Abstract

Entosis is a non‐apoptotic cell death process that forms characteristic cell‐in‐cell structures in cancers, killing invading cells. Intracellular Ca2+ dynamics are essential for cellular processes, including actomyosin contractility, migration, and autophagy. However, the significance of Ca2+ and Ca2+ channels participating in entosis is unclear. Here, it is shown that intracellular Ca2+ signaling regulates entosis via SEPTIN‐Orai1‐Ca2+/CaM‐MLCK‐actomyosin axis. Intracellular Ca2+ oscillations in entotic cells show spatiotemporal variations during engulfment, mediated by Orai1 Ca2+ channels in plasma membranes. SEPTIN controlled polarized distribution of Orai1 for local MLCK activation, resulting in MLC phosphorylation and actomyosin contraction, leads to internalization of invasive cells. Ca2+ chelators and SEPTIN, Orai1, and MLCK inhibitors suppress entosis. This study identifies potential targets for treating entosis‐associated tumors, showing that Orai1 is an entotic Ca2+ channel that provides essential Ca2+ signaling and sheds light on the molecular mechanism underlying entosis that involves SEPTIN filaments, Orai1, and MLCK.

Keywords: calcium signaling, cell‐in‐cell, entosis, Orai1, SEPTIN

Entosis is a non‐apoptotic cell death process that forms characteristic cell‐in‐cell structures in cancers, killing invading cells. Intracellular Ca2+ signaling by IP3R coupled Orai1 Ca2+ channels regulates entosis via SEPTIN‐Orai1‐Ca2+/CaM‐MLCK‐actomyosin axis. This provides insights into a therapeutic target for entotic regulators promoting entosis‐mediated tumor development.

1. Introduction

Entosis, a non‐apoptotic cell death process, engulfs homotypic living cells.[ 1 ] Although it was first observed over 100 years ago, the underlying mechanisms and functional consequences have been studied in recent years. Entosis is triggered by several physiological conditions such as matrix detachment, aberrant mitosis,[ 2 ] and glucose deprivation.[ 3 ] These various pathways for entosis reflect the characteristics of cancer cells, such as abnormal proliferation, anchorage‐independence, and metabolic stress, suggesting that intrinsic properties of cancer cells or their microenvironments can cause entosis. It is associated with a wide range of human diseases, such as genome instability,[ 4 , 5 ] developmental disorders,[ 6 , 7 ] and cancer.[ 8 ]

Regardless of the mechanism by which entotic cells initiate, they form adherens junctions (AJs) via Ca2+/E‐cadherins.[ 9 ] Following the formation of AJs, they are engulfed through actin polymerization following AJ,[ 10 ] mechanical ring,[ 11 ] and actomyosin contraction.[ 1 , 9 ] Lastly, they appear in cell‐in‐cell (CIC) structures, resulting in inside cells escaping and dividing; although, they typically die via lysosomal degradation.[ 12 ]

Engulfing (outer, host, winner) and invading (inner, internalizing, engulfed, loser) entotic cells form CIC structures through actin polymerization and myosin contraction. Invading cells have higher stiffness with accumulated actomyosin in the cell cortex, opposite to AJ, and the resulting mechanical tension drives CIC invasion. It is regulated by RhoA, Rho‐associated protein kinase (ROCK), and diaphanous‐related formin 1 (Dia1).[ 13 , 14 ] Engulfing cells have lower tension than invading cells and swallow neighboring cells with actin‐dependent engulfment activity. Rac1, a key mediator of the actin cytoskeleton, and KRas, the oncogene regulating Rac1 activity, enhance engulfing by regulating actomyosin contractility.[ 13 ]

Cytosolic Ca2+ function as intracellular signaling messengers and are involved in cytoskeleton rearrangement, metastasis, metabolism, cell death, and cancer development.[ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ] An important mechanism for maintaining intracellular Ca2+ levels is store‐operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), which is mediated by Orai1 Ca2+ channels in plasma membrane (PM)[ 19 , 20 ] and stromal interaction molecule (STIM) proteins[ 21 ] in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). STIM senses ER Ca2+ concentrations and accumulates at ER‐PM junctions following ER Ca2+ depletion, activating Orai1 channels in adjacent PM. Ca2+ entry through Orai1 channels is associated with several cell signaling processes in most cells.[ 22 , 23 ]

Orai1‐STIM1 assembly and stability, and architecture of ER‐PM junctions, are determined by specific protein and lipid components including SEPTINs, phosphatidyl 4,5‐bisphosphate(PIP2), and proteins scaffolding ER to PM.[ 24 , 25 ] SEPTINs, filament forming GTPases, bind to inner PM through specific interactions with PIP2 and assemble on membrane domains.[ 26 , 27 , 28 ] They promote stable recruitment of Orai1 by maintaining PIP2 organization in PM.[ 29 ] Their loss results in abnormal Orai1 clustering and reduced SOCE.

Myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation is essential for entosis providing contractile force. It is determined by myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), ROCK, and MLC phosphatase (MLCP). MLCK, the best‐studied factor regulating MLC phosphorylation, is Ca2+/Calmodulin‐dependent serine/threonine kinase (CaMK) and is activated by CaM in response to an increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels. Activated MLCK phosphorylates the regulatory myosin light chains of myosin II (MLC2), specifically at serine‐19, facilitating actin‐activated myosin and promoting myosin‐driven contraction.

Extracellular Ca2+ is required for E‐cadherin‐mediated cell junction formation during entosis. However, the role of intracellular Ca2+ signaling in entosis, and the mechanism through which it is modulated, remain poorly understood. Entosis‐associated molecular pathways are Ca2+‐dependent. Orai1, a major Ca2+ route, regulates diverse processes related to entosis. For example, Ca2+ influx through Orai1 controls actin organization and dynamics at the immune synapse in T lymphocytes,[ 30 ] membrane blebs in amoeboid cells,[ 31 ] and leading‐edge in migrating cells.[ 32 , 33 ] Orai1‐dependent signaling enhances contractile force by regulating actomyosin reorganization.[ 22 , 34 ] Furthermore, entosis‐associated proteins, including actin, MLC, Ezrin,[ 31 ] Rac1,[ 33 ] AMP‐activated protein kinase (AMPK), and vinculin[ 22 ] are regulated by Orai1 or Orai1 mediating Ca2+ signals. We hypothesized that Orai1 is a major route for Ca2+ influx during entosis.

Here, we provide evidence that Orai1 is an entotic Ca2+ channel, whose membrane localization is tightly controlled by SEPTINs, resulting in temporal entotic Ca2+ oscillations that affect MLCK‐actomyosin rearrangement during entosis. We identify the mechanism through Orai1‐mediated Ca2+ signaling regulating Ca2+‐dependent engulfment during entosis and provide insights into a therapeutic target for entotic regulators promoting entosis‐mediated tumor development.

2. Results

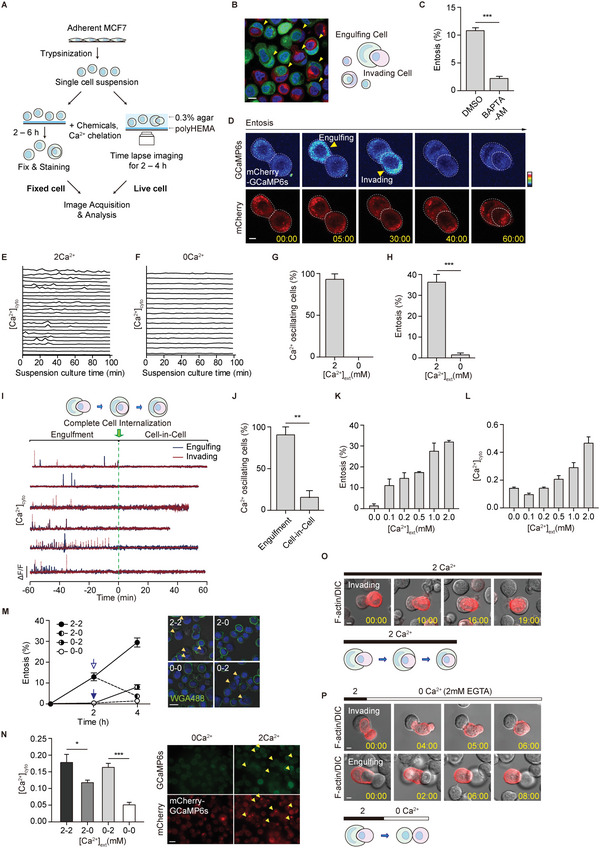

2.1. Spontaneous Ca2+ Oscillations Occur During Entosis

Ca2+ signaling drives intracellular processes and communicates between cells. Intracellular Ca2+ concentration exhibits diverse spatiotemporal dynamics, influencing the versatility of Ca2+‐dependent signaling.[ 18 ] Hence, we investigated whether and how Ca2+ signaling, particularly Ca2+ channel‐mediated Ca2+ dynamics, is required for entosis. To determine whether intracellular Ca2+ is necessary for entosis, we first measured the entosis efficiency in MCF7 cells treated with BAPTA‐AM, a cell‐permeable Ca2+ chelator. For entosis quantification, adherent MCF7 cells were trypsinized into single cells and cultured in suspension for 2–6 h under the indicated conditions (Ca2+ chelation or chemical treatment) (Figure 1A). Cells were fixed and stained for PM and nucleus. Analysis using confocal microscopy demonstrated the complete CIC structures (entotic cells). The percentage of entotic cells was determined through quantifying the number of single cells and CIC structures (Figure 1B). When we treated BAPTA‐AM, the cells showed reduced entosis efficiency compared with cells in the Ca2+ medium, confirming that intracellular Ca2+ is required for entosis. The cells showed reduced entosis efficiency compared with cells in the Ca2+ medium (Figure 1C), confirming that intracellular Ca2+ is required for entosis.

