Abstract

Introduction:

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)- and AmpC β-lactamase (AmpC)-producing Escherichia coli from livestock and meat represent a zoonotic risk and biocontrol solutions are needed to prevent transmission to humans.

Methods:

In this study, we established a representative collection of animal-origin ESBL/AmpC E. coli as target to test the antimicrobial potential of bacteriophages.

Results:

Bioinformatic analysis of whole-genome sequence data of 198 ESBL/AmpC E. coli from pigs, broilers, and broiler meat identified strains belonging to all known E. coli phylogroups and 65 multilocus sequence types. Various ESBL/AmpC genes and plasmid types were detected with expected source-specific patterns. Plaque assay using 15 phages previously isolated using the E. coli reference collection demonstrated that Warwickvirus phages showed the broadest host range, killing up to 26 strains.

Conclusions:

154/198 strains were resistant to infection by all phages tested, suggesting a need for isolating phages specific for ESBL/AmpC E. coli. The strain collection described in this study is a useful resource fulfilling such need.

Keywords: strain collection, ESBL/AmpC-producing Escherichia coli, extended-spectrum β-lactamase, bacteriophages, biocontrol

Introduction

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)- and AmpC β-lactamase (AmpC)-producing Escherichia coli (ESBL/AmpC E. coli) are commonly isolated from livestock and meat.1 ESBL/AmpC E. coli of animal origin may transfer to humans through direct contact with animals and/or ingestion of contaminated food. Once they have reached the human gut, ESBL/AmpC E. coli may be implicated in infection and/or the transfer of ESBL/AmpC-encoding plasmids to other E. coli causing infection. The extent of this zoonotic risk has not been fully elucidated to date. Nonetheless, as infections by ESBL E. coli have been associated with increased morbidity and mortality in humans,2,3 a reduction in the occurrence of ESBL/AmpC E. coli in animals and food is a widely supported veterinary public health measure. This has constituted the background for Commission Implementing Decision 2020/1729/EU mandating a specific ESBL/AmpC monitoring program in the EU.

Several management approaches such as improved hygiene measures and increased biosecurity levels have been implemented in livestock production, but with limited impact on the ESBL/AmpC E. coli populations (reviewed in Ref.4). Similarly, probiotic treatments for competitive exclusion with different commercial products and dosages showed reduction but did not eliminate ESBL/AmpC E. coli in broiler flocks.5 Thus, there is a need for novel solutions for biocontrol of ESBL/AmpC E. coli in the livestock reservoir.

Bacteriophages (phages) are natural predators of bacteria that can be used as an alternative to antimicrobials in livestock, food, and humans (reviewed in Ref.6). Importantly, phages are highly specific for their bacterial host, and kill only specific species or even specific strains, thus leaving the remaining microbiota intact. Moreover, phages only replicate in the presence of a suitable host and are eliminated from the system if the host is killed or removed.

Phages have been used to target E. coli in diverse contexts such as urinary tract infections in humans, the gut, and diverse foods such as beverages, vegetables, and meat.7–11 For example, a three-phage cocktail applied on tomatoes, spinach, broccoli, and ground beef experimentally contaminated with the foodborne pathogen E. coli O157:H7 reduced the pathogen with up to 3 logs.7 The E. coli reference collection (ECOR)12 has proven useful for isolating phages for targeting E. coli13 as it covers all phylogroups and contains both commensal and pathogenic strains. Yet, it may not represent the genomic and plasmid diversity of ESBL/AmpC E. coli.

In this study, we aim to establish a collection of ESBL/AmpC E. coli representing the diversity of strain, plasmid and enzyme types described in pigs, broilers, and broiler meat, which are the animal sources with the highest occurrence of ESBL/AmpC E. coli in Denmark. Subsequently, we aim to evaluate the efficiency of a phage collection isolated on ECOR13 for biocontrol against animal-origin ESBL/AmpC E. coli.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and phages

A total of 198 ESBL/AmpC E. coli isolated from broilers (n = 29), broiler meat (n = 100), and pig caeca (n = 69) in 2015 and 2016 and whole genome sequenced within DANMAP, the Danish Program for surveillance of antimicrobial consumption and resistance in bacteria from food animals, food, and humans,14,15 were included in this study (Supplementary Table S1). Phages used for susceptibility testing are listed in Table 1 together with their isolation hosts.13

Table 1.

Bacteriophages Used in This Study

| Phagea | Family | Genus | Genome length (bp) | Accession | Isolation hostb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC120 | Autographiviridae | Vectrevirus | 44,544 | ON185580.1 | ECOR4 |

| EC100 | Demerecviridae | Tequintavirus | 108,723 | OK665835.1 | ECOR4 |

| EC104 | Demerecviridae | Tequintavirus | 108,711 | ON185581.1 | ECOR19 |

| EC105 | Demerecviridae | Tequintavirus | 108,732 | ON185582.1 | ECOR20 |

| EC122 | Demerecviridae | Tequintavirus | 108,723 | ON185583.1 | ECOR20 |

| EC142 | Demerecviridae | Tequintavirus | 108,723 | ON185584.1 | ECOR4 |

| EC148 | Demerecviridae | Tequintavirus | 107,754 | ON185585.1 | ECOR4 |

| EC125 | Drexlerviridae | Warwickvirus | 50,477 | ON185586.1 | ECOR13 |

| EC167 | Drexlerviridae | Warwickvirus | 50,988 | ON185587.1 | ECOR20 |

| EC147 | Drexlerviridae | Hanrivervirus | 46,060 | ON185589.1 | ECOR4 |

| EC101 | Straboviridae | Tequatrovirus | 167,718 | OL310488.1 | ECOR4 |

| EC128 | Straboviridae | Tequatrovirus | 171,814 | ON210139.1 | ECOR20 |

| EC106 | Not identified | Felixounavirus | 87,829 | ON210138.1 | ECOR4 |

| EC150 | Not identified | Wifcevirus | 68,034 | ON210137.1 | ECOR36 |

| EC115 | Not identified | Dhillonvirus | 44,909 | ON210136.1 | ECOR20 |

Assembly of raw sequence data and phylogenetic analysis

The raw sequence data of the 198 ESBL/AmpC E. coli were retrieved from ENA (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) with accession numbers PRJEB14641, PRJEB14086, and PRJEB22091. The genomes were assembled de novo with SPAdes16 on Enterobase (http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/species/ecoli/search_strains) using the following quality parameters and thresholds to assess sequence data quality: sequence depth 30 × , number of contigs 300.

