Abstract

Molecular dynamics simulations of membranes and membrane proteins serve as computational microscopes, revealing coordinated events at the membrane interface. As G protein-coupled receptors, ion channels, transporters, and membrane-bound enzymes are important drug targets, understanding their drug binding and action mechanisms in a realistic membrane becomes critical. Advances in materials science and physical chemistry further demand an atomistic understanding of lipid domains and interactions between materials and membranes. Despite a wide range of membrane simulation studies, generating a complex membrane assembly remains challenging. Here, we review the capability of CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder in the context of emerging research demands, as well as the application examples from the CHARMM-GUI user community, including membrane biophysics, membrane protein drug-binding and dynamics, protein–lipid interactions, and nano-bio interface. We also provide our perspective on future Membrane Builder development.

1. Introduction

Membrane bilayers serve as the matrix to define cell boundaries and anchor biomachineries and signaling pathways.1 Since the first all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of lipid membranes and membrane proteins in the late 1980s and early 1990s,2−6 membrane simulations have played important roles in exploring membrane-related biological processes.7−12 To name a few, examples include from cholesterol partition in the liquid-order/liquid-disordered phase to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) lipid conformation in Gram-negative bacteria,13,14 from polyethylenimine gene transfection in a wet lab to lipid nanoparticle (LNP) drug delivery in a patient’s body,15,16 from antimicrobial peptide-membrane interactions in nature to amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease,17,18 and from dopamine transporter drug inhibition to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein recognition.19,20 A wide range of membrane simulations assist interpretation of virus infection, bacterial defense, disease onset, and drug toxicity, to name just a few.18,19,21,22

Accompanying the advance of membrane simulations is the development of experimental techniques to study membrane lateral organizations,23−25 the arrival of the single-particle cryo-EM era to reveal thousands of membrane protein structures,26,27 and the maturing of simulation force fields (FFs) and membrane system modeling protocols,28−30 as well as the shifting focus on membrane proteins as the drug targets.31 The recent revolution of structure-predicting tools such as AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold further adds to the modeling arsenal expanding the scope of protein targets for MD simulations.32,33 In the pharmaceutical industry, drug discovery is more than ever “structurally enabled”, meaning structure-based pharmacology discovery with computer-aided drug discovery (CADD) techniques including docking and free energy calculations.34

The CHARMM-GUI cyberinfrastructure is a web-based graphical user interface (GUI) for modeling proteins, glycoconjugates, lipids, ligands, and materials, preparing complex simulation assemblies, and generating the input files for running simulation productions (using Amber, CHARMM, Desmond, GENESIS, GROMACS, LAMMPS, NAMD, OpenMM, and TINKER).35,36Membrane Builder is one of the central pillars in CHARMM-GUI and is heavily used in membrane simulation studies. It first started with support for three phospholipids in 2007.37 With continuous development, it now covers more than 670 different lipid or surfactant types in various FFs including CHARMM, Amber, OLPS, Slipids, Drude, Martini, and PACE CG (see Figure 1).28,38,39Membrane Builder supports all-atom planar bilayer and micelle generation, while CHARMM-GUI Martini Maker supports both coarse-grained micelle and vesicle generation. Both Membrane Builder and Martini Maker support nanodisc generation. Membrane Builder is supported by other functions in CHARMM-GUI such as modeling ligands, glycans, LPS, polymers, nanomaterials, calculating ligand-binding free energy, setting up high-throughput protein–ligand simulations, and applying enhanced sampling techniques.40−48 These supporting modules enable the modeling of realistic membrane systems for studying the nano-bio interface, biomembrane surface, and drug discovery.

Figure 1.

Chronicle of CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder development. From the pioneering stage in 2007 to the recent mature stage, the complexity of model membrane systems and supported resolution, and force fields (FFs, in shaded boxes) have expanded. (Year 2007) A basic simulation system of transmembrane dimer ζ-ζ protein in a DMPC bilayer. Adapted with permission from ref (37). Copyright 2007 PLOS. (Year 2013) A micelle complex of a KcsA K+ channel. Adapted with permission from ref (60). Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society. (Year 2014) An Escherichia coli (E. coli) inner membrane model. Adapted with permission from ref (61). Copyright 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. (Years 2015–2017) An HMMM model consisting of truncated lipids and organic solvent in the hydrophobic core. Adapted with permission from ref (62). Copyright 2015 Biophysical Society. A Martini model of mechanosensitive channel of large conductance in a DOPC bilayer. Adapted with permission from ref (63). Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. (Year 2019) Glycolipids modeling with protein BtuB in E. coli outer membrane. Adapted with permission from ref (38). Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. A nanodisc model of POPC with a GPCR protein. Adapted with permission from ref (64). Copyright 2019 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. (Year 2020) Support of the Amber FFs. (Year 2021) Support of the OPLS and Slipids FFs. An LNP membrane composed of PEGylated diacylglycerol lipid, DSPC, DLin-MC3-DMA, and cholesterol. Adapted with permission from ref (16). Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society. Abbreviations: 1,2-dimyristoyl-phosphatidylcholine (DMPC), 1,2-dioleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (DOPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphocholine (POPC), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC), dilinoleylmethyl-4-dimethylaminobutyrate (Dlin-MC3-DMA).

Recently, a realistic mammalian plasma membrane model composed of ∼200,000 lipids with 63 different types in a box of ∼71 × 71 × 11 nm3 was built and simulated for over 40 μs, pushing the boundary of cell-scale simulations.49 Manually generating large and complex membrane models is time-consuming, prone to errors, and practically impossible. Significant efforts have been made to develop membrane modeling tools by systematically automatizing the workflow. Besides CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder, other membrane building tools include INSANE,50 Packmol,51 MembraneEditor,52 BUMpy,53 LipidWrapper,54 and TS2CG,55 to name just a few. INSANE supports generating a coarse-grained (CG) planar bilayer. Packmol and MembraneEditor support membrane system building with planar, spherical, elliptic, and cylindrical shapes, and MembraneEditor also supports multilayered planar and vesicular membranes. BUMpy supports various shapes of membranes, including torus, semisphere plane, and buckle. LipidWrapper and TS2CG can generate general curved membranes (of arbitrary shapes) by mapping segments of pre-equilibrated membrane or lipids onto triangular surfaces, respectively. AutoPack/cellPack can model membrane-including large-scale cellular environments.56−58 Nanodisc-Builder can generate nanodisc structures.59

In this Review, given the increasing demands for membrane simulations and the growing CHARMM-GUI functionalities, we review the capability of Membrane Builder and the innovative applications in the CHARMM-GUI user community. Based on ∼1,600 papers (based on the Web of Science as of September 2022) that cited or used CHARMM-GUI for membrane simulations, we summarize the applications in the following categories: membrane biophysics, membrane protein dynamics, protein–lipid interactions, drug-membrane interactions, and nano-bio interface. We also included some studies that did not use CHARMM-GUI, as they are vivid examples for demonstrating the power of membrane simulations. At the end of this review, we also discuss the future development of Membrane Builder, which includes support for bicelle, all-atom vesicle, and multiple copies of components (e.g., membrane proteins, ligands, and even membranes) at desired positions, additional membrane morphologies, nano-bio interfaces, and QM/MM simulations.

2. Supported Membrane Systems

Membrane Builder supports the generation of all-atom models of planar monolayer and bilayer membrane, inverse hexagonal phase, micelle, and nanodisc systems (Figure 1). The corresponding CG Martini membranes30,65 generated by Martini Maker in CHARMM-GUI support vesicle generation as well.66 The generated CG models can be conveniently converted into all-atom models by All-atom Converter in Martini Maker. In addition, Membrane Builder supports the generation of the highly mobile membrane mimetic (HMMM) model,67 where the lipid hydrophobic tails are truncated and replaced with short hydrocarbons, making the truncated lipids highly mobile.

For a chosen membrane system, Membrane Builder provides inputs for various MD engines68 with compatible FFs including CHARMM, Amber, OPLS, Slipid, and Drude.69,70 This is one of the unique merits over other tools that usually provide either an initial structure model or inputs for a specific MD engine only. The inputs provided by Membrane Builder can be easily modified for user specific purposes. Another important merit of Membrane Builder is seamless integration with other modules in CHARMM-GUI. For example, PDB Reader& Manipulator,36,42,71Glycolipid Modeler, and LPS Modeler(38) are called by Membrane Builder to include peptides, proteins, small molecules, glycolipids, and LPS in a membrane system. Conversely, it can be called by other modules, e.g., a recent study used Enhanced Sampler utilizing Membrane Builder in generation of inputs for adaptive bias force simulation of Mla protein in a bacterial membrane.47 Hence, using Membrane Builder, one can easily prepare a wide variety of realistic membranes, including components like membrane proteins, nucleic acids, glycoconjugates, drug molecules, and nanoparticles, while adding advanced simulation techniques including steered MD simulation and umbrella sampling.

