Abstract

The adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV-2) Rep78 and Rep68 proteins are required for replication of the virus as well as its site-specific integration into a unique site, called AAVS1, of human chromosome 19. Rep78 and Rep68 initiate replication by binding to a Rep binding site (RBS) contained in the AAV-2 inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) and then specifically nicking at a nearby site called the terminal resolution site (trs). Similarly, Rep78 and Rep68 are postulated to trigger the integration process by binding and nicking RBS and trs homologues present in AAVS1. However, Rep78 and Rep68 cleave in vitro AAVS1 duplex-linear substrates much less efficiently than hairpinned ITRs. In this study, we show that the AAV-2 Rep68 endonuclease activity is affected by the topology of the substrates in that it efficiently cleaves in vitro in a site- and strand-specific manner the AAVS1 trs only if this sequence is in a supercoiled (SC) conformation. DNA sequence mutagenesis in the context of SC templates allowed us to elucidate for the first time the AAVS1 trs sequence and position requirements for Rep68-mediated cleavage. Interestingly, Rep68 did not cleave SC templates containing RBS from other sites of the human genome. These findings have intriguing implications for AAV-2 site-specific integration in vivo.

Human adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV-2) is a nonpathogenic parvovirus which establishes latency in cultured human cell lines (4, 46). It integrates into the genome of infected cells, with a high preference for a specific site, AAVS1, on human chromosome 19 (22, 23, 46, 47). AAV-2 replication is stimulated either by coinfection with an adenovirus or herpesvirus as a helper or by genotoxic stimuli such as X-ray and UV treatment (3, 4). Infection of a latently infected cell line with a helper virus leads to rescue and replication of the integrated AAV genome, with the generation of infective progeny (3, 4).

AAV-2 has a single-stranded genome approximately 4.7 kb in length, which contains two open reading frames, rep and cap (55). The whole genome is flanked by 145-bp terminal repeats (ITRs) which fold back into a hairpin-like structure and are required for AAV-2 DNA replication, packaging, and site-specific integration (3, 46). Crucial for the AAV-2 life cycle is the activity of the viral Rep78 and Rep68 proteins: these are translated from unspliced and spliced transcripts initiated from the p5 promoter and differ only at the C terminus (55). The two proteins, which probably function as multimers, have several biochemical properties in common and are essential for AAV-2 replication and site-specific integration (4, 14, 51, 55).

AAV-2 replication occurs via a unidirectional, leading-strand DNA synthesis which closely resembles rolling-circle replication (RCR) (3). During AAV-2 replication, Rep78 and Rep68 bind the ITRs at a specific DNA sequence, the Rep binding site (RBS), whose core region consists of four tandem repeats of the GAGC tetramer (6, 18, 19, 45). Upon binding the ITRs, Rep78 and Rep68 cleave in a site- and strand-specific manner between the two thymidine residues of the AGTTGG sequence, at the terminal resolution site (trs), which is located near the RBS in the ITRs (5, 18, 49, 53). This nicking provides the 3′-OH terminus, which serves as a primer for replication and is followed by unwinding of the terminal hairpins, probably mediated by the helicase activity of Rep68 or Rep78; the ITRs are thus converted to a blunt-ended and double-stranded form in a process, called terminal resolution, which allows the replication of the AAV-2 termini (5, 54). Rep78 and Rep68 have also the capacity to hydrolyze ATP, and the helicase activity is ATP dependent (18, 67, 69).

Several lines of evidence have identified Rep78 and Rep68 and the ITRs as the only viral elements required for integration into human chromosome 19 (27, 29, 68). Recombinant AAV vectors lacking the rep gene do not integrate site specifically (10, 21). In contrast, transgenes flanked by the AAV ITRs integrate preferentially into AAVS1 when introduced into cell lines together with Rep68 or Rep78 expression vectors or recombinant proteins (2, 25, 39, 42, 43, 49, 56). An RBS flanked by a trs-like GGTTGG sequence is also present in AAVS1, and genetic analysis has demonstrated that these two cis-acting elements on chromosome 19 are necessary and sufficient to dictate AAV-2 site-specific integration (12, 28, 29). Rep78 and Rep68 mediate the formation in vitro of a complex between an AAV-2 ITR and an AAVS1 oligonucleotide by simultaneously binding the RBS contained in the two DNA substrates (7, 63). This has led to the proposal that AAV integration initiates when multimeric Rep78-Rep68 complexes direct an AAV circular genome toward AAVS1 by juxtapositioning the two DNA substrates via Rep binding (10, 63). Subsequently, Rep78 and Rep68 nick the trs at AAVS1, thus leaving a free 3′-OH terminus, which serves as a primer for replication mediated by the cellular replication machinery. Two Rep-mediated strand switchings produce a nonhomologous recombination ITR/AAVS1 junction which allows the replication complex to proceed through the AAV-2 genome, which is thus inserted 3′ to the RBS in AAVS1. A third strand-switching event translocates the replication complex to the chromosomal DNA and terminates integration (10, 27, 28).

This model accounts for a number of features of AAV-2 integration, but there are still some issues which need to be clarified. In particular, there is no evidence so far that Rep78 and Rep68 can indeed efficiently nick the AAVS1 at the trs. In fact, the two proteins cleave in vitro a duplex linear AAVS1 template with very low efficiency (59, 60). Furthermore, the trs sequence and distance from the RBS are different in AAVS1 and the ITRs, and it is not yet clear whether this affects the endonuclease activity of Rep78 and Rep68 at AAVS1 (59). To fill these gaps in our information, the development of a sensitive in vitro assay for studying Rep activity at AAVS1 is highly desirable.

Rep78 and Rep68 share several functional properties with RCR initiator proteins involved in the replication of small prokaryotic genomes: they bind DNA at a specific site of the replication origin, nick a nearby sequence in a site- and strand-specific manner, and remain covalently bound through a phosphotyrosyl linkage with the 5′-end phosphate at the nick (38). In common with RCR initiators, Rep78 and Rep68 also have the two-His structural motif (HuHuuu, where u is any hydrophobic residue) which is believed to be important in metal ion coordination required for the activities of replication proteins (17). Starting from the observation that RCR initiators nick their DNA substrates only if they are supercoiled (38), we tested whether also Rep-mediated cleavage at AAVS1 trs might be affected by the DNA topology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of Rep68.

Recombinant Rep68 was produced and purified as previously described (7, 25), with minor modifications. Briefly, the Rep68 coding region was amplified by PCR using plasmid pCMV/Rep68 as a template (25, 43). The fragment obtained was cloned in frame with the C terminus of maltose binding protein (MBP) into the unique BamHI site of pMAL-cRI vector (New England Biolabs). The MBP-Rep68 fusion was produced as a soluble protein and partially purified by amylose affinity chromatography as described previously (7, 25). The fusion protein was then dialyzed against TN buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl). To remove the maltose-binding moiety, CaCl2 (2 mM, final concentration) was added to TN buffer, and the MBP-Rep68 fusion was incubated with Factor Xa protease at an MBP-Rep68 Factor Xa weight ratio of 100 to 0.5 for 3 h at 4°C. The reaction was stopped by adding EGTA (final concentration, 10 mM [pH 8.0]), and the sample was loaded on a prepacked Mono Q HR 5/5 (anion exchange; Amersham, Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated in TN buffer. The column was developed with 10 ml of linear gradient (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM EGTA to 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM EGTA) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The peak corresponding to Rep68 was collected and further purified by gel filtration onto a prepacked Superdex 75 HR 10/30 column (Amersham, Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) and 150 mM NaCl. As previously reported, the purity of the protein was >99%, as judged by silver staining of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels (25).

Preparation of SC plasmids.

All supercoiled (SC) plasmids were prepared by the Triton lysis method and purified by double CsCl gradient centrifugation as described elsewhere (1).

Plasmid construction.

To obtain plasmid pBS/trs, two complementary oligonucleotides were designed and annealed, to generate a double-stranded fragment spanning nucleotides (nt) 379 to 434 of the AAVS1 region and flanked at its 5′ and 3′ ends by BamHI and XbaI sites, respectively. This region was inserted into the BamHI and XbaI sites of plasmid pBluescript II KS(+) (Stratagene), thus obtaining plasmid pBS/trs. Plasmids containing trs either mutated in sequence or located at various distances from the RBS were obtained according to the same strategy but using oligonucleotides containing the desired mutations. Plasmids pBSmut1 and pBSmut2, also obtained by using this strategy, contain the AAVS1 region spanning nt 379 to 434 in which the wild-type RBS was mutated to GCTCGCGATAGATCTG (pBSmut1) and TAGAGCGATAGATCTG (pBSmut2) (35), as indicated by underlining. Plasmids pIGFBP-2, pInh, pILF, pBRCA-1, and pERCC-1 contain RBSs identified in different regions of the human genome (65); insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 (IGFBP-2) gene, inhibin gene, interleukin-2 enhancer binding factor (ILF) gene, BRCA1, and ERCC1, respectively. As done for the AAVS1 region, these sequences were obtained by annealing of complementary oligonucleotides and cloned into pBluescript II KS(+) vector.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs).

