Abstract

Tetracycline is an antibiotic that has been prescribed for COVID-19 treatment, raising concerns about antibiotic resistance after long-term use. This study reported fluorescent polyvinylpyrrolidone-passivated iron oxide quantum dots (IO QDs) for detecting tetracycline in biological fluids for the first time. The as-prepared IO QDs have an average size of 2.84 nm and exist a good stability under different conditions. The IO QDs’ tetracycline detection performance could be attributed to a combination of static quenching and inner filter effect. The IO QDs displayed high sensitivity and selectivity toward tetracycline and achieved a good linear relationship with the corresponding detection limit being 91.6 nM.

Keywords: Fluorescence sensor, Iron oxide quantum dots, Tetracycline, Turn-off

1. Introduction

The use of antibiotics such as tetracycline (TCy) has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. TCy belongs to a class of broad-spectrum antibiotics that can be used to treat COVID-19 infection because it exhibits anti-inflammatory activities and can chelate zinc from matrix metal-loproteinases (MMPs). Moreover, TCy can inhibit RNA replication [1]. TCy is also widely used to treat both animal and human infections because of its excellent antimicrobial properties, low toxicity, and economical cost [2]. Agricultural overuse of TCy can lead to excessive concentrations of the antibiotics in edible animal products such as milk [3] and meat [4]. When accumulated in the human body, TCy can cause various health problems, including liver damage, gastrointestinal disturbances, teeth yellowing, and allergic reactions [5,6]. TCy administered via oral or intramuscular injection, which can be absorbed completely and excreted in urine about 40–90% of the dose admitted [7]. As a consequence, urine can then spread into groundwater, river, and soil in the wastewater, which cause a serious pollution to the environments [8]. Overtime, low concentration of antibiotic result in the development of bacteria resistance. Therefore, developing strategies for detecting TCy in urine samples is crucial. Various methods such as high-performance liquid chromatography [9], liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry [10], chemiluminescence [11], capillary electrophoresis (CE) [12], the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [13], and colorimetry [14] have been established for TCy detection. However, most of these methods are limited because they involve tedious sample preparation procedures; require the use of expensive or toxic chemicals; and exhibit low accuracy, sensitivity, and selectivity in complex biological fluids. Accordingly, developing a simple, facile, economical, ecofriendly, and accurate method for detecting TCy in biological fluids is imperative.

In recent years, fluorescent quantum dots (QDs) have gained considerable attention because of their chemical and optical properties, including their relatively long-lifetime fluorescence (FL), tunable FL, constrained emission spectra, broad excitation spectra, large volume-to-surface area, and nanoscale size (<10 nm). Moreover, QDs exhibit low toxicity, excellent water solubility, biocompatibility, and photostability. These remarkable properties have thus rendered QDs as emerging fluorescent nanomaterials in environmental [15,16], energy [17], and biosensor applications [18,19]. Specifically, QDs have been widely applied for the detection of a wide range of biomolecules, therapeutic drugs, peptides, and heavy metals [20–22]. Numerous QDs have also been constructed for detecting antibiotics, including TCy [23–28]. For example, Lu’s group reported a top-down method of synthesizing sulfur QDs through an assembly–fission reaction with a quantum yield of 6.3%; the method requires a long synthesis duration (up to 72 h) [25]. Wei’s group prepared silicon QDs using hydrothermal treatment for 12 h and used them to detect TCy through ratiometry executed using an Eu3+ system [27]. Nevertheless, most of these probes require a long synthesis process as well as a long FL response time to TCy. Furthermore, their practical applications are limited, especially in biological liquid samples. As a result, the development of a QD-based fluorometric probe for TCy detection is still imperative.

Iron oxide QDs (IO QDs) were successfully synthesized in 2019 and were applied in catalysis reactions [29]. Since then, researchers have expressed high interest in exploring the potential of IO QDs for other activities or sensing applications [29,30]. IOQDs constitute a new series of nanomaterials with FL properties. However, applications based on their FL properties are rarely reported. Moreover, nanoprobes are designed with emphasis on selectivity and sensitivity aspects, and these aspects are easily affected by interfering species in sample matrices. Consequently, developing a simple, low-toxicity, environmentally friendly, and easy-to-prepare IO QD-based fluorescent probe is a major challenge.

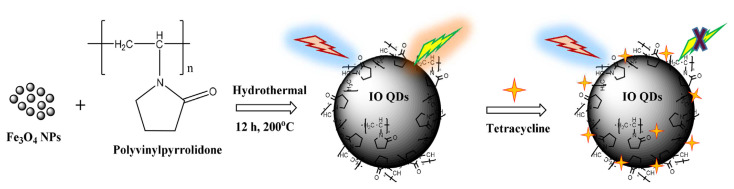

The present study proposed a polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-passivated IO QD probe for detecting TCy in biological fluids, as demonstrated in Scheme 1. The surfaces of the fluorescent IO QDs were determined to be rich in C═O, C–N, –CH2, and pyrrolidone functional groups after capping with PVP. When TCy was introduced, they formed hydrogen bonds with the IO QDs with the corresponding Förster distance about 2 nm and quenching rate constant (Kq) value of 3.4 × 1011 M−1s−1. It’s noted that IO QDs show no remarkable fluorescence lifetime difference in the presence and in the absence of TCy, indicating static quenching. Consequently, the peak FL of the IO QDs (445 nm) was efficiently quenched. The study determined that the inner filter effect (IFE) constituted a mechanism underlying the FL quenching of the probe. Subsequently, the PVP-passivated IO QD probe was successfully applied to detect TCy in urine samples, resulting in high recovery. The as prepared IO QDs show the characteristics of less toxicity, high hydrophilicity, high stability under some environmental condition (light, temperature, salt, long-term storage), and excitation-dependent emission. These results thus demonstrate the potential of IO QDs for real-world applications.

Scheme 1.

The synthetic routes for IO QDs and the principle of TCy probing.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Tetracycline (TCy) and chloramphenicol were purchased from EMD Millipore (Germany). Ampicillin, erythromycin, and kanamycin sulfate were purchased from Bio BasicInc. (USA). Vancomycin was purchased from Calbiochem (USA). Sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim, and hippuric acid were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (Germany). Quinine was obtained from Alfa Aesar (USA). CaCl2.2H2O, ZnCl2, KCl, NaCl, and NH4Cl were purchased from Showa (Japan). Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, molecular weight = 58,000) was obtained from Acros Organics (USA). All reagents were reagent grade and were used without further purification. Ultrapure water prepared using a Milli-Q water system (Simplicity, Millipore) was used to prepare aqueous solutions.

2.2. Instruments

All apparatuses employed to work up the reagents, nanoparticles, and QDs were made of Pyrex glass. FL spectra were measured using an Agilent Cary Eclipse FL spectrophotometer. Ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) absorption spectra were collected using a Shimadzu UV-1800 UV–Vis spectrometer. The pH of the prepared solutions was adjusted using a pH meter (Hotec, model PH-10C). The surface functional groups of the QDs as well as the interaction between QDs and analyte were confirmed using an ALPHA Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectrometer (Bruker). A transmission electron microscope (TEM; Hitachi HT-7700) was employed to examine the surface morphology of the QDs. All hydrothermal reactions were conducted in a Channel precision oven. A vortex mixer (Model VTX-3000L Mixer Uzusio-LMS) was applied to mix the samples. A SQUID0000600 MPMS-XL7 vibrating sample magnetometer system was used to examine the magnetization saturation. A powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) instrument (000705 Bruker 2nd Gen) was applied to analyze the diffraction peak data of the IO QDs.

