Abstract

Dopamine is an important neurotransmitter that plays a critical role in motivational salience and motor coordination. However, dysregulated dopamine metabolism can result in the formation of reactive electrophilic metabolites which generate covalent adducts with proteins. Such protein damage can impair native protein function and lead to neurotoxicity, ultimately contributing to Parkinson’s disease etiology. Within this Review, the role of dopamine induced protein damage in Parkinson’s disease is discussed, highlighting the novel chemical tools utilized to drive this effort forward. Continued innovation of methodologies which enable detection, quantification, and functional response elucidation of dopamine-derived protein adducts is critical for advancing this field. Work in this area improves foundational knowledge of the molecular mechanisms that contribute to dopamine-mediated Parkinson’s disease progression, potentially assisting with future development of therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, dopamine, orthoquinone, dopamine o-quinone, dopaquinone, electrophilic metabolites, non-enzymatic posttranslational modification, protein adduct, protein damage, chemical probes

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

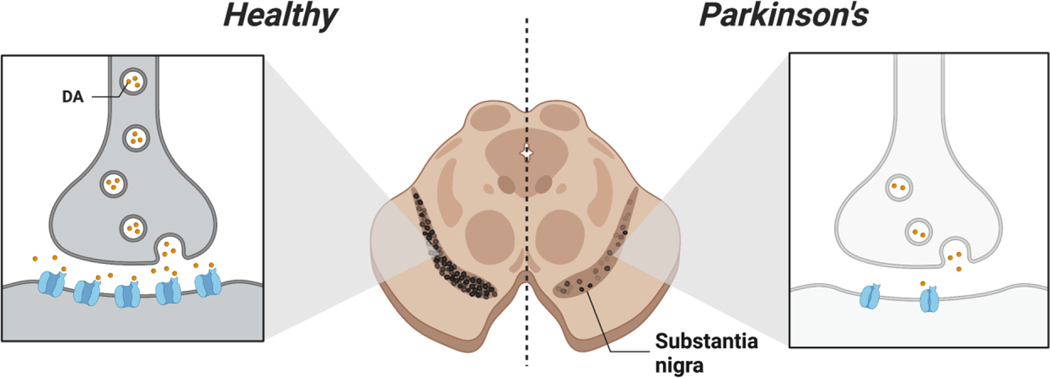

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that afflicts over five million individuals globally.1 PD symptomology manifests as a continual decline in motor function, resulting in rigidity, bradykinesia, tremor at rest, and postural instability.2 The cause of motor dysfunction in PD is largely attributed to the depletion of striatal dopamine (DA) due to the death of dopaminergic neurons, particularly in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) (Figure 1).3 However, the events that initiate dopaminergic collapse in the SNc are thought to take place up to a decade prior to diagnosis, as it is estimated that 50–90% of dopaminergic neurons have already been lost by that time.4 Currently, there are no approved therapeutics that halt or slow PD. Thus, improving understanding of the molecular underpinnings that initiate PD remains an important area in developing novel treatments.

Figure 1.

Loss of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Pictural representation of autopsied midbrain sections from healthy and PD diagnosed individuals (right and left respectively). Impairment and death of dopaminergic neurons is a hallmark of PD.

Herein, we discuss the role that dysregulated DA plays in driving PD pathology,5 highlighting the contribution of covalent protein damage induced by reactive DA metabolites. Additionally, novel methodologies that enable studying protein damage inflicted by DA metabolites are presented. We conclude with an outlook on this area of PD research and a perspective on how further work investigating DA-protein damage in the brain will aid in elucidating PD etiology.

DOPAMINE METABOLISM & FORMATION OF REACTIVE DOPAMINE METABOLITES

DA was first reported to be a neurotransmitter by Arvid Carlsson in 1957.6 Since, DA has been found to modulate a multitude of physiological processes, ranging from motivational salience to motor coordination, and roles outside the central nervous system.7, 8 The link between DA and PD was shown by Oleh Hornykiewicz, who reported that DA concentration is drastically decreased in the midbrains of PD patients compared to healthy controls.9 This landmark study launched the use of the DA metabolic precursor, L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA), as a treatment for PD.10 Despite the symptomatic relief L-DOPA can provide in PD, the underlying neurodegenerative processes involved in the disease are not affected, which has sparked some debate over its continued use.11–14 Regardless, DA remains a central player in PD etiology, and emerging evidence points to reactive DA metabolites being contributors to the pathology.15

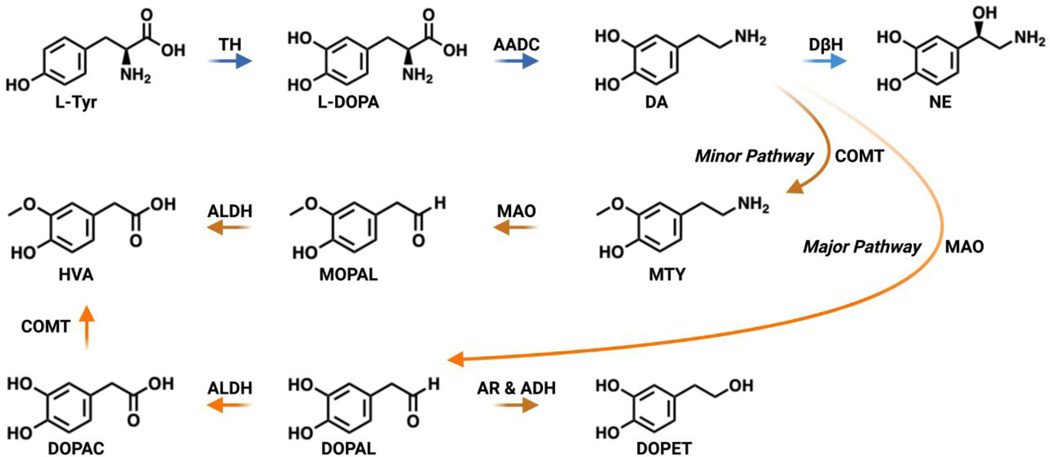

DA metabolism is a carefully orchestrated process overseen by various enzymatic and sequestering systems.16 It has been hypothesized that disruption of these systems can lead to production of reactive DA metabolites, buildup of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and impair carbonyl metabolism, all of which can impart neurotoxicity.17 A summary of DA metabolism is shown in Figure 2. DA generation commences with the hydroxylation of L-Tyr by tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) to give L-DOPA.18 Next, L-DOPA is decarboxylated via aromatic acid decarboxylase (AADC) through a tetrahydrobiopterin (H4- biopterin) and iron dependent manner to furnish DA.19 Once DA is created, it can be converted to norepinephrine (NE) by a copper containing monooxygenase, dopamine β-hydroxylase (DβH), or catabolized by one of two major and minor pathways.20 In the major pathway, DA is deaminated to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL) by monoamine oxidase (MAO). MAO is a flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) oxidase that produces hydrogen peroxide and ammonia as additional byproducts in this reaction.21 MOA is also anchored to the outer mitochondrial membrane and can shuttle electrons from DA metabolism to the mitochondrial electron transport chain.22 DOPAL is further oxidized to its corresponding acid, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), by an aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH).23 DOPAC is subsequently methylated to form homovanillic acid (HVA) through catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT).24, 25 HVA is an inert byproduct capable of being excreted. In the minor pathway, one of the hydroxyls of DA is first capped by a methyl group via COMT to afford 3-methoxytyramine (MTY), which is consequently deaminated by MAO to give 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl acetaldehyde (MOPAL) and oxidized by ADH to HVA.26 Additionally, the aldehyde functionality within DOPAL can be reduced, primarily by cytosolic aldehyde reductases (AR) or by alcohol dehydrogenases (ADH), to produce 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol (DOPET) as a minor metabolite.27–29 Together, these enzymatic pathways regulate the biosynthesis and metabolism of DA in presynaptic dopaminergic neurons.

Figure 2.

Primary pathways for dopamine biosynthesis and metabolism. DA is generated from L-Tyr by TH and AADC. DA can be converted by DβH to NE or broken down by two major and minor pathways consisting of transformations catalyzed by MAO, ADH, ALDH, AR and COMT.