The various radiolabeled substrates (15,000 cpm) were incubated with increasing concentrations of Rep68 in reaction mixtures (20 μl) that contained 10 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.9), 8 mM MgCl2, 1 μg of poly(dI-dC), 40 mM KCl, and 0.2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Following a 30-min incubation at room temperature, 4 μl of 20% Ficoll was added; samples were then loaded on a 4% polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio, 29:1; 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA) and electrophoresed in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA at room temperature and 10 V/cm. Gels were then dried and subjected to autoradiography at −80°C.

Nicking assay on SC templates.

The standard SC nicking assays were performed in 30 μl of a solution containing 30 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 7 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP, 40 mM creatine phosphate, and 1 μg of creatine phosphokinase. The reaction mixtures also contained SC plasmid DNA and purified Rep68 at the concentrations indicated in the figure legends. The reactions were carried out at 37°C for 1 h and then terminated by adding 40 μl of stop solution (proteinase K [1.2 μg/μl], 0.5% SDS, 30 mM EDTA [pH 7.5]). After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the DNA samples were subjected to phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Precipitated DNA samples were resuspended in water and resolved on a 1% agarose gel (1% agarose, 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA [TAE]) which was subsequently stained by incubation at room temperature for 30 min in 1× TAE containing ethidium bromide (0.3 μg/ml).

Preparation of RC topoisomers and separation of SC, NC, and RC molecules.

Three hundred-nanogram aliquots of SC plasmids were relaxed by treatment with 6 U of calf thymus topoisomerase I (GibcoBRL) for 2 h at 37°C in 25 μl of a reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA and 30 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml. Subsequently, reaction mixtures were first adjusted to 35 μl containing 4 mM ATP, 40 mM creatine phosphate, and 1.2 μg of creatine phosphokinase and then incubated for an additional hour at 37°C in the presence or absence of 300 ng of recombinant Rep68. The reactions were terminated by treatment with proteinase K, extracted with phenol, precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended in 2× TAE. The negative SC, relaxed circular (RC), and nicked circular (NC) forms of the template plasmid were resolved on agarose gels as described elsewhere (15). Briefly, samples were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel in 2× TAE buffer in the absence of ethidium bromide for 5 h at 3 V/cm. Gel was then stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml), and electrophoresis was continued for an additional hour under the same conditions but in a running buffer containing ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml). Under these conditions, the first electrophoresis step separates the SC molecules from the RC and NC forms; in the second step, the RC topoisomeres migrate faster than the NC form (15).

Mapping of the nicking site on SC templates.

A standard SC nicking reaction was performed by incubating 1 μg of SC plasmid substrates (plasmids pRVK, pBS/trs and its derivatives containing trs mutants, and psub201) with 300 ng of Rep68 protein. After proteinase K treatment, phenol-chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation, the reaction products (NC forms of the plasmids) were dissolved in water and used as templates for sequencing reactions, which were performed by the dideoxy method using the Sequenase version 2.0 polymerase (U.S. Biochemical Corporation). A 32P-labeled oligonucleotide annealing with the trs-containing (trs+) strand was used as the primer for the sequencing reactions. The primer was centered on the T7 promoter region in the case of plasmid pBS/trs and its derivatives. In the case of plasmid pRVK, the primer spanned positions 495 to 479 of AAVS1. In the case of plasmid psub201, the primer spanned positions 4686 to 4672 of the AAV-2 genome contained in this plasmid (48). Reaction products were analyzed on 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gels.

Covalent attachment of Rep68 to the 5′ end of the cleavage site.

Covalent attachment of Rep68 to the 5′ end was assessed as described elsewhere (40), with some modifications. Three hundred nanograms of Rep68 was incubated with 1 μg of SC plasmid pRVK in a standard SC nicking reaction for 1 h at 37°C. The reaction product was digested with restriction enzyme SmaI; the 3′ ends of the digested fragments were labeled with [α32-P]ddATP by using terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase (TdT). After 1 h at 37°C, the labeled products were immunoprecipitated in 0.05% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline with a polyclonal rabbit antiserum against Rep68 (25). After a 6-h incubation at 4°C, samples were washed extensively with 0.05% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline. The immunoprecipitates were then divided into two aliquots, one of which was digested with proteinase K. Both aliquots were then subjected to phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Finally, samples were resuspended in 0.1% SDS–30% formamide–6.5 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) and resolved on an 8% sequencing gel.

Determination of strand- and site-specific nicking on AAVS1 SC templates.

One microgram of SC plasmid pRVK was incubated in the standard SC nicking reaction with or without 300 ng of Rep68 for 1 h at 37°C. After proteinase K treatment, phenol-chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation, each reaction product (NC plasmid) was divided into two aliquots, and the trs+ and trs− strands were selectively labeled. To label the strand not containing the trs, NC pRVK was digested with PvuII; this digestion released three fragments, one of which contains nt 1 to 513 of AAVS1 flanked at its 5′ end by an additional 175 bases derived from the vector (plasmid pBluescript) backbone. All of the fragments were dephosphorylated by treatment with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase and 5′-end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. After phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, the reaction mixture was digested with restriction enzyme EcoRI, whose unique recognition site constitutes the 5′ end of the AAVS1 site as cloned into plasmid pRVK (nt 1 to 6) (23). This digestion thus selectively removed the radioactively labeled 5′ end of the trs+ strand; the resulting EcoRI-PvuII fragment was thus selectively labeled only at the 5′ end of the trs− strand. This end-labeled fragment was purified from an agarose gel and loaded on a 6% sequencing gel. To selectively label the trs+ strand, NC (Rep68-treated) pRVK was digested with PvuII as described above. The released fragments were then labeled at their 3′ ends by treatment with the TdT and [α32-P]ddATP. The labeled fragments were then digested with EcoRI; in this case, the digestion selectively removed the radioactively labeled 3′ end of the trs− strand. Therefore, the resulting EcoRI-PvuII fragment was selectively labeled only at the 3′ end of trs+ strand. Again, the labeled fragment was purified and loaded on a 6% sequencing gel.

DNase I footprinting analysis.

The DNase footprinting analysis on SC or linear AAVS1 templates was performed as described elsewhere (58), with some modifications. Plasmid pRVK was used as the SC template, while an MscI-PvuII duplex-linear fragment derived from plasmid pRVK and spanning nt 210 to 513 of AAVS1 was used as the linear template. One hundred-nanogram aliquots of SC or duplex-linear templates were incubated with 1 μg of Rep68 for 30 min at room temperature in 30 μl of a solution containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 8 mM MgCl2, 40 mM KCl, 0.2 mM DTT, and 1.5 μg of poly(dI-dC). CaCl2 was then added to a final concentration of 2.5 mM, and the samples were digested with 5 ng of DNase I (Boehringer Mannheim catalog no. 104 159; conversion factor, 1 ng = 2 mU) for 2 min at room temperature. Digestion was stopped by adding 1 volume of DNase I stop buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1% SDS, 30 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). After phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, specific cleavages were detected by PCR-mediated primer extension on the DNase I-treated DNA using a 32P-labeled primer. Analysis of the trs+ strand was performed using as a primer an oligonucleotide (5′-CCCCACTGCCGCAGCTGC-3′) annealing to this strand at the level of the AAVS1 sequence from nt 527 to 510. For analysis of the trs− strand, we used a primer (5′-CCGGGAGATCCTTGGGGCGGTGGGG-3′) annealing to this strand at the level of the AAVS1 region spanning nt 310 to 334. Since the selected AAVS1 region is enriched in G+C sequences (23), primer extension was performed by using the thermostable DNA polymerases and the additional reagents contained in the Advantage-GC2 PCR kit (Clontech) that we have successfully used to efficiently amplify GC-rich sequences (S. Lamartina and C. Toniatti, unpublished results). Specifically, samples were resuspended in a buffer containing 1% glycerol, 0.8 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1.0 mM KCl, 0.5 mM (NH4)2SO4, 2 μM EDTA, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.005% Thesit, 40 mM Tricine-KOH, 15 mM potassium acetate, 3.5 mM magnesium acetate, 5% dimethyl sulfoxide, 3.75 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 1 M GC-Melt reagent, 0.2 mM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP, and the mixture of KlenTaq-1 DNA polymerase, Deep VentR, and TaqStart antibodies as supplied by the manufacturer (Clontech). Reaction mixtures also contained 1.5 × 106 cpm (2 pmol) of the primers labeled at the 5′ end with [γ-32P]ATP by T4 polynucleotide kinase. After a preheating step at 94°C for 1 min, the reaction was allowed to proceed for 30 cycles of amplification and extension (1 min at 94°C, 30 s at 94°C, and 3 min at 72°C) and then stopped with 50 μl of DNase I stop buffer. Reaction products were extracted with phenol-chloroform and ethanol precipitated. Samples were then resuspended in 4 μl of denaturing loading buffer (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA, 0.05% bromophenol blue, 0.05% xylene cyanol), denatured for 5 min at 100°C, and electrophoresed on a 6% sequencing gel.

RESULTS

Rep68 poorly cleaves a linearized AAVS1 template.

