Abstract

As of 2022, board certified behavior analysts who are certified for less than 1 year and have met the qualifications to serve in a supervisory capacity are required to meet with a consulting supervisor if they wish to supervise trainees’ fieldwork experience. These guidelines establish a different supervisory level of accountability in our field, supervision for supervisors. Recommendations that are uniquely tailored for new supervisors and address the relationship between new and consulting supervisors have not yet been published. In this article, we share recommendations and resources with new supervisors. We extend current literature by outlining steps new supervisors can take and resources they can use to prepare for a successful supervision journey with their consulting supervisor and supervisees.

Keywords: BCBA supervision, Consulting supervisor, Consultative supervision, New supervisor, Supervisory relationship

Behavior analytic supervision may have more than one definition depending on the context in which it is conducted. It is traditional for supervision in human service settings to involve the performance monitoring, evaluation, and management of employees (Reid et al., 2012). In the context of credentialing for behavior analysts, supervision is seen as a training model, where trainees engage in opportunities to apply behavior analytic knowledge with clients, receive feedback on their skill development, observe applications of clinical decision-making models, and develop a repertoire of supervisory skills (LeBlanc & Luiselli, 2016). This training model has expanded beyond behavior analytic trainees and is now being applied to newly certified behavior analysts who wish to serve in supervisory capacities (Behavior Analyst Certification Board [BACB], 2021).

As of 2022, board certified behavior analysts (BCBAs) who are certified for less than a year and wish to supervise trainees’ fieldwork, are required to have monthly contacts with a consulting supervisor (BACB, 2021). These guidelines establish a different supervisory level of accountability in our field, supervision for supervisors. Supervisors’ supervision is common in related fields such as medical training (Mourad et al., 2010), psychology (Watkins Jr., 2013), social work (Hamlin & Timberlake, 1982), and counselor training (Getz & Agnew, 1999). The recently published BACB guidelines for supervisors established a formal mechanism of supervision accountability to meet the field’s growth in recent years and the supervision capacity it requires (BACB, 2022a).

The need for high-quality and effective supervision sparked a discussion among experts in the field surrounding supervision best practices. The discussion produced a special section on supervision published in Behavior Analysis in Practice (BAP) in 2016. The section addressed topics such as a competency-based supervision model (Turner et al., 2016), ethical supervision (Sellers, Alai-Rosales, & MacDonald, 2016a), barriers to successful supervision (Sellers, Valentino, & LeBlanc, 2016b), best practice recommendations for supervision meetings (Sellers, Valentino, & LeBlanc, 2016b; Valentino et al., 2016), an apprentice model (Hartley et al., 2016), and the impact of supervision on treatment outcomes for clients with autism (Dixon et al., 2016).

Other articles expanded on supervisory research and best practices and included a tool to facilitate best practice supervision (Garza et al., 2018), a suggested model for teaching soft skills and professionalism (Andzik & Kranak, 2021), findings from surveys of BCBA's supervision practices (Hajiaghamohseni et al., 2021; Sellers et al., 2019), and discussion on the importance of developing compassionate and therapeutic relationships with caregivers (LeBlanc, Taylor, & Marchese, 2020b). Several books that have been published in recent years (e.g., LeBlanc, Sellers, & Alai, 2020a; Reid et al., 2012) also helped guide supervisors in their supervision journey.

These recent publications offer useful tools and resources for supervisors. However, the BACB’s most recent guidelines for new and consulting supervisors (BACB, 2021) created a need for specifically tailored recommendations for the consultative supervisory relationship. This need led us to reflect further on our experiences as supervisors, the practices we continually refine, and the expertise we developed over the years. Expert supervisory skills are continually molded by experiences and refined through collaborations with others in the field (LeBlanc, Sellers, & Alai, 2020a). Supervisors at different points in their professional development can provide meaningful perspectives on effective supervisory practices and learn from collaborations with other supervisors (Brodhead et al., 2018; LeBlanc, Sellers, & Alai, 2020a; Wenger & Snyder, 2000). To add to the literature on supervision and respond to the BACB’s guidelines for new and consulting supervisors, we adapted Sellers, Valentino, and LeBlanc’s (2016b) recommendations for individual supervision for aspiring behavior analysts and applied them to new supervisors, who are working with a consulting supervisor.

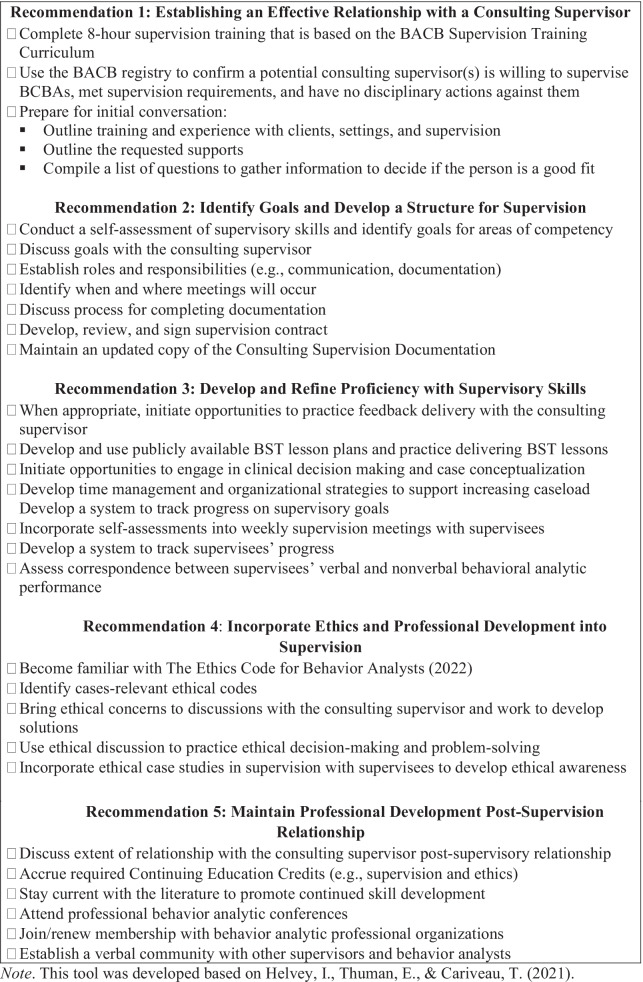

The five recommendations include (1) establish an effective relationship with a consulting supervisor; (2) identify goals and develop a structure for supervision; (3) develop and refine proficiency with supervisory skills; (4) incorporate ethics and professional development into supervision; and (5) maintain professional development postconsultative relationship. It is our hope that new supervisors find these recommendations and resources helpful to design a successful supervision journey as they take their first steps as supervisors.

