Abstract

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), the most plastic cells of the hematopoietic system, exhibit increased tumor-infiltrating properties and functional heterogeneity depending on tumor type and associated microenvironment. TAMs constitute a major cell type of cancer-related inflammation, commonly enhancing tumor growth. They are profoundly involved in glioma pathogenesis, contributing to many cancer hallmarks such as angiogenesis, survival, metastasis, and immunosuppression. Efficient targeting of TAMs presents a promising approach to tackle glioma progression. Several targeting options involve chemokine signaling axes inhibitors and antibodies, anti-angiogenic factors, immunomodulatory molecules, surface immunoglobulins blockers, receptor and transcription factor inhibitors, as well as microRNAs (miRNAs), administered either as standalone or in combination with other conventional therapies. Herein, we provide a critical overview of current therapeutic approaches targeting TAMs in gliomas with the promising outcome.

Keywords: Tumor-associated macrophages, glioma, immunotherapy, CSF-1R, angiogenic factors, CCR2/CCL2, liposomes

1. INTRODUCTION

Gliomas are derived from neuroglial progenitor cells or stem cells, presenting 81% of malignant brain tumors. Based on their histological morphology, they can be classified as astrocytic, ependymal, or oligodendroglial tumors, exhibiting different degrees of malignancy (WHO grades I-IV) along with additional parameters such as proliferation index, genetic alterations, tumor mass extension, necrosis, and microvascular proliferation [1]. Although they are relatively rare, gliomas exhibit significant mortality and morbidity. Glioblastomas are grade IV tumors, presenting the commonest (∼45%) glioma type, with only ∼5% of patients reaching the 5-year relative survival rate [2]. Among the main reasons for treatment resistance is the invasive growth of gliomas which is highly regulated and enhanced by alterations in the tumor microenvironment (TME).

Recently, the role of TME in glioma pathogenesis has received increased scientific attention and research efforts, being highly implicated in tumor growth and progression and paving the way for future therapies. TME consists of stromal cells (connective tissue and immune cells, as well as vascular components) that can interact with inflammatory cells, facilitating tumor development, progression, and degree of malignancy [3]. Upon brain inflammation, the surrounding tissues are infiltrated by microglia, and bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs), which enable tumor progression by generating an immunosuppressive TME [4]. In addition, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are often increased in gliomas, inhibiting the function of T cells, and inducing the formation of regulatory T cells (Tregs). Particularly in glioblastomas (GBM), from early stages, there is a severe T cell dysfunction with CD4+ T helper (Th), CD8+, and CD4 Tregs being all re-programmed in the immunosuppressive microenvironment. In the perivascular space, the resident glioma stem cells (GSCs) can recruit many more TAMs by releasing periostin in the perivascular niche and serving as a chemoattractant of TAMs through the integrin receptor ανβ3. GSCs supernatants inhibit the phagocytic function of TAMs and induce TGF-β and interleukin-10 secretion [5]. Except for the treatment resistance of cancer cells, glioma stem cells are also heterogeneous and exhibit resistance to DNA damage caused by traditional therapies, including radiotherapy and temozolomide (TMZ) administration [6].

2. ROLE OF TAMS IN GLIOMA PATHOGENESIS

TAMs represent the most abundant population of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in the TME. They derive from bone marrow monocytes or erythroid-myeloid progenitors (EMPs) originating from the yolk sac during embryonic stages [7].

They are classified as M1- and M2-type polarized macrophages, exhibiting anti-tumor or pro-tumor activity, respectively. They can be activated by hypoxia, T cell-derived cytokines, growth factors, chemokines, and metabolites in the TME. In particular, the M1-like TAMs are stimulated by a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IFN-γ, lipopolysaccharides (LPS), and Transforming growth factor-alpha (TGF-α), which act through the transcription factors Stat1, interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1), as well as IRF5 to stimulate the production of pro-inflammatory anti-tumor cytokines and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). The M2-like TAMs are stimulated by IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, lactic acid and TGF-β, which act on the transcription factors Klf2/4, Stat3/6 and IRF3/5 through the activation of arginase1-dependent metabolism of arginine. Neurofibromatosis type I (NF1) has been related to the recruitment of TAMs in GBM [6]. The predominance of M1-like cells represents the pro-inflammatory phenotype which is involved in Th1 response to pathogens release of ROS/RNS, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α), IL-6, IL-1β, IL-23, IL-12, and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9), CXCL10, being associated with tumor regression. The predominance of M2-like cells represents the anti-inflammatory phenotype, which is involved in the Th2 response, releasing cytokines such as IL-10, IL-13, TGFβ, C-C motif chemokine ligand 17 (CCL17), CCL18, -22, -24, and is associated with immunosuppression and chemoresistance, resulting in tumor progression [7-9]. The M2-like TAMs can be subdivided into four distinct groups, the M2a related to Th2 response in inflammation, M2b associated to Th2 activation in immunoregulation, M2c involved in matrix deposition, tissue remodeling, anti-inflammation, immunoregulation and M2d associated with tissue remodeling, tissue repair and angiogenesis [9].

2.1. TAMs Implication in Tumor Metastasis

TAMs are also responsible for establishing an invasive TME through the secretion of epidermal growth factor (EGF) family ligands, metalloproteinases (MMPs), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), and wingless/integrated (WNT) from macrophages and colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) from cancer cells [7]. TAMs enhance angiogenesis through the production of VEGFA and placental growth factor (PlGF), which in comparison with normal tissues has a vascular network with distorted and enlarged vessels, erratic blood flow, microhemorrhages, and excessive vessel branching. The final step of tumor progression involves the process of metastasis, consisting of 4 stages, namely epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), intravasation, extravasation, and colonization. At first, primary tumor cells, including macrophages, produce factors such as lysyl oxidase, placental growth factor (PlGF), and exosomes in order to form the premetastatic niche and prepare the secondary site of metastasis for the transport of disseminated tumor cells, while contributing to the EMT pathway. Macrophages-derived cathepsins aid in cell adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins, enabling tumor cell migration. Cancer cells secrete CSF1, which stimulates macrophages to produce epidermal growth factor and upon the secretion of VEGF-A and CCL2 to intravasate and in turn extravasate, retaining the metastatic-associated macrophages (MAMs) at the site, forming a metastatic niche and promoting further colonization [10].

2.2. Immunosuppressive Role of TAMs

The presence of TAMs in the TME can eliminate antitumoral immune cells and increase immunosuppressive cells by interacting with the cytotoxic T cell population. The main target of TAMs is CD8+ T cells which activate apoptosis and release inflammatory cytokines as well as chemokines in order to create an unfavorable microenvironment for cancer cells. In this way, TAMs suppress CD8+ T cell activation in several ways, including depletion of metabolites needed for T cell proliferation, inhibition of T cell functions by inducing anti-inflammatory cytokines production, and enabling T cell checkpoint blockade through the engagement of inhibitory receptors. Additionally, MDSCs inhibit cytotoxic responses of natural killer cells and limit CD4+ Th cell activation [8,11].

Based on this evidence, TAMs are considered potential targets for immunotherapy, aiming to overcome their immunosuppressive and pro-tumoral functions. Current therapeutic strategies include the reduction of TAMs by depleting the already existing ones, prevention of TAMs accumulation by blocking their trafficking to tumor location, and re-education of TAMs to the M2-like antitumoral phenotype [8].

3. TARGETING OPTIONS OF TAMs ACTIVITY

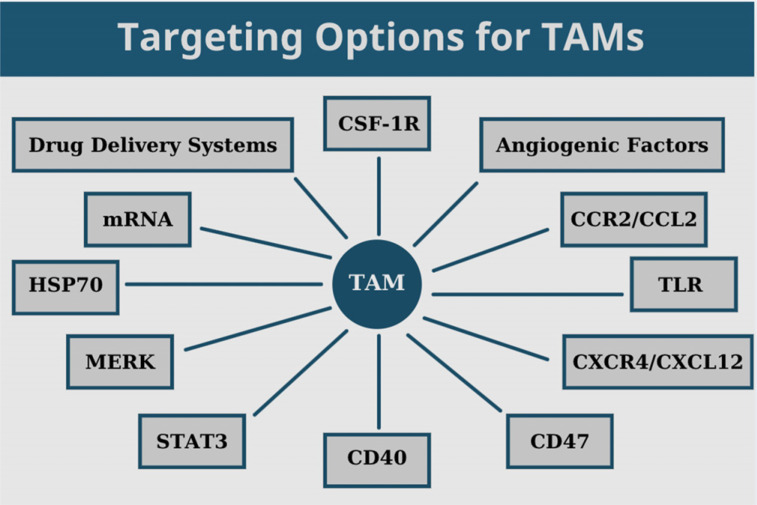

Several possible ways have been investigated to deplete TAMs and open new horizons for the treatment of gliomas. In this section, we discuss the effects of radiation and current experimental data focused on targeting CSF-1R, angiogenic factors, CCR2/CCL2 and CXCR4/CXCL12 signaling axes, TLR, CD47, CD40, STAT3, MERK, and HSP70 in gliomas (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Fig. (1).

Current targeting options of TAMs in gliomas.

Table 1.

