Abstract

Fc receptors are involved in a variety of physiologically and disease-relevant responses. Among them, FcγRIIA (CD32a) is known for its activating functions in pathogen recognition and platelet biology, and, as potential marker of T lymphocytes latently infected with HIV-1. The latter has not been without controversy due to technical challenges complicated by T-B cell conjugates and trogocytosis as well as a lack of antibodies distinguishing between the closely related isoforms of FcγRII. To generate high-affinity binders specific for FcγRIIA, libraries of designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins) were screened for binding to its extracellular domains by ribosomal display. Counterselection against FcγRIIB eliminated binders cross-reacting with both isoforms. The identified DARPins bound FcγRIIA with no detectable binding for FcγRIIB. Their affinities for FcγRIIA were in the low nanomolar range and could be enhanced by cleavage of the His-tag and dimerization. Interestingly, complex formation between DARPin and FcγRIIA followed a two-state reaction model, and discrimination from FcγRIIB was based on a single amino acid residue. In flow cytometry, DARPin F11 detected FcγRIIA+ cells even when they made up less than 1% of the cell population. Image stream analysis of primary human blood cells confirmed that F11 caused dim but reliable cell surface staining of a small subpopulation of T lymphocytes. When incubated with platelets, F11 inhibited their aggregation equally efficient as antibodies unable to discriminate between both FcγRII isoforms. The selected DARPins are unique novel tools for platelet aggregation studies as well as the role of FcγRIIA for the latent HIV-1 reservoir.

Keywords: Fc receptors, binding site, thrombocytes, HIV, surface plasmon resonance, DARPin

Fc receptors form a family of immunoglobulin (Ig)-binding transmembrane proteins which differ by their specificities and affinities for the constant parts of Ig subtypes. In humans, the Fcγ receptor proteins form the largest group exhibiting high (FcγRI) or low affinities (FcγRII, FcγRIII) for IgG. Three different FcγRII proteins are distinguished. FcγRIIA exhibits activation of immune cells and platelets, while FcγRIIB is inhibitory. This difference is mediated by motifs in the cytoplasmic tails of the receptors, that is, the immunoreceptor-tyrosine–based activating motif in FcγRIIA and FcγRIIC, and the inhibitory motif immunoreceptor-tyrosine–based inhibiting motif in FcγRIIB. Various splice variants have been described, all of which affect the composition of the cytoplasmic tails of FcγRIIs, while the extracellular parts of all three isoforms invariably contain two domains (D1 and D2). Amino acid sequences between FcγRIIA and FcγRIIC are identical, while FcγRIIA and FcγRIIB share >90% identity. The Fc-binding epitopes are located on D2 and encompass a prominent polymorphism (H134R) of FcγRIIA. H134R, previously referred to as H131R, results in reduced IgG2 binding with consequences for the susceptibility to infections (1).

Platelets represent the most prominent source of FcγRIIA in human blood which is due to their high abundance compared to other types of blood cells. On platelets, FcγRIIA is involved in hemostasis and recognition of immune complexes (2). Notably, platelets do not express FcγRIIB. Accordingly, the monoclonal antibody (mAb) IV.3 and derived fragments, which cannot distinguish between both isoforms, are used as fundamental tool in platelet research as well as for diagnostic purpose (3). The IV.3 mAb induces platelet activation when cross-linked with a secondary antibody. In heparin-induced thrombosis, IV.3 mAb inhibits platelet aggregation by interfering with the interaction between FcγRIIA and patient-derived antibody–PF4–heparin complexes (3).

Apart from platelets, FcγRIIs are present on most leukocytes with important differences in isoform distribution. While B lymphocytes express exclusively FcγRIIB, which serves the important role of antibody-induced inhibition (4, 5), the presence and role of FcγRIIs on T cells are far less clear (6). A major interest into FcγRIIA on CD4+ T cells was fueled by its identification as a cellular marker of the HIV-1 reservoir (7). Conflicting data followed, and the pursuing debate evolved in large parts around the difficulties in the purification of this very minor T cell subset. In brief, a high degree of B cell–induced contamination was observed and subsequently identified as a probable cause of the discrepant findings (8, 9, 10, 11, 12). The inability of available antibodies to distinguish the FcγRII contributes to this issue. Consequently, the development of specific binders for FcγRIIA is of enormous scientific importance.

Designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins) have become an attractive alternative to mABs (13). Derived from cellular ankyrin proteins, their α-helical fold with exposed loop regions harboring contact residues against the target protein makes them highly stable and less prone to aggregation than single-chain antibody fragments. By connecting the desired number of repeat units, contact areas and binding affinity can be controlled and fine-tuned. Moreover, DARPins with different affinities and specificities can be combined into a single molecule thus generating multivalent binders, for example, with specificities for vascular endothelial growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor as well as human serum albumin to increase serum half-life (14). DARPins can be selected from large libraries of combinatorially diversified variants by ribosomal display for binding to the target protein of choice which is immobilized to a matrix. This approach results in DARPins with affinities up to the picomolar range (15) and high specificity even when closely related proteins exist. Off-rate selections with soluble on-target and counter selections with off-target proteins added to advanced selection rounds can be used to select for such properties. Applications range from chaperone functions in crystallization studies to detection/diagnostic tools and therapeutic drugs. The latter also include receptor-targeted viral vectors by displaying DARPins on the vector surface that mediate specific binding and gene delivery into particular cell types of interest (16) such as T lymphocytes for the delivery of chimeric antigen receptors (17). For the generation of DARPins binding to a cell surface protein of choice, its extracellular part is expressed as Fc fusion protein in 293T cells, purified, and used as bait during the selection process. This approach has been successfully applied for DARPins recognizing cell surface receptors such as the glutamate receptor subunit 4 (GluA4), the endothelial cell marker CD105, and the natural killer cell surface protein NKp44 (17). Also, DARPins against the Fc receptors FcγRIIB and FcεRI have been generated, which when connected in bivalent configuration inhibit allergic reactions (18).

Here, we generated FcγRIIA-specific DARPins with low nanomolar affinities that demonstrated no cross-reactivity to FcγRIIB. A single amino acid residue located within the Fc-binding epitope on D2 was found to be responsible for the robust discrimination between FcγRIIA and FcγRIIB. DARPin F11 taken forward to applications identified a small CD4 T lymphocyte subpopulation to be FcγRIIA-positive. When applied in platelet assays, F11 inhibited FcγRIIA-dependent platelet activation and aggregation.