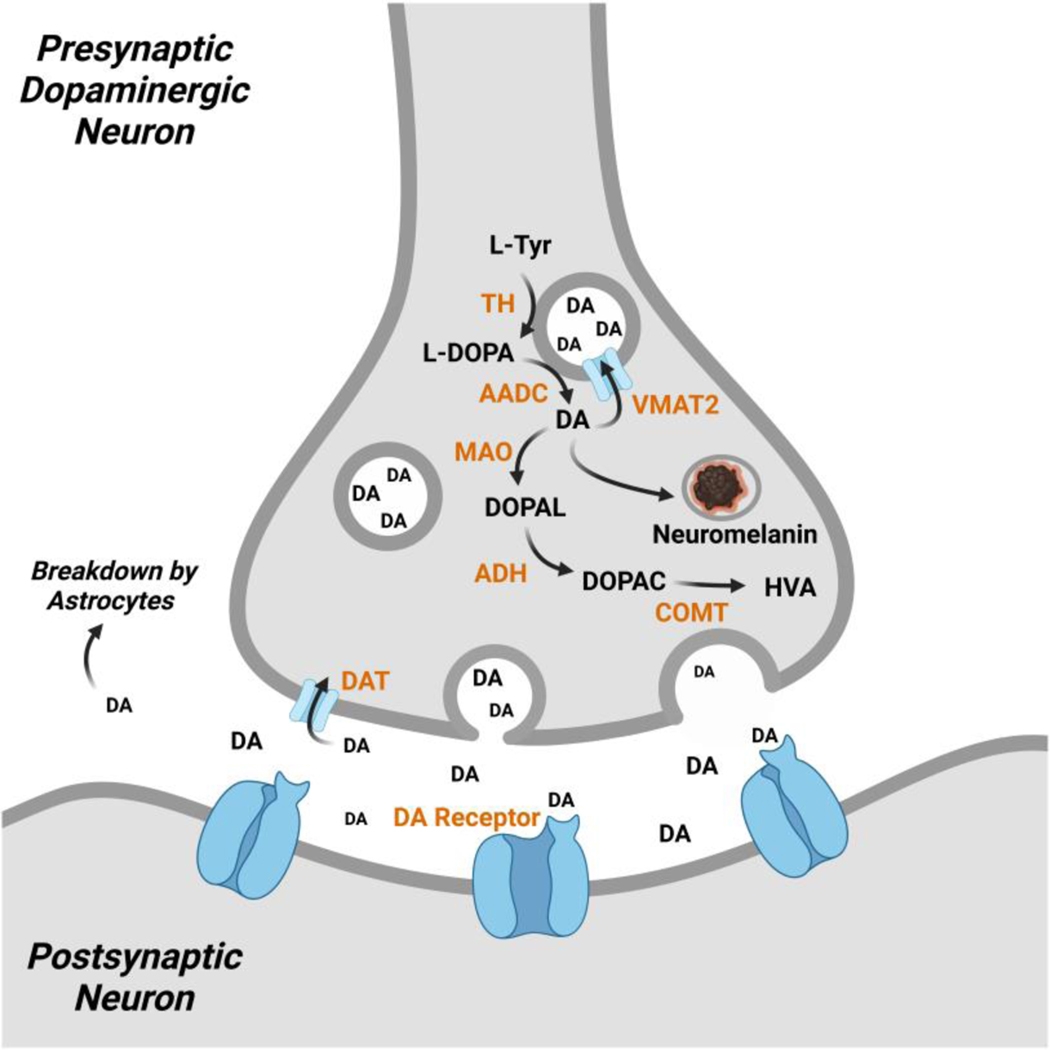

Beyond enzymatic regulation, DA concentrations in neurons are controlled by subcellular compartmentalization. An overview of these processes is depicted in Figure 3. Within DA presynaptic neurons, DA is primarily housed within synaptic vesicles. Vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) is the transporter responsible for this shuttling of DA.30 The two enzymes that biosynthesize DA from L-Tyr, TH and AACD are also physically associated with VMAT2 to assist in the confinement of DA.31, 32 The H+ ATPase localized in the vesicular membrane pumps protons inside the vesicle to maintain an acidic environment in order to stabilize the confined DA.33 DA concentrations are reported to reach up to 1 M in vesicles, whereas cytosolic concentrations are measured in the low μM range.34, 35 DA released into the synaptic cleft undergoes reuptake by dopamine transporter (DAT) for vesicular repacking or is broken down by astrocytes in close proximity.36 Residual cytosolic DA in presynaptic neurons is catabolized to HVA or sequestered into granules of neuromelanin.37 Proper regulation of DA handling systems is critical for dopaminergic health.

Figure 3.

Dopamine handling systems in neurons. DA is created by TH and AADC which is then sequestered into synaptic vesicles by VMAT2. Excess cytosolic DA is converted to HVA by MAO, ADH, and COMT or enveloped into neuromelanin. Residual DA in the synaptic cleft following release by the presynaptic neuron undergoes reuptake by DAT and is repackaged in synaptic vesicles or is broken down by neighboring astrocytes.

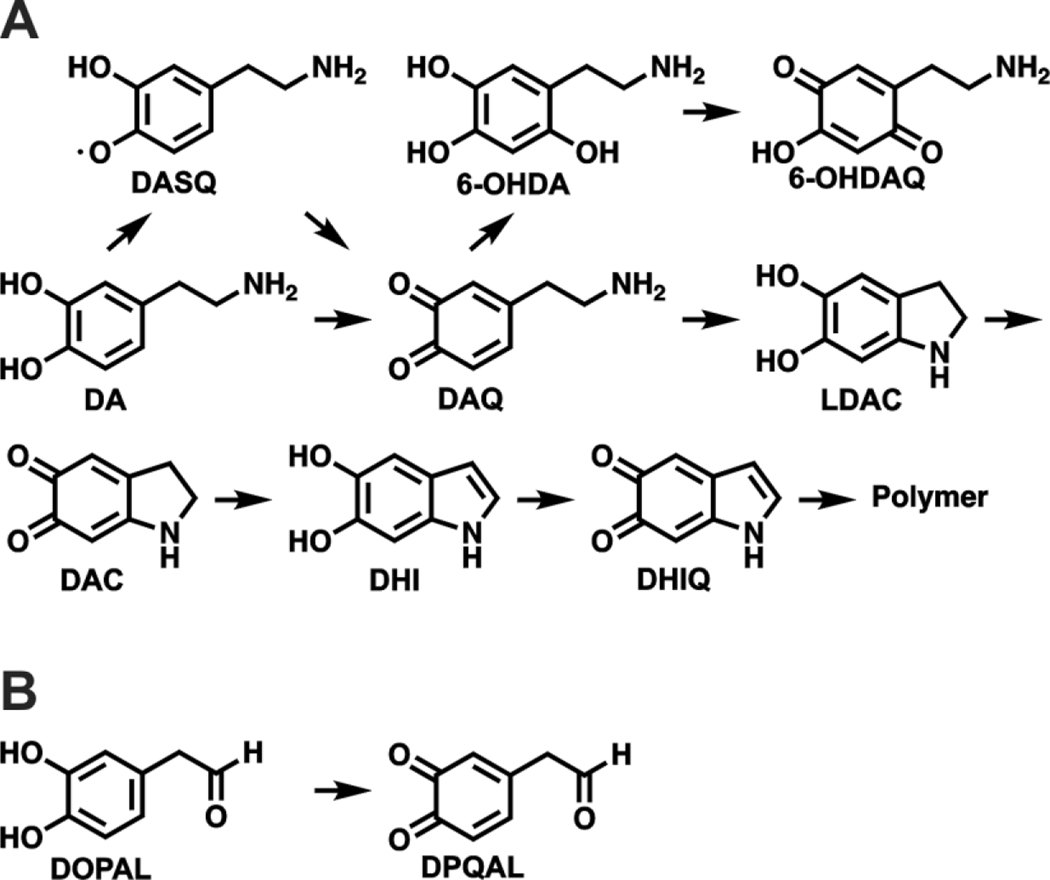

Because of its catechol structure, DA has a propensity to spontaneously form reactive metabolites (Figure 4A). When not confined to the acidic environment of synaptic vesicles, DA is susceptible to oxidation by a variety of processes to give dopamine semiquinone (DASQ) or dopaquinone (DAQ).38 DASQ can be generated in vivo enzymatically through H2O2 activation by peroxidases and prostaglandin H synthase.39, 40 DAQ is formed through auto oxidation at cytosolic pH; this process can be accelerated by metals like Cu and Fe.41 DAQ rapidly undergoes intramolecular cyclization to afford leukodopaminochrome (LDAC).42 However, in some cases, DAQ can be converted to 6-OHDA (6-hydroxydopamine) and 6-OHDQ (6-hydroxydopaquinone) by ROS and Fe.43, 44 LDAC is also prone to oxidation, akin to DA, to form dopaminochrome (DAC).45 DAC undergoes a tautomeric rearrangement to 5,6-dihydroxyindole (DHI), which further oxidizes to 5,6-dihydroxyindolequinone (DHIQ) and ultimately polymerizes to neuromelanin.46 As shown in Figure 4B, the catechol in DOPAL can also be oxidized to a quinone to give DOPAL quinone (DPQAL), another reactive DA derived metabolite.47 Collectively, DA oxidation in vivo leads to a complex array of potentially toxic electrophilic metabolites that can react with proteins, necessitating tight regulation over neuronal DA metabolism.

Figure 4.

Dopamine derived reactive metabolites. A) Oxidation products of DA. DA can undergo a 1 e- oxidation to DASQ or a 2 e- oxidation to DAQ. DAQ cyclizes to LDAC or reacts with ROS to form 6-OHDA. 6-OHDA can further oxidize to 6-OHDQ. LDAC can oxidize to DAC which can rearrange to DHI. DHI can oxidize to DHIQ which polymerizes due to instability. B) Oxidization of DOPAL to DPQAL.

There is accumulating evidence that DA handling systems are dysregulated in the context of PD, contributing to disease progression.48, 49 Specifically, vesicular uptake of DA by VMAT2 is reduced by 87–90% in autopsied striatum sections of PD patients as compared to healthy controls.50 Impaired vesicular DA uptake leads to accumulation of cytosolic DA, which could have deleterious consequences on neuronal health.51, 52 Accordingly, genetically enhanced vesicular function of DA provides neuroprotection against the dopaminergic toxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) in murine models of PD.53 Furthermore, several promoter haplotypes that increase the expression of VMAT2 are associated with a decreased incidence of PD.54 In other investigations of PD etiology, accumulation of oxidized DA has been longitudinally linked to a toxic cascade of neurological dysfunction correlated with idiopathic and familial PD cases.55 Together, these studies point to the importance of DA regulation in PD.

Beyond improper DA storage in PD, other pathological factors of PD can exacerbate DA inflicted stress.56 One of these factors is higher Fe and other metal content in the brains of PD patients as compared to healthy controls.57–59 The presence of redox active metals can induce oxidative stress and promote DA oxidation.60, 61 Additionally, the concentrations of ROS scavenging molecules like glutathione (GSH) are decreased in PD, perpetuating the toxicity of cytosolic DA.62, 63 Collectively, there are multiple pathways that can lead to DA dysregulation and faulty DA toxification which can contribute to PD progression. Next, we will explore specific reactions of DA metabolites, along with the ensuing DA damage protein and its relevance to PD.

PROTEIN DAMAGE CAUSED BY DOPAMINE METABOLITES

DA has long been recognized as a driver of oxidative stress in the brain.64, 65 Intrastriatal injections of DA in rats caused neuronal degeneration, providing an early demonstration of DA toxicity in the SNc.66 Importantly, DA toxicity could be alleviated by co-administration of a reductant such as ascorbic acid or GSH, suggesting that oxidized DA metabolites were responsible for inducing damage. Understanding the molecular mechanisms responsible for DA toxicity in the brain remains an active area of research.67

