Abstract

Background:

Alongside the need to develop more effective and less toxic immunosuppression, the shortage of human organs available for organ transplantation is one of the major hurdles facing the field. Research into xenotransplantation, as an alternative source of organs, has unveiled formidable challenges. Porcine lungs perfused with human blood rapidly sequester the majority of circulating neutrophils and platelets, which leads to inflammation and organ failure within hours, and is not significantly attenuated by genetic modifications to the pig targeted to diminish antibody binding and complement and coagulation cascade activation.

Methods:

Here, we model the interaction of freshly isolated human leukocytes with xenotransplanted vasculature under physiologic flow conditions using microfluidic channels coated with porcine endothelial cells. Both isolated human neutrophils and whole human blood were perfused over transgenic pig aortic endothelial cells that had been activated with rhTNF-α or rhIL-4 using the BioFlux system. Novel compounds GMI-1271 and rPSGL1.Fc were tested as E- and P- selectin antagonists, respectively. Cellular adhesion and rolling events were tracked using FIJI (imageJ).

Results:

Porcine endothelium activated with either rhTNF-α or rhIL-4 expressed high amounts of selectins, to which isolated human neutrophils readily rolled and tethered. Both E-and P-selectin antagonism significantly reduced the number of neutrophils rolling and rolling distance in a dose-dependent manner, with near total inhibition at higher doses (P < .001). Similarly, with whole human blood, selectin blocking compounds exhibited dose-dependent inhibition of prevalent leukocyte adhesion and severe endothelial injury (Untreated: 394 ± 97 PMNs/hpf, 57 ± 6% loss EC; GMI1271+rPSGL1.Fc: 23 ± 9 PMNs/hpf, 8 ± 6% loss EC P < .01).

Conclusions:

Selectin blockade may be useful as part of an integrated strategy to prevent neutrophil-mediated organ xenograft injury, especially during the early time points following reperfusion.

Keywords: CD62, endothelium, neutrophil, selectin, xenotransplantation

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Although significant advances in human organ transplantation have saved thousands of lives, many people remain on waiting lists, despite increasing use of “expanded criteria” organs. Xenotransplantation, the transplantation of organs across species, would likely to solve the organ shortage and greatly reduce the substantial waiting list morbidity and mortality that are associated with the current allocation system. Although major advances in immunology, molecular biology, genetic engineering, and cloning of large mammals have catalyzed great progress in the field, obstacles remain to clinical application.

Despite knockout of the porcine Gal 1,3 aGal carbohydrate antigen, which is the dominant target of preformed human anti- pig “natural” antibodies, and additional expression of human proteins that regulate complement, coagulation, and inflammation, significant dysfunction occurs in pig lungs perfused with human blood or transplanted into non- human primates. Although survival has recently been prolonged to almost 1 year1 for porcine kidneys in rhesus macaques, to more than 2.5 years for heterotopic hearts in baboons,2 and to almost 1 month for orthotopic livers in baboons,3 survival of baboons that receive a single pig lung transplant has been limited to barely over a week (our lab, unpublished data). The reasons for the lung’s particular vulnerability to injury are incompletely understood. One leading hypothesis posits that the lung’s anatomy—large capillary bed with only a thin vascular wall separating blood from the atmosphere—renders the lung extremely sensitive to the consequences of inflammation.

During ex vivo perfusion of porcine lungs with human blood, a large majority of platelets and leukocytes are sequestered within the lung within the first thirty minutes. Our working model assumes that activation of these human blood cells leads to release of procoagulant molecules, and elaboration of an array of proinflammatory cytokines. In response to cytokine elaboration and other proinflammatory- activating events, blood leukocytes and tissue- resident macrophages within the lung all contribute to cause endothelial dysfunction (“endotheliopathy”) and lead to a vicious cycle of further recruitment of platelets and immune cells, and loss of vascular barrier function. Local loss of vascular barrier integrity in the lung results in airway flooding, ventilation/perfusion mismatch, and failure of gas transport function, phenomena not readily apparent in other organ xenografts. Methods to prevent the initial sequestration of leukocytes (and other formed blood elements, such as monocytes and platelets) could potentially abort or significantly attenuate the cascade of events that contribute significantly to endothelial injury, and to early lung failure.