Drugs targeting TAMs in gliomas.

| Drug Name | Target | Main Functions | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLX3397 (Pecidartinib) | CSF-1R, c-KIT, FLT3, and c-Fms | Depletes Iba-1+ and CD11b+ macrophages, potentiating the response of intracranial tumors to irradiation, reducing tumor infiltration of GAMs | Alone didn’t show high efficacy. Suggested to be used in combination with radiation treatment | [13-18] |

| BLZ945 | CSF1R | Alters macrophage polarization and blocks glioma progression, enhancing CD8+ T cell infiltration | Not TAM specific, being substantially toxic. Better results when used in combination with IGF1R and PI3K inhibitors | [7] |

| IMC-CS4 | CSF1R | Alters macrophage polarization and blocks glioma progression in advanced solid tumors | Alone showed no efficacy | [20] |

| FPA008 (Cebiralizumab) | CSF1R | Alters macrophage polarization and blocks glioma progression in advanced solid tumors | Unknown | [7, 21] |

| RG7155 (Emactuzumab) | CSF1R | Alters macrophage polarization and blocks glioma progression in advanced solid tumors | CD206+ TAMs are less susceptible to RG7155 than other M2-like TAM subsets | [22] |

| R05509554 | CSF1R | Alters macrophage polarization and blocks glioma progression in advanced solid tumors | Unknown | [7] |

| Cediranib | VEGFR1-3 | Inhibits tumor growth and prolongs vessel normalization. Reprograms M2-like TAMs to M1-like TAMs | Combined with MEDI3617 prolongs survival | [28] |

| Axitinib | VEGFR1-3, PDGFR-α/β, c-Kit | Inhibits the metronomic cyclophosphamide, activating antitumor innate immune response. Shifts TAMs into an M2-like phenotype | Unknown | [13] |

| Bevacizumab | VEGFA | Induces Tie-2+ monocyte infiltration and vast infiltration of M2-like macrophages. Enhances hypoxia and radiation-induced necrosis, increases phosphorylation of STAT3 in macrophages, and promotes a tumor supportive phenotype | Innate immune cells can develop resistance to bevacizumab treatment, so its combination with an Ang-2 inhibitor may overcome that resistance | [13, 30-35] |

| Crossmab/A2V/MEDI3617 | Angiopoietin-2/ VEGFA bispecific | Normalizes tumor vasculature and prolongs survival in glioblastoma by altering macrophages functions | Unknown | [13] |

| Sunitinib | VEGFR1-3, CSF-1R, c-Kit, Flt-3, and PDGFR-α/β | Induces hypoxia which increased macrophage infiltration |

Unknown | [13] |

| Flavonoid 16 (FLA-16) | CYP4A, CYP4X1 | Decreases tumor burden and prolongs survival through normalization of glioma vasculature | Unknown | [40, 41] |

| anti-CHI3L1 | CHI3L1 | Inhibits tube formation of microvascular endothelial cells, accelerates the apoptosis of glioblastoma U87 inducing cell death, decreased tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis in a xenograft model | Rapamycin, STAT3 inhibitor, radiation can be combined with anti-CHI3L1 | [42] |

| Carlumab | CCL2 | Stimulates tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis |

Low binding affinity of carlumab results in large amount of free CCL2, lowering its clinical efficacy | [43] |

| MTZ regimen | MCP-1 | Blocks MCP-1, inhibiting their migration to tumor milieu and differentiation of MLC to M2 macrophages |

Hyperpigmented skin | [46] |

| PLX7486 | TRKA/B/C, CSF-1R | Inhibits recruitment of TAMs in the TME affecting the survival of TAMs | Unknown | [47] |

| Paclitaxel | TLR4 | Antiproliferative drug that induces the re-education of M2-like macrophages to M1-like TAMs | If cell lacks TLR4 it doesn’t exert its function and these cells produce NF-kB, thus a TLR4 antagonist should be administered |

[56] |

| IMO-2055 | TLR9 | Reprograms M2-like TAMs to M1-like TAMs | Alone doesn’t have an impact on tumor progression | [57] |

| AMD3100 (Plerixafor) | CXCR4 | Blocks the infiltration of Tie-2+ monocytes, inducing the reduction of GAM recruitment via inhibition of chemotaxis | Has also agonistic activity on CXCR7. Long-term cardiotoxicity has been reported | [13, 58] |

| Peptide R | CXCR4 | Reduces tumor cellularity, promoting the polarization of M2-like TAMs to M1-like TAMs | Unknown | [58] |

| USL311 | CXCR4 | Reprograms immunosuppressive myeloid cell populations and/or fostering anti-tumor immune responses in the tumor microenvironment in advanced solid tumors |

Unknown | [59] |

| Hu5F9-G4 | CD47 | Enhances macrophage-dependent phagocytosis of glioblastoma cells | Effective only in combination with irradiation or TMZ chemotherapy |

[64] |

| Gemcitabine | CD40, HLA-DR, CCR7, CD163, CD206 | Induces anti-tumor immunity and tumor regression | Its efficacy can be improved by ways to increase plasma half-life, BBB penetration, drug concentration at target site and reduction of its toxicity | [45, 65] |

| Corosolic acid | CD163, IL-10 | Inhibits the proliferation of glioblastoma cells, U373 and T98G, and the activation of signal transducer and activator STAT3 and NF‐κB in both human macrophages and glioblastoma cells | Should be combined with an anticancer agent | [66] |

| WP1066 | STAT3 | M1-like polarization through STAT3 blocking and selectively induce apoptosis | Cell population independent of STAT3 growth is not affected | [67] |

| UCN2025 | MerTK | Reduces clonal expansion, colony forming potential, neurosphere diameter of glioblastoma cells, and induces cell death and polyploidy in glioblastoma cells | Alone didn’t increase survival | [68, 69] |

| PROS1 | MERKT | Induces apoptosis and reduces proliferation of GBM cells | Unknown | [70] |

| BGB324 | AXL | Decreases tumor growth and prolongs the survival of immunocompromised mice bearing GSC-derived mesenchymal GBM-like tumors. | It should be combined with Nivolumab to increase survival | [71] |

| Tamoxifen | AKT, JNK | Induces TAM proptosis | Resistance has been reported in certain types of GBM | [73, 74] |

| SR-A1 | HSP70 | Re-educates M2-like macrophages to M1-like TAMs | Might be suppressed by glioma microenvironment | [77] |

| ARRY-382 | CSF1R | Inhibits recruitment of TAMs in the TME affecting the survival of TAMs in advanced solid tumors | Unknown | [109] |

| CC-90002 | CD47 | Inhibits recruitment of TAMs in the TME affecting the survival of TAMs, enhancing antibody-dependent phagocytosis of tumor cells in advanced solid tumors | Unknown | [110] |

| TTI-624 | CD47 | Inhibits recruitment of TAMs in the TME affecting the survival of TAMs, enhancing antibody-dependent phagocytosis of tumor cells in advanced solid tumors |

Unknown | [111] |

| CP-870,893 | CD40 | Inhibits recruitment of TAMs in the TME affecting the survival of TAMs in advanced solid tumors | Should be combined with Paclitaxel and Carboplatin | [112] |

| RO7009789 | CD40 | Inhibits recruitment of TAMs in the TME affecting the survival of TAMs in advanced solid tumors | Should be combined with Atezolizumab |

[113] |

The front-line treatment for glioblastomas is radiation therapy (RT), but tumor recurrence is commonly observed, limiting its clinical success. Recurrence has been attributed to increased numbers of TAMs along with stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) expression and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) elevation, enabling tumor invasion. On the contrary, there is evidence of specific tumor types such as SDFkd with suppressed SDF-1 expression, which present decreased invasiveness, and enable mice survival. These SDFkd tumors exhibit lower microvascular density (MVD) and reduced TAM numbers when compared to irradiated ALTS1C1 tumors, which are derived from primary astrocytes upon transformation by the SV40 large T antigen (LTA) [12].

3.1. Targeting of the Colony-stimulating Factor 1 Receptor (CSF-1R)

The colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF-1R) belongs to the tyrosine kinase receptor family expressed in TAMs. Physiologically, the activation of this receptor promotes the proliferation of macrophages via intracellular signaling. Therapeutic strategies for TAMs elimination, involve administration of antibodies targeting CSF-1R or CSF-1 inhibitors including Pexidartinib (PLX3397, PLX10801), BLZ945, Cebiralizumab (FPA008), MSC110, Emactuzumab (RG7155), 820, IMC-CS4 (LY3022855) and PD-0360324.

PLX3397 is a c-kit, c-Fms inhibitor (CFR-1 blocker) which affects TAM numbers in recurrent GBM by depleting Iba-1+ and CD11b+ macrophages, potentiating the response of intracranial tumors to irradiation [13, 14] and reducing tumor infiltration of GAMs [15-17], but showed no significant improvement in efficacy in GBM compared to controls, although it was well-tolerated and crossed the blood-tumor barrier readily [18].

BLZ945 is a CSF1 inhibitor which alters the polarization of macrophages and inhibits the progression of gliomas by enhancing CD8+ T cell infiltration. It exerts beneficial effects in survival when used in combination with phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) inhibitors, alone or combined with anti-PD1 antibody PDR001 [7]. Recently, irradiation (IR+) continuous CSF-1R inhibition by BLZ945 was shown to potentiate the initial glioma-regressive effects of radiotherapy by reverting the microglia/monocyte-derived macrophages IR-associated phenotype. Comparing short with long-term CSF-1R inhibition, the latter showed improved survival in gliomas [19].

