Highlights

-

•

Retail environment policies were negatively associated with student past-month use of tobacco/vape, cannabis, and co-use.

-

•

Retailer density near schools was positively associated with student past-month tobacco/vape use and co-use.

-

•

Policies that reduce retailer density near schools may curb youth exposure and access to tobacco and cannabis retailers.

Keywords: Retailer density, Geographic effects, Policy, Cannabis, Tobacco

Abstract

Adolescent tobacco use (particularly vaping) and co-use of cannabis and tobacco have increased, leading some jurisdictions to implement policies intended to reduce youth access to these products; however, their impacts remain unclear. We examine associations between local policy, density of tobacco, vape, and cannabis retailers around schools, and adolescent use and co-use of tobacco/vape and cannabis.

We combined 2018 statewide California (US) data on: (a) jurisdiction-level policies related to tobacco and cannabis retail environments, (b) jurisdiction-level sociodemographic composition, (c) retailer locations (tobacco, vape, and cannabis shops), and (d) survey data on 534,176 middle and high school students (California Healthy Kids Survey). Structural equation models examined how local policies and retailer density near schools are associated with frequency of past 30-day cigarette smoking or vaping, cannabis use, and co-use of tobacco/vape and cannabis, controlling for jurisdiction-, school-, and individual-level confounders.

Stricter retail environment policies were associated with lower odds of past-month use of tobacco/vape, cannabis, and co-use of tobacco/vape and cannabis. Stronger tobacco/vape policies were associated with higher tobacco/vape retailer density near schools, while stronger cannabis policies and overall policy strength (tobacco/vape and cannabis combined) were associated with lower cannabis and combined retailer densities (summed tobacco/vape and cannabis), respectively. Tobacco/vape shop density near schools was positively associated with tobacco/vape use odds, as was summed retailer density near schools and co-use of tobacco, cannabis.

Considering jurisdiction-level tobacco and cannabis control policies are associated with adolescent use of these substances, policymakers may proactively leverage such policies to curb youth tobacco and cannabis use.

1. Introduction

Developments in the dynamic tobacco and cannabis retail environments may contribute to upsurges in youth vaping (e-cigarette use) and co-use of tobacco and cannabis (Borodovsky et al., 2017, California Tobacco Education and Research Oversight Committee, 2018) in recent years. For instance, the emergence of e-cigarettes and legalization in some states of non-medical cannabis have led to novel specialty retailers including vape shops and cannabis dispensaries (Lee et al., 2018, Unger et al., 2020). Some suggest that certain local policies might curb youth access to and use of these products, but this remains understudied (Lipperman-Kreda et al., 2012). Yet place-based policies, such as local retailer licensing requirements, may increase health equity by creating healthier retail environments in vulnerable neighborhoods (Lawman, 2019). For example, a longitudinal study found that those who lived in jurisdictions with stronger tobacco retail license ordinances (e.g., requiring an annual fee sufficient to cover enforcement costs) had lower prevalence of cigarette use, as well as lower odds of initiation of cigarettes and e-cigarettes (Astor et al., 2019).

This study draws on social ecological models (Bronfenbrenner, 1999, McLeroy et al., 1988)—which highlight how individual health behaviors are associated with multi-level factors ranging from policy, to community, to individual factors—to understand adolescent smoking, vaping, and tobacco and cannabis co-use. Several studies report that retailer density around schools is associated with youth smoking experimentation (Gwon et al., 2016, McCarthy et al., 2009) or smoking susceptibility (Chan and Leatherdale, 2011). A California study found that greater tobacco outlet density is associated with youth smoking, particularly in cities with weak local clean air policies (few 100% smoke-free policies for public spaces, multiunit housing, etc.) (Lipperman-Kreda et al., 2012). Others found no association between tobacco retailer density around schools and youth smoking prevalence, but found that greater advertisement density was positively associated with youth use (Henriksen et al., 2008). Similarly mixed results have been reported in the vape and cannabis literatures. An Orange County, California, study found a positive association between vape shop density around schools and student vape experimentation (Bostean et al., 2016), while a Canadian study found no such association with student vaping (Cole et al., 2019). Cannabis studies report a positive association between presence of a cannabis retailer near schools and high school student cannabis use in Oregon (Firth et al., 2022), while in Colorado proximity of stores was not associated with perceived ease of access among adolescents (Harpin et al., 2018). Thus, conclusions about how retailer densities around school are associated with student substance use remain elusive.

