Abstract

The infectious stage of amebae is the chitin-walled cyst, which is resistant to stomach acids. In this study an extraordinarily abundant, encystation-specific glycoprotein (Jacob) was identified on two-dimensional protein gels of cyst walls purified from Entamoeba invadens. Jacob, which was acidic and had an apparent molecular mass of ∼100 kDa, contained sugars that bound to concanavalin A and ricin. The jacob gene encoded a 45-kDa protein with a ladder-like series of five Cys-rich domains. These Cys-rich domains were reminiscent of but not homologous to the Cys-rich chitin-binding domains of insect chitinases and peritrophic matrix proteins that surround the food bolus in the insect gut. Jacob bound purified chitin and chitin remaining in sodium dodecyl sulfate-treated cyst walls. Conversely, the E. histolytica plasma membrane Gal/GalNAc lectin bound sugars of intact cyst walls and purified Jacob. In the presence of galactose, E. invadens formed wall-less cysts, which were quadranucleate and contained Jacob and chitinase (another encystation-specific protein) in secretory vesicles. A galactose lectin was found to be present on the surface of wall-less cysts, which phagocytosed bacteria and mucin-coated beads. These results suggest that the E. invadens cyst wall forms when the plasma membrane galactose lectin binds sugars on Jacob, which in turn binds chitin via its five chitin-binding domains.

Entamoeba histolytica is a luminal protozoan parasite, which is a frequent cause of dysentery and liver abscess in persons in developing countries that cannot prevent its fecal-oral spread (37). E. histolytica is part of a family of microaerophilic amebae, which reside as commensals in the human colon (Entamoeba dispar and Entamoeba coli) or survive as free-living organisms in garbage (Entamoeba moscovshii) (12). The infectious stage of amebae is the chitin-walled, quadranucleate cyst, which is resistant to stomach acids (2, 15). Because it is not possible to discriminate cysts of E. histolytica and E. dispar by microscopy, cysts identified in clinical samples are called “E. histolytica/E. dispar” (51).

Since E. histolytica parasites do not encyst in axenic culture, cyst formation has been studied using the reptilian pathogen Entamoeba invadens, which also forms a quadranucleate cyst (15). E. invadens, which is more closely related to E. histolytica than to the human commensal E. coli, converts to cysts within 2 days when deprived of glucose (38, 40). Amebic cyst wall proteins include 100- and 150-kDa glycoproteins, which bind wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), and uncharacterized antigens, which react with monoclonal anti-cyst antibodies (7, 49). Chitin (β-1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine [GlcNAc]) is also present in amebic cyst walls (2). Although neither chitin synthase nor chitinase is present in amebic trophozoites, both enzymes are expressed by encysting parasites (3, 10, 47). Amebic chitinases, which have catalytic domains like those of nematode, insect, and plant chitinases, are present in hundreds of small cyst-specific secretory vesicles (4, 11, 19, 23, 39, 46).

Amebae have a plasma membrane Gal/GalNAc lectin, which may also be involved in encystation (8, 9). This lectin, which has been best characterized on the surface of E. histolytica trophozoites, binds to galactose or N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) on bacteria, red blood cells and epithelial cells, or mucin-coated beads (13, 20). The E. histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin is composed of a large 170-kDa subunit, which has a transmembrane domain near its C terminus, and a small 35-kDa subunit, which has a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor at its C terminus (29, 31, 36, 44). An E. invadens gene encoding a homologue of the Gal/GalNAc lectin small subunit has been cloned (GenBank accession number AF016642). Since galactose but not GalNAc inhibits the aggregation and encystation of E. invadens parasites in vitro, it may be more accurate to refer to the E. invadens plasma membrane “galactose lectin” (8). It has been suggested that galactose exerts its effect on aggregation and encystation by blocking signal transduction mediated by the galactose lectin (9). Previously, inside-out signaling by cytosolic domains of the Gal/GalNAc lectin was shown to be important for epithelial cell adherence and amebic virulence (48).

In this study, two-dimensional protein gels identified an abundant E. invadens cyst wall glycoprotein, which was called Jacob because it contained a ladder-like series of Cys-rich, chitin-binding domains. Jacob also contained sugars, which were recognized by the galactose lectin on encysting E. invadens, such that wall-less cysts formed in the presence of excess galactose.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparations of cysts and trophozoites.

The IP-1 strain of E. invadens was grown at 25°C in axenic culture in TYI-SS medium (15). E. invadens encystation was induced by placing parasites for 48 h in low-glucose (LG) medium, which has reduced osmolarity, glucose, and serum levels with respect to TYI-SS medium (38). Cysts walls were identified by staining with 2 μg of Calcofluor per ml, which binds to chitin and emits a blue fluorescence when excited with UV light (5). Chitin and other carbohydrates in cyst walls were also stained with 50 μg each of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated concanavalin A (FITC-ConA), FITC-ricin, or tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated (TRITC)-WGA per ml for 60 min at room temperature in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and washed four times. Cyst nuclei were identified by permeabilizing cysts with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and staining with 1 μM Sytox green.

In an attempt to inhibit cyst wall formation, E. invadens parasites were placed in LG medium containing 100 mM lactose, galactose, GalNAc, or mannose and incubated for 2 to 4 days at room temperature. Wall-less cysts, which were formed in the presence of galactose, were motile, had four nuclei, and contained Jacob and chitinase in secretory vesicles (see below) but lacked a chitin wall. Because a rabbit anti-E. histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin antibody did not bind to E. invadens trophozoites, the E. invadens galactose lectin was indirectly detected on trophozoites and wall-less cysts by incubating them with green fluorescent protein-labeled bacteria with or without galactose (45). Wall-less cysts were also incubated in the absence of galactose with mucin-coated beads or uncoated beads (negative control) (20).

Two-dimensional SDS-PAGE of purified cyst walls.

To purify cyst walls, we separated cysts from adherent trophozoites by decanting unchilled flasks. Residual trophozoites were lysed by five short pulses with a sonicator. Cysts were concentrated by centrifugation and resuspended in PBS plus 100 μM E-64 to inhibit amebic cysteine proteases. The cysts were broken by extensive sonication (≥50 pulses), and cyst walls were separated from cytosol, membranes, nuclei, and intact cysts by centrifugation through two 60% sucrose cushions (2). Cyst wall preparations, which were checked by phase-contrast microscopy, fluorescence microscopy with Calcofluor, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), contained less than one intact cyst per 100 walls and no trophozoites.

