Abstract

Introduction:

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is known to be a trigger for asthma exacerbation. However, little is known about the role of seasonal variation in indoor and outdoor NO2 levels in childhood asthma in a mixed rural-urban setting of North America.

Methods:

This prospective cohort study, as a feasibility study, included 62 families with children (5-17 years) that had diagnosed persistent asthma residing in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Indoor and outdoor NO2 concentrations were measured using passive air samples over 2 weeks in winter and 2 weeks in summer. We assessed seasonal variation in NO2 levels in urban and rural residential areas and the association with asthma control status collected from participants’ asthma diaries during the study period.

Results:

Outdoor NO2 levels were lower (median: 2.4 parts per billion (ppb) in summer, 3.9 ppb in winter) than the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) annual standard (53 ppb). In winter, a higher level of outdoor NO2 was significantly associated with urban residential living area (P = .014) and lower socioeconomic status (SES) (P = .027). For both seasons, indoor NO2 was significantly higher (P < .05) in rural versus urban areas and in homes with gas versus electric stoves (P < .05). Asthma control status was not associated with level of indoor or outdoor NO2 in this cohort.

Conclusions:

NO2 levels were low in this mixed rural-urban community and not associated with asthma control status in this small feasibility study. Further research with a larger sample size is warranted for defining a lower threshold of NO2 concentration with health effect on asthma in mixed rural-urban settings.

Keywords: NO2, gas stove, socioeconomic status, air quality, rural, urban

Introduction

Evidence indicates that exposure to nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is significantly associated with asthma incidence and poorer health outcomes in the United States (U.S.) and elsewhere.1-8 Prospective studies examining the association between NO2 and childhood asthma have been conducted largely in urban communities where traffic volume, level of NO2, and asthma prevalence are higher than in rural or mixed rural-urban areas.3,4,9 Indoor and outdoor NO2 exposure levels were assessed among children with asthma living in urban and suburban Connecticut and Massachusetts, and significant associations were found between increased levels of indoor NO2 (above 6 parts per billion (ppb)) and asthma symptoms and severity, at levels well below the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) outdoor standards (53 ppb). 10 These observations indicate an NO2 concentration below the EPA standard might still pose a significant health effect to people with asthma, which is yet unknown whether this is the case for non-urban settings.

Olmsted County, Minnesota (MN), was rated as having excellent air quality by the American Lung Association in 2014 based on the level of ambient ozone. 11 However, the prevalence of current asthma in school age children is 13%, which exceeds the national average (8%).12,13 Given the high prevalence of asthma in this mixed rural-urban area, the reported health effect of low NO2 concentration on asthma, and a relatively long and cold winter season in our study setting, it is worthy of exploring factors associated with residential NO2 concentrations (eg, indoors from gas stove or oven, unvented gas fireplaces; and outdoors from traffic and combustion from electric power plants) and the health effect of exposure to NO2. 14 Measuring and assessing the health effect of indoor and outdoor NO2 concentrations in a mixed rural-urban setting in a Midwest region may help us better define a lower threshold of NO2 concentrations with health effect.15,16 Further, given increasing traffic volume and population within Olmsted County, associated with the multi-year $5.6 billion economic development initiative, it would be worthy of assessing the health effect of indoor and outdoor NO2 concentrations. 17

Our aim was to test if it is feasible to measure residential levels of outdoor and indoor NO2, describe residential characteristics related to spatial and seasonal variations in NO2, and explore associations of residential NO2 exposure with respiratory outcomes among a group of pediatric patients with persistent asthma.

Methods

Study Setting and Population

Olmsted County, MN (area: 1700 km2, population: 156,277 in 2018) contains both urban and rural areas as defined by the United States Census (16% rural population and 91% rural area), 18 and it is demographically similar to the surrounding Midwest region, with the exception that a large proportion of the population is employed in the health care field.19-21 Olmsted County currently has a single monitoring site which measures PM2.5 and ozone concentration but not NO2. Previous studies showed that the prevalence of asthma among children and adolescents in Olmsted County, MN, in 2000 was higher than national average (13%vs 8% at the national level) and asthma was the third highest health care expenditure in children and adolescents in Olmsted County, MN.12,13,22

Study Design

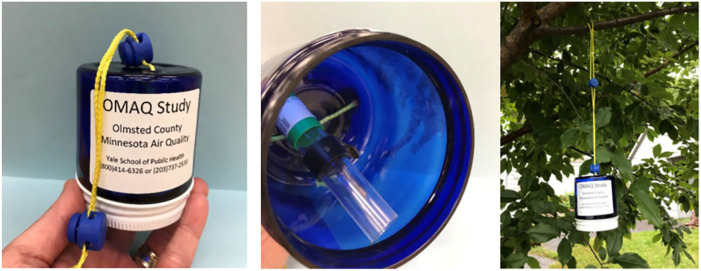

This is a single site prospective cohort study conducted at the Mayo Clinic with a collaboration with the Center for Perinatal, Pediatric, and Environmental Epidemiology, Yale School of Public Health. Informed consent was obtained from Mayo Clinic pediatric primary care patients with persistent asthma residing in Olmsted County (n = 62). We assessed their indoor and outdoor NO2 levels for a total of 4 weeks (2 in winter and 2 in summer) using passive monitors (Palmes tube),23,24 (Figure 1) and collected asthma outcomes during the same period. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mayo Clinic and the Human Investigation Committee of Yale University.