The selectins (CD62) are a family of cellular adhesion molecules which span the cell membrane and bind to complex sugar (carbohydrate) motifs; although not limited to this role, the selectins are heavily involved in platelet and leukocyte adhesion under flow conditions.4,5 There are three known types: L-selectin, expressed on most leukocytes; P-selectin, expressed on platelets and endothelial cells; and E-selectin, which is also expressed on the endothelium. Leukocyte adhesion receptor-ligand pairing is relatively preserved in pig to human xenotransplantation models and has been prevented by blocking antibodies.6 Additionally, antibodies to human P-selectin or PSGL-1 (the natural ligand for P-selectin, expressed on leukocytes and endothelial cells) have recently been shown to prevent expression of tissue factor on human platelets incubated with porcine endothelial cells.7 In spite of these findings, the role of selectin antagonism in xenotransplantation has remained unclear due to the lack of non-antibody reagents. Recently, novel selectin antagonists developed by GlycoMimetics, Inc (GMI) have been shown to improve blood flow in sickle cell models using murine microvasculature8 as well as enhance neutrophil recovery and prevent mucositis in mice undergoing chemotherapy.9

Based on their dominant role in leukocyte trafficking events in multiple models of acute lung injury and in other models of inflammation,4,5 and the high degree of binding region sequence conservation across species, we hypothesized that interfering in selectin- mediated cell interaction pathways using novel compounds might reduce neutrophil rolling and adhesion, and attenuate associated endothelial damage in physiologic ex vivo models of lung xenograft injury.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Cytokine profiling

Plasma levels of pre- and post-perfusion human cytokines including TNF-α and IL-4 were measured in 56 ex vivo experiments using Luminex profiling (Cytokine 10-Plex Human Panel, cat# LHC0001M). Histamine levels from 39 lung perfusions were measured by ELISA (ELISA kit; Li StarFish, Cernusco, Italy). Data from all experiments were pooled and analyzed as fold increase from baseline measurements.

2.2 |. Cell culture

Primary pig aortic endothelial cells (PAECs) with transgenic expression of human complement regulatory protein human CD46 and knockout of the α1,3 galactosyl transferase enzyme (GalTKO.hCD46) were isolated from pig aortas and grown in culture medium (50 cc heat-inactivated FBS [Cat#12306C], 1.5 mL gentamicin 50 mg/mL [Cat#15750–060], 50 μL Fungizone 250 μg/mL [Cat#15295–017], 450 cc DMEM 1× +1 g/L D-glucose, L-glutamine, 110 mg/L sodium pyruvate [Cat#11885–084]). Cells were used at 80%−95% confluence after four to six passages. The endothelial cell phenotype was assessed by expression of pig CD31 (Serotec mca1746f) using a BDVerse flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and FlowJo software for analysis.

2.3 |. Surface molecule expression

PAECs were grown in monolayers and exposed to one of the following stimuli: thrombin at [10 U/mL](cat # SIG-T7009) for 10 minutes or 6 hours, rhTNF-α [10 ng/mL](cat # BLD-570104) for 6 hours, rhIL-4 [20 ng/mL] (cat #BLD-714904) for 48 hours, histamine [10 μM] (cat # SIG-H7125) for 10 minutes, DDAVP [0.04 mcg/mL] (Diamondback Drugs, Arizona, USA) for 24 hours, or fresh human serum diluted 1:4 in PAEC media for 6 hours. Following proinflammatory stimulus, PAECs were analyzed by flow cytometry using previously published protocols to maintain surface expression of selectins.10The cells were labeled sequentially but in the same tube, first to P-selectin selectively (psel. ko.2.5, MCA2418PE, Bio-Rad, CA, USA) followed by an antibody which binds both human E- and P-selectin (1.2B6, INV-A15438, Invitrogen, CA, USA) but has previously been reported to only bind porcine E- selectin and not porcine P-selectin.11 The sequential order of antibody incubation was a secondary precaution against possible 1.2B6 binding to porcine P-selectin and confounding the signals. The labeled cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry (BDVerse cytometer, FlowJo software) for expression of P- and E-selectin. Isotype controls were used for each variable. Gating strategy for flow cytometry can be seen in supplemental figures (Figures S1 and S2).

2.4 |. Neutrophil rolling and adhesion assay

GalTKO.hCD46 PAECs were cultured to confluence on microfluidic channels using the Bioflux 1000z system (Fluxion Bioscience, CA, USA). Based on detection of human TNF-α and IL-4 in Luminex data from ex vivo lung xeno perfusion studies as well as a review of cytokine-mediated expression of selectins in the literature11 confirmed in our own experiments, confluent PAECs were then incubated with human rTNF-α (10 ng/mL) for 4 hours to induce E-selectin or rhIL-4 (20 ng/mL) for 48 hours to induce P-selectin. rPSGL-1.Fc (Targeson, Inc #OT-01–001), a chimeric protein consisting of P-selectin ligand bound to an inactive IgG Fc tag, or glycomimetic compound GMI 1271, a highly selective human E-selectin antagonist provided by GlycoMimetics, Inc (GMI) (Rockville, MD, USA), were added during the last hour of TNF-α or rhIL-4 incubation, as well as added to the perfusate during perfusion. Neutrophils (PMNs) were isolated from fresh human blood using cell separation media and perfused over the PAEC monolayers at 0.7dynes/cm2 in HBSS medium (5 × 105 PMNs/mL media). Neutrophil rolling events and distance of rolling were tracked using the TrackMate v2.8.0 extension to FIJI (imageJ).12