Results

Selection of FcγRIIA-specific DARPins

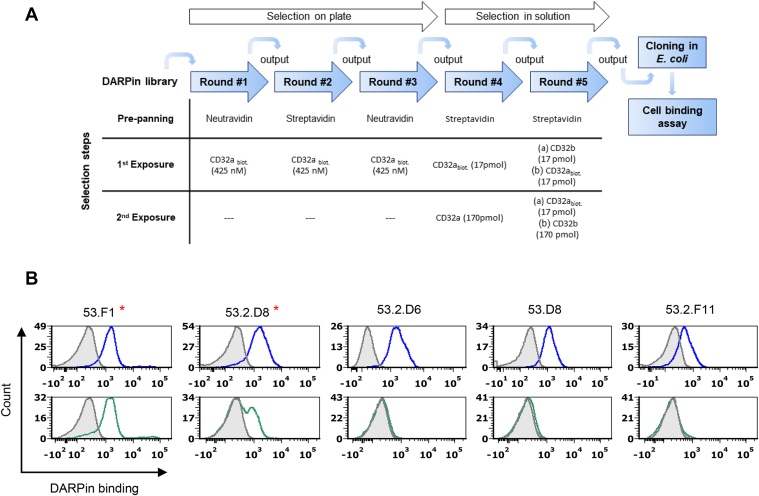

Binders were selected by ribosomal display from the DARPin library VV-N3C (17), which encodes DARPins with an N- and a C-terminal capping domain as well as three repeat units carrying seven diversified amino acid positions each (Fig. S1A). In total, five selection rounds against the immobilized extracellular domain of FcγRIIA as bait protein were carried out. To prevent selection of binders recognizing FcγRIIB, counterselection was implemented using soluble FcγRIIB-His protein in the late rounds (Fig. 1A). The selection procedure resulted in 285 candidates, which were expressed in Escherichia coli and tested for binding to SupT1 cells stably expressing FcγRIIA or FcγRIIB. We identified 46 candidates that reproducibly bound to SupT1-CD32a (FcγRIIA) cells (Fig. S2). Among them, only two (53.F1 and 53.2.D8) also interacted with SupT1-CD32b (FcγRIIB) cells, while for all others, no binding to these cells was detectable by flow cytometry (Figs. 1B and S2). Sequencing revealed that 32 DARPins had unique amino acid sequences (Fig. S1, B and C), but roughly two groups could be distinguished. The bigger group shared high sequence homology and included variants such as 53.2.D6 and 53.D8 that differed only by few residues within the framework regions. Besides D6 and D8, we picked the DARPin 53.2.F11 (further on termed F11) as representative of those DARPins showing more unique sequences (Fig. S1D) for affinity measurement by surface plasmon resonance (SPR). To avoid any interference with target binding by the His-tag, a protease cleavage site (TEV) was inserted resulting in F11-TEV. Moreover, a bi-DARPin configuration of F11 (2xF11) was constructed in which two DARPins were connected by a flexible (G4S)2 linker region (Fig. S1A).

Figure 1.

Identification of FcɣRIIA-specific DARPins.A, overview of the DARPin screening process via ribosomal display. B, crude Escherichia coli extracts of five clones picked from the output of the fifth selection round were analyzed for binding to FcɣRIIA and FcɣRIIB via flow cytometry using SupT1-CD32a cells (blue lines, top panels) and SupT1-CD32b cells (green lines, bottom panels). DARPins were detected with an APC-labeled HA-tag–specific antibody. As control cells were incubated with the HA-specific antibody only (filled gray curves). Representative histograms for the indicated DARPins are shown. Two DARPins, which recognized both cell lines, are labeled by the red star. The other three DARPins were taken forward to further characterization. DARPin, designed ankyrin repeat protein.

Selected DARPins bind FcγRIIA with high affinity

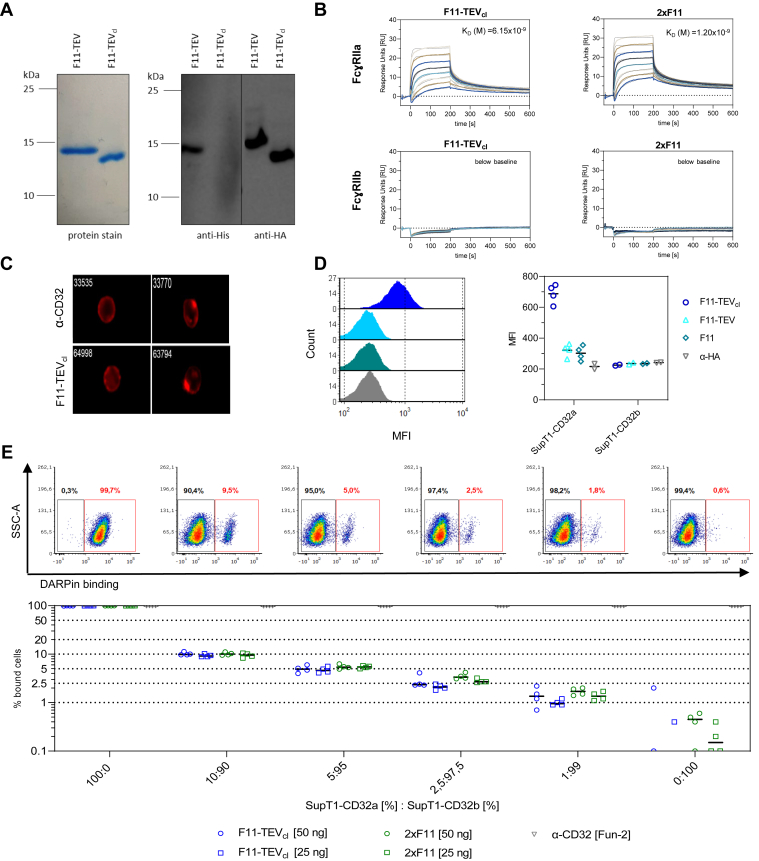

Bacterial expression followed by chromatography purification resulted in highly pure F11-TEV protein and the F11-TEVcl version with the His-tag completely removed (Fig. 2A). Mass spectrometry analysis supported successful purification and proteolytic cleavage, confirming that polypeptides derived from a few faint additional bands apparent upon higher resolution SDS-PAGE had the same amino acid sequence as the main protein product, all in full agreement with the predicted F11 sequence (Fig. S3).

Figure 2.

Discrimination between FcɣRIIA and FcɣRIIB.A, reducing SDS-PAGE (left) and Western blot analysis (right) of F11 purified from bacterial lysates before (F11-TEV) or after cleavage of the TEV site (F11-TEVcl). F11 was detected by PageBlue protein staining (left) and by an anti-His-tag–specific antibody before cleavage (middle) or an anti-HA–specific antibody after cleavage of the His-Tag (right). B, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to quantify binding of F11-TEVcl (left) and 2xF11 (right) to FcɣRIIA (top) and FcɣRIIB (bottom), immobilized at ∼100 RU, respectively. For better visibility, only one curve per concentration is shown. C–E, setting up flow cytometry analysis with F11. C, two representative image stream photos of SupT1-CD32a cells bound by the FUN-2 antibody (top) or F11-TEVcl (bottom), respectively. D, testing of various F11 formats (each 500 ng) for binding to SupT1-CD32a and SupT1-CD32b cells. Representative histograms (left) and all replicas (right) are shown as mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs). E, F11 binding in mixed cell populations. The indicated ratios of SupT1-CD32a and SupT1-CD32b cells were stained with 25 ng and 50 ng of F11-TEVcl or 2xF11, respectively. The FUN-2 antibody was applied as control. Exemplary dot plots for all conditions (top) and summarized data sets are shown with N = 4 replicas (bottom).

To determine the binding affinities of the selected DARPins, SPR measurements against immobilized FcγRIIA as well as FcγRIIB were carried out. Complex formation with FcγRIIA occurred rapidly reaching equilibrium within seconds (Figs. 2B and S4). Remarkably, SPR did not detect any binding of F11 or 2xF11 to FcγRIIB (Fig. 2B). This was also the case for additional other DARPins (Fig. S4). Interestingly, signals further increased at steady state equilibrium, which suggested a second reaction at the FcγRIIA receptor (Fig. S5B). Such a behavior would be in agreement with a two-state reaction model, thus two different reactions occurring on the chip surface. To validate the model, complex formation was analyzed under different injection times. Indeed, the dissociation rates of F11 differed with varying injection times. Only for the two-state model, measured curves and fitted curves overlapped completely with if at all minimal errors (Fig. S5). Based on this, we determined the dissociation constants (KDs) for F11, D6, and D8 to be in the low nanomolar range (Table 1). The high reproducibility of the calculated KDs in repeated measurements including various batches of F11 or 2xF11 confirmed the validity of our approach (Table 1). Notably, there were substantial differences in KDs for different configurations of a particular DARPin observed. The biggest increase in affinity by about 3-fold for F11 and by more than 10-fold for D8 resulted from insertion of the TEV cleavage site between the His and HA tags. Most of the increase became evident even in the absence of proteolytic cleavage of the His-tag, which however improved affinities further. Looking at the rate constants of complex formation (ka1 and kd1; Table 1), this improvement in KD was due to faster association, while dissociation remained almost the same. The bi-DARPin configuration of F11 resulted in a 2-fold improvement in KD as expected (Table 1). The SPR data were further confirmed by immobilizing F11 on the chip and adding soluble FcγRIIA with the H134R polymorphism. This setting resulted only in a slightly reduced KD of 12.5 nM, demonstrating that binding of F11 to FcγRIIA was independent from the polymorphism (Table 1 and Fig. S5).