Figure 1.

Photograph of an NO2 monitor (Palmes tube) clipped to blue plastic weather protector jar and suspended from a tree branch in the backyard of a home. Unexposed end of the Palmes tube within the protector jar is sealed (green cap with white sample label), and screen lid is replaced and screwed on tightly.

Study Cohort

All eligible study cohort participants were Mayo Clinic pediatric primary care patients aged 5 to 17 years who (1) had at least one clinic visit to Mayo Clinic Rochester between 8/1/2015 and 1/31/2019, (2) had a documented physician diagnosis of persistent asthma from clinical notes, 25 (3) currently using controller medication(s) (eg, inhaled corticosteroid), and (4) resided at an address in Olmsted County, MN (n = 947). An invitation letter was sent to these families who, upon indicating interest in the study, were screened by phone interview to check inclusion and exclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria included those who did not have a protocol-acceptable setting for the monitor at least 10 feet away from their residence (for outdoor NO2), non-English speaking, and where the child with asthma was not in the home a minimum of 5 days per week, or had other chronic lung conditions (eg, cystic fibrosis).

Measurement of Indoor and Outdoor NO2 and Collection of Asthma Outcomes

We followed the protocol and methods for measuring indoor and outdoor NO2 previously established for environmental studies in an urban setting by the Yale University study team. 10 A study materials kit was mailed to each family who agreed to participate. Each participant received an initial kit for the winter season followed by a second kit for the summer measurement period. Each kit included 2 NO2 samplers (one for indoor placement and one for outdoors (Figure 1),23,24 a stand for hanging the indoor NO2 sampler, a small plastic open-ended jar to serve as a weather shield for the outdoor monitor, a set of installation instructions, and an asthma diary for recording asthma symptoms. A study coordinator placed a follow-up phone call to families to facilitate proper placement of the passive air samplers and conduct a structured interview collecting baseline information (eg, presence of gas stove). Following each 2-week monitoring period (2 weeks in winter and 2 weeks in summer, for a total of 4 weeks per residence to capture seasonal variability), the study coordinator contacted the families by phone to arrange for removal and return of the samplers. A 2-week integrated average NO2 (ppb) concentration was determined for each period, indoors and outdoors, for each residence.

Asthma Control Status

The parent or guardian of the participant was instructed to record the following information on the asthma diary: (1) asthma day and night symptoms (eg, wheezing, persistent cough, chest tightness, and limited activities), and (2) asthma rescue medication use (eg, albuterol). At the time of each NO2 monitor take-down interview they were asked to refer to the asthma diary to answer questions. With the collected data from participants, an asthma control status, based on the 2007 National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guideline, was constructed for data analysis. 26 The score of asthma control status consisted of 3 components collected: symptom steps (day and night) and rescue medication steps. We defined the score of asthma control status as well-controlled (Score 1: ≤2 daytime asthma symptoms/week, ≤1 nighttime asthma symptom/month, or ≤2 rescue medication use/week), not well-controlled (Score 2: 2-6 daytime asthma symptoms/week, ≥2 nighttime asthma symptoms/month, or 2-6 rescue medication use/week), and poorly controlled (Score 3: 7 daytime asthma symptoms/week, ≥2 nighttime asthma symptoms/week, or 7 rescue medication use/week). If the patient has a “Score 3” for any category (daytime symptoms, nighttime symptoms, or rescue medication), then they are considered to have “poorly controlled” asthma. If a “Score 2” is the highest score among 3 categories, they are considered to have “not well-controlled” asthma). 27