Recommendation 1: Establish an Effective Relationship with a Consulting Supervisor

Although the BACB’s guidelines apply for every new supervisor, some new supervisors may not need to look for a consulting supervisor. For example, new supervisors who are employed by an organization with a structured system of hierarchical supervision may be receiving ongoing supervision by a clinical or regional director. Likewise, new supervisors who are enrolled as students in a doctoral program may be supervised by a senior PhD student or a faculty member. If the supervising supervisor meets the BACB criteria for a consulting supervisor, the supervision can be established as a formal consultation by making arrangements to meet the BACB requirement for consultation (e.g., contract, amount and structure). New supervisors who already initiated a consultative relationship can skip to recommendation 2.

New supervisors who need to find a consulting supervisor with whom to establish a consultation relationship should consider several factors. The consulting supervisor’s experience and expertise, personal and professional interactions, and supervision style are factors that can help new supervisors make a well-informed decision about selecting a consulting supervisor. Supervisors who are experienced in working with the client population with which a new supervisor is working may be better equipped to serve as consulting supervisors than those whose experience is with different populations. For example, if the new supervisor is working in early intervention for children with autism, a consulting supervisor with a rich experience in behavioral gerontology and with typically developing individuals may be less equipped to provide the necessary support and skill development consultation related to supervision in this setting.

Searching for a consulting supervisor can be pursued through the new supervisors’ current or past place of employment and training program(s), by reaching out to current or past BCBA supervisors, faculty members, and mentors. Contacting service delivery agencies in the new supervisors’ desired area of practice is a good way to target consulting supervisors who are likely experienced in that area of practice. Professional organizations in the field are another good avenue to explore. Organizations such as the Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI) provide a list of state, national, and international behavior analytic organizations and special interest groups (SIG) that can serve as an impetus for networking to establish and foster a supervisory relationship (https://www.abainternational.org/constituents/chapters/chapters-home.aspx). Finally, new supervisors can reach out to authors of relevant published works, such as research studies, book chapters, or podcasts, and inquire about the author’s capacity to provide consultation.

When a minimum of three potential consulting supervisors are identified, the BACB’s certificant registry (https://www.bacb.com/services/o.php?page=101135) should be used to verify that the potential consulting supervisors are willing to supervise BCBAs, that no disciplinary actions have been raised against them, and that they met minimum requirements (e.g., certified for more than 5 years, completed the 8-hr supervision training, and meet ongoing supervision continuing education units [CEU] requirements; BACB, 2021). Because the BACB allows remote supervision, new supervisors can contact potential consulting supervisors from anywhere in the world.

In addition to gathering information on the potential consulting supervisors’ availability and willingness to serve in this role, contacting potential consulting supervisors is an opportunity for both sides to get to know each other and evaluate how well they match personally and professionally. During the conversation, enough information should be shared to allow the potential consulting supervisor to decide if they are willing and able to provide the capacity of requested consultation. Preparing several products can help new supervisors meet these goals, one of which is a brief introduction. The introduction should include information on the new supervisors’ training, experience, previously held supervisory roles (e.g., supervising registered behavior technicians [RBTs]), the supports needed to be successful (e.g., training in feedback delivery, developing organizational repertoires), and the reasons for contacting that potential consulting supervisor, in particular (e.g., place of employment, experience with client populations).

Another useful product to prepare is a list of questions that can be posed during the initial correspondence or after the consulting supervisor has expressed interest in forming a supervisory relationship. Some particularly important questions are ones that ask about the consulting supervisor’s supervision style and expectations, their approach to delivering feedback, and willingness to schedule unplanned consultation meetings if needed. Gathering information on these areas could help to determine if the supervisor would be a good fit. A key consideration when establishing a relationship with a consulting supervisor is the amount of time they will have to devote to the supervisory relationship. Lack of time, which is commonly reported as a barrier for delivering high-quality supervision (Sellers et al., 2019), may be deleterious for a quality supervisory relationship. Thus, asking about the potential consulting supervisor’s availability, caseload, and frequency and mode of communication will ensure the potential consulting supervisor have the capacity to serve in this role (see Appendix 1 for an email template you can use to contact potential consulting supervisors).

It is important to keep in mind that although the BACB requires one monthly meeting, new supervisors may find it beneficial to meet with a consulting supervisor more frequently during the first several months or throughout the entire supervisory period. Thus, clearly communicating the supports that are being requested and making space for the consulting supervisor to share what they can commit to will help both sides to make an informed decision on whether the relationship is one that is worth forming. Approaching the conversation as an opportunity for an open and honest, bidirectional discussion and attending to the flow of the conversation and emotional responses during the conversation can also help new supervisors determine if the potential consulting supervisor is a good fit. Since successful supervisory relationships are built from a strong rapport (LeBlanc, Sellers, & Alai, 2020a; Sellers, Valentino, & LeBlanc, 2016b), these variables should also be considered as determining factors. If the conversation was flowing, expectations matched, and the consulting supervisor is available and willing to commit to the relationship, new supervisors may be ready to embark on their supervision journey. Identifying the supervisory goals and outlining the structure of the supervisory relationship with the consulting supervisor are the next steps.

Recommendation 2: Identify Goals and Develop a Structure for Supervision

The BACB indicates that the goal of a supervisory relationship with a supervisor is “to provide guidance on effective supervision practices” (BACB, 2021, p. 1). To make the most of the consulting supervisor’s guidance and support, the relationship may be best thought of as a transition period during which new supervisors cultivate the skills, expertise, and confidence to provide supervision independently within their area of competence. As trainees, behavior analysts’ priority is to develop competency with foundational skills in behavior analytic practice (Helvey et al., 2021); as new supervisors, BCBA’s priority should be to contrive opportunities for developing and refining their proficiency with supervisory skills. Even though new supervisors may be expected to have developed proficiency with foundational skills by the time they graduated and can supervise, this may not be the case. It is likely new supervisors will require, and thus should prioritize, improving their proficiency in foundational skills with which they are not yet proficient. New supervisors can improve their proficiency with both foundational and supervisory skill sets simultaneously and work toward meeting new performance goals.

