Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) EBNA-LP is a latent protein whose function is not fully understood. Recent studies have shown that EBNA-LP may be an important EBNA2 cofactor by enhancing EBNA2 stimulation of the latency C and LMP-1 promoters. To further our understanding of EBNA-LP function, we have introduced a series of mutations into evolutionarily conserved regions and tested the mutant proteins for the ability to enhance EBNA2 stimulation of the latency C and LMP-1 promoters. Three conserved regions (CR1 to CR3) are located in the repeat domains that are essential for the EBNA2 cooperativity function. In addition, three serine residues are also well conserved in the repeat domains. Clustered alanine mutations were introduced into CR1 to CR3, and the conserved serines were also changed to alanine residues in an EBNA-LP with two repeats, which is the minimal protein able to cooperate with EBNA2. Mutations introduced into CR1a had no effect on EBNA-LP function, while mutations introduced into CR1b resulted in EBNA-LP with slightly decreased activity. Mutations in CR1c and CR2 resulted in proteins that no longer localized exclusively to the nucleus and also had no EBNA2 cooperation activity. Mutations introduced into conserved serines S5/71 resulted in proteins with slightly higher activity, while mutations introduced into conserved serines S35/101 or in CR3 (which contains S60/126) resulted in EBNA-LP proteins with substantially reduced activity. The potential karyophilic signals within EBNA-LP CR1c and CR2 were also examined by introducing oligonucleotides encoding these positively charged amino acid groupings into a cytoplasmic test protein, herpes simplex virus ΔIE175, and by examining the intracellular localization of the resulting proteins. This assay identified a strong nuclear localization signal between EBNA-LP amino acids 43 and 50 (109 to 117 in the second W repeat) comprising CR2, while EBNA-LP amino acids 29 to 36 (91 to 98 in the second W repeat) were unable to function independently as a nuclear localization signal. However, a combination of amino acids 29 to 50 resulted in more efficient nuclear localization than with amino acids 43 to 50 alone. These results indicate that EBNA-LP has a bipartite nuclear localization signal and that efficient nuclear localization is essential for EBNA2 cooperativity function. Interestingly, EBNA-LP with only a single repeat localized exclusively to the cytoplasm, providing an explanation for why this isoform has no activity. In addition, two conserved serine residues which are distinct from nuclear import functions are important for EBNA2 cooperativity function.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection is associated with several human malignancies including Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin's disease, nasopharangeal carcinoma, and lymphomas in the immunosuppressed (32). EBV infection of human B lymphocytes also stimulates growth proliferation of human B cells into lymphoblastic cell lines (LCLs) (15). LCLs resemble physiologically activated B cells in morphology and phenotype (15). The ability of EBV to stimulate B-cell growth independent of physiologic stimuli from antigens and T cells is mediated by a subset of viral proteins (15, 24). Uncovering the mechanisms by which these viral proteins function is essential to understanding EBV biology and association with human malignancy and may also yield insight into molecular mechanisms that govern normal physiologic B-cell activation.

Efficient immortalization of B lymphocytes requires expression of only a subset of viral genes (15, 24). These genes include several EBV nuclear antigens (EBNAs) (EBNA1, EBNA2, EBNA3A and -C, and EBNA-LP) and an integral membrane protein, LMP-1. EBNA-LP is the first protein along with EBNA2 made during infection of lymphocytes by EBV (1). Despite a growing body of knowledge about the molecular mechanisms of latent protein functions, the role of EBNA-LP for EBV-induced immortalization remains enigmatic.

EBNA-LP (also referred to as EBNA5 or EBNA4) contains multiple copies of a 66-amino-acid repeat domain encoded by two exons in the IR1 (major internal repeat of EBV) repeats W1 (22 amino acids) and W2 (44 amino acids), followed by a unique 45-amino-acid domain encoded by the Y1 and Y2 exons located within the Bam Y fragment just downstream of the IR1 repeats (4, 35, 38). Genetic studies using recombinant viruses lacking the last two EBNA-LP exons (Y1 and Y2) or a stop codon placed after the first amino acid in Y1 were unable to immortalize lymphocytes unless cocultivated with fibroblast feeder cells (8, 22). While this assay was unable to determine the biochemical mechanism of EBNA-LP function, it gave rise to the hypothesis that EBNA-LP was important but not essential for EBV-induced immortalization. EBNA-LP localizes to the nucleus in distinct foci now recognized as nuclear domain 10 (ND10) bodies or promyelocytic leukemia-associated protein (PML) oncogenic domains (PODs) (14, 30). Several cellular proteins including PML, hsp70, and an antigenically distinct form of RB have been reported to be present in PODs or ND10 bodies (5, 14, 18, 39, 40, 45). Although little is known about the functions of proteins present in the PODs, they appear to be involved in cellular proliferation processes. Immunofluorescence and in vitro binding studies have suggested that EBNA-LP interacts with p53 and RB (41). However, coexpression of EBNA-LP and RB or p53 did not result in any functional consequence upon RB or p53-dependent transcription from reporter plasmids (12). EBNA-LP also interacts with hsp72/hsc73, although the functional consequence of such an interaction is unclear (17, 23). EBNA-LP has also been shown to be phosphorylated on serine residues and to be phosphorylated in greater amounts during the late G2 stage of the cell cycle (16, 30). Both casein kinase II (CKII) and the cyclin-dependent p34cdc2 kinase could also phosphorylate EBNA-LP in vitro (16).

Recent studies have found that while EBNA-LP has little effect on transcription alone, it stimulated EBNA2 activation of the LMP-1 promoter and a regulatory region from the latency BamHI C promoter (Cp) (9, 28). Interestingly, a minimum of two W1/W2 repeats was required for these assays, and the Y1 and Y2 exons were dispensable (9, 28). Consistent with these studies, it has also been shown that introduction of both EBNA2 and EBNA-LP expression plasmids into resting B lymphocytes results in activation of cyclin D2 and progression of these cells from G0 to G1 (37). These data provided direct evidence for an effect of EBNA-LP on cell phenotype.

Genetic analysis of EBNA-LP is difficult because EBNA-LP is derived from several repeated exons in IR1. An alternative approach for elucidating functional domains and their associated cellular cofactors in viral proteins is to focus on regions of the protein that are evolutionarily conserved. Several lymphocryptoviruses (LCVs) have been isolated from nonhuman primates including rhesus macaques (rhesus LCV or cercopithicine herpesvirus 15) and baboons (herpesvirus papio or cercopithicine herpesvirus 12). Our laboratory recently cloned and sequenced the genomic regions encoding EBNA-LP from rhesus and baboon LCVs (29). Alignment of EBNA-LP homologs revealed five conserved regions (CR1 to CR5) (29), three of which (CR1 to CR3) are located within the repeat domains. CR1 and CR3 have been divided into subregions CR1a, -b, and -c and CR3a and -b. In addition, of the six serines in the repeats that are potentially phosphorylated, only three are well conserved. We also isolated a cDNA for the rhesus LCV EBNA-LP and tested its ability to stimulate EBNA2-mediated transactivation of reporter plasmids (29). Both rhesus LCV EBNA-LP and EBV EBNA-LP proved capable of stimulating transcription mediated by an EBNA2 derived from either EBV or the rhesus LCV. Currently, there are no genetic data implicating the EBNA-LP synergy function as being relevant to EBV immortalization. However, retention of this synergistic function between rhesus LCV EBNA-LP and EBNA2 suggests that it is a universal function important for the LCV life cycle.

