Key summary points

Aim

To comparatively assess the clinical profiles of older patients treated with trazodone or other antidepressants in a large dataset from the GeroCovid Observational multiscope and multisetting study.

Findings

10.8% out of 3396 persons included used trazodone and the 8.5% other antidepressants; the use of trazodone was highly prevalent in functionally dependent and comorbid older adults admitted to long-term care facilities or living at home. Conditions associated with trazodone use included depression, dementia and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Message

The present data suggest an off-label use of trazodone as a possible therapeutic option in the challenging field of behavioral and psychological disturbances in older adults with dementia.

Keywords: Depression; Dementia; Trazodone; BPSD, Profile, Clinical characteristics

Abstract

Background and objectives

Depression is highly prevalent in older adults, especially in those with dementia. Trazodone, an antidepressant, has shown to be effective in older patients with moderate anxiolytic and hypnotic activity; and a common off-label use is rising for managing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). The aim of the study is to comparatively assess the clinical profiles of older patients treated with trazodone or other antidepressants.

Methods

This cross-sectional study involved adults aged ≥ 60 years at risk of or affected with COVID-19 enrolled in the GeroCovid Observational study from acute wards, geriatric and dementia-specific outpatient clinics, as well as long-term care facilities (LTCF). Participants were grouped according to the use of trazodone, other antidepressants, or no antidepressant use.

Results

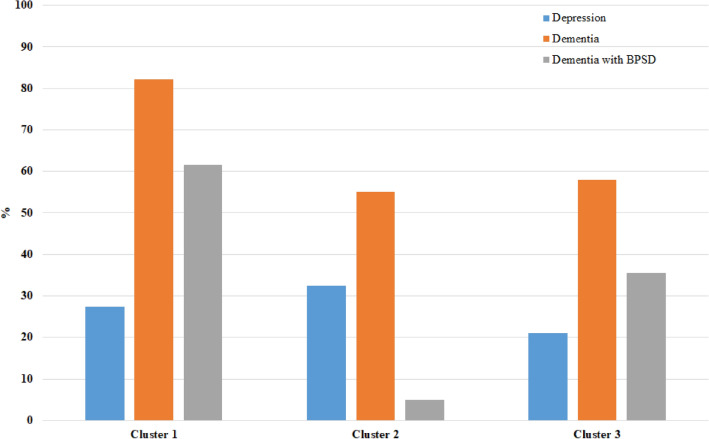

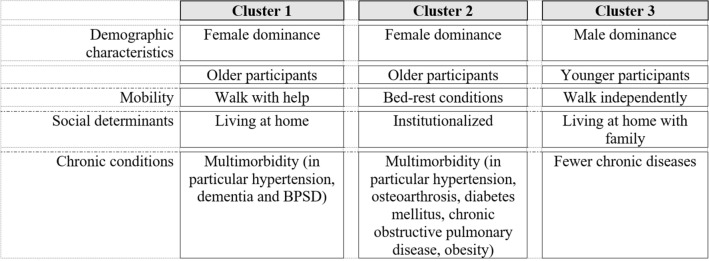

Of the 3396 study participants (mean age 80.6 ± 9.1 years; 57.1% females), 10.8% used trazodone and 8.5% others antidepressants. Individuals treated with trazodone were older, more functionally dependent, and had a higher prevalence of dementia and BPSD than those using other antidepressants or no antidepressant use. Logistic regression analyses found that the presence of BPSD was associated with trazodone use (odds ratio (OR) 28.4, 95% confidence interval (CI) 18-44.7 for the outcome trazodone vs no antidepressants use, among participants without depression; OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.05-4.49 for the outcome trazodone vs no antidepressants use, among participants with depression). A cluster analysis of trazodone use identified three clusters: cluster 1 included mainly women, living at home with assistance, multimorbidity, dementia, BPSD, and depression; cluster 2 included mainly institutionalized women, with disabilities, depression, and dementia; cluster 3 included mostly men, often living at home unassisted, with better mobility performance, fewer chronic diseases, dementia, BPSD, and depression.

Discussion

The use of trazodone was highly prevalent in functionally dependent and comorbid older adults admitted to LTCF or living at home. Clinical conditions associated with its prescription included depression as well as BPSD.

Introduction

Depression is a highly prevalent, yet commonly underdiagnosed condition in older patients across all settings of care [1–3]. A wide range of depressive traits, from mild to major depression symptoms, can be found in advanced age associated with numerous psychiatric and non-psychiatric conditions [4]. Clinical expression of depression in old age is highly variable. Approximately, one-third of older patients with dementia show depressive symptoms associated with other neuropsychiatric symptoms, while those with depression (without dementia) more frequently have atypical behavioral disorders [2, 5, 6], such as sleep troubles, anorexia, agitation, and confusion [7], compared to younger adults. Moreover, anxiety often coexists in comorbid older persons with depression and prevalence estimates ranging from 23 to 48% [8]. Due to this clinical heterogeneity, the choice of an antidepressant treatment is often guided by the expected activity of the drug on coexistent neuropsychiatric symptoms. For this reason, real-life prescription studies of different antidepressant drugs according to clinical profiles may shed light on the available literature [9].

Among various antidepressants, trazodone qualifies as an eclectic drug showing an effective antidepressant action as well as moderate anxiolytic and hypnotic activities in older patients [10, 11]. Due to this sedative action, trazodone is often used in older people with dementia or delirium to manage agitation, insomnia, and other behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) [12, 13]. However, available literature on the prescribing patterns of trazodone in different care settings is lacking. Iaboni et al. [14] described an increased use of trazodone and quetiapine over years, paralleling decreased benzodiazepine prescription in older adults with dementia in Canada, in both long-term care facilities (LTCF) and in the community.

In this context, the GeroCovid Observational initiative offered a unique opportunity of exploring the use of trazodone in older individuals from an epidemiological point of view. This observational study was launched by the Italian Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics (SIGG) to assess the direct and indirect impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health of older people in different care settings, including acute wards, dementia and geriatric outpatient clinics, home services, and LTCF. In addition to COVID-19-related information, the initiative also included data collection related to chronic diseases and treatments, which allowed for secondary analyses exploring the current management of diverse common conditions.

In this work, we aimed to characterize the prescription patterns of trazodone in comparison with other antidepressants in older people across different settings of care. In particular, we aimed at investigating the versatile use of trazodone in older persons with dementia and BPSD across diverse clinical settings.

Methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional study using data from GeroCovid Observational, an initiative involving adults aged ≥ 60 years evaluated during the COVID-19 pandemic. GeroCovid Observational is a multicenter, multiscope, and multisetting study designed by the Italian Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics and is structured into the following research settings (details can be found in previous publications [15, 16]: GeroCovid acute care wards (including patients hospitalized for SARS-CoV-2 infection), GeroCovid home and outpatient care (including individuals accessing geriatric outpatient or home care services), GeroCovid dementia–drug monitoring and GeroCovid dementia–psychological health (including outpatients with cognitive impairment), GeroCovid long-term care facilities (LTCF) (including residents with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection), and GeroCovid outcomes (including individuals followed up after a COVID-19-related hospitalization). The study was conducted following the STROBE guidelines. Data registration was performed using a dedicated electronic register designed by Bluecompanion (UK, France) to collect all clinical data from every investigational site across Italy.

The GeroCovid Observational study protocol was approved by the Campus Bio-Medico University Ethical Committee in April 2020. All participating investigational sites further submitted relevant sub-protocols to their competent local ethical committee and institutional review boards, as applicable according to Italian regulations. All investigators accepted to work according to the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) (ICH E6-R2). Written or dematerialized informed consent was obtained from each participant. Alternatively, a written declaration was kept on file by the local investigator, which responded to applicable derogations during the pandemic.