Here, we provide an overview of the workflow for building membrane systems supported in Membrane Builder as well as for CG vesicles in Martini Maker (Figure 1). We start with a brief description of the general workflow for building a bilayer, which is applicable to all membrane systems. Then, we outline the unique features for each membrane system. The general workflow involves five steps, originally designed for planar bilayers. In STEP 1, a protein (or protein complex) structure is read in through PDB Reader& Manipulator that handles user-specific modifications including protonation states, mutations, post-translational modifications, and disulfide bonds. PDB Reader& Manipulator can also handle structures for other types of molecules, such as small ligands, DNA, and RNA. In STEP 2, the orientation of the protein can be adjusted based on user input. In STEP 3, the system size is determined, and lipid-like pseudoatoms are distributed on the membrane surface(s) to assign lipid headgroup positions. In STEP 4, the system components (lipids, solvent, and ions) are generated, and pseudoatoms are replaced by lipids using the replacement method5,72 from the lipid conformation library for most lipid types or with on-the-fly generated lipids for some lipid types (see section 3Supported Lipid Types). In this stage, the penetration of lipid tails to ring structures in sterols, aromatic side chains, and carbohydrates as well as protein surfaces is checked and remedied if necessary. In STEP 5, the components (protein, membrane, solvent, and ions) are assembled, and the topology and inputs for equilibration (STEP6) and production (STEP7) simulations are generated. For membrane-only systems, the workflow starts from STEP 3.

While the general workflow is common for all supported membrane systems, there are unique features depending on their geometry and types. The planar membrane area (X and Y) is determined based on the cross-sectional protein area (along the membrane normal, Z-axis) and the area per lipid (from the default or user-specified value). In a monolayer generation, an assembled bilayer is converted to a monolayer system by shifting a half unit cell along the Z-axis (with periodic boundary conditions) followed by increasing the Z box size to create hydrophobic tail-air interfaces. In HMMM generation, full-length lipids in an assembled bilayer are truncated (with three to five remaining acyl carbons),67 and the empty space in the hydrophobic core is filled with pre-equilibrated organic solvents (currently 1,1-dicholroethane).62 In nanodisc generation, prior to STEP 3, a diameter of circular membrane scaffold protein (MSP) dimer (from 81 to 121 Å) needs to be chosen among 12 supported MSP sequences, and the bilayer region is defined as the area enclosed by the MSP dimer.64 In micelle generation, the initial geometry is defined as a torus formed by a hemisphere of radius rm, whose curvature center is shifted by rp along the lateral dimensions from the Z-axis, where rm and rp are the radii of the micelle and the protein, respectively. Pseudoatoms are distributed on the surface of the torus and replaced by detergents.60 In the generation of a CG vesicle by Martini Maker, unlike other tools such as Packmol, MembraneEditor, and BUMpy, exchange of lipids between the inner and outer leaflets as well as that of interior and exterior water molecules is allowed by creating pores in the vesicle.63 The generated initial vesicle structure (STEP 5) is then subject to equilibration (STEP 6) with gradually decreasing pore radii to obtain the vesicle with closed surfaces for the production run (STEP 7). The conversion of a CG vesicle to an all-atom model is supported by Martini Maker. In the generation of an inverse hexagonal phase, lipids are packed around a central water cylinder of radius R, and short hydrocarbons are added to fill the interstitial space in a hexagonal simulation box (along the XY-dimensions).

Asymmetric bilayer systems (planar bilayer and vesicle) can exhibit a mismatch in the surface area between the upper and lower leaflets during simulations, especially when lipid areas are obtained from homogeneous bilayer simulations. To avoid this, the area of each lipid types from the cognate symmetric bilayers can be used.49,73 For further discussion of this topic, refer to subsection 4.5Methods for Generating Asymmetric Bilayers.

3. Supported Lipid Types

Membrane Builder offers a wide range of supported lipid types, including those found in biological and synthetic membranes and various membrane-like environments.38 Here, we review the supported lipid types in biological membranes, detergent micelles, and LNP membranes, including those from plasma, yeast, bacterial, archaeal, and plant membranes, as well as ionizable and PEGylated lipids (PEG-lipids) for LNP membranes.74

Lipids in biological membranes can be roughly divided into two categories: bilayer-forming and nonbilayer-forming. The former includes phospholipids, while the latter includes sterols diacylglyceride, triacylglyceride, monogalactosyldiacylglycerol, quinones, and squalene.75 Triacylglycerols consist of three fatty acid chains linked to the glycerol backbone (Figure 2). All membrane lipids share a common structure consisting of a headgroup, backbone, and tails (Figure 2). Headgroups are generally short and polar moieties, while tails are saturated or unsaturated fatty acid chains. Backbones are typically derived from glycerol, sphingosine, or sterol. Therefore, biological membranes are composed of various lipid types whose compositions can vary significantly depending on their origins and environments.76,77 In addition, fatty acids, lipidated amino acids, and glycopeptides can also be found in membranes.

Figure 2.

Lipid collection in CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder spans from biomembrane bilayer-forming lipids to nonbilayer forming lipids, detergents for protein sample preparation, and PEG-lipids in LNP membranes for genetic drug delivery. Abbreviations: phosphatidic acid (PA), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), diacylglyceride (DAG), triacylglyceride (TAG), ubiquinone (UQ), 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), tandem triazine-based maltosides with ethylenediamine linker (TZM-E9), dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM), PEGylated myristoyl diglyceride (PEG-DMG).

The distribution of lipids is usually heterogeneous along both the lateral and trans-bilayer dimensions. In plasma membranes, saturated lipids, sphingomyelin, and glycolipids (gangliosides) are major components in the outer (exoplasmic) leaflet, whereas unsaturated lipids and negatively charged lipids (phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidic acid (PA), phosphatidylinositol (PI), and phosphatidylinositol phosphate (PIP)) are more abundant in the inner (cytoplasmic) leaflet. Cardiolipins are composed of two phosphatidyl lipids linked to the glycerol backbone and are abundant in the inner leaflet of mitochondrial membranes. In certain bacterial species, membranes can have unique lipids with branched tails78,79 and/or those with a cyclopropane moiety.80,81 In particular, the outer leaflet of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria contains LPS where a polysaccharide chain is linked to lipid A with a varying number of tails.82−84 Archaeal membranes are composed of unique lipids with phytanyl tails and quinone derivatives with various lengths of isoprenoid chains.85

In addition to lipids, detergents have also been frequently used in simulations as they dissolve the membrane peptide/protein and form protein-detergent complexes, where a micelle-like detergent belt surrounds the protein transmembrane domain. Conventional detergents with a single tail and headgroup are highly dynamic, resulting in poor stability of the protein-detergent complex. Extensive efforts have been made to improve the stability of the protein-detergent complex, and a few lipidated monosaccharides (n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM), n-decyl-β-d-maltoside, and n-octyl-β-d-glucoside) and recently developed flexible core bearing detergents (GTMs) and foldable triazine-based maltosides (TZMs) have been shown to be more effective (Figure 2).86−89Membrane Builder currently supports over 130 different detergents, including these novel GTMs and TZMs.

Another set of important lipid types in LNPs for genetic drug delivery is ionizable (cationic) lipids and PEG-lipids (Figure 2).90−92 The drug delivery efficacy depends on both the ionizable lipids and PEG-lipids, where the PEG-lipids act as helper lipids along with cholesterols (CHOLs) and phospholipids to stabilize LNPs before uptake into the cytoplasm.91 When LNPs arrive at the target cells, the PEG chains need to be detached for efficient endocytosis.93,94 After uptake into the endosome, the endosomal membrane is disrupted by the formation of a nonbilayer structure with anionic lipids (endosomal membrane) and cationic lipids (LNP) at low pH, which drives the release of genetic drugs.90 Currently, Membrane Builder supports six ionizable lipid types (with neutral and cationic forms) with five lipid tails. For PEG-lipids, two backbones, phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and diacylglycerol, are supported with 50 lipid tails and user-specified PEG chain lengths.

In Membrane Builder, the initial conformations of various lipids, fatty acids, N-acylated amino acids, detergents, ionizable lipids, and PEG-lipids are chosen from the lipid library and/or generated on-the-fly from user-specified sequences. While the conformations of most predefined lipids, fatty acids, detergents, and ionizable lipids are available in the lipid library, glycolipids, LPS, N-acetylated amino acids, and PEG-lipids need to be generated for each user-specified sequence. In on-the-fly generation of glycolipid and LPS, Glycolipid Modeler and LPS Modeler in CHARMM-GUI are incorporated because it is not practical to prepare a lipid library for all possible combinations of glycan sequences, core oligosaccharide and O-antigen units, and lipid A from various Gram-negative bacteria, given the combinatorial explosion.38 An analogous workflow is used in generation of N-acetylated amino acids35 and PEG-lipids16 due to a similar reason.

