Abstract

Objective:

To (i) determine the rate of satisfactory response to non-operative treatment for non-arthritic hip-related pain, and (ii) evaluate the specific effect of various elements of physical therapy and non-operative treatment options aside from physical therapy.

Design:

Systematic review with meta-analysis.

Literature search:

Seven databases and reference lists of eligible studies through February 2022.

Study selection criteria:

Randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies that compared a non-operative management protocol to any other treatment for patients with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome, acetabular dysplasia, acetabular labral tear, and/or non-arthritic hip pain not otherwise specified.

Data synthesis:

Random-effects meta-analyses, as appropriate. Study quality was assessed using an adapted Downs and Black checklist. Certainty of evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach.

Results:

Twenty-six studies (1,153 patients) were eligible for qualitative synthesis, and sixteen were included in meta-analysis. Moderate certainty evidence suggests the overall response rate to non-operative treatment was 54% [95% CI 32%−76%]. The overall mean improvement after physical therapy treatment was 11.3 points [7.6–14.9] on 100-point patient-reported hip symptom measures (low-to-moderate certainty) and 22.2 points [4.6–39.9] on 100-point pain severity measures (low certainty). No definitive specific effect was observed regarding therapy duration or approach (i.e., flexibility exercise, movement pattern training, and/or mobilization) (very low to low certainty). Very low to low certainty evidence supported viscosupplementation, corticosteroid injection, and a supportive brace.

Conclusion:

Over half of patients with non-arthritic hip-related pain reported satisfactory response to non-operative treatment. However, the essential elements of comprehensive non-operative treatment remain unclear.

Keywords: Hip, Femoroacetabular impingement, Acetabular dysplasia, Acetabular labral tear, Non-operative management

INTRODUCTION

Hip-related pain from conditions such as femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAIS), acetabular dysplasia, and acetabular labral tears can cause impaired function and early osteoarthritis in adolescents and young adults.7,16,30,60 Treatment is often categorized into two choices: operative and non-operative care.17,38,48,53 While high-quality randomized controlled trials and longitudinal cohort studies support the effectiveness of surgery in appropriately selected patients,2,41,42 the effects of non-operative treatment for hip-related pain are unclear. In fact, although physical therapy, activity modification, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and intra-articular hip injections are frequently recommended, there is still no agreement on the essential elements of non-operative treatment.40

Multiple pilot randomized controlled trials that describe the effectiveness of non-operative management for non-arthritic hip-related pain have recently been published, but many consisted of relatively small sample sizes and often evaluated vastly different non-operative treatment protocols. Recent syntheses have effectively summarized the current trends in non-operative treatment protocols,40 and they have even compared management components to each other (e.g., physical therapist led intervention versus injection or surgery).33,36 One meta-analysis also investigated key elements of physical therapy that were associated with favorable outcomes for FAIS,25 but it defined waitlist control groups and usual care cohorts as receiving “unsupervised therapy with no focus on core strengthening,” even though these patients could have been receiving no true treatment at all.25

A gap still exists regarding many treatment details related to non-operative management, including the rate of satisfactory response to non-operative treatment in this patient population, the ideal dose of physical therapy (i.e., visit frequency, duration, and therapeutic content), and the effectiveness of elements aside from physical therapy. Most previous work has focused on FAIS and has excluded other conditions that can cause hip-related pain. Even though these conditions frequently co-exist, they exist on a morphologic spectrum, and clinicians often manage hip-related pain before structural diagnoses have been established with advanced imaging.14,25,36,56

Because not all patients with hip-related pain are ideal surgical candidates and/or desire surgery,43 it is important to continue improving comprehensive non-operative treatment. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we sought to (i) determine the rate of satisfactory response to non-operative treatment for non-arthritic hip-related pain, (ii) synthesize existing evidence regarding the specific effect of various elements of physical therapy, and (iii) summarize evidence for non-operative treatment options aside from physical therapy.

METHODS

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The study protocol was preregistered on PROSPERO (CRD42019133620). The only deviation from the preregistered protocol was incorporation of the Grades of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) framework, per suggestion during peer review, to grade the certainty of synthesized evidence. None of the funding sources were involved in the study conduct or interpretation of results. Institutional ethical approval was not required, as no individually identifiable data were collected from humans or animals in this review. No patients or public partners were involved in the conduct of this study.

Eligibility criteria:

Consistent with the 2018 Zurich consensus recommendations from the International Hip-related Pain Research Network,51 eligible hip-related pain disorders included FAIS, acetabular dysplasia, acetabular labral tears, and non-arthritic hip pain without clear osseous pathology. Any non-operative treatment protocol (e.g., physical therapy, activity modification, medications, injections, psychosocial management, bracing, etc.) and any clinical outcome was eligible for inclusion, as was any follow-up duration and publication date. Eligible study designs included randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. For studies that compared a non-operative intervention to surgery or a waitlist control, only the non-operative treatment arm was considered for eligibility. Exclusion criteria included studies focused on extra-articular hip disorders or other intra-articular hip disorders (i.e., slipped capital femoral epiphysis, Legg-Calve-Perthes disease, avascular necrosis, and osteoarthritis), studies that did not include a detailed description of the non-operative management protocol, studies that only evaluated post-operative rehabilitation protocols, retrospective cohort studies, reviews, case series/reports, abstract-only studies, non-English language studies, and non-human studies.

Search strategy:

A systematic literature search was performed by a trained medical librarian (KLL). The following databases were searched: PubMed/Medline (1946-), EMBASE (1947-), CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health, 1937-), SCOPUS (1823-), Web of Science (WOS, 1900-), The Cochrane Library, and ClinicalTrials.gov. The search strategy was conducted using the controlled vocabulary of each database and plain language keywords in the general structure of “[hip] and [pre/non-arthritic] and [non-operative management].” Treatment-related search terms included but were not limited to “physical therapy,” “exercise movement,” “stretching,” “joint mobilization,” “activity modification,” “medications,” “injections,” “viscosupplementation,” and “psychosocial management” (SUPPLEMENTAL FILE 1). The references of each study that met the eligibility criteria were also reviewed to identify other relevant studies. The search was most recently conducted in February 2022.

Study selection and data collection:

Two independent reviewers (DTP, ALC, and/or MFS) independently assessed each study title, abstract, and full text for eligibility, as applicable, and the rationale for exclusion of ineligible studies was recorded. No automated screening tools were used. Two reviewers (DTP, ALC, and/or MFS) independently extracted the following available variables from eligible studies: publication journal, publication year, study institution(s), enrollment period, number of providers, study design, primary hip diagnosis and method of diagnosis, eligibility criteria, number of participants, source population, comparison groups (if any), treatment types, treatment duration, number of treatment sessions, treatment details, clinical outcome measures (and which was specified as primary, if any), follow-up time point(s), post-intervention clinical outcome values (e.g., proportion meeting a pre-specified outcome, mean change in continuously reported outcomes), and adverse events. All disagreements regarding study eligibility and data values were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers and arbitration by the third reviewer, if needed. Some eligible manuscripts did not report data elements necessary for meta-analysis even though the relevant effect size was reported (e.g., no error term reported for the mean change in a clinical outcome score). For these studies, the corresponding authors were contacted via e-mail, but no supplemental data from any of the original studies was provided to us. Therefore, these studies were included in the systematic review but not the meta-analyses.12,17,27,39,48,49

Quality and bias assessment:

The Downs and Black checklist was used to uniformly describe study quality and risk of bias across both randomized and prospective cohort studies.11 The original checklist was adapted by removing items 17, 18, 21, 22, and 27 because these items focus on between-group comparisons, whereas our systematic review is focused on between-study comparisons of both randomized controlled trials and cohort studies such that multiple arms of a single trial were not included in the same meta-analysis. Therefore, our adapted checklist has 22 items and 23 possible points. Higher scores are suggestive of less risk of bias. To mirror other studies using adapted Downs and Black checklists, scores of 21–23 were a priori considered excellent, 16–20 were good, 12–15 were fair, and 11 or lower were poor.26,34 Included studies were rated by two independent reviewers (DTP, ALC, and/or MFS). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between the reviewers and arbitration by the third reviewer, if needed.

Outcome and summary measures:

When multiple clinical outcomes were reported in an original manuscript, the measure labeled as the primary outcome was used for meta-analysis, as applicable. If no measure (or multiple measures) were identified as the primary outcome(s), then the measure that allowed the most direct comparison to other studies was used. For studies that reported on the same group of patients (based on study institution, eligibility criteria, and dates of recruitment), only the study that provided the largest sample size was included in the relevant meta-analyses.

To analyze the specific effect of various elements of physical therapy, treatment arms that included physical therapist-led intervention were categorized as including one or more of the following elements: active exercise (defined as exercises performed by the patient with the primary goal to improve muscle performance, e.g., strengthening or neuromuscular activation); flexibility exercise (defined as exercises performed by the patient with the primary goal of improving flexibility of a joint or extensibility of a muscle); movement pattern training (defined as practice of functional tasks (or simplified tasks) with the primary goal of optimizing biomechanics of movement (e.g., eliminating pelvic drop and hip adduction)); and joint or soft tissue mobilization (defined as a skilled manual technique that is applied by the clinician at the joint, segment (e.g., spine), or soft tissue, with the primary goal of improving joint range of motion or reducing pain hypersensitivity).

Data synthesis:

We performed 3 meta-analyses. To address the first aim, a meta-analysis was performed to determine the proportion of responders to non-operative treatment. Per the original studies, patients who met at least one of the following criteria were defined as responders: no surgery and/or no recurrent pain during the follow-up period, global rating of change of at least moderately better, or achievement of the Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS) on the HOS (Hip Outcome Score) ADL (Activities of Daily Living) subscale.