2.3. Synthesis and the stability evaluation of IO QDs

On the basis of an established method [31], Fe3O4 nanoparticles (IO NPs) were used as the precursor for IO QD synthesis. Specifically, the IO NPs (5 mg/mL; 5 mL) were mixed with PVP (0.25 g; ~0.86 mM) and subjected to a hydrothermal reaction for 12 h at 200 °C. After cooling to room temperature, the solutions were filtered using a 0.22-μm membrane filter and diluted 20-fold before being stored at 4 °C for subsequent experiments. Different radiation wavelengths, temperatures, pH levels, ionic strength levels, and storage times were used to evaluate the FL stability of the prepared IO QDs. The IO QDs were exposed to light-emitting diode light (λ = 254 nm) and UV light (λ = 366 nm) for 0–30 min. The thermal stability of the IO QDs was tested at temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 100 °C. Moreover, the pH stability of the IO QDs was evaluated at pH levels ranging from 3 to 11. The IO QDs were also mixed with NaCl solutions of different concentrations (0–1000 mM) to investigate the effects of the solution concentration on their ionic strength. Finally, the IO QDs were stored in a refrigerator to monitor their long-term storage stability.

2.4. Quantum yield measurement

The absorption spectra of the samples were measured at an excitation wavelength of 340 nm and a small absorbance of <0.1. The FL spectra of the samples were recorded at an excitation of 340 nm over a wavelength range of 350–600 nm. A slit width of 5 nm was used for both the excitation and emission beams. The FL spectra of both quinine sulfate and IO QDs were recorded under the same conditions. Quantum yield was calculated using the absorbance and integrated intensity of the emission spectra, as expressed in the following equation [32]:

| (1) |

where Q denotes the quantum yield, I denotes the integrated intensity of the emission spectra, A denotes the absorbance at the excitation wavelength, n denotes the refractive index, and the subscript r denotes the reference (quinine sulfate) with a 0.54 quantum yield [32].

2.5. Fluorescent IO QDs for TCy examination

The emission spectra of the IO QDs in the presence of various antibiotics were measured at an excitation wavelength of 340 nm. The slit width for both the excitation and emission beams was 5 nm. Different antibiotics were used in the measurement to examine the selectivity of the as-prepared IO QDs at a fixed concentration of 200 μM. The FL intensity (λem = 445 nm) was recorded to determine the particular antibiotics that provided FL quenching effects compared with a blank. The detection limit was calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

where σ represents the standard deviation of the FL emission intensity of the IO QDs and S represents the slope of the calibration curve. The selectivity of the fluorescent IO QDs was evaluated by monitoring changes in the FL emission spectra in the presence of various antibiotics and other compounds commonly found in urine, such as Ca2+, K+, Zn2+, Na+, hippuric acid, and ammonia. The solution was prepared at a concentration of 200 μM in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution.

2.6. Real sample analysis

In this study, human urine samples were collected from a healthy volunteer and tested. The collected urine samples were diluted 10-fold with PBS solution and filtered through a 0.22-μm Millipore membrane filter. The filtrates were collected for further measurement. Subsequently, the IO QD probe (constituting the sensing platform) was tested to assess its practical applicability for detecting TCy by using the standard addition method. For this assessment, TCy was added separately to the urine samples at different concentrations.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of IO QDs

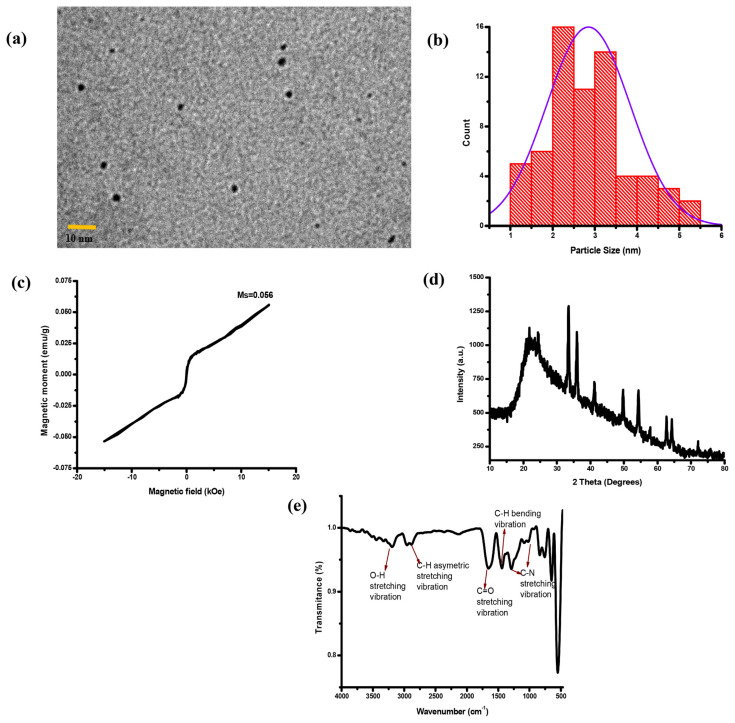

TEM images were used to characterize the morphology and particle size of the IO QDs. The IO QDs exhibited uniform spherical nanoparticles with an average diameter of 2.84 ± 0.99 nm (Fig. 1a–b). Figure 1c illustrates the hysteresis loops of the IO QDs. The magnetization saturation (Ms) of the IO QDs was measured to be 0.052 emu/g, indicating that the magnetic properties of the IO QDs are very low compared with iron oxide nanoparticles. This is attributable to the oxidation of the IO QD surfaces [33]. Figure 1d displays the powder XRD patterns derived for the prepared IO QDs. The diffraction peaks located at 2 Theta = 21.5°, 24.2°, 33.1°, 35.7°, 41.0°, 49.3°, 54.0°, 57.5°, 62.5°, 64.1°, and 72.1° corresponded to the (211), (012), (104), (110), (113), (024), (116), (018), (214), (300), and (002) planes of Fe2O3, respectively [34]. To determine the effects of IO QD passivation by PVP, the FTIR spectra of the IO QDs were measured (Fig. 1e). The spectra revealed a broad band at approximately 3267 cm−1, which was attributed to O–H stretching [35]. Another band was observed at 2805 cm−1 and was ascribed to C–H asymmetric stretching vibration [36]. The spectra for the pure ligand also revealed a strong band at 1630 cm−1, which was attributed to C═O stretching [37]. Moreover, an absorption peak related to C–H bending vibration appeared at 1428 cm−1 [38]. Two additional bands were observed at 1018 and 1291 cm−1 and were ascribed to C–N stretching vibration [39].

Fig. 1.

(a) TEM image of IO QDs. (b) Size distribution graph of IO QDs. (c) hysteresis loop of IO QDs. (d) XRD of IO QDs. (e) FTIR spectrum of the evaluated IO QDs.