Other Covariates

As part of the structured study interview conducted by phone, we collected information on second-hand smoke exposure, type and usage of cooking and heating system, presence of electronic air cleaner, presence of gas fireplace or logs, and mother’s educational level. In addition, we assessed the socioeconomic status (SES) of the study subjects using the HOUSES index.28-33 Participants’ addresses were geocoded to link real property data to each housing unit (eg, living unit for apartment complex), and each property item corresponding to the individual’s address was standardized into a z-score within a county and converted to a quartile such that a higher HOUSES score indicated higher SES. Rural-urban classification of the residence was defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. 34 Average annual daily traffic (AADT) volume data was obtained from Minnesota Geospatial Commons. 35 The GIS package ArcMap (ESRI, Redlands, CA) was used to geocode the residential addresses.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics include counts (percentage) for categorical variables and medians (25th-75th percentile) for continuous variables (Table 1). Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated to measure the degree of correlation between indoor and outdoor NO2 measurements in each season (winter and summer). Univariate analyses were conducted using Kruskal Wallis tests to examine associations between each categorical baseline characteristic (eg, HOUSES) and level of NO2 (indoor and outdoor measurements separately). Univariate association between indoor/outdoor NO2 and asthma outcomes (binary variables; none vs any symptoms or use of rescue medication) were tested using logistic regression models stratified by season and the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals were presented. To test overall association between NO2 and asthma outcomes while considering dependency in data collected in 2 seasons for a given subject, a generalized estimating equation for logistic regression model was used (referred to as “Combined”). As exploratory analyses, we stratified by sex for assessing the association between NO2 levels and asthma outcomes, and also repeated analyses using dichotomized NO2 level (<6 ppb or ≥6 ppb) as an earlier study demonstrated significant associations between increased levels of indoor NO2 and asthma symptoms and severity beginning at levels above 6 ppb. 10 All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software package (version 9.4M6; SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) and a P-value less than .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Table 1.

Basic Characteristics of Study Subjects.

| Variables | Study subjects (N = 62) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |

| Age, years, median (25th – 75th percentile) | 11 (8-14) |

| Female, n (%) | 29 (47%) |

| Non-Hispanic White, n (%) | 54 (87%) |

| Living in rural area, n (%) | 9 (15%) |

| Parent’s educational level a , n (%) | |

| Only high school graduate | 0 (0%) |

| College graduate | 29 (48%) |

| Greater than college graduate | 32 (52%) |

| HOUSES b , n (%) | |

| Q1 (lowest SES) | 5 (9%) |

| Q2 | 7 (13%) |

| Q3 | 16 (30%) |

| Q4 (highest SES) | 26 (48%) |

| Any type of allergies, n (%) | 43 (69%) |

| Any asthma symptoms in the past 12 months (baseline), n (%) | 58 (94%) |

| Indoor environment, n (%) | |

| Second-hand smoking exposure | 0 (0%) |

| Forced air for heating system | 59 (95%) |

| Presence of gas stove for cooking | 18 (29%) |

| Presence of electronic air cleaner | 15 (24%) |

| Presence of gas fireplace or logs | 30 (48%) |

| Asthma outcomes during each collection period, n (%) c | |

| Winter | |

| Daytime symptoms | 42 (68%) |

| Nighttime symptoms | 12 (19%) |

| Asthma rescue medication | 39 (63%) |

| Asthma control status d | |

| Well-Controlled | 41 (66%) |

| Not-Well-Controlled | 21 (34%) |

| Poorly Controlled | 0 (0%) |

| Summer | |

| Daytime symptoms | 23 (37%) |

| Nighttime symptoms | 8 (13%) |

| Asthma rescue medication | 34 (55%) |

| Asthma control status d | |

| Well-Controlled | 49 (79%) |

| Not-Well-Controlled | 13 (21%) |

| Poorly Controlled | 0 (0%) |

Greatest parental educational attainment by self-report (1 missing); bHOUSES: Individual-level socioeconomic status measure (8 missing); cAt least one episode for daytime asthma symptoms, nighttime asthma symptoms, and rescue medication usage; dPer National Asthma Education and Prevention Program EPR-3 (See the section 2.5 in detail).

Results

Basic Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes baseline characteristics of the study subjects. The median age was 11 (25th – 75th percentile: 8-14) years with 29 (47%) female, 54 (87%) non-Hispanic White, and 43 (69%) self-reporting any type of allergies. Thirty-two (52%) children had parents whose educational level was greater than a college education, and 26 (48%) families came from the highest SES (HOUSES Q4 in the community), with 9 (15%) families living in rural areas. All children were on asthma controller medications with 58 (94%) experiencing asthma symptoms in the 12 months prior to the enrollment date. None of the participants reported second-hand smoke exposure, and 18 (29%) had a gas stove at home. Overall poorer asthma outcomes (eg, more symptoms, asthma rescue medications) were reported in winter than in summer.

Spatial and Seasonal Variations in NO2 Related to Residential Characteristics

A total of 238 passive air samplers were returned with 2 unanalyzable samples excluded from NO2 analysis. Median level of NO2 in winter was 3.4 ppb (25th – 75th percentile: 2.5-5.9) for indoor and 3.9 ppb (2.8-5.0) for outdoor (P < .001), and 2.4 ppb (1.8-4.9) for indoor and 2.0 ppb (1.7-2.7) for outdoor in summer (P < .001), respectively. Table 2 summarizes seasonal variations in NO2 related to covariates measured with overall higher correlation between indoor and outdoor NO2 in summer than in winter, albeit statistically not significant (Spearman Correlation coefficient: .14 in summer vs −.03 in winter). Median level of NO2 in winter was 3.4 ppb (25th – 75th percentile: 2.5-5.9) for indoor and 3.9 ppb (2.8-5.0) for outdoor (P < .001), and in summer its was 2.4 ppb (1.8-4.9) for indoor and 2.0 ppb (1.7-2.7) for outdoor (P < .001).