In vitro-translated AAV-2 Rep78 poorly nicks the potential target site present in a 57-bp-long linear duplex DNA fragment spanning the AAVS1 RBS-trs region (23). Experiments performed using AAV ITRs as DNA substrates have demonstrated that Rep78 and Rep68 nick the trs in a linear template containing only the stem of the ITR with 50- to 100-fold lower efficiency than the hairpinned ITR, which also includes the ITR loop (7, 35, 53, 54). This has been attributed to additional contacts that Rep78 and Rep68 make with sequences contained in the ITR loop but outside the consensus RBS (45, 67). We thus checked whether Rep endonuclease might be more active on longer templates.

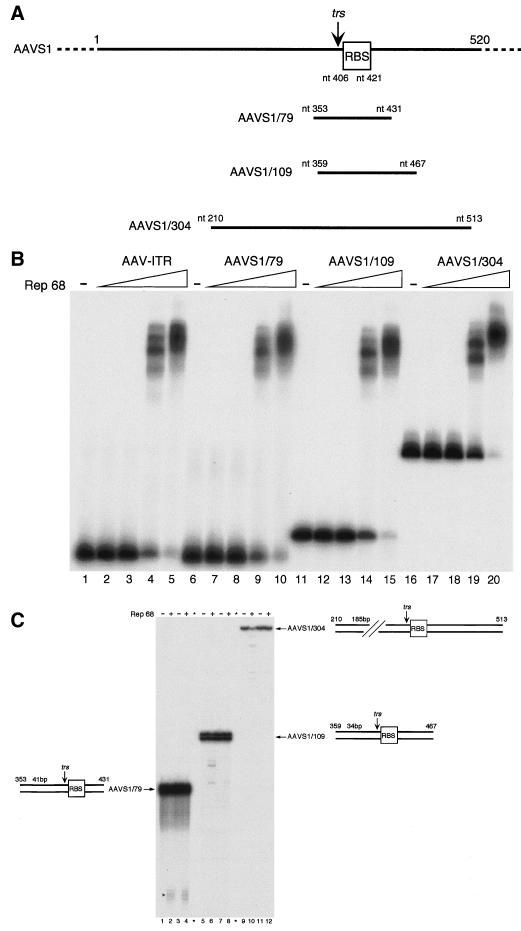

AAV-2 Rep68 was produced in Escherichia coli, purified to near homogeneity as described previously (25), and tested for its ability to bind and nick three AAVS1 fragments of different lengths (79, 109, and 304 bp). Figure 1A shows the three fragments and the location of the RBS-trs region within them. Rep68 binding was monitored by incubating equivalent amounts of double-stranded probes with increasing concentrations of the protein. By EMSA, Rep68 bound all three linear fragments with similar affinities (Fig. 1B). However, even at the highest Rep68/DNA molar ratio (higher than 2,000:1) at which more than 95% of DNA is bound (Fig. 1B, lanes 5, 10, and 15), only minimal cleavage was observed with the three linear AAVS1 substrates (Fig. 1C). These findings, which confirm and extend previous results (60), demonstrate that Rep68 cleavage in vitro of an AAVS1 linear fragment is a largely inefficient process, regardless of the length of the DNA substrate.

FIG. 1.

AAV-2 Rep68 poorly cleaves duplex-linear AAVS1 DNA substrates. (A) Schematic representation of the three AAVS1 linear substrates (AAVS1/79, AAVS1/109, and AAVS1/304) used in binding and nicking experiments. Positions of the RBS and the trs are indicated. (B) EMSAs. AAVS1 duplex-linear templates (15,000 cpm; corresponding to 3.7, 5.7, and 8.3 fmol) were incubated with increasing amounts (5, 10, 100, and 1,000 ng; corresponding to 0.09, 0.18, 1.8, and 18 pmol) of recombinant Rep68 in a standard binding reaction buffer (see Materials and Methods). Reaction products were resolved on a nondenaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel. In the absence of protein, no shifted complexes were detected (lanes 1, 6, 11, and 16). (C) Rep68 nicking on linear AAVS1 substrates. Rep68 (1 μg; 18 pmol) was incubated with 4 fmol of radiolabeled AAVS1/79, AAVS1/109, and AAVS1/304 linear substrates (20,000, 12,000, and 5,000 cpm, respectively), in the presence (lanes 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, and 12) or absence (lanes 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, and 10) of 1 μg of unspecific competitor poly(dI-dC). Standard endonuclease reactions were performed for 60 min at 37°C, followed by proteinase K digestion and phenol-chloroform extraction. Reaction products were resolved on an 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The triangle indicates the released products of the expected size observed with template AAVS1/79. Fragments released from AAVS1/109 and AAVS1/304 substrates were observed only after longer exposures (not shown).

Rep68 efficiently nicks an SC AAVS1 substrate.

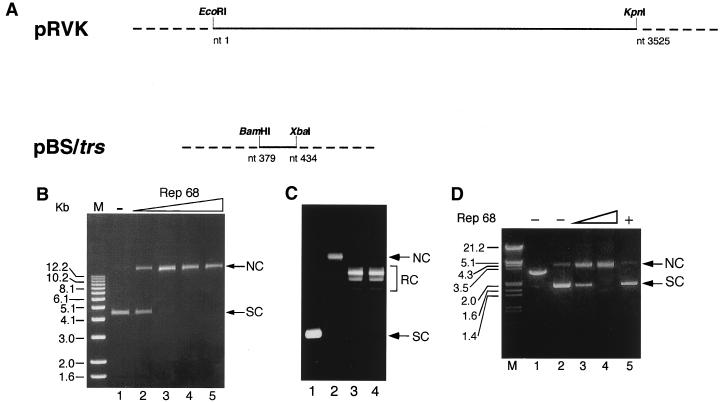

Rep68 shares protein motifs and functional properties with initiator proteins involved in RCR (17). These proteins are known to start replication upon cleavage of a specific site but only if the substrate is supercoiled (38). We therefore asked whether also Rep68 might preferentially cleave an SC AAVS1 target sequence. To test this possibility, 100 ng of SC plasmid pRVK (a gift from K. I. Berns, Cornell University Medical College, Ithaca, N.Y.), which is a pBluescript vector containing the AAVS1 sequence from nt 1 to 3525 (schematically represented in Fig. 2A), was incubated in a classical endonuclease reaction with increasing concentrations of Rep68. After 1 h at 37°C, the plasmid was digested with proteinase K, purified by phenol-chloroform extractions, precipitated with ethanol, and then loaded onto an agarose gel. It was expected that if Rep68 had cleaved the trs in AAVS1 in a strand- and site-specific manner, the plasmid conformation would have changed from SC to NC. As shown in Fig. 2B, this is in fact what was observed: in the presence of Rep68, the monomeric SC pRVK (Fig. 2B, lane 1) was converted to NC. The modification was already evident at a Rep68/pRVK molar ratio of 8:1 (10 ng of Rep68:100 ng of pRVK [Fig. 2B, lane 2) and was complete with as low as a 23-fold molar excess (30 ng) of Rep68 (Fig. 2B, lane 3). Notably, RC pRVK was not cleaved (Fig. 2C, lanes 3 and 4), a further indication that supercoiling of the template is required for efficient nicking.

FIG. 2.

Rep68 efficiently nicks an SC plasmid containing the AAVS1 RBS-trs region. (A) Schematic representation of the AAVS1 region contained in plasmids pRVK and pBS/trs. The BamHI and XbaI sites of pBS/trs originate from the cloning procedure and do not refer to the original AAVS1 sequence (23). (B) Rep68-mediated cleavage of pRVK. One hundred nanograms of plasmid pRVK (6,485 bp long) was incubated in a standard endonuclease reaction with 10 (lane 2), 30 (lane 3), 50 (lane 4), and 100 (lane 5) ng of recombinant Rep68. After 60 min at 37°C, reaction products were digested with proteinase K, purified by phenol-chloroform extraction, and concentrated by precipitation with ethanol. Samples were then resolved on a 1% agarose gel, which was stained by 30 min of incubation in TAE buffer containing ethidium bromide (0.3 μg/ml). Lane 1, untreated pRVK. The SC and NC forms of the plasmid are indicated by arrows. M, size markers. (C) Rep68 does not cleave RC templates. Three hundred nanograms of SC pRVK was converted to RC form by topoisomerase I treatment and then incubated with or without 300 ng of Rep68 in a standard endonuclease reaction (see Materials and Methods). In control experiments, 300 ng of SC pRVK was incubated with or without 300 ng of Rep68. Reaction products were resolved by electrophoresis on agarose gels as described elsewhere (15). Lanes 1 and 2, SC pRVK incubated without and with Rep68, respectively; lanes 3 and 4, RC pRVK topoisomers incubated without and with Rep68, respectively. (D) Rep68-mediated cleavage of pBS/trs. One hundred nanograms of plasmid pBS/trs (3,011 bp long) was incubated with 5 (lane 3) and 20 (lane 4) ng of recombinant Rep68. Endonuclease reactions were performed as described for panel B. Lane 1, linearized pBS/trs; lane 2, untreated pBS/trs; lane 5; control plasmid pBS treated with 100 ng of Rep68. Sizes are indicated in kilobases.