Conducting self-assessment of current skills can help new supervisors functionally identify performance goals to target. Focus should be placed on identifying and targeting supervision, training, and personnel management skills. Several resources that discuss supervisory repertoires have been published in recent years, new supervisors will benefit from contacting these resources during their first year as supervisors (see Garza et al., 2018; LeBlanc, Sellers, & Alai, 2020a; Mager, 1997; Reid et al., 2012; Sellers, Valentino, & LeBlanc, 2016b; Wilder et al., 2018). Garza et al. (2018) suggested how supervisees can assess their competency with task list related skills and developed a self-assessment and competency tracking tool; new supervisors can use a similar process as they work to identify goals and further develop their supervisory repertoire. Unlike the process outlined by Garza et al. (2018), which guides supervisors on how to set goals for their supervisees, taking ownership of the self-assessment process, developing goals, and discussing the goals with the consulting supervisor will better equip new supervisors for their role. Furthermore, Garza et al. (2018) suggested broad training goals or performance criteria supervisees can use to evaluate their performance (i.e., train, generalize, monitor, or lead/train others). These goals can be adjusted and used by new supervisors to assess their fluency with naming critical variables in and creating task analyses for teaching skills, providing effective feedback for a supervisee performing skills, and teaching supervisees to train others to perform skills. After goals have been established and discussed, other areas should be addressed.

Outlining each supervisor’s roles and responsibilities and establishing expectations surrounding nonurgent and urgent communication (e.g., responding to emails within 48-hr, scheduling phone calls for ethical concerns), will promote a bidirectional and open communication, which is critical for a strong supervisory relationship (LeBlanc, Sellers, & Alai, 2020a). Solidifying when and where meetings will occur, the conditions under which additional meetings may be warranted (e.g., developing a novel skill, ethical concerns arise during supervision of supervisees), and the conditions under which the consulting supervisor may not sign off on a monthly contact (e.g., missed meetings, poor communication, inadequate documentation) will further clarify the communication on these issues as a preemptive measure. Developing a process for completing, storing, and keeping any documentation (e.g., the meeting agenda, client updates/reports, graphs) including the Consulting Supervision Documentation will ensure compliance with the BACB’s requirements.

Finally, expectations surrounding feedback delivery and reception should be established. Performance feedback is one of the most effective tools to shape performance (Alvero et al., 2001). Consulting supervisors are likely to use positive and corrective feedback to help new supervisors improve their performance of effective supervision practices. Receiving corrective feedback often evokes emotional responses (Choi et al., 2018). Keeping in mind that delivering corrective feedback may be just as aversive and acknowledging that it is the consulting supervisor’s responsibility to provide corrective feedback even though neither party enjoys it, could pave the path to effective communication surrounding feedback expectations. Clear expectations may help new supervisors develop a stronger supervisory repertoire, because they are likely to deliver and receive corrective feedback throughout their professional career. New supervisors can make the most out of this powerful tool by routinely and actively recruiting their consulting supervisor’s feedback even when feedback is corrective.

After goals have been identified, expectations have been established and agreed on, and a decision to establish a supervisory relationship was made, a consultation contract should be developed, reviewed, and signed before the consultative relationship can officially begin. If compensation for the consulting supervisor was not discussed by this point, the supervisors should communicate this prior to signing the contract. In the absence of financial compensation, communicating the reinforcers which are presumed to be in place for the consulting supervisor while referencing the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2020; hereafter referred to as the Ethics Code) will ensure an ethical and professional relationship.

Recommendation 3: Develop and Refine Proficiency with Supervisory Skills

Once BCBAs successfully complete the 8-hr supervision training, they are expected to be able to demonstrate each of the skills outlined in the Supervisor’s Training Curriculum, 2.0 (BACB, 2018). However, unlike experienced supervisors, whose focus is on developing their supervisees’ proficiency, new supervisors may need to improve their proficiency with behavior analytic skills simultaneously with strengthening supervisory repertoires. Developing proficiency with instructional delivery and training skills, progress monitoring, case conceptualization, along with time management and organizational skills may help new supervisors to fulfil their new multifaceted role in the field. The following section provides recommendations for ways these skills can be practiced in the context of the consulting supervisory relationship.

Instructional Delivery, Training, and Monitoring Skills

New supervisors will benefit from developing proficiency with two powerful supervisory training methods, behavior skills training (BST; Parsons et al., 2012) and performance feedback. BST is an evidence-based training method that has been found to be effective in training a wide variety of skills (Andzik & Kranak, 2021; Schaefer & Andzik, 2021). Proficiency with BST entails designing clear and effective lesson plans and delivering the lessons with fluency to allow for planned or scheduled as well as unplanned or opportunistic teaching opportunities. New supervisors can develop their proficiency with designing BST lesson plans by targeting skills that new supervisors can task analyze and measure easily (e.g., creating a lesson plan to teach supervisees how to use partial interval data collection method). New supervisors can develop their own BST lesson plan templates or use already created and published resources as a model (see Andzik & Kranak, 2021; Garza et al., 2018). In addition, new supervisors can develop treatment integrity (TI) checklists for the lesson plans and request the consulting supervisor to collect fidelity data on the new supervisor’s delivery of the lesson plan. Recruiting the consulting supervisor’s feedback on the lesson plans and reviewing the fidelity with which the lesson plan was implemented are mechanisms new supervisors can use to develop their proficiency with BST.

New supervisors are expected to deliver and receive feedback effectively to their supervisees (BACB, 2017, 2018). Feedback is repeatedly emphasized as a supervision best practice (LeBlanc, Sellers, & Alai, 2020a; Sellers et al., 2019), and using it effectively can significantly improve the quality and impact of supervision. Proficiency with feedback delivery and reception involves proficiency with both technical and nontechnical skills. Technical skills that are involved in effective feedback delivery may include detecting supervisees’ performance errors or providing sound behavioral rationales to explain to supervisees why and how their performance needs to change. Nontechnical skills necessary for effective feedback delivery and reception may include effective communication, empathy, and compassion (Tulgan, 2016), which are also critical for effective service delivery (Turner et al., 2016).

Delivering corrective feedback may be just as aversive as receiving it. New supervisors can develop their proficiency with delivering corrective feedback by contriving practice opportunities, which can be done in several ways. If the supervisor agrees to use feedback bidirectionally, new supervisors can use naturally occurring situations as opportunities to practice delivering corrective feedback (e.g., providing the consulting supervisor with feedback on their latency to respond to emails). Role plays can also be used to practice a variety of supervisory skills, including feedback delivery (Andzik & Kranak, 2021; Ninci et al., 2021). The consulting supervisor can play the role of a supervisee for whom the new supervisor delivers corrective feedback. During role plays, new supervisors can practice using published scripts, protocols, and tools for effective feedback delivery and reception before using them with supervisees (see Ehrlich et al., 2020; LeBlanc, Sellers, & Alai, 2020a; Sellers et al., 2019; Sellers, Valentino, & LeBlanc, 2016b; Walker & Sellers, 2021). Programming time to discuss the quality of feedback that the new supervisor delivered and addressing technical and nontechnical aspects demonstrated in the delivery and reception of feedback can increase the value of practice opportunities.