Figure 1.

Entotic Ca2+ oscillations occur during the engulfment. A) Schematic representation of the method for quantifying and imaging entotic cells. B) Representative images of entotic cells and a diagram of an entotic cell pair: engulfing and invading cells. Yellow arrowheads indicate entotic cells. Scale bar = 10 µm. C) Quantification of internalizing cells in BAPTA‐AM (10 µm, with 100 µm of EGTA) after 6 h of suspension. Data represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (n > 200 cells). D) Spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in MCF7 cells during entosis. Yellow arrowheads indicate Ca2+ signals. Time is presented in min: s. Scale bar = 5 µm. E,F) Graph of normalized GCaMP6s ratio (GCaMP6s/mCherry) in entotic cell pairs exposed to 2 mm extracellular Ca2+ (E, from Figure S1A,B, Supporting Information, n = 24) and non‐entotic cells exposed to 0 mm extracellular Ca2+ (2 mm EGTA) (F, n = 17). G) Quantification of Ca2+ oscillating cells from (E,F). H) Quantification of internalizing cells cultured in suspension for 4 h in the presence of 2 and 0 mm Ca2+. Data represent mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments (n > 300 for each cell line). I) Spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in MCF7 cells during entosis. Y axis: 4 (A.U.) J) Quantification of Ca2+ oscillating cells during engulfment and CIC stages. The timepoint at which a complete CIC structure was made was aligned to 0. (Engulfment: −60 to 0 min, cell‐in‐cell:0–60 min). Data represent mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments (n = 7, 6, and 5). K,L) Quantification of internalizing cells depending on extracellular Ca2+ concentration (K) and intracellular Ca2+ level (GCaMP6s/mCherry) (L). Data represent mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments (n = 52 for each condition). M) Quantification of internalizing cells depending on extracellular Ca2+ concentration. Ca2+ add‐back (0–2) and Ca2+ withdrawal (2–0). Data represent mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments (n > 200 for each cell line). Scale bar = 20 µm. N) Graph of normalized GCaMP6s ratio (GCaMP6s/mCherry). Data represent mean ± SEM. n = 74, 42, 38, and 33 for each group. Scale bar = 20 µm. O,P) Time‐lapse images of entotic cells in the presence of Ca2+ (O) and under Ca2+ withdrawal (2 → 0 mm and addition of 2 mm EGTA) (P). Cherry‐Lifeact labeled cell morphology. Scale bar = 5 µm. Significance was determined using unpaired two‐tailed t‐test. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

To assess the effect of Ca2+ signaling on entosis progression, we measured intracellular Ca2+ concentrations in “engulfing” and “invading” entotic MCF7 cells expressing mCherry‐GCaMP6s, a genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator.[ 35 ] Time‐lapse microscopy imaging was performed for 100 min at 3–5 min intervals in 0.3% low melting agarose as described[ 1 ] (Figure 1A,D; Movie S1, Supporting Information). A Ca2+‐insensitive fluorophore, mCherry, ensured proper GCaMP6s expression and normalized GCaMP6s intensity. Ca2+ oscillations 1.5× above the standard deviation of the threshold of the GCaMP6s/mCherry fluorescence ratio were counted as Ca2+ signals. Interestingly, we observed spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in most (90%) entosis proceeding cells in Ca2+ dependent manner (Figure 1D–G) as no oscillation occurred when extracellular Ca2+ was depleted with 2 mm EGTA (Figure 1F,G) and the efficiency of entosis was reduced in the absence of Ca2+ (35% to 1%, Figure 1H). In addition, there were no differences in Ca2+ oscillation between “Engulfing” and “Invading” cell pairs (Figure S1, Supporting Information), implying that both cells require intracellular Ca2+ signals to undergo entosis. These results suggest that extracellular Ca2+ is necessary for initiating entosis and for intracellular Ca2+ oscillations during entosis.

2.2. Spontaneous Ca2+ Oscillations Occur Mainly in the Early to Mid‐Engulfment Stage

We explored entotic Ca2+ oscillation by analyzing the efficiency and time kinetics of the initiation of internalization and engulfment. Internalization occurred ≈2 h after matrix detachment (Figure S2A,B, Supporting Information) and was followed by engulfment for 30 to 60 min (Figure S2B,C, Supporting Information). To elucidate temporal Ca2+ oscillation patterns during entosis, time points at which entotic cells formed complete CIC structures were set to 0. We monitored changes in Ca2+ concentrations in MCF7 cells expressing mCherry‐GCaMP6s 1 h before and after complete cell internalization at 3 s intervals (Figure 1I). Approximately 90% of entotic cells showed spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations, with non‐synchronized patterns between engulfing and invading cells, before forming complete CIC structures (Figure 1I,J). Interestingly, we noticed that Ca2+ oscillations dramatically disappeared in entotic cells with complete CIC structure. These results indicated that Ca2+ oscillations might be temporally controlled during entosis, specifically during engulfment, rather than during most completed CIC structure stages.

2.3. Extracellular Ca2+ Regulates Intracellular Ca2+ Level for Entosis

To determine whether intracellular Ca2+ oscillations depend on extracellular Ca2+, we measured entosis efficiency and intracellular Ca2+ concentrations under various extracellular Ca2+ conditions. Both entosis efficiency (Figure 1K) and intracellular Ca2+ concentrations (Figure 1L) increased as extracellular Ca2+ concentrations increased from 0 to 2 mm, demonstrating that intracellular entotic Ca2+ oscillations are linked to extracellular Ca2+.

To further confirm the effect of extracellular Ca2+ on entosis efficiency and intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, we performed “Ca2+ add‐back” and “Ca2+ withdrawal” in entotic MCF7 cells. We induced entosis in 0 mm extracellular Ca2+ with Ca2+ chelator EGTA for 2 h of suspension culture and followed by 2 mm Ca2+ medium for another 2 h. Entosis efficiency increased from 1% at 2 h to 9% at 4 h (Figure 1M). Intracellular Ca2+ concentrations increased approximately threefold after adding Ca2+ (Figure 1N). Replacing Ca2+ with EGTA (“Ca2+ withdrawal”) decreased entosis efficiency from 15% at 2 h to 4% at 4 h (Figure 1M), while efficiency increased from 15% to 30% in Ca2+ medium (Figure 1M). We observed similar changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations with Ca2+ withdrawal resulting in an approximately twofold reduction in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations (Figure 1N). These results confirmed that extracellular Ca2+ influences entosis efficiency by regulating intracellular Ca2+ concentrations.

We then visualized how Ca2+ regulates the movement of entotic cells using mCherry‐tagged LifeAct. Time‐lapse imaging showed changes in movement and morphology of entotic cells. Half invading entotic cells continued to invade engulfed entotic cells, in the presence of 2 mm extracellular Ca2+, resulting in CIC structures (Figure 1O). However, the cells began to emerge soon after inhibiting Ca2+ with EGTA (Figure 1P). Interestingly, we found that a pair of almost engulfed entotic cells (completed more than 90%) were not separated into individual cells even in 0 mm extracellular Ca2+ with 2 mm EGTA condition (Figure S3, Supporting Information) as proposed.[ 11 ] It indicated that Ca2+ may be necessary for CIC attachment at the initial stage and Ca2+ oscillation in the middle stage, but less in the final stage.

Taken together, these results suggested that extracellular Ca2+ affects entosis efficiency by regulating oscillating intracellular Ca2+ signaling for regulating particular entosis stages.

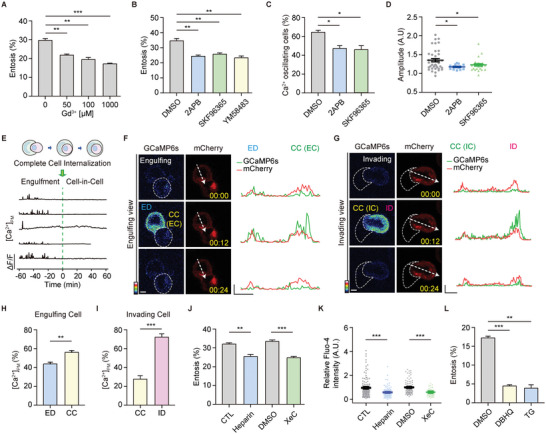

2.4. SOC Channel Blockers Prevent Entosis

It was surprising to find that no reports have been found regarding Ca2+ channels that are associated with entosis. Thus, we explored which Ca2+ channels regulate entotic Ca2+ signaling for entosis. To find out potential Ca2+ channels, suspended MCF7 were treated with gadolinium (Gd3+), an inorganic Ca2+ channel blocker for 3 h and showed a decreased entosis efficiency (Figure 2A), indicating the involvement of Ca2+ channels in entosis. In cancer cells, SOC (Orai) channels are best known for major Ca2+ channels. Therefore, MCF7 cells were treated with SOC channel blockers, 2‐APB, SKF96365, and YM58483 for 4 h and showed reduced entosis efficiency from 35% to 20% (Figure 2B), indicating that SOC Ca2+ channels might be an unrevealed Ca2+ channel of entosis. We further analyzed the change in Ca2+ oscillations in MCF7 cells with the blockers. The number of Ca2+ oscillating cells decreased by 45% in the presence of SOC channel blockers compared with DMSO (≈65%, Figure 2C; Figure S4, Supporting Information). The amplitude of intracellular Ca2+ transients also decreased (Figure 2D). These results provide the first evidence that SOC channels are entotic Ca2+ channels that can induce Ca2+ oscillations.

