Abstract

Objective:

To provide recommendations for JIA with focus on non-pharmacologic therapies, medication monitoring, immunizations and imaging, irrespective of JIA phenotype.

Methods:

We developed clinically relevant population, intervention, comparator and outcomes (PICO) questions. After conducting a systematic literature review, the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to rate the quality of evidence (high, moderate, low, very low). A voting panel including clinicians and patients/caregivers achieved consensus on the direction (for or against) and strength (strong or conditional) of recommendations.

Results:

This guideline recommends the use of PT and OT interventions; a healthy, well-balanced, age-appropriate diet; specific laboratory monitoring for medications; widespread use of immunizations; and shared decision-making with patients/caregivers. Disease management is addressed for all patients with JIA with respect to non-pharmacologic therapies, medication monitoring, immunizations and imaging. Evidence for all recommendations was graded as low or very low in quality. For that reason, more than half of the recommendations are conditional.

Discussion:

This clinical practice guideline complements the 2019 ACR JIA and uveitis guidelines, on polyarthritis, sacroiliitis, enthesitis and uveitis, and a concurrent 2021 guideline on oligoarthritis, temporomandibular arthritis and systemic JIA. It serves as a tool to support clinicians, patients and caregivers in decision-making. Although evidence is generally low quality and many recommendations are conditional, the inclusion of caregivers and patients in the decision-making process strengthens the relevance and applicability of the guideline. It is important to remember that these are recommendations. Clinical decision-making, as always, remains in the hands of the treating clinician and patient/caregiver.

Keywords: juvenile idiopathic arthritis, clinical practice guidelines, disease modifying anti rheumatic drugs, biologics, monitoring, immunization, non-pharmacologic, imaging

INTRODUCTION:

Reflecting the changing medical landscape, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) regularly updates clinical practice guidelines. The process for updating the 2011 and 2013 Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) guidelines began in 20171, 2 Important clinical topics for consideration were first identified at a meeting to define the scope of the guidelines. Recent advances in the treatment of JIA and better understanding of pathogenesis dictated separating this clinical practice guideline into several parts due to the breadth of topics. The first part, addressing polyarthritis, sacroiliitis, enthesitis and uveitis, was published in two manuscripts in 20193, 4. The second part, presented here in 2 papers, covers a) oligoarthritis, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) arthritis, systemic arthritis (sJIA) and b) non-pharmacologic treatments, immunizations and patient monitoring5. The methods and literature review described below reflects the unified process used for the second part of these guidelines, including both manuscripts.

We developed clinically relevant population, intervention, comparator and outcomes (PICO) questions. Using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, recommendations were developed based on the best available evidence for commonly encountered clinical scenarios. Prior to final voting, input was sought from relevant stakeholders including a panel of young adults with JIA and caregivers of children with JIA to consider their values and perspectives in making recommendations. Both the patient/caregiver and guideline voting panels stressed the need for individualized treatment while being mindful of available evidence, and the need to include recommendations on non-pharmacologic therapies.

METHODS

This guideline follows the ACR guideline development process and ACR policy guiding management of conflicts of interest and disclosures (https://www.rheumatology.org/Practice-Quality/Clinical-Support/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines), which includes GRADE methodology 6, 7and adheres to AGREE criteria8. Supplementary Appendix 1 includes a detailed description of the methods. Briefly, the core leadership team (KO, DH, DL, SS) drafted clinical PICO questions. PICO questions were revised and finalized based on feedback from the entire guideline development group and the public. The literature review team performed systematic literature reviews for each PICO, graded the quality of evidence (high, moderate, low, very low) and produced the evidence report (see Supplementary Appendix 2). Note that GRADE methodology does not distinguish between lack of evidence (i.e., none) and very low-quality evidence. The core team defined multiple critical study outcome(s) for PICOs relevant to each JIA phenotype (see Supplementary Appendix 3).

A virtual panel of 15 members, including young adults with JIA and caregivers of children with JIA, moderated by the principal investigator (KO), reviewed the evidence report and provided input to the voting panel. Two members of this panel (JH, KM) were also members of the voting panel to ensure that the patient voice was part of the entire process. The voting panel reviewed the evidence report and patient/caregiver perspectives and then discussed and voted on recommendation statements. Consensus required ≥70% agreement on both direction (for or against) and strength (strong or conditional) of each recommendation as per ACR practice. A recommendation could be either in favor of or against the proposed intervention and either strong or conditional. According to GRADE, a recommendation is categorized as strong if the panel is very confident that the benefits of an intervention clearly outweigh the harms (or vice versa); a conditional recommendation denotes uncertainty regarding the balance of benefits and harms, such as when the evidence quality is low or very low, or when the decision is sensitive to individual patient preferences, or when costs are expected to impact the decision. Thus, conditional recommendations refer to decisions in which incorporation of patient preferences is a particularly essential element of decision making.

Rosters of the core leadership, literature review team and both panels are included in Supplementary Appendix 4.

Guiding Principles

Consistent with the ACR’s 2019 JIA guidelines, these recommendations are for persons diagnosed with JIA.

Extra-articular coexisting conditions that would influence disease management and monitoring, such as uveitis, psoriasis or inflammatory bowel disease, are not addressed within these guidelines.

Recommendations for immunizations were evaluated to be consistent with guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) while taking into consideration the unique needs of persons with JIA.

Recommendations are intended to be used by all clinicians caring for persons with JIA.

Shared decision-making with families and patients is critical.

RESULTS/RECOMMENDATIONS

The initial literature review (through August 7, 2019) identified 4308 manuscripts in searches for all PICO questions pertaining to oligoarthritis, TMJ arthritis, sJIA and the topics addressed in this manuscript, including non-pharmacologic therapies, nutrition, supplements, medication monitoring, immunizations, and imaging. A July 9, 2020 search update identified 367 more references, for a total of 4675 papers after duplicates and non-English publications were removed. After excluding 2291 titles and abstracts, 2384 full-text articles were screened. Of these, 1939 were excluded (see Supplemental Appendix 5, leaving 445 articles to be considered for the evidence report. In the end, 406 papers were matched to PICO questions and included in the final evidence report. Quality of evidence was uniformly low or very low; 17 PICO questions lacked any associated evidence (Tables 1 and 3–6). The following recommendations are based on 62 PICO questions. Several PICO questions were split into 24 sub-PICO questions to improve specificity. Nine questions initially posed were discarded by the voting panel because of redundancy or lack of relevance.

Table 1:

Strength of recommendations/quality of supporting evidence

| Strength of Recommendation | Quality of Supporting Evidence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic | Recs | Cond | Str | VL | L | Mod | Hi |

| Non-pharmacologic therapies | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Medication Monitoring | 20 | 17 | 3 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infection Surveillance/Immunizations | 7 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Imaging | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 33 | 23 | 10 | 28 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Key:

Recs-Recommendations

Cond-Conditional

Str-Strong

VL-Very Low

L-Low

Mod-Moderate

Hi-High

Note: Lack of evidence for Tofacitinib given FDA approval date.