To explore the specific effect of various elements of physical therapy, meta-analyses were first performed to assess the overall effect of physical therapy on the mean change of patient-reported: 1.) hip-specific symptom measures, and 2.) pain severity measures. Hip-specific symptom measures, scored on a 100-point scale with higher scores being favorable, included the HOOS (Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score) ADL subscale, HOS ADL subscale, and the iHOT-33 (33-item International Hip Outcome Tool). Pain severity measures, scored on a 10- or 100-point scale, with lower scores being favorable, included the visual analog scale and numeric pain rating scale. To generate effect sizes that are easily interpretable by patients and providers (who are accustomed to describing hip symptom severity on 100-point scales), pain scores on 10-point scales were transformed to 100-point scales by multiplying the scores and error terms by 10. Then, meta-analyses were performed to determine the unstandardized longitudinal mean differences of the non-operative treatment protocols on 100-point scales.

Subgroup analyses were then performed on the meta-analysis of hip-specific symptom measures in order to compare the specific effects of physical therapy duration and the inclusion (versus exclusion) of flexibility exercise, movement pattern training, and/or joint or soft tissue mobilization as part of physical therapy (SUPPLEMENTAL FILE 2) (the limited available literature did not allow for subgroup analyses based on the level of supervision of physical therapy or the inclusion of active physical therapy exercise, nor did it allow for meta-regression to control for potential interactions between physical therapy elements.) Due to the clinical heterogeneity of the original studies, all meta-analyses were run as random-effects models, and statistical heterogeneity is reported as the I2 calculated via the Mantel-Haenszel method. None of the eligible studies that focused on the effectiveness of intra-articular hip injections reported statistical details sufficient for meta-analysis. Meta-analysis was not considered for studies reporting the effectiveness of bracing because only two studies were identified.

An influence analysis for each meta-analysis indicated that omission of any single study did not produce an effect size that lay outside the 95% confidence interval of the combined analysis. Funnel plots were also created which, although limited due to the relatively small number of studies, did not suggest any clear small-study effects. All analyses were performed using STATA BE 17.

Using the GRADE approach, the certainty of evidence for each outcome of interest was rated as high, moderate, low, or very low. Certainty was determined by considering the designs of the original studies and then, as applicable: 1.) down rating for risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, and/or indirectness, and 2.) up rating for a large magnitude of effect, dose-response gradient, and/or if all residual confounding would decrease an apparent effect when the results already suggest no effect.19,29

RESULTS

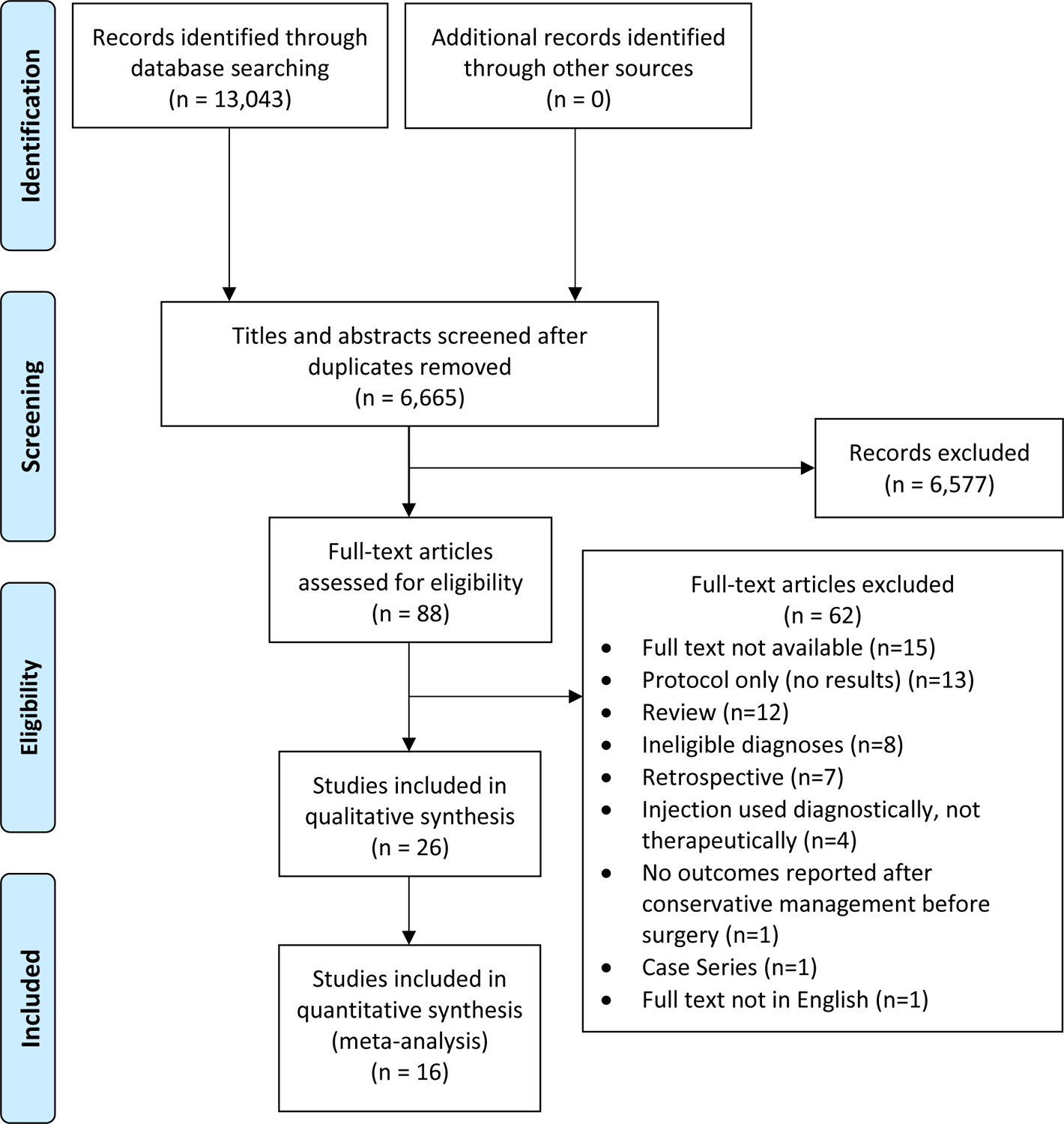

Of 13,043 studies identified, 26 were eligible for inclusion in the qualitative synthesis, and 16 had data appropriate for meta-analysis (FIGURE 1). In total, the studies included 1,153 patients (1,240 hips). Of the 26 eligible studies, 21 investigated physical therapist led interventions (TABLE 1A), 3 investigated injection related treatments (TABLE 1B), and 2 investigated the effectiveness of a hip brace (TABLE 1C) (SUPPLEMENTAL FILE 3). The majority of studies focused exclusively on populations of patients with FAIS.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram of included studies.

TABLE 1A. Physical therapist led intervention studies for hip-related pain: Key study characteristics.

Studies with bolded author names and publication years indicate those studies which could be included in at least one meta-analysis.

| Author (Year) Journal |

Study type | Patient diagnosis N per treatment arm: Patients (Hips) Recruitment location |

PT duration # PT Sessions (Face-to-face) (Trainings) |

PT classification (Other treatment details) |

Outcome measuresa (Time points) |

Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aoyama (2017)

Clin J Sports Med |

RCT | FAIS in females Intervention: 10 (10) Control: 10 (10) Surgery clinic |

8 weeks 1 session (Daily training) |

|

|

Statistically significant improvement in mean iHOT-12, Vail hip score, hip flexion range, and hip abduction strength in the “hip+core” strengthening group at 8 weeks. No improvement in patient-reported outcomes in the “hip only” strengthening group. Mean between-group differences at 8 weeks: 25.7 points for iHOT-12 20.5 points for Vail hip score No between-group differences in modified Harris Hip Score. |

|

Casartelli (2019)

Arthritis Care Res |

Prospective single-arm cohort | FAIS 31 (31) Surgery clinic |

12 weeks 24 sessions (4 trainings/week) |

|

|

16/31 (52%) of patients responded to the treatment protocol, defined by the Global Treatment Outcome Questionnaire at 18 weeks. Responders improved mean HOS-ADL (by 10 points) and HOS-Sport (by 20 points). The prevalence of patients improving dynamic pelvic control only increased in responders (from 19% to 63%). Prevalence of severe cam morphology was higher in non-responders (40%) than responders (6%). |

|

Emara (2011)

J Orthop. Surg (Hong Kong) |

Prospective single-arm cohort | FAIS, mild (α<60⁰) 37 (37) Clinic |

2–3 weeks Sessions N/D Trainings N/D |

|

|

4/37 (11%) progressed to surgery. The remaining patients improved mean Harris Hip Score (by 19 points), non-arthritic hip score (by 19 points), and VAS (by −4 points) at 24 months. 6/33 (18%) had recurrent hip pain at 24 months. No significant improvement in hip ROM. |

|

Grant (2017)

J Hip Preserv Surg |

RCT pilot (Only the pre-habilitation treatment arm was eligible for inclusion) |

FAIS + labral tear, Receiving pre-habilitation while awaiting hip arthroscopy Intervention: 9 (9) Surgery clinic |

7 weeks 2 sessions (Daily training) |

|

|

After pre-habilitation but before hip arthroscopy, patients reported a worse mean non-arthritic hip score (by −3.7 points) but improved EQ-5D-5L (by 20 points) and improved hip abduction, adduction, flexion, external rotation, and knee extension strength. No statistical comparison tests were performed on these outcome measures across the pre-operative time interval. |

|

Griffin (2018)

Lancet |

RCT (Only the Personalized Hip Therapy treatment arm was eligible for inclusion) |

FAIS, Believed likely to benefit from hip arthroscopy 177 (177) Surgery clinic |

12–24 weeks 6–10 sessions (At least 3 sessions face-to-face, others allowed by telephone instead) (Training frequency customized per person) |