Figure 2.

Entotic cells show polarized Ca2+ signals during entosis. A) Bar graph showing entosis efficiency after 3 h. Entotic cells were quantified with Gd3+ in the dose‐dependent manner. Data represent mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments (n > 200 for each). B) Quantification of entotic cells in SOC channel blockers; 2‐APB (50 µm), SKF96365 (10 µm), and YM58483 (10 µm) compared with the control (DMSO). Cell suspensions were cultured with each inhibitor for 4 h. Data represent mean ± SEM of the triplicate experiments (n > 300 in each experimental group). C) Quantification of Ca2+ oscillating cells in DMSO, 2‐APB, and SKF96365 from (Figure S4, Supporting Information). Higher Ca2+ levels, defined by setting the threshold to 1.5× above the standard deviation, were counted as Ca2+ signals (n = 28, 19, and 24). D) Quantitative comparisons of spontaneous Ca2+ signals measured using GCaMP6s (GCaMP6s/mCherry). The compared quantities were peak amplitudes ∆F/F ratios. Data represent mean ± SEM. E) Graph of normalized GCaMP6s‐CAAX ratio in entotic cells. F,G) Local Ca2+ influx was reported using GCaMP6s‐CAAX, the PM Ca2+ indicator, in engulfing (F) and invading (G) cells. Line scan profile analysis of mCherry‐GcaMP6s‐CAAX signal. Scale bar = 5 µm. X axis: 5 µm, Y axis: 500. H,I) Bar graphs of the Ca2+ peak amplitudes in cell contact site and distal region of engulfing (n = 5) (H) and invading (n = 4) cells (I). Data represent mean ± SEM. J) Quantification of entotic cells cultured for 4 h with IP3R inhibitor, heparin (400 µg mL−1), and Xestospongin C (4 µm). Data represent mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments (n > 300 in each experimental group). K) Intracellular Ca2+ levels of MCF7 cells in suspension with control (n = 124) and heparin (400 µg mL−1, n = 102), and DMSO (n = 93) and Xestospongin C (4 µm, n = 59). Fluo‐4 intensity quantification data represent mean ± SEM. L) Quantification of entotic cells cultured for 2.5 h in SERCA inhibitors, DBHQ (25 µm), and TG (1 µm). Data represent mean ± SEM of duplicate experiments (n > 200 in each experimental group). Significance was determined using unpaired two‐tailed t‐test. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; and *p < 0.05. ED: engulfing cell distal region; CC: cell‐cell contact site; ID: invading cell distal region.

2.5. Entotic Cells Show Polarized Membrane Ca2+ Signals

Ca2+ concentrations of entotic Ca2+ oscillating cells were enriched in the PM of both invading as well as engulfing cells (Figure 1D); thus, we analyzed spatially localized Ca2+ signaling during entosis using mCherry‐GCaMP6s‐CAAX, a PM‐localized Ca2+ indicator. Examining the localization and Ca2+ responsiveness of mCherry‐GCaMP6s‐CAAX in MCF7 cells showed restricted local Ca2+ influx without Ca2+ release from depleted stores (Figure S5, Supporting Information), indicating that GCaMP6s‐CAAX can measure Ca2+ changes near PM. To investigate entotic membrane Ca2 signaling in detail, we performed time‐lapse imaging. In MCF7 cells expressing mCherry‐GCaMP6s‐CAAX, the spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations were PM‐enriched and spatially localized in both engulfing and invading entotic cells (Figure 2E–G), which is similar to the results of GCaMP6s, a cytosolic Ca2+ indicator, during engulfment (Figure 1I).

We further analyzed the concentration of membrane Ca2+ of engulfing and invading cells. Interestingly, not only a change in the local Ca2+ distribution but also a differential local distribution was observed between invading and engulfing cells during engulfment. In engulfing cells, local Ca2+ concentrations were higher at CC (cell–cell contact site) than at the distal membranes (engulfing cell distal region, ED) (Figure 2F,H; Movie S2, Supporting Information). However, invading cells had a higher level of Ca2+ at the cell cortex of the distal membrane (invading cell distal region, ID) and lower local Ca2+ concentrations at the CC (Figure 2G,I; Movie S3, Supporting Information). These results provide the first evidence that differential Ca2+ signaling in entotic cell pairs is required for proper cellular signaling and organization during entosis.

2.6. IP3 Related Store Depletion Could Induce Entotic Ca2+ Signaling

To check how Ca2+ oscillations are induced and dependent on store depletion during entosis, we investigated whether intra‐ER Ca2+ signaling through the inositol 1,4,5‐trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) or sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+‐ATPase (SERCA) may affect the Ca2+ influx and entosis efficiency. First, we treated MCF7 cells with the IP3R inhibitor, heparin (400 µg mL−1), and Xestospongin C (4 µm), and measured intracellular Ca2+ concentration and entosis efficiency. The cells with the IP3R inhibitor showed a reduced entosis efficiency (Figure 2J), as well as a decrease in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (Figure 2K), indicating that IP3R coupled store depletion followed by SOCE activation could play a role in entosis. In addition, we depleted ER Ca2+ by treating the cells with DBHQ (Di‐tert‐butylhydroquinone) or TG (Thapsigargin), two SERCA inhibitors. Our results showed that DBHQ (25 µm) or TG (1 µm) significantly reduce the efficiency of entosis (Figure 2L), indicating that SERCA‐mediated ER Ca2+ maintenance is crucial for entosis.

Therefore, these results suggest that intra‐ER Ca2+ signaling through the IP3R is critical for SOCE activation which leads to generating Ca2+ oscillations in entosis.

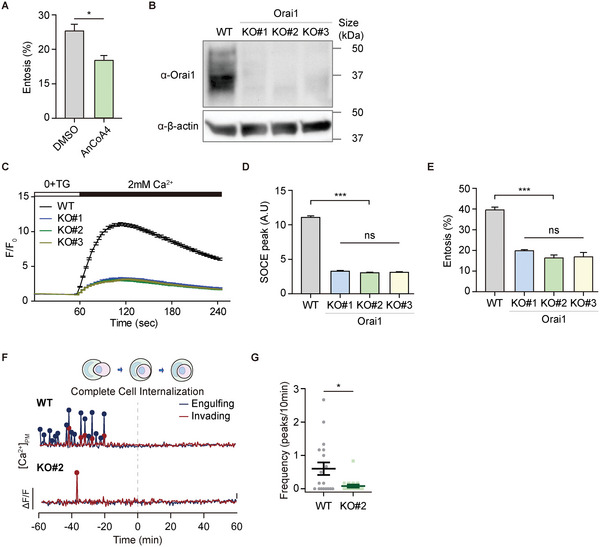

2.7. Orai1 is the Entotic Ca2+ Channel

We hypothesized that this polarized membrane Ca2+ might be induced by Orai1 Ca2+ channels, the best‐known SOC channel because it regulates lots of common signaling pathways in cancer cells that are also essential for entosis, including actin polymerization, myosin contraction, and membrane blebbing. To test this, we treated MCF7 cells with 10 µM AnCoA4 (Figure 3A), an Orai1‐specific inhibitor that binds directly to the C‐terminus region of Orai1 and blocks Ca2+ influx.[ 36 ] It is not surprising that we observed a decrease in entosis efficiency, indicating that the Orai1 channel may be an entotic Ca2+ channel.

Figure 3.

Orai1 is an unrecognized entotic Ca2+ channel. A) The effect of AnCoA4 on entosis. The cells were pretreated with AnCoA4 (10 µm) and DMSO for 24 h and quantified entotic cells after 3 h suspension. Data represent mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments (n > 200 for each). Significance was determined using unpaired two‐tailed t‐test. *p < 0.05. B) Western blot analysis of Orai1 WT and KO MCF7 cells. β‐actin was included as endogenous control. C) TG‐induced Ca2+ influx in Orai1 KO cell lines monitored by Fluo‐4 (F/F 0). D) Comparison between the SOCE peaks from (C). Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 165, 67, 136, and 148 cells from each cell line). Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. ***p < 0.001. ns: not significant. E) Quantification of entotic cells in Orai1 WT and KO MCF7 cells. Data represent mean ± SEM of the triplicate experiments (n > 300 in each experimental group). Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. ***p < 0.001. ns: not significant. F) Local Ca2+ influx reported using mCherry‐GCaMP6s‐CAAX in Orai1 WT and KO MCF7 cells. G) Quantification of Ca2+ signals in Orai1 WT and KO entotic cells (n = 18 for each). Three independent experiments were quantified. Significance was determined using unpaired two‐tailed t‐test. *p < 0.05.

We used CRISPR‐Cas9‐generated Orai1 knockout (KO) MCF7 cells to explore the function of Orai1 Ca2+ channels during entosis (Figure S6A,B, Supporting Information). We confirmed the ablation of Orai1 protein expression in three representative Orai1 KO cell lines with different indel (deletion/insertion) mutations using immunoblotting (Figure 3B) and immunocytochemistry (Figure S6C, Supporting Information). We confirmed that the loss of Orai1 resulted in significantly reduced SOCE when ER Ca2+ stores were depleted (Figure 3C,D). There were no significant differences in other SOCE components (STIM1, STIM2, Orai2, Orai3) between wildtype (WT) and KO cells (Figure S6D–G, Supporting Information).