A total of 26 strains did not comply with the selected thresholds but were still included in the analysis to test phage susceptibility. Phylogroups were determined by in silico PCR typing according to the Clermont scheme.17,18 Multilocus sequence typing (MLST), soft core genome MLST (cgMLST) and annotation with Prokka19 were performed as part of the analysis pipeline on Enterobase. A phylogenetic tree was built in R (version i386 4.1.0) using libraries cluster and ape with cgMLST profiles, retrieved for all the strains from Enterobase, as input data. The phylogenetic tree was visualized using iTOL v6 software.20

Reconstruction of ESBL/AmpC plasmids

Plasmids carrying ESBL/AmpC genes were reconstructed from the raw sequence data using the closest related reference plasmid. In brief, the contigs with ESBL/AmpC genes were identified by BLAST against the ResFinder database v421 in the CLC Genomics Workbench 21.0.5 (Qiagen, Aarhus, Denmark). Using the contig with ESBL/AmpC gene for each respective strain, closely related plasmids were identified by nucleotide BLAST at NCBI (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and used as references for the reconstruction. This was done by mapping the trimmed reads against the identified reference plasmid (Supplementary Table S2) using the Map Reads to Reference function with the default settings in CLC Genomics Workbench 21.0.5.

Comparative sequence analysis of plasmids

The reconstructed ESBL/AmpC plasmids sharing the same replicon type were analyzed for sequence homology using BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG) version 0.9522 with the closest reference plasmid. The circular comparative genomic maps were rendered by BRIG with NCBI local blast-2.8.1+, with standard default parameters, but with 99% and 95% cutoffs set as the upper and lower thresholds, respectively.

Bacteriophage susceptibility testing

Bacteriophage susceptibility testing was performed according to Ref.23 In brief, E. coli strains were cultured using lysogeny broth (LB) and LB agar (LA) (Oxoid, Roskilde, Denmark). A total of 100 μL of overnight cultures were mixed with 4 mL of molten overlay LB (0.6% agar) for preparation of a bacterial lawn on LA. After settling for 20 min, plates were dried for 45 min with constant air flow in the laminar hood. To test susceptibility to bacteriophages, 5 μL of a 10-fold dilution of the phage stocks were first spotted onto to bacterial lawn of strains in the collection and incubated for 18–24 h at 37°C. If a clearing zone appeared, a plaque assay using serial dilutions up to 10–8 was performed to confirm phage infection by observing single plaques. The single plaques were counted and plaque forming units (PFU)/mL were calculated. The efficiency of plating (EOP) was determined by ratio of the titer on the tested strain to the titer of the phage on its isolation host.

Phage genome analyses

The whole genome alignment of the phage genomes was done in CLC Main Workbench 21.0.3 (Qiagen Digital Insights, Aarhus, Denmark) with the default parameters (minimum initial seed length: 15, allow mismatches in seeds: yes and minimum alignment block length: 100). Whole genome analysis was additionally done using clinker software24 with default parameters. In silico analysis of hypothetical phage proteins was done using Interpro25 and HHpred.26

Phage receptor, phage defense systems, and prophages analyses in ESBL/AmpC E. coli

Protein sequences of the ferrichrome iron receptor (FIR) were identified and aligned in CLC Genomics Workbench 21.0.5 with default parameters. Defense systems in the phages were identified using the PADLOC software27 with default parameters and including the option Run CRISPRDetect available on https://padloc.otago.ac.nz/padloc/. Prophage regions were identified using PHASTER software28 using multiple separated contigs of the ESBL/AmpC E. coli genomes in FASTA format as input and with option of using precomputed results if available on the website https://phaster.ca/