Table 3:

Non-Pharmacologic Therapies

| Recommendations | Certainty of Evidence | Based on the evidence report(s) of the following PICO(s)7 | Evidence table(s) on page(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A discussion of healthy, age-appropriate diet

is strongly

recommended. ----------------------------------------- Use of a specific diet to treat JIA is strongly recommended against. ---------------------------------------- Use of supplemental or herbal interventions specifically to treat JIA is conditionally recommended against. |

Very Low | PICO 7: In children with oligoarticular JIA,

should dietary or herbal interventions be recommended, in addition to

whatever other therapeutic options are given, versus not recommending

them? --------------------------- PICO 17. In children with JIA with active TMJ arthritis, should dietary or herbal interventions be recommended, in addition to whatever other therapeutic options are given, versus not recommending them? |

48-49 60 |

| Physical and occupational therapy (PT/OT) are conditionally recommended regardless of concomitant pharmacologic therapy. | Very low | PICO 8. In children with oligoarticular JIA,

regardless of disease activity and poor prognostic features, should

PT/OT versus no PT/OT (regardless of concomitant medical therapy) be

recommended? --------------------------- PICO 18. In children with JIA with active TMJ arthritis, regardless of disease activity and poor prognostic features, should PT versus no PT (regardless of concomitant medical therapy) be recommended? |

49-51 60 |

Table 6:

Imaging

| Recommendations | Certainty of Evidence | Based on the evidence report(s) of the following PICO(s)7 | Evidence table(s) on page(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of radiographs as a screening test prior to advanced imaging, for the purpose of identifying active synovitis or enthesitis, is strongly recommended against. | Very low | PICO 55: In children with JIA, is any specific imaging technique recommended to best detect inflammation and damage, make a diagnosis, predict structural damage, flare or treatment response? | 199-268 |

| Imaging guidance is conditionally recommended for use with IAGC injections of joints that are difficult to access, or to specifically localize the distribution of inflammation. | Very low | PICO 56: In children with JIA who require IA corticosteroid (IAC) injections, should injections be done with imaging guidance? | 269-279 |

Final recommendations are described below and in Tables 3–6, which include reference(s) to which PICO question(s) in the evidence report correspond to the recommendation statement.

NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPIES

Patient/caregiver panelists specifically asked that recommendations for non-pharmacologic treatment be included in this guideline, although they understood that evidence is generally lacking to support specific statements.

Physical and occupational therapy (PT/OT)

PT and OT are conditionally recommended regardless of concomitant pharmacologic therapy.

Reasons for using PT or OT include maintaining or improving joint range of motion (particularly for contractures), improving strength, reversing functional deficits, improving endurance, preventing injury, and promoting improved participation in Activities of Daily Living (ADL), family routines and occupations.

NUTRITION

A discussion of healthy, age-appropriate diet is strongly recommended.

Use of a specific diet to treat JIA is strongly recommended against.

Ample evidence supports the value of a healthy, balanced, nutrient dense diet for all children with consideration for specific age-appropriate nutritional requirements (e.g., fat, calcium)11, 12. Therefore, it is worth talking about the importance of an age-appropriate diet.13 However, no evidence to date supports the use of a specific diet alone to treat JIA. 14, 15.

Furthermore, some overly restrictive diets (e.g., gluten-free, dairy-free) may result in nutritional deficits and risk other harms (e.g., delay in treatment, cost, inconvenience).

SUPPLEMENTS

Use of supplemental or herbal interventions specifically to treat JIA is conditionally recommended against.

Voting panelists had concerns about the safety of unregulated supplements and herbal formulations and stressed the importance of discussion and transparency regarding their use. Some evidence of efficacy supports the use of supplements to treat joint inflammation in adults (e.g., fish oils), but very limited efficacy and safety data exists for JIA16.

MONITORING

a). MEDICATIONS:

Laboratory test monitoring to detect medication toxicity should balance the risk of adverse events and patients’/caregivers’ desire for safety, with the pain, inconvenience and cost of phlebotomy and laboratory tests. The following recommendations pertain to specific medications or medication classes (Table 4 and 7). If a child is taking more than one medication, the more frequent schedule for laboratory testing is recommended. In formulating the recommendations below, the voting panel considered the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prescription drug labels (package inserts) in addition to the studies included in the systematic review.

Table 4:

Medication monitoring

| Recommendations | Certainty of Evidence | Based on the evidence report(s) of the following PICO(s)7 | Evidence table(s) on page(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSAIDS: CBC, LFTs and renal function tests are conditionally recommended to be monitored every 6-12 months. | Very low | PICO 30: Is there a recommended laboratory screening schedule (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel and urinalysis) for children receiving chronic daily NSAIDs? | 144-145 |

| Methotrexate: CBC, LFTs and renal function are strongly recommended to be monitored within the first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months thereafter. | Very low | PICO 31: Is there a recommended laboratory screening schedule (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel) for children being treated with methotrexate (po or sq)? | 145-150 |

| Decreasing or holding the methotrexate dose is conditionally recommended if a clinically relevant elevation in LFTs or decreased neutrophil or platelet count is found. | Very low | PICO 32: After methotrexate (po or sq) is initiated, is there a recommended medication change secondary to elevated liver function tests and decreased neutrophil or platelet count? | 150-153 |

| Use of folic/folinic acid is strongly recommended in conjunction with methotrexate. | Very low | PICO 7: In children with oligoarticular JIA, should dietary or herbal interventions be recommended, in addition to whatever other therapeutic options are given, versus not recommending them? | 60 |

| Sulfasalazine: CBC, LFTs and renal function are conditionally recommended to be monitored within the first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months thereafter. | Very low | PICO 33. Is there a recommended laboratory screening schedule (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel) for children with JIA being treated with sulfasalazine? | 153-155 |

| Decreasing or holding the sulfasalazine dose is conditionally recommended if a clinically relevant elevation in LFTs or decreased neutrophil or platelet count is found. | Very low | PICO 34. After sulfasalazine is initiated, is there a recommended medication change in response to elevated liver function tests and decreased neutrophil or platelet count? | 155-157 |

| Leflunomide: CBC and LFTs are conditionally recommended to be monitored within the first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months thereafter. | Very low | PICO 35. Should children with JIA receiving leflunomide have serum creatinine, urinalysis, complete blood count and liver enzymes before and during treatment, per manufacturer’s recommendations? | 157-158 |

| Altering leflunomide administration is conditionally recommended if a clinically relevant elevation in LFTs occurs (temporary hold of leflunomide for ALT> 3X the upper limit of normal [ULN]), as per package insert. | Very low | PICO 36. After leflunomide is initiated, should medication dosage be altered according to the package insert secondary to elevated liver function tests? | 158-159 |