4. Membrane Biophysics

Here, we review the MD simulation applications for membrane biophysics, including membrane domain formations, lipid–lipid interactions, LNP membranes, synaptic vesicle fusion, and the methods for generating asymmetric membrane simulations.

4.1. Membrane Domains

In the current consensus definition, rafts are heterogeneous and dynamic nanodomains (10–200 nm) enriched in sterols, sphingolipids, and certain types of proteins that compartmentalize cellular processes.95 Larger raft domains can form through protein–protein and protein–lipid interactions.96,97 Although the definition does not explicitly imply lipid-driven domain formation, in model membranes composed of saturated and unsaturated lipids with CHOL, liquid-ordered (Lo) and liquid-disordered (Ld) domains can coexist.98−102 These ternary and quaternary models show rich phase behaviors such as critical fluctuations, modulated phases, and a macroscopic phase separation. Similar phase behaviors are also observed in cell-derived membranes,103,104 suggesting that these model membranes possibly reflect the characteristics of biological membranes.

Accordingly, a large number of computational studies have investigated lipid domains using ternary or quaternary mixture models.105−113 So far, spontaneous domain formation has been observed only in CG simulations due to slow phase separation kinetics, although a domain formation onset has recently been observed in all-atom simulations.107,109 While all-atom simulations are still challenging for spontaneous domain formation, the detailed molecular structure of Lo domains has been identified in recent simulations:114−116 Regions of hexagonally packed saturated lipids are surrounded by unsaturated lipids and CHOLs (Figure 3A), which is later supported by DEER and electron diffraction experiments.117,118 Hence, it is conceivable that small molecule permeation or membrane protein partitioning in rafts occurs in the regions enriched in unsaturated lipids and CHOLs. Indeed, in a recent simulation study, it was observed that permeation of oxygen and water occurs along the relatively disordered regions in Lo phases.119

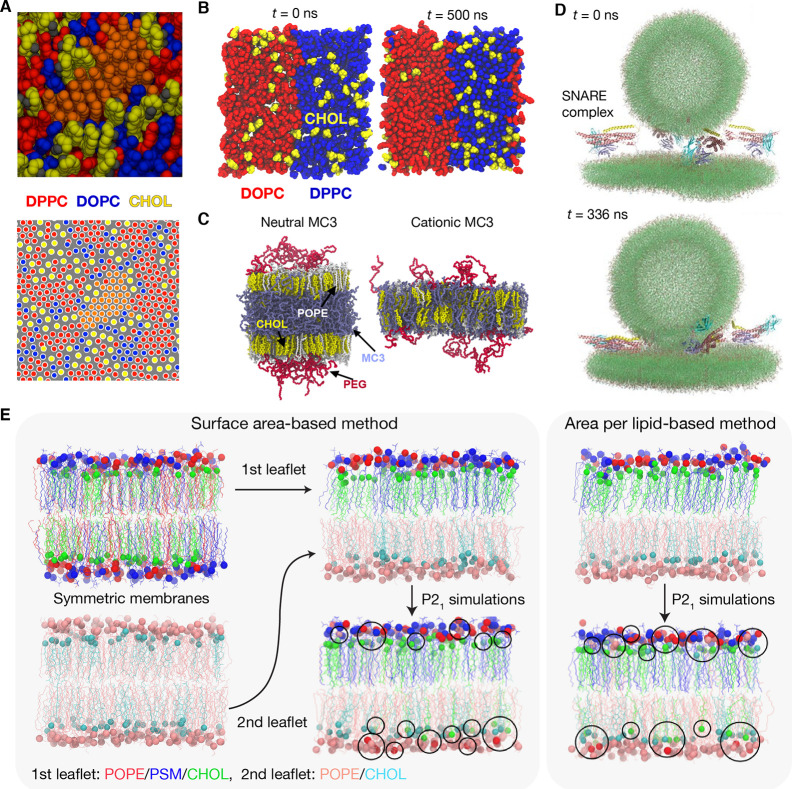

Figure 3.

(A) Snapshots of the substructure in Lo domain in a mixed bilayer of DPPC, DOPC, and CHOL (top) and the center of mass of lipid tails (bottom). An area of locally hexagonal order surrounded by CHOL and DOPC is shown in orange. Adapted with permission from ref (116). Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society. (B) CHOL partitioning between a binary bilayer composed of laterally attached DOPC and DPPC bilayers. Randomly distributed CHOLs at t = 0 ns (left) mostly partitioned into DPPC bilayer at t = 500 ns (right). (C) Effects of charge states of the ionizable MC3 lipid on the LNP membrane structure. Neutral MC3 accumulated into the hydrophobic core of the membrane (left), while the positively charged MC3 headgroup remained at the membrane-water interface (right). Adapted with permission from ref (16). Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society. (D) Snapshots of the all-atom simulation of the primed SNARE complex bridging a vesicle and a flat bilayer: initial configuration at t = 0 ns (top) and snapshot at t = 336 ns showing a probable primed state (bottom). Adapted with permission from ref (134). Copyright 2022 eLife. (E) Methods for generating asymmetric bilayers: leaflet surface area matching method (SA), area per lipid-based method (APL), and partial chemical potential matching (P21) method combined with SA and APL (left and right panels, respectively). During P21 simulations, POPE and CHOL are allowed to migrate between the leaflets (shown in black circles).

4.2. Lipid–Lipid Interactions

In lipid-driven domain formation, the preference of CHOL for certain lipid types plays an important role, e.g., the preference for sphingomyelin over phospholipids.120 CHOL-lipid interactions can be quantified in CHOL exchange experiments between β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) and vesicles with different compositions. β-CD is used as a reference state,121−124 which elegantly resolves the known issues in direct CHOL exchange between vesicles.125−127 In computational simulations, CHOL-lipid interactions have been quantitatively characterized by calculating transfer free energies from bilayer to water128,129 or to β-CD,130,131 though both are computationally intensive. Recently, an efficient alternative approach, a binary bilayer simulation, has been proposed, where two bilayers are laterally attached, and their interfaces are maintained by soft restraining potentials acting only on selected lipids that diffuse deeply from one bilayer to the other bilayer.13 In such a setting, as shown in Figure 3B, CHOL (with no imposed restraints) can freely diffuse across bilayers and partition between them without the need of a reference state like β-CD. The binary bilayers can be prepared using slightly modified inputs from Membrane Builder, and their efficacy in direct CHOL partitioning simulations was demonstrated by excellent agreement between partition coefficients from simulations and experiments.13

4.3. Lipid Nanoparticle Membranes

Recent updates in Membrane Builder allow for preparing simulations of realistic LNP membranes composed of ionizable (cationic) lipids and helper lipids such as phospholipids, CHOL, and PEG-lipids.16 Previously, a few simulation studies have investigated LNP membranes without CHOL and PEG-lipids,132,133 where neutral ionizable lipids segregate into the hydrophobic core of the LNP bilayer, while the cationic headgroups remain at the membrane-water interfaces. This charge-state dependent segregation of ionizable lipids in the bilayer was also observed in more realistic LNP membranes that include CHOL and PEG-lipids (Figure 3C).16 More importantly, interactions between PEG oxygen atoms and the charged headgroups of ionizable lipids (at low pH) induce negative curvature due to their attractive interactions, whose extent differs between different ionizable lipids. This is reflected in different exposure of the PEG-lipid linkage among different ionizable lipid types, suggesting that interactions between ionizable cationic lipids and PEG can be optimized for optimal drug delivery.

4.4. Synaptic Vesicle Fusion

The Ca2+-triggered release of neurotransmitters from a synaptic vesicle is key for communication between neurons. At the initial stage, the vesicles are tethered to the plasma membrane through SNARE complex-mediated docking135 and then undergo priming processes136 for fast fusion upon Ca2+ influx induced by an action potential,137 which is sensed by synaptotagmin-1 (Syt1).138 Tightly bound complexin-1 to the SNARE complex promotes the formation of a primed state and inhibits premature fusion.139,140 Although continuum and CG models provide insight into SNARE-mediated fusion,141−145 the primed states have not been modeled and simulated until recently. In the simulation of the first all-atom model of a synaptic vesicle in a primed state, it was observed that trans-SNARE complexes bridge the synaptic vesicle and planar bilayer membrane with fragments of Syt1 and/or complexin-1 (Figure 3D).134 The vesicle was prepared using modified scripts for building CG vesicles from Martini Maker. The simulations provide new insight that extensive interactions of the C2B domain of Syt1 with the planar membrane and a spring-loaded configuration of complexin-1 prevent premature fusion but keep the system ready for fast fusion upon Ca2+ influx.

