ELISA. IL-4 was detected in the supernatants of ConA-stimulated spleen cells from both worm- and AWH-treated mice (Fig. 4A), but not in supernatants of cells from naive control mice. The level of IL-4 was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in worm-infected (620 pg/ml) than in AWH-injected (110 pg/ml) mice. This increase in IL-4 levels is due specifically to the injection of AWH and not to a nonspecific effect of treatment with a complex antigen mixture. As shown in Fig. 4B, substantial levels of IL-4 (>120 pg/ml) were observed in the culture supernatants of ConA-stimulated spleen cells from AWH-injected mice, whereas <20 pg/ml (limit of detection) of IL-4 was present in the supernatants from mycobacterium-treated mice. When these data were normalized for the vehicle, the cytokine pattern correlated well with the observed immunoglobulin subclass levels shown in Fig. 2. These data confirm that the IL-4 induced in the spleen cells of mice treated with AWH is mediated specifically by the extract and not simply a “response to antigen” effect (i.e., that the observed responses are not simply due to the injection of a complex mixture of antigens but specifically due to factors in the extract).

FIG. 4.

Increased IL-4 response in spleen cell cultures is specific to AWH treatment. For assessment of IL-4 protein levels, spleen cells isolated from naive (untreated) mice or mice treated with AWH or worms (Nb) (A), killed mycobacteria (Myc), or AWH emulsified in FIA (B) 21 days posttreatment were stimulated with ConA (5 μg/ml) for 24 or 48 h. Culture supernatants were then analyzed by ELISA for IL-4 levels as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the mean concentration of IL-4 ± SD of three replicate wells. ∗∗∗, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA. Data in panel B were normalized for vehicle. ND, below detection limit (15 pg/ml). Results are representative of three experiments.

AWH induces IgG1 production in in vitro B-cell culture.

The observation that AWH induces an increase in IgE and IgG1 levels in mouse serum suggests an effect on B-cell activity. To examine this, we determined whether AWH could induce B cells in culture to produce IgG1.

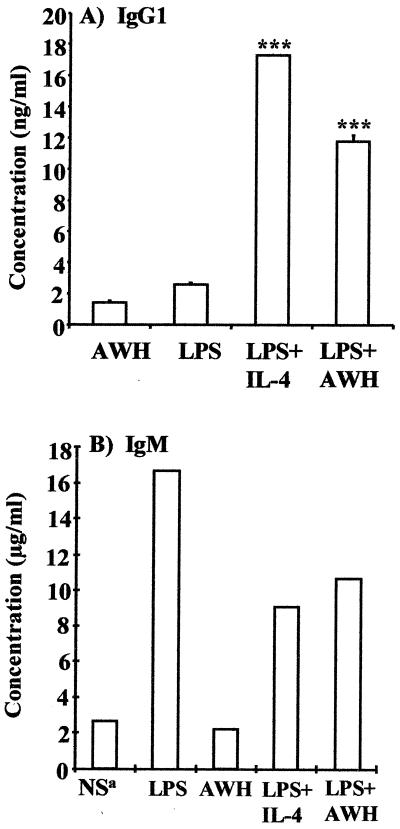

Purified B cells were stimulated with LPS and then incubated in the presence of AWH for 7 days. Supernatants from these cultures were assayed for IgG1 by capture ELISA. As a positive control, LPS-stimulated B-cell cultures were incubated with IL-4. B cells stimulated with LPS secrete significant amounts of IgM, but in the presence of IL-4, the cells undergo class switch to become IgG1- (or IgE)-secreting B cells. The data shown in Fig. 5A demonstrate that IL-4 induced an increase in IgG1 levels in the B-cell culture supernatants. In the same experiment, AWH also induced an increase in IgG1 levels in cultures of LPS-stimulated B cells. This increase was not observed in cultures of naive B cells stimulated with AWH alone, nor did LPS alone induce IgG1 production in B cells in the absence of AWH. In addition, the induction of increased IgG1 levels in the B-cell culture was associated with a decrease in the levels of IgM in the culture supernatants (Fig. 5B). These data are very suggestive that the soluble nematode extract (AWH) induces LPS-stimulated B cells to undergo class switch from μ to γ1.

FIG. 5.

Influence of AWH on immunoglobulin production in in vitro B-cell culture. Highly purified naive B cells from uninfected mice (8 to 12 weeks old) isolated as described in Materials and Methods were not stimulated (NS) or stimulated in culture containing AWH alone (20 μg/ml), LPS alone (10 μg/ml), or LPS in combination with AWH (20 μg/ml) or IL-4 (5 ng/ml). Culture supernatants were harvested 7 days later and then analyzed for IgG1 (A) and IgM (B) levels using antibody capture ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the mean concentration ± SD of three replicate wells and are representative of six separate experiments. ∗∗∗, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA.