| Baseline and annual retinal screening are conditionally recommended after starting hydroxychloroquine | Very low | PICO 37. Should children with JIA receiving treatment with hydroxychloroquine have annual screening tests with automated visual fields, if age appropriate, plus spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD OCT) versus starting annual screening 5 years after treatment onset? | 159 |

| Hydroxychloroquine: CBC and LFTs are conditionally recommended to be monitored annually. | Very low | PICO 38. Is there a recommended laboratory screening schedule (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel) for children with JIA being treated with hydroxychloroquine? | 159 |

| TNFi: CBC and LFTs are conditionally recommended to be monitored annually. | Very low | PICO 39. Is there a recommended laboratory screening schedule (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel and urinalysis) for children with JIA receiving TNF inhibitor treatment? | 160-161 |

| Abatacept: Doing no routine laboratory monitoring is conditionally recommended. | Very low | PICO 40. Is there a recommended laboratory screening schedule (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel and urinalysis) for children with JIA receiving abatacept treatment? | 161-162 |

| Tocilizumab: CBC and LFTs are

conditionally recommended to be monitored within the

first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months

thereafter. Lipids are conditionally recommended to be monitored every 6 months, as per package insert. |

Very low | PICO 41. Should children with JIA receiving tocilizumab have serum creatinine, urinalysis, complete blood cell count, and liver enzymes before and during treatment, per manufacturer’s recommendations? | 162 |

| Altering tocilizumab administration is conditionally recommended after starting tocilizumab if monitoring reveals elevated LFTs (1-3X ULN decrease dose or interval, 3XULN hold dose, 5XULN discontinue treatment), neutropenia (500-1000/mm3), or thrombocytopenia (50,000-100,000/mm3), as per package insert. | Very low | PICO 42. After tocilizumab is initiated, should medication dosage be altered according to the package insert secondary to elevated liver function tests, neutropenia and/or thrombocytopenia? | 163 |

| Anakinra: CBC and LFTs are conditionally recommended to be monitored within the first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months thereafter. | Very low | PICO 43. Is there a recommended laboratory screening schedule (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel and urinalysis) for children with JIA receiving anakinra treatment? | 163-164 |

| Canakinumab: CBC and LFTs are conditionally recommended to be monitored within the first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months thereafter. | Very low | PICO 44. Is there a recommended laboratory screening schedule (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel and urinalysis) for children with JIA receiving canakinumab treatment? | 164 |

| Tofacitinib: CBC and LFTs are

conditionally recommended to be monitored within the

first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months

thereafter. Lipids are conditionally recommended to be monitored 1-2 months after starting treatment, as per package insert. Altering medication administration as per package insert is strongly recommended after starting tofacitinib; medication should be discontinued if hemoglobin is less than 8 g/dl or decreases more than 2 g/dl, or for severe neutropenia(<500/mm3) or lymphopenia(<500/mm3). |

* | *Given recent approval for JIA and limited experience, recommendations are as per clinical trial, FDA guidance and evidence in adults | * |

Table 7:

Medication Monitoring*

| Methotrexate**# | Sulfasalazine** | Leflunomide# | Tocilizumab | Anakinra | Tofacitinib | Canakinumab | NSAIDs** | Hydroxychloroquine | TNFi | Abatacept | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBC /diff and

LFTs -Baseline -1-2 months after starting -Every 3-4 months thereafter*** |

X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| CBC/diff and

LFTs -Baseline -Every 6-12 months |

X | ||||||||||

| CBC/diff and

LFTs -Baseline -Once yearly |

X | X | |||||||||

| Lipid panel -Baseline -Every 6 months |

X | ||||||||||

| Lipid panel -Baseline -4-8 weeks after starting |

X | ||||||||||

| Eye exam -Baseline -Once yearly |

X | ||||||||||

| None required | X |

If patient is on more than one medication, a more restrictive schedule should be used

Include renal function with lab work

Should be rechecked sooner if dose increased

Pregnancy test should be considered before use, and counseling as to use of effective methods of contraception is recommended

For medications that are known teratogens (e.g., methotrexate, leflunomide), when applicable, pregnancy testing should be considered before usage, and counseling on effective methods of contraception is recommended17. When required by the FDA, a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) should be done18.

Baseline laboratory testing is conditionally recommended prior to treatment onset, for all medications.

Baseline laboratory evaluation is recommended to identify potential contraindications to a specific treatment. This should include complete blood counts with differential (CBC) and liver function tests (LFTs) (e.g., ALT and AST), plus renal function tests (e.g., BUN, creatinine and urinalysis) for methotrexate, sulfasalazine and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and lipid profiles for tocilizumab and tofacitinib. Additional laboratory testing may be done at the discretion of the treating clinician.

NSAIDs (all)

CBC, LFTs and renal function tests are conditionally recommended to be monitored every 6-12 months.

NSAIDs are known to be associated with GI bleed risk, and liver and kidney toxicity in adults with rheumatic diseases. Although these may be rare in children, the panel felt it important to monitor for laboratory abnormalities periodically in children receiving long-term NSAIDs. Because gastrointestinal (GI) distress when taking NSAIDs consistently is common, patients/caregivers strongly suggested inquiring about and treating GI symptoms, which may not always be spontaneously reported19, 20.

Methotrexate

CBC, LFTs and renal function are strongly recommended to be monitored within the first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months thereafter.

Voting panelists debated whether frequent (as per the package instructions, i.e., CBC monthly and renal/liver function every 1-2 months) methotrexate toxicity monitoring should be recommended for children, given low incidence of liver toxicity21, 22 . However, rare potential for serious harm in children and consistency in monitoring schedule during pediatric-to-adult care transition influenced the panel’s decision to provide a strong recommendation for frequent monitoring23.

Decreasing or holding the methotrexate dose is conditionally recommended if a clinically relevant elevation in LFTs or decreased neutrophil or platelet count is found.

The panel did not reach consensus on specific values to define elevated LFT or reduced counts. Clinically relevant laboratory abnormalities may include repetitive, small abnormalities or single large abnormalities. LFTs may be transiently elevated if testing is done within 2 days after the methotrexate dose; hence testing within this window is discouraged.

Use of folic/folinic acid is strongly recommended in conjunction with methotrexate.

Use of folic/folinic acid with methotrexate may mitigate adverse events and improve tolerability24, 25.

Sulfasalazine

CBC, LFTs and renal function are conditionally recommended to be monitored within the first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months thereafter.

Recommended monitoring is less frequent than suggested in the package insert (which suggests CBC, LFT every 2nd week in first three months, monthly during next three months, then every 3 months) because children are much less likely than adults to have abnormal results, given fewer comorbidities and concomitant medications26, 27,28.