Despite evidence of adolescent co-use of cannabis and tobacco, and of associations between tobacco retailer density and co-use (Lipperman-Kreda et al., 2022), the literatures on cannabis and tobacco retailers remain largely separate (Gwon et al., 2016, Shi et al., 2018). Additionally, the cannabis literature has focused on medical dispensaries (Freisthler and Gruenewald, 2014, Lankenau et al., 2019) since non-medical sales are more recent; for example, in California medical sales began in late 2016 and non-medical began on January 1, 2018. Thus, researchers have an incomplete picture of the tobacco and cannabis retail environments. Finally, few studies to date have examined retail environment as a mediator of the association between policy and youth substance use. The scant research examining how local (i.e., city or county) policy is associated with youth tobacco smoking (Lipperman-Kreda et al., 2012) found only a modified effect of youth access policies (e.g., local tobacco licensing with fee, with penalties for violation) on youth smoking, though this study focused on only one-tenth of California cities. No studies to-date, to our knowledge, have examined how local retail environment policies are associated with retailer density around schools and with youth use of tobacco, vaping and cannabis products, while controlling for individual-, school- and city-level variables (such as racial/ethnic and socioeconomic composition) to account for potential disparities in where policies are implemented.

This study fills these gaps by examining the roles of local policy and tobacco, vape, and cannabis retailer density around schools in adolescent use and co-use of tobacco (smoking and vaping) and cannabis. We focus on policies related to retail environment (e.g., local licensing, zoning regulations, storefront bans) to assess their effectiveness in reducing retailer density around schools. Using statewide California data, we examine: (a) jurisdiction-level strength of tobacco control and cannabis policies (city policies in jurisdictions that have city-level policy, and county-level policies in county unincorporated areas); (b) school-level retailer density; and, (c) individual survey data from the California Healthy Kids Survey on past 30-day use of conventional cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cannabis among California middle and high school students. We examine the extent to which local tobacco and cannabis control policies are associated with student use of those substances, and whether retailer density around schools plays a role in the association. For each domain (tobacco/vape, cannabis, and co-use of tobacco and cannabis), we test the following hypotheses:

H1: Local policy strength is directly negatively associated with student current substance use.

H2: Stronger local policy strength is associated with lower retailer density around schools, controlling for city/county- and school-level confounders.

H3: Retailer density near schools is positively associated with substance use, net of jurisdiction-level, school-level, and individual-level confounders.

2. Methods

2.1. Data

We examined middle and high school students (mainly public schools) throughout California, combining student-level, school-level, and jurisdiction-level data to test our hypotheses. Sociodemographic estimates for places (and county remainder areas, or unincorporated) came from American Community Survey (2015–2019 5-year estimates). Policy strength data for tobacco and vape came from American Lung Association (ALA) 2017 State of Tobacco Control Grades (American Lung Association, 2017). Cannabis policy strength data came from the California Cannabis Local Laws Database for 2018 (Silver et al., 2020). Retailer locations were purchased from the commercial data provider DataAxle (formerly InfoUSA); prior studies have used this data provider (Siahpush et al., 2010). We included verified locations (open in 2018, confirmed with multiple phone calls throughout the year) with the following primary industry codes (NAICS 445120, 445310, 447110, 447190, and 453,991 for tobacco retailers, which includes tobacco shops, gas stations, beer, wine and liquor stores, convenience stores, and SIC 599306 for vape shops, and SIC 512227 for medical and non-medical cannabis shops). We identified 20,986 tobacco retailers (and 318 vape shops), and 326 cannabis shops.

For individual-level measures, we used the California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS)—the largest available state student survey containing a school identifier (for geocoding) and detailed substance use and school climate questions. The survey was administered by school staff and is designed to be fielded at least every two years to students in grades 7, 9 and 11, attending California public schools. Participation is voluntary, anonymous, and confidential, and parental consent was obtained. We used the 2017–2018 academic year wave to ensure the survey administration period overlaps with the period when the retailers were verified to be open (2018); for cannabis retailers, this measure may underestimate access for students who were surveyed in the three-month period prior to opening of cannabis retailers in January 2018.

CHKS survey data were available on N = 612,342 individuals, of whom N = 534,176 (87%) had complete data on all analytic variables (N = 339,920 high school students and N = 194,256 middle school students, nested within 669 and 1064 schools, respectively). This study was deemed to be exempt from human subjects review by the Chapman University Institutional Review Board.

3. Measures

Local policy strength. Tobacco/vape policy strength (0–3) was calculated using data from ALA grades (American Lung Association, 2017); it is the sum of tobacco retail license strength (0 for no license ordinance or a weak license ordinance that does not include a sufficient annual fee for enforcement or penalties for violations, 1 for license with at least a sufficient annual fee), retailer location restrictions (0 for no location restrictions and 1 for at least one location restriction, such as minimum distance from schools), and inclusion of e-cigarettes/vape in the local licensing requirements (0–1). Cannabis policy strength (0–6) is the sum of five dichotomous variables assessing strength of policies related to retail environment (ban of medical or non-medical storefront retailers, retailer cap, retailer minimum distance (buffer) from schools, buffers from sensitive use sites in addition to schools, buffer from other retailers; 0 = no policy, less strict or same as state; 1 = policy stricter than state); places that ban retail storefronts of both medical and non-medical cannabis were given the highest score of 6. All policy variables are coded such that higher numbers indicate stricter policies. Overall policy strength (0–9) is the sum of the tobacco and cannabis policy strength measures.