To rule out the possibility that formation of NC forms of pRVK was due to Rep68 nicking at sites other than the expected target region, a 56-bp fragment containing the RBS and trs of AAVS1 was cloned into the pBluescript vector (plasmid pBS/trs [Fig. 2A]). As shown in Fig. 2D, this substrate was converted from the SC to the NC form by Rep68 as efficiently as pRVK (Fig. 2D, lanes 3 and 4). No cleavage was observed with the empty vector (Fig. 2D, lane 5), thus demonstrating that Rep68 nicking was restricted to the RBS-trs region. RC pBS/trs was also not cleaved by Rep68 (not shown).

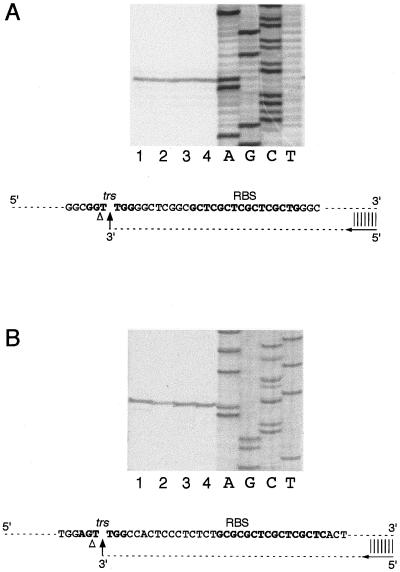

Rep68 nicks an SC AAVS1 trs between the two T residues (GGT/TGG).

To verify that conversion from the SC to the NC form was due to site-specific nicking at the GGTTGG trs sequence, the Rep68-generated NC form of pRVK was purified and used as a template for sequencing by the dideoxy-chain termination method (1). An oligonucleotide annealing with the trs+ strand and 3′ to the RBS was used as a primer. A nick in the trs+ strand at the target GGTTGG sequence would halt synthesis of the complementary DNA strand and lead to accumulation of DNA strands terminated at the nick. As shown in Fig. 3A, in the case of the NC form, polymerization of the new strand was indeed blocked at the level of the trs (lanes 1 to 4). By comparison with the DNA sequence ladder obtained in a similar sequencing reaction but using an SC, not Rep68-treated pRVK as a template (Fig. 3A, lanes A, G, C, and T), the cutting site apparently mapped between the guanosine and the first thymidine residue (GG/TTGG). However, the Sequenase DNA polymerase used in the sequencing reaction displays a TdT activity which adds an extra nucleotide once it reaches the end of the template DNA (33). Notably, we confirmed this TdT activity by using the same technique to map the nicks introduced by restriction enzymes PstI, BamHI, SmaI, and EcoRI in the context of pBluescript: in all cases, Sequenase was found to promote a nontemplated addition of one nucleotide once it reached the end of the template DNA (not shown). Based on this evidence, therefore, the cutting site in AAVS1 trs should probably be moved one nucleotide to the 3′ side, with the nick occurring between the two T nucleotides (GGT/TGG [Fig. 3A]). To confirm this supposition, we used the same technique to map the Rep68 nicking site in the AAV-2 ITR trs. SC plasmid psub201, which contains the AAV-2 genome, was nicked with Rep68, and the site of strand interruption in the context of the AAV-2 ITR trs was mapped (Fig. 3B). Also in this case, the apparent cutting site (AG/TTGG [Fig. 3B]) was shifted by one nucleotide with respect to the previously mapped AGT/TGG cleavage at the AAV-2 ITR trs (18, 53).

FIG. 3.

Mapping of the Rep68 nicking site. (A) Mapping of the cleavage site on SC AAVS1 templates. SC plasmid pRVK (1 μg) was converted to NC by treatment with 300 ng of Rep68 protein. The purified NC form was used as a template for a standard sequencing reaction performed by using Sequenase and a primer, schematically represented by an arrow, which spanned nt 495 to 479 of AAVS1 and annealed with the trs+ strand. Reaction products were loaded on a 8% denaturing gel. Lanes 1, 2, 3, and 4 correspond to A, G, C, and T sequencing reactions, respectively, performed using the NC (Rep68-treated) form of pRVK; the DNA sequencing ladder was too faint to be seen in the gel. Lanes A, G, C, and T represent the sequencing ladder obtained in a control sequencing reaction performed by using the same primer on an SC (not Rep68-treated) form of plasmid pRVK. The AAVS1 RBS-trs region is schematically represented at the bottom; the triangle indicates the apparent nicking site, and the arrow indicates the cutting site deduced from the TdT activity of the polymerase (33). (B) Mapping of the nicking site on the AAV-2 ITR contained in SC plasmid psub201. SC plasmid psub201 (1 μg) was converted to the NC form by treatment with 300 ng of Rep68 protein. The nick site in the AAV ITR was mapped as described in the legend to Fig. 3A by using a primer annealing with the 4686–4672 region of the AAV-2 genome contained in plasmid psub201 (48). Reaction products were resolved on an 8% denaturing gel. Lanes 1, 2, 3, and 4 correspond to A, G, C, and T sequencing reactions using Rep68-treated psub201; the DNA sequencing ladder was too faint to be seen in the gel. Lanes A, G, C, and T represent the sequencing ladder obtained by sequencing SC plasmid psub201. The AAV-2 ITR RBS-trs region is also represented; the triangle and arrow indicate the apparent and deduced nicking sites, respectively.

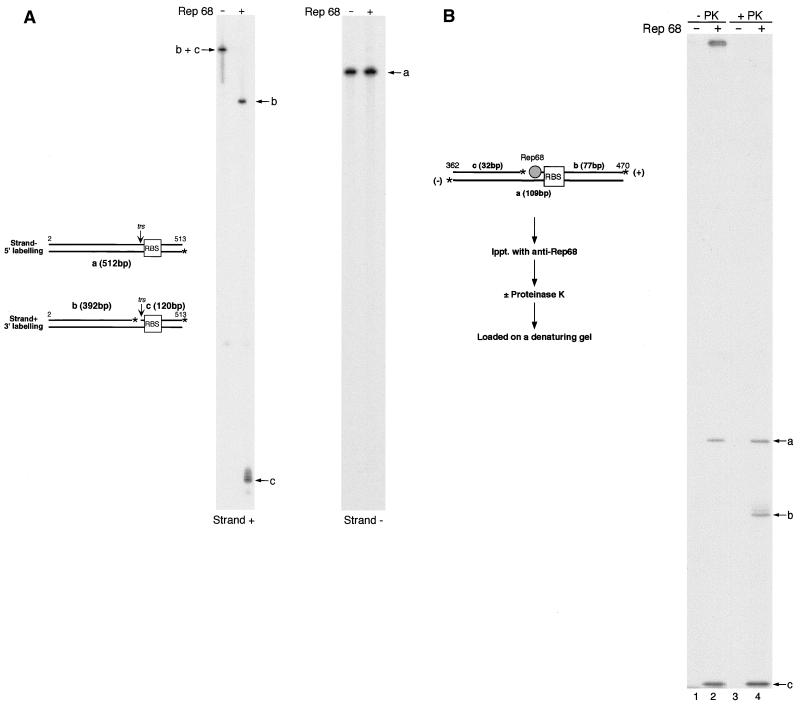

Rep68 cleaves the AAVS1 trs contained in an SC plasmid in a site- and strand-specific manner.

Strand polymerization was not stopped in sequencing reactions performed using as a primer an oligonucleotide annealing with the trs− strand (not shown), suggesting that Rep68 cleavage at the trs was strand specific. This was confirmed in additional experiments. SC pRVK was first converted to NC by treatment with Rep68 and then treated with proteinase K and purified. A 512-bp-long DNA segment containing the RBS and the cleaved trs (schematically represented in Fig. 4A) was then excised and divided into two aliquots; which were selectively labeled at either the trs+ or the trs− strand and resolved on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Figure 4A shows that no cleavage at the trs− strand was observed, while two major fragments were released from the trs+ strand, and their sizes were compatible with cleavage occurred at the trs. However, besides a major released product, additional (from one to two, in different experiments) faint and apparently longer fragments were also detectable (Fig. 4A). It is possible that this observation reflects a low specificity of cleavage at the trs or the presence of contaminating bacterial nucleases in the protein preparation. However, we rather believe that these additional fragments represent the expected 120-bp cleavage product covalently linked at its 5′ end to Rep68 polypeptides of various lengths that remain after proteinase K digestion and reduce the electrophoretic mobility of the DNA segment (18, 52, 60).

FIG. 4.

Strand-specific nicking of SC AAVS1 templates and covalent linkage of Rep68 to the 5′ end of the nicking site. (A) Strand-specific nicking. SC plasmid pRVK (1 μg) was incubated with or without 300 ng of Rep68 for 60 min at 37°C in a standard endonuclease reaction. Following proteinase K digestion, plasmid was purified and digested with restriction enzyme PvuII, which released a fragment containing the AAVS1 RBS-trs region. The two strands of this fragment were selectively labeled in two distinct reactions. The 3′ ends of the fragments derived from the trs+ strand (Strand +) were selectively labeled by using TdT, while the trs− strand (Strand −) was labeled at its 5′ end by treatment with T4 polynucleotide kinase (see Materials and Methods for further details). Labeled products were resolved on a 6% denaturing gel. (B) Covalent linkage of Rep68 to the 5′ end of the nick site. SC plasmid pRVK was incubated with 300 ng of Rep68 in a standard endonuclease reaction. Plasmid was then digested with the restriction enzyme SmaI, and the 3′ ends of the digestion products were 32P labeled with TdT. The double-stranded fragment containing the cleaved trs (shown at the left) was coimmunoprecipitated with the covalently linked Rep68 protein by using an anti-Rep68 polyclonal serum. The immunoprecipitated material was digested (lane 4) or not (lane 2) with proteinase K (PK) and then resolved on a 6% polyacrylamide denaturing gel. In control experiments, SC pRVK was digested with restriction enzyme SmaI, and the digestion products, previously labeled with TdT, were incubated with anti-Rep68 serum. In this case, no labeled material was present in the immunoprecipitate (lane 1 and 3).