Decreasing or holding the sulfasalazine dose is conditionally recommended if a clinically relevant elevation in LFTs or decreased neutrophil or platelet count is found.

While adverse reactions can be serious, including Stevens-Johnson or DRESS syndromes29, the voting panel thought the data was too limited to make this recommendation strong.

Leflunomide

CBC and LFTs are conditionally recommended to be monitored within the first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months thereafter.

Recommended LFT monitoring is less frequent than suggested in the package insert (which recommends CBC, ALT monthly for six months then every 6-8 weeks)30 because most children have fewer comorbidities and polypharmacy usage is rare, allowing for fewer drug interactions31 .

Altering leflunomide administration is conditionally recommended if a clinically relevant elevation in LFTs occurs (temporary hold of leflunomide for ALT> 3X the upper limit of normal [ULN]), as per package insert.

Elimination of leflunomide can be accelerated with the use of cholestyramine or activated charcoal30, when required.

Hydroxychloroquine

CBC and LFTs are conditionally recommended to be monitored annually.

As per package insert, periodic laboratory monitoring should be performed if patients are given prolonged therapy32.

Baseline and annual retinal screening are conditionally recommended after starting hydroxychloroquine.

Yearly pediatric screening should be done, rather than waiting 5 years between baseline and subsequent annual screening, as recommended for hydroxychloroquine-treated adults.33 The cumulative and developmental effects of hydroxychloroquine are a concern because children may be on treatment for prolonged periods and may not be able to articulate vision concerns.

Baseline retinal screening should be completed as soon as possible and combined with screening for uveitis when feasible. Treatment does not need to be delayed for initial retinal screening.

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) (all)

CBC and LFTs are conditionally recommended to be monitored annually.

As per package inserts, cytopenias and abnormal LFTs have been reported in association with the use of TNFi. Therefore, minimum yearly evaluation is recommended 34, 35.

Abatacept

Doing no routine laboratory monitoring is conditionally recommended.

In placebo-controlled clinical trials of abatacept for JIA, children had similar CBCs and LFTs irrespective of treatment arms, and no laboratory monitoring is suggested in the package insert36, 37. The decision to monitor labs may be discussed with patients/caregivers who, like some panelists, may prefer routine monitoring to identify potential adverse events, even if rare.

Tocilizumab

CBC and LFTs are conditionally recommended to be monitored within the first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months thereafter.

Lipids are conditionally recommended to be monitored every 6 months, as per package insert.

Altering tocilizumab administration is conditionally recommended after starting tocilizumab if monitoring reveals elevated LFTs (1-3X ULN decrease dose or interval, 3XULN hold dose, 5XULN discontinue treatment), neutropenia (500-1000/mm3), or thrombocytopenia (50,000-100,000/mm3), as per package insert.

As per package insert, it is not recommended to initiate tocilizumab treatment in patients with elevated LFTs >1.5 XULN38. In patients who develop elevated LFTs >5X ULN, treatment should be discontinued. The package insert does state that the decision to discontinue tocilizumab for a laboratory abnormality should be based upon the medical assessment of the individual patient. For that reason, this recommendation is conditional.

Anakinra

CBC and LFTs are conditionally recommended to be monitored within the first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months thereafter.

Abnormal LFTs and neutropenia may occur with the use of anakinra39. For that reason, as well as the severity of the underlying disease, regular monitoring should be performed.

Canakinumab

CBC and LFTs are conditionally recommended to be monitored within the first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months thereafter.

Abnormal LFTs and cytopenias were noted during a phase 3 clinical trial of canakinumab for sJIA40. For that reason, as well as the severity of the underlying disease, regular monitoring should be done.

Tofacitinib

CBC and LFTs are conditionally recommended to be monitored within the first 1-2 months of usage and every 3-4 months thereafter.

Lipids are conditionally recommended to be monitored 1-2 months after starting treatment, as per package insert.

Altering medication administration as per package insert is strongly recommended after starting tofacitinib; medication should be discontinued if hemoglobin is less than 8 g/dl or decreases more than 2 g/dl, or for severe neutropenia (<500/mm3) or lymphopenia (<500/mm3).

Data on tofacitinib was not part of the initial literature review, but the panel felt it important to include this recommendation because tofacitinib was FDA-approved for treatment of JIA in 202041. An additional voting panel session was organized for this purpose.

b). INFECTION SURVEILLANCE

Tuberculosis (TB)

TB screening is conditionally recommended prior to starting biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy and when there is a concern for TB exposure thereafter.

Concern for TB exposure should be interpreted broadly and could include contact with someone with active TB, travel to locations where TB is endemic, contact with high-risk individuals (e.g., prisoners, visitors from TB-endemic areas) or living in communities with a higher frequency of TB42, 43. The conditional recommendation reflects two major concerns:

In certain urgent clinical situations, the harms of waiting for results of TB screening may outweigh the benefits. For example, for a child with active sJIA and macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), treatment should not be delayed pending TB screening results.

Annual screening for TB can pose specific problems for children and families. Insurers or institutions may require a specific method that is potentially problematic44, 45. For example, TB screening may be done by questionnaire; however, this depends on knowledge of exposure. The interferon-gamma release assay (QuantiFERON®-TB Gold) is expensive, not valid for young children and is subject to frequent indeterminate results particularly during anergy. Tuberculin skin testing is user-dependent and inconvenient because two visits are required. In addition, false positive tests often result in unnecessary chest radiographs and isoniazid treatment.

For children living in areas with low prevalence of TB, mandatory annual laboratory-based TB screening represents a high burden of cost, inconvenience and pain that is not supported by the literature reviewed.

Viral infections

Voting panelists could not reach consensus on whether all children with JIA should have antibody titers for specific infections (e.g., measles, varicella, hepatitis B, hepatitis C) checked prior to starting immunosuppressive medication, although more panelists were against this practice than for it. Some panelists felt that the information might be useful for risk management in case of an outbreak or exposure. Most believed that screening a fully immunized child was of low benefit, might delay treatment and incur unnecessary cost. Although screening for Hepatitis B and C is done in adulthood prior to treatment with DMARDs, most children are effectively immunized against Hepatitis B as infants46 and the number of children with Hepatitis C below the age of 19 in the US remains exceedingly low47.

IMMUNIZATIONS

Because some patients/caregivers have concerns about the safety of vaccines in JIA, clinicians must discuss with families the evidence that strongly supports their benefits and safety.

Whenever possible, immunizations should follow the schedule as per the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) or the corresponding national recommendations. As the schedule frequently changes, it is recommended that the clinician follow current recommended immunization schedules48.

Multiple cohort studies have demonstrated that most children with JIA mount a protective response after immunizations and that immunizations do not cause disease flare49–52 .

Annual inactivated influenza immunization is strongly recommended for all children with JIA.