Data collection

Data collection for this study included: demographic characteristics (age, sex), lifestyle (smoking habits, alcohol consumption), mobility (independent walking, walking with a cane or walker, bed-rest condition), social determinants (care setting: nursing home, in-patient, outpatients, home-based; household: lives at home alone and is autonomous, lives at home regularly assisted, lives at home alone with informal caregiver, lives at home with family and is autonomous, lives in a nursing home; social distancing impact: major impact, no or moderate impact), chronic diseases from medical records coded according to Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) [17] (hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obesity, depression, BPSD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), dementia, and type of dementia), and functional status with activity of daily livings (ADL) by Katz index and instrumental activity daily livings (IADL) by Lawton and Brody index. Based on the list of drugs chronically used by the study participants, coded according to the ATC, we identified participants treated with trazodone (TRAZ), other antidepressants (AnDep), or no antidepressant treatment (No AnDep). All participants with a sars-cov-2 infection (diagnosed with a real-time PCR) were included in the inpatient care setting, while in the other care settings only 26 participants were tested and resulted negative.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the study participants are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD), or median and interquartile range [25th–75th percentile] for quantitative measures, or counts and percentages for categorical variables. Normality of the distributions was evaluated considering the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. No imputation of missing values was performed.

The study participants were grouped according to the use of antidepressants (TRAZ, AnDep, No AnDep) and compared according to sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender), lifestyle (smoking habits, alcohol habits, physical activity), mobility, social determinants (care setting, household, and social distancing impact), chronic conditions, functional status, and SARS-CoV-2 infection, using the Chi-squared or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and generalized linear model testing for homoscedasticity through the Levene’s test for quantitative variables. Post hoc analyses with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons were applied.

A multinominal logistic regression model with outcome groups defined according to antidepressant drugs, TRAZ, AnDep, or No AnDep use, was defined with the following independent variables: age, gender, mobility, household, chronic conditions (hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, stroke, diabetes mellitus, osteoarthrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal failure, obesity, depression, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and behavioral disorders)a. A block entering of independent variables was applied and results are presented as adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Multiplicative interactions between the variables were also tested in the logistic models.

A cluster analysis based on k-means method was used to classify participants using TRAZ into clusters of coexisting characteristics. K-means algorithm divides the n sample into k clusters so that internal similarity of the clusters is high and the external similarity of the clusters is low. The optimal number of clusters was determined by comparing pseudo-F statistic and cubic clustering criterion for models with different number of clusters. The characteristics of participants in different clusters were compared using Chi-squared, Fisher exact tests or generalized linear model, as appropriate. All statistical tests were two tailed and statistical significance was assumed for p value < 0.05. The analyses were performed using SAS, V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Out of the 3396 cases included in the analysis, 367 (10.8%) were using TRAZ and 288 (8.5%) AnDep. As shown in Table 1, the mean age was significantly higher in the TRAZ (84.3 ± 6.6) and AnDep (82.5 ± 7.2) groups than the No AnDep group (80.0 ± 9.4) (F = 44.5, df = 2, p < 0.0001). Over 60% of women were using antidepressants. Mobility deficits were approximately 50% in the entire study group (n = 3170). Patients using TRAZ had significantly lower levels of independent mobility than those taking AnDep or No AnDep treatments (32%, 36%, and 55% can walk independently, respectively) (χ2 = 101.5, df = 6, p < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Demographic, lifestyle, and social characteristics of the GeroCovid population according to TRAZ, AnDep, and No AnDep groups

| All (n = 3396) | TRAZ (n = 367) | AnDep (n = 288) | No AnDep (n = 2741) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 80.6 ± 9.1 | 84.3 ± 6.6 | 82.5 ± 7.2 | 80.0 ± 9.4 | < 0.0001abc |

| Gender (Female) | 1938 (57.1) | 251 (68.4) | 191 (66.3) | 1496 (54.6) | < 0.0001ab |

| Lifestyle | |||||

| Smoking habits (available for n = 1830) | 0.0077a | ||||

| Current smoker | 86 (4.7) | 10 (4.9) | 8 (4.7) | 68 (4.7) | |

| Former smoker | 371 (20.3) | 26 (12.8) | 24 (14.2) | 321 (22.0) | |

| Never smoker | 1373 (75.0) | 168 (82.4) | 137 (81.1) | 1068 (73.3) | |

| Alcohol consumption (available for n = 1707), yes | 158 (9.3) | 9 (3.8) | 6 (3.6) | 143 (11.0) | < 0.0001ab |

| Mobility (available for n = 3170) | < 0.0001ab | ||||

| Walks independently | 1615 (51.0) | 112 (32.4) | 99 (36.4) | 1404 (55.0) | |

| Walks with help (cane or walker) | 613 (19.3) | 95 (27.4) | 79 (29.0) | 439 (17.2) | |

| Wheelchair (autonomous or pushed) | 334 (10.5) | 57 (16.5) | 43 (15.8) | 234 (9.2) | |

| Bed-rest condition | 608 (19.2) | 82 (23.7) | 51 (18.8) | 475 (18.6) | |

| Social determinants | |||||

| Care setting (available for n = 2974) | < 0.0001ab | ||||

| Outpatients | 918 (30.9) | 114 (33.8) | 60 (22.6) | 744 (31.4) | |

| Nursing home | 559 (18.8) | 72 (21.4) | 63 (23.7) | 424 (17.9) | |

| Inpatient | 1113 (37.4) | 89 (26.4) | 91 (34.2) | 933 (39.3) | |

| Home based | 384 (12.9) | 62 (18.4) | 52 (19.6) | 270 (11.4) | |

| Household (available for n = 2763) | < 0.0001abc | ||||

| Lives at home alone, autonomous | 160 (5.8) | 11 (3.2) | 11 (4.3) | 138 (6.3) | |

| Lives at home alone, regularly assisted | 195 (7.1) | 25 (7.4) | 29 (11.3) | 141 (6.5) | |

| Lives at home alone, informal caregiver | 528 (19.1) | 125 (37.0) | 67 (26.3) | 336 (15.5) | |

| Lives at home with family, autonomous | 1057 (38.2) | 52 (15.4) | 66 (25.9) | 939 (43.3) | |

| Lives in a nursing home | 823 (29.8) | 125 (37.0) | 82 (32.2) | 616 (28.4) | |

| Social distancing impact (available for n = 1477) | 0.0030a | ||||

| Major impact | 543 (36.8) | 64 (27.7) | 51 (33.3) | 428 (39.2) | |

| No or moderate impact | 934 (63.2) | 167 (72.3) | 102 (66.7) | 665 (60.8) |

Numbers are mean ± SD, or count (%), as appropriate

TRAZ (participants on trazodone); AnDep (participants taking other antidepressants; No AnDep (participants not taking antidepressants); SD (standard deviation)

Overall p value is calculated among the three groups of antidepressant users/not users

aSignificant post hoc difference for TRAZ vs NoAnDep

bSignificant post hoc difference for AnDep vs NoAnDep

cSignificant post hoc difference for TRAZ vs AnDep

In the entire study population, we found that the prescription of TRAZ was higher in outpatient settings (mainly outpatients followed for cognitive deficits), while any AnDep use was higher in inpatients (χ2 = 47.9, df = 6, p < 0.0001). In the TRAZ group, there was a significantly greater need for patient assistance either at home from informal caregivers or in nursing homes (χ2 = 170.4, df = 8, p < 0.0001).