2.5 |. Endothelial integrity, platelet, and leukocyte adhesion

PAECs expressing GalTKO.hCD46 were cultured to confluency on microfluidic channels and stained with viability dye DiOC6 (Invitrogen, cat# INV-L7010) overnight before perfusion. ECs were either left untreated or incubated with GMI 1271 (10 μM) or rPSGL-1.Fc (20 μg/mL) both prior to and during perfusion with whole human blood. Whole human blood was freshly drawn from volunteer human donors, heparinized at 2 IU/mL, and perfused over the endothelial monolayers for 6 hours at 1 dyne/cm2 with intermittent mixing of the inlet well to prevent blood component settling. Following whole blood perfusion, the channels were washed with 1×PBS containing 1:200 dilution of fluorescent antibodies to CD41 (BioLegend, cat# BLD-303725) and CD45 (BioLegend, cat# BLD-36850) for 5 minutes.

Following staining, images were thresholded in the FIJI software using the default algorithm and then the surface area of endothelial cells, the number of leukocytes, and the surface area of platelet coverage were calculated using the “Analyze Particles” function available in FIJI.

2.6 |. Statistical analysis

Two-way analysis of continuous variables was by paired Student’s t-test (Microsoft Excel).

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Proinflammatory mediators released during ex vivo perfusion modulate selectin expression

Analysis of the blood plasma collected during ex vivo lung perfusions demonstrates significant elaboration of multiple inflammatory mediators within 6 hours (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1.

A, Inflammatory mediator elaboration associated with pig lung perfusion with human blood. Cytokine (IFN-γ, TNFα, IL4, IL6, IL8, by Luminex) and inflammatory mediator (histamine, TxB2, by ELISA) elaboration, as percent increase over 6 hours during ex vivo porcine lung perfusions with human blood. Shading reflects second and third quartiles (darker shade is below the median, lighter shade is above the median; bars reflect minimum/maximum). B, Selectin expression by flow cytometry following in vitro stimulation expressed as percent of viable CD31 + cells positive for E- or P-selectin. Each bar represents the mean of three independent experiments ± SEM

Exposure of PAECs to proinflammatory signals or to human serum increased surface selectin expression (Figure 1B). E-selectin was almost absent from untreated cells, and was most strongly upregulated by 4 to 6-hour exposure to rhTNF-α (P = .02) or human thrombin (P = .03). P-selectin expression on PAECs was increased by most stimuli, most notably by 48 hours of exposure to rhIL-4 (P = .017). Histamine and human thrombin demonstrated trends toward selectively increased P-selectin within ten minutes following initial exposure; after 6 hours of thrombin exposure, E- and P-selectin were significantly and similarly upregulated (P < .03). In contrast, 6-hour incubation with rhTNF-α or rhIL-4 was relatively selective for E- and P-selectin, respectively. Incubation with DDAVP for 24 hours showed a trend toward increased P-selectin expression (P = .15). Six-hour incubation with human serum favored an increase in P- over E-selectin expression, although only the increase in E-selectin reached statistical significance (P = .003).

3.2 |. P- and E-selectin mediate rolling of isolated human neutrophils to porcine endothelium

To examine the contribution of P-selectin on neutrophil–PAEC interactions, human PMNs were perfused over rhIL-4-activated PAECs. Although human PMNs in serum-free medium demonstrated extremely infrequent rolling on non-activated porcine endothelium (2 ± 1 events per hpf), PMNs exhibited frequent rolling on endothelium pre-activated with rhIL-4 (mean 88 ± 11 rolling events per hpf; mean 92 ± 4 microns traveled per rolling event, P < .001 vs non-treated) that was inhibited by rPSGL-1. Fc in a dose-dependent manner reaching 95% inhibition at the highest dose tested (Figure 2A). The distance of neutrophil rolling on rhIL-4-activated PAECs was similarly attenuated by rPSGL-1. Fc (Figure 2B).

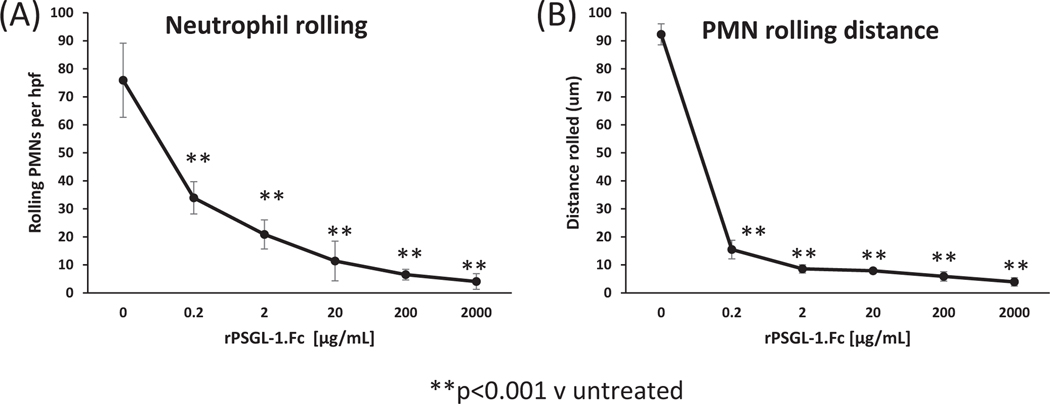

FIGURE 2.