Retailer density around schools. Consistent with this literature (Marsh et al., 2020), we calculated density as the number of tobacco retailers, vape shops, and cannabis stores within one-half mile walking distance (network buffer) of each school (geocoded by address, thus buffer is computed from address point), which is among the commonly used distances in the tobacco literature (D’Angelo et al., 2016, Henriksen et al., 2008, Marsh et al., 2020). Tobacco retailer density is the count of tobacco retailers and vape shops; Cannabis retailer density is all cannabis retailers (medical and non-medical); and, Summed retailer density is the sum of the tobacco/vape and cannabis retailer counts.

Past month substance use. The survey asked, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use…”: “cigarettes,” “electronic cigarettes, e-cigarettes, or other vaping device such as e-hookah, hookah pens, or vape pens,” “marijuana (smoke, vape, eat, or drink)”; each of the three variables was coded as 0 days = 1, 1 day = 2, 2 days = 3, 3–9 days = 4, 10–19 days = 5, and 20–30 days = 6. Tobacco/vape use is an ordinal variable, created by taking the mean of past-month cigarette smoking and vaping frequency variables; it ranges from 1 to 6 (1 = no smoking or vaping in past 30 days and higher numbers represent more days of use). Cannabis use is an ordinal variable categorizing the number of days in the past 30 that the student used cannabis; coded 1–6, with higher numbers representing more days of use. Co-use of tobacco and cannabis (range 1–6) is the mean of the tobacco/vape use variable and the cannabis use variable.

Control variables. Respondent-level controls included: sex (Male = 0; Female = 1; we included a missing category because 6.5% of the full sample did not answer = 2); race/ethnicity (Latino, Asian, Black, non-Latino White, mixed race, Other; we include a “missing” category in the analyses because over 10% of full sample were missing on this variable); grade level (Middle school = 0; High school = 1); housing arrangement, as a proxy for SES and family stability (lives in a home with parent(s)/guardian(s) = 0; Other housing arrangement = 1); language spoken in home (English = 0 vs. other = 1); depressive symptoms (“During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more that you stopped doing some usual activities?” No = 0; Yes = 1; we included a missing category because over 8% of sample did not answer), and school climate (mean of seven questions about how strongly respondent agrees that: they feel a part of this school, teachers treat students fairly, they feel safe in school, the school is usually clean and tidy, teachers communicate with parents; parents feel welcome to participate, school staff takes parent concerns seriously; coded 1–5, with 5 being strongly agree). School-level controls included percent of students eligible for free/reduced cost lunch and school enrollment. Jurisdiction-level variables were percentage of residents under age 18, percentage non-White, and mean household income (per $10,000).

3.1. Statistical analysis

We first examined sample characteristics. To test our mediation hypotheses, we used structural equation models (SEM), following prior research (Kowitt and Lipperman-Kreda, 2020). We hypothesized a priori that outcomes would be clustered at jurisdiction and school levels and planned to conduct a three-level hierarchical SEM. However, as current substance use did not exhibit clustering at either level (intraclass correlation coefficients were 1%), we fit a single-level model to simplify estimation and improve convergence properties.

We ran models separately for tobacco/vape, cannabis, and co-use of tobacco/vape and cannabis; for each substance use outcome we fit a SEM with an outcome pathway for past 30-day use regressed on jurisdiction-level policy strength and school-level retailer density using ordered logistic regression and a mediator pathway for school-level retailer density regressed on jurisdiction-level policy strength using linear regression. Both regressions included adjustment for jurisdiction- and school-level covariates, and the outcome model additionally included individual-level covariates. To evaluate our mediation hypothesis, we estimated total, direct, and indirect effects using the product method and calculated bootstrap standard errors and 95% confidence intervals with 500 replicates. Analyses were restricted to observations with available data on all analytic variables without use of missing data techniques (e.g., FIML) due to computational complexity. Comparisons between complete and incomplete observations are described in Supplemental Table. Because these cross-sectional data do not permit examination of causal mediation, we examine only potential mediation. All analyses were conducted using the gsem function in Stata 16.1, which does not report SEM fit statistics, to incorporate non-continuous outcomes.

