Abstract

Electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use is becoming more widespread, and studies show that they are not absolutely harmless. To investigate the association between the dual use of e-cigarettes and marijuana with sleep duration among adults in the United States, this cross-sectional study used data from 6,573 participants aged 18–64 years from 2015 to 2018 from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database. Chi-square tests and analysis of variance were used for bivariate analyses of binary and continuous variables, respectively. Multinomial logistic regression models were used for univariate and multivariate analyses of e-cigarette use, marijuana use, and sleep duration. Sensitivity analyses were conducted in populations with dual e-cigarette and traditional cigarette use and dual marijuana and traditional cigarette use. People who concurrently use e-cigarettes and marijuana had higher odds of not having the recommended sleep duration than neither users (short sleep duration: odds ratio [OR], 2.34; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19–4.61; P = 0.014; long sleep duration: OR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.53–2.87; P < 0.001) and a shorter sleep duration than e-cigarette only users (OR, 4.24; 95% CI, 1.75–4.60; P < 0.001). Concurrent traditional cigarette and marijuana users had higher odds of long sleep duration than neither users (OR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.21–3.24; P = 0.0065). Almost half of the people who concurrently use e-cigarettes and marijuana had both short and long sleep durations compared to neither users and short sleep duration compared to e-cigarette only users. Longitudinal randomized controlled trials are needed to explore the joint effect of dual tobacco use on sleep health.

Keywords: E-cigarette, Tobacco, Marijuana, Dual use, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Sleep

1. Introduction

Sleep disturbances have been a public health issue for years. However, the problem has plagued nearly a quarter of the world’s population and has become a subject of greater concern in recent years (Irish et al., 2015, Brown et al., 2018, Laver et al., 2020; Miner and Kryger, 2017). These disturbances include sleep apnea, insomnia, restless leg syndrome, sleepwalking, and poor sleep quality, which may all lead to abnormal sleep duration (Chokroverty, 2010, Janson et al., 1995). According to the National Sleep Foundation, the recommended sleep duration for people aged 18–64 years is 7–9 h. Babies, young children, and teens need even more sleep to enable their growth and development. People over 65 years also require 7–8 h of sleep per night (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015).

Smoking cigarettes has been heavily implicated as the cause of common sleep problems (Cohrs et al., 2014, Wetter and Young, 1994, Deleanu et al., 2016, Jaehne et al., 2012, Liu et al., 2013, McNamara et al., 2014, Liao et al., 2019, Hsu et al., 2019, Bogati et al., 2020, Nuñez et al., 2021) and has also been reported to be associated with sleep duration (Chang et al., 2018, Yang et al., 2018), which itself is a risk factor for chronic conditions such as obesity, depression, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) (Gangwisch et al., 2006). These chronic conditions can also lead to poor sleep quality (Gangwisch et al., 2007, Pilcher and Huffcutt, 1996, Wilson and Argyropoulos, 2005, Yaggi et al., 2005, Lavigne et al., 1997) and are likely to be exacerbated by cigarette smoking (Levy et al., 2017). An increasing number of people, especially young adults, currently prefer electronic nicotine delivery systems or e-cigarettes over traditional cigarettes. A nationwide study in the United States (U.S.) examined the characteristics of individuals who used e-cigarettes (McConnell et al., 2017), and the results showed that 27% of former e-cigarette users still use e-cigarettes, and 45.3% of these used e-cigarettes regularly (≥20 days per month). E-cigarettes are widely promoted as a safer alternative to smoking (Gay et al., 2020). However, an increasing number of studies have shown that e-cigarettes are not harmless (Rohde et al., 2020; Russell and Cevik, 2020b) and are also reported to be associated with sleep health (Marques et al., 2021, Wiener et al., 2020, Riehm et al., 2019, Kianersi et al., 2021, Brett et al., 2020, Merianos et al., 2021, Lee and Lee, 2021, Monti and Pandi-Perumal, 2022). Similar concerns have been raised regarding the use of marijuana, which is also popular among young Americans. The use of cannabinoids is a double-edged sword because they have both adverse and therapeutic properties (Lavender et al., 2022, Shannon et al., 2019, Kaul et al., 2021, Choi et al., 2020, Mondino et al., 2021, Kolla et al., 2022). Evidence shows that chronic cannabis administration could disrupt circadian rhythms and reduce the duration of the deepest phase (stage N3) of non-rapid eye movement sleep (Vaseghi et al., 2021). However, the effects of cannabinoids on the sleep-wake cycle are inconsistent (Maultsby et al., 2021, Chen et al., 2020). Given the high rate of cannabis use among Americans, it is especially important to study its effect as well as the joint effect of cigarettes on sleep health. Therefore, this study was conducted to observe the association between sleep duration and dual use of e-cigarettes and marijuana in a U.S. population with a large age range (18–64 years) representative of young adults and adults.

