Abstract

Psychiatric comorbidity is the norm in the assessment and treatment of eating disorders (EDs), and traumatic events and lifetime PTSD are often major drivers of these challenging complexities. Given that trauma, PTSD, and psychiatric comorbidity significantly influence ED outcomes, it is imperative that these problems be appropriately addressed in ED practice guidelines. The presence of associated psychiatric comorbidity is noted in some but not all sets of existing guidelines, but they mostly do little to address the problem other than referring to independent guidelines for other disorders. This disconnect perpetuates a “silo effect,” in which each set of guidelines do not address the complexity of the other comorbidities. Although there are several published practice guidelines for the treatment of EDs, and likewise, there are several published practice guidelines for the treatment of PTSD, none of them specifically address ED + PTSD. The result is a lack of integration between ED and PTSD treatment providers, which often leads to fragmented, incomplete, uncoordinated and ineffective care of severely ill patients with ED + PTSD. This situation can inadvertently promote chronicity and multimorbidity and may be particularly relevant for patients treated in higher levels of care, where prevalence rates of concurrent PTSD reach as high as 50% with many more having subthreshold PTSD. Although there has been some progress in the recognition and treatment of ED + PTSD, recommendations for treating this common comorbidity remain undeveloped, particularly when there are other co-occurring psychiatric disorders, such as mood, anxiety, dissociative, substance use, impulse control, obsessive–compulsive, attention-deficit hyperactivity, and personality disorders, all of which may also be trauma-related. In this commentary, guidelines for assessing and treating patients with ED + PTSD and related comorbidity are critically reviewed. An integrated set of principles used in treatment planning of PTSD and trauma-related disorders is recommended in the context of intensive ED therapy. These principles and strategies are borrowed from several relevant evidence-based approaches. Evidence suggests that continuing with traditional single-disorder focused, sequential treatment models that do not prioritize integrated, trauma-focused treatment approaches are short-sighted and often inadvertently perpetuate this dangerous multimorbidity. Future ED practice guidelines would do well to address concurrent illness in more depth.

Keywords: eating disorders, trauma, PTSD, comorbidity, treatment, guidelines

Trauma, PTSD, and eating disorders

Scientific evidence for the association between trauma, PTSD and other trauma-related disorders in the predisposition, precipitation and perpetuation of eating disorders (EDs), has been established in a variety of samples, including treatment and non-treatment seeking individuals of various ages, genders and sexual orientations (1–6). The pooled lifetime prevalence rates of PTSD in EDs (ED + PTSD) in the highest quality studies average 25% with higher rates of 37–45% in bulimia nervosa (BN) and 21–26% in binge eating disorder (BED) (7–9). Lower prevalence rates are reported in association with AN, particularly the restricting type (10–14%). Nevertheless, higher rates of PTSD are reported in all ED patients admitted to residential care, especially those with BN, anorexia nervosa binge-purge type (AN-BP), and other specified feeding and eating disorders (OSFED) (2, 10, 11). Conversely, higher rates of EDs are also seen in patients with PTSD compared to the general population (8, 12).

It is common for ED + PTSD patients to report histories of multiple traumas and/or trauma types (1, 2, 10, 13). High trauma “doses” have been associated with ED severity and comorbidities (2, 13–16), and trauma histories and PTSD symptoms have been reported to predict more complicated courses of illness, higher dropout rates, and worse outcomes following treatment (11, 17–26). Evidence also suggests that individuals with ED + PTSD may be significantly more impulsive, prone to revictimization, and the subsequent perpetuation of PTSD (27–30), which apart from EDs tends to be a chronic disorder (31–33). Taken together, the development and adoption of integrated treatment approaches for ED + PTSD is warranted.

Existing ED guidelines lack a trauma-PTSD focus

Existing guidelines for the treatment of EDs do not adequately address the problem of psychiatric comorbidity, which is more common than not in this group of disorders. Although admittedly this is a complicated topic, previously published ED guidelines often mention the entire issue of psychiatric comorbidity in a rather cursory manner and, if mentioned at all, do not address the depth of discussion or nuance that is often necessary to address ED + PTSD. In the excellent 2017 review of 8 existing guidelines for AN by Hilbert and colleagues, only 3 of these 8 manuscripts mentioned psychiatric comorbidities, while 5 of 9 guidelines for BN noted comorbidities, usually as “special issues” (34).

The issue of trauma and specifically of PTSD in the assessment of EDs was noted in the Australian and New Zealand guideline. These experts noted that psychiatric comorbidity occurs as high as 55% in community adolescent samples and up to 96% in adult samples, and they state, “Comorbidity in people with anorexia nervosa is common and therefore assessment for such should be routine” (35). They also make the recommendation to “be prepared to treat comorbidity to improve quality of life,” although no specifics as to how to do this are offered other than using CBT-E, which does not directly address trauma or PTSD, and considering adjunctive pharmacotherapy (35).

The updated German guidelines for the treatment of AN specifically noted, “many patients are affected by comorbid psychological diseases,” and that comorbid conditions, such as PTSD, “might require changes in treatment planning and prioritization of therapy goals,” although no specifics were provided (36).

More recently the American Psychiatric Association published an updated practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders, which notes that “eating disorders frequently co-occur with other psychiatric disorders” (37, 38). The guideline states that “all patients with a possible eating disorder should be asked about a history of trauma … and assessed for symptoms related to PTSD.” Although “data are…limited on individuals with eating disorders and…co-occurring psychiatric disorders,” the guideline recommends that psychotherapy in adults with AN “address comorbid psychopathology, psychological conflicts, adaptive benefits of symptoms, and family or cultural factors that reinforce or maintain eating disorder behaviors,” suggestions which are certainly applicable to the treatment of ED + PTSD in patients with any type of ED.

Notably, none of the guidelines for adult patients with EDs that were reviewed for this commentary specifically addressed treatment of ED + PTSD per se. However, in the newly published Australian guideline for the treatment of ED patients at higher weights, much more attention to trauma, PTSD, and trauma-informed care is paid (39). This is relevant given that ED patients with PTSD treated in higher levels of care have been reported to have significantly higher BMIs (2, 10, 40). Importantly, Ralph and colleagues offer lived experience perspectives, and specifically discuss trauma-informed care within an ED context for patients in larger bodies. They also acknowledge how ED treatment itself may be traumatizing and how PTSD and other comorbidities occur “frequently” (39).

Three published guidelines were found for the treatment of children and adolescents with EDs (41–43). The focus on psychiatric comorbidity was most prominent in the guideline from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, which states “further complicating the diagnosis of AN is the potential presence of other significant psychiatric comorbid conditions” (43). Abuse is noted to be a potential risk factor for BN, and PTSD an associated comorbid disorder in BN and BED, but no specific treatment guidelines for ED + PTSD are provided other than to recommend that “guidelines for the specific condition should be followed” and “The use of medications, including complementary and alternative medications, should be reserved for comorbid conditions and refractory cases.” The Canadian guideline for children and adolescents with EDs only mentions trauma and PTSD in reference to ARFID (41). However, it notes in the very last line of the guidelines the following statement: “Research efforts should be devoted to developing treatments for severe eating disorders with complex comorbidity.”

Existing PTSD guidelines lack an eating disorder focus

Conversely, upon reviewing available practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of PTSD or complex PTSD, the treatment of EDs is never addressed (44–54). The only PTSD guidelines that specifically mention EDs as an associated comorbidity are those of the American Psychiatric Association (55). Several guidelines specifically note that the presence of comorbid disorders should not prevent patients from receiving trauma-focused treatments (51, 52, 54, 56). However, in my experience trauma specialists are often unprepared to deal with PTSD patients with active ED symptoms. Unfortunately, it has been a common but unfortunate occurrence for ED + PTSD patients to be refused treatment in either an ED specialty program or trauma specialty program, or if they are admitted, only the so-called “primary” disorder (for insurance purposes) is treated. The treatment of one disorder to the exclusion of the other is often inadequate in that it all too often results in poor outcomes.