Purified cyst walls were boiled in 1% SDS–5% β-mercaptoethanol (2-ME), and the supernatant of a microcentrifuge centrifugation was mixed with lysis buffer (540 mg of urea per ml, 2% Triton X-100, 2% 2-ME, 2% ampholines 3 to 10, 100 μg of E-64 per ml) and electrophoresed on two-dimensional gels (35). Precast gels (Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden) contained amphollytes from pH 3 to pH 10 in the first (isoelectric-focusing) dimension and a gradient of acrylamide from 10 to 20% in the second (SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [PAGE]) dimension. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue or silver (to identify less abundant cyst wall proteins). The most abundant cyst wall glycoprotein (Jacob), which was acidic and was 100 kDa, was excised from a Coomassie blue-stained gel and digested with trypsin. Tryptic peptides were separated by high-pressure liquid chromatography, and N-terminal sequences were obtained by Edman degradation (32). Alternatively, two-dimensional protein gels of cyst wall proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) filters, and Jacob, identified with Ponceau-S., was excised for N-terminal sequencing. Some PVDF membranes were blocked with powdered milk and treated with anti-Jacob antibodies or the E. histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin (as described below). Other PVDF membranes were also incubated with biotinylated ConA, ricin, WGA, or Sambucus nigra agglutinin (all 4 μg/ml in PBS), washed, and developed with avidin conjugated to alkaline phosphatase.

Cloning of the E. invadens jacob gene.

A segment of the E. invadens jacob gene was isolated from DNA of E. invadens IP-1 using PCR and degenerate primers to N-terminal sequences of tryptic Jacob peptides (24). A degenerate sense primer, CA(AG)TA(CT)TT(CT)GA(AG)TG(CT)(AT)(CG)(AT)AA(CT)AC, was to QYFECSNT, while an antisense primer, AC(AG)TA(AG)TA(CT)TG(AG)AA(AG)TC(AG)TG, was to HDFQYYV. The jacob PCR product, which was 488 bp long, was cloned in TA vector and sequenced by dideoxy methods. The jacob PCR product was used to identify jacob gDNA clones from an E. invadens IP-1 strain DNA gDNA library (38). Like other E. invadens genes, the E. invadens jacob coding sequence contained no introns and had a 51% A+T content in the third position (11, 19, 38). The E. invadens Jacob protein was compared with proteins in the GenBank and EST databases and with products of unfinished microbial genomes by using BLAST (1). N-terminal signal sequences were predicted and potential transmembrane segments identified using well-established algorithms (16, 34).

Production of anti-Jacob antibodies, Western blots, and indirect immunofluorescence microscopy.

E. invadens Jacob was excised from 10 two-dimensional protein gels, mixed with complete Freund's adjuvant, and injected into rabbits. The rabbits were boosted at 3 and 6 weeks with Jacob from five gels each in incomplete Freund's adjuvant. Western blots of two-dimensional gels of cyst wall proteins were incubated for 60 min at 25°C with anti-Jacob serum diluted 1:1,000 in PBS. Filters were washed and incubated in anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated to peroxidase (1:2,000 dilution), which was detected using chemiluminescent reagents.

To localize Jacob on the surface of E. invadens cysts, parasites were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 4°C, washed in PBS, and immunostained for 60 min at 37°C with rabbit anti-Jacob sera, diluted 1:100 in PBS containing 1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml. To localize Jacob within secretory vesicles of encysting E. invadens parasites, amebae were permeabilized by incubation with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature and then immunostained with rabbit anti-Jacob, which was also diluted 1:100. The organisms were washed four times and immunodecorated for 60 min with a Texas red-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antiserum. As a negative control, parasites were stained with preimmune rabbit serum. As a positive control, encysting parasites were stained with TRITC-WGA, which binds chitin. Alternatively, parasites were incubated with a rabbit anti-E. invadens chitinase antibody, which was previously made to a multiantigenic peptide containing chitinase repeats (19). Nuclei were stained with Sytox green, and parasites were observed with a Leica NT-TCS confocal microscope fitted with argon and krypton lasers. Three-dimensional reconstructions were made from a series of optical sections, which were made at 0.5- to 1-μm intervals.

TEM and immuno-EM of encysting parasites.

Cysts and purified cyst walls were fixed for 10 min in 1% paraformaldehyde, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, stained en block with uranyl acetate, dehydrated, and embedded in Epon. Sections, which were 60 nm thick, were stained on the grid with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. To visualize Jacob on the surface of cysts or wall-less cysts, encysting parasites were fixed in paraformaldehyde, incubated with anti-Jacob antibodies as described for fluorescence microscopy, and then incubated with Staphylococcus protein A, which had been conjugated to 10-nm-diameter gold particles. A negative control included preimmune rabbit serum. Parasites were washed and prepared for TEM as described above. Alternatively, parasites were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, infiltrated with 2.3 M sucrose, and frozen. Ultrathin sections were incubated with the anti-Jacob serum and protein A-gold complex. These parasites were prepared for TEM in the absence of osmium tetroxide, so that the membranes remained unstained.

Methods to demonstrate binding of Jacob to chitin.

To obtain soluble forms of Jacob, E. invadens parasites were encysted for 24 h and cytosolic extracts were made by sonicating parasites in the presence of E-64. These extracts were incubated with SDS-treated cyst walls, chitin beads, or GlcNAc beads, which were washed and then incubated with rabbit anti-Jacob antibodies and immunodecorated as described above. Negative controls included cytosolic extracts from E. invadens trophozoites, nonimmune sera, and Sepharose or agarose beads. In addition, extracts of E. histolytica bound to chitin beads were stained with antibodies to alcohol dehydrogenase 1 or Ariel (negative controls) (22, 28). Amebic proteins binding to chitin beads were also eluted with 1% SDS–5% 2-ME and run on one-dimensional SDS-PAGE. Gels were transferred to nitrocellulose filters and incubated with anti-Jacob antibodies, which were detected with chemiluminescent reagents. A positive control included cyst wall proteins, which were run in a parallel lane.