Other CSF-R1 inhibitors which are currently under study include IMC-CS4 [20], FPA008 [21], and RG7155/ R05509554 administered in advanced solid tumors, altering macrophage polarization and blocking glioma progression [7, 22, 23].

The nuclear NF-κB activating protein (NKAP) is overexpressed in gliomas, promoting tumor growth through the generation of a Notch1-dependent immunosuppressive TME. By inhibiting NKAP, the recruitment and polarization of TAM are reduced due to decreased production of M-CSF and SDF-1 [24]. By inhibiting NF-κB signaling in myeloid cells, the cellular microenvironment is transformed into an immune-competent host, suggesting that a combined treatment of TMZ and a pharmacological NF-κB inhibitor may prove beneficial for GBM patients [25].

3.2. Targeting of Angiogenic Factors

One of the most important pro-tumoral functions of macrophages is to promote angiogenesis. VEGF exhibits pro-angiogenic function, along with anti-apoptotic and mitogenic effects on endothelial cells. Since VEGF induces vascular permeability and promotes cell migration, it has been suggested that inhibition of angiogenesis in cancer using anti-VEGF and anti-VEGFRs agents can be very effective [26].

Anti-VEGFA antibody injection in mice with GBM was shown to induce a reduction in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) infiltration as detected by intravital 2 photon imaging [27]. It was demonstrated in murine GBM models that the dual inhibition of endothelial cell-derived angiopoietin-2 (Ang2) and VEGFRs inhibited the growth of tumors and enhanced the normalization of vessels compared to single VEGFR inhibition, improving survival. The anti-VEGFR/Ang-2 treatment was shown to be more effective than Cediranib monotherapy in enhancing vessel normalization in Gl261 cells and in U87 tumors, most possibly mediated by TAMs since CSF-1 was blocked upon monotherapy in G1261 cells [28].

Axitinib which targets VEGFR1-3, PDGFR-β and c-Kit was further investigated in a murine glioma xenograft model and was shown to induce inhibition of metronomic cyclophosphamide and shift TAMs into an M2-like phenotype to induce antitumor innate immunity [13].

Additionally, Bevacizumab targets VEGFA in GBM, and was shown to induce infiltration of Tie-2+ monocyte and M2-like macrophages [29, 30], increasing STAT3 phosphorylation in macrophages, and promoting tumorigenesis [31]. Bevacizumab restored the immune-supportive tumor microenvironment in GBM, which persisted during long-term therapy [32]. In murine and human gliomas, Bevacizumab and aflibercept were demonstrated to reduce the effects of VEGFA and increase Tie-2+ and CD206+ macrophages by increasing Ang2 levels. Upon inhibition of Ang2 and administration of bevacizumab or aflibercept, the therapeutic efficacy was significantly improved [33]. However, during the anti-angiogenic therapy, MIF depletion was often observed, leading to increased levels of TAMs and M2 polarization, resulting in resistance to treatment [34]. Bevacizumab enhanced hypoxia and radiation-induced necrosis in TME. Increased hypoxia levels further enhance the glycolytic pathway of tumors and allow the positive selection of neoplastic microglia/macrophages with higher invasive properties, further indicating that therapeutic approaches with bevacizumab and radiation possibly enable tumor progression [35].

Crossmab and A2V target angiopoietin 2/ VEGFA bispecific in glioblastomas. The MEDI3617 Angiopoietin-2 also demonstrated the same potential when it was co-administered with cediranib.

Sunitinib which targets c-Kit, Flt-3, CSF-1R, VEGFR1-3 and PDGFR-α/β, was investigated in human recurrent GBM and was shown to induce more severe hypoxia, increasing macrophage infiltration [13].

A study of gene-modified human glioma cells by retrovirus showed that secretion of hK5His protein inhibited endothelial cell migration in vitro, also blocking glioma-associated angiogenesis and possessing novel anti-macrophage properties. Moreover, it was demonstrated that glioma-targeted hK5His expression suppressed cancer growth and increased survival in a brain cancer animal model [36].

Another therapeutic approach was shown to affect indirectly TAMs involved in GSCs that reside in perivascular and hypoxic niches, secreting factors like VEGF, bFGF, SDF1, HIF2a, that enable macrophages growth, inducing TAM polarization into the M2 immunosuppressive phenotype [37]. Since neo-angiogenesis is an important hallmark of cancer, anti-angiogenic agents were considered as a potential ally in the treatment of solid tumors and especially GBM.

Trials are currently in progress evaluating therapeutic approaches based on the monocyte chemotactic protein-3 (MCP3), which is highly expressed in human gliomas. SDF-1, acting via the CXCR4 receptor, was demonstrated to induce macrophages recruitment in the tumor stroma of murine models, further suggesting that SDF-1 targeting may improve the efficacy of anti-VEGF treatment [38, 39].

The Flavonoid 16 (FLA-16) was demonstrated to normalize tumor vasculature in gliomas by inhibiting CYP4A and CYP4X1 and therefore increase survival. Moreover, in U87 and C6 gliomas, FLA-16 was shown to decrease 20-HETE, TGF-β and VEGF production from TAMs as well as from endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), decrease tumor burden, and increase survival. This evidence suggests that targeting TAMs and EPCs may prove beneficial in overcoming resistance to anti-VEGF therapy [40]. CYP4X1 inhibition by the flavonoid CH625 was shown to normalize glioma vasculature through reprogramming of TAMs via the cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2) and the EGFR-STAT3 axis [41].

The non-enzymatic chitinase-3 like-protein-1 (CHI3L1) has been involved in tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis, as well as in TAM activation and CD4+ T cells Th2 polarization. Moreover, CHI3L1 is overexpressed in macrophages of GBM patients. A neutralizing antibody of CHI3L1 was shown to inhibit microvascular endothelial cells tube formation, abolish expression of VEGF receptor 2, and enhance U87 GBM cells apoptosis upon exposure to γ-irradiation. By blocking the Akt signaling pathway, it was shown to induce cell death, reduce tumor growth and angiogenesis as well as metastasis in a xenograft model. Furthermore, the inhibition of CHI3L1 blocked the invasive properties and restored, to some extent, the TMZ sensitivity of temozolomide-resistant (TMZ-R) glioblastomas. Additionally, STAT3 blockade by STX-0119 reduced CHI3L1 expression and inhibited TMZ-R U87 cells growth. Combined treatment with rapamycin, STAT3 and mTOR inhibitors significantly reduced the proliferation of TMZ-R relapsed gliomas by targeting the respective signaling pathway [42].

3.3. Targeting of CCR2/CCL2 Signaling Axis

The importance of CCR2/CCL2 signaling molecules is attributed to their involvement in the transport of macrophages from the bone marrow to the tumor site. Targeting agents include carlumab, MTZ-regimen, PLX7486, PF-04136309, MLN1202, CCX872-B and BMS-813160.

Carlumab, a human immunoglobulin G1κ monoclonal antibody that binds to CLL2, has shown preliminary antitumor activity in patients with solid tumors [43-45].

MTZ-regimen involves a low-toxicity cytokine that blocks MCP-1, which is an agonist of CCR2. Glioblastoma cells release MCP-1 inducing chemotactic migration of MLCs to tumor milieu and differentiation of MLC to M2 macrophages. This is a vicious cycle since M2 cells secrete even more MCP-1, generating a positive feedback loop. The result of MTZ regimen administration is the reduced GAM recruitment due to inhibition of chemotaxis [46].

PLX7486 is a selective tyrosine kinase TRKA/B/C CSF-1/CCL2 inhibitor, treating tumors with infiltrating macrophages (Fms), invasion of surrounding nerves and severe pain. Several others inhibitors of TRKA/B/C include Entrectinib (RXDX-101/NMS-E628), Larotrectinib (LOXO-101), and Repotrectinib (TPX-0005) [47].

Recently, several cellular targeting approaches that reduce both MDSCs and GAM numbers have exhibited beneficial effects in glioblastoma GL261 mouse models and need to be further tested in clinical settings. They mainly involve the knock-down of galectin-1, anti-CCR2, IL-12, or anti-FGL2 administration [48]. Additionally, S100B was shown to be involved in glioma growth by upregulating CCL2 and inducing TAM chemoattraction, further indicating a promising role of S100B inhibitors in glioma therapy [49, 50].

Moreover, the combination of monoclonal antibodies blocking CCL2 and standard TMZ-based chemotherapy has been proposed for gliomas treatment, since the administration of anti-CCL2 mAb as monotherapy or its inclusion in glioma vaccines was shown to modestly prolong survival [51].

3.4. Targeting of Toll-like Receptors (TLR)

Macrophages, among other cell types, express on their plasma membranes Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs) that recognize damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) as well as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), further presenting an anti-tumor profile.

Treatment with the MEK kinase inhibitor trametinib reduced significantly the production of TNF-α by microglia and macrophages in response to HSV treatment and also improved the survival of glioma murine models [52]. GL261 cells secreted factors, which reduced microglial AQP1 expression via the MEK/ERK pathway, resulting in increased cell migratory activity and reduced TLR4-dependent innate immune response [53]. The Class A scavenger family member, Macrophage receptor with collagenous structure (MARCO), has been shown to bind to various ligands, such as crystalline silica, oxidized LDL, bacterial lipopolysaccharides and nucleic acids, which are also recognized by TLRs, thus being implicated in the inflammatory response. Moreover, TAMs with M2-like phenotypes express MARCO on their surface. Therefore, anti-MARCO mAbs administration was shown to inhibit cancer growth and metastasis via TAM polarization to M1-like phenotype [54].

