Abstract

Objective

To illustrate the views of chief physicians in Finnish primary healthcare health centres (HCs) on the existing research capacity of their centres, their attitudes to practice-based research network activity, and research topics of interest to them.

Design

A cross-sectional survey study.

Setting

Finnish HCs.

Subjects

Chief physicians in Finnish HCs.

Main outcome measures

We used a questionnaire that included five-point Likert scales and multiple choice and open-ended questions to identify the chief physician’s profile, the HC content, the attitudes of chief physicians towards engagement in research, research topics of interest to them, and factors that may influence their motivation. Descriptive methods were used for the analysis of the quantitative data, while the qualitative data were processed using inductive thematic analysis.

Results

There was a relatively good representation of all hospital districts. One-third of HCs had at least one person doing research, and 61% of chief physicians would support research in their setting. Their stimulus for research was primarily testing new therapies, protocols, and care processes, as well as effectiveness and healthcare improvement. The expected benefits that motivate engagement in Practice-based research networks (PBRNs) are evidence-based practice and raised professional capacity and profile of the HC.

Conclusions

Chief physicians regard research as an elementary part of the development of primary care practices and health policy. Their motivation to engage in PBRN activity is determined by the relevance of the research to their interests and the management of competing priorities and resource limitations.

Keywords: Practice-based Research Network, primary care, general practice

KEY POINTS

The chief physicians of the Finnish primary healthcare centres (HCs) recognize the value of practice-based research and are motivated to participate in practice-based research network activity if:

• The research topics are relevant to their interests and problems encountered at their HC;

• The research activity entails tangible benefits for their HC, such as evidence-based practice and improvement, an increase in professional competence, or an improvement in HC image;

• It is possible to cope with competing priorities and resource limitations.

Introduction

The evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that health systems oriented towards general practice and primary healthcare produce better health outcomes at lower costs and with higher user satisfaction [1].

According to the European General Practice Research Network (EGPRN)Research Agenda, a key concept in improving the quality, quantity, and impact of primary care research is research capacity building (RCB) [2]. RCB is crucial at the individual, organizational, and environmental levels [2]. The development of primary care is directly associated with integrating a robust research component through research education and engagement in practice-based research networks (PBRNs) [3,4]. PBRNs are partnerships of primary care practitioners with experienced researchers engaged in asking clinical and organizational questions about primary healthcare and providing relevant and applicable evidence to improve clinical practice and quality of care [5,6].

PBRNs operate as laboratories of primary care and have the capacity to implement a broad variety of studies on topics such as clinical and comparative effectiveness, public health, quality improvement (QI), health services, and translational research [7,8]. They provide a cost-effective interface to conducting high-quality research, produce broadly generalizable outcomes [5,8], and operate as bidirectional conveyors in research translation [8]. PBRNs empower practitioners through learning communities that share knowledge and best practices and facilitate QI [9,10]. PBRNs also considerably influence health policy guidelines with their evidence-based outcomes [11,12].

Europe has been the cradle of PBRNs with the Weekly Returns Service in the UK [13], which started in 1966, and the Nijmegen Continuous Morbidity Registration, which was launched in 1967 [14]. Most of the Nordic countries have also fostered PBRN activities [15–17]. The Tutka PBRN started in Finland in 2015 and engages 23 primary healthcare health centres (HCs) situated mainly in western Finland [16]. A recent Finnish study found that PhD education, which endows general practitioners (GPs) with research skills, is quite sparse in primary healthcare compared to other specialties, and the intention to increase it has only slightly increased over ten years. In addition, the GPs did not foresee research in their work in the future [18]. Government policy in Finland supports the funding of the development of data-intensive research methods in healthcare and the career tracks of clinical researchers, although it does not explicitly suggest PBRN activity [19].

PBRNs have typically been built by a core of research-motivated clinicians [14,20–22]. The recruitment of practices with established relationships with academia due to training and research has been a common pathway to set up a network [21,23,24]. In addition, PBRNs have provided value-added incentives to their members to maintain their motivation for research participation [25–27]. However, studies show that the intrinsic motivation of practitioners to participate in a bigger effort to improve healthcare underlies their motivation to participate in research [21,28]. Challenges related to the recruitment of practices include a low interest in proposed research topics, limited expertise in research, competing priorities in the practices [29–30], practice turnover [24,31–33], and the lack of dedicated time for research [24,34]. Surveys have been developed to strategically sustain the early development of PBRNs that investigate the research capacity, the research motivation of the practitioners, the facilitators and barriers for research engagement among the members [7], and the most interesting topics for research [35].

Addressing the knowledge gap about research experience, interests, and motivation in Finnish HCs, we deployed a survey for the chief physicians leading HCs in Finland. Our inquiry focuses on the chief physicians because to our knowledge, their stance towards practice-based research may be considered a strong determinant of the facilitation of the activity in the Finnish context. Besides, previous research has demonstrated the importance of a positive stance towards research from the institutional leadership of practices [36–37].