The prevalence of chronic diseases, the use of antipsychotics, and TRAZ dosages are reported in Table 2. A recorded diagnosis of depression was present in 54% of those using AnDep, in 28% of those using TRAZ, and in 12% of those not treated (No AnDep). (χ2 = 344.7, df = 2, p < 0.0001). More than half of the participants suffering from depression (55%) were not undergoing any pharmacological treatment for depression. In the TRAZ and AnDep groups, approximately 70% had three or more chronic diseases vs. 40% in the No AnDep group (χ2 = 177.1, df = 2, p < 0.0001). In particular, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and osteoarthritis were more prevalent in the TRAZ and AnDep groups compared to the No AnDep group (for hypertension, 72.2% and 72.9% vs 58%, respectively, p < 0.0001; for cardiovascular diseases, 48.8% and 47.6% vs 41.2%, p = 0.0048; for osteoarthrosis, 36.5% and 35.5% vs 22.3%, p < 0.0001). Dementia reached 28% prevalence with a higher prevalence in the TRAZ group (67%) than the AnDep (49%) and the No AnDep group (21.6%) (χ2 = 384.3, df = 2, p < 0.0001). Similarly, BPSD and antipsychotic treatments were more prevalent in the TRAZ group: BPSD were present in 34.6% of the individuals in the TRAZ group, 13.9% in the AnDep group, and 3.8% in the No AnDep group (p < 0.0001); antipsychotic treatments were used in 44.7% of individuals in the TRAZ group, 30.9% in the AnDep group, and 10.7% in the No AnDep group (p < 0.0001). The daily dosage of TRAZ was lower than 100 mg in most of the participants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Health-related, functional, and frailty characteristics of the GeroCovid population according to the TRAZ, AnDep, and No AnDep groups

| All (n = 3396) | TRAZ (n = 367) | AnDep (n = 288) | No AnDep (n = 2741) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic conditions | |||||

| Hypertension (available for n = 3236) | 1972 (60.9) | 262 (72.2) | 210 (72.9) | 1500 (58.0) | < 0.0001ab |

| Cardiovascular diseases* (available for n = 3219) | 1371 (42.6) | 177 (48.8) | 136 (47.6) | 1058 (41.2) | 0.0048a |

| Stroke (available for n = 3212) | 305 (9.5) | 44 (12.3) | 35 (12.2) | 226 (8.8) | 0.0285 |

| Diabetes mellitus (available for n = 3217) | 684 (21.3) | 76 (21.1) | 61 (21.3) | 547 (21.3) | 0.9970 |

| Osteoarthrosis (available for n = 3213) | 806 (25.1) | 131 (36.5) | 102 (35.5) | 573 (22.3) | < 0.0001ab |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (available for n = 3211) | 426 (13.3) | 52 (14.5) | 36 (12.5) | 338 (13.2) | 0.7367 |

| Chronic renal failure (available for n = 3213) | 384 (12.0) | 49 (13.7) | 40 (13.9) | 295 (11.5) | 0.2691 |

| Obesity (available for n = 3224) | 254 (7.9) | 25 (7.0) | 24 (8.4) | 205 (8.0) | 0.7689 |

| Depression (available for n = 3213) | 564 (17.6) | 101 (27.9) | 155 (54.0) | 308 (12.0) | < 0.0001abc |

| Mild cognitive impairment | 140 (4.1) | 15 (4.1) | 10 (3.5) | 115 (4.2) | 0.8410 |

| Dementia | 978 (28.8) | 245 (66.8) | 141 (49.0) | 592 (21.6) | < 0.0001abc |

| If dementia, specify | |||||

| Alzheimer’s disease | 402 (11.8) | 119 (32.4) | 62 (21.5) | 221 (8.1) | < 0.0001abc |

| Vascular dementia | 151 (4.5) | 33 (9.0) | 14 (4.9) | 104 (3.8) | < 0.0001a |

| Dementia with Lewy bodies | 18 (0.5) | 6 (1.6) | 3 (1.0) | 9 (0.3) | 0.0039a |

| Frontotemporal dementia | 10 (0.3) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.7) | 5 (0.2) | 0.0311 |

| Mixed dementia | 105 (3.1) | 24 (6.5) | 19 (6.6) | 62 (2.3) | < 0.0001ab |

| Other | 253 (7.5) | 46 (12.5) | 40 (13.9) | 167 (6.1) | < 0.0001ab |

| Dementia due to Parkinson’s disease | 11 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (0.3) | 0.5098 |

| Dementia due to other medical condition | 10 (0.3) | 4 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.2) | 0.0389 |

| Dementia with BPSD | 270 (8.0) | 127 (34.6) | 40 (13.9) | 103 (3.8) | < 0.0001abc |

| Comorbidities**, 3+ | 1546 (45.5) | 245 (66.8) | 205 (71.2) | 1096 (40.0) | < 0.0001ab |

| Functional status | |||||

| Activities of daily living, median (Q1, Q3) (available for n = 1668) | 4 (1, 6) | 2 (1, 4) | 3 (1, 5) | 4 (1, 6) | < 0.0001abc |

| Instrumental activities of daily living, median (Q1, Q3) (available for n = 1444) | 1 (0, 5) | 0 (0, 1) | 1 (0, 4) | 2 (0, 6) | < 0.0001abc |

| Antipsychotic drugs use, n (%) | 545 (16.1) | 164 (44.7) | 89 (30.9) | 292 (10.7) | < 0.0001abc |

| Trazodone dose, n (%) | – | – | |||

| > 100 mg/day | 19 (7.8) | ||||

| ≤ 100 mg/day | 226 (92.2) |

Numbers are mean ± SD, median (Q1, Q3) or count (%), as appropriate

TRAZ, participants on trazodone; AnDep, participants assuming other antidepressants; No AnDep, participants not taking antidepressant; SD, standard deviation; BPSD, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia

Overall p value is calculated among the three groups of antidepressant users/not users

*Includes atrial fibrillation, peripheral arteriopathy, heart failure, and cardiomyopathy

**Total number of comorbidities, considering hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, stroke, diabetes mellitus, osteoarthrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal failure, obesity, depression, behavior disorders, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia

aSignificant post hoc difference for NoAnDep vs TRAZ

bSignificant post hoc difference for NoAnDep vs AnDep

cSignificant post hoc difference for TRAZ vs AnDep

Clinical variables associated with the use of TRAZ or AnDep in multinomial models are reported in Table 3. Motor disability, depression, and dementia (with or without the presence of BPSD) were associated with an increased likelihood of using TRAZ or AnDep compared to not being treated. The interaction between depression and dementia (with or without BPSD) was statistically significant, meaning that the relationship between dementia and the outcome (use of TRAZ or AnDep or NoAnDep) depends on the presence of depression (χ2 = 23.7, df = 4, p < 0.0001). In fact, the association of dementia (and especially of dementia with BPSD) with the outcome was stronger in participants without depression compared to those with depression. In particular, in participants without depression, the association between TRAZ and dementia with BPSD (OR 28.4, 95% CI 18.8, 44.7; Wald χ2 = 209.1, df = 1, p < 0.0001) was significant, as well as the association between AnDep and dementia with BPSD (OR 5.68, 95% CI 2.94, 10.9; Wald χ2 = 26.7, df = 1, p < 0.0001). Among individuals with depression, an independent association between TRAZ and dementia with or without BPSD was still present, while no association was observed between AnDep and dementia. Stratifying analyses by care setting (Supplementary Table S1), results were substantially confirmed in home-based, nursing home, and outpatient participants, while a significant association between TRAZ and dementia without BPSD and between AnDep and dementia with BPSD among participants without depression was found for inpatients.