Additional immunotherapeutic approaches involve activation of microglia by IL-12, enhancing their phagocytic functions and the secretion of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL). The TLR3 agonist poly(I: C) has also been shown to induce glioma-associated macrophages cell death and inhibit tumor growth and invasion. Moreover, a recombinant immunotoxin to folate receptor β (FRβ) expressed by microglia/macrophages has been demonstrated to deplete them and further reduce tumor growth.

The glycoprotein tenascin C (TNC) has been shown to activate toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) endogenously and was demonstrated to promote inflammatory response by stimulating several pro-inflammatory factors expressed by innate immune cells, such as microglia and macrophages. It induced TAM reprogramming to M1-like phenotype and immunosuppression of T cells, presenting a significant biomarker for glioma progression regarding invasion, angiogenesis and morphological changes in TAMs. TNC antibodies may therefore represent an effective treatment either alone or combined with other drugs [55].

Paclitaxel (taxol) acts in a TLR4-dependent manner, re-educating M2-like macrophages to M1-like TAMs [56].

IMO-2055 is a TLR9 ligand with a structure of phosphorothioate sequence containing two CpG ODN, synthetic immunostimulatory motifs, and two 5′ ends, conferring increased metabolic stability of CpG type B in refractory solid tumors. A clinical trial of IMO-2055 administration to advanced metastatic NSCLC patients demonstrated good tolerability and possible anti-tumoral activity when used in combination with bevacizumab and erlotinib [57].

3.5. Targeting of CXCL12/CXCR4 Signaling Axis

The signaling axis of CXCR4/CXCL12 is implicated in the recruitment of monocytes/macrophages to tumor location, but also to tumor invasiveness and growth. The agents that fall in this category include Plerixafor (AMD3100), Peptide R and USL311 [11, 58, 59].

Plerixafor functions as a CXCR4 antagonist blocking the infiltration of Tie-2+ monocytes, and inducing the reduction of GAM recruitment via inhibition of chemotaxis. The Peptide R is a CXCR4 antagonist, which can induce M1-like polarization [11, 58] while USL311, another CXCR4 antagonist, exhibits anti-cancer activity by preventing the binding of SDF-1 or CXCL12 to CXCR4 [59].

3.6. Targeting of CD47

CD47 is a transmembrane glycoprotein of the immunoglobulin superfamily, expressed on both healthy and cancer cells, which binds to the signal-regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα). It functions as a “don’t eat me” signal to immune system macrophages in some cancer types where it is usually overexpressed [60].

The anti-CD47 humanized antibody targets SIRP α, which recognizes the CD47 ligand on tumor cells, enhancing immune evasion. It has been demonstrated that microglia can effectively phagocytose tumor cells, reducing their inflammatory status [59, 61, 62].

Ιonizing radiation can modulate macrophages towards a M1-like phenotype maintaining their pro-tumorigenic profile. Sublethal radiation exposure in vitro and in vivo was shown to reduce CD47 expression in tumor cells, increasing phagocytosis and IFN-γ production [63].

Hu5F9-G4, an anticancer agent targeting CD47 in GBM, has been reported to block the anti-phagocytic signal to macrophages and initiate immune response [64].

3.7. Targeting of CD40

CD40, a tumor necrotic factor (TNF) receptor family member, is expressed on macrophages among other cell types as well as in some tumors.

Gemcitabine is a nucleoside, used for GBM treatment either alone or combined with other chemotherapeutic agents. It can cross the blood tumor barrier and has several functions, including reprogramming of M1-like macrophages via upregulation of the expression of HLA-DR, CD40, CCR7, and downregulation of the expression of CD163 and CD206 of M2-like macrophages. Thus, it can induce anti-tumor immunity and tumor regression, but may present some drawbacks in the field of chemoresistance, short half-life, and side effects [45, 65].

3.8. Targeting of STAT3

The transcription factor Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) is closely related to cancer cell proliferation and tumor progression. Two molecules that can target STAT3 are Corosolic acid and WP1066.

Corosolic acid was shown to reduce CD163 and IL-10 secretion produced from M2 TAMs, thus suppressing M2 polarization. Additionally, it was shown to inhibit the proliferation of GBM cell lines, U373 and T98G, along with STAT3 and nuclear factor‐kappa B (NF‐κB) activation in macrophages and GBM cells [66].

WP1066 is another STAT3 inhibitor shown to induce the M1-like polarization through STAT3 blocking [67].

3.9. Targeting of MERTK

The MER receptor tyrosine kinase (MERTK) is expressed in GBM along with its ligand GAS6, promoting tumorigenesis, therapy resistance, and decreasing survival. The relevant agents targeting MERTK include UNC2025, PROS1, BGB324, tamoxifen, and BEZ235.

UNC2025 is a novel MERTK inhibitor, which can induce high-rate apoptosis in GBM cell lines and senescence in those that do not respond to apoptosis [68, 69].

PROS1 has been proposed as a novel candidate for GBM therapy and, upon gene silencing, was shown to reduce cell proliferation, inhibit LN18 cell migration, and decrease GBM invasion. It was shown to significantly induce apoptosis while decreasing the levels of Tyro-3, Axl, and MERTK [70].

Upregulation of the Tyro-3, Axl, and Mer was observed in mesenchymal GBM and showed that blockade of AXL triggered apoptosis. It has been reported that BGB324, an AXL blocker, prolonged the survival of immunosuppressed mice [71].

Tamoxifen therapy in C6 glioma cells decreased the activation of AKT and JNK but sustained ERK activation. This treatment resulted in TAM-induced apoptosis [72] via reduction of the expression of survivin and elevation of caspase-3 as well as cell cycle arrest at the S-phase. Despite the therapeutic effect of Tamoxifen, resistance has been detected in certain types of GBM. TAM resistance may involve estrogen receptor‐alpha 66 (ER-α36) activity which negatively regulates TAM-induced inhibition of GBM growth, presumably through regulation of autophagy since ER‐α36 expression is consistent with the levels of autophagy protein P62 [73, 74].

Another method of tamoxifen transfer is combined with wheat germ agglutinin by topotecan liposomes, which reported higher efficiency in drug transport across the blood-brain barrier and survival [75].

Finally, gene silencing via siRNA of latrophilin, seven transmembrane domain-containing protein 1 (ELTD1) and epidermal growth factor, was demonstrated to induce GBM cytotoxicity. A high percent of cytotoxicity was detected in a GBM cell line after administration of a dual inhibitor of PI3K/mTOR pathway, BEZ235 [76].

3.10. Targeting of HSP70

The 70-kilodalton Heat Shock Protein (HSP70) is responsible for protein folding and chaperoning. HSP70 can activate SR-A1, which is a class A1 scavenger receptor, upregulated in many solid tumors, including gliomas, inducing M2-like polarization to M1-like TAMs [77].

4. DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEMS TO TAM

Drug delivery systems play an important role in drug pharmacokinetics, facilitating their passage across the blood-brain barrier, their cellular uptake and thus, enhancing their therapeutic potential. They function as a ‘trojan horse’ containing a well-studied drug and transporting it to the target site, minimizing the side effects of conventional drug transport. Some of the most effective drug delivery systems regarding TAM function include mannosylated liposomes, disulfiram/copper codelivery system (CDX-LIPO) and liposomal honokiol, lipoprotein nRGD, Rg3-based liposomal system, and nanoparticles.

4.1. Mannosylated Liposomes

Several liposome formulations targeting TAMs have been developed which can activate specific cell surface receptors in order to re-educate or deplete TAMs. Among them, mannosylated liposomes bind to mannose receptor-mediated TAMs, presenting high cellular internalization in vitro as well as penetration of tumor spheroids. They exert their effects by promoting the CD86/CD206 ratio leading to reprogramming of M0 and M2 TAM to M1-like phenotype and inhibiting the growth of G422 glioma [78]. Chlorogenic acid (CHA)-encapsulated mannosylated liposomes can also effectively target TAMs and induce polarization of M2 to M1 phenotype, thus inhibiting the growth of G422 glioma tumors, with negligible toxicity [79]. CHA was also demonstrated to elevate the numbers of CD11c-positive M1 and decrease CD206-positive M2 macrophages in tumor tissues [80].

4.2. Disulfiram/Copper Codelivery System (CDX-LIPO) and Liposomal Honokiol

A co-delivery system of disulfiram/copper (CDX-LIPO) and liposomal honokiol has been developed for brain-targeted therapy, which acts through the regulation of the mTOR pathway, inducing reprogramming of tumor metabolism and of tumor immune microenvironment (TIME). CDX-LIPO was shown to induce autophagy of tumor cells and immunogenic cell death by activating TAMs and dendritic cells, while priming T and NK cells, leading to antitumor immunity and regression. It was also shown that CDX-LIPO enhanced polarization of M1-macrophage and induced glucose metabolism in gliomas through mTOR pathway activation [81].