(Also included patient education and 1 intra-articular steroid injection if needed) |

Primary: iHOT-33 Secondary:

|

Mean iHOT-33 scores improved by 14.1 points at 12 months (from 35.6 to 49.7). Quantitative longitudinal results were not reported for the secondary outcomes. |

|

Guenther (2017)

Physiother Can |

Prospective single-arm cohort, feasibility study (Only considered pre-operative longitudinal changes) |

FAIS, Undergoing pre-habilitation prior to hip arthroscopy 20 (20) Surgery clinic |

10 weeks 5 sessions with kinesiologist (4 trainings/week) |

|

|

Mean scores improved on all HOOS sub-scales (by 8.5 points on Pain, 10.4 on ADLs, 7.9 on Symptoms, 11.7 on Sports, 7.6 on Quality of life). 10/20 (50%) patients reported their hip pain improved, 8/20 (40%) reported no change, & 1/20 (5%) reported worsening of hip pain. 5/20 (25%) patients canceled their scheduled hip surgery. |

|

Harris-Hayes (2016)

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther |

RCT pilot (Only the Movement Pattern Training treatment arm was eligible for inclusion) |

Chronic hip joint pain 18 (18) Surgery, physiatry, & physical therapy clinics; Community advertisement |

6 weeks 6 sessions (Daily training) |

|

Primary: Feasibility Secondary:

|

Mean scores improved on HOOS ADLs (by 2.8 points), HOOS Symptoms (by 10.0 points), and HOOS Sport (by 7.5 points). Hip adduction during single-leg squat was reduced/improved, only in patients with high baseline hip adduction. |

|

Harris-Hayes (2018)

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther |

RCT pilot (Ancillary analysis of Harris-Hayes 2016 intervention arm + wait-list control arm. Both arms received Movement Pattern Training.) |

Chronic hip joint pain 28 (28) Surgery, physiatry, & physical therapy clinics; Community advertisement |

6 weeks 6 sessions (Daily training) |

|

|

Mean scores improved on the modified Harris Hip Score (by 4.1 points) and all HOOS sub-scales (Pain: 5.9 points, Symptoms: 9.6 points, ADLs: 6.0 points, Sport: 9.0 points, Quality of life: 6.3 points). Mean hip abduction strength and hip adduction angle during single-leg squat was improved. Improved hip adduction angle correlated with greater improvement on the modified Harris Hip Score, but hip abduction strength and alpha angle did not. |

|

Harris-Hayes (2020)

BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med |

RCT pilot | Chronic hip joint pain Intervention: 23 (23) Control: 23 (23) Community advertisement; Surgery, physiatry, & physical therapy clinics |

12 weeks 10 sessions (Daily training) |

|

Primary: Feasibility Secondary:

|

Both groups reported clinically meaningful improvement in all HOOS subscales (by 12–24 points), the PSFS, PROMIS scores, the pain NRS, and hip strength, with no between-group differences. The Movement Pattern Training arm improved hip adduction and pelvic tilt during a single leg squat to a greater degree than the strengthening/stretching arm. |

|

Harris-Hayes (2021)

J Orthop. Res |

RCT pilot (Ancillary analysis of Harris-Hayes 2020 intervention arm) |

Chronic hip joint pain Intervention: 23 (23) Control: 23 (23) Community advertisement; Surgery, physiatry, & physical therapy clinics |

12 weeks 10 sessions (Daily training) |

|

|

Both groups reported sustained improvements in all HOOS subscales, the PSFS, and the pain NRS, with no between-group differences. No patient in either arm scheduled or underwent surgery.a |

|

Hunt (2012)

PM&R |

Prospective single-arm cohort | Pre-arthritic hip disorder 58 (58) Surgery and physiatry clinics |

12 weeks Mean 6.4 sessions (range 1–19) Trainings N/D |

|

|

23/52 (44%) were satisfied with conservative care at 3 months and did not progress to surgery. At 12 months, patients who did not proceed to surgery reported improvement in all outcome measures except for a reduction in activity level (e.g., modified Harris Hip Score improved by 9.5 points, Non-arthritic hip score improved by 11.2 points). |

| Hunter (2021) BMC Musculoskel Disord | RCT (Only the rehabilitation treatment arm was eligible for inclusion) |

FAIS 50 (50) Surgery clinics |

12–24 weeks 6–10 sessions (Number of sessions customized per person) |

(Also included patient education and 1 intra-articular steroid injection if needed) |

Primary: Change in cartilage dGEMRIC score on MRI Secondary:

|

Of 21/50 (42%) patients with primary outcome data, mean dGEMRIC scores improved at 12 months (48.4 points [95% CI −16.6 to 113.5]). All secondary patient-reported measures improved to a statistically significant degree at 6 and 12 months except for EQ5D-VAS at 6 months. Twelve-month improvements included: 15.4 points on iHOT-33, 0.1 points on EQ-5D-5L, 5.8 points on EQ5D-VAS, 11.1 points on HOOS Pain, 9.6 points on HOOS Symptom, 7.4 points on HOOS ADL, 13.2 points on HOOS Sport, and 15.6 points on HOOS Quality of Life (n=41–46). |

|

Kemp (2018)

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther |

RCT pilot | FAIS Intervention: 17 (17) Control: 7 (7) Clinic and community advertisement |

12 weeks 8 face-to-face PT sessions + 12 weekly supervised gym visits (3–4 trainings/week) |

|

|

The intervention arm reported large improvements in mean iHOT-33 (by 27 points), HOOS-Quality of life (by 22 points), and HOOS-Pain (by 20 points), in addition to large strength gains. The control arm reported more modest improvements in iHOT-33 (by 11 points) and HOOS-Pain (by 9 points), with moderate to large strength gains. |

|

Mansell (2018)

Am J Sports Med |

RCT (Only the rehabilitation treatment arm was eligible for inclusion) |

FAIS 40 (40) Referral process for military surgery & physical therapy clinics |

6 weeks 12 sessions (Active exercise: 3–4 trainings/week; Flexibility and mobilization exercise: 1–3 trainings/day) |

|

Primary: HOS-ADLb & HOS-Sport Secondary:

|

28/40 (70%) patients assigned to the rehabilitation arm underwent hip surgery. In the intention-to-treat analysis, patients assigned to the rehabilitation arm reported a mean HOS-ADL improvement of 12.1 points at 2 years. In the as-treated analysis, the patients who received rehabilitation and did not cross over to surgery reported a mean HOS-ADL improvement of 18.1 points at 2 years, but this was not statistically significant. |

|

Martin 2021

Am J Sports Med |

RCT (Only the “physical therapy alone (PTA)” treatment arm was eligible for inclusion) |

Acetabular labral tear 44 (44) Surgery clinic |

24 weeks At least 1 face-to-face session/week Trainings N/D |

|

Primary (at 12 months):

|

28/44 (64%) patients assigned to the “physical therapy alone” arm crossed over to the surgical arm and underwent hip surgery. In the intention-to-treat analysis, the 44 patients assigned to the physical therapy arm reported a mean improvement of 22.4 points on iHOT-33, 12.6 points on mHHS, and 2.9 points on the pain VAS. In the as-treated analysis, the 16 patients who remained in the physical therapy arm reported a mean improvement of 17.4 points on iHOT-33, 7.3 points on mHHS, and 2.0 points on the pain VAS. |

| Murtha (2021) J Pediatr Orthop | Prospective single-arm cohort (Subset of patients from Pennock 2018 and Zogby 2021 cohort) |

Acetabular labral tear 33 (36) Surgery clinic |

Weeks N/D, but target was to meet PT goals within 6 weeks Sessions N/D Trainings N/D |

|

|

At an average of 36 month follow-up, 15/36 (42%) hips continued with physical therapy and activity modification alone, 10/36 (28%) had received one steroid injection, and 11/36 (31%) had undergone surgery. There were no significant between-group differences based on treatment course in the mean longitudinal improvement on mHHS (19.6–26.2 points) or NAHS (12.0–21.3) or the proportion of hips meeting the MCID (8 points) for mHHS (73–82%, p=.86). 2/36 (6%) hips were offered surgery but declined and did not meet the MCID for the mHHS. 6/36 (17%) quit sports due to hip pain (4 who did not have surgery, 2 who had surgery). |

|

Palmer (2019)

Br Med J |

RCT (Only the “physiotherapy and activity modification” treatment arm was eligible for inclusion) |

FAIS 110 (110) Surgery clinics |

20 weeks Up to 8 sessions Trainings N/D |

|

Primary: HOS-ADL Secondary:

|

HOS-ADL improved by 3.5 points (from 65.7 to 69.2) at 8 months. Clinically important improvement in the HOS-ADL (i.e., 9+ points) was achieved by 32% of patients, a patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) on the HOS-ADL (i.e., 87+ points) was achieved by 19%, and 15% achieved their expected HOS-ADL score by 8 months. |

|

Pennock (2018)

Am J Sports Med |

Prospective single-arm cohort | FAIS in adolescents 100 (133) enrolled 76 (93) available for follow-up Surgery clinic |

Weeks N/D, but target was to meet PT goals within 6 weeks Sessions N/D Trainings N/D |

|

|

65/93 (70%) hips were managed successfully with rest, physical therapy, and activity modification. An additional 11/93 (12%) hips required a steroid injection. Only 17/93 (18%) hips progressed to surgery. Mean scores improved on the modified Harris Hip Score (by 21 points) and non-arthritic hip score (by 13 points) at 2 years in patients not undergoing surgery. |

|

Smeatham (2017)

Physiotherapy |

RCT pilot (Only the physiotherapy treatment arm was eligible for inclusion) |

FAIS 15 (15) Surgery clinic |

Weeks N/D Protocol: 10 Sessions, Actual: mean 6.5 sessions (range 1–13) Trainings N/D |

|

Primary: Feasibility Secondary:

|

Mean scores improved on the total non-arthritic hip score (by 12.7 points), HOS-ADL (by 9.3 points), HOS-Sport (by 16.5 points), and LEFS (by 11.5 points) at 3 months. |

|

Wright (2016)