Increased IgG1 level in AWH-treated mice associated with de novo class switch.

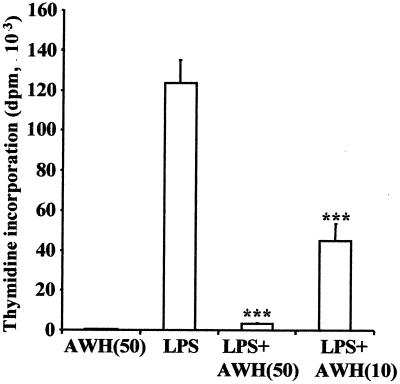

The data above suggest that the induction of increased immunoglobulin levels is mediated by class switch. However, the data could be explained by (i) an expansion of existing IgG1-committed B cells, (ii) an increase in antibody production by individual cells, or (iii) an increase in de novo class switch. To discriminate between these possibilities, we first investigated whether the increase in IgG1 levels was mediated by an expansion of existing IgG1-committed B cells in vitro in the presence of AWH. B cells from control (naive) mice were stimulated with LPS and cultured in the presence of AWH. An expansion of an existing IgG1-committed population would yield a significant increase in proliferation. Since higher levels of IgG1 are found both in vivo and under these in vitro conditions, this experiment appropriately addresses the issue of expansion of memory cells. As expected, LPS itself induced significant proliferation, but this proliferative response was significantly inhibited (P < 0.001) when the cells were cultured in the presence of AWH (Fig. 6). Furthermore, AWH alone did not demonstrate stimulatory activity when added to B cells. This inability of AWH to either stimulate naive B-cell proliferation or enhance LPS-induced B-cell proliferation effectively rules out the possibility of expansion of B cells as a mechanism of action of AWH. AWH also inhibited the proliferation of B cells obtained from mice infected with N. brasiliensis. Since infection of mice with this nematode has been shown to cause significant expansion of IgG1+ B cells in the spleen (22, 70, 71), the B-cell population tested would have increased IgG1+ B cells present compared to the control. The fact that this population did not proliferate in response to AWH confirms that AWH does not cause selective expansion of IgG1+ B cells.

FIG. 6.

AWH does not expand B cells. B cells from BALB/c mice were stimulated in culture containing LPS alone (5 μg/ml) or LPS in combination with AWH (10 or 50 μg/ml). After 72 h of incubation at 37°C, the cultures were pulsed with [3H]thymidine, and the cells were assayed for incorporation 18 h later. Data shown are expressed as mean disintegrations per minute (dpm) of triplicate wells ± SD and are representative of seven experiments. ∗∗∗, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA.

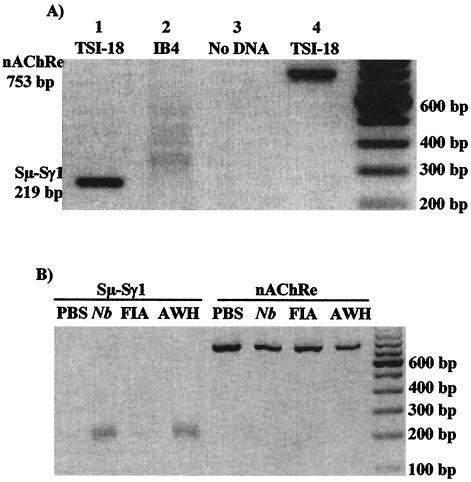

To distinguish between upregulation of antibody secretion by switched cells and an increase in class switch (de novo class switch), we adopted the molecular approach, DC-PCR, which allows the semiquantitative assessment of switched DNA (6). The specificity of this technique for IgG1 class switch has been demonstrated in a number of previous studies (45, 52, 58, 76) and was confirmed in this study by assessing genomic DNA from an IgG1-producing hybridoma (TSI-18; positive control) and an IgG2a-producing hybridoma (IB4; negative control) for the presence of γ1 rearrangement (hybridomas were a generous gift from A. Issekutz, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada). The TSI-18 hybridoma is homogenous for switched γ1. In contrast, the IB4 hybridoma does not have γ1 rearrangement but has undergone γ2a rearrangement. Using previously published primers (6, 7) the presence of the characteristic 219-bp switched γ1 DNA amplicon was amplified by DC-PCR from TSI-18 DNA. This amplicon was not present after DC-PCR of IB4 DNA (Fig. 7A). This observation confirms the specificity with which DC-PCR can assess switch DNA recombination, allowing the discrimination of the two remaining possible mechanisms of action of AWH (increased type-2 antibody secretion from individual cells versus increased de novo class switch).

FIG. 7.