We next found that Orai1 deletion decreased entosis efficiency from 40% to 15% (Figure 3E), indicating that Orai1 Ca2+ channels positively regulate entosis. To investigate whether Orai1 Ca2+ channels induce local Ca2+ influx in entotic cells during the engulfment stages of entosis, we expressed mCherry‐GCaMP6s‐CAAX in Orai1 WT and KO cells, acquired time‐lapse images at 30 s intervals over 4 h, and aligned the end of engulfment to time 0. WT cells showed PM‐localized Ca2+ oscillations before entotic cells formed CIC structures (engulfment stage: ≈ −60 to 0 min) (Figure 3F; Movie S4, Supporting Information). Surprisingly, few oscillating cells were detected and the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations was significantly lower in Orai1 KO cells (Figure 3F,G; Movie S5, Supporting Information), suggesting that Orai1 is a bona fide entotic Ca2+ channel that provides local Ca2+ oscillations in entotic cells for the engulfment.

2.8. Orai1 Shows the Polarized Distribution in Invading Cells

To determine whether Orai1 Ca2+ channels affect Ca2+ concentrations in entotic cells, we analyzed the localization of endogenous Orai1 at early, middle, and late engulfment stages, based on the proportion of engulfment membrane (Figure 4A). Similar to the observation that entotic cells have differential Ca2+ concentrations with mCherry‐GCaMP6s‐CAAX (Figure 2F–I), we observed preferential localization of Orai1 during engulfment. Approximately 60% of Orai1 accumulated at CC in the early and middle engulfment stages and moved to the ID in the late stage (Figure 4B). We tracked the localization of Orai1 in cells expressing GFP‐Orai1 using time‐lapse imaging (Figure 4C; Movie S6, Supporting Information). Although distinct differential localization of endogenous Orai1 or GFP‐Orai1 was not observed in engulfing cells, GFP‐Orai1 was enriched in CC during the early engulfment stage and translocated predominantly to the ID following engulfment. Moreover, the polarized localization of Orai1 was confirmed using cells labeled with cytoplasmic membrane dyes (CellBrite Red, Figure S7A, Supporting Information) and cytosol dyes (CellTracker Red, Figure S7B, Supporting Information).

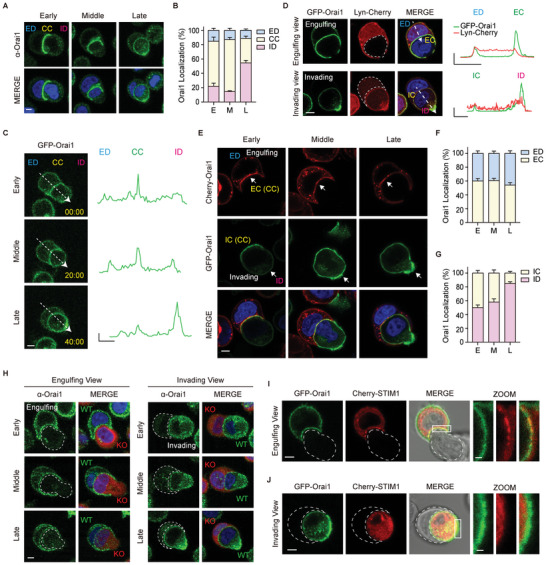

Figure 4.

Orai1 shows the polarized distribution during entosis. A) Immuno‐fluorescent images of suspended cells taken after 2.5 h of culturing show endogenous Orai1 (green). B) Bar graphs showing the distribution of Orai1 at different engulfment stages. Early‐stage (E, <1/3 internalization, n = 10); middle‐stage (M, 1/3–2/3 internalization, n = 24); late‐stage (L, >2/3 internalization, n = 35). C) Time‐lapse fluorescence images of GFP‐Orai1 stably expressed MCF7 cells during entosis. Times are indicated as h: min: s. Line graphs show GFP pixel intensities for the indicated line scans. X axis: 5 µm, Y axis: 5000 (A.U.). D) Fluorescence images of GFP‐Orai1 and Lyn‐Cherry (PM marker) expressing MCF7 cells. Line scan analysis of relative GFP‐Orai1 (green) and Lyn‐Cherry (red) signals along the white arrow in the merge image. X axis: 5 µm, Y axis: 1 (A.U.). E) Fluorescence images of Cherry‐Orai1 (engulfing cell)‐ and GFP‐Orai1 (invading cell)‐expressing MCF7 cells cultured for 2.5 h in suspension. F,G) Bar graphs showing Orai1 distribution in engulfing cells (F) and invading cells (G). H) Immunofluorescence images of endogenous Orai1 (green) in WT and Orai1 KO (red) cells show Orai1 distribution in engulfing and invading cells. I,J) Fluorescence images of GFP‐Orai1‐ and Cherry‐STIM1‐ expressing MCF7 cells cultured for 2.5 h in suspension. Engulfing (I) and Invading (J) cells. Cropped image scale bar = 1 µm. Scale bar = 5 µm. ED: engulfing cell distal region; CC: cell–cell contact site; ID: invading cell distal region. EC: engulfing cell contact site. IC: invading cell contact region.

With single fluorescence imaging, it is difficult to determine the differential localization of Orai1 in entotic cell pairs; although, we observed the preferential localization of Orai1 in ID. Therefore, we expressed GFP‐Orai1, respectively in engulfing cell or invading cell and additionally co‐expressed Lyn‐Cherry, PM marker protein, demonstrating the preferential localization of Orai1 during entosis (Figure 4D). Furthermore, we mixed cells expressing mCherry‐Orai1 or GFP‐Orai1 and visualized the localization of Orai1 in entotic cells, having different pairs of fluorescent‐tagged‐Orai1s during engulfment (Figure 4E). Two‐color label assay confirmed that Orai1 was translocated from CC (IC) to ID in invading cells (Figure 4E,G), but engulfing cells appeared preferentially at the CC during entire engulfment stage (Figure 4E,F). The polarized patterns were further confirmed using endogenous Orai1 immunofluorescence imaging (Figure 4H).

Orai1 channels are activated through direct interaction with the ER Ca2+ sensor, STIM. Co‐expressing GFP‐Orai1 and Cherry‐STIM1 in MCF7 cells showed that Orai1 and STIM1 are co‐localized during entosis (Figure 4I,J), suggesting that STIM1 activates Orai1, resulting in entotic Ca2+ oscillation and cellular responses during engulfment.

Taken together, Orai1 translocation and the spatial entotic Ca2+ oscillation are well correlated, suggesting that Orai1, as an entotic Ca2+ channel, may regulate spatiotemporal Ca2+ signaling in entotic cell pairs during entosis.

2.9. SEPT2 Organizes the Distribution of Orai1 in Invading Cells

SEPTINs have been known to modulate local STIM‐ORAI Ca2+ signaling by modulating Orai1 concentrations at the ER‐PM junction,[ 29 , 37 , 38 ] which led us to investigate whether SEPTINs regulate Orai1 distribution in entotic cells during entosis.

First, we explored the role of SEPTINs during entosis using the SEPTIN inhibitor, forchlorfenuron (FCF; 50 µm), which alters the assembly and disassembly of SEPTIN networks.[ 39 ] Surprisingly, we found that entosis efficiency in MCF7 cells treated with FCF for 4 h reduced from approximately 35% to 15% (Figure 5A). In addition, we confirmed the unrecognized function of SEPTINs by adding the inhibitor in the middle of entosis. Efficiency decreased to 25% compared with the control (40%) 2 h after FCF was added (Figure S8A, Supporting Information). We also found that FCF also delayed the early‐stage onset of entosis (Figure S8B, Supporting Information). Hence, these results suggest that SEPTINs may play a role in entosis by modulating the preferential localization of Orai1 and local Ca2+ oscillations.

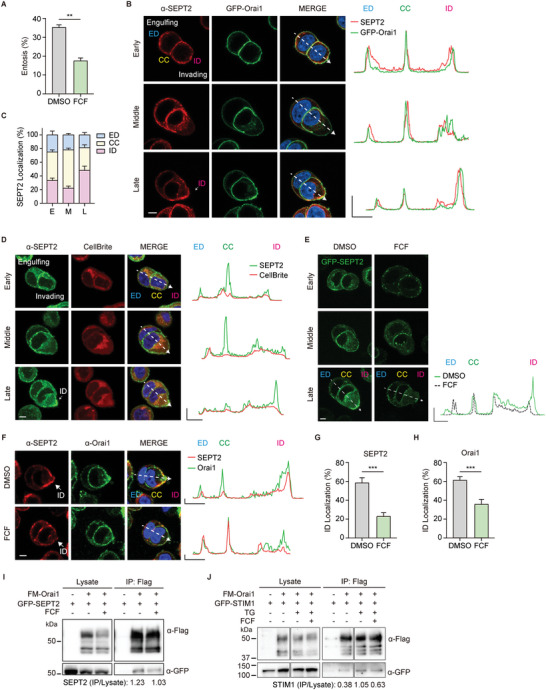

Figure 5.