3.2. Optimization of synthetic condition

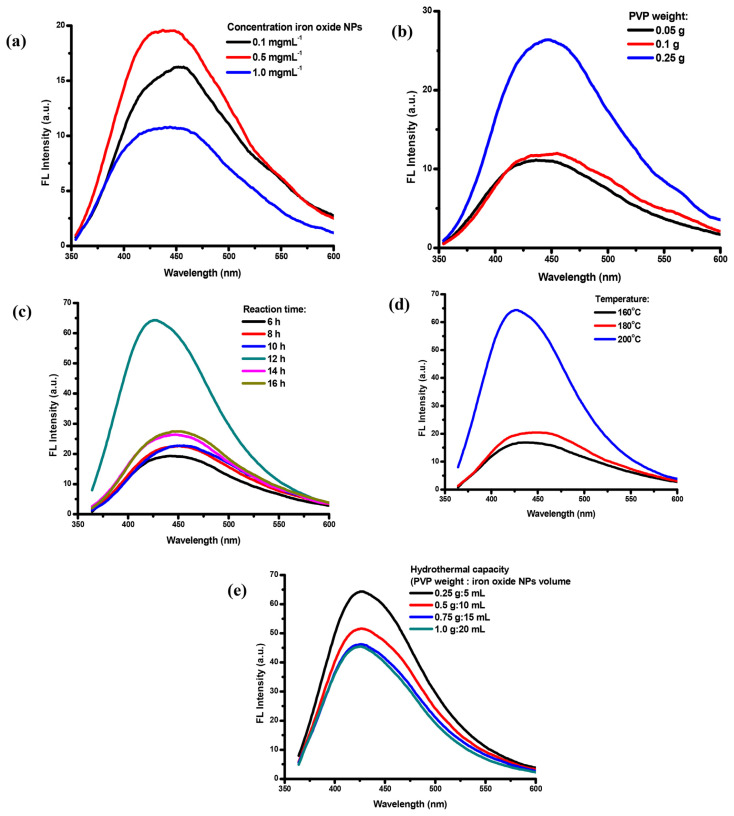

Scheme 1 presents a schematic of the IO QD synthesis procedure. The growth of spherical IO QDs in solution involved two steps. First, monomers (IO NPs and PVP precursors) from the bulk solution were transported onto the QD surface; second, the monomers on the surface reacted [40]. The IO QDs were synthesized through a hydrothermal reaction in which IO NPs served as the precursor. Moreover, PVP served as the capping agent, which was used to passivate and obtain FL properties. To determine the optimal condition for achieving QDs high FL efficiency, various IO NP concentrations, PVP concentrations, hydrothermal reaction times, temperatures, and hydrothermal capacity levels were studied (Fig. 2a–e). The fluorescence intensity increases when the IO NPs at concentration of 0.1 mg/mL to 0.5 mg/mL and declines when the concentration of IO NPs is 1.0 mg/mL. The amount of PVP of 0.25 g results in the highest fluorescence intensity compared to the other amount of PVP at 0.05 g and 0.1 g. The crystal growth process of the IO QDs formation was found to be influenced by the precursor concentration of IO NPs and PVP result in the best fluorescence properties [30]. The reaction time and temperature are also important to gain the optimized fluorescence features. The high fluorescence intensity was achieved at 200 °C with 12 h of hydrothermal reaction time, which is a result of the suppression of nonradiative pathway on IO QDs the surface [41] and adequate crystal growth. The assessment results revealed that the optimal condition for achieving QDs with high FL efficiency was as follows: IO NP concentration, 0.5 mg/mL (5 mL); PVP, 0.25 g; temperature, 200 °C; and hydrothermal reaction time, 12 h. Subsequently, the optimized QDs exhibited a bright blue color under UV light at 365 nm. The prepared QDs could be used as fluorescent sensors for toward TCy through the turn-off process.

Fig. 2.

Synthetic condition of (a) NPs concentration (0.1 g PVP, t=14 h, T=200°C). (b) PVP optimization (IO NPs: 0.5 mg/mL, t: 14 h, T: 200°C). (c) reaction time (IO NPs: 0.5 mg/mL, PVP: 0.25 g, T: 200°C). (d) temperature (IO NPs concentration: 0.5 mg/mL, PVP: 0.25 g, t: 12 h). (e) hydrothermal capacity (t: 12 h, T: 200°C).

3.3. Optical properties of IO QDs

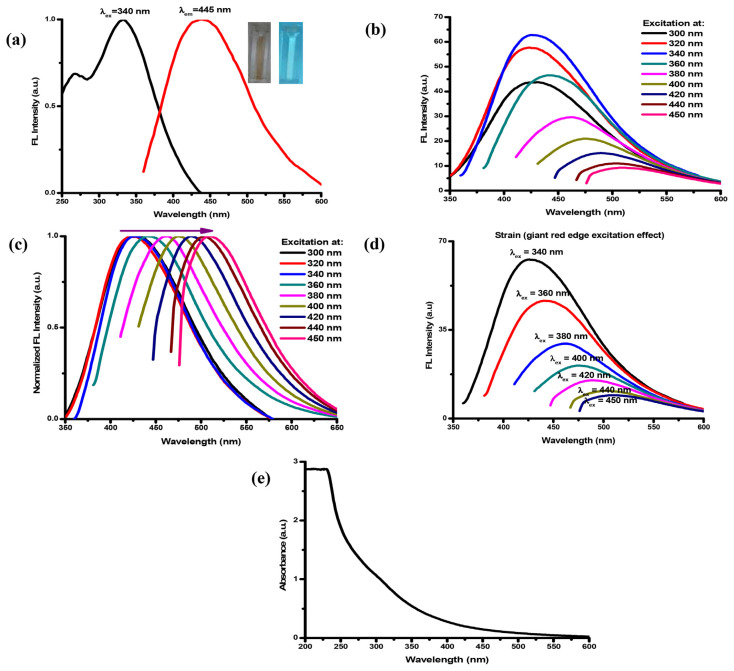

The optical properties of the prepared IO QDs were examined by analyzing their FL and UV–Vis absorption spectra. In general, strong FL emission is among the most beneficial characteristics of IO QDs. Figure 3a illustrates the FL excitation and emission spectra of the IO QDs, revealing the appearance of an optimal peak at excitation and emission wavelengths of 340 and 445 nm, respectively. The IO QDs exhibited excitation-dependent emission (Fig. 3b) because of surface defects caused by surface oxidation and different particle sizes [42–44]. The IO QD spectra also exhibited a redshift (Fig. 3c), which was caused by electronic relaxation after band-edge light absorption. This phenomenon can be attributed to two possible mechanisms: the first mechanism involves loss of energy through shallow trapping of valence band holes to a state where they can combine with delocalized conduction band electrons, and the second mechanism involves a large geometric reorganization of the excited state, resulting in considerable electron–phonon coupling and emission to a vibrational electronic ground state [45]. Moreover, a phenomenon strain (a giant red edge excitation effect) was observed (Fig. 3d) at the highest emission wavelength (λex = 340 nm), and this strain was tuned to a higher wavelength as the excitation wavelength increased [46]. The FL spectra could primarily be attributed to exciton radiative recombination, which can be modulated by the bandgap structure, dark exciton states, chemical treatment, dielectric screening effects, or disorders [47]. Additionally, the FL spectra could be attributed to exciton recombination with different structural defects [48]. These defects could act as efficient trapping centers for electrons, holes, and excitons and exert a strong influence on the electronic and optical properties of a material [49,50]. C═O, C–N, and –CH2 functional groups [51] passivate QD surface defects, resulting in the enhancement of FL intensity [52]. The UV–Vis spectra of the IO QDs is presented in Fig. 3e. An extremely intense absorption band was observed at approximately 240–260 nm, and this is a commonly observed feature in various types of QDs [53–55]. However, studies have determined that this peak did not contribute to the FL of QDs and have attributed it to nonradiative electron transitions and background material [56,57]. In the present study, the spectra of the IO QDs also revealed a peak at approximately 300 nm, which was attributed to the n-π* transition of C═O [58]; they also revealed an optimal emission peak at 445 nm when the excitation wavelength was 340 nm. Using quinine solution in 0.1 M sulfuric acid as a reference, this study calculated the quantum yield of the IO QDs to be 12.37% ± 0.10%. To the best of our knowledge, few IO QDs have been applied as fluorescent sensors, and our method achieved the highest IO QD quantum yield among the reported approaches [29].

