Abstract

Protein kinases play a major role in cellular activation processes, including signal transduction by diverse immunoreceptors. Given their roles in cell growth and death and in the production of inflammatory mediators, targeting kinases has proven to be an effective treatment strategy, initially as anticancer therapies, but shortly thereafter in immune-mediated diseases. Herein, we provide an overview of the status of small molecule inhibitors specifically generated to target protein kinases relevant to immune cell function, with an emphasis on those approved for the treatment of immune-mediated diseases. The development of inhibitors of Janus kinases that target cytokine receptor signalling has been a particularly active area, with Janus kinase inhibitors being approved for the treatment of multiple autoimmune and allergic diseases as well as COVID-19. In addition, TEC family kinase inhibitors (including Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors) targeting antigen receptor signalling have been approved for haematological malignancies and graft versus host disease. This experience provides multiple important lessons regarding the importance (or not) of selectivity and the limits to which genetic information informs efficacy and safety. Many new agents are being generated, along with new approaches for targeting kinases.

Subject terms: Immunosuppression, Molecular medicine

Drugs that target protein kinases have had a major impact on the treatment of cancer and now are proving beneficial in numerous immunological diseases. This Review describes their clinical application, with a focus on Janus kinase inhibitors, and how they inform mechanisms of disease and have evolved to improve efficacy and safety.

Introduction

The extraordinary advances in the basic science of immunology have provided therapeutic approaches that have revolutionized outcomes in patients with inflammatory and immune-mediated diseases1,2. These include numerous successful therapeutic monoclonal antibodies and engineered recombinant cytokine receptors. Advances in deciphering the biochemical pathways of immune cell signalling3,4 similarly led to the generation of small molecule therapies that complement biologics. In this Review, we focus on protein kinase inhibitors and their use in immune-mediated and inflammatory disorders. Although this field has been reviewed numerous times5,6, it moves extraordinarily quickly, with over 60 small molecule protein kinase inhibitors now approved and hundreds more in development6. We provide a brief history of targeted kinase inhibitors, which first emerged for the treatment of cancer. We then discuss how purposefully targeting signal transduction pathways used by major classes of immunoreceptors has led to the effective treatment of numerous immune-mediated disorders. We focus on Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors as they comprise one of the most active and successful areas, but we also review the successful targeting of TEC family kinases and other emerging protein kinase drug targets. We compare the ways in which kinase inhibitors may be similar yet distinct from biologics targeting cells and cytokines, and we consider future approaches and opportunities in this field.

Overview of protein kinases

Reversible protein phosphorylation by kinases and phosphatases is a fundamental cellular regulatory mechanism, important for controlling protein activity during key cellular processes such as cell cycle, cell growth, differentiation, movement, metabolism and apoptosis7,8. Phosphorylation by protein kinases converts signals from outside the cell to downstream readouts within the cell by facilitating protein interactions and translocation and by altering protein conformations. These changes lead to modification of downstream enzymes, specific gene transcription and protein degradation8. The actions of protein kinases are reversed by protein phosphatases.

The human genome contains more than 518 protein kinases, comprising 1.7% of human genes, as well as an additional 20 lipid kinases9. Protein kinases, also known as phosphotransferases, catalyse the transfer of the γ-phosphate from a purine nucleotide triphosphate (that is, ATP and GTP) to the hydroxyl groups of their protein substrates by generating phosphate monoesters using protein alcohol groups (on serine and threonine residues) and/or protein phenolic groups (on tyrosine residues) as phosphate acceptors. Thus, protein kinases can be classified by the amino acid substrate preference: serine–threonine kinases, tyrosine kinases and dual kinases (which phosphorylate serine, threonine or tyrosine residues). Protein tyrosine kinases make up around 10% of the total kinase family and are often involved in proximal receptor signalling. Almost all protein kinases have catalytic domains that belong to a single eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily.

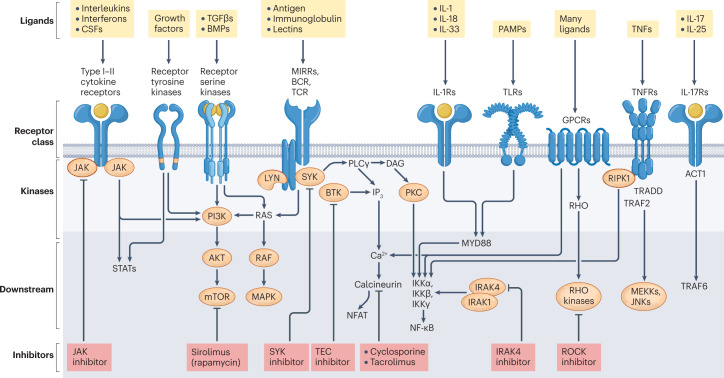

T cells, B cells and innate immune cells express different classes of cytokine receptors and multichain immune recognition receptors (including T cell receptors (TCRs), B cell receptors (BCRs), Fc receptors (FcRs) for IgG, natural killer (NK) cell receptors and C-type lectin receptors) that use phosphorylation to trigger the first steps of activation or are linked to kinases via adaptor molecules (Fig. 1). The main kinases involved in immune cell signalling include: receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), receptor serine kinases, non-RTKs such as the JAKs and the SRC, SYK and TEC family of tyrosine kinases, as well as a larger group of downstream serine–threonine kinases7,10,11 (Fig. 1). RTKs and receptor serine kinases have intrinsic phosphotransferase activity induced by ligand binding, whereas many immune receptors including antigen receptors and cytokine receptors lack this intrinsic enzyme activity and recruit cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases. For example, JAKs are noncovalently associated with cytokine receptors and phosphorylate both the receptor and signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) to induce gene expression. Engagement of antigen receptors induces rapid activation of SRC family kinases, leading to the recruitment and activation of SYK in B cells and ZAP70 in T cells, which phosphorylate downstream adaptor molecules that recruit TEC family kinases and phospholipase Cγ. Activated phospholipase Cγ cleaves membrane-bound phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate into inositol trisphosphate, which induces Ca2+ mobilization and activation of calcineurin and diacylglycerol, which activates protein kinase C, RAS and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Together, with signals from co-stimulatory molecules, these cascades activate nuclear factor of activated T cells, nuclear factor-κB and AP-1 transcription factors, along with phosphoinositide 3-kinase, mTOR and AKT pathways. It is notable that some intermediates in the signalling cascades of different receptors are shared and others are distinct (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Major kinase classes and immunoreceptor signalling.

Key immune receptors expressed by T cells, B cells and innate immune cells include different classes of cytokine receptors and multichain immune recognition receptors. Only a subset of downstream pathways are shown, which are relevant to the inhibitors discussed in this Review. The prominent kinases involved in immune receptor signalling include: receptor tyrosine kinases, receptor serine kinases, non-receptor tyrosine kinases such as the Janus kinases (JAKs) and the SRC (such as LYN), SYK and TEC (such as BTK) families of tyrosine kinases, as well as the larger group of downstream serine–threonine kinases. These are represented here with ligands, receptor classes, kinases and key downstream signalling cascades. BCR, B cell receptor; BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; BTK, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; CSF, colony-stimulating factor; DAG, diacylglycerol; GPCR, G-protein-coupled receptor; IKKα, inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB kinase subunit-α; IKKβ, inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB kinase subunit-β; IKKγ, inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB kinase subunit-γ; IRAK, IL-1 receptor-associated kinase; JNK, JUN N-terminal kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEKK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; MIRR, multichain immune recognition receptor; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; MYD88, myeloid differentiation primary response 88; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cells; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PKC, protein kinase C; PLCγ, phospholipase Cγ; RIP, receptor-interacting serine–threonine protein kinase; ROCK, RHO-associated protein kinase; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase; TCR, T cell receptor; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; TNFR, tumour necrosis factor receptor; TRADD, tumour necrosis factor receptor type 1-associated death domain; TRAF, TNFR-associated factor.

Some kinases have selective expression in immune cells, but many kinases are broadly expressed; although the former would represent logical targets to develop new therapies for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, inhibitors of kinases with broad expression also turn out to be safe and effective drugs6,10.

Targeting kinases: in the beginning

Many oncogenes and their cellular counterparts are kinases; thus, interfering with pathological phosphorylation in cancer seemed a logical treatment strategy12. However, given how ubiquitous protein kinases are for critical cellular functions and the conservation of the ATP-binding region across kinase classes, there was also reasonable skepticism about whether specificity could be attained with kinase inhibitors. We now know that despite structural similarities of protein tyrosine kinases in their ATP-bound active state, structural differences in the inactive conformation and gatekeeper residues in kinase domains allow for the development of selective protein kinase inhibitors6,10. The first inhibitors of protein phosphorylation were not purposefully designed to do so (Box 1). In addition, there are opportunities beyond targeting kinase domains, including allosteric inhibitors and targeted protein degradation (discussed subsequently).

Box 1 The first inhibitors of protein phosphorylation.