Dose-dependent inhibition of neutrophil rolling by PSGL-1.Fc. A, The number of PMNs rolling on PAECs activated for 48 hours by rhIL-4, per hpf, at 20 time points per channel over 2-minute period, counted by TrackMate software within FIJI. B, PMN rolling distance on rhIL-4-activated PAEC monolayer, calculated by TrackMate. Each curve reflects the mean (±SEM) for three independent experiments performed on different day

In contrast to “resting” endothelium, PMNs perfused over TNF-α-pre-activated PAECs exhibited frequent rolling (mean 63 ± 2 rolling events/hpf; mean 811 ± 22 microns traveled per rolling event, P < .001 vs non-treated) and subsequent tethering (no displacement for multiple frames lasting at least 1- second). GMI 1271 completely eliminated rolling (greater than 95% inhibition) at concentrations of 100–1000 μM with dose-dependent inhibition of rolling at lower concentrations (Figure 3A). Similarly, the distance of neutrophil rolling was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3B).

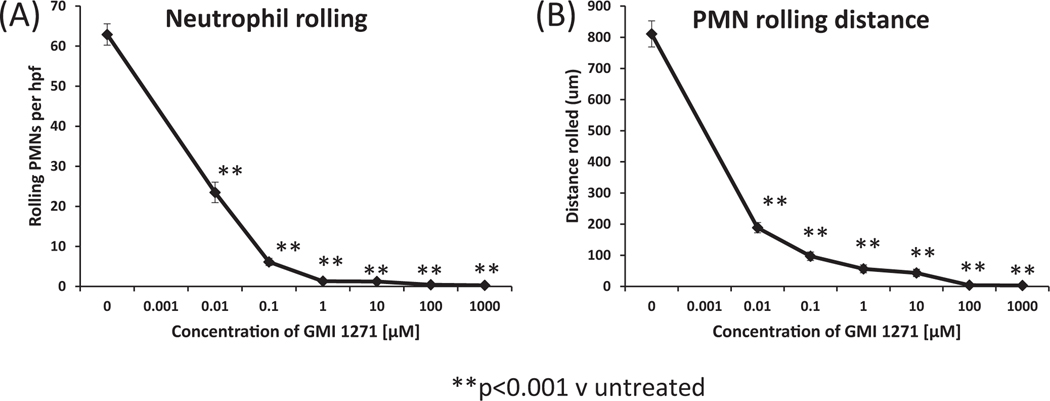

FIGURE 3.

Dose-dependent inhibition of neutrophil rolling by GMI E-selectin inhibitor 1271. A, The number of PMNs rolling on rhTNF-α-activated PAECs per hpf at 20 time points per channel over 2-minute period, counted by TrackMate software within FIJI. B, PMN rolling distance on rhTNF-α-activated PAECs, calculated by TrackMate. Each curve reflects the mean (±SEM) for three independent experiments performed on different days

3.3 |. P- and E-selectin mediate leukocyte adhesion to porcine endothelium during whole blood perfusions