Toward the development of treatment guidelines for ED + PTSD and related comorbidity

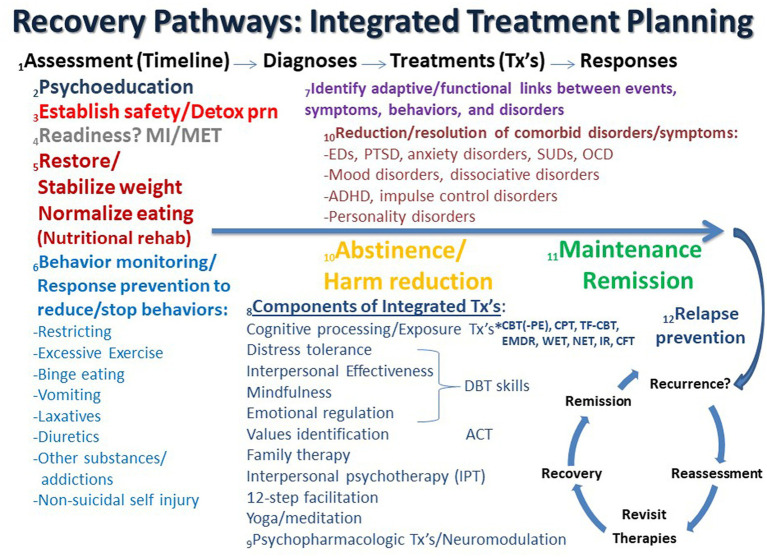

Recommendations regarding the treatment of ED + PTSD and related comorbidity have been previously outlined and discussed (1, 57, 58), and an updated, expanded conceptualization of these guidelines and principles is discussed here. Possible recovery pathways that may facilitate integrated treatment planning are shown in Figure 1. In the figure, the process starts on the left and proceeds in time to the right from Assessment (Timeline) to Diagnosis to Treatment (Tx) to Response as the patient ideally proceeds from highly symptomatic on the left to maintenance and/or remission on the far right, followed by relapse prevention and/or recurrence and reassessment.

Figure 1.

Recovery pathways that facilitate integrated treatment planning are discussed consecutively in the text as numbered. ACT, acceptance commitment therapy; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; CFT, compassion focused therapy; CPT, cognitive processing therapy; Detox, detoxification; DBT, dialectical behavior therapy; EMDR, eye movement desensitization reprocessing; IR, imaging rescripting; IPT, interpersonal psychotherapy; MI, motivational interviewing; MET, motivational enhancement therapy; NET, narrative exposure therapy; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; PE, prolonged exposure; SUD, substance use disorder; TF-CBT, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy; Tx’s, treatments; WET, written exposure therapy.

1. Assessment (Timeline) – Diagnosis: Most guidelines recognize the importance of “a comprehensive assessment of the individual and their circumstances” (35). It has been previously noted that “the most tried and true initial approach for any patient with or without complex symptomatology is to perform a complete psychiatric evaluation, which substantially reduces the chances of misdiagnosis” (57). This remains as important as ever, especially in an era in which time-limited evaluations are the norm in most treatment settings. Therefore, assessment is often an ongoing process that unfolds over several sessions. As part of this complete medical and psychiatric evaluation, the clinician and patient collaboratively develop a timeline that depicts the chronology of significant life events, traumas, symptom/disorder onsets, remissions, and relapses in the individual’s lifetime. Such a timeline can form the basis of the patient’s life narrative, including history of traumatic events and important contexts, and allows the patient and clinician to recognize and discuss predisposing, precipitating, perpetuating, and palliative factors in the patient’s life. Such an approach is compatible with the emerging paradigm of a life course approach as well as the concept of personalized medicine to address multimorbidity (59–63). It is important to note that the development of the patient’s historical timeline may occur over an extended period of time as therapy progresses and evolves (see #1 in Figure 1). Many ED patients do not feel comfortable revealing traumatic events during the initial assessment but need time to develop a trusting alliance with the therapist before such history is disclosed. The formation and maintenance of a therapeutic alliance remains a cornerstone of future work and progress (64, 65). Therapists need to convey a sense of safety, trust, honesty, straightforwardness, compassion, knowledge, and nonjudgmental positive regard, which are essential elements for any successful treatment course. Countertransference also needs to be closely monitored and contained (66–68). Cognitive processing therapy (CPT) emphasizes the importance of therapists avoiding avoidance of addressing traumatic material (69), as avoidance is highly characteristic of both EDs and PTSD (6, 11, 70–75). It has been previously noted that it is not uncommon for patients with ED + PTSD to not even realize that they have been victimized until the definitions of trauma and abuse types are explained to them (57). This is particularly relevant for patients with child maltreatment and complex PTSD. Only later after a substantial degree of cognitive development has occurred do some individuals realize the extent and meaning of their traumas.

2. Psychoeducation: As a comprehensive list of problems and conditions is being determined, the clinician moves forward educating the patient and supportive family about all diagnosed disorders, both current and lifetime. Psychoeducation is the cornerstone of all modern therapies, especially cognitive-behavioral and trauma-focused approaches (see #2 in Figure 1). Psychiatric disorders often vacillate in and out of remission, and previous disorders may serve as important predisposing factors for subsequent symptoms and disorders. Notably, comorbidity is the rule rather than the exception in PTSD and EDs (57, 76–78), and comorbid disorders are generally not contraindications to trauma-focused treatments (79, 80). Such treatments can be safely and effectively used in patients with a range of psychiatric disorders and are often associated with concurrent decreases in PTSD and the comorbid problem(s) (80–83).

3. Safety and stability: The most important determination and goal early on in treatment is to initially assess and address the greatest danger or risk to life, e.g., suicidality, self-harming behaviors, starvation, fluid/electrolyte disturbances, cardiac arrhythmia, etc. (see #3 in Figure 1). Attaining relative safety and stability is the foundation of stage 1 treatment of PTSD with complex presentations (complex PTSD), as well as dissociative disorders, which are highly linked to developmental traumas (46, 84–87). Given its pervasive association with problems in self-regulation, ED + PTSD with related comorbidities may be conceptualized as forms of complex PTSD (1, 88–90). Emerging behaviors that derail treatment progress, or therapy interfering behaviors (91–93), may need to be addressed as the therapist assists the patient to identify avoidance and work on stuck-points, cognitive distortions, or maladaptive beliefs (69). However, some trauma experts question the need for a phasic approach, arguing that there is a lack of research to support several contentions, including that: (1) a phase-based approach is necessary to attain positive outcomes, (2) trauma-focused treatments have unacceptable risks, and (3) response to trauma-focused treatments are improved when preceded by a stabilization phase (94). On the other hand, ISTSS guidelines indicate sufficient evidence and clinical rationale to support the phase-oriented approach with an initial period of stabilization and establishment of safety (46, 84, 95). Suicidality and other immediately life-threatening medical conditions are effectively the major primary contraindications against initiating trauma-focused treatment (79). When a substance use disorder (SUD) complicates the clinical picture, a detox strategy that is appropriate for the particular substance is an important early treatment component that is subsumed under the goal of establishing safety and stability.