Inhibitors of calcineurin (cyclosporin and tacrolimus) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR, rapamycin) were the first drugs found to alter lymphocyte signalling via protein phosphorylation, yet they were not purposefully developed to do so. Nonetheless, they have provided useful lessons for the use of signalling inhibitors.

Cyclosporin is a cyclic peptide that was isolated in 1970 from a soil fungus on the basis of its antifungal activity. However, it was later found to have immunosuppressive function171 and, since its approval in 1983, it has been highly valuable in preventing rejection in allograft transplantation172 and is also used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Similarly, tacrolimus (also known as FK506) was isolated from a soil sample, a soil bacteria product, and found to have potent immunosuppressive properties, and is now harnessed for the management of allograft transplantation173, atopic dermatitis and multiple autoimmune diseases174,175. Both drugs inhibit calcineurin, a calcium and calmodulin-dependent serine–threonine phosphatase that is activated by increased cytoplasmic calcium. Calcineurin dephosphorylates nuclear factors of activated T cells, which allow their translocation to the nucleus and transcriptional activity175. Nuclear factors of activated T cells are activated by many immune receptors, including T cell receptors, B cell receptors, Fc receptors for IgG and G-protein-coupled receptors, and are critical for multiple aspects of immune cell activation including the expression of cytokines176. As a result, cyclosporin and tacrolimus affect many diverse pathways and cells. Inhibition of calcineurin occurs via the generation of two immunophilin–immunosuppressant complexes: cyclophilin A–cyclosporin and FK506-binding protein (FKBP12)–tacrolimus177.

Rapamycin (also known as sirolimus) is another product of soil bacteria that was initially isolated for its antifungal activity. Subsequent characterization showed that it had immunosuppressive and antiproliferative properties via inhibition of mTOR complex 1 (ref. 178). Rapamycin is an approved therapy for allograft transplantation, although it has proved to be less effective in cancer178,179.

These drugs have multiple effects on T cell signalling, as well as in other cells. For example, in T cells, both the T cell receptor and cytokine receptors for IL-2 family members activate mTOR to promote T cell survival, activation, migration and proliferation in response to infection or inflammatory stimulation. Thus, T cells stimulated in the presence of rapamycin are less able to proliferate and express lower levels of inflammatory cytokines180. Exposure to rapamycin is also associated with an increase in regulatory T cells expressing FOXP3 (ref. 181), which represents another means by which rapamycin can limit immunopathology.

Despite the effectiveness of calcineurin inhibitors, these drugs are limited by renal toxicity and are associated with hypertension and neurological toxicity. By contrast, rapamycin is not associated with renal toxicity, making it an attractive agent for the treatment of kidney transplantation182. Although rapamycin and tacrolimus bind to the same target protein, they also inhibit unrelated signalling pathways allowing them to be used in combination183. High blood levels of mTOR inhibitors lead to myelosuppression and are associated with hyperlipidaemia and type 2 diabetes, consistent with the role of mTOR in the regulation of metabolism184.

Although these drugs were not isolated on the basis of their effects on protein phosphorylation, their clinical success highlights the powerful potential of phosphorylation-based signalling inhibitors as a therapeutic strategy. Notably, both calcineurin and mTOR are ubiquitously expressed and deletion of mTOR in mice is lethal185, and therefore, they would not be considered obvious choices for useful therapies. Yet, calcineurin inhibitors remain our most effective drugs in transplantation medicine, which highlights the caveat that patterns of expression and knockout mice are not necessarily always reliable guides to useful drugs. Furthermore, the mechanism of action for these drugs is unusual as befits their biological origins; both calcineurin and mTOR are part of multiprotein complexes and the drugs do not directly target the catalytic domain or subunit of the kinase175,177,180,181 (further discussed in the text).

ABL kinases

Selective targeting of a kinase was first accomplished in the early 2000s with the approval of imatinib for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) (Fig. 2), a major advance that moved away from broadly cytotoxic agents to more targeted therapy for molecular abnormalities of cancer13,14. Imatinib selectively targets the fusion protein BCR–ABL tyrosine kinase generated by a chromosomal translocation associated with most cases of CML15,16. Imatinib was developed from the lead compound 2-phenylaminopyrimidine and modified by the introduction of methyl and pyridyl groups to confer enhanced selectivity and inhibitory activity against ABL kinases. The addition of an N-methyl-piperazine enhanced the aqueous solubility and oral bioavailability of imatinib17.

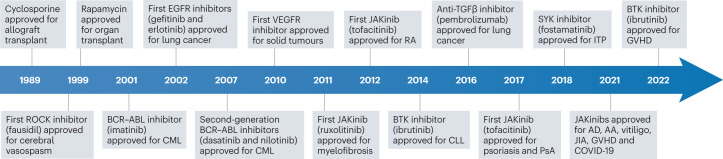

Fig. 2. Timeline of approval of key protein kinase inhibitor drugs for cancer and immune-mediated disease.

The timeline lists the year of approval and indication, starting with the approval of cyclosporine for allograft transplantation (in 1989) to the approvals of JAK inhibitors (JAKinibs) for immune-mediated diseases to date. AA, alopecia areata; AD, atopic dermatitis; BCR, B cell receptor; BTK, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukaemia; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; GVHD, graft versus host disease; ITP, immune thrombocytopenia; JAK, Janus kinase; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; ROCK; RHO-associated kinase; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

The successful use of imatinib is associated with a reduction in the proportion of BCR–ABL cells in the bone marrow. In many cases, the response to treatment lasts for decades18–20. However, resistance to imatinib can develop and is typically associated with the acquisition of mutations of the ABL kinase domain that alter binding of imatinib21. Second-generation ABL kinase inhibitors (nilotinib and dasatinib) were introduced to address imatinib resistance22,23 (Fig. 2). Notably, dasatinib has less specificity for ABL compared with imatinib and has activity against SRC family kinases but is conversely more tolerant of mutations in the ABL kinase domain. Third-generation inhibitors (ponatinib and bosutinib) were then developed to overcome the ABL T315I mutation, which confers resistance to previous generations of ABL kinase inhibitors24.

In the immune system, imatinib has effects on lymphocytes, mast cells and macrophages, inhibiting signal transduction pathways that lead to the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines25. In addition to its role in several haematological malignancies, late-phase clinical studies of imatinib have been initiated for the treatment of COVID-19, pulmonary hypertension and pain with sickle cell anaemia19. In these cases, imatinib appears to reverse capillary leak. In COVID-19, hypoxaemic respiratory failure owing to capillary leak and alveolar oedema is a major complication; experimental and early clinical data suggest that imatinib helps to reverse this process. In vitro models suggest that imatinib limits arginine-mediated endothelial barrier dysfunction by enhancing RAC1 activity and enforcing adhesion of endothelial cells to the extracellular matrix26. In sickle cell disease, imatinib appears to protect the integrity of the erythrocyte membrane (NCT03997903).

Receptor tyrosine kinases

Although targeting BCR–ABL kinase activity is an effective therapy for CML with minimal side effects, we now know that imatinib targets kinases beyond BCR–ABL, including RTKs, and has utility beyond this setting. In haematopoietic cells, imatinib targets the stem cell factor RTK (KIT) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFRα), which are key oncogenic drivers in most gastrointestinal stromal cell tumours27. Imatinib has revolutionized the treatment of this disorder and is now the first-line therapy, despite never having undergone prospective clinical trials. Mutations in KIT and PDGFRα are also seen in several rare myeloproliferative diseases such as systemic mastocytosis, hypereosinophilic syndrome and/or chronic eosinophilic leukaemia28. In a meta-analysis of published case reports, imatinib was shown to be the most widely used therapy for these conditions after corticosteroids29.

Another PDGFR inhibitor is nintedanib, which also inhibits about 20 other kinases, including fibroblast growth factor receptors, vascular endothelial growth factor receptors30, colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) and the SRC family kinase LCK31. Nintedanib is approved for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis32; it inhibits the release of multiple cytokines by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells or T cells. Nintedanib appears to decrease uncontrolled proliferation of lung fibroblasts and differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, which deposit extracellular matrix into the interstitial spaces in these diseases33. Data indicate that nintedanib prevents pro-fibrotic macrophage polarization and expression of the macrophage polarization marker CCL18, which has been associated with disease progression34.

CSF1R is expressed in monocytes, tissue-resident macrophages, dendritic cells and osteoclasts and is activated by macrophage CSF1 and IL-34. Mutations affecting CSF1R are seen in 10% of cases of histiocytosis, a rare group of clonal, often localized, myeloproliferative disorders that include Erdheim–Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis subtypes35. The presence of these mutations leads to robust cytokine-independent cell growth in vitro. CSF1R signalling has also been implicated in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and graft versus host disease (GVHD). In RA, CSF1R is highly expressed by proliferating fibroblast-like synoviocytes, suggesting a role in proliferation of these cell types36. In amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, CSF1R has a role in the invasion of macrophages into peripheral nerves37. In GVHD, CSF1R-expressing macrophages from donors infiltrate the skin, leading to cutaneous inflammation38. The CSF1R antagonist antibody axatilimab has completed small phase I/II clinical trials for the treatment of chronic GVHD that are resistant to multiple lines of therapy and has shown some promise39. By contrast, the small molecule CSF1R inhibitor edicotinib was not efficacious in RA40.