Table 1.

Affinities of DARPin variants for FcγRIIA

| DARPin | ka1 (1/Ms) | kd1 (1/s) | ka2 (1/s) | kd2 (1/s) | KD (nM) | Chi2 (RU2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w/o TEV site | ||||||

| D8 | 6.04E+05 | 3.66E-01 | 8.43E-04 | 1.33E-03 | 371.3 | 0.22 |

| F11 | 5.07E+05 | 2.32E-02 | 2.99E-03 | 1.13E-03 | 12.5 | 0.12 |

| With TEV site | ||||||

| D8 | 4.62E+05 | 1.66E-01 | 5.63E-03 | 2.86E-04 | 17.3 | 0.09 |

| F11 | 3.35E+05 | 2.52E-02 | 6.93E-03 | 3.91E-04 | 4.0 | 0.41 |

| D6 | 5.97E+05 | 1.57E-01 | 5.81E-03 | 4.14E-04 | 17.5 | 0.13 |

| 2xF11 | 2.40E+07 | 6.07E-01 | 4.45E-03 | 1.59E-03 | 6.6 | 1.66 |

| TEV site cleaved | ||||||

| D8 | 1.57E+05 | 1.87E-01 | 1.29E-03 | 9.05E-06 | 8.3 | 0.21 |

| F11 (batch #1) | 1.65E+06 | 3.55E-02 | 4.38E-03 | 1.90E-03 | 6.5 | 0.25 |

| F11 (batch #2) | 1.11E+06 | 2.00E-02 | 2.69E-03 | 1.39E-03 | 6.1 | 0.14 |

| F11 (batch #2) | 1.23E+06 | 2.68E-02 | 5.18E-03 | 2.46E-03 | 7.0 | 0.55 |

| F11 imm.a | 6.18E+05 | 1.45E-01 | 8.66E-03 | 4.85E-04 | 12.5 | 0.33 |

| D6 | 7.05E+05 | 1.60E-01 | 9.47E-04 | 1.13E-05 | 2.7 | 0.21 |

| 2xF11 (#1) | 3.91E+06 | 1.75E-02 | 2.83E-03 | 1.04E-03 | 1.2 | 0.15 |

| 2xF11 (#1) | 2.25E+06 | 1.58E-02 | 3.87E-03 | 1.41E-03 | 1.9 | 0.63 |

In this setting, F11 was immobilized onto the chip and soluble FcγRIIA(H134R) was used as binding partner.

Next, we assessed binding to cell-associated FcγRIIA by flow cytometry using SupT1 cells engineered to express FcγRIIA or FcγRIIB. Image stream analysis of SupT1-CD32a cells bound by F11 revealed a typical cell surface staining pattern very similar to the signal produced by the CD32-specific antibody FUN-2 (Fig. 2C). Flow cytometry also confirmed the beneficial effect of cleavage of the His-tag which increased the mean fluorescence intensity by about 3-fold (Fig. 2D). To further study the selectivity of F11 in recognizing FcγRIIA versus FcγRIIB, we mixed the two cell lines in different ratios. At each ratio, starting with 10% target cells going down to just 1%, F11 and 2xF11 were highly selective for SupT1-CD32a cells. Even the lowest ratio was reliably detected (Fig. 2E).

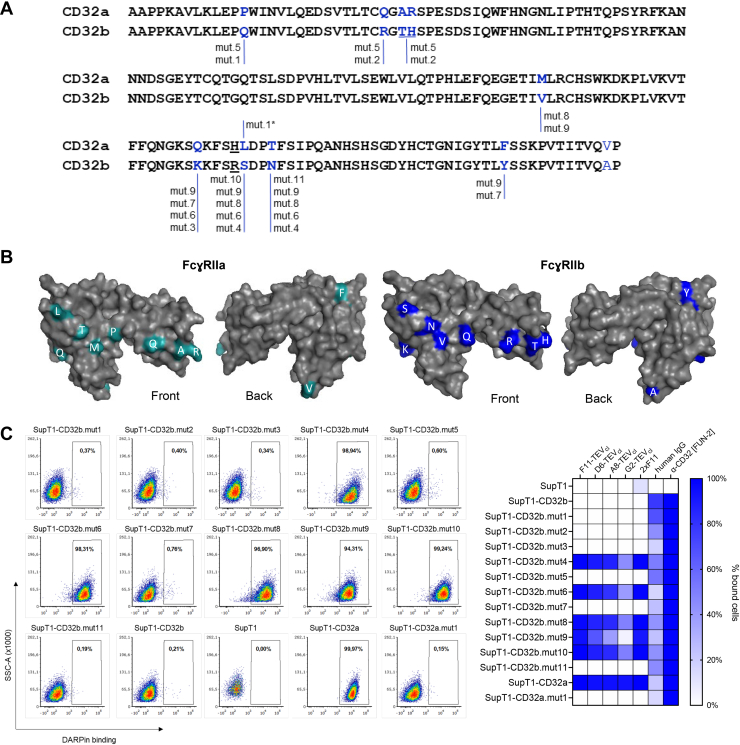

Mapping of the DARPin-binding site on FcγRIIA

The sequences of the extracellular domains of FcγRIIA and FcγRIIB differ by only 12 amino acid residues (Fig. 3, A and B). To identify which residues contributed to the exclusive DARPin binding to FcγRIIA, a series of mutated FcγRIIB proteins was generated with a variable number of residues unique for FcγRIIA in the extracellular domain (Figs. 3A and S6). The mutant receptors were expressed on SupT1 cells and assessed for DARPin binding. As positive controls, human IgG and the FUN-2 antibody were included. All mutant proteins were detected by the antibody and IgG, confirming efficient cell surface expression and excluding that any of the replacements had impaired overall folding (Fig. 3C). Four mutant receptors (mut4, mut6, mut8, and mut9) gained binding of five different DARPins including F11 and 2xF11 with binding efficiencies identical to those observed with FcγRIIA (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, all these mutant receptors had two residue exchanges in common, which were S135L and N138T. To test each of these residues separately, single point mutants were generated. Mutation N138T (mut.11) in FcγRIIB did not trigger DARPin binding. In contrast, the single residue exchange S135L (mut.10) was sufficient to enable FcγRIIB to recognize all DARPins. To confirm the importance of FcγRIIA-residue 135 for selective DARPin binding, we also generated the corresponding exchange in FcγRIIA (L135S, mut.1) which led to a complete loss of binding (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Identification of DARPin-binding site.A, alignment of the FcɣRIIA (P12318) and FcɣRIIB (P31994) ectodomain sequences covered by the 3D structure using ClustalW. The ten differing amino acid residues are highlighted in blue; the polymorphism is underlined. Residues in bold blue were altered in the mutated FcɣRIIB proteins annotated below. The single mutant FcɣRIIA protein is labeled by an asterisk. B, positions of the altered amino acids in the crystal structures of FcɣRIIA (PDB: 1h9v) and FcɣRIIB (PDB: 2FCB). C, binding of DARPins, IgG, and FUN-2 antibody to the mutant receptors expressed on SupT1 cells. Exemplary FACS plots for the binding of F11-TEVcl to the indicated SupT1 cells are provided (left). Binding data for various DARPins (200 ng each) as well as for human IgG are shown on the right as heat map diagram (right). The FUN-2 antibody was included as positive control for proper expression of the mutant receptors. Average values of two independent measurements are shown. DARPin, designed ankyrin repeat protein; Ig, immunoglobulin.