AWH-induced IgG1 production is associated with an increase in the number of IgG1-switched cells. Genomic DNA was isolated from either the TSI-18 and IB4 hybridomas (A) or the spleen cells of mice treated with either AWH, worms (Nb), or FIA (B) as described in Materials and Methods. The DNA was digested with EcoRI, ligated with T4 DNA ligase, and amplified by PCR using primers specific for the recombined switch regions. nAChRe levels in all samples were also determined by DC-PCR to control for equal template loading and allow semiquantitation (comparison) of the Sμ-Sγ1 product. PCR amplicons were resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel with ethidium bromide staining. Results are representative of six experiments. (A) Lane 1, TSI-18 (IgG1-producing hybridoma); lane 2, IB4 (IgG2a-producing hybridoma); lane 3, no DNA (control for PCR contamination); lane 4, TSI-18 (nAChRe amplicon from IgG1-producing hybridoma).

To assess class switch after AWH treatment, genomic DNA was isolated from the spleen cells of mice injected with AWH or infected with worms. Control mice were injected with the vehicle alone. Amplicons indicative of γ1 switch (219 bp) were found after DC-PCR was performed on DNA from spleen cells from either AWH-treated or worm-infected animals (Fig. 7B). This indicates significant γ1 switch in the spleens of these animals. As expected, γ1 switch could also be seen, but to a lesser extent, after DC-PCR on DNA from control mice. The presence of an amplicon in these mice was not unexpected, since normal mice constitutively produce IgG1 in response to environmental challenge. nAChRe levels were also determined by DC-PCR to control for equal template loading and allow semiquantitation of the Sμ-Sγ1 products. These data provide strong evidence that the increase in total IgG1 levels observed in the serum of mice infected with worms or injected with AWH is associated with increased γ1 gene recombination, resulting in increased switched γ1-specific B cells.

DISCUSSION

Infection of mammals with parasitic nematodes induces elevated levels of reaginic antibody. In humans, these are IgE and IgG4. In mice, they are IgE and IgG1. Of significant interest is that much of this reaginic antibody is not specific to worm antigens. For example, it has been estimated that less than 20% of the IgE induced in the serum of N. brasiliensis-infected animals is specific to worm antigen (20, 21). This increase in immunoglobulin level demonstrates that N. brasiliensis has the ability to modulate B-cell activities in vivo. However, the mechanisms involved in the development of this unique polyclonal IgG1 and IgE response to nematode infection are unclear. We have used a reductive approach involving the use of a nematode extract to address this question. This approach provides the opportunity to assess the modulatory effect of the worms in both in vivo and in vitro systems. The results presented here show that injection of mice with the whole-worm homogenate, AWH, induced very dramatic increases in the levels of total IgE and IgG1 in the serum. Previous attempts to induce IgE responses by the injection of rodents with extracts of adult N. brasiliensis worms have been unsuccessful (24, 47). The difference in the outcome of these experiments and the observation reported in our study could be attributed to the difference in the preparation of the extracts and/or the concentration of the extracts injected into the rodents and the mode of administration. Furthermore, unlike our study, earlier extracts were administered in PBS, which would be rapidly absorbed. In our study the extract was released slowly from the injected vehicle. Soluble extracts of Brugia (49, 50), Toxocara (8), and Ascaris (31, 65) organisms are known to induce type-2 modulation. Uchikawa and coworkers (68) have reported IgE induction in rats using excretory/secretory (ES) products of N. brasiliensis, but in our view, the results of experimentation with ES products must always be viewed carefully because of the significant potential for contamination during what is effectively a nonsterile culture procedure to obtain the ES. The data reported here are the first evidence that a fresh, sterile extract of N. brasiliensis induces dramatic IgE and IgG1 production in vivo under controlled conditions. This provides the basis for experimentation into the mechanisms by which this response is mediated.

The fact that AWH induces marked increases in total (polyclonal) IgE and IgG1 levels but does not affect the level of IgG2a confirms that the effect of AWH is restricted to these type-2-associated immunoglobulins. In addition, the response induced by AWH is not merely a response to the injection of a complex antigen. Mice injected with killed mycobacteria produced IgG2a but not IgE or IgG1. These data provide evidence that the complex parameters of infection are not required for the reaginic response to the worm and strongly suggest the presence of a nematode factor(s) which mediates this response. However, these data do not elucidate the mechanisms behind this important response.