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression model with outcome “Trazodone”, “Other antidepressants” or “No antidepressants” use in the GeroCovid population

| TRAZ vs no AnDep | AnDep vs no AnDep | TRAZ vs AnDep | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age, years | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 0.4027 | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 0.8798 | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 | 0.4446 |

| Gender, female vs male | 1.15 | 0.85–1.55 | 0.3694 | 1.05 | 0.76–1.45 | 0.7689 | 1.09 | 0.73–1.63 | 0.6602 |

| Mobility vs walks independently | |||||||||

| Walks with help | 1.28 | 0.87–1.89 | 0.2047 | 1.45 | 0.96–2.17 | 0.0749 | 0.89 | 0.54–1.46 | 0.6391 |

| Wheelchair | 2.00 | 1.23–3.25 | 0.0055 | 1.95 | 1.16–3.27 | 0.0120 | 1.03 | 0.55–1.91 | 0.9356 |

| Bed-rest condition | 1.34 | 0.85–2.13 | 0.2096 | 1.31 | 0.79–2.16 | 0.2969 | 1.03 | 0.56–1.89 | 0.9286 |

| Household vs lives at home alone, autonomous | |||||||||

| Lives at home alone, regularly assisted | 1.12 | 0.48–2.61 | 0.7924 | 1.36 | 0.60–3.08 | 0.4678 | 0.83 | 0.28–2.44 | 0.7304 |

| Lives at home alone, informal caregiver | 1.67 | 0.78–3.55 | 0.1874 | 1.14 | 0.53–2.45 | 0.7447 | 1.47 | 0.54–3.97 | 0.4520 |

| Lives at home with family, autonomous | 0.90 | 0.43–1.91 | 0.7901 | 0.96 | 0.46–2.00 | 0.9043 | 0.95 | 0.35–2.53 | 0.9101 |

| Lives in a nursing home | 1.67 | 0.77–3.63 | 0.1954 | 1.00 | 0.46–2.18 | 0.9901 | 1.68 | 0.61–4.66 | 0.3198 |

| Hypertension | 1.20 | 0.89–1.62 | 0.2248 | 1.39 | 1.00–1.93 | 0.0474 | 0.87 | 0.58–1.29 | 0.4773 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 1.16 | 0.88–1.53 | 0.3009 | 1.16 | 0.86–1.57 | 0.3221 | 1.00 | 0.69–1.43 | 0.9814 |

| Stroke | 1.19 | 0.78–1.80 | 0.4213 | 1.16 | 0.74–1.82 | 0.5138 | 1.02 | 0.60–1.75 | 0.9343 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.85 | 0.61–1.18 | 0.3332 | 0.90 | 0.64–1.28 | 0.5707 | 0.94 | 0.61–1.45 | 0.7733 |

| Osteoarthrosis | 1.14 | 0.85–1.53 | 0.3832 | 1.07 | 0.78–1.47 | 0.6837 | 1.07 | 0.73–1.56 | 0.7423 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.12 | 0.76–1.65 | 0.5792 | 0.89 | 0.58–1.36 | 0.5877 | 1.26 | 0.75–2.11 | 0.3880 |

| Chronic renal failure | 0.78 | 0.52–1.16 | 0.2183 | 0.99 | 0.65–1.50 | 0.9625 | 0.79 | 0.47–1.31 | 0.3594 |

| Obesity | 0.86 | 0.51–1.47 | 0.5862 | 1.12 | 0.67–1.86 | 0.6681 | 0.77 | 0.40–1.49 | 0.4401 |

| Mild cognitive impairment | 1.67 | 0.87–3.20 | 0.1207 | 0.96 | 0.45–2.03 | 0.9094 | 1.75 | 0.70–4.36 | 0.2324 |

| Study participants with depression | |||||||||

| Dementia with no BPSD vs no dementia | 2.29 | 1.26–4.16 | 0.0066 | 1.53 | 0.92–2.56 | 0.1037 | 1.50 | 0.78–2.89 | 0.2305 |

| Dementia with BPSD vs no dementia | 4.97 | 2.52–9.80 | < 0.0001 | 1.96 | 0.99–3.78 | 0.0560 | 2.54 | 1.22–5.29 | 0.0128 |

| Dementia with BPSD vs dementia with no BPSD | 2.17 | 1.05–4.49 | 0.0365 | 1.28 | 0.63–2.60 | 0.4988 | 1.70 | 0.78–3.68 | 0.1797 |

| Study participants without depression | |||||||||

| Dementia with no BPSD vs no dementia | 3.87 | 2.66–5.62 | < 0.0001 | 3.25 | 2.12–4.98 | < 0.0001 | 1.19 | 0.70–2.03 | 0.5254 |

| Dementia with BPSD vs no dementia | 28.4 | 18.0–44.7 | < 0.0001 | 5.68 | 2.94–10.9 | < 0.0001 | 5.00 | 2.48–10.1 | < 0.0001 |

| Dementia with BPSD vs dementia with no BPSD | 7.34 | 4.72–11.4 | < 0.0001 | 1.75 | 0.90–3.38 | 0.0974 | 4.20 | 2.12–8.32 | < 0.0001 |

Block entering of independent variables

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; TRAZ, participants on trazodone; AnDep, participants taking other antidepressants; No AnDep, participants not taking antidepressants; BPSD, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia

The cluster analysis according to TRAZ use characterized three clusters (Supplementary Table 1; Figs. 1, 2). Cluster 1 included mainly older women living at home requiring assistance due to functional limitations (more than 60% moved with help or in a wheelchair), multimorbidity (73%), dementia (82%), and BPSD (62% among those with dementia); one out of four had a diagnosis of depression. Cluster 2 was mainly composed of institutionalized women with disabilities and chronic diseases (in particular, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, COPD, and obesity). Approximately 30% had depression, while 55% had dementia, but only 5% among those with dementia had BPSD. Cluster 3 included younger participants, mostly men, often living at home unassisted, with better mobility performance and fewer chronic diseases; however, 58% had dementia and 36% BPSD, while only 21% had depression.

Fig. 1.

Depression, dementia, and BPSD prevalence by clusters identified among TRAZ users

Fig. 2.

Summary of participants’ characteristics among clusters

In all clusters, the dose of TRAZ was mainly < 100 mg/day and over 40% were using antipsychotics with a slightly higher frequency in cluster 1.

Discussion

In this sample of older participants with, or at risk of, COVID-19, approximately one out of five persons (18.5%) over 60 years of age received an antidepressant, with trazodone being the most prescribed drug (10.8% vs. 8.5% other antidepressants). We also found that the use of trazodone was associated with clinical conditions other than depression. The frequency of antidepressant use in our sample was similar to the available literature [18], although lower in comparison with data from LTCF studies [19, 20]. Moreover, our study showed a higher use of trazodone than those reported in other studies [13, 21]. This may be explained by the fact that our study included multiple care settings with diverse clinical characteristics. The GeroCovid study includes a large data collection from diverse care settings, which extends clinical knowledge from previous population-based cohort or LTCF studies [13, 21].

We found that participants using trazodone were more likely to be functionally dependent and to have several comorbidities and a higher prevalence of cardiovascular diseases or osteoarthritis. Furthermore, 28% of the participants in the TRAZ group had a formal diagnosis of depression (vs. 54% among participants treated with other antidepressants and 12% among participants not receiving antidepressants), while two-thirds of TRAZ group participants suffered from dementia (vs. 49% of those treated with other antidepressants and 22% of those not receiving antidepressant treatment), and one-third of TRAZ group had BPSD (vs. 14% in the AnDep and 4% in the No AnDep groups). Analyses underlined that independent of a depression diagnosis, BPSD was associated with an increased use of trazodone compared to other antidepressants. The association was the strongest among participants without depression, but still statistically significant in those with depression. Indeed, this antidepressant has been shown to be used off-label for insomnia [22, 23] and hold anxiolytic [24, 25] effects, as well as control aggression [26] and other BPSD [27, 28].