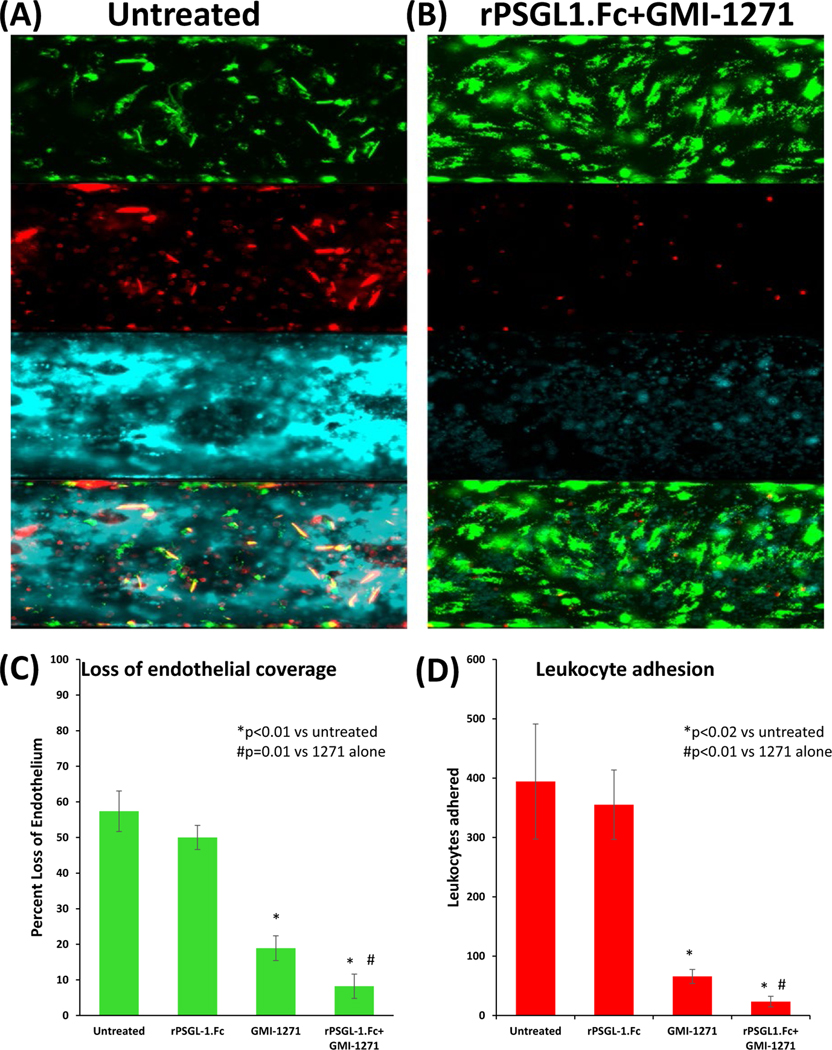

Freshly obtained whole human blood was cytotoxic to GalTKO. hCD46 endothelial cells, with significant neutrophil adhesion, platelet adhesion and aggregation, and severe loss of surface area coverage (Figure 4A). These effects were mitigated by selectin antagonism (Figure 4B). Compared to untreated endothelium (394 ± 97 PMNs/hpf, 57 ± 6% loss EC), GMI 1271 monotherapy [at 10 μM: >~90% effective concentration] but not rPSGL-1.Fc alone [at 20 μg/mL: >~90% effective concentration] was associated with reduced loss of endothelium (GMI 1271: 19 ± 4% loss EC [p < 0.001]; rPSGL- 1.Fc: 50 ± 3% loss EC [P = .07]) (Figure 4C) and leukocyte adhesion (GMI 1271: mean 65 ± 12 PMNs/hpf [P = .02]; rPSGL-1.Fc: 355 ± 58 PMNs/hpf [P = .53]) (Figure 4D). Combined treatment with GMI 1271 and rPSGL-1.Fc had a greater effect to diminish neutrophil adhesion (23 ± 9 PMNs/hpf [P = .016 relative to 1271 alone]) and endothelial loss (8 ± 6% [P < .001 relative to 1271 alone]).

FIGURE 4.

Protection of PAECs from injury by whole human blood by combined E- and P-selectin blockade. PAECs stained with DiOC6 (green) prior to perfusion with fresh whole human blood; post-perfusion staining of leukocytes and platelets was performed using fluorescent antibodies to CD45 (red) and CD41 (cyan), respectively. GMI 1271 (10 μM), rPSGL-1.Fc (20 μg/mL), or both were used to test effects of selectin antagonism in this assay. A, Representative experiment of non-treated PAECS showing severe loss of coverage after six hours (top panel), heavy neutrophil binding (second panel), and extensive platelet adhesion with organizing thrombus (third panel). Merged image (fourth panel) illustrates leukocyte adhesion and platelet aggregation primarily in areas without residual viable (green) endothelial cells. B, Representative experiment of PAECs treated with combined E- and P-selectin antagonists following six-hour perfusion with whole human blood (blood was also treated with GMI1271, rPSGL-1.Fc, or both) exhibit confluent viable (green) endothelial cells (top panel, merged bottom panel), with minimal leukocyte adhesion (red, second panel) and reduced platelet aggregation (cyan, third panel). C, Loss of EC coverage in channel following six-hour perfusion, expressed as percent loss of confluent surface coverage before perfusion, by treatment group. D, Quantification of leukocyte adhesion to PAECs during whole blood perfusion, by treatment group, as calculated by Analyze Particles function in FIJI. Each bar reflects the mean (±SEM) for at least three independent experiments performed on different days. Blockade of E-selectin alone (but not P-selectin alone) significantly reduces leukocyte adhesion and loss of EC coverage relative to no intervention. Addition of P-selectin inhibition is associated with significantly reduced leukocyte adhesion and EC loss relative to E-selectin blockade alone

