Abstract

Objective:

To describe strategies used to recruit and retain young adults in nutrition, physical activity and/or obesity intervention studies, and quantify the success and efficiency of these strategies.

Design:

A systematic review was conducted. The search included six electronic databases to identify randomised controlled trials (RCT) published up to 6 December 2019 that evaluated nutrition, physical activity and/or obesity interventions in young adults (17–35 years). Recruitment was considered successful if the pre-determined sample size goal was met. Retention was considered acceptable if ≥80 % retained for ≤6-month follow-up or ≥70 % for >6-month follow-up.

Results:

From 21 582 manuscripts identified, 107 RCT were included. Universities were the most common recruitment setting used in eighty-four studies (79 %). Less than half (46 %) of the studies provided sufficient information to evaluate whether individual recruitment strategies met sample size goals, with 77 % successfully achieving recruitment targets. Reporting for retention was slightly better with 69 % of studies providing sufficient information to determine whether individual retention strategies achieved adequate retention rates. Of these, 65 % had adequate retention.

Conclusions:

This review highlights poor reporting of recruitment and retention information across trials. Findings may not be applicable outside a university setting. Guidance on how to improve reporting practices to optimise recruitment and retention strategies within young adults could assist researchers in improving outcomes.

Keywords: Young adults, Nutrition, Physical activity, Obesity, Systematic review, Recruitment, Retention

Young adults (aged 17–35 years) commonly develop poor lifestyle behaviours that track into later adulthood and increase the risk of chronic disease across the life course(1,2). Rates of overweight and obesity have increased from 38 % to 46 % among those aged 18–24 years in the time periods from 2011–2012 to 2017–2018 in Australia(3,4), while this has increased from 42 % to 60 % in 20–34-year-olds from 1994 to 2015 in the USA(5). The increase in overweight and obesity rates coincides with worsening dietary patterns and physical inactivity during this life stage. A systematic evaluation of dietary patterns in adults from 187 countries found that the unhealthiest dietary scores were in 20–29-year-olds compared with all other age ranges(6). Furthermore, a meta-analysis of physical activity change from adolescence to young adulthood demonstrated a 13–17 % (or 5·2–7·4 min/d) decline in moderate–vigorous physical activity from age 13 to 30 years(7). Therefore, this represents a critical stage to establish healthy lifestyle behaviours.

Several reviews have provided insights into effective intervention approaches for improving health behaviour among young adults(8–14); however, a more focused enquiry on recruitment and retention strategies is required. Recruitment refers to the process of selection of participants, from becoming aware of the health programme to enrolment of participants(15), while retention refers to keeping participants enrolled for the duration of the health programme(15). Effective recruitment and retention of young adults in health behaviour programmes are critical, yet present ongoing challenges. Both recruitment and retention may be impacted by transient living arrangements which are common during this life stage, while competing time demands may be prioritised over participation (e.g. study, work, socialising, relationships, family obligations and/or parenthood)(16,17). Furthermore, the perceptions around the imminence of health problems for someone in their life stage may affect overall recruitment of young adults to a health programme(17,18).

Issues with recruitment or retention can have serious consequences for any research study. Failure to recruit the desired sample size can lead to underpowered studies, leading to a type II error (false-negative findings), while under recruiting can impact representativeness of population samples and therefore the external validity of results(19). Furthermore, prolonged recruitment can affect overall research expenditure(20) and adversely affect the commitment of those already enrolled in the study(21). Failure to retain sufficient numbers may implicate the study power by affecting the composition between treatment and control groups(21). In addition, differential dropout may occur, whereby particular sub-groups of individuals may be more likely to dropout than others(21). These issues pose a threat to a study’s internal and external validity(19). Consequently, successful and timely recruitment and retention of participants are vital to the success of the overall health programme.

There is a lack of evidence to guide successful recruitment and retention strategies for young adults in health behaviour change interventions(22,23). The few studies that have explored this have documented serious challenges. For instance, a systematic review of weight gain prevention interventions in young adults identified recruitment rates to be low (between 7·5 % and 48 % of their intended targeted population)(24), while another review of health behaviour interventions in young adult men(25) identified only 30 % of studies had achieved appropriate retention in line with the CONSORT requirements (≥80 % retained for ≤6-month follow-up or ≥70 % for >6-month follow-up) to prevent bias. Neither review looked at recruitment or retention rates by the various strategies used, while both confirmed that insufficient reporting limited the ability to determine which strategies were most successful.

Furthermore, these reviews searched for studies up until 2015(24) and 2014(25). However, health behaviour interventions among young adults have increased significantly in recent years, with the number of published interventions doubling between 2015 and 2019 for studies targeting adiposity (n 26)(8) and between 2014 and 2018 for studies aiming to improve dietary intake among young adults (n 29)(9). This presents an opportunity to conduct a more focused enquiry into recruitment and retention strategies among this group.

To inform strategies to reach and retain young adults for effective implementation of interventions, evidence-based guidance is needed. Therefore, the current review aims to describe the strategies used to recruit and retain young adults in interventions targeting nutrition, physical activity or overweight/obesity in young adults (aged 17–35 years), and the success and efficiency of these strategies. The following research questions are answered in this review:

What are the most common recruitment strategies for young adults?

What are the most successful recruitment strategies for young adults?

Is recruitment success affected by number of strategies used?

What are the most efficient recruitment strategies for young adults?

What are the costs per participant recruited?

What are the most common retention strategies for young adults?

Do studies adequately retain young adults?

What are the most successful retention strategies for young adults?

What are the costs per participant retained?

What reporting is needed to assess the success of recruitment strategies?

What reporting is needed to assess the success of retention strategies?

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of included studies in a systematic review exploring the effectiveness of nutrition, physical activity or overweight/obesity interventions in young adults. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42017075795), and the methods are consistent with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. Results for the effectiveness of interventions have been published previously(8,9,26). The current paper presents results for recruitment and retention data.

The eligibility criteria, literature search, study selection and risk of bias of individual studies in the systematic review have been previously described in detail(8,9). Table 1 outlines the full eligibility criteria. In brief, included studies were randomised controlled trials (RCT) of behavioural interventions with the primary objective of improving nutrition or physical activity, or treating or preventing obesity. Participants were required to be healthy young adults (aged 17–35 years), and any comparator or control was considered for inclusion. The definition of young adults used in studies varies based on human development and sociological perspectives. For the current review, a broad age range was included to ensure a range of studies in healthy young adults across the age range of 17–35 years. Both the National Institute of Health(27) and the European commission of Men’s health(28) have used 18–35 years to define young adults. The inclusion criteria for participants were shaped around this definition, and the rationale for including those aged 17 years was due to some countries enrolling those aged 17 years in tertiary education(29,30). Articles were located by searching six databases (Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Science Citation Index, Cinahl and Cochrane Library) for articles published in English from date of inception to 6 December 2019 (see online supplementary material, Supplementary Table 1), as well as searching reference lists of retrieved papers and key systematic reviews. In addition, citation searches of the final included papers were conducted in Scopus. Papers linked to relevant RCT, including published study protocol, recruitment or process evaluation papers, or those publishing outcomes at differing follow-up time points, were also considered. Two independent reviewers screened the title, abstract and keywords of articles, followed by assessment of full-text articles that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria and then selected studies for inclusion. A third reviewer was consulted if disagreement existed between the two reviewers. Reasons for exclusion were recorded for ineligible papers.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes and study design (PICOS)

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Healthy young adults across the age range of 17–35 years. All participants in the trial were required to be within this age range. | Participants with diagnosed obesity-related medical conditions such as type 2 diabetes or from specific population sub-groups, including those with severe mental illness, eating disorders, elite athletes or pregnancy. |

| Interventions | Behavioural interventions focusing on diet, physical activity and/or treating or preventing obesity. All modalities (e.g. face-to-face, print, eHealth and mHealth) were considered for inclusion. | • Interventions involving bariatric surgery or anti-obesity medications. • Studies which primarily investigated the acute impact of weight loss on other clinical biomarkers (e.g. insulin). |

| Comparators | Comparison groups with no intervention (e.g. waitlist control) and/or active treatments were considered for inclusion. | Single-arm studies with no comparison group. |

| Outcomes | Any measures (both objective and self-reported) to assess outcome effectiveness of interventions on either nutrition, physical activity and/or obesity as the primary outcome at baseline and a minimum of one post-intervention time point. | Did not measure nutrition, physical activity and/or obesity as the primary outcome. |

| Study designs | Randomised controlled trials (RCT) including pilot and feasibility RCT. Papers linked to relevant RCT, including published study protocol, recruitment or process evaluation papers, or those publishing outcomes at differing follow-up time points, were also considered. | Study design was not an RCT or associated ‘linked paper’ of RCT. |

Data extraction

Data relating to recruitment strategies (i.e. setting, method and duration), recruitment rates (i.e. number: invited, expressed interest/screened for eligibility, eligible, enrolled/randomised and commenced intervention), study characteristics (i.e. year of publication, country, intervention details and sample characteristics), retention strategies (i.e. any strategy used to keep participants enrolled for the study duration)(15), retention rates (i.e. number completing post-intervention and longest follow-up assessment) and cost of recruitment and retention strategies (total cost, cost per participant randomised and/or retained and breakdown of costs by each strategy) were extracted by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer.