Methods to demonstrate binding of the Gal/GalNAc lectin to Jacob.

Binding of the E. histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin to cyst walls and to Jacob was demonstrated in three ways. First, E. histolytica HM-1 parasites were stained with a nonspecific cytosolic stain, CFDA SE (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) and incubated for 3 h at 37°C with intact E. invadens cysts, which were stained with Calcofluor. Phagocytosis of cysts by trophozoites was determined by fluorescence microscopy. Negative controls included trophozoites incubated with cyst walls after treatment with SDS to remove Jacob and other glycoproteins, as well as incubation of trophozoites with cyst walls in the presence of excess galactose. Second, E. invadens cysts were incubated with 5 μg of purified Gal/GalNAc lectin from HM-1 trophozoites per ml (36). Cysts were washed, and bound lectin was detected with a 1:500 dilution of rabbit anti-lectin antibodies (29), which were immunodecorated as described for anti-Jacob antibodies. Negative controls included replacement with SDS-treated cyst walls, addition of excess galactose to Gal/GalNAc lectin, omission of the lectin, or incubation with nonimmune rabbit serum. Third, a Western blot of a two-dimensional gel of Jacob was incubated with the Gal/GalNAc lectin, washed, and incubated with anti-lectin antibodies, which were detected with chemiluminescent reagents. A negative control was included in which the Gal/GalNAc lectin was omitted.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequence of the jacob gene have been submitted to GenBank with accession number AF175527.

RESULTS

The most abundant cyst wall protein is an acidic, 100-kDa glycoprotein (Jacob).

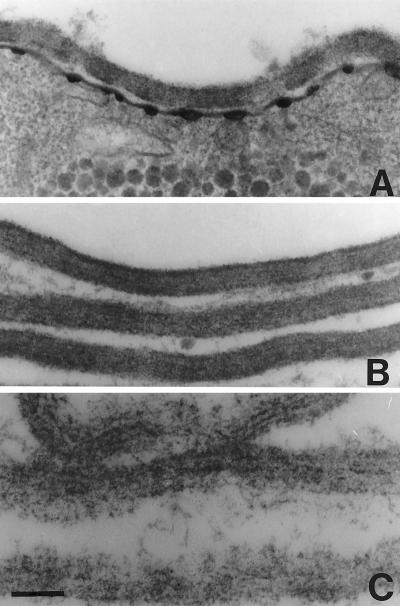

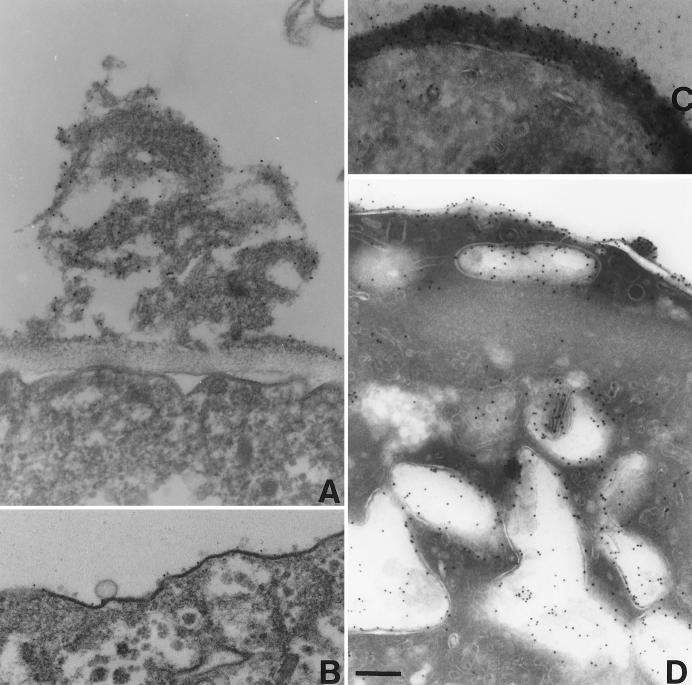

The walls of E. invadens cysts were electron dense and had a uniform thickness of ∼100 nm (Fig. 1A). Electron-dense material was also present in secretory vesicles and along the plasma membrane. Purified cyst walls, which were prepared on sucrose gradients after sonication of cysts, closely resembled the walls of intact cysts (Fig. 1B). After the cyst walls were boiled in SDS and 2-ME, only fibrils, which were less tightly bound to each other, remained (Fig. 1C). These fibrils are presumably made of chitin, because they stained with Calcofluor (data not shown) (2).

FIG. 1.

Transmission electron micrographs of E. invadens cyst walls. (A) Intact E. invadens cysts have an electron-dense wall, which overlies secretory vacuoles and electron densities along the plasma membrane. (B) Cyst walls purified by two sucrose gradients contain electron-dense material between chitin fibrils. (C) Chitin fibrils and little other electron-dense material remain in cyst walls after boiling in SDS. Bar, 200 nm. Magnification, ×4,500.