4.3. LBT-OCT Liposomes (LPs)-nRGD

A multi-target lipoprotein nRGD (LPs-nRGD) carrying lycobetaine (LBT) and octreotide was developed to cross BBB, penetrate the tumor and target TAMs, exhibiting anti-glioma efficacy. LBT killed glioma cells and octreotide (OCT) inhibited vasculogenic mimicry (VM) channels while preventing angiogenesis. The LBT-OCT liposomes (LPs) delivery system was proven efficient and prolonged survival time [82].

4.4. Paclitaxel Delivered by Rg3-LPs

The ginsenoside Rg3-based liposomal system (Rg3-LPs) has shown promising multifunctional results in cellular uptake, glioma targeting and penetration of glioma spheroids, as well as intratumoral diffusion from cholesterol liposomes (C-LPs). The Paclitaxel-loaded Rg3-LPs (Rg-PTX-LPs) demonstrated anti-proliferation effects on glioma C6 cells and reprogrammed M2- to M1-TAMs, thus increasing the M1/M2 ratio. They also prolonged survival, expanded the CD8+ T cell population and decreased Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, facilitating T cell immune response [83].

4.5. Nanoparticles

Paclitaxel (PTX)-delivered nanoparticles containing PTX inside the nanoparticle-containing lipid monolayer, a rabies virus glycoprotein RVG peptide, and a biodegradable polymer core, allow crossing of BBB. The RVG-PTX-NPs were shown to induce TAM polarization, preventing tumor progression on a glioma mice model, indicating an effective delivery system for targeting brain TAMs [84].

Macrophages have been demonstrated to deliver nanoparticles, including gold–silica nanoshells, to several tumors, including GBM, surpassing the problem of nanoshells passage through the BBB. The nanoshell-mediated photothermal therapy (PTT) has been proven effective in human glioma spheroids in vitro. A study employing two-photon micrographs of PTT-treated spheroids, composed of nanoshell-loaded macrophages and human glioma cells showed increased cell death upon near-infrared (NIR) laser light exposure, attenuating or totally inhibiting spheroid growth [85].

Additionally, a nano-drug called Nano-DOX, which is composed of nanodiamonds bearing doxorubicin, has been demonstrated to penetrate three-dimensional glioma spheroids in mice xenografts, inducing drug release. The nano-DOX-damaged GBM cells were shown to be an attracting pole for TAMs and Nano-DOX-loaded TAMs, inducing TAM reprogramming to an anti-GBM phenotype, and suppressing glioma growth [86].

Moreover, uPA-activated cell-penetrating peptide (ACPP) conjugated nanoparticles can be directed to several cell types in glioma tissues, indicating a new glioma targeted, increasing survival time. Uptake of nanoparticles (NP) modified with ACPP peptide (ANP) or CPP peptide (CNP) by C6 cells was significantly elevated in vitro compared to traditional nanoparticles in cells and spheroid models of gliomas, exhibiting higher cytotoxicity and inhibitory effects on growth than Taxol and NP-PTX upon PTX loading [87].

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are novel drug and gene delivery nanovectors in biological systems and were shown to be predominantly internalized by macrophages in the GL261 glioma mouse model. Particularly tumor-infiltrating macrophages (CD45high/CD11b/chigh) could phagocytose CNTs more efficiently than other cell types, highlighting their potential use as non-toxic vehicles for targeting macrophages in gliomas [88].

5. MicroRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) present noncoding molecules which can regulate post-transcriptional gene expression, affecting proliferation and apoptosis of tumor cells by acting as oncogenes or tumor-suppressor genes. Downregulation of miR-142-3p is involved in the pathology of gliomas, and particularly in the activity of GBM-infiltrating macrophages through interaction with the TGF-β pathway. Its overexpression was shown to induce M2 cell apoptosis and inhibit glioma-infiltrating macrophages [89]. Additionally, miR-1246 mediated M2 polarization induced by hypoxic-glioma-derived exosomes (H-GDE) through activation of STAT3 and inhibition of NF-κB signaling pathway, contributing to antitumor immunotherapy [90]. Moreover, the glycolytic inhibitor, 3-bromopyruvate (3-BrPA), was demonstrated to inhibit the proliferation of macrophages and dendritic cells through miR-449a targeting by suppressing the Monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) [91]. miR-106b-5p [92] and up-regulated miR-663a reduced M2 macrophage polarization of glioblastoma indicated novel GBM targets [93]. Additionally, miR-608 [94], exosomal miR-15a and miR-92a of M2 macrophages [95], miR-340-5p [96] and miR-142-3p have been shown to decrease tumor burden, inhibit tumor growth, presenting novel therapeutic targets for malignant gliomas [97].

6. OTHER TAM TARGETING OPTIONS

Several experimental compounds and therapeutic approaches that can target TAMs are also currently under investigation in preclinical and clinical testing and may potentially serve as future treating options for gliomas. In this section, we provide an overview of the diverse experimental agents that may be used to target TAMs in gliomas, most possibly along with current conventional treatment.

The monoclonal antibody mAb9.2.27 has been shown to reverse tumor progression of patient-derived TAM ex vivo. Treatment with both NK and mAb9.2.27 was shown to reduce proliferation and tumor growth, increase apoptosis and improve survival compared to controls [98].

Spontaneous necrosis observed in gliomas is a major contributor to poor prognosis and GSC recurrence. It is associated with morphological changes, characteristic of autoschizis-like cell death, termed ‘autoschizis-like products’ (ALPs). ALPs have been shown to be engulfed by macrophages and induce the expression of IL-12, which exhibits anti-neoplastic properties [99].

The inhibition of Na/H exchanger isoform 1 (NHE1) has been shown to stimulate the immunogenicity of glioma tumors and improve the effectiveness of TMZ with anti-PD-1 combination therapy. An increased expression of NHE1 mRNA has been observed in gliomas, which is further stimulated by TMZ. Administration of both TMZ and NHE1 inhibitors resulted in tumor regression in mice, and further anti-PD-1 administration was shown to improve survival [100].

A plasma membrane protein, Caveolin-1 (CAV1), which is overexpressed in GBM, exhibits pleiotropic functions, including the upregulation of monocytes. siRNA inhibition of CAV1 was shown to restore myeloid cell function, as confirmed by TNF-α secretion and present a future target [101].

The inhibitor of proprotein convertases (PC) was shown to act as anti-glioma and as anti-TAM reactivation agent since it was shown to induce the release of anti-neoplastic factors by macrophages, reduce C6 glioma cell proliferation and the expression of microenvironmental-related proteins as well as reactivate macrophages. Its administration led to greater tumor regression compared to standard TMZ therapy, and was revealed as a novel approach for glioma therapy in combination with chemotherapy [102].

Microglia express GABAB receptors in addition to several different functional AMPAR subunits. It has been shown that glutamate-induced directed microglial chemotaxis in an AMPAR-dependent manner. By attracting microglia to the edge of the tumor, microglia can be subverted to the release of ligands that encourage glioma invasion and stemness [103].

The human endogenous retrovirus-H long terminal repeat-associating protein 2 (HHLA2) acts as an immune stimulator, inhibiting the formation of TAMs. Upregulation of HHLA2 has been significantly correlated with a favorable outcome [104].

Tenascin-C (TNC), a peptide which is highly expressed in the TME, has been demonstrated to exert a role in tumor progression due to the up-regulation β1-integrin, which could be inactivated, restraining tumor growth by the Fibronectin-Derived Integrin-Inactivating Peptide (FNIII14) [105].

Integrins can also be effectively targeted for glioma regression. Particularly, the inhibition of alpha5 beta1 (α5β1) integrin, which normally enhances tumor growth through interaction with microglia, has been demonstrated to be a potent down-regulator of tumor progression [106].

Minocycline hydrochloride, a lipophilic antibiotic that is orally administered, has been shown to pass the blood-brain barrier. It has been demonstrated to attenuate the pro-tumorigenic effect of GAMs by blocking p38 MAP kinase, which normally induces the activation of MT1-MMP in microglia. Furthermore, systemic administration of cyclosporine A (CsA) was demonstrated to exert anti-tumor effects such as tumor regression and induction of cell death. Propentofylline (PPF) has also been shown to target the expression of MMP-9 in microglia and, therefore, restrain tumor growth [107].

Gene transfer of Cationic liposome‐mediated interferon‐beta (IFN‐β) is considered to attenuate tumor progression, through its interaction with infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes and macrophages [108].

Finally, administration of ARRY-382 (CSF1r/c-Fms inhibitor) [109], CC-90002 (CD47 inhibitor) [110], TTI-621 (CD47 inhibitor) [111], CP-870,893 (CD40 inhibitor) [112] and RO7009789 (CD40) inhibitor [113] have shown positive effects in advanced solid tumors and are currently under investigation in glioma clinical trials.

CONCLUSION - FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Taken altogether, it is evident that TAMs present a very challenging target for combatting gliomas progression and invasive potential, regulating key tumor properties including proliferation, angiogenesis, and invasion.

A compilation of experimental studies has pointed out that current targeting options for TAMs involve inhibitors and antibodies of chemokine signaling axes (CCR2/CCL2, CXCR4/CXCL12), immunomodulatory molecules (CSF-1R, TLR), anti-angiogenic factors, blockers of surface immunoglobulins (CD47, CD40) and heat shock proteins (HSP70), inhibitors of transcription factors (STAT3) and microRNAs (miRNAs) that can be administered or targeted either as standalone or in combination with other conventional therapies to improve patients’ outcome.