4. Readiness for change: As assessment and treatment move forward, it is incumbent on therapists to identify readiness for change and willingness to engage in both PTSD and ED recovery, which are intimately interwoven (96–100). Motivational interviewing (MI) and motivation enhancement therapy (MET) approaches may help to identify the most problematic condition per the patient’s perspective and can be important prequels and/or adjuncts to other subsequent evidence-based therapies for EDs, PTSD and related comorbidities (101–108) (see #4 in Figure 1). However, it is notable that readiness for trauma-focused treatment is not always accurately assessed by therapists, which can lead to inadvertent collusion with avoidance (101).

5. Nutritional rehabilitation: Early on in treatment it is essential to establish that the patient has begun the process of nutritional rehabilitation, is more adherent to this plan than not (progress not perfection), is medically stable, and can begin to process information emotionally and cognitively (see #5 in Figure 1). New learning is dependent upon adequate food intake and subsequent protein and neurotransmitter synthesis (109–111). Ideally, effective psychotherapy requires grossly intact brain function, the ability to attend to the process at hand, and the ability and motivation to learn new information (and unlearn maladaptive strategies). Starved, intoxicated and/or severely dysregulated brains are unable to learn well and therefore are less likely to benefit from psychotherapy. Nevertheless, trauma-focused treatment should not be delayed until full weight restoration or remission of ED behaviors is achieved as long as the patient is safe and willing to engage in trauma processing. Evidence has been accumulating that the long-term resolution of ED symptoms may in fact hinge on trauma-focused treatment (4, 77, 112, 113).

6. Behavior monitoring and response prevention: Just as psychoeducation is an integral early component of cognitive behavioral therapies, so too is behavior monitoring and response prevention of problematic behaviors. Patients are asked to record instances and frequencies of targeted behaviors, including food intake and episodes of binge eating, purging, excessive exercise, substance use, and non-suicidal self-injury. This prescription is not only a part of ongoing assessment but is an effective treatment intervention in itself (see #6 in Figure 1). As treatment continues, the therapist periodically confirms that ED behaviors are being sufficiently addressed in an ongoing manner. Monitoring of ED and PTSD symptoms using validated measures, e.g., the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDEQ) (114) and the PTSD Symptom Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (115), respectively, are essential in assessing progress for the ED + PTSD patient, while an array of other assessments are available for other comorbidities. While full remission may remain elusive, it is helpful to frame various degrees of symptom improvement as evidence of progress and success. Combating perfectionistic, “all or nothing” thinking is often an ongoing process in the long-term treatment of ED + PTSD patients, and teaching and promoting the concept and goal of harm reduction is a useful endeavor that has application to multiple symptoms and disorders on the comorbidity spectrum (116–118).

7. Adaptive function: An important part of the therapeutic process is to collaboratively identify the relationships between life events, symptoms of PTSD, eating and other disorders, which may serve as adaptive functions, such as to facilitate avoidance and numbing, decrease hyperarousal, regulate trauma-related states (“self-medication hypothesis”) (119) or solve some perceived problem(s) (15). Certain ED behaviors may also be traumatic reenactments (120). “Building the bridge” between trauma-related/PTSD symptoms and ED behaviors/symptoms serves to foster new connections and meanings and paves the way toward sustained recovery (see #7 in Figure 1). Continued work on the patient’s timeline can facilitate ascertaining these connections. Establishing the interconnectedness of and bridging between symptoms is supported by recent network analyses of ED and PTSD symptoms (97, 99, 100).

8. Components of integrated treatment: psychotherapies: It is argued that an integrated trauma-focused treatment plan using a rational mixture of evidence-based techniques and tools is indicated. An overview of the psychotherapeutic components that may be considered in integrated treatment planning is shown in Figure 1 (see #8). The field has evolved beyond the “one size fits all” approach, which is woefully inadequate for the ED + PTSD patient. Generally, some form of trauma-focused treatment is indicated for PTSD, and this should be no different when there is ED comorbidity. The most researched of trauma-focuses approaches in this population is cognitive processing therapy (CPT), which arguably is very well-suited for ED + PTSD patients (29, 112, 113, 121–123). However, other trauma-focused therapies can be applied to ED + PTSD patients, including prolonged exposure (PE), eye movement desensitization reprocessing (EMDR), imaging rescripting (IR), written exposure therapy (WET), narrative exposure therapy (NET), compassion-focused therapy (CFT), and trauma-focused CBT (TFCBT) in children and adolescents (49, 71, 121, 124–142). Other adjunctive approaches, or elements of these approaches, can also be useful, including acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which identifies values and addresses experiential avoidance (143–146), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), which has been reported to be effective in EDs, PTSD, and major depression (145, 147–152), and 12-step facilitation, a manual based, therapist driven treatment based on 12-step principles found to be effective for alcohol use and stimulant use disorders (153–155). The unified treatment model has also been recommended for ED + PTSD (156). Self-administered emotional freedom techniques (EFT) have been successfully employed for PTSD, but have not been systematically explored in EDs (157). Family therapy with non-offending parents and/or guardians is an essential ingredient for children and adolescents with ED and PTSD, and it should be considered for all patients of any age (158, 159). Involving family members in assessment and treatment is often extremely helpful and can contribute to significant therapeutic advances. When patients are not amenable to involving family members it is important for therapists to understand why.

A sufficient level of distress tolerance and emotional regulation is required so that psychotherapy can proceed, although pauses and delays are likely to occur in the course of addressing patients with complex psychopathology. The use of DBT skills as grounding techniques to enhance self-regulation, mindfulness, distress tolerance and interpersonal effectiveness can be essential, powerful adjuncts to trauma-focused therapies for severely ill comorbid ED + PTSD patients (160, 161). Other grounding or anxiety reduction techniques, such as focused breathing, yoga and other meditation practices, can be utilized as evidence-based treatment adjuncts (162–172). However, a certain amount of emotionality is to be expected and should not in itself be a reason for delay. A central tenet of evidence-based trauma-focused treatment is for the therapist to “avoid avoidance” and to not collude with the patient’s tendency to deflect (69). Disengagement coping has been found to predict revictimization, while engagement coping predicts better outcomes (173).

9. Components of integrated treatment: psychopharmacology and neuromodulation: Psychopharmacological interventions are also effective evidence-based treatments for non-comorbid EDs, PTSD and related comorbid disorders, e.g., mood and anxiety disorders, but they should always be adjunctive to psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with ED + PTSD and related comorbidities (174–179) (see #9 in Figure 1). The agents that have been found to be beneficial in ED and PTSD samples separately generally include antidepressants, especially fluoxetine and other serotonin reuptake inhibitors, atypical antipsychotics, especially olanzapine, and anticonvulsants, especially topiramate (35, 180–199). In addition, naltrexone can be highly effective in reducing alcohol intake as well as combating non-suicidal self-injury and binge eating (200–210). Other novel approaches to consider, especially when treatment-refractory major depression is a focus, may include the use of newer psychopharmacologic agents, e.g., 5-HT4 receptor antagonists (211), combining other previously unused evidence-based psychotherapies and psychopharmacologic approaches (142, 212), adjunctive application of neuromodulation tools, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) (213, 214), deep TMS (215) or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) (216), novel psychotropic-or psychedelic-assisted therapies, such as ketamine/esketamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), psilocybin, and ayahuasca (12, 28, 212, 217–231), as well as deep brain stimulation (DBS) (232–235), although many of these newer approaches continue to be preliminary, experimental and/or challenging to acquire.

10. Resolution, abstinence, and harm reduction: It is well known that improvement in one set of symptoms often results in the resolution of or improvement in related symptoms of other disorders, which exist in a network with each other (see #10 in Figure 1) (147, 236–238). For example, as ED symptoms abate with treatment so also can symptoms of disorders of mood, anxiety, personality, etc. (11, 112, 122, 239, 240). Similarly, abstinence from or a reduction in SUD behaviors often accompanies similar reductions in mood, anxiety and other comorbid symptoms (241, 242). Likewise, recovery from PTSD often results in improvements in a host of related psychological symptoms (243–245).