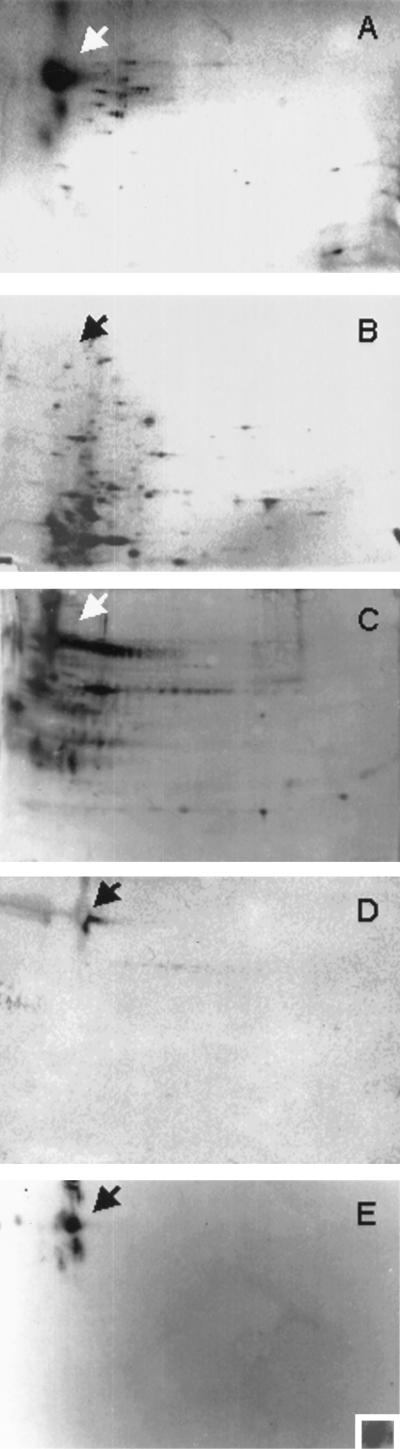

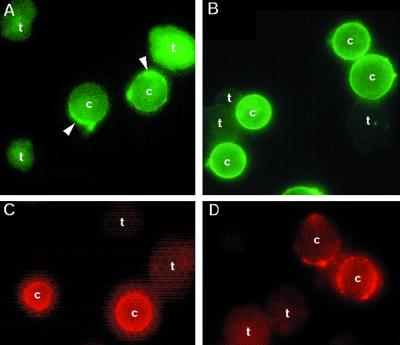

More than a dozen cyst wall proteins (Fig. 2A), which were absent from trophozoites (Fig. 2B), were identified by two-dimensional SDS-PAGE (35). Some of these cyst wall proteins formed multiple spots, which were the same size but had different isolectric points. The most abundant cyst wall-specific protein (Jacob) was acidic and had an apparent molecular mass of ∼100 kDa. Jacob and other amebic cyst wall proteins were glycoproteins, which bound ConA (Fig. 2C). Jacob also bound ricin (Fig. 2D) and WGA (data not shown) but did not bind S. nigra agglutinin. Rabbit antibodies to purified Jacob bound to the 100-kDa spot and to higher- and lower-molecular-mass spots (Fig. 2E), which had the same isoelectric point as Jacob but were less abundant. Fluorescence microscopy was used to confirm the Western blot findings. ConA (Fig. 3A) and ricin (Fig. 3B) bound much more extensively to the surface of cysts than to the surface of trophozoites, while anti-Jacob antibodies bound to cysts but not to trophozoites (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 2.

Two-dimensional gels of E. invadens cyst wall proteins. (A and B) Silver stains show that Jacob, which is by far the most abundant cyst wall protein (arrow in panel A), is absent from trophozoites (B). (C and D) Western blots show that ConA (C) and ricin (D), visualized with acid phosphatase, bind to Jacob and numerous other cyst wall glycoproteins. (E) In contrast, anti-Jacob antibodies, visualized by chemiluminescence, bind to Jacob and larger and smaller proteins with the same charge. Purified E. histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin, which was detected with anti-lectin antibodies, binds to Jacob excised from a Ponceau-stained two-dimensional gel (inset in panel E). A negative control, in which the Gal/GalNAc lectin was omitted, did not bind the anti-Gal/GalNAc antibodies (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Fluorescence micrographs of E. invadens cysts and trophozoites. (A and B) FITC-ConA (arrowheads in panel A) and FITC-ricin (B) stained the surface of cysts (c) much more intensely than the surface of trophozoites (t). (C) Similarly, anti-Jacob antibodies, made to the native Jacob protein, bound to the surface of cysts but not to trophozoites. (D) The E. histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin, which was detected with anti-lectin antibodies, also bound to E. invadens cyst walls but not to the surface of trophozoites.

Jacob contains five Cys-rich domains, separated by acidic spacers.

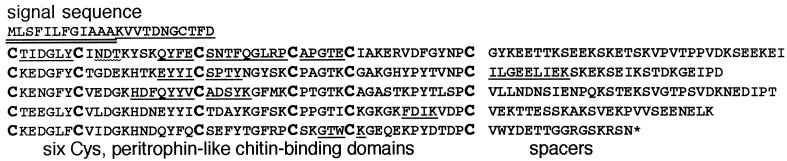

N-terminal sequences of tryptic peptides of Jacob were used to design degenerative oligonucleotide primers to obtain a segment of the E. invadens jacob gene by PCR (24). The jacob PCR product was in turn used to obtain the entire coding region of the jacob gene of E. invadens, which predicted a 405-amino-acid protein (Fig. 4). The formula weight of Jacob (Mr 45,122) was less than half the apparent molecular mass (100 kDa) of Jacob on two-dimensional protein gels (Fig. 2A). A signal sequence (MLSDILFGIAAA), which was identified by sequencing the N terminus of undigested Jacob, was cleaved at a site predicted by the -3,-1 rule as applied to eubacteria rather than eukaryotes (34). The predicted E. invadens Jacob also contained N-terminal sequences of peptides obtained from tryptic digests of Jacob. The amino acid composition of the predicted protein, which was rich in acidic (16%), basic (15%), and polar (43%) amino acids, matched that of Jacob excised from the gel.

FIG. 4.

Primary structure of E. invadens Jacob, in single-letter code. An asterisk marks the stop codon. The signal sequence, proven by N-terminal sequencing of intact Jacob, is underlined twice, while the N-terminal sequences of Jacob tryptic peptides are each underlined once. PCR primers for cloning the E. invadens jacob gene were made to QYFECSNT and HDFQYYV. A possible site of Asn-linked glycosylation (NDT) is marked with a wavy underline. Conserved Cys residues in putative chitin-binding domains, which are aligned, are marked in bold.