Structurally similar to RTKs are receptor serine–threonine kinases41, which are discussed in Box 2.

Box 2 Emerging kinase targets.

With hundreds of kinases as potential targets, kinase inhibitor discovery likely provides many new opportunities for treating immune-mediated diseases. Here we highlight a selection of kinase targets with potential for the treatment of immune-mediated diseases.

Serine–threonine receptor kinases belong to a large family that includes receptors for ligands such as transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) cytokines. TGFβ has broad roles in innate and adaptive immunity186–188, and it also participates in fibrosis and the production of extracellular matrix. The TGFβ receptor kinase inhibitors vactosertib (EW-7197) and galunisertib (LY2157299) have been used to treat cancers189,190, and galunisertib is approved for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (EMA, Canada). The small molecule pirfenidone, which is also licensed for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, acts in part through its ability to inhibit TGFβ production191. Similarly, an inhibitor of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (nintedanib) may also interfere with TGFβ receptor signalling, which may be important for its therapeutic effects in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis192.

IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4) is an essential signal transducer downstream of receptors for IL-1 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) family cytokines, as well as Toll-like receptors (TLRs). IRAK4 deficiency in humans is linked to susceptibility to pyogenic bacterial infections193,194, but this susceptibility tends to decrease with age and adults affected by IRAK4 deficiency are not particularly susceptible to viral, parasitic or fungal infections, which supports the potential use of IRAK4 inhibitors in the clinic195. Indeed, multiple IRAK4 inhibitors have been developed and tested in preclinical models196,197. These inhibitors include zimlovisertib (PF-06650833) and zabedosertib (BAY1834845), which are being investigated in multiple immune-mediated diseases and haematological malignancy, and BAY1830939 is now being tested in phase I trials of safety for inflammatory diseases (NCT05003089).

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are a large family of kinases, downstream of virtually all immune receptors198,199. Three main MAPK cascades have been identified in mammalian cells — the ERK (extracellular-signal-regulated kinase) cascade, the JNK (JUN N-terminal kinase) cascade and the p38 MAPK cascade200. Targets of treatments have been ERK kinase and BRAF proteins in the ERK pathway. BRAF inhibitors (such as vemurafenib and dabrafenib) or combination BRAF/MEK inhibitors have been approved and used in histiocyte-mediated disease as well as in cancers such as melanoma associated with BRAF mutations201–203 (Table 2), without an increase in the frequency of infections204. In keeping with this perceived lack of immunosuppression, inhibitors of the ERK and JNK cascades have not been used in inflammatory disease. By contrast, the p38 MAPK cascade was one of the earliest targets considered for the treatment of inflammatory disease205. The cascade is important for driving macrophage expression of TNF and IL-1. However, all attempts at bringing a small molecule inhibitor of p38 MAPK to clinic have so far failed owing to either a lack of efficacy or toxicity.

Besides p38 MAPK, an irreversible, covalent inhibitor of MAPK-activated protein kinase 2, known as CC-99677, is being studied in a phase I trial (NCT03554993) for potential use in ankylosing spondylitis and other inflammatory diseases206. An inhibitor (tilpisertib) of MAP3K8, which is downstream of TLRs and TNF receptor5, was studied in ulcerative colitis but the study was terminated because “a new molecular entity was able to achieve greater target coverage” (NCT04130919).

Receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) and RIPK3 are downstream of TNF receptor signalling and thus have been explored as targets for TNF-mediated inflammatory diseases, such as ulcerative colitis (NCT02903966). However, development of the RIPK1 inhibitor SAR443060 (DNL747) was discontinued owing to long-term non-clinical toxicology findings.

Inhibitors of RHO kinases and of other related family members are another group of targets with approved efficacy and emerging potential. RHO and RAC kinases are downstream of many different receptor complexes in immune and non-immune cells, including G-protein-coupled receptors and antigen receptors207,208. Belumosudil is an inhibitor of RHO-associated coiled–coiled containing protein kinase 2 (ROCK2) that is approved for the treatment of chronic graft versus host disease and is reported to reduce the production of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-21, IL-17 and interferon-γ209. It is also being studied in systemic sclerosis.

TANK-binding kinase 1 is involved in innate immune responses involving IL-1, IL-18, IL-33 and IL-17, as well as in TLR signalling and induction of type I interferons210; selective TANK-binding kinase 1 inhibitors are being developed211. Pharmacological inhibition of TGFβ-activated kinase 1212 has also been found to be efficacious in preclinical models of inflammation, consistent with its role in TNF-induced signalling.

Salt-inducible kinases are a subfamily of AMP-activated protein kinases that can be activated by G-protein-coupled receptors, and salt-inducible kinase inhibitors have been reported to block the production of cytokines and chemokines213. Serine–threonine protein kinase SGK1 is related to AKT and has been proposed to have potential use not only in cancer but also in fibrosis and graft versus host disease214. Dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A may also be a useful target for modulating T helper cell differentiation, given evidence suggesting that it acts at the branch point between commitment to either the regulatory T cell or T helper 17 cell lineage215,216.

JAK family kinase inhibitors

Although targeting a single cytokine or cytokine receptor has revolutionized therapy for immune-mediated diseases, this approach is not successful in all patients and often does not result in durable remission42. Therefore, it is not surprising that targeting signalling pathways shared by multiple cytokine receptors with small molecules became an attractive and extremely successful approach. As such, we focus on studies of JAKs as key pharmaceutical targets for immune-mediated and inflammatory diseases.

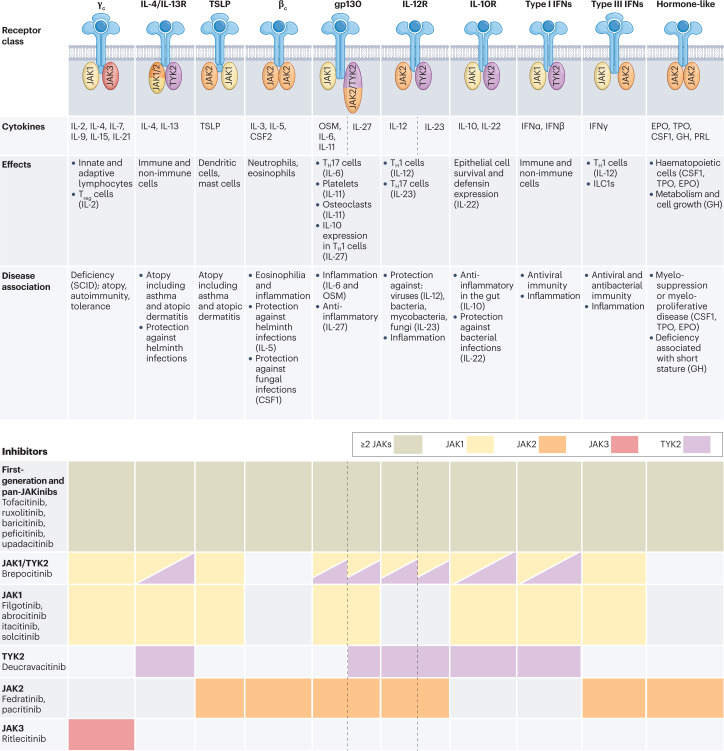

JAKs (comprising JAK1, JAK2, JAK3 and TYK2) associate with receptors for type I and II cytokines that lack intrinsic RTK activity, inducing downstream cell signalling for multiple cell functions43 (Fig. 3). Of the JAK family members, JAK1 is activated by the largest number of type I and II cytokines, including type I interferons (IFNs), IFNγ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-13 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin; JAK2 is activated by erythropoietin, thrombopoietin, growth hormone, IL-3, IL-5, IL-12, IL-23, CSF1 and CSF2 (Fig. 3). Moreover, most cytokine receptors require the use of more than one JAK. The essential function of JAKs has been established by identifying genetic variants in patients and by the generation of knockout mice44–47 (Table 1). Specifically, gene targeting of Jak1 and Jak2 in mice is lethal;48 JAK1 and JAK2 are essential for signalling downstream of many cytokines that impact processes in multiple tissues and cells including haematopoiesis, host defence, immunoregulation, body growth and metabolism. JAK1 loss-of-function mutations cause primary immunodeficiency in humans associated with atypical mycobacterial infection, whereas JAK1 gain-of-function mutations are associated with systemic immune dysregulation and hypereosinophilic syndrome47. Somatic JAK2 gain-of-function mutations are associated with three common myeloproliferative neoplasms: primary polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia and primary myelofibrosis, consistent with the role of the JAK2-associated haematopoietic cytokines erythropoietin, thrombopoietin and CSFs45. Loss-of-function mutations of TYK2 in humans and mice are also associated with immunodeficiency characterized by increased susceptibility to bacterial, viral and fungal infections46, reflecting its importance for signalling by IFNs, IL-10 family cytokines, IL-12, IL-23 and IL-27. JAK3 loss-of-function mutations result in severe combined immunodeficiency, owing to the disruption of signalling by receptors containing the common γ-chain (for γc cytokines IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9 and IL-21)44. These phenotypes highlight the relatively limited functions of TYK2 and JAK3 versus the broad actions JAK1 and JAK2; the spectrum of cytokines impacted is relevant for the mechanism of action, efficacy and adverse events of JAK inhibitors (JAKinibs).