4. Results

Table 1 presents local-, school-, and individual-level characteristics. The mean policy strength across California cities was below 1 for tobacco/vape policy, 5.06 for cannabis policy, and 6 for combined tobacco/vape and cannabis policies, with large standard deviations especially for tobacco policy and retailer density. Among California middle and high school students, frequency of tobacco/vape, cannabis, and co-use was low, with the median being 1 (corresponding to no use in past 30 days) for all three measures. Prevalences (not shown) reveal that approximately half (50.1%) of students had at least one tobacco/vape retailer within 0.5 mi of their school, while less than 1% had a cannabis retailer nearby. Prevalences of any past 30-day use (not shown) were 8.6% for tobacco/vape, 9.4% for cannabis, and 12.4% for co-use. Table 2 reveals some weak correlations between policy and retailer density (positive for tobacco and negative for cannabis).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics: middle and high school respondents to 2017–2018 California Health Kids Survey (N = 534,176).

| Variable | Min-Max | Mean (SD) or % | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local-level retail environment policy strength | |||

| Tobacco (including vape) | 0–3 | 0.95 (1.1) | 1 (2) |

| Cannabis | 0–6 | 5.06 (1.6) | 6 (2) |

| Overall policy strength | 0–9 | 6.01 (1.7) | 6 (1) |

| Number of verified retailers within 0.5 mi of school | |||

| Tobacco retailers (including vape stores) | 0–19 | 1.37 (2.1) | 1 (2) |

| Cannabis | 0–4 | 0.01 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| Summed (Tobacco/vape plus cannabis shops) | 0–20 | 1.4 (2.1) | 1 (2) |

| Past-month tobacco and cannabis use (past 30-day freq, ordinal) | |||

| Tobacco and/or vape use | 1–6 | 1.13 (0.6) | 1 (0) |

| Cannabis use | 1–6 | 1.26 (0.9) | 1 (0) |

| Co-use of vape/cigarettes AND cannabis | 1–6 | 1.19 (0.7) | 1 (0) |

| Local-level covariates | |||

| Mean % Under 18 years | 6.9–36.7 | 23.57 (4.3) | 22.9 (5.4) |

| Mean % non-White | 10.0–98.6 | 59.6 (21.1) | 61.4 (33.1) |

| Mean household income (per $10,000) | 3.9–52.7 | 10.9 (4.1) | 10.4 (4.5) |

| School-level covariates | |||

| Number of students enrolled | 19–4722 | 1569 (8 5 1) | 1458 (1282) |

| % Free/reduced cost lunch eligible | 1.3–100 | 52.6 (26.5) | 52.7 (47.9) |

| Individual-level covariates | |||

| School climate | 1–5 | 3.5 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.9) |

| High school (vs. middle school) | 63.6% | ||

| Depressed | 29.7% | ||

| Female | 49.2% | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| non-Latino White | 22.4% | ||

| non-Latino Asian | 12.0% | ||

| non-Latino Black | 3.4% | ||

| Latino | 7.1% | ||

| Mixed race | 40.3% | ||

| Other | 6.3% | ||

| Primary language at home not English | 36.0% | ||

| Alternate housing | 9.7% | ||

Notes: Depression, sex, and race/ethnicity variables included a “missing” category in analyses due to high non-response. Individual-level data come from 2017 to 2018 California Health Kids Survey; Jurisdiction-level data are from American Community Survey (2015–2019 5-year estimates); Policy strength data for tobacco and vape came from American Lung Association 2017 State of Tobacco Control Grades; Cannabis policy strength data came from the California Cannabis Local Laws Database for 2018; Retailer locations were purchased from a commercial data provider.

Table 2.

Bivariate Spearman correlations between key study variables (N = 534,176).

| Tobacco policy | Cannabis policy | Overall policy | Tobacco retailer density | Cannabis retailer density | Summed retailer density | Tobacco use | Cannabis use | Co-use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco policy | 1.000 | ||||||||

| Cannabis policy | −0.240 | 1.000 | |||||||

| Overall policy | 0.415 | 0.743 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Tobacco retailer density | 0.079 | −0.070 | −0.021 | 1.000 | |||||

| Cannabis retailer density | 0.048 | −0.065 | −0.038 | 0.095 | 1.000 | ||||

| Summed retailer density | 0.079 | −0.071 | −0.021 | 0.998 | 0.125 | 1.000 | |||

| Tobacco use | −0.024 | −0.001 | −0.011 | -0.003 | −0.005 | −0.004 | 1.000 | ||

| Cannabis use | 0.003 | −0.021 | −0.015 | 0.005 | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.601 | 1.000 | |

| Co-use | −0.009 | −0.014 | −0.016 | 0.002 | −0.004 | 0.002 | 0.822 | 0.878 | 1.000 |

Note: Individual-level data come from 2017 to 2018 California Health Kids Survey; Jurisdiction-level data are from American Community Survey (2015–2019 5-year estimates); Policy strength data for tobacco and vape came from American Lung Association 2017 State of Tobacco Control Grades; Cannabis policy strength data came from the California Cannabis Local Laws Database for 2018; Retailer locations were purchased from a commercial data provider.