Jacob had one site of possible N-linked glycosylation (Asn33) and numerous Ser and Thr residues for possible O-linked glycosylation (21) (Fig. 4). Jacob did not have any predicted transmembrane segments (16). Instead, it was composed of five similar domains, each of which contained six Cys residues spaced 7, 12, 9, 5, and 12 amino acids apart. Chitin-binding domains of peritrophins and fungal, nematode, and insect chitinases have mirror-image spacing of Cys residues, which are 12, 5, 9, 12, and 7 amino acids apart (all ±1) (17, 23, 39, 46). Jacob repeat domains also contained conserved aromatic amino acids (Tyr, Phe, and Trp), which may be involved in binding sugars, as described for WGA (52). Between the Jacob repeat domains were acidic domains, which were similar in their composition but not their sequence to repeats in amebic chitinases, Ser-rich E. histolytica proteins, or Ariel surface protein (11, 28, 41). There were no proteins homologous to amebic Jacob in GenBank, EST, or unfinished microbial genome databases, although BLAST with Jacob identified the large subunit of the E. histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin and Giardia lamblia variable surface proteins, which are also Cys rich (1, 29, 33, 44).

Jacob, which is released from multiple loci to the surface of encysting parasites, is a chitin-binding lectin.

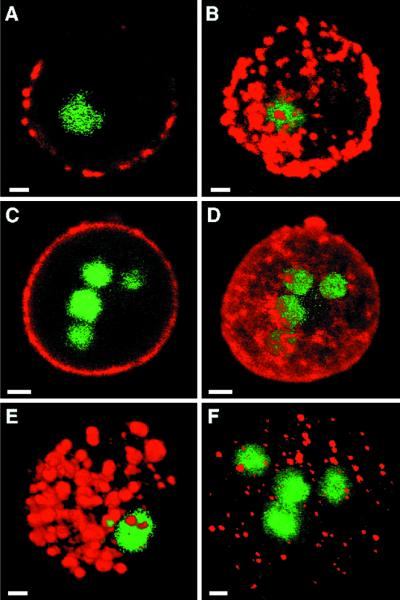

Jacob mRNAs, detected by reverse transcription-PCR, were abundant in extracts of E. invadens cysts but were weakly present in extracts of trophozoites, which inevitably contain some encysting parasites (data not shown). Encystation-specific expression of Jacob was similar to but more abundant than that of chitinase (11). Anti-Jacob antibodies showed that Jacob was secreted from numerous foci onto the surface of encysting parasites with one nucleus (Fig. 5A and B) and continued until cysts had four nuclei (Fig. 5C and D). Jacob was present as electron-dense material in clumps between and on the surface of chitin fibrils (Fig. 6A and C). Jacob was also present in numerous large secretory vesicles in encysting parasites (Fig. 5E and 6D). These Jacob-associated secretory vesicles were larger than those visualized with anti-chitinase antibodies (Fig. 5F). It is possible that small chitinase-containing vesicles are lysosomes, which are released during excystation.

FIG. 5.

Confocal micrographs of encysting E. invadens stained with anti-Jacob antibodies (red in panels A through E), anti-chitinase antibodies (red in panel F) and Sytox green (nuclear stain in panels A through F). Jacob was present in multiple places on the surface of encysting parasites with one nucleus (in section [A] and three-dimensional composite [B]) and became more dense on parasites with four nuclei (in section [C] and composite [D]). Jacob was present in numerous relatively large secretory vesicles (in composite [E]) that surround the nuclei of encysting parasites, which were permeabilized before labeling. Chitinase (in composite [F]) was present within hundreds of smaller secretory vesicles of an encysting parasite. Bars, 5 μm.

FIG. 6.

Immuno-EM of anti-Jacob antibodies binding to cysts and wall-less cysts. (A) Anti-Jacob antibodies, visualized with gold particles, were present over electron-dense material on the surface of encysting parasites, which were stained prior to fixation. (B) In contrast, wall-less cysts, which were made in the presence of galactose, lacked chitin and had a thin layer of electron-dense material that bound few anti-Jacob antibodies. (C and D) When encysting parasites were fixed and sectioned prior to staining, anti-Jacob antibodies bound to cyst walls and to numerous large secretory vesicles. Bars, 200 nm. Magnification, ×4,500.

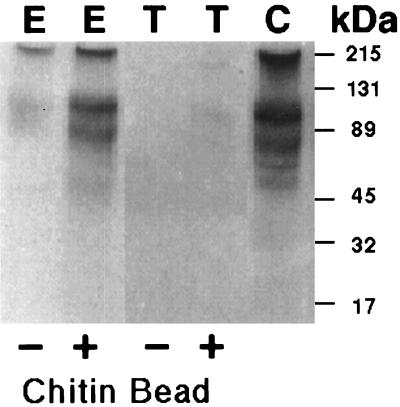

An extract of encysting E. invadens, which contained soluble Jacob, was incubated with purified cyst walls that had been treated with SDS to remove their proteins. Jacob, which was detected with anti-Jacob antibodies, bound to chitin remaining in SDS-treated cysts walls (data not shown). Anti-Jacob antibodies did not bind to SDS-treated cyst walls, which had not been pretreated with extracts of encysting parasites. Jacob also bound to chitin beads (Fig. 7). Jacob did not bind to Sepharose or agarose beads, while abundant E. histolytica proteins including alcohol dehydrogenase 1 and Ariel did not bind to either SDS-treated cyst walls or chitin beads (22, 28). These results suggest that the Cys-rich domains of Jacob, which resemble those of peritrophins and chitinase, are chitin-binding domains (17, 23, 39, 46).

FIG. 7.

SDS-PAGE and Western blots of Jacob binding to chitin beads. Western blots with anti-Jacob antibodies to trophozoite proteins (T) before (−) and after (+) binding to chitin beads, total proteins from encysting parasites (E) before (−) and after (+) binding to chitin beads, and cyst wall proteins (C) (positive control) are shown. Two bands labeled with anti-Jacob antibodies correspond to 100-kDa and high-molecular-mass forms of Jacob identified on two-dimensional protein gels (Fig. 2). Molecular mass standards are marked on the right.

Wall-less cysts are produced when amebae encyst in the presence of galactose.