To further verify this hypothesis and, more generally, to rule out the possibility that cleavage at the trs was due to a contaminant present in the protein preparation, we checked whether Rep68 established a covalent linkage with the 5′ end of the nick site in an SC AAVS1 template (60). SC pRVK was converted to NC by Rep68, and a fragment spanning the RBS and the cleaved trs was selectively labeled at its 3′ end by using TdT. The labeled fragment (Fig. 4B) was then immunoprecipitated along with the potentially covalently linked Rep68 protein by using a polyclonal anti-Rep68 serum. The immunoprecipitate was treated or not with proteinase K, purified, and resolved on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. As shown in Fig. 4B, in the absence of proteinase K digestion, the cleavage product expected to be Rep68 linked at its 5′ end did not enter the denaturing gel (Fig. 4B, lane 2), indicating that it was tightly associated with a high-molecular-weight material. Upon proteinase K digestion, a major cleavage product (Fig. 4B, lane 4, band b) was detectable. Interestingly, also in this case, one to two additional and fainter fragments were detectable in different experiments, in full agreement with previous results (compare Fig. 4A and B). Taken together, these results demonstrated that Rep68 cleaved the plasmids containing the AAVS1 RBS-trs region at the expected site, in a strand-specific manner and according to molecular mechanisms similar to those already characterized with linear and hairpinned DNA substrates (18, 52, 60).

Rep68 nicking of SC templates is ATP and DNA binding dependent.

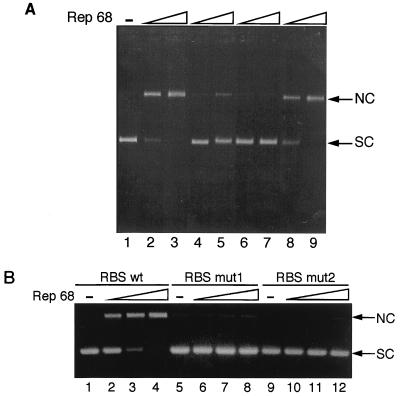

Rep68 nicking activity on an SC template was clearly ATP dependent (Fig. 5A, lanes 2 and 3), although some nicking could be observed in the absence of ATP with high Rep68 concentrations (Fig. 5A, lanes 4 and 5; see Discussion). Notably, the nicking reaction was fully and specifically competed by adding in solution double-stranded oligonucleotides containing the RBS (Fig. 5A, lanes 6 and 7). Furthermore, derivatives of plasmid pBS/trs, called pBSmut1 and pBSmut2, which contain the wild-type trs flanked by binding-deficient mutant of the RBS (35), were not cleaved (Fig. 5B, lanes 5 to 12). These results strongly suggest that binding to the RBS was necessary for nicking.

FIG. 5.

ATP and DNA binding-dependent cleavage of SC pBS/trs. (A) SC pRVK (100 ng) was incubated with 10 ng (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) and 100 ng (lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9) of Rep68 in an endonuclease reaction. Lane 1, SC pRVK; lanes 2 and 3, standard reaction; lanes 4 and 5, no ATP in the reaction buffer; lanes 6 and 7, 200 ng of double-stranded oligonucleotide spanning the RBS added to the reaction buffer; lanes 8 and 9, reaction mixture containing 200 ng of an unspecific double-stranded oligonucleotide. (B) Rep68 (5, 20, and 200 ng) was incubated in a standard endonuclease reaction with 100 ng of plasmids pBS/trs (lanes 1 to 4), pBSmut1 (lanes 5 to 8), and pBSmut2 (lanes 9 to 12). Plasmids pBSmut1 and pBSmut2 contain mutant RBS sequences which have been reported to strongly impair Rep binding (36). See Materials and Methods for further details. wt, wild type.

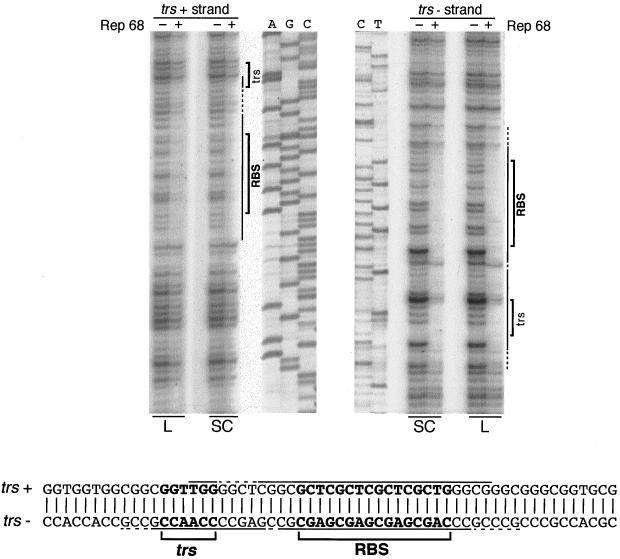

Rep68 footprinting on SC and linear AAVS1 templates.

To test whether the more efficient cleavage on an SC rather than a linear template reflected qualitative differences in the binding mode to the two substrates, DNase I footprinting analyses were performed using either SC or linear forms of a DNA substrate centered on the AAVS1 RBS-trs element. No difference was observed between the two templates: the same regions were protected in the SC and linear template on the trs+ and trs− strands. In both cases, the four repeats of the nonperfect GAGC tetramer constituting the core of the RBS were fully protected (Fig. 6). Footprinting was broader on the trs− strand, where protection spanned the entire trs-complementary sequence and extended up to about 18 bp from the 5′ end of the core of the RBS (Fig. 6). Only partial protection of the trs hexamer was observed on the trs+ strand (Fig. 6). Therefore, the binding features of Rep68 to SC and linear AAVS1 templates are similar and probably do not account for the observed difference in nicking efficiency.

FIG. 6.

Rep68 footprinting on SC and linear AAVS1 templates. SC, supercoiled template, plasmid pRVK; L, linear template, a duplex-linear fragment derived from plasmid pRVK and spanning nt 210 to 513 of AAVS1 (see Materials and Methods). SC and linear templates were incubated with (lanes +) or without (lanes −) purified Rep68 protein and then subjected to DNase I treatment. Primer extensions of digested products were then performed by using thermostable polymerases and a 32P-labeled primer which annealed to the trs+ strand at positions 527 to 510 of AAVS1 (see Materials and Methods for further details). The same primer was also used to perform sequencing reactions to be used as size markers (A, G, and C for the trs+ strand; C and T for the trs− strand). Reaction products were then resolved on a 6% polyacrylamide denaturing gel. Continuous lines indicates the AAVS1 segments fully protected by Rep68; dotted lines indicates partially protected regions.

Mutagenesis of the AAVS1-trs sequence.

Having established a fast and sensitive nicking assay using the SC template, we decided to study the sequence specificity of the Rep68 endonuclease activity in this experimental system. To this end, the wild-type trs sequence (GGTTGG) in the context of plasmid pBS/trs (Fig. 2A) was extensively mutagenized, and the corresponding SC plasmids were used in the nicking assay. Table 1 summarizes the results obtained; the cleavage sites within each trs mutant are also indicated.

TABLE 1.

Efficiencies and sites of cleavage by Rep68 on mutant AAVS1 trs sequences

| trs sequencea | Cleavage efficiencyb | Cleavage sitec |

|---|---|---|

| GGTTGG (wild type) | ++++ | GGT TGG |

| GGCCGG | − | None |

| GGAAGG | − | None |

| GGCTGG | ++ | GGCT GG |

| GGTCGG | +++ | GGT CGG |

| GGATGG | ++ | GGAT GG |

| GGTAGG | +++ | GGT AGG |

| ACTTAC | +++ | ACT TAC |

| CCTTCC | +++ | CCT TCC |

| CCTTGC | +++ | CCT TGC |

| CGTTCC | +++ | CGT TCC |

Derivatives of plasmid pBS/trs containing the indicated trs sequence mutants were challenged with Rep68 protein as indicated in the legend to Fig. 7. For each mutant, the data summarize the results of at least five distinct experiments performed with two different plasmid preparations. In the various experiments, different concentrations of Rep68 were used to allow carefully comparison of the nicking proficiencies of the various mutants.

Calculated with respect to the cleavage efficiency of the wild-type trs sequence: ++++, 100% efficiency; +++, 75% efficiency; ++, 50% efficiency; −, no cleavage.

Determined by the dideoxy sequencing method and by taking into account the TdT activity of Sequenase DNA polymerase (see the legend to Fig. 3).