4.5. Methods for Generating Asymmetric Bilayers

Current methods for generating bilayer simulations are based on assumptions appropriate for symmetric bilayers, which include individual area per lipid (APL)-based, leaflet surface area matching (SA)-based, and zero leaflet tension (0-DS)-based methods. Figure 3E shows the APL- and SA-based methods. In asymmetric bilayers, the assumptions may not be applicable, for example, when an asymmetric bilayer has a nonzero spontaneous curvature due to asymmetry in bending moduli and associated spontaneous curvatures of each leaflet. Thus, methods for generating initial conditions for realistic asymmetric membrane simulations remain to be established. In a recent study, another generation method was proposed, which aims to achieve a partial chemical potential equilibrium between the upper and lower leaflets by interleaflet exchange of selected lipids via P21 periodic boundary conditions, without altering the bilayer’s spontaneous curvature.39 This approach results in better agreement in mechanical properties between asymmetric bilayers generated by APL-, SA-, and 0-DS-based approaches, in which changes are the smallest for bilayers from the SA-based method. Based on this, the SA/P21-based or SA-based (when the differential tension is small) approach is recommended as a practical method for generating the initial conditions for asymmetric bilayer simulations.

5. Membrane Protein Simulations

The Concise Guide to Pharmacology 2021/22, a biennial collection by The British Journal of Pharmacology, summarizes ∼1,900 important drug targets and their pharmacology.31 The collection focuses on six major pharmacological targets including (i) G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), (ii) ion channels, (iii) nuclear hormone receptors, (iv) catalytic receptors, (v) enzymes, and vi) transporters. In the following sections, we discuss computational studies on GPCRs, ion channels, and transporters since they are typical membrane proteins and the research of these proteins benefits greatly from CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder. In addition, we devote a subsection on viruses, due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic and an exploding number of publications on virus study.146,147

5.1. G Protein-Coupled Receptors

GPCRs mediate cell responses to small molecules, neurotransmitters, and hormones, laying the basis for vision, olfaction, and taste.148 GPCRs share a seven α-helical transmembrane (TM) structure template, and in vertebrates, they are categorized into five families: rhodopsin (class A), secretin (class B), glutamate (class C), adhesion, and Frizzled/Taste2.148 The GPCR’s ability to interact with G proteins and secondary messengers and to initiate the downstream signaling pathways makes it multifaceted in functions and important in the central nervous system.149

GPCRs play a vital role in relaying information from neurotransmitters and hormone by transmitting the binding of these molecules from the extracellular side to signals on the intracellular side via binding with cellular transducers such as G protein or β-arrestin. MD simulations have been extensively used to study GPCR interactions with signaling molecules150−155 as well as transducers in the cytosolic side.156−158 For example, Park et al. recently studied the neuropeptide Y and Y1 receptor,152 which is enriched in the brain and responsible for neurological processes such as food intake, anxiety, obesity, and cancer.159,160 The cryo-EM structure shows the binding of neuropeptide Y to Y1 receptor, and MD simulations further reveal the stability and dynamics of the neuropeptide Y binding, providing a conformational ensemble of binding interactions (Figure 4A). Other studies have examined the GPCR-G protein binding and tried to derive a rationale for signaling through different G proteins or β-arrestin.156−158 Zhao et al. studied β2 adrenaline receptors and their differential binding interfaces with Gs, Gi, and β-arrestin 1.158 Since the binding interface is different for each cellular transducer, the conformational rearrangement in the TM domain is also different, allowing signal transduction to happen.

Figure 4.

MD simulations to study membrane protein structure, dynamics, and function. (A) Binding of neuropeptide Y onto the GPCR protein Y1 receptor and its tilt angle time series. Adapted with permission from ref (152). Copyright 2022 Chaehee Park et al. Published by Springer Nature. (B) Pore permeation profile of ligand-gated pentameric glycine receptor wild type versus mutant. Adapted with permission from ref (169). Copyright 2022 Mhashal, Yoluk, and Orellana. Published by Oxford University Press. (C) Different states of the LtaA lipid transporter and lateral opening, which leads to lipid substrate diffusion into the pocket. Adapted with permission from ref (170). Copyright 2022 Elisabeth Lambert et al. Published by Springer Nature. (D) Spike protein of SARS-CoV2 and the hinge dynamics of the membrane-anchored complex. Adapted with permission from ref (19). Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

The cavities on the extracellular and intracellular sides of the GPCR seven α-helical TM bundle are not only interfaces for signaling peptide and transducer binding but also promising drug-binding sites for modulating receptor activity. In combination with structural biology efforts, MD simulations have been used to study drug binding and analyze the induced conformational changes in GPCRs.161−164 Of particular interest is distinguishing the agonist and antagonist of GPCRs, as the conventional ligand docking reveals ligands that bind to the pocket but cannot indicate a ligand to be an agonist, an antagonist, or inversed agonist. Studies by Lee et al.165 and by Shiriaeva et al.166 examined the boundary between agonist and antagonist on A3 and A2A adenosine receptors, respectively, and derived the rationale that antagonists restrict the conformational rearrangement required for activation.

The seven α-helical TM bundle also represents a great example for protein allostery. How ligand or protein binding leads to specific conformational change and how the conformational wave is propagated are interesting topics both from a molecular machine perspective and from a pharmaceutical development purpose. Velazhahan et al. studied how the allosteric transition is passed between the dimer interface of Ste2 through MD simulations.167 Dutta, Selvam, and Shukla examined the allosteric effects on Na+ ion binding to the CB1 receptor using adaptive sampling on Na+ ion binding and Markov state models.168 Therefore, MD simulations greatly extend our understanding of binding of signaling peptide, cellular transducer (G proteins, beta-arrestin), ligands, as well as the allosteric conformational network.

5.2. Ion Channels

Ion channels are the second largest target for available drugs after GPCRs.171 The arrival of new, fast high-throughput screening platforms and hundreds of ion channel structures makes them increasingly promising targets for therapeutic development.172,173 Ion channels are classified into three types according to the International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology/British Pharmacological Society (IUPHAR/BPS) classification: ligand-gated ion channels, voltage-gated ion channels, and other ion channels.174

Ligand-gated ion channels include 5-HT3 receptors, acid-sensing ion channels, epithelial sodium channel, GABAA receptors, glycine receptors, ionotropic glutamate receptors, IP3 receptors, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, P2X receptors, and zinc-activated channels. By convention, these channels are opened or gated by binding of neurotransmitters or endogenous ligands. Voltage-gated ion channels include two-pore channels, cyclic nucleotide-regulated channels (HCN), potassium channels (KCa, KNa, Kir, K2P, KV), ryanodine receptors, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, voltage-gated calcium (CaV), proton (HV1), and sodium (NaV) channels. In addition, other ion channels include aquaporins, chloride channels (ClC, CFTR, CaCC, VRAC, Maxi Cl), connexins, pannexins, piezo channels, and store-operated ion channels (Orai). The boundary between ligand-gated and voltage-gated ion channels is getting blurry due to the discovery of multimodality ion channels such as TRP channels.175 The TRP channels can be modulated by various stimuli such as voltage, osmotic pressure, pH, temperature, and natural compounds.176 This family, alongside with other ion channels, represents an exciting repertoire of targets for biophysical studies and for drug discovery given their roles.177

One of the popular topics in ion channels is the permeation of ion and water through their pores.178−180 MD simulations are commonly employed to study the permeation, providing atomistic insight on top of the typical static pore profile using programs like HOLE2.181 For example, Mhashal et al. used all-atom simulations to study water permeation in the glycine receptor pentameric ion channel.169 Taking advantage of statistical physics, MD simulations can also be used to calculate a permeation free energy profile and thus provide a detailed gating mechanism of ion permeation. The derived energy landscape helps to identify important restriction residues and energy barriers.182−186 Mhashal et al. also studied cancer mutations found in genomic-wide tumor screens.169 MD simulations show that mutation (R252S) leads to wider upper and lower gates than wild type, facilitating ion and water permeation (Figure 4B). Because of the ion channels’ role in the central nervous system and cell metabolism, mutations of ion channels can lead to neurological disease and other diseases such as cancers.169,187−189 Therefore, there is a huge demand to understand how mutations affect channel conformation and ion permeation. Moreover, in the era of precision medicine, personalized structural biology becomes important to understand variants and mutants.190 It is impossible to solve structures of every variant, and thus MD simulations that mutate the original protein and study the conformational dynamics become essential.