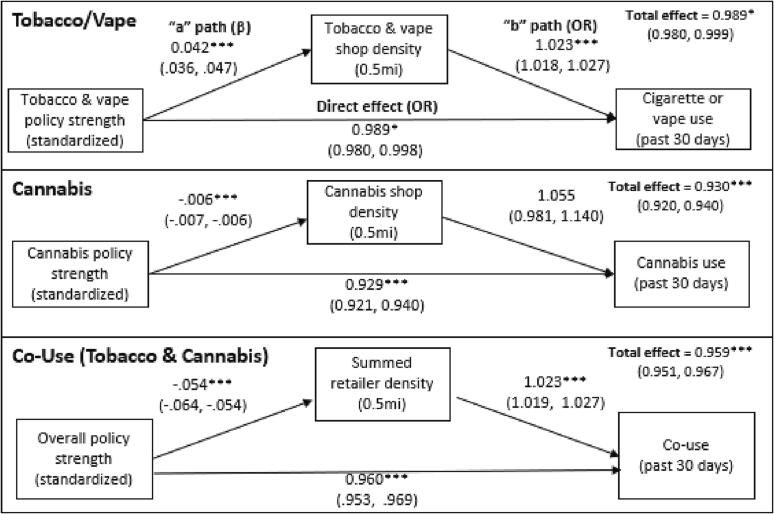

Fig. 1 presents results from structural equation models. Examining past-month tobacco use (smoking and vaping), we observed a significant total effect of tobacco/vape retail policy strength on lower 30-day tobacco use (OR [95% CI] = 0.989 [0.980, 0.999]), representing 1% lower odds of tobacco use per 1 SD increase in policy strength. The observed total effect was predominantly attributable to the direct effect (OR [95% CI] = 0.989 [0.980, 0.998]). Indirect effects suggested that tobacco/vape policy strength was significantly associated with small increases in tobacco/vape retailer density (β [95% CI] = 0.042 [0.036, 0.047]), and that tobacco retailer density was associated with significantly higher odds of tobacco use (OR [95% CI] = 1.023 [1.018, 1.027]).

Fig. 1.

Direct and indirect path coefficients of associations of local policy strength with individual-level tobacco & cannabis use and co-use, through retailer density within ½ mile of schools (N = 534,176). Note: Untransformed β coefficients (from linear regressions) for the indirect “a” pathway represents mean difference in number of retailers within 0.5mi per 1 SD change in policy strength z-score. Odds ratios for direct and indirect “b” pathways represent odds ratios (from ordinal logistic regressions) of reporting higher use in the past 30 days. 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. Asterisks denote pathways that are statistically significant based on bootstrap 95% confidence intervals (500 replicates). Path “a” models control for city-level (% under age 18, % non-White, mean household income) and school-level (school enrollment, % eligible for free/reduced cost lunch) variables, and path “b” models additionally control for individual-level school climate, grade level, depressive symptoms, sex, race/ethnicity, language spoken at home, housing arrangements. Individual-level data come from 2017 to 2018 California Health Kids Survey; Jurisdiction-level data are from American Community Survey (2015–2019 5-year estimates); Policy strength data for tobacco and vape came from American Lung Association 2017 State of Tobacco Control Grades; Cannabis policy strength data came from the California Cannabis Local Laws Database for 2018; Retailer locations were purchased from a commercial data provider.

For cannabis, policy strength was associated with 7% lower odds of 30-day cannabis use per 1 SD increase (OR [95% CI] = 0.930 [0.920, 0.940]), primarily attributable to the direct effect (OR [95% CI] = 0.929 [0.921, 0.940]). Cannabis policy strength was significantly negatively associated with cannabis shop density around schools (β [95% CI] = -0.006 [-0.007, −0.006]), which was in turn not significantly associated with cannabis use.

In terms of co-use of tobacco and cannabis, overall policy strength was negatively associated with co-use (OR [95% CI] = 0.959 [0.951, 0.967]), largely a direct effect (OR [95% CI] = 0.960 [0.931, 0.969]). Moreover, stronger policy was associated with lower summed retailer density (β [95% CI] = -0.054 [-0.064, -0.054]), while summed retailer density was, in turn, positively associated with co-use (OR [95% CI] = 1.023 [1.019, 1.027]).