4 |. DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown that xeno injury is associated with elaboration of proinflammatory cytokines and other mediators, in association with, and presumably contributing significantly to, endothelial activation.11,13–17 Our current observations confirm prior reports that E- and P-selectin expression on porcine cells are variably and differentially increased by exposure to human thrombin, TNF-α, IL-4, DDAVP, histamine and human serum. rhTNF- α and thrombin were the most potent upregulators of E-selectin in our model. Thrombin caused a relatively equal increase in E- and P-selectin, whereas rhTNF-α was more selective for E-selectin, showing that expression of these molecules is differentially regulated, as expected.18 Consistent with the canonical requirement for transcription and translation (E-selectin is not normally stored in PAECs or most other ECs), E-selectin expression increased overtime following cytokine exposure, reaching high levels after 6 hours. Human serum diluted 1:4 in cell culture media also increased E-selectin expression, a phenomenon previously attributed primarily to complement binding and inhibited by C1-inhibitor.19 Incubation with rhIL-4 for 48 hours resulted in the highest observed expression of P-selectin, with minimal change in the level of E-selectin, implicating selective induction of transcription and translation in response to this particular cytokine as previously described.11 In contrast, histamine and thrombin induced P-selectin very shortly (within 10 minutes) after exposure, likely due to release of P-selectin from intracellular stores.11,20

DDAVP treatment was associated with a relatively moderate increase in P-selectin expression at 24 hours. DDAVP has been used by our laboratory and others in the xeno setting21,22 to deplete porcine von Willebrand factor (pvWF), which abnormally aggregates human platelets in the absence of shear, and is associated with improved performance of wild-type pig lungs.23 Our data show that this treatment strategy may lead to the potentially deleterious consequence of increased P-selectin expression, as P-selectin has been previously shown to induce leukocyte rolling in post-capillary venules, and might be expected to mediate or amplify platelet adhesion.24 Until alternative methods to overcome pvWF-mediated coagulation dysfunction are developed, such as “humanization” of the pvWF-binding site for GP1B, our data suggest that P-selectin blockade may be helpful to inhibit this potentially undesirable side effect of DDAVP administration.

Freshly isolated human neutrophils did not roll on non-activated porcine endothelium, consistent with the flow cytometry data on resting PAECs, which showed minimal P-selectin and no E-selectin expression. In contrast, PMNs rolled on ECs activated by either TNF-α or rhIL-4, an effect that, for IL-4-activated endothelial monolayers, was completely eliminated at higher doses of rPSGL-1.Fc.

P-selectin antagonism has been shown by others to reduce monocyte recruitment,25 accelerate thrombolysis,26 inhibit platelet binding to injured vascular endothelium27 and reduce ischemia-reperfusion injury in myocardial,28 renal,29 intestine30 and hepatic31 models. Additionally, it prevented neutrophil migration in a mouse model of acute lung injury.32 Although PSGL-1 binds to P-selectin with the highest affinity, it is also capable of low-affinity binding to E- and L-selectin. In vivo, rPSGL-1.Fc in higher doses was able to reduce leukocyte rolling seen by intravital microscopy in models dependent on of each of the three (E-, P-, L-) individual selectins; interestingly, Hicks et al33 observed that some anti- inflammatory effect was seen with PSGL-1 even in the absence of significant effect on leukocyte rolling, which they speculate may possibly reflect chemokine binding to rPSGL-1.Fc. rPSGL-1.Fc doses of 200 μg/mL or greater almost completely eliminated neutrophil rolling on rhIL-4-activated endothelial cells, presumably reflecting the role of P-selectin in this context, as, by flow cytometry IL-4-treated PAECs expressed high levels of P-selectin with minimal E-selectin expression. Similar to the results with E-selectin antagonism, reduced numbers of rolling PMNs were seen at lower concentration of rPSGL-1.Fc treatment, and PMNs rolled a shorter distance, with interactions typically resulting in release rather than arrest (CTL, personal observations).

GMI 1271 was extremely effective at preventing neutrophil rolling. Although infrequent rolling was present at lower GMI drug concentrations, rolling distance was much shorter, and almost always terminated with release of the neutrophil back into the perfusate (CTL, personal observations), rather than being associated with adhesion and transmigration. Although similar results have previously been shown using blocking antibodies,6 the impact of E-selectin blockade using antibodies was not as potent under flow conditions, and the use of small glycomimetic molecules, particularly those with an extended serum half-life, may be easier to translate into clinical applications of xenotransplantation.

In our whole blood assays, E- (using GMI 1271 at 10 μM) but not P-selectin antagonism (with rPSGL-1.Fc at 20 μg/mL) was associated with significantly reduced leukocyte adhesion. Interestingly, there was a trend toward reduced endothelial loss with rPSGL-1.Fc treatment despite the persistence of heavy leukocyte attachment. E-selectin antagonism alone showed significant attenuation in EC loss. In the presence of E-selectin antagonist GMI 1271, rPSGL1. Fc conferred a significant additional effect, with even less leukocyte binding and reduced loss of endothelium compared to GMI 1271 alone.