We first analyzed the effects of mutations in the TT dimer. Substitution of the two thymidine residues with a CC or AA dimer resulted in a complete loss of cleavage (Table 1). In contrast, mutation of only one of the two T residues with an A or a C was quite well tolerated, and the resulting sequences could still be cleaved, although less efficiently than the wild-type sequence (Table 1). However, substitution of the first T residue, which is the 5′ end of the nick site (Fig. 3), was slightly more detrimental than mutation of the second T nucleotide; interestingly, cleavage always occurred 3′ to the remaining thymidine (Table 1). The role of the G residues flanking the TT dimer was also studied. Modifications of the flanking nucleotides did not significantly hamper Rep68 nicking at the trs; in fact, templates in which the guanosines were replaced by either AC or CC dimers (ACTTAC and CCTTCC sequences, respectively) were still nicked by Rep68, although with a slightly reduced efficiency (Table 1). The same applied also to mutants CGTTCC and CCTTGC, in which all but one of the flanking guanosine residues were mutated (Table 1). Taken together, these results demonstrated that the GGTTGG sequence is the best target for Rep68 nicking; nevertheless, several substitutions are tolerated, provided that at least one thymidine is maintained.

Activity of Rep68 on trs positioned at various distances from the AAVS1 RBS.

In AAVS1, the TT dimer within the trs is located at 10 bp from the core of the RBS, as opposed to the 15 bp in the AAV-2 ITRs (18, 60). To test whether the distance between the RBS and the trs might affect the efficiency of cleavage, mutants were generated in the context of plasmid pBS/trs in which the TT dimer, flanked by the wild-type GG dimers, was positioned at distances of 5, 8, 13, 15, and 20 nt from the RBS (5-, 8-, 13-, 15-, and 20-bp mutants, respectively). All but the 20-bp mutant represented excellent substrates for Rep68 nicking and were cleaved as efficiently as the wild type sequence (Table 2). In contrast, the longer-distance 20-bp derivative was still nicked, but with a significantly reduced efficiency (about 10% of the wild-type level). According to our footprinting analysis, in this mutant the trs-complementary region is so far from the RBS core that it should not interact with Rep68 (Fig. 6). This suggests that direct contacts between Rep68 and the trs-complementary sequence might be crucial for Rep68 cleavage at AAVS1 (see Discussion).

TABLE 2.

Rep68 cleavage efficiency at trs sequences placed at various distances from the RBS

| Construct | trs sequencea | Cleavage efficiencyb (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type AAVS1 | CGGTTGGGGCTCGGCGCTC | 100 |

| 5-bp mutant | CGGTTGGGGCGCTC | 100 |

| 8-bp mutant | CGGTTGGGGCTCGGCTC | 100 |

| 13-bp mutant | CGGTTGGGGCTCGGCTCGGCTC | 90 ± 5 |

| 15-bp mutant | CGGTTGGGGCTCGGCTCGGCGCTC | 90 ± 5 |

| 20-bp mutant | CGGTTGGGGCTCGGCTCGGCTCGGCGCTC | 8 ± 2 |

pBS/trs plasmid derivatives (100 ng) containing the indicated sequences were incubated in a standard endonuclease reaction with 30 ng of Rep68 in a standard SC nicking assay. The trs sequence is indicated in bold, and the initial nucleotides of the RBS core are underlined. In all cases, cleavage site was mapped between the T nucleotides (GGT/TGG) by taking into account the TdT activity of Sequenase DNA polymerase (see also the legend to Fig. 3).

Calculated as the percentage of SC plasmid converted to the NC form. This percentage was measured by densitometric analysis of ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels using the Electrophoresis Documentation and Analysis System 120 (Kodak Digital Science). Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of at least three experiments performed with two different plasmid preparations.

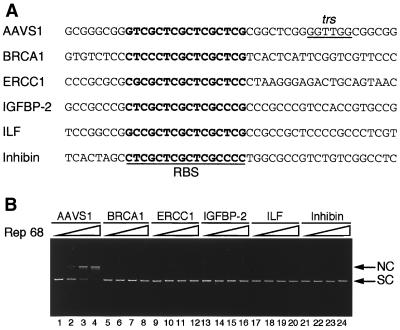

Rep68 does not cleave SC plasmids containing RBSs derived from other regions of the human genome.

Several potential RBSs are present within the human genome, but it is not clear whether these may function as alternative and lower-efficiency AAV-2 integration sites (8, 64, 65). Interestingly, all of these sites are not flanked by a canonical trs (64, 65). However, our finding that some variations of the canonical trs sequence as well as its distance from the RBS do not dramatically affect Rep68 nicking prompted us to verify in the SC nicking assay whether Rep68 could cut also some of these sites. We focused on the RBSs identified in the ERCC1 locus (chromosome 19) and in the genes coding for IGFBP-2 (chromosome 2), inhibin (chromosome 2), ILF (chromosome 17), and BRCA1 (chromosome 17). These sites, to which Rep68 binds as efficiently as or even better than the AAVS1 RBS (reference 68 and data not shown), were selected among several others because AAV-2 integration at chromosomes 2 and 17 has been reported (65). The sequences flanking the selected RBSs (Fig. 7A) include single thymidine residues or TT dimers (BRCA1) which, based on our results, might represent low-efficiency Rep68 cleavage sites. However, none of them were nicked by Rep68 when introduced into SC vectors (Fig. 7B), thus providing additional evidence that AAV-2 site-specific integration is dictated by the capacity of Rep68 to efficiently nick only at the AAVS1 region.

FIG. 7.

Rep68 does not cleave in vitro at selected genomic sites other than AAVS1. (A) Sequences of the RBSs plus flanking regions derived from the human genome and inserted into plasmids (65). The sequences are written in 3′-5′ polarity. See text for further details. (B) Endonuclease reactions were carried out with 5, 20, and 200 ng of Rep68 and 100 ng of SC plasmids carrying the indicated sequences.

Interestingly, also the TT dimer within the CCTTGC sequence and located 15 bp from the RBS in BRCA1 was not cleaved at all (Fig. 7B), while the same sequence was nicked when placed at the wild-type distance of 10 bp from the RBS in the AAVS1 template (CCTTGC mutant [Table 1]). This suggested that at least in our experimental system, some variations from the wild-type trs sequence are tolerated only when the trs is properly positioned with respect to the RBS. In line with this interpretation is the finding that the wild-type GGTTGG sequence but not the CCTTGC hexamer was cleaved by Rep68 when located at 15 bp from the AAVS1 RBS (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report that AAV-2 Rep68 cleavage at the AAVS1 trs is strongly affected by the template topology. A linear double-stranded DNA sequence containing the AAVS1 RBS-trs region is poorly cleaved by Rep68; the same element inserted into an SC plasmid is an excellent template for Rep68 endonuclease. This finding reveals a novel biochemical property of Rep68, suggests the close evolutionary relationship between AAV-2 Rep68 and prokaryotic RCR initiators, and has interesting implications for AAV-2 site-specific integration in vivo. The features of Rep68 nicking at SC AAVS1 trs closely resembles those at the hairpinned ITR trs in terms of specificity and efficiency of cleavage. This validates results of the in vitro SC nicking assay, and we believe that its use will facilitate the elucidation of the molecular mechanisms underlying Rep68 nicking at AAVS1 and, ultimately, of Rep-mediated integration at this site.

The main cleavage site in the SC AAVS1 trs was located between the two T residues (GGT/TGG), in agreement with the cleavage site in the AAV-2 ITR trs (AGT/TGG). Urabe and coworkers (59) have recently reported that in vitro-translated AAV-2 Rep78 cleaves AAVS1 linear substrates at low efficiency not only between the two T residues (GGT/TGG) but also upstream of the first T (GG/TTGG), but we did not observe this fluctuation in the nicking site in our experimental system. The reasons for this partial discrepancy are not clear but might be due to the use of different Rep proteins produced by alternative systems (in vitro-translated Rep78 versus bacterially expressed Rep68).

Mutagenesis of the AAVS1 trs sequence demonstrated that sequence mutations are quite well tolerated and that apparently the only prerequisite for cleavage is the presence of at least one thymidine residue. When only one thymidine is present, cleavage occurs at the 3′ end, with the 5′ end of the nick being an A, C, or G nucleotide (Table 1). It will be of interest to check whether Rep68 also remains covalently linked to nucleotides other than the canonical thymidine. Interestingly, independent substitutions of each of the two thymidine residues of the trs are apparently less detrimental in AAVS1 (Table 1) than in AAV-2 ITRs (5). This might be related to the differences in template topology or might reflect an influence of the flanking regions, as the DNA sequences flanking the AAVS1 trs are different from those flanking the AAV-2 ITR trs (18, 60). It is possible that the sequences surrounding the trs are not functionally inert but affect the efficiency and specificity of nicking, thus compensating for mutations at the target trs in AAVS1.

An interesting question raised by our results is why Rep68 preferentially nicks SC rather than linear AAVS1 templates. This is probably not due to a major difference in binding features. In fact, cleavage of linear substrates was barely detectable even at saturating concentrations of Rep68, which were sufficient to bind all of the DNA template molecules used in the reactions. In addition, footprinting analysis did not reveal any difference in Rep68 protection on both linear and SC templates; therefore, it is probably not major qualitative differences in binding mode that cause preferential cleavage of an SC rather than a linear AAVS1 substrate. Additional experiments and different assays will be required to more carefully address this point and possibly identify more subtle differences in the binding features of the two substrates.