Table 2.

Association of Level of Indoor and Outdoor NO2 With Covariates by Season (unit: ppb).

| Spearman Correlation coefficient a | Winter | Summer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of indoor NO2 | Level of outdoor NO2 | Level of indoor NO2 | Level of outdoor NO2 | |||||

| −0.03 (P-value: .84) | 0.14 (P-value: .32) | |||||||

| Median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) | P-value | Median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) | P-value | Median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) | P-value | Median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) | P-value | |

| Overall | 3.4 (2.5, 5.9) | NA | 3.9 (2.8, 5.0) | <.001 b | 2.4 (1.8,4.9) | NA | 2.0 (1.7,2.7) | <.001 b |

| Living area | ||||||||

| Rural | 6.7 (4.2,8.5) | .022 | 2.7 (2.3, 3.7) | .014 | 5.7 (3.0, 6.3) | .030 | 1.8 (1.6,2.1) | .084 |

| Urban | 3.2 (2.4,5.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 5.2) | 2.3 (1.7, 4.0) | 2.0 (1.7,2.9) | ||||

| HOUSES | ||||||||

| Q1 | 3.1 (2.7, 4.3) | .54 | 5.2 (2.9, 5.6) | .027 | 3.3 (2.2, 5.1) | .074 | 3.0 (2.4,3.7) | .10 |

| Q2 | 4.0 (3.0, 7.4) | 4.4 (3.7, 6.6) | 4.7 (2.4, 6.4) | 2.0 (1.7,3.5) | ||||

| Q3 | 3.8 (2.1, 7.3) | 4.3 (3.4, 5.4) | 2.7 (2.0, 6.1) | 2.1 (1.7,2.8) | ||||

| Q4 | 3.0 (2.4, 4.5) | 3.2 (2.4, 4.6) | 1.9 (1.5, 2.8) | 1.8 (1.6,2.1) | ||||

| Gas stove | ||||||||

| No | 2.9 (2.2, 4.0) | <.001 | NA | 2.0 (1.6, 2.5) | <.001 | NA | ||

| Yes | 7.2 (5.0, 8.2) | 5.7 (4.3, 6.8) | ||||||

| Electronic air cleaner | ||||||||

| No | 3.1 (2.4, 5.0) | .016 | 2.4 (1.7, 4.0) | .091 | ||||

| Yes | 5.0 (4.0, 7.7) | 4.5 (2.0, 6.0) | ||||||

| Gas fireplace or log | ||||||||

| No | 4.3 (3.0, 7.9) | .13 | NA | |||||

| Yes | 3.0 (2.5, 4.5) | |||||||

NO2 measured in ppb; Median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) of NO2 level is reported for each subgroup and subgroups are compared with Kruskal-Wallis test; Indoor features were compared only for Indoor NO2 levels.

Spearman correlation coefficient was used to assess correlation between indoor and outdoor NO2 levels in a given season.

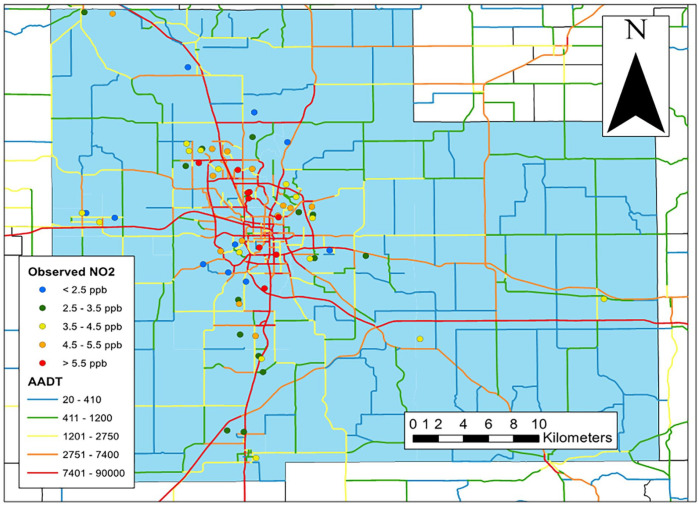

P-value comparing between levels of indoor and outdoor NO2 in each season.