However, constant research efforts have also detected several other experimental compounds, antibodies, receptors and delivery systems that may be employed to diminish the activity of pro-tumorigenic macrophages by either eliminating or re-educating them to obtain an anti-tumorigenic phenotype. Nanocarriers encoding M1-polarizing transcription factors have been demonstrated to reprogram M2- to M1-like TAMs, exerting anti-tumor activity and tumor regressive action [114, 115]. Recently, an epigenetic approach employing histone acetyltransferase inhibitors (HATi), histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (DNMTi) was demonstrated to target M2 TAMs by inhibiting their polarization or decreasing TAM infiltrates [9]. Additionally, the glioma-myeloid cells crosstalk represents a target for therapeutic interference [116]. In order to improve the efficacy of these novel therapeutic strategies, a profound understanding of the interactions between immune cells, TAM, and cancer cells, inside the TME is required to avoid blocking other vital functions while maximizing the benefit of the patient. The evolution of TAM-targeted therapy is expected to unravel novel methods and agents in the near future for treating cancer patients as well as improve the efficacy of existing treatment options.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weller M., Wick W., Aldape K., Brada M., Berger M., Pfister S.M., Nishikawa R., Rosenthal M., Wen P.Y., Stupp R., Reifenberger G. Glioma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2015;1(1):15017. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostrom Q.T., Bauchet L., Davis F.G., Deltour I., Fisher J.L., Langer C.E., Pekmezci M., Schwartzbaum J.A., Turner M.C., Walsh K.M., Wrensch M.R., Barnholtz-Sloan J.S. The epidemiology of glioma in adults: a “state of the science” review. Neuro-oncol. 2014;16(7):896–913. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu K., Lin K., Li X., Yuan X., Xu P., Ni P., Xu D. Redefining tumor-associated macrophage subpopulations and functions in the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1731. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roesch S., Rapp C., Dettling S., Herold-Mende C. When immune cells turn bad-tumor-associated microglia/macrophages in Glioma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19(2):436. doi: 10.3390/ijms19020436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hambardzumyan D., Gutmann D.H., Kettenmann H. The role of microglia and macrophages in glioma maintenance and progression. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19(1):20–27. doi: 10.1038/nn.4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gargini R., Segura-Collar B., Sánchez-Gómez P. Cellular plasticity and tumor microenvironment in gliomas: the struggle to hit a moving target. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(6):1622. doi: 10.3390/cancers12061622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassetta L., Pollard J.W. Targeting macrophages: therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018;17(12):887–904. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petty A.J., Yang Y. Tumor-associated macrophages: implications in cancer immunotherapy. Immunotherapy. 2017;9(3):289–302. doi: 10.2217/imt-2016-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Groot A.E., Pienta K.J. Epigenetic control of macrophage polarization: implications for targeting tumor-associated macrophages. Oncotarget. 2018;9(29):20908–20927. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen S.R., Schmid M.C. Macrophages as key drivers of cancer progression and metastasis. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:9624760. doi: 10.1155/2017/9624760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gieryng A., Pszczolkowska D., Walentynowicz K.A., Rajan W.D., Kaminska B. Immune microenvironment of gliomas. Lab. Invest. 2017;97(5):498–518. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2017.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang S-C., Yu C-F., Hong J-H., Tsai C-S., Chiang C-S. Radiation therapy-induced tumor invasiveness is associated with SDF-1-regulated macrophage mobilization and vasculogenesis. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e69182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu C., Kros J.M., Cheng C., Mustafa D. The contribution of tumor-associated macrophages in glioma neo-angiogenesis and implications for anti-angiogenic strategies. Neuro-oncol. 2017;19(11):1435–1446. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stafford J.H., Hirai T., Deng L., Chernikova S.B., Urata K., West B.L., Brown J.M. Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibition delays recurrence of glioblastoma after radiation by altering myeloid cell recruitment and polarization. Neuro-oncol. 2016;18(6):797–806. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan D., Kowal J., Akkari L., Schuhmacher A.J., Huse J.T., West B.L., Joyce J.A. Inhibition of colony stimulating factor-1 receptor abrogates microenvironment-mediated therapeutic resistance in gliomas. Oncogene. 2017;36(43):6049–6058. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coniglio S.J., Eugenin E., Dobrenis K., Stanley E.R., West B.L., Symons M.H., Segall J.E. Microglial stimulation of glioblastoma invasion involves epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF-1R) signaling. Mol. Med. 2012;18(3):519–527. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elmore M.R.P., Najafi A.R., Koike M.A., Dagher N.N., Spangenberg E.E., Rice R.A., Kitazawa M., Matusow B., Nguyen H., West B.L., Green K.N. Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor signaling is necessary for microglia viability, unmasking a microglia progenitor cell in the adult brain. Neuron. 2014;82(2):380–397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butowski N., Colman H., De Groot J.F., Omuro A.M., Nayak L., Wen P.Y., Cloughesy T.F., Marimuthu A., Haidar S., Perry A., Huse J., Phillips J., West B.L., Nolop K.B., Hsu H.H., Ligon K.L., Molinaro A.M., Prados M. Orally administered colony stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibitor PLX3397 in recurrent glioblastoma: an Ivy Foundation Early Phase Clinical Trials Consortium phase II study. Neuro-oncol. 2016;18(4):557–564. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akkari L., Bowman R.L., Tessier J., Klemm F., Handgraaf S.M., de Groot M., Quail D.F., Tillard L., Gadiot J., Huse J.T., Brandsma D., Westerga J., Watts C., Joyce J.A. Dynamic changes in glioma macrophage populations after radiotherapy reveal CSF-1R inhibition as a strategy to overcome resistance. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020;12(552):eaaw7843. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw7843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dowlati A., Harvey R.D., Carvajal R.D., Hamid O., Klempner S.J., Kauh J.S.W., Peterson D.A., Yu D., Chapman S.C., Szpurka A.M., Carlsen M., Quinlan T., Wesolowski R. LY3022855, an anti-colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors refractory to standard therapy: phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Invest. New Drugs. 2021;39(4):1057–1071. doi: 10.1007/s10637-021-01084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Study of Cabiralizumab in Combination With Nivolumab in Patients With Selected Advanced Cancers - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/ NCT02526017.