11. Maintenance, remission, and relapse prevention: As improvements continue and degrees of remission are achieved, patients may move into the maintenance phase of treatment (see #11 in Figure 1). It is during this phase that relapse prevention strategies can be successfully employed. Specific forms of CBT and pharmacotherapy focused on relapse prevention have been found to significantly reduce relapse for eating, substance use, mood and anxiety disorders (246–255).

12. Refractoriness and relapse: In the face of refractoriness to treatment, inadequate response, and/or relapse, which is common in EDs and related comorbidities (256–258), it is helpful for the patient and therapist to re-evaluate the treatment plan, identify triggers, stuck points, and potential weak points, and to revisit therapeutic options (see #12 in Figure 1). Experienced clinicians are familiar with the “whack-a-mole” phenomenon in which one or more problems resolve as others emerge. When the therapeutic skills of the therapist do not match the needs of the patient, then it is sometimes appropriate and in the best interests of the patient to discuss switching gears and referring to someone else with greater expertise, experience or skills. However, it is essential that hope continue to live eternal while the odds of attaining desired goals are evaluated. The lived experiences of patients with ED + PTSD, particularly those with severe and enduring eating disorders, should be carefully considered in light of what is and is not known about long-term outcome data (259–270). Despite the availability in some locations of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide for so-called “terminal anorexia,” it is my and others’ opinion that this course of action not be considered a possible option (263, 271–273), while palliative care may be indicated and considered (274). There are so many potential therapeutic options and combinations of options that one is hard pressed to argue that all avenues have been exhausted in the face of ED + PTSD chronicity and refractoriness.

In conclusion, effective treatment of ED + PTSD and related comorbidity requires the therapist to acquire many needed skills and resources, many of which are outlined in Figure 1 and discussed in this commentary. Abraham Maslow once said, “If all you have is a nail, then everything is a hammer.” Applying only one therapeutic approach to every ED patient is insufficient, a conclusion that is hopefully obvious at this juncture. Available clinical research evidence suggests that continuing with traditional single-disorder focused, sequential treatment models with multiple providers that do not prioritize integrated, trauma-focused treatment approaches are short-sighted and often inadvertently perpetuate this dangerous multimorbidity. Future ED practice guidelines would do well to address concurrent illness in more depth. Taken together, these principles offer the clinician a map for better negotiating a successful journey of recovery for the ED + PTSD comorbid patient. Recently published outcome data indicate that integrated treatment approaches can result in significant improvement in ED, PTSD and related symptoms (11, 12, 112, 122, 127, 156).

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

TB is the owner of Timothy D. Brewerton, MD, LLC.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Brewerton TD. An overview of trauma-informed care and practice for eating disorders. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. (2018) 28:445–62. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2018.1532940 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brewerton TD, Perlman MM, Gavidia I, Suro G, Genet J, Bunnell DW. The association of traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder with greater eating disorder and comorbid symptom severity in residential eating disorder treatment centers. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:2061–6. doi: 10.1002/eat.23401, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brewerton TD, Suro G, Gavidia I, Perlman MM. Sexual and gender minority individuals report higher rates of lifetime traumas and current PTSD than cisgender heterosexual individuals admitted to residential eating disorder treatment. Eat Weight Disord. (2022) 27:813–20. doi: 10.1007/s40519-021-01222-4, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell KS, Scioli ER, Galovski T, Belfer PL, Cooper Z. Posttraumatic stress disorder and eating disorders: maintaining mechanisms and treatment targets. Eat Disord. (2021) 29:292–306. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2020.1869369, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reyes-Rodriguez ML, Von Holle A, Ulman TF, Thornton LM, Klump KL, Brandt H, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in anorexia nervosa. Psychosom Med. (2011) 73:491–7. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31822232bb, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scharff A, Ortiz SN, Forrest LN, Smith AR. Comparing the clinical presentation of eating disorder patients with and without trauma history and/or comorbid PTSD. Eat Disord. (2019) 29:88–102. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2019.1642035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dansky BS, Brewerton TD, Kilpatrick DG, O'Neil PM. The National Women's study: relationship of victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder to bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. (1997) 21:213–28. doi: , PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrell EL, Russin SE, Flint DD. Prevalence estimates of comorbid eating disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative synthesis. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. (2020) 31:264–82. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2020.1832168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. (2007) 61:348–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brewerton TD, Gavidia I, Suro G, Perlman MM, Genet J, Bunnell DW. Provisional posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with greater severity of eating disorder and comorbid symptoms in adolescents treated in residential care. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2021) 29:910–23. doi: 10.1002/erv.2864, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scharff A, Ortiz SN, Forrest LN, Smith AR, Boswell JF. Post-traumatic stress disorder as a moderator of transdiagnostic, residential eating disorder treatment outcome trajectory. J Clin Psychol. (2021) 77:986–1003. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23106, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brewerton TD, Wang JB, Lafrance A, Pamplin C, Mithoefer M, Yazar-Klosinki B, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy significantly reduces eating disorder symptoms in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of adults with severe PTSD. J Psychiatr Res. (2022) 149:128–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.03.008, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brewerton TD, Perlman MM, Gavidia I, Suro G, Jahraus J. Headache, eating disorders, PTSD, and comorbidity: implications for assessment and treatment. Eat Weight Disord. (2022) 27:2693–700. doi: 10.1007/s40519-022-01414-6, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afifi TO, Sareen J, Fortier J, Taillieu T, Turner S, Cheung K, et al. Child maltreatment and eating disorders among men and women in adulthood: results from a nationally representative United States sample. Int J Eat Disord. (2017) 50:1281–96. doi: 10.1002/eat.22783, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brewerton T. D., Dennis A. B. (2015). Perpetuating factors in severe and enduring anorexia nervosa. In Touyz S., Hay P., Grange D., Lacey J. H. (Eds.), Managing severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: a clinician's handbook. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molendijk ML, Hoek HW, Brewerton TD, Elzinga BM. Childhood maltreatment and eating disorder pathology: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Psychol Med. (2017) 47:1402–16. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716003561, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson KP, LaPorte DJ, Brandt H, Crawford S. Sexual abuse and bulimia: response to inpatient treatment and preliminary outcome. J Psychiatr Res. (1997) 31:621–33. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3956(97)00026-5, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castellini G, Lelli L, Cassioli E, Ciampi E, Zamponi F, Campone B, et al. Different outcomes, psychopathological features, and comorbidities in patients with eating disorders reporting childhood abuse: a 3-year follow-up study. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2018) 26:217–29. doi: 10.1002/erv.2586, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Convertino A. D., Mendoza R. R. (2023). Posttraumatic stress disorder, traumatic events, and longitudinal eating disorder treatment outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord doi: 10.1002/eat.23933 [Epub ahead of print], PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Fallon BA, Sadik C, Saoud JB, Garfinkel RS. Childhood abuse, family environment, and outcome in bulimia nervosa. J Clin Psychiatry. (1994) 55:424–8. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazzard VM, Crosby RD, Crow SJ, Engel SG, Schaefer LM, Brewerton TD, et al. Treatment outcomes of psychotherapy for binge-eating disorder in a randomized controlled trial: examining the roles of childhood abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2021) 29:611–21. doi: 10.1002/erv.2823, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahon J, Bradley SN, Harvey PK, Winston AP, Palmer RL. Childhood trauma has dose effect relationship with dropping out from psychotherapeutic treatment for bulimia nervosa: a replication. Int J Eat Disord. (2001) 30:138–48. doi: 10.1002/eat.1066, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez M, Perez V, Garcia Y. Impact of traumatic experiences and violent acts upon response to treatment of a sample of Colombian women with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. (2005) 37:299–306. doi: 10.1002/eat.20091, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serra R, Kiekens G, Tarsitani L, Vrieze E, Bruffaerts R, Loriedo C, et al. The effect of trauma and dissociation on the outcome of cognitive behavioural therapy for binge eating disorder: a 6-month prospective study. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2020) 28:309–17. doi: 10.1002/erv.2722, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trottier K. Posttraumatic stress disorder predicts non-completion of day hospital treatment for bulimia nervosa and other specified feeding/eating disorder. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2020) 28:343–50. doi: 10.1002/erv.2723, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vrabel KR, Hoffart A, Ro O, Martinsen EW, Rosenvinge JH. Co-occurrence of avoidant personality disorder and child sexual abuse predicts poor outcome in long-standing eating disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. (2010) 119:623–9. doi: 10.1037/a0019857, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brewerton TD, Cotton BD, Kilpatrick DG. Sensation seeking, binge-type eating disorders, victimization, and PTSD in the National Women's study. Eat Behav. (2018) 30:120–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.07.001, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell JM, Bogenschutz M, Lilienstein A, Harrison C, Kleiman S, Parker-Guilbert K, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nat Med. (2021) 27:1025–33. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01336-3, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell KS, Wells SY, Mendes A, Resick PA. Treatment improves symptoms shared by PTSD and disordered eating. J Trauma Stress. (2012) 25:535–42. doi: 10.1002/jts.21737, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vierling V, Etori S, Valenti L, Lesage M, Pigeyre M, Dodin V, et al. Prevalence and impact of post-traumatic stress disorder in a disordered eating population sample. Presse Med. (2015) 44:e341–52. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2015.04.039, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Benjet C, Bromet EJ, Cardoso G, et al. Trauma and PTSD in the WHO world mental health surveys. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2017) 8:1353383. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1995) 52:1048–60. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koenen KC, Ratanatharathorn A, Ng L, McLaughlin KA, Bromet EJ, Stein DJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health surveys. Psychol Med. (2017) 47:2260–74. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000708, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilbert A, Hoek HW, Schmidt R. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for eating disorders: international comparison. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2017) 30:423–37. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000360, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hay P, Chinn D, Forbes D, Madden S, Newton R, Sugenor L, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2014) 48:977–1008. doi: 10.1177/0004867414555814, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Resmark G, Herpertz S, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Zeeck A. Treatment of anorexia nervosa-new evidence-based guidelines. J Clin Med. (2019) 8:153. doi: 10.3390/jcm8020153, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Psychiatric Association (2023). The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