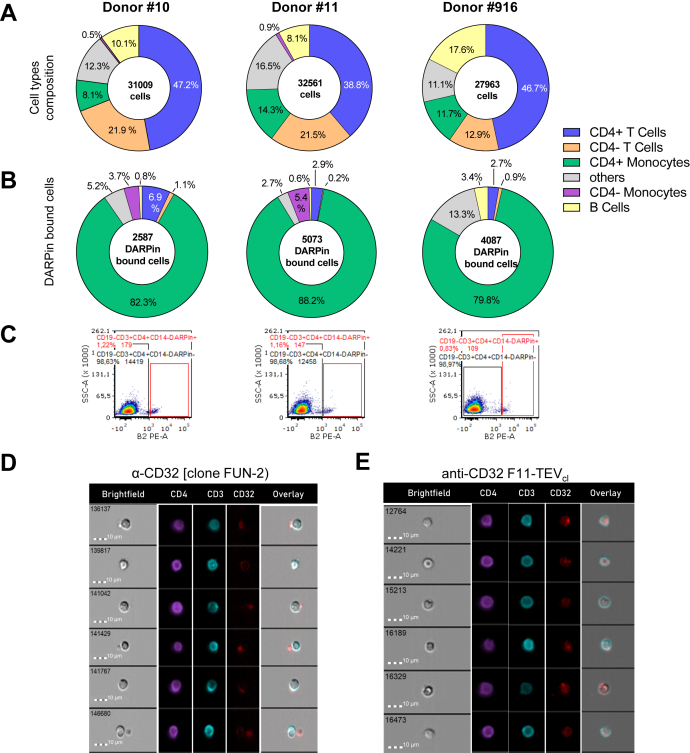

Detection of FcγRIIA-positive blood cells

Having a unique tool for specific detection of FcγRIIA at hand, we next assessed which cell lineages in human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) are detected by F11 staining. PBMC analyzed from three different donors contained CD4+ and CD4− T lymphocytes as largest fraction followed by B cells and monocytes (Fig. 4A). Cells detected by F11 were mainly monocytes. Besides, F11 also bound to lymphocytes. Notably, a reproducible signal on a small fraction (0.8–1.2%) of CD4+ T cells was detected in all three donors (Figs. 4, B and C and Table S4). To further characterize the binding behavior on PBMCs, we compared the staining pattern of F11 to the commonly used human CD32 antibody FUN-2 by imaging cytometry. FUN-2 detected CD19+ B cells and CD14+ monocytes, while F11 majorly surface-stained CD14+ monocytes (Figs. 4D and S7–S9). The frequencies of CD32+CD4+ T cells were similar between FUN-2– and F11-stained samples and in agreement with the standard cytometry measurements (median 0.8–1.2% of CD4+ T cells) strongly suggesting the expression of FcγRIIA on CD4+ T cells. Interestingly, the CD32 signal on CD4+ T lymphocytes detected by FUN-2 was for a median of 46% derived from small entities attached to T lymphocytes, whereas this pattern occurred in only 18% of cases in F11-stained samples. The average diameter of these entities was 2.46 μm (N = 10), thus about one-third of the size of the T cells (7.84 μm; N = 10). This diameter is exactly the expected number for platelets (2–3 μm), thus confirming that the image stream analysis detected T cell-platelet conjugates. The reduced recognition of platelets by F11 led to a relatively more frequent detection of a dim but membrane-spread staining pattern of FcγRIIA on CD4+ T cells (Figs. 4E and S9), demonstrating bona fide cell surface expression of FcγRIIA on T lymphocytes.

Figure 4.

Detection of FcɣRIIA-expressing T lymphocytes. Human PBMC isolated from blood donations were isolated and without further activation stained with F11-TEVcl (0.05 μg) and antibodies for analysis by flow cytometry. The experiment was performed with PBMC from three different donors. See Fig. S7 for gating strategy. Total cell numbers are provided in the center of the pie charts. The relative frequencies of the detected cell types are shown in (A), the cell types bound by F11 in (B). C, FACS plots showing FcɣRIIA-positive CD4+ T lymphocytes (CD19−/CD3+/CD4+/CD14−/F11+) for each donor. D and E, representative pictures obtained by image stream analysis of human PBMC stained with the panel of antibodies plus FUN-2 (D) or F11 (E). Overall brightness of images shown in the CD32 panels was edited. Raw data without editing are provided in the Supplementary material (Figs. S8 and S9). PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Inhibition of platelet aggregation

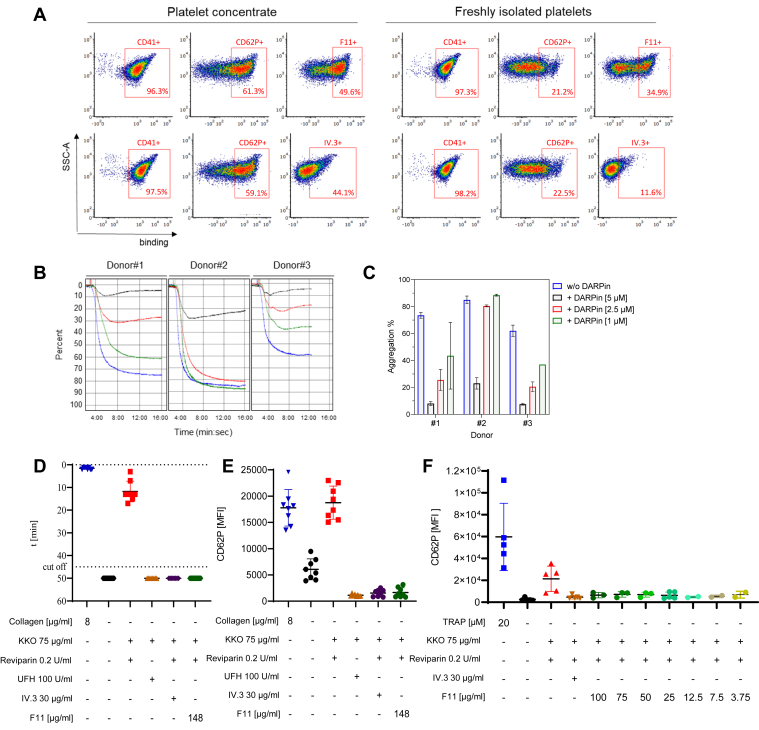

Next, we assessed the activities of F11 in different platelet aggregation assays. Concentrates of human platelets showing a high level of activation as revealed by staining against CD62P as well as freshly isolated platelets, which were mainly CD62P negative, were included (Fig. 5A). F11 bound not only platelets derived from the concentrates equally efficient as the IV.3 antibody but also freshly isolated platelets. For these, its binding activity was more pronounced than that of IV.3 (Fig. 5A). For inhibition of platelet aggregation, platelets were pretreated with increasing amounts of F11 prior to the addition of IV.3 and anti-mouse F(ab)2-IgG to induce platelet activation via receptor cross-linking. F11 inhibited platelet aggregation in a dose-dependent manner and with an inhibition response which varied among donors. On average, 5 μM F11 decreased the aggregation of platelets for all donors to a minimum of 12 ± 8%, which corresponded to a total reduction of 60% compared to the aggregation control (74 ± 11%) (Figs. 5, B and C and S10, A and B). Upon platelet activation, chemokines such as RANTES and CXCL7/NAP-2 are released from the α-granules, and membrane proteins such as CD62P are cleaved from the platelet surface. Inhibition of platelet aggregation by F11 was accompanied by decreased levels of RANTES, CD62P, and CXCL7/NAP-2 (Fig. S10, C–E). To test F11 in a more disease-relevant approach, KKO-dependent heparin-induced platelet aggregation (HIPA) assays were performed. While collagen, as well as reviparin, induced platelet aggregation already in the first 15 min of the assay, platelets treated with the positive controls, unfractionated heparin or IV.3 mAb did not aggregate. F11 was equally active as the positive controls, since in its presence, platelet aggregation was not detectable even after 50 min of incubation (Fig. 5D). The latter observation was confirmed by the lack or reduction of the activation marker CD62P on the platelet cell surface (Fig. 5E). Titration of F11 showed that even when the DARPin was used in 39-fold lower amounts, no or low levels of platelet activation could be detected by flow cytometry (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5.