It is well established that the production of IgE and IgG1 immunoglobulin isotypes in both in vivo and in vitro systems requires the presence of the cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 (2, 3, 25, 27, 40, 41, 45, 51, 72). These cytokines are clearly associated with increases in the level of these immunoglobulins in the serum of mice infected with nematodes (15, 39, 51). A number of investigators have demonstrated mRNA and protein for these type-2 cytokines from spleen and mesenteric lymph node cells of mice infected with different nematode parasites (28, 39, 67, 69). Their importance has been conclusively demonstrated in studies with IL-4 and IL-13 single and double knockout mice (2, 3, 25, 41, 51, 72). A remaining question, however, has been the manner in which the nematode infection activates these cytokines. The multiple parameters associated with infection make it difficult to address this question. In our study, the presence of IL-4 and IL-13 was adequately demonstrated in spleen cells isolated from mice treated with the soluble protein extract (AWH). The pattern of the production of these cytokines correlated well with the immunoglobulin production pattern in the different treatment groups. Furthermore, the increase in both mRNA and protein indicates that AWH, like live worms, stimulates both transcription and translation of the cytokines. The detection of IL-13 mRNA in the spleen cell cultures from mice injected with AWH was of significant interest. It demonstrates the full spectrum of type-2 cytokines that regulate IgE and IgG1 production. This observation is of importance in light of the increasing evidence detailing the significant role of IL-13 in the regulation of type-2-associated immunoglobulin responses (2, 40, 41, 51, 72). It is important to note that, as observed with the immunoglobulin response, the increase in IL-4 production by spleen cells did not occur in response to injection of mice with killed mycobacteria, a control complex antigenic mixture, confirming the specificity of the response. Although the role of IL-4 in the regulation of IgE and IgG1 production is well established, there is some evidence to support the presence of regulatory mechanisms independent of IL-4 for type-2-associated immune responses (11, 44). This observation suggests that nematodes (or nematode factors) could modify host immune responses directly, to promote their survival.

An extract of the intestinal nematode parasite Heligmosomoides polygyrus has recently been reported to stimulate the production of IgG1 in naive spleen cell culture in vitro (56). The data in that study showed that the extract mediated its effect by stimulating T cells to produce a factor (presumably IL-4) that induced IgG1 production in the culture. Our data showing the induction of IgG1 in cultures of LPS-stimulated B cells by AWH, however, suggest a more direct effect of AWH on B-cell differentiation that is T-cell independent. The purity of the B cells used in the in vitro cultures in this study was greater than 95%, as shown by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis, and similar results were observed when B cells from T-cell-deficient mice were used in the in vitro cultures. No residual T-cell activity was detected in these B-cell cultures (assessed with ConA). Although the level of IgE was not assessed in these B-cell-activated cultures, the level of the alternate reaginic antibody, IgG1, is a sufficient marker of activation of the reaginic response, especially since class switch to ɛ in mice is preceded by a γ1 switch (38).

The in vitro activity of AWH reported here suggests strongly that AWH contains a switch factor or that it mediates the production of a switch factor by the B cells themselves (or by the small number of accessory cells present to ensure adequate LPS stimulation of B cells). This activity of AWH does not appear to be IL-4 mediated because IL-4 was not present in the culture supernatant of LPS- and AWH-activated B cells when analyzed by ELISA (detection limit, 15 pg/ml; data not shown). Nonetheless, evidence exists that some nematodes contain cytokine-like molecules (17, 36, 48, 53). For example, a gamma interferon homologue has been reported in the intestinal nematode parasite Trichuris muris (17). Similarly, Pastrana and coworkers have also reported the secretion of a homologue of human macrophage migration inhibitory factor by the filarial nematode parasites Brugia malayi, Wuchereria bancrofti, and Onchocerca volvolus (48). These findings demonstrate that nematodes have the capacity to produce cytokine-like factors. These cytokine homologues may have the potential to modify host immune responses to promote parasite survival.

This observation that AWH may induce class switch in vitro suggests a possible mechanism for the in vivo observations made in this study. However, there are alternate mechanisms by which AWH could exert its effect to increase the levels of IgE and IgG1 in vivo. The increase in immunoglobulin levels in vivo could be as a result of (i) an expansion of IgG1 B cells or (ii) an increase in antibody production by IgG1 plasma cells.

Robinson and coworkers (54, 55) and Lee and Xie (32) demonstrated B- and T-cell mitogenic activity in nematode extracts, suggesting a capability of inducing an expansion of IgG1 B cells (the first alternative above). However, this possibility is not supported by the data presented in the study reported here. Data obtained from the in vitro proliferation assay showed that AWH does not expand B cells from naive, AWH, or worm-treated mice. In fact, AWH induced a significant inhibition of B-cell proliferation. This observation rules out expansion of existing IgG1 B cells as the mechanism by which AWH induced the production of IgG1. The observations that AWH has the ability to induce IgG1 production in LPS-stimulated B cells and is also able to inhibit the B-cell proliferative response appear contradictory. These observations are even more interesting since it has been suggested that DNA synthesis is necessary for isotype switching (42, 61, 63). However, other reports suggest that immunoglobulin class switch is not directly linked to cell proliferation (9, 34, 35, 60). This was most clearly proven in the report by Snapper and coworkers (60), which demonstrated that B cells lacking RelB, which exhibit fourfold less proliferation, undergo normal levels of immunoglobulin class switching. At this point it is reasonable to assume, from available evidence, that certain factors involved in class switch require proliferation, while others do not.