J Sci Med Sport |

RCT pilot | FAIS Intervention: 7 (7) Control: 8 (8) Surgery clinic |

6 weeks Intervention: 12 sessions Control: 1 session (2–3 trainings/week) |

|

Primary:

|

In the intervention group, mean scores improved for the HOS-ADL (by 6.9 points) and HOS-Sport (by 10.6 points), which were not statistically significant. Mean VAS-pain improved by 17.6 mm (statistically significant). In the control group, mean scores improved for the HOS-ADL (by 11.4 points), HOS-Sport (by 21.0 points), and VAS-pain (by 18.0 mm), which were clinically and statistically significant. No statistically significant between-group differences in primary or secondary measures. 8/15 (53%) proceeded to surgery. |

|

Zogby (2021)

Am J Sports Med |

Prospective single-arm cohort (Longer term follow-up of Pennock 2018 study) |

FAIS in adolescents 100 (133) enrolled 51 (69) available for follow-up Surgery clinic |

Weeks N/D, but target was to meet PT goals within 6 weeks Sessions N/D Trainings N/D |

|

|

At mean 5-year follow-up, 50/69 (72%) hips continued with physical therapy and activity modification alone, 7/69 (10%) had received one steroid injection, and 12/69 (17%) had undergone surgery. There was no significant between-group difference based on treatment course in the mean longitudinal improvement on mHHS (16.7–20.7 points) or NAHS (11.9–14.7) or the proportion of hips meeting the MCID (8 points) for mHHS (71–75%, p=.99). 11/12 (92%) hips that did require surgery had surgery within 2 years of enrollment. Mean scores improved on the modified Harris Hip Score (by 21 points) and non-arthritic hip score (by 13 points) at 2 years in patients not undergoing surgery. |

Abbreviations: ADL (Activities of daily living), dGEMRIC (delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI of cartilage), FAIS (femoroacetabular impingement syndrome), FABER (flexion, abduction, external rotation), HAGOS (Copenhagen hip and groin outcome score), HOOS (Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score), HOS (Hip Outcome Score), iHOT (International Hip Outcome Tool), N/D (Not described), LEFS (Lower extremity functional scale), MCID (minimum clinically important difference), mHHS (modified Harris Hip Score), NRS (numeric rating scale), NSAID (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug), PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System), PSFS (Patient specific functional scale), PT (physical therapy), RCT (randomized controlled trial), ROM (range of motion), SF-12 (12-item Short Form Health Survey), VAS (visual analog scale), WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index).

If not specified in the Outcome Measures column, the primary outcome was not defined by the study authors.

Denotes the outcome measure included in the meta-analysis of the effect of physical therapy on hip-specific functional measures.

TABLE 1B.

Injection related studies for hip-related pain: Key study characteristics.

| Author (Year) Journal |

Study type | Patient diagnosis N: Hips (Patients) Recruitment location |

Injectate | # Injections Timinga (Guidance type) |

Outcome measuresa (Time points) |

Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abate (2014)

Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc |

Prospective, single-arm cohort | FAIS 20 (23) N/D |

High molecular weight (32mg/2ml) hyaluronic acid | 4 Baseline, Day 40, Month 6, Month 6 + 40 days (Ultrasound) |

|

Statistically significant improvement of all outcome measures by 12 months. Mean change: 4.9 points for Harris Hip Score, 5.0 points for 10-point VAS, −7.5 points for Lequesne Index, and −2.3 NSAID tablets/week. |

|

Lee (2016)

J Korean Med Sci |

Double-blind, randomized, modified cross-over | FAIS 30 (43) Surgery & interventional radiology clinics |

20 mg (0.5 mL) triamcinolone + 1.5 mL normal saline or 2 mL sodium hyaluronate (Hyruan Plus Inj) |

1–2 Baseline, Could cross over and receive other injection if no clinical response at two weeks (Fluoroscope) |

|

No between-group difference in clinical response at 2 weeks. At 2 weeks, 7/14 (50%) patients crossed over from the hyaluronic acid arm, and 6/16 (37.5%) crossed over from the corticosteroid arm. Among patients who only received hyaluronic acid, mean HOOS improved by 8.6 points at 6 weeks (12-week outcome not reported), and mean 10-point NRS improved by 4 points at 12 weeks. (Statistical significance N/D.) Among patients who only received corticosteroid, mean HOOS improved by 5.75 points, and mean 10-point NRS improved by 5.5 points at 12 weeks. (Statistical significance N/D.) Changes in other outcome measures were not specifically stated for patients who received only hyaluronic acid or only corticosteroid. |

|

Ometti (2020) J Drug Asses. |

Prospective, single-arm cohort | FAIS 19 (21) Surgery clinic |

Hymovis (HYADD4-G, a hexadecylamide derivative of hyaluronic acid) | 2 Baseline, Week 1 (Ultrasound) |

|

Statistically significant improvement on all outcomes except Tegner activity level scale at 12 months, with the most dramatic improvements reported by Month 1. Mean changes: 16.5 points for Harris Hip Score, −41.1 points for 100-point VAS, −4.8 points for Lequesne Index, and −9.2 for NSAIDS tablets/month No significant improvement in Tegner activity level scale at any follow up point. |

Abbreviations: FAIS (femoroacetabular impingement syndrome), HOOS (Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score), N/D (Not described), NRS (numeric rating scale), NSAID (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug), VAS (visual analog scale).

The primary outcome measure and time point was not defined for any study.

TABLE 1C.

Bracing related studies for hip-related pain: Key study characteristics.

| Author (Year) Journal |

Study type | Patient diagnosis N: Hips (Patients) Recruitment location |

Brace | Bracing schedule | Outcome measures (Time point) |

Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Eyles (2021)

Clin J Sports Med |

RCT pilot | FAIS or symptomatic acetabular labral tear Intervention (Usual conservative care + brace): 19 (19) Control (Usual conservative care): 19 (19) Surgery clinic |

Hip Unloader, Össur, Reykjavik, Iceland) Elastic strap with an adjustable loading mechanism that wraps around the affected leg and has a compressive pelvic belt. The strap exerts a traction force to reduce combined hip adduction, internal rotation, and flexion. The belt aims to reduce trunk flexion and dynamic anterior pelvic tilt. |

At least 4 hours/day after building tolerance, total 6 weeks | Primary: iHOT-33 Secondary:

|

Mean longitudinal improvement on iHOT-33 was 17.4 points in the intervention arm and 0.5 points in the control arm. The mean between-group difference at 6 weeks for iHOT-33 was 19.4 points [95% CI 1.7 to 37.1], favoring the intervention arm (p=.03). Between-group differences at 6 weeks on HAGOS subscales were 18.7–21.5 points, favoring the intervention arm (p=.02–.06). Over half (9+/17) of participants were quite/very satisfied with the brace except for the domains of comfort and effectiveness. Almost half of participants only wore the brace for 1–2 hours daily on average. (“Usual conservative care” was defined as “any combination of education, advice, watchful waiting, analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, referral for physiotherapy, and corticosteroid injection.” There were no significant differences in the use of usual conservative treatments between groups.) |

|

Newcomb (2018)

J. Sci. Med. Sport |

Prospective, single-arm cohort | FAIS 25 (25) recruited, but 17 (17) agreed to wear brace Surgery clinic |

Stability thru External Rotation of the Femur (SERF) strap, Don Joy Orthopaedics Light-weight, thin, elastic material. Utilizes a 3-point hip-leg anchor around the pelvis, distal thigh, and proximal tibia, with an oblique strapping around the thigh. Fitted to achieve maximum passive hip external rotation while standing. |

At least 4 hours/day for 4 weeks |

|

On the global rating of change, 10 (59%) patients reported (at least moderately) improved pain, 13 (76%) reported improved function, and 10 (59%) reported overall improvement. No significant difference in mean pain or function scores were reported on any other patient-reported measures between baseline and follow-up. Quantity of brace wear did not correlate with change in pain or function. Wearing the brace consistently reduced peak hip adduction, flexion, and internal rotation during stair ascent/descent and constrained/unconstrained squat, with a small effect size (2–6⁰). |

Abbreviations: FAIS (femoroacetabular impingement syndrome), HAGOS (Copenhagen hip and groin outcome score), iHOT (International Hip Outcome Tool), NRS (numeric rating scale), RCT (randomized controlled trial).

Most studies scored in the fair to good range for overall quality/risk of bias (SUPPLEMENTAL FILE 4). The highest risk of bias was related to external validity because the majority of studies exclusively recruited patients from tertiary care, subspecialty surgical clinics. Lack of randomization was also a frequent limitation in study quality due to the prospective, single-arm nature of many of the studies. The certainty of synthesized evidence ranged from moderate to very low (SUPPLEMENTAL FILE 5).