Results

The collection of ESBL/AmpC E. coli is genomically diverse

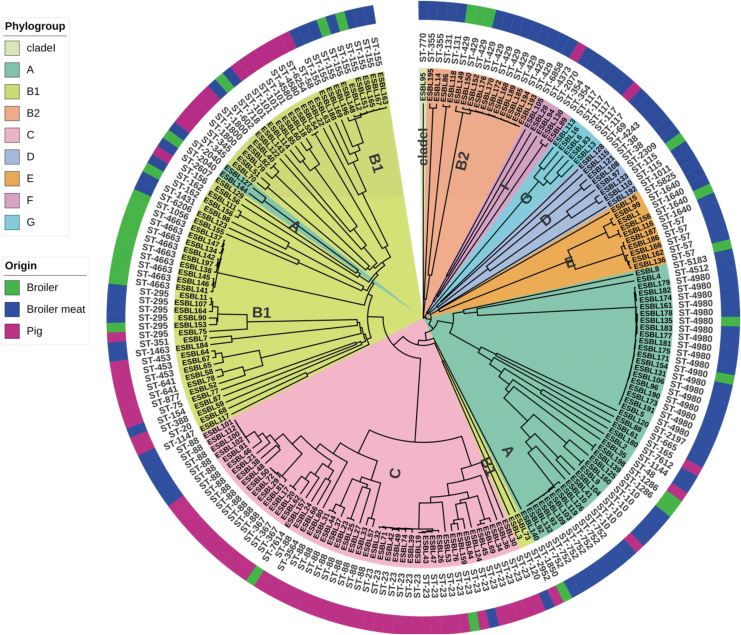

Phylogenetic analysis using the Clermont scheme revealed that all E. coli phylogenetic groups were represented in our collection of ESBL/AmpC E. coli (Fig. 1). Most strains were assigned to phylogroups B1 (30.8%), C (24.2%), and A (22.7%), but other phylogroups were also represented, including B2 (7.8%), E (5.1%), D (4%), F (2.5%), G (2.5%), and the cryptic clade I (0.5%). In addition, an origin-specific pattern was observed: Strains belonging to B1 were highly prevalent in all origin groups, whereas phylogroup A were specifically prevalent in broilers and broiler meat, and phylogroup C were prevalent in pigs (Fig. 1). MLST analysis identified 65 unique sequence types (STs) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of ESBL/AmpC Escherichia coli used in this study. Clustering of strains shown by phylogroups (A–G, and clade I in the inner circle) and ST (circle in the middle). Strain names are at the ends of the nodes of the tree. Outer circle represents the isolation sources. The tree is generated using the soft-cgMLST profile for all strains using sequences obtained from Enterobase and visualized using iTOL v5.20 AmpC, AmpC β-lactamase; cgMLST, core genome MLST; ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; MLST, multilocus sequence typing; ST, sequence type.

A few STs, such as ST429, ST752, and ST4980, included highly similar strains, whereas other STs, such as ST23 and ST88, were represented by genetically diverse strains. In addition, >50 STs were represented by few or single strains. Strains form broilers, broiler meat, and pigs were assigned to 16, 42, and 24 STs, respectively, with an overlap of STs among the different origin. By performing cgMLST consisting of 2515 genes, we observed high diversity as all strains except eight were assigned to distinct cgMLSTs (Supplementary Table S1). In summary, the phylogenetic analyses of the genomes demonstrate that our collection of ESBL/AmpC E. coli covers a broad diversity within E. coli.

Several ESBL/AmpC-encoding genes and plasmids are present within the collection

The ESBL-encoding genes identified in the collection were blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-55, blaSHV-12, blaTEM-52B, and blaTEM-52C and they were mostly encoded on plasmids (Table 2). In addition, a promoter mutation (C → T substitution at position -42) leading to upregulated chromosomal ampC expression was identified (Table 2). Interestingly, the distribution of ESBL/AmpC genes and plasmids was different among the three E. coli sources, but with some expected overlap between broilers and broiler meat. Among strains from broilers, most had ampC promoter mutations (38%), blaCMY-2 on IncK2 plasmids (31%) and blaCTX-M-1 on IncI1-Iα/ST3 and IncI1-Iα/ST7 plasmids (17%).

Table 2.

Genetic Location of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase and AmpC β-Lactamase Genes and Their Distribution According to Origin

| ESBL/AmpC gene | Genetic location | No. of strains (no. of STs) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broilers | Pigs | Broiler meat | Total | ||

| ampC promoter mutationa | Chromosome | 11 (3) | 52 (15) | 3 (3) | 66 (20) |

| bla CMY-2 | Chromosome | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | ||

| IncK2 | 9 (6) | 1 (1) | 25 (15) | 35 (18) | |

| IncI1-Iα/ST12 | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | |||

| IncC2 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |||

| bla CTX-M-1 | Chromosome | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | ||

| IncI1-Iα/ST3 | 4 (3) | 6 (5) | 43 (18) | 53 (22) | |

| IncI1-Iα/ST7 | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 9 (4) | 14 (7) | |

| ND | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | |||

| bla CTX-M-14 | IncK1 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| bla CTX-M-55 | IncI1-Iα/ST16 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| bla SHV-12 | Chromosome | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| IncI1-Iα/ST3 | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 4 (1) | ||

| ND | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | |||

| bla TEM-52B | IncX1 | 2 (1) | 7 (3) | 9 (4) | |

| bla TEM-52C | ColV | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| bla CARB-2 | Chromosome | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

C → T substitution at position -42 in the promoter.

ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; ND, not determined; STs, sequence types.

Strains originating from broiler meat showed that 53% harbored blaCTX-M-1 mainly on IncI1-Iα/ST3 plasmids, but also on IncI1-Iα/ST7 plasmids and the chromosome. Furthermore, 29% of broiler meat strains harbored blaCMY-2 mainly in association with IncK2 plasmids but also with IncI1-Iα/ST12 and IncC2 plasmids and on the chromosome. Among strains of pig origin, the majority had promoter mutations leading to chromosomal ampC overexpression (78%), and harbored blaCTX-M-1 on IncI1-Iα/ST3 or IncI1-Iα/ST7 plasmids as well as on the chromosome (18%). Overall, the distribution of ESBL/AmpC genes and plasmids was different among the three E. coli sources following specific pattern.

The ESBL-encoding plasmids show high similarity to published plasmids from animal and meat sources

Most plasmid encoded ESBL genes were located on contigs of sufficient length (40–80 kb) to reveal the genetic context and identify suitable reference plasmids, allowing us to reconstruct 117 plasmids by mapping the quality trimmed reads against reference plasmids (Supplementary Table S2). The reconstructed plasmids showed high sequence conservation in general. The main differences between the reconstructed plasmids and plasmid reference genomes are summarized in Table 3. Overall, the ESBL-encoding plasmids of our collection show high similarity to plasmids already identified as carrying ESBL genes.

Table 3.