- 22.Pradel L.P., Ooi C-H., Romagnoli S., Cannarile M.A., Sade H., Rüttinger D., Ries C.H. Macrophage susceptibility to emactuzumab (RG7155) treatment. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2016;15(12):3077–3086. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pyonteck S.M., Akkari L., Schuhmacher A.J., Bowman R.L., Sevenich L., Quail D.F., Olson O.C., Quick M.L., Huse J.T., Teijeiro V., Setty M., Leslie C.S., Oei Y., Pedraza A., Zhang J., Brennan C.W., Sutton J.C., Holland E.C., Daniel D., Joyce J.A. CSF-1R inhibition alters macrophage polarization and blocks glioma progression. Nat. Med. 2013;19(10):1264–1272. doi: 10.1038/nm.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu G., Gao T., Zhang L., Chen X., Pang Q., Wang Y., Wang D., Li J., Liu Q. NKAP alters tumor immune microenvironment and promotes glioma growth via Notch1 signaling. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):291. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1281-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Achyut B.R., Angara K., Jain M., Borin T.F., Rashid M.H., Iskander A.S.M., Ara R., Kolhe R., Howard S., Venugopal N., Rodriguez P.C., Bradford J.W., Arbab A.S. Canonical NFκB signaling in myeloid cells is required for the glioblastoma growth. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):13754. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14079-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melincovici C.S., Boşca A.B., Şuşman S., Mărginean M., Mihu C., Istrate M., Moldovan I.M., Roman A.L., Mihu C.M. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) - key factor in normal and pathological angiogenesis. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2018;59(2):455–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Z., Ross J.L., Hambardzumyan D. Intravital 2-photon imaging reveals distinct morphology and infiltrative properties of glioblastoma-associated macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116(28):14254–14259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1902366116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson T.E., Kirkpatrick N.D., Huang Y., Farrar C.T., Marijt K.A., Kloepper J., Datta M., Amoozgar Z., Seano G., Jung K., Kamoun W.S., Vardam T., Snuderl M., Goveia J., Chatterjee S., Batista A., Muzikansky A., Leow C.C., Xu L., Batchelor T.T., Duda D.G., Fukumura D., Jain R.K. Dual inhibition of Ang-2 and VEGF receptors normalizes tumor vasculature and prolongs survival in glioblastoma by altering macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113(16):4470–4475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525349113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu-Emerson C., Snuderl M., Kirkpatrick N.D., Goveia J., Davidson C., Huang Y., Riedemann L., Taylor J., Ivy P., Duda D.G., Ancukiewicz M., Plotkin S.R., Chi A.S., Gerstner E.R., Eichler A.F., Dietrich J., Stemmer-Rachamimov A.O., Batchelor T.T., Jain R.K. Increase in tumor-associated macrophages after antiangiogenic therapy is associated with poor survival among patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro-oncol. 2013;15(8):1079–1087. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pander J., Heusinkveld M., van der Straaten T., Jordanova E.S., Baak-Pablo R., Gelderblom H., Morreau H., van der Burg S.H., Guchelaar H-J., van Hall T. Activation of tumor-promoting type 2 macrophages by EGFR-targeting antibody cetuximab. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17(17):5668–5673. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rigamonti N., Kadioglu E., Keklikoglou I., Wyser Rmili C., Leow C.C., De Palma M. Role of angiopoietin-2 in adaptive tumor resistance to VEGF signaling blockade. Cell Rep. 2014;8(3):696–706. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamura R., Tanaka T., Ohara K., Miyake K., Morimoto Y., Yamamoto Y., Kanai R., Akasaki Y., Murayama Y., Tamiya T., Yoshida K., Sasaki H. Persistent restoration to the immunosupportive tumor microenvironment in glioblastoma by bevacizumab. Cancer Sci. 2019;110(2):499–508. doi: 10.1111/cas.13889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scholz A., Harter P.N., Cremer S., Yalcin B.H., Gurnik S., Yamaji M., Di Tacchio M., Sommer K., Baumgarten P., Bähr O., Steinbach J.P., Trojan J., Glas M., Herrlinger U., Krex D., Meinhardt M., Weyerbrock A., Timmer M., Goldbrunner R., Deckert M., Braun C., Schittenhelm J., Frueh J.T., Ullrich E., Mittelbronn M., Plate K.H., Reiss Y. Endothelial cell-derived angiopoietin-2 is a therapeutic target in treatment-naive and bevacizumab-resistant glioblastoma. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016;8(1):39–57. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castro B.A., Flanigan P., Jahangiri A., Hoffman D., Chen W., Kuang R., De Lay M., Yagnik G., Wagner J.R., Mascharak S., Sidorov M., Shrivastav S., Kohanbash G., Okada H., Aghi M.K. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor downregulation: a novel mechanism of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Oncogene. 2017;36(26):3749–3759. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seyfried T.N., Flores R., Poff A.M., D’Agostino D.P., Mukherjee P. Metabolic therapy: a new paradigm for managing malignant brain cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015;356(2) 2 Pt A:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perri S.R., Nalbantoglu J., Annabi B., Koty Z., Lejeune L., François M., Di Falco M.R., Béliveau R., Galipeau J. Plasminogen kringle 5-engineered glioma cells block migration of tumor-associated macrophages and suppress tumor vascularization and progression. Cancer Res. 2005;65(18):8359–8365. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Codrici E., Enciu A-M., Popescu I-D., Mihai S., Tanase C. Glioma stem cells and their microenvironments: providers of challenging therapeutic targets. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:5728438. doi: 10.1155/2016/5728438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guadagno E., Presta I., Maisano D., Donato A., Pirrone C.K., Cardillo G., Corrado S.D., Mignogna C., Mancuso T., Donato G., Del Basso De Caro M., Malara N. Role of macrophages in brain tumor growth and progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19(4):1005. doi: 10.3390/ijms19041005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deng L., Stafford J.H., Liu S-C., Chernikova S.B., Merchant M., Recht L., Martin B.J. SDF-1 blockade enhances anti-VEGF therapy of glioblastoma and can be monitored by MRI. Neoplasia. 2017;19(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang C., Li Y., Chen H., Zhang J., Zhang J., Qin T., Duan C., Chen X., Liu Y., Zhou X., Yang J. Inhibition of CYP4A by a novel flavonoid FLA-16 prolongs survival and normalizes tumor vasculature in glioma. Cancer Lett. 2017;402:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang C., Li Y., Chen H., Huang K., Liu X., Qiu M., Liu Y., Yang Y., Yang J. CYP4X1 inhibition by flavonoid CH625 normalizes glioma vasculature through reprogramming TAMs via CB2 and EGFR-STAT3 axis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2018;365(1):72–83. doi: 10.1124/jpet.117.247130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao T., Su Z., Li Y., Zhang X., You Q. Chitinase-3 like-protein-1 function and its role in diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020;5(1):201. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00303-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brana I., Calles A., LoRusso P.M., Yee L.K., Puchalski T.A., Seetharam S., Zhong B., de Boer C.J., Tabernero J., Calvo E. Carlumab, an anti-C-C chemokine ligand 2 monoclonal antibody, in combination with four chemotherapy regimens for the treatment of patients with solid tumors: an open-label, multicenter phase 1b study. Target. Oncol. 2015;10(1):111–123. doi: 10.1007/s11523-014-0320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grégoire H., Roncali L., Rousseau A., Chérel M., Delneste Y., Jeannin P., Hindré F., Garcion E. Targeting tumor associated macrophages to overcome conventional treatment resistance in glioblastoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:368. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwamoto H., Izumi K., Mizokami A. Is the C-C motif ligand 2-C-C chemokine receptor 2 axis a promising target for cancer therapy and diagnosis? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(23):9328. doi: 10.3390/ijms21239328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salacz M.E., Kast R.E., Saki N., Brüning A., Karpel-Massler G., Halatsch M-E. Toward a noncytotoxic glioblastoma therapy: blocking MCP-1 with the MTZ Regimen. OncoTargets Ther. 2016;9:2535–2545. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S100407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y., Long P., Wang Y., Ma W. NTRK fusions and TRK inhibitors: potential targeted therapies for adult glioblastoma. Front. Oncol. 2020;10:593578. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.593578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Won W-J., Deshane J.S., Leavenworth J.W., Oliva C.R., Griguer C.E. Metabolic and functional reprogramming of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and their therapeutic control in glioblastoma. Cell Stress. 2019;3(2):47–65. doi: 10.15698/cst2019.02.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H., Zhang L., Zhang I.Y., Chen X., Da Fonseca A., Wu S., Ren H., Badie S., Sadeghi S., Ouyang M., Warden C.D., Badie B. S100B promotes glioma growth through chemoattraction of myeloid-derived macrophages. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19(14):3764–3775. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao H., Zhang I.Y., Zhang L., Song Y., Liu S., Ren H., Liu H., Zhou H., Su Y., Yang Y., Badie B. S100B suppression alters polarization of infiltrating myeloid-derived cells in gliomas and inhibits tumor growth. Cancer Lett. 2018;439:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu X., Fujita M., Snyder L.A., Okada H. Systemic delivery of neutralizing antibody targeting CCL2 for glioma therapy. J. Neurooncol. 2011;104(1):83–92. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0473-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoo J.Y., Swanner J., Otani Y., Nair M., Park F., Banasavadi-Siddegowda Y., Liu J., Jaime-Ramirez A.C., Hong B., Geng F., Guo D., Bystry D., Phelphs M., Quadri H., Lee T.J., Kaur B. Oncolytic HSV therapy increases trametinib access to brain tumors and sensitizes them in vivo. Neuro-oncology. 2019;21(9):1131–1140. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noz079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu F., Huang Y., Semtner M., Zhao K., Tan Z., Dzaye O., Kettenmann H., Shu K., Lei T. Down-regulation of Aquaporin-1 mediates a microglial phenotype switch affecting glioma growth. Exp. Cell Res. 2020;396(2):112323. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2020.112323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nakamura K., Smyth M.J. Myeloid immunosuppression and immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0306-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yalcin F., Dzaye O., Xia S. Tenascin-C function in glioma: immunomodulation and beyond. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020;1272:149–172. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-48457-6_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wanderley C.W., Colón D.F., Luiz J.P.M., Oliveira F.F., Viacava P.R., Leite C.A., Pereira J.A., Silva C.M., Silva C.R., Silva R.L., Speck-Hernandez C.A., Mota J.M., Alves-Filho J.C., Lima-Junior R.C., Cunha T.M., Cunha F.Q. Paclitaxel reduces tumor growth by reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages to an M1 profile in a TLR4-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2018;78(20):5891–5900. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith D.A., Conkling P., Richards D.A., Nemunaitis J.J., Boyd T.E., Mita A.C., de La Bourdonnaye G., Wages D., Bexon A.S. Antitumor activity and safety of combination therapy with the Toll-like receptor 9 agonist IMO-2055, erlotinib, and bevacizumab in advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer patients who have progressed following chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2014;63(8):787–796. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1547-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mercurio L., Ajmone-Cat M.A., Cecchetti S., Ricci A., Bozzuto G., Molinari A., Manni I., Pollo B., Scala S., Carpinelli G., Minghetti L. Targeting CXCR4 by a selective peptide antagonist modulates tumor microenvironment and microglia reactivity in a human glioblastoma model. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;35(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0326-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pires-Afonso Y., Niclou S.P., Michelucci A. Revealing and harnessing tumour-associated microglia/macrophage heterogeneity in glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(3):689. doi: 10.3390/ijms21030689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Logtenberg M.E.W., Scheeren F.A., Schumacher T.N. The CD47-SIRPα immune checkpoint. Immunity. 2020;52(5):742–752. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hutter G., Theruvath J., Graef C.M., Zhang M., Schoen M.K., Manz E.M., Bennett M.L., Olson A., Azad T.D., Sinha R., Chan C., Assad Kahn S., Gholamin S., Wilson C., Grant G., He J., Weissman I.L., Mitra S.S., Cheshier S.H. Microglia are effector cells of CD47-SIRPα antiphagocytic axis disruption against glioblastoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116(3):997–1006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1721434116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gholamin S., Mitra S.S., Feroze A.H., Liu J., Kahn S.A., Zhang M., Esparza R., Richard C., Ramaswamy V., Remke M., Volkmer A.K., Willingham S., Ponnuswami A., McCarty A., Lovelace P., Storm T.A., Schubert S., Hutter G., Narayanan C., Chu P., Raabe E.H., Harsh G., IV, Taylor M.D., Monje M., Cho Y-J., Majeti R., Volkmer J.P., Fisher P.G., Grant G., Steinberg G.K., Vogel H., Edwards M., Weissman I.L., Cheshier S.H. Disrupting the CD47-SIRPα anti-phagocytic axis by a humanized anti-CD47 antibody is an efficacious treatment for malignant pediatric brain tumors. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9(381):eaaf2968. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ding A.S., Routkevitch D., Jackson C., Lim M. Targeting myeloid cells in combination treatments for glioma and other tumors. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1715. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gholamin S., Youssef O.A., Rafat M., Esparza R., Kahn S., Shahin M., Giaccia A.J., Graves E.E., Weissman I., Mitra S., Cheshier S.H. Irradiation or temozolomide chemotherapy enhances anti-CD47 treatment of glioblastoma. Innate Immun. 2020;26(2):130–137. doi: 10.1177/1753425919876690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bastiancich C., Bastiat G., Lagarce F. Gemcitabine and glioblastoma: challenges and current perspectives. Drug Discov. Today. 2018;23(2):416–423. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fujiwara Y., Komohara Y., Ikeda T., Takeya M. Corosolic acid inhibits glioblastoma cell proliferation by suppressing the activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 and nuclear factor-kappa B in tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(1):206–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Iwamaru A., Szymanski S., Iwado E., Aoki H., Yokoyama T., Fokt I., Hess K., Conrad C., Madden T., Sawaya R., Kondo S., Priebe W., Kondo Y. A novel inhibitor of the STAT3 pathway induces apoptosis in malignant glioma cells both in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 2007;26(17):2435–2444. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sufit A., Lee-Sherick A.B., DeRyckere D., Rupji M., Dwivedi B., Varella-Garcia M., Pierce A.M., Kowalski J., Wang X., Frye S.V., Earp H.S., Keating A.K., Graham D.K. MERTK inhibition induces polyploidy and promotes cell death and cellular senescence in glioblastoma multiforme. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0165107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu J., Frady L.N., Bash R.E., Cohen S.M., Schorzman A.N., Su Y-T., Irvin D.M., Zamboni W.C., Wang X., Frye S.V., Ewend M.G., Sulman E.P., Gilbert M.R., Earp H.S., Miller C.R. MerTK as a therapeutic target in glioblastoma. Neuro-oncol. 2018;20(1):92–102. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Che Mat M.F., Abdul Murad N.A., Ibrahim K., Mohd Mokhtar N., Wan Ngah W.Z., Harun R., Jamal R. Silencing of PROS1 induces apoptosis and inhibits migration and invasion of glioblastoma multiforme cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2016;49(6):2359–2366. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sadahiro H., Kang K-D., Gibson J.T., Minata M., Yu H., Shi J., Chhipa R., Chen Z., Lu S., Simoni Y., Furuta T., Sabit H., Zhang S., Bastola S., Yamaguchi S., Alsheikh H., Komarova S., Wang J., Kim S-H., Hambardzumyan D., Lu X., Newell E.W., DasGupta B., Nakada M., Lee L.J., Nabors B., Norian L.A., Nakano I. Activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase AXL regulates the immune microenvironment in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2018;78(11):3002–3013. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Feng Y., Huang J., Ding Y., Xie F., Shen X. Tamoxifen-induced apoptosis of rat C6 glioma cells via PI3K/Akt, JNK and ERK activation. Oncol. Rep. 2010;24(6):1561–1567. doi: 10.3892/or_00001018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu Y. Huang, L.; Guan, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, Q-Q.; Han, C.; Wang, Y-J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, C.; Liu, J.; Zou, W. ER-α36, a novel variant of ERα is involved in the regulation of Tamoxifen-sensitivity of glioblastoma cells. Steroids. 2016;111:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qu C., Ma J., Zhang Y., Han C., Huang L., Shen L., Li H., Wang X., Liu J., Zou W. Estrogen receptor variant ER-α36 promotes tamoxifen agonist activity in glioblastoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2019;110(1):221–234. doi: 10.1111/cas.13868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Du J., Lu W-L., Ying X., Liu Y., Du P., Tian W., Men Y., Guo J., Zhang Y., Li R-J., Zhou J., Lou J-N., Wang J-C., Zhang X., Zhang Q. Dual-targeting topotecan liposomes modified with tamoxifen and wheat germ agglutinin significantly improve drug transport across the blood-brain barrier and survival of brain tumor-bearing animals. Mol. Pharm. 2009;6(3):905–917. doi: 10.1021/mp800218q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Serban F., Daianu O., Tataranu L.G., Artene S-A., Emami G., Georgescu A.M., Alexandru O., Purcaru S.O., Tache D.E., Danciulescu M.M., Sfredel V., Dricu A. Silencing of epidermal growth factor, latrophilin and seven transmembrane domain-containing protein 1 (ELTD1) via siRNA-induced cell death in glioblastoma. J. Immunoassay Immunochem. 2017;38(1):21–33. doi: 10.1080/15321819.2016.1209217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang H., Zhang W., Sun X., Dang R., Zhou R., Bai H., Ben J., Zhu X., Zhang Y., Yang Q., Xu Y., Chen Q. Class A1 scavenger receptor modulates glioma progression by regulating M2-like tumor-associated macrophage polarization. Oncotarget. 2016;7(31):50099–50116. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ye J., Yang Y., Dong W., Gao Y., Meng Y., Wang H., Li L., Jin J., Ji M., Xia X., Chen X., Jin Y., Liu Y. Drug-free mannosylated liposomes inhibit tumor growth by promoting the polarization of tumor-associated macrophages. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2019;14:3203–3220. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S207589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ye J., Yang Y., Jin J., Ji M., Gao Y., Feng Y., Wang H., Chen X., Liu Y. Targeted delivery of chlorogenic acid by mannosylated liposomes to effectively promote the polarization of TAMs for the treatment of glioblastoma. Bioact. Mater. 2020;5(3):694–708. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xue N., Zhou Q., Ji M., Jin J., Lai F., Chen J., Zhang M., Jia J., Yang H., Zhang J., Li W., Jiang J., Chen X. Chlorogenic acid inhibits glioblastoma growth through repolarizating macrophage from M2 to M1 phenotype. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):39011. doi: 10.1038/srep39011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zheng Z., Zhang J., Jiang J., He Y., Zhang W., Mo X., Kang X., Xu Q., Wang B., Huang Y. Remodeling tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for glioma therapy using multi-targeting liposomal codelivery. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2020;8(2):e000207. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen T., Song X., Gong T., Fu Y., Yang L., Zhang Z., Gong T. nRGD modified lycobetaine and octreotide combination delivery system to overcome multiple barriers and enhance anti-glioma efficacy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2017;156:330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhu Y., Liang J., Gao C., Wang A., Xia J., Hong C., Zhong Z., Zuo Z., Kim J., Ren H., Li S., Wang Q., Zhang F., Wang J. Multifunctional ginsenoside Rg3-based liposomes for glioma targeting therapy. J. Control. Release. 2021;330:641–657. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zou L., Tao Y., Payne G., Do L., Thomas T., Rodriguez J., Dou H. Targeted delivery of nano-PTX to the brain tumor-associated macrophages. Oncotarget. 2017;8(4):6564–6578. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Madsen S.J., Baek S-K., Makkouk A.R., Krasieva T., Hirschberg H. Macrophages as cell-based delivery systems for nanoshells in photothermal therapy. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012;40(2):507–515. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0415-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li T-F., Li K., Wang C., Liu X., Wen Y., Xu Y-H., Zhang Q., Zhao Q-Y., Shao M., Li Y-Z., Han M., Komatsu N., Zhao L., Chen X. Harnessing the cross-talk between tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages with a nano-drug for modulation of glioblastoma immune microenvironment. J. Control. Release. 2017;268:128–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang B., Zhang Y., Liao Z., Jiang T., Zhao J., Tuo Y., She X., Shen S., Chen J., Zhang Q., Jiang X., Hu Y., Pang Z. UPA-sensitive ACPP-conjugated nanoparticles for multi-targeting therapy of brain glioma. Biomaterials. 2015;36:98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.VanHandel M., Alizadeh D., Zhang L., Kateb B., Bronikowski M., Manohara H., Badie B. Selective uptake of multi-walled carbon nanotubes by tumor macrophages in a murine glioma model. J. Neuroimmunol. 2009;208(1-2):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xu S., Wei J., Wang F., Kong L-Y., Ling X-Y., Nduom E., Gabrusiewicz K., Doucette T., Yang Y., Yaghi N.K., Fajt V., Levine J.M., Qiao W., Li X-G., Lang F.F., Rao G., Fuller G.N., Calin G.A., Heimberger A.B. Effect of miR-142-3p on the M2 macrophage and therapeutic efficacy against murine glioblastoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014;106(8):dju162. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]