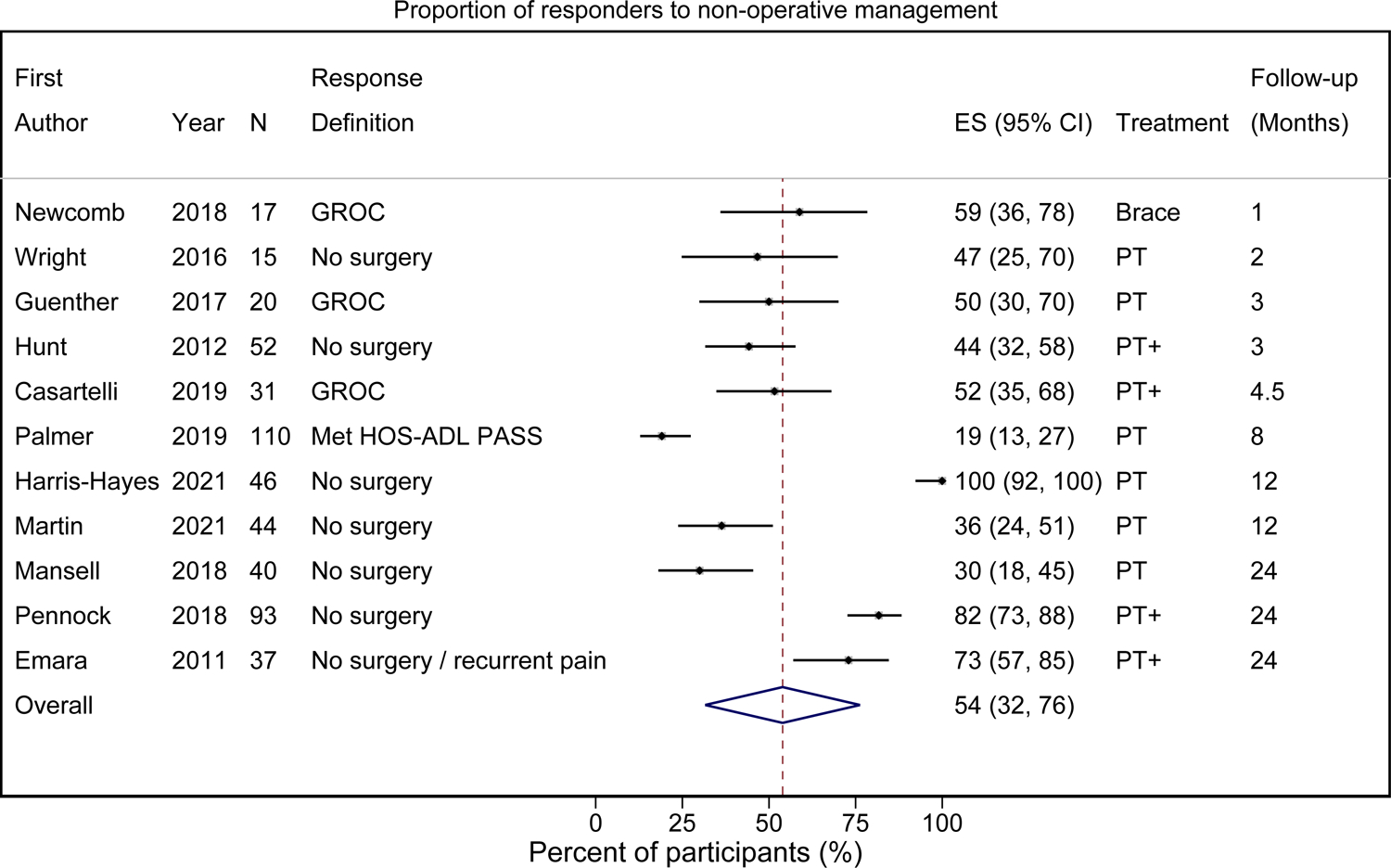

Rate of response to non-operative management (meta-analysis):

Eleven studies (13 treatment arms) categorized patients as responders versus non-responders to non-operative management, either by self-report on a patient-reported measure or by reporting no surgery during the follow-up interval and/or no recurrence of pain.6,12,18,21,27,37,39,45,48,49,59 All but one study included physical therapy as a treatment component, and four studies specifically evaluated a comprehensive non-operative management protocol which included multiple elements such as physical therapy, activity modification education, oral anti-inflammatory medications, and/or intra-articular corticosteroid injection on an as-needed basis. Fifty-four percent [95% CI 32% to 76%] of patients satisfactorily responded to non-operative treatment, with follow-up durations ranging from 1 to 24 months (FIGURE 2) (moderate certainty of evidence). Two of the three studies that reported 24-month outcomes evaluated comprehensive, multi-faceted treatment protocols, and they reported the second and third highest response rates of all the studies included in the meta-analysis (82% in Pennock et al., n=93; 73% in Emara et al., n=37).12,49 Zogby et al. reported the longest overall follow-up duration of five years. This study was not included in the meta-analysis because it reported longer term follow-up data from the same participants described in Pennock et al., but the five-year response rate in Zogby et al. was still 72% (50/69).61

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of the rate of satisfactory response to non-operative management in patients with non-arthritic hip-related pain. I2 = 98.0%, p < 0.001.

Abbreviations: ES (effect size), GROC (global rating of change), HOS-ADL (Hip Outcome Score – Activities of Daily Living), PASS (Patient Acceptable Symptom State), PT (physical therapy).

“PT+” indicates the non-operative management protocol included physical therapy plus other elements (e.g., scheduled oral anti-inflammatory medication, intra-articular injection as indicated on a per-patient basis, etc.).

Effect size (ES) represents the percent of participants who met criteria to be classified as a responder to non-operative management.

P-value refers to the Mantel-Haenszel method to assess for heterogeneity.

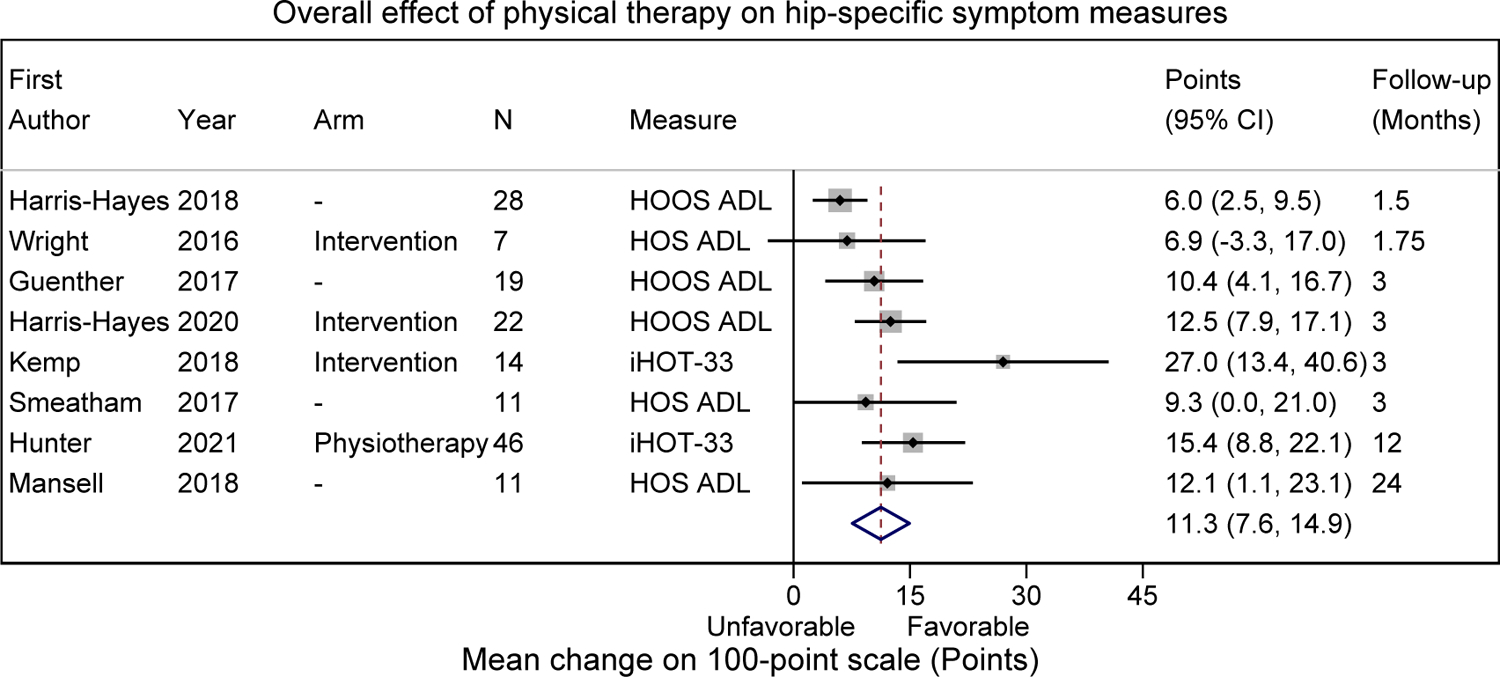

Physical therapy (meta-analysis):

Hip-specific symptoms:

Eight of the 21 studies describing physical therapy protocols reported data that could be meta-analyzed.3,6,12,13,15,17,18,20–23,27,28,31,38,44,48,49,54,59,61 With the exception of Guenther et al.,18 all studies eligible for meta-analysis were randomized controlled trials, many of which were pilot feasibility trials. The mean change on hip-specific symptom measures after physical therapy was 11.3 points [7.6 to 14.9 points] on 100-point measures, with follow-up durations ranging from 1.5 months to 2 years (FIGURE 3) (low-to-moderate certainty of evidence). In comparison, with the exception of the nine-participant Grant et al. study,15 all studies that could not be included in the meta-analysis also reported a positive effect from physical therapy, with longitudinal mean differences ranging from 3 to 26.2 points on 100-point hip-specific symptom measures. Three studies are noteworthy because of their large sample sizes: the Personalized Hip Therapy arm from a randomized controlled trial by Griffin et al. (n=177) reported a mean improvement in iHOT-33 scores by 14.1 points at 12 months,17 the “physiotherapy and activity modification arm” from a randomized controlled trial by Palmer at al. (n=110) reported a mean improvement in HOS-ADL scores by 3.5 points at 8 months,48 and patients who followed a graded non-operative treatment protocol in a prospective cohort study by Pennock et al. (n=93) reported a mean improvement of 21 points on the modified Harris Hip Score and 13 points on the Non-Arthritic Hip Score at 2-year follow-up.49

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot of the mean change in hip-specific patient-reported symptom measures in response to physical therapy for non-arthritic hip-related pain. I2 = 53.8%, p = 0.034.