All children with JIA, including children on immunosuppressive medication, should receive inactivated influenza immunizations annually53. Intranasal influenza immunization is contraindicated for children with JIA on immunosuppression as it is a live attenuated immunization. This recommendation is strong despite very low evidence in JIA, given the overwhelming preponderance of supporting literature in other inflammatory diseases and the risk of severe infection.54–57

Immunizations for JIA children not on immunosuppression

Immunizations (live attenuated and inactivated) are strongly recommended for children with JIA not on immunosuppression.

Children with JIA have a higher risk of severe infection compared to unaffected children, making adequate protections against infection essential58.

Immunizations for children on immunosuppression

Considerations of the relative degree of immunosuppression from various immunosuppressive medications used for JIA is beyond the scope of this project. To err on the side of safety, these recommendations apply equally to any child taking an immunosuppressive medication for JIA (e.g., DMARDs, chronic systemic glucocorticoids)59.

Inactivated vaccines are strongly recommended for children with JIA on immunosuppression.

Persons with JIA should receive inactivated vaccines as per location-specific, published age-related schedule. Specifically, children receiving immunosuppression should receive the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in addition to the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine recommended for all children60, 61.

Live attenuated vaccines are conditionally recommended against for JIA children on immunosuppression.

As per the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), severe complications have followed vaccination with certain live attenuated viral and bacterial vaccines among immunosuppressed persons62. Therefore, guidelines recommend that persons with most forms of altered immunocompetence should not receive live attenuated vaccines. As per CDC, providers should defer live-virus vaccination for 1-6 month after discontinuation of immunosuppressive agents, depending on the specific agent62. There is some evidence that booster immunization with live attenuated vaccines may be safe for children with JIA on specific immunosuppressants52, 63. More work is needed to support a formal recommendation in this setting as studies thus far have been underpowered to detect rare, serious harms.

Under-immunized or unimmunized children

Immunization is conditionally recommended for children with active non-systemic JIA who have not yet been immunized for Measles, Mumps, Rubella and/or Varicella prior to starting immunosuppressive medications.

This recommendation excludes active, untreated sJIA where delaying treatment initiation for vaccinations may be prohibitive.

As per the CDC, when initiating immunosuppressive therapy, providers should wait 4 weeks after a live vaccine and ideally 2 weeks after an inactivated vaccine. If holding/delaying medication is not feasible, clinicians should defer live-attenuated vaccine immunization and give at a later time when the child is in remission off medication64.

Vaccines are strongly recommended for household contacts of children with JIA on immunosuppression.

Immunization of household members of immunosuppressed children is critical to diminish exposure in the home. Household contacts and other close contacts of persons with altered immunocompetence should receive all age- and exposure-appropriate vaccines, whether inactivated or live, with the exception of smallpox vaccine59, 65. If family member has received varicella vaccine and develops a rash, direct contact should be avoided until the rash resolves. Likewise, all members of the household should wash their hands after changing the diaper of an infant who received rotavirus vaccine, to minimize transmission. If concerns remain, CDC or local guidelines can be reviewed prior to immunization.

IMAGING

Use of radiographs as a screening test prior to advanced imaging, for the purpose of identifying active synovitis or enthesitis, is strongly recommended against.

Radiographs are not sensitive enough to assess joint inflammation and enthesitis in children and may delay clinically appropriate imaging and treatment66–68. Unnecessary radiation can represent significant harm for developing children69. Conventional x-rays should be restricted to the assessment of JIA-associated damage or to investigate alternative diagnoses.

Imaging guidance is conditionally recommended for use with intra-articular glucocorticoid (IAGC) injections of joints that are difficult to access, or to specifically localize the distribution of inflammation.

This recommendation includes ultrasound and/or fluoroscopy. Specific joints that may be difficult to access include sacroiliac joints, hips, temporomandibular joints (TMJs), shoulder, midfoot and subtalar joints. This recommendation is conditional because it is dependent on the skill of the practitioner, availability of imaging, costs and risk of delay in treatment70–72.

DISCUSSION

The recommendations presented in this guideline are a companion to those published in 20193, 4 and concurrently5 and cover areas not previously addressed for JIA: non-pharmacologic treatments, medication monitoring, immunization and imaging. Similar to recommendations made for oligoarthritis, TMJ arthritis and sJIA with and without MAS, one must view this guideline as a map for future study (see Supplemental Appendix 6). . Most of the available evidence was very low quality for the relevant PICO questions, contributing to 23/33 of the recommendations being conditional. None of the recommendations was supported by moderate or high-quality evidence.

Nowhere is the discrepancy between patient/caregiver interest and available data more evident than in the consideration of non-pharmacologic therapies, for which recommendations were included at patient/parent request. Use of specific diets and supplements were discussed extensively by the patient/caregiver panel, including sharing of suggested regimens and reference materials. There was a general belief that disease manifestations could be ameliorated by changes in foods consumed and great interest in participating in formal research studies on nutritional interventions. Most panelists recognized the importance of PT/OT, and inclusion of PT and OT specialists on the voting panel would allow for more specific recommendations in future guidelines.

Likewise, patients and caregivers discussed the stress of dealing with chronic illness and the need for mental health interventions. As recently as 2017, when the scope of this project was established, mental health care for children and families affected by rheumatic diseases was not a major focus. For this reason, although mental health was recognized by the voting panel as important, it was not formally addressed by this guideline. Future guidelines should include recommendations addressing mental health screening and treatments, with input from mental health professionals on the voting panel. This is particularly important given the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of persons with chronic disease73.

Medication monitoring remains especially challenging for JIA, and balancing safety, cost, pain and inconvenience can be very difficult. Some panel members asserted that monitoring was perhaps less important in a generally healthy pediatric population relative to adults with comorbidities. Due to the low frequency of serious comorbidities and interacting medications, and limited to no exposure to alcohol and other toxins, laboratory abnormalities requiring medication discontinuation are rare in children with JIA. However, other panel members felt strongly that monitoring needed to be routinely performed to identify rare but serious adverse events. Recommendations as written attempted to balance these concerns. Future research and guidelines should consider altered, less frequent monitoring schedules for younger children, given the potentially lower risks of toxicity and greater risks of frequent testing at the youngest ages.

The list of available immunosuppressive medications for JIA that require monitoring has grown substantially and will continue to expand. Two new agents were recently approved for use in polyarticular-course JIA: golimumab, a TNFi, and tofacitinib, a JAK inhibitor41, 74. For laboratory test abnormalities detected on toxicity monitoring, voting panelists could not agree on a single definition of “clinically relevant” tests and left this to the discretion of treating clinicians. Caregivers and patients expressed the challenges of balancing the need to ensure medication safety with the cost and inconvenience associated with blood draws. Hopefully, in the future, effective, reliable treatments requiring less monitoring will be available for JIA.