Another important aspect about the ion channel is drug binding. MD simulations are used to explore ligand binding stability and to better assess the induced-fit effect from docking results191,192 or to verify the binding poses from structural biology works.193,194 Ligand-binding free energy calculations yield a quantitative profile for comparison with experimental measurements.194 In addition, the dynamical effects exerted by ligands can be accessed from simulation trajectories. Mernea et al. combined terahertz (THz) spectroscopy and MD simulations and showed the binding site of an epithelial sodium channel blocker and reduced channel dynamics upon blocker binding.195 As more efforts poured into ion channel drug discovery from both experimental and computational approaches, the ligand-binding, modulation, mutations, and permeation pathway of ion channels will be further illuminated.

5.3. Transporters

Transporters translocate chemicals across the membrane, which is vital for cell growth and removing toxic substances. Deficiency in transporters can lead to neurodegenerative diseases196 and metabolic disorders.197 Upregulation of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, such as P-glycoprotein, multidrug resistance-associated protein 2, and breast cancer resistance protein, can efflux drugs in cancer cells and develop multidrug resistance.198 In Gram-negative bacteria, a number of transporters, such as the Lpt transporter and the Mla transporter, are deployed to maintain the bacterial outer membrane asymmetry.199,200 Understanding the transporting mechanism and developing drugs to destroy such mechanisms can tackle antibiotic resistance.201

Transporters are generally classified into the four major categories: (i) P-type ATPases, which are multimeric and transport primarily inorganic cations; (ii) F-type or V-type ATPases, which are proton-coupled and serve as transporters or motors; (iii) ABC transporters, which are involved in drug disposition and translocating endogenous solutes; and (iv) the SLC superfamily, a gigantic superfamily of solute carriers with 65 families and around 400 members.202 The SLC superfamily transports a wide variety of solutes, including inorganic ions, amino acids, sugars, and relatively complex organic molecules.202

MD simulations can capture substrate movement in transporters. Lambert et al. used MD simulations to study LtaA, a proton-dependent major facilitator superfamily lipid transporter that is essential for lipoteichoic acid synthesis in the pathogen Staphylococcus aureus.170 In their study, both inward-open and outward-open conformations of the transporter were illustrated by examining the solvent accessibility of the cavities (Figure 4C). Notably, the simulations revealed that the lipid substrate (gentiobiosyl-diacylglycerol) permeates into the lower region of the lateral gate through the lateral opening of the translocation channel. This provides evidence for substrate binding and supports for their “trap-and-flip” hypothesis.

As some transporters are driven by proton and/or Na+ gradients, it becomes important to identify the proton and Na+ binding sites. Raturi et al. studied the binding and disassociation of Na+ in a MATE (multidrug and toxic compound extrusion) transporter by simulating the transporter with Na+ prebound and by letting the Na+ freely diffuse into the sites.203 Zhao et al. similarly studied the Na+ binding in another MATE transporter.204 Bavnho̷j et al., on the other hand, used constant pH simulations to determine the protonation states of sugar transporter protein STP10 and established the basis for proton-to-glucose coupling.205

Free energy calculations add further details to transportation pathway studies.206−209 Prescher et al. studied ABCB4, a human PC lipid floppase, using umbrella sampling along the putative translocation pathways defined by TM1 and TM7 helices, respectively.207 The free energy profiles show that translocation along TM1 has decreased energy barriers, while the pathway along TM7 does not. The study also compared the translocation based on inward-open versus outward-open states along TM1 and found that the outward-open state is favored for the first part of translocation (binding, positioning, initial translocation) and the inward-open state is favored for the energetically most demanding step (translocating across the bilayer center). The lowered energy barrier value is also close to a previously calculated value from rate difference in experimental measurements. Therefore, MD simulations provide a powerful way to further determine the atomistic details and energetic description about transporter functions.

5.4. Viral Proteins

Common viruses, including HIV, SARS-CoV, Ebola, dengue, Zika, and hepatitis B/C/E viruses, have caused pandemics in human history and brought great suffering to millions of people.210−213 One prominent example is the recent COVID-19 pandemic. To accelerate drug development against coronavirus, computational tools, such as molecular docking, MD simulations, and free energy calculations, have been widely employed.147

Viral infection involves contact with and intrusion into host membranes. Viruses generally have a membrane structure to keep the nucleic acids inside the viral vesicle. Consequently, studies have focused on the membrane proteins that mediate cell binding (such as spike protein gp120) and viral membrane proteins (such as matrix protein and envelope protein E).214−216 Choi et al. studied the dynamics of the fully glycosylated full-length spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 anchored in a viral lipid bilayer.19,217 Spike protein is important for host cell entry by binding to ACE2 protein in the host cell membrane. MD simulations reveal the spike protein orientation and dynamics characterized by rigid bodies of different parts (Figure 4D). Full-length glycans were all modeled to reveal the epitopes suitable for antibody binding without being blocked by glycans. In a follow-up study, Cao et al. then examined the binding of the spike protein with six human antibodies, taking glycans into account.218 Kim et al. used steered MD simulations to examine their binding strength between ACE2 and spike protein from COVID-19 variants.219,220

Besides coronavirus, other viruses were also studied in MD simulations. To explore the first step of viral particle fusion with late endosome, Villalaín simulated the dengue virus envelope protein binding to the late endosomal membrane.214 Jacquemard et al. investigated the interaction between HIV gp120 and CCR5 receptor.221 Norris et al. studied M matrix protein assembly in measles and Nipah virus infection and showed how the matrix polymerization process was facilitated by PIP2 lipids.216 The above research topics showcase the importance of membrane protein studies in viruses and provide a dynamic picture of viral proteins, viral matrix assembly, and cell infection.

6. Membrane-Active Peptides/Peripheral Proteins

6.1. Antimicrobial Peptides

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are naturally occurring peptides in the innate immune systems and have broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties against invading microorganisms.222 AMPs also have anticancer, antiviral, antiparasitic, and wound-healing properties that make them attractive for pharmaceutical development.223 The potential mechanisms of membrane disruption by AMPs include the carpet model, barrel-stave model, toroidal pore model, and aggregate model,222 which require detailed atomistic examination of AMPs’ interactions with membrane bilayers.

The majority of the AMP simulations have explored how AMPs influence the membrane bilayer structure. Allsopp et al. studied AMP WLBU2 in the Gram-negative bacterial inner membrane and Gram-positive bacterial membrane in different binding configurations (straight, bend, and inserted).17 In the inserted configuration, WLBU2 induces ion and water permeation across the bilayer, indicated by water densities in Figure 5A. In order to see more dramatic membrane disruption phenomena at a much longer time scale, CG simulations are usually necessary. Miyazaki and Shinoda studied the action of melittin on membranes with a varying peptide-to-lipid (P/L) ratio.224 At a P/L ratio = 1/50, toroidal pore formation was observed, while at a P/L ratio = 1/26, lipid extraction by melittin accompanying pore formation was observed. This highlights the influence of AMP concentrations on its mechanistic action modes and add a further holistic picture to all-atom simulations.

Figure 5.

(A) Antimicrobial peptide WLBU2 penetrates into the Gram-positive bacteria membrane and induces water permeation at the membrane center. Adapted with permission from ref (17). Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society. (B) Anticancer peptide HB3 mut3 (with KK motif replaced by RR) penetrates deeply into the PC/PS mixed membrane. Adapted with permission from ref (225). Copyright 2022 Claudia Herrera-León et al. Published by MDPI. (C) Dimerization of Aβ42 and its interactions with the POPC membrane with different binding configurations shown. Adapted with permission from ref (18). Copyright 2021 National Academy of Sciences. (D) Lipid transport protein Osh4 binding to anionic lipid membrane and the interaction sites revealed by HMMM and all-atom MD simulations. Adapted with permission from ref (230). Copyright 2022 Biophysics Society.

Other MD simulation studies on AMPs aim to understand their selectivity and targeting. MD simulations on anticancer peptides have shown that they preferentially bind to cancer cells due to the exposed PS lipids on the cell surface (Figure 5B).225 Meanwhile, CHOL has been shown to lower the penetration of AMPs into the membrane, partially due to the more ordered membrane environment.226 This lays the foundation for AMPs’ targeting to microbial membranes rather than being toxic to mammalian cells. Lantibiotics, a type of modified peptides, are promising candidates to fight against resistant bacterial strains.227 MD simulations show that they preferentially bind to lipid II, the precursor in the peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway, and induce a water tunnel in the membrane.228

Overall, the research landscape of AMPs requires (i) structural characterizations of the usually short peptide, which does not have an experimental structure, so MD simulations can be used to validate the predicted structure and study the structural change under different environmental conditions including pH;229 (ii) an atomistic or near-atomistic picture of peptide-membrane interactions, and (iii) rationales about peptide targeting and cell selectivity based on cell membrane compositions. All of the above can be studied through Membrane Builder and Martini Maker in CHARMM-GUI.