Abbreviations: ADL (Activities of Daily Living), HOOS (Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score), HOS (Hip Outcome Score), iHOT (International Hip Outcome Tool).

P-value refers to the Mantel-Haenszel method to assess for heterogeneity.

Effects of specific physical therapy-related treatment components:

None of the sub-group meta-analyses of the hip-specific functional outcomes produced statistically different longitudinal changes based on testable characteristics of the physical therapy regimen (TABLE 2) (very low to low certainty evidence). However, when compared to treatment protocols that lasted six weeks, protocols that included a 10–12 week duration of formal physical therapy had a 7.4 point greater improvement on 100-point hip-specific symptom measures. All other sub-group meta-analyses demonstrated between-group longitudinal changes of 4.2 points or less. These included comparison of physical therapy protocols that did versus did not include specific treatment components related to flexibility exercise, movement pattern training, and/or joint or soft tissue mobilization. Two study arms included flexibility exercise or movement pattern training.22,23,38

TABLE 2.

Summary of effect sizes from sub-group meta-analyses of the mean change in hip-specific, patient-reported symptom measures in response to physical therapy related treatments for hip-related pain.

| Intervention cohort | Comparison cohort | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention component | Intervention | N (Studies / Patients) | Mean change (Points) | [95% CI] | Comparison | N (Studies / Patients) | Mean change (Points) | [95% CI] | Between-group difference in mean change (Points) | p |

| Duration of PTa | 10–12 weeks | 4 / 101 | 14.0 | [9.5 to 18.5] | 6 weeks | 3 / 46 | 6.6 | [3.4 to 9.8] | 7.4 | .58 |

| Flexibility exerciseb | Yes | 2 / 57 | 14.5 | [8.8 to 20.2] | No | 6 / 101 | 10.5 | [6.2 to 14.8] | 4.0 | .80 |

| Movement pattern trainingb | Yes | 2 / 50 | 9.1 | [2.7 to 15.4] | No | 6 / 108 | 12.7 | [8.3 to 17.1] | −3.6 | .80 |

| Mobilizationb | Yes | 5 / 89 | 13.5 | [7.9 to 19.2] | No | 3 / 69 | 9.3 | [5.0 to 13.7] | 4.2 | .81 |

Abbreviations: PT (physical therapy).

One original study (Smeatham 2017) did not indicate the duration of formal physical therapy.

”Yes” indicates the study treatment included this intervention component with or without other intervention components. “No” indicates the study treatment did not include this intervention component.

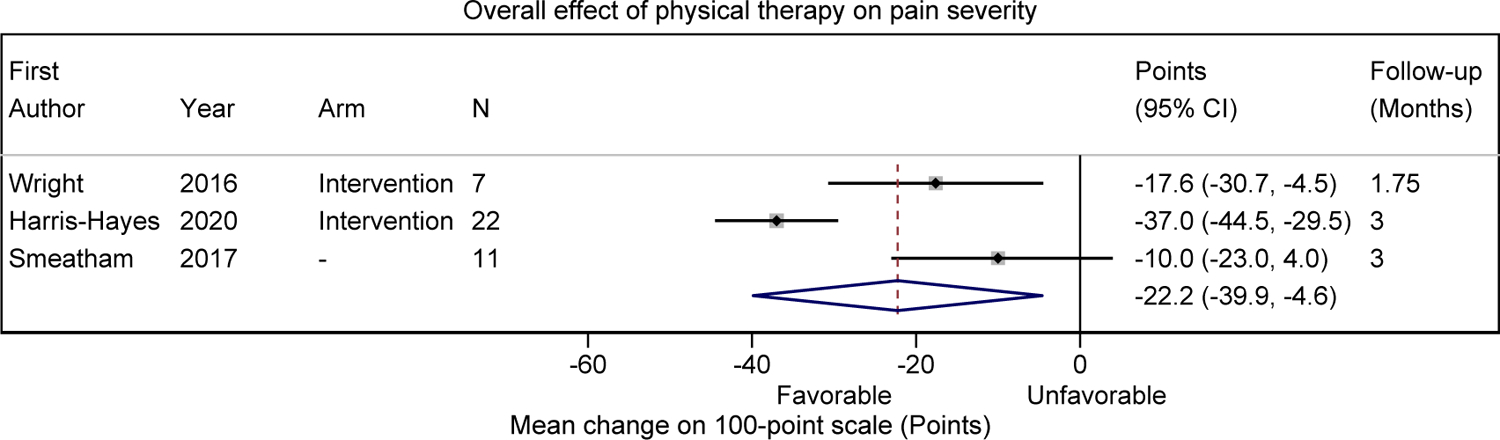

Pain severity:

Three studies reported data on patient-reported pain severity that could be pooled.22,54,59 The mean change in patient-reported pain severity from physical therapy was a 22.2 point improvement [4.6 to 39.9 points] on 100-point measures, with follow-up durations ranging from 1.75 to 3 months (FIGURE 4) (low certainty evidence). Sub-group analyses were not performed because of the few number of eligible studies.

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of the mean change in patient-reported pain severity in response to physical therapy for non-arthritic hip-related pain. I2 = 86.5%, p = 0.001.

Pain severity patient-reported outcomes included the visual analog scale and the numeric pain rating scale. As needed, 10-point scales were transformed to 100-point scales.

P-value refers to the Mantel-Haenszel method to assess for heterogeneity.

Injections (qualitative synthesis):

Viscosupplementation:

Three studies were identified.1,35,47 All three investigated hyaluronic acid derivatives, but injection frequency and total quantity varied among the studies. Patients who received at least one injection reported improved hip pain and, to a lesser degree, hip function and reduced anti-inflammatory oral medication use (very low to low certainty of evidence). Improvements were reported as early as two weeks and, in some cases, up to twelve months post-injection.

Corticosteroid:

One of the viscosupplementation related studies also had a corticosteroid study arm (Lee at al.).35 In the per-protocol reporting of this modified cross-over study, patients who received only an intra-articular corticosteroid injection reported comparable pain improvements but somewhat attenuated functional improvements at two weeks, when compared to patients who only received a viscosupplementation injection (very low certainty of evidence). These improvements with corticosteroid injection lasted up to twelve weeks. Statistical significance of between- and within-group differences was not stated, as these were not predetermined study outcomes. Furthermore, at the two-week follow-up point, 37.5% (6/16) of patients in the corticosteroid arm elected to cross over into the viscosupplementation arm and were therefore not included in the twelve-week outcomes reported above.

Orthobiologics:

No eligible studies were identified that assessed the effectiveness of orthobiologic intra-articular injections (e.g., platelet rich plasma, mesenchymal stem cells, etc.) for hip-related pain outside the context of intra-operative injection during concomitant hip arthroscopy.

Bracing (qualitative synthesis):

The effect of a hip brace in people with FAIS and/or a labral tear was evaluated in two studies (very low to low certainty evidence).13,45 Eyles et al. examined use of a Hip Unloader brace for six weeks and found statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in pain and function. However, almost half of participants only wore the brace for 1–2 hours per day and reported discomfort with the brace.13 Newcomb et al. examined use of a Stability through External Rotation of the Femur (SERF) strap for four weeks and found that over half of patients reported at least moderate improvements in pain and/or function on a global rating of change scale, but no significant change on mean pain or function scores were observed across the entire cohort.45

Medications and psychological management (qualitative synthesis):

No studies assessed the effectiveness of oral medications or psychological interventions for patients with hip-related pain.

DISCUSSION

We identified 26 randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies that evaluated the effectiveness of non-operative treatment for patients with non-arthritic hip-related pain. Physical therapy was the focus of 21 of these studies, the majority of which were of fair to good quality. Meta-analysis of 11 studies, which involved a variety of treatment components, resulted in an overall 54% [95% CI 32% to 76%] response rate to non-operative treatment (moderate certainty evidence). The overall effect of physical therapy was an 11.3 point improvement [7.6 to 14.9 points] on 100-point patient-reported hip symptom measures (low-to-moderate certainty) and a 22.2 point improvement [4.6 to 39.9] on 100-point pain severity measures (low certainty).

The largest effect observed from a specific component of physical therapy was a 7.4 point greater improvement in patient-reported hip symptom measures among studies that involved physical therapy of 10–12 weeks duration when compared to 6 weeks duration. Very low to low certainty evidence indicated symptomatic benefit from intra-articular viscosupplementation and corticosteroid injections. Symptom relief was reported as early as 2 weeks after both types of injections and as late as 12 weeks after corticosteroid injection and 12 months after viscosupplementation. Very low certainty evidence also suggested small effect sizes in pain, function, and biomechanics with use of a hip brace to stabilize and/or unload the hip joint. No eligible studies evaluated the use of orthobiologic injection outside an operative setting, oral medication, or psychological intervention.

Comparison to prior literature

The pooled non-operative response rate of 54% is comparable to a recent retrospective analysis of over 700 patients (800 hips) in which 52% proceeded to surgery after a minimum one-year follow-up.8 Of course, variability of effect sizes across individual studies is likely in part related to the specific patient population (e.g., age, baseline activity level, previous treatments tried, etc.), treatment protocol, outcome measure of each study (e.g., reaching an acceptable symptom state48 versus deciding against proceeding with surgery49), and perceptions of indications for surgery.5 For instance, Pennock et al., Emara et al., and Zogby et al. reported three of the best response rates despite having the longest follow-up durations of all included studies (i.e., two to five years). These studies involved a multi-faceted, stepwise approach to non-operative treatment which included relative rest followed by physical therapy and specific instruction in activity modification (e.g., activities to ideally avoid, and modifications to body mechanics if avoiding an activity is not possible or not preferred) prior to considering surgical intervention.12,49,61 We hypothesize this multi-faceted approach contributed to the high non-operative response rate in these studies.