Voting panelists did feel strongly that screening requirements for infections in the US prior to treatment with DMARDs needed to take age into consideration. TB, Hepatitis B and C are extremely rare in fully immunized nonimmigrant children in the US, and annual TB screening presents a large and unnecessary burden. There were engaged discussions about screening for viral infections prior to the use of DMARDs; however, most thought that lack of immunity in a child known to be immunized was likely to be rare. Even if antibody titers were low or absent after vaccination, cell-mediated immunity was considered likely to be present.

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, discussion of immunizations in these guidelines proved to be extremely timely. Despite the potential severity of vaccine-preventable infections in immunosuppressed populations, vaccine hesitancy remains common. Nonetheless, preventing infectious illnesses in an immunosuppressed population is critical. Many families have concerns regarding vaccine safety, immunogenicity, risk of flare and other potential long-term consequences. Studies in JIA have consistently demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of vaccines to induce protective immune responses. Regarding immunization for COVID-19, at the time of this manuscript, only the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine was approved in the US for adolescents 16-18 years of age75 and authorized for emergency use in children 5-16 years of age.76, 77 No vaccines for COVID are as yet available for younger children, although studies are ongoing. As none of the currently available vaccines against COVID-19 are live vaccines, recommendations should be similar to those stated above for inactivated vaccines. While specific guidance is still lacking on immunizing children with rheumatic diseases against COVID-19, the ACR has published guidance on COVID-19 vaccines for adults with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases78. Patients and families point to the importance of health care providers in providing trustworthy medical information. We must be mindful that clinicians are trusted sources of information about this important public health issue and should discuss immunizations with their patients.

In regards to imaging, it is clear that different modalities are appropriate for different indications. X-rays are not useful for evaluation of soft tissue disease, and continued third-party payor requirement for x-rays prior to any and all MRIs are a waste of resources and a potential hazard for persons with JIA. MRIs themselves may require sedation, and there is concern that repeated sedation in young children may carry risks79 . More research is needed to define and standardize the best approaches to imaging of children with JIA at different times of management.

Addressing each area of the JIA guidelines at the same time proved to be a herculean task. This update of the ACR JIA guidelines has taken 4 years to complete, leading to 4 manuscripts; certain areas are already ready for further updates. Health care around the world is quickly changing in unforeseen ways, and rheumatologists have been thrust into the forefront of recent pandemic developments in an unparalleled fashion80. The pace of change is likely only to increase, and guidelines will need to be updated nimbly and more frequently over time.

The low quality of evidence supporting most these recommendations underscores the importance of clinical judgment and shared decision-making in everyday care of individuals with JIA. Similarly, these guidelines and the many uncertainties therein represent a powerful reminder of the need for more high-quality evidence to support (or refute) current practices and improve the management --and well-being-- of all individuals living with JIA.

In conclusion, these 2021 updated ACR guidelines for JIA recommend the use of PT and OT interventions; a healthy, well-balanced, age-appropriate diet; specific laboratory monitoring for different antirheumatic medications; widespread use and stress the cardinal importance of immunizations; and shared decision-making with patients/caregivers. The JIA guidelines will continue to be updated as new evidence emerges.

Supplementary Material

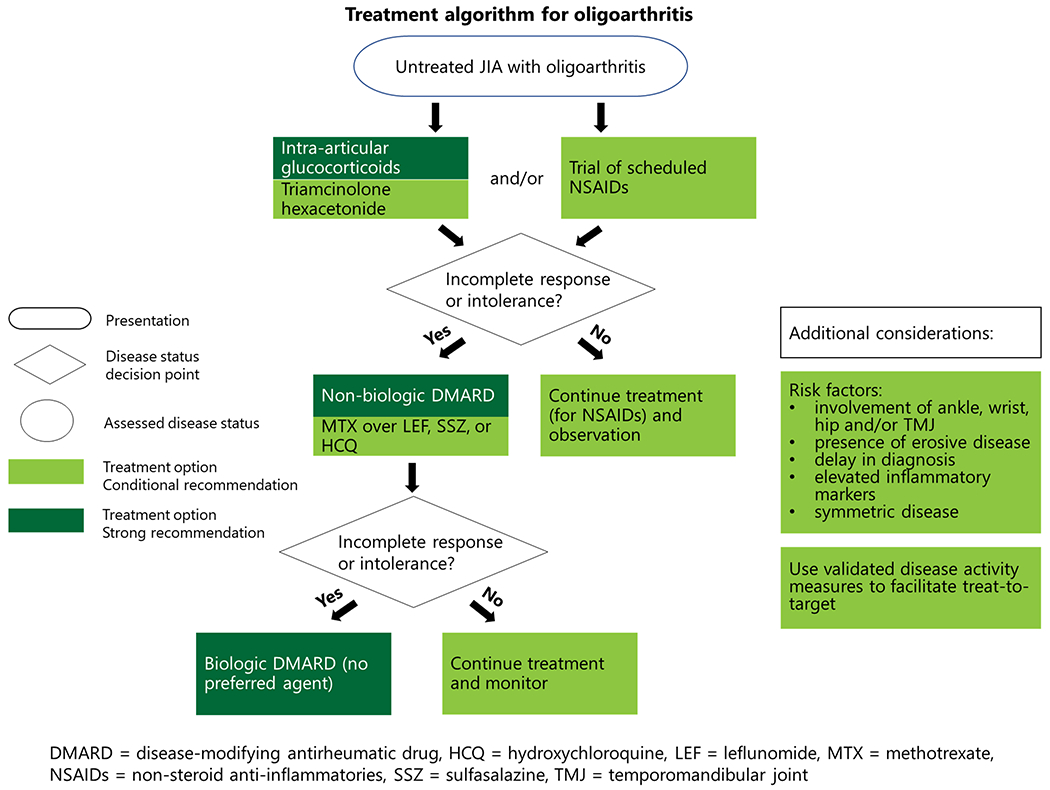

Figure 1.