SEPT2 organizes the polarized distribution of Orai1 in invading cells. A) Quantification of entotic cells cultured for 4 h with DMSO and the SEPTIN inhibitor, FCF (50 µm). Data represent mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments (n > 300 in each experimental group). B) Immunofluorescence images show endogenous SEPT2 (red) and GFP‐Orai1 (green) in MCF7 cells cultured for 2.5 h in suspension. The arrow indicates enriched SEPT2 at ID. Line graphs show relative SEPT2 (red) and GFP‐Orai1 (green) intensities for the indicated line scans. X axis: 5 µm, Y axis: 1 (A.U.). C) Bar graph showing the distribution of SEPT2 at different engulfment stages. Early‐stage (E, n = 7); middle‐stage (M, n = 9); and late‐stage (L, n = 13). D) Immuno‐fluorescent images of suspended cells taken after 2.5 h of culturing show endogenous SEPT2 (green) and CellBrite (red, PM marker). Line graphs show relative SEPT2 (green) and PM marker (red) intensities for the indicated line scans. X axis: 5 µm, Y axis: 1 (A.U.). E) Fluorescence images of GFP‐SEPT2‐expressing MCF7 cells cultured for 2.5 h in DMSO and FCF (50 µm). Line graphs show the distribution of GFP‐SEPT2 in DMSO (green) and FCF (black dotted). F) Immunofluorescence images showing endogenous SEPT2 (red) and endogenous Orai1 (green) in MCF7 cells cultured for 2.5 h in DMSO or FCF (50 µm). The arrow indicates enriched SEPT2 at ID. Line graphs show the distribution of SEPT2 (red) and Orai1 (green). X axis: 5 µm, Y axis: 5000 (A.U.). G,H) Bar graphs showing the distribution of SEPT2 (G, n = 10) and Orai1 (H, n = 7) at ID in late engulfment stage (from Figure S10, Supporting Information). I) Immunoblots of whole‐cell lysates (left) or IP (right) from cell co‐expressing Flag‐Myc‐Orai1 and GFP‐SEPT2 in HEK293T cells with or without 50 µm of FCF. J) Immunoblots of whole‐cell lysates (left) or IP (right) from cell co‐expressing Flag‐Myc‐Orai1 and GFP‐STIM1 in HEK293T cells with or without 50 µm of FCF and TG (1 µm). Scale bar = 5 µm. Significance was determined using unpaired two‐tailed t‐test. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01. ED: engulfing cell distal region; CC: cell–cell contact site; ID: invading cell distal region.

Next, we checked whether SEPT2, a core component of SEPTIN filaments,[ 26 , 40 , 41 ] might translocate in entotic cells during engulfment. Surprisingly, we found that SEPT2 is also mainly accumulated at CC during the early and middle and translocated to ID at the late stage of engulfment (Figure 5B,C). The subcellular location and translocation patterns of SEPT2 are similar to those of Orai1 and local Ca2+ signaling at different engulfment stages (Figure 5B,C; Figure S9A,B, Supporting Information). Moreover, the polarized localization of SEPT2 was confirmed using cells labeled with cytoplasmic membrane dyes (CellBrite Red, Figure 5D) and cytosol dyes (CellTracker Red, Figure S9C, Supporting Information).

We further confirmed that differential distributions of GFP‐SEPT2 filament structures beneath PM were in MCF7 cells treated with FCF, showing an abnormal GFP‐SEPT2 pattern at CC and ID (Figure 5E). Thus, altered SEPTIN dynamics reduced entosis under FCF conditions (Figure S10A–D, Supporting Information) with abnormal SEPT2 distribution, showing reduced SEPT2 translocation from CC to ID (Figure 5F,G). Thus, SEPT2 might regulate the preferential localization of Orai1 in entotic cells during engulfment, resulting in spatially controlled Ca2+ oscillation. Hence, we investigated whether FCF‐treated SEPTIN altered the local distribution of Orai1 during entosis. Orai1 and SEPT2 were co‐localized in MCF7 cells regardless of FCF treatment, indicating that SEPT2 is a strong Orai1 modulating protein and determines the location of Orai1 in entotic cells. Further, FCF reduced the accumulation of Orai1 at ID in the late stage (Figure 5F,H; Figure S10A,B,E,F, Supporting Information).

To determine whether SEPTINs bind to Orai1 and affect the Orai1‐STIM1 complex, we expressed Flag‐Myc‐Orai1 and GFP‐SEPT2 or GFP‐STIM1, and immunoprecipitated them with Flag‐Myc‐Orai1. FCF reduced the interaction between Orai1 and SEPT2 (Figure 5I). GFP‐STIM1 intensity increases through TG treatment (from 0.38 to 1.05) and decreases through FCF treatment (from 1.05 to 0.63), suggesting that STIM1 and Orai1 interaction is store‐dependent and regulated by SEPTINs (Figure 5J). These data indicated that SEPT2 regulates entotic Ca2+ signaling via Orai1‐SEPT2 and SOCE complex for the local distribution of Orai1.

These results provide the first evidence that SEPTINs are involved in entosis, stabilizing STIM1‐Orai1 complexes, critical for entotic Ca2+ signaling around cell–cell contact and distal membranes of invading cells.

2.10. Local Entotic Ca2+ Signaling of Orai1 Induces the Local Phosphorylation of MLC

Finally, we explored the molecular mechanism by which the entotic Orai1 Ca2+ signaling affects the entotic machinery or target signaling molecules involved in the engulfment processes. We showed that entotic Ca2+ signaling is necessary for the morphological changes in cells which are regulated by actin–myosin mediated cytoskeleton rearrangement during engulfment (Figure 1O,P). Myosin activity of actomyosin is regulated by reversible phosphorylation of conserved amino acids, specifically at serine‐19 in myosin light chain (MLC), and determined by the balance between activities of several kinases like MLCK, ROCK, and myosin phosphatase. We hypothesized that local Orai1 Ca2+ influx might activate Ca2+/CaM/MLCK signaling pathway, resulting in MLC phosphorylation (pMLC) for actomyosin contractility and changes in entotic cell morphology.

First, we evaluated the influence of MLCK on entosis using two MLCK inhibitors, ML‐9 (10 µm) and peptide‐18 (P18, 10 µm). ML‐9 is a classic MLCK inhibitor and P18 is a specific MLCK inhibitor that mimics the inhibitory domain of MLCK by interacting with the catalytic domain of MLCK. MCF7 cells with inhibitors showed reduced entosis efficiency, demonstrating that MLCK activity and phosphorylation of its downstream protein (MLC) might affect entosis (Figure 6A).

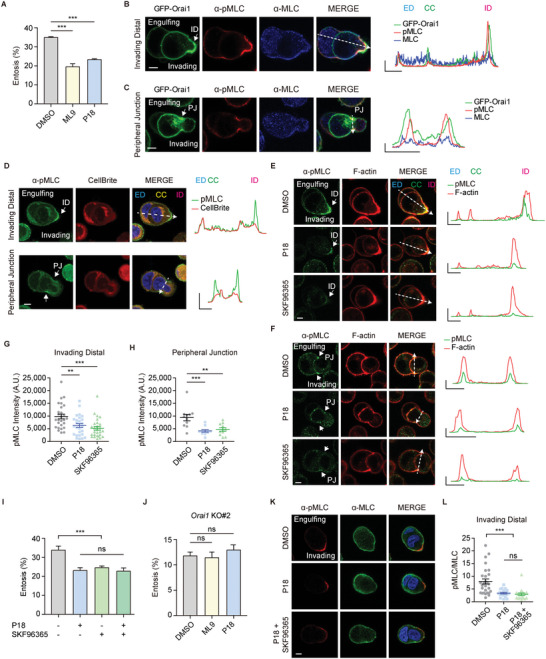

Figure 6.

Orai1 regulates Ca2+/CaM/MLCK mediated phosphorylation of MLC. A) Quantification of entotic cells cultured for 4 h in DMSO and MLCK inhibitors, ML‐9 (10 µm), and P18 (10 µm). Data represent mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments (n > 300 in each experimental group). Significance was determined using unpaired two‐tailed t‐test. ***p < 0.001. B,C) Immuno‐fluorescence images of suspended cells after 2.5 h of culturing show endogenous pMLC (red) and MLC (blue) in GFP‐Orai1‐expressing MCF7 cells. pMLC2 is enriched at ID (B) and PJ (C) compared with total MLC. Line graphs show pMLC, MLC, and GFP intensities for the indicated line scans. X axis: 5 µm, Y axis: 5000. D) Immuno‐fluorescent images of suspended cells taken after 2.5 h of culturing show endogenous pMLC (green) and CellBrite (red, PM marker). Line graphs show relative pMLC (green) and PM marker (red) intensities for the indicated line scans. X axis: 5 µm, Y axis: 1 (A.U.). E,F) Immunofluorescence images of endogenous pMLC (green) and F‐actin (phalloidin, red) cultured with DMSO, P18, or SKF96365 at ID (E) and PJ (F). Line graphs show pMLC and F‐actin intensities for the indicated line scans. X axis: 5 µm, Y axis: 20 000. G,H) Quantification of pMLC2 intensity at ID (G, n = 27 in each group) and PJ (H, n = 11 in each group). Significance was determined using unpaired two‐tailed t‐test. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01. I) Quantification of entotic cells cultured for 4 h in MLCK inhibitors, P18 (10 µm) and SOC channel inhibitor, SKF‐96365 (10 µm). Data represent mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments (n > 300 in each experimental group). Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. ***p < 0.001. ns: not significant. J) Quantification of entotic cells in Orai1 KO MCF7 cell with MLCK inhibitors, ML‐9 (10 µm) and P18 (10 µm). Significance was determined using unpaired two‐tailed t‐test. ns: not significant. Data represent mean ± SEM of triplicate experiments (n > 300 in each experimental group). K) Immuno‐fluorescence images of suspended cells after 2.5 h of culturing show endogenous pMLC (red) and MLC (green) in MCF7 cells. L) Quantification of pMLC/MLC intensity ratio at ID (n = 28, 20, 19). Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. ***p < 0.001. ns: not significant. Scale bar = 5 µm. ED: engulfing cell distal region; CC: cell–cell contact site; ID: invading cell distal region; PJ: peripheral junction.