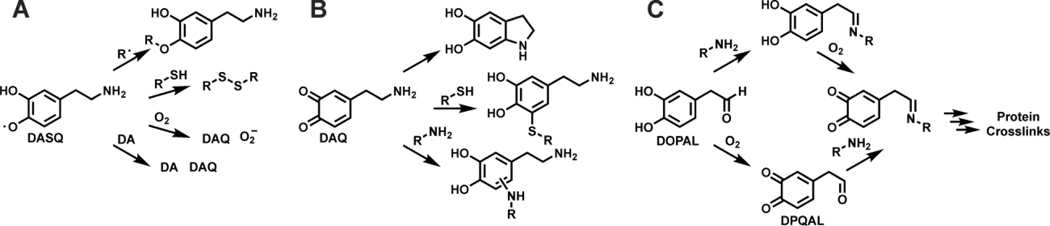

DA metabolites can undergo a variety of chemical reactions that can impart cellular damage.68 An overview of these reactions is shown in Figure 5. Some DA metabolites are less stable than others, DASQ being an example. As shown in Figure 5A, DASQ can couple with other radicals, scavenge cellular thiols like GSH, undergo a one electron oxidation by O2 to generate DAQ and O2-, or disproportion to DA and DAQ, all of which can inflict toxicity.69, 70 DAQ and other quinone species like DAC, DHIQ, and 6-OHDQ can react with various nucleophilic amino acid residues, which is depicted in Figure 5B.71 Among amino acids sidechains, Cys has the highest reactivity towards DA-derived quinones, as thiols have a rate constant 10,000-fold higher than amines for nucleophilic attack at the quinone core.72–74 It has been postulated that the reaction between thiols and ortho-quinones may proceed through a radical mechanism which accounts for the rapid reaction rate and high regioselectivity of thiol addition to the 5 position in the ring.75 In addition to Cys, Lys and His sidechains can react with DA metabolites.76–78 The metabolites DOPAL and DPQAL also harbor reactive groups susceptible to modification and thus have been reported as capable of inducing toxicity.17, 79, 80 As shown in Figure 5C, the aldehyde groups of DOPAL and DPQAL can form a Schiff base with amine groups of proteins and peptides.81 Following Schiff base formation DOPAL can oxidize to its DPQAL form and undergo addition to give rise to crosslinked products.28, 82, 83 It is likely that free DPQAL alone is a minor contributor to protein crosslinking due to its inherit instability. However, the chemistry of DOPAL is complex, therefore studies investigating the reactivity of this metabolite need to carefully consider experimental variables such as pH and use of deoxygenated media. Such experimental conditions may bias observed DOPAL reactivity profiles as these factors influence the rates of Schiff base formation and autooxidation processes and thus may not fully recapitulate in vivo conditions. In some cases, two molecules of DOPAL can react with a Lys residue to generate a dicatechol pyrrole adduct.84 Additionally, once formed, DA protein adducts can redox cycle and produce additional ROS.85 Collectively, the reactivity of DA metabolites is the basis for the damage they can impart on proteins.

Figure 5.

Chemical reactions of dopamine metabolites. A) Reactions by DASQ; radical cross coupling, thiol oxidation, superoxide generation, and disproportionation. Shown from top to bottom. B) Reactions by DAQ: intramolecular cyclization, thiol addition, amine addition (shown from top to bottom). Note that other DA-derived quinones can undergo similar additions. C) Reactions by DOPAL; imine condensation, oxidation to DPQAL, and protein crosslink formation to due to nucleophile addition into the ring.

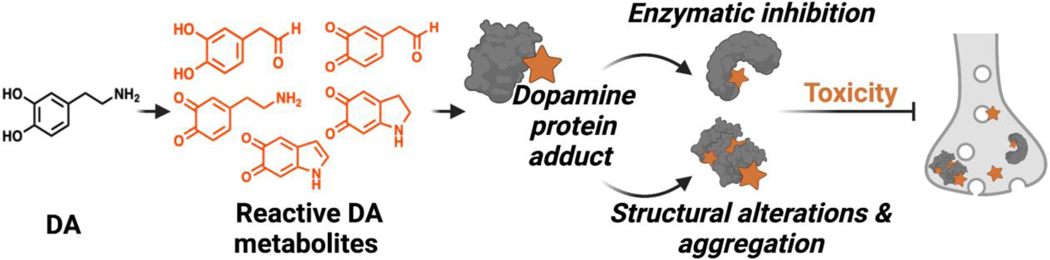

DA metabolites have been reported to react with a diverse array of proteins. The resulting adducts can impair protein function or cause structural alterations to the native confirmation (Figure 6). These protein modifications can have deleterious effects on many biochemical pathways relevant to PD. Below we discuss various reported DA adducted proteins which are also summarized in Table 1.

Figure 6.

Protein damage inflicted by reactive DA metabolites can drive neurotoxicity through enzymatic inhibition and conformational changes.

Table 1.

Reported dopamine adducted proteins, functional ramifications, and methods of detection.

| Protein | Functional consequences of DA modification | Method of adduct detection | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tyrosine Hydroxylase | Inhibition of enzymatic activity | Radiolabel, NBT staining | 86, 87 |

| Dopamine Transporter | Inhibition of transporter activity | Mutagenesis | 88 |

| Nuclear Receptor Related-1 Protein | Stimulation of Nurr1 transcriptional activity | X-ray | 91 |

| Superoxide Dismutase 2 | Inhibition of enzymatic activity | Radiolabel, NBT staining, Mutagenesis | 100 |

| Glutathione Peroxidase 4 | Inhibition of enzymatic activity | Radiolabel | 103 |

| ATP Synthase | Impairment of mitochondrial ATP synthesis | Radiolabel, MS | 105 |

| Glutathione-S-Transferase | Inhibition of enzymatic activity | NBT staining | 106 |

| Alpha Synuclein | Alteration of oligomer and fibril formation | Radiolabel, Boronate enrichment | 123–130 |

| Parkin | Inhibition of E3 ligase function | Radiolabel, Boronate enrichment, MS | 134, 135 |

| Glucocerebrosidase | Inhibition of enzymatic activity | nIRF, MS | 55 |

| DJ-1 | Alteration of protein structure | Radiolabel, NBT staining, Mutagenesis | 139 |

| Protein Disulfide Isomerase | Inhibition of enzymatic activity | Bioorthogonal probe, MS | 117, 118 |

DA metabolites have been shown to damage numerous regulatory proteins involved in DA homeostasis. One of the first proteins reported to react with DA metabolites was tyrosine hydroxylase (TH).86, 87 Through the use of radiolabeled DA, TH was shown to be covalently modified by oxidized DA metabolites and to become functionally inhibited as a result.86 DAT, another DA handling enzyme, was also found to be adducted by DA metabolites at Cys residues which resulted in blocked DA uptake.88 Additionally, dihydropteridine reductase (DHPR) activity is inhibited by DA derived quinones, however it is not known if this occurs through covalent modification.89 DHPR regenerates tetrahydrobiopterin, which is a cofactor required for hydroxylation reactions and biosynthesis of DA precursors L-Tyr and L-DOPA.90 The metabolite DHI has been shown to covalently bind a regulatory Cys in the nuclear receptor related-1 protein (Nurr1) which stimulates Nurr1 activity in cell culture and zebrafish.91 Nurr1 is a transcription factor that regulates expression of critical maintenance and survival genes of dopaminergic neurons, including DA handling systems like TH, VMAT2 and DAT.92–97 In fact, all of these aforementioned proteins are important players in DA regulation, thus their inhibition by aberrant DA metabolites fuels a vicious cycle of DA dysregulation relevant to PD.

Oxidized DA metabolites have been linked to mitochondrial dysfunction and disruption of mitochondrial electron transport.98, 99 Consequently, various mitochondrial proteins are reported to be impaired by reactive DA species. For example, superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2), aggregates in the presence of DAQ due to covalent Cys adducts in vitro, which results in diminished catalytic activity.100 SOD2 is responsible for converting superoxide into H2O2 and O2.101 Inhibition of SOD2 activity can result in mitochondrial dysfunction in vivo.102 The selenoprotein glutathione peroxidase 4 is also functionally inhibited by DAQ, forming aggregates in vitro and in rat neuronal PC12 cells.103 Glutathione peroxidase 4 is a mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme that reduces a variety of cellular peroxides which is combative against oxidative stress and thus hypothesized to be protective against neurodegeneration.104 In isolated rat brain mitochondria treated with radiolabeled DA, ATP synthase was found to be a target of DA metabolites.105 Particularly at the γ-subunit of the F 1 catalytic domain as determined by mass spectrometry. This modification resulted in impaired ATP production. In the same study, DA derived quinones also affected mitochondrial morphology. As a whole, mounting evidence suggests that oxidized DA metabolites can elicit mitochondrial dysfunction through protein adduct formation and damage.

Excess reactive DA species have been shown to damage antioxidant pathways. DOPAL inhibits glutathione-S-transferase (GST) in vitro through covalent modification of this protein.106 GST catalyzes the addition of GSH to reactive metabolites of DA, which serves as a general cellular detoxification mechanism.107 Overexpression of GST was found to be protective in a Drosophila model of PD.108 Additionally, high levels of DA administered to astroglial cells resulted in GSH depletion.109 Thus inhibition of GST and GSH reduction by dysregulated DA may promote oxidative damage in PD.

DA metabolites have been found to modify endoplasmic reticulum (ER) proteins. The ER plays a critical role in maintaining protein homeostasis. ER stress results in accumulation of unfolded proteins and activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR).110 ER stress and UPR is a driver of neurodegenerative processes and PD progression.111–114 Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) is a prominent ER chaperon protein responsible for properly folding proteins by catalyzing disulfide bond formation.115 Disruption of PDI activity can lead to ER stress and UPR activation.116 Oxidized DA metabolites have been reported to modify PDI in cell models and inhibit PDI activity in vitro.117, 118 Additionally, ER stress is induced by 6-OHDA in cell models.114 Thus it is possible that dysregulated DA metabolism may influence ER stress experienced in PD.

Various proteins with genetic ties to PD are known to be damaged by DA metabolites. Among these is the vesicular trafficking protein, alpha synuclein (AS). AS is closely linked with PD as mutations in this protein results in PD development.119, 120 AS is also a main component of Lewy bodies, which are insoluble intracellular protein aggregates observed in the brains of PD patients.121, 122 Numerous studies, ranging from in vitro analyses to animal models of PD, have shown that DA metabolites interact with AS, promote AS aggregation, disrupt AS linked synaptic vesicle function, impede chaperone-mediated autophagy processes, and induce degeneration.82, 123–130 Additionally, DA modified AS has been found in plasma of PD patients, further strengthening the importance of this adduct.131 Parkin is another protein where mutations are linked to early onset PD.132 Parkin is a E3 ubiquitin ligase that helps clear damaged mitochondria via autophagy and proteasomal mechanisms.133 DA metabolites have been shown to inhibit parkin activity in cell culture, and parkin-DA adducts have been found in autopsied PD brains.134, 135 DJ-1 is a redox sensor protein associated with familial PD.136 The physiological function of DJ-1 is still being elucidated, but it is well established that DJ-1 confers neuroprotection against oxidative stress.137, 138 DJ-1 has been found to be covalently modified by DA derived quinones in vitro, leading to structural alteration of DJ-1.139 Mutations in glucocerebrosidase (GCase) are correlated with PD development.140 GCase hydrolyzes the glycosidic bond in glucocerebroside glycolipids and is a key component in proper lysosome function.141 Reactive DA metabolites have been found to adduct a Cys residue in the active site of GCase in neurons obtained from patients with idiopathic and familial PD, resulting in impaired lysosomal function.55 Given that DA metabolites target and inhibit proteins whose dysfunction is already linked to PD, a compelling case can be made for mishandled DA being involved in idiopathic occurrences of PD.