- 38.Crone C, Fochtmann LJ, Attia E, Boland R, Escobar J, Fornari V, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry. (2023) 180:167–71. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.23180001, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ralph AF, Brennan L, Byrne S, Caldwell B, Farmer J, Hart LM, et al. Management of eating disorders for people with higher weight: clinical practice guideline. J Eat Disord. (2022) 10:121. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00622-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Longo P, Marzola E, De Bacco C, Demarchi M, Abbate-Daga G. Young patients with anorexia nervosa: the contribution of post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic events. Medicina. (2020) 34:665–74. doi: 10.3390/medicina57010002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Couturier J, Isserlin L, Norris M, Spettigue W, Brouwers M, Kimber M, et al. Canadian practice guidelines for the treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Eat Disord. (2020) 8:4. doi: 10.1186/s40337-020-0277-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ebeling H, Tapanainen P, Joutsenoja A, Koskinen M, Morin-Papunen L, Jarvi L, et al. A practice guideline for treatment of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Ann Med. (2003) 35:488–501. doi: 10.1080/07853890310000727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lock J, La Via MC, American Academy of, C., & Adolescent Psychiatry Committee on Quality, I . Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2015) 54:412–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berliner L., Bisson J., Cloitre M., Forbes D., Goldbeck L., Jensen T. K., et al. (2017). ISTSS guidelines position paper on complex PTSD in children and adolescents, Oakbrook Terrace, IL: International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies.

- 45.Bisson JI, Berliner L, Cloitre M, Forbes D, Jensen TK, Lewis C, et al. The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies new Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: methodology and development process. J Trauma Stress. (2019) 32:475–83. doi: 10.1002/jts.22421, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cloitre M., Courtois C. A., Ford J. D., Green B. L., Alexander P., Briere J., et al. (2012). ISTSS expert consensus guidelines for complex PTSD, Oakbrook Terrace, IL: International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies.

- 47.Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA. Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Second ed New York, NY: The Guilford Press; (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forbes D, Creamer M, Bisson JI, Cohen JA, Crow BE, Foa EB, et al. A guide to guidelines for the treatment of PTSD and related conditions. J Trauma Stress. (2010) 23:537–52. doi: 10.1002/jts.20565, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of PTSD in Adults, A. P. A . Summary of the clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Am Psychol. (2019) 74:596–607. doi: 10.1037/amp0000473, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis C, Roberts NP, Andrew M, Starling E, Bisson JI. Psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2020) 11:1729633. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1729633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . (2018). Guideline for posttraumatic stress disorder. National Institute for Health and Clinical Practice.

- 52.Phelps AJ, Lethbridge R, Brennan S, Bryant RA, Burns P, Cooper JA, et al. Australian guidelines for the prevention and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: updates in the third edition. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2022) 56:230–47. doi: 10.1177/00048674211041917, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.The Expert Concensus Panels for PTSD . The expert consensus guideline series. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder PTSD. J Clin Psychiatry. (1999) 60:3–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.The Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Work Group . (2017). VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of post-traumatic stress and acute stress disorder. department of veterans affairs, department of defense. Available at: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal082917.pdf [Accessed January 18]