Overall, findings support Hypothesis 1, that stronger retail environment policies have direct associations with lower past 30-day substance use. They also provide partial support for Hypotheses 2 and 3. Specifically, Hypothesis 2 is supported for cannabis and summed retailer density; stronger cannabis policies are associated with lower cannabis retailer density, and overall policy strength is associated with lower summed (tobacco, vape, and cannabis) retailer density; however, for tobacco, stronger policies are associated with higher retailer density. Hypothesis 3 is supported for tobacco use and co-use; higher tobacco/vape shop density is associated with higher odds of tobacco use, and higher summed retailer density is associated with higher odds of co-use of tobacco and cannabis.

5. Discussion

We extend the literature by examining associations between local retail environment policy strength, density of retailer tobacco, vape, and cannabis retailers around schools, and past-month use and co-use of tobacco/vape and cannabis. In our California sample of middle and high school students, the prevalence of past-month use of tobacco/vape, cannabis, and co-use among was 8%, 10%, 6%, respectively, which is comparable to other California studies’ estimates (2017–2018 California Student Tobacco Survey reported past-month tobacco use among 4% and 13% of middle and high school students, respectively) (Zhu et al., 2019). Importantly, several novel findings contribute to the literature on adolescent use of tobacco and cannabis. First, we observed protective direct associations between policies related to tobacco and cannabis retail environments and adolescent use and co-use of these products, and some limited indirect effects through retailer density around schools. While the data did not permit us to examine multi-level effects, factors at all levels (jurisdiction, school, and individual) were significantly associated with student use of tobacco/vape and cannabis, suggesting that social ecological models are useful in understanding the complex factors impacting individual health behaviors.

For all three outcomes (tobacco, cannabis use, and co-use of these products), we found that stronger policies (e.g., local licensing requirement, retailer location restriction, including e-cigarettes in tobacco regulations, cannabis storefront bans) were associated with lower past-month use among adolescents. Although we hypothesized that policies related to retail environment would operate through modifying the retail environment, our results show that retail environment policies can have protective associations with adolescent use, even if not through retailer density. Prior studies provide similar evidence. For example, one study found a weaker association between tobacco retailer density and adolescent smoking in cities with stronger clean air policies, which could be because clean air policies reinforce norms against youth smoking (Lipperman-Kreda et al., 2012).

The second major finding was that stronger tobacco/vape policy was associated with higher tobacco/vape retailer density around schools, but the opposite was true for cannabis and combined retailer density. There are several possible explanations for the counterintuitive association between tobacco policy strength and retailer density. First, this association may reflect reverse causation—it may be that stronger retail environment policies are adopted in locales with greater need (for instance, in response to retailer density or higher baseline rates of youth tobacco use) or social acceptance of tobacco control regulation. Second, the impact of policy may be concentrated among schools in particular neighborhoods (although we control for several jurisdiction-level factors, we cannot examine neighborhood-level variation). For example, in New York and Missouri, prohibiting sale of tobacco near schools produced greater density reductions in higher-risk (lower income and higher proportion Black residents) than lower-risk neighborhoods (Ribisl et al., 2016). Although the policy-retailer density association was opposite than expected for tobacco, it was in the expected direction for cannabis and summed retailer density. This is likely driven by the fact that most jurisdictions banned cannabis storefronts (which was the highest value on the policy strength measure).

Finally, both tobacco/vape and combined retailer density were associated with higher past-month student use of tobacco and co-use of cannabis and tobacco, respectively; however, the association was not statistically significant for cannabis use alone. To date, the literature on youth tobacco use and retailer density around schools has been mixed (Finan et al., 2019) and difficult to assess due to methodological limitations (Nuyts et al., 2019). We add to the few studies suggesting a positive association between retailer density around schools and student tobacco use (Chan and Leatherdale, 2011, McCarthy et al., 2009), providing support for emerging evidence of the positive correlation between cannabis retailer density around schools and homes and student cannabis use (Firth et al., 2022). Future studies may also consider replicating this analysis using additional retailer density measures such as activity spaces, as our measure of density around schools is but one of the ways to operationalize retailer density.

It is important to note that these findings, while significant, were small in magnitude. However, retail environment policies are distal causes of individual substance use and are not expected to be strongly associated. Rather, these findings are of substantive importance, showing that even small effects of city-level policies translate to potentially large numbers of people affected (in health behaviors) at the population level.