Histones, the proteins involved in DNA packaging within the nucleus, have been reported to be modified by DA via transglutaminase 2 (TGM2).142, 143 TGM2 catalyzes amide bond formation between the carboxylic acid sidechain of Glu and the amine of DA to yield a DA-histone linkage. The levels of this modification in rat brains were modulated by cocaine and heroin administration. Consequently, the degree of histone DA modification changed levels of gene expression and drug seeking behavior. Although this histone modification does not involve reactive metabolites of DA, dysregulated DA concentrations in PD may influence levels of this histone mark and lead to pathological alterations in gene expression.144 Whether histone modifications are relevant in PD pathology remains to be seen, however it is an intriguing area to explore in the future.

Beyond protein dysfunction induced by DA modification, antibodies reactive to DA adducted ovalbumin have been found in PD patient serum. The presence of such DA damage recognizing antibodies creates a possible link to the immune system being involved in PD as DA damage recognizing antibodies could generate or amplify inflammatory responses in PD.145 Additionally, DA derived neuromelanin is capable of activating innate immune cells, microglia, which induce degeneration of DA neurons.146 Growing evidence points to immune system dysfunction playing a role in PD progression.147–149 The studies mentioned above suggest that DA and DA induced protein damage may contribute to aberrant immune responses in PD.

Collectively, covalent protein modifications by reactive DA metabolites can drive neuronal toxicity.150, 151 The studies described above provide evidence that dysregulation of DA is a critical factor in PD progression. Further elucidation of the molecular underpinnings of DA dependent damage is key in fully understanding PD etiology. Many efforts in this area utilize chemical tools to drive this research forward. Below, various strategies for studying DA dysregulation using chemical biology and analytical chemistry tools are presented.

TOOLS TO STUDY DOPAMINE DYSFUNCTION

The chemical toolbox used to interrogate the consequences of dysregulated DA is growing. Some of the existing approaches utilize DA mimetic probes, whereas others rely on the chemical structure and reactivity of DA itself. Analytical methodologies are also critical for studying DA dynamics and dysfunction. In the case of identifying DA modified proteins, certain methods provide a higher degree of unambiguous evidence for DA adduction than others. For instance, MS/MS analysis of an adducted peptide provides concrete verification that a particular protein is indeed susceptible to DA modification, whereas other approaches (e.g., radiolabeling, immunoprecipitation, redox detection, etc.) provide only presumptive evidence for a DA adduct within a particular protein. Below, we will discuss examples of these classes, highlight how different tools provide valuable insights into DA’s role in PD, and underscore advantages and disadvantages of given technologies.

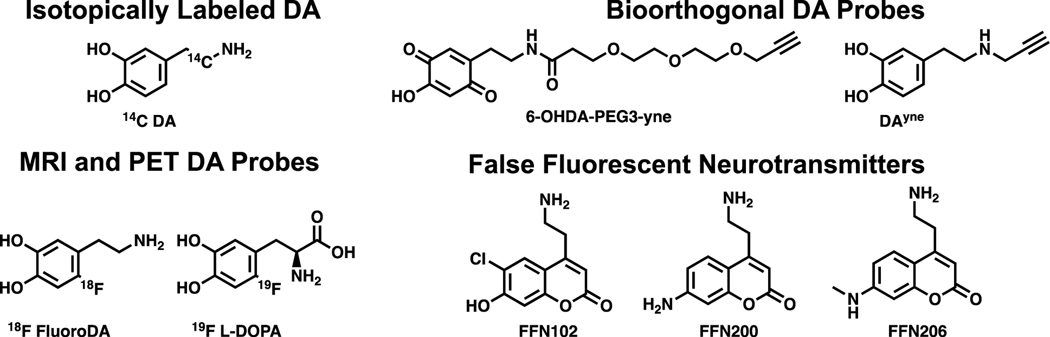

DA derivatives come in many modalities (Figure 7). For example, radiolabeled DA is an effective probe for studying DA driven protein damage. In pioneering work, 14C-dopamine in combination with autoradiography was used to identify proteins modified by DA metabolites.152, 153 These studies provided an initial set of DA adducted proteins to be further investigated. While introduction of 14C in DA is advantageous in terms of imposing minimal structural changes to the DA scaffold, the toxicity and regulatory hurdles associated with 14C hamper the use of radioactive isotopes.154 Alternative probe-based strategies to identify proteins damaged by DA derived species have leveraged bioorthogonal chemistries to enrich DA adducted proteins prior to identification by mass spectrometry.155 Enrichment of structurally modified protein species is important for their identification due to signal suppression by unmodified peptides during mass spectrometry analyses. For example, alkynylated derivatives of 6-OHDA and DA, dubbed 6-OHDA-PEG3-yne and DAyne respectively, have been reported (Figure 7).117, 118 These researchers have successfully demonstrated the utility of bioorthogonal functionalization of DA as it enabled detection and proteomic identification of proteins modified by DA metabolites when 6-OHDA-PEG3-yne was administered to cellular lysates or when DAyne was incubated in cell culture. It should be noted that care must be taken in the design of structurally altered DA mimetic probes as to not drastically alter their physicochemical properties from those of DA. As a testament to this, 6-OHDA-PEG3-yne is unable to traverse membranes in living cells whereas DAyne can. As a whole, functionalized DA derivatives make powerful tools for broad scale proteomic studies of DA adducted proteins.

Figure 7.

Classes and structures of dopamine mimetic probes.

Additional DA based probes have been designed for tracking DA dynamics and signaling pathways. These efforts have been recently reviewed.156 Briefly, 18F fluorodopamine and 19F-L-DOPA probes were developed to be used for positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 7).157, 158 These tools can report on DA localization in vivo. Another class of tools are fluorescent false neurotransmitters (FFNs) like FFN102, FFN200, and FFN206 which are substrates for DA handling enzymes and used in confocal microscopy applications (Figure 7).159–161 While these molecules do not directly report on protein damage caused by dysregulated DA, they are critical for deciphering DA dynamics and trafficking in vitro and in vivo.

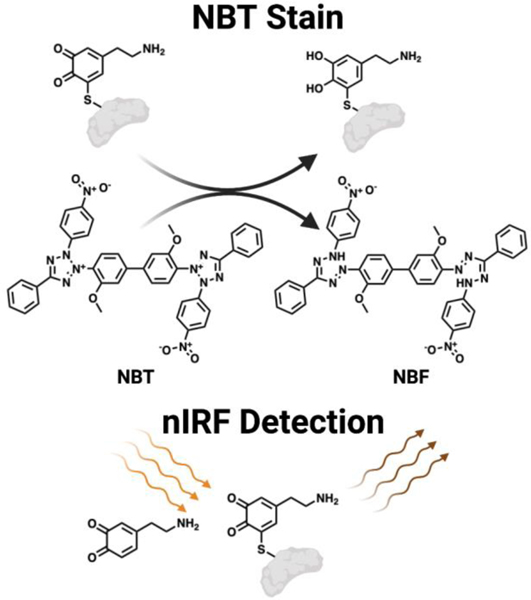

The second category of tools for studying DA disposition in the brain take advantage of the molecule’s redox reactivity (Figure 8). Early efforts in detecting proteins covalently modified by DA metabolites relied on the redox sensitive catechol functionality possessed by DA metabolites.162 Following immobilization of quinone modified proteins on a membrane, a basic nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) solution, which redox cycles with the membrane bound adducted proteins to produce nitroblue formazan (NBF), can be applied. NBF in turn deposits on and stains the membrane purple, enabling visual detection of protein bound quinones. This technique was utilized in a comparative proteomic study aimed at profiling DA modified proteins in 2- and 15-month rats.163 These researchers found that levels of DA adducted proteins increase with age. This methodology is useful for comparing relative amounts of quinone modified proteins between samples, however it is unable to distinguish different species of quinones from one another. Other redox cycling quinone protein detection strategies have been reported using a dithiothreitol (DTT) and luminol system to generate quantifiable chemiluminescence.164 Such techniques may have utility for DA metabolites as well. A similar approach for detecting immobilized protein bound ortho quinones or free ortho quinones alone, utilizes the spectroscopic properties of these molecules.165 Here, a near-infrared fluorescence (nIRF) imager is used to excite bound quinones at 685 nm and the resultant emission from the ortho quinone is measured at 700 nm. This is selective for ortho quinones/catechols over meta and para substituted analogs. This method enables the detection of oxidized DA at nmol levels. However, similar to detection via redox cycling, this procedure is unable to differentiate species of protein bound quinones. Despite limitations, these tools are robust methodologies for quantifying global levels of protein damage induced by DA metabolites.

Figure 8.

Methods to detect dopamine-protein adducts. Top: Schematic of NBT redox cycle with a DA protein adduct to yield NBF, enabling visualization of DA protein adducts. Bottom: Depiction of the nIRF properties of ortho quinones which enable the detection of DA protein adducts.

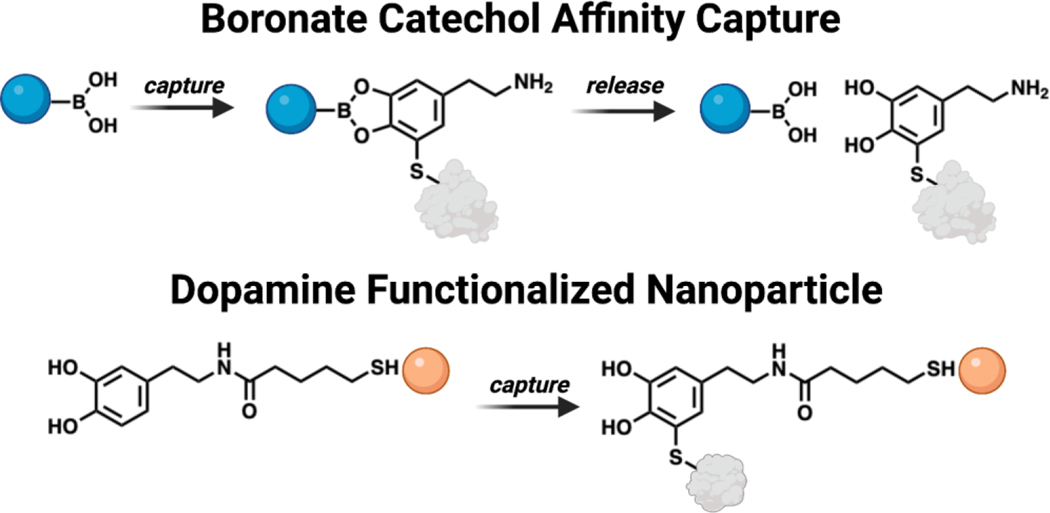

Other tools that utilize the chemical structure of DA to study DA protein adducts enable enrichment and capture of modified proteins (Figure 9). One example is the use of boronate agarose resin, which chelates the cis diols present on DA at alkaline pH and releases them at acidic pH.166 Experimental workflows based on boronate resins has enabled the capture of DA modified parkin in human brain samples and DA metabolites modified by AS in vitro.123, 134 It should be noted that this approach is useful for enriching endogenously DA damaged proteins by any metabolites that retains catechol functionality upon adduction, but is prone to capturing other biological cis diols such as glycosylated proteins as well. Enrichment strategies and other applications of boronate chemistry can be found in the following review.167 Another reported strategy to detect proteins susceptible to DA modification used DA functionalized quantum dots (QDs).168 Covalent attachment of a protein to the DA anchored on the CdTe/ZnS QDs causes a measurable change in the fluorescence intensity of the QDs, which can report levels of adducted protein captured by the nanoparticles. These DA functionalized QDs are cell penetrant and thus can provide a relative measure of the amount of proteins vulnerable to DA modification in a particular cell. However, this approach cannot determine the identity of the adducted proteins.