Synthesis of results and analytic strategy

Results are presented narratively to address all research questions. To evaluate the success of recruitment and retention strategies, the following metrics were used:

Recruitment rate (%) = total number of individuals randomised/total number who showed interest in the study

Participation rate (%) = total number of eligible participants randomised/total number eligible at baseline

Retention rate (%) = total number of participants who completed follow-up/total number who entered the study

Recruitment was considered successful if the pre-determined goal sample size was met(31). Recruitment efficiency was calculated as the number of participants randomised/recruitment duration in days. Retention was considered adequate if retention was ≥80 % for ≤6-month follow-up or ≥70 % for >6-month follow-up, as defined in several previous systematic reviews(25,32–34). Retention efficiency could not be calculated due to insufficient reporting of duration for follow-up data collection. The success of individual recruitment and retention strategies was calculated the same way, that is the number of studies which used a given strategy and had successful recruitment or retention divided by the number of studies which used that strategy. Efficiency of individual recruitment strategies was calculated as the mean and standard deviation across studies which used each strategy. Differences in recruitment and retention characteristics by intervention focus were assessed using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. An overall test of significance was carried out using a contingency table between numbers of recruitment strategies using Monte–Carlo exact χ2 test (SPSS version 25). Costs relating to recruitment and retention strategies were reported in USD. To standardise, studies reporting cost information in a currency other than USD (n 10 studies) were converted to USD using xe.com (https://www.xe.com/currencytables/) from the year and month that the study was conducted. Cost per participant randomised and cost per participant retained at post-intervention and at longest follow-up were then calculated. Finally, any gaps in reporting of recruitment and retention information were collated, and a summary was provided for key information required when reporting recruitment and retention in trials.

Results

Description of included studies

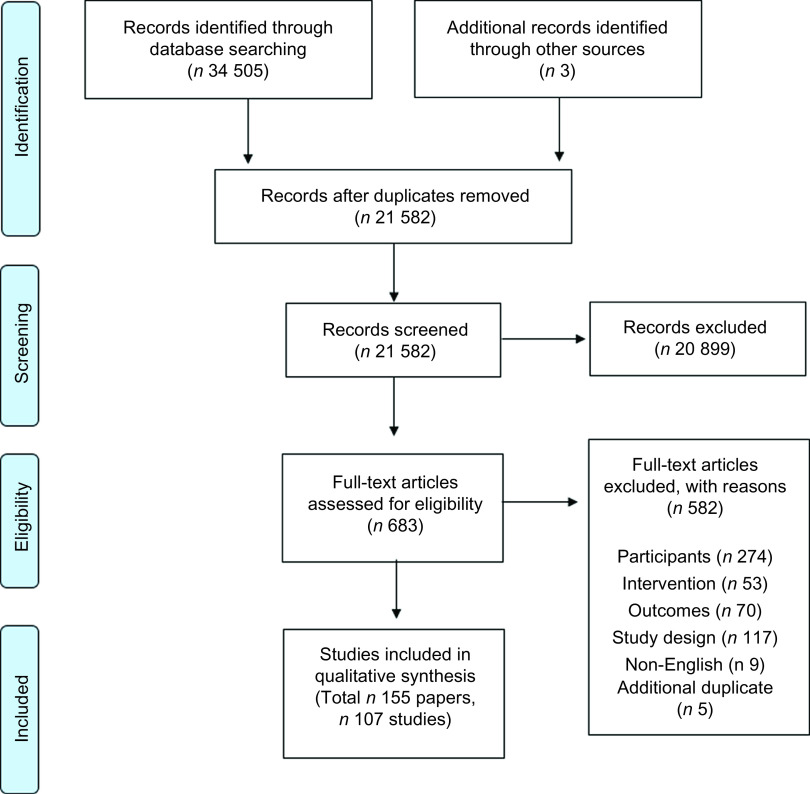

A total of 21 582 manuscripts were identified and screened, and of these, 107 individual RCT were included(35–140) (Fig. 1). A summary of study characteristics is included in Table 2, with detailed characteristics presented in Supplemental Table 2. Fifty percentage of studies were published since 2015 (n 53), and around half were conducted in the USA (n 58, 54 %) and recruited participants from a University/College setting (n 84 studies, 79 %). There was a mean of 276 participants per study, and participants were mainly aged 17–25 years (n 60 studies, 56 %) and were of white/Caucasian ethnicity (n 62 studies, 58 %). Intervention focus was most commonly physical activity (n 31, 29 %) followed by nutrition (n 28, 26 %). The most common mode of intervention delivery was eHealth (e.g. email, mobile phone applications, websites and social media) (n 61 intervention arms, 35 %). The mean duration of interventions was 15·5 weeks, ranging from single session interventions to 3 years duration.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of included studies

Table 2.

Summary of study characteristics in 107 studies of nutrition, physical activity and obesity interventions in young adults

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Publication year | ||

| Before 2005 | 6 | 6 |

| 2005–2009 | 11 | 10 |

| 2010–2014 | 37 | 35 |

| 2015–6 December 2019 | 53 | 50 |

| Country | ||

| USA | 58 | 54 |

| Australia | 11 | 10 |

| Canada | 8 | 7 |

| UK | 5 | 5 |

| Thailand | 3 | 3 |

| Finland | 3 | 3 |

| New Zealand | 2 | 2 |

| Italy | 2 | 2 |

| Other | 15 | 14 |

| Number of participants | ||

| Mean | 276·3 | |

| Median | 124 | |

| Range | 20–3336 | |

| Recruitment setting | ||

| University/College | 84 | 79 |

| Community | 10 | 9 |

| Military | 4 | 4 |

| University/College + Community | 3 | 3 |

| Clinical | 2 | 2 |

| Workplace | 1 | 1 |

| University/College + Clinical | 1 | 1 |

| University/College + Community + Workplace | 1 | 1 |

| Not reported | 1 | 1 |

| Age | ||

| Mean years (sd) | 21·1 | 3 |

| 17–≤25 years | 60 | 56 |

| 17–≤30 years | 23 | 21 |

| 17–≤35 years | 24 | 22 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Predominantly white | 62 | 58 |

| Predominantly non-white | 7 | 7 |

| Not reported | 38 | 36 |

| Intervention focus | ||

| Physical activity | 31 | 29 |

| Nutrition | 28 | 26 |

| Weight gain prevention | 18 | 17 |

| Weight loss | 16 | 15 |

| Nutrition and Physical Activity | 14 | 13 |

| Mode of intervention delivery* | ||

| Face-to-face only | 38 | 22 |

| eHealth only | 61 | 35 |

| Print materials only | 4 | 2 |

| Wearable device only | 2 | 1 |

| Face-to-face + print materials | 22 | 13 |

| Face-to-face + eHealth | 21 | 12 |

| Face-to-face + eHealth + wearable device | 2 | 1 |

| Face-to-face + eHealth + print materials | 8 | 5 |

| Face-to-face + wearable device | 2 | 1 |

| eHealth + wearable device | 7 | 4 |

| eHealth + print materials | 4 | 2 |

| Wearable device + print materials | 2 | 1 |

| Intervention duration (weeks) | ||

| Mean | 15·5 | |

| Median | 8·0 | |

| Range | < 1–156 |

Reported by active intervention arms (n 173).

Recruitment

All recruitment details are summarised by intervention focus in Table 3. Responses to recruitment research questions are provided below.

Table 3.