Another effective strategy new supervisors can use is record themselves delivering corrective feedback to one of their supervisees, share the recording with the consulting supervisor, and discuss the recorded performance. As an alternative, new supervisors can monitor their own performance as they watch the recording. Self-monitoring (Cooper et al., 2020) is a validated practice in the field of behavior analysis, which can be used to change and monitor behavior (see Gravina et al., 2018). Developing self-monitoring systems to track progress on supervisory goals is an essential supervisory skill. Recent findings reveal that many supervisors do not evaluate the effectiveness of their supervision (Sellers et al., 2019). To abide by ethical and professional guidelines (e.g., code 4.07; BACB, 2020), new supervisors should get in the habit of using supervision best practices and monitor their supervisory performance, which can be done by soliciting feedback from supervisees (LeBlanc, Sellers, & Alai, 2020a; Turner et al., 2016). New supervisors are invited to use a supervision self-monitoring tool we developed (see Appendix 2) to track and support their professional development as supervisors.

Supervisees’ Progress Monitoring

Just as it is important to monitor their own performance, it is important for new supervisors to monitor their supervisees’ progress. Learning how to monitor supervisees’ progress efficiently and effectively can save new supervisors time and inform them of supports that supervisees may need. Supervisees’ progress monitoring can occur in many ways including direct observation, review of permanent products, or gathering information from secondary sources (e.g., on-site supervisor, peers; Komaki, 1986). Published tools can be used to identify, select, and measure supervisees’ goals (e.g., Garza et al., 2018). Assessing the correspondence between supervisees’ verbal repertoires (e.g., defining and giving examples of differential reinforcement) and supervisees’ performance (e.g., using differential reinforcement with clients; Turner et al., 2016, LeBlanc, Sellers, & Alai, 2020a) is a component of monitoring supervisees’ progress that new supervisors should keep in mind.

Case Conceptualization

Case conceptualization can be defined as the process through which behavior analysts correctly identify the exact environmental relationship between a client’s behavior and environmental variables. Proficiency with case conceptualization will enable new supervisors to adequately answer which behavioral procedure(s) should be used to address a client’s behavior under specific environmental conditions (Meyer & Turkat, 1979; Wolpe & Turkat, 1985). Thus, developing the ability to engage in effective and functional case conceptualization is critical and should be targeted during the consultative relationship.

Effective case conceptualization requires proficiency with basic and advanced interrelated clinical skills. Proficiency with each skill can directly affect related skills and the outcome of the case conceptualization process. For clients that engage in maladaptive behaviors, case conceptualization includes functional behavioral assessment (FBA), which entails technical skills such as identifying environmental variables (e.g., motivating operations, setting events, antecedents, and consequences), measuring their impact on the behavior, and formulating, testing, and retesting hypotheses. The outcome of a case conceptualization for these clients is a uniquely tailored function-based intervention that considers therapeutic gains of alternatives such as manipulating or adjusting variables in the client’s environment, building skills, or a combination of the two (Meyer & Turkat, 1979).

In addition to technical skills, case conceptualization requires proficiency with nontechnical skills, such as problem solving and clinical decision making. Given the unique clients’ learning histories, answers to clinical problems cannot always be found in the literature. Therefore, new supervisors must use strategies to develop effective clinical decision making and functional problem-solving skills. One such strategy is “think aloud problem solving” (TAPS; Van Someren et al., 1994). New supervisors’ case conceptualization skills can be sharpened by applying the TAPS technique to real or hypothetical cases (e.g., Newman, 2007). TAPsing with the consulting supervisor topics such as implications of making different case-related decisions (e.g., employing different data collection methods, using various questionnaires for interviews), anticipating barriers for implementing interventions, and addressing challenging questions can simulate problems and decisions new supervisors will likely encounter in their practice.

In addition to developing their own proficiency with case conceptualization, supervisors are also responsible for improving supervisees case conceptualization skills. The multitude of technical and nontechnical skills necessary for effective case conceptualization, can make teaching case conceptualization an overwhelming task. Conceptualizing case conceptualization as a complex skill and using a component/composite analysis, a frequently used method in precision teaching (Chiesa & Robertson, 2000), is a systematic and structured strategy that can be applied to teach case conceptualization.