Figure 9.

Technologies to capture dopamine protein adducts. Top: Schematic of boronate functionalized resin utilized to immobilize and release proteins containing a DA adduct. Bottom: Visualization of DA decorated nanoparticles enabling detection of proteins susceptible to DA modification.

Beyond DA protein adduct detection, there are additional tools to monitor endogenous DA to study DA dynamics in a variety of capacities. Biosensor and chemical sensor tools for DA detection have been recently reviewed.169, 170 These methods rely on the intrinsic chemical reactivity of DA for signal generation. Genetically encoded DA sensors that produce fluorescence upon DA binding have enabled recording DA synaptic dynamics in mice.171, 172 Small molecule chemical sensors have been designed to covalently trap DA which results in measurable fluorescence changes in the sensor molecule which can be used to track DA location in cells. However distinguishing between DA and NE by this approach remains challenging.173 Similar reactivity based DA sensing strategies have also been applied to nanoparticle approaches.174–177 These tools are valuable constituents of the toolbox needed to probe DA dysfunction in PD as they can be applied in animal and cell models of PD.

Analytical chemistry techniques are also invaluable additions to the chemical toolbox focused on studying DA’s involvement in PD. Fast scan cyclic voltammetry is a powerful way to quantify DA concentration and dynamics.178 This electrochemical approach detects the amounts of DA adsorbed onto an electrode by increasing and decreasing the voltage applied and simultaneously measuring the resulting current generated by the oxidation and reduction of the catechol in DA; further details can be found in the following review.179 This methodology has enabled measurement of sub second DA release in vivo and provided valuable insights in how ROS, synaptic vesicle dysfunction, and aging impact PD progression in animal models, but has a low throughput and requires a skilled operator.180–186

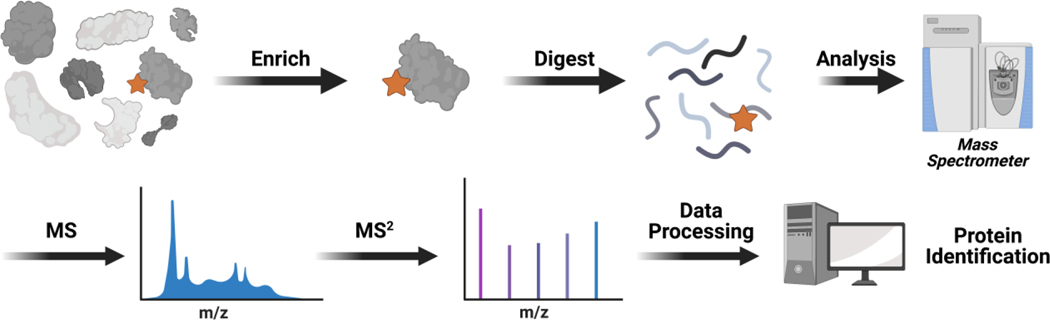

Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) is a powerful analytical tool for studying dysregulated DA in PD. LC-MS is the foundation for any proteomic based study aimed at identifying protein targets of reactive DA metabolites.187 Typically, protocols will enrich DA-adducted proteins from cellular lysates through a variety of methods discussed above or generate DA-protein adducts in vitro by incubating a particular protein of interest with reactive DA metabolites prior to LC-MS analysis. Enrichment of adducted proteins is a key component of such analysis. Often adducts are in low abundance in comparison to unmodified proteins which necessitates enrichment to enable their detection by MS. The enriched pool of DA-protein adducts is commonly digested with a trypsin protease to afford peptide fragments.188 These peptides are separated by a LC system with an in line orbitrap mass analyzer. Inside this type of mass spectrometer, the peptides are fragmented to give a series of Y and B ions, which are deterministic of the parent peptide sequences.189 Sequenced peptides are then searched in various databases to identify their protein of origin.190 An overview of this process is shown in Figure 10. Our laboratory has successfully identified 38 DA-protein adducts in SH-SY5Y cells through such an approach, which led us to discover that reactive DA metabolites modify and functionally inhibit PDI.117 Studies like this improve understanding of how reactive DA metabolites inflict damage across the proteome.

Figure 10.

Identification of dopamine modified proteins by mass spectrometry. Low abundant DA protein adducts are enriched via various strategies (e.g. bioorthogonal chemistry and boronate affinity). This enriched set of proteins is digested to peptides and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis. The MS2 spectra can then be searched against a database to enable protein identification.

The specific sites of DA-protein modification can also be elucidated by LC-MS. A notable example of this is highlighted by Burbulla et al, where a specific DA modification was located on a catalytic Cys residue within the active site of GCase.55 Mapping sites of modification provides valuable information into structural motifs that are susceptible to DA adduction and gives insight into the molecular mechanisms by which reactive DA metabolites impair protein function. However, there are still challenges in comprehensively mapping the specific sites of DA adducts across the proteome, namely ensuring the peptide containing the DA adduct ionizes well and has a m/z within the analysis range of the spectrometer. In such cases, locations of DA modification can be inferred through mutagenesis experiments. In these workflows, the hypothesized adducted amino acid is mutated to a nonreactive sidechain and the mutant protein is assayed to determine if DA adduction still occurs.

Additionally, LC-MS methodology allows for detection of potential PD biomarkers linked to DA dysfunction.191, 192 5-S-cysteinyl-dopamine, a byproduct of reactive DA metabolites coupling with Cys or GSH, has been reported to be elevated with age and in the brains of PD patients.193–195 Thus these DA derived metabolic adducts may have utility as potential PD biomarkers.196

Collectively, there is a large array of chemical tools to study DA. These tools can be leveraged to better understand the roles DA plays in PD progression. Each tool possesses unique advantages and disadvantages that must be kept in mind when designing experiments. The continued expansion and innovation of the DA chemical toolbox will diversify the methodologies researchers have at their disposal to interrogate DA dynamics and will further advance the understanding of functional consequences of DA induced protein damage.

OUTLOOK

PD is a complex and heterogeneous disease. The exact cause of PD remains unknow and there are many competing hypotheses concerning the origins and molecular events that drive PD pathology.197 It is hypothesized that intracellular accumulation of misfolded AS is the main driver of neuronal toxicity and PD development.198–200 There is evidence that misfolded AS originating in the gut can propagate through the gut-brain axis and induce neurodegeneration.201, 202 Other postulated origins for PD are the age dependent buildup of oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and lysosomal impairment.203–206 There are also genetic risk factors that predispose individuals to PD.207, 208 However a majority of PD cases are idiopathic in origin and thus a combination of genetic and environmental factors likely work in concert to influence PD development.202, 209 Additionally, there are particular features that SNc dopaminergic neurons possess which confer vulnerability and predispose them to degradation in PD, such as their long length, low levels of myelination, and high energy consumption.210, 211 Another risk factor for degeneration of these dopaminergic neurons is the presence of DA itself.

The propensity for DA to degrade into reactive metabolites when improperly displaced from vesicular confinement is why DA dysregulation is a potential player in PD. Rogue DA derived electrophilic metabolites react with a host of proteins, which in turn can inhibit the activity of the adducted proteins, and lead to neurotoxicity. Understanding the nuances of these molecular events is important as it provides insights to the multifaceted etiology of PD, which can aid biomarker discovery for early detection and drive therapeutic development.212

Tremendous progress has been made to characterize protein damage caused by reactive DA metabolites. However, there are still many unanswered questions pertaining to DA’s contribution to PD. For instance, what percentage of a particular protein within a cell needs to be modified by DA metabolites to drive a phenotypic response? Answering questions like this are especially important in cases like Nurr1 DA adducts, which can influence gene expression.91 Implementing activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) strategies capable of reporting percent occupancy of an electrophile bound to a particular protein, along with the specific site of modification, would be useful towards this end.213–218 Additionally, controlled and targeted release of DA metabolites to particular proteins and locations in cellular systems would assist in clarifying signaling pathways impacted by DA protein adducts.219, 220 These types of precise chemical tools have been developed to study the consequences of protein damage caused by lipid derived electrophiles like 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) and reactive dicarbonyl metabolites like methylglyoxal (MGO).221–225 Similar DA tools could be built from reported photoactivatable DA precursors.226

Other remaining questions include: how does the abundance of DA-protein adducts change over time and what DA metabolites are most influential in driving neuronal dysfunction? Longitudinal studies tracking the formation and identity of proteins modified by DA metabolites over an organism’s life correlated to PD incidence would provide insight in how DA induced damage contributes to PD. Continued development of tools enabling the enrichment and characterization of DA protein adducts would be valuable assets in this area. Further optimization of LC-MS methodology that comprehensively identifies DA-protein adducts would aid this effort. Harnessing the unique reactivity of ortho quinones may prove useful in enriching DA protein adducts in biological samples through cycloadditions with strained cyclic alkenes.227 Additionally, antibodies raised against particular DA modified proteins are currently lacking and would also be a useful enrichment and detection tool. To determine the pathological contribution of various DA derived metabolites, probes akin to the reported DAyne and 6-OHDA-PEG3-yne could be designed to mimic specific oxidation states of DA metabolites.117, 118 A comprehensive suite of DA derived probe molecules would enable comparative studies between the complex array of different DA metabolites and illuminate their contribution to DA induced protein damage.