Summary of recruitment details of 107 studies of nutrition, physical activity and obesity interventions in young adults, by intervention focus

| Total (n 107) | Physical activity (n 31) | Nutrition (n 28) | Weight gain prevention (n 18) | Weight loss (n 16) | Nutrition and physical activity (n 14) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Recruitment setting | University/College | 84 | 78·5 | 27 | 87·1 | 23 | 82·1 | 13 | 72·2 | 11 | 68·8 | 10 | 71·4 |

| Community | 10 | 9·3 | 1 | 3·2 | 3 | 10·7 | 3 | 16·7 | 2 | 12·5 | 1 | 7·1 | |

| University and other | 5 | 4·7 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 2 | 11·1 | 2 | 12·5 | 1 | 7·1 | |

| Military | 4 | 3·7 | 2 | 6·5 | 2 | 7·1 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | |

| Health service | 2 | 1·9 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 1 | 6·3 | 1 | 7·1 | |

| Workplace | 1 | 0·9 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 1 | 7·1 | |

| Not reported | 1 | 0·9 | 1 | 3·2 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | |

| Recruitment strategies | Flyers | 40 | 37·4 | 8 | 25·8 | 5 | 17·9 | 14 | 77·8 | 8 | 50·0 | 5 | 35·7 |

| Existing cohort/database | 29 | 27·1 | 9 | 29·0 | 9 | 32·1 | 4 | 22·2 | 3 | 18·8 | 4 | 28·6 | |

| 28 | 26·2 | 6 | 19·4 | 4 | 14·3 | 8 | 44·4 | 7 | 43·8 | 3 | 21·4 | ||

| Face-to-face | 26 | 24·3 | 8 | 25·8 | 4 | 14·3 | 5 | 27·8 | 3 | 18·8 | 6 | 42·9 | |

| University classroom | 23 | 21·5 | 7 | 22·6 | 7 | 25·0 | 6 | 33·3 | 1 | 6·3 | 2 | 14·3 | |

| Poster | 19 | 17·8 | 4 | 12·9 | 5 | 17·9 | 3 | 16·7 | 5 | 31·3 | 2 | 14·3 | |

| Newspaper/newsletter | 18 | 16·8 | 4 | 12·9 | 3 | 10·7 | 5 | 27·8 | 6 | 37·5 | 0 | 0·0 | |

| Social media | 15 | 14·0 | 3 | 9·7 | 3 | 10·7 | 3 | 16·7 | 5 | 31·3 | 1 | 7·1 | |

| Online ads | 13 | 12·1 | 1 | 3·2 | 3 | 10·7 | 4 | 22·2 | 4 | 25·0 | 1 | 7·1 | |

| Word of mouth | 13 | 12·1 | 3 | 9·7 | 3 | 10·7 | 3 | 16·7 | 4 | 25·0 | 0 | 0·0 | |

| Media release | 10 | 9·3 | 1 | 3·2 | 0 | 0·0 | 2 | 11·1 | 6 | 37·5 | 1 | 7·1 | |

| Letters | 10 | 9·3 | 1 | 3·2 | 1 | 3·6 | 6 | 33·3 | 2 | 12·5 | 0 | 0·0 | |

| University website | 6 | 5·6 | 2 | 6·5 | 1 | 3·6 | 0 | 0·0 | 3 | 18·8 | 0 | 0·0 | |

| Digital bulletin boards | 2 | 1·9 | 0 | 0·0 | 2 | 7·1 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | |

| Phone | 1 | 0·9 | 1 | 3·2 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | |

| Unclear/not reported | 7 | 6·5 | 3 | 2·8 | 2 | 1·9 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 2 | 1·9 | |

| Duration of recruitment | ≤1 month | 12 | 11·2 | 6 | 19·4 | 2 | 7·1 | 1 | 5·6 | 2 | 12·5 | 1 | 7·1 |

| >1 to <4 months | 19 | 17·8 | 3 | 9·7 | 5 | 17·9 | 3 | 16·7 | 3 | 18·8 | 5 | 35·7 | |

| 4 to 6 months | 7 | 6·5 | 3 | 9·7 | 2 | 7·1 | 1 | 5·6 | 0 | 0·0 | 1 | 7·1 | |

| >6 months to <1 year | 3 | 2·8 | 2 | 6·5 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 1 | 6·3 | 0 | 0·0 | |

| ≥1 year | 7 | 6·5 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 4 | 22·2 | 2 | 12·5 | 1 | 7·1 | |

| Mean | 172 | 110 | 82 | 375 | 183 | 140 | |||||||

| Median | 90 | 75 | 90 | 150 | 60 | 87 | |||||||

| Range (d) | 7–1095 | 7–365 | 16–180 | 30–1095 | 14–600 | 30–480 | |||||||

| Not reported | 59 | 55·1 | 17 | 54·8 | 19 | 67·9 | 9 | 50·0 | 8 | 50·0 | 6 | 42·9 | |

| Recruitment efficiency (participants/d)* | Mean | 5·0 | 6·9 | 3·9 | 4·7 | 5·1 | 3·0 | ||||||

| Median | 1·9 | 1·2 | 2·7 | 1·5 | 1·0 | 2·1 | |||||||

| Range | 0·04–33·6 | 0·1–31·2 | 0·9–11·2 | 0·04–29·3 | 0·2–33·6 | 0·2–7·0 | |||||||

| Number invited to participate† | Mean | 2127 | 748 | 2815 | – | || | 3181 | ||||||

| Median | 880 | 880 | 732 | – | || | 1500 | |||||||

| Range | 163–15 000 | 163–1265 | 233–15 000 | – | || | 244–10 370 | |||||||

| Number interested/screened‡ | Mean | 782 | 348 | 441 | 1999 | 858 | 506 | ||||||

| Median | 239 | 217 | 247 | 437 | 318 | 220 | |||||||

| Range | 61–8903 | 61–1526 | 75–2240 | 105–8903 | 79–4164 | 62–3059 | |||||||

| Number eligible§ | Mean | 435 | 220 | 315 | 1044 | 290 | 613 | ||||||

| Median | 180 | 158 | 208 | 306 | 97 | 164 | |||||||

| Range | 21–3983 | 21–1017 | 45–2024 | 66–3983 | 53–1743 | 40–3336 | |||||||

| Number enrolled/randomised | Mean | 276 | 147 | 281 | 369 | 135 | 595 | ||||||

| Median | 124 | 95 | 168 | 163 | 69 | 164 | |||||||

| Range | 20–3336 | 20–935 | 32–2024 | 40–1689 | 40–470 | 39–3336 | |||||||

| % invited randomised† | Mean | 38·1 | 38·0 | 39·7 | – | || | 48·4 | ||||||

| Median | 31·7 | 39·2 | 25·5 | – | || | 72·1 | |||||||

| Range | 1·4–92·8 | 2·3–79·1 | 1·6–92·8 | – | || | 1·4–87·0 | |||||||

| % interested randomised‡ | Mean | 54·8 | 55·6 | 70·2 | 47·6 | 29·3 | 68·8 | ||||||

| Median | 57·4 | 59·9 | 75·3 | 43·6 | 22·1 | 71·8 | |||||||

| Range | 5·9–100·0 | 6·4–100·0 | 26·3–100·0 | 10·5–98·3 | 5·9–71·3 | 21·4–100·0 | |||||||

| Participation rate: % eligible randomised§ | Mean | 82·6 | 82·7 | 90·0 | 72·4 | 71·7 | 91·3 | ||||||

| Median | 99·2 | 100·0 | 100·0 | 75·7 | 79·6 | 100·0 | |||||||

| Range | 4·0–100·0 | 4·0–100·0 | 45·9–100·0 | 15·3–100·0 | 20·9–100·0 | 73·3–100·0 | |||||||

Results in bold were statistically significantly different between groups of studies with different intervention focus (P < 0·05).

n 48 studies (14 physical activity, 9 nutrition, 9 weight gain prevention, 8 weight loss, 8 nutrition and physical activity).

n 21 studies (7 physical activity, 8 nutrition, 1 weight loss, 5 nutrition and physical activity).

n 78 studies (20 physical activity, 18 nutrition, 14 weight gain prevention, 14 weight loss, 12 nutrition and physical activity).

n 96 studies (26 physical activity, 26 nutrition, 14 weight gain prevention, 16 weight loss, 14 nutrition and physical activity).

Results available for only one weight loss study and are not reported.

Research question #1: What are the most common recruitment strategies for young adults?

The most common recruitment strategies were flyers (n 40, 37 %) and using an existing cohort or participant database (n 29, 27 %). Recruitment strategies are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of recruitment strategies of 107 studies of nutrition, physical activity and obesity interventions in young adults

| Recruitment strategy | Total (n 107)* | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Flyers | 40 | 37·4 |

| Existing cohort/database | 29 | 27·1 |

| 28 | 26·2 | |

| Face-to-face | 26 | 24·3 |

| University classroom | 23 | 21·5 |

| Poster | 19 | 17·8 |

| Newspaper/newsletter | 18 | 16·8 |

| Social media | 15 | 14·0 |

| Online ads | 13 | 12·1 |

| Word of mouth | 13 | 12·1 |

| Media release | 10 | 9·3 |

| Letters | 10 | 9·3 |

| University website | 6 | 5·6 |

| Digital bulletin boards | 2 | 1·9 |

| Phone | 1 | 0·9 |

| Unclear/not reported | 7 | 6·5 |

| Number of strategies used (mean ± sd) | 2·5 ± 1·9 | |

n 1 study did not report the recruitment setting; therefore, the total includes all 107 studies, but the breakdown by recruitment setting includes 106 studies.