F11 interferes with platelet aggregation.A, binding of F11 and the IV.3 antibody to human platelets either from stored concentrated (left) or freshly isolated material (right). Fixed platelets were incubated with CD41- and CD62P-specific antibodies as well as F11 (upper panels) or IV.3 (bottom panels). FACS plots gated on CD41-positive cells are shown, respectively. B and C, inhibition of platelet aggregation induced by IV.3/Fab2 cross-linking. Aggregation was quantified by light transmission aggregometry. For F11-mediated inhibition, platelets were preincubated with 5 μM, 2.5 μM, or 1 μM F11. B, exemplary curves from experiments with platelets from three different donors. C, summarized measurements of the aggregometry with N = 2 technical replicas per donor. D, inhibition of heparin-induced platelet aggregation by HIPA test. Platelets assessed were derived from N = 8 different donors. E and F, inhibition of platelet activation detected as MFI of CD62P expression by flow cytometry. E, high F11 dose used on the same platelet donors as in (D). F, titration of F11 (100–3.75 μg/ml) on different donors (N = 5). HIPA, heparin-induced platelet aggregation; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Discussion

We describe DARPins specific for the extracellular part of FcγRIIA. These DARPins do not show any cross-reactivity to the closely related FcγRIIB. This is remarkable since the extracellular parts of both receptor isoforms are more than 90% identical and differ by only 12 residues. The clear-cut discrimination was demonstrated for several different DARPins taken forward to subsequent characterization after the selection and screening processes. Key for this achievement was the implementation of a counterselection against FcγRIIB in the ribosomal display process. Absence of cross-reactivity was demonstrated by SPR against soluble purified FcγRIIB protein as well as by flow cytometry against cell surface–exposed complete FcγRIIB protein. Both assay systems thus provided consistent results.

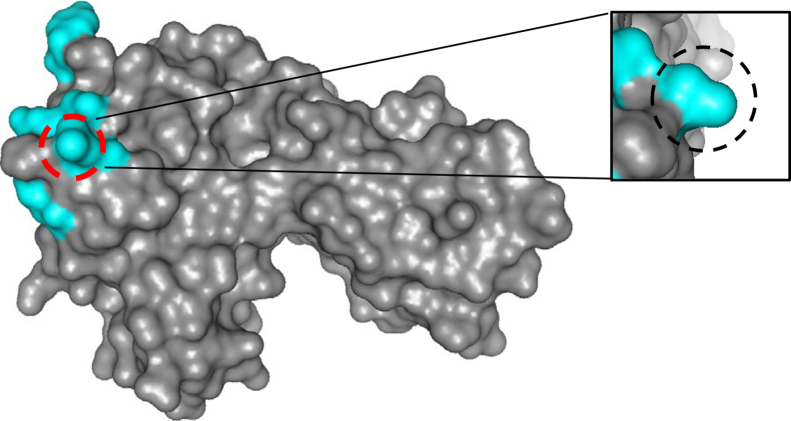

By successively replacing FcγRIIB residues with the corresponding residues of FcγRIIA, we identified the serine residue in position 135 of FcγRIIB as causative for not being recognized by the DARPins. DARPin binding was gained by replacing the serine residue with the corresponding leucine residue from FcγRIIA. Interestingly, this leucine residue belongs to the contact residues for Fc binding and accordingly localizes with the Fc-binding epitope of FcγRIIA (Fig. 6). Although hydrophobic, L135 is located on the surface close to the H134R polymorphism, which, however, did not influence recognition by F11. L135 has been previously identified as critical for binding of the antibody IV.3 to FcγRIIA (19). While the authors in this paper suggested IV.3 to preferentially bind FcγRIIA over FcγRIIB, preblocking of FcγRIIB with specific antibodies is required to achieve selective staining of FcγRIIA-positive cells with IV.3 (20). In this context, it is necessary to emphasize that IV.3, as any monoclonal antibody, differs from DARPins by the presence of the Fc domain, which despite Fc blocking may complicate selective detection of a particular Fc receptor. With the DARPins described here, this necessity will now become obsolete and the combination with other antibodies in downstream experiments enabled.

Figure 6.

IgG-binding site on FcɣRIIA. Crystal structure of FcɣRIIA (PDB: 3YR4). Contact residues for the Fc domain of IgG are highlighted in cyan. Residue L135 identified as critical for binding of DARPin F11 is labeled by the red circle. DARPin, designed ankyrin repeat protein; Ig, immunoglobulin.

An unexpected observation of our study was the binding kinetic of DARPin F11 to FcγRIIA. The initially, rapidly formed complex was stable only in the presence of a surplus of F11. In the absence of free F11, the majority of this initial complex dissociated and a highly stable complex remained. Our careful SPR analysis revealed that the complex formation was clearly more in agreement with a two-state reaction model than with the 1:1 model. This behavior has also been described for the binding of IgG to FcγRIIA (21). On the molecular level, this can be explained by a conformational change in FcγRIIA induced by the initial contact with F11. This behavior is not unique for the FcγRIIA receptor but has been described for FcγRI and FcγRIIIA (22, 23). Independently from that, the low nanomolar affinity and the high stability of the second complex make F11 an important novel tool for applications in biomedicine.

Antiretroviral therapy suppresses HIV-1 replication and prevents the development of AIDS but is unable to eradicate the virus. The main obstacle for an HIV-1 cure is the viral reservoir, where HIV-1 “hides” in host cells despite decades of antiretroviral therapy, just to reignite active replication if therapy is stopped (24). Thus, eradicating or at least significantly depleting the reservoir will be essential to achieve a cure. Therefore, there is continuous interest to identify cellular markers of the reservoir (25, 26) and FcγRIIA (CD32a) is among the most promising. To better understand the reservoir biology, it is important to determine what role FcγRIIA may have on latently infected cells. Recently, it was suggested that CD4+ T cells that express CD32 might be less susceptible to antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity against HIV-1 and therefore have a selective advantage for viral persistence (27). However, this study, as many others, used FUN-2 antibody to sort CD32+ cells, and this antibody does not distinguish between FcγRIIA and FcγRIIB. Our ImageStream analysis revealed that signals derived from staining with FUN-2 can result from platelets associated with T lymphocytes. These cell clusters were substantially reduced by specific detection of FcγRIIA with F11. The remaining cell clusters may have been artificially favored by aggregates of the proteins used for cell staining. While we cannot formally exclude that F11 contributed, it is well established that DARPins are extraordinary stable and usually do not form aggregates (13). Also F11 did not show any detectable aggregates over a wide temperature range and even when heated above its melting point of 95 °C, while IgG1 denatured at 74 °C and aggregated under these conditions (Fig. S11). It will be particularly revealing to apply fluorescently labeled F11 for this purpose in future, thereby avoiding any antibody molecules.

Independently from that, our data on F11-labeled blood cells from several donors support the existence of FcγRIIA-positive CD4+ T lymphocytes. Further studies will be required including donor lymphocytes from people living with HIV-1 to confirm this observation. The DARPins described in the current study will be unique tools for this purpose and may also be used as targeting ligands on the surface of viral vectors (28). Finally, F11’s ability to interfere with FcγRIIA-dependent platelet activation makes it an easy-to-apply tool to enhance specificity of functional tests for PF4-dependent, platelet-activating antibodies in heparin-induced thrombosis and in vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia (29).