Overview of Similarity of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Encoding Plasmids to Published Plasmids from Animal and Meat Sources

| Plasmid replicon | ESBL gene | No. in collection | Representative plasmid | Accession number | Similarity (%) | Coverage (%) | Main differences | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IncI1-Iα/ST3 | bla CTX-M-1 | 53 | p15095941 | MK181563 | 97–99 | 90–95 | Presence/absence of genes conferring antibiotic resistance, hypothetical proteins, and associated mobile genetic elements (Supplementary Fig. S1A) | Broiler meat |

| IncI1-Iα/ST3 | bla SHV-12 | 4 | pMB5876 | MK070495 | 99 | 98 | Shufflon region, regions coding mobile genetic elements (transposase IS66), and absence of blaPSE-4 (Supplementary Fig. S1B) | Broiler meat |

| IncI1-Iα/ST7 | bla CTX-M-1 | 14 | p15078279 | MK181566 | 95–99 | 90 | Absence of genes conferring antibiotic resistance and associated transposable elements (Supplementary Fig. S1C) | Pig |

| IncI1-Iα/ST12 | bla CMY-2 | 2 | pRHB17-C09_3 | CP057698 | 97–99 | 98 | Absence of one gene encoding a hypothetical protein and a putative prophage encoded protein (Supplementary Fig. S1D) | Pig |

| IncI1-Iα/ST16 | bla CTX-M-55 | 1 | pS29-IncI1 | CP085700 | 99 | 96 | Absence of a 3 kb region encoding a group II reverse transcriptase or maturase (Supplementary Fig. S1E) | Human, stool |

| IncK1 | bla CTX-M-14 | 1 | pCT | FN868832 | 99 | 97 | Absence of a region encoding three transposase genes (IS66 family transposase) (Supplementary Fig. S1F) | Cattle |

| IncK2 | bla CMY-2 | 34 | pESBL3156-IncBOKZ | MW390523 | 90–99 | 83–89 | A subset of strains shows absence of a few regions encoding genes with hypothetical functions, likely composing a sublineage of IncK2 plasmid group, yet with highly conserved backbone to the reference IncK2 plasmid (Supplementary Fig. S1G) | Broiler |

| IncC2 | bla CMY-2 | 1 | pAR060302 | NC_012692 | 99 | 98 | Differences within three hot spot regions encoding mobility genes and other antibiotic resistance genes (Supplementary Fig. S1H) | Cattle |

| IncX1 | bla TEM-52B | 9 | pDKX1-TEM-52B | JQ269336 | 95–99 | 100 | Overall, highly conserved but with SNPs (Supplementary Fig. S1I) | Broiler meat |

| ColV | bla TEM-52C | 1 | ND | The 5 kb contig with blaTEM-52C showed similarity to several ColV plasmids but could not be reconstructed | ND |

ND, not determined; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

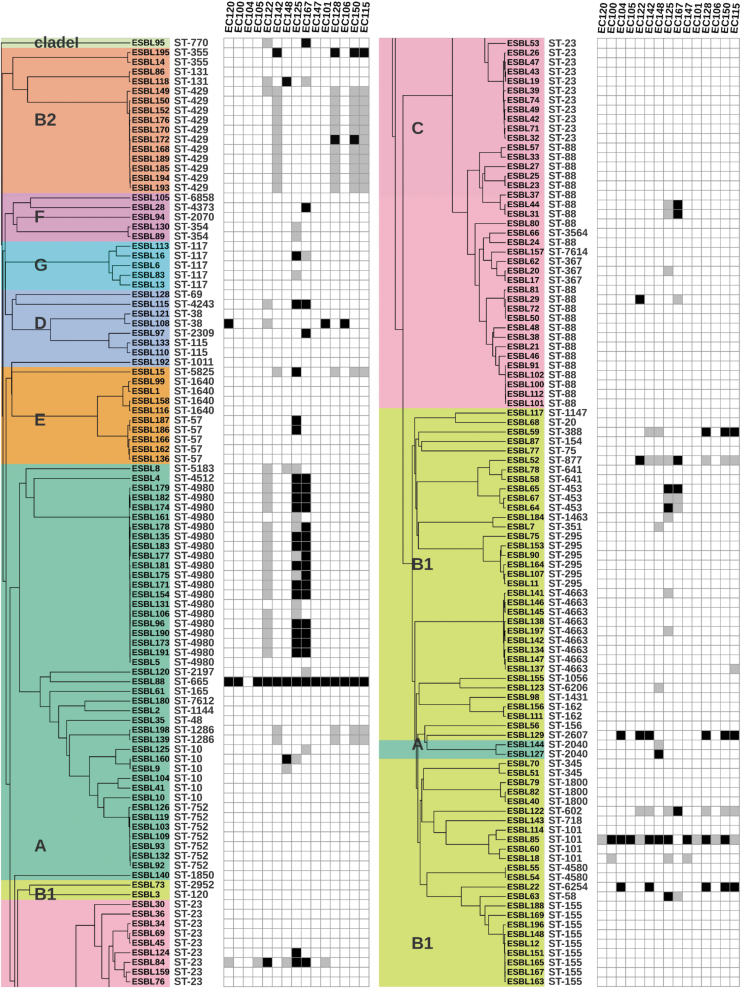

ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli show a high degree of phage resistance

To investigate the potential of applying phages for biocontrol of ESBL/AmpC E. coli, we determined the susceptibility of our strain collection to 15 phages previously isolated from a variety of sources using a well-characterized ECOR as host13 (Table 1). In this study, we determined the ability of each phage to form single plaques on each of the 198 ESBL/AmpC E. coli in our collection (Fig. 2). Interestingly, our analysis showed that most strains of the collection (n = 154) were resistant to all 15 phages. Overall, only 99 of all 2970 phage–strain combinations, corresponding to 3.3% of the total pairs, resulted in formation of single plaques. Among the 44 strains susceptible to phages, the majority (n = 37) were sensitive to only one or two phages and eight strains could be infected by three or more phages.

FIG. 2.