Research question #2: What are the most successful recruitment strategies for young adults?

The mean participation rate (% eligible who were randomised) could be calculated for ninety-six studies. The overall mean was 83 %. The mean recruitment rate (% interested who were randomised) was calculated for seventy-eight studies, with an overall mean of 55 %. The median recruitment rate (participants recruited per day) in the forty-eight studies which reported it was 1·9 participants per day.

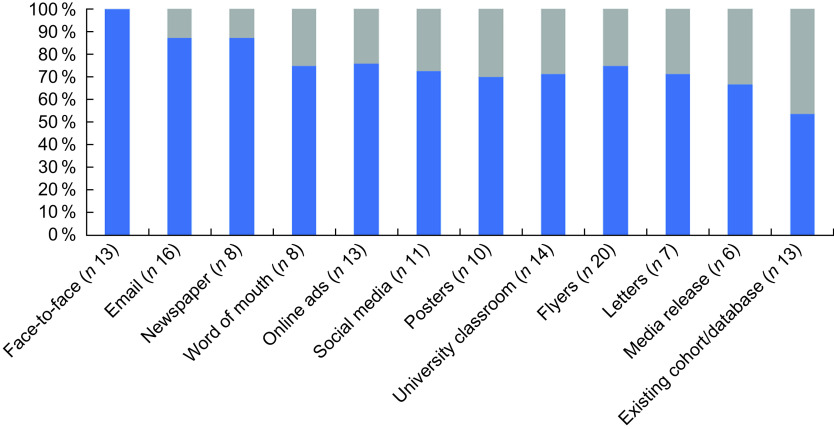

Forty-six studies reported a power estimation (43 %), and seven pilot studies reported a goal sample size (7 %). Of these, forty-one studies (77 %) reported that participant recruitment reached the pre-determined sample size. Success of individual recruitment strategies was determined for forty-nine studies. To provide a meaningful representation of success, only recruitment strategies that were reported in at least three studies were considered, this included thirteen strategies. The top four strategies with the highest success rates were face-to-face (e.g. university/college fairs at start of semester open days) (n 13, 100 %), email (n 14, 88 %), newspaper advertisements (n 7, 88 %) and online advertisements (e.g. Google ads) (n 7, 88 %) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Success* of recruitment strategies used across forty-nine studies of nutrition, physical activity and/or obesity interventions in young adults. *Recruitment was considered successful if the pre-determined goal sample size was met

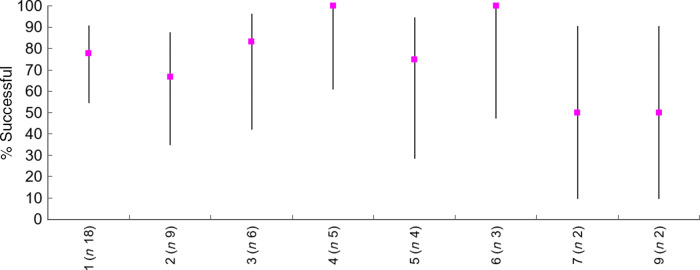

Research question #3: Is recruitment success affected by number of strategies used?

The median number of recruitment strategies used across the forty-nine studies was 2 (range 1–9 strategies per study). Figure 3 presents the percentage ratio of recruitment success by number of recruitment strategies, highlighting that no relationship exists based on whether fewer or more strategies are utilised. The overall test of significance using a contingency table indicates that there was no significant relationship (Monte–Carlo exact χ2 test, χ2(7) = 4·8, P = 0·73).

Fig. 3.

Recruitment success* (%) by number of recruitment strategies used. *Recruitment was considered successful if the pre-determined goal sample size was met

Research question #4: What are the most efficient recruitment strategies for young adults?

Efficiency of individual recruitment strategies was determined for forty-eight studies. As with recruitment success, to provide a meaningful representation of efficiency, only recruitment strategies that were reported in at least three studies were considered (n 13). The mean and standard deviation of recruitment efficiency was calculated for each recruitment strategy. The top four strategies which had the highest efficiency were advertising through letters (mean ± sd of 8·7 ± 14·1 participants recruited per day), using existing cohorts or participant databases (7·3 ± 10·8 participants recruited per day), face-to-face (6·4 ± 10·3 participants recruited per day) and advertising within university classrooms (6·1 ± 10·8 participants recruited per day) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Efficiency of recruitment strategies used across forty-eight studies of nutrition, physical activity and/or obesity interventions in young adults

| Recruitment strategy | Recruitment efficiency (number of participants recruited per day)* | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | sd | |

| Letters (n 8) | 8·7 | 14·1 |

| Existing cohort/database (n 14) | 7·3 | 10·8 |

| Face-to-face (n 14) | 6·4 | 10·3 |

| University classroom (n 13) | 6·1 | 10·8 |

| Media release (n 8) | 4·9 | 11·6 |

| Email (n 13) | 3·6 | 7·8 |

| Flyers (n 19) | 3·2 | 6·8 |

| Word of mouth (n 8) | 2·6 | 3·7 |

| University website (n 3) | 2·1 | 1·5 |

| Posters (n 11) | 1·9 | 1·9 |

| Social media (n 9) | 1·3 | 1·0 |

| Online ads (n 9) | 0·9 | 0·6 |

| Newspaper (n 8) | 0·7 | 0·3 |

Recruitment efficiency = the number of participants randomised/recruitment duration in days. The (n) refers to the number of studies which used each strategy.

Research question #5: What are the costs per participant recruited?

Total cost of recruitment was documented in three studies (Project Grad, TXT2BFIT and SNAP study)(35,46,139,141,142). Costs in ascendency were: Project Grad which spent US$20 729 for recruiting participants from a University setting and implemented two recruitment strategies (mailed literature and telephone calls to students)(46). Next, TXT2BFIT spent US$32 861·98 for recruiting participants from a community and University setting and implemented fourteen recruitment strategies (GP letter, Facebook advertisement, Google advertisement, Gumtree advertisement, Social media page, University e-newsletter, University web home page, University research volunteer page, poster, brochures, commuter newspaper advertisement, local newspaper advertisement, students’ magazine and word of mouth)(35,141). Last, SNAP study spent US$139 543 to recruit participants from a community setting and implemented nine strategies (television, print media, radio, mass mailing, website recruitment, email, flyers and community events, study referral and word of mouth)(139,142). Two of these studies provided a breakdown of costs by strategy. Specifically, the SNAP study reported mass mailings (US$76 466·34) and television ($24 074·00) to be most expensive, while the cheapest paid strategies were flyers and community events (costed together at US$2713·27) and website recruitment (US$5222·23). There were no costs associated with some strategies including word of mouth and study referral. The most expensive strategies in the TXT2BFIT programme were brochures (US$12 922·20) and letters sent from general practitioners (US$9316·20), while the cheapest paid strategies were Gumtree advertisement (US$34·08) and University student magazines (US$701·52). There were several free strategies provided by University resources (i.e. University e-newsletter, University volunteer page, University web home page).

Cost per participant randomised was established in three studies. In the PROJECT GRAD study, this was US$45 for the passive recruitment method and $79 for the active recruitment method(46). The TXT2BFIT and SNAP studies were more expensive with a total cost per participant randomised of US$131·77 and US$232·96, respectively(35,139,141,142).

Retention

Retention details are summarised by intervention focus in Table 6. Responses to retention research questions are provided below.

Table 6.

Summary of retention details of 107 studies of nutrition, physical activity and obesity interventions in young adults, by intervention focus

| Total (n 107) | Physical activity (n 31) | Nutrition (n 28) | Weight gain prevention (n 18) | Weight loss (n 16) | Nutrition and physical activity (n 14) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Strategies to retain | Payment/gift voucher | 44 | 41·1 | 9 | 29·0 | 10 | 35·7 | 7 | 38·9 | 11 | 68·8 | 7 | 50·0 |

| Reminders/increased contact | 22 | 20·6 | 5 | 16·1 | 3 | 10·7 | 4 | 22·2 | 6 | 37·5 | 4 | 28·6 | |

| Course credit | 18 | 16·8 | 5 | 16·1 | 6 | 21·4 | 4 | 22·2 | 1 | 6·3 | 2 | 14·3 | |

| Prize/Prize draw | 12 | 11·2 | 3 | 9·7 | 5 | 17·9 | 2 | 11·1 | 0 | 0·0 | 2 | 14·3 | |

| Feedback | 5 | 4·7 | 2 | 6·5 | 0 | 0·0 | 3 | 16·7 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | |

| Flexible scheduling | 4 | 3·7 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 1 | 5·6 | 3 | 18·8 | 0 | 0·0 | |

| Completion certificate | 1 | 0·9 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 0 | 0·0 | 1 | 7·1 | |

| No incentive /not reported | 31 | 29·0 | 10 | 32·3 | 11 | 39·3 | 5 | 27·8 | 3 | 18·8 | 2 | 14·3 | |

| Retention rate: % randomised retained | At post-intervention* | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 83·3 | 84·2 | 80·3 | 80·8 | 85·4 | 87·6 | |||||||

| Median | 85·5 | 90·0 | 87·5 | 80·5 | 85·5 | 94·0 | |||||||

| Range | 22·0–100·0 | 23·0–100·0 | 65·4–98·0 | 22·0–100·0 | |||||||||

| At longest follow-up† | |||||||||||||

| Mean | 75·9 | 83·8 | 85·4 | 59·9 | 62·9 | 72·0 | |||||||

| Median | 84·0 | 86·0 | 89·5 | 64·0 | 67·0 | 73·5 | |||||||

| Range | 8·0–100·0 | 21·6–100·0 | 8·0–94·0 | 53·9–100·0 | |||||||||

n 76 studies (21 physical activity, 16 nutrition, 16 weight gain prevention, 14 weight loss, 9 Nutrition and physical activity); 25 studies did not collect data at post-intervention, and 6 studies collected data but did not report retention.