In this study, we wanted to identify EBNA-LP functional domains required for transcriptional cooperation with EBNA2. Moreover, we wanted to evaluate whether any of the three conserved serine residues that may serve as potential phosphorylation sites in each of the W repeats were important for the EBNA2 cooperativity function. Finally, we wanted to determine why an EBNA-LP with only a single repeat failed to cooperate with EBNA2 (28). To achieve these goals, we have introduced mutations into regions of EBNA-LP that are conserved in several LCV EBNA-LP proteins from humans and nonhuman primates. Mutant EBNA-LP proteins were then assayed for stable expression, nuclear localization, and ability to stimulate EBNA2-mediated transactivation of reporter plasmids in EBV-negative B cells or activation of LMP-1 protein expression in Akata cells. EBNA-LP with one W repeat was assayed in a similar manner. The results from these studies will further advance our understanding of EBNA-LP W repeat region function and provide valuable information toward identification of cellular cofactors that mediate EBNA-LP function(s).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

The Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines DG75 and Akata were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C. HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Transient transfection analysis.

DNA transfections were carried out by a DEAE-dextran method for DG75 cells and electroporation for Akata cells (28, 29). Cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of target and effector plasmids. Total amounts of plasmid DNA for transfections were equalized using SG5 (Stratagene) plasmid DNA. For transfections using reporter plasmids, DG75 cells were used. After transfection, DG75 cells were harvested after 2 days of incubation and lysed with reporter lysis buffer (Promega), and luciferase assays were carried out as previously described (7, 29). Transfection assay results were measured using the proprietary DLR (dual-luciferase reporter) assay system (Promega). Reporter plasmids expressing the firefly luciferase protein were cotransfected with a plasmid expressing the Renilla luciferase, which was used as an internal control as described by the manufacturer. HeLa cells were transfected using Lipofectin (Gibco/BRL) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Akata cells that had been electroporated were incubated for 2 days, and cell extracts were analyzed for LMP-1 induction by immunoblotting as described below.

Plasmids.

EBNA2-responsive reporter plasmids containing eight copies of the 100-bp EBNA2 enhancer from Cp (BamCp8LUC) and the expression plasmid for EBNA-LP (pSG5LP) containing four Bam W repeats have been described previously (9, 20). An EBNA-LP gene containing only two W repeats but retaining the Y1 and Y2 domains was synthesized by PCR using oligonucleotide primers complementary to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the EBNA-LP gene; an EBNA-LP cDNA with seven W repeats was used as a template (38). The 3′ primer also encoded a Flag epitope tag that results in EBNA-LP with Flag fusions at the carboxy terminus. A ladder of PCR products was made under these conditions; bands corresponding to EBNA-LP genes with two W repeats were excised from agarose gels, cloned into the T-Easy T/A cloning vector (Promega), and sequenced (pJT124). The wild-type EBNA-LP gene with two W repeats was then cloned into the SG5 expression vector (pJT125) (Stratagene). A similar plasmid lacking the carboxy-terminal Flag epitope (pPDL396) was also constructed. Mutations were introduced into either the first or second W repeat in pJT125 by PCR mutagenesis as described previously (7). Briefly, the two outside primers were complementary to the 3′ end of the EBNA-LP gene and to the 5′ end in the SG5 vector (just 5′ to the EBNA-LP initiation codon). The mutagenic primer contained either a NotI site which encoded three consecutive alanine residues or a single codon change (GCA) encoding an alanine residue for serine mutations. Final mutagenic PCR products were cloned into the T-Easy vector and sequenced. Clones that contained correctly introduced mutations but without any additional changes were then subcloned into pSG5. EBNA-LP proteins containing mutations in both of the identical conserved regions in each W repeat were generated by replacing the wild-type AvaI fragment in EBNA-LP with mutations in the second W repeat with the AvaI fragment from EBNA-LP genes containing mutations in the first W repeat.

Construction of the herpes simplex virus (HSV) ΔIE175 protein used to detect nuclear localization signals (NLSs) has been described previously (2, 20, 31). Oligonucleotides encoding potential EBNA-LP NLSs were cloned in frame into the unique BglII site in the ΔIE175 plasmid (pGH115).

Western blot analysis.

DG75 cells transfected with plasmids expressing various forms of EBNA-LP were lysed in sample buffer without bromophenol blue, sonicated, and boiled. The samples were quantitated for protein concentration using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay detection kit. Transfected Akata cells were prepared similarly. Equal amounts of protein were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 15% (for EBNA-LP detection) and 7.5% (for LMP-1 and EBNA2 detection) gels and transferred to nitrocellulose. The membranes were blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% nonfat dried milk, and the blots were incubated with the JF186 or anti-Flag M2 (Sigma) monoclonal antibody to detect EBNA-LP proteins, followed by a secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody (Amersham). For transfected Akata cells, LMP-1 was detected using monoclonal antibody S12 (21), followed by a secondary HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Amersham). EBNA2 was detected using monoclonal antibody PE2 (generous gift from Elliott Kieff) directly conjugated with HRP (Pierce). The proteins were then detected by chemiluminescence using a West Pico Supersignal detection kit (Pierce). Specific bands corresponding to EBNA-LP, EBNA2, or LMP-1 were quantitated from the developed X-ray film using a Molecular Dynamics densitometer and ImageQuant analysis software package.

Immunofluorescence assay and antibodies.

HeLa cells were grown on glass coverslips and transfected as described above. After 2 days, transfected cells were washed in PBS and fixed in methanol. Transfected DG75 cells were washed in PBS, and 5 × 104 cells were spun onto glass slides in a Cytospin 3 centrifuge (Shandon), and fixed in methanol. Cells were then rehydrated in PBS containing 10% goat serum (Gibco) and incubated with primary antibody at 37°C for 1 h in PBS with 1% goat serum. For detection of EBNA-LP, an EBNA-LP monoclonal antibody (JF186) directly conjugated with Alexa 486 (Molecular Probes) was used. For detection of ΔIE175, monoclonal antibody 58s was used (2, 20, 31). Slides were then washed and, if necessary, incubated with a secondary goat anti-mouse fluorescein-conjugated IgG antibody (Cappel) at 37°C for 1 h in PBS containing 1% goat serum. The slides were then washed again after incubation with the secondary antibody, and coverslips were mounted with Vectashield solution (Vector Laboratories Inc.). The slides were then observed and photographed with a Zeiss Axiophot microscope.

The JF186 antibody was prepared by ammonium sulfate precipitation from supernatants of JF186 hybridoma cells (6) and purification by protein A-Sepharose chromatography (Pierce). The antibody was then conjugated with Alexa 486 (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The HSV monoclonal antibody 58s was prepared as described previously (2, 20, 31).

RESULTS

Introduction of mutations into conserved regions in the EBNA-LP protein.