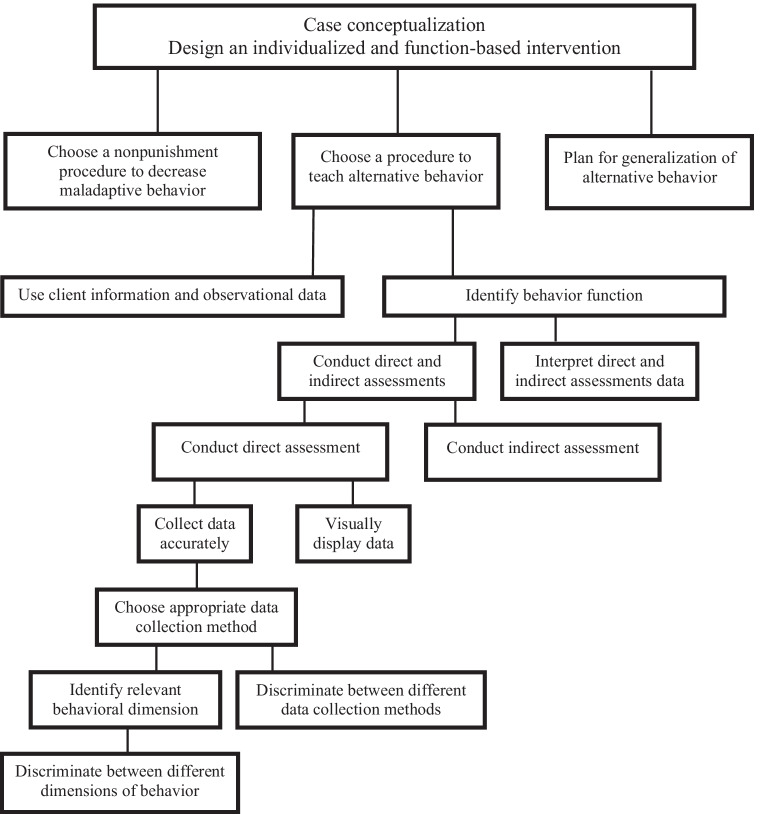

Component/composite analysis is an instructional tactic, in which skills are sequenced in a logical order from basic prerequisites (tool) skills to more complex (components) and advanced (composite) skills (Johnson & Street, 2013). Breaking down case conceptualization (composite skill) into prerequisite (component and tool) skills will allow new supervisors to pinpoint specific skills, with which supervisees need to develop proficiency. Once supervisees’ knowledge and proficiency with these skills are evaluated, skills that require additional training are identified, new supervisors can tailor targeted practice opportunities for the identified skills. It is important to note that breaking down a composite skill into component and tool skills is a function of both the analyzed composite skill and the supervisee’s proficiency. To ensure the right skills are identified, the analysis needs to be individualized. For example, accurate data collection may present a tool skill for one supervisee but for another, the same skill may present a highly complex (i.e., composite) skill that would need to be broken down further to component and tool skills. Figure 1 illustrates an example of a component/composite analysis of case conceptualization, in which one of the three component skills is further broken down into prerequisite skills.

Fig. 1.

Component/Composite analysis of case conceptualization

Time Management and Organizational Skills

New supervisors likely have developed time management and organizational systems to help them meet the demands of fieldwork experience as supervisees. As supervising BCBA’s, new supervisors will have responsibilities that consist of a wider array of activities including but not limited to, conducting assessments, developing interventions, training staff, coordinating team and client schedules (e.g., team meetings, client observations), collaborating and communicating with stakeholders, and providing supervision to supervisees. Once assigned a caseload and overseeing the activities of clients, RBTs, and BCaBAs, new supervisors may quickly find systems that used to be functional are no longer optimal. In addition to refining time management and organizational systems, related skills repertoires may need to be improved. Thus, learning how to effectively manage time and develop functional and sustainable organizational systems is another critical skill to prioritize. Effective organizational systems will help new supervisors fulfil their responsibilities on time, make adequate progress, and ensure clients’ and supervisees’ success.

There are many exceptional resources new supervisors can access to learn about effective time management and organizational repertoires (e.g., Allen, 2003; Haynes, 2015; LeBlanc, Sellers, & Alai, 2020a). Self-assessing skill competency in these areas and working with the consulting supervisor to identify current time allocation, establish priorities, and develop time management strategies are the first steps. These may include identifying the top three to four activities for which new supervisers are responsible, the amount of time currently spent engaging in these activities, and if adjustments need to be made to meet the demands of the job. For example, a BCBA may spend time overseeing client sessions (e.g., analyzing data, developing programming, conducting assessments), training and supervising supervisees, and engaging in other job related critical tasks (e.g., responding to emails, attending meetings). It is beneficial to identify what percentage of time should be spent engaging in each category of activity and considering requirements from funding sources (e.g., direct client supervision requirements, restrictions on indirect work). New supervisors may aim to spend 50% of their time engaged in client programming, 30% of their time in training and supervising supervisees, and the remaining 20% engaging in other essential job duties.

Once behaviors and goals have been identified, it is important to find time management techniques that support current responsibilities. Some techniques include identifying daily, weekly, and monthly tasks (e.g., client observations, team meetings) and upcoming deadlines (e.g., insurance reauthorization reports, credentialing requirements), planning out short- and long-term goals, unpacking larger tasks into smaller tasks, and keeping track of how well time is being allocated. Keeping a detailed time log, collecting data on time allocation, and graphing the data are good strategies to make data-based decisions while analyzing how well time is being allocated (Allen, 2003; Haynes, 2015).

Finally, developing and maintaining functional organizational systems should be an area of focus for new supervisors. New supervisors may have a brief period with a smaller caseload as they transition into a new position, but oftentimes, are expected to hold a full caseload within the first several months of employment. Supervisors in general must diligently keep track of many different aspects of their role, including assessments, programming, and client progress, in addition to monitoring supervisees’ performance, trainings, and various modes and content of communication. This may feel overwhelming and could impact service delivery and supervision quality of new supervisors. Taking the time to develop effective organizational strategies from credible experts (e.g., Allen, 2003) will ensure calendars and to-do list are used functionally, emails remain organized, tasks are prioritized effectively, and time is allocated functionally across responsibilities. Spending time developing strategies early on while a caseload is still small may prove to be a highly effective antecedent intervention for new supervisors to engage in successful management of a larger caseload and more responsibilities.

Recommendation 4: Incorporate Ethics and Professional Development into Supervision

Ethical and professional development remains a hallmark of exceptional behavior analysts. To facilitate ethical behavior, the BACB provides a wealth of resources related to ethics, including ethical toolkits, ethics related newsletters, ethics related episodes of Inside the BACB podcast, an ethics hotline, and a list of ethics related journal articles and books. Reviewing these resources will help new supervisors familiarize themselves with contemporary ethical issues in the field. In addition, the BACB published ethics violations in a 2018 newsletter which identified improper or inadequate supervision or delegation among the top ethical violations (BACB, 2019), from which new supervisors can learn. There is a clear need early on in a new supervisor’s career to develop ethical supervisory repertoires while carefully balancing the additional ethical responsibilities of a practicing behavior analyst. New supervisors are provided with a unique opportunity to develop and refine ethical practices related to professional and supervisory skills under the supervision of a consulting supervisor. However, unlike supervisees, as BCBAs, new supervisors are fully responsible for their actions, even while under the supervision of a consulting supervisor, who are not liable for the work and supervision of the new supervisors (BACB, 2021).

As previously mentioned, improper or inadequate supervision or delegation is a common ethical violation (BACB, 2019); however, new supervisors may mitigate potentially unethical situations by learning from the experience and expertise of the consulting supervisor. New supervisors will likely encounter new and unique ethical dilemmas at different points during their practice. Ethical concerns may involve clients, stakeholders, supervisees, trainees, and colleagues. Thus, maintaining privacy and protecting confidentiality is required when discussing professional, including ethical, issues always regardless of the individuals who may be involved. New supervisors can increase their awareness to ethical issues by familiarizing themselves with the BCBA and BCaBA handbooks and reviewing the Ethics Code. Routinely contacting ethical content may also inform whether training in ethical problem solving and decision making is needed.