The cluster analysis provides some further insights regarding the prescription of trazodone. In particular, clusters 1 and 3 included older community-dwelling adults with a high prevalence of BPSD. However, cluster 3 included mainly those with better general clinical conditions, even if affected by dementia and BPSD and often not needing direct assistance at home. Furthermore, the dosage of trazodone in clusters 1 and cluster 3 was lower than 75 mg/day, a dosage which has been reported for treating BPSD, such as wandering, agitation, delusions [29], and treating psychotic symptoms in depression and dementia [30]. Interestingly, antipsychotics were used in 40–50% of individuals using trazodone. Trazodone has also been reported to be effective in neuroleptic-induced akathisia [31].

Cluster 2 identified institutionalized individuals and inpatients with disabilities and chronic pathologies, among which about one-third had depression and less than half dementia, but very few had BPSD.

Regardless of diagnosed dementia, antidepressants other than trazodone were prescribed in participants with depression. On the other hand, in those with dementia, there was a vast use of antidepressants regardless of depression or BPSD [32]. Dementia is often accompanied by affective disorders, including anxiety and emotional lability, which are widely treated with antidepressants even if clinical evidence regarding their efficacy remains conflicting [33]. Moreover, antidepressants such as sertraline and citalopram have also shown to reduce agitation and psychosis in dementia, which may partially explain their increased use among non-depressed participants with dementia [33]. Nevertheless, cardiovascular side effects might limit their off-label use in frail older individuals without depression. Psychiatric reactions to SSRI use, including anxiety, irritability and, more rarely, mania and psychosis, may also limit their use in older patients [34].

Another interesting finding from our study was that more than half of the participants suffering from depression were not treated with any antidepressant agent, which confirms other reports [35, 36], suggesting that the stigma of using psychiatric drugs in old people has not yet been overcome [37–39].

The strength of the present study relies on the large sample size and on the extensive clinical assessment in a real-life older population from different care settings.

The main limitations are represented by the cross-sectional analysis, the lack of information regarding the purpose of prescription, duration, effectiveness, as well as the tolerability of the prescribed drugs. Diagnoses were collected by medical records and we did not collect data regarding pain.

In conclusion, this study underlined a high prevalence of trazodone prescription in a large, multiset sample of older Italian participants with, or at risk of, COVID-19. The present data suggest an off-label use of this drug at doses ≤ 100 mg/day for the treatment of dementia with BPSD with or without depression. Further studies assessing reason of prescription, effectiveness and tolerability of different antidepressants in frail older adults, with and without dementia are necessary to design. Then, dedicated clinical trials trazodone on behavioral and psychological disturbances in the rapidly growing number of older adults with dementia.