One possible explanation for the high preference exhibited by Rep68 endonuclease for an SC template is provided by analysis of the behavior of other RCR initiators. In the context of SC DNA, RCR initiators cleave preferentially single-stranded substrates that they actively generate, in the majority of cases, by melting the nick region (38). These target regions are either extruded as cruciform elements upon binding of the RCR initiators (37, 44) or centered in an AT-rich region and therefore prone to spontaneous superhelix-driven melting (16).

In the case of AAVS1, no sequences capable of forming stable cruciform structures are present near the RBS and the trs, which is centered in a GC-rich region and thus unlikely to be spontaneously melted by superhelix-driven denaturation (38, 61). However, since Rep68 has both endonuclease and helicase activities, it is possible that sequence requirements for Rep68 cleavage at an SC template are less stringent than for other RCR initiators. It can be hypothesized that upon binding to the RBS, Rep68 might destabilize the trs region and possibly promote its partial extrusion as a single-stranded sequence. In line with this hypothesis is the result of footprinting analysis, which revealed that Rep68 makes contacts with the GGTTGG target sequence on both strands (Fig. 6). The extrusion of a single-stranded trs region is energetically improbable and therefore requires the free energy provided by superhelix twisting (61). Nevertheless, the unstable and possibly short single-stranded trs sequence might well be an effective and properly positioned substrate for the Rep68 ATP-dependent helicase activity which would complete the trs melting process, thus resembling the behavior of the simian virus 40 large-T-antigen helicase (13, 34, 57). Finally, Rep68 nicks the properly positioned single-stranded trs which, as for other RCR initiators, might be the true substrate of the Rep68 endonuclease (38).

Contrary to SC substrates, binding of Rep68 to duplex-linear AAVS1 substrates does not cause the initial extrusion of a single-stranded trs in the absence of the free energy provided by supercoiling; this would explain why Rep68 poorly cleaves double-stranded linear templates (59, 60). In support of this model is the observation that limited nicking at the trs was also observed in the absence of ATP (Fig. 5A), possibly suggesting that in the context of an SC template, the trs sequence has some propensity to be exposed as a single-stranded region and therefore cleaved by Rep68 in an ATP-independent manner (53). More experiments will be required to clarify this issue.

Our in vitro results also have interesting implications for AAV-2 site-specific integrations in vivo. In contrast with the genome of E. coli, which has a net superhelical density (ς) of ≈−0.05 (supercoils per turn), no net superhelical tension appears in the genomes of eukaryotes (50). This is because the negative superhelical stress present in topologically isolated chromatin domains is, on average, restrained by bound nucleosomes (50). Furthermore, the global superhelical state of intracellular DNA is controlled by eukaryotic topoisomerases which relax supercoiling (62). In spite of this, however, it is now very well established that localized regions of unrestrained supercoiling are present in the human chromatin (11, 24, 31, 36). In particular, transcriptionally active DNA contains high levels of localized torsional tension, consistent with the observation that transcription in vivo results in the generation of a twin supercoiled domain with a positively and negatively supercoiled domain, respectively, in front and behind the transcription complex (20, 30, 32, 41, 66). Negative supercoiling, possibly due to the absence of canonical nucleosomes, has also been associated with DNase I-hypersensitive, transcription-regulatory regions (20). Interestingly, a transcribed open reading frame has been detected in the context of AAVS1 (23), and we have recently demonstrated that a DNase I-hypersensitive site with transcriptional enhancer-like properties localizes immediately upstream of the RBS in AAVS1 (26). Therefore, although the specificity of Rep-mediated integration at AAVS1 is primarily dictated by the DNA sequence, it might be facilitated by structural features; possibly (i) the RBS is present in an exposed (DNase I-hypersensitive) region of the chromatin and is therefore potentially easily accessible to Rep78 and Rep68 and (ii) the same region has an SC conformation which would be an optimal substrate for Rep cleavage at the AAVS1 trs. In vitro chromatin reconstitution experiments as well as in vivo determination of DNA topology at AAVS1 will be required to clarify all these issues. Remarkably, a recently developed in vitro assay for Rep68-mediated formation of AAV-2/AAVS1 junctions uses an SC plasmid containing the AAVS1 preintegration locus as the acceptor substrate (9). In light of our results, it would be of interest to check whether the utilization of a linear substrate reduces the efficiency of the process.