A more convincing hypothesis is that the increase in IgG1 in response to AWH treatment is the result of an increase in the percentage of B cells exhibiting class switch to IgG1, i.e., an increase in de novo class switch of naive B cells. Based on the increased production of IgG1 in LPS-stimulated B cells exposed to AWH observed in our in vitro study and the fact that it did not stimulate IgG1 production when added alone, a hypothesis that immunoglobulin class switch is the main mechanism by which AWH mediates the marked increase in total IgG1 levels in vivo is more tenable.

To evaluate whether the increase in total IgG1 by AWH in vivo was, in fact, due to wholesale class switch, we adopted the DC-PCR technique, first described by Chu and colleagues (6, 7). This technique is specifically designed to examine immunoglobulin class switch, and its sensitivity and reliability in assessing the extent of immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene recombination events have been well reported (37, 45, 52, 58, 76). With this technique, it is important to note that only DNA segments in which switch recombination has occurred will generate PCR products. In the absence of switch, the switch regions, which are several kilobases apart, exist on different fragments. These fragments lack the appropriate sequences to which the primer anneals during amplification.

Using this system, we were able to amplify γ1-switched DNA (Sμ-Sγ1; 219 bp) at significant levels from DNA preparations of spleen cells from both worm- and AWH-treated mice at 3 weeks posttreatment. A control positive signal for the IgG1 class switch was provided by the use of DNA from an IgG1-producing hybridoma (TSI-18). This signal also served as a basis for comparison of the level of immunoglobulin class switch detected in the different treatment groups in this study. Because of the fact that both IgG1 and IgE are upregulated by N. brasiliensis infection and other Th2-activating treatments (4, 13, 29, 66) and the evidence of sequential switch from μ to γ1 and then to ɛ (38, 43, 66, 74), we concentrated on IgG1 as a marker for induction of immunoglobulin class switch by this nematode. Marked levels of γ1 switch recombination were seen in both the worm- and AWH-treated mice. Only a very low background Sμ-Sγ1 switch was detected in control animals.

This study provides strong evidence that the induction of increased IgG1 and IgE levels in worm-infected and AWH-treated mice is primarily due to stimulation of de novo class switch to these type-2-associated immunoglobulins by the nematode extract. The data are supported by the work of Yoshida and colleagues (74), who detected switch region recombination indicative of sequential μ to γ1 and then to ɛ switch in N. brasiliensis-infected animals.