Experimental procedures

Cell culture

Adherent HEK293T (ATCC CRL-11268) and HT1080 (ATCC CCL-121) cells were cultivated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Biochrom) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich). Suspension SupT1 (ARP-100 Human T Cell Lymphoma, HIV Reagent Program) cells were cultivated in Advanced RPMI (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 2% FCS and 2 mM L-glutamine. SupT1 cells expressing FcγRIIA with the histidine polymorphism at position 131 (SupT1-CD32a, SupT1-CD32a.mut1, SupT1-CD32b, SupT1-CD32b.mut1-11) were generated by transduction with lentiviral vectors (LVs) and cultivated in medium supplemented with 2 μg/ml puromycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Transduced cells were selected with puromycin for at least 2 weeks.

Expression plasmids

For generation of cells overexpressing human FcγRIIA or FcγRIIB, the plasmids (HG10374-NM; HG10259-NM;Sino Biological, Inc) encoding for the corresponding receptor sequence were PCR amplified adding the restriction sites PacI and SpeI and cloned via the restriction sites into an LV transfer vector, encoding the spleen focus-forming virus promoter, an internal ribosome entry site element followed by a puromycin resistance gene, and the woodchuck posttranscriptional regulatory element resulting in the plasmids pSEW-Myc-CD32a-IP and pSEW-Myc-CD32b-IP. For chimeric receptors between FcγRIIA and FcγRIIB, particular codons were altered by PCR using appropriate primers or the DNA sequence was synthesized (GeneArt; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and subsequently cloned into the LV transfer vector resulting in the plasmids pSEW-Myc-CD32a.mut1-IP and pSEW-Myc-CD32b.mut (1–11)-IP. Numbering of amino acid residues in FcγRIIA is according to Ramsland et al. (19).

Ribosome display

Ribosome display selection was carried out basically as described (17). For the first three selection rounds, the translated VV-N3C DARPin library was subjected to prepanning steps with immobilized neutravidin or streptavidin (66 nM). For on-target selection, the library was incubated with 425.5 nM immobilized, biotinylated FcγRIIA131H protein (10374-H27H1-B, Sino Biological). The coding sequences of the output DARPins were amplified and used as a template for the next selection round. In the fourth round, DARPins were first exposed to 17 pmol immobilized, biotinylated FcγRIIA131H protein and afterward to a 10-fold excess of unbiotinylated FcγRIIA131R protein (10374-H27H, Sino Biological) as off-rate selection. Finally, the fifth round was divided into two approaches: (i) DARPins were counterselected with 17 pmol FcγRIIB protein in solution before they were exposed to 17 pmol immobilized FcγRIIA131H protein and (ii) DARPins were first exposed to immobilized FcγRIIA131H protein and afterward counterselected with 170 pmol FcγRIIB protein in solution. After the fifth selection round, the output repertoire was cloned into E. coli XL1 Blue (Stratagene), and single clones were analyzed for FcγRIIA binding. A comparable number of DARPin candidates were obtained in both approaches.

Cloning, expression, and purification of DARPins

DARPin DNA fragments were subcloned into the bacterial expression plasmid pQE-HisHA, derived from pDST67 (30, 31), via SfiI and DraIII, and transferred into E. coli XL-1 blue bacteria (Stratagene). Single clones were randomly picked and expanded in 600 μl 2YT expression medium (2YT, 1% glucose, 100 mg/ml ampicillin) in 96-deep-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C. Next day, 100 μl overnight culture was used to inoculate 900 μl 2YT expression medium and for sequencing after DNA purification. After 1 h at 37 °C, protein expression was induced by adding 100 μl of 5.5 mM IPTG (Thermo Fischer Scientific) in 2YT medium to each well and subsequent incubation for 5 h (37 °C; 180 rpm). Cells were harvested by centrifugation and pellets stored at −80 °C. Thawed bacteria pellets were resuspended in 50 μl B-PER II (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated at room temperature for 2 h while lightly shaking. Four hundred fifty microliters Tris-buffered saline (TBS) was added per well, cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the crude extracts were stored at −80 °C in aliquots.

Large scale DARPin production was performed in E. coli XL-1 blue bacteria cultures of 100 to 600 ml volume. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 300 μM IPTG at an absorbance A600 of 0.6 to 0.7. After cultivation for 4 h at 37 °C, bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and pellets were stored at −80 °C. Pellets were thawed on ice and either resuspended in lysis buffer and disrupted by sonification for mechanical extraction or mixed with B-PERII (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for chemical extraction. Cell debris were removed by centrifugation. DARPins were purified by affinity chromatography either on Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose columns (Qiagen) or based on FPLC with HisTrap FF crude purification columns (Cytiva) according to the manufacturer. The elution fraction was dialyzed against PBS (pH 7.4) overnight at 4 °C. For storage, if necessary, DARPins were supplemented with 5% glycerol and the cOmplete ULTRA protease inhibitor (Roche).

The His-tag was cleaved off utilizing a TEV recognition site. For that, chromatographically purified DARPins were incubated with TEV protease (GenScript) at 4 °C overnight according to the supplier's information. The cleaved His-tag was then separated from the DARPin using either a second HisTrap column or by incubation with magnetic Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid beads. (New England Biolabs). DARPins were dialyzed against PBS overnight at 4 °C and if required, concentrated with Amicon Ultra-4 Centrifugal Filter Units (Merck).

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis

Samples were denatured in SDS containing buffer and reducing conditions at 95 °C for 10 min and loaded on 15% SDS-PAGE gels. After electrophoretic separation, gels were either washed in water and stained with GelCode Blue Safe Protein Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or semidry blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 10% horse serum in TBS-T (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.4) and afterward incubated with mouse anti-RGS-His-HRP (1:1000–2000; Qiagen) or mouse anti-HA (1:1000–2000; BioLegend) followed by rabbit anti-mouse-HRP (1:2000; DAKO; Agilent Technologies, Inc). For detection, ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used according to the manufacturers. All antibodies were diluted in 5% horse sera/TBS-T.

For identification of protein bands from stained gels, LC-MS was performed. Details on the experimental procedure including processing and database search parameters are described in the Supplementary material (Tables S2 and S3).

Flow cytometry with cell lines and blood cells

Cells were washed with FACS washing buffer (PBS, 2% FCS, 0.1% NaN3) before incubated with DARPin for 1 h at 4 °C in the dark. After two additional washing steps, cells were stained with anti-HA for DARPin detection as well as with other cell surface antibodies for 20 min at 4 °C in the dark. Before flow cytometry analysis, cells were washed again and resuspended in 100 μl FACS fixation buffer (PBS, 1% paraformaldehyde [PFA]).

Human PBMCs were isolated from the blood of healthy anonymous donors or from buffy coats purchased from the German Red Cross blood donation center (DRK Blutspendedienst Baden-Württemberg-Hessen), as described (32). All blood donations were from donors who had given informed consent in full agreement with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Isolation of Pan T cells from PBMC was performed with the human Pan T Cell Isolation Kit (Milteny Biotec) according to the manufacturer. For binding experiments, cells were thawed, washed, and used without activation.

Labeling of the DARPin was performed via preincubation with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-HA for at least 60 min at 4 °C in the dark before adding 1E6 cells PBMCs or isolated Pan T cells, followed by DARPin incubation for at least 80 min at 4 °C. After two additional washing steps, cells were stained with cell surface antibodies for 20 min at 4 °C in the dark. Before flow cytometry analysis, cells were washed again and resuspended in 100 μl FACS fixation buffer (PBS, 1% PFA).