The aim of the survey was to gather information about chief physicians’ views on the existing research capacity, the attitudes to practice-based research, and the most compelling research topics for the HCs in Finland.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional survey using both quantitative and qualitative methods to analyse the results. The material consists of survey responses from chief physicians who lead the HCs. Approval for this study was received from the five academic departments of General Practice in Finland. The setting for this study was all the HCs in Finland. We sent invitations to fill out an electronic survey developed in the Microsoft 365 Forms environment to 125 of the 126 HCs that exist in Finland. We lacked the contact information of three outsourced health centres. As we did not find an existing questionnaire matching all of our aims in a literature review, we devised our questionnaire (see Questionnaire on Supplemental online material) with items found in previous surveys [24,38] and the findings of a recent global research study [7] on PBRN establishment. The final questionnaire was processed by all the members of the research group to meet the objectives of this inquiry. Thus, this survey was designed to identify: (i) the chief physicians’ profile and the content and the existing research experience in HCs; (ii) the attitudes of chief physicians towards engagement in research at their HC, and the factors that may influence their decisions; and (iii) research topics of interest to the chief physicians. The questionnaire included questions using a five-point Likert scale, multiple-choice and open-ended questions.

The open-ended questions were used to gather qualitative data to gain better insight into the factors affecting the research motivation among the Finnish chief physicians. The questionnaire, albeit anonymized, enabled the collection of the contact information of ‘research champions’ who might comprise the core members of the expanded Tutka PBRN in the future.

On 18 March 2021, the survey attached to an invitation email was sent by the academic professors to the chief physicians of HCs in their university hospital district. Reminders were sent twice in April 2021.

Our survey yielded 65 responses. Due to the small sample size, we report our results using mainly descriptive statistics and we applied cross-tabulation where it was relevant. The qualitative data derived from the open-ended questions are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The three open-ended questions of the survey.

| (i) ‘What issue(s) do you need more information about at your health centre? (related to diagnostics / treatment / change of function / something else?)’ (ii) ‘What benefits do you see from the research for your health centre?’ (iii) ‘Would your health centre be willing to join the researcher health centre network and participate through the network in scientific research on primary healthcare in the future? (Where the choices were “yes”, “maybe”, “I don’t know what to answer”). If you answered “yes” or “maybe” to the previous question, what influenced your positive answer?’ |

Each question provided narratives that we elaborated on separately. We processed the narratives using inductive thematic analysis. In this approach, codes, subthemes, and themes are suggested by the data rather than by a theoretical framework [39]. The steps we used for our analysis were an iterative process to familiarize ourselves with the qualitative data and to identify quotations with common concepts, the grouping of the concepts into subthemes and themes, and the creation of an explanatory thematic summary. All co-authors (AD, TK, PM, MS) participated in this process, working first independently with the quotations and then comparing the analyses to develop a consensus.

Ethics approval: This is an anonymized survey (non-interventional study), and ethical approval is not required according to Finnish regulations on research ethics [40].

Results

Quantitative results

We received 65 responses (response rate 52%). The most prominent group of responders were specialized in general practice, and almost a third of them had one or more higher academic degrees. Fifty-four of the 65 respondents 83% were involved in developmental work in the HC. The responder characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Responders’ characteristics.

| Characteristics of responders (n = 65) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <30 | 0 (0%) |

| 30–39 | 13 (20%) |

| 40–49 | 18 (28%) |

| 50–59 | 25 (38%) |

| ≤60 | 9 (14%) |

| Gender | |

| Women | 35 (54%) |

| Men | 30 (46%) |

| Native language | |

| Finnish | 61 (94%) |

| Swedish | 2 (3%) |

| Other | 2 (3%) |

| Degrees of higher education* | |

| Master’s degree | 1 (2%) |

| Leadership education (e.g. MBA) | 7 (11 %) |

| PhD in medical science | 7 (11%) |

| Other PhD | 0 (0%) |

| No other degrees | 41 (63%) |

| Docent | 1 (2%) |

| Other | 14 (22%) |

| Professional activity at the health centre | |

| Managerial duties | 61 (94%) |

| Administrative duties | 64 (98%) |

| Patient care consultation | 34 (52%) |

| Other clinical work | 17 (26%) |

| Research | 4 (6%) |

| Development work | 54 (83%) |

| Training specializing doctors or other trainees | 34 (52%) |

| Other | 9 (14%) |

| Tenure at HCs (total work experience) | |

| <5 | 3 (5%) |

| 5–9 | 8 (12%) |

| 10–19 | 27 (42%) |

| 20–29 | 13 (20%) |

| ≤30 | 14 (22%) |

*Some chief physicians had more than one higher education degree.