Acknowledgements

We thank Gilda Borselli for her precious support for the organization of the GeroCovid initiative. Co-authors, members of the GeroCovid OBSERVATIONAL Working Group (in alphabetical order): Angela Marie Abbatecola [ASL Frosinone; RSA INI Città Bianca, Veroli (FR)], Domenico Andrieri [RSA Villa Santo Stefano, S. Stefano di Rogliano (CS)], Sara Antenucci [Ambulatorio Psicogeriatrico, Ortona (CH)], Rachele Antognoli (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Pisana; RSA Villa Isabella, Pisa), Raffaele Antonelli Incalzi (Università Campus Bio-Medico, Roma), Maria Paola Antonietti (Ospedale Regionale di Aosta), Viviana Bagalà (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Ferrara), Giulia Bandini (USL Toscana Centro, Ospedale San Jacopo, Pistoia), Salvatore Bazzano [ULSS 3 Serenissima, Presidio di Dolo (VE)], Giuseppe Bellelli (Ospedale San Gerardo, Monza), Andrea Bellio (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Federico Bellotti (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Ferrara), Enrico Benvenuti [USL Toscana Centro, Ospedale Santa Maria Annunziata, Bagno a Ripoli (FI)], Marina Bergamin (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Parma), Marco Bertolotti (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena), Carlo Adriano Biagini (USL Toscana Centro, Ospedale San Jacopo, Pistoia), Angelo Bianchetti (Istituto Clinico Sant’Anna, Brescia), Alessandra Bianchi [Spedali Civili, Montichiari (BS)], Mariangela Bianchi (Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna), Paola Bianchi (Associazione Nazionale Strutture Territoriali e per la Terza Età, Roma), Francesca Biasin (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Silvia Bignamini (Casa di Cura San Francesco, Bergamo), Damiano Blandini (Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna), Stefano Boffelli (Fondazione Poliambulanza, Brescia), Cristiano Bontempi (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Alessandra Bordignon (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Luigi Maria Bracchitta (ATS Milano), Maura Bugada (Casa di Cura San Francesco, Bergamo), Carmine Cafariello [RSA Villa Sacra Famiglia, IHG, Roma; I RSA Geriatria, IHG, Guidonia (RM); III RSA Geriatria, IHG, Guidonia (RM); RSA Estensiva, IHG, Guidonia (RM); RSA Intensiva, IHG, Guidonia (RM)], Veronica Caleri (USL Toscana Centro, Ospedale San Jacopo, Pistoia), Valeria Calsolaro (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Pisana; RSA Villa Isabella, Pisa), Donatella Calvani (USL Toscana Centro, Presidio Misericordia e Dolce, Prato; USL Toscana Centro, Ospedale Santo Stefano, Prato), Francesco Antonio Campagna [Centro di Riabilitazione San Domenico, Lamezia Terme (CZ)], Andrea Capasso (ASL Napoli 2 Nord), Sebastiano Capurso [RSA Bellosguardo, Civitavecchia (RM)], Silvia Carino [RSA San Domenico, Lamezia Terme (CZ); Centro di Riabilitazione San Domenico, Lamezia Terme (CZ); RSA Villa Elisabetta, Cortale (CZ); Casa Protetta Madonna del Rosario, Lamezia Terme (CZ)], Elisiana Carpagnano (Ospedale Giovanni XXIII Policlinico di Bari), Barbara Carrieri (IRCCS INRCA, Ancona), Viviana Castaldo (Presidio Ospedaliero Universitario Santa Maria della Misericordia, Udine), Manuela Castelli [Istituto Geriatrico Camillo Golgi, Abbiategrasso (MI)], Manuela Castellino [Fatebenefratelli, Presidio Ospedaliero Riabilitativo "Beata Vergine Consolata", San Maurizio Canavese (TO)], Alessandro Cavarape (Presidio Ospedaliero Universitario Santa Maria della Misericordia, Udine), Ilaria Cazzulani (Ospedale San Gerardo, Monza), Carilia Celesti (Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico, Roma), Chiara Ceolin (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Maria Giorgia Ceresini (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Ferrara), Arcangelo Ceretti [Istituto Geriatrico Camillo Golgi, Abbiategrasso (MI)], Antonio Cherubini (IRCCS INRCA, Ancona), Anita Chizzoli (Istituto Clinico Sant’Anna, Brescia), Erika Ciarrocchi (IRCCS INRCA, Ancona), Paola Cicciomessere (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria di Foggia), Alessandra Coin (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Mauro Colombo [Istituto Geriatrico Camillo Golgi, Abbiategrasso (MI)], Annalisa Corsi (USL Toscana Centro, Ospedale San Jacopo, Pistoia), Antonella Crispino [RSA Villa Santo Stefano, S. Stefano di Rogliano (CS); RSA Villa Silvia, Altilia Grimaldi (CS)], Roberta Cucunato [RSA Villa Santo Stefano, S. Stefano di Rogliano (CS); RSA Villa Silvia, Altilia Grimaldi (CS)], Carlo Custodero (Ospedale Giovanni XXIII Policlinico di Bari), Federica D’Agostino [Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, S. Giovanni Rotondo (FG)], Maria Maddalena D’Errico [Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, S. Giovanni Rotondo (FG)], Ferdinando D’Amico [RSA San Giovanni di Dio, Patti (ME); RSA Sant’Angelo di Brolo (ME)], Aurelio De Iorio (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Parma), Alessandro De Marchi [Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna), Annalaura Dell’Armi (III RSA Geriatria, IHG, Guidonia (RM)], Marta Delmonte (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Ferrara), Giovambattista Desideri [Ospedale di Avezzano (AQ)], Maria Devita (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Evelyn Di Matteo (Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico, Roma), Emma Espinosa [Azienda Ospedali Riuniti Marche Nord, Fano (PU)], Luigi Esposito [Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, S. Giovanni Rotondo (FG)], Chiara Fazio (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Parma), Christian Ferro [RSA Sant’Angelo di Brolo (ME)], Chiara Filippini [Spedali Civili, Montichiari (BS)], Filippo Fini (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Lucia Fiore [Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, S. Giovanni Rotondo (FG)], Serafina Fiorillo [ASP Vibo Valentia; RSA Madonna delle Grazie, Filadelfia (VV); Casa di Riposo Mons. Francesco Luzzi, Acquaro (VV); Casa di Riposo Villa Betania, Mileto (VV); Casa di Riposo Pietro Rosano, Dasà (VV); Casa di Riposo Serena Diocesi, Mileto (VV); Alloggio per Anziani Villa Amedeo, Francavilla Angitola (VV); Casa Albergo Villa Fabiola, Monterosso Calabro (VV); Casa di Riposo Villa Sara, San Nicola da Crissa (VV); Casa di Riposo Don Mottola, Tropea (VV); Casa di Riposo San Francesco, Soriano Calabro (VV); RSA Anziani, Soriano Calabro (VV); Casa di Riposo Suore Missionarie del Catechismo, Pizzo (VV)], Caterina Fontana (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena), Lina Forte [Ospedale di Avezzano (AQ)], Riccardo Franci Montorzi (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi, Firenze), Carlo Fumagalli (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi, Firenze), Stefano Fumagalli (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi, Firenze), Pietro Gareri (ASP Catanzaro), Pier Paolo Gasbarri (Associazione Nazionale Strutture Territoriali e per la Terza Età, Roma), Antonella Giordano (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi, Firenze), Evelina Giuliani [USL Toscana Centro, Ospedale Santa Maria Annunziata, Bagno a Ripoli (FI)], Roberta Granata (RSA Villa Sacra Famiglia, IHG, Roma), Antonio Greco [Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, S. Giovanni Rotondo (FG)], Nadia Grillo [RSA San Domenico, Lamezia Terme (CZ); Casa di Riposo San Domenico, Lamezia Terme (CZ); RSA Villa Elisabetta, Cortale (CZ)], Antonio Guaita [Istituto Geriatrico Camillo Golgi, Abbiategrasso (MI)], Liana Gucciardino (ASP Agrigento), Andrea Herbst (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi, Firenze), Marilena Iarrera [RSA Sant’Angelo di Brolo (ME)], Giuseppe Ielo (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Parma), Valerio Alex Ippolito [Casa Protetta Villa Azzurra, Roseto Capo Spulico (CS)], Antonella La Marca [Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, S. Giovanni Rotondo (FG)], Umberto La Porta (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Parma), Ilaria Lazzari (Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna), Diana Lelli (Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico, Roma), Yari Longobucco (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Parma), Francesca Lubian (Ospedale di Bolzano), Giulia Lucarelli (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi, Firenze; USL Toscana Centro, Ospedale San Jacopo, Pistoia), Flaminia Lucchini (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi, Firenze), Daniela Lucente [Spedali Civili, Montichiari (BS)], Lorenzo Maestri (Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna), Marcello Maggio (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Parma), Paola Mainquà [Azienda Ospedali Riuniti Marche Nord, Fano (PU)], Mariangela Maiotti [Ospedale San Giovanni Battista, Foligno (PG)], Alba Malara [RSA San Domenico, Lamezia Terme (CZ); Casa di Riposo Villa Marinella, Amantea (CS); Casa Protetta Madonna del Rosario, Lamezia Terme (CZ); Casa Protetta Villa Azzurra, Roseto Capo Spulico (CS); Centro di Riabilitazione San Domenico, Lamezia Terme (CZ); RSA Casa Amica, Fossato Serralta (CZ); RSA La Quiete, Castiglione Cosentino (CS); Casa di Riposo San Domenico, Lamezia Terme (CZ); RSA Villa Elisabetta, Cortale (CZ); RSA Villa Santo Stefano, S. Stefano di Rogliano (CS); RSA Villa Silvia, Altilia Grimaldi (CS)], Carlotta Mancini (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi, Firenze), Irene Mancuso [RSA San Giovanni di Dio, Patti (ME)], Eleonora Marelli [Istituto Geriatrico Camillo Golgi, Abbiategrasso (MI)], Alessandra Marengoni [Spedali Civili, Montichiari (BS)], Eleonora Marescalco (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Benedetta Martin [Ospedale di Avezzano (AQ)], Valentina Massa [Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, S. Giovanni Rotondo (FG)], Giulia Matteucci (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Ferrara), Irene Mattioli (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Ferrara), Liliana Mazza (Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna), Carmela Mazzoccoli (Ospedale Giovanni XXIII Policlinico di Bari), Fiammetta Monacelli (IRCCS Policlinico San Martino, Genova), Paolo Moneti (RSA Villa Gisella, Firenze), Fabio Monzani (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Pisana; RSA Villa Isabella, Pisa), Federica Morellini (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena), Maria Teresa Mormile (ASL Napoli 2 Nord), Enrico Mossello (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi, Firenze), Chiara Mussi (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena), Francesca Maria Nigro (USL Toscana Centro, Ospedale Santo Stefano, Prato), Marianna Noale (RSA AltaVita, Istituzioni Riunite di Assistenza, Padova), Chukwuma Okoye (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Pisana), Giuseppe Orio (Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna), Sara Osso [RSA La Quiete, Castiglione Cosentino (CS)], Chiara Padovan (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Annalisa Paglia (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria di Foggia), Giulia Pelagalli (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi, Firenze), Laura Pelizzoni (Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna), Agostino Perri [RSA La Quiete, Castiglione Cosentino (CS)], Maria Perticone [Casa di Riposo Villa Marinella, Amantea (CS)], Giacomo Piccardo (IRCCS Policlinico San Martino, Genova), Alessandro Picci (Presidio Ospedaliero Universitario Santa Maria della Misericordia, Udine), Margherita Pippi [Ospedale San Giovanni Battista, Foligno (PG)], Giuseppe Provenzano (ASP Agrigento), Matteo Pruzzo (IRCCS Policlinico San Martino, Genova), Francesco Raffaele Addamo [RSA San Giovanni di Dio, Patti (ME)], Cecilia Raffaelli (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Francesca Remelli (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Ferrara), Onofrio Resta (Ospedale Giovanni XXIII Policlinico di Bari), Antonella Riccardi (Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna), Daniela Rinaldi (Ospedale di Comunità (Camposampiero), Distretto Alta Padovana, ULSS 6 Euganea, Padova), Renzo Rozzini (Fondazione Poliambulanza, Brescia), Matteo Rubino (IRCCS Policlinico San Martino, Genova), Carlo Sabbà (Ospedale Giovanni XXIII Policlinico di Bari), Leonardo Sacco [Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, S. Giovanni Rotondo (FG)], Mariateresa Santoliquido [Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, S. Giovanni Rotondo (FG)], Mariella Savino [Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, S. Giovanni Rotondo (FG)], Francesco Scarso (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Sant’Andrea, Roma), Giuseppe Sergi (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Gaetano Serviddio (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria di Foggia), Claudia Sgarito (ASP Agrigento), Giovanni Sgrò [RSA Istituto Santa Maria del Soccorso, Serrastretta (CZ); RSA San Vito Hospital, San Vito sullo Jonio (CZ); Casa Protetta Villa Mariolina, Montauro (CZ); Casa Protetta Villa Sant’Elia, Marcellinara (CZ)], Chiara Sidoli (Ospedale San Gerardo, Monza), Federica Sirianni [Casa di Riposo Villa Marinella, Amantea (CS)], Vincenzo Solfrizzi (Ospedale Giovanni XXIII Policlinico di Bari), Benedetta Soli (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena), Debora Spaccaferro [RSA Estensiva, IHG, Guidonia (RM); RSA Intensiva, IHG, Guidonia (RM)], Fausto Spadea [RSA Casa Amica, Fossato Serralta (CZ)], Laura Spadoni [Ospedale San Giovanni Battista, Foligno (PG)], Laura Tafaro (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Sant’Andrea, Roma), Luca Tagliafico (IRCCS Policlinico San Martino, Genova), Andrea Tedde (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena), Camilla Terziotti (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Giuseppe Dario Testa (USL Toscana Centro, Ospedale San Jacopo, Pistoia), Maria Giulia Tinti [Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, S. Giovanni Rotondo (FG)], Francesco Tonarelli (USL Toscana Centro, Presidio Misericordia e Dolce, Prato), Elisabetta Tonon (USL Toscana Centro, Ospedale San Jacopo, Pistoia), Caterina Trevisan (Ospedale di Comunità (Camposampiero), Distretto Alta Padovana, ULSS 6 Euganea, Padova; Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Rita Ursino [I RSA Geriatria, IHG, Guidonia (RM)], Filomena Vella (Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Giuliano Isontina, Trieste), Maria Villanova (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Aurora Vitali (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Ferrara), Stefano Volpato (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Ferrara), Francesca Zoccarato (Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova), Sonia Zotti (Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico, Roma), Amedeo Zurlo (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Ferrara).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: AC, MN, RAI. Methodology: AC, MN, CT, PG, AM, EM, SV, SF, SS, GZ. Data Collection: the GeroCovid Observational Working Group. Formal analysis and investigation: MN, FF, AB, CT. Writing—original draft preparation: AC, AB, FF, AMA, PG, CT, EM. Writing—review and editing: AC, AMA, AM, GB, FM, RAI. Resources: RAI. Supervision: AC, RAI.