2. Participants and methods

2.1. Study population

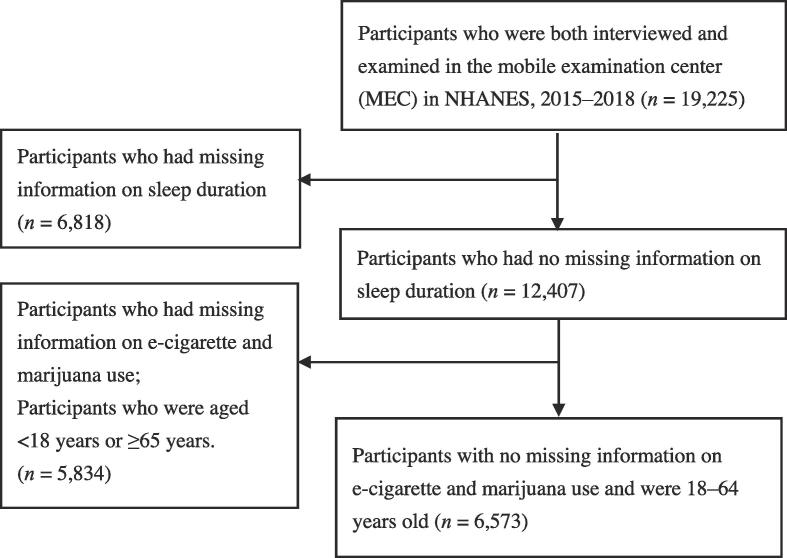

The data in this study were obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2015–2018 cycle, which contains data on both cigarette and marijuana use and sleep duration. NHANES is a cross-sectional nationwide survey in which participants are selected using a stratified multistage probability design and is thus representative of the U.S. population. NHANES is unique because it combines interviews and physical examinations. The interviews included demographic, dietary, and health-related questions. The examination component consisted of medical, dental, and physiological measurements as well as laboratory tests administered by highly trained medical personnel (Goodhines et al., 2019) (more details via https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm). Fig. 1 shows the flowchart for the selection of the study participants. Adults aged 18–64 years who participated in the 2015–2018 NHANES surveys and had complete data on sleep duration, e-cigarette use, and marijuana use were included in the analysis. This study was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board. The approval number is Continuation of Protocol #2011–17 for the 2015–2018 cycle.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for the selection of study participants in the current analysis. NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

2.2. Study procedure

Dependent variable: Sleep duration.

Sleep duration was assessed through household interviews using a computer-assisted personal interviewing system. Participants were asked the following question: “How much sleep (in hours) do you usually get at night, on weekdays or workdays?” According to the National Sleep Foundation’s recommended sleep duration for people aged 18–64 years, we categorized weekday sleep duration as <7, 7–9 h (reference group), and >9 h per night, which we defined as short, normal, and long sleep durations, respectively.

Independent variables: E-cigarette and marijuana use was categorized as neither use of e-cigarette nor marijuana, e-cigarette use only, marijuana use only, and dual e-cigarette and marijuana use.

E-cigarette users were asked the following questions: “Have you ever used an e-cigarette, even once?” and “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use e-cigarettes?” Participants who had not used an e-cigarette even once were defined as “never users,” those who had used e-cigarettes before but had not used them in the last 30 days were defined as “former users,” whereas those who had used e-cigarettes in the last 30 days were termed as “current users.”

Marijuana users were defined using the following questions: “Have you ever, even once, used marijuana or hashish?” and “How long has it been since you last used marijuana or hashish?” Participants who had not used marijuana or hashish even once were defined as “never users,” those who had used marijuana or hashish before but had not in the last 30 days were defined as “former users,” whereas those who had used marijuana or hashish in the last 30 days were termed as “current users.”

“Dual e-cigarette and marijuana users” refer to participants who had used both e-cigarettes and marijuana in the last 30 days. Participants who did not use e-cigarettes or marijuana in the last 30 days were defined as “neither users;” “e-cigarette only users” were those who used e-cigarettes but not marijuana, whereas “marijuana only users” were participants who had used marijuana but not e-cigarettes in the last 30 days.

Traditional cigarette users were asked the following questions: “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” and “Do you currently smoke cigarettes?” Participants who had not smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their entire lives were “never users.” Participants who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lives but did not smoke now were defined as “former users,” while those who still smoked were “current users.”

Covariate variables: Age, sex, race, annual household income, being overweight/obese, education level, marriage status, occupation, depression (Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ] score), serum cotinine level, chronic diseases (including diabetes, CVD, and asthma), and snoring or difficulty in breathing.

Being overweight/obese was defined as a body mass index ≥25. Snoring or difficulty in breathing was a symptom of sleep disorders. Participants were asked the following questions: “In the past 12 months, how often did {you/Survey participants} snort, gasp, or stop breathing while {you were} asleep?” Individuals were categorized as “never,” “1–4 nights/week,” or “≥5 nights/week,” according to the frequency. Depression severity was calculated using the PHQ score, with a PHQ score < 10 classified as minimal to mild depression, 10–14 as moderate depression, and ≥15 as severe depression. Chronic diseases such as diabetes, CVD, and asthma, which can also affect sleep duration, were also considered (Liu et al., 2013, Levy et al., 2017, McConnell et al., 2017, Gay et al., 2020, Rohde et al., 2020, Russell et al., 2020a, Marques et al., 2021).