To conclude, multiple lines of evidence point to DA dysregulation being a contributor to PD. Reactive DA metabolites can elicit neurotoxicity when they are not properly broken down or when their levels overwhelm natural detoxification machinery. Chemical tools have greatly improved our understanding of DA induced dysfunction. Continued research effort in the area of DA induced protein damage in PD and further expansion of the chemical toolbox needed to study these processes will further elucidate the complex disease etiology of PD.

Funding Sources

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from NIH (R01ES023350, R01CA095039, and R01CA100670). A.K.H. is partially supported by the NIH Chemistry and Biology Interface Training grant T32 GM132029 and the University of Minnesota Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AADC

aromatic acid decarboxylase

- ABPP

activity-based protein profiling

- ADH

alcohol dehydrogenase

- ALDH

aldehyde dehydrogenase

- AR

aldehyde reductases

- AS

alpha synuclein

- COMT

catechol-O-methyltransferase

- DA

dopamine

- DAC

dopaminochrome

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- DAQ

dopamine quinone

- DASQ

dopamine semiquinone

- DβH

dopamine β-hydroxylase

- DHI

5,6-dihydroxyindole

- DHIQ

5,6-dihydroxyindolequinone

- DHPR

dihydropteridine reductase

- DOPAC

3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid

- DOPAL

3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde

- DOPET

3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol

- DPQAL

DOPAL quinone

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FAD

flavin adenine

- GCase

glucocerebrosidase

- GSH

glutathione; dinucleotide

- GST

glutathione-S-transferase

- HVA

homovanillic acid

- HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- LDAC

leukodopaminochrome

- L-DOPA

L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine

- MOA

monoamine oxidase (MAO)

- MGO

methylglyoxal

- MOPAL

3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl acetaldehyde

- MPTP

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MTY

3-methoxytyramine

- NBF

nitroblue formazan

- NBT

nitroblue tetrazolium

- NE

norepinephrine

- nIRF

near-infrared fluorescence

- Nurr1

nuclear receptor related-1

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PDI

protein disulfide isomerase

- QDs

quantum dots

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SNc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- SOD2

superoxide dismutase 2

- TGM2

transglutaminase 2

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- VMAT2

Vesicular monoamine transporter 2

Biographies

Alexander K. Hurben is currently a Ph.D. candidate in the Medicinal Chemistry program at the University of Minnesota under the supervision of Professor Natalia Y. Tretyakova. He received his B.S. in Chemistry from the University of Minnesota where he synthesized chemical probes to study protein prenylation in Professor Mark Distefano’s group. His current research focuses on the development of chemical tools to study non-enzymatic posttranslational modifications caused by endogenous electrophilic metabolites to better understand their role in disease and cell signaling.