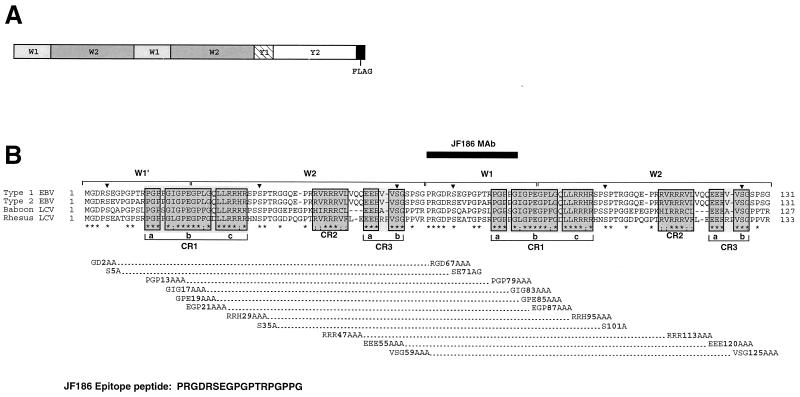

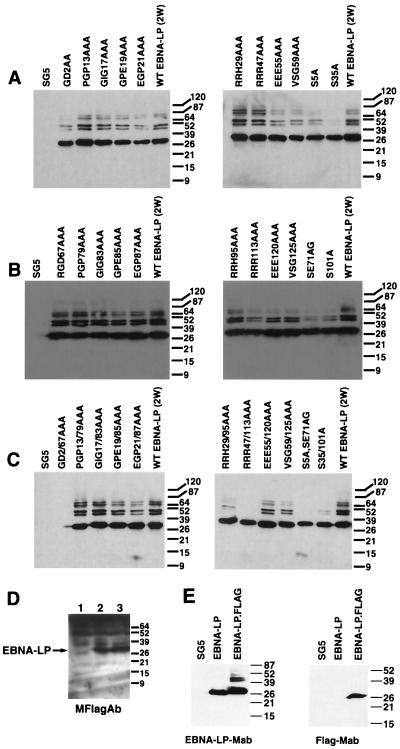

Comparison of the primary amino acid sequences from nonhuman primate LCV EBNA-LP isolates to EBV EBNA-LP revealed that several regions of EBNA-LP were conserved among all species; we designated these regions CR1 to CR5 (Fig. 1) (29). Previous reports have also documented that the EBNA2 cooperativity function was mediated by the W repeats and did not require the unique regions of EBNA-LP encoded by Y1 and Y2 that contain CR4 and CR5 (9, 28). In addition, it also appears that EBNA-LP proteins containing a minimum of two 66-amino-acid repeats encoded by the W1 and W2 exons were required for EBNA2 cooperativity function (28). Since this was the simplest EBNA-LP isoform that retained function, we used it for structure-function analysis (29). We previously demonstrated that at least one nonhuman primate LCV EBNA-LP also stimulated EBNA2-mediated transactivation in cotransfection assays (29). Therefore, it seemed likely that CR1 to CR3 and/or one or more of three conserved serine residues were likely to encompass critical functional domains in EBNA-LP. To determine the role of these conserved amino acid residues, we introduced clustered alanine mutations consisting of three consecutive alanine residues within the conserved regions of EBNA-LP to maximize the efficiency of our analysis (Fig. 1). Three consecutive alanine residues are encoded by nucleotides that comprise a NotI restriction site that facilitated identification of mutant clones, a strategy used previously to identify crucial functional domains in other proteins (10, 11, 46). Since one of the conserved serines is located in CR3b in which a clustered alanine mutation was introduced, we also mutated the other two conserved serines located at positions 5, 71, 35, and 101. We introduced these mutations into either the first or second W repeat or into both repeats (Fig. 1). Since the first three amino acid residues at the amino terminus of the protein and a similar grouping of amino acids at the W1/W2 junction between each repeat were well conserved, we also chose to introduce mutations in this region of EBNA-LP as well. The ability of the mutant EBNA-LP proteins to be expressed was determined by immunoblot analysis from EBV-negative B cells (DG75) that had been transiently transfected with plasmids expressing the mutant EBNA-LP derivatives (Fig. 2). The major detected form of EBNA-LP was approximately 27 to 28 kDa in size, similar to previously published reports (28). Interestingly, several higher-molecular-mass forms of EBNA-LP were also detected at 45, 50, 65, and 70 kDa. All of the EBNA-LP expression clones used in this study had Flag epitope tags engineered on the carboxy-terminal end of EBNA-LP. Comparison to an identical non-Flag epitope-tagged EBNA-LP by immunoblot analysis showed that the unexpectedly high molecular mass forms were not seen, nor were they detected when the anti-Flag monoclonal antibody was used to probe Western blots (Fig. 2E). We interpret this finding to indicate that these forms are due to the Flag epitope tag. A possible explanation for this is that since EBNA-LP has been reported to localize to PML/ND10 bodies, the Flag epitope is modified by ubiquitin homologous proteins (in a process called SUMOylation) (27). These proteins specifically modify lysine residues. The EBNA-LP has no lysine residues, but the Flag epitope has two. The Flag sequence DYKDDDDK also shows some similarity to the proposed human cytomegalovirus IE2 SUMOylation sequence LIKQEDIK (lysine residues are responsible for isopeptide bond formation). The size of the modified forms (about 20 kDa) is consistent both with this type of modification and with the fact that the higher-molecular-weight EBNA-LP forms are also not detected by the Flag monoclonal antibody. The Flag epitope, however, does not appear to alter EBNA-LP function (see Fig. 8D). All of the 33 mutant proteins were expressed to similar levels as wild-type EBNA-LP (wtEBNA-LP) and varied to within 20% of wild-type levels in any given experiment as determined by densitometry from the developed X-ray film. One of the mutants, GD2AA/RGD67AAA, into which substitutions were introduced in the region used to generate the EBNA-LP monoclonal antibody JF186, was not detected with this antibody (Fig. 2C). However, the GD2AA/RGD67AAA mutant was expressed to similar levels as wtEBNA-LP when the Flag monoclonal antibody was used in an immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 1.

Design of mutations introduced into EBNA-LP. (A) General exon structure of the two-repeat EBNA-LP isoform used for mutagenesis studies. All proteins also express the Flag epitope tag at the carboxy terminus. (B) Alignment of the type 1, type 2, baboon LCV, and rhesus LCV EBNA-LP proteins is shown at the top. The alignment shows the relevant parts of a two-W-repeat EBNA-LP protein that was targeted for mutagenesis. The first W1 repeat (W1′) utilizes an alternative splice to generate an ATG initiation codon, while subsequent downstream W1 exons use a different splice acceptor that adds a proline and arginine residue to each repeat (34, 35, 38). Conserved amino acids are indicated by asterisks, and conserved serines are indicated by arrowheads. Conserved regions are boxed in gray. The mutations introduced are shown below the alignment. The amino acids mutated are listed first, followed by the amino acid numbers of the first amino acid that was changed and then of the newly introduced amino acids. The dotted lines connecting the mutations indicate the two mutations that were introduced in both repeats. The peptide used to generate the JF186 monoclonal antibody (MAb) is shown at the bottom, and its location in EBNA-LP is indicated by the black bar above the sequence alignments.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot analysis of EBNA-LP mutants expressed in DG75 cells. (A) Immunoblot of EBNA-LP proteins with mutations introduced in the first W repeat. Cells transfected with vector (SG5) and wtEBNA-LP with two repeats [WT EBNA-LP (2W)] were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Cell lysates were from cells transfected with EBNA-LP mutants indicated above the lanes. (B) Immunoblot of EBNA-LP proteins with mutations introduced in the second W repeat. Controls were as for panel A. (C) Immunoblot of EBNA-LP proteins with identical mutations introduced in both W repeats. Controls were as for panel A. (D) Immunoblot of EBNA-LP proteins using the Flag monoclonal antibody (MFlagAb) to detect EBNA-LP proteins. Cells were transfected with pSG5 (lane 1), wtEBNA-LP (pJT125) (lane 2), and GD2/67AAA (lane 3). (E) Immunoblots comparing EBNA-LP expression with Flag-tagged EBNA-LP in transfected Akata cells. Monoclonal antibodies (Mab) used for EBNA-LP detection are indicated below the blots; cell lysates were from cells transfected with the EBNA-LP versions indicated above the lanes. The molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of proteins from prestained markers are indicated to the right of each blot.