Phage sensitivity of ESBL/AmpC Escherichia coli used in this study. The phylogenetic tree of the strains is shown on the left with the respective phylogroups (A–G and clade I, all color coded as in Fig. 1). Their respective STs are indicated in the columns to the right. The phages are listed in the top part and sensitivity to the phages is indicated by the dark gray boxes representing lysis spots observed but no infection confirmed by plaque assay and black boxes, where the infection was confirmed by plaque assay. The figure is generated using iTOL v5.20

Most of these infections showed moderate EOP (0.1 > EOP >0.001) or low EOPs (<0.001), suggesting that the ECOR phages inefficiently infected the ESBL/AmpC E. coli collection (Supplementary Table S3). Strains infected by at least one phage belonged to 26 out of the 65 STs. However, most phages were only infecting a single strain within an ST, whereas others in the same ST were resistant to phage infection, suggesting no apparent correlation between phage sensitivity and ST. Overall, the ESBL/AmpC E. coli collection is highly resistant to the ECOR phages tested.

Phages belonging to Warwickvirus genus displayed the broadest host range

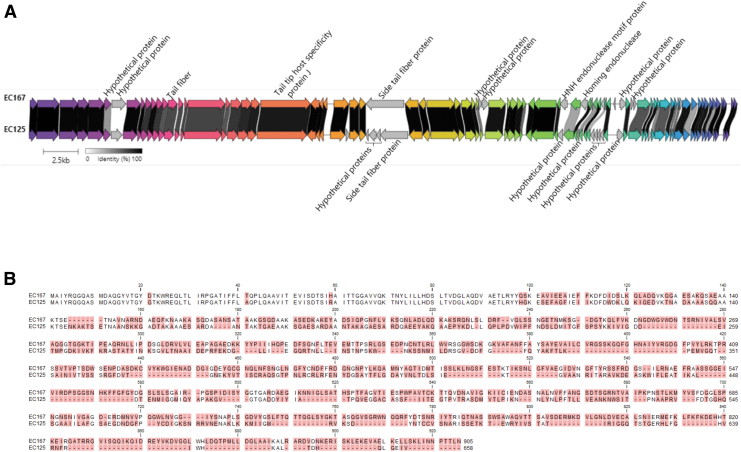

Warwickvirus phages EC125 and EC167 showed the broadest host range infecting 25 and 27 strains belonging to 16 ST of the ESBL/AmpC E. coli in our collection (Fig. 2). Genomic comparisons showed that EC125 and EC167 share 69.9% overall nucleotide identity or 84.2% over 83% query coverage (Fig. 3A). Major differences include genes encoding hypothetical proteins, homing endonucleases, and the region encoding the side tail fiber proteins recently suggested to bind O-antigen as a primary receptor29 (Fig. 3A). The predicted side tail fiber gene peg.29 of phage EC167 is 2718 bp aa, whereas the tail fiber peg.33 of phage EC125 is much smaller (1977 bp).

FIG. 3.

Comparisons of warwickvirus EC125 and EC167. (A) Whole genome alignment is generated using clinker software: the minimum identity is set to 0.3; genes with similar functions are in same color. (B) Protein sequence alignment of the side tail fiber proteins Peg.29 of phage EC167 (URC25571.1) and Peg.33 of phage EC125 (URC25492.1). Differing amino acid residues are highlighted with red background.

Protein alignment showed that the side tail fibers are highly variable in the C-terminal known to interact with the O-antigen, whereas the N-terminals interacting with the baseplates are similar (Fig. 3B). Also, downstream of the side tail fiber phage EC125 encode three small hypothetical proteins (peg.30, peg.31, and peg.32) absent in EC167 (Fig. 3A). Detailed in silico analyses showed predicted functions related to the tail, including host recognition (Table 4).30–33 In summary, these results indicate that the three additional proteins in EC125 may influence or modulate side tail fiber binding to the host and, combined with the diverse side tail fibers, may explain the differences in host ranges.

Table 4.

In Silico Analysis of Hypothetical Genes Encoded by Phage EC125 in the Side Tail Fiber Protein Region

| Gene name (locus tag) | Size (bp) | Protein product (accession) | Size (aa) | Domains (InterPro) | Domains (HHpred) | Putative functions predicted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peg.30 | 156 | URC25489.1 | 51 | Coil aa: 19–46 |

Long tail fiber distal subunit Salmonella phage vB_SenMS16, aa: 2–45, probability: 97.09%, E-value: 0.0064, score: 30.09° | May be a distal subunit forming an adhesion tip30 |

| Peg.31 | 525 | URC25490.1 | 174 | N6-murein peptidoglycan lysine domain aa: 10–64 Intramolecular chaperone auto-processing domain aa: 70–174 |

Tail needle protein gp26 of phage P22, aa: 5–65, probability: 98.31%, E-value: 0.000012, score: 52.87 L-shaped tail fiber protein of phage T5, aa: 70–174, probability: 96.61%, E-value: 0.0061, score: 47.63 |

N-terminal may seal the portal vertex after genome packaging and possibly controlling the kinetics of DNA release as gp26 of phage P2231 C-terminal indicates a chaperone domain catalyzing trimerization32 |

| Peg.32 | 279 | URC25491.1 | 92 | None predicted | Mini-protein binder inhibitor of toxin Clostridium botulinum, aa: 4–27, Probability: 71.92%, E-value: 2.7, Score: 24.31 | May bind to a receptor binding domain of the phage33 |

The highly related strains belonging to STs4980 show variable sensitivity to phages

Although phages EC125 and EC167 efficiently killed most of the highly related strains belonging to ST4980, some strains in this cluster showed resistance toward the Warwickvirus phages (Fig. 2). To identify possible reasons for the different phage sensitivity, we performed genome analyses looking for differences in the phage receptor, putative phage defense systems, and the occurrence of prophages of these strains. Regarding the receptors, all strains in the cluster carry O88 O-antigen and a 100% identical FIR, a homologue of the previously identified receptor FhuA (Stephen Ahern personal communication, data not shown).