We also examined the local distribution of pMLC as an indicator of active actomyosin bundles as well as Orai1 entotic Ca2+ mediators during engulfment. Actomyosin, which is asymmetrically enriched and highly active at the ID, drives cell internalizations by providing contractile force. In addition, actomyosin at the peripheral junction (PJ) of engulfing and invading cells maintains the stability of the AJ complex, which occasionally forms a ring‐like structure with F‐actin. Besides, pMLC was colocalized with Orai1 during engulfment and was enriched in ID (Figure 6B; Figure S11A, Supporting Information) and PJ (Figure 6C; Figure S11B, Supporting Information). Moreover, we confirmed the local MLC phosphorylation using cells labeled with cytoplasmic membrane dyes (CellBrite Red, Figure 6D) and cytosol dyes (CellTracker Red, Figure S11C, Supporting Information). These results implicated the role of Orai1 as an entotic Ca2+ mediator for activating actomyosin through local MLC phosphorylation.

We also examined whether Ca2+/CaM/MLCK might affect pMLC in Orai1‐enriched locations within entotic cell pairs using MLCK and SOC channel (Orai1) inhibitors. MLCK inhibitor (P18) or SOC channel blockers (SKF96365) decreased pMLC intensity in ID (Figure 6E,G; Figure S11D–G, Supporting Information) and PJ (Figure 6F,H; Figure S11E,F,H, Supporting Information), indicating that suppressing Orai1/Ca2+ and MLCK reduces MLCK activity and pMLC in entotic Ca2+‐active regions.

To confirm whether SOCE induced entosis through MLCK, we conducted a double inhibition experiment with SOC channel (SKF96365) and MLCK (P18) inhibitors. We compared the efficiency of entosis between cells treated with both inhibitors and against each other. The effects of MLCK and SOC channel inhibitor on the reduction of entosis were not significantly different. In addition, reduced entosis efficiency was not further decreased when both inhibitors were used (Figure 6I). In addition, we checked the effect of MLCK inhibitors on entosis using Orai1 KO cells. The entosis efficiency was not further decreased when two MLCK inhibitors were used in Orai1 KO cells (Figure 6J). Furthermore, we examined the MLC phosphorylation in the double inhibition (Figure 6K,L). MLCK inhibition alone was not significantly different from MLCK and SOC channel double inhibition. Therefore, these results suggest that SOC channel induces entosis through the activation of MLCK.

These findings suggest that Orai1 channel activates CaM/MLCK and myosin (pMLC) in specific cell regions, facilitating engulfment between entotic cells.

3. Discussion

In our study, we demonstrated that Orai1 is a critical Ca2+ channel that induces Ca2+ oscillations during entosis. Orai1 channel is the main pore subunit, but it has two mammalian homologs, Orai2 and Orai3. In addition, Orai1 channel functions as the homomeric or heteromeric channel with other Orai members. Particularly, Orai3 has emerged as a potential fine‐tuner for Ca2+ signaling in a variety of cancer cells, including breast cancer cells MCF7.[ 42 ] Furthermore, several TRP channels were found to have a corporative function with Orai1 in cancer physiology;[ 43 , 44 ] however, their function during entosis remains unknown. Ca2+ signaling mediated by Orai1 is also modulated by several STIM and Orai binding proteins, especially calcium‐dependent proteins such asCaM,[ 45 ] SARAF,[ 46 ] EF‐hand domain family member B (EFHB),[ 47 ] and Cortactin.[ 33 , 48 ] It is, therefore, necessary to investigate the role of Orai1 interacting proteins in entosis in the future.

SOCE activation is dependent on intra‐ER Ca2+ signaling through IP3R, which leads to Ca2+ oscillations during entosis. Entosis is induced via matrix detachment and formation of AJ, which may activate Orai1‐mediated Ca2+ signaling. It has been reported that E‐cadherin ligation stabilizes and activates epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling[ 49 , 50 , 51 ] and activation of EGFR may result in the activation of phospholipase C gamma and ER Ca2+ depletion, resulting in Orai1 mediated Ca2+ influx.[ 52 ] However, several lines of evidence demonstrate that, despite the small conductance of Orai Ca2+ channels and high Ca2+ selectivity, all Orai isoforms are not non‐redundant for the diversity of Ca2+ signaling/oscillations[ 53 ] and all SOCE components are independently involved in the generation of Ca2+ oscillations. Through activation of physical receptors, the diversity of Ca2+ oscillations can be expanded, including activation of Src for cancer invasion and fine‐tuning transcriptional activation of the Ca2+‐dependent transcription factor Nuclear Factor of Activated T‐cell (NFAT).[ 54 , 55 ] Ca2+ oscillations are influenced by positive and negative feedback effects on the Ca2+ release system, which result in fluctuations in IP3 levels or changes in Ca2+ channel activity in intracellular stores.[ 56 , 57 , 58 ] Moreover, IP3 stimulates the IP3R and triggers Ca2+ release from the ER, leading to Ca2+ influx mediated by Orai1, together with our observations that IP3R inhibitor and SERCA inhibitors reduce the entosis efficiency and Ca2+ level during entosis. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the Ca2+ spikes/oscillations, we observed in entosis, would be IP3‐dependent Ca2+ oscillations (which last tens to hundreds of seconds), which are associated with the functional coupling between ER Ca2+ channels (IP3Rs) and PM Orai Ca2+ channels.

During CIC formation, Orai1‐mediated Ca2+ oscillations occur primarily during the early to the mid‐engulfment stage. It is a question inherent in our results that few Ca2+ oscillations were observed in entotic cells following the formation of complete CIC structures (Figure 1I,J). Furthermore, we observed that invading cells displayed Ca2+ oscillations during the escape process from CIC structures, implying that Ca2+ signaling is also necessary for escape, one of the fates of invading cells. Considering that morphological changes in escaping invading cells require cytoskeletal rearrangement, which requires Ca2+ signals, validation of Ca2+ signals in CIC structures would be of interest in determining the fate of entotic cells.

Orai1 KO cells showed a reduced entosis with a dramatic decrease in Ca2+ oscillations (Figure 3E–G), implying that Orai1‐mediated Ca2+ oscillations might be critical but not absolutely essential for entosis. We cannot exclude the possibility of the existence of different types/patterns of Ca2+ oscillations or undetectable levels of Ca2+ oscillations of varying sizes, intensities, shapes, frequencies, and local distributions, caused by other unrecognized Ca2+ pumps, channels, or Orai isoforms (Orai2 and Orai3) present in many types of cells, including MCF7. MCF7 cells express not only Orai1 but also other Ca2+ channels (such as Orai2, Orai3, and TRPC channels) which can be involved in Ca2+ signaling during the entosis; however, there are no studies about Ca2+ channel mediated signalings and whether these Ca2+ signalings may or may not be detected levels of oscillations. Thus, further study is needed to expand our understanding on how diverse Ca2+ signalings are involved in entosis.

It is important to note that both extracellular and intracellular Ca2+ ions and signalings are absolutely essential, particularly during the early stages of engulfment. First, in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, Ca2+ oscillations did not appear, and entosis occurred very rarely in WT MCF7 cells (less than 1%, Figure 1F–H). Second, when extracellular and intracellular Ca2+ were removed from entotic cells which were undergoing entosis, entotic cells ceased to undergo entosis and returned to single cells (Figure 1O,P). Moreover, the Ca2+ ions and oscillations are not critical for the late state, which is determined by more than 2/3 of the engulfment state, because entotic cells are still able to form CIC structures even when the Ca2+ is withdrawn (Figure S3, Supporting Information).[ 11 ] Thus, entosis can be triggered by a variety of signaling events, including physical cell‐cell contact by cadherins and Ca2+ signaling by Ca2+‐handling proteins. Furthermore, during various stages of entosis, individual entotic cells employ a variety of but unknown signaling events; in addition, how Orai1 and other channels cooperate in the progress of entosis will require further investigation.

4. Experimental Section

Cell Lines and Cell Culturing

MCF7 and HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. For transient transfection, the cells were transfected at 70% confluency with 0.2–1 µg DNA using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) or jetPRIME (PolyPlus) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell Internalization Assays and Entosis Quantification

MCF7 cells were cultured for at least three days before the experiment. Monolayer cells were trypsinized to a single‐cell suspension and washed briefly with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Suspended cells (1–2 × 105 cells per mL) were cultured in the indicated conditions (Ca2+ chelation, chemical treatment) for 2–6 h on polyHEMA (Sigma‐Aldrich, 192066) coated plates.[ 1 ] Cells were pelleted at the indicated times, washed in PBS, and fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min at 25 °C. Fixed samples were washed in PBS and stained with Alexa FluorTM 594 Phalloidin (Invitrogen, A12381), WGA‐488 (Invitrogen, W11261), and Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, H3570) for 30 min at 25 °C. To confirm that MCF7 cells were completely internalized by entosis, the cells were examined under a laser‐scanning confocal microscope LSM780 (NLO; Zeiss). Prior to heparin treatment, cells were permeabilized by saponin (10 µg mL−1).