2.3. Statistical analysis

Chi-square tests and analysis of variance were used for bivariate analyses of binary and continuous variables, respectively. Multinomial logistic regression models were used for univariate and multivariate analyses of e-cigarette, marijuana use, and sleep duration. Variables in the final model were selected according to the results of the univariate analysis. All multivariable models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, other Hispanic, and others), annual household income (<$20,000 vs. ≥$20,000), being overweight/obese, serum cotinine level, cigarette use (current user and former user vs. never user), education level (more than high school and high school graduate vs. less than high school), marriage status (married/living together and divorced/separated vs. widowed/never married), severity of depression (severe and moderate depression vs. minimal to mild depression), occupation (with a job vs. jobless/looking for a job), snoring or difficulty in breathing (frequently, occasionally, and rarely vs. never), and chronic diseases (yes vs. no). A two-tailed P value < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference. The R Program version 3.6.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computer, Vienna, Austria; https://www.r-project.org) was used for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Proportion of e-cigarette dual use

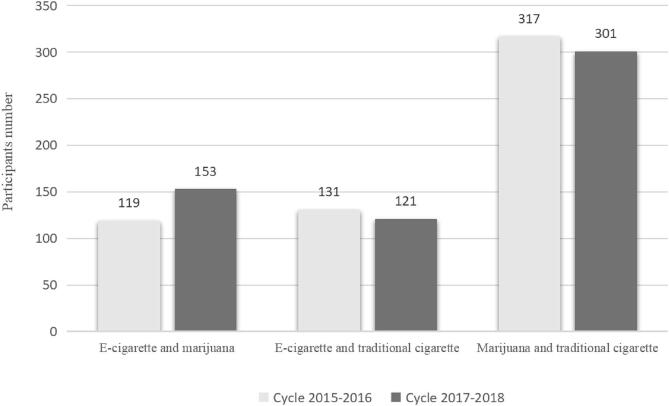

The main characteristics of the 6,573 study participants are shown in Table 1. Of all the participants, 80.77% were aged 26–64 years, while the rest were aged 18–25 years; 75.20% had normal sleep duration, 16.02% had short sleep duration, and 8.78% had long sleep duration. We also found that 20.39% of the participants were former e-cigarette users, 7.71% were current e-cigarette users (data not presented), 28.58% were current marijuana users, 4.23% concurrently used e-cigarette and marijuana, 4.01% used both e-cigarette and traditional cigarette, and 9.27% used marijuana and traditional cigarette concurrently (Table 1 and Table A.1). Additionally, among those who did not have the recommended sleep duration, 43.8% were people who concurrently used e-cigarette and marijuana (data not presented). The number of participants who used both e-cigarettes and marijuana increased over time (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Main characteristics of all participants (n = 6,573), NHANES 2015–2018, 18–64 years.

| Number | Weighted percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18-25y | 1,375 | 19.23 |

| 26-64y | 5,198 | 80.77 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 3,416 | 50.17 |

| Male | 3,157 | 49.83 |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2,032 | 59.52 |

| Mexican American | 1,142 | 10.97 |

| Other Hispanic | 704 | 7.45 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1,473 | 12.00 |

| Other | 1,222 | 10.07 |

| Annual household income<$20,000 | 1,511 | 11.58 |

| Overweight/obese,yes | 4,576 | 70.16 |

| E-cigarette - marijuana use | ||

| Neither use | 4,592 | 67.93 |

| E-cigarette use only | 208 | 3.48 |

| Marijuana use only | 1,501 | 24.36 |

| Dual use | 272 | 4.23 |

| Traditional cigarette use | ||

| Never use | 4,175 | 60.25 |

| former use | 1,052 | 19.78 |

| Current use | 1,344 | 19.97 |

| Education level | ||

| Less than high school | 1,209 | 12.02 |

| High school graduate | 1,603 | 24.30 |

| More than high school | 3,760 | 63.68 |

| Marriage status | ||

| Windowed/never married | 1,628 | 25.02 |

| Divorced/separated | 759 | 11.38 |

| Married/living together | 3,698 | 63.60 |

| Occupation | ||

| No job/looking for a job | 1,817 | 22.10 |

| Already have a job | 4,749 | 77.90 |

| Depression (PHQ score) | ||

| Minimal to mild | 6,130 | 93.80 |

| Moderate | 290 | 4.37 |

| Severe | 142 | 1.83 |

| Chronic diseases, yes | 1,189 | 0.19 |

| Snort or stop breathing | ||

| Never | 4,768 | 75.98 |

| 1–4 nights/week | 1,207 | 19.49 |

| 5 or more nights/week | 3,12 | 4.53 |

| Sleep duration | ||

| <7h | 1,186 | 16.02 |

| 7–9 h | 4,667 | 75.20 |

| >9h | 720 | 8.78 |

The numbers may vary because of missing data. We have missing data on traditional cigarette use, education level, marriage status, occupation, depression and snort or stop breathing.

Chronic diseases include cardiovascular diseases, asthma and diabetes. PHQ: Patient health questionnaire.

Fig. 2.

Number of participants with dual use of tobacco products and marijuana in different cycles (2015–2016 and 2017–2018).

3.2. Participants’ characteristics

Compared to participants with normal sleep duration, those with short sleep duration were more likely to be people who currently used traditional cigarettes or concurrently used tobacco products (Table 2 and Table A.2). Meanwhile, they were also more likely to be older, male, overweight/obese, non-Hispanic black, other Hispanic, widowed or divorced, and frequent snorers or with sleep apnea, to have an education level less than high school or be a high school graduate, have no job or be looking for a job, be moderate to severely depressed, and have an annual household income <$20,000, chronic diseases, and higher serum cotinine level. Participants with long sleep duration yielded similar results, except that they were more likely to be younger, female, not overweight/obese, but not snoring or having difficulty breathing at night (Table 2).

Table 2.