Fig. 3. Cytokines and receptor classes, their immunological effects, disease association and corresponding Janus kinase inhibitors.

The receptor class, specific Janus kinases (JAKs) and associated cytokines are grouped by functional and immunological effects and disease associations. JAK inhibitors (JAKinibs) are listed from the less-selective first-generation JAKinibs and panJAKinibs (at the top) to the more selective JAKinibs (at the bottom). CSF, colony-stimulating factor; EPO, erythropoietin; GH, growth hormone; gp130, glycoprotein 130; IFN, interferon; ILC, innate lymphoid cell; OSM, oncostatin M; PRL, prolactin; SCID, severe combined immunodeficiency; TH1 cell, T helper 1 cell; TH17 cell, T helper 17 cell; TPO, thrombopoietin; Treg cell, regulatory T cell; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin.

Table 1.

Genetic phenotypes associated with kinases

| Knockout phenotype | Mendelian disorders | Somatic GOF mutations | Links from GWAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JAK1 | Perinatal lethality; impaired responses to type I, II and III IFNs, γc cytokines, IL-10, IL-13, IL-27, TSLP and gp130 family cytokines |

LOF: mycobacterial disease, warts, parasitic and fungal infection; progressive T cell lymphopenia; increased IgG and IgA levels GOF: atopy and autoimmunity |

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and acute myeloid leukaemia | JIA, MS, autoimmune thyroid disease and acute myeloid leukaemia; increased CRP levels; increased lymphocyte and eosinophil counts; body mass and height |

| JAK2 | Embryonic lethal; absence of definitive haematopoiesis; impaired responses to γc cytokines, TSLP, gp130, leptin, prolactin, EPO, TPO, CSF1, IFNγ, IL-12, IL-13 and IL-23 | Myeloproliferative neoplasms: polycythemia vera, post-essential thrombocythemia, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, acute myeloid leukaemia and chronic myelogenous leukaemia | SLE, allergy, AD, AS, RA, T1D, psoriasis and IBD; cholesterol level; eosinophil, basophil, platelet and erythrocyte counts; body height | |

| JAK3 | Defective T and B cell development; impaired responses to γc cytokines: IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15 and IL-21; immunodeficiency | LOF: SCID (T and NK cell deficiency) | Myeloproliferative neoplasms, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, myelomonocytic leukaemia, NK cell lymphoma or leukaemia and T cell lymphoma or leukaemia | |

| TYK2 | Bacterial and viral infection; impaired responses to type I IFNs, IL-12, IL-23, IL-27 and IL-10 | LOF: mycobacterial disease and infections with other bacteria and viruses | SLE, RA, JIA, psoriasis, AS, IBD, MS, T1D, T2D and COVID-19; mycobacterial susceptibility; platelet and lymphocyte counts | |

| BTK | X-linked immunodeficiency: mildly impaired B cell development; impaired T cell-independent type 2 responses, but normal T cell-dependent responses to immunization; low IgM and IgG3; resistance to polymicrobial sepsis169 | LOF: X-linked agammaglobulinaemia; severe B cell developmental block and pan-hypoglobulinaemia; bacterial and severe enteroviral infections | LOF seen in lymphomas | |

| ITK | Altered T cell development; mature T cell defects; poor in vivo TH2 cell responses and resistance to allergic asthma; resistance to EAE and GVHD | LOF: T cell immunodeficiency, EBV-associated lymphoproliferation; other viral infections | ITK–SYK fusion t(5;9)(q33;q22) in peripheral T cell lymphoma170 | Asthma and MS; eosinophil counts |

| IRAK4 | Reduced or absent superoxide production after impaired priming and activation of the oligomeric neutrophil NADPH oxidase; decreased LPS-induced and fMLP-induced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK | LOF: immunodeficiency; invasive pneumococcal disease, recurrent isolated (beginning in infancy or early childhood); recurrent infections with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus | Hypermorphic IRAK4 found in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myelogenous leukaemia | Breast cancer; increased susceptibility to Gram-positive infection; decreased response to TLR ligands |

| SYK | High rates of perinatal lethality; abnormal vascular morphology and osteoclast differentiation; impaired neutrophil phagocytosis; defects in B cell development | GOF: immunodeficiency with systemic inflammation, characterized by recurrent infections and non-infectious inflammation, manifests as lymphocytic organ infiltration, gastritis, colitis and lung, liver, CNS or skin disease; lymphoma later in life | Solid tumours, particularly colon cancer | MS, SLE and Alzheimer disease |

AD, atopic dermatitis; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; BTK, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; CNS, central nervous system; CRP, C-reactive protein; CSF1, colony-stimulating factor 1; EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalitis; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; EPO, erythropoietin; fMLP, N-formylmethionine-leucyl-phenylalanine; GOF, gain of function; gp130, glycoprotein 130; GVHD, graft versus host disease; GWAS, genome-wide association studies; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IFN, interferon; IRAK, IL-1 receptor-associated kinase; ITK, IL-2-inducible T cell kinase; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; LOF, loss of function; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MS, multiple sclerosis; NK, natural killer; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SCID, severe combined immunodeficiency; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TPO, thrombopoietin; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Mechanisms of action of JAKinibs in immune-mediated disease

First-generation JAKinibs block both JAK1 and JAK2. Consequently, in GVHD, JAKinibs can attenuate allogeneic donor T cell activation by blocking the action of IFNs in promoting antigen presentation as well as the action of many effector cytokines49,50. JAKinibs impact diseases mediated by type 1 (IFNγ-driven), type 2 (IL-4-driven, IL-5-driven or IL-13-driven) or type 3 (IL-17-driven or IL-22-driven) immune responses (Fig. 3), with effects on both innate and adaptive immune cells, as well as on non-immune cells, stromal cells and neurons, as targeted cytokine receptors are expressed by virtually all cells. Both type 1 and type 2 immune responses are implicated in the pathological mechanisms of alopecia areata (AA)51,52; although the biologic dupilumab (anti-IL-4Rα, which blocks both IL-4 and IL-13) can be efficacious in some patients, it is not approved for AA53–55. Thus, the broader actions of JAKinibs may be advantageous for this autoimmune disorder. In skin obtained from mice and humans with alopecia, transcriptomic profiling revealed expression of IFN response signature genes and several γc cytokines including IL-2 and IL-15. Use of JAKinibs eliminates the IFN signature and development of alopecia in a mouse model, as well as induces near-complete hair regrowth in patients treated with the JAKinib ruxolitinib and multiple other JAKinibs56. In vitiligo, skin-resident memory T cells demonstrate skewed JAK1-dependent and JAK2-dependent type 1 and type 2 cytokine profiles that stimulate melanocyte and keratinocyte inflammatory responses, which can be inhibited by ruxolitinib57. Consistent with the expression of cytokine receptors on neurons, JAKinibs can also reduce pain and itch associated with inflammatory skin diseases58. In these examples, JAKinibs have the advantage over biologics that target a single mediator by blocking more than one of the canonical responses and potentially different endotypes of the disease.

Cytokines do not act in isolation but induce the expression of other cytokines; for example, IL-6 induces the JAK-independent pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1, IL-17 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF). Cells pretreated with JAKinibs and then activated by lipopolysaccharide and other Toll-like receptor ligands that induce IL-6 produce less IL-1 and TNF59. The IL-1R antagonist anakinra is efficacious in various autoinflammatory diseases, such as haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, pointing to a prominent role of IL-1. Thus, JAKinibs may be efficacious in these diseases via this indirect mechanism59,60. The capacity of first-generation JAKinibs to inhibit a wide variety of cytokines may be an important aspect of their efficacy (as illustrated by their efficacy in COVID-19; discussed subsequently), but this broader effect can make it difficult to link their efficacy with a single mechanism61.