The percentage of entotic cells was determined by quantifying the number of single cells and cell‐in‐cell structures. Cells wrapped at least halfway around neighboring cells were considered to be undergoing entosis. Cell pairs participating in entosis (engulfing and invading cell) were counted as one.

The following Chemicals were used. EGTA (Biopure, 4725E), GdCl3 (Gadolinium (III) Chloride) (Sigma–Aldrich, 439770), AnCoA4 (Sigma–Aldrich, 532999), YM58483 (Cayman Chemical Company, 13246), SKF96365 (Cayman Chemical Company, 10009312), 2‐APB (Cayman Chemical Company, 17146), Heparin (Sigma–Aldrich, H3149), Xestospongin C (Calbiochem, 682160), saponin (Sigma–Aldrich, S7900), Forchlorfenuron (Acros, 45629), ML‐9 (Cayman Chemical Company, 10010236), Peptide‐18 (Cayman Chemical Company, 19181), and Thapsigargin (Cayman Chemical Company, 10 522).

Live Cell Imaging of Cell‐in‐Cell Structures in Soft Agar

To track entosis, cells (2 × 105 cells per mL) were embedded in growth media containing 0.3% low melting agarose and plated on micro‐insert 4 wells in polymer coverslip bottom dishes (ibidi, 80406) coated with polyHEMA. The dishes were centrifuged at 1300 rpm for 1 min and then incubated at 37 °C for 20–30 min to allow the cells to settle down. Time‐lapse microscopy was performed at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in live‐cell incubation chambers.

To analyze entosis time‐lapse progression, fluorescence and differential interference contrast (DIC) images were obtained every 3 s to 5 min for the indicated time courses on a LSM780 (Zeiss) confocal microscope with Zeiss Plan‐Apochromat 63×/1.4 Oil objective lens. mCherry and eGFP (GCaMP6s) were simultaneously excited at 594 and 488 nm, respectively. Fluorescence emission was collected at 615–840 nm (mCherry) and 510–570 nm (eGFP). Zen software (Zeiss) was used for image acquisition. Images were analyzed using Zen or ImageJ software.

Graphs showing low pass filtered normalized GCaMP6s intensity were generated. Raw signals were converted into values relative to the baseline (ΔF/F, where F was the baseline level). Entotic cell pairs consisting of engulfing and invading cells were counted as one. Ca2+ levels 3–5× above the standard deviation were recorded as Ca2+ signals. The time point at which a complete CIC structure was created was set to 0. The 60–0 min period, before complete cell internalized, was defined as “engulfment”. The period from 0 to 60 min after generating the CIC structures, was defined as “Cell‐in‐Cell”.

Immunofluorescence Assay

Monolayer cells were trypsinized to a single‐cell suspension and grown on polyHEMA‐coated plates. Cells were pelleted 2.5 h later and seeded on poly‐ornithine (Sigma–Aldrich, P3655)‐coated cover glass for 10 min. After 10 min, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.02–0.1% Triton X‐100 in PBS for 10 min at 25 °C, and then blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 30 min. After incubating with the indicated antibody for 2–4 h at 25 °C or overnight at 4 °C, the cells were incubated with a conjugated secondary antibody at 25 °C for 1 h. For staining PM, the cells were incubated with CellBrite Red Cytoplasmic Membrane Dyes (Biotium, 30023) at 25 °C for 10 min. For staining cytosol, the cells were incubated with CellTracker Red Dyes (Invitrogen, C34552) at 25 °C for 10 min. For staining F‐actin, the cells were incubated with Alexa FluorTM 594 Phalloidin (Invitrogen, A12381) at 25 °C for 10 min. Last, the nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes) for 10 min. Confocal fluorescence images were acquired using LSM780 confocal microscope (NLO; Zeiss) and LSM980 (Zeiss) with a Zeiss 63× and 100× oil objective lens (NA 1.4 and 1.46, respectively).

Lentivirus‐Mediated Stable Cell Line Construction

HEK293T cells were plated into 12‐well plates. The cells were transfected with lentiviral constructs together with packaging plasmids (VSVg, p8.2). Supernatants were collected 48 h post‐transfection. MCF7 cells were infected with 100–500 µL of lentivirus‐containing medium and incubated for 48 h.

Generation of the Knock‐Out Cell Lines

MCF7 Orai1 KO cells were made with a CRISPR‐Cas9 system. Guide RNA sequences for human Orai1 (sense 5’‐GATCGGCCAGAGTTACTCCGAGG‐3’ and antisense 5’‐ CCTCGGAGTAACTCTGGCCGATC ‐3’) were inserted into the pRGEN vector and pRGEN‐reporter (ToolGen). MCF7 cells were transfected with pRGEN‐Orai1, pRGEN‐Cas9, and pRGEN‐report using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 2 days, transfected cells were selected with 200 µg mL−1 hygromycin (PhytoTechnology Laboratories, ACR0397045A) for 7 days. Cell colonies were isolated after 2–3 weeks. To check for genome editing, the region surrounding the target site of the guide RNA was amplified using PCR (forward primer: 5’‐ATGCATCCGGAGCCCGCCCCGCCCCCGAGC‐3’ and reverse primer: 5’‐CATGGCGAAGCCGGAGAGCAG‐3’). PCR products were subsequently purified via agarose gel extraction and then sequenced. Sequencing of PCR fragments from the Orai1 KO MCF7 cells revealed 1 base‐pair deletion confirming successful Orai1 KO. (KO#1: 12 base‐pair deletion, KO#2: 1 base‐pair deletion, KO#3: 2 base‐pair insertion). Protein expression was confirmed using Western blot analysis. For immunofluorescence assay, CellTracker Red (Invitrogen, C34552) was used for labeling Orai1 KO cells.

Total RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and Reverse Transcription‐PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the isolated cells using RIboEX (GeneAll) following the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of RNA using oligo (dT) primers and First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TOYOBO). PCR amplification was conducted on the C1000 Touch thermal Cycler (Bio‐Rad) using the following amplification conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min and then 35–45 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min; an additional extension at 72 °C for 10 min, 16 °C hold. PCR products were subsequently purified via agarose gel extraction. h.STIM1 (For 5'‐AAGGCATTACTGGCGCTGAACCATGG‐3' and Rev 5'‐ACGGGAAGAATCCAAATGTGGAGAGC‐3'), h.STIM2 (For 5'‐AACGCTGAAATGCAGCTAGCTATTGC‐3' and Rev 5'‐CGTTCTCGTAAACAAGTTGTCAACTC‐3'), h.Orai2 (For 5'‐GGCCATGGTGGAGGTGCAGCTGGAG‐3' and Rev 5'‐GAGTTCAGGTTGTGGATGTTGCT‐3'), h.Orai3 (For 5'‐TGGGTCAAGTTTGTGCCCATTGG‐3' and Rev 5'‐TGCTGCAGACGCAGAGGACCG‐3'), and GAPDH (For 5'‐CTGAACGGGAAGCTCACTGGCATG‐3' and Rev 5'‐AGGTCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGC‐3')

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were scraped into ice‐cold cell lysis buffer (20 mm Tris‐HCL pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X‐100, 0.1% SDS), and lysed for 10 min on ice. Lysates were centrifuged at 12 000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. For soluble protein blotting, samples were mixed with 1/4 volume of 4× reducing sample buffer (200 mm Tris‐HCl (pH6.8), 8% SDS, 0.4% bromophenol blue, 40% glycerol, and 20% β‐mercaptoethanol) and boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. Samples were separated using 10% polyacrylamide SDS‐PAGE and transferred onto 0.45 µm pore size PVDF membranes (Immobilon‐P, Millipore). The membrane was blocked with TBS‐T plus 7% SKIM‐milk and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in TBS‐T plus 3% BSA. Blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)‐conjugated secondary antibodies and detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce). Densitometry analysis was performed using the ImageJ software (NIH).

Immunoprecipitation

HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated constructs for 18 h. Transfected cells were washed three times with PBS and lysed with lysis buffer (20 mm Tris‐HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mm NaCl, and 1% Triton X‐100). Lysates were centrifuged at 12 000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatant was incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti‐Flag M2 agarose beads (Sigma–Aldrich). Lysates and immunoprecipitated samples were run on SDS‐PAGE gels, probed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)‐conjugated secondary antibodies, and detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Antibodies and Protein Detection

Orai1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC‐377281), Orai2 (Alomone, ACC‐061), Orai3 (Alomone, ACC‐065), STIM1 (Abnova, H00006786‐M01), STIM2 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4917S), p‐MLC2 (S19) (Cell Signaling Technology, 3671S), MLC (MilliporeSigma, M4401), GAPDH (proteintech, 60004‐1‐Ig), β‐actin (proteintech, 66009‐1‐Ig; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC‐47778), SEPT2 (proteintech, 60075‐1‐Ig; Novus Biologicals, NBP1‐85212), FLAG (Sigma‐Aldrich, F1804), and GFP (MBL, 598)

Intracellular Ca2+ Imaging

MCF7 cells were loaded with 1 µm of Fluo‐4 AM (Invitrogen) for 30 min at 37 °C. Ca2+ imaging was performed in 0 or 2 mm Ca2+ Ringer's solution with an IX81 microscope (Olympus) equipped with an Olympus × 40 oil objective lens (NA 1.30) and with a fluorescent arc lamp (LAMDA LS), excitation filter wheel (Lambda 10–2; Sutter Instruments), stage controller (MS‐2000; ASI), and a CCD camera (C10600; Hamamatsu) at 25 °C. Images were processed with MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices) and analyzed with excel and GraphPad Prism 5. TG (Cayman Chemical Company, 10522, 1 µm) was used for inducing ER Ca2+ depletion.