Fig. 3.

(a) FL excitation and emission spectra of IO QDs (insets show the IO QDs solution under day light and UV light of 365 nm). (b) the emission spectra under various excitation wavelength. (c) normalized spectra. (d) Strain (giant red edge excitation effect). (e) absorption spectra of IO QDs.

3.4. Stability of IO QDs

For IO QDs, thermal stability is a crucial parameter for operation above room temperature. This study observed that the FL of the prepared IO QDs was quenched due to thermal induction (Fig. S1a). Specifically, the FL decreased as the temperature increased The FL of the dots was quenched by up to 20% at 100 °C, but it recovered to its initial level after the dots were cooled to room temperature. This reversible FL quenching effect could be attributed to the thermally produced temporary trap states, and this effect remained reversible up to a certain temperature. In general, trap states cause FL quenching through trap emission or nonradiative quenching [59]. Higher temperatures can trigger FL quenching because the surface QDs undergo oxidation [60].

This study also executed photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy to explore the photostability of the IO QDs. The results indicated that the PL intensity gradually decreased to less than 10% when the IO QDs were subjected to UV irradiation for 0–30 min (Fig. S1b). The high stability under UV irradiation was caused by the presence of PVP, which served as a stabilizing ligand to prevent the occurrence of an ionized dark state in the IO QDs [61]; PVP also served as a scavenger of reactive oxygen species that were produced by the illumination process [62]. C═ O groups on the surfaces of IO QDs protect the QDs from oxidation by blocking the reactive sites [63]. This study did not observe precipitation upon irradiation, implying that the IO QDs exhibited high photostability with anti-photobleaching features.

This study explored the stability of the IO QDs by mixing them with NaCl solutions of different concentrations (0–1000 mM) and then evaluating the effects of these concentrations on the ionic strength of the IO QDs (Fig. S1c). The NaCl solution concentrations did not induce IO QD aggregation. Subsequently, the IO QDs were mixed with solutions of different pH levels, and the corresponding FL spectra were recorded to evaluate the effects of pH on the FL properties of the IO QDs. The solutions with different pH levels engendered notable changes in the emission intensity of the IO QDs. Therefore, IO QDs are dependent on pH. The study revealed that the FL intensity was highly stable at pH values of 3–7 (Fig. S1d). This property is useful because to the best of our knowledge, few QDs can retain their high PL and FL intensity in water over such a wide pH range. The surfaces of the IO QDs were determined to be rich in carboxyl, hydroxyl, carbonyl, amines, and other functional groups that may undergo protonation and deprotonation [64].

This study also evaluated the effect of storage time on the FL intensity of the IO QDs (Fig. S1e). The results revealed that the surfaces of the IO QDs did not undergo degradation during 30 days of refrigerated storage, indicating that the FL intensity of QDs is highly stable when stored.

3.5. Optimized measurement condition for TCy sensing

This study investigated the effects of pH, response time, and buffer on the FL quenching ratio (F/F0, where F and F0 represent the FL intensity of IO QDs in the presence and absence of TCy, respectively) to determine the optimal condition for TCy detection. Adding 200 μM TCy to IO QD solutions with pH levels ranging from 3 to 11 quenched the FL intensity of the IO QDs (Fig. S2a). Notably, the FL intensity of the IO QDs was independent of pH values ranging between 3 and 11. Therefore, the IO QD probe can be applied for TCy detection over a wide pH range. When the IO QDs were incubated with 200 μM TCy, the F/F0 values decreased rapidly after 2 min of incubation and then remained stable for at least 30 min (Fig. S2b). These findings indicate that TCy can rapidly quench the FL intensity of IO QDs. Accordingly, this study determined the optimal response time to be 2 min. Fig. S2c displays the responses of the IO QDs to TCy in acetate (pH 4, 0.2 M), citrate (pH 3, 0.25 M), and PBS (pH 7, 0.1 M), indicating that buffer type had no effect on FL quenching effects; specifically, the IO QD probe could function independent of buffer type. Hence, for subsequent tests, this study selected PBS (pH = 7.0) under the experimental condition, the pH of which is within biologically relevant pH for real-world sampling applications.

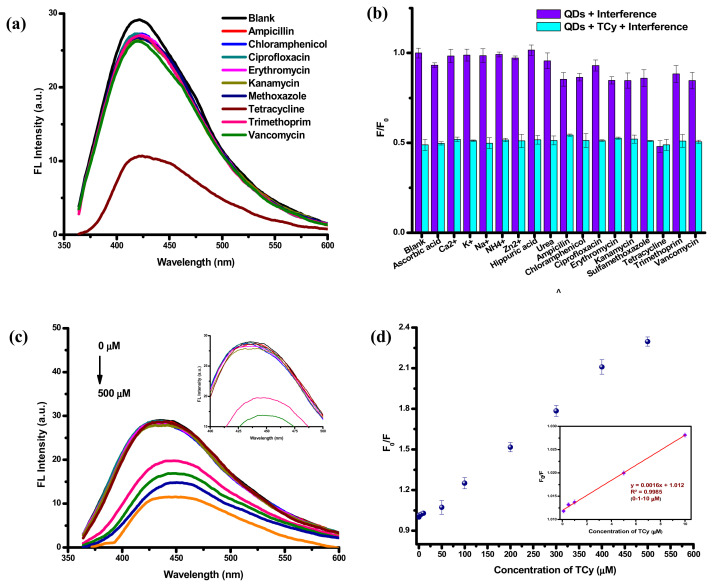

3.6. Selectivity and interference study

To evaluate the selectivity of the IO QDs toward TCy and analyze factors interfering with the detection performance of the IO QDs, this study derived FL quenching ratios (F/F0) for the probe in interfering compounds, including various antibiotics, biomolecules, and metal ions. The results indicated that the FL quenching ratios for the probe remained unchanged or exhibited negligible changes (Fig. 4a–b). Fig. S3a–b illustrates the FL and the color change of the IO QDs upon the addition of TCy and other antibiotics, indicating that the IO QDs exhibited high selectivity toward TCy; this thus demonstrates the considerable feasibility of the IO QD probe for TCy detection. The study also conducted an interference analysis by testing the effects of interfering substances that commonly exist in samples on the detection performance of the IO QDs. The analysis results (Fig. 4b) suggested that the chemical species could not interfere with the TCy detection of the IO QDs. The unique selectivity of the IO QDs towards TCy can be attributed to the hydrogen bonding formation between the hydroxyl, carboxyl and amide groups of TCy and the abundant polar groups on the IO QDs’ surface, result in the fluorescence quenching and dark complex formation.

Fig. 4.