6.2. Aβ and Protein Aggregates

Mammalian amyloids are highly ordered fibrous cross-β protein aggregates that are implicated in a variety of diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, type 2 diabetes, and prion diseases.231 The Aβ peptide aggregates on the neuronal membrane are linked to Alzheimer’s disease. Fatafta et al. studied Aβ42 dimer in solution and in the presence of a lipid bilayer using MD simulations.18 The results show that Aβ42 peptides attached to the membrane and interacted preferentially with ganglioside GM1 (Figure 5C). Experimentally, Zhang et al. later showed that GM1 promotes early Aβ42 oligomer formation in liposomes and helps to maintain the amyloid structure.232 The authors then mutated the Arg residue responsible for GM1 binding in MD simulations and found much more disassociation of Aβ42 from the membrane.

Apart from the Aβ peptide, α-synuclein (αS) is a synaptic peptide that tends to form aggregates in Parkinson’s disease. Garten el al. studied αS interactions with different membranes and found that branched lipids (DPhPC) promote membrane absorption through shallow lipid-packing defects.233 Human Langerhans islets amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP) is the main amyloid found in patients with type 2 diabetes. Espinosa et al. studied the mechanism underlying promoted hIAPP aggregation in a hydroperoxidized (R-OOH) bilayer.234 The MD simulation results show that the oxidized lipid bilayer increases the helicity of hIAPP and the amyloidogenic core, accelerating the aggregate formation. Protein aggregates, such as Aβ, αS, and hIAPP, have significance in disease cure and pharmaceutical development. Studying their interaction with membrane, as well as how drugs disrupt the aggregate-membrane interactions, will pave the way for drug discovery.235

6.3. Peripheral Membrane Proteins

Peripheral membrane proteins are a class of membrane proteins that attach to the lipid bilayer, in contrast to integral membrane proteins.236 Compared with enriched structural biology data about transmembrane proteins like GPCRs and ion channels, peripheral membrane proteins have not been extensively studied, possibly due to the complexity of the protein–membrane interface.237 The aforementioned protein aggregates like Aβ and αS are also part of the peripheral membrane protein class. In this subsection, we focus on slightly larger peripheral membrane proteins that interact with membranes through electrostatic/hydrophobic interactions, hydrophobic tails, or GPI-anchors.

Osh4 is an oxysterol binding protein in yeast, and its physiological roles include sterol homeostasis and signal transduction.238 Osh4 is shown to transport sterol between liposomes, and the efficiency is enhanced by anionic lipids (e.g., PS and PIPs) at the target membrane.239 Karmakar and Klauda studied Osh4 binding to a membrane bilayer using all-atom MD simulations and HMMM models.230 Since the interaction between Osh4 and the membrane is mostly on the membrane surface, HMMM is a convenient and efficient model for characterizing such interactions. The authors found that both all-atom and HMMM membranes can successfully capture such interactions (Figure 5D). The binding of one facet of Osh4 to the membrane is more favorable than the other two. The simulations also showed the penetration of a phenylalanine loop into the membrane and identified the key interacting residues, in agreement with earlier cross-linking data. Another study by Aleshin et al. combined MD simulations with NMR and X-ray crystallography to study the binding of the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain with PIP lipids. NMR measurements identified key residues involved in PIP binding based on chemical-shift perturbations, while MD simulations further illustrated the binding interface and lipid configurations.240

K-ras is a GTPase cycled from a GDP bound “off” state to a GTP bound “on” state, which regulates cell growth.241 When the gene is mutated, the K-ras protein is constitutively switched on, allowing cells to grow uncontrollably and activating downstream pathways. K-ras mutations are found in about 30% of all human tumors and are the frequent drivers for pancreatic, colorectal, and lung tumor cases.241 Lu and Martí simulated G12D mutant of KRas-4B, a mutant common in cancers, and found two main orientations relative to the membrane.242 They further used well-tempered metadynamics simulations to derive the free energy of the binding configurations. The authors also found that GTP-binding to KRas-4B influences protein stabilization and can help open the Switch I/II druggable pockets. Given the difficulties in resolving the atomistic details of peripheral membrane protein binding to membranes, MD simulations offer a unique opportunity to identify important binding configurations and lay the basis for interpreting biophysical measurements such as cross-linking, NMR, and FRET.240

7. Protein–Lipid Interactions

7.1. LPS-Outer Membrane Protein in Gram-Negative Bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria possess two lipid bilayers: an inner and an outer membrane. The inner membrane is composed of phospholipids, while the outer membrane consists of phospholipids in the inner leaflet and LPS in the outer leaflet.243 The stability and impermeability of the outer membrane highly contribute to the antibiotic resistance of some pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa.244 LPS lipids are composed of three regions: lipid A, a hydrophilic core oligosaccharide attached to lipid A, and an O-antigen polysaccharide with a varying length of up to ∼25 repeating units.

Lee et al. investigated the interaction between outer membrane protein OprH and LPS by simulating OprH protein in three membranes with (i) lipid A, (ii) lipid A + core, and (iii) lipid A + core + O10-antigen in the outer leaflet.14 Their simulations show that the membrane thickness decreases around the protein due to the interactions between protein residues and LPS lipids. The extracellular loops of OrpH are highly charged and interact with both lipid A and O10-antigen through hydrogen bonds. In terms of dynamics, loop 2 is less dynamical in the longer full LPS membrane than in the shorter LPS membrane (Figure 6A). Such protein-LPS interactions explain why OprH can act as a membrane stabilizer and function to cross-link LPS when the divalent ion concentration is low.245 LPS represents a complex lipid structure, and its role in Gram-negative bacteria is important for bacterial drug resistance. Therefore, understanding the protein–lipid interactions in such membranes is of significance.

Figure 6.

Protein–lipid interactions revealed by MD simulations. (A) Interactions between LPS and outer membrane protein OprH, LPS sugars bind to the flexible hinge in OprH. Adapted with permission from ref (14). Copyright 2016 Biophysics Society. (B) Molecular switch of CHOL binding hotspots in Kir3.4 and its mutation leading to loss of the CHOL upregulation effect. Adapted with permission from ref (250). Copyright 2022 National Academy of Sciences. (C) PIP2 binding in the glucagon receptor, a class B GPCR protein, and the conformation preference of PIP2 binding to the inactive state. Adapted with permission from ref (253). Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society. (D) PE lipids disturb the conservative network in XylE transporter and favors the inward-open state. Adapted with permission from ref (254). Copyright 2018 Chloe Martens et al. Published by Springer Nature.

7.2. Search of Cholesterol Binding Motifs

CHOL is a vital component of mammalian plasma membranes and increasingly found to impact functions of a growing number of ion channels246 and GPCRs.247 Common motifs such as CRAC (cholesterol recognition/interaction amino acid consensus), CARC (the reverse sequence of CRAC), or CCM (cholesterol consensus motif) are putative CHOL-binding motifs.248,249 Studies, however, found that CHOL can also bind to other structural elements tightly.

Corradi et al. used CG simulations to study CHOL binding in Kir3.4, a potassium ion channel upregulated by CHOL.250 The authors identified a Met residue that, once mutated into Ile, made the effect of CHOL turn into downregulation. Through the long-time scale simulations of Kir3.4 wild type and M182I mutant in the CHOL-containing membranes, the CHOL binding hot spots were identified on the protein surface. The binding difference between the wild type and mutant shows that, in the mutant, the CHOL binding at the inner leaflet region is dominant and mostly located at the interface of neighboring subunits (Figure 6B). The study hypothesizes that the distribution of CHOL on protein surface plays a critical role in switching the regulation direction of CHOL.

Accompanying the development of PyLipID, a tool for analyzing protein–lipid interactions in MD simulation trajectories, Song et al. performed large-scale simulations for 10 class A and B GPCRs.251 They identified on average 14–17 CHOL binding sites per receptor. They then studied a total of 153 CHOL binding sites and classified the sites into strong vs nonspecific binding sites based on the buried area and CHOL residential time. Strong cholesterol binding sites have increased occurrence of Leu, Ala, and Gly residues, though these sites lack specific CHOL-binding motifs, which is also found in another study showing that there is no broadly recurring CHOL-binding motifs in GPCRs.252 The CHOL molecule is hydrophobic with the hydroxyl group providing potential hydrogen binding and polar interactions. Therefore, the binding of CHOL is mostly driven by hydrophobic interactions with protein, which partially leads to a lack of universal CHOL-binding motifs.194 This further requires more case-by-case studies on individual membrane proteins to identify their CHOL binding sites.