For platelets, cells were first fixed in 1% PFA/Hepes buffered saline buffer for 3 min at 37 °C and washed with Hepes buffered saline (pH 7.4) before adding anti-CD41, anti-CD62P, mAb IV.3, or prelabeled DARPin to 106 platelets for 20 min at room temperature. Prelabeling of the DARPin was performed via incubation with PE-conjugated anti-HA antibody for at least 10 min at 4 °C in the dark. The data were acquired at the flow cytometer MACSQuant and analyzed using the FCS Express Software (DeNovo Software, Version 6.06, https://denovosoftware.com/full-access/download-landing/). Used antibody clones are listed in the Table S1.

Image stream analysis

For visualization by image cytometry, cell lines or cryopreserved PBMC samples were stained according to standard procedures. Briefly, cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended in 100 μl chilled buffer (PBS supplemented with 0.05% BSA) and incubated for 20 min at 4 °C in the dark with LIVE/DEAD fixable Near-IR cell dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific). DARPin or antibody staining against FcγRII was performed according to the preincubation procedure as described in the preceding section. Subsequently, cells were washed and surface stained with a mix of anti-human fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies, containing CD4 (RPA-T4), CD3 (UCHT1), CD19 (HIB19), and CD14 (PECy7) (all from BioLegend) for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark. After a final wash, samples were acquired on AMNIS imagestream X MkII Imaging cytometer (Luminex) at 40-fold magnification. Data analysis was performed with the IDEAS software version 6.2 (https://www.luminexcorp.com/eu/amnis-imagestream-imaging-flow-cytometer/#software).

Affinity determination by SPR measurement

The neutrAvidin NA chip (Cytiva) was prepared according to the manufacturer's protocol and immobilized with 100.5 RU human biotinylated FcγRIIA or 108.7 RU human biotinylated FcγRIIB protein, respectively. The running buffer was 20 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween20. DARPin samples were injected in 10-fold dilutions starting with 1.5 μM using a constant flow of 50 μl/min with an association period of 3 min followed by 15 min dissociation phase before regeneration with 10 mM NaOH. The kinetic data of the interaction was analyzed with the Biacore T200 (Cytiva, https://www.cytivalifesciences.com/en/us/support/software/biacore-downloads) at 25 °C, if not otherwise stated, whereby the signal of an uncoated reference flow cell was subtracted from the measurement and fitted using Biacore T200 evaluation software. Fitting based on the two-state model was performed with variable Rmax and constant RI = 0 as constrain. The curves were normalized, aligned to the onset of dissociation, and analyzed for binding behavior. To analyze the binding of F11-TEVcl and 2xF11 to the FcγRIIA variant H134R, 1733 RU of FcγRIIA134R protein was immobilized via the amine coupling kit (Cytiva) onto a CM5 chip (Cytiva). DARPin samples were injected with a constant flow of 30 μl/min with an association period of 260 s followed by 500 s dissociation phase before regeneration with 10 mM NaOH. The kinetic data of the interaction was analyzed with the Biacore T200 (Cytiva) at 25 °C, whereby the signal of an uncoated reference flow cell was subtracted.

Platelet separation and activation/inhibition assays

Peripheral blood was collected into citrate tubes (S-Monovette), incubated for 30 min at room temperature, centrifuged for 15 min at 150g, and the supernatant was used for platelet-rich plasma separation. Platelet concentrates were stored at room temperature under mild shaking. Successful platelet enrichment was confirmed by staining against CD41 which resulted in at least 96% positive cells. Platelet aggregation was measured by light transmission between 0% and 100% in an aggregometer (chrono-log series 490, Probe & go Labordiagnostica) at 37 °C while stirring. Stimulation of platelets (6.25e7 cells/250 μl) was induced with mAb IV.3 [2 ng/μl] for 3 min followed by cross-linking of FcγRII with goat anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2 [22.5 ng/μl] or by adding thrombin receptor activator peptide 6 (SFLLRN, Bachem) to a final concentration of 20 mM as aggregation control. Platelets were preincubated with DARPins at concentrations of 5 μM, 2.5 μM, or 1 μM for 10 min before starting stimulation. After performing the aggregation experiments, samples were centrifuged at 14,600 rpm for 4 min at room temperature and the supernatant was stored at −20 °C for later use in ELISA measurements. ELISA for detecting CCL5/RANTES (DY27, R&D Systems, Inc), CXCL7/NAP-2 (DY393; Bio-Techne), and soluble P-selectin/CD62P (DPSE00; Bio-Techne) was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol.

The HIPA assay with washed platelets was performed as described (33, 34, 35). The test result was considered to be positive if at least three of four donor platelets showed activation in the presence of a low (0.2 U/ml) but not a high (100 U/ml) heparin concentration. The anti-PF4 murine mAB KKO (75 μg/ml; Thermo Fisher Scientific) that causes platelet activation was tested in the presence of blocking mAb IV.3 (30 μg/ml) and F11 (148 μg/ml) after 30 min preincubation at 37 °C.

Washed platelets were preincubated with IV.3 or F11 in increasing concentrations (3.75 μg/ml, 7.5 μg/ml, 12.5 μg/ml, 25.0 μg/ml, 50.0 μg/ml, 75.0 μg/ml, and 100.0 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37 °C. CD62P expression was determined in a CytoFlex S flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) after stimulation with thrombin receptor activator peptide (20 μM; Bachem), collagen (8 μg/ml), or KKO (75 μg/ml) for 30 min at room temperature under shear stress (magnetic spheres at 400 rpm). Then, CD62P antibody was added for 10 min at room temperature and platelets were fixed with 0.5% PFA/PBS; pH 7.4. The rate of platelet activation was evaluated as the geometric mean fluorescence intensity of the gated platelet population. Alternatively, CD62P expression was measured directly after completed HIPA tests by transferring 25 μl of each sample to 96-well microtiter plates before proceeding as described above. Used antibody clones are listed in the Supplementary material (Table S1).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, https://www.graphpad.com/updates).

Data availability

All data are contained within the article.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information (36, 37, 38, 39, 40).

Conflict of interest

V. R., J. H., K. C., and C. J. B. are listed as inventors on a filed patent describing FcγRIIA-specific DARPins.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

V. R., S. H., M. V., M. Z., J. W., A. J., A. W., and A. R. investigation; V. R., S. A. T., J. H., E. H.-C., B. B., K. C., and C. J. B. methodology; V. R., P. A. A., A. O. P., and C. J. B. writing–original draft; J. W., A. G., and B. B. writing–review and editing; P. A. A. formal analysis; J. H., A. G., and C. J. B. supervision; E. H.-C., B. B., K. C., and C. J. B. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by grant 1R01AI145045-01 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to B. B., E. H.-C., and C. J. B. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by George M. Carman