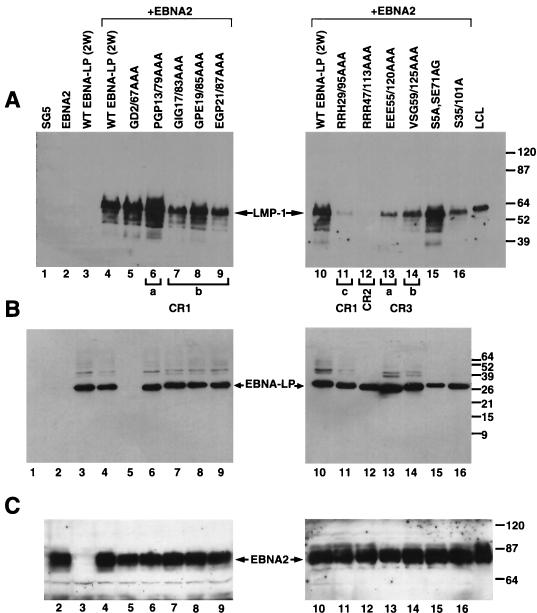

FIG. 8.

Ability of mutant EBNA-LP proteins to enhance EBNA2-mediated transactivation of the LMP-1 gene in Akata cells. (A) Target cells were transfected with pSG5, pSG5-EBNA2, pSG5-wtEBNA-LP (2W), or a combination of pSG5-EBNA2 and a mutant version of pSG5-EBNA-LP. Protein extracts from cells 48 h posttransfection were separated by SDS-PAGE (7.5% gel) and immunoblotted with the LMP-1-specific monoclonal antibody S12. All lanes were loaded with 30 μg of total protein, and molecular weight markers (in thousands) are shown. The final lane was loaded with an extract derived from an LCL (EREB2.5 cells) that expresses LMP-1. (B) Same extracts as in panel A except that immunoblotting was done with the EBNA-LP-specific monoclonal antibody JF186 and proteins were resolved on SDS–15% polyacrylamide gels. The numbers below correspond to the lane numbers in panel A. (C) Same as panel A except that immunoblots were probed with the EBNA2-specific monoclonal antibody PE2 and all lanes were loaded with 90 μg of protein instead of 30 μg. The numbers below correspond to the lane numbers in panels A and B. (D) Target cells were transfected with pSG5, EBNA-LP (pPDL396), and Flag-tagged EBNA-LP (EBNA-LP.Flag; pJT125) with and without pSG5-EBNA2, and LMP-1 induction was detected as described for panel A.

CR2 and -1c comprise a nuclear localization signal.