First-generation approved JAKinibs

Ruxolitinib was the first JAKinib to be approved by the FDA for the treatment of myeloproliferative diseases: primary polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia and primary myelofibrosis (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Activating mutations of JAK2 are found in 50% (primary myelofibrosis) to 90% (primary polycythemia vera) of cases62–64 (Table 1); thus, ruxolitinib was originally designed as a JAK2 inhibitor. However, it was subsequently found to also inhibit JAK1. This dual targeting was initially seen as a limitation of the drug for these JAK2-mediated myeloproliferative diseases. However, patients with primary myelofibrosis have systemic symptoms, including night sweats and loss of appetite, that may be JAK1-dependent rather than JAK2-dependent65–67. Furthermore, ruxolitinib has now been licensed for the treatment of inflammatory diseases; its success in this setting is likely related to its ability to inhibit JAK1. Ruxolitinib is also now approved for the treatment of acute and chronic GVHD49,65,68. Topical ruxolitinib is used as a treatment for atopic dermatitis (AD) and vitiligo, potentially avoiding side effects associated with systemic use of this inhibitor69 (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Approved kinase inhibitor drugs for inflammatory diseases, malignancies and haematological disorders

| Drug class | Drug | Specificity | Inflammatory disease | Malignancy and haematological disorder |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABL | Dasatinib | ABL | None | CML, ALL |

| Imatinib | ABL | ASM, HES | CML, GIST | |

| Nilotinib | ABL | None | CML | |

| Ponatinib | ABL | None | Refractory CML | |

| Bosutinib | ABL | None | CML | |

| CSF1R | Edicotinib | CSF1R | None | GCT |

| Pexidartinib | CSF1R, FLT, KIT | None | GCT | |

| JAK | Abrocitinib | JAK1 | AD | None |

| Baricitinib | JAK1, JAK2 | RA, COVID-19, AA, AD | None | |

| Delgocitinib | Pan-JAK | AD (topical only, Japan) | None | |

| Deucravacitinib | TYK2 | Psoriasis | None | |

| Fedratinib | JAK2 | None | MF, PV, ET | |

| Filgotinib | JAK1 | RA (Europe, Japan), UC (Japan) | None | |

| Momelitinib | JAK1, JAK2 | None | MF | |

| Pacritinib | JAK2, FLT3 | None | MF | |

| Peficitinib | Pan-JAK | RA (Japan) | None | |

| Ruxolitinib | JAK1/JAK2 > TYK2 > JAK3 | GVHD, AD (topical only), vitiligo (topical only) | MF, PP, PRV, ET, PT | |

| Tofacitinib | JAK3/JAK1 > JAK2, TYK2 | RA, UC; PsA, AS, JIA (USA, Europe) | None | |

| Upadacitinib | JAK1 > JAK2 | RA; PsA, AD (USA, Japan); AS, UC (USA) | None | |

| MAPK | Vemurafenib | BRAF | None | Metastatic melanoma, Erdheim–Chester disease |

| Dabrafenib | BRAF | None | Metastatic melanoma | |

| ROCK | Belumosudil | ROCK2 | GVHD | None |

| Fasudil | ROCK1, ROCK2 | None | Cerebral vasospasm (Japan, China) | |

| RSK | Galunisertib | TGFβR | IPF (EU, Canada) | None |

| RTK | Nintedanib | PDGFR | ILD, IPF | None |

| SYK | Fostamatinib | SYK | ITP | None |

| TEC | Acalabrutinib | BTK | None | CLL/SLL, MCL |

| Ibrutinib | BTK, ITK | GVHD | CLL/SLL, MCL, MZL, WM | |

| Orelabrutinib | BTK | None | Relapsed/refractory MCL (China) | |

| Zanubrutinib | BTK | None | MCL, MZL, WM |

AA, alopecia areata; AD, atopic dermatitis; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASM, advanced systemic mastocytosis; BTK, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukaemia; CSF1R, colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor; ET, essential or post-essential thrombocytopenia; GCT, giant cell tumour; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumour; GVHD, graft versus host disease; HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome; ILD, interstitial lung disease; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; ITP, idiopathic thrombocytopenia; JAK, Janus kinase; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MCL, mantle-cell lymphoma; MF, myelofibrosis; MZL, marginal zone leukaemia; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; PP, primary polycythemia; PRV, polycythemia rubra vera; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PT, primary thrombocythemia; PV, pemphigus vulgaris; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; ROCK, RHO-associated coiled–coiled containing protein kinase; RSK, receptor serine kinase; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; SLL, small lymphocytic leukaemia; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase; TGFβR, transforming growth factor-β receptor; UC, ulcerative colitis; WM, Waldenström macroglobulinaemia.

Tofacitinib was the first FDA-approved JAKinib for an inflammatory disease70,71. It was originally intended to be a JAK3 inhibitor. Studies in mouse models and patients with severe combined immunodeficiency owing to γc cytokine and JAK3 deficiencies predicted that a specific JAK3 inhibitor would be a potent immunosuppressant, leading to profound T and NK cell lymphopenia and consequently an increased risk of infections72. Given the important role of IL-2 in maintaining FOXP3+ regulatory T cells, it was conceivable that loss of IL-2-induced signalling through the use of JAK3 inhibitors would exacerbate autoimmune disease73. However, tofacitinib is immunosuppressive without causing lymphopenia74, which may be related to its ability to inhibit JAK1 in addition to JAK3. Tofacitinib is now approved for the treatment of RA, psoriatic arthritis (PsA), ankylosing spondyloarthritis, ulcerative colitis and polyarticular course juvenile idiopathic arthritis70,71,75–78 (Table 2 and Figs. 2 and 3). Tofacitinib has shown promise as a therapy for dermatomyositis79; in particular, studies have demonstrated improved survival in patients with anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis with life-threatening interstitial lung disease80,81. Finally, children with gain-of-function STAT1 mutations or loss-of-function mutations in the STAT1 inhibitor SOCS1 have enhanced type 1 immune responses at the cost of loss of type 3 immunity, resulting in chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and splenomegaly. Tofacitinib blocks IFN signalling by inhibiting STAT1 activation and has been effective in treating these two conditions82,83. For a drug conceived from research on patients with primary immunodeficiency, it is gratifying to see its use in treating patients with inborn errors of immunity.

Baricitinib, a JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor, is approved for the treatment of RA, AD, AA and COVID-19 (Table 2 and Figs. 2 and 3). However, two phase III studies of baricitinib in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (NCT03616912 and NCT03616964) showed discordant results for the primary outcome measure84. There are ongoing studies using first-generation JAKinibs, including topical forms, in multiple other immune conditions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Kinase inhibitors in selected clinical trials for immune-mediated diseases

| Drug class | Drug name | Immune-mediated diseases | NCT identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABL | Dasatinib | Phase II: COVID-19 | 04830735 |

| Imatinib | Phase II: ARDS/COVID-19, MS | ARDS/COVID-19: 04794088, 04953052; COVID-19: 04346147; MS: 03674099 | |

| CSF1R | Axatilimab | Phase II: cGVHD, COVID-19 | cGVHD: 04710576, 03604692; COVID-19: 04415073 |

| BLZ945 | Phase II: ALS | 04066244 | |

| IRAK4 | Zabedosertib | Phase I: psoriasis | 03493269 |

| EVO101 | Phase II: AD (topical) | https://www.evommune.com/ | |

| Zimlovisertib | Phase II: COVID-19 | 04933799 | |

| Abrocitinib | Phase II: prurigo nodularis | 05038982 | |

| JAKs | AZD0449 | Phase I: asthma | 03766399, 04769869 |

| Baricitinib | Phase III: SLE, DM, JIA, uveitis, systemic JIA | SLE: 03843125, 03616964, 03616912; DM: 04972760; JIA: 03773965, 03773978; uveitis: 04088409; systemic JIA: 04088396 | |

| Phase II: GCA, PMR, vitiligo, CANDLE, SAVI, AGS, IIM, PG, T1D | GCA: 03026504; PMR: 04027101; vitiligo: 04822584; CANDLE: 04517253; SAVI: 04517253; AGS: 03921554, 04517253; IIM: 04208464; PG: 04901325; T1D: 04774224 | ||

| Brepocitinib | Phase III: AA, DM | AA: 04006457; DM: 05437263 | |

| Phase II: AA, CCCA, uveitis | AA: 03732807, 04517864; CCCA: 05076006; uveitis: 05523765 | ||

| Delgocitinib | Phase III: CHD | 05355818, 04872101, 05259722 | |

| Phase II: FFA | 05332366 | ||

| Deucravacitinib | Phase III: PsA | 04908202, 04908189 | |

| Phase II: CD, UC, SLE | CD: 04877990; UC: 04877990, 03934216, 04613518; SLE: 03920267 | ||

| ESK-001 | Phase II: psoriasis | 05600036 | |

| Filgotinib | Phase III: CD, UC | CD: 02914600, 02914561; UC: 02914522, 02914535, 05479058 | |

| Phase II: PsA, AS, CLE, SS | PsA: 03101670, 03926195; AS: 03117270, 03926195; CLE: 03134222; SS: 03100942 | ||

| Gusacitinib | Phase II: AD | 03728504 | |

| KL130008 | Phase II: AA | 05496426 | |

| Ifidancitinib | Phase II: AD (topical) | 03585296 | |

| NDI-03458 | Phase II: PsA, psoriasis | PsA: 05153148; psoriasis: 04999839 | |

| Nezulcitinib | Phase II: COVID-19 (inhaled) | 04402866 | |

| OST-122 | Phase II: UC | 04353791 | |

| Ritlecitinib | Phase III: AA | 03732807, 04006457 | |

| Phase II: RA | 04413617 | ||

| Ropsacitinib | Phase II: psoriasis, HS | Psoriasis: 03895372; HS: 04092452 | |

| Ruxolitinib |

Phase III: CHD (topical), COVID-19, HLH/MAS Phase II: HES, DLE, HS (topical) |

CHD: 05233410, 05219864; COVID-19: 04424056, 04362137; HLH/MAS: 04120090, 05137496 HES: 00044304; DLE: 04908280; HS: 04414514 |

|

|

Povorcitinib Tofacitinib |

Phase III: AS Phase III: HS Phase II: HS, PN, vitiligo Phase II: SSc, SS, uveitis, pouchitis, PMR, IIM, COVID-19 pneumonia |