Main characteristics stratified by sleep duration and the findings regarding sleep duration and electronic cigarette-marijuana dual use, NHANES 2015–2018, 18–64 years (n = 6,573).

| Sleep duration |

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short (<7h) (n = 1,186) |

Normal (7–9 h) (n = 4,667) |

Long (>9h) (n = 720) |

||

| Age, y | 40.79 ± 0.46 | 38.82 ± 0.29 | 33.82 ± 0.64 | <0.001*** |

| Sex | <0.001*** | |||

| Female | 518(40.60) | 2,462(51.00) | 436(60.47) | |

| Male | 668 (59.40) | 2,205 (49.00) | 284 (39.53) | |

| Race | <0.001*** | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 282 (49.88) | 1,534 (62.52) | 216 (51.41) | |

| Mexican American | 175 (11.01) | 833 (10.60) | 134 (14.05) | |

| Other Hispanic | 141 (9.62) | 487 (6.91) | 76 (8.04) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 409 (20.75) | 886 (9.61) | 178 (16.48) | |

| Other | 179 (8.74) | 927 (10.36) | 116 (10.02) | |

| Annual household income <$20,000 | 279 (12.17) | 999 (9.84) | 233 (25.39) | <0.001*** |

| Overweight/obese, yes | 898 (75.04) | 3,229 (69.60) | 449 (65.99) | <0.001*** |

| E-cigarette-marijuana use | <0.001*** | |||

| Neither use | 797 (63.57) | 3,335 (69.90) | 460 (59.07) | |

| E-cigarette use only | 37 (3.16) | 141 (3.41) | 30 (4.69) | |

| Marijuana use only | 283 (26.13) | 1,037 (23.41) | 181 (29.24) | |

| Dual use | 69 (7.14) | 154 (3.28) | 49 (7.00) | |

| Traditional cigarette use | <0.001*** | |||

| Never use | 671 (50.59) | 3,050 (62.44) | 454 (59.10) | |

| former use | 187 (20.07) | 782 (20.52) | 83 (12.98) | |

| Current use | 328 (29.34) | 833 (17.04) | 183 (27.92) | |

| Serum cotinine, μg/mL | 0.094 ± 0.0070 | 0.052 ± 0.0039 | 0.067 ± 0.0073 | <0.001*** |

| Education level | <0.001*** | |||

| Less than high school | 237 (15.05) | 789 (10.20) | 183 (22.12) | |

| High school graduate | 315 (30.06) | 1,047 (21.75) | 241 (35.63) | |

| More than high school | 634 (54.89) | 2,830 (68.05) | 296 (42.25) | |

| Marriage status | <0.001*** | |||

| Windowed/never married | 306 (24.80) | 1,108 (23.95) | 214 (35.54) | |

| Divorced/separated | 165 (13.52) | 513 (10.66) | 81 (13.82) | |

| Married/living together | 665 (61.68) | 2,734 (65.39) | 299 (50.64) | |

| Occupation | <0.001*** | |||

| No job/looking for a job | 278 (20.28) | 1152(19.04) | 387 (51.62) | |

| Already have a job | 908 (79.72) | 3509(80.96) | 332(48.38) | |

| Snort or stop breathing | <0.001*** | |||

| Never | 791 (69.63) | 3,440 (77.21) | 537 (76.78) | |

| 1–4 nights/week | 235 (22.94) | 838 (18.77) | 134 (19.44) | |

| 5 or more nights/week | 92(7.43) | 197 (4.02) | 23 (3.78) | |

| Depression severity (PHQ score) | <0.001*** | |||

| Minimal to mild | 1,077 (90.36) | 4,413(95.01) | 640 (89.75) | |

| Moderate | 68 (6.20) | 173(3.71) | 49 (6.63) | |

| Severe | 39 (3.44) | 74(1.28) | 29 (3.62) | |

| Chronic diseases | 0.0018** | |||

| No | 814 (78.93) | 3,357 (82.73) | 410 (74.41) | |

| Yes | 261 (21.07) | 766 (17.27) | 162 (25.59) | |

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Values are presented as numbers (%) or mean (mean ± standard deviation).

The numbers may vary because of missing data. We have missing data on traditional cigarette use, education level, marriage status, occupation, depression and snort or stop breathing.

Chronic diseases include cardiovascular diseases, asthma and diabetes. PHQ: Patient health questionnaire.

3.3. Association between e-cigarette dual use and sleep duration

We found that current marijuana only users had a significant 1.49 times higher odds of long sleep duration than neither users (Table 3). People who currently used both e-cigarettes and marijuana had 2.26-fold higher odds of short sleep duration and 2.56-fold higher odds of long sleep duration than those who were currently using neither e-cigarettes nor marijuana. Similar results were observed when analyzing the association between dual e-cigarette and traditional cigarette use or traditional cigarette and marijuana use and sleep duration (Tables A.3 and A.4). Meanwhile, people who currently used only traditional cigarettes had significantly higher odds of both short and long sleep duration than neither users. After adjusting for confounders (including age, sex, race, annual household income, overweight/obese, smoking status, cotinine level, education level, marital status, occupation, depression severity, snoring or difficulty in breathing, and chronic diseases), those who dual use e-cigarette and marijuana had 2.34- and 2.09-fold significantly higher odds than neither users in the groups with short and long sleep durations, respectively. They also had a significant 4.24-fold higher odds of having short sleep duration than those who used only e-cigarettes (Table 4). We also found that people with concurrent traditional cigarette and marijuana use had a significant 1.98-fold higher odds of having long sleep duration than neither users (Table A.5). However, no significant differences were observed between dual e-cigarette and traditional cigarette use and sleep duration (Table A.6).