Thus, the strains carry identical receptors predicted to be recognized by these phages. Using the PADLOC online tool we identified several phage defense systems such as CRISPR-Cas with different targeting arrays, restriction-modification systems of type II and type III, and a few other systems (Supplementary Table S4). However, most of the identified defense systems for strains in the ST4980 cluster were similar. Next, PHASTER analysis identified prophage regions, resulting in a range of diverse prophage combinations in the strains (Supplementary Table S5). Thus, due to overlapping prophage regions in sensitive and resistant strains, their influence on sensitivity to warwickvirus EC125 and EC167 could not be determined. Overall, the phage resistance mechanisms or combination thereof together with genetic differences in the phages may result in the different host range profiles.

Discussion

The global emergence of resistance to β-lactams is of significant concern for public health as antimicrobials in this class are often used as last resort treatment of bacterial infections in humans.1 Livestock and meat are regarded as a potential reservoir of EBSL/AmpC E. coli, and strategies to prevent spread of these bacteria to humans are, therefore, needed. In this study, we determined the genetic diversity of 198 ESBL/AmpC E. coli to establish a collection representative of ESBL/AmpC genes, plasmids, and strains isolated from animal sources, and then used the collection to investigate the potential of bacteriophages as biocontrol.

Using in-depth whole genome and phylogenetic analyses, we demonstrated that our collection of 198 ESBL/AmpC E. coli is highly diverse and dominated by strains belonging to phylogroups B1, A and C known to contain commensals of animals as well as humans.18,34–36 In accordance with previous studies, strains of broiler origin mainly clustered in phylogroup A, pig strains mainly clustered in phylogroup C, whereas phylogroup B1 contained strains of mixed origin.34,35,37,38–40

Our collection is genetically diverse also in relation to STs, as the strains belonged to 65 STs, including some STs that are globally distributed in animals and humans such as ST88 and ST10, and some STs that were previously suggested to encompass potential zoonotic strains such as ST131, ST117, ST155, ST429, and ST354.25,30–32 A cgMLST analysis further confirmed the genetic diversity of our collection. Finally, the strains were distributed in the phylogenetic tree similar to the ECOR representative of the genetic diversity of E. coli as a species,12,41 further supporting that our collection is genetically diverse.

Our collection of ESBL/AmpC E. coli was also highly diverse with respect to β-lactamases and nine different genes were found to be carried by plasmids or integrated into the chromosome. Overproduction of the chromosomally encoded AmpC native β-lactamase is usually found in commensal strains belonging to phylogroup A.42 However, most of our strains carrying upregulated ampC belonged to phylogroups B1 and C, suggesting that also these strains are commensals. Using the WGS data, we successfully reconstructed 117 out of 122 plasmids carrying β-lactamase-encoding genes. Analysis of these plasmids showed that, as previously reported worldwide in E. coli from animal sources, the most common plasmid-borne β-lactamases were CTX-M-1 and CMY-2.1,14,15

Similar to other studies, CMY-2 was commonly found in strains isolated from broilers43,44–46 and to a lower extent in strains isolated from pigs.14,47 Several plasmid replicons have previously been associated with both blaCTX-M-1 and blaCMY-2 but, as in our collection, IncI1-1α and IncK plasmids are the most common carriers of the blaCTX-M-1 and blaCMY-2 as well as the larger IncC plasmids for blaCMY-2.45,48,49 Overall, the strain collection is representative of the diversity of ESBL/AmpC E. coli from broiler and pig sources and is useful for testing novel biocontrol solutions.

The global problem of antimicrobial resistance prompted us to look for alternative methods to combat ESBL/AmpC E. coli. Bacteriophages have been proposed for decolonizing animals for commensal ESBL/AmpC E. coli and their effect has been demonstrated both in vitro50,51 and in vivo.52,53 Using a collection of 15 phages previously isolated using the ECOR as isolation host,13 we found that only 44 out of 198 ESBL/AmpC E. coli strains were sensitive to phage infection, and most of the strains were only sensitive to one or two phages. Interestingly, Warwickvirus may use different proteins for host recognition, as phage EC125 encoded a unique small protein (Peg.300) with high similarity to the long tail fiber distal subunit of Salmonella phage vB_senMS16 forming the gp37-gp38 adhesion tip complex.30,33

Overall, the low efficacy against the ESBL/AmpC E. coli may be explained by the specificity of the phages that were not isolated on the target strains. Similarly, other studies showed varying efficacies of random E. coli-specific phages that were not specifically isolated to target ESBL/AmpC E. coli.54 Contrarily, isolation of phages for specific bacterial targets such as ESBL Klebsiella pneumoniae55 showed effective control of these bacteria. Thus, isolating phages specific for ESBL/AmpC E. coli may be essential for implementing phage biocontrol targeting these antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

In general, phage resistance mechanisms have never been investigated broadly in commensal ESBL/AmpC E. coli. Since we observed both phage susceptible and resistant strains among closely related ST4980 strains, the genomic data available to in silico look for differences between the strains. Although the O-antigen and FhuA receptor were identical in all 19 strains, FhuA may be masked by outer membrane components thus shielding access and preventing phage adsorption.56 In addition, O-antigen may be modified by prophage encoded enzymes maintaining the serotype, but still affecting the phage binding.56

Interestingly, the identified prophage regions were unique for each strain, but with no association between prophage presence and phage resistance. Finally, the few differences observed of encoded defense systems by susceptible and resistant strains may be due to sequencing gaps between contigs and a more detailed analyses of the genome sequences and plasmids are needed to point to the specific phage resistance mechanisms at play. Future work focusing on isolating novel phages to control ESBL/AmpC E. coli and reduce spreading of β-lactamase-encoding genes from the animal to human reservoir.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank The Danish Food Agency for providing the strain collection.