7.3. Phosphatidylinositol Phosphate (PIP) Binding

Phosphoinositides (PIPs), phosphorylated derivatives of phosphatidylinositol (PI), are essential components of eukaryotic cell membranes. PIPs play important roles in cell membrane dynamics, focal adhesion, action organization, and intracellular signaling255 and serve as modulators of GPCRs,253 ion channels,256 and transporters.257 The hydroxyl groups on the inositol ring of PI can be phosphorylated at the 3, 4, and 5 positions by specific kinases, giving rise to a group of structurally related PIPs, such as PI-monophosphate (PI3P, PI4P, and PI5P), PI-bisphosphate (PI(3,4)P2, PI(3,5)P2, and PI(4,5)P2), and PI-trisphosphate (PI(3,4,5)P3).258

To elucidate PIP2 binding on the glucagon receptor, a class B GPCR protein, Kjo̷lbye et al. used MD simulations to examine the binding of three types of PI(4,5)P2 lipids with varying tails to the receptor.253 The simulations show that the three PIP2 lipids have different binding profiles on the receptor. Notably, both (16:0/18:1) PIP2 and (18:0/20:4) PIP2 bind to the site between TM6/7 and H8 (Figure 6C). This site was also previously found to be the binding site of a negative allosteric modulator. Examining the conserved network and key indicators of active vs inactive forms shows that PIP2 lipids induce more inactive states than active states.

PIP lipids are also indispensable for ion channel regulations.259−261 Feng et al. recently studied PIP lipid binding to the TRPV2 ion channel and identified a region near the membrane-proximal area that binds to PIP lipids tightly.194 Through μs-long simulations, the PIP lipids gradually diffuse into the region and remain bound. This same region was previously found to be the putative PIP binding site by in vitro experiments.262 The simulation results provide a 3D structural context of the PIP binding site formed by S1, S2, and C-terminal membrane proximal regions.

Especially for integral membrane proteins, the binding sites of PIP lipids are usually difficult to predict in experiments. Cryo-EM structures are becoming more prevalent for understanding protein–lipid interactions, but due to the resolution and the mobility of lipids, it is hard to solve the PIP binding on membrane proteins. Therefore, MD simulation becomes a key tool to decipher the PIP binding sites as well as their dynamics.

7.4. Phospholipid Wedged in Proteins

Besides the aforementioned CHOL and PIP lipids, other phospholipids such as PC, PE, PG, and cardiolipin also interact with membrane proteins and modulate the protein conformations. Martens et al. studied xylose transporter XylE, consisting of both N- and C-lobes.254 During MD simulations, PE lipid diffused into the N- and C-lobe interface and disrupted the charge relay network formed by Glu or Asp (Figure 6D). PC lipids were not observed to have the same behavior, possibly due to its larger headgroup than PE. Furthermore, the PE binding in the interface favors the inward-open conformation, consistent with hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry observations. This demonstrates the conformational modulation by zwitterionic lipids. Another study by Choi et al. on glutamate transporter GLUT3 found that PE lipids boosted domain–domain assembly of the protein, though anionic lipids failed to have the same effects, demonstrating the role of PE lipids to ease the membrane remodeling during the protein folding.263

In other cases, the anionic lipids have a stronger effect due to stronger electrostatic interactions. Neale et al. studied the β2 adrenergic receptor using MD simulations to detect lipid binding in the receptor,264 because agonist binding is not sufficient to fully stabilize active states.265 Through simulations, the authors found a PC lipid binding to the crevice between TM6 and TM7, breaking an ionic lock, and stabilizing the active state. Furthermore, they simulated the receptor in a PG-containing membrane and found that anionic PG has a stronger and more stable binding in the same crevice than PC.

Cardiolipin (CL) is a phospholipid with four tails and comprises about 20% of the inner mitochondria membrane phospholipids mass.266 Yi et al. studied the effects of CL on mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier protein using MD simulations.267 By embedding the carrier protein in membranes with and without CL, the authors found that negatively charged CL lipids stabilize the domain 1–2 interaction through binding with surrounding positively charged residues and fold the M2 loop into a defined conformation. These results show how phospholipids can fit into the crevice and serve as molecular wedges in the protein assembly, stabilizing the structure or affecting the assembling process.

8. Drug-Membrane Interactions

8.1. Drug Mechanism and Permeation

As drug discovery studies boom, the need for understanding how drugs interact with the membrane becomes more prominent. The drug partition in the membrane can partially contribute to the drug efficacy, while drug location and influence on the membrane properties can dictate part of the toxicity.268 Natural products and their structural analogs have long been used in pharmacotherapy. In recent years, the improved analytical tools, genomic data mining and engineering strategies, and microbial culturing advances allow more screening, isolation, and characterization of natural compounds.269 Curcumin, a natural phenolic compound from turmeric, is widely used for food coloring and seasoning, which is antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory.270 Using MD simulations, Lyu et al. studied curcumin and examined its partition into pure bilayers such as POPE, POPG, POPC, DOPC, DPPE, and mixed membranes including POPE/POPG, E. coli membrane, and yeast membrane (Figure 7A).271 Curcumin is found to stay in the lipid tail region close to the glycerol, mostly with a parallel orientation and a membrane-thinning effect.

Figure 7.

Drug-membrane interactions and nano-biomembrane interfaces revealed by MD simulations. (A) Curcumin, a natural compound from turmeric and its interactions with different membranes. Adapted with permission from ref (271). Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. (B) A synthetic multipass transmembrane channel formed by multiblock amphiphiles is ligand-gated by 2-phenylethlamine (PA) or propranolol (PPN). Adapted with permission from ref (284). Copyright 2020 Takahiro Muraoka et al. Published by Springer Nature. (C) Graphene sheet adhesion and insertion to a membrane. Adapted with permission from ref (286). Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society. (D) A gold nanoparticle and its interaction with a lipid membrane. Adapted with permission from ref (287). Copyright 2019 Fabio Lolicato et al. Published by WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

A plethora of publications has examined the membrane interactions with a variety of compounds, including psilocin (active hallucinogen of magic mushrooms),272 ionic liquids,273,274 cancer drugs,275 DNA transfection reagent,15 and dye probes.276−278 Ionic liquids are liquid salts consisting of organic cations and inorganic anions and are considered a green alternative to organic solvents.279 Shobhna, Kumari, and Kashyap found that ionic liquids increase membrane condensing using simulations.274 Siani et al. studied doxorubicin, a widely used cancer treatment drug, in sphingomyelin-based membranes in order to optimize the liposome-based drug delivery for doxorubicin.275 Kneiszl, Hossain, and Larsson studied how intestinal permeation enhancers interact with membranes to lay the basis for improving the efficacy of oral administration drugs.280 Sabin et al. studied polyethylenimine and its interactions with membranes using simulations and showed that polyethylenimine induces pore-forming in the membrane, contributing to an understanding of the DNA cell transfection process.15 Winslow and Robinson developed a new phase-sensitive membrane raft probe through QM/MM simulations of different probes in the membrane.276

The studies of chemical-membrane interactions using MD simulations enable an atomistic understanding of the interactions, allowing calculations of influenced membrane properties and offering molecular details for processes ranging from gene transfection to materials design (ionic liquids, dye probe) and to drug acting mechanisms.

8.2. Artificial Channels

Artificial channels are polymer molecular machines consisting of peptides and polymers in the membrane bilayer, which is designed to mimic structural and functional features of their biological counterparts such as aquaporins, ion channels, and transporters.281 Functionally, these channels mimic the integral membrane proteins, but chemically, they are synthetic and represent a closer kin to the nanoparticles.

Song et al. designed an artificial water channel based on a cluster-forming organic nanoarchitecture, peptide-appended hybrid[4]arene.281 Once oligomerized, the channel has a central pore where water and ion can pass through. They used MD simulations to study the water permeation across the 22-mer cluster of the channel and the biological aquaporin-1 and found longer permeation time and path in the artificial channel.

The water permeation is also studied in other artificial water channels made of carbon nanotube282 or aggregated polymers283 using MD simulations. For example, Muraoka et al. designed a synthetic ion channel with multiblock amphiphiles and the ion permeation is gated by amine ligands (Figure 7B).284 When the ligand is bound, the channel is activated; otherwise the channel is deactivated. MD simulations were used to model the assembly and ligand binding to the polymer ion channel. Miao, Shao, and Cai used MD simulations to study an ion transporter consisting of a single molecule spanning the lipid bilayer.285 MD simulations show that the artificial transporter translocates K+ ions through alternating U-shape and linear shapes. The free energy of the transporter conformation in the membrane was then calculated using MD simulations. As the structures of artificial channels in the membrane are usually unknown, MD simulations provide a powerful tool to characterize the conformations and functions of the synthetic molecular machines in the membrane.