Discussing real-life ethical dilemmas or concerns with the consulting supervisor (while maintaining confidentiality) can provide new supervisors with an opportunity to practice ethical decision making. Practice opportunities for ethical problem solving and decision making can also be contrived by role-playing situations that may raise ethical concerns, identifying relevant ethical codes, and going through the process of solving a hypothetical ethical concern. Resources other than the Ethics Code can and should be used during contrived practice opportunities. In addition to resources provided by the BACB, several resources are available and can be incorporated in activities with the goal of developing ethical repertoires (e.g., Bailey & Burch, 2016; Britton et al., 2021; Brodhead et al., 2018; Contreras et al., 2021; Sush & Najdowski, 2019). Frequently contacting ethical resources, having ethical discussions, and contriving practice opportunities can equip new supervisors with skills necessary to navigate ethical dilemmas when encountered or prevent them from happening altogether.

Recommendation 5: Maintain Professional Development Postsupervision Relationship

Although the BACB’s recently published requirements only apply to supervisors in their first year postcertification, continuing to look for learning opportunities will foster new supervisors’ acquisition, maintenance, and generalization of the newly acquired supervisory practices. This is particularly important given that many individuals who provide supervision will do so across time and will often be faced with novel supervision needs (e.g., diverse supervisees, performance management concerns, fieldwork settings) for which they may have not received specific training. Recommendations for navigating the transition from consulting supervision requirements involve steps to maintaining competence in behavior analytic supervision, establishing a supervision focused verbal community, and finding resources for practicing supervisors to inform ongoing decision making. New supervisors are invited to use a checklist we compiled that includes tasks to complete before and at various points throughout the supervisory relationship and correspond with the provided recommendations (see Appendix 3).

Maintaining Competence

New supervisors are ethically obligated to maintain professional competence (Code 1.06 in the Ethics Code). One required avenue for maintaining competence is accruing continuing education units (CEU). Ongoing continuing education requirements for practicing BCBAs and BCaBAs were established to ensure certificants are knowledgeable about changes in the field and further their repertoire beyond the minimum requirements of achieving their certification (BACB, n.d., p. 2). To meet CEU requirements, behavior analysts can engage in several learning, teaching, and scholarly activities (for a breakdown of CEU types, see BCBA, n.d., p. 38). At present, supervisors of RBTs, BCaBAs, or trainees accruing fieldwork experience, must accrue a minimum of three supervision CEUs per 2-year recertification cycle (BACB, 2022b). A variety of resources are available to earn CEUs, including professional conferences, webinars, online videos, tutorials, and article activities. The consulting supervisor is also a knowledgeable resource, as they too must engage in ongoing professional development and education to maintain their certification as a behavior analyst and as a supervisor.

Stay Current with the Literature

Obtaining the required supervision CEUs alone, though important, may not be sufficient to promote the long-term use of effective supervisory practices and skill development. New supervisors can supplement the minimum supervision CEU requirements by contacting supervision related research literature and books, which is a recommended professional development activity. Establishing systems for staying updated with the current literature can take the form of dedicating specific time each week for reading recently published articles, and joining or organizing a supervision-focused book club to contact literature on best-practice behavior-analytic supervision. Studies that may be particularly helpful to new supervisors are those that include valuable checklists or tools for enhancing supervision practices (e.g., Ditzian et al., 2018; Garza et al., 2018; Helvey et al., 2021).

Establish a Verbal Community

Participating in professional conferences and joining professional organizations is another way new supervisors can stay current with the literature. New supervisors can locate information in conference offerings provided by different organizations. For example, conference offerings by the ABAI include the annual, international, and autism conferences (https://www.abainternational.org/search.aspx). One of the greatest benefits of these events are opportunities to network with other behavior analysts as part of a larger verbal community. Establishing an environment that promotes the acquisition and maintenance of effective supervisory practices is critical for ongoing professional development. One paramount way to accomplish this is to interact with behavior analytic verbal communities. Verbal communities are “a community of speakers and listeners (as well as writers and readers, etc.) who mutually influence one another. . .” (Burton & Kagan, 1994, p. 94). Connecting with a verbal community focused on behavior analytic practice and supervision (e.g., colleagues from the new supervisors’ graduate training) can function as a resource of information and social-professional support for new supervisors.

There are several ways new supervisors can establish a verbal community. First, supervisors in the field are encouraged to maintain their relationships with their supervisees (or consultees) beyond the formal end of the supervisory relationship (LeBlanc, Sellers, & Alai, 2020a; Sellers, Alai-Rosales, & MacDonald, 2016a). Therefore, consulting supervisors may serve as a verbal community and continue to help and guide ethical and professional decisions even after the consultative relationship ends. Another avenue to build a verbal community is joining special interest groups (SIG) and registering to listservs or other online discussion forums on professional topics. ABAI has a SIG on supervision that promotes evidence-based supervision practices for members (https://www.abainternational.org/constituents/special-interests/special-interest-groups.aspx). Two other listservs new supervisors may find useful are Teaching Behavior Analysis (https://listserv.uhd.edu/scripts/wa-UHDEDU.exe?A0=TBA-L) and Ethics and Behavior Analysis listserv (https://listserv.uhd.edu/scripts/wa-UHDEDU.exe?A0=EBA).

As part of networking and establishing a verbal community, new supervisors may also have opportunities to receive formal coaching or consultation on supervision skills when new or difficult-to-handle performance management issues arise. Tandem supervision activities, in which a peer supervisor joins a new supervisor for a meeting with a supervisee (with the supervisee’s consent) can be particularly helpful. Peers who are also supervisors can offer a different perspective, and provide coaching, feedback, and additional supports as needed.

Conclusion

Behavior analytic supervision best practices are one mechanism of quality control to ensure client outcomes and therapeutic gains along with training and supervising. As our field continues to expand and the demand for behavior analytic services continues to increase newly certified BCBAs are asked to hold supervisory roles almost immediately after becoming credentialed (LeBlanc & Luiselli, 2016) and new supervisors may be expected to effectively manage a full caseload within a short period. Quickly developing proficiency with supervisory skills, using effective strategies to manage time, and demonstrating effective organization skills are essential for the work of new supervisors.