n 49 studies (11 physical activity, 16 nutrition, 9 weight gain prevention, 5 weight loss, 8 nutrition and physical activity); 57 studies did not collect data beyond the end of the intervention.

Research question #6: What are the most common retention strategies for young adults?

Of the included studies, seventy-six studies (71 %) reported strategies to retain participants. Almost half of these studies (n 44, 41 %) used financial incentives such as gift cards, twenty-two studies (21 %) used reminders and increased contact with participants and eighteen studies (17 %) gave participants credit for university/college courses in return for participation (Table 6).

Research question #7: Do studies adequately retain young adults?

In the seventy-six studies which reported retention rates at post-intervention (range 1 week to 3 years, median: 12 weeks), there was a mean ± sd retention rate of 83 ± 14 %. Forty-nine studies measured retention rates at the longest follow-up and found that a mean ± sd of 76 ± 23 % of participants was retained. Longest follow-up ranged from 1 week to 2 years from baseline (mean 25·9 weeks, median 17·5 weeks) and ranged from 1 week to 1 year and 11 months from the end of the intervention (mean 17·3 weeks, median 11·5 weeks). Overall, seventy studies (65 %) had adequate retention (≥80 % retained for ≤6-month follow-up or ≥70 % for >6-month follow-up).

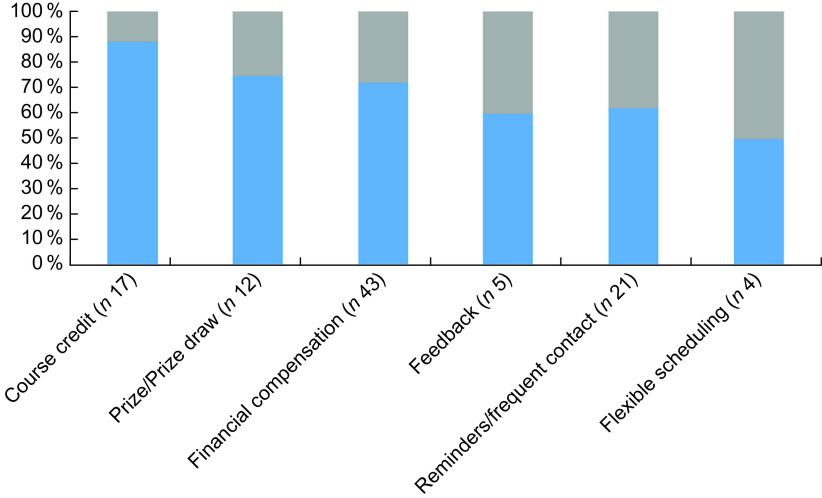

Research question #8: What are the most successful retention strategies for young adults?

Success of individual retention strategies was determined for seventy-four studies (69 %). To provide a meaningful representation of each strategy’s ability to meet the criteria for acceptable retention, only retention strategies that were reported in at least three studies were considered (n 6). The most successful retention strategies were providing participants with course credit for university/college courses (n 15, 88 %), prize/prize draw (n 9, 75 %) and financial incentives (n 31, 72 %). (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Adequacy* of retention strategies used across seventy-four studies of nutrition, physical activity and/or obesity interventions in young adults. *Retention was considered adequate if retention was ≥80% for ≤6-month follow-up or ≥70% for >6-month follow-up

Research question #9: What are the costs per participant retained?

Total cost of retention was documented in forty studies(35,38,42–46,49,55,58–63,69–71,74,76,77,86,88–91,101–103,109,114,115,119,120,126,134,136,137,139,143) ranging from US$50 (n 1 strategy was used) to US$202 700 (n 1 strategy used), with a median cost of US$1935. The costs per participant retained at post-intervention were established in thirty-eight studies, ranging from US$0·50(86) to US$553·83(90), with a median cost of US$22·55. Costs per participant retained at longest follow-up were established in eighteen studies, ranging from US$1·15(143) to US$97·20(63), with a median cost of US$20.

Discussion

The current study provides a comprehensive review of the recruitment and retention data of 107 RCT targeting nutrition, physical activity or overweight/obesity in young adults. Notably, the review highlights the poor reporting of details related to recruitment information across the trials (i.e. only 46 % of studies provided sufficient information to determine the ability of individual recruitment strategies to meet pre-determined sample sizes), although reporting for retention was better (69 % of studies provided sufficient information to determine whether individual retention strategies achieved adequate retention rates). Guidance is required for researchers on how to improve reporting practices to help improve recruitment and retention strategies for use with young adult population samples.

Recruitment findings

In terms of recruitment, 77 % of studies had participant recruitment that met pre-determined sample sizes, with face-to-face recruitment most likely to achieve recruitment goals. This is higher when compared with another review (n 151 RCT) of recruitment data from trials that had no restrictions for age and found 56 % of studies achieved their target sample size(144). The most efficient strategy was advertising through letters. However, results from the current review should be interpreted with caution. Given that 79 % of studies used a university setting to recruit potential participants, findings may not be applicable to other settings.

When planning health behaviour interventions with young adults, researchers need to consider the efficiency of recruitment approaches in order to make the most of available resources and time. Despite the limitations relating to poor reporting of recruitment rates, the review provides some guidance for researchers working with young adults in regard to the number of participants required to respond to recruitment strategies to ensure a sufficient sample size is recruited. Our findings suggest just under one-third of young adults who express interest and/or are screened for eligibility then provide consent and participate in the study. Of those individuals who meet study inclusion criterion, almost two-thirds go on to participate in a study. Practically speaking if a sample of ˜100 young adults is required, this means that ˜300 young adults must be engaged by the recruitment strategies and screened for eligibility, of which ˜200 would meet inclusion criteria, and ˜100 would go on to participate in the study. Furthermore, studies focusing on weight gain prevention or weight loss took longer to recruit the target sample (mean of 375 d and 183 d) compared with studies focusing on nutrition and/or physical activity. They also screened more people and reported a much lower proportion of those expressing interest being randomised (47·6 % and 29·3 %). This is likely due to stricter inclusion criteria, but is an important consideration for studies focusing on weight with a need to allocate extra time and resources for recruitment.

Few studies reported the cost information related to recruitment (n 3 studies). In these studies, recruitment costs in ascendency were US$20 729 to enrol 338 participants, US$32 861·98 to enrol 250 participants and US$139 543 to enrol 609 participants. However, in-kind support from the University (i.e. University e-newsletter) was common; therefore, costs will likely be higher if recruiting outside of a University setting. The costs associated with recruiting young adults may be higher than other population groups due to extra challenges of recruiting this population group(24). When compared with another systematic review of physical activity interventions among all adults (19 years of age and above), costs per participant recruited were approximately US$27·62 (reported as £20·32 but converted to USD for comparison)(145). Although this was only reported in one study in the review, this appears lower than costs per participant recruited in this current review which ranged from US$45 to US$232·96.

The recruitment strategies predominantly used were more traditional, such as flyers and email, as opposed to ‘newer’ strategies, such as online advertising and social media. This is consistent with other reviews which have reported this information(24,146). There is potential to further explore the success of ‘newer’ strategies, given the high use and engagement with electronic and social media among young adults(147). The use of online platforms for intervention delivery (e.g. e-Health and mHealth) has advanced substantially in recent years among young adults and was the most common mode of intervention delivery identified in this review. However, there has not been the same rise in use of online platforms as a means of recruitment.

Comparably, other reviews of recruitment data among physical activity interventions(145,146), mental health trials(148) and those using digital tools(149) to recruit have all highlighted inadequate reporting and evaluation, while accentuating the need for better guidance in reporting(150). Recently, the ORRCA project (Online Resource for Recruitment research in Clinical triAls, www.orrca.org.uk) has created a database of all RCT on recruitment to help improve recruitment of participants into trials.