Finally, we believe that the SC nicking assay may be useful to identify in vitro alternative, low-efficiency AAV-2 integration sites. Analyzing a few selected RBSs present in the human genome showed that they are not good substrates for Rep68 endonuclease. At this stage, we cannot rule out that cleavage at these sites fails to occur simply because they are efficiently bound by Rep68 when contained in duplex-linear templates (65) but not bound when inserted into an SC plasmid; footprinting analysis would help to resolve this issue. However, we favor the hypothesis that the lack of cleavage does not reflect lack of binding but is due to suboptimal sequence and positioning of the putative trss flanking these alternative genomic RBSs. This is suggested by the observation that the putative CCTTGC trs contained in the BRCA1 substrate is cleaved when located at 10 bp from the AAVS1 RBS (which we have demonstrated to be bound by Rep68 in the context of an SC plasmid) but not when it is placed at 15 bp. This indicates that the specificity and efficiency of Rep68 cleavage is not simply dictated by the trs nucleotide sequence. This decreases the chance that Rep proteins might cleave at sites other than AAVS1. The in vitro nicking assay described in this report will contribute to elucidating the sequence and position requirements for efficient trs nicking in future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Clench for editing the manuscript and M. Emili for contributing graphical work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balagué C, Kalla M, Zhang W-W. Adeno-associated virus Rep78 protein and terminal repeats enhance integration of DNA sequences into the cellular genome. J Virol. 1997;71:3299–3306. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3299-3306.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berns K I. Parvovirus replication. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:316–329. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.3.316-329.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berns K I, Linden R M. The cryptic life stile of adeno-associated virus. Bioessays. 1995;17:237–245. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brister R J, Muzyczka N. Rep-mediated nicking of the adeno-associated virus origin requires two biochemical activities, DNA helicase activity and transesterification. J Virol. 1999;73:9325–9336. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9325-9336.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiorini J A, Wiener S M, Owens R A, Kyöstiö S R M, Kotin R M, Safer B. Sequence requirements for stable binding and function of Rep68 on the adeno-associated virus type 2 inverted terminal repeats. J Virol. 1994;68:7448–7457. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7448-7457.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiorini J A, Weitzman M D, Owens R A, Urcelay E, Safer B, Kotin R M. Biologically active Rep proteins of adeno-associated virus type 2 produced as fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1994;68:797–804. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.797-804.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiorini J A, Yang L, Kotin R M, Safer B. Determination of adeno-associated virus Rep68 and Rep78 binding sites by random sequence oligonucleotide selection. J Virol. 1995;69:7334–7338. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7334-7338.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dyall J, Szabo P, Berns K I. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) site-specific integration: formation of AAV-AAVS1 junctions in an in vitro system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12849–12854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flotte T R, Carter B J. Adeno-associated virus vectors for gene therapy. Gene Ther. 1995;2:357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giaever G N, Wang J C. Supercoiling of intracellular DNA can occurr in eukaryotic cells. Cell. 1988;55:849–856. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giraud C, Winocour E, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus is directed by a cellular DNA sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10039–10043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goetz G, Dean F, Hurwitz J, Matson S. The unwinding of duplex regions in DNA by the simian virus 40 large tumor antigen-associated DNA helicase activity. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:383–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermonat P L, Batchu R B. The adeno-associated virus Rep78 major regulatory protein forms multimeric complexes and the domain for this activity is contained within the carboxy-half of the molecule. FEBS Lett. 1997;401:180–184. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01469-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higashitani A, Greenstein D, Horiuchi K. A single aminoacid substitution reduces the superhelicity requirement of a replication initiator protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:2685–2691. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.11.2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higashitani A, Greenstein D, Hirokawa H, Asano S, Horiuchi K. Multiple DNA conformational changes induced by an initiator protein precede the nicking reaction in rolling circle replication origin. J Mol Biol. 1994;237:388–400. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilyina T V, Koonin E V. Conserved sequence motifs in the initiator proteins for rolling circle DNA replication encoded by diverse replicons from eubacteria, eucaryotes and archaebacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3279–3285. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.13.3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Im D-S, Muzyczka N. The AAV origin-binding protein Rep68 is an ATP dependent site-specific endonuclease with DNA helicase activity. Cell. 1990;61:447–457. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90526-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Im D-S, Muzyczka N. Partial purification of adeno-associated virus Rep78, Rep68, Rep52, and Rep40 and their biochemical characterization. J Virol. 1992;66:1119–1128. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.1119-1128.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jupe E R, Sinden R R, Cartwright I L. Specialized chromatin structure domain boundary elements flanking a Drosophila heat shock gene locus are under torsional strain in vivo. Biochemistry. 1995;34:2628–2633. doi: 10.1021/bi00008a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kearns W G, Afione S A, Fulmer S B, Pang M G, Erikson D, Egan M, Landrum M J, Flotte T R, Cutting G R. Recombinant adeno-associated (AAV-CTFR) vectors do not integrate in a site-specific fashion in an immortalized epithelial cell line. Gene Ther. 1996;3:748–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotin R M, Siniscalco M, Samulski R J, Zhu X D, Hunter L, Laughlin C A, Laughlin S M, Muzyczka N, Rocchi M, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2211–2215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotin R M, Linden R M, Berns K I. Characterization of a preferred site on human chromosome 19q for integration of adeno-associated virus DNA by non-homologous recombination. EMBO J. 1992;11:5071–5078. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kramer P R, Sinden R R. Measurement of unrestrained negative supercoiling and topological domain size in living human cells. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3151–3158. doi: 10.1021/bi962396q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamartina S, Roscilli G, Rinaudo D, Delmastro P, Toniatti C. Lipofection of purified adeno-associated virus Rep68 protein: toward a chromosome targeting nonviral particle. J Virol. 1998;72:7653–7658. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7653-7658.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamartina S, Sporeno E, Fattori E, Toniatti C. Characteristics of the adeno-associated virus preintegration site in human chromosome 19: open chromatin conformation and transcription-competent environment. J Virol. 2000;74:7671–7677. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7671-7677.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linden R M, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus: a basis for a potential gene-therapy vector. Gene Ther. 1997;4:4–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linden R M, Winocour E, Berns K I. The recombination signals for adeno-associated virus site-specific integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7966–7972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linden R M, Ward P, Giraud C, Winocour E, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11288–11294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu L F, Wang J C. Supercoiling of the DNA template during transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7024–7027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ljungman M, Hanawalt P C. Localized torsional tension in the DNA of human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6055–6059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ljungman M, Hanawalt P C. Presence of negative torsional tension in the promoter region of the transcriptionally poised dihydrofolate reductase gene in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1782–1789. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.10.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Llosa M, Grandoso G, de la Cruz F. Nicking activity of TrwC directed against the origin of transfer of the IncW plasmid R388. J Mol Biol. 1995;246:54–62. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lohman T M, Bjornson K P. Mechanisms of helicase-catalyzed DNA unwinding. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:169–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCarty D M, Pereira D J, Zolotukhin I, Zhou X, Ryan J H, Muzyczka N. Identification of linear DNA sequences that specifically bind the adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J Virol. 1994;8:4988–4997. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4988-4997.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michelotti G A, Michelotti E F, Pullner A, Duncan R C, Eick D, Levens D. Multiple single-stranded cis elements are associated with activated chromatin of the human c-myc gene in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2656–2669. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noirot P, Bargonetti J, Novick R. Initiation of rolling-circle replication in pT181 plasmid: initiator protein enhances cruciform extrusion at the origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8560–8564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novick, R. P. Contrasting lifestyles of rolling-circle phages and plasmids. Trends Biol. Sci. 23:434–438. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Palombo F, Monciotti A, Recchia A, Cortese R, Ciliberto G, La Monica N. Site-specific integration in mammalian cells mediated by a new hybrid baculovirus–adeno-associated virus vector. J Virol. 1998;72:5025–5034. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5025-5034.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pansengrau W, Schoumacher F, Hohn B, Lanka E. Site-specific cleavage and joining of single-stranded DNA by VirD2 protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmids: analogy to bacterial conjugation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11538–11542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rahmouni A R, Wells R D. Direct evidence for the effect of transcription on local DNA supercoiling in vivo. J Mol Biol. 1992;223:131–144. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90721-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Recchia A, Parks R J, Lamartina S, Toniatti C, Pieroni L, Palombo F, Ciliberto G, Graham F L, Cortese R, La Monica N, Colloca S. Site-specific integration mediated by a hybrid adenovirus/adeno-associated virus vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2615–2620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rinaudo D, Lamartina S, Roscilli G, Ciliberto G, Toniatti C. Conditional site-specific integration into human chromosome 19 by using a ligand-dependent chimeric adeno-associated virus/Rep protein. J Virol. 2000;74:281–294. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.281-294.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruzhong J, Fernandez-Beros M-E, Novick R P. Why is the initiation nick site of an AT-rich rolling circle plasmid at the tip of a GC-rich cruciform? EMBO J. 1997;16:4456–4466. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryan J H, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N. Sequence requirements for binding of Rep68 to the adeno-associated virus terminal repeats. J Virol. 1996;70:1542–1553. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1542-1553.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samulski R J. Adeno-associated virus: integration at a specific chromosomal locus. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:74–80. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80344-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samulski R J, Zhu X, Xiao X, Brook J D, Housman D E, Epstein N, Hunter L A. Targeted integration of adeno-associated virus (AAV) into human chromosome 19. EMBO J. 1991;10:3941–3950. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04964.x. . (Erratum, 11:1228, 1992.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samulski R J, Chang L S, Shenk T. A recombinant plasmid from which an infectious adeno-associated virus genome can be excised in vitro and its use to study in vitro replication. J Virol. 1987;61:3096–3101. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3096-3101.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shelling A N, Smith M G. Targeted integration of transfected and infected adeno-associated virus vectors containing the neomycine resistance gene. Gene Ther. 1994;1:165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sinden R R, Carlson J O, Pettijohn D E. Torsional tension in the DNA double helix measured with trimethylpsoralen in E. coli cells: analogous measurements in insect and human cells. Cell. 1980;21:773–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith R H, Spano A J, Kotin R M. The Rep78 gene product of adeno-associated virus (AAV) self-associates to form a hexameric complex in the presence of AAV ori sequences. J Virol. 1997;71:4461–4471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4461-4471.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Snyder R O, Im D-S, Muzyczka N. Evidence for covalent attachment of the adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep protein to the ends of the AAV genome. J Virol. 1990;67:6096–6104. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6204-6213.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Snyder R O, Im D-S, Ni T, Xiao X, Samulski R J, Muzyczka N. Features of the adeno-associated virus origin involved in substrate recognition by the viral Rep protein. J Virol. 1993;67:6096–6104. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6096-6104.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Snyder R O, Samulski R J, Muzyczka N. In vitro resolution of covalently joined AAV chromosome ends. Cell. 1990;60:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90720-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Srivastava A, Lusby E W, Berns K I. Nucleotide sequence and organization of the adeno-associated virus 2 genome. J Virol. 1983;45:555–564. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.2.555-564.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Surosky R T, Urabe M, Godwin S G, McQuiston S A, Kurtzman G J, Ozawa K, Natsoulis G. Adeno-associated virus Rep proteins target DNA sequences to a unique locus in the human genome. J Virol. 1997;71:7951–7959. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7951-7959.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsurimoto T, Melendy T, Stillman B. Sequential initiation of lagging and leading strand synthesis by two different polymerase complexes at the SV40 DNA replication origin. Nature. 1990;346:534–539. doi: 10.1038/346534a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tugores A, Brenner D A. A method for in vitro DNAsel footprinting analysis on supercoiled templates. BioTechniques. 1994;17:410–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Urabe M, Hasumi Y, Kume A, Surosky R T, Kurtzman G J, Tobita K, Ozawa K. Charged-to-alanine scanning mutagenesis of the N-terminal half of adeno-associated virus type 2 Rep 78 protein. J Virol. 1999;73:2682–2693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2682-2693.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Urcelay E, Ward P, Wiener S M, Safer B, Kotin R M. Asymmetric replication in vitro from a human sequence element is dependent on adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J Virol. 1995;69:2038–2046. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2038-2046.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vologodskii A V, Cozzarelli N R. Conformational and thermodynamic properties of supercoiled DNA. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1994;23:609–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.23.060194.003141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Z, Dröge P. Differential control of transcription-induced and overall DNA supercoiling by eukaryotic topoisomerases in vitro. EMBO J. 1996;15:581–589. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weitzman M D, Kyöstiö S R, Kotin R M, Owens R A. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins mediate complex formation between AAV DNA and its integration site in human DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5808–5812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wonderling R S, Owens R. The Rep68 protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 stimulates expression of the platelet-derived growth factor B c-sis proto-oncogene. J Virol. 1996;70:4783–4786. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4783-4786.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wonderling R S, Owens R. Binding sites for adeno-associated virus Rep proteins within the human genome. J Virol. 1997;71:2528–2534. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2528-2534.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu H-Y, Shyy S, Wang J C, Liu L F. Transcription generates positively and negatively supercoiled domains in the template. Cell. 1988;53:433–440. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu J, Davis M D, Owens R. Factors affecting the terminal resolution site endonuclease, helicase, and ATPase activities of adeno-associated virus 2 Rep protein. J Virol. 1999;73:8235–8244. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8235-8244.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang C C, Xiao X, Zhu X, Ansardi D C, Epstein N D, Frey M R, Matera A G, Samulski R J. Cellular recombination pathways and viral terminal repeat hairpin structures are sufficient for adeno-associated virus integration in vivo and in vitro. J Virol. 1997;71:9231–9247. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9231-9247.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhou X, Zolotukhin I, Im D-S, Muzyczka N. Biochemical characterization of adeno-associated virus Rep68 DNA helicase and ATPase activities. J Virol. 1999;73:1580–1590. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1580-1590.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]