To support new supervisors during their 1st year as certified behavior analysts, the BACB established an added level of accountability by formalizing the consulting supervisory relationship. Sellers, Valentino, and LeBlanc (2016b) offered supervisors five recommendations to guide individual supervision. We adapted those five recommendations for new supervisors and provided suggestions for resources and tools. Along with the consulting supervisors’ guidance, we hope that the recommendations will guide new supervisors on how to effectively seek and find a consulting supervisor, identify goals and develop a structure for the consultative relationship, develop and refine their proficiency with supervisory and ethics related skills, and maintain professional relationships and development beyond the formal end of the consultative relationship. Although the recommendations are based on previously published literature, the recommendations have not been experimentally validated or established as best practices. Future endeavors that empirically evaluate the utility of the five recommendations may offer ways to refine them, identify those that may be especially valuable for new supervisors to follow, or provide other recommendations new supervisors may find useful.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Amber Valentino for her guidance and input on previous versions of this article.

Appendix 1

Email Template

Dear SUPERVISOR,

I hope this email finds you well. I am reaching out to introduce myself. My name is INSERT and I am a newly certified Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) after passing my examination in MONTH YEAR. I also recently met qualifications to supervise trainees' fieldwork experiences and am seeking a consulting supervisor. After reviewing the BACB certificant registry, I noted that you meet the requirements to serve as a consulting supervisor and that you are listed as willing to supervise BCBAs. I wanted to reach out so you can get to know me and to see if you are interested in or able to provide the consultation I am seeking.

To give you a little background about me, I received my DEGREE from UNIVERSITY/COLLEGE in YEAR. Much of my training involved working with POPULATION in SETTING, but I also have experience with INSERT OTHER EXPERIENCES. I have attached a copy of my CV/resume in case you would like to see more specific details about these roles and the dates I held each position. My experiences supervising others have included INSERT.

I currently work at a SETTING where my primary responsibilities include:

INSERT LIST OF RESPONSIBILITIES

In order for me to be successful as a new BCBA supervisor, the types of support I may need from my consulting supervisors include INSERT. The reason I am interested in establishing a supervisory relationship with you is INSERT.

To help me gather some additional information about what a consultative relationship could look like if we worked together, I created a list of questions to generate some additional discussion:

INSERT LIST OF QUESTIONS

Thank you in advance for your time and consideration of this email. I look forward to hearing your thoughts and would be more than happy to answer any questions you may have as well as schedule a time to chat further either via phone or virtual meeting.

Take care,

NAME

Appendix 2

Supervision Self-Monitoring Tool

| Supervisor’s Name | Date of Meeting | ||

| Supervisee’s Name | Location of Meeting | ||

| Rating Key |

1 = all of the time/agree 2 = some of the time/neutral 3 = never/disagree |

||

| Organization | ||||

| Item | Score | |||

| The meeting began on time (as scheduled) | Yes | No | ||

| The meeting was free from distractions | Yes | No | ||

| I was prepared for the meeting | Yes | No | ||

| Notes: | ||||

| Expectations and Professionalism | ||||

| Item | Score | |||

| I communicated effectively with my supervisee regarding meeting expectations (e.g., preparation of agenda, meeting time, and location) | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| I set clear expectations about the context of supervision | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| I gave appropriate and clear deadlines for assigned tasks | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| I modeled ethical and professional behavior | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| I maintained a positive body position and engaged in appropriate non-verbal behavior throughout the meeting | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| I refrained from interrupting my supervisee while they were speaking | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| Notes: | ||||

| Clinical and Ethical Expertise | ||||

| Item | Score | |||

| I modeled clinical decision-making skills using evidence-based teaching strategies | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| I modeled technical, behavior analytic skills using evidence-based teaching strategies | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| I modeled ethical decision-making skills using evidence-based practices | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| I had enough clinical expertise to accurately answer questions posed by my supervisee or refrained from answering questions outside of my scope of competence | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| I asked my supervisee questions to gather more information to further discussion | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| Notes: | ||||

| Teaching and Performance Monitoring | ||||

| Item | Score | |||

| I followed up with feedback on previous observations of my supervisee during the meeting | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| When introducing a new skill, I provided a model/demonstration of the skill | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| I provided opportunities for my supervisee to practice skills and receive feedback on their performance | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| I scheduled a time to directly observe my supervisee practice skills with clients | Yes | No | ||

| I collected data on my supervisee’s performance to make decisions about the effectiveness of supervision | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| I provided positive and corrective feedback to my supervisee | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| I helped my supervisee set goals and established criteria to measure mastery | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| The topics discussed during supervision can be linked to the BACB 5th ed. task list | 1 | 2 | 3 | N/A |

| Notes: | ||||

| Social Validity | ||||

| Item | Score | |||

| I enjoyed the supervision meeting | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| I feel I have enough time in my schedule to allow for adequate supervision of my supervisee | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| I have good rapport with my supervisee | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Notes: | ||||

Adapted from Turner et al. (2016)

Appendix 3

Recommendations Action Items Checklist

Recommended Practices for Individual Supervision: Considerations for the Behavior-Analytic

Trainee. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 10.1007/s40617-021-00557-9

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Allen D. Getting things done: The art of stress-free productivity. Penguin; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alvero AM, Bucklin BR, Austin J. An objective review of the effectiveness and essential characteristics of performance feedback in organizational settings (1985–1998) Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2001;21(1):3–29. doi: 10.1300/J075v21n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andzik NR, Kranak MP. The softer side of supervision: Recommendations when teaching and evaluation behavior-analytic professionalism. Behavior Analysis: Research & Practice. 2021;21(1):65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J, Burch M. Ethics for behavior analysts. Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2017). BCBA/BCaBA task list (5th ed.). Littleton, CO.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2018). Supervision training curriculum outline (2.0). Littleton, CO.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2019). Newsletters. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/BACB_November2019_Newsletter-200826.pdf. Retrieved 1 Feb 2022.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts. https://bacb.com/wp-content/ethics-code-for-behavior-analysts/. Retrieved 1 Feb 2022.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2021). Consulting supervisors requirements for new BCBAs supervising fieldwork. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Consultation-Supervisor-Requirements-and-Documentation_211130.pdf. Retrieved 1 Feb 2022.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2022a). U.S. employment demand for behavior analysts: 2010–2021. Littleton, CO.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2022b). BCBA handbook. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/BCBAHandbook_210513.pdf. Retrieved 14 Mar 2022.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.). ACE provider handbook. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ACE-Provider-Handbook_211221.pdf