We have confirmed in this study that nematode infection is not required for polyclonal reaginic antibody production; soluble nematode products also have this effect. In addition, these products do not induce this response by amplifying an existing γ1 B-cell response but by inducing a μ to γ1 class switch. These data are of significant interest because of their implications for vaccine strategies in areas where nematode infection is endemic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Novartis, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bancroft A J, Grencis R K. Th1 and Th2 cells and immunity to intestinal helminths. Chem Immunol. 1998;71:192–208. doi: 10.1159/000058711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bancroft A J, McKenzie A N J, Grencis R K. A critical role for IL-13 in resistance to intestinal nematode infection. J Immunol. 1998;160:3453–3461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barner M, Mohrs M, Brombacher F, Kopf M. Differences between IL-4Rα-deficient and IL-4-deficient mice reveal a role for IL-13 in the regulation of Th2 responses. Curr Biol. 1998;8:669–672. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70256-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck L, Spiegelberg H L. The polyclonal and antigen-specific IgE, IgG1 and IgG2a response of mice injected with ovalbumin in alum or complete freund's adjuvant. Cell Immunol. 1989;123:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(89)90263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berton M T, Uhr J W, Vitetta E S. Synthesis of germ-line γ1 immunoglobulin heavy-chain transcripts in resting B cells: induction by interleukin 4 and inhibition by interferon γ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2829–2833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu C C, Paul W E, Max E E. Quantitation of immunoglobulin μ-γ1 heavy chain switch region recombination by a digestion-circularization polymerase chain reaction method. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6978–6982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu C C, Max E E, Paul W E. DNA rearrangement can account for in vitro switching to IgG1. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1381–1390. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Prete G F, De Carli M, Mastromauro C, Biagiotti R, Macchia D, Falagiani P, Ricci M, Romagnani S. Purified protein derivative of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and excretory-secretory antigen(s) of Toxocara canis expand in vitro human T cells with stable and opposite (type 1 T helper or type 2 T helper) profile of cytokine production. J Clin Investig. 1991;88:346–350. doi: 10.1172/JCI115300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dillehay D L, Jiang X L, Lamon E W. Differential effects of retinoids on pokeweed mitogen induced B cell proliferation versus immunoglobulin synthesis. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1991;13:1043–1048. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(91)90060-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emson C L, Bell S E, Jones A, McKenzie A N J. Interleukin (IL)-4-independent induction of immunoglobulin (Ig)E, and perturbation of T cell development in transgenic mice expressing IL-13. J Exp Med. 1998;188:399–404. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferlin W G, Severinson E, Ström L, Heath A W, Coffman R L, Ferrick D A, Howard M C. CD40 signaling induces interleukin-4-independent IgE switching in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2911–2915. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkelman F D, Katona I M, Urban J F, Jr, Snapper C M, Ohara J, Paul W E. Suppression of in vivo polyclonal IgE responses by monoclonal antibody to the lymphokine B cell stimulatory factor-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9675–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkelman F D, Katona I M, Urban J F, Jr, Holmes J, Ohara J, Tung A S, Sample JvG, Paul W E. IL-4 is required to generate and sustain in vivo IgE responses. J Immunol. 1988;141:2335–2341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkelman F D, Urban J F, Jr, Beckman M P, Schooley K A, Holmes J, Katona I M. Regulation of murine in vivo IgG and IgE responses by a monoclonal anti-IL-4 receptor antibody. Int Immunol. 1991;3:599–607. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finkelman F D, Shea-Donohue T, Goldhill J, Sullivan C A, Morris S C, Madden K B, Gause W C, Urban J F., Jr Cytokine regulation of host defence against parasitic gastrointestinal nematodes: lessons from studies with rodent models. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:505–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujieda S, Zhang K, Saxon A. IL-4 plus CD40 monoclonal antibody induces human B cells γ subclass-specific isotype switch: switching to γ1, γ3, and γ4, but not γ2. J Immunol. 1995;155:2318–2328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grencis R K, Entwistle G M. Production of an interferon-gamma homologue by an intestinal nematode: functionally significant or interesting artefact? Parasitology. 1997;115:S101–S106. doi: 10.1017/s0031182097002114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross-Bellard M, Oudet P, Chambon P. Isolation of high-molecular-weight DNA from mammalian cells. Eur J Biochem. 1973;36:32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb02881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikawa N, Goyal P K, Mahida R, Li K-F, Wakelin D. Early cytokine responses during intestinal parasitic infections. Immunology. 1998;93:257–263. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarrett E E E, Haig D M, Bazin H. Time course studies on rat IgE production in N. brasiliensis infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1976;24:346–351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarrett E E E, Miller H R P. Production and activities of IgE in helminth infection. Prog Allergy. 1982;31:178–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katona I M, Urban J F, Scher I, Kanellopoulos-Langevin C, Finkelman F D. Induction of an IgE response by Nippostrongylus brasiliensis: characterization of lymphoid cells with intracytoplasmic or surface IgE. J Immunol. 1983;130:350–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kepron M R, Chen Y-W, Uhr J W, Vitetta E S. IL-4 induces the specific rearrangement of γ1 genes on the expressed and unexpressed chromosomes of lipopolysaccharide-activated normal murine B cells. J Immunol. 1989;143:334–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kojima S, Ovary Z. Effect of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection on anti-hapten IgE antibody response in the mouse. I. Induction of carrier specific helper cells. Cell Immunol. 1975;15:274–286. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(75)90006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kopf M, Le Gros G, Bachmann M, Lamers M C, Bluethmann H, Köhler G. Disruption of the murine IL-4 gene blocks Th2 cytokine responses. Nature. 1993;362:245–248. doi: 10.1038/362245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhn R, Rajewsky K, Muller W. Generation and analysis of interleukin-4 deficient mice. Science. 1991;254:707–710. doi: 10.1126/science.1948049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai Y H, Mosmann T R. Mouse IL-13 enhances antibody production in vivo and acts directly on B cells in vitro to increase survival and hence antibody production. J Immunol. 1999;162:78–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawrence R A, Gray C A, Osborne J, Maizels R M. Nippostrongylus brasiliensis: cytokine responses and worm expulsion in normal and IL-4 deficient mice. Exp Parasitol. 1996;84:65–73. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lebrun P, Spiegelberg H L. Concomitant immunoglobulin E and immunoglobulin G1 formation in Nippostrongylus brasiliensis-infected mice. J Immunol. 1987;139:1459–1465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ledingham D L, McAlister V C, Ehigiator H N, Giacomantonio C, Theal M, Lee T D G. Prolongation of rat kidney allograft survival by nematodes. Transplantation. 1996;61:184–188. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199601270-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee T D G, McGibbon A M. Potentiation of IgE responses to third party antigens mediated by Ascaris suum soluble products. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1993;102:185–190. doi: 10.1159/000236570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee T D G, Xie C Y. Polyclonal stimulation of murine B lymphocytes by Ascaris soluble product. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;95:1246–1254. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liwski R S, Lee T D G. Nematode infection enhances survival of activated T cells by modulating accessory cell function. J Immunol. 1999;163:5005–5012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lycke N, Strober W. Cholera toxin promotes B cell isotype differentiation. J Immunol. 1989;142:3781–3787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lycke N, Severinson E, Strober W. Cholera toxin acts synergistically with IL-4 to promote IgG1 switch differentiation. J Immunol. 1990;145:3316–3324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maizels R M, Bundy D A P, Selkirk M E, Smith D F, Anderson R M. Immunological modulation and evasion by helminth parasites in human populations. Nature. 1993;365:797–805. doi: 10.1038/365797a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mandler R, Chu C C, Paul W E, Max E E, Snapper C M. Interleukin 5 induces Sμ-Sγ1 DNA rearrangement in B cells activated with dextran-anti-IgD antibodies and interleukin 4: a three-component model for Ig class switching. J Exp Med. 1993a;178:1577–1586. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandler R, Finkelman F D, Levine A D, Snapper C M. IL-4 induction of IgE class switching by lipopolysaccharide-activated murine B cells occurs predominantly through sequential switching. J Immunol. 1993b;150:407–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsuda S, Uchikawa R, Yamada M, Arizono N. Cytokine mRNA expression profiles in rats infected with the intestinal nematode Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4653–4660. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4653-4660.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKenzie G J, Emson C L, Bell S E, Anderson S, Fallon P, Zurawski G, Murray R, Grencis R, McKenzie A N J. Impaired development of Th2 cells in IL-13-deficient mice. Immunity. 1998;9:423–432. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80625-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKenzie G J, Fallon P G, Emson C L, Grencis R K, McKenzie A N J. Simultaneous disruption of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 defined individual roles in T helper cell type 2-mediated responses. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1565–1572. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.10.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller R L, Rothman P B. Molecular mechanisms controlling immunoglobulin E responses. In: Kresina T F, editor. Immune modulating agents. New York, N.Y: Mercel Dekker, Inc.; 1998. pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mills F C, Thyphronitis G, Finkelman F D, Max E E. Ig μ-ɛ isotype switch in IL-4-treated human B lymphoblastoid cells: evidence for a sequential switch. J Immunol. 1992;149:1075–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morawetz R A, Gabriele L, Rizzo L V, Noben-Trauth N, Kühn R, Rajewsky K, Müller W, Doherty T M, Finkelman F, Coffman R L, Morse H C., III Interleukin (IL)-4-independent immunoglobulin class switch to immunoglobulin (Ig)E in the mouse. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1651–1661. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakanishi K, Yoshimoto T, Chu C C, Matsumoto H, Hase K, Nagai N, Tanaka T, Miyasaka M, Paul W E, Shinka S. IL-2 inhibits IL-4-dependent IgE and IgG1 production in vitro and in vivo. Int Immunol. 1995;7:259–268. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nawa Y, Miller H R P, Hall E, Jarrett E E E. Adoptive transfer of total and parasite-specific IgE responses in rats infected with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Immunology. 1981;44:119–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Orr T S C, Riley P, Doe J E. Potentiated reagin response to egg albumin in Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infected rats. II. Time course of the reagin response. Immunology. 1971;20:185–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pastrana D V, Raghavan N, Fitzgerald P, Eisinger S W, Metz C, Bucala R, Schleimer R P, Bickel C, Scott A L. Filarial nematode parasites secrete a homologue of the human cytokine macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5955–5963. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5955-5963.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pearlman E, Hazlett F E, Jr, Boom W H, Kazura J W. Induction of murine T-helper-cell responses to the filarial nematode Brugia malayi. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1105–1112. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.3.1105-1112.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pearlman E, Heinzel F P, Hazlett F E, Jr, Kazura J W. IL-12 modulation of T helper responses to the filarial helminth, Brugia malayi. J Immunol. 