03502616 HS: 05620823, 05620836 HS: 04476043, 03607487, 03569371; PN: 05061693 SSc: 03274076; SS: 05087589, 04496960; uveitis: 03580343; pouchitis: 04580277; PMR: 04799262; IIM: 05400889; COVID-19 pneumonia: 04332042, 04390061, 04750317, 04415151, 04412252 |

|

| Upadacitinib | Phase III: GCA, CD, PsA, JIA, RA, TA, UC | GCA: 03725202; CD: 03345836, 03345823, 03345849; PsA: 03104374; JIA: 03725007; TA: 04161898; UC: 03653026, 03006068 | |

| Phase II: HS, RA, AS, UC | HS: 04430855; RA: 02720523; AS: 03178487; UC: 02819635 | ||

| MAP3K8 | Tilpisertib | Phase II: UC | 04130919 |

| ROCK | Belumosudil | Phase II: SSc | 04680975 |

| Fasudil | Phase II: ALS | 03792490, 05218668 | |

| RTK | Nintedanib | Phase II: bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome | 03805477 |

| Phase III: COVID-19 pulmonary fibrosis | 04541680 | ||

| RIPK1 | DNL747 | Phase I: Alzheimer disease, ALS | Alzheimer disease: 03757325; ALS: 03757351 |

| GSK298772 | Phase II: UC | 02903966 | |

| SYK | Fostamatinib | Phase III: SARS pneumonia, COVID-19 | SARS pneumonia: 04629703, 04924660; COVID-19: 04629703, 04924660 |

| Phase II: HS | 05040698 | ||

| GSK2646264 | Phase I: SLE, urticaria | SLE: 02927457; urticaria: 02424799 | |

| Rilzabrutinib |

Phase III: ITP, PV Phase II: AD, asthma, chronic urticaria, IgG4-related disease, AIHA |

ITP: 04562766; PV: 03762265 AD: 05018806; asthma: 05104892; urticaria: 05107115; IgG4: 04520451; AIHA: 05002777 |

|

| TEC | Acalabrutinib | Phase III: COVID-19 | 04647669 |

| Phase II: peanut allergy, cGVHD, RA | Peanut allergy: 05038904; cGVHD: 04198922; RA: 02387762 | ||

| Branebrutinib | Phase III: RA, SLE, SS | 04186871 | |

| Evobrutinib | Phase III: MS | 04032158, 04338061, 04338022, 04032171 | |

| Phase II: RA, SLE | RA: 03233230; SLE: 02975336 | ||

| Fenebrutinib | Phase III: MS | 04586023, 04586010, 04544449 | |

| Phase II: urticaria, SLE | Urticaria: 03693625, 0317069; SLE: 02908100 | ||

| Ibrutinib | Phase II: food allergy | 03149315 | |

| JTE-051 | Phase II: psoriasis, RA | Psoriasis: 03358290; RA: 02919475 | |

| Orelabrutinib |

Phase II: ITP, MS Phase I/II: SLE |

ITP: 05020288, 05232149; MS: 04711148, 04305197 | |

| Tirabrutinib | Phase II: chronic urticaria | 04827589 | |

| Zanubrutinib | Phase II: COVID-19, ITP, lupus nephritis | COVID-19: 04382586; ITP: 05279872, 05214391, 05369377, 05369364; lupus nephritis: 04643470 |

AA, alopecia areata; AD, atopic dermatitis; AGS, Aicardi–Goutières syndrome; AIHA, autoimmune haemolytic anaemia; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; CANDLE, chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature; CCCA, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia; CD, Crohn’s disease; cGVHD, chronic graft versus host disease; CHD, chronic hand dermatitis; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CSF1R, colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor; DLE, discoid lupus erythematosus; DM, dermatomyositis; ET, essential or post-essential thrombocytopenia; FFA, frontal fibrosing alopecia; GCA, giant cell arteritis; GVHD, graft versus host disease; HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome; HLH, haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; HS, hidradenitis suppurative; IIM, idiopathic inflammatory myopathies; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; IRAK4, IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 4; ITP, idiopathic thrombocytopenia; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; MAS, macrophage activation syndrome; MS, multiple sclerosis; NCT, National Clinical Trial; PG, pyoderma gangrenosum; PMR, polymyalgia rheumatica; PN; prurigo nodularis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PV, pemphigus vulgaris; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RIPK1, receptor-interacting protein kinase 1; ROCK, a RHO-associated coiled–coiled containing protein kinase; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; SAVI, STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SS, Sjögren syndrome; SSc, systemic sclerosis; TA, Takayasu arteritis; T1D, type 1 diabetes; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Use of JAKinibs in COVID-19

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was noted that much of the lung pathology seen in critically ill patients developed in the weeks following clearance of virus, suggesting a role for cytokine-mediated tissue damage. Although it may seem counterintuitive to use an immunosuppressive drug in a viral infection, it was discovered that the corticosteroid dexamethasone reduced mortality in patients with COVID-19 requiring oxygen for ventilatory support85. Similarly, the potential use of JAKinibs in cytokine-mediated immunopathology was quickly appreciated on the basis of the proven efficacy in a preclinical model of sepsis and their immunosuppressive effects59. Besides its anti-inflammatory activity, baricitinib was reported to have antiviral activity by inhibiting numb-associated kinases and adaptor protein kinases that are required for viral entry and by decreasing IFN-mediated expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (refs. 86–88). On this basis, baricitinib was investigated for the treatment of COVID-19 (NCT04640168) and subsequently approved for use in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 requiring oxygen for ventilatory support89,90. At present, more patients have been treated with baricitinib for COVID-19 than all other indications combined. Other JAKinibs have shown efficacy in COVID-19 in smaller studies. For instance, in patients hospitalized with COVID-19-associated pneumonia (NCT04469914), tofacitinib treatment decreased risk of death or respiratory failure compared with placebo91. This efficacy in COVID-19, as well as some positive outcomes reported with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis60, suggests the potential use of JAKinibs in other scenarios associated with cytokine storm, such as septic shock. However, more research is needed to address the timing and context of JAKinib use in these clinical settings, including potential generation of parenteral JAKinibs.

Side effects of first-generation JAKinibs

Given the broad impact of JAKinibs on cytokine signalling and the phenotypes associated with genetic deletion of JAKs (Table 1), increased rates of infection were expected in individuals treated with JAKinibs. Indeed, increased infections, including serious and opportunistic infections, are seen in patients treated with JAKinibs. A retrospective observational study reviewing the World Health Organization database of adverse events associated with first-generation JAKinibs (ruxolitinib, tofacitinib and baricitinib) found an increased association with viral (herpes and influenza viruses), fungal and mycobacterial infections; varicella zoster virus infection and reactivation were significantly greater in patients treated with first-generation JAKinibs than in patients treated with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)92. The risk of infection is increased when JAKinibs are used at high doses or in combination with immunosuppressive drugs, as illustrated in early transplantation trials93. Increased risk of viral infections may be due to inhibition of IFN signalling and type 1 immune responses and reduced numbers of NK cells94.

Because first-generation JAKinibs target JAK2, which is activated downstream of receptors important in blood cell development such as the erythropoietin receptor, anaemia and other cytopenias can occur; typically, these are not limiting adverse events. Venous thromboembolism and hyperlipidaemia have also been observed with the use of JAKinibs, the latter is also associated with biologics that block IL-6 (refs. 95,96). The mechanisms and cytokines underlying increased risk of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism remain unclear.

In an open-label safety trial comparing tofacitinib with TNF inhibitors for the treatment of active RA with at least one cardiovascular risk factor, opportunistic infections, major adverse cardiovascular events, malignancy, venous thrombosis and all-cause death were greater in the tofacitinib group after median 4-year follow-up97. On the basis of these findings, the FDA added a warning for tofacitinib and other JAKinibs, highlighting these increased risks in the context of RA98. However, 95% confidence intervals for these hazard ratios extend below one, indicating that further study is needed. The lack of an untreated control group in this study further complicates interpretation of the study, making it unclear whether these differences are simply due to the relative efficacy of TNF inhibitors compared with JAKinibs in suppressing inflammation, or whether JAKinibs were associated with risk beyond that associated with disease.