Table 3.

Association between sleep duration and dual use of e-cigarette and marijuana, NHANES 2015–2018, 18–64 years (n = 6,573, univariate).

| Sleep duration |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short (<7h) (n = 1,186) |

Normal (7–9 h) (n = 4,667) |

Long (>9h) (n = 720) |

|||

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| E-cigarette - marijuana use | Ref. | ||||

| E-cigarette only vs. neither | 1.06 (0.65, 1,75) | 0.80 | 1.60 (0.68, 3.73) | 0.28 | |

| Marijuana only vs. neither | 1.20 (0.88, 1.64) | 0.24 | 1.49 (1.27, 1.75) | <0.001*** | |

| Dual vs. neither | 2.26 (1.47, 3.47) | <0.001*** | 2.56 (1.95, 3.35) | <0.001*** | |

| Marijuana only vs. e-cigarette only | 1.15 (0.64, 2.07) | 0.64 | 0.91 (0.43, 1.92) | 0.80 | |

| Dual vs. E-cigarette only | 2.14 (1.45, 3.14) | <0.001*** | 1.57 (0.72, 3.44) | 0.26 | |

| Dual vs. marijuana only | 1.86 (1.10, 3.14) | 0.021 | 1.73 (1.35, 2.24) | <0.001*** | |

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The models were all unadjusted.

Table 4.

Association between sleep duration and dual use of e-cigarette and marijuana, NHANES 2015–2018, 18–64 years (n = 6,573, multivariate).

| Sleep duration |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short (<7h) (n = 1,186) |

Normal (7–9 h) (n = 4,667) |

Long (>9h) (n = 720) |

|||

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| E-cigarette - marijuana use | Ref. | ||||

| E-cigarette only vs. neither | 0.85 (0.45, 1.59) | 0.61 | 0.85 (0.29, 2.44) | 0.76 | |

| Marijuana only vs. neither | 1.12 (0.78, 1.61) | 0.53 | 1.46 (0.95, 2.25) | 0.08 | |

| Dual vs. neither | 2.34 (1.19, 4.61) | 0.014* | 2.09 (1.53, 2.87) | <0.001*** | |

| Marijuana only vs. e-cigarette only | 0.84 (0.67, 2.77) | 0.40 | 0.99 (0.61, 4.73) | 0.32 | |

| Dual vs. E-cigarette only | 4.24 (1.75, 4.60) | <0.001*** | 1.67 (0.86, 6.68) | 0.095 | |

| Dual vs. marijuana only | 1.88 (0.97, 4.51) | 0.060 | 1.20 (0.80, 2.53) | 0.23 | |

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The models were all adjusted for age, sex, race, annual household income, overweight/obese, smoking status (traditional cigarette), cotinine level, education level, marital status, occupation, depression severity, snort or stop breathing, and chronic diseases.

OR: Odds ratio. CI: Confidence interval.

4. Discussion

As sleep health is attracting more attention, the objective of the current study was to investigate whether e-cigarette and marijuana dual use was associated with sleep duration among adults. In this cross-sectional survey study of 6,573 participants aged 18–64 years in the U.S., 24.80% had short or long sleep duration according to National Sleep Foundation (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015). Meanwhile, 3.48% of the participants used only e-cigarettes currently, 24.36% used only marijuana currently, 4.23% used both e-cigarettes and marijuana, 4.01% used e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes concurrently, and 9.27% used both marijuana and traditional cigarette. We also found that former or current e-cigarette use, current marijuana use, current dual e-cigarette and marijuana use, and current traditional cigarette use were more likely to be associated with a non-recommended sleep duration.

Prior studies have reported that e-cigarette use was associated with worse sleep health, especially among the youth (Brett et al., 2020, Riehm et al., 2019, Kianersi et al., 2021). Wiener RC et al. reported that participants who currently used e-cigarettes were 1.82-fold more likely not to get their recommended sleep duration compared with participants who never used e-cigarettes (Riehm et al., 2019). Other studies have found that co-users of e-cigarettes with other tobacco products may have more emotional problems and experience more harm than e-cigarette-only users (Kang and Bae, 2021, Abafalvi et al., 2019, Lee and Lee, 2019, Berlin et al., 2019, Advani et al., 2022). Kang and Bae (2021) conducted a study to examine between-groups differences in depression and sleep quality based on smoking/vaping status among Korean adults and showed that dual users of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes had significantly higher depression scores (PHQ-9) and significantly lower sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index-Korean version), respectively, than did cigarette users and non-users. Abafalvi et al. (2019) reported that dual users of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes were significantly more likely to report adverse effects of vaping than e-cigarette-only users (26.2% vs. 11.8%, P < 0.001). Lee and Lee (2019) were the first to report that dual users of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes had a higher prevalence of depression and suicidal tendencies among South Korean adolescents. Berlin et al. (2019) found that dual users of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes in France may have higher overall nicotine intake than exclusive e-cigarette users, but they may take in less nicotine from their e-cigarettes. A study conducted by Advani et al. (2022) demonstrated that dual use of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes was associated with longer sleep latency, and the shared component of nicotine may be a driver. However, to date, there are no studies on the relationship between e-cigarette and cannabis co-use and sleep health in such a large age group.