The HCs that participated in our survey varied by population (from 3,100 to 200,000 patients), but two-thirds of them were of average size. The HC characteristics are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the participating HCs.

| HCs (n = 65) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| HCs per served population | |

| <10,000 | 14 (21%) |

| 10–50,000 | 44 (68 %) |

| >50,000 | 7 (11 %) |

| HCs per hospital districts | |

| Helsinki (HUS) | 10 (15%) |

| Tampere (TAYS) | 17 (26%) |

| Turku (TYKS) | 11 (17%) |

| Kuopio (KYS) | 17 (26%) |

| Oulu (OYS) | 10 (15%) |

| Locality of practices | |

| Rural | 22 (34%) |

| Sub-urban | 28 (43%) |

| Urban | 15 (23%) |

| Number of physicians | |

| <10 | 22 (34%) |

| 10–20 | 20 (31%) |

| >20 | 23 (35%) |

| Number of trainee doctors | |

| <10 | 47 (72%) |

| 10–20 | 12 (18%) |

| >20 | 4 (6%) |

| I don’t know | 1 (2%) |

| GP Specialists | |

| <10 | 53 (82%) |

| 10–20 | 8 (12%) |

| >20 | 4 (6%) |

Sixty-four of the 65 HCs were involved in medical education and basic training for medical students. The data show that 6% considered that they had an abundance of doctors, 18% had an adequate number of doctors, 40% had a rather sufficient number of doctors, and 35% reported a scarcity of doctors.

The surveyed Finnish HCs use a variety of electronic health records (EHRs). The 20% of the centres were able to extract data automatically, 43% from their organization’s staff, and 14% by drawing on data from a regional database. However, the majority of the HCs who plan to change EHR in the next 18 months had not considered specifications for research data from the new EHR, with only one exception.

Current involvement in research in HCs and attitudes of chief physicians towards research activity at their centre

Every third HC had one or more professionals involved in scientific research with external funding, but more than half did not engage in research. In the previous 12 months, the HCs had been involved in studies related to diabetes, elderly care, chronic pain, and patient-care effectiveness. Fourteen of these studies used EHR data only or in combination with other data sources. Eleven of these studies were planned to be continued for the next twelve months, while four HCs planned to start new research.

When the chief physicians were asked whether the professionals working at their HC had the resources to conduct research during working hours, 30% of them replied that they agree fully or to some extent, and 61% of them would encourage their doctors to engage in research. In these categories were sixteen of the 22 HCs with a reported insufficient number of doctors, and 17 HCs reporting a lack of resources (time and support) for research.

In addition, the use of cross-tabulation showed that previously conducted research in a health centre was associated with the HC’s willingness to participate in PBRN (70% vs. 29%, p < .05). Furthermore, the population size of the health centre, in favour of a bigger population, was associated with the health centre’s willingness to participate in PBRN (59% vs. 28%, p < .05).

Research motivation, intention to engage in PBRN activity related to research domains, and important research topics

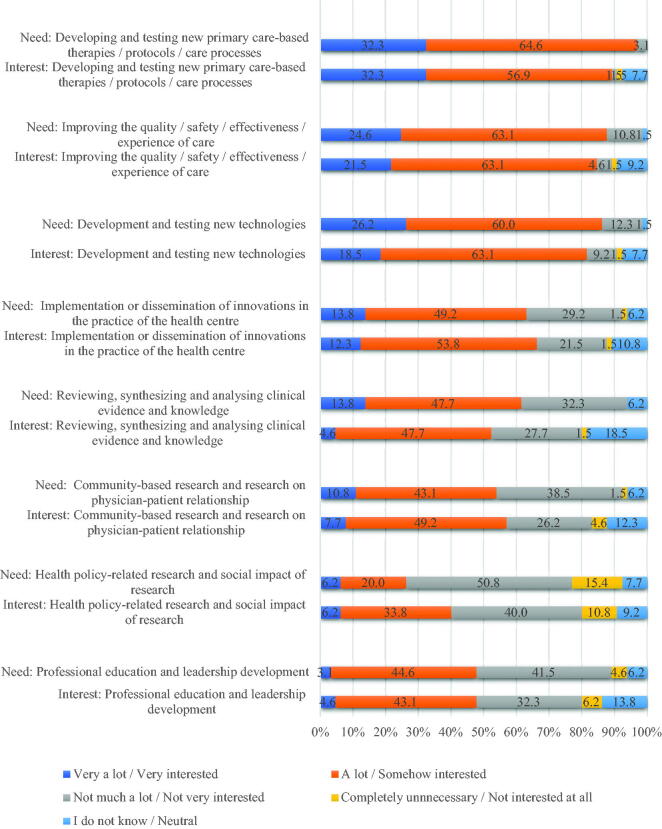

Research related to developing and testing new primary care-based therapies, protocols, and care processes were of prime importance among the surveyed chief physicians, while the least interesting research domain was health policy-related research and the social impact of research. The need for specific research topics and the chief physicians’ interest in engaging in corresponding research diverged slightly (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The needs and interests of health centres regarding research in descending order (%).