These findings should be interpreted with several limitations in mind. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow us to examine causal associations. While we used measures of policy strength that preceded retailer density measures by one year to ensure temporality, it is possible that a one-year lag is insufficient to capture reductions in tobacco retailer density following policy implementation. However, for cannabis, the lack of lag time may be less relevant because most jurisdictions had policies in place early on—70% of jurisdictions that allowed storefronts in 2018 had medical storefront legalization policies in place at some point in 2017, with legalization policies in place for an average of nine months of 2017. Second, we adjusted for jurisdiction- and school-level demographic and socioeconomic factors related to adoption of strong retail environment policy; however, residual confounding may remain, for example, due to variations in historical tobacco legislation or restrictiveness of commercial zoning laws. Further, the CHKS design introduces some limitations. The non-probability sampling design of the CHKS limits inferences and precludes generalization to the whole California student population. Moreover, the survey may not fully capture co-use because the survey question on vaping does not specifically ask whether the student vaped cannabis or tobacco, thus it is possible that some co-users reported both vaping and cannabis use but could have vaped cannabis (something that cannot be ascertained due to question wording). Nevertheless, the estimates of substance use prevalence are comparable to other California student surveys, and the very large sample and availability of school climate and other measures make this among the best available datasets to answer the current research question. Finally, the very low prevalence of cannabis retailers near schools may limit power to detect associations; considering the dynamic nature of local cannabis laws, future studies should replicate with more recent data, and consider additional mechanisms linking cannabis policy strength and adolescent cannabis use. Regardless, this study provides novel and important evidence from a large, statewide student sample showing that retailer density is associated with past-month use and co-use of tobacco and cannabis.

Overall, findings point to an important link between local retail environments policies around tobacco and cannabis—such as local licensing ordinances, restrictions on retailer locations, and for cannabis, storefront bans—and adolescent use and co-use of tobacco and cannabis. Notably, stronger tobacco retail environment policies are associated with higher retailer density around schools, suggesting that for tobacco retail, policy implementation may be reactive to an unhealthy retail environment. Conversely, the proactive bans on cannabis storefronts are associated with lower retailer density around schools. Considering that jurisdiction-level tobacco and cannabis retail environment policies are associated with adolescent use of these substances, policymakers could proactively leverage such policies to curb youth tobacco and cannabis use.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Georgiana Bostean: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Anton Palma: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Alisa A. Padon: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Erik Linstead: Funding acquisition, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Joni Ricks-Oddie: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Jason A. Douglas: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Jennifer B. Unger: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by American Lung Association to GB (Grant # 688361); Chapman Faculty Opportunity Fund grant to GB; California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program to JD (Grant #: T29IR0677). Cannabis policy data were provided by AP, Award 588174 from the California Tobacco Related Disease Research Program. We thank David Van Riper for his assistance creating data tables and shapefiles for county unincorporated areas using American Community Survey data.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102198.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Several of the datasets are restricted access. Will provide non-restricted data upon request.

References

- American Lung Association . State of Tobacco Control Grades; 2017. State of Tobacco Control Grades: California. [Google Scholar]

- Astor R.L., Urman R., Barrington-Trimis J.L., Berhane K., Steinberg J., Cousineau M., Leventhal A.M., Unger J.B., Cruz T., et al. Tobacco Retail Licensing and Youth Product Use. Pediatrics. 2019;143 doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodovsky J.T., Lee D.C., Crosier B.S., Gabrielli J.L., Sargent J.D., Budney A.J. U.S. cannabis legalization and use of vaping and edible products among youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;177:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostean G., Crespi C.M., Vorapharuek P., McCarthy W.J. E-cigarette use among students and e-cigarette specialty retailer presence near schools. Health Place. 2016;42:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.r., 1999. Environments in Developmental Perspective: Theoretical and operational models, in: Friedman, S.L., Wachs, T.D. (Eds.), Measuring environment across the life span: Emerging methods and concepts. American Psychological Association Press, Washington, D.C., pp. 3-28.

- California Tobacco Education and Research Oversight Committee, 2018. New Challenges—New Promise for All: 2018-2020 Master Plan of the California Tobacco Education and Research Oversight Committee, in: (TEROC), C.T.E.a.R.O.C. (Ed.), Sacramento, CA.