- 55.Ursano RJ, Bell C, Eth S, Friedman M, Norwood A, Pfefferbaum B, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. (2004) 161:3–31. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamblen JL, Norman SB, Sonis JH, Phelps AJ, Bisson JI, Nunes VD, et al. A guide to guidelines for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: An update. Psychotherapy. (2019) 56:359–73. doi: 10.1037/pst0000231, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brewerton TD. Eating disorders, victimization, and comorbidity: principles of treatment In: Brewerton TD, editor. Clinical handbook of eating disorders: an integrated approach: New York, NY: Marcel Decker; (2004). 509–45. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trim JG, Galovski T, Wagner A, Brewerton TD. Treating eating disorder-PTSD patients: a synthesis of the literature and new treatment directions In: Anderson LK, Murray SB, Kaye WH, editors. Clinical handbook of complex and atypical eating disorders: New York, NY: Oxford University Press; (2017). 40–59. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. (2002) 31:285–93. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.2.285, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fried EI, Cramer AOJ. Moving forward: challenges and directions for psychopathological network theory and methodology. Perspect Psychol Sci. (2017) 12:999–1020. doi: 10.1177/1745691617705892, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fried EI, van Borkulo CD, Cramer AO, Boschloo L, Schoevers RA, Borsboom D. Mental disorders as networks of problems: a review of recent insights. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2017) 52:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1319-z, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kan C, Treasure J. Recent research and personalized treatment of anorexia nervosa. Psychiatr Clin North Am. (2019) 42:11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2018.10.010, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, Power C. Life course epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2003) 57:778–83. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.778, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olofsson ME, Oddli HW, Hoffart A, Eielsen HP, Vrabel KR. Change processes related to long-term outcomes in eating disorders with childhood trauma: An explorative qualitative study. J Couns Psychol. (2020) 67:51–65. doi: 10.1037/cou0000375, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olofsson ME, Vrabel KR, Hoffart A, Oddli HW. Covert therapeutic micro-processes in non-recovered eating disorders with childhood trauma: an interpersonal process recall study. J Eat Disord. (2022) 10:42. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00566-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cramer MA. Under the influence of unconscious process: countertransference in the treatment of PTSD and substance abuse in women. Am J Psychother. (2002) 56:194–210. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2002.56.2.194, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Satir DA, Thompson-Brenner H, Boisseau CL, Crisafulli MA. Countertransference reactions to adolescents with eating disorders: relationships to clinician and patient factors. Int J Eat Disord. (2009) 42:511–21. doi: 10.1002/eat.20650, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thompson-Brenner H, Satir DA, Franko DL, Herzog DB. Clinician reactions to patients with eating disorders: a review of the literature. Psychiatr Serv. (2012) 63:73–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100050, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Resick PA, Monson CM, Chard KM. Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD: A comprehensive manual, New York, NY: The Guilford Press; (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cavicchioli M, Scalabrini A, Northoff G, Mucci C, Ogliari A, Maffei C. Dissociation and emotion regulation strategies: a meta-analytic review. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 143:370–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.011, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Daneshvar S, Shafiei M, Basharpoor S. Group-based compassion-focused therapy on experiential avoidance, meaning-in-life, and sense of coherence in female survivors of intimate partner violence with PTSD: a randomized controlled trial. J Interpers Viol. (2022) 37:NP4187–211. doi: 10.1177/0886260520958660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Della Longa NM, De Young KP. Experiential avoidance, eating expectancies, and binge eating: a preliminary test of an adaption of the acquired preparedness model of eating disorder risk. Appetite. (2018) 120:423–30. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.09.022, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fulton JJ, Lavender JM, Tull MT, Klein AS, Muehlenkamp JJ, Gratz KL. The relationship between anxiety sensitivity and disordered eating: the mediating role of experiential avoidance. Eat Behav. (2012) 13:166–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.12.003, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oldershaw A, Lavender T, Sallis H, Stahl D, Schmidt U. Emotion generation and regulation in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of self-report data. Clin Psychol Rev. (2015) 39:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.04.005, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wooldridge JS, Herbert MS, Dochat C, Afari N. Understanding relationships between posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, binge-eating symptoms, and obesity-related quality of life: the role of experiential avoidance. Eat Disord. (2021) 29:260–75. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2020.1868062, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brady KT, Killeen TK, Brewerton T, Lucerini S. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. (2000) 61:22–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brewerton TD. Eating disorders, trauma, and comorbidity: focus on PTSD. Eat Disord. (2007) 15:285–304. doi: 10.1080/10640260701454311, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hambleton A, Pepin G, Le A, Maloney D, National Eating Disorder Research, C. Touyz S, et al. Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of eating disorders: findings from a rapid review of the literature. J Eat Disord. (2022) 10:132. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00654-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goodnight JRM, Ragsdale KA, Rauch SAM, Rothbaum BO. Psychotherapy for PTSD: An evidence-based guide to a theranostic approach to treatment. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2019) 88:418–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.05.006, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van Minnen A, Harned MS, Zoellner L, Mills K. Examining potential contraindications for prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2012) 2012:3. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.18805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mills KL, Teesson M, Back SE, Brady KT, Baker AL, Hopwood S, et al. Integrated exposure-based therapy for co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and substance dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. (2012) 308:690–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9071, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ronconi JM, Shiner B, Watts BV. Inclusion and exclusion criteria in randomized controlled trials of psychotherapy for PTSD. J Psychiatr Pract. (2014) 20:25–37. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000442936.23457.5b, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ruglass LM, Lopez-Castro T, Papini S, Killeen T, Back SE, Hien DA. Concurrent treatment with prolonged exposure for co-occurring full or subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorders: a randomized clinical trial. Psychother Psychosom. (2017) 86:150–61. doi: 10.1159/000462977, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cloitre M, Courtois CA, Charuvastra A, Carapezza R, Stolbach BC, Green BL. Treatment of complex PTSD: results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. J Trauma Stress. (2011) 24:615–27. doi: 10.1002/jts.20697, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cloitre M, Petkova E, Wang J, Lu Lassell F. An examination of the influence of a sequential treatment on the course and impact of dissociation among women with PTSD related to childhood abuse. Depress Anxiety. (2012) 29:709–17. doi: 10.1002/da.21920, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cloitre M, Stovall-McClough KC, Nooner K, Zorbas P, Cherry S, Jackson CL, et al. Treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. (2010) 167:915–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081247, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.ISSTD . Guidelines for treating dissociative identity disorder in adults, third revision. J Trauma Dissociation. (2011) 12:115–87. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2011.537247, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dagan Y, Yager J. Severe bupropion XR abuse in a patient with long-standing bulimia nervosa and complex PTSD. Int J Eat Disord. (2018) 51:1207–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.22948, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rorty M, Yager J. Histories of childhood trauma and complex post-traumatic sequelae in women with eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. (1996) 19:773–91. doi: 10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70381-6, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Van der Kolk BA. Assessment and treatment of complex PTSD In: Yehuda R, editor. Treating trauma survivors with PTSD (pp. 127–156): Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; (2002) [Google Scholar]

- 91.Davis ML, Fletcher T, McIngvale E, Cepeda SL, Schneider SC, La Buissonniere Ariza V, et al. Clinicians' perspectives of interfering behaviors in the treatment of anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders in adults and children. Cogn Behav Ther. (2020) 49:81–96. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2019.1579857, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Federici A, Wisniewski L. An intensive DBT program for patients with multidiagnostic eating disorder presentations: a case series analysis. Int J Eat Disord. (2013) 46:322–31. doi: 10.1002/eat.22112, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Federici A, Wisniewski L, Ben-Porath D. Description of an intensive dialectical behavior therapy program for multidiagnostic clients with eating disorders. J Couns Dev. (2012) 90:330–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2012.00041.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.De Jongh A, Resick PA, Zoellner LA, van Minnen A, Lee CW, Monson CM, et al. Critical analysis of the current treatment guidelines for complex PTSD in adults. Depress Anxiety. (2016) 33:359–69. doi: 10.1002/da.22469, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cloitre M. Commentary on De Jongh Et Al. (2016) Critique of Istss complex Ptsd guidelines: finding the way forward. Depress Anxiety. (2016) 33:355–6. doi: 10.1002/da.22493, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brewerton TD. Mechanisms by which adverse childhood experiences, other traumas and PTSD influence the health and well-being of individuals with eating disorders throughout the life span. J Eat Disord. (2022) 10:162. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00696-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liebman RE, Becker KR, Smith KE, Cao L, Keshishian AC, Crosby RD, et al. Network analysis of posttraumatic stress and eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of adults exposed to childhood abuse. J Trauma Stress. (2020) 34:665–74. doi: 10.1002/jts.22644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Monteleone AM, Tzischinsky O, Cascino G, Alon S, Pellegrino F, Ruzzi V, et al. The connection between childhood maltreatment and eating disorder psychopathology: a network analysis study in people with bulimia nervosa and with binge eating disorder. Eat Weight Disord. (2022) 27:253–61. doi: 10.1007/s40519-021-01169-6, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nelson JD, Cuellar AE, Cheskin LJ, Fischer S. Eating disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder: a network analysis of the comorbidity. Behav Ther. (2021) 53:310–22. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2021.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vanzhula IA, Calebs B, Fewell L, Levinson CA. Illness pathways between eating disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms: understanding comorbidity with network analysis. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2019) 27:147–60. doi: 10.1002/erv.2634, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cook JM, Simiola V, Hamblen JL, Bernardy N, Schnurr PP. The influence of patient readiness on implementation of evidence-based PTSD treatments in veterans affairs residential programs. Psychol Trauma. (2017) 9:51–8. doi: 10.1037/tra0000162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fetahi E, Sogaard AS, Sjogren M. Estimating the effect of motivational interventions in patients with eating disorders: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Pers Med. (2022) 12:577. doi: 10.3390/jpm12040577, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Geller J, Brown KE, Srikameswaran S. The efficacy of a brief motivational intervention for individuals with eating disorders: a randomized control trial. Int J Eat Disord. (2011) 44:497–505. doi: 10.1002/eat.20847, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jakupcak M, Hoerster KD, Blais RK, Malte CA, Hunt S, Seal K. Readiness for change predicts VA mental healthcare utilization among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. J Trauma Stress. (2013) 26:165–8. doi: 10.1002/jts.21768, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kaysen D, Jaffe AE, Shoenberger B, Walton TO, Pierce AR, Walker DD. Does effectiveness of a brief substance use treatment depend on PTSD? An evaluation of motivational enhancement therapy for active-duty Army personnel. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. (2022) 83:924–33. doi: 10.15288/jsad.22-00011, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Killeen TK, Cassin SE, Geller J. Motivational interviewing in the treatment of substance use disorders, addictions, and eating disorders In: Brewerton TD, Dennis AB, editors. Eating Disorders, addictions and substance use Disorders: Research, Clinical and Treratment Perspectives: Berlin, Germany: Springer; (2014) [Google Scholar]