Qualitative results

The qualitative results of this survey were captured from the narratives of the responses to the three open-ended questions in Table 1. The outcomes of these different analyses are presented separately in the following three subsections. The qualitative results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Main results of the thematic analysis of the three open-ended questions with representative narratives.

| Question (i) ‘What issue (s) do you need more information about at your health centre? (related to diagnostics “treatment” change of function “ something else?”)’ | ||

|---|---|---|

| Themes: | Subthemes: | Narratives: |

| Increase patient and population benefits | Health benefits for population | ‘Appropriate work schemes that provide health benefits to the population’ |

| Patient satisfaction | ‘How operational changes and new team models affect the quality of care, patient satisfaction…’ | |

| Continuity of care | ‘Continuity is a clear priority, but the relationships to increase the continuity of care are surprisingly difficult to achieve.’ | |

| Patient segmentation | ‘What groups of patients should be invited to treatment and who can treat their health independently with the support of self-care?’ | |

| Effectiveness and improvement of care | Effectiveness of operating models | ‘The effectiveness of the time spent by professionals on patient contact (quick one-case visit vs longer holistic contact).’ ‘Evidence-based information on the effectiveness of different operating models (team models, job transfers between different professionals, etc.) on patient care.’ |

| Effectiveness of digital and remote services | ‘New digital services. Impact on new ways of working.’ ‘Information on the effectiveness of telemedicine – what can really be replaced.’ ‘Testing new technologies and development.’ |

|

| Improvement of quality of care | ‘What action is useless or less successful?’ ‘Effectiveness and measurement of the quality of operations.’ |

|

| Clinical Effectiveness | Effectiveness of treatments and interventions | ‘Treatment interventions at the health centre to avoid providing ineffective things.’ ‘On effectiveness of treatments.’ ‘(Testing) New treatments.’ |

| Diagnostics | ‘Diagnostics related to treatment.’ | |

| Effective resource allocation/financial modelling use | Effective use of resources, cost-effectiveness, financial models for primary care | ‘Cost-effectiveness. Whether the existing resources are used correctly.’ ‘Effective use of resources and assets when implementing new practices.’ ‘How to change the funding model of SHC + PHC joint organizations so that prevention would also be affordable for the organization’s finances?’ |

| Practice organizational issues at the HCs and staff’s capability | Organizing collaboration models for HCs | ‘Well-organized collaboration between professional groups is another challenge of management (…) collaboration is desired, but decision-making is slow.’ |

| |

Improving skills and adaptability among practice professionals |

‘How best to support staff resilience and skills?’ ‘Education on financial management.’ ‘Evaluation of change in activity.’ |

| Question (ii): What benefit do you see from the research for your health centre? | ||

| Themes: | Subthemes: | Narratives: |

| Benefits from evidence-based practice in the HC enterprise | Research is necessary for evidence-based practice and the quality improvement of clinical practice and care | ‘Healthcare is undergoing a transformation. It would be good to research and find well-functioning models.’ ‘Improving the process, rationalizing the treatment path, eliminating unnecessary waiting time for both patients and staff.’ ‘Strengthening the scientific basis for the development of care and activities.’ |

| Implementation of evidence-based knowledge management | ‘Knowledge-based management becomes more efficient, unnecessaries are reduced, and work conditions in the service are improved.’ ‘The problems are revealed. Successes are more visible.’ |

|

| Benefits for the primary care professionals and other ancillary benefits for HCs and healthcare | Increases evidence-based practice implementation, upgrades professional competence and pride | ‘The primary benefit is for us, the professionals, to understand what we should do, as far as possible, based on research evidence about its effectiveness and not just justify ‘what we have always done’ or ‘because the patient so desires’. Participation in research would clarify those issues.’ ‘Development of better operations. Professional growth (participation in research) gives GPs ‘shoulders’ to participate on an equal footing in stakeholder development (care chains, delegation of tasks, national networks, etc.).’ ‘In principle, I would like to support young colleagues to do research. This would increase professional pride. I would like to activate young people to participate in developing their own work.’ |

| Raising the image of HCs / increase the attractiveness of the job in HCs | ‘Profile upgrading, attractive place to work when recruiting (…)’ ‘Encouraging those interested in research to work here.’ ‘It might increase job satisfaction and commitment?’ |

|

| Bringing research out of the ivory tower and closer to the community | ‘Increasing the understanding of professionals that research work can be done in everyday life everywhere, not just in laboratories or other university research chambers. In addition, it would be important to understand that research work is valuable, even if it is seemingly ‘more modest’, e.g. creating hypotheses.’ | |

| Concerns about research participation |

|

‘The topic is interesting, but in everyday life it seems that no one really has the resources or forces to do things related to research. There is a heavy workload to maintain the statutory care.’ |

| Question (iii): Would your health centre be willing to join a practice-based research network and participate in primary healthcare research with this network in the future? If you answered ‘yes’ or ‘maybe’ to the previous question, what affected your positive answer? | ||

| Themes: | Subthemes: | Narratives: |

| Needs for practice-based evidence for the HC enterprise | Need for evidence-based knowledge management and solutions | ‘We do a lot for developing knowledge-based management and ‘study’ the effectiveness of care. It would also be great to have an academic evaluation, for example, of measuring the effectiveness of activities.’ |