Research question #10: What reporting is needed to assess the success of recruitment strategies?

Gaps in reporting of key recruitment information mean that the success of recruitment strategies could not be evaluated sufficiently. Similarly, issues with reporting recruitment information were emphasised in the 2016 review on weight gain prevention interventions by Lam et al.(24). It was hoped that the review by Lam et al. would illicit better reporting, but gaps still remain. As such, we have outlined the key recruitment information that should be reported in trials and the benefits of reporting this information (Table 7).

Table 7.

Key reporting information for recruitment in trials

| Recruitment information required | Benefits of providing this information |

|---|---|

| Required/goal sample size | Will help to determine if recruitment strategies reached the numbers required to maintain statistical power. |

| Duration of recruitment period | Will assist with determining the efficiency of recruitment strategies. |

| Detailed eligibility criteria and geographical location of the study/population | Provide reasoning for delays in recruitment (i.e. strict criteria likely to take longer) and enable stratification analysis based on different population groups and criteria. |

| Numbers invited to participate, interested/screened, eligible and enrolled/randomised by recruitment method. | This will indicate the numbers required at each stage and the success of each specific recruitment method. |

| Recruitment setting | Will help to determine which recruitment methods are the most effective across the different settings. |

| All recruitment methods utilised with sufficient detail | Insufficient detail is often provided. For example, by reporting “Social media”, it is unclear if paid advertising was used or if it was simply shared by the research team on social media. Also, providing more detail on the specifics of each recruitment method (e.g. messaging, content) will be vital to determine which aspects are effective. |

| Frequency of contact (where applicable) | In most cases, it is unclear how often potential participants were contacted. For example, if social media advertisements were used, how many and how often were advertisements displayed to potential participants? This will be useful in determining the level of contact or exposure required to recruit participants. |

| Cost/expenditure of recruitment methods | Providing the cost and currency will help to determine the cost per participant recruited. |

| Recruitment incentives (i.e. incentive to complete baseline survey) and associated cost | This information will help to determine which incentives may enhance recruitment. |

| Participant burden: length of time and requirements (i.e. online survey, blood tests, in-person measurements) to complete baseline assessment and overall commitment requirements of programme. | Baseline measures that take a considerable amount of time and obligation (i.e. blood test) may prevent potential participants from taking part. Therefore, this information is vital to determine the level of participant burden and will help in understanding any difficulties with achieving required sample size or if changes are required to the number of measures collected at baseline. |

| Representativeness of participants recruited | Will help to determine if particular recruitment strategies are more likely to recruit population sub-groups. |

Retention findings

In terms of retention, 65 % of studies had adequate retention and the most successful retention strategy was course credit. The mean ± sd retention rate of 83 ± 14 % is slightly lower when compared with another review by Walters et al. (n 151 RCT) that had no restrictions for age and reported an average retention rate of 89 %(144). Of note, this current review included fewer longer-term trials with only 38 % having follow-up >6 months from baseline, compared with 64 % in the Walters review(144). Thus, young adults are likely to be harder to retain in the long term. Although reporting of retention was better than recruitment (69 % of studies provided sufficient information about retention strategies), results should be interpreted with caution. As was the case for the recruitment results, findings for retention (i.e. use of course credit) will unlikely be applicable outside of University or College settings.

Research question #11: What reporting is needed to assess the success of retention strategies?

Gaps in reporting retention information prevented detailed insights to inform successful retention strategies for use in this age group. Comparatively, a systematic review of smoking, nutrition, alcohol, physical activity and obesity RCT (n 10) also highlighted reporting issues about retention(25). Therefore, we have outlined in Table 8 the key retention information to be reported in trials and the benefits of reporting this information.

Table 8.

Key reporting information for retention in trials

| Retention information required | Benefits of providing this information |

|---|---|

| Duration of programme/intervention and duration of each follow-up time point from end of intervention | Will help to contextualise the numbers retained and help determine retention. |

| Information on completers and non-completers | This information will help to determine any equity issues. |

| Number of participants retained at the end of the intervention and at each follow-up time point | This information will help to determine what strategies maximise retention. |

| Participant burden: length of time and requirements (i.e. online survey, blood tests, in-person measurements) to complete assessments at end of intervention and all follow-up time points | Assessment measures that take a considerable amount of time and obligations (i.e. blood test) may prevent participants from returning for end of intervention or follow-up assessments. Therefore, this information may help to provide context to low retention rates. |

| All retention methods utilised with sufficient detail | Insufficient detail is often provided for retention. For example, instead of reporting “emails were sent,” provide information on the number of emails sent and the tone, format and messaging in the emails to help determine the success of specific strategies. |

| Frequency of contact (where applicable) | In most cases, it is unclear how often potential participants were contacted to aid in retention. For example, if participants were contacted via email to invite them to attend follow-up assessments, it would be useful to provide the number and frequency of these emails. This will help in determining the level of contact or exposure required to retain participants. |

| Cost/expenditure of retention methods | Providing the cost and currency will help to determine the cost per participant retained. |

Once more studies are available with detailed information on recruitment and retention, as outlined in Table 7 and Table 8, it will be worthwhile to update the current review. Providing greater detail on these aspects will assist with truly determining successful, cost-effective and efficient strategies to recruit and retain young adults. Furthermore, this information will help ensure statistical power is achieved and retained, leading to fewer false-negative findings. Finally, project co-ordinators will be better informed on ways to improve budgeting, planning and time management.

Strengths and limitations of the review

This review is the largest and most comprehensive review to evaluate recruitment and retention information from behavioural interventions targeting nutrition, physical activity or overweight/obesity in young adults. Furthermore, the quantification of recruitment and retention success, efficiency and cost is useful to inform future study planning. There are a number of limitations to acknowledge. Primarily, to be included, all participants were required to be within the age range of 17–35 years. As such, this risks excluding studies that included mainly young adults but also had some outside the age range. In addition, the calculations to determine the success of individual recruitment and retention strategies were basic (i.e. number of times the strategy was used in a study with recruitment or retention meeting criteria/the total number of times the strategy was used in a study). In implementing this approach, we were unable to determine if certain strategies had more ‘weighting’ with regard to recruitment or retention success. However, this approach was considered most appropriate as few studies provided recruitment and retention numbers by each strategy. Exploration of the combinations of recruitment and retention strategies was not feasible due to the large number of combinations with very few studies using the exact same combination of strategies and thus may result in false-positive or false-negative findings. For the recruitment rate calculation, a denominator of all those reached was not used because of the difficulty of measuring reach when passive/reactive recruitment strategies are used that require the potential participants to contact the research team. The definition of adequate retention is limited in that the cut-off of 6-months for follow-up does not consider additional cut-offs for studies with longer-term follow-up (e.g. >12 months). However, in this review, only 15 % of studies included follow-up >12 months from baseline. In addition, studies were limited to those published in English, which may have excluded relevant studies and could limit the generalisability of the findings.

Recommendations from this research

Future studies should report complete details of recruitment and retention as outlined in Table 7 and Table 8 within the main paper or in protocol papers or Supplementary information. Alternatively, journals and researchers should publish papers specifically focusing on recruitment and retention.

Greater focus on recruiting diverse samples of young adults and determining successful strategies to do so. In particular, different ethnicities and samples from a variety of socio-economic backgrounds.

Researchers should consider the number of young adults that need to be reached to recruit the pre-determined sample size. Based on the current review, if a sample recruitment target is 100 young adults, then at least 300 participants need to be engaged by recruitment strategies.

Researchers should consider sufficient costs when budgeting for recruitment and retention. Recruitment costs per participant randomised in the university setting ranged from US$45 to US$232·96. Furthermore, median retention costs were US$22·55 per participant retained (range: US$0·50 to US$553·83).