The improvement of 11.3 points on hip function from physical therapy approximates or exceeds published minimal clinically important changes on the hip-specific patient-reported symptom measures reported in the studies that were meta-analyzed, despite the known ceiling effects of HOOS-ADL and HOS-ADL.32 Previously reported meaningful changes after hip preservation surgery include 6 to 10.8 points on HOOS-ADL, 5 to 9.7 points on HOS-ADL, and 10 points on iHOT-33.32,46,57 Similarly, pooled mean improvement of 22.2 points on 100-point pain severity scales from physical therapy exceeds the minimal clinically important change of 14.8 points and approaches the substantial clinical benefit threshold of 25.5 points.4

Clinical implications

While surgical management for hip-related pain is certainly beneficial and necessary for some patients, this synthesis identifies persistent knowledge gaps regarding optimal non-operative treatment, which represent potential opportunities to continue improving outcomes. We advocate for working toward a personalized medicine approach in which clinicians identify the right treatment (and/or combination of treatments) for a particular patient, rather than focusing exclusively on identifying the right treatment for a particular hip disorder. Based on the lack of clear superiority of any particular element of physical therapy over another, such a personalized medicine approach may need to involve identifying subgroups of patients with particular patterns of bony morphology and movement patterns that respond best to specific types of physical therapy.5,55 Similarly, as opposed to equating physical therapy alone as analogous to comprehensive non-operative treatment, a multi-faceted non-operative treatment approach should address a patient’s biomechanical imbalances (through physical therapy), inflammation and biochemical contributors (through oral and/or injectable medications outside the operative setting), and psychosocial contributors.9,50,52

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to report the rate of response to non-operative management for non-arthritic hip-related pain. We reported effect sizes on 100-point scales that are easily relatable to practitioners who are accustomed to using 100-point patient-reported hip symptom measures. We synthesized the existing evidence for non-operative treatment options other than physical therapy and for patients with hip-related pain from disorders other than FAIS.14,25,33,36,40,56 Additionally, unlike recent reviews, which compared treatment groups within studies, we harnessed the power of meta-analysis to pool treatment groups between studies.25 Whereas within-study comparisons may be biased toward positive effects consistent with the original authors’ hypotheses, this approach facilitates investigation of treatment effects that were not necessarily the original authors’ focus.10,58

Nevertheless, our data synthesis was limited by the available literature. There was substantial variability in the level of evidence (e.g., randomized controlled trials versus cohort studies), quality of study reporting (e.g., description of the patient population, treatment protocol, etc.), assessment of fidelity of treatment delivery, and outcomes assessed (e.g., use of hip-related domains with varied quality of psychometric properties). Furthermore, even within the defined subcategories of physical therapy, treatment protocols varied notably between studies (e.g., flexibility exercises with emphasis of stretching into hip external rotation and extension versus instructions for flexibility exercises into hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation; inclusion versus exclusion of treatment options aside from physical therapy; etc.).12,38

Given the limited number of original studies available, it was also not possible to control for these additional variables or for interactions between variables of interest using meta-regression. Despite attempts to contact original study authors, we were not able to obtain error terms necessary for meta-analysis from a few of the original studies, including from two of the largest randomized controlled trials that have been conducted on this population to date.17,48 Even still, the effect sizes reported in these studies were within range of the overall effect sizes of the meta-analyses performed, although the rate of response to non-operative treatment may be under-estimated in this synthesis because most patients in the original studies were recruited from surgical clinics within tertiary care institutions rather than from more traditional “first points of care” (e.g., general practitioner, physical therapist, etc.).48 Use of the Cochrane risk of bias assessments (i.e., RoB 2 for randomized controlled trials and ROBINS-I for non-randomized studies) may have suggested overall higher risk of bias than our adapted Downs and Black checklist, which may have better reflected these limitations of the primary literature.24

CONCLUSION

One in 2 patients with non-arthritic hip-related pain reported satisfactory response to non-operative management. There were clinically meaningful improvements in hip function and pain after physical therapy treatment, but insufficient evidence was available to make definitive recommendations regarding: 1.) the optimal duration, supervision level, or treatment components of physical therapy; or 2.) the effectiveness of intra-articular viscosupplementation, corticosteroid injection, orthobiologic injection outside an operative setting, bracing, oral medications, or management of coexisting psychological distress. This synthesis was limited by the quantity, quality, and heterogeneity of existing evidence, and future studies could impact these findings.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Findings:

Over half of patients with non-arthritic hip-related pain report satisfactory response to non-operative treatment, even among those who present to a tertiary care institution. The benefit of physical therapy for hip-related pain has been established, but insufficient evidence exists to determine the essential elements of comprehensive non-operative management for hip-related pain.

Implications:

A focused course of non-operative management should likely be considered for most patients with hip-related pain before deciding to proceed with surgical intervention. Based on the lack of clear superiority of any particular element of physical therapy over another, a personalized medicine approach may need to involve identifying subgroups of patients with particular patterns of bony morphology and movement patterns that respond best to specific types of physical therapy.

Caution:

This synthesis was limited by the variable risk of bias and heterogeneity of clinical outcomes assessed in the primary literature. Although this study provides clinically relevant preliminary estimates of what patients with non-arthritic hip-related pain can expect from non-operative management, the rate of response to non-operative management may still be under-estimated because most patients in the original studies were recruited from surgical clinics within tertiary care institutions, rather than from more traditional “first points of care.”

Acknowledgments

Grant support for this study was provided by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) (Cheng, Grant K23AR074520), the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (Cheng), and the Foundation for Physical Therapy Research Paris Patla Musculoskeletal Research Grant (Harris-Hayes).

Footnotes

The authors report no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Institutional ethical approval was not required, as no individually identifiable data were collected on humans or animals for this systematic review.

This study protocol was preregistered on Prospero (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) under number CRD42019133620.

Data Sharing:

All data relevant to this study are included in the article or related supplementary files.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abate M, Scuccimarra T, Vanni D, Pantalone A, Salini V. Femoroacetabular impingement: Is hyaluronic acid effective? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. Apr 2014;22(4):889–92. 10.1007/s00167-013-2581-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annin S, Lall AC, Yelton MJ, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in athletes following hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement with sub-analysis on return to sport and competition level: A systematic review. Arthroscopy. Apr 19 2021; 10.1016/j.arthro.2021.03.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aoyama M, Ohnishi Y, Utsunomiya H, et al. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial comparing conservative treatment with trunk stabilization exercise to standard hip muscle exercise for treating femoroacetabular impingement: A pilot study. Clin J Sport Med. Nov 16 2017; 10.1097/jsm.0000000000000516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck EC, Nwachukwu BU, Kunze KN, Chahla J, Nho SJ. How can we define clinically important improvement in pain scores after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome? Minimum 2-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. Oct 11 2019:363546519877861. 10.1177/0363546519877861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown-Taylor L, Pendley C, Glaws K, et al. Associations between movement impairments and function, treatment recommendations, and treatment plans for people with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. Phys Ther. Sep 1 2021;101(9) 10.1093/ptj/pzab157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casartelli NC, Bizzini M, Maffiuletti NA, et al. Exercise therapy for the management of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: Preliminary results of clinical responsiveness. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). Aug 21 2018; 10.1002/acr.23728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casartelli NC, Maffiuletti NA, Valenzuela PL, et al. Is hip morphology a risk factor for developing hip osteoarthritis? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. Jun 23 2021; 10.1016/j.joca.2021.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng AL, Collis RW, McCullough AB, et al. Rate of continued conservative management versus progression to surgery at minimum one year follow-up in patients with pre-arthritic hip pain. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. Dec 11 2021; 10.1002/pmrj.12746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng AL, Schwabe M, Doering MM, Colditz GA, Prather H. The effect of psychological impairment on outcomes in patients with prearthritic hip disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of sports medicine. 2019:363546519883246–363546519883246. 10.1177/0363546519883246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colditz GA, Brewer TF, Berkey CS, et al. Efficacy of bcg vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis. Meta-analysis of the published literature. JAMA. Mar 2 1994;271(9):698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. Jun 1998;52(6):377–84. 10.1136/jech.52.6.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emara K, Samir W, Motasem el H, Ghafar KA. Conservative treatment for mild femoroacetabular impingement. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). Apr 2011;19(1):41–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eyles JP, Murphy NJ, Virk S, et al. Can a hip brace improve short-term hip-related quality of life for people with femoroacetabular impingement and acetabular labral tears: An exploratory randomized trial. Clin J Sport Med. Sep 8 2021; 10.1097/jsm.0000000000000974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fairley J, Wang Y, Teichtahl AJ, et al. Management options for femoroacetabular impingement: A systematic review of symptom and structural outcomes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. Oct 2016;24(10):1682–96. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant LF, Cooper DJ, Conroy JL. The hapi ‘hip arthroscopy pre-habilitation intervention’ study: Does pre-habilitation affect outcomes in patients undergoing hip arthroscopy for femoro-acetabular impingement? Journal of hip preservation surgery. Jan 2017;4(1):85–92. 10.1093/jhps/hnw046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffin DR, Dickenson EJ, O’Donnell J, et al. The warwick agreement on femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (fai syndrome): An international consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. Oct 2016;50(19):1169–76. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffin DR, Dickenson EJ, Wall PDH, et al. Hip arthroscopy versus best conservative care for the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (uk fashion): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. Jun 2 2018;391(10136):2225–2235. 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31202-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guenther JR, Cochrane CK, Crossley KM, Gilbart MK, Hunt MA. A pre-operative exercise intervention can be safely delivered to people with femoroacetabular impingement and improve clinical and biomechanical outcomes. Physiother Can. 2017;69(3):204–211. 10.3138/ptc.2016-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. Grade guidelines: A new series of articles in the journal of clinical epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. Apr 2011;64(4):380–2. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris-Hayes M, Czuppon S, Van Dillen LR, et al. Movement-pattern training to improve function in people with chronic hip joint pain: A feasibility randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. Jun 2016;46(6):452–61. 10.2519/jospt.2016.6279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris-Hayes M, Steger-May K, A MB, Mueller MJ, Clohisy JC, Fitzgerald GK. One-year outcomes following physical therapist-led intervention for chronic hip-related groin pain: Ancillary analysis of a pilot multicenter randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Res. Jan 17 2021; 10.1002/jor.24985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris-Hayes M, Steger-May K, Bove AM, et al. Movement pattern training compared with standard strengthening and flexibility among patients with hip-related groin pain: Results of a pilot multicentre randomised clinical trial. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine. 2020;6(1):e000707. 10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris-Hayes M, Steger-May K, Van Dillen LR, et al. Reduced hip adduction is associated with improved function after movement-pattern training in young people with chronic hip joint pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. Mar 16 2018:1–28. 10.2519/jospt.2018.7810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JPT HJ, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Second ed. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoit G, Whelan DB, Dwyer T, Ajrawat P, Chahal J. Physiotherapy as an initial treatment option for femoroacetabular impingement: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials. The American journal of sports medicine. 2019:363546519882668–363546519882668. 10.1177/0363546519882668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hooper P, Jutai JW, Strong G, Russell-Minda E. Age-related macular degeneration and low-vision rehabilitation: A systematic review. Can J Ophthalmol. Apr 2008;43(2):180–7. 10.3129/i08-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunt D, Prather H, Harris Hayes M, Clohisy JC. Clinical outcomes analysis of conservative and surgical treatment of patients with clinical indications of prearthritic, intra-articular hip disorders. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. Jul 2012;4(7):479–87. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunter DJ, Eyles J, Murphy NJ, et al. Multi-centre randomised controlled trial comparing arthroscopic hip surgery to physiotherapist-led care for femoroacetabular impingement (fai) syndrome on hip cartilage metabolism: The australian fashion trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. Aug 16 2021;22(1):697. 10.1186/s12891-021-04576-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iorio A, Spencer FA, Falavigna M, et al. Use of grade for assessment of evidence about prognosis: Rating confidence in estimates of event rates in broad categories of patients. BMJ. Mar 16 2015;350:h870. 10.1136/bmj.h870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang C, Hwang DS, Cha SM. Acetabular labral tears in patients with sports injury. Clin Orthop Surg. Dec 2009;1(4):230–5. 10.4055/cios.2009.1.4.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kemp JL, Coburn SL, Jones DM, Crossley KM. The physiotherapy for femoroacetabular impingement rehabilitation study (physiofirst): A pilot randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. Apr 2018;48(4):307–315. 10.2519/jospt.2018.7941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kemp JL, Collins NJ, Roos EM, Crossley KM. Psychometric properties of patient-reported outcome measures for hip arthroscopic surgery. Am J Sports Med. Sep 2013;41(9):2065–73. 10.1177/0363546513494173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kemp JL, Mosler AB, Hart H, et al. Improving function in people with hip-related pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of physiotherapist-led interventions for hip-related pain. Br J Sports Med. May 6 2020; 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korakakis V, Whiteley R, Tzavara A, Malliaropoulos N. The effectiveness of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in common lower limb conditions: A systematic review including quantification of patient-rated pain reduction. Br J Sports Med. Mar 2018;52(6):387–407. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee YK, Lee GY, Lee JW, Lee E, Kang HS. Intra-articular injections in patients with femoroacetabular impingement: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, cross-over study. J Korean Med Sci. Nov 2016;31(11):1822–1827. 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mallets E, Turner A, Durbin J, Bader A, Murray L. Short-term outcomes of conservative treatment for femoroacetabular impingement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Sports Phys Ther. Jul 2019;14(4):514–524. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mansell NS, Rhon DI, Marchant BG, Slevin JM, Meyer JL. Two-year outcomes after arthroscopic surgery compared to physical therapy for femoracetabular impingement: A protocol for a randomized clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. Feb 04 2016;17:60. 10.1186/s12891-016-0914-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mansell NS, Rhon DI, Meyer J, Slevin JM, Marchant BG. Arthroscopic surgery or physical therapy for patients with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: A randomized controlled trial with 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. Feb 1 2018:363546517751912. 10.1177/0363546517751912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin SD, Abraham PF, Varady NH, et al. Hip arthroscopy versus physical therapy for the treatment of symptomatic acetabular labral tears in patients older than 40 years: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. Apr 2021;49(5):1199–1208. 10.1177/0363546521990789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGovern RP, Martin RL, Kivlan BR, Christoforetti JJ. Non-operative management of individuals with non-arthritic hip pain: A literature review. Int J Sports Phys Ther. Feb 2019;14(1):135–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muffly BT, Zacharias AJ, Jochimsen KN, Duncan ST, Jacobs CA, Clohisy JC. Age at the time of surgery is not predictive of early patient-reported outcomes after periacetabular osteotomy. J Arthroplasty. May 25 2021; 10.1016/j.arth.2021.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murata Y, Fukase N, Martin M, et al. Comparison between hip arthroscopic surgery and periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of patients with borderline developmental dysplasia of the hip: A systematic review. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine. May 2021;9(5):23259671211007401. 10.1177/23259671211007401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murata Y, Uchida S, Utsunomiya H, Hatakeyama A, Nakamura E, Sakai A. A comparison of clinical outcome between athletes and nonathletes undergoing hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement. Clin J Sport Med. Jul 2017;27(4):349–356. 10.1097/jsm.0000000000000367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murtha AS, Bomar JD, Johnson KP, Upasani VV, Pennock AT. Acetabular labral tears in the adolescent athlete: Results of a graduated management protocol from therapy to arthroscopy. J Pediatr Orthop B. Nov 1 2021;30(6):549–555. 10.1097/bpb.0000000000000793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Newcomb NRA, Wrigley TV, Hinman RS, et al. Effects of a hip brace on biomechanics and pain in people with femoroacetabular impingement. J Sci Med Sport. Oct 03 2017; 10.1016/j.jsams.2017.09.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nwachukwu BU, Beck EC, Kunze KN, Chahla J, Rasio J, Nho SJ. Defining the clinically meaningful outcomes for arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome at minimum 5-year follow-up. The American journal of sports medicine. 2020;48(4):901–907. 10.1177/0363546520902736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ometti M, Schipani D, Conte P, Pironti P, Salini V. The efficacy of intra-articular hyadd4-g injection in the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: Results at one year follow up. Journal of drug assessment. Nov 17 2020;9(1):159–166. 10.1080/21556660.2020.1843860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palmer AJR, Ayyar Gupta V, Fernquest S, et al. Arthroscopic hip surgery compared with physiotherapy and activity modification for the treatment of symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement: Multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. Feb 7 2019;364:l185. 10.1136/bmj.l185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pennock AT, Bomar JD, Johnson KP, Randich K, Upasani VV. Nonoperative management of femoroacetabular impingement: A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. Nov 6 2018:363546518804805. 10.1177/0363546518804805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prather H, Creighton A, Sorenson C, et al. Anxiety and insomnia in young- and middle-aged adult hip pain patients with and without femoroacetabular impingement and developmental hip dysplasia. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. Oct 27 2017; 10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reiman MP, Agricola R, Kemp JL, et al. Consensus recommendations on the classification, definition and diagnostic criteria of hip-related pain in young and middle-aged active adults from the international hip-related pain research network, zurich 2018. Br J Sports Med. 2020:bjsports-2019–101453. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Richard HM, Nguyen DC, Podeszwa DA, De La Rocha A, Sucato DJ. Perioperative interdisciplinary intervention contributes to improved outcomes of adolescents treated with hip preservation surgery. J Pediatr Orthop. May/Jun 2018;38(5):254–259. 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwabe MT, Clohisy JC, Cheng AL, et al. Short-term clinical outcomes of hip arthroscopy versus physical therapy in patients with femoroacetabular impingement: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine. Nov 2020;8(11):2325967120968490. 10.1177/2325967120968490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smeatham A, Powell R, Moore S, Chauhan R, Wilson M. Does treatment by a specialist physiotherapist change pain and function in young adults with symptoms from femoroacetabular impingement? A pilot project for a randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy. Jun 2017;103(2):201–207. 10.1016/j.physio.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Dillen LR, Norton BJ, Sahrmann SA, et al. Efficacy of classification-specific treatment and adherence on outcomes in people with chronic low back pain. A one-year follow-up, prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Man Ther. Aug 2016;24:52–64. 10.1016/j.math.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wall PD, Fernandez M, Griffin DR, Foster NE. Nonoperative treatment for femoroacetabular impingement: A systematic review of the literature. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. May 2013;5(5):418–26. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wasko MK, Yanik EL, Pascual-Garrido C, Clohisy JC. Psychometric properties of patient-reported outcome measures for periacetabular osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Mar 20 2019;101(6):e21. 10.2106/jbjs.18.00185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson ME, Fineberg HV, Colditz GA. Geographic latitude and the efficacy of bacillus calmette-guérin vaccine. Clin Infect Dis. Apr 1995;20(4):982–91. 10.1093/clinids/20.4.982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wright AA, Hegedus EJ, Taylor JB, Dischiavi SL, Stubbs AJ. Non-operative management of femoroacetabular impingement: A prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial pilot study. J Sci Med Sport. Sep 2016;19(9):716–21. 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wylie JD, Peters CL, Aoki SK. Natural history of structural hip abnormalities and the potential for hip preservation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. Jun 22 2018; 10.5435/jaaos-d-16-00532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zogby AM, Bomar JD, Johnson KP, Upasani VV, Pennock AT. Nonoperative management of femoroacetabular impingement in adolescents: Clinical outcomes at a mean of 5 years: A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. Aug 6 2021:3635465211030512. 10.1177/03635465211030512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]