| Research is necessary for evidence-based clinical and service decision-making | ‘More health centre research would definitely be needed, because that would provide information on the discrimination of the patient population.’ ‘Are the right things being done / Cost-effectiveness in health decision-making. Whether existing resources are used correctly – Development and testing of new treatments, practices, or care processes in primary care.’ ‘Primary healthcare research is becoming increasingly important in the face of fragmented medicine and SOTE reform.’ |

|

| Research is necessary to develop and improve the quality of health service/care | ‘In general, healthcare always benefits from doing research, and therefore it is worthwhile, and this could be helpful for my own development work.’ ‘Through research, it is possible to develop quality improvement in services.’ |

|

| Positive attitude towards research and PBRN activity | Need for collaborative research | ‘We are planning studies that also require collaboration. It is not possible to conduct research without networks.’ ‘We want to work together in development activities and influence by bringing the working conditions of small municipalities to the fore. I also believe that in a larger organization, there are some things to learn from the creative solutions of small actors.’ |

| Positive attitude towards research | ‘I very much welcome research and nationwide healthcare in the face of such severe pressures and challenges …’ ‘I consider this important, and a lot would be achievable that would benefit the HC.’ ‘In previous job positions, I have successfully promoted research activity in the HC, good experiences from it.’ |

|

| The HC is a PBRN member | ‘We are already registered with Tutka.’ | |

| Expectations for a positive impact on recruitment, profile, and job satisfaction in HCs | ‘Could attract skilled doctors to work at the centres.’ ‘The staff would have a multifaceted job and a growing interest in work.’ |

|

| Challenges and barriers to engaging in research | ‘Only if time / resources are enough.’ ‘On the other hand, the shortage of doctors does not allow for this.’ |

|

Primary healthcare issues to address through research

The answers to question (i) in Table 1 captured topics that would be important to investigate through research. Our analysis yielded the themes ‘Increase patient and population benefits’, ‘Effectiveness and improvement of care’, ‘Clinical effectiveness’, ‘Effective resource allocation/financial modelling use’, ‘Practice organizational issues at the HCs and staff’s capability’, and the 12 subthemes presented in Table 4. The concepts of effectiveness, patient and population benefits and care improvement were issues repeated in the narratives of this theme.

Reasons to engage in PBRN research and expected benefits

The motivation to engage in research and relevant barriers emerged from the open-ended question (iii) in Table 1 and were grouped into three main themes: ‘Needs for practice-based evidence for the HC enterprise’, ‘Positive attitude towards research and PBRN activity’, ‘Challenges and barriers to engaging in research’, and the 8 sub-themes presented in Table 4. Positive attitudes towards research were related to previous research experience, the belief that research is beneficial for the HC, and the infusion of research awareness into new generations of GPs. In the third theme, the challenges and barriers included time, human resource limitations, and competing priorities in their settings.

The expected benefits from practice-based research activity in the HC setting were conceptualized by applying thematic analysis to the answers yielded from question (ii) in Table 1, and this produced three themes: ‘Benefits from evidence-based practice in the HC enterprise’, ‘Benefits for the primary care professionals, and other ancillary benefits for HCs and healthcare’, and ‘Concerns about research participation’, along with 6 subthemes presented in Table 4. In one narrative, the expected benefits from research were connected with job satisfaction and the commitment of professionals working in the HCs, while in another, the importance and value of doing research in real-life conditions were underscored. The third theme presented challenges related to resources (time and doctors) and workload.

Discussion

Principal findings

Our survey findings suggest that the most important research topics for Finnish chief physicians involve various aspects of effectiveness, the improvement of patient and population healthcare, and the improvement of organizational management. The analysis showed that the term ‘effectiveness’ was often repeated in the narratives, while the intention for healthcare improvement through evidence-based practice was also strongly present. Thus, we deemed that various issues of effectiveness and improving patient care and services to be of primary interest to the chief physicians.

Chief physicians’ motivation to engage in research is related to the belief that practice-based evidence is essential for the operation, knowledge management, and development activities of HCs. This is especially the case as the majority of these leaders are involved in developmental work at their centre. They also consider research collaboration to be necessary, and their positive attitudes are augmented by previous experiences from research and the expectation that research may increase the profile and job satisfaction at HCs.

In the qualitative part of the study, we observed that the thematic content of the themes ‘Needs for practice-based evidence for the HC enterprise’, and ‘Benefits from evidence-based practice in the HC enterprise’ included some equivalent concepts that correspond to each other about the needs for research and the expected benefits. Similarly, the positive attitude towards research and PBRN activity included expectations that research may have a positive impact on HCs in terms of recruitment, profile, and job satisfaction, while the expected benefits for HCs included expectations about raising the image and the attractiveness of the job in HCs. This may indicate that chief physicians’ motivation to engage in research was related to the expected benefits for their HC through evidence-based practice, management, and improvement of care; increased competence and growth of primary care professionals; a raised profile for the HCs; and increased job satisfaction. This is concordant with the extended literature review findings, which support PBRNs nurturing reciprocal benefits for their members (practitioners or practices) [7]. Barriers to engaging in research were a lack of time, limited human resources (doctors), and competing priorities in their settings. These barriers were similar to those listed in publications from other countries [7]. The use of EHRs for research purposes seems to be a problem for Finnish HCs, although many of them may extract data from their EHRs somehow. Besides, there is a lack of preparedness, according to our survey, in new EHRs installations with specifications for research data recording or extraction in the near future.