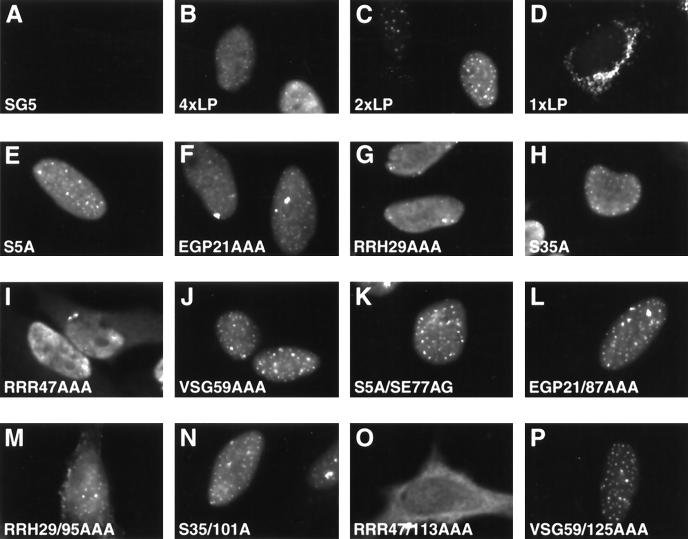

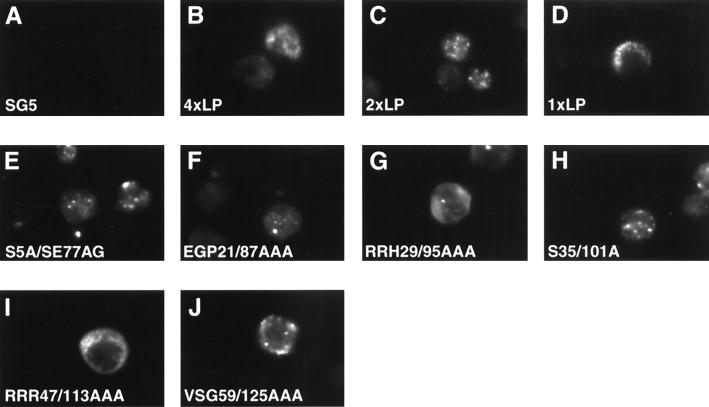

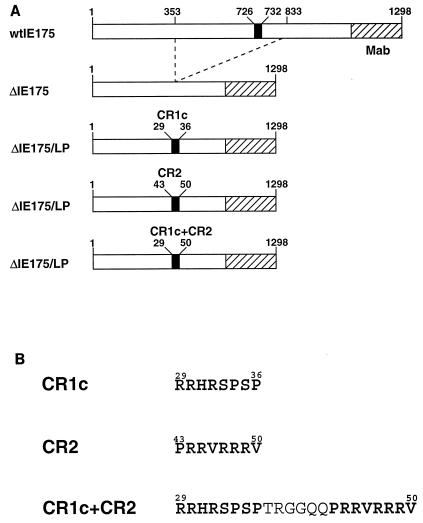

Before embarking on a functional analysis of our mutant panel of proteins, we also wanted to determine if their subcellular localization was altered relative to the wild-type protein. Since differentiation of cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments is easier to visualize in adherent cells than in lymphocytes, which have very small cytoplasm relative to the nucleus, we first expressed our mutant panel of proteins in HeLa cells. Transfected HeLa cells were examined for EBNA-LP expression using the monoclonal antibody JF186. A representative panel of these results is shown in Fig. 3. As expected, wild-type EBNA-LP proteins localized exclusively in the nucleus and displayed diffuse staining with small punctate speckles (Fig. 3B and C). It is unclear whether the speckles are located within PML/ND10 bodies as has been reported for EBNA-LP previously. EBNA-LP with either two or four repeats localized similarly. However, EBNA-LP with only one repeat localized in large punctate spots in the cytoplasm. Addition of a strong NLS from EBNA2 to the carboxy-terminal end of the single-W-repeat EBNA-LP did not change the cytoplasmic localization (data not shown). It is interesting that single-repeat EBNA-LP forms are unable to cooperate with EBNA2 to induce transcription (28). Almost all of the EBNA-LP proteins containing only a single mutation in either the first or second W repeat localized in the nucleus had staining patterns similar to that of wtEBNA-LP (Fig. 3 and data not shown). A representative sample of some of these mutants is shown in Fig. 3 (E to J). However, RRR47AAA (and RRR113AAA [data not shown]) displayed mixed nuclear/cytoplasmic staining (Fig. 3I). This result was not unexpected, since CR2 contains a stretch of positively charged amino acids that resemble a potential NLS. Localization of EBNA-LP containing mutations in both repeats also was similar to that of mutants with mutations in only a single repeat (Fig. 3K, L, N, and P and data not shown). However, EBNA-LP mutants containing mutations in both CR2 regions were localized almost exclusively in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3O). Surprisingly, an EBNA-LP mutant containing mutations in both CR1c regions (RRH29/95AAA) also displayed largely cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 3M). To determine whether subcellular localization of our panel of mutants was similar in a more physiologically relevant cell, we also transfected EBNA-LP expression plasmids into DG75 cells. Immunostaining results similar to those obtained for transfected HeLa cells were observed when EBNA-LP was transiently expressed in DG75 cells. More prominent cytoplasmic staining of the CR1c (RRH29/95AAA) and CR2 (RRR47/113AAA) mutants is also observed in transfected DG75 cells. Moreover, the single-W-repeat EBNA-LP localizes exclusively in the cytoplasm. All of the single and double mutants except the single-W-repeat EBNA-LP and the CR1c and CR2 mutants localized predominantly in the nucleus. A representative sample of EBNA-LP mutants expressed in DG75 cells is shown in Fig. 4. While CR1c also was a candidate NLS due to a stretch of positively charged amino acid residues, it did not appear to confer as strong an effect as CR2. To resolve this issue, we subcloned oligonucleotides that encoded CR1c, CR2, or both into an HSV ΔIE175 expression vector (Fig. 5). The HSV ΔIE175 protein lacks its natural karyophilic signal, and the in-frame introduction of an oligonucleotide encoding a functional signal results in the relocation of the ΔIE175 protein from the cytoplasmic to the nuclear compartment. This vector has been used to identify nuclear localization motifs in the EBNA1, EBNA2, and cytomegalovirus IE2 proteins (2, 20, 31).

FIG. 3.

Subcellular localization of EBNA-LP mutants in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant EBNA-LP expression plasmids. The cells were fixed, and EBNA-LP expression was detected by the EBNA-LP monoclonal antibody JF186 directly conjugated with Alexa 488. Cells were then visualized with a Zeiss Axiotroph microscope. (A to D) Staining patterns of cells expressing vector alone (A) or EBNA-LP with four (B), two (C), or one (D) W repeat; (E to P) expression of other EBNA-LP mutants, as indicated.

FIG. 4.

Subcellular localization of EBNA-LP mutants in DG75 cells. DG75 cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant EBNA-LP expression plasmids. Other details are as for Fig. 3.

FIG. 5.

Construction of plasmids to test for EBNA-LP NLSs. (A) Schematic of HSV ΔIE175 proteins with insertions of potential EBNA-LP NLSs. The black box on the top bar indicates the location of the endogenous NLS; each stippled box indicates the approximate region recognized by monoclonal antibody (Mab) 58s. The dashed lines from the top bar indicate the region of IE175 that was deleted to create ΔIE175 that localizes in the cytoplasm. The bars below show different plasmids generated by insertion of oligonucleotides encoding potential karyophilic signal sequences from EBNA-LP. The numbers indicate the amino acid numbers (from the first repeat) of EBNA-LP sequences inserted into ΔIE175. (B) Amino acid sequence of the CR1c, CR2, and combined CR1c-CR2 sequences that were tested.

HeLa cells were transfected with HSV ΔIE175 and plasmids containing EBNA-LP inserts, and the intracellular locations of the expressed proteins were examined in an immunofluorescence assay using an anti-IE175 monoclonal antibody. Wild-type IE175 protein was localized exclusively in the nucleus of positively staining cells, while the ΔIE175 protein was found in the cytoplasm of positively staining cells (Fig. 6A and B). Introduction of EBNA-LP codons 29 to 36 (CR1c) into the ΔIE175 vector resulted in none of the positively staining cells showing nuclear localization (Fig. 6C). Introduction of tandemly repeated copies of CR1c into ΔIE175 also failed to confer nuclear localization of this protein (data not shown). In contrast, introduction of EBNA-LP codons 43 to 50 (CR2) resulted in almost 70% of the positively staining cells showing exclusive nuclear localization and 30% giving a mixed pattern in which both nucleus and cytoplasm were stained but nuclear staining was the most intense (Fig. 6D and E). Introduction of tandemly repeated CR2-encoding sequences into ΔIE175 resulted in slightly higher numbers of cells displaying exclusively nuclear staining but was never as efficient as ΔIE175 proteins with CR1c and CR2 sequences together (see below; also data not shown). After introduction of EBNA-LP codons 29 to 50 (CR1c plus CR2) into ΔIE175, almost all (<90%) of the positively staining cells showed exclusively nuclear staining. These data are also consistent with mutations in the EBNA-LP protein that disrupt CR1c and CR2. Mutants RRR47AAA and RR113AAA (CR2) had the most dramatic effects on disruption of EBNA-LP nuclear localization either in individual W repeats or when both repeats were mutated. EBNA-LP mutants RRH29AAA and RRH95AAA, however, had little effect unless both mutations were introduced into EBNA-LP. We interpret this finding to indicate that the EBNA-LP sequence PRRVRRRV (CR2) functions as a strong NLS but requires additional sequences from CR1c to mediate efficient nuclear compartmentalization. In addition, the sequence RRHRSPSP (CR1c), while unable to function by itself as an NLS in this system, provides a helper function for the signal in CR2 since the combination of both signals resulted in a much higher efficiency of chimeric ΔIE175 proteins (containing codons 29 to 50) localizing in the nuclear compartment.

FIG. 6.

Identification of NLSs in EBNA-LP. Immunofluorescence images show HeLa cells transfected with ΔIE175 chimeric test plasmids. (A) Wild-type HSV IE175 protein (pGH114); (B) ΔIE175 protein (pGH115); (C) ΔIE175 expressing EBNA-LP amino acids 29 to 36 (CR1c); (D) ΔIE175 expressing EBNA-LP amino acids 43 to 50 (CR2); (E) same as panel D; (F) ΔIE175 expressing EBNA-LP amino acids 29 to 50 (CR1c plus CR2). The IE175 polypeptide was detected by indirect immunofluorescence with monoclonal antibody 58s and a fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antiserum.

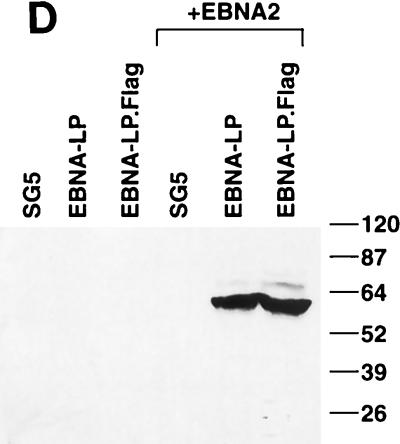

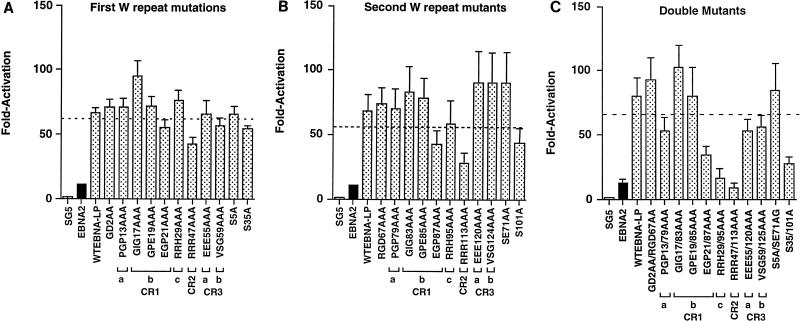

Contribution of CR1 to CR3 for EBNA-LP function.