Authors' Contributions

Conceptualization by A.R.V., V.B., M.C.H.S., and L.B. Methodology by A.R.V., V.B., and M.C.H.S. Data curation by A.R.V., V.B., and L.B. Writing—original draft preparation by A.R.V. Writing—review and editing by V.B., L.B., M.C.H.S., and A.R.V. Visualization by A.R.V. Supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition by L.B., V.B, and M.C.H.S.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This project has received funding from Promilleafgiftsfonden, Denmark for A.R.V.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. European Food Safety Authority and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2019–2020. EFSA J 2022;20(3):7209; doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2022.7209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhao S, Wu Y, Dai Z, et al. Risk factors for antibiotic resistance and mortality in patients with bloodstream infection of Escherichia coli. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2022;41(5):713–721; doi: 10.1007/s10096-022-04423-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. Mortality and delay in effective therapy associated with extended-spectrum β-lactamase production in Enterobacteriaceae bacteraemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007;60(5):913–920; doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Becker E, Projahn M, Burow E, et al. Are there effective intervention measures in broiler production against the ESBL/AmpC producer Escherichia coli? Pathogens 2021;10(5):608; doi: 10.3390/pathogens10050608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dame-Korevaar A, Fischer EAJ, van der Goot J, et al. Early life supply of competitive exclusion products reduces colonization of extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in broilers. Poult Sci 2020;99(8):4052–4064; doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abedon ST. Kinetics of phage-mediated biocontrol of bacteria. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2009;6(7):807–815; doi: 10.1089/fpd.2008.0242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abuladze T, Li M, Menetrez MY, et al. Bacteriophages reduce experimental contamination of hard surfaces, tomato, spinach, broccoli, and ground beef by Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008;74(20):6230–6238; doi: 10.1128/AEM.01465-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wisuthiphaet N, Yang X, Young GM, et al. Rapid detection of Escherichia coli in beverages using genetically engineered bacteriophage T7. AMB Express 2019;9(1):55; doi: 10.1186/s13568-019-0776-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zalewska-Piątek B, Piątek R. Phage therapy as a novel strategy in the treatment of urinary tract infections caused by E. coli. Antibiotics 2020;9(6):304; doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9060304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sanchez BC, Heckmann ER, Green SI, et al. Development of phage cocktails to treat E. coli catheter-associated urinary tract infection and associated biofilms. Front Microbiol 2022;13:796132; doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.796132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bolocan AS, Callanan J, Forde A, et al. Phage therapy targeting Escherichia coli—A story with no end? FEMS Microbiol Lett 2016;363(22):fnw256; doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnw256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ochman H, Selander RK. Standard reference strains of Escherichia coli from natural populations. J Bacteriol 1984;157(2):690–693; doi: 10.1128/jb.157.2.690-693.1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vitt AR, Ahern SJ, Gambino M, et al. Genome sequences of 16 Escherichia coli bacteriophages isolated from wastewater, pond water, cow manure, and bird feces. Microbiol Resour Announc 2022;11(10):e0060822; doi: 10.1128/mra.00608-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Statens Serum Institute, National Veterinary Institute, and National Food Institute Denmark. DANMAP 2016: Use of Antimicrobial Agents and Occurrence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria from Food Animals, Food, and Humans in Denmark; 2016. Available from: https://www.danmap.org/reports/2016 [Last accessed: February 1, 2023].

- 15. Statens Serum Institute, National Veterinary Institute, and National Food Institute Denmark. DANMAP 2017: Use of Antimicrobial Agents and Occurrence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria from Food Animals, Food, and Humans in Denmark; 2017. Available from: https://www.danmap.org/reports/2017