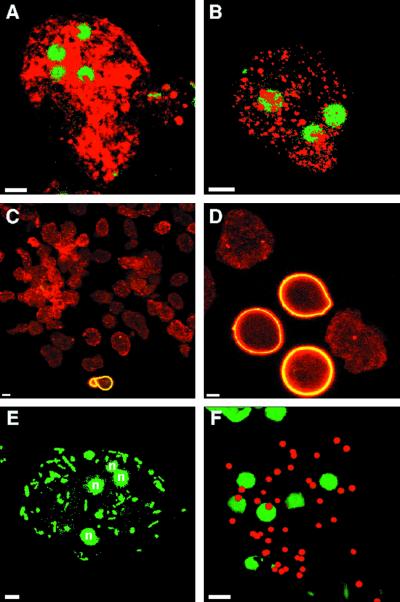

We confirmed here the previous observation that galactose is able to block aggregation and encystation by amebae in vitro (8, 9). Remarkably, galactose-treated parasites in encysting medium, which are referred to as wall-less cysts, were ameboid and quadranculeate, lacked Calcofluor-binding material on their surface, and were filled with numerous secretory granules containing Jacob and chitinase (Fig. 6B and 8A to C). Quadranucleate, wall-less cysts were also formed in the presence of lactose but not in the presence of GalNAc or mannose (data not shown). In contrast, negative-control parasites, which were treated with galactose in normal culture medium, were mononucleate and lacked Jacob and chitinase (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

Confocal micrographs of wall-less cysts, which were made by encysting E. invadens parasites for 2 days in the presence of 50 mM galactose. Wall-less cysts, which were permeabilized before labeling, had four nuclei (stained with Sytox green in panels A, B, E, and F) and contained numerous secretory vesicles stained with anti-Jacob antibodies (red in panel A) and anti-chitinase antibodies (red in panel B). The vast majority of wall-less cysts, which were labeled with anti-Jacob antibodies (red in panel C), lacked chitin on their surface, which was detected with WGA (yellow in panel C). In contrast, many control parasites encysting in the absence of galactose were spherical and bound WGA to their cyst walls (yellow in panel D). The galactose lectin was present on the surface of wall-less cysts, which phagocytosed GFP-labeled bacteria (stained green in panel E) or mucin-coated beads (stained red in panel F) when excess galactose was removed. Bars, 5 μm.

Galactose was demonstrated on the surface of cysts in three ways. First, purified E. histolytica plasma membrane Gal/GalNAc lectin, which was detected with a monospecific rabbit antibody to the E. histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin, bound to intact E. invadens cysts but not to E. invadens trophozoites or to E. invadens cysts treated with SDS to remove cyst wall glycoproteins (Fig. 3D). The anti-lectin antibody did not bind to cysts of negative controls in which the Gal/GalNAc lectin was omitted. Second, the E. histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin, again detected with the anti-lectin antibody, bound to Western blots of Jacob (inset in Fig. 2E), while a negative control without the E. histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin did not bind Jacob. These Western blots do not rule out the possibility that the Gal/GalNAc lectin binds to other cyst wall glycoproteins. Third, E. histolytica trophozoites rapidly phagocytosed intact E. invadens cysts but not SDS-treated cysts, and phagocytosis was inhibited by galactose (data not shown).

A putative E. invadens galactose lectin was shown on the surface of quadranucleate, wall-less cysts by two indirect methods. First, wall-less cysts phagocytosed bacteria labeled with green fluorescent protein (45), and the phagocytosis was inhibited by galactose (Fig. 8E). Second, wall-less cysts phagocytosed mucin-coated beads but not uncoated beads (Fig. 8F). Nonencysting E. invadens trophozoites also phagocytosed bacteria and mucin-coated beads (data not shown), suggesting the galactose lectin is constitutively expressed on E. invadens parasites.

DISCUSSION

A model of amebic cyst wall construction.

Our results suggest a two-lectin model of E. invadens cyst wall construction. First, the plasma membrane galactose lectin binds sugars on Jacob and perhaps other encystation-specific secretory glycoproteins that are part of the cyst wall (13, 29, 36, 44). Second, Jacob itself is a lectin with five Cys-rich domains, which bind chitin (3, 10, 47). Wall-less cysts are formed in the presence of galactose, because the galactose lectin no longer binds Jacob and other cyst wall glycoproteins and Jacob no longer binds chitin.

Weaknesses of this two-lectin model include the following. The gene encoding the large subunit of the E. invadens galactose lectin has not been identified. Conversely, the gene encoding the E. histolytica homologue of Jacob has not been identified. Sugars on Jacob have not yet been analyzed. The possibility that galactose blocks secretion of Jacob and chitinase cannot be ruled out. It is also possible that the E. invadens galactose lectin is involved in signal transduction during encystation, as has been suggested (9).

Examples of convergent and coincident evolution.

Jacob appears to be a chitin-binding lectin for three reasons. First, Jacob is localized to chitin-binding fibrils by immuno-EM. Second, Jacob binds chitin in SDS-treated cyst walls and binds chitin beads but does not bind to other carbohydrates such as Sepharose or agarose. Third, Jacob contains five putative domains, each of which has six Cys residues with conserved spacing and numerous aromatic amino acids present in chitin-binding domains of peritrophins and fungal, nematode, and insect chitinases (17, 23, 39, 46). Because the spacing between Cys residues in repetitive domains of Jacob is the mirror-image of those in lectin domains of peritrophins and chitinases, it appears that Jacob is related to these chitin-binding proteins by a common structure rather than a common ancestry (convergent evolution) (14). Convergent evolution is possible, because chitin-binding domains are short (∼50 amino acids) and contain fewer conserved residues than are present in the active sites of most enzymes.

The plasma membrane Gal/GalNAc lectin, which is implicated here in binding sugars on Jacob and cyst wall formation, is an important vaccine candidate on the surface of E. histolytica (29, 44). The Gal/GalNAc lectin is also an important virulence factor, because the amebic lectin binds sugars on host epithelial cells and red blood cells (13, 36, 37), as well as on bacteria, which are the major energy source for parasites in the distal colon (20). Although there is no fossil record to prove or disprove our assertion, it is likely that cyst wall formation is ancient and was present among free-living ancestors of amebae. Further invasion of host tissue is a reproductive dead end for amebae, which are spread by chitin-walled cysts (37). It seems likely, then, that the Gal/GalNAc lectin has been selected for its involvement in cyst wall formation and bacterial killing and that its involvement in host cell killing is an example of coincident evolution (20). Similar arguments have been made for coincident evolution of other amebic virulence factors including amebapores, cysteine proteinases, p21racA, and vacuolar ATPase (20, 25). Cysteine proteinases may also be important for cyst wall destruction during amebic excystation, as has been shown for excystation of Giardia (50).