Lower SES as defined by HOUSES index was significantly associated with higher median outdoor NO2 in winter (5.2vs 4.4vs 4.3vs 3.2 for Q1 (lowest SES), Q2, Q3, and Q4, respectively; P = .027); this association was not found for indoor NO2 (P = .54). Levels of outdoor NO2 in winter (median outdoor NO2 (25th – 75th percentile)) in urban areas were significantly higher than in rural areas (4.0 (3.0-5.2) for urban vs 2.7 (2.3-3.7) for rural; P = .014) (Table 2 and Figure 2). This difference between urban and rural areas was not observed in the summer (2.0vs 1.8; P = .084). In winter, the median indoor NO2 level in the homes with gas stoves was higher than those without (7.2 (5.0-8.2) vs 2.9 (2.2-4.0); P < .001). The median level of indoor NO2 was higher in rural compared to urban homes for both seasons (6.7 (4.2-8.5) (rural) vs 3.2 (2.4-5.0) (urban) in winter (P = .022) and 5.7 (3.0-6.3) versus 2.3 (1.7-4.0) in summer (P = .030)). Presence of a gas fireplace in winter was not associated with increased indoor NO2 (P = .13).

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of residences classified by levels of observed outdoor NO2 in winter, and average annual daily traffic (AADT) on numbered roadways, Olmsted County, MN.

Associations of Asthma Outcomes With NO2 Level

In the univariate analysis, no association was found between NO2 levels (indoor or outdoor) and asthma control status, which was confirmed by repeated measures analysis in this cohort (Table 3). In our exploratory analysis where we further assessed if sex might modify this association, the association of daytime asthma symptoms with higher indoor NO2 levels during the summer was found among females (n = 29) but not males while poor asthma control status in winter was associated with indoor NO2 levels among males but not females (data not shown). Further exploratory analysis was conducted to evaluate the relationship between dichotomized NO2 level and asthma control status; the lack of association remained using dichotomized NO2 level (<6 ppb or ≥6 ppb) (data not shown).

Table 3.

Univariate Odds Ratios for Each Asthma Outcome by Level of NO2 Stratified by Season.

| Season | Predictor | Odds Ratio a (95% Confidence Interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daytime symptoms | Nighttime symptoms | Asthma rescue medication | Asthma control status (Not-Well-Controlled) b | ||

| Winter | Indoor NO2 | 0.98 (0.84,1.14) | 1.06 (0.90,1.25) | 1.03 (0.88,1.20) | 1.03 (0.89, 1.20) |

| Outdoor NO2 | 0.94 (0.66, 1.34) | 0.80 (0.51, 1.26) | 0.92 (0.64, 1.29) | 0.96 (0.67, 1.38) | |

| Summer | Indoor NO2 | 1.27 (0.99, 1.63) | 1.09 (0.87, 1.36) | 1.09 (0.88, 1.36) | 1.14 (0.93, 1.40) |

| Outdoor NO2 | 1.86 (0.96,3.61) | 1.48 (0.71,3.09) | 1.42 (0.74, 2.71) | 1.77 (0.91, 3.43) | |

| Combined c | Indoor NO2 | 1.07 (0.93,1.24) | 1.07 (0.92,1.25) | 1.05 (0.90,1.23) | 1.07 (0.94,1.21) |

| Outdoor NO2 | 1.12 (0.78,1.60) | 0.93 (0.61,1.41) | 1.01 (0.70,1.45) | 1.10 (0.79,1.54) | |

Logistic regression models using each asthma outcome as the dependent variable with reported odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals corresponding to a 1 -unit (ppb) change in NO2 level.

Per National Asthma Education and Prevention Program EPR-3 (see Method section in detail) with Well-Controlled as a reference.

Mixed effect logistic regression model treating subject as random effect.

Discussion

It is feasible to measure residential levels of outdoor and indoor NO2 to describe residential characteristics related to spatial and seasonal variations in NO2. Both indoor and outdoor levels of NO2 were low in this mixed U.S. rural-urban community. Observed spatial and seasonal variation of this air pollutant was largely attributable to urban-rural status, individual level SES, and presence of gas stove in participant’s home. Specifically, children from lower socioeconomic status living in urban areas were exposed to higher outdoor NO2, especially in winter. Indoor NO2 was higher in rural areas as well as in families with a gas stove regardless of seasons.

For seasonal and geographic variability, the median indoor level of NO2 in rural areas was higher than in urban areas in both seasons (6.7vs 3.2 for winter; P = .022, 5.7 vs 2.3 for summer; P = .030), but not outdoor. While the proportion of families who had gas stoves in their homes in this study population was lower than the U.S. average (29%vs 38%), we did find higher indoor NO2 levels in homes with gas stoves in both seasons which is consistent with the literature10,36 and may explain higher indoor levels of NO2 in rural areas of our study setting compared to urban areas as presence of a gas stove was statistically higher in families living in rural areas (vs urban areas; 78%vs 21%; P = .001). Albeit statistically not significant, the correlation between indoor and outdoor NO2 concentrations was higher in the summer (.14) compared to winter (−.03), which may be influenced by the frequency and duration of opening windows during summer. Other unmeasured factors such as emissions from indoor sources and NO2 reactivity might also contribute to differential exposure pattern. 15