One limitation of this study is that the microfluidic channel does not perfectly model complete lung vasculature. The dimensions of the channel are 70 μm in height and 350 μm in width; pulmonary capillaries are much smaller. Elsewhere in the body, the majority of neutrophil sequestration occurs in post-capillary venules, whereas in lungs, the extensive capillary network is the predominant site of leukocyte adhesion and transmigration.34,35 In the small capillaries, selectin- mediated rolling may not be as important as other adhesive interactions. Prior studies in ARDS other non-xeno settings have shown that in the lung, selectin inhibition alone has no effect on neutrophil sequestration, although selectin-blocking antibodies did further attenuate a reduction in sequestration achieved with β2, α4, and α5 integrin blockade.36,37 Endothelial toll-like receptor-4 has also been implicated in LPS-induced PMN sequestration.38 Further studies are required to assess whether selectin antagonism may be useful in xenotransplantation of lungs or other organs, possibly in combination with blockade of integrins or other adhesion receptors.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

We conclude that porcine endothelium activated in response to inflammatory human cytokines exhibit significantly increased P- and E-selectin expression, which mediates subsequent neutrophil rolling. Novel E-selectin antagonist GMI 1271 and rPSGL-1.Fc, a P-selectin antagonist, inhibit selectin-mediated neutrophil rolling. When resting PAECs are exposed to whole human blood under physiologic flow conditions, E-selectin antagonism alone and particularly when combined with P-selectin antagonism significantly decreased both neutrophil adhesion and endothelial damage. These observations predict that selectin antagonism, especially in the time immediately following organ reperfusion, may be useful as part of a strategy to prevent leukocyte- and platelet-mediated injury of xeno lungs and other organs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by U19 AI090959, P01 HL107152, and by unrestricted educational gifts from United Therapeutics/Lung Biotechnology LLC. The GMI E-selectin inhibitory compounds were contributed by GlycoMimetics, Inc. Special thanks to Dudley Strickland, PhD, Center for Vascular and Inflammatory Diseases at the University of Maryland School of Medicine for research support through 2T32HL007698-22A1. Additional thanks to Emily Redding, Research Coordinator at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, for establishing our protocols for human blood donation.

Abbreviations:

- EC

endothelial cells

- GalTKO

α1,3-galactosyl transferase knockout

- hCD46

human membrane cofactor protein, hMCP

- hCRP

human complement regulatory protein

- hDAF

human decay-accelerating factor, hCD55

- hEPCR

human endothelial protein C receptor

- hMCP

human membrane cofactor protein, hCD46

- hTBM

human thrombomodulin

- PAEC

Porcine aortic endothelial cells

- PMN

polymorphonuclear leukocyte

- pTBM

pig thrombomodulin

- rhIL-4

recombinant human interleukin-4

- rhTNF-α

recombinant human tumor necrosis factor alpha

- vWF

von Willebrand Factor

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Higginbotham L, Kim S, Mathews D. Late renal xenograft failure is antibody-mediated: description of the longest-reported survival in pig-to-primate renal xenotransplantation. 2016. American Transplant Congress. Abstract number: A6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohiuddin MM, Singh AK, Corcoran P. Chimeric 2C10R4 anti-CD40 antibody therapy is critical for long- term survival of GTKO.hCD46. hTBM pig-to-primate cardiac xenograft. Nature. Communications 2016;7. Article number: 11138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah J, Navarro-Alvarez N, DeFazio M. A bridge to somewhere: 25-day survival after pig-to-baboon liver xenotransplantation. Ann Surg. 2016;263:1069–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zarbock A, Ley K. Neutrophil adhesion and activation under flow. Microcirculation. 2009;16:31–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zarbock A, Ley K, Mcever RP, Hidalgo A. Leukocyte ligands for endothelial selectins: specialized glycoconjugates that mediate rolling and signaling under flow. Blood. 2011;118:6743–6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson LA, Tu L, Steeber DA. The role of adhesion molecules in human leukocyte attachment to porcine vascular endothelium: implications for xenotransplantation. J Immunol. 1998;161:6931–6938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezzelarab MB, Liu YW, Lin CC, et al. Role of P-selectin and P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 interaction in the induction of tissue factor expression on human platelets after incubation with porcine aortic endothelial cells. Xenotransplantation. 2013;21:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang J, Patton JT, Sarkar A, Ernst B, Magnani JL, Frenette PS. GMI-1070, a novel pan-selectin antagonist, reverses acute vascular occlusions in sickle cell mice. Blood. 2010;116:1779–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkler IG, Barbier V, Nutt HL, et al. Administration of E-selectin antagonist GMI-1271 improves survival after high- dose chemotherapy by alleviating mucositis and accelerating neutrophil recovery. Blood. 2013;122:2266. Accessed June 11, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gräbner R, Till U, Heller R. Flow cytometric determination of E-selectin, vascular cell adhesion molecule- 1, and intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 in formaldehyde- fixed endothelial cell monolayers. Cytometry. 2000;40:238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stocker CJ, Sugars KL, Harari OA, Landis RC, Morley BJ, Haskard DO. TNF-, IL- 4, and IFN- regulate differential expression of P- and E-selectin expression by porcine aortic endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:3309–3315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tinevez JY, Perry N, Schindelin J, et al. TrackMate: an open and extensible platform for single-particle tracking. Methods. 2016;115:80–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bach FH, Ferran C, Soares M, et al. Modification of vascular responses in xenotransplantation: inflammation and apoptosis. Nat Med. 1997;3:944–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Y-G, Sykes M. Xenotransplantation: current status and a perspective on the future. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;07:519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jurd KM, Gibbs RV, Hunt BJ. Activation of human prothrombin by porcine aortic endothelial cells—a potential barrier to pig to human xenotransplantation. Blood Coag Fibrinol. 1996;7:336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Mohanna F. Human neutrophil gene expression profiling following xenogeneic encounter with porcine aortic endothelial cells: the occult role of neutrophils in xenograft rejection revealed. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laird C, Burdorf L, Pierson RN. Lung xenotransplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transpl. 2016;21:272–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bach FH, Robson SC, Ferran C, et al. Endothelial cell activation and thromboregulation during xenograft rejection. Immunol Rev. 1994;141:5–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sølvik UØ, Haraldsen G, Fiane AE, et al. Human serum- induced expression of E- selectin on porcine aortic endothelial cells in vitro is totally complement mediated. Transplantation. 2001;72:1967–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gebrane-Younès J, Drouet L, Caen JP, Orcel L. Heterogeneous distribution of Weibel-Palade bodies and von Willebrand factor along the porcine vascular tree. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:1471–1484. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaca JG, Lesher A, Aksoy O, Ruggeri ZM, Parker W, Davis RD. The role of the porcine von willebrand factor: baboon platelet interactions in pulmonary xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2002;74: 1596–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lau CL, Cantu E, Gonzalez-Stawinski GV, et al. The role of antibodies and von willebrand factor in discordant pulmonary xenotransplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1065–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim YT, Lee HJ, Lee SW, et al. Pre-treatment of porcine pulmonary xenograft with desmopressin: a novel strategy to attenuate platelet activation and systemic intravascular coagulation in an ex-vivo model of swine-to-human pulmonary xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanwar S, Woodman RC, Poon MC. Desmopressin induces endothelial P-selectin expression and leukocyte rolling in postcapillary venules. Blood. 1995;86:2760–2766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valenzuela NM, Hong L, Shen X-D, et al. Blockade of P-selectin is sufficient to reduce MHC I antibody-e licited monocyte recruitmentin vitroand in vivo. Am J Transplant. 2012;13:299–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A, Villani MP, Patel UK, Keith JC, Schaub RG. Recombinant soluble form of PSGL-1 accelerates thrombolysis and prevents reocclusion in a porcine model. Circulation. 1999;99:1363–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Théorêt JF, Bienvenu JG, Kumar A. P-selectin antagonism with recombinant p-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (rPSGL-Ig) inhibits circulating activated platelet binding to neutrophils induced by damaged arterial surfaces. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:658–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayward R. Recombinant soluble P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 protects against myocardial ischemic reperfusion injury in cats. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41:65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singbartl K, Ley K. Protection from ischemia-reperfusion induced severe acute renal failure by blocking E-selectin. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2507–2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farmer DG, Anselmo D, Shen XD, et al. Disruption of P-selectin signaling modulates cell trafficking and results in improved outcomes after mouse warm intestinal ischemia and reperfusion injury. Transplantation. 2005;80:828–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsuchihashi S-I, Fondevila C, Shaw GD, et al. Molecular characterization of rat leukocyte P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 and effect of its blockade: protection from ischemia-reperfusion injury in liver transplantation. J Immunol. 2005;176:616–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shao HZ, Qin BY. rPSGL-1-Ig, a recombinant PSGL-1-Ig fusion protein, ameliorates LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice by inhibiting neutrophil migration. Cell Mol Biol. 2015;61:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hicks AER, Nolan SL, Ridger VC, Hellewell PG, Norman KE. Recombinant P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 directly inhibits leukocyte rolling by all 3 selectins in vivo: complete inhibition of rolling is not required for anti-inflammatory effect. Blood. 2003;101:3249–3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reutershan J, Ley K. Bench-to-bedside review: acute respiratory distress syndrome – how neutrophils migrate into the lung. Crit Care. 2004;8:453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burns AR, Smith CW, Walker DC. Unique structural features that influence neutrophil emigration into the lung. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:309–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carraway MES, Welty-Wolf KE, Kantrow SP, et al. Antibody to E- and L-selectin does not prevent lung injury or mortality in septic baboons. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:938–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burns JA, Issekutz TB, Yagita H, Issekutz AC. The β2, α4, α5 integrins and selectins mediate chemotactic factor and endotoxin-enhanced neutrophil sequestration in the lung. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1809–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andonegui G. Endothelium- derived Toll-like receptor-4 is the key molecule in LPS-induced neutrophil sequestration into lungs. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.