The changes in intracellular Ca2+ were determined as mean variation between the Fluo‐4 fluorescence intensities obtained during the stimulus (F) and the resting state (F0), as follows: F–F0.

Statistical Analysis

All generated data were recorded in Excel and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 software. Results are presented as means ± SEM. The student's t‐test was used to determine pairwise statistical significance. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; and *p < 0.05.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

Wrote the manuscript, conceived the study, and designed and interpreted experiments: A.R.L. and C.Y.P. Performed all experiments: A.R.L.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supplemental Movie 1

Supplemental Movie 2

Supplemental Movie 3

Supplemental Movie 4

Supplemental Movie 5

Supplemental Movie 6

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Lab members for supporting research and for helpful discussion. The authors also thank Jinhoe Hur and Hongchan Joung of the UNIST‐Optical Biomed Imaging Center (UOBC) for Microscope technical support. This work was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea NRF‐2018H1A2A1060979 (to A.R.L.), NRF‐2018R1A5A1024340, and NRF‐2019R1A2C2002235 (to C.Y.P.).

Lee A. R., Park C. Y., Orai1 is an Entotic Ca2+ Channel for Non‐Apoptotic Cell Death, Entosis in Cancer Development. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2205913. 10.1002/advs.202205913

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Overholtzer M., Mailleux A. A., Mouneimne G., Normand G., Schnitt S. J., King R. W., Cibas E. S., Brugge J. S., Cell 2007, 131, 966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Durgan J., Tseng Y.‐Y.u, Hamann J. C., Domart M.‐C., Collinson L., Hall A., Overholtzer M., Florey O., Elife 2017, 6, e27134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hamann J. C., Surcel A., Chen R., Teragawa C., Albeck J. G., Robinson D. N., Overholtzer M., Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krajcovic M., Johnson N. B., Sun Q., Normand G., Hoover N., Yao E., Richardson A. L., King R. W., Cibas E. S., Schnitt S. J., Brugge J. S., Overholtzer M., Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mackay H. L., Moore D., Hall C., Birkbak N. J., Jamal‐Hanjani M., Karim S. A., Phatak V. M., Piñon L., Morton J. P., Swanton C., Le Quesne J., Muller P. A. J., Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li Y., Sun X., Dey S. K., Cell Rep. 2015, 11, 358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee Y., Hamann J. C., Pellegrino M., Durgan J., Domart M.‐C., Collinson L. M., Haynes C. M., Florey O., Overholtzer M., Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krishna S., Overholtzer M., Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sun Q., Cibas E. S., Huang H., Hodgson L., Overholtzer M., Cell Res. 2014, 24, 1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ren W., Zhao W., Cao L., Huang J., Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 634849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang M., Niu Z., Qin H., Ruan B., Zheng Y., Ning X., Gu S., Gao L., Chen Z., Wang X., Huang H., Ma L.i, Sun Q., Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 108071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Florey O., Kim S. E., Sandoval C. P., Haynes C. M., Overholtzer M., Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sun Q., Luo T., Ren Y., Florey O., Shirasawa S., Sasazuki T., Robinson D. N., Overholtzer M., Cell Res. 2014, 24, 1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Purvanov V., Holst M., Khan J., Baarlink C., Grosse R., Elife 2014, 3, e02786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berridge M. J., Bootman M. D., Roderick H. L., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clapham D. E., Cell 2007, 131, 1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen Y.‐F., Chen Y.‐T., Chiu W.‐T., Shen M.‐R.u, J. Biomed. Sci. 2013, 20, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bagur R., Hajnóczky G., Mol. Cell 2017, 66, 780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prakriya M., Feske S., Gwack Y., Srikanth S., Rao A., Hogan P. G., Nature 2006, 443, 230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Feske S., Gwack Y., Prakriya M., Srikanth S., Puppel S.‐H., Tanasa B., Hogan P. G., Lewis R. S., Daly M., Rao A., Nature 2006, 441, 179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang S. L., Yu Y., Roos J., Kozak J. A., Deerinck T. J., Ellisman M. H., Stauderman K. A., Cahalan M. D., Nature 2005, 437, 902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang S., Zhang J. J., Huang X.‐Y., Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prakriya M., Lewis R. S., Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hogan P. G., Cell Calcium 2015, 58, 357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. La Rovere R. M. L., Roest G., Bultynck G., Parys J. B., Cell Calcium 2016, 60, 74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mostowy S., Cossart P., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bridges A. A., Jentzsch M. S., Oakes P. W., Occhipinti P., Gladfelter A. S., J. Cell Biol. 2016, 213, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lobato‐Márquez D., Mostowy S., J. Cell Biol. 2016, 213, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sharma S., Quintana A., Findlay G. M., Mettlen M., Baust B., Jain M., Nilsson R., Rao A., Hogan P. G., Nature 2013, 499, 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lioudyno M. I., Kozak J. A., Penna A., Safrina O., Zhang S. L., Sen D., Roos J., Stauderman K. A., Cahalan M. D., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aoki K., Harada S., Kawaji K., Matsuzawa K., Uchida S., Ikenouchi J., Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tsai F.‐C., Seki A., Yang H. W., Hayer A., Carrasco S., Malmersjö S., Meyer T., Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lopez‐Guerrero A. M., Espinosa‐Bermejo N., Sanchez‐Lopez I., Macartney T., Pascual‐Caro C., Orantos‐Aguilera Y., Rodriguez‐Ruiz L., Perez‐Oliva A. B., Mulero V., Pozo‐Guisado E., Martin‐Romero F. J., Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen Y.‐T., Chen Y.‐F., Chiu W.‐T., Wang Y.‐K., Chang H.‐C., Shen M.‐R.u, J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen T.‐W., Wardill T. J., Sun Y.i, Pulver S. R., Renninger S. L., Baohan A., Schreiter E. R., Kerr R. A., Orger M. B., Jayaraman V., Looger L. L., Svoboda K., Kim D. S., Nature 2013, 499, 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sadaghiani A. M., Lee S. M., Odegaard J. I., Leveson‐Gower D. B., Mcpherson O. M., Novick P., Kim M. R., Koehler A. N., Negrin R., Dolmetsch R. E., Park C. Y., Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lopez J. J., Albarran L., Gómez L. J., Smani T., Salido G. M., Rosado J. A., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Katz Z. B., Zhang C., Quintana A., Lillemeier B. F., Hogan P. G., Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hu Q., Nelson W. J., Spiliotis E. T., J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 29563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sidhaye V. K., Chau E., Breysse P. N., King L. S., Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011, 45, 120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Valadares N. F., D’ Muniz Pereira H., Ulian Araujo A. P., Garratt R. C., Biophys. Rev. 2017, 9, 481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Motiani R. K., Abdullaev I. F., Trebak M., J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 19173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ong H. L., Cheng K. T., Liu X., Bandyopadhyay B. C., Paria B. C., Soboloff J., Pani B., Gwack Y., Srikanth S., Singh B. B., Gill D., Ambudkar I. S., J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 9105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liao Y., Erxleben C., Yildirim E., Abramowitz J., Armstrong D. L., Birnbaumer L., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu Y., Zheng X., Mueller G. A., Sobhany M., Derose E. F., Zhang Y., London R. E., Birnbaumer L., J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 43030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jha A., Ahuja M., Maléth J., Moreno C. M., Yuan J. P., Kim M. S., Muallem S., J. Cell Biol. 2013, 202, 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Albarran L., Lopez J. J., Jardin I., Sanchez‐Collado J., Berna‐Erro A., Smani T., Camello P. J., Salido G. M., Rosado J. A., Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 51, 1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lopez‐Guerrero A. M., Tomas‐Martin P., Pascual‐Caro C., Macartney T., Rojas‐Fernandez A., Ball G., Alessi D. R., Pozo‐Guisado E., Martin‐Romero F. J., Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pece S., Gutkind J. S., J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 41227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rayavarapu R. R., Heiden B., Pagani N., Shaw M. M., Shuff S., Zhang S., Schafer Z. T., J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 8722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sharma A., Elble R. C., Biomedicines 2020, 8, 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vandenberghe M., Raphaël M., Lehen'kyi V., Gordienko D., Hastie R., Oddos T., Rao A., Hogan P. G., Skryma R., Prevarskaya N., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, E4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Emrich S. M., Yoast R. E., Xin P., Arige V., Wagner L. E., Hempel N., Gill D. L., Sneyd J., Yule D. I., Trebak M., Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sun J., Lu F., He H., Shen J., Messina J., Mathew R., Wang D., Sarnaik A. A., Chang W.‐C., Kim M., Cheng H., Yang S., J. Cell Biol. 2014, 207, 535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yoast R. E., Emrich S. M., Zhang X., Xin P., Johnson M. T., Fike A. J., Walter V., Hempel N., Yule D. I., Sneyd J., Gill D. L., Trebak M., Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Berridge M. J., Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Politi A., Gaspers L. D., Thomas A. P., Höfer T., Biophys. J. 2006, 90, 3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fewtrell C., Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1993, 55, 427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supplemental Movie 1

Supplemental Movie 2

Supplemental Movie 3

Supplemental Movie 4

Supplemental Movie 5

Supplemental Movie 6

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.