The majority of Finnish HCs are medical training centres. In addition, one-third have been involved in research and those, according to our findings, were more motivated to engage in research again. Although our data did not illustrate the level of staff engagement or other estimates of the research capacity of these HCs, they show that there is potential to build upon. The literature demonstrates that PBRNs were built by leveraging relationships with training-, residence-, and research-experienced practices. [41–43]. Moreover, in many cases, the networks explicitly stated that they set as a priority research capacity-building activity already from the 1990s [44–47], and some built research-designated practices as part of more robust research infrastructures [23,48–50].

The previous papers state that practice-based research is essential for the HC enterprise [3,51], and it is connected with job satisfaction and retention in the centres [52–53], appreciation of general practice [4,54], and the professional growth of primary care professionals [3,7,51]; these findings are in line with ours. According to our results in the Finnish context, chief physicians believe that ‘effectiveness’ studies could make an impact on practice, policy politicians, and possibly on other stakeholders. PBRN data have been used broadly for a variety of effectiveness studies informing policy, but also in practice improvement [55–57]. This is a critical step of PBRN common practices, which engage these categories of stakeholders, securing their impact, funding, and sustainability [5,11,58].

At the time of this study, Finnish primary care was organized by the municipalities, which arranged broad primary care services from multidisciplinary outpatient care to preventive services and towards mainly for geriatric patients. Secondary care was organized separately by the hospital districts. The respondents of this survey underscored the need for evidence-based development in an environment of administrative and operational changes in primary care, before the launch of the social and healthcare reform in the country.

This reform introduces new challenges, as the social and healthcare system is to be organized from the beginning of 2023 separately into 21 counties with independent healthcare systems, which will have their countywide data registries and data pools. This entails that the aggregated data within a county may be used for research locally, while linking data between different counties requires the permission of a national organization, which charges for the use of the data [59]. This may result in increased costs for national primary care studies but may increase the ease of data use within the counties. The anonymized, routinely recorded data of EHRs are a valuable source for primary care research, and the EHR data should be available for studies and learning in healthcare systems [60]. Higher-level advocacy of the value and ownership of primary care data with policymakers [61] and collaborative relationships with health information technology vendors to achieve research-friendly EHRs and data [31] would be a recommendation based on other countries’ experiences.

Strengths and limitations

In this survey, we investigated the capacity of HCs with a focus on research, and we highlighted the attitudes of the chief physicians leading Finnish HCs regarding practice-based research and research topics of interest. Our survey had a relatively good representation of all the university hospital district health centres and a good response rate, which adds value to our findings. Due to the small sample size, we reported our results using descriptive statistics and we used cross-tabulation with variables whose values were dichotomized. Moreover, our results are congruent with the previous literature, which lends strength to their veracity.

Nevertheless, our study yielded results from 52% of HCs in Finland. It is possible that the HCs’ reflections may be an overestimate and are not outcomes of a representative sample of all Finnish HCs, but this is a common risk of selection bias.

This study reflects the chief physicians’ opinions and not the whole practice’s opinion. However, we decided to gather data from the leaders of the HCs in Finland because we assumed that the attitudes of the leaders strongly determine the participation of a HC in research.

The qualitative parts, which we used in the thematic analysis, were derived from the open-ended questions of the survey. The responses were very brief, albeit in most cases comprehensive and valuable for planning action.

Interpretation bias may occur with thematic analysis, although themes, sub-themes, and codes were conceptualized through consensus by all co-authors.

Implications

The Finnish chief physicians in our survey seem to recognize the value of practice-based research. This may convey the message that chief physicians agree with research activity in the Finnish primary healthcare setting to improve healthcare operations if the resources are sufficient and the research is deployed in topics that are meaningful and beneficial for the HC operation. PBRN research could step up as a collaborative effort between HCs and academics. Research champions in the HCs can support this initiative in primary care. The identified research domains in this survey may be used as a foundation for pinpointing more precisely topics of interest through focus group discussions among clinicians or by another relevant method. The national healthcare reform increases the urgency for practice-based research and innovation implementation in primary care settings. This may endow the expanded PBRN activity with a track record in Finland. The separate data registries in different counties require primary care data validation, and that should be the next step in establishing robust and compatible (interoperating) primary care research databases with different levels of the locality to conduct research.

Considering the research-motivated HCs that came to light in our research, there is an opportunity for them to collaborate to create a nation-wide PBRN in Finland, which should start activities to analyse primary care data quality. In doing so, they would need to overcome the cross-county collaboration challenges. However, PBRN activities may start with simple data collections or QI activities until better quality EHR data are secured.

Last but not least, in the Finnish system most of the HCs are involved in the training of new GPs, and this provides the opportunity to develop a research culture if the new generations of GPs are acquainted with research and critical appraisal during their training. This may bring forth positive attitudes towards research and generate GP research champions who might sustain PBRN activity in the future.