A recent follow-up study found that the risk for malignancy associated with tofacitinib was highest among those with a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or significant cardiovascular risk, indicating some shared risk factors99. Inflammatory diseases such as RA are known to be associated with increased cardiovascular disease and cancer; controversy regarding these relative risks remains. Additional studies of long-term safety of tofacitinib showed increased risk for opportunistic infection, major adverse cardiovascular events and venous thrombosis, consistent with previous studies. These studies note that the increased cancer risk was stable over time100. In a post hoc analysis of patients with RA on tofacitinib with about 10 years of follow-up and dose changes at investigator discretion, safety data were similar between doses for multiple adverse effects, including varicella zoster viral infection, serious infections, deep vein thromboses and pulmonary embolism101. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology Task Force for RA treatment noted that, after failure of a conventional DMARD, a JAKinib may be considered after taking relevant risk factors into account. This recommendation was based on the absence of evidence for greater risk of tofacitinib versus TNF inhibitors in patients without risk factors. Notably, it cannot be excluded that other DMARDs would have similar risks if subjected to an outcome-based randomized controlled trial102.

In a small study assessing the impact of tofacitinib on vascular complications in SLE, surrogate vascular end points suggested that tofacitinib might reduce risk. Tofacitinib use was associated with reduced formation of neutrophil extracellular traps, which promote vascular disease in lupus103. Although the evidence is modest, ruxolitinib is associated with a reduced incidence of thrombosis in patients with myeloproliferative disease, a patient group with high incidence of thromboembolic disease104. This could be a property of ruxolitinib or more likely because JAK inhibition blocks the pro-thrombotic consequences of myeloproliferation.

Second-generation JAKinibs

JAKinibs have evolved in multiple ways since the first generation, with efforts to improve selectivity and pharmacokinetics such as prolonged half-life105. Several relatively selective JAK1 inhibitors have been generated (Fig. 3): upadacitinib is approved for RA, PsA, ankylosing spondyloarthritis, ulcerative colitis and AD; abrocitinib is approved for AD106 and filgotinib is approved in the European Union and Japan for RA (Table 2). Upadacitinib was reported to have greater selectivity for JAK1 versus JAK2 when compared with first-generation JAKinibs107, although not all assays support this selectivity. Upadacitinib use is still associated with anaemia, which may reflect a residual blockade of JAK2, as well as an increased risk of venous thrombosis. Abrocitinib can be associated with hyperlipidaemia, major adverse cardiovascular events, venous thromboembolism, varicella zoster virus infection and decreased platelet counts108. Abrocitinib can also be associated with cytopenias that may be related to JAK1 inhibition; the IL-6 family cytokines oncostatin M and IL-11 are both drivers of haematopoiesis and depend on JAK1 for signalling. Oncostatin M-deficient mice have impaired haematopoiesis109, and use of oncostatin M-blocking antibodies is associated with reduced blood cell counts in clinical trials110. There is still uncertainty regarding the degree of selectivity of these supposed JAK1 inhibitors and whether they still negatively impact haematological, clotting and cardiovascular risk. More data and investigation are required to definitively know whether there are significant differences between newer and older agents.

Compared with JAK1 and JAK2, TYK2 is used by a narrower spectrum of cytokine receptors, and thus TYK2 inhibitors would be expected to be beneficial in diseases mediated by type 1 IFNs, IL-12 and IL-23 (Fig. 3), consistent with reduced risk of autoimmunity in humans with TYK2 loss-of-function variants111 (Table 1). Selective TYK2 inhibitors include ropsacitinib (PF-06826647, an ATP competitor)112, deucravacitinib, TAK-279, VTX958 and ESK-001113; the latter four agents bind to the pseudokinase domain of TYK2, which is a novel approach that confers greater selectivity than approaches that rely on binding the kinase domain114. Deucravacitinib has recently been approved for the treatment of plaque psoriasis115 (Table 2). Phase II clinical trial studies show efficacy in PsA116 and SLE117. However, deucravacitinib was not efficacious in a phase II trial in inflammatory bowel disease, perhaps owing to inhibition of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10, IL-22 and IL-27. Although examination of larger patient cohorts will be needed, so far anaemias and hyperlipidaemia do not appear to be associated with deucravacitinib use. Infections, including varicella zoster virus infections, are associated with deucravacitinib use, but reportedly, inhibition of TYK2 preserves IFNλ signalling, which may provide residual antiviral activity118. Brepocitinib (PF-06700841) is a JAK1 and TYK2 inhibitor that has proved to be successful in phase III clinical trials for the treatment of severe AA119 and is currently being investigated in a phase II clinical trial for scarring alopecia (NCT05076006). A new TYK2 inhibitor, KL130008, is being studied in a phase II clinical trial for AA (NCT05496426).

JAK3 has the most restricted expression among the JAKs, and targeting JAK3 inhibits a limited number of cytokines (Fig. 3). In this respect, a JAK3-selective inhibitor could avoid haematological and cardiovascular complications. Decernotinib is reported be a selective JAK3 inhibitor that showed efficacy in RA, but its use is limited by multiple drug interactions. Decernotinib is metabolized by aldehyde oxidase to a metabolite that, in turn, inhibits CYP3A4, which is key for the inactivation of many common drugs120,121. An irreversible covalent JAK3-selective inhibitor (Z583) has been developed and showed efficacy in a collagen-induced arthritis mouse model, with potential for other inflammatory diseases122. Ritlecitinib is a JAK3 and TEC kinase inhibitor that has been studied for the treatment of RA and AA119,123,124. The blocking of two distinct kinase families may provide broader actions for efficacy and different, potentially less severe, side effects owing to inhibition of other JAK family members, although this remains to be determined. Other agents with broader kinase specificity have been developed including fedratinib and pacritinib, which are competitive inhibitors of JAK2 and the RTK FLT3 that are approved for the treatment of primary myelofibrosis125.

In addition to systemic use, there are multiple JAKinibs available for topical use in inflammatory skin conditions, limiting side effects associated with systemic use. Topical use of delgocitinib and ruxolitinib is approved for the treatment of AD and ruxolitinib for vitiligo69,126,127 (Table 2). Topical application of JAKinibs is also being tested in phase I–III studies for the treatment of chronic hand dermatitis (NCT05233410, 05219864 and 05293717) and GVHD (NCT03954236). Along with topical use of JAKinibs, inhaled agents are being developed. LAS194046 and AZD0449, both inhaled JAKinibs, were shown to decrease allergic lung inflammation in rats128,129. AZD0449 (a JAK1 inhibitor) has successfully completed phase I clinical trials (NCT03766399) and others are ongoing (NCT04769869). Nezulcitinib (TD-0903) successfully completed phase II clinical trials for severe COVID-19 (ref. 130). As with inhaled corticosteroids, inhaled JAKinibs could have improved safety profiles. Non-absorbable gut-selective JAKinibs have also been developed131, including OST-122, which is in phase II clinical trials for the treatment of ulcerative colitis (NCT04353791).

Another therapeutic strategy for JAKinibs involves combining them with other drugs. In patients with RA, the combination of methotrexate and tofacitinib proved beneficial to those previously refractory to methotrexate132. In severe COVID-19, baricitinib has been combined with direct-acting antivirals such as remdesivir; the combination of JAK2 inhibitors such as fedratinib with antiviral or anticytokine therapy has also been used and proposed133. Other combination therapy approaches will require further study, including potential combined use with biologics, bearing in mind that this could increase adverse events.

In summary, JAKinibs are firmly established as a therapeutic option for various conditions. The adverse events associated with JAKinibs are largely expected given the range of cytokines they block, although additional investigation into cardiovascular risk and clotting abnormalities is needed. With respect to efficacy and safety of JAKinibs, it is worth reflecting on the extent to which genetic phenotypes do or do not predict JAKinib safety. The lethal phenotypes of germline deletion of Jak2 and Jak1 were initially interpreted by some as a major limitation. Although blocking JAK2 may have downsides, first-generation JAKinibs are effective and appear relatively safe, particularly in younger populations without cardiovascular risk, contrasting the knockout phenotype.

At the same time, the degree of selectivity of agents and precisely how they act at cellular, molecular and pathological levels to mediate their therapeutic effect remain unclear. Developing a mechanistic understanding is simpler for biological agents that target single mediators than for JAKinibs, which target numerous pathways and can have different tissue-specific responses depending on the JAKinib used123. Targeting the JAK pseudokinase domain, such as is the case for deucravacitinib, may lead to improved selectivity. Advances in understanding structural details of cytokine receptors and JAKs along with improved molecular modelling may help to distinguish which inhibitor might be best for a certain inflammatory disease134. Furthermore, improved high-throughput platforms for biomarkers and improved specificity of JAKinibs should provide mechanistic insights; machine learning algorithms based on molecular fingerprints are being used to identify new targets135.

SYK family kinase inhibitors

SYK is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase essential for proximal FcR and BCR signalling that functions similar to its homologue protein tyrosine kinase ZAP70 in TCR signalling. The SYK inhibitor fostamatinib is currently approved for the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia136 (Table 1). In this autoimmune disease, autoreactive IgG antibodies target and destroy platelets through SYK-dependent FcγR-mediated phagocytosis by macrophages137. SYK family inhibitors have been proposed for the treatment of refractory chronic urticaria, an IgE-mediated allergic reaction in which cross-linking of the high-affinity FcR for IgE on mast cells leads to production of histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins and cytokines. The SYK inhibitor GSK-2646264 has completed phase I clinical trials for the treatment of refractory chronic urticaria (NCT02424799) and cutaneous lupus (NCT02927457). An SYK inhibitor has also been successfully used in a mouse model of a primary immunodeficiency with multi-organ inflammation caused by a dominant gain-of-function SYK mutation138.