1995;154:4658–4664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Punnonen J, Aversa G, Cocks B G, McKenzie A N J, Menon S, Zurawski G, De Waal Malefyt R, de Vries J E. Interleukin 13 induces interleukin 4-independent IgG4 and IgE synthesis and CD23 expression by human B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3730–3734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Purkerson J M, Isakson P C. Independent regulation of DNA recombination and immunoglobulin (Ig) secretion during isotype switching to IgG1 and IgE. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1877–1883. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.6.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riffkin M, Seow H-F, Jackson D, Brown L, Wood P. Defence against the immune barrage: helminth survival strategies. Immunol Cell Biol. 1996;74:564–574. doi: 10.1038/icb.1996.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robinson M, Gustad T R, Wei F-Y, David C S, Storey N. Adult worm homogenate of the nematode parasite Heligmosomoides polygyrus induces proliferation of naive T lymphocytes without MHC restriction. Cell Immunol. 1994;158:157–166. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robinson M, Gustad T R, Storey N, David C S. Heligmosomoides polygyrus adult worm homogenate superantigen: presentation to T cells requires MHC class I positive accessory cells. Cell Immunol. 1995;161:188–194. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robinson M, Gustad T R. In vitro stimulation of naive mouse lymphocytes by Heligmosomoides polygyrus adult worm antigens induces the production of IgG1. Parasite Immunol (Oxford) 1996;18:87–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1996.d01-52.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rothman P, Lutzker S, Cook W, Coffman R, Alt F W. Mitogen plus interleukin 4 induction of Cɛ transcript in B lymphoid cells. J Exp Med. 1988;168:2385–2389. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.6.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shparago N, Zelazowski P, Jin L, McIntyre T M, Stüber E, Peçanha L M T, Kehry M R, Mond J J, Max E E, Snapper C M. IL-10 selectively regulates murine Ig isotype switching. Int Immunol. 1996;8:781–790. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.5.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siebenkotten G, Esser C, Wabl M, Radbruch A. The murine IgG1/IgE class switch program. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1827–1834. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Snapper C M, Rosas F R, Zelazowski P, Moorman M A, Kehry M R, Bravo R, Weih F. B cells lacking RelB are defective in proliferative responses, but undergo normal B cell maturation to Ig secretion and Ig class switching. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1537–1541. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Snapper C M, Zelazowski P, Rosas F R, Kehry M R, Tian M, Baltimore D, Sha W C. B cells from p50/NF-κB knockout mice have selective defects in proliferation, differentiation, germ-line CH transcription, and Ig class switching. J Immunol. 1997;156:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spiegelberg H L. The role of interleukin-4 in IgE and IgG subclass formation. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1990;12:365–383. doi: 10.1007/BF00225324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stavnezer J. Antibody class switching. Adv Immunol. 1996;61:79–146. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60866-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Strauss W M. Preparation of genomic DNA from mammalian tissue. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons Inc.; 1994. pp. 2.2.1–2.2.3. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stromberg B E. IgE and IgG1 production by a soluble product of Ascaris suum in the guinea-pig. Immunology. 1979;38:489–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sudowe S, Rademaekers A, Kölsch E. Antigen dose-dependent predominance of either direct or sequential switch in IgE antibody responses. Immunology. 1997;91:464–472. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Svetic A, Madden K B, Zhou X D, Lu P, Katona I M, Finkelman F D, Urban J F, Jr, Gause W C. A primary intestinal helminth infection rapidly induces a gut-associated elevation of Th2-associated cytokines and IL-3. J Immunol. 1993;150:3434–3441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Uchikawa R, Yamada M, Matsuda S, Arizono N. IgE antibody responses induced by transplantation of the nematode Nippostrongylus brasiliensis in rats: a possible role of nematode excretory-secretory product in IgE production. Immunology. 1993;80:541–545. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Uchikawa R, Yamada M, Matsuda S, Kuroda A, Arizono N. IgE antibody production is associated with suppressed interferon-γ levels in mesenteric lymph nodes of rats infected with the nematode Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Immunology. 1994;82:427–432. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Urban J F, Jr, Katona I M, Dean D A, Finkelman F D. The cellular IgE response of rodents to infection with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, Trichinella spiralis and Schistosoma mansoni. Vet Parasitol. 1984;14:193–208. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(84)90091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Urban J F, Jr, Gamble H R, Katona I M. Intestinal immune responses of mammals to nematode parasites. Am Zool. 1989;29:469–478. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Urban J F, Jr, Noben-Trauth N, Donaldson D D, Madden K B, Morris S C, Collins M, Finkelman F D. IL-13, IL-4Rα, and Stat6 are required for the expulsion of the gastrointestinal nematode parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Immunity. 1998;8:255–264. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80477-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu L, Rothman P. IFN-γ represses ɛ germline transcription and subsequently down regulates switch recombination to ɛ. Int Immunol. 1994;6:515–521. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yoshida K, Matsuoka M, Usuda S, Mori A, Ishizaka K, Sakano H. Immunoglobulin switch circular DNA in the mouse infected with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis: evidence for successive class switching from μ to ɛ via γ1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7829–7833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zakroff S G H, Beck L, Platzer E G, Spiegelberg H L. The IgE and IgG subclass responses of mice to four helminth parasites. Cell Immunol. 1989;119:193–201. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(89)90235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zelazowski P, Carrasco D, Rosas F R, Moorman M A, Bravo R, Snapper C M. B cells genetically deficient in the c-Rel transactivation domain have selective defects in germline CH transcription and Ig class switching. J Immunol. 1997;159:3133–3139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]