Conclusion

This survey shows that there is motivation across the Finnish HCs to engage in PBRN activity if it is relevant to their interests and provides clear benefits to their operation and foundation for the effectiveness of care and healthcare improvement. Data extraction from multiple centres’ EHRs are likely to develop data repositories for research, but they must overcome data ownership and interoperability issues. HCs with a positive stance towards PBRN activity and clinicians with research experience may sustain the PBRN activity in the country.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by State Research Funding (Valtion tutkimusrahoitus-VTR) funding for TAYS-ERVA [Project number: 9AB109]

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Chan M. Return to Alma-Ata. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):865–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hummers-Pradier EBM, Chevallier P, Eilat-Tsanani S, et al. Research agenda for general practice/family medicine and primary healthcare in Europe. Maastricht: European General Practice Research Network EGPRN; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Weel C, Rosser WW.. Improving healthcare globally: a critical review of the necessity of family medicine research and recommendations to build research capacity. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(Suppl 2):S5–S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Weel C, Schers H, Timmermans A.. Healthcare in the Netherlands. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(Suppl 1):S12–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan F, Butler C, Cupples M, et al. Primary care research networks in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 2007;334(7603):1093–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quality A. Practice-based research networks. 2016. [cited 2022 Jun 23]. Available from: https://pbrn.ahrq.gov

- 7.Dania A, Nagykaldi Z, Haaranen A, et al. A review of 50-years of international literature on the internal environment of building practice-based research networks (PBRNs). J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(4):762–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagykaldi Z. Practice-based research networks at the crossroads of research translation. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(6):725–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeVoe JE, Likumahuwa-Ackman SM, Angier HE, et al. A practice-based research network (PBRN) roadmap for evaluating COVID-19 in community health centers: a report from the OCHIN PBRN. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(5):774–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mold JW, Peterson KA.. Primary care practice-based research networks: working at the interface between research and quality improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(Suppl 1):S12–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dania A, Nease D, Nagykaldi Z, Greiver M, editors. Setting up an international collaborative group for PBRNs – a WONCA initiative. Proceedings from Workshop in NAPCRG PBRN Conference; 2022; Bethesda, Maryland, U.S.A. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaglioti AH, Werner JJ, Rust G, et al. Practice-based research networks (PBRNs) bridging the gaps between communities, funders, and policymakers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(5):630–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleming DM, Crombie DL.. The incidence of common infectious diseases: the weekly returns service of the royal college of general practitioners. Health Trends. 1985;17(1):13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Weel C. The continuous morbidity registration Nijmegen: background and history of a Dutch general practice database. Eur J Gen Pract. 2008;14(Supp 1):5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kristoffersen ES, Bjorvatn B, Halvorsen PA, et al. The Norwegian PraksisNett: a nationwide practice-based research network with a novel IT infrastructure. Scand J Prim Healthcare. 2022;40:217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koskela TH. Building a primary care research network – lessons to learn. Scand J Prim Healthcare. 2017;35(3):229–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.I BJ, Björk Brämberg E, Wåhlin C, et al. Promoting evidence-based practice for improved occupational safety and health at workplaces in Sweden. Report on a practice-based research network approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sumanen M, Reho T, Heikkilä T, et al. Research orientation among general practitioners compared to other specialties. Scand J Prim Healthcare. 2021;39(1):10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decree of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health on the funding of university-level health research 888/2019. Available from: https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2019/20190888

- 20.Pulcini J, Sheetz A, Desisto M.. Establishing a practice-based research network: lessons from the Massachusetts experience. J Sch Health. 2008;78(3):172–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderko L, Lundeen S, Bartz C.. The midwest nursing centers consortium research network: translating research into practice. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2006;7(2):101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soós M, Temple-Smith M, Gunn J, et al. Establishing the victorian primary care practice based research network. Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39(11):857–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carter Y. Research opportunities in primary care. 1st ed. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Regan A, Hayes P, O’Connor R, et al. The university of Limerick education and research network for general practice (ULEARN-GP): practice characteristics and general practitioner perspectives. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeVoe JE, Likumahuwa S, Eiff MP, et al. Lessons learned and challenges ahead: report from the OCHIN safety net west practice-based research network (PBRN). J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(5):560–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birtwhistle R, Keshavjee K, Lambert-Lanning A, et al. Building a pan-Canadian primary care sentinel surveillance network: initial development and moving forward. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(4):412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dillon P, O’Brien KK, McDonnell R, et al. Prevalence of prescribing in pregnancy using the Irish primary care research network: a pilot study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Etz RS, Keith RE, Maternick AM, et al. Supporting practices to adopt registry-based care (SPARC): protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeVoe JE, Gold R, Spofford M, et al. Developing a network of community health centers with a common electronic health record: description of the safety net west practice-based research network (SNW-PBRN). J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(5):597–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwan BM, Sills MR, Graham D, et al. Stakeholder engagement in a patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measure implementation: a report from the SAFTINet practice-based research network (PBRN). J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(1):102–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chmiel C, Bhend H, Senn O, et al. The FIRE project: a milestone for research in primary care in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;140:w13142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamont R, Fishman T, Sanders PF, et al. View from the canoe: co-designing research pacific style. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(2):172–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volmink JA, Furman SN.. The South african sentinel practitioner research network organization, objectives, policies and methods. S Afr Fam Pract. 1991;12:407–471. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunn JM. Should Australia develop primary care research networks? Med J Aust. 2002;177(2):63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rait G, Rogers S, Wallace P.. Primary care research networks: perspectives, research interests and training needs of members Prim Healthcare Res Dev. 2002;3(1):4–10. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciemins EL, Mollis BL, Brant J, et al. Clinician engagement in research as a path towards the learning health system: a regional survey across the northwestern United States. Health Serv Manage Res. 2020;33(1):33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le May A, Mulhall A, Alexander C.. Bridging the research–practice gap: exploring the research cultures of practitioners and managers. J Adv Nurs. 1998;28(2):428–437. 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Askew DA, Clavarino AM, Glasziou PP, et al. General practice research: attitudes and involvement of Queensland general practitioners. Med J Aust. 2002;177(2):74–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braun V, Clarke V.. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 40.TENK FNBoRI . Ethical review. 2021. [cited 2022 Jun 23]. Available from: https://tenk.fi/en/ethical-review