Natalia Y. Tretyakova is a Distinguished McKnight University professor of Medicinal Chemistry at the College of Pharmacy and the Masonic Cancer Center at the University of Minnesota- Twin Cities. She is also the Founding Director of the University of Minnesota Epigenetics Consortium and Chair of the ACS Division of Chemical Toxicology. The Tretyakova research program is on the interface of nucleic acid chemistry, chemical carcinogenesis, and bioanalytical chemistry. She is employing the tools of chemical biology, analytical chemistry, and biochemistry to investigate the chemistry and biology of DNA and protein damage by exogenous and endogenous chemicals, to determine the modes of action of anti-tumor drugs, and to develop novel nucleoside analogs as molecular probes and biologically active compounds.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Dorsey ER; Elbaz A; Nichols E; Abbasi N; Abd-Allah F; Abdelalim A; Adsuar JC; Ansha MG; Brayne C; Choi J-YJ; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17 (11), 939–953. DOI: 10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30295-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Dickson DW Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism: Neuropathology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2 (8). DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Poewe W; Seppi K; Tanner CM; Halliday GM; Brundin P; Volkmann J; Schrag AE; Lang AE Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17013. DOI: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kordower JH; Olanow CW; Dodiya HB; Chu Y; Beach TG; Adler CH; Halliday GM; Bartus RT Disease duration and the integrity of the nigrostriatal system in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2013, 136 (8), 2419–2431. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awt192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Stokes AH; Hastings TG; Vrana KE Cytotoxic and genotoxic potential of dopamine. J. Neurosci. Res 1999, 55 (6), 659–665. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Carlsson A; Lindqvist M; Magnusson T; Waldeck B On the presence of 3-hydroxytyramine in brain. Science 1958, 127 (3296), 471–471. DOI: 10.1126/science.127.3296.471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Iversen SD; Iversen LL Dopamine: 50 years in perspective. Trends Neurosci. 2007, 30 (5), 188–193. DOI: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Bucolo C; Leggio GM; Drago F; Salomone S Dopamine outside the brain: The eye, cardiovascular system and endocrine pancreas. Pharmacol. Ther 2019, 203, 107392. DOI: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ehringer H; Hornykiewicz O [Distribution of noradrenaline and dopamine (3-hydroxytyramine) in the human brain and their behavior in diseases of the extrapyramidal system]. Klin. Wochenschr 1960, 38, 1236–1239. DOI: 10.1007/bf01485901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Cotzias GC; Van Woert MH; Schiffer LM Aromatic amino acids and modification of parkinsonism. N. Engl. J. Med 1967, 276 (7), 374–379. DOI: 10.1056/nejm196702162760703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Fahn S; Oakes D; Shoulson I; Kieburtz K; Rudolph A; Lang A; Olanow CW; Tanner C; Marek K Levodopa and the progression of Parkinson’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med 2004, 351 (24), 2498–2508. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa033447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Mosharov EV; Borgkvist A; Sulzer D Presynaptic effects of levodopa and their possible role in dyskinesia. Mov. Disord 2015, 30 (1), 45–53. DOI: 10.1002/mds.26103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Cilia R; Akpalu A; Sarfo FS; Cham M; Amboni M; Cereda E; Fabbri M; Adjei P; Akassi J; Bonetti A; et al. The modern pre-levodopa era of Parkinson’s disease: insights into motor complications from sub-Saharan Africa. Brain 2014, 137 (Pt 10), 2731–2742. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awu195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Olanow CW Levodopa: Effect on cell death and the natural history of Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord 2015, 30 (1), 37–44. DOI: 10.1002/mds.26119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Monzani E; Nicolis S; Dell’Acqua S; Capucciati A; Bacchella C; Zucca FA; Mosharov EV; Sulzer D; Zecca L; Casella L Dopamine, oxidative stress and protein–quinone modifications in Parkinson’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58 (20), 6512–6527. DOI: 10.1002/anie.201811122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Eisenhofer G; Kopin IJ; Goldstein DS Catecholamine metabolism: A contemporary view with implications for physiology and medicine. Pharmacol. Rev 2004, 56 (3), 331–349. DOI: 10.1124/pr.56.3.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Casida JE; Ford B; Jinsmaa Y; Sullivan P; Cooney A; Goldstein DS Benomyl, aldehyde dehydrogenase, DOPAL, and the catecholaldehyde hypothesis for the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2014, 27 (8), 1359–1361. DOI: 10.1021/tx5002223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Daubner SC; Le T; Wang S Tyrosine hydroxylase and regulation of dopamine synthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 2011, 508 (1), 1–12. DOI: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Montioli R; Cellini B; Dindo M; Oppici E; Voltattorni CB Interaction of human dopa decarboxylase with L-Dopa: Spectroscopic and kinetic studies as a function of pH. Biomed. Res. Int 2013, 2013, 1–10. DOI: 10.1155/2013/161456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Vendelboe TV; Harris P; Zhao Y; Walter TS; Harlos K; El Omari K; Christensen HE The crystal structure of human dopamine β-hydroxylase at 2.9 Å resolution. Sci. Adv 2016, 2 (4), e1500980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Edmondson DE; Mattevi A; Binda C; Li M; Hubalek F Structure and mechanism of monoamine oxidase. Curr. Med. Chem 2004, 11 (15), 1983–1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Graves SM; Xie Z; Stout KA; Zampese E; Burbulla LF; Shih JC; Kondapalli J; Patriarchi T; Tian L; Brichta L; et al. Dopamine metabolism by a monoamine oxidase mitochondrial shuttle activates the electron transport chain. Nat. Neurosci 2020, 23 (1), 15–20. DOI: 10.1038/s41593-019-0556-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Grünblatt E; Riederer P Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm 2016, 123 (2), 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Vidgren J; Svensson LA; Liljas A Crystal structure of catechol O-methyltransferase. Nature 1994, 368 (6469), 354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Lambert G; Eisenhofer G; Jennings G; Esler M Regional homovanillic acid production in humans. Life Sci. 1993, 53 (1), 63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Meiser J; Weindl D; Hiller K Complexity of dopamine metabolism. Cell Commun. Signal 2013, 11 (1), 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Elsworth JD; Roth RH Dopamine synthesis, uptake, metabolism, and receptors: Relevance to gene therapy of Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol 1997, 144 (1), 4–9. DOI: 10.1006/exnr.1996.6379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Jinsmaa Y; Florang VR; Rees JN; Anderson DG; Strack S; Doorn JA Products of oxidative stress inhibit aldehyde oxidation and reduction pathways in dopamine catabolism yielding elevated levels of a reactive intermediate. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2009, 22 (5), 835–841. DOI: 10.1021/tx800405v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Maardh G; Vallee BL Human class I alcohol dehydrogenases catalyze the interconversion of alcohols and aldehydes in the metabolism of dopamine. Biochemistry 1986, 25 (23), 7279–7282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Eiden LE; Schäfer MK-H; Weihe E; Schütz B The vesicular amine transporter family (SLC18): Amine/proton antiporters required for vesicular accumulation and regulated exocytotic secretion of monoamines and acetylcholine. Pflügers Arch. 2004, 447 (5), 636–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Mulvihill KG Presynaptic regulation of dopamine release: Role of the DAT and VMAT2 transporters. Neurochem. Int 2019, 122, 94–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Lohr KM; Masoud ST; Salahpour A; Miller GW Membrane transporters as mediators of synaptic dopamine dynamics: Implications for disease. Eur. J. Neurosci 2017, 45 (1), 20–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Blakely RD; Edwards RH Vesicular and plasma membrane transporters for neurotransmitters. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 2012, 4 (2), a005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Staal RG; Mosharov EV; Sulzer D Dopamine neurons release transmitter via a flickering fusion pore. Nat. Neurosci 2004, 7 (4), 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Omiatek DM; Bressler AJ; Cans A-S; Andrews AM; Heien ML; Ewing AG The real catecholamine content of secretory vesicles in the CNS revealed by electrochemical cytometry. Sci. Rep 2013, 3 (1), 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Hovde MJ; Larson GH; Vaughan RA; Foster JD Model systems for analysis of dopamine transporter function and regulation. Neurochem. Int 2019, 123, 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Zecca L; Tampellini D; Gerlach M; Riederer P; Fariello R; Sulzer D Substantia nigra neuromelanin: Structure, synthesis, and molecular behaviour. Mol. Pathol 2001, 54 (6), 414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Zhang S; Wang R; Wang G Impact of dopamine oxidation on dopaminergic neurodegeneration. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2018, 10 (2), 945–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Galzigna L; De Iuliis A; Zanatta L Enzymatic dopamine peroxidation in substantia nigra of human brain. Clin. Chim. Acta 2000, 300 (1–2), 131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Hastings TG Enzymatic oxidation of dopamine: The role of prostaglandin H synthase. J. Neurochem 1995, 64 (2), 919–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Senoh S; Witkop B Formation and rearrangements of aminochromes from a new metabolite of dopamine and some of its derivatives1. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1959, 81 (23), 6231–6235. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Segura‐Aguilar J; Paris I; Muñoz P; Ferrari E; Zecca L; Zucca FA Protective and toxic roles of dopamine in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem 2014, 129 (6), 898–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Napolitano A; Crescenzi O; Pezzella A; Prota G Generation of the neurotoxin 6-hydroxydopamine by peroxidase/H2O2 oxidation of dopamine. J. Med. Chem 1995, 38 (6), 917–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Pezzella A; d’Ischia M; Napolitano A; Misuraca G; Prota G Iron-mediated generation of the neurotoxin 6-hydroxydopamine quinone by reaction of fatty acid hydroperoxides with dopamine: A possible contributory mechanism for neuronal degeneration in Parkinson’s disease. J. Med. Chem 1997, 40 (14), 2211–2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Bisaglia M; Mammi S; Bubacco L Kinetic and structural analysis of the early oxidation products of dopamine: Analysis of the interactions with α-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem 2007, 282 (21), 15597–15605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Sulzer D; Bogulavsky J; Larsen KE; Behr G; Karatekin E; Kleinman MH; Turro N; Krantz D; Edwards RH; Greene LA Neuromelanin biosynthesis is driven by excess cytosolic catecholamines not accumulated by synaptic vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2000, 97 (22), 11869–11874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Anderson DG; Mariappan SS; Buettner GR; Doorn JA Oxidation of 3, 4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, a toxic dopaminergic metabolite, to a semiquinone radical and an ortho-quinone. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286 (30), 26978–26986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Bisaglia M; Greggio E; Beltramini M; Bubacco L Dysfunction of dopamine homeostasis: Clues in the hunt for novel Parkinson’s disease therapies. FASEB J. 2013, 27 (6), 2101–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Caudle WM; Colebrooke RE; Emson PC; Miller GW Altered vesicular dopamine storage in Parkinson’s disease: A premature demise. Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31 (6), 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Pifl C; Rajput A; Reither H; Blesa J; Cavada C; Obeso JA; Rajput AH; Hornykiewicz O Is Parkinson’s disease a vesicular dopamine storage disorder? Evidence from a study in isolated synaptic vesicles of human and nonhuman primate striatum. J. Neurosci 2014, 34 (24), 8210–8218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Asanuma M; Miyazaki I; Ogawa N Dopamine-or L-DOPA-induced neurotoxicity: The role of dopamine quinone formation and tyrosinase in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurotox. Res 2003, 5 (3), 165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Miyazaki I; Asanuma M Dopaminergic neuron-specific oxidative stress caused by dopamine itself. Acta Med. Okayama 2008, 62 (3), 141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Lohr KM; Bernstein AI; Stout KA; Dunn AR; Lazo CR; Alter SP; Wang M; Li Y; Fan X; Hess EJ Increased vesicular monoamine transporter enhances dopamine release and opposes Parkinson disease-related neurodegeneration in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2014, 111 (27), 9977–9982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Glatt CE; Wahner AD; White DJ; Ruiz-Linares A; Ritz B Gain-of-function haplotypes in the vesicular monoamine transporter promoter are protective for Parkinson disease in women. Hum. Mol. Genet 2006, 15 (2), 299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Burbulla LF; Song P; Mazzulli JR; Zampese E; Wong YC; Jeon S; Santos DP; Blanz J; Obermaier CD; Strojny C Dopamine oxidation mediates mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Science 2017, 357 (6357), 1255–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Sulzer D Multiple hit hypotheses for dopamine neuron loss in Parkinson’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2007, 30 (5), 244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Hirsch E; Brandel JP; Galle P; Javoy‐Agid F; Agid Y Iron and aluminum increase in the substantia nigra of patients with Parkinson’s disease: An X‐ray microanalysis. J. Neurochem 1991, 56 (2), 446–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Dexter D; Wells F; Lee A; Agid F; Agid Y; Jenner P; Marsden C Increased nigral iron content and alterations in other metal ions occurring in brain in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem 1989, 52 (6), 1830–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Sofic E; Riederer P; Heinsen H; Beckmann H; Reynolds G; Hebenstreit G; Youdim M Increased iron (III) and total iron content in post mortem substantia nigra of parkinsonian brain. J. Neural Transm. 1988, 74 (3), 199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Jenner P; Dexter D; Sian J; Schapira A; Marsden C Oxidative stress as a cause of nigral cell death in Parkinson’s disease and incidental Lewy body disease. Ann. Neurol 1992, 32 (S1), S82–S87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Hare DJ; Double KL Iron and dopamine: a toxic couple. Brain 2016, 139 (4), 1026–1035. DOI: 10.1093/brain/aww022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Smeyne M; Smeyne RJ Glutathione metabolism and Parkinson’s disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med 2013, 62, 13–25. DOI: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Ballatori N; Krance SM; Notenboom S; Shi S; Tieu K; Hammond CL Glutathione dysregulation and the etiology and progression of human diseases. Biol. Chem 2009, 390 (3), 191–214. DOI: 10.1515/bc.2009.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Cobley JN; Fiorello ML; Bailey DM 13 reasons why the brain is susceptible to oxidative stress. Redox. Biol 2018, 15, 490–503. DOI: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Goldstein DS; Kopin IJ; Sharabi Y Catecholamine autotoxicity. Implications for pharmacology and therapeutics of Parkinson disease and related disorders. Pharmacol. Ther 2014, 144 (3), 268–282. DOI: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Hastings TG; Lewis DA; Zigmond MJ Role of oxidation in the neurotoxic effects of intrastriatal dopamine injections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 1996, 93 (5), 1956–1961. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Bisaglia M; Filograna R; Beltramini M; Bubacco L Are dopamine derivatives implicated in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease? Ageing Res. Rev 2014, 13, 107–114. DOI: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Graham DG Oxidative pathways for catecholamines in the genesis of neuromelanin and cytotoxic quinones. Mol. Pharmacol 1978, 14 (4), 633–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Terland O; Almås B; Flatmark T; Andersson KK; Sørlie M One-electron oxidation of catecholamines generates free radicals with an in vitro toxicity correlating with their lifetime. Free Radic. Biol. Med 2006, 41 (8), 1266–1271. DOI: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Kalyanaraman B; Premovic PI; Sealy RC Semiquinone anion radicals from addition of amino acids, peptides, and proteins to quinones derived from oxidation of catechols and catecholamines. An ESR spin stabilization study. J. Biol. Chem 1987, 262 (23), 11080–11087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Tse DC; McCreery RL; Adams RN Potential oxidative pathways of brain catecholamines. J. Med. Chem 1976, 19 (1), 37–40. DOI: 10.1021/jm00223a008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Jameson GN; Zhang J; Jameson RF; Linert W Kinetic evidence that cysteine reacts with dopaminoquinone via reversible adduct formation to yield 5-cysteinyl-dopamine: an important precursor of neuromelanin. Org. Biomol. Chem 2004, 2 (5), 777–782. DOI: 10.1039/b316294j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Li Y; Jongberg S; Andersen ML; Davies MJ; Lund MN Quinone-induced protein modifications: Kinetic preference for reaction of 1,2-benzoquinones with thiol groups in proteins. Free Radic. Biol. Med 2016, 97, 148–157. DOI: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Xu R; Huang X; Kramer KJ; Hawley MD Characterization of products from the reactions of dopamine quinone with N-acetylcysteine. Bioorganic Chem. 1996, 24 (1), 110–126. DOI: 10.1006/bioo.1996.0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Alfieri ML; Cariola A; Panzella L; Napolitano A; d’Ischia M; Valgimigli L; Crescenzi O Disentangling the puzzling regiochemistry of thiol addition to o-quinones. J. Org. Chem 2022, 87 (7), 4580–4589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Labenski MT; Fisher AA; Lo H-H; Monks TJ; Lau SS Protein electrophile-binding motifs: Lysine-rich proteins are preferential targets of quinones. Drug Metab. Dispos 2009, 37 (6), 1211–1218. DOI: 10.1124/dmd.108.026211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Xu R; Huang X; Morgan TD; Prakash O; Kramer KJ; Hawley MD Characterization of products from the reactions of N-acetyldopamine quinone with N-acetylhistidine. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 1996, 329 (1), 56–64. DOI: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Nicolis S; Zucchelli M; Monzani E; Casella L Myoglobin modification by enzyme-generated dopamine reactive species. Chem. Eur. J 2008, 14 (28), 8661–8673. DOI: 10.1002/chem.200801014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Marchitti SA; Deitrich RA; Vasiliou V Neurotoxicity and metabolism of the catecholamine-derived 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycolaldehyde: The role of aldehyde dehydrogenase. Pharmacol. Rev 2007, 59 (2), 125–150. DOI: 10.1124/pr.59.2.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Goldstein DS; Sullivan P; Holmes C; Miller GW; Alter S; Strong R; Mash DC; Kopin IJ; Sharabi Y Determinants of buildup of the toxic dopamine metabolite DOPAL in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem 2013, 126 (5), 591–603. DOI: 10.1111/jnc.12345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Ramanujam V; Charlier C; Bax A Observation and kinetic characterization of transient Schiff base intermediates by CEST NMR spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58 (43), 15309–15312. DOI: 10.1002/anie.201908416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Follmer C; Coelho-Cerqueira E; Yatabe-Franco DY; Araujo GDT; Pinheiro AS; Domont GB; Eliezer D Oligomerization and membrane-binding properties of covalent adducts formed by the interaction of α-synuclein with the toxic dopamine metabolite 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL). J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290 (46), 27660–27679. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.m115.686584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Rees JN; Florang VR; Eckert LL; Doorn JA Protein reactivity of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, a toxic dopamine metabolite, is dependent on both the aldehyde and the catechol. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2009, 22 (7), 1256–1263. DOI: 10.1021/tx9000557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Werner-Allen JW; Dumond JF; Levine RL; Bax A Toxic dopamine metabolite dopal forms an unexpected dicatechol pyrrole adduct with lysines of α-synuclein. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55 (26), 7374–7378. DOI: 10.1002/anie.201600277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Kuhn DM; Arthur R Jr. Dopamine inactivates tryptophan hydroxylase and forms a redox-cycling quinoprotein: possible endogenous toxin to serotonin neurons. J. Neurosci 1998, 18 (18), 7111–7117. DOI: 10.1523/jneurosci.18-18-07111.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Xu Y; Stokes AH; Roskoski R Jr.; Vrana KE Dopamine, in the presence of tyrosinase, covalently modifies and inactivates tyrosine hydroxylase. J. Neurosci. Res 1998, 54 (5), 691–697. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Kuhn DM; Arthur RE; Thomas DM; Elferink LA Tyrosine hydroxylase is inactivated by catechol-quinones and converted to a redox-cycling quinoprotein. J. Neurochem 2001, 73 (3), 1309–1317. DOI: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Whitehead RE; Ferrer JV; Javitch JA; Justice JB Reaction of oxidized dopamine with endogenous cysteine residues in the human dopamine transporter. J. Neurochem 2001, 76 (4), 1242–1251. DOI: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00125.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Armarego WL; Waring P Inhibition of human brain dihydropteridine reductase [EC 1.6. 99.10] by the oxidation products of catecholamines, the aminochromes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm 1983, 113 (3), 895–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Lockyer J; Cook RG; Milstien S; Kaufman S; Woo SL; Ledley FD Structure and expression of human dihydropteridine reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 1987, 84 (10), 3329–3333. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Bruning JM; Wang Y; Oltrabella F; Tian B; Kholodar SA; Liu H; Bhattacharya P; Guo S; Holton JM; Fletterick RJ; et al. Covalent modification and regulation of the nuclear receptor Nurr1 by a dopamine metabolite. Cell Chem. Biol 2019, 26 (5), 674–685.e676. DOI: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2019.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Zetterstrom RH; Solomin L; Jansson L; Hoffer BJ; Olson L; Perlmann T Dopamine neuron agenesis in Nurr1-deficient mice. Science 1997, 276 (5310), 248–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Kadkhodaei B; Ito T; Joodmardi E; Mattsson B; Rouillard C; Carta M; Muramatsu SI; Sumi-Ichinose C; Nomura T; Metzger D; et al. Nurr1 Is required for maintenance of maturing and adult midbrain dopamine neurons. J. Neurosci 2009, 29 (50), 15923–15932. DOI: 10.1523/jneurosci.3910-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Decressac M; Volakakis N; Björklund A; Perlmann T NURR1 in Parkinson disease—from pathogenesis to therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Neurol 2013, 9 (11), 629–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (95).Iwawaki T; Kohno K; Kobayashi K Identification of a potential nurr1 response element that activates the tyrosine hydroxylase gene promoter in cultured cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm 2000, 274 (3), 590–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (96).Hermanson E; Joseph B; Castro D; Lindqvist E; Aarnisalo P; Wallén Å; Benoit G; Hengerer B; Olson L; Perlmann T Nurr1 regulates dopamine synthesis and storage in MN9D dopamine cells. Exp. Cell Res 2003, 288 (2), 324–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (97).Sacchetti P; Mitchell TR; Granneman JG; Bannon MJ Nurr1 enhances transcription of the human dopamine transporter gene through a novel mechanism. J. Neurochem 2001, 76 (5), 1565–1572. DOI: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (98).Berman SB; Hastings TG Dopamine oxidation alters mitochondrial respiration and induces permeability transition in brain mitochondria. J. Neurochem 2001, 73 (3), 1127–1137. DOI: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731127.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (99).Khan FH; Sen T; Maiti AK; Jana S; Chatterjee U; Chakrabarti S Inhibition of rat brain mitochondrial electron transport chain activity by dopamine oxidation products during extended in vitro incubation: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1741 (1–2), 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (100).Belluzzi E; Bisaglia M; Lazzarini E; Tabares LC; Beltramini M; Bubacco L Human SOD2 modification by dopamine quinones affects enzymatic activity by promoting its aggregation: Possible implications for Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7 (6), e38026. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (101).Johnson F; Giulivi C Superoxide dismutases and their impact upon human health. Mol. Aspects Med 2005, 26 (4–5), 340–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (102).Melov S; Coskun P; Patel M; Tuinstra R; Cottrell B; Jun AS; Zastawny TH; Dizdaroglu M; Goodman SI; Huang TT; et al. Mitochondrial disease in superoxide dismutase 2 mutant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 1999, 96 (3), 846–851. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (103).Hauser DN; Dukes AA; Mortimer AD; Hastings TG Dopamine quinone modifies and decreases the abundance of the mitochondrial selenoprotein glutathione peroxidase 4. Free Radic. Biol. Med 2013, 65, 419–427. DOI: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.06.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (104).Cardoso BR; Hare DJ; Bush AI; Roberts BR Glutathione peroxidase 4: A new player in neurodegeneration? Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22 (3), 328–335. DOI: 10.1038/mp.2016.196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (105).Biosa A; Arduini I; Soriano ME; Giorgio V; Bernardi P; Bisaglia M; Bubacco L Dopamine oxidation products as mitochondrial endotoxins, a potential molecular mechanism for preferential neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2018, 9 (11), 2849–2858. DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (106).Crawford RA; Bowman KR; Cagle BS; Doorn JA In vitro inhibition of glutathione-S-transferase by dopamine and its metabolites, 3, 4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde and 3, 4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid. Neurotoxicology 2021, 86, 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (107).Strange RC; Spiteri MA; Ramachandran S; Fryer AA Glutathione-S-transferase family of enzymes. Mutat. Res 2001, 482 (1–2), 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (108).Whitworth AJ; Theodore DA; Greene JC; Benes H; Wes PD; Pallanck LJ Increased glutathione S-transferase activity rescues dopaminergic neuron loss in a Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2005, 102 (22), 8024–8029. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0501078102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (109).Hirrlinger J; Schulz JB; Dringen R Effects of dopamine on the glutathione metabolism of cultured astroglial cells: Implications for Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem 2002, 82 (3), 458–467. DOI: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01013.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (110).Walter P; Ron D The unfolded protein response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. science 2011, 334 (6059), 1081–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (111).Perri ER; Thomas CJ; Parakh S; Spencer DM; Atkin JD The unfolded protein response and the role of protein disulfide isomerase in neurodegeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol 2016, 3, 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (112).Ryu EJ; Harding HP; Angelastro JM; Vitolo OV; Ron D; Greene LA Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response in cellular models of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci 2002, 22 (24), 10690–10698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (113).Yoshida H ER stress and diseases. FEBS J. 2007, 274 (3), 630–658. DOI: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (114).Yamamuro A; Yoshioka Y; Ogita K; Maeda S Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress on the cell death induced by 6-hydroxydopamine in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neurochem. Res 2006, 31 (5), 657–664. DOI: 10.1007/s11064-006-9062-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (115).Wilkinson B; Gilbert HF Protein disulfide isomerase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1699 (1–2), 35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (116).Muller C; Bandemer J; Vindis C; Camaré C; Mucher E; Guéraud F; Larroque-Cardoso P; Bernis C; Auge N; Salvayre R Protein disulfide isomerase modification and inhibition contribute to ER stress and apoptosis induced by oxidized low density lipoproteins. Antioxid. Redox. Signal 2013, 18 (7), 731–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (117).Hurben AK; Erber LN; Tretyakova NY; Doran TM Proteome-wide profiling of cellular targets modified by dopamine metabolites using a bio-orthogonally functionalized catecholamine. ACS Chem. Biol 2021, 16 (11), 2581–2594. DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.1c00629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (118).Farzam A; Chohan K; Strmiskova M; Hewitt SJ; Park DS; Pezacki JP; Özcelik D A functionalized hydroxydopamine quinone links thiol modification to neuronal cell death. Redox. Biol 2020, 28, 101377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (119).Stefanis L α-Synuclein in Parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 2012, 2 (2), a009399-a009399. DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (120).Krüger R; Kuhn W; Müller T; Woitalla D; Graeber M; Kösel S; Przuntek H; Epplen JT; Schols L; Riess O AlaSOPro mutation in the gene encoding α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Genet 1998, 18 (2), 106–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (121).Spillantini MG; Schmidt ML; Lee VMY; Trojanowski JQ; Jakes R; Goedert M α-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 1997, 388 (6645), 839–840. DOI: 10.1038/42166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (122).Spillantini MG; Crowther RA; Jakes R; Hasegawa M; Goedert M α-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 1998, 95 (11), 6469–6473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (123).Bisaglia M; Tosatto L; Munari F; Tessari I; de Laureto PP; Mammi S; Bubacco L Dopamine quinones interact with α-synuclein to form unstructured adducts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm 2010, 394 (2), 424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (124).Lee H-J; Baek SM; Ho D-H; Suk J-E; Cho E-D; Lee S-J Dopamine promotes formation and secretion of non-fibrillar alpha-synuclein oligomers. Exp. Mol. Med 2011, 43 (4), 216. DOI: 10.3858/emm.2011.43.4.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (125).Norris EH; Giasson BI; Hodara R; Xu S; Trojanowski JQ; Ischiropoulos H; Lee VMY Reversible inhibition of α-synuclein fibrillization by dopaminochrome-mediated conformational alterations. J. Biol. Chem 2005, 280 (22), 21212–21219. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.m412621200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (126).Burke WJ; Kumar VB; Pandey N; Panneton WM; Gan Q; Franko MW; O’Dell M; Li SW; Pan Y; Chung HD; et al. Aggregation of α-synuclein by DOPAL, the monoamine oxidase metabolite of dopamine. Acta Neuropathol. 2008, 115 (2), 193–203. DOI: 10.1007/s00401-007-0303-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (127).Plotegher N; Berti G; Ferrari E; Tessari I; Zanetti M; Lunelli L; Greggio E; Bisaglia M; Veronesi M; Girotto S; et al. DOPAL derived α-synuclein oligomers impair synaptic vesicles physiological function. Sci. Rep 2017, 7 (1), 40699. DOI: 10.1038/srep40699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]