EBNA-LP proteins containing mutations in a single W repeat or in both repeat regions were tested for the ability to cooperate with EBNA2 in transient cotransfection assays. All but four EBNA-LP mutant proteins containing mutations in the first W repeat stimulated EBNA2 transactivation of BamCp8LUC an average of five- to sevenfold above that for EBNA2 alone (Fig. 7A). One of the mutants, RRR47AAA, which is in CR2, had a statistically significant decrease in activity compared to wtEBNA-LP. This result is most likely due to the fact that CR2 functions as an NLS, and this protein does not localize to the nucleus efficiently (Fig. 3I). It is interesting that three other mutants, EGP21AAA, VSG59AAA, and S35A, have a small effect on reducing EBNA-LP activity. All of these mutant proteins efficiently localize to the nucleus (Fig. 3F, J, and K, respectively). When identical mutations were introduced into the second W repeat, a pattern of EBNA-LP activity similar to that observed with EBNA-LP containing mutations in the first W repeat was also observed, although the VSG124AAA mutation was within wild-type activity (Fig. 7B). It is unclear whether the first repeat has a more dominant effect than the second repeat, but it may do so for some domains. EBNA-LP proteins containing identical mutations in each W repeat were then analyzed for function. In general, those mutations that had an effect on EBNA-LP function when present in only a single W repeat had a more significant effect when present in both W repeats. The CR2 mutant RRR47/113AAA had no activity relative to wtEBNA-LP, while both EGP21/87AAA and S35/101AAA retained only 32 and 23% of wtEBNA-LP activity (Fig. 7C). Surprisingly, RRH29/95AAA had no ability to stimulate EBNA2 activation of BamCp8LUC. While the other mutants appeared to display an additive effect when combined, RRH29AAA and RRH95AAA had activity similar to that of wtEBNA-LP. Immunofluorescence analysis, however, indicates that RRH29/95AAA also localizes aberrantly compared to wtEBNA-LP and appears to localize predominantly in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3M). Compared to the rest of the EBNA-LP mutants and wtEBNA-LP, efficient nuclear localization appears to be an important prerequisite for the EBNA2 cooperativity function. Three other mutants, PGP13/79AAA, EEE55/120AAA, and VSG59/125AAA, also appear to have moderately reduced activity. Since these mutants localize efficiently to the nucleus, it is likely that EBNA2 cooperativity function may consist of multiple domains which are located in CR1a and -b and also require potential serine phosphorylation at positions 35/101 and 60/126. While not statistically significant, we also observed that some of the mutants tended to have an average higher activity than wtEBNA-LP. These mutants congregated toward the W1 exon and include S5A/SE71AG andGD2AA/RGD67AAA. A possible role for negative regulation of EBNA-LP activity by phosphorylation would be consistent with these results.

FIG. 7.

Ability of mutant EBNA-LP proteins to enhance EBNA2-mediated transactivation of the BamCp8LUC reporter gene. (A) Plasmids expressing vector only (pSG5), EBNA2 only (black bar), or EBNA2 and specific EBNA-LP mutants as indicated (shaded bars) were transfected into DG75 cells. The reporter plasmid was BamCp8LUC (see Materials and Methods for details). The presence or absence of EBNA-LP or EBNA2 plasmids is indicated below the graph. Fold activation is indicated on the left. Standard errors of the means are indicated by T bars.

Since mutations in a single repeat appeared to be compensated for by the other repeat, we decided that the double mutants were the most informative for identifying important EBNA-LP domains. To confirm the results obtained in the transient transfection analysis, we tested the panel of double mutants for the ability to induce LMP-1 in the Akata cell assay. In this assay, transfection of EBNA2 into Akata cells resulted in no detectable induction of the LMP-1 protein. However, cotransfection of EBNA2 with EBNA-LP resulted in a significant induction of LMP-1 (Fig. 8A). In addition, non-epitope-tagged versions of EBNA-LP induced LMP-1 to similar levels as Flag epitope-tagged EBNA-LP proteins (Fig. 8D). Similar to previously published results, the level of EBNA2 and EBNA-LP proteins varies within twofold from wild-type levels in each transfection assay (Fig. 8B and C) (28). Like the Cp reporter assays, RRH29/95AAA and RRR47/113AAA had low to undetectable ability to induce LMP-1 when coexpressed with EBNA2 (Fig. 8A). Likewise, S35/101A and the CR3a and CR3b mutants had markedly reduced activity, although the severity of reduction for the CR3 mutants was somewhat more than that observed for Cp activation. Mutations in CR1a, however, gave results that contrasted with those observed in the Cp activation assay. While EGP21/87AAA had diminished activity in both assays, PGP13/79AAA tended to be more active in the Akata cell assay but slightly less active in the Cp activation assay. Both assays, however, showed an overall trend toward increased activity for the S5/71A and GD2AA/RGD67AAA EBNA-LP mutants. A comparison of mutant EBNA-LP activities for the two assays is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Activation of Cp and LMP-1

| Construct | Relative activationa

|

|

|---|---|---|

| BamC8xLUC | LMP-1 | |

| wtEBNA-LP | 100 | ++++ |

| GD2AA/RGD67AAAb | 118 | +++++ |

| PGP13/79AAAc | 60 | +++++ |

| GIG17/83AAAc | 134 | ++++ |

| GPE19/85AAA | 100 | ++++ |

| EGP21/87AAAd | 32 | +++ |

| RRH29/95AAAd | 6 | +/− |

| RRR47/113AAAd | <1 | NDe |

| EEE55/120AAAd | 60 | + |

| VSG59/125AAAd | 63 | + |

| S5A/SE71AGb | 106 | +++++ |

| S35/101Ad | 23 | + |

Relative level of Cp or LMP-1 activation by EBNA2 and EBNA-LP compared to activation using EBNA2 and mutant versions of EBNA-LP. Cp activation levels were determined from Fig. 7. LMP-1 levels are representative of three identically performed experiments including data from Fig. 8.

Consistently higher induction of Cp or LMP-1 than with wtEBNA-LP.

Slightly discrepant results observed between the reporter plasmid assay in DG75 cells and LMP-1 induction in Akata cells.

Consistently lower induction of Cp or LMP-1 than with wtEBNA-LP.

ND, not detected.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that EBNA-LP has a bipartite NLS located in CR1c and CR2. Efficient nuclear localization mediated by these domains also appears to be an important function for EBNA-LP activity. EBNA-LP conserved serine residues located in the W2 exon are important for EBNA-LP function and suggest an important role for phosphorylation in positively regulating EBNA-LP activity. EBNA-LP may also be negatively regulated by the other conserved serine residue in the W1 exon. Finally, EBNA-LP with only a single repeat is nonfunctional because it localizes in the cytoplasm. These results identify distinct regions in EBNA-LP that mediate its transcriptional activation function and mediate efficient nuclear import.