- Chan W.C., Leatherdale S.T. Tobacco retailer density surrounding schools and youth smoking behaviour: a multi-level analysis. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2011;9:9. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole A.G., Aleyan S., Leatherdale S.T. Exploring the association between E-cigarette retailer proximity and density to schools and youth E-cigarette use. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019;15 doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo H., Ammerman A., Gordon-Larsen P., Linnan L., Lytle L., Ribisl K.M. Sociodemographic Disparities in Proximity of Schools to Tobacco Outlets and Fast-Food Restaurants. Am. J. Public Health. 2016;106:1556–1562. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan L.J., Lipperman-Kreda S., Abadi M., Grube J.W., Kaner E., Balassone A., Gaidus A. Tobacco outlet density and adolescents’ cigarette smoking: a meta-analysis. Tob. Control. 2019;28:27–33. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth C.L., Carlini B., Dilley J., Guttmannova K., Hajat A. Retail cannabis environment and adolescent use: The role of advertising and retailers near home and school. Health Place. 2022;75 doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2022.102795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B., Gruenewald P.J. Examining the relationship between the physical availability of medical marijuana and marijuana use across fifty California cities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;143:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwon S.H., DeGuzman P.B., Kulbok P.A., Jeong S. Density and Proximity of Licensed Tobacco Retailers and Adolescent Smoking: A Narrative Review. J. Sch. Nurs. 2016;33:18–29. doi: 10.1177/1059840516679710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpin S.B., Brooks-Russell A., Ma M., James K.A., Levinson A.H. Adolescent Marijuana Use and Perceived Ease of Access Before and After Recreational Marijuana Implementation in Colorado. Subst. Use Misuse. 2018;53:451–546. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1334069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L., Feighery E.C., Schleicher N.C., Cowling D.W., Kline R.S., Fortmann S.P. Is adolescent smoking related to the density and proximity of tobacco outlets and retail cigarette advertising near schools? Prev. Med. 2008;47:210–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowitt S.D., Lipperman-Kreda S. How Is Exposure to Tobacco Outlets Within Activity Spaces Associated With Daily Tobacco Use Among Youth? A Mediation Analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020;22:958–966. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau S.E., Tabb L.P., Kioumarsi A., Ataiants J., Iverson E., Wong C.F. Density of Medical Marijuana Dispensaries and Current Marijuana Use among Young Adult Marijuana Users in Los Angeles. Subst. Use Misuse. 2019;54:1862–1874. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2019.1618332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawman H.G. The Pro-Equity Potential of Tobacco Retailer Licensing Regulations in Philadelphia. Am. J. Public Health. 2019;109:427–448. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.G.L., Orlan E.N., Sewell K.B., Ribisl K.M. A new form of nicotine retailers: a systematic review of the sales and marketing practices of vape shops. Tob. Control. 2018;27:e70. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipperman-Kreda S., Grube J.W., Friend K.B. Local Tobacco Policy and Tobacco Outlet Density: Associations With Youth Smoking. J. Adolesc. Health. 2012;50:547–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipperman-Kreda S., Islam S., Wharton K., Finan L.J., Kowitt S.D. Youth tobacco and cannabis use and co-use: Associations with daily exposure to tobacco marketing within activity spaces and by travel patterns. Addict. Behav. 2022;126 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh L., Vaneckova P., Robertson L., Johnson T.O., Doscher C., Raskind I.G., Schleicher N.C., Henriksen L. Association between density and proximity of tobacco retail outlets with smoking: A systematic review of youth studies. Health & Place. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102275. 102275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy W.J., Mistry R., Lu Y., Patel M., Zheng H., Dietsch B. Density of Tobacco Retailers Near Schools: Effects on Tobacco Use Among Students. Am. J. Public Health. 2009;99:2006–2013. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.145128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy K.R., Bibeau D., Steckler A., Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988;15:351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuyts P.A.W., Davies L.E.M., Kunst A.E., Kuipers M.A.G. The Association Between Tobacco Outlet Density and Smoking Among Young People: A Systematic Methodological Review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019;23:239–248. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribisl K.M., Luke D.A., Bohannon D.L., Sorg A.A., Moreland-Russell S. Reducing Disparities in Tobacco Retailer Density by Banning Tobacco Product Sales Near Schools. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016;19:239–244. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Cummins S.E., Zhu S.-H. Medical Marijuana Availability, Price, and Product Variety, and Adolescents' Marijuana Use. J. Adolesc. Health. 2018;63:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siahpush M., Jones P.R., Singh G.K., Timsina L.R., Martin J. Association of availability of tobacco products with socio-economic and racial/ethnic characteristics of neighbourhoods. Public Health. 2010;124:525–559. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver L.D., Naprawa A.Z., Padon A.A. Assessment of Incorporation of Lessons From Tobacco Control in City and County Laws Regulating Legal Marijuana in California. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3:e208393–e208493. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger J.B., Vos R.O., Wu J.S., Hardaway K., Sarain A.Y.L., Soto D.W., Rogers C., Steinberg J. Locations of licensed and unlicensed cannabis retailers in California: A threat to health equity? Prev. Med. Rep. 2020;19 doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.-H., Zhuang, Y.-L., Braden, K., Cole, A., Gamst, A., Wolfson, T., Lee, J., Ruiz, C., Cummins, S., 2019. Results of the Statewide 2017-18 California Student Tobacco Survey Center for Research and Intervention in Tobacco Control (CRITC), University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Several of the datasets are restricted access. Will provide non-restricted data upon request.