Supporting information

References

- 1.Parren P.W., Warmerdam P.A., Boeije L.C., Arts J., Westerdaal N.A., Vlug A., et al. On the interaction of IgG subclasses with the low affinity Fc gamma RIIa (CD32) on human monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets. Analysis of a functional polymorphism to human IgG2. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;90:1537–1546. doi: 10.1172/JCI116022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel P., Michael J.V., Naik U.P., McKenzie S.E. Platelet FcγRIIA in immunity and thrombosis: adaptive immunothrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021;19:1149–1160. doi: 10.1111/jth.15265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arman M., Krauel K. Human platelet IgG Fc receptor FcγRIIA in immunity and thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2015;13:893–908. doi: 10.1111/jth.12905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baerenwaldt A., Lux A., Danzer H., Spriewald B.M., Ullrich E., Heidkamp G., et al. Fcγ receptor IIB (FcγRIIB) maintains humoral tolerance in the human immune system in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:18772–18777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111810108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips N.E., Parker D.C. Fc-dependent inhibition of mouse B cell activation by whole anti-mu antibodies. J. Immunol. 1983;130:602–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chauhan S., Ahmed Z., Bradfute S.B., Arko-Mensah J., Mandell M.A., Won Choi S., et al. Pharmaceutical screen identifies novel target processes for activation of autophagy with a broad translational potential. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8620. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Descours B., Petitjean G., López-Zaragoza J.-L., Bruel T., Raffel R., Psomas C., et al. CD32a is a marker of a CD4 T-cell HIV reservoir harbouring replication-competent proviruses. Nature. 2017;543:564–567. doi: 10.1038/nature21710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams P., Fievez V., Schober R., Amand M., Iserentant G., Rutsaert S., et al. CD32+CD4+ memory T cells are enriched for total HIV-1 DNA in tissues from humanized mice. iScience. 2021;24 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darcis G., Kootstra N.A., Hooibrink B., van Montfort T., Maurer I., Groen K., et al. CD32+CD4+ T cells are highly enriched for HIV DNA and can support transcriptional latency. Cell Rep. 2020;30:2284–2296.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.01.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badia R., Ballana E., Castellví M., García-Vidal E., Pujantell M., Clotet B., et al. CD32 expression is associated to T-cell activation and is not a marker of the HIV-1 reservoir. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2739. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05157-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornhill J.P., Pace M., Martin G.E., Hoare J., Peake S., Herrera C., et al. CD32 expressing doublets in HIV-infected gut-associated lymphoid tissue are associated with a T follicular helper cell phenotype. Mucosal Immunol. 2019;12:1212–1219. doi: 10.1038/s41385-019-0180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osuna C.E., Lim S.-Y., Kublin J.L., Apps R., Chen E., Mota T.M., et al. Evidence that CD32a does not mark the HIV-1 latent reservoir. Nature. 2018;561:E20–E28. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0495-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stumpp M.T., Dawson K.M., Binz H.K. Beyond antibodies: the DARPin® Drug platform. BioDrugs. 2020;34:423–433. doi: 10.1007/s40259-020-00429-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steiner D., Merz F.W., Sonderegger I., Gulotti-Georgieva M., Villemagne D., Phillips D.J., et al. Half-life extension using serum albumin-binding DARPin® domains. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2017;30:583–591. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzx022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zahnd C., Wyler E., Schwenk J.M., Steiner D., Lawrence M.C., McKern N.M., et al. A designed ankyrin repeat protein evolved to picomolar affinity to Her2. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;369:1015–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchholz C.J., Friedel T., Büning H. Surface-engineered viral vectors for selective and cell type-specific gene delivery. Trends. Biotechnol. 2015;33:777–790. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartmann J., Münch R.C., Freiling R.-T., Schneider I.C., Dreier B., Samukange W., et al. A library-based screening strategy for the identification of DARPins as ligands for receptor-targeted AAV and lentiviral vectors. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2018;10:128–143. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zellweger F., Gasser P., Brigger D., Buschor P., Vogel M., Eggel A. A novel bispecific DARPin targeting FcγRIIB and FcεRI-bound IgE inhibits allergic responses. Allergy. 2017;72:1174–1183. doi: 10.1111/all.13109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramsland P.A., Farrugia W., Bradford T.M., Sardjono C.T., Esparon S., Trist H.M., et al. Structural basis for Fc gammaRIIa recognition of human IgG and formation of inflammatory signaling complexes. J. Immunol. 2011;187:3208–3217. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerntke C., Nimmerjahn F., Biburger M. There is (scientific) strength in numbers: a comprehensive quantitation of Fc gamma receptor numbers on human and murine peripheral blood leukocytes. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:118. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Temming A.R., Bentlage A.E.H., de Taeye S.W., Bosman G.P., Lissenberg-Thunnissen S.N., Derksen N.I.L., et al. Cross-reactivity of mouse IgG subclasses to human Fc gamma receptors: antibody deglycosylation only eliminates IgG2b binding. Mol. Immunol. 2020;127:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2020.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiyoshi M., Caaveiro J.M.M., Kawai T., Tashiro S., Ide T., Asaoka Y., et al. Structural basis for binding of human IgG1 to its high-affinity human receptor FcγRI. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6866. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kremer P.G., Barb A.W. The weaker-binding Fc γ receptor IIIa F158 allotype retains sensitivity to N-glycan composition and exhibits a destabilized antibody-binding interface. J. Biol. Chem. 2022;298 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohn L.B., Chomont N., Deeks S.G. The biology of the HIV-1 latent reservoir and implications for cure strategies. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darcis G., Berkhout B., Pasternak A.O. The quest for cellular markers of HIV reservoirs: any color you like. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:2251. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neidleman J., Luo X., Frouard J., Xie G., Hsiao F., Ma T., et al. Phenotypic analysis of the unstimulated in vivo HIV CD4 T cell reservoir. Elife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.60933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Astorga-Gamaza A., Grau-Expósito J., Burgos J., Navarro J., Curran A., Planas B., et al. Identification of HIV-reservoir cells with reduced susceptibility to antibody-dependent immune response. Elife. 2022;11 doi: 10.7554/eLife.78294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frank A.M., Buchholz C.J. Surface-engineered lentiviral vectors for selective gene transfer into subtypes of lymphocytes. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2018;12:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greinacher A., Thiele T., Warkentin T.E., Weisser K., Kyrle P.A., Eichinger S. Thrombotic thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCov-19 vaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:2092–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huber T., Steiner D., Rothlisberger D., Plückthun A. In vitro selection and characterization of DARPins and Fab fragments for the co-crystallization of membrane proteins: the Na(+)-citrate symporter CitS as an example. J. Struct. Biol. 2007;159:206–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steiner D., Forrer P., Plückthun A. Efficient selection of DARPins with sub-nanomolar affinities using SRP phage display. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;382:1211–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jamali A., Kapitza L., Schaser T., Johnston I.C.D., Buchholz C.J., Hartmann J. Highly efficient and selective CAR-gene transfer using CD4- and CD8-targeted lentiviral vectors. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2019;13:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greinacher A., Michels I., Kiefel V., Mueller-Eckhardt C. A rapid and sensitive test for diagnosing heparin-associated thrombocytopenia. Thromb. Haemost. 1991;66:734–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savi P., Chong B.H., Greinacher A., Gruel Y., Kelton J.G., Warkentin T.E., et al. Effect of fondaparinux on platelet activation in the presence of heparin-dependent antibodies: a blinded comparative multicenter study with unfractionated heparin. Blood. 2005;105:139–144. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eichler P., Budde U., Haas S., Kroll H., Loreth R.M., Meyer O., et al. First workshop for detection of heparin-induced antibodies: validation of the heparin-induced platelet-activation test (HIPA) in comparison with a PF4/heparin ELISA. Thromb. Haemost. 1999;81:625–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva J.C., Denny R., Dorschel C., Gorenstein M.V., Li G.-Z., Richardson K., et al. Simultaneous qualitative and quantitative analysis of the Escherichia coli proteome: a sweet tale. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2006;5:589–607. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500321-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silva J.C., Gorenstein M.V., Li G.-Z., Vissers J.P.C., Geromanos S.J. Absolute quantification of proteins by LCMSE: a virtue of parallel MS acquisition. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2006;5:144–156. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500230-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shevchenko A., Tomas H., Havlis J., Olsen J.V., Mann M. In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:2856–2860. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spiric J., Engin A.M., Karas M., Reuter A. Quality control of biomedicinal allergen products - highly complex isoallergen composition challenges standard MS database search and requires manual data analyses. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wen J., Lord H., Knutson N., Wikström M. Nano differential scanning fluorimetry for comparability studies of therapeutic proteins. Anal. Biochem. 2020;593:113581. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2020.113581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article.