Discrepancies with previous results.

There are at least two ways in which our results are different from what might have been expected from the literature on amebae. First, it is likely that wall-less cysts, which are formed in the presence of galactose, did not miss the signal for encystation, as recently suggested (9), because they are quadranucleate and produce encystation-specific Jacob and chitinase in abundance (11). Indeed, wall-less cysts resemble quadranucleate ameboid forms, which appear when parasites excyst in vitro (our unpublished observations). It is possible that the quadranucleate wall-less cysts were missed in recent studies of galactose-induced inhibition of encystation, because the assay for cysts involved putting parasites in water and treating them with detergent, which would lyse the wall-less cysts (8, 9). Second, although amebic lipophosphoglycans contain galactose, these galactose residues do not appear to be accessible on the surface of E. invadens or E. histolytica (42). E. histolytica trophozoites, which have the Gal/GalNAc lectin on their surface, do not adhere to and phagocytose each other (29, 36, 43). E. invadens and E. histolytica parasites fail to bind ricin by fluorescence microscopy, and both parasites are resistant to high concentrations of ricin (our unpublished data). In contrast, Jacob, which is the first amebic glycoprotein identified that contains Gal or GalNAc (29, 43), is accessible on the surface of encysting parasites, so that ricin binds to E. invadens cysts and E. histolytica trophozoites phagocytose cysts in a galactose-inhibitable manner.

The E. invadens cyst wall is more like the insect peritrophic matrix than the walls of Giardia cysts or fungi.

Like the peritrophic matrix that lines the food bolus in the insect gut, the E. invadens cyst wall is composed of chitin and a lectin (peritrophin and Jacob, respectively), which has five putative chitin-binding domains (17, 39). The E. invadens cyst walls and peritrophic membranes have a similar thickness and appearance by TEM, and strong detergents are necessary to disrupt both structures. In contrast, the Giardia cyst wall contains polymers of GalNAc rather than GlcNAc, and the abundant Leu-rich proteins of the Giardia cyst walls (CWP1 and CWP2) show no similarity in structure to Jacob or peritrophins (27, 30). Like Giardia, the amebic cyst wall is synthesized simultaneously from numerous loci across the surface of parasites, while cyst walls of budding yeast or elongating fungal hyphae are secreted from particular loci (6, 18, 26). While chitin is a primary structural component of the amebic cyst wall and peritrophic matrices, it is often used to shape fungal walls, which have a complex architecture and composition (2, 5, 6). Future studies will attempt to identify other cyst wall proteins and to determine whether anti-Jacob antibodies may be used to discriminate cysts of E. histolytica and E. dispar (49, 51).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Supplement to Promote Reentry into Biomedical and Behavioral Research Careers (M.F.) and by National Institutes of Health grants AI-33492 (J.S.), GM-31318 (P.R.), and HL-330099 and HL-43510 to R.R.