Marijuana use has been reported to be associated with either a short or long sleep duration in previous studies (Babson et al., 2017, Bhagavan et al., 2020, Pupko, 2018, Schwenk et al., 2022) and is sometimes perceived as providing benefits as a sleep aid (Goodhines et al., 2019, Doremus et al., 2019, Diep et al., 2022, Drazdowski et al., 2021), which served as a double-edged sword. Schwenk et al. found that recent cannabis users had greater adjusted odds of reporting both short and long sleep. Heavy users, those who were using cannabis for at least 20 of the past 30 days, were even more likely to report sleep durations at the extreme ends of the range (Schwenk et al., 2022). From a sample representing approximately 146 million adults in the U.S., recent cannabis use was associated with the extremes of nightly sleep duration, with suggestions of a dose–response relationship (Diep et al., 2022). In our study, we did not observe a significant association between marijuana or e-cigarette single use and short or long sleep duration. However, there was a significant association between dual e-cigarette and marijuana use and both short and long sleep duration. Compared to e-cigarette only use, dual use had 4.24-fold higher odds of short sleep duration. Meanwhile, compared to neither use, dual use had 2.34-fold higher odds of short sleep duration and 2.09-fold higher odds of long sleep duration. The results indicate that people with dual e-cigarette and marijuana use are more likely to have short sleep duration than single tobacco users, and both had a sleep duration that is not recommended when compared to neither users. We also found that current use of traditional cigarettes was significantly associated with a sleep duration that is not recommended (both short and long), but there was no significant association between dual e-cigarette and traditional cigarette use with the recommended sleep duration. We posit that it might be because of the decline in the use of traditional cigarettes when also using e-cigarettes.

5. Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, we lacked data on weekend sleep duration, which prevented us from analyzing the effects of tobacco exposure on weekday and weekend sleep duration separately and exploring the differences. Second, we lacked data on sleep behavior and polysomnography parameters, which would describe the affected sleep conditions in more detail. Third, because all interview data were collected by questionnaires, such as smoking status, recall bias could not be avoided. Finally, although our study suggests that dual e-cigarette and marijuana use was associated with a sleep duration that is outside of the recommended range, we still could not confirm a causal association between them.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, our study suggests that almost half of the people who concurrently used e-cigarettes and marijuana had a non-recommended sleep duration. Dual use of e-cigarettes and marijuana was associated with both short and long sleep duration compared to neither use and short sleep duration compared to e-cigarette only use. Future longitudinal randomized controlled trials are needed to explore the joint effect of dual tobacco and marijuana use on human sleep health.