Apart from seasonal and geographic factors, residential characteristics played an important role in determining NO2 concentrations. While literature shows inconsistent results on the association between outdoor NO2 and SES measures,37,38 a negative relationship between outdoor NO2 and individual-level SES as defined by the HOUSES index was observed in both seasons in our study. This relationship was not found for indoor NO2. Literature suggests that elevated outdoor NO2 is strongly associated with urban areas with high traffic volume39,40 which is consistent with our data, especially in winter. This observation might be pertinent to asthma epidemiology and contribute to disparities in asthma incidence. For example, we previously reported that children living in homes located in high-traffic areas have a higher risk of developing asthma (hazard ratios, 1.3-1.6 depending on the matching methods) compared with the matched counterparts in this community. 41 Outdoor NO2 levels are known to be higher in winter than in summer, partly attributable to increased fossil fuel use for domestic heating and transportation,42,43 and lower mixing layer height in winter. 44 This may contribute to a disproportionate burden of asthma among people from lower SES, especially those living in urban areas and areas with high traffic volumes. Given seasonality of asthma exacerbation, future studies with a larger sample size need to assess the effect of traffic volume and NO2 concentration and other air quality measures in the context of seasonal and geographic variability on asthma outcomes.

Our exploratory analysis suggested that sex might be an effect modifier for the association between NO2 and asthma outcomes; higher indoor NO2 was associated with increased daytime asthma symptoms among females in summer and associated with overall poorer asthma control status among males in winter, suggesting potentially greater impact of indoor NO2 than outdoor NO2 (data not shown). 45 Sex differences in behaviors by season as well as sex differences in lung growth rates and hormone exposure might contribute to this finding. Interestingly, a review paper highlighting the effects of sex on air pollution epidemiology included studies that showed stronger effects among boys in early life and among girls in later childhood. 46

Our study findings have a few implications on asthma care and research. Our study results may help clinicians to contextualize the potential impact of air quality on health outcomes in mixed rural-urban communities. For example, in rural areas, they may target families with gas stoves to mitigate the potential impact of indoor NO2, while in urban areas, they may want to focus on families with lower SES to mitigate the impact of outdoor NO2, especially for patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. To reduce exposure to air pollutants for families who use a gas stove and live in rural areas with low outdoor NO2 levels (eg, 1.8-2.7 ppb), more frequent indoor ventilation or switching from using gas stoves to electric stoves for cooking may be recommended.8,47 Acknowledging the impact of these factors would be helpful when providing guidance to patients with respiratory or cardiovascular diseases on actional interventions that would be most effective at decreasing the potential burden of environmental factors. As our study showed a relatively low level of outdoor NO2 and limited association with asthma control status in children, further research may be warranted for examination of other outdoor triggers (eg, fine particle exposures such as Particulate Matter 2.5 (PM2.5)).

A major strength of this study includes the 62 broad collection sites across Olmsted County (Figure 2). This is an important step toward developing spatial models of outdoor NO2 concentrations which can be applied to diverse health outcomes such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, cardiovascular diseases, mental disorders, mortality, etc., for large-sample sized population-based studies.48-50 Another strength is using the HOUSES index, an objective individual-level socioeconomic status (SES) measure with precision, which demonstrated an inverse association with outdoor NO2 levels (Table 2). This study also has some limitations. First, our cohort was subject to selection bias by including a disproportionately higher number of families from a higher SES background (all parents or guardians with a college degree or above). As a feasibility study, we made the decision to enroll all those who chose to accept the study invitation, but future investigators may find it prudent to use the HOUSES index to guide enrollment in order to procure a well-balanced sample set regarding SES by monitoring the distribution of SES among enrolled subjects. Another limitation is the short collection period (4 weeks total). However, by collecting NO2 during the heating and non-heating seasons, we were able to account for seasonality by reporting both repeated measures analysis and stratified analysis by season. A few additional factors might have impacted our study results. Families who had gas stoves in our study also tended to have an air cleaner (33%) compared to those without gas stoves (21%), albeit not statistically significant. The inconsistent placement or location of the Palmes tube/monitor during the measurement period (ie, within the living room) with respect to where the air cleaner is located (data not collected) may affect this result. Also, only 12 families (about 20%) reported they had used a gas fireplace more than half of the time during the study period. Lastly, given the small sample size for assessing the association between the level of NO2 and asthma outcomes, we could not control for other confounding effects, such as SES, other airborne contaminants (eg, PM2.5), and living in close proximity to areas with high grass cover, which have been shown to affect asthma incidence or outcomes.5,6,51

Conclusion

In conclusion, NO2 levels were low in this mixed rural-urban community with geographical and seasonal variations. A rural setting and the presence of a gas stove were associated with indoor NO2 concentrations while an urban setting and lower SES (outdoor) with outdoor NO2 concentrations. These findings may help clinicians contextualize the potential impact of air quality on health outcomes in mixed rural-urban communities and guide researchers to define a lower threshold of NO2 concentration with health effect.