- 16. Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 2012;19(5):455–477; doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clermont O, Condamine B, Dion S, et al. The E phylogroup of Escherichia coli is highly diverse and mimics the whole E. coli species population structure. Environ Microbiol 2021;23(11):7139–7151; doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl Environ Microb 2000;66(10):4555–4558; doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.10.4555-4558.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seemann T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014;30(14):2068–2069; doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 2021;49(W1):W293–W296; doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bortolaia V, Kaas RS, Ruppe E, et al. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020;75(12):3491–3500; doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alikhan NF, Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, et al. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): Simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genomics 2011;12:402; doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gencay YE, Gambino M, Prüssing TF, et al. The genera of bacteriophages and their receptors are the major determinants of host range. Environ Microbiol 2019;21(6):2095–2111; doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gilchrist CLM, Chooi YH. Clinker & clustermap.js: Automatic generation of gene cluster comparison figures. Bioinformatics 2021;37(16):2473–2475; doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hunter S, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, et al. InterPro: The integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37:D211–D215; doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Soding J, Biegert A, Lupas AN. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 2005;33:W244–W248; doi: 10.1093/nar/gki408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Payne LJ, Todeschini TC, Wu Y, et al. Identification and classification of antiviral defence systems in bacteria and archaea with PADLOC reveals new system types. Nucleic Acids Res 2021;49(19):10868–10878; doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arndt D, Grant JR, Marcu A, et al. PHASTER: A better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(W1):W16–W21; doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maffei E, Shaidullina A, Burkolter M, et al. Systematic exploration of Escherichia coli phage-host interactions with the BASEL phage collection. PLoS Biol 2021;19(11):e3001424; doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dunne M, Denyes JM, Arndt H, et al. Salmonella Phage S16 tail fiber adhesin features a rare polyglycine rich domain for host recognition. Structure 2018;26(12):1573–1582.e4; doi: 10.1016/j.str.2018.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bhardwaj A, Sankhala RS, Olia AS, et al. Structural plasticity of the protein plug that traps newly packaged genomes in podoviridae virions. J Biol Chem 2016;291(1):215–226; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.696260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Garcia-Doval C, Castón JR, Luque D, et al. Structure of the receptor-binding carboxy-terminal domain of the bacteriophage T5 L-shaped tail fibre with and without its intra-molecular chaperone. Viruses 2015;7(12):6424–6440; doi: 10.3390/v7122946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chevalier A, Silva DA, Rocklin GJ, et al. Massively parallel de novo protein design for targeted therapeutics. Nature 2017;550(7674):74–79; doi: 10.1038/nature23912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Coura FM, Diniz SDA, Silva MX, et al. Phylogenetic group determination of Escherichia coli isolated from animals samples. Sci World J 2015;2015:258424; doi: 10.1155/2015/258424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stoppe NdC, Silva JS, Carlos C, et al. Worldwide phylogenetic group patterns of Escherichia coli from commensal human and wastewater treatment plant isolates. Front Microbiol 2017;8:2512; doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Touchon M, Perrin A, De Sousa JAM, et al. Phylogenetic background and habitat drive the genetic diversification of Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet 2020;16(6):e1008866; doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Clermont O, Christenson JK, Denamur E, et al. The Clermont Escherichia coli phylo-typing method revisited: Improvement of specificity and detection of new phylo-groups. Environ Microbiol Rep 2013;5(1):58–65; doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carlos C, Pires MM, Stoppe NC, et al. Escherichia coli phylogenetic group determination and its application in the identification of the major animal source of fecal contamination. BMC Microbiol 2010;10:161; doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Day MJ, Rodríguez I, van Essen-Zandbergen A, et al. Diversity of STs, plasmids and ESBL genes among Escherichia coli from humans, animals and food in Germany, the Netherlands and the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71(5):1178–1182; doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Papouskova A, Papouskova A, Masarikova M, et al. Genomic analysis of Escherichia coli strains isolated from diseased chicken in the Czech Republic. BMC Vet Res 2020;16(1):189; doi: 10.1186/s12917-020-02407-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tenaillon O, Skurnik D, Picard B, et al. The population genetics of commensal Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010;8(3):207–217; doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Corvec S, Prodhomme A, Giraudeau C, et al. Most Escherichia coli strains overproducing chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase belong to phylogenetic group A. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007;60(4):872–876; doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Athanasakopoulou Z, Tsilipounidaki K, Sofia M, et al. Poultry and wild birds as a reservoir of CMY-2 producing Escherichia coli: The first large-scale study in Greece. Antibiotics 2021;10(3):235; doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10030235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. de Been M, Lanza VF, de Toro M, et al. Dissemination of cephalosporin resistance genes between Escherichia coli strains from farm animals and humans by specific plasmid lineages. PLoS Genet 2014;10(12):e1004776; doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hansen KH, Bortolaia V, Nielsen CA, et al. Host-specific patterns of genetic diversity among IncI1-Iγ and IncK plasmids encoding CMY-2 β-lactamase in Escherichia coli isolates from humans, poultry meat, poultry, and dogs in Denmark. Appl Environ Microbiol 2016;82(15):4705–4714; doi: 10.1128/AEM.00495-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Berg ES, Wester AL, Ahrenfeldt J, et al. Norwegian patients and retail chicken meat share cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli and IncK/blaCMY-2 resistance plasmids. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017;23(6):407.e9–407.e15; doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Agersø Y, Aarestrup FM, Pedersen K, et al. Prevalence of extended-spectrum cephalosporinase (ESC)-producing Escherichia coli in Danish slaughter pigs and retail meat identified by selective enrichment and association with cephalosporin usage. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67(3):582–588; doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Seiffert SN, Carattoli A, Schwendener S, et al. Plasmids carrying blaCMY -2/4 in Escherichia coli from poultry, poultry meat, and humans belong to a novel IncK subgroup designated IncK2. Front Microbiol 2017;8:407; doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shirakawa T, Sekizuka T, Kuroda M, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of third-generation- cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli harboring the blaCMY-2-positive IncI1 group, IncB/O/K/Z, and IncC plasmids isolated from healthy broilers in Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020;64(7):e02385; doi: 10.1128/AAC.02385-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Skaradzińska A, Śliwka P, Kuźmińska-Bajor M, et al. The efficacy of isolated bacteriophages from pig farms against ESBL/AmpC-producing Escherichia coli from pig and Turkey farms. Front Microbiol 2017;8:530; doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bernasconi OJ, Campos-Madueno EI, Donà V, et al. Investigating the use of bacteriophages as a new decolonization strategy for intestinal carriage of CTX-M-15-producing ST131 Escherichia coli: An in vitro continuous culture system model. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2020;22:664–671; doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Erol HB, Kaskatepe B, Ozturk S, et al. The comparison of lytic activity of isolated phage and commercial Intesti bacteriophage on ESBL producer E. coli and determination of Ec_P6 phage efficacy with in vivo Galleria mellonella larvae model. Microb Pathog 2022;167:105563; doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Green SI, Kaelber JT, Ma L, et al. Bacteriophages from ExPEC reservoirs kill pandemic multidrug-resistant strains of clonal group ST131 in animal models of bacteremia. Sci Rep 2017;7:46151; doi: 10.1038/srep46151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mirzaei MK, Nilsson AS. Isolation of phages for phage therapy: A comparison of spot tests and efficiency of plating analyses for determination of host range and efficacy. PLoS One 2015;10(3):e0118557; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Venturini C, Ben Zakour NL, Bowring B, et al. Fine capsule variation affects bacteriophage susceptibility in Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258. FASEB J 2020;34(8):10801–10817; doi: 10.1096/fj.201902735R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Labrie SJ, Samson JE, Moineau S. Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010;8(5):317–327; doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.