- 41.Wasserman R, Serwint JR, Kuppermann N, et al. The APA and the rise of pediatric generalist network research. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(3):195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Temple-Smith MN, Manski-Nankervis J-A, Lau P, et al. MACH a snapshot of Australian practice based research networks in primary care. A report from the Melbourne Academic Centre. Victoria, Australia: Department of General Practice, The University of Melbourne; 2021. p. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sullivan F, Hinds A, Pitkethly M, et al. Primary care research network progress in Scotland. Eur J Gen Pract. 2014;20(4):337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Truyers C, Goderis G, Dewitte H, et al. The intego database: background, methods and basic results of a flemish general practice-based continuous morbidity registration project. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith HD, Dunleavey J.. Wessex primary care research network: a report on two years progress. Southampt Health J. 1996;3:43–47. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pitkethly M, Sullivan F.. Networking four years of TayRen. Prim Healthcare Res Dev. 2003;4(4):279–283. [Google Scholar]

- 47.American Academy of Family Physicians. Practice-based research networks in the 21st century: the pearls of research. Washington (DC): MFP; 1998. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/nrn/pearlsofresearch.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 48.Comino E. The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust of Australia Churchill Fellowship 2002: primary healthcare research (networks in the United Kingdom). 2002. p. 1 − 38. Available from: http://nswcfa.churchilltrust.com.au/media/fellows/Comino_Elizabeth_2002-1.pdf

- 49.Cooke J, Owen J, Wilson A.. Research and development at the health and social care interface in primary care: a scoping exercise in one national health service region. Health Soc Care Community. 2002;10(6):435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evans D, Exworthy M, Peckham S, et al. Primary care research networks report to the NHS executive South and West Institute for health policy studies. Southampton: University of Southampton; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tulinius C, Nielsen AB, Hansen LJ, et al. Increasing the general level of academic capacity in general practice: introducing mandatory research training for general practitioner trainees through a participatory research process. Qual Prim Care. 2012;20(1):57–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams RL, McPherson L, Kong A, et al. Internet-based training in a practice-based research network consortium: a report from the primary care multiethnic network (PRIME net). J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(4):446–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zallman L, Tendulkar S, Bhuyia N, et al. Provider’s perspectives on building research and quality improvement capacity in primary care: a strategy to improve workforce satisfaction. Clin Transl Sci. 2013;6(5):404–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peterson KA, Lipman PD, Lange CJ, et al. Supporting better science in primary care: a description of practice-based research networks (PBRNs) in 2011. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(5):565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weiss BD, Brega AG, LeBlanc WG, et al. Improving the effectiveness of medication review: guidance from the health literacy universal precautions toolkit. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(1):18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fiks AG, Grundmeier RW, Steffes J, et al. Comparative effectiveness research through collaborative electronic reporting Consortium. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):e215-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richards DA, Bower P, Chew-Graham C, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in UK primary care (CADET): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(14):1–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tu KS, Kidd MR, Grunfeld E, et al. The university of Toronto family medicine report: caring for our diverse populations. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto, Department of Family and Community Medicine; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Authority F. Findata – Finnish social and health data permit authority. 2022. [cited 2022 May 15]. Available from: https://findata.fi/en/

- 60.Wouters RH, Graaf R, Voest EE, et al. Learning healthcare systems: highly needed but challenging. Learn Health Syst. 2020;4(3):e10211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.College of Family Physicians of Canada . Position statement: supporting access to data in electronic medical records for quality improvement. Mississauga (ON): College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2017. Available from: https://www.cfpc.ca/en/policy-innovation/health-policy-goverment-relations/cfpc-policy-papers-position-statements/position-statement-supporting-access-to-data-in-el [Google Scholar]