Footnotes

Credit Author Statement: All authors meet the criteria for authorship based on the following four requirements: (1) substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; (2) drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; (3) final approval of the version to be published; and (4) agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Specifically, CW had full access to all the data in the study, takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, and had authority over manuscript preparation and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Study concept and design: CW, JG, ER, PW, BL, and YJ. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: CW, JG, JB, KK, ER, KS, JP (Plano), LM, JP(Porcher), SC, AD, KP, BS, BL, and YJ. Drafting of the manuscript: CW. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This was supported by Marcia T. Kreyling Career Development Award, Mayo Foundation. This study was made possible using the resources of the HOUSES program of the Precision Population Science Lab of the Mayo Clinic. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Mayo Foundation or the HOUSES program.

ORCID iDs: Chung-Il Wi  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8938-2997

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8938-2997

Sergio E. Chiarella  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0445-4929

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0445-4929

Andrew T. DeWan  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7679-8704

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7679-8704

References

- 1.Alotaibi R, Bechle M, Marshall JD, et al. Traffic related air pollution and the burden of childhood asthma in the contiguous United States in 2000 and 2010. Environ Int. 2019;127:858-867. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.03.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Ni H, Bai L, et al. The short-term association between air pollution and childhood asthma hospital admissions in urban areas of Hefei City in China: A time-series study. Environ Res. 2019;169:510-516. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.11.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia E, Berhane KT, Islam T, et al. Association of Changes in air quality with incident asthma in children in California, 1993-2014. JAMA. 2019;321:1906-1915. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berhane K, Chang CC, McConnell R, et al. Association of Changes in air quality with Bronchitic symptoms in children in California, 1993-2012. JAMA. 2016;315:1491-1501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orellano P, Quaranta N, Reynoso J, Balbi B, Vasquez J.Effect of outdoor air pollution on asthma exacerbations in children and adults: systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng XY, Orellano P, Lin HL, Jiang M, Guan WJ.Short-term exposure to ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and sulphur dioxide and emergency department visits and hospital admissions due to asthma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2021;150:106435. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Achakulwisut P, Brauer M, Hystad P, Anenberg SC.Global, national, and urban burdens of paediatric asthma incidence attributable to ambient NO2 pollution: estimates from global datasets. Lancet Planet Health. 2019;3:e166-e178. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30046-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu Y, Ji JS, Zhao B.Restrictions on indoor and outdoor NO2 emissions to reduce disease burden for pediatric asthma in China: A modeling study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022;24:100463. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guarnieri M, Balmes JR.Outdoor air pollution and asthma. Lancet. 2014;383:1581-1592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60617-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belanger K, Holford TR, Gent JF, Hill ME, Kezik JM, Leaderer BP.Household levels of nitrogen dioxide and pediatric asthma severity. Epidemiology. 2013;24:320-330. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318280e2ac [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Lung Association. State of the Air 2014. Accessed February. http://www.stateoftheair.org/2014/assets/ALA-SOTA-2014-Full.pdf

- 12.Yawn BP, Wollan P, Kurland M, Scanlon P.A longitudinal study of the prevalence of asthma in a community population of school-age children. J Pediatr. 2002;140:576-581. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.123764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akinbami LJ, Simon AE, Rossen LM.Changing trends in asthma prevalence among children. Pediatrics. 2016;137:1-7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francisco PW, Gordon JR, Rose B.Measured concentrations of combustion gases from the use of unvented gas fireplaces. Indoor Air. 2010;20:370-379. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2010.00659.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meier R, Eeftens M, Phuleria HC, et al. Differences in indoor versus outdoor concentrations of ultrafine particles, PM2.5, PMabsorbance and NO2 in Swiss homes. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2015;25:499-505. doi: 10.1038/jes.2015.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shuai J, Yang W, Ahn H, Kim S, Lee S, Yoon SU.Contribution of indoor and outdoor nitrogen dioxide to indoor air quality of wayside shops. J UOEH. 2013;35:137-145. doi: 10.7888/juoeh.35.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Center DDM. What is DMC?. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://dmc.mn/what-is-dmc/

- 18.2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria. 2021. Assessed May 8 2023. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural/2010-urban-rural.html