Funding

This study received unconditioned funding from Angelini Pharma S. p. A. The founder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication. All authors declare no other competing interests.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The GeroCovid Observational study protocol was approved by the Campus Bio-Medico University Ethical Committee in April 2020. All participating investigational sites further submitted relevant sub-protocols to their competent local ethical committee and institutional review boards, as applicable according to Italian regulations. All investigators accepted to work according to the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) (ICH E6-R2).

Informed consent

Written or dematerialized informed consent was obtained from each participant. Alternatively, a written declaration was kept on file by the local investigator, which responded to applicable derogations during the pandemic.

Footnotes

The members of The GeroCovid Observational Working Group are listed in Acknowledgements.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Alessandra Coin, Email: alessandra.coin@unipd.it.

The GeroCovid Observational Working Group:

Angela Marie Abbatecola, Domenico Andrieri, Rachele Antognoli, Raffaele Antonelli Incalzi, Maria Paola Antonietti, Viviana Bagalà, Giulia Bandini, Salvatore Bazzano, Giuseppe Bellelli, Andrea Bellio, Federico Bellotti, Enrico Benvenuti, Marina Bergamin, Marco Bertolotti, Carlo Adriano Biagini, Angelo Bianchetti, Alessandra Bianchi, Mariangela Bianchi, Paola Bianchi, Francesca Biasin, Silvia Bignamini, Damiano Blandini, Stefano Boffelli, Cristiano Bontempi, Alessandra Bordignon, Luigi Maria Bracchitta, Maura Bugada, Carmine Cafariello, Veronica Caleri, Valeria Calsolaro, Donatella Calvani, Francesco Antonio Campagna, Andrea Capasso, Sebastiano Capurso, Silvia Carino, Elisiana Carpagnano, Barbara Carrieri, Viviana Castaldo, Manuela Castelli, Manuela Castellino, Alessandro Cavarape, Ilaria Cazzulani, Carilia Celesti, Chiara Ceolin, Maria Giorgia Ceresini, Arcangelo Ceretti, Antonio Cherubini, Anita Chizzoli, Erika Ciarrocchi, Paola Cicciomessere, Alessandra Coin, Mauro Colombo, Annalisa Corsi, Antonella Crispino, Roberta Cucunato, Carlo Custodero, Federica D’Agostino, Maria Maddalena D’Errico, Ferdinando D’Amico, Aurelio De Iorio, Alessandro De Marchi, Annalaura Dell’Armi, Marta Delmonte, Giovambattista Desideri, Maria Devita, Evelyn Di Matteo, Emma Espinosa, Luigi Esposito, Chiara Fazio, Christian Ferro, Chiara Filippini, Filippo Fini, Lucia Fiore, Serafina Fiorillo, Caterina Fontana, Lina Forte, Riccardo Franci Montorzi, Carlo Fumagalli, Stefano Fumagalli, Pietro Gareri, Pier Paolo Gasbarri, Antonella Giordano, Evelina Giuliani, Roberta Granata, Antonio Greco, Nadia Grillo, Antonio Guaita, Liana Gucciardino, Andrea Herbst, Marilena Iarrera, Giuseppe Ielo, Valerio Alex Ippolito, Antonella La Marca, Umberto La Porta, Ilaria Lazzari, Diana Lelli, Yari Longobucco, Francesca Lubian, Giulia Lucarelli, Flaminia Lucchini, Daniela Lucente, Lorenzo Maestri, Marcello Maggio, Paola Mainquà, Mariangela Maiotti, Alba Malara, Carlotta Mancini, Irene Mancuso, Eleonora Marelli, Alessandra Marengoni, Eleonora Marescalco, Benedetta Martin, Valentina Massa, Giulia Matteucci, Irene Mattioli, Liliana Mazza, Carmela Mazzoccoli, Fiammetta Monacelli, Paolo Moneti, Fabio Monzani, Federica Morellini, Maria Teresa Mormile, Enrico Mossello, Chiara Mussi, Francesca Maria Nigro, Marianna Noale, Chukwuma Okoye, Giuseppe Orio, Sara Osso, Chiara Padovan, Annalisa Paglia, Giulia Pelagalli, Laura Pelizzoni, Agostino Perri, Maria Perticone, Giacomo Piccardo, Alessandro Picci, Margherita Pippi, Giuseppe Provenzano, Matteo Pruzzo, Francesco Raffaele Addamo, Cecilia Raffaelli, Francesca Remelli, Onofrio Resta, Antonella Riccardi, Daniela Rinaldi, Renzo Rozzini, Matteo Rubino, Carlo Sabbà, Leonardo Sacco, Mariateresa Santoliquido, Mariella Savino, Francesco Scarso, Giuseppe Sergi, Gaetano Serviddio, Claudia Sgarito, Giovanni Sgrò, Chiara Sidoli, Federica Sirianni, Vincenzo Solfrizzi, Benedetta Soli, Debora Spaccaferro, Fausto Spadea, Laura Spadoni, Laura Tafaro, Luca Tagliafico, Andrea Tedde, Camilla Terziotti, Giuseppe Dario Testa, Maria Giulia Tinti, Francesco Tonarelli, Elisabetta Tonon, Caterina Trevisan, Rita Ursino, Filomena Vella, Maria Villanova, Aurora Vitali, Stefano Volpato, Francesca Zoccarato, Sonia Zotti, and Amedeo Zurlo