Although inspection of sequences conserved in EBNA-LP indicates that the positively charged amino acid clusters in CR1c and CR2 might function as karyophilic signals, surprisingly both appear to be required for efficient nuclear import. A question that arises from our results concerns why EBNA-LP has two separate domains that mediate nuclear import. A simple explanation may be that interactions with cellular proteins result in steric hindrance of one or more of the karyophilic signals in EBNA-LP and some redundancy is necessary to ensure proper nuclear import. Alternatively, as much of the W2 repeat domain appears to be dedicated to nuclear import functions, EBNA-LP nuclear import may be highly regulated. It is interesting that both CR1c and CR2 are located adjacent to key phosphorylation sites in EBNA-LP. A consensus p34cdc2 phosphorylation site ([S/T]PX[K/R]) flanks CR1c (SPTR) and can be phosphorylated by p34cdc2 kinase in vitro. CR2 precedes a conserved serine in CR3 that also appears to be important for EBNA-LP function. Previous studies have shown that nucleocytoplasmic transport can be regulated through phosphorylation (13, 26, 33, 42, 43). The simian virus 40 T-antigen NLS is flanked by a CKII site that greatly enhances the rate of nuclear import. In contrast, the SW15 NLS and simian virus 40 T antigen can be phosphorylated by p34cdc2, and this results in inhibition of nuclear entry (13, 26, 43). Thus, nuclear import of SW15 appears to be cell cycle regulated. It is interesting that nucleoplasmin, human p53, mouse c-Abl and c-Myc, and polyomavirus T antigen also contain either CKII or p34cdc2 in regions flanking their NLSs (43). It is tempting to speculate that the phosphorylation sites adjacent to the two EBNA-LP NLSs may regulate nuclear import of EBNA-LP, possibly in a cell cycle-dependent manner. Since our studies were carried out in asynchronously growing cells, we are unable to determine at this time whether EBNA-LP shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm or if localization is cell cycle regulated. It should, however, be noted that we have observed some cytoplasmic staining in a minority of cells expressing wtEBNA-LP (data not shown). A systematic investigation of EBNA-LP localization coupled to cell cycle analysis or use of interspecies heterokaryon assays should resolve these issues. Based on results of this study, we might also speculate that EBNA-LP may shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm and that this may be an important requirement for EBNA-LP function. It is useful to recall that several herpesvirus proteins that regulate gene expression such as ICP27, EBV Mta, and human herpesvirus 8 ORF57 also shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm (3, 25, 36). We would also speculate that in line with these facts is the observation that the EBNA-LP isoform with a single repeat localizes exclusively in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3 and 4). While this could be the result of aberrant conformation, it may also be that EBNA-LP possesses a cytoplasmic retention domain that requires multiple copies of an NLS to override its effect.

Finally, EBNA-LP has been observed previously by immunofluorescence microscopy to be concentrated in a few small nuclear granules frequently in a curved array similar to structures revealed by in situ hybridization of EBV IR1 DNA (15, 19, 30, 44). This has led to the proposal that EBNA-LP may play a role in EBV RNA transcription or processing (15). Consistent with this idea, it will be interesting to see if EBNA-LP nuclear speckles colocalize with splicing factors such as SC-35 as has been reported for the EBV Mta protein. Perhaps like the case for productive lytic infection, latently expressed viral regulatory proteins such as EBNA2 require additional virus-encoded transcriptional regulatory functions related to mRNA synthesis and processing to mediate their full effect.

Although EBNA-LP phosphorylation may regulate some aspects of nuclear transport, it may also regulate specific independent functions. Aside from one mutation in CR1b, no conserved regions in addition to serines 35/101 and (in CR3) 59/125 appear to be important for EBNA-LP function. It would seem likely that EBNA-LP exerts its effects through interaction with cellular cofactors other than those that mediate protein localization. Therefore, a role for phosphorylation may include altering conformation of EBNA-LP to enhance affinity for a cellular cofactor or alternatively may result in recruitment of a kinase(s) that mediates EBNA-LP function.

Our study is the first to attempt a systematic approach to identifying important EBNA-LP functional domains. The targeting of conserved regions provided a useful framework to begin this analysis and resulted in identification of NLS sequences and important serine residues required for EBNA-LP function. While none of our targeted mutations outside of NLS sequences resulted in null mutants, our results will now allow us to combine multiple specific mutations into EBNA-LP that will result in destruction of domains required for EBNA-LP ligand interactions. The mutant proteins will not only further refine our understanding of EBNA-LP functional domains but also be an invaluable tool for identification of cellular factors that mediate EBNA-LP function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant R29 CA69437 and ACS grant RPG-00-099-01.