Gusacitinib (ASN-002), a JAK and SYK inhibitor that inhibits FcR and BCR signalling, as well as cytokine signalling, has shown efficacy in AD139,140 (Table 3). In the glucose-6-phosphate isomerase arthritis model, the combination of tofacitinib and a SYK inhibitor was superior to either drug individually141.

TEC family kinase inhibitors

The TEC family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases includes Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK), TEC protein tyrosine kinase, bone marrow kinase on chromosome X, IL-2-inducible T cell kinase (ITK) and tyrosine protein kinase TXK (also known as RLK). BTK was the first kinase associated with a human primary immunodeficiency, X-linked agammaglobulinaemia, which is characterized by defective B cell development and impaired antibody production142 (Table 1). Indeed, BTK has an essential role in signalling from the BCR, activating phospholipase Cγ-mediated generation of the secondary messengers inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol and downstream gene transcription143 (Fig. 1). In T cells, this activity is shared between ITK, TEC and TXK, with ITK playing the main role. Besides its well-known role in BCR signalling, BTK participates in signalling downstream of chemokine receptors, Toll-like receptors, the NLRP3 inflammasome144 and multiple FcRs in innate immune cells145.

Consistent with the critical requirement for BTK in B cells, BTK inhibitors are effective in treating several mature B cell neoplastic diseases, including chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (also known as Waldenström macroglobulinaemia) and mantle-cell lymphoma146 (Table 2). However, the requirement for BTK in antibody production has also led to interest in BTK inhibitors for the treatment of antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases147. Ibrutinib, a covalent irreversible inhibitor binding residue Cys481 in the BTK kinase domain, was the first BTK inhibitor to be developed in 2007 (ref. 148). Ibrutinib inhibits other kinases that have equivalent cysteine residues in their ATP-binding cleft, including ITK, TEC, some SRC family kinases and epidermal growth factor receptor. Side effects of ibrutinib include bleeding, atrial fibrillation, rashes and hypertension, which have been attributed in part to effects on TEC, epidermal growth factor receptor and other kinases. Newer generations of BTK covalent inhibitors have been developed, including the FDA-approved drugs acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, which have greater specificity and fewer side effects. All these drugs have been used for treating malignancies, but several have potential for the treatment of autoimmune diseases including multiple sclerosis, Sjögren disease and refractory chronic urticaria (Table 3). However, resistance to ibrutinib and other covalent binders can occur, often not only owing to mutations affecting Cys481 but also owing to other mutations in BTK, as well as mutations affecting its downstream target, phospholipase Cγ. More recently, non-covalent and reversible inhibitors have been developed that interact with multiple other residues in the ATP-binding site, providing potential protection against resistance and greater selectivity for BTK148. Approximately 22 BTK inhibitors are in development, with at least 13 in clinical trials for immune-mediated diseases149,150.

BTK inhibitors have also been tested for their ability to interfere with the ‘cytokine storm’ seen in patients with severe COVID-19 (ref. 151). It has been proposed that BTK inhibition may suppress the excessive inflammation and pro-inflammatory cytokine production caused by innate immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 and provide protection against severe lung injury152. Patients with X-linked agammaglobulinaemia who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 were originally reported to manifest relatively mild disease courses possibly owing to decreased innate immune cell activation in the context of relatively intact T cell-mediated immunity153. However, more recent data indicate that some patients with X-linked agammaglobulinaemia fail to clear SARS-CoV-2, requiring rehospitalization154. These observations highlight both the importance of humoral immunity for protection against SARS-CoV-2 and the potential pitfalls of using immunosuppression during viral illness.

ITK is the TEC family kinase that is most highly expressed in T cells, where it functions to regulate the magnitude of TCR signalling and T cell differentiation143. The BTK inhibitor ibrutinib is also a potent inhibitor of ITK and has subsequently been investigated for the treatment of several inflammatory conditions involving T cells; it was the first drug to be licensed for the treatment of GVHD155. Indeed, ITK-deficient mice are resistant to GVHD156, suggesting that ITK is a critical target in this treatment. ITK-deficient mice are also resistant to airway inflammation, and multiple ITK inhibitors have been developed with the goal of treating asthma. However, although administration of a selective ITK inhibitor or ITK deficiency prevents development of allergic asthma in murine models, administration of an ITK inhibitor after induction of asthma worsened outcomes157. That observation was attributed to effects on T cell reactivation-induced cell death, although other mechanisms may contribute, including increased responsiveness to IL-2 (ref. 158). ITK deficiency in mice or treatment with ITK inhibitors also prevents development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a mouse model for multiple sclerosis159, although it has not yet been evaluated in humans for this purpose. JTE051 is an oral ITK inhibitor that completed a phase II clinical trial for RA, but showed no significant improvement in the ACR20 response rate at week 12 (ref. 90). However, ritlecitinib, a JAK3 and TEC inhibitor, as noted earlier, has shown efficacy in treating RA, AA and vitiligo in clinical trials119,123,124,160.

Conclusions and future predictions

Over the past 20 years, great progress has been made in advancing protein kinase inhibitors in the clinic, starting with cancer but now substantially impacting autoimmune, allergic and even infectious diseases including COVID-19. The success of imatinib highlights the strategy of purposefully targeting kinases, both as anticancer drugs and inhibitors of the immune system. Yet, this dual utility is not universally applicable; mTOR inhibitors have had modest success as anticancer drugs compared with their efficacy in allogeneic transplantation and immune modulation (Box 1). By contrast, inhibitors of components of mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling cascades including BRAF have had success as chemotherapies but generated little interest as inhibitors of immune function, although efforts in this area and others are ongoing (Box 2).

Beyond therapeutic efficacy, targeted therapies, as well as biologics, can elucidate immunopathogenic mechanisms and disease endotypes; indeed, truly selective agents can give clues to underlying pathogenesis. Unlike the specificity of biologics, small molecule kinase inhibitors, especially competitive ATP antagonists, have relative degrees of selectivity. In addition, many kinases mediate signalling by diverse ligands and even different families of ligands. This is true of first-generation JAKinibs — even when efficacious, it can be difficult to assign this to specific cytokines. Nevertheless, detailed assessment of biomarkers and gene expression may reveal clues to disease pathogenesis and mechanism of action.

Many kinase inhibitors have demonstrated efficacy in immune-mediated disease, but equally, if not more, important is safety. Delivering the drug directly to the target organ or cell is a longstanding solution for limiting systemic adverse events. For example, several JAKinibs are available topically to treat inflammatory skin conditions or as inhaled agents to treat asthma. This is analogous to the success of topical and inhaled steroids that are now mainstays of therapy in both conditions. Similarly, parenteral injection of steroids is widely used, but many approved kinase inhibitors have not been generated as parenteral formulations.

In principle, the ideal protein kinase inhibitor is selective, with minimal off-target side effects. However, it has become clear that some kinase inhibitors interact not only with other kinases but also with G-protein-coupled receptors and bromodomain-containing proteins. For instance, the JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib also targets bromodomain-containing protein 4, which could add to its efficacy but also lead to adverse events. Alternative strategies for designing kinase inhibitors have potential to maximize selectivity beyond competitive ATP agonists. Strategies that are already being used are generation of irreversible kinase inhibitors and allosteric inhibitors. Many human protein kinases have cysteine residues in, or proximal to, the ATP-binding site; examples of inhibitors that target these residues include covalent BTK inhibitors and the JAK3 and TEC inhibitor ritlecitinib. In addition, as the catalytic domain of protein kinases is highly conserved, cysteine residues distal from the ATP-binding site may also be targeted. Only a small proportion of protein kinases have a catalytically inactive kinase domain; targeting the JAK pseudokinase domain was the strategy used to develop deucravacitinib. More recently, a covalent, allosteric JAK1 inhibitor, VVD-118313, that targets the pseudokinase domain has also been reported161. Interestingly, endogenous compounds including metabolites can bind outside catalytic domains. For instance, the Krebs cycle-derived metabolite itaconate inhibits IL-4 signalling and binds to multiple JAK1 cysteines162. Furthermore, residues other than cysteines such as lysine, tyrosine, histidine and methionine can be used to generate irreversible inhibitors.

Deucravacitinib is also notable in that it is deuterated. Because deuterium–carbon bonds are stronger than hydrogen–carbon bonds, this modification can improve pharmacodynamics, with the potential for increasing potency and selectivity. Ideally, these options for rational design improve efficacy and safety. The macrolide antibiotics sirolimus and tacrolimus inhibit discrete signalling pathways by indirect mechanisms with a high degree of specificity even when they bind to the same protein (Box 1). This suggests that there are other novel ways of devising specific signalling inhibitors yet to be discovered. Ideally, agents with improved selectivity will offer even greater opportunities to elucidate immunopathological mechanisms.