Conclusions

Overall, the current review emphasises poor reporting of recruitment, retention and related costs within behavioural interventions that include young adults. Due to the large proportion of studies that have used a university setting to recruit potential participants, findings may not be applicable to other settings. Guidance is required for researchers on how to improve reporting practices to help better establish recruitment and retention strategies for use with young adult populations. Essential recruitment and retention data are required in established checklists of reporting for trials (e.g. CONSORT) or as an extension. An update of this review will be required once a sufficient number of new studies publish essential recruitment and retention data.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: Not applicable. Financial support: This research was supported by the School of Health Sciences strategic pilot grant (University of Newcastle). C.E.C. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Senior Research Fellowship, and a Gladys M Brawn Senior Research Fellowship from the Faculty of Health and Medicine, the University of Newcastle, Australia. F.T. was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Career Development Fellowship (APP1143269). The funding bodies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Conflict of interest: None of the authors had any financial support or relationships that may pose a conflict of interest. Authorship: CRediT Author statement contributions: M.C.W.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation and writing – original draft; M.J.H.: funding acquisition, conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, writing – original draft and supervision; T.S.: investigation and data curation; R.L.H.: investigation and writing – review & editing; A.B.: investigation and writing – review & editing; C.E.C.: funding acquisition, conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, writing – review & editing and supervision; F.T.: writing – original draft; L.M.A.: funding acquisition, methodology, conceptualisation, formal analysis, data curation, investigation, writing – original draft, project administration and supervision. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021001129.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Liu K, Daviglus ML, Loria CM et al. (2012) Healthy lifestyle through young adulthood and the presence of low cardiovascular disease risk profile in middle age: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults (CARDIA) study. Circulation 125, 996–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zheng Y, Manson JE, Yuan C et al. (2017) Associations of weight gain from early to middle adulthood with major health outcomes later in life. JAMA 318, 255–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Australian Bureau of Statistics (2012) Australian Health Survey: First Results, 2011–12. Canberra: ABS. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018) National Health Survey: First Results, 2017–18. Canberra: ABS. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015) Normal weight, overweight and obesity among adults aged 20 and over, by selected characteristics: United States, selected years 1988–1994 through 2011–2014. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2015/058.pdf

- 6. Imamura F, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S et al. (2015) Dietary quality among men and women in 187 countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic assessment. Lancet Glob Health 3, e132–e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Corder K, Winpenny E, Love R et al. (2019) Change in physical activity from adolescence to early adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Br J Sports Med 53, 496–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ashton LM, Sharkey T, Whatnall MC et al. (2020) Which behaviour change techniques within interventions to prevent weight gain and/or initiate weight loss improve adiposity outcomes in young adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev 21, e13009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ashton LM, Sharkey T, Whatnall MC et al. (2019) Effectiveness of interventions and behaviour change techniques for improving dietary intake in young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. Nutrients 11, 825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Willmott TJ, Pang B, Rundle-Thiele S et al. (2019) Weight management in young adults: systematic review of electronic health intervention components and outcomes. J Med Internet Res 21, e10265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nour M, Chen J & Allman-Farinelli M (2016) Efficacy and external validity of electronic and mobile phone-based interventions promoting vegetable intake in young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 18, e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oosterveen E, Tzelepis F, Ashton L et al. (2017) A systematic review of eHealth behavioral interventions targeting smoking, nutrition, alcohol, physical activity and/or obesity for young adults. Prev Med 99, 197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Partridge SR, Juan SJ, McGeechan K et al. (2015) Poor quality of external validity reporting limits generalizability of overweight and/or obesity lifestyle prevention interventions in young adults: a systematic review. Obes Rev 16, 13–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Poobalan AS, Aucott LS, Precious E et al. (2010) Weight loss interventions in young people (18 to 25 year olds): a systematic review. Obes Rev 11, 580–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gul RB & Ali PA (2010) Clinical trials: the challenge of recruitment and retention of participants. J Clin Nurs 19, 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moe SG, Lytle LA, Nanney MS et al. (2016) Recruiting and retaining young adults in a weight gain prevention trial: lessons learned from the CHOICES study. Clin Trials 13, 205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ashton LM, Hutchesson MJ, Rollo ME et al. (2016) Motivators and barriers to engaging in healthy eating and physical activity: a cross-sectional survey in young adult men. Am J Men’s Health 11, 330–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Poobalan A & Aucott L (2016) Obesity among young adults in developing countries: a systematic overview. Curr Obes Rep 5, 2–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bower P, Brueton V, Gamble C et al. (2014) Interventions to improve recruitment and retention in clinical trials: a survey and workshop to assess current practice and future priorities. Trials 15, 399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Torgerson JS, Arlinger K, Kappi M et al. (2001) Principles for enhanced recruitment of subjects in a large clinical trial. the XENDOS (XENical in the prevention of Diabetes in Obese Subjects) study experience. Controlled Clin Trials 22, 515–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gul RB & Ali PA (2010) Clinical trials: the challenge of recruitment and retention of participants. J Clin Nurs 19, 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tate DF, LaRose JG, Griffin LP et al. (2014) Recruitment of young adults into a randomized controlled trial of weight gain prevention: message development, methods, and cost. Trials 15, 326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crane MM, LaRose JG, Espeland MA et al. (2016) Recruitment of young adults for weight gain prevention: randomized comparison of direct mail strategies. Trials 17, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lam E, Partridge SR & Allman-Farinelli M (2016) Strategies for successful recruitment of young adults to healthy lifestyle programmes for the prevention of weight gain: a systematic review. Obes Rev 17, 178–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ashton LM, Morgan PJ, Hutchesson MJ et al. (2015) A systematic review of SNAPO (Smoking, Nutrition, Alcohol, Physical activity and Obesity) randomized controlled trials in young adult men. Prev Med 81, 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sharkey T, Whatnall MC, Hutchesson MJ et al. (2020) Effectiveness of gender-targeted versus gender-neutral interventions aimed at improving dietary intake, physical activity and/or overweight/obesity in young adults (aged 17–35 years): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr J 19, 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Institute of Health (2010) Trials use technology to help young adults achieve healthy weights. http://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/trials-use-technology-help-young-adults-achieve-healthy-weights (accessed July 2019).

- 28. White A, De Sousa B, De Visser R et al. (2011) The State of Men’s Health in Europe: Extended Report. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/state/docs/men_health_extended_en.pdf (accessed July 2020).

- 29. Open Universities Australia (2021) Minimum age requirements. https://www.open.edu.au/your-studies/getting-started/minimum-age-requirements (accessed January 2021).

- 30. The Open University (2020) Policy for the admission of applications under the age of 18. https://help.open.ac.uk/documents/policies/admission-of-applicants-under-the-age-18/files/2/admission-under-18.pdf (accessed January 2021).