- 19.Yunginger JW, Reed CE, O’Connell EJ, Melton LJ, 3rd, O’Fallon WM, Silverstein MD.A community-based study of the epidemiology of asthma. Incidence rates, 1964-1983. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:888-894. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.4.888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Barbaresi WJ, Schaid DJ, Jacobsen SJ.Potential influence of migration bias in birth cohort studies. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:1053-1061. doi: 10.4065/73.11.1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HY, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT.The many paths to asthma: phenotype shaped by innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:577-584. doi: 10.1038/ni.1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong W, Finnie DM, Shah ND, et al. Effect of multiple chronic diseases on health care expenditures in childhood. J Prim Care Community Health. 2015;6:2-9. doi: 10.1177/2150131914540916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmes ED, Gunnison AF, DiMattio J, Tomczyk C.Personal sampler for nitrogen dioxide. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1976;37: 570-577. doi: 10.1080/0002889768507522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skene KJ, Gent JF, McKay LA, Belanger K, Leaderer BP, Holford TR.Modeling effects of traffic and landscape characteristics on ambient nitrogen dioxide levels in Connecticut. Atmos Environ. 2010;44:5156-5164. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.08.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wi CI, Sohn S, Rolfes MC, et al. Application of a natural language processing algorithm to asthma ascertainment. An Automated Chart Review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:430-437. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201610-2006OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma–Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:S94-S138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:S94-138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juhn YJ, Beebe TJ, Finnie DM, et al. Development and initial testing of a new socioeconomic status measure based on housing data. J Urban Health. 2011;88:933-944. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9572-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson MD, Urm SH, Jung JA, et al. Housing data-based socioeconomic index and risk of invasive pneumococcal disease: an exploratory study. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:880-887. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812001252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bang D, Manemann S, Gerber Y, et al. A novel socioeconomic measure using individual housing data in cardiovascular outcome research. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2014;11:11597-11615. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111111597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juhn Y, Krusemark E, Rand-Weaver J, et al. A novel measure of socioeconomic status using individual housing data in health disparities research for asthma in adults. Allergy. 2014; 69:327-327. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris MN, Lundien MC, Finnie DM, et al. Application of a novel socioeconomic measure using individual housing data in asthma research: an exploratory study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14018. doi: 10.1038/Npjpcrm.2014.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghawi H, Crowson CS, Rand-Weaver J, Krusemark E, Gabriel SE, Juhn YJ.A novel measure of socioeconomic status using individual housing data to assess the association of SES with rheumatoid arthritis and its mortality: a population-based case-control study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006469. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Census Bureau. Geography Program: Urban and Rural. 2018. Accessed October 1. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural.html

- 35.Minnesota Geospatial Commons. Annual Average Daily Traffic Segments in Minnesota. Accessed March 23, 2021. https://gisdata.mn.gov/dataset/trans-aadt-traffic-segments

- 36.US Department of Housing and Urban Development and US Census Bureau. American Housing Survey for the United States. 2009. Accessed April 7, 2021. https://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/h150-09.pdf

- 37.Fernández-Somoano A, Tardon A.Socioeconomic status and exposure to outdoor NO2 and benzene in the Asturias INMA birth cohort, Spain. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68:29-36. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-202722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinault L, Crouse D, Jerrett M, Brauer M, Tjepkema M.Spatial associations between socioeconomic groups and NO2 air pollution exposure within three large Canadian cities. Environ Res. 2016;147:373-382. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Novotny EV, Bechle MJ, Millet DB, Marshall JD.National satellite-based land-use regression: NO2 in the United States. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:4407-4414. doi: 10.1021/es103578x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang L, Guan Y, Leaderer BP, Holford TR.Estimating daily nitrogen dioxide level: exploring traffic effects. Ann Appl Stat. 2013;7:1763-1777. doi: 10.1214/13-Aoas642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Juhn YJ, Qin R, Urm S, Katusic S, Vargas-Chanes D.The influence of neighborhood environment on the incidence of childhood asthma: a propensity score approach. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:838-843.e2 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bigi A, Harrison RM.Analysis of the air pollution climate at a central urban background site. Atmos Environ. 2010;44:2004-2012. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith LA, Mukerjee S, Chung KC, Afghani J.Spatial analysis and land use regression of VOCs and NO2 in Dallas, Texas during two seasons. J Environ Monit. 2011;13:999-1007. doi: 10.1039/c0em00724b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y, Tang G, Wang M, et al. Impact of residual layer transport on air pollution in Beijing, China. Environ Pollut. 2021;271:116325. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu Y, Zhao B.Indoor sources strongly contribute to exposure of Chinese urban residents to PM2.5 and NO2. J Hazard Mater. 2022;426:127829. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clougherty JE.A growing role for gender analysis in air pollution epidemiology. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:167-176. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Francisco PW, Jacobs DE, Targos L, et al. Ventilation, indoor air quality, and health in homes undergoing weatherization. Indoor Air. 2017;27:463-477. doi: 10.1111/ina.12325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Z, Wang J, Lu W.Exposure to nitrogen dioxide and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:15133-15145. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-1629-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pranata R, Vania R, Tondas AE, Setianto B, Santoso A.A time-to-event analysis on air pollutants with the risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 84 cohort studies. J Evid Based Med. 2020; 13:102-115. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gładka A, Rymaszewska J, Zatoński T.Impact of air pollution on depression and suicide. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2018;31:711-721. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aerts R, Dujardin S, Nemery B, et al. Residential green space and medication sales for childhood asthma: A longitudinal ecological study in Belgium. Environ Res. 2020;189:109914. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]