We acknowledge the expert technical support of Jean Lai of the Harvard School of Public Health for confocal microscopy and image analysis and Maria Ericsson of the Harvard Medical School for TEM and immuno-EM. Thanks to William Lane of the Microchemistry Facility at the Biological Laboratories of Harvard University for sequencing N-terminal peptides. Thanks to of Daniel Eichinger of New York University Medical School for the E. invadens IP-1 strain DNA gDNA library. Thanks to Barbara Mann and Bill Petri of the University of Virginia Medical School for purified E. histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin and rabbit anti-lectin antibodies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arroyo-Begovich A, Carbez-Trejo A. Location of chitin in the cyst wall of Entamoeba invadens with the colloidal gold tracers. J Parasitol. 1982;68:253–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avron B, Deutsch R M, Mirelman D. Chitin synthesis inhibitors prevent cyst formation by trophozoites. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1982;108:815–821. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)90902-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beintema J J. Structural features of plant chitinases and chitin-binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 1994;350:159–163. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulawa C E. Genetics and molecular biology of chitin synthesis in fungi. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;43:505–534. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.002445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaffin W L, Lopez-Ribot J L, Casanova M, Golzabo D, Martinez J P. Cell wall and secreted proteins of Candida albicans: identification, function, and expression. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:130–180. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.130-180.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chayen A, Avron B, Mirelman D. Changes in cell surface proteins and glycoproteins during encystation of Entamoeba invadens. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1985;15:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(85)90030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho J, Eichinger D. Crithidia fasciculata induces encystation of Entamoeba invadens in a galactose-dependent manner. J Protozool. 1998;84:705–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coppi A, Eichinger D. Regulation of Entamoeba invadens encystation and gene expression with galactose and N-acetylglucosamine. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;102:67–77. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das S, Gillin F D. Chitin synthase in encysting Entamoeba invadens. Biochem J. 1991;280:641–647. doi: 10.1042/bj2800641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de la Vega H, Specht C A, Semino C E, Robbins P W, Eichinger D, Caplivski D, Ghosh S K, Samuelson J. Cloning and expression of Entamoeba chitinases. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;85:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02817-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diamond L S, Clark C G. A redescription of Entamoeba histolytica Schaudinn, 1903 (emended Walker, 1911), separating it from Entamoeba dispar Brumpt, 1925. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1993;40:340–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1993.tb04926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dodson J M, Lenkowski P W, Jr, Eubanks A C, Jackson T F, Napodano J, Lyerly D M, Lockhart L A, Mann B J, Petri W A., Jr Infection and immunity mediated by the carbohydrate recognition domain of the Entamoeba histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:460–466. doi: 10.1086/314610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doolittle R F. Convergent evolution: the need to be explicit. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:15–18. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eichinger D. Encystation of Entamoeba parasites. Bioessays. 1977;19:633–639. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenberg D, Schwarz E, Komaromy M, Wall R. Analysis of membrane and surface protein sequences with the hydrophobic moment plot. J Mol Biol. 1984;179:125–142. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elvin C M, Vuocolo T, Pearson R D, East I J, Riding G A, Eisemann C H, Tellam R L. Characterization of a major peritrophic membrane protein, peritrophin-44, from the larvae of Lucilia cuprina. cDNA and deduced amino acid sequences. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8925–8935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erlandsen S L, Macechko P T, van Keulen H, Jarroll E L. Formation of the Giardia cyst wall: studies on extracellular assembly using immunogold labeling and high resolution field emission SEM. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1996;43:416–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1996.tb05053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosh S K, Field J, Frisardi M, Rosenthal B, Mai Z, Rogers R, Samuelson J. Chitinase secretion by encysting Entamoeba invadens and transfected E. histolytica trophozoites: localization of secretory vesicles, ER, and Golgi apparatus. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3073–3081. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.3073-3081.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh S K, Samuelson J. Involvement of p21racA, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, and vacuolar ATPase in phagocytosis of bacteria and erythrocytes by Entamoeba histolytica: suggestive evidence for coincidental evolution of amebic invasiveness. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4243–4249. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4243-4249.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kornfeld K, Kornfeld S. Assembly of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:631–664. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar A, Shen P S, Descoteaux S, Bailey G, Samuelson J. Cloning and expression of an NADP+-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase gene of Entamoeba histolytica. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10188–10192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuranda M J, Robbins P W. Chitinase is required for cell separation during growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19758–19767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee C C, Wu X, Gibbs R A, Cook R G, Muzny D M, Caskey C T. Generation of cDNA probes directed by amino acid sequence: cloning of urate oxidase. Science. 1988;239:1288–1291. doi: 10.1126/science.3344434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leippe M. Amoebapores. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:178–183. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipke P N, Ovalle R. Cell wall architecture in yeast: new structures and new challenges. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3735–3740. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3735-3740.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lujan H D, Mowatt M R, Nash T E. Mechanisms of Giardia lamblia differentiation into cysts. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:294–304. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.294-304.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mai Z, Samuelson J. A new gene family (ariel) encodes asparagine-rich Entamoeba histolytica antigens, which resemble the vaccine candidate serine-rich E. histolytica protein. Infect Immun. 1998;66:353–355. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.353-355.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mann B J, Torian B E, Vedvick T S, Petri W A., Jr Sequence of a cysteine-rich galactose-specific lectin of Entamoeba histolytica. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3248–3252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manning P, Erlandsen S L, Jarroll E L. Carbohydrate and amino acid analyses of Giardia muris cysts. J Protozool. 1992;39:290–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1992.tb01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCoy J J, Mann B J, Vedvick T S, Petri W A., Jr Sequence analysis of genes encoding the light subunit of the Entamoeba histolytica galactose-specific adhesin. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61:325–328. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90079-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nash H M, Lu R, Lane W S, Verdine G L. The critical active-site amine of the human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase, hOgg1: direct identification, ablation and chemical reconstitution. Chem Biol. 1997;4:693–702. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nash T E. Antigenic variation in Giardia lamblia and the host's immune response. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 1997;352:1369–1375. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nielsen H, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Machine learning approaches for the prediction of signal peptides and other protein sorting signals. Protein Eng. 1999;12:3–9. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Farrell P Z, Goodman H M, O'Farrell P H. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of basic as well as acidic proteins. Cell. 1977;12:1133–1141. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petri W A, Jr, Chapman M D, Snodgrass T, Mann B J, Broman J, Ravdin J I. Subunit structure of the galactose and N-acetyl-d-galactosamine-inhibitable adherence lectin of Entamoeba histolytica. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3007–3012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravdin J I. Amebiasis. State-of-the-art clinical article. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1453–1464. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.6.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanchez L, Enea V, Eichinger D. Identification of a developmentally regulated transcript expressed during encystation of Entamoeba invadens. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;67:125–35. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen Z, Jacobs-Lorena M. Evolution of chitin-binding proteins in invertebrates. J Mol Evol. 1999;48:341–347. doi: 10.1007/pl00006478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silberman J D, Clark C G, Diamond L S, Sogin M L. Phylogeny of the genera Entamoeba and Endolimax as deduced from small-subunit ribosomal RNA sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:1740–1751. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanley S L, Jr, Becker A, Kunz-Jenkins C, Foster L, Li E. Cloning and expression of a membrane antigen of Entamoeba histolytica possessing multiple tandem repeats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4976–4980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stanley S L, Jr, Huizenga H, Li E. Isolation and partial characterization of a surface glucoconjugate of Entamoeba histolytica. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;50:127–138. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90250-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stanley S L, Jr, Tian K, Koester J P, Li E. The serine-rich Entamoeba histolytica protein is a phosphorylated membrane protein containing O-linked terminal N-acetylglucosamine residues. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4121–4126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.4121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tannich E, Ebert F, Horstmann R D. Primary structure of the 170-kDa surface lectin of pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1849–1853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valdivia R H, Hromockyj A E, Monack D, Ramakrishnan L, Falkow S. Applications for green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the study of host-pathogen interactions. Gene. 1996;173:47–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venegas A, Goldstein J C, Beauregard K, Oles A, Abdulhayoglu N, Fuhrman J A. Expression of recombinant microfilarial chitinase and analysis of domain function. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;78:149–59. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02620-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Villagomez-Castro J C, Calvo-Mendez C, Lopez-Romero E. Chitinase activity in encysting Entamoeba invadens and its inhibition by allosamidin. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;52:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90035-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vines R R, Ramakrishnan G, Rogers J B, Lockhart L A, Mann B J, Petri W A., Jr Regulation of adherence and virulence by the Entamoeba histolytica lectin cytoplasmic domain, which contains a beta2 integrin motif. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2069–2079. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walderich B, Burchard G D, Knobloch J, Muller L. Development of monoclonal antibodies specifically recognizing the cyst stage of Entamoeba histolytica. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:347–351. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ward W, Alvarado L, Rawlings N D, Engel J C, Franklin C, McKerrow J H. A primitive enzyme for a primitive cell: the protease required for excystation of Giardia. Cell. 1997;89:437–444. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.WHO/PAHO/UNESCO report. A consultation of experts on amebiasis. Epidemiol Bull Pan Am Health Org. 1997;18:13–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wright C S. Comparison of the refined crystal structures of two wheat germ isolectins. J Mol Biol. 1989;209:475–487. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]