References

- 1.Niculescu I, Arora T, Iaboni A. Screening for depression in older adults with cognitive impairment in the homecare setting: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25(9):1585–1594. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1793899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ulbricht CM, Rothschild AJ, Hunnicutt JN, Lapane KL. Depression and cognitive impairment among newly admitted nursing home residents in the USA: depression and cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(11):1172–1181. doi: 10.1002/gps.4723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickett YR, Raue PJ, Bruce ML. Late-life depression in home healthcare. Aging Health. 2012;8(3):273–284. doi: 10.2217/ahe.12.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steffen A, Nübel J, Jacobi F, Bätzing J, Holstiege J. Mental and somatic comorbidity of depression: a comprehensive cross-sectional analysis of 202 diagnosis groups using German nationwide ambulatory claims data. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):142. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02546-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parrotta I, De Mauleon A, Abdeljalil AB, et al. Depression in people with dementia and caregiver outcomes: results from the European Right Time Place Care Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(6):872–878.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henskens M, Nauta IM, Vrijkotte S, Drost KT, Milders MV, Scherder EJA. Mood and behavioral problems are important predictors of quality of life of nursing home residents with moderate to severe dementia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(12):e0223704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birrer RB, Vemuri SP (2004) Depression in later life: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge 69(10):8 [PubMed]

- 8.Van der Veen D, Van Zelst W, Schoevers R, Comijs H, Oude Voshaar R. Comorbid anxiety disorders in late-life depression: results of a cohort study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(7):1157–1165. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214002312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, Leucht S, Ruhe HG, Turner EH, Higgins JPT, Egger M, Takeshima N, Hayasaka Y, Imai H, Shinohara K, Tajika A, Ioannidis JPA, Geddes JR. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1357–1366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haria M, Fitton A, McTavish D. Trazodone. A review of its pharmacology, therapeutic use in depression and therapeutic potential in other disorders. Drugs Aging. 1994;4(4):331–355. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199404040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaffer KY, Chang T, Vanle B, Dang J, Steiner AJ, Loera N, Abdelmesseh M, Danovitch I, Ishak WW (2017) Trazodone for insomnia: a systematic review. Innov Clin Neurosci 14(7–8):24–34 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Khouzam HR. A review of trazodone use in psychiatric and medical conditions. Postgrad Med. 2017;129(1):140–148. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2017.1249265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macías Saint-Gerons D, Huerta Álvarez C, García Poza P, Montero Corominas D, de la Fuente Honrubia C (2018) Trazodone utilization among the elderly in Spain. A population based study. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment 11(4):208–215. 10.1016/j.rpsm.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Iaboni A, Bronskill SE, Reynolds KB, Wang X, Rochon PA, Herrmann N, Flint A. Changing pattern of sedative use in older adults: a population-based cohort study. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(7):523–533. doi: 10.1007/s40266-016-0380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trevisan C, Del Signore S, Fumagalli S, Gareri P, Malara A, Mossello E, Volpato S, Monzani F, Coin A, Bellelli G, Zia G, Ranhoff AH, Antonelli Incalzi R, GeroCovid Working Group Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on the health of geriatric patients: The European GeroCovid Observational Study. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;87:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbatecola AM, Antonelli Incalzi R, Malara A, Palmieri A, Di Lonardo A, Borselli G, Russo M, Noale M, Fumagalli S, Gareri P, Mossello E, Trevisan C, Volpato S, Monzani F, Coin A, Bellelli G, Okoye C, Del Signore S, Zia G, Bottoni E, Cafariello C, Onder G, GeroCovid Observational, GeroCovid Vax Group (2021) Disentangling the impact of COVID-19 infection on clinical outcomes and preventive strategies in older persons: an Italian perspective. J Gerontol Geriatr 2021:1–9. 10.36150/2499-6564-N440

- 17.MedDRA (2022) Organisation. https://www.meddra.org/about-meddra/organisation. Accessed 8 May 2022

- 18.Hsu CW, Tseng WT, Wang LJ, Yang YH, Kao HY, Lin PY. Comparative effectiveness of antidepressants on geriatric depression: real-world evidence from a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2022;1(296):609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casey DA. Depression in older adults. Prim Care Clin Off Pract. 2017;44(3):499–510. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedna K, Fastbom J, Jonson M, Wilhelmson K, Waern M. Psychoactive medication use and risk of suicide in long-term care facility residents. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022 doi: 10.1002/gps.5684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giovannini S, Onder G, van der Roest HG, Topinkova E, Gindin J, Cipriani MC, Denkinger MD, Bernabei R, Liperoti R, SHELTER Study Investigators Use of antidepressant medications among older adults in European long-term care facilities: a cross-sectional analysis from the SHELTER study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):310. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01730-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Settimo L, Taylor D. Evaluating the dose-dependent mechanism of action of trazodone by estimation of occupancies for different brain neurotransmitter targets. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2018;32(1):96–104. doi: 10.1177/0269881117742101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bossini L, Casolaro I, Koukouna D, Cecchini F, Fagiolini A. Off-label uses of trazodone: a review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(12):1707–1717. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.699523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odagaki Y, Toyoshima R, Yamauchi T. Trazodone and its active metabolite m-chlorophenylpiperazine as partial agonists at 5-HT1A receptors assessed by [35S]GTPγS binding. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2005;19(3):235–241. doi: 10.1177/0269881105051526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gareri P, Falconi U, De Fazio P, De Sarro G. Conventional and new antidepressant drugs in the elderly. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;61(4):353–396. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(99)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saletu-Zyhlarz GM, Anderer P, Arnold O, Saletu B. Confirmation of the neurophysiologically predicted therapeutic effects of trazodone on its target symptoms depression, anxiety and insomnia by postmarketing clinical studies with a controlled-release formulation in depressed outpatients. Neuropsychobiology. 2003;48(4):194–208. doi: 10.1159/000074638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.López-Pousa S, Garre-Olmo J, Vilalta-Franch J, Turon-Estrada A, Pericot-Nierga I. Trazodone for Alzheimer’s disease: a naturalistic follow-up study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;47(2):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lebert F, Stekke W, Hasenbroekx C, Pasquier F. Frontotemporal dementia: a randomised, controlled trial with trazodone. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(4):355–359. doi: 10.1159/000077171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cankurtaran ES. Management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Noro Psikiyatri Arsivi. 2014;51(4):303–312. doi: 10.5152/npa.2014.7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seitz DP, Adunuri N, Gill SS, Gruneir A, Herrmann N, Rochon P (2011) Antidepressants for agitation and psychosis in dementia. Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group (ed) Cochrane database system review. Published online February 16, 2011. 10.1002/14651858.CD008191.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Stryjer R, Strous RD, Bar F, Poyurovsky M, Weizman A, Kotler M. Treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia with the 5-HT2A antagonist trazodone. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2003;26(3):137–141. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burke AD, Goldfarb D, Bollam P, Khokher S. Diagnosing and treating depression in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol Ther. 2019;8(2):325–350. doi: 10.1007/s40120-019-00148-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. 2015;350:h369–h369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Draper B, Berman K. Tolerability of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: issues relevant to the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(6):501–519. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barry LC, Abou JJ, Simen AA, Gill TM. Under-treatment of depression in older persons. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):789–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boehlen FH, Freigofas J, Herzog W, Meid AD, Saum KU, Schoettker B, Brenner H, Haefeli WE, Wild B. Evidence for underuse and overuse of antidepressants in older adults: results of a large population-based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(4):539–547. doi: 10.1002/gps.5047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drageset J, Eide GE, Ranhoff AH. Anxiety and depression among nursing home residents without cognitive impairment. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27(4):872–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ray KD, Mittelman MS. Music therapy: a nonpharmacological approach to the care of agitation and depressive symptoms for nursing home residents with dementia. Dementia. 2017;16(6):689–710. doi: 10.1177/1471301215613779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guerrera CS, Furneri G, Grasso M, Caruso G, Castellano S, Drago F, Di Nuovo S, Caraci F. Antidepressant drugs and physical activity: a possible synergism in the treatment of major depression? Front Psychol. 2020;11:857. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]