(a) The FL quenching efficiency of IO QDs solution after adding various antibiotics. (b) selectivity and interference test of IO QDs among all tested antibiotics and over other interfering substances at the concentration of 200 μM. (c) fluorescence emission of IO QDs solution in the presence of various TCy concentrations (λex=340 nm, 1 min incubation time) (inset: emission of IO QDs after adding TCy ranged 0–200 μM). (d) plots of relative fluorescence (F0/F) values of IO QDs solution in the presence of various concentrations (inset: plot F0/F towards concentration of TCY in the range 0.1 to 10 μM).

3.7. FL analysis of TCy

Various concentrations of TCy were added to the IO QDs solutions to determine their correlation with FL intensity. The TCy concentration profiles are presented in Fig. 4c–d. As the TCy concentrations increased, the FL intensity levels decreased considerably. The FL emission exhibited a slight redshift from 445 to 450 nm when the TCy concentration increased from 0 to 500 μM. IO QD/TCy systems may engender IO QD surface defects, leading to a nonradiative recombination of the excitons and FL quenching [65]. This interaction may explain the quenching of the FL intensity levels of the IO QDs observed in this study. A linear relationship was observed between F0/F and TCy concentration (0–500 μM), with the corresponding R2 value being 0.9969 (Fig. 4d). The limit of detection (LOD) was calculated to be nearly 91.6 nM. Overall, the advantages of the fluorescent IO QD probe developed in this study include its simple operation, rapid detection and determination, ease of use, low cost, high sensitivity, and high selectivity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of the established method with other reported methods for detection of TCy.

| Probe | Fluorescence signal type | Samples | Response time | Linear range | LOD | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Organic coordination framework | Turn-on | milk | 5 min | 0.2–0.6 μM | 12nM | [24] |

| Silicon nanodots (SiNDs)/Eu3+ system | Ratiometric | water and milk | 1 min | 0.2–20 μM | 3 nM | [27] |

| l-cysteine functionalized CdS Quantum dots | Turn-off | Resticline tablet | 5 min | 15–600 μM | 7.78 μM | [23] |

| Sulfur quantum dots | Turn-off | milk | 1 min | 0.1–50 μM | 28nM | [25] |

| inorganic halide perovskite quantum dots (IPQDs) | Turn-off | soil | 15 min | 0.5–15 μM | 76nM | [26] |

| CDs | Ratiometric | water | N/Aa | 0.5–6 μM | 0.33 μM | [28] |

| IO QDs | Turn-off | urine | 2 min | 0.1–10 μM | 91.6 nM | This work |

N/A: Not available.

3.8. TCy sensing performance of IO QDs in real sample

To evaluate the practicality of the fluorescent IO QD probe developed in this study, the prepared IO QDs were employed to detect TCy in urine samples by using the standard addition method. The probe detected TCy in the urine samples, with the recovery rates ranging from 99.384% ± 1.093%– 110.067% ± 2.627% and the relative standard deviation (RSD) ranging from 1.100% to 2.387% (Table 2). The recovery and RSD values demonstrate the relatively high accuracy and reproducibility of the probe in the detection of TCy. These results indicate that the IO QDs can rapidly and accurately screen for TCy in biological liquid samples.

Table 2.

Determination of TCy in real samples using the IO QDs.

| Analytical parameter | Amount found (μM) | Added (μM) | Total found (μM) | Recovery (%) | RSD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-day | 2.60 ± 0.16 | 1 | 3.70 ± 0.03 | 110.07 ± 2.63 | 2.39 |

| 10 | 13.01 ± 0.19 | 104.11 ± 1.88 | 1.80 | ||

| 100 | 101.98 ± 1.10 | 99.38 ± 1.10 | 1.10 | ||

| Inter-day | 0.659 ± 0.079 | 1 | 1.649 ± 0.031 | 99.067 ± 3.121 | 3.151 |

| 10 | 10.453 ± 0.172 | 97.943 ± 1.718 | 1.754 | ||

| 100 | 102.567 ± 0.725 | 101.904 ± 0.725 | 0.711 |

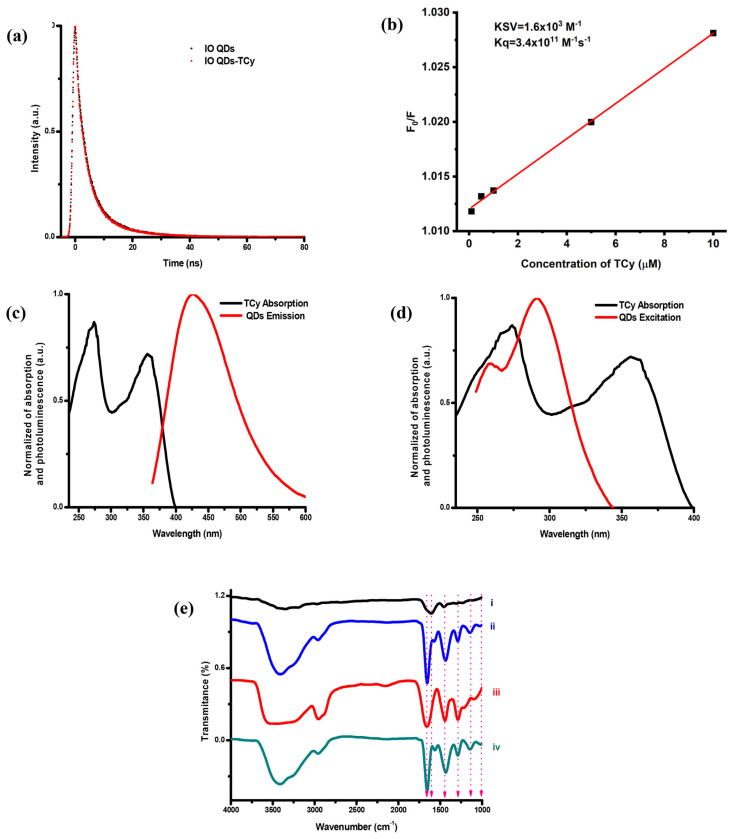

3.9. Mechanisms of FL quenching of IO QD probe

This study executed several additional experiments to determine the FL quenching mechanisms of the IO QDs. First, the FL lifetime of the IO QDs was evaluated, and FL decay curves were plotted for the IO QDs in the absence and presence of TCy (Fig. 5a). The average luminescence lifetimes of the IO QDs in the absence and presence of TCy were 4.69 and 4.62 ns, respectively. The presence of TCy influenced the FL lifetime of the IO QDs, indicating a possible static quenching effect [66]. Additionally, the Stern–Volmer equation was used to verify the presence of static or dynamic quenching processes (Equation (1) in supporting information). The Stern–Volmer plots are displayed in Fig. 5b, the calculation results revealed that the Stern–Volmer quenching constant (KSV) and the quenching rate constant (Kq) was 1.6 × 103 M−1 and 3.4 × 1011 M−1s−1, respectively. Kq was higher than maximum value of the dynamic quenching effect (2.0 × 1010 M−1s−1) [67], indicating the involvement of static quenching. The static quenching effect involved ground state interactions, whereas the dynamic quenching involved either excited-state or collisional interactions of Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET). Two primary conditions must be met for FRET to occur in any donor or acceptor. First, the absorbance of the acceptor (TCy) and the FL emission of the donor (IO QDs) should overlap significantly (Fig. 5c). Second, the Förster distance between the donor and the acceptor must be < 10 nm for an effective FRET, and this distance was calculated to be 2.1 nm in this study (Equation (2) in supporting information) [68]. In FRET, the lifetime of IO QDs should be shortened in the presence of TCy. In this case, FRET did not take responsibility for the quenching mechanism. In fact, Förster distance is about or less than 2 nm indicating the static quenching [69].