We thank Hank Adams and Frank Herbert in the Baylor cell biology microscopy core facility for their assistance with IFA experiments and use of the Zeiss Axiophot microscope. We also thank Samuel H. Speck for the IB4WY-1 cDNA, Elliott Kieff for the SG5LP expression plasmid, and Elliott Kieff and David Thorley-Lawson for the S12 hybridoma cells and purified S12 monoclonal antibody.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfieri C, Birkenbach M, Kieff E. Early events in Epstein-Barr virus infection of human B lymphocytes. Virology. 1991;181:595–608. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90893-g. . (Erratum, 185:946.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambinder R F, Mullen M A, Chang Y N, Hayward G S, Hayward S D. Functional domains of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA-1. J Virol. 1991;65:1466–1478. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1466-1478.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bello L J, Davison A J, Glenn M A, Whitehouse A, Rethmeier N, Schulz T F, Barklie Clements J. The human herpesvirus-8 ORF 57 gene and its properties. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:3207–3215. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-12-3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dillner J, Kallin B, Alexander H, Ernberg I, Uno M, Ono Y, Klein G, Lerner R A. An Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-determined nuclear antigen (EBNA5) partly encoded by the transformation-associated Bam WYH region of EBV DNA: preferential expression in lymphoblastoid cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:6641–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyck J A, Maul G G, Miller W H, Jr, Chen J D, Kakizuka A, Evans R M. A novel macromolecular structure is a taret of the promyelocyte-retinoic acid receptor oncoprotein. Cell. 1994;76:333–343. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finke J, Rowe M, Kallin B, Ernberg I, Rosen A, Dillner J, Klein G. Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 5 (EBNA-5) detect multiple protein species in Burkitt's lymphoma and lymphoblastoid cell lines. J Virol. 1987;61:3870–3878. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3870-3878.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuentes-Panana E M, Swaminathan S, Ling P D. Transcriptional activation signals found in the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latency C promoter are conserved in the latency C promoter sequences from baboon and rhesus monkey EBV-like lymphocryptoviruses (cercopithicine herpesviruses 12 and 15) J Virol. 1999;73:826–833. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.826-833.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammerschmidt W, Sugden B. Genetic analysis of immortalizing functions of Epstein-Barr virus in human B lymphocytes. Nature. 1989;340:393–397. doi: 10.1038/340393a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harada S, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein LP stimulates EBNA-2 acidic domain-mediated transcriptional activation. J Virol. 1997;71:6611–6618. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6611-6618.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsieh J J-D, Hayward S D. Masking of the CBF1/RBPJ kappa transcriptional repression domain by Epstein-Barr virus EBNA2. Science. 1995;268:560–563. doi: 10.1126/science.7725102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsieh J J-D, Henkel T, Salmon P, Robey E, Peterson M G, Hayward S D. Truncated mammalian Notch 1 activates CBF1/RBPJκ-repressed genes by a mechanism resembling that of Epstein-Barr virus EBNA2. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:952–959. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inman G J, Farrell P J. Epstein-Barr virus EBNA-LP and transcription regulation properties of pRB, p107 and p53 in transfection assays. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2141–2149. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-9-2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jans D A, Ackermann M J, Bischoff J R, Beach D H, Peters R. p34cdc2-mediated phosphorylation at T124 inhibits nuclear import of SV-40 T antigen proteins. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1203–1212. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.5.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang W Q, Szekely L, Wendel-Hansen V, Ringertz N, Klein G, Rosen A. Co-localization of the retinoblastoma protein and the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen EBNA-5. Exp Cell Res. 1991;197:314–318. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90438-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus and its replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 107–172. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitay M K, Rowe D T. Cell cycle stage-specific phosphorylation of the Epstein-Barr virus immortalization protein EBNA-LP. J Virol. 1996;70:7885–7893. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7885-7893.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitay M K, Rowe D T. Protein-protein interactions between Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-LP and cellular gene products: binding of 70-kilodalton heat shock proteins. Virology. 1996;220:91–99. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koken M H, Puvion-Dutilleul F, Guillemin M C, Viron A, Linares-Cruz G, Stuurman N, de Jong L, Szostecki C, Calvo F, Chomienne C, et al. The t(15;17) translocation alters a nuclear body in a retinoic acid-reversible fashion. EMBO J. 1994;13:1073–1083. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence J B, Singer R H, Marselle L M. Highly localized tracks of specific transcripts within interphase nuclei visualized by in situ hybridization. Cell. 1989;57:493–502. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90924-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ling P D, Ryon J J, Hayward S D. EBNA-2 of herpesvirus papio diverges significantly from the type A and type B EBNA-2 proteins of Epstein-Barr virus but retains an efficient transactivation domain with a conserved hydrophobic motif. J Virol. 1993;67:2990–3003. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.2990-3003.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mann K P, Staunton D, Thorley-Lawson D A. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded protein found in plasma membranes of transformed cells. J Virol. 1985;55:710–720. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.3.710-720.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mannick J B, Cohen J I, Birkenbach M, Marchini A, Kieff E. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein encoded by the leader of the EBNA RNAs is important in B-lymphocyte transformation. J Virol. 1991;65:6826–6837. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6826-6837.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mannick J B, Tong X, Hemnes A, Kieff E. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen leader protein associates with hsp72/hsc73. J Virol. 1995;69:8169–8172. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.8169-8172.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mark W, Sugden B. Transformation of lymphocytes by Epstein-Barr virus requires only one-fourth of the viral genome. Virology. 1982;122:431–433. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mears W E, Rice S A. The herpes simplex virus immediate-early protein ICP27 shuttles between nucleus and cytoplasm. Virology. 1998;242:128–137. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.9006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moll T, Tebb G, Surana U, Robitsch H, Nasmyth K. The role of phosphorylation and the CDC28 protein kinase in cell cycle-regulated nuclear import of the S. cerevisiae transcription factor SWI5. Cell. 1991;66:743–758. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90118-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller S, Dejean A. Viral immediate-early proteins abrogate the modification by SUMO-1 of PML and Sp100 proteins, correlating with nuclear body disruption. J Virol. 1999;73:5137–5143. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.5137-5143.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nitsche F, Bell A, Rickinson A. Epstein-Barr virus leader protein enhances EBNA-2-mediated transactivation of latent membrane protein 1 expression: a role for the W1W2 repeat domain. J Virol. 1997;71:6619–6628. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6619-6628.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng R, Gordadze A V, Fuentes Panana E M, Wang F, Zong J, Hayward G S, Tan J, Ling P D. Sequence and functional analysis of EBNA-LP and EBNA2 proteins from nonhuman primate lymphocryptoviruses. J Virol. 2000;74:379–389. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.379-389.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petti L, Sample C, Kieff E. Subnuclear localization and phosphorylation of Epstein-Barr virus latent infection nuclear proteins. Virology. 1990;176:563–574. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90027-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pizzorno M C, Mullen M A, Chang Y N, Hayward G S. The functionally active IE2 immediate-early regulatory protein of human cytomegalovirus is an 80-kilodalton polypeptide that contains two distinct activator domains and a duplicated nuclear localization signal. J Virol. 1991;65:3839–3852. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3839-3852.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rickinson A B, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 2397–2446. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rihs H P, Jans D A, Fan H, Peters R. The rate of nuclear cytoplasmic protein transport is determined by the casein kinase II site flanking the nuclear localization sequence of the SV40 T-antigen. EMBO J. 1991;10:633–639. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07991.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogers R P, Woisetschlaeger M, Speck S H. Alternative splicing dictates translational start in Epstein-Barr virus transcripts. EMBO J. 1990;9:2273–2277. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07398.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sample J, Hummel M, Braun D, Birkenbach M, Kieff E. Nucleotide sequences of mRNAs encoding Epstein-Barr virus nuclear proteins: a probable transcriptional initiation site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5096–5100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Semmes O J, Chen L, Sarisky R T, Gao Z, Zhong L, Hayward S D. Mta has properties of an RNA export protein and increases cytoplasmic accumulation of Epstein-Barr virus replication gene mRNA. J Virol. 1998;72:9526–9534. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9526-9534.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sinclair A J, Palmero I, Peters G, Farrell P J. EBNA-2 and EBNA-LP cooperate to cause G0 to G1 transition during immortalization of resting human B lymphocytes by Epstein-Barr virus. EMBO J. 1994;13:3321–3328. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Speck S H, Pfitzner A, Strominger J L. An Epstein-Barr virus transcript from a latently infected, growth-transformed B-cell line encodes a highly repetitive polypeptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9298–9302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szekely L, Jiang W Q, Pokrovskaja K, Wiman K G, Klein G, Ringertz N. Reversible nucleolar translocation of Epstein-Barr virus-encoded EBNA-5 and hsp70 proteins after exposure to heat shock or cell density congestion. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2423–2432. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-10-2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szekely L, Pokrovskaja K, Jiang W Q, de The H, Ringertz N, Klein G. The Epstein-Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen EBNA-5 accumulates in PML-containing bodies. J Virol. 1996;70:2562–2568. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2562-2568.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szekely L, Selivanova G, Magnusson K P, Klein G, Wiman K G. EBNA-5, an Epstein-Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen, binds to the retinoblastoma and p53 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5455–5459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vancurova I, Paine T M, Lou W, Paine P L. Nucleoplasmin associates with and is phosphorylated by casein kinase II. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:779–787. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.2.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vandromme M, Gauthier-Rouviere C, Lamb N, Fernandez A. Regulation of transcription factor localization: fine-tuning of gene expression. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang F, Petti L, Braun D, Seung S, Kieff E. A bicistronic Epstein-Barr virus mRNA encodes two nuclear proteins in latently infected, growth-transformed lymphocytes. J Virol. 1987;61:945–954. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.4.945-954.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weis K, Rambaud S, Lavau C, Jansen J, Carvalho T, Carmo-Fonseca M, Lamond A, Dejean A. Retinoic acid regulates aberrant nuclear localization of PML-RAR alpha in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Cell. 1994;76:345–356. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou S, Fujimuro M, Hsieh J J, Chen L, Hayward S D. A role for SKIP in EBNA2 activation of CBF1-repressed promoters. J Virol. 2000;74:1939–1947. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1939-1947.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]