- 107.Vitousek K, Watson S, Wilson GT. Enhancing motivation for change in treatment-resistant eating disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. (1998) 18:391–420. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00012-9, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Weiss CV, Mills JS, Westra HA, Carter JC. A preliminary study of motivational interviewing as a prelude to intensive treatment for an eating disorder. J Eat Disord. (2013) 1:34. doi: 10.1186/2050-2974-1-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chuemere AN, Oluwatayo BO, Kolawole TA, Ilochi ON. Starvation-induced changes in memory sensitization, habituation and psychosomatic responses. Int J Trop Dis Health. (2019) 35:1–7. doi: 10.9734/ijtdh/2019/v35i330126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Park SB, Coull JT, McShane RH, Young AH, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW, et al. Tryptophan depletion in normal volunteers produces selective impairments in learning and memory. Neuropharmacology. (1994) 33:575–88. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90089-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Riedel WJ, Klaassen T, Deutz NE, van Someren A, van Praag HM. Tryptophan depletion in normal volunteers produces selective impairment in memory consolidation. Psychopharmacology. (1999) 141:362–9. doi: 10.1007/s002130050845, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Brewerton TD, Gavidia I, Suro G, Perlman MM. Eating disorder patients with and without PTSD treated in residential care: discharge and 6-month follow-up results. J Eat Disord. (2023) 11:48. doi: 10.1186/s40337-023-00773-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Trottier K, Monson CM. Integrating cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder with cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders in PROJECT RECOVER. Eat Disord. (2021) 29:307–25. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2021.1891372, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Brewin N, Baggott J, Dugard P, Arcelus J. Clinical normative data for eating disorder examination questionnaire and eating disorder inventory for DSM-5 feeding and eating disorder classifications: a retrospective study of patients formerly diagnosed via DSM-IV. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2014) 22:299–305. doi: 10.1002/erv.2301, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. (2015) 28:489–98. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Des Jarlais DC. Harm reduction in the USA: the research perspective and an archive to David purchase. Harm Reduct J. (2017) 14:51. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0178-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Logan DE, Marlatt GA. Harm reduction therapy: a practice-friendly review of research. J Clin Psychol. (2010) 66:201–14. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20669, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yager J. Why defend harm reduction for severe and enduring eating Disorders? Who Wouldn't want to reduce harms? Am J Bioeth. (2021) 21:57–9. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2021.1926160, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Brewerton TD. Posttraumatic stress disorder and disordered eating: food addiction as self-medication. J Women's Health (Larchmt). (2011) 20:1133–4. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kearney-Cooke A, Striegel-Moore RH. Treatment of childhood sexual abuse in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a feminist psychodynamic approach. Int J Eat Disord. (1994) 15:305–19. doi: 10.1002/eat.2260150402, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Brewerton T. D., Trottier K., Trim J. G., Myers T., Wonderlich S. (2020). Integrating evidence-based treatments for eating disorder patients with comorbid PTSD and trauma-related Disorders. In Tortolani C. C., Goldschmidt A. B., Grange D. (Eds.), Adapting evidence-based treatments for eating Disorders for novel populations and settings: A practical guide (pp. 216–237). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Trottier K, Monson CM, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD. Results of the first randomized controlled trial of integrated cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. (2022) 52:587–96. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721004967, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Trottier K, Monson CM, Wonderlich SA, Olmsted MP. Initial findings from project recover: overcoming co-occurring eating disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder through integrated treatment. J Trauma Stress. (2017) 30:173–7. doi: 10.1002/jts.22176, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bloomgarden A, Calogero RM. A randomized experimental test of the efficacy of EMDR treatment on negative body image in eating disorder inpatients. Eat Disord. (2008) 16:418–27. doi: 10.1080/10640260802370598, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bongaerts H, Van Minnen A, de Jongh A. Intensive EMDR to treat patients with complex posttraumatic stress disorder: a case series. J EMDR Pract Res. (2017) 11:84–95. doi: 10.1891/1933-3196.11.2.84 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Boterhoven de Haan KL, Lee CW, Fassbinder E, van Es SM, Menninga S, Meewisse ML, et al. Imagery rescripting and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing as treatment for adults with post-traumatic stress disorder from childhood trauma: randomised clinical trial. Br J Psychiatry. (2020) 217:609–15. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.158, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Claudat K, Reilly EE, Convertino AD, Trim J, Cusack A, Kaye WH. Integrating evidence-based PTSD treatment into intensive eating disorders treatment: a preliminary investigation. Eat Weight Disord. (2022) 27:3599–607. doi: 10.1007/s40519-022-01500-9, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Cuijpers P, Veen SCV, Sijbrandij M, Yoder W, Cristea IA. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for mental health problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. (2020) 49:165–80. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2019.1703801, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Daneshvar S, Shafiei M, Basharpoor S. Compassion-focused therapy: proof of concept trial on suicidal ideation and cognitive distortions in female survivors of intimate partner violence with PTSD. J Interpers Viol. (2022) 37:NP9613–34. doi: 10.1177/0886260520984265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Goss K, Allan S. The development and application of compassion-focused therapy for eating disorders (CFT-E). Br J Clin Psychol. (2014) 53:62–77. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12039, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Irons C, Lad S. Using compassion focused therapy to work with shame and self-criticism in complex PTSD. Aust Clin Psychol. (2017) 3:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kelly AC, Wisniewski L, Martin-Wagar C, Hoffman E. Group-based compassion-focused therapy as an adjunct to outpatient treatment for eating disorders: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2017) 24:475–87. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2018, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lawrence VA, Lee D. An exploration of people's experiences of compassion-focused therapy for trauma, using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2014) 21:495–507. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1854, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lely JCG, Smid GE, Jongedijk RA, Knipscheer JW, Kleber RJ. The effectiveness of narrative exposure therapy: a review, meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2019) 10:1550344. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2018.1550344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Luo X, Che X, Lei Y, Li H. Investigating the influence of self-compassion-focused interventions on posttraumatic stress: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Mindfulness. (2021) 12:2865–76. doi: 10.1007/s12671-021-01732-3, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Monson CM, Chard KM, Morland LA. Written exposure therapy vs cognitive processing therapy. JAMA Psychiatry. (2018) 75:757–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0810, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Moreno-Alcazar A, Treen D, Valiente-Gomez A, Sio-Eroles A, Perez V, Amann BL, et al. Efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in children and adolescent with post-traumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:1750. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01750, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Morkved N, Hartmann K, Aarsheim LM, Holen D, Milde AM, Bomyea J, et al. A comparison of narrative exposure therapy and prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Clin Psychol Rev. (2014) 34:453–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.005, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Rothbaum BO, Astin MC, Marsteller F. Prolonged exposure versus eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for PTSD rape victims. J Trauma Stress. (2005) 18:607–16. doi: 10.1002/jts.20069, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, Resick PA. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. (2018) 75:233–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4249, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ten Napel-Schutz MC, Vroling M, Mares SHW, Arntz A. Treating PTSD with imagery rescripting in underweight eating disorder patients: a multiple baseline case series study. J Eat Disord. (2022) 10:35. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00558-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.ten Napel-Schutz MC, Karbouniaris S, Mares SHW, Arntz A, Abma TA. Perspectives of underweight people with eating disorders on receiving imagery Rescripting trauma treatment: a qualitative study of their experiences. J Eat Disord. (2022) 10:188. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00712-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Fogelkvist M, Gustafsson SA, Kjellin L, Parling T. Acceptance and commitment therapy to reduce eating disorder symptoms and body image problems in patients with residual eating disorder symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Body Image. (2020) 32:155–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.01.002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Juarascio AS, Forman EM, Herbert JD. Acceptance and commitment therapy versus cognitive therapy for the treatment of comorbid eating pathology. Behav Modif. (2010) 34:175–90. doi: 10.1177/0145445510363472, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Linardon J, Fairburn CG, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Wilfley DE, Brennan L. The empirical status of the third-wave behaviour therapies for the treatment of eating disorders: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. (2017) 58:125–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.005, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Orsillo SM, Batten SV. Acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Modif. (2005) 29:95–129. doi: 10.1177/0145445504270876, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Back M, Falkenstrom F, Gustafsson SA, Andersson G, Holmqvist R. Reduction in depressive symptoms predicts improvement in eating disorder symptoms in interpersonal psychotherapy: results from a naturalistic study. J Eat Disord. (2020) 8:33. doi: 10.1186/s40337-020-00308-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Duberstein PR, Ward EA, Chaudron LH, He H, Toth SL, Wang W, et al. Effectiveness of interpersonal psychotherapy-trauma for depressed women with childhood abuse histories. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2018) 86:868–78. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000335, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Markowitz JC. IPT and PTSD. Depress Anxiety. (2010) 27:879–81. doi: 10.1002/da.20752, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Markowitz JC, Petkova E, Neria Y, Van Meter PE, Zhao Y, Hembree E, et al. Is exposure necessary? A randomized clinical trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. (2015) 172:430–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070908, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Schramm E, Schneider D, Zobel I, van Calker D, Dykierek P, Kech S, et al. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy in chronically depressed inpatients. J Affect Disord. (2008) 109:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Whiston A, Bockting CLH, Semkovska M. Towards personalising treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of face-to-face efficacy moderators of cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for major depressive disorder. Psychol Med. (2019) 49:2657–68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719002812, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Donovan DM, Daley DC, Brigham GS, Hodgkins CC, Perl HI, Garrett SB, et al. Stimulant abuser groups to engage in 12-step: a multisite trial in the National Institute on Drug Abuse clinical trials network. J Subst Abus Treat. (2013) 44:103–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.04.004, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Kelly JF, Abry A, Ferri M, Humphreys K. Alcoholics anonymous and 12-step facilitation treatments for alcohol use disorder: a distillation of a 2020 Cochrane review for clinicians and policy makers. Alcohol Alcohol. (2020) 55:641–51. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agaa050, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Project MATCH Research Group . Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol. (1997) 58:7–29. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.7, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Mitchell KS, Singh S, Hardin S, Thompson-Brenner H. The impact of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder on eating disorder treatment outcomes: investigating the unified treatment model. Int J Eat Disord. (2021) 54:1260–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.23515, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Church D, Stapleton P, Mollon P, Feinstein D, Boath E, Mackay D, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of PTSD using clinical EFT (emotional freedom techniques). Healthcare. (2018) 6:146. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6040146, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Monteleone AM, Pellegrino F, Croatto G, Carfagno M, Hilbert A, Treasure J, et al. Treatment of eating disorders: a systematic meta-review of meta-analyses and network meta-analyses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2022) 142:104857. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104857, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Sijercic I, Liebman RE, Ip J, Whitfield KM, Ennis N, Sumantry D, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual and couple therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder: clinical and intimate relationship outcomes. J Anxiety Disord. (2022) 91:102613. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102613, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Bohus M, Dyer AS, Priebe K, Kruger A, Kleindienst N, Schmahl C, et al. Dialectical behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual abuse in patients with and without borderline personality disorder: a randomised controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. (2013) 82:221–33. doi: 10.1159/000348451, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Harned MS, Gallop RJ, Valenstein-Mah HR. What changes when? The course of improvement during a stage-based treatment for suicidal and self-injuring women with borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Psychother Res. (2018) 28:761–75. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1252865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Bellehsen M, Stoycheva V, Cohen BH, Nidich S. A pilot randomized controlled trial of transcendental meditation as treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans. J Trauma Stress. (2021) 35:22–31. doi: 10.1002/jts.22665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Bormann JE, Thorp SR, Smith E, Glickman M, Beck D, Plumb D, et al. Individual treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder using Mantram repetition: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. (2018) 175:979–88. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17060611, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Carei TR, Fyfe-Johnson AL, Breuner CC, Brown MA. Randomized controlled clinical trial of yoga in the treatment of eating disorders. J Adolesc Health. (2010) 46:346–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.007, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Foa E, Hembree E, Rothbaum BO. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: emotional processing of traumatic experiences, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 166.Gallegos AM, Crean HF, Pigeon WR, Heffner KL. Meditation and yoga for posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. (2017) 58:115–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.004, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Haider T, Chia-Liang D, Sharma M. Efficacy of meditation-based interventions on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among veterans: a narrative review. Adv Mind Body Med. (2021) 35:16–24. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Hilton L, Maher AR, Colaiaco B, Apaydin E, Sorbero ME, Booth M, et al. Meditation for posttraumatic stress: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Trauma. (2017) 9:453–60. doi: 10.1037/tra0000180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Kelly U, Haywood T, Segell E, Higgins M. Trauma-sensitive yoga for post-traumatic stress disorder in women veterans who experienced military sexual trauma: interim results from a randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. (2021) 27:S45–59. doi: 10.1089/acm.2020.0417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Mavranezouli I, Megnin-Viggars O, Daly C, Dias S, Stockton S, Meiser-Stedman R, et al. Research review: psychological and psychosocial treatments for children and young people with post-traumatic stress disorder: a network meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2020) 61:18–29. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Mitchell KS, Mazzeo SE, Rausch SM, Cooke KL. Innovative interventions for disordered eating: evaluating dissonance-based and yoga interventions. Int J Eat Disord. (2007) 40:120–8. doi: 10.1002/eat.20282, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Seppala EM, Nitschke JB, Tudorascu DL, Hayes A, Goldstein MR, Nguyen DT, et al. Breathing-based meditation decreases posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in U.S. military veterans: a randomized controlled longitudinal study. J Trauma Stress. (2014) 27:397–405. doi: 10.1002/jts.21936, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Iverson KM, Litwack SD, Pineles SL, Suvak MK, Vaughn RA, Resick PA. Predictors of intimate partner violence revictimization: the relative impact of distinct PTSD symptoms, dissociation, and coping strategies. J Trauma Stress. (2013) 26:102–10. doi: 10.1002/jts.21781, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]