- 31. Carroll JK, Yancey AK, Spring B et al. (2011) What are successful recruitment and retention strategies for underserved populations? Examining physical activity interventions in primary care and community settings. Translational Behav Med 1, 234–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Sluijs EM, McMinn AM & Griffin SJ (2007) Effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in children and adolescents: systematic review of controlled trials. BMJ 335, 703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Engbers LH, van Poppel MN, Paw MJ et al. (2005) Worksite health promotion programs with environmental changes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 29, 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Young MD, Morgan PJ, Plotnikoff RC et al. (2012) Effectiveness of male-only weight loss and weight loss maintenance interventions: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Obes Rev 13, 393–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Allman-Farinelli M, Partridge SR, McGeechan K et al. (2016) A mobile health lifestyle program for prevention of weight gain in young adults (TXT2BFiT): nine-month outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 4, e78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Amiot CE, El Hajj Boutros G, Sukhanova K et al. (2018) Testing a novel multicomponent intervention to reduce meat consumption in young men. PLoS One 13, e0204590–e0204590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Annesi JJ, Howton A, Johnson PH et al. (2015) Pilot testing a cognitive-behavioral protocol on psychosocial predictors of exercise, nutrition, weight, and body satisfaction changes in a college-level health-related fitness course. J Am Coll Health 63, 268–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ashton LM, Morgan PJ, Hutchesson MJ et al. (2017) Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the ‘HEYMAN’ healthy lifestyle program for young men: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Nutr J 16, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bailey BW, Bartholomew CL, Summerhays C et al. (2019) The impact of step recommendations on body composition and physical activity patterns in college freshman women: a randomized trial. J Obes 2019, 4036825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bertz F, Pacanowski CR & Levitsky DA (2015) Frequent self-weighing with electronic graphic feedback to prevent age-related weight gain in young adults. Obesity 23, 2009–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bray SR, Beauchamp MR, Latimer AE et al. (2011) Effects of a print-mediated intervention on physical activity during transition to the first year of university. Behav Med 37, 60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brookie KL, Mainvil LA, Carr AC et al. (2017) The development and effectiveness of an ecological momentary intervention to increase daily fruit and vegetable consumption in low-consuming young adults. Appetite 108, 32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brown ON, O’Connor LE & Savaiano D (2014) Mobile MyPlate: a pilot study using text messaging to provide nutrition education and promote better dietary choices in college students. J Am Coll Health 62, 320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Buscemi J, Yurasek AM, Dennhardt AA et al. (2011) A randomized trial of a brief intervention for obesity in college students. Clin Obes 1, 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Butryn ML, Forman E, Hoffman K et al. (2011) A pilot study of acceptance and commitment therapy for promotion of physical activity. J Phys Activity Health 8, 516–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Calfas KJ, Sallis JF, Nichols JF et al. (2000) Project GRAD: two-year outcomes of a randomized controlled physical activity intervention among young adults. Graduate ready for activity daily. Am J Prev Med 18, 28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cambien F, Richard JL, Ducimetiere P et al. (1981) The Paris Cardiovascular Risk Factor Prevention Trial. Effects of two years of intervention in a population of young men. J Epidemiol Community Health 35, 91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Carfora V, Bertolotti M & Catellani P (2019) Informational and emotional daily messages to reduce red and processed meat consumption. Appetite 141, 104331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chang MW, Nitzke S & Brown R (2010) Design and outcomes of a Mothers in motion behavioral intervention pilot study. J Nutr Educ Behav 42, S11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chapman J, Armitage CJ & Norman P (2009) Comparing implementation intention interventions in relation to young adults’ intake of fruit and vegetables. Psychol Health 24, 317–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chiang T-L, Chen C, Hsu C-H et al. (2019) Is the goal of 12,000 steps per day sufficient for improving body composition and metabolic syndrome? The necessity of combining exercise intensity: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 19, 1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Conner M, Rhodes RE, Morris B et al. (2011) Changing exercise through targeting affective or cognitive attitudes. Psychol Health 26, 133–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cooke PA, Tully MA, Cupples ME et al. (2013) A randomised control trial of experiential learning to promote physical activity. Educ for Primary Care 24, 427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cooke R, Trebaczyk H, Harris P et al. (2014) Self-affirmation promotes physical activity. J Sport Exercise Psychol 36, 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Do M, Kattelmann K, Boeckner L et al. (2008) Low-income young adults report increased variety in fruit and vegetable intake after a stage-tailored intervention. Nutr Res 28, 517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Eiben G & Lissner L (2006) Health Hunters – an intervention to prevent overweight and obesity in young high-risk women. Int J Obes 30, 691–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Eisenberg MH, Phillips L, Fowler L et al. (2017) The impact of E-diaries and accelerometers on young adults’ perceived and objectively assessed physical activity. Psychol Sport Exerc 30, 55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Franko DL, Cousineau TM, Trant M et al. (2008) Motivation, self-efficacy, physical activity and nutrition in college students: randomized controlled trial of an internet-based education program. Prev Med: Int J Devoted Pract Theor 47, 369–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Franko DL, Jenkins A & Rodgers RF (2012) Toward reducing risk for eating disorders and obesity in latina college women. J Couns Dev 90, 298–307. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Godino JG, Merchant G, Norman GJ et al. (2016) Using social and mobile tools for weight loss in overweight and obese young adults (Project SMART): a 2 year, parallel-group, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 4, 747–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gokee-LaRose J, Gorin AA & Wing RR (2009) Behavioral self-regulation for weight loss in young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity 6, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Goodman S, Morrongiello B & Meckling K (2016) A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of an online intervention targeting vitamin D intake, knowledge and status among young adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity 13, 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gow RW, Trace SE & Mazzeo SE (2010) Preventing weight gain in first year college students: an online intervention to prevent the “freshman fifteen.” Eating Behav 11, 33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Greene GW, White AA, Hoerr SL et al. (2012) Impact of an online healthful eating and physical activity program for college students. Am J Health Promotion 27, E47–E58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Halperin DT, Laux J, LeFranc-García C et al. (2019) Findings from a randomized trial of weight gain prevention among overweight Puerto Rican young adults. J Nutr Educ Behav 51, 205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hebden L, Cook A, van der Ploeg HP et al. (2014) A mobile health intervention for weight management among young adults: a pilot randomised controlled trial. J Hum Nutr Diet 27, 322–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Heeren GA, Jemmott JB, Marange CS et al. (2017) Health-promotion intervention increases self-reported physical activity in Sub-Saharan African university students: a randomized controlled pilot study. Behav Med 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hivert M, Langlois M, Berard P et al. (2007) Prevention of weight gain in young adults through a seminar-based intervention program. Int J Obes 31, 1262–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Husband CJ, Wharf-Higgins J & Rhodes RE (2019) A feasibility randomized trial of an identity-based physical activity intervention among university students. Health Psychol Behav Med 7, 128–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hutchesson M, Callister R, Morgan P et al. (2018) A targeted and tailored eHealth weight loss program for young women: the be positive be healthy randomized controlled trial. Healthcare 6, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jakicic JM, Davis KK, Rogers RJ et al. (2016) Effect of wearable technology combined with a lifestyle intervention on long-term weight loss: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc 316, 1161–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Jauho AM, Pyky R, Ahola R et al. (2015) Effect of wrist-worn activity monitor feedback on physical activity behavior: a randomized controlled trial in Finnish young men. Prev Med Rep 2, 628–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Johnson KC, Thomas F, Richey P et al. (2017) The primary results of the Treating Adult Smokers at Risk for Weight Gain with Interactive Technology (TARGIT) study. Obesity 25, 1691–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Jung ME, Martin Ginis KA, Phillips SM et al. (2011) Increasing calcium intake in young women through gain-framed, targeted messages: a randomised controlled trial. Psychol Health 26, 531–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kattelmann KK, Bredbenner CB, White AA et al. (2014) The effects of Young Adults Eating and Active for Health (YEAH): a theory-based web-delivered intervention. J Nutr Educ Behavior 46, S27–S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Katterman SN, Butryn ML, Hood MM et al. (2016) Daily weight monitoring as a method of weight gain prevention in healthy weight and overweight young adult women. J Health Psychol 21, 2955–2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Katterman SN, Goldstein SP, Butryn ML et al. (2014) Efficacy of an acceptance-based behavioral intervention for weight gain prevention in young adult women. J Contextual Behav Sci 3, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kendzierski D, Ritter RL, Stump TK et al. (2015) The effectiveness of an implementation intentions intervention for fruit and vegetable consumption as moderated by self-schema status. Appetite 95, 228–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kerr DA, Harray AJ, Pollard CM et al. (2016) The connecting health and technology study: a 6-month randomized controlled trial to improve nutrition behaviours using a mobile food record and text messaging support in young adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity 13, 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kim Y, Lumpkin A, Lochbaum M et al. (2018) Promoting physical activity using a wearable activity tracker in college students: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Sports Sci 36, 1889–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Klem ML, Viteri JE & Wing RR (2000) Primary prevention of weight gain for women aged 25–34: the acceptability of treatment formats. Int J Obes 24, 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Knauper B, McCollam A, Rosen-Brown A et al. (2011) Fruitful plans: adding targeted mental imagery to implementation intentions increases fruit consumption. Psychol Health 26, 601–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kothe EJ & Mullan BA (2014) A randomised controlled trial of a theory of planned behaviour to increase fruit and vegetable consumption. Fresh Facts Appetite 78, 68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kothe EJ, Mullan BA & Butow P (2012) Promoting fruit and vegetable consumption. Testing an intervention based on the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite 58, 997–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kreausukon P, Gellert P, Lippke S et al. (2012) Planning and self-efficacy can increase fruit and vegetable consumption: a randomized controlled trial. J Behav Med 35, 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kypri K & McAnally HM (2005) Randomized controlled trial of a web-based primary care intervention for multiple health risk behaviors. Prev Med 41, 761–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. LaChausse RG (2012) My student body: effects of an internet-based prevention program to decrease obesity among college students. J Am Coll Health 60, 324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. LaRose JG, Tate DF, Gorin AA et al. (2010) Preventing weight gain in young adults: a randomized controlled pilot study. Am J Prev Med 39, 63–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. LaRose JG, Tate DF, Lanoye A et al. (2019) Adapting evidence-based behavioral weight loss programs for emerging adults: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Health Psychol 24, 870–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Laska MN, Lytle LA, Nanney MS et al. (2016) Results of a 2-year randomized, controlled obesity prevention trial: Effects on diet, activity and sleep behaviors in an at-risk young adult population. Prev Med: Int J Devoted Pract Theor 89, 230–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. LeCheminant JD, Smith JD, Covington NK et al. (2011) Pedometer use in university freshmen: a randomized controlled pilot study. Am J Health Behav 35, 777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Leinonen AM, Pyky R, Ahola R et al. (2017) Feasibility of gamified mobile service aimed at physical activation in young men: population-based randomized controlled study (MOPO). JMIR mHealth uHealth 5, e146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Lhakhang P, Godinho C, Knoll N et al. (2014) A brief intervention increases fruit and vegetable intake. A comparison of two intervention sequences. Appetite 82, 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Lua PL, Wan Dali WPE & Shahril MR (2013) Multimodal nutrition education intervention: a cluster randomised controlled trial study on weight gain and physical activity pattern among university students in Terengganu, Malaysia. Malays J Nutr 19, 339–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Lyzwinski LN, Caffery L, Bambling M et al. (2019) The mindfulness app trial for weight, weight-related behaviors, and stress in University students: randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 7, e12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]