Fig. 5.

(a) Luminescence lifetime of IO QDs in the absence and in the presence of 200 μM TCy. (b) Stern-Volmer plot of IO QDs with TCy, (c)spectral overlap in FRET, (d) spectral overlap in IFE. (e) FTIR spectra of IO QDs (i), IO QDs/TCy (ii), TCy (iii), and the subtraction result (iv).

In addition, the IFE between the IO QDs and TCy constituted a mechanism for the FL quenching effect [70,71]. The UV–Vis absorption spectra of TCy and the excitation spectra of the IO QDs (Fig. 5d) overlapped, confirming the existence of the IFE. Meanwhile, the lifetime of IO QDs in the absence and in the presence of TCy is unchanged, which is also a key feature of IFE [72]. The infrared spectra of the IO QD/TCy system were also measured. Figure 5e illustrates the FTIR spectra of the IO QDs, IO QD/TCy system, and the subtraction results. As shown in Fig. 5e, the FTIR spectra of the IO QDs were changed with the addition of 1000 μM TCy at a pH of 7. The interaction of TCy with the IO QD groups mainly led to the shifting of the absorption band located at 1618–1654 cm−1, which can be attributed to C═O stretching vibration in the pyrrolidone group [39,73]. Moreover, for the subtraction results, the spectra revealed a peak at 1661 cm−1, implying the formation of an IO QD/TCy system that engendered band shifts attributed to C═O stretching vibration. The spectra of the IO QDs revealed a peak at 1457 cm−1, which shifted to 1435 cm−1 and increased in intensity after the dots interacted with TCy; this peak was ascribed to C–H bending vibration [39]. Furthermore, two peaks located at 1018 and 1291 cm−1 were noted to shift to 1011 and 1296 cm−1, respectively, and were attributed to C–N stretching vibration [39]. Absorption bands were also observed at 1296 cm−1 and were ascribed to C–N bending vibration from the pyrrolidone structure. The spectra for the subtraction results indicated another band at 1428 cm−1, which was attributed to C–H bending vibration, and two bands at 1027 and 1282 cm−1, which were ascribed to C–N stretching vibration. Hydrogen bonding between the IO QDs and TCy led to the closest Förster distance between these entities, thereby enhancing the energy transfer between them. The Förster distance (about 2 nm) facilitates static FL quenching of IO QDs.

4. Conclusion

This study presents the first successful synthesis of IO QDs with a quantum yield of 12.37% ± 0.10% by using the hydrothermal method with PVP as the passivant. The IO QDs exhibited surface defects caused by abandoned –C═O, C–N, –CH2, and pyridine groups of PVP, and these defects constituted the major luminescence mechanism of the IO QDs. In addition, the IO QDs exhibited rapid response, simple operation, and high sensitivity and selectivity toward TCy. They could also detect TCy in the concentration range of 0.1–10 μM, with the corresponding LOD being 91.6 nM. Moreover, TCy strongly quenched the FL of the IO QDs through static quenching and inner filter effect. The IO QDs were also used as a fluorescent sensor to detect TCy in urine samples, and they achieved remarkable results, demonstrating this probe’s capability for practical applications.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology under grant MOST110-2113-M-037-011 and MOST111-2113-M-037-015.

Appendix

(a) temperature stability of IO QDs. (b) photostability of IO QDs (LED: Light-emitting diode, LW: Long wavelength (λ=365 nm), SW: Short wavelength (λ=265 nm). (c) Ionic strength effects on IO QDs. (d) pH stability of IO QDs. and (e) storage time stability of IO QDs.

Effect of (a) pH value (3–11) of IO QDs and IO QDs/TCy system on FL intensity. (b) time reaction (0–30 min) after adding TCy. (c) various buffers before and after adding TCy on FL quenching ratio (F/F0).

Luminescence of IO QDs in the presence of various antibiotics under (a) daylight and (b) UV light.

A possible mechanism for FRET fluorescence quenching

The type of quenching and the quenching behaviors were investigated by ratio F0/F and the quenching constant KSV as determined by the Stern-Volmer plot following the equation [74].

| (1) |

where F0 is the fluorescence intensity at a specified emission wavelength in the absence of a TCy, F denotes the fluorescence intensity at emission wavelength, and [Q] is TCy concentration. KSV represents the Stern-Volmer quenching constant at emission wavelength, Kq is the quenching rate constant, and τ0 means fluorophore lifetime.

It was found that the Kq was measured to be 3.4*1011 M-1s-1 and it was higher than the maximum value of the dynamic quenching effect (2.0*1010 M-1s-1) [67] by calculation. This result further prove that the static quenching effect dominated the fluorescence quenching. The Förster distance between the donor and the acceptor was calculated to be 2.1 nm (<10 nm for an effective FRET) [68]. Förster distance was calculated using the formula [75]:

| (2) |

where R0 is the Förster distance (in nm), k2 denotes dipole orientation factor (2/3) [76], φD denotes fluorescence quanrum yield of IO QDs, η denotes refractive index of the solvent, and J denotes the overlap integral.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology under grant MOST110-2113-M-037-011 and MOST111-2113-M-037-015.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1. Sodhi M, Etminan M. Therapeutic potential for tetracyclines in the treatment of COVID-19. Pharmacotherapy. 2020;40:487–8. doi: 10.1002/phar.2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schnappinger D, Hillen W. Tetracyclines: antibiotic action, uptake, and resistance mechanisms. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165:359–69. doi: 10.1007/s002030050339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Croubels S, Peteghem CV. Sensitive spectrofluorimetric determination of tetracycline residues in bovine milk. Analyst. 1994;119:2713–6. doi: 10.1039/an9941902713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. De Wasch K, Okerman K, De Brabander H, Van Hoof J, Croubels S, De Backer P. Detection of residues of tetracycline antibiotics in pork and chicken meat: correlation between results of screening and confirmatory tests. Analyst. 1998;123:2737–41. doi: 10.1039/a804909b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perez-Rodriguez M, Pellerano RG, Pezza L, Pezza HR. An overview of the main foodstuff sample preparation technologies for tetracycline residue determination. Talanta. 2018;182:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gokulan K, Cerniglia CE, Thomas C, Pineiro SA, Khare S. Effects of residual levels of tetracycline on the barrier functions of human intestinal epithelial cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2017;109:253–63. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim K-R, Owens G, Kwon S-I, So K-H, Lee D-B, Ok YS. Occurrence and environmental fate of veterinary antibiotics in the terrestrial environment. Water, air & Soil Pollut. 2010;214:163–74. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alnassrallah MN, Alzoman NZ, Almomen A. Qualitative immunoassay for the determination of tetracycline antibiotic residues in milk samples followed by a quantitative improved HPLC-DAD method. Sci Rep. 2022;12:14502. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-18886-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou JX, Xiaofeng L, Yi Z, Jinzhen C, Fang W, Liming C, et al. Multiresidue determination of tetracycline antibiotics in propolis by using HPLC-UV detection with ultrasonicassisted extraction and two-step solid phase extraction. Food Chem. 2009;115:1074–80. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cetinkaya F, Yibar A, Soyutemiz GE, Okutan B, Ozcan A, Karaca MY. Determination of tetracycline residues in chicken meat by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Food Addit Contam Part B Surveill. 2012;5:45–9. doi: 10.1080/19393210.2012.655782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Townshend A, Ruengsitagoon W, Thongpoon C, Liawruangrath S. Flow injection chemiluminescence determination of tetracycline. Anal Chim Acta. 2005;541:103–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moreno-Gonzalez D, Lupion-EnriquezI, Garcia-Campana AM. Trace determination of tetracyclines in water samples by capillaryzone electrophoresis combining off-line and on-line sample preconcentration. Electrophoresis. 2016;37:1212–9. doi: 10.1002/elps.201500440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gong X, Li X, Qing T, Zhang P, Feng B. Amplified colorimetric detection of tetracycline based on an enzyme-linked aptamer assay with multivalent HRP-mimicking DNAzyme. Analyst. 2019;144:1948–54. doi: 10.1039/c8an02284d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yuxiong L, Yinying S, Wenjie L, Jianna Y, Guoxing J, Wen L, et al. Enzyme-free dual-amplification assay for colorimetric detection of tetracycline based on Mg(2+)-dependent DNAzyme assisted catalytic hairpin assembly. Talanta. 2022;241:123214. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2022.123214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pedrero M, Campuzano S, Pingarron JM. Quantum dots as components of electrochemical sensing platforms for the detection of environmental and food pollutants: a review. J AOAC Int. 2017;100:950–61. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.17-0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang Y, Xiao JY, Zhu Y, Tian LJ, Wang WK, Zhu TT, et al. Fluorescence sensor based on biosynthetic CdSe/CdS quantum dots and liposome carrier signal amplification for mercury detection. Anal Chem. 2020;92:3990–7. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b05508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bak S, Kim D, Lee H. Graphene quantum dots and their possible energy applications: a review. Curr Appl Phys. 2016;16:1192–201. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ma F, Li CC, Zhang CY. Development of quantum dot-based biosensors: principles and applications. J Mater Chem B. 2018;6:6173–90. doi: 10.1039/c8tb01869c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Singh RD, Sandhilya R, Bhargava A, Kumar R, Tiwari R, Chaudhury K, et al. Quantum dot based nano-biosensors for detection of circulating cell free miRNAs in lung carcinogenesis: frombiology to clinical translation. FrontGenet. 2018;9:616. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu J, Kwon B, Liu W, Anslyn EV, Wang P, Kim JS. Chromogenic/fluorogenic ensemble chemosensing systems. Chem Rev. 2015;115:7893–943. doi: 10.1021/cr500553d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fu Y, Zhao S, Wu S, Huang L, Xu T, Xing X, et al. A carbon dots-based fluorescent probe for turn-on sensing of ampicillin. Dyes Pigments. 2020;172:107846. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lan M, Zhao S, Wei X, Zhang K, Zhang Z, Wu S, et al. Pyrene-derivatized highly fluorescent carbon dots for the sensitive and selective determination of ferric ions and dopamine. Dyes Pigments. 2019;170:107574. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anand SK, Sivasankaran U, Jose AR, Kumar KG. Interaction of tetracycline with l-cysteine functionalized CdS quantum dots - fundamentals and sensing application. Spectrochim Acta Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2019;213:410–5. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2019.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leng F, Zhao XJ, Wang J, Li YF. Visual detection of tetracycline antibiotics with the turned on fluorescence induced by a metal-organic coordination polymer. Talanta. 2013;107:396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lu H, Zhang H, Li Y, Gan F. Sensitive and selective determination of tetracycline in milk based on sulfur quantum dot probes. RSC Adv. 2021;11:22960–8. doi: 10.1039/d1ra03745e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang T, Wei X, Zong Y, Zhang S, Guan W. An efficient and stable fluorescent sensor based on APTES-functionalized CsPbBr3 perovskite quantum dots for ultrasensitive tetracycline detection in ethanol. J Mater Chem C. 2020;8:12196–203. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wei W, He J, Wang Y, Kong M. Ratiometric method based on silicon nanodots and Eu(3+) system for highly-sensitive detection of tetracyclines. Talanta. 2019;204:491–8. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xue J, Li NN, Zhang DM, Bi CF, Xu CG, Shi NN, et al. One-step synthesis of a carbon dot-based fluorescent probe for colorimetric and ratiometric sensing of tetracycline. Anal Methods. 2020;12:5097–102. doi: 10.1039/d0ay01699c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ahmed SR, Cirone J, Chen A. Fluorescent Fe3O4 quantumdots for H2O2 detection. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2019;2:2076–85. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sudewi S, Li C-H, Dayalan S, Zulfajri M, Sashankh PVS, Huang GG. Enhanced fluorescent iron oxide quantum dots for rapid and interference free recognizing lysine in dairy products. Spectrochim Acta Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2022;279:121453. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2022.121453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu J, Sun Z, Deng Y, Zou Y, Li C, Guo X, et al. Highly water-dispersible biocompatible magnetite particles with low cytotoxicity stabilized by citrate groups. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:5875–9. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hu J, Zhang CY. Simple and accurate quantification of quantum yield at the single-molecule/particle level. Anal Chem. 2013;85:2000–4. doi: 10.1021/ac3036487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Spiridis N, Wilgocka-Ślęzak D, Freindl K, Figarska B, Giela T, Młyńczak E, et al. Growth and electronic and magnetic structure of iron oxide films on Pt(111) Phys Rev B. 2012;85:075436. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fouda MFR, ElKholy MB, Mostafa SA, Hussien AL, Wahba M, El-Shahat MF. Characterization and evaluation of nano-sized α-Fe2O3 pigments synthesized using three different carboxylic acid. Adv Mater Lett. 2013;4:347–53. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kumar B, Smita K, Cumbal L, Debut A. Biogenic synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles for 2-arylbenzimidazole fabrication. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2014;18:364–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li H, Zhang Y, Ding J, Wu T, Cai S, Zhang W, et al. Synthesis of carbon quantum dots for application of alleviating amyloid-beta mediated neurotoxicity. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2022;212:112373. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.112373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhao P, Zhu L. Dispersibility of carbon dots in aqueous and/or organic solvents. Chem Commun. 2018;54:5401–6. doi: 10.1039/c8cc02279h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moldovan CS, Onaciu A, Toma V, Marginean R, Moldovan A, Tigu AB, et al. Quantifying cytosolic cytochrome c concentration using carbon quantum dots as a powerful method for apoptosis detection. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:1556. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13101556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Safo IA, Werheid M, Dosche C, Oezaslan M. The role of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) as a capping and structure-directing agent in the formation of Pt nanocubes. Nanoscale Adv. 2019;1:3095–106. doi: 10.1039/c9na00186g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kwon SG, Hyeon T. Formation mechanisms of uniform nanocrystals via hot-injection and heat-up methods. Small. 2011;7:2685–702. doi: 10.1002/smll.201002022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim D, Mishima T, Tomihira K, Nakayama M. Temperature dependence of photoluminescence dynamics in colloidal CdS quantum dots. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:10668–73. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sarkar PP, Dhua SK, Thakur SK, Rath S. Analysis of the surface defects in a hot-rolled low-carbon C–Mn steel plate. J Fail Anal Prev. 2017;17:545–53. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang X, Qin J, Xue Y, Yu P, Zhang B, Wang L, et al. Effect of aspect ratio and surface defects on the photocatalytic activity of ZnO nanorods. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4596. doi: 10.1038/srep04596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cojocaru B, Avram D, Kessler V, Parvulescu V, Seisenbaeva G, Tiseanu C. Nanoscale insights into doping behavior, particle size and surface effects in trivalent metal doped SnO2. Sci Rep. 2017;7:9598. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09026-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Janke EM, Williams NE, She C, Zherebetskyy D, Hudson MH, Wang L, et al. Origin of broad emission spectra in InP quantum dots: contributions from structural and electronic disorder. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:15791–803. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b08753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cushing SK, Ding W, Chen G, Wang C, Yang F, Huang F, et al. Excitation wavelength dependent fluorescence of graphene oxide controlled by strain. Nanoscale. 2017;9:2240–5. doi: 10.1039/c6nr08286f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yuan L, Wang T, Zhu T, Zhou M, Huang L. Exciton dynamics, transport, and annihilation in atomically thin two-dimensional semiconductors. J Phys Chem Lett. 2017;8:3371–9. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b00885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu Z, Zhao W, Jiang J, Zheng T, You Y, Lu J, et al. Defect activated photoluminescence in WSe2 monolayer. J Phys Chem C. 2017;121:12294–9. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wu Z, Ni Z. Spectroscopic investigation of defects in two-dimensional materials. Nanophotonics. 2017;6:1219–37. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Eda O, Maier SA. Two-dimensional crystals: managing light for optoelectronics. ACS Nano. 2013;7:5660–5. doi: 10.1021/nn403159y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Koczkur KM, Mourdikoudis S, Polavarapu L, Skrabalak SE. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) in nanoparticle synthesis. Dalton Trans. 2015;44:17883–905. doi: 10.1039/c5dt02964c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zaini MS, Ying Chyi Liew J, Alang Ahmad SA, Mohmad AR, Kamarudin MA. Quantum confinement effect and photoenhancement of photoluminescence of PbS and PbS/MnS quantum dots. Appl Sci. 2020;10:6282. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gao Y, Yan X, Li M, Gao H, Sun J, Zhu S, et al. A “turn-on” fluorescence sensor for ascorbic acid based on graphene quantum dots via fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Anal Methods. 2018;10:611–6. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ge B, Li Z, Yang L, Wang R, Chang J. Characterization of the interaction of FTO protein with thioglycolic acid capped CdTe quantum dots and its analytical application. Spectrochim Acta Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2015;149:667–73. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2015.04.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zulfajri M, Dayalan S, Li WY, Chang CJ, Chang YP, Huang GG. Nitrogen-Doped carbon dots from averrhoa carambola fruit extract as a fluorescent probe for methyl orange. Sensors. 2019;19:5008. doi: 10.3390/s19225008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ünlü C, Tosun GÜ, Sevim S, Özçelik S. Developing a facile method for highly luminescent colloidal CdSxSe1−x ternary nanoalloys. J Mater Chem C. 2013;1:3026–34. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Guleroglu G, Unlu C. Spectroscopic investigation of defectstate emission in CdSe quantum dots. Turk J Chem. 2021;45:520–7. doi: 10.3906/kim-2101-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Saleviter S, Fen YW, Omar NAS, Daniyal WMEMM, Abdullah J, Zaid MHM. Structural and optical studies of cadmium sulfide quantum dot-graphene oxide-chitosan nanocomposite thin film as a novel SPR spectroscopy active layer. J Nanomater. 2018;2018:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Moon H, Lee C, Lee W, Kim J, Chae H. Stability of quantum dots, quantum dot films, and quantum dot light-emitting diodes for display applications. Adv Mater. 2019;31:e1804294. doi: 10.1002/adma.201804294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Eom NA, Kim TS, Choa YH, Kim WB, Kim BS. Surface oxidation behaviors of Cd-rich CdSe quantum dot phosphors at high temperature. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2014;14:8024–7. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2014.9389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Feng K, Engler G, Seefeld K, Kleinermanns K. Dispersed fluorescence and delayed ionization of jet-cooled 2-aminopurine: relaxation to a dark state causes weak fluorescence. ChemPhysChem. 2009;10:886–9. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200800816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Christensen EA, Kulatunga P, Lagerholm BC. A single molecule investigation of the photostability of quantum dots. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ha T, Tinnefeld P. Photophysics of fluorescent probes for single-molecule biophysics and super-resolution imaging. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2012;63:595–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032210-103340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Liu C, Zhang F, Hu J, Gao W, Zhang M. A mini review on pH-sensitive photoluminescence in carbon nanodots. Front Chem. 2020;8:605028. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.605028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pooja, Chowdhury P. Functionalized CdTe fluorescence nanosensor for the sensitive detection of water borne environmentally hazardousmetal ions. OptMater. 2021;111:110584. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Berezin MY, Achilefu S. Fluorescence lifetime measurements and biological imaging. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2641–84. doi: 10.1021/cr900343z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tang Y, Huang H, Peng B, Chang Y, Li Y, Zhong C. A thiadiazole-based covalent triazine framework nanosheet for highly selective and sensitive primary aromatic amine detection among various amines. J Mater Chem. 2020;8:16542–50. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bajar BT, Wang ES, Zhang S, Lin MZ, Chu J. A guide to fluorescent protein FRET pairs. Sensors. 2016;16:1488. doi: 10.3390/s16091488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rhodes AA, Swartz BL, Hosler ER, Snyder DL, Benitez KM, Chohan BS, et al. Static quenching of tryptophan fluorescence in proteins by a dioxomolybdenum(VI) thiolate complex. J Photochem Photobiol Chem. 2014;293:81–7. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tang X, Wang L, Ye H, Zhao H, Zhao L. Biological matrix-derived carbon quantum dots: highly selective detection of tetracyclines. J Photochem Photobiol Chem. 2022;424:113653. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chen S, Yu YL, Wang JH. Inner filter effect-based fluorescent sensing systems: a review. Anal Chim Acta. 2018;999:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2017.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ge J, Ma D, Duan G, Yan Z, Yang L, Yang D, et al. A novel probe for tetracyclines detection and its applications in cell imaging based on fluorescent WS2 quantum dots. Anal Chim Acta. 2022;1221:340130. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2022.340130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Yuri Borodko SEH, Matthias Koebel, Peidong Yang, Heinz Frei, Gabor A, Somorjai Probing the interaction of poly(vinylpyrrolidone) with platinum nanocrystals by UV-Raman and FTIR. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:23052–9. doi: 10.1021/jp063338+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Jiao ZH, et al. Recyclable luminescence sensor for sinotefuran in water by stable cadmium-organic framework. Anal Chem. 2021;93(17):6599–603. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c01007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hildebrandt IMaN FRET - Förster Resonance Energy Transfer_ From Theory to Applications. Wiley-VCH; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Chou KF, Dennis AM. Forster resonance energy rransfer between quantum dot donors and quantum dot acceptors. Sensors (Basel) 2015;15(6):13288–325. doi: 10.3390/s150613288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(a) temperature stability of IO QDs. (b) photostability of IO QDs (LED: Light-emitting diode, LW: Long wavelength (λ=365 nm), SW: Short wavelength (λ=265 nm). (c) Ionic strength effects on IO QDs. (d) pH stability of IO QDs. and (e) storage time stability of IO QDs.

Effect of (a) pH value (3–11) of IO QDs and IO QDs/TCy system on FL intensity. (b) time reaction (0–30 min) after adding TCy. (c) various buffers before and after adding TCy on FL quenching ratio (F/F0).

Luminescence of IO QDs in the presence of various antibiotics under (a) daylight and (b) UV light.