9. Nano-bio Interfaces

Nanomaterials are materials having at least one dimension less than 100 nm.288 Due to the desired physicochemical and electrical properties often displayed in nanomaterials, they are widely deployed in electronics, biomedicine, and aerospace engineering.289 The biomedical applications of nanomaterials include drug delivery, diagnostic, and therapeutic agents.290 As humans are constantly exposed to nanomaterials in the modern society, the nanomaterials find their way into the human body and can induce cell toxicity, immunotoxicity, and genotoxicity.288,290 Therefore, it becomes imperative to gain insight into the effect of nanomaterials on biomembranes and proteins.

Two-dimensional nanomaterials have a high surface-to-volume ratio, excellent functionalization capabilities, mechanical properties, and inherent optical properties to serve as biosensors, cell culture platforms, and diagnostic imaging reagent.291 Graphene is one of the most well-known 2D nanomaterials.292 Zhu et al. studied graphene nanosheets (GNs) and their membrane perturbation effects using MD simulations (Figure 7C).286 Two types of GN-membrane interactions were studied, adhered vs inserted. The adhered GNs on the membrane surface induce membrane thinning and more flexible lipid conformations, making it more difficult for lipid flipflop due to strong interactions between GNs and lipid head groups. Meanwhile, the inserted GNs lead to the ordering of nearby lipids and generate a nanodomain. Lipid flipflops have a lower barrier when far away from the inserted GNs but a much higher barrier in the vicinity of inserted GNs.

Nanoparticles are nanomaterials that have all three dimensions less than 100 nm.293 With the recent advances in nanoscience and nanotechnology, there has been an increasing interest in understanding the molecular mechanisms governing nanoparticle–membrane interactions for drug delivery, biomedical applications, and toxicity to human cells.294 Lolicato et al. reported the role of temperature and lipid charge on cellular intake of the cationic gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) (Figure 7D).287 By combining neutron reflectometry experiments with all-atom and CG MD simulations, they quantitatively revealed that both the lipid charge and temperature play pivotal roles in AuNP intake into lipid membranes. Foreman-Ortiz et al. integrated experimental and computational approaches to resolve the effect of nanoparticles on the function of membrane-embedded ion channels.295 They revealed that anionic AuNPs reduce activities of gramicidin A ion channels and extend channel lifetimes without disrupting membrane integrity, in a manner consistent with changes in membrane mechanical properties.

As nanomaterials applications further expand and mature, the toxicity on biological systems can be studied in more atomistic details through MD simulations. CHARMM-GUI Polymer Builder and Nanomaterial Builder offer polymers such as polyacrylamides, polydienes, polyamines, vinyls, polyesters, and nanomaterials such as carbon nanotube, graphene, graphite, silica, mica, metals, and metal oxides.40,41 These tools combined with Membrane Builder can help design better drug delivery systems for vaccines and biosafe/biocompatible materials.

10. Caveats and Pitfalls in Using Membrane Builder

As illustrated in Sections 4-9, Membrane Builder has been applied to numerous research topics for generating initial conditions. Although Membrane Builder has greatly facilitated the preparation of initial membrane simulation systems and successfully resolved many issues, such as mutations, modifications, and CHOL and peptide ring penetration by lipids, it is imperative to exercise caution when generating and simulating membrane systems to avoid introducing artifacts that could compromise the simulation results. Here, we list a few common issues that are not addressed by Membrane Builder and for which researchers should be careful in their practical applications.

10.1. System Size

When generating initial conditions, it is crucial to choose an appropriate membrane system size depending on the application type. Based on our own research experiences, we suggest to have at least 2–3 lipid shells between the transmembrane domain and the box edge on the membrane plane (i.e., the XY). One should check “step3_packing.pdb” to judge if the membrane size is big enough for their own application. Also, to avoid the artifacts due to the periodic boundary conditions, it is necessary to have enough box size for large extracellular and intracellular domains (e.g., Figures 4A and 4D). In addition, for simulations of spontaneously phase separated membranes, the system size should be sufficiently large to include at least thousands of lipids.296

10.2. Initial Lipid Packing

It is essential to inspect the initial lipid packing for any empty space between membrane peptides that could result in unrealistic aggregation. A recent simulation study reveals that the influenza virial fusion peptides in a leaflet aggregate within microseconds time scale.297 However, when the initial condition lacks sufficient lipids between fusion peptides, it results in unrealistically fast aggregation. In addition, for asymmetric membranes, the surface areas of both leaflets should be carefully matched to avoid large differential tension and altered mechanical properties, which can be significantly reduced by generating initial conditions using surface areas from cognate symmetric bilayers and/or using a P21-based approach39 (Figure 3E and subsection 4.5Methods for Generating Asymmetric Bilayers).

10.3. Proper Equilibration

Proper equilibration of any simulation is a crucial aspect that requires close monitoring. While the system sizes usually stabilize in submicrosecond time scales, multicomponent membranes and those with coexisting domains often require simulations of microseconds for equilibrated lipid distributions (around a peptide/protein) and substructures in the Lo phase.114−116,298 Hence, one should check proper equilibration during the simulation progress, especially for realistic complex membrane simulations.

11. Future Developments and Applications of Membrane Builder

CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder is a user-friendly web tool for various membrane-related simulations. It supports over 670 lipid/surfactant types and provides inputs for most of the common MD engines with various FFs ranging from atomistic models to CG and polarizable models. Different membrane structures including planar bilayers, micelles, vesicles, and nanodiscs can be generated. The linking with other CHARMM-GUI modules allows for building complex systems with protein, nucleic acids, ligands (Ligand Reader& Modeler), glycans (Glycan Reader& Modeler), glycolipids (Glycolipid Modeler), LPS (LPS Modeler), polymers (Polymer Builder), and nanomaterials (Nanomaterial Modeler) and can be combined with enhanced sampling techniques (Enhanced Sampler), high-throughput protein–ligand simulations (High-Throughput Simulator), and binding free energy calculations (Free Energy Calculator). Beside these capabilities, Membrane Builder can also be improved and further developed in the following areas.

Lipids are oxidized by enzymes like cyclooxygenases or nonenzymatically by uncontrolled oxidation.299 The oxidized lipids serve as key signaling mediators and hormones regulating metabolism, cell death, and inflammation, while uncontrolled oxidization can be harmful.300,301 The oxidized lipid library is currently under development. The library will contain lipids with the PC or PE headgroup and an oxidized sn-1 chain including aldehyde, ketone, hydroxyl, peroxide, and carboxyl groups. This will prompt more research on oxidized lipids and their roles in membranes and related proteins.

Mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), M. leprae, and M. avium have a significant impact on human health.302 Mycobacterial membranes are famous for their complexity uncommon in the Gram-positive bacteria. Mycobacteria have unusually long-chain fatty acids, mycolic acids, which can adopt different folded conformations to form a barrier.303 Other unique components include trehalose molecules, large branched structures (lipomannan and lipoarabinomannan) spanning the space between the inner and outer membranes, and phthiocerol dimycocerosates (PDIM), the major lipid virulence factors. All of these molecules are currently being implemented into Membrane Builder, which could greatly benefit mycobacterial membrane research.

Bicelles are synthetic lipidic discoidal aggregates of the lipid bilayer stabilized by detergents or short-tailed lipids on the rim.304 Bicelles can be oriented parallelly or perpendicularly to magnetic fields and can be doped with charged lipids, surfactants, or cholesterol to offer a wide variety of membrane environments for structural biology. Bicelle Builder is under development to support generating bicelle structures with varying q values (lipid to detergent ratios). In addition, all-atom lipid vesicle generation is not available, although it could be built in Martini Maker and then converted to all-atom models, which leads to limited types of lipids. Vesicle Builder in the future will allow generating vesicles with more diverse all-atom lipid types.

For more complex systems, it is currently difficult to include multiple copies of different components (other than lipids and ions) at desired locations in a membrane or bulk. Also, generating multilamellar membranes is not supported, which can be useful for establishing asymmetric environment on each side of the bilayer. For studying interactions between nanoparticle and biological membranes and between peptide and membrane-like polymers,286,287,295,305 systematic generation of such systems is not available in CHARMM-GUI yet. The above issues will be addressed by Multicomponent Assembler in CHARMM-GUI in the near future, which will allow easy generation of realistic biological membranes and nano-bio interfaces.