- Britton LN, Crye AA, Haymes LK. Cultivating the ethical repertoires of behavior analysts: Prevention of common violations. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2021;14(2):534–548. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00540-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodhead MT, Quigley SP, Wilczynski SM. A call for discussion about scope of competence in behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;11(4):424–435. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00303-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton M, Kagan C. The verbal community and the societal construction of consciousness. Behavior and Social Issues. 1994;4(1):87–96. doi: 10.5210/bsi.v4i1.210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa M, Robertson A. Precision teaching and fluency training: Making math easier for pupils and teachers. Educational Psychology in Practice. 2000;16(3):297–310. doi: 10.1080/713666088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi E, Johnson DA, Moon K, Oah S. Effects of positive and negative feedback sequence on work performance and emotional responses. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2018;38(2–3):97–115. doi: 10.1080/01608061.2017.1423151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, B. P., Hoffmann, A. N., & Slocum, T. A. (2021). Ethical behavior analysis: Evidence-based practice as a framework for ethical decision making. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 15(2), 619–634. 10.1007/s40617-021-00658-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Ditzian K, Wilder DA, King A, Tanz J. An evaluation of the performance diagnostic checklist-human services to assess an employee performance problem in a center-based autism facility. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2018;48(1):199–203. doi: 10.1002/jaba.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon DR, Linstead E, Granpeescheh D, Novack MN, French R, Stevens E, Powell A. An evaluation of the impact of supervision intensity, supervisor qualifications, and caseload on outcomes in the treatment of autism spectrum disorder. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:339–348. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0132-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich RJ, Nosik MR, Carr JE, Wine B. Teaching employees how to receive feedback: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2020;40(1–2):19–29. doi: 10.1080/01608061.2020.1746470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garza KL, McGee HM, Schenk YA, Wiskirchen RR. Some tools for carrying out a proposed process for supervising experience hours for aspiring Board Certified Behavior Analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;11(1):62–70. doi: 10.1007/s40617-017-0186-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz HG, Agnew D. A supervision model for public agency clinicians. The Clinical Supervisor. 1999;18(2):51–62. doi: 10.1300/J001v18n02_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gravina N, Villacorta J, Albert K, Clark R, Curry S, Wilder D. A literature review of organizational behavior management interventions in human service settings from 1990 to 2016. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2018;38(2–3):191–224. doi: 10.1080/01608061.2018.1454872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hajiaghamohseni Z, Drasgow E, Wolfe K. Supervision behaviors of board certified behavior analysts with trainees. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2021;14:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00492-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin ER, Timberlake EM. Peer group supervision for supervisors. Social Casework. 1982;63(2):82–87. doi: 10.1177/104438948206300203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley BK, Courtney WT, Rosswurm M, LaMarca VL. The apprentice: An innovative approach to meet the Behavior Analyst Certification Board’s supervision standards. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(4):329–338. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0136-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes N. Time management: Get an extra day a week. (4th ed.) Logical Operations; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Helvey, I., Thuman, E., & Cariveau, T. (2021). Recommended practices for individual supervision: Considerations for the behavior-analytic trainee. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 15(1), 370–381. 10.1007/s40617-021-00557-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johnson KJ, Street EM. Response to intervention and precision teaching: Creating synergy in the classroom. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Komaki JL. Toward effective supervision: An operant analysis and comparison of managers at work. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1986;71(2):270–279. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.2.270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc LA, Luiselli JK. Refining supervisory practices in the field of behavior analysis: Introduction to the special section on supervision. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(4):271–273. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0156-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc LA, Sellers TP, Alai S. Building and sustaining meaningful and effective relationships as supervisor and mentor. Sloan; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc LA, Taylor BA, Marchese NV. The training experiences of behavior analysts: Compassionate care and therapeutic relationships with caregivers. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2020;13:387–393. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00368-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mager RF. Making instruction work. (2nd ed.) CEP Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer V, Turkat ID. Behavioral analysis of clinical cases. Journal of Behavioral Assessment. 1979;1(4):259–270. doi: 10.1007/BF01321368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mourad M, Kohlwes J, Maselli J, Auerbach AD. Supervising the supervisors—Procedural training and supervision in internal medicine residency. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(4):351–356. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1226-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman B. Behavioral detectives: A staff training exercise book in applied behavior analysis. Dove & Orca; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ninci J, Čolić M, Hogan A, Taylor G, Bristol R, Burris J. Maintaining effective supervision systems for trainees pursuing a Behavior Analyst Certification Board Certification during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2021;14(4):1047–1057. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00565-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons MB, Rollyson JH, Reid DH. Evidence-based staff training: A guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;5:2–11. doi: 10.1007/BF03391819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid DH, Parsons MB, Green CW. The supervisor’s guidebook: evidence-based strategies for promoting work quality and enjoyment among human service staff. Habilitative Management Consultants; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer JM, Andzik NR. Evaluating behavioral skills training as an evidence-based practice when training parents to intervene with their children. Behavior Modification. 2021;45(6):887–910. doi: 10.1177/0145445520923996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers TP, Alai-Rosales S, MacDonald PF. Taking full responsibility: The ethics of supervision in behavior analytic practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:299–308. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0144-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers TP, Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA. Recommended practices for individual supervision of aspiring behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(4):274–286. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0110-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers TP, Valentino AL, Landon TJ, Aiello S. Board certified behavior analysts’ supervisory practices of trainees: Survey results and recommendations. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(3):536–546. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00367-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sush D, Najdowski A. A workbook of ethical case scenarios in applied behavior analysis. Academic Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tulgan B. Bridging the soft-skills gap. Employment Relations Today. 2016;42(4):25–33. doi: 10.1002/ert.21536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner LB, Fischer AJ, Luiselli JK. Towards a competency-based, ethical, and socially valid approach to the supervision of applied behavior analytic trainees. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(4):287–298. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA, Sellers TP. The benefits of group supervision and recommended structure for implementation. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(4):320–328. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0138-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Someren MW, Barnard YF, Sandberg JA. The think aloud method: A practical approach to modelling cognitive. Academic Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Walker S, Sellers T. Teaching appropriate feedback reception skills using computer-based instruction: A systematic replication. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2021;41(3):236–254. doi: 10.1080/01608061.2021.1903647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins CE., Jr Being and becoming a psychotherapy supervisor: The crucial triad of learning difficulties. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 2013;67(2):134–150. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2013.67.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger EC, Snyder WM. Communities of practice: The organizational frontier. Harvard Business Review. 2000;78(1):139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Wilder D, Lipschultz J, Gehrman C. An evaluation of the Performance Diagnostic Checklist: Human Services across domains. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;11(2):129–138. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-0243-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpe, J., & Turkat, I. D. (1985). Behavioral formulation of clinical cases. Behavioral case formulation (pp. 5–36). Boston: Springer.