Funding

This study was supported by the Medical Innovation Team of Jiangsu Province [grant no. CXTDB 2017016]; the Major Program of Wuxi Health and Family Planning Commission [grant no. Z202016]; Wuxi Medical Talents [grant no. QNRC071]; the Youth Project of Wuxi Health and Family Planning Commission [grant no. Q201837]; the Top Talent Support Program for young and middle-aged people of the Wuxi Health Committee [grant no. HB2020088], and Maternal and child health project of Wuxi Health Commission [grant number FYKY202204].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhenzhen Pan: Data curation, Writing – original draft. Qian Wang: Data curation, Validation. Yun Guo: Investigation, Visualization. Shidi Xu: Investigation, Visualization. Shanshan Pan: Data curation, Validation. Shiyao Xu: Writing – review & editing. Qin Zhou: Writing – review & editing. Ling Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Government of Jiangsu Province and Medical Innovation Team of Jiangsu Province and Wuxi Municipal Bureau on Science and Technology for their financial support. We would like to thank Wei Chen and Yueh-ying Han from the Division of Pediatric Pulmonary Medicine, UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh for directing the research design. We would like to thank Ying Ding and Tao Sun of Biostatistics, Public Health, University of Pittsburgh for directing the statistics of this research. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102190.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abafalvi L., Pénzes M., Urbán R., Foley K.L., Kaán R., Kispélyi B., Hermann P. Perceived health effects of vaping among Hungarian adult e-cigarette-only and dual users: a cross-sectional internet survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6629-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Advani I., Gunge D., Boddu S., Mehta S., Park K., Perera S., Pham J., Nilaad S., Olay J., Ma L., Masso-Silva J., Sun X., Jain S., Malhotra A., Crotty Alexander L.E. Dual use of e-cigarettes with conventional tobacco is associated with increased sleep latency in cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2022;12(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-06445-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babson K.A., Sottile J., Morabito D. Cannabis, cannabinoids, and sleep: a review of the literature. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:23. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0775-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin I., Nalpas B., Targhetta R., Perney P. Comparison of e-cigarette use characteristics between exclusive e-cigarette users and dual e-cigarette and conventional cigarette users: an on-line survey in France. Addiction. 2019;114(12):2247–2251. doi: 10.1111/add.14780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagavan C., Kung S., Doppen M., John M., Vakalalabure I., Oldfield K., Braithwaite I., Newton-Howes G. Cannabinoids in the treatment of insomnia disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2020;34(12):1217–1228. doi: 10.1007/s40263-020-00773-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogati S., Singh T., Paudel S., Adhikari B., Baral D. Association of the pattern and quality of sleep with consumption of stimulant beverages, cigarette and alcohol among medical students. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2020;18(3):379–385. doi: 10.33314/jnhrc.v18i3.2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett E.I., Miller M.B., Leavens E.L.S., Lopez S.V., Wagener T.L., Leffingwell T.R. Electronic cigarette use and sleep health in young adults. J. Sleep Res. 2020;29(3):e12902. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown W.J., Wilkerson A.K., Boyd S.J., et al. A review of sleep disturbance in children and adolescents with anxiety. J. Sleep Res. 2018;27:e12635. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L.-Y., Chang H.-Y., Wu W.-C., Lin L.N., Wu C.-C., Yen L.-L. Dual trajectories of sleep duration and cigarette smoking during adolescence: Relation to subsequent internalizing problems. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2018;46(8):1651–1663. doi: 10.1007/s10802-018-0414-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.C., Clark J., Riddles M.K., et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2015–2018: sample design and estimation procedures. Vital Health Stat. 2020;2(184):1–35. PMID: 33663649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S., Huang B.C., Gamaldo C.E. Therapeutic uses of cannabis on sleep disorders and related conditions. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020;37:39–49. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0000000000000617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chokroverty S. Overview of sleep & sleep disorders. Indian J. Med. Res. 2010;131:126–140. PMID: 20308738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohrs S., Rodenbeck A., Riemann D., Szagun B., Jaehne A., Brinkmeyer J., Gründer G., Wienker T., Diaz-Lacava A., Mobascher A., Dahmen N., Thuerauf N., Kornhuber J., Kiefer F., Gallinat J., Wagner M., Kunz D., Grittner U., Winterer G. Impaired sleep quality and sleep duration in smokers-results from the German multicenter study on nicotine dependence. Addict. Biol. 2014;19(3):486–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleanu O.C., Pocora D., Mihălcuţă S., et al. Influence of smoking on sleep and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pneumologia. 2016;65:28–35. PMID: 27209838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep C., Tian C., Vachhani K., Won C., Wijeysundera D.N., Clarke H., Singh M., Ladha K.S. Recent cannabis use and nightly sleep duration in adults: a population analysis of the NHANES from 2005 to 2018. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2022;47(2):100–104. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2021-103161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doremus J.M., Stith S.S., Vigil J.M. Using recreational cannabis to treat insomnia: evidence from over-the-counter sleep aid sales in Colorado. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019;47 doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.102207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drazdowski T.K., Kliewer W.L., Marzell M. College students' using marijuana to sleep relates to frequency, problematic use, and sleep problems. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2021;69:103–112. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2019.1656634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangwisch J.E., Heymsfield S.B., Boden-Albala B., Buijs R.M., Kreier F., Pickering T.G., Rundle A.G., Zammit G.K., Malaspina D. Short sleep duration as a risk factor for hypertension: analyses of the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hypertension. 2006;47(5):833–839. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000217362.34748.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangwisch J.E., Heymsfield S.B., Boden-Albala B., et al. Sleep duration as a risk factor for diabetes incidence in a large U.S. sample. Sleep. 2007;30:1667–1673. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay B., Field Z., Patel S., Alvarez R.M., Nasser W., Madruga M., Carlan S.J. Vaping-induced lung injury: a case of lipoid pneumonia associated with e-cigarettes containing cannabis. Case Rep. Pulmonol. 2020;2020:7151834. doi: 10.1155/2020/7151834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodhines P.A., Gellis L.A., Ansell E.B., Park A. Cannabis and alcohol use for sleep aid: a daily diary investigation. Health Psychol. 2019;38(11):1036–1047. doi: 10.1037/hea0000765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshkowitz M., Whiton K., Albert S.M., Alessi C., Bruni O., DonCarlos L., Hazen N., Herman J., Katz E.S., Kheirandish-Gozal L., Neubauer D.N., O’Donnell A.E., Ohayon M., Peever J., Rawding R., Sachdeva R.C., Setters B., Vitiello M.V., Ware J.C., Adams Hillard P.J. National Sleep Foundation's sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 2015;1(1):40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu W.-Y., Chiu N.-Y., Chang C.-C., Chang T.-G., Lane H.-Y. The association between cigarette smoking and obstructive sleep apnea. Tobacco Induc. Dis. 2019;17(April) doi: 10.18332/tid/105893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish L.A., Kline C.E., Gunn H.E., Buysse D.J., Hall M.H. The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: a review of empirical evidence. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015;22:23–36. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaehne A., Unbehaun T., Feige B., Lutz U.C., Batra A., Riemann D. How smoking affects sleep: a polysomnographical analysis. Sleep Med. 2012;13(10):1286–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson C., Gislason T., De Backer W., et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances among young adults in three European countries. Sleep. 1995;18:589–597. PMID: 8552930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S.G., Bae S.M. The effect of cigarette use and dual-use on depression and sleep quality. Subst. Use Misuse. 2021;56:1869–1873. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2021.1958855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul M., Zee P.C., Sahni A.S. Effects of cannabinoids on sleep and their therapeutic potential for sleep disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2021;18:217–227. doi: 10.1007/s13311-021-01013-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kianersi S., Zhang Y., Rosenberg M., et al. Association between e-cigarette use and sleep deprivation in U.S. Young adults: results from the 2017 and 2018 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Addict. Behav. 2021;112 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolla B.P., Hayes L., Cox C., et al. The effects of cannabinoids on sleep. J. Prim. Care Community Health. 2022;13 doi: 10.1177/21501319221081277. 21501319221081277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender I., McGregor I.S., Suraev A., Grunstein R.R., Hoyos C.M. Cannabinoids, insomnia, and other sleep disorders. Chest. 2022;162(2):452–465. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2022.04.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laver K.E., Spargo C., Saggese A., Ong V., Crotty M., Lovato N., Stevens D., Vakulin A. Sleep Disturbance and disorders within adult inpatient rehabilitation settings: a systematic review to identify both the prevalence of disorders and the efficacy of existing interventions. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020;21(12):1824–1832.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne G.L., Lobbezoo F., Rompré P.H., et al. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor or an exacerbating factor for restless legs syndrome and sleep bruxism. Sleep. 1997;20:290–293. PMID: 9231955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Lee K.S. Association of depression and suicidality with electronic and conventional cigarette use in South Korean adolescents. Subst. Use Misuse. 2019;54:934–943. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2018.1552301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B.G., Lee H. Associations between cigarette and electronic cigarette use and sleep health in Korean adolescents: an analysis of the 14th (2018) Korea Youth Risk Behavior Surveys. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2021;51:380–389. doi: 10.4040/jkan.21034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D.T., Yuan Z., Li Y. The prevalence and characteristics of e-cigarette users in the U.S. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017;14:1200. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14101200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y., Xie L., Chen X., Kelly B.C., Qi C., Pan C., Yang M., Hao W., Liu T., Tang J. Sleep quality in cigarette smokers and nonsmokers: findings from the general population in central China. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6929-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.-T., Lee I.-H., Wang C.-H., Chen K.-C., Lee C.-I., Yang Y.-K. Cigarette smoking might impair memory and sleep quality. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2013;112(5):287–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques P., Piqueras L., Sanz M.J. An updated overview of e-cigarette impact on human health. Respir. Res. 2021;22:151. doi: 10.1186/s12931-021-01737-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maultsby K.D., Luk J.W., Sita K.R., Lewin D., Simons-Morton B.G., Haynie D.L. Three dimensions of sleep, somatic symptoms, and marijuana use in U.S. high school students. J. Adolesc. Health. 2021;69(1):50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell R., Barrington-Trimis J.L., Wang K., et al. Electronic cigarette use and respiratory symptoms in adolescents. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017;195:1043–1049. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0804OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara J.P., Wang J., Holiday D.B., et al. Sleep disturbances associated with cigarette smoking. Psychol. Health Med. 2014;19:410–419. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2013.832782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merianos A.L., Jandarov R.A., Choi K., et al. Combustible and electronic cigarette use and insufficient sleep among U.S. high school students. Prev. Med. 2021;147 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner B., Kryger M.H. Sleep in the aging population. Sleep Med. Clin. 2017;12:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondino A., Cavelli M., González J., et al. Effects of cannabis consumption on sleep. Adv Exp. Med. Biol. 2021;1297:147–162. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-61663-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti J.M., Pandi-Perumal S.R. Clinical management of sleep and sleep disorders with cannabis and cannabinoids: implications to practicing psychiatrists. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2022;45:27–31. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0000000000000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez A., Rhee J.U., Haynes P., et al. Smoke at night and sleep worse? The associations between cigarette smoking with insomnia severity and sleep duration. Sleep Health. 2021;7:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2020.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher J.J., Huffcutt A.I. Effects of sleep deprivation on performance: a meta-analysis. Sleep. 1996;19:318–326. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.4.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pupko H.A. Medical marijuana in treating obstructive sleep apnea. CMAJ. 2018;90:E572. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.69128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehm K.E., Rojo-Wissar D.M., Feder K.A., et al. E-cigarette use and sleep-related complaints among youth. J. Adolesc. 2019;76:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde J.A., Noar S.M., Mendel J.R., et al. E-cigarette health harm awareness and discouragement: implications for health communication. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020;22:1131–1138. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell C., Katsampouris E., Mckeganey N. Harm and addiction perceptions of the JUUL E-cigarette among adolescents. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020;22:713–721. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell C.D., Cevik M. Pulmonary Illness Related to E-Cigarette Use. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;382(4):385–386. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1915111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk E.S., Gupta R.K., Diep C. Recent cannabis use and nightly sleep duration in adults: an infographic. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2022;47:105. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2021-103294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon S., Lewis N., Lee H., et al. Cannabidiol in anxiety and sleep: a large case series. Perm. J. 2019;23:18–041. doi: 10.7812/TPP/18-041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaseghi S., Arjmandi-Rad S., Nasehi M., et al. Cannabinoids and sleep-wake cycle: the potential role of serotonin. Behav. Brain Res. 2021;412 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2021.113440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter D.W., Young T.B. The relation between cigarette smoking and sleep disturbance. Prev. Med. 1994;23:328–334. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener R.C., Waters C., Bhandari R., et al. The association of sleep duration and the use of electronic cigarettes, NHANES, 2015–2016. Sleep Dis. 2020;2020:8010923. doi: 10.1155/2020/8010923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S., Argyropoulos S. Antidepressants and sleep: a qualitative review of the literature. Drugs. 2005;65:927–947. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaggi H.K., Concato J., Kernan W.N., et al. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:2034–2041. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Durmer J.L., Wheaton A.G., et al. Sleep duration and excess heart age among US adults. Sleep Health. 2018;4:448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.