Treatment algorithm for oligoarthritis

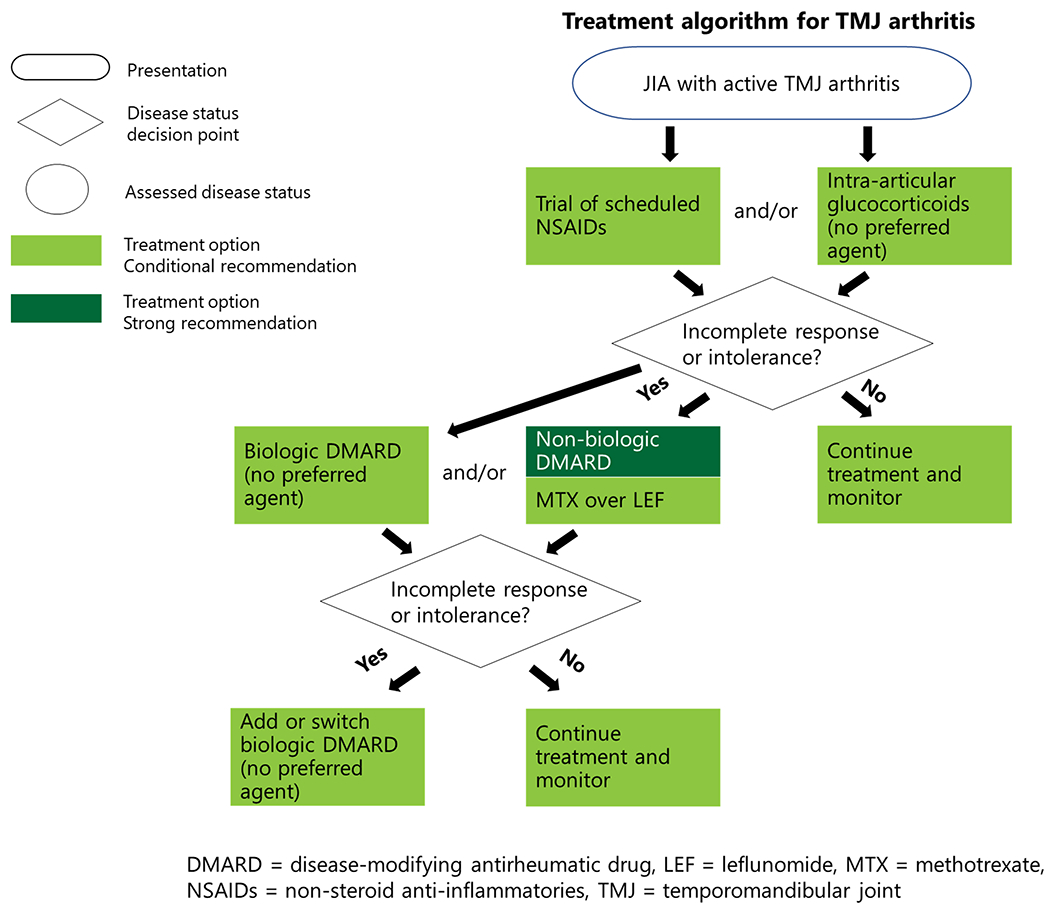

Figure 2.

Treatment algorithm for TMJ arthritis

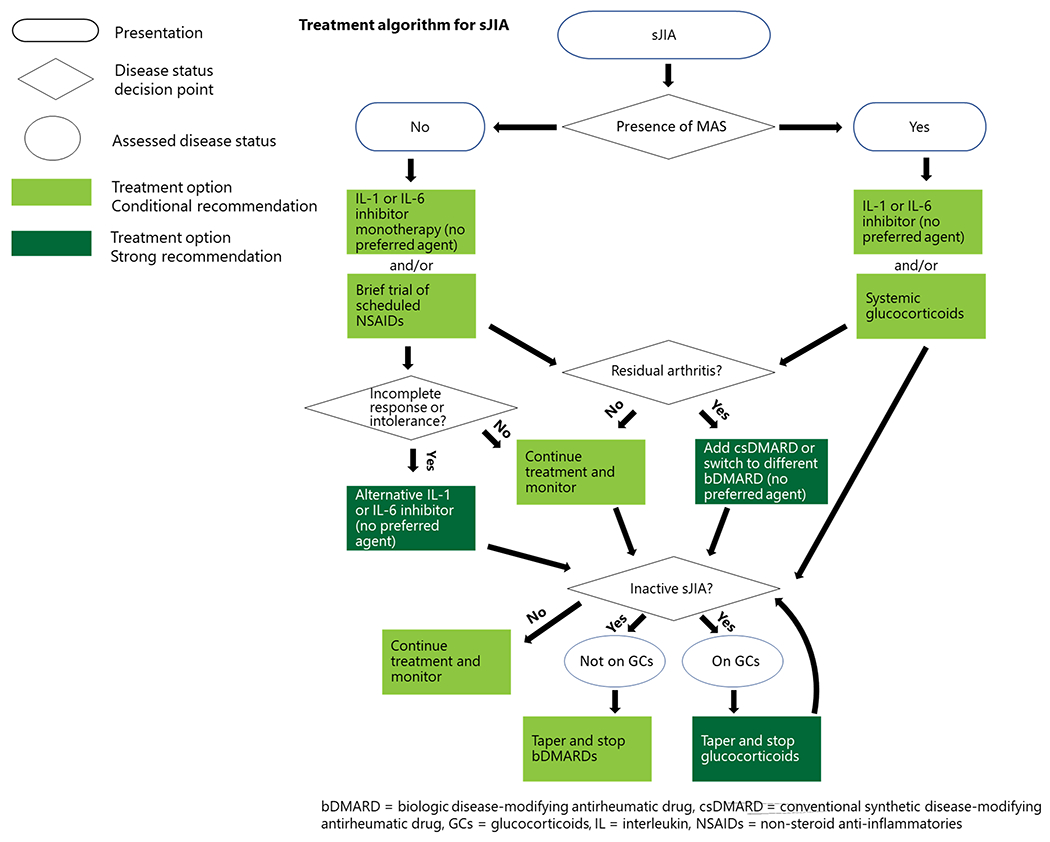

Figure 3.

Treatment algorithm for sJIA

Table 2:

Classes of interventions

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | Any at therapeutic dosing [Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Tolmetin, Indomethacin, Meloxicam, Nabumetone, Diclofenac, Piroxicam, Etodolac, Celecoxib] |

| Conventional synthetic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) | Methotrexate, Sulfasalazine, Hydroxychloroquine, Leflunomide, Calcineurin inhibitors [cyclosporin A, tacrolimus] |

| Biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs) | Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors (TNFi):

Adalimumab, Etanercept, Infliximab, Golimumab, Certolizumab

pegol Other Biologic Response Modifiers (OBRM): Abatacept, Tocilizumab, Anakinra, Canakinumab, |

| Targeted synthetic DMARD (tsDMARD) | JAK inhibitor: Tofacitinib |

| Glucocorticoids | Oral: Any Intravenous: Any Intraarticular: Triamcinolone Acetonide, Triamcinolone Hexacetonide |

| Immunizations | Live

attenuated Inactivated |

| Non-pharmacologic therapies | Physical Therapy

(PT) Occupational Therapy (OT) Dietary changes Herbal supplements |

Table 5:

Infection Surveillance/Immunizations

| Recommendations | Certainty of Evidence | Based on the evidence report(s) of the following PICO(s)7 | Evidence table(s) on page(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No consensus achieved | Very low | PICO 45: Should all children with JIA have infection titers (measles, varicella, hepatitis B, hepatitis C) checked prior to starting immunosuppressive medication? | 164-166 |

| Immunization is conditionally recommended for children with active non-systemic JIA who have not yet been immunized for Measles, Mumps, Rubella and/or Varicella prior to starting immunosuppressive medications. | Very low | PICO 46. Should children with JIA with no evidence of immunity to important infections have a booster immunization prior to starting immunosuppressive medication? | 166 |

| TB screening is conditionally recommended prior to starting biologic DMARD therapy and when there is a concern for TB exposure thereafter. | Very low Very low |

PICO 47: Should screening for TB be done prior

to starting biologic DMARD therapy and then annually in children with

JIA? PICO 48: In children with JIA receiving biologic DMARD therapy, is there a preferred method of TB screening? |

167-169 169-171 |

| Immunizations (live and inactivated) are strongly recommended for children with JIA not on immunosuppression. | Very low | PICO 49. In children with JIA not on immunosuppression, do inactivated or live attenuated vaccines result in flare of disease? | 172-175 |

| Annual influenza immunization is strongly recommended for all children with JIA. | Low | PICO 50. In children with JIA not on

immunosuppression, are patients able to develop protective antibodies

against infections targeted by the vaccine? PICO 52: In children with JIA on immunosuppression, are patients able to develop protective antibodies against infections targeted by the vaccine? |

175 –

179 184-195 |

| Inactivated vaccines are strongly recommended for children with JIA on immunosuppression. | Very low | PICO 51: In children with JIA on immunosuppression, do inactivated vaccines result in flare of disease? | 180-184 |

| Live attenuated vaccines are conditionally recommended against for children with JIA on immunosuppression. | Low | PICO 53. In children with JIA on immunosuppression, can treatment with live attenuated vaccines be given safely (initial dose, booster dose)? | 195-198 |

| Live attenuated vaccines are strongly recommended in the household of children with JIA on immunosuppression as per CDC guidelines. | Very Low | PICO 54. Can live attenuated vaccines be used safely in the households of children with JIA on immunosuppression? | 198 |

Guidelines and recommendations developed and/or endorsed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) are intended to provide general guidance for commonly encountered clinical scenarios. The recommendations do not dictate the care for an individual patient. The ACR considers adherence to the recommendations described in this guideline to be voluntary, with the ultimate determination regarding their application to be made by the clinicians in light of each patient’s individual circumstances. Guidelines and recommendations are intended to promote beneficial or desirable outcomes but cannot guarantee any specific outcome. Guidelines and recommendations developed and endorsed by the ACR are subject to periodic revision as warranted by the evolution of medical knowledge, technology, and practice. ACR recommendations are not intended to dictate payment or insurance decisions, or drug formularies or other third-party analyses. Third parties that cite ACR guidelines should state that these recommendations are not meant for this purpose. These recommendations cannot adequately convey all uncertainties and nuances of patient care. The American College of Rheumatology is an independent, professional, medical and scientific society that does not guarantee, warrant, or endorse any commercial product or service.

SIGNIFICANCE.

These treatment recommendations emphasize:

Non-pharmacologic therapies

Tailored monitoring for medication toxicity by pharmacologic agent

Importance of immunizations for all children with JIA

Judicious use of imaging modalities

Importance of shared decision-making with the patient/caregiver

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Jennifer Horonjeff who (along with author Katherine Murphy) participated in the Patient Panel meeting. We thank the ACR staff, including Regina Parker for assistance in coordinating the administrative aspects of the project and Cindy Force for assistance with manuscript preparation. We thank Janet Waters for her assistance in developing the literature search strategy, as well as performing the initial literature search and update searches.

Grant Support:

This guideline project was supported by the American College of Rheumatology. Dr. Horton was supported by funding from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (K23AR070286). Dr. Ombrello was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (AR041198).

Footnotes

Financial Conflict: Forms submitted as required.

IRB Approval: This study did not involve human subjects and, therefore, approval from Human Studies Committees was not required.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beukelman T, Patkar NM, Saag KG, et al. 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: initiation and safety monitoring of therapeutic agents for the treatment of arthritis and systemic features. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken).2011;63(4):465–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ringold S, Weiss PF, Beukelman T, et al. 2013 update of the 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: recommendations for the medical therapy of children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and tuberculosis screening among children receiving biologic medications. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken).2013;65(10):1551–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringold S, Angeles-Han ST, Beukelman T, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Therapeutic Approaches for Non-Systemic Polyarthritis, Sacroiliitis, and Enthesitis. Arthritis Rheumatol.2019;71(6):846–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angeles-Han ST, Ringold S, Beukelman T, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated Uveitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken).2019;71(6):703–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onel KH D;Shenoi S;. 2021 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA): Therapeutic Approaches for Oligoarthritis, Temporomandibular Joint Arthritis (TMJ), and Systemic JIA, Medication Monitoring, Immunizations and Non-Pharmacologic Therapies. presented at: ACR Convergence; 11/08/2020 2020; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrews JC, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation-determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol.2013;66(7):726–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ.2008;336(7650):924–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ.2010;182(18):E839–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuntze G, Nesbitt C, Whittaker JL, et al. Exercise Therapy in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.2018;99(1):178–193 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarakci E, Arman N, Tarakci D, et al. Leap Motion Controller-based training for upper extremity rehabilitation in children and adolescents with physical disabilities: A randomized controlled trial. J Hand Ther.2020;33(2):220–228 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das JK, Salam RA, Thornburg KL, et al. Nutrition in adolescents: physiology, metabolism, and nutritional needs. Ann N Y Acad Sci.2017;1393(1):21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beluska-Turkan K, Korczak R, Hartell B, et al. Nutritional Gaps and Supplementation in the First 1000 Days. Nutrients.2019;11(12) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LL, et al. Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: a guide for practitioners. Pediatrics.2006;117(2):544–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrander JJ, Marcelis C, de Vries MP, et al. Does food intolerance play a role in juvenile chronic arthritis? Br J Rheumatol.1997;36(8):905–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nousiainen P, Merras-Salmio L, Aalto K, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. BMC Complement Altern Med.2014;14:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gheita T, Kamel S, Helmy N, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: effect on cytokines (IL-1 and TNF-alpha), disease activity and response criteria. Clin Rheumatol.2012;31(2):363–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drechsel P, Studemann K, Niewerth M, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in DMARD-exposed patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis-results from a JIA biologic registry. Rheumatology (Oxford).2020;59(3):603–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer BM. The Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007: drug safety and health-system pharmacy implications. Am J Health Syst Pharm.2009;66(24 Suppl 7):S3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vora SS, Bengtson CE, Syverson GD, et al. An evaluation of the utility of routine laboratory monitoring of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) patients using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): a retrospective review. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J.2010;8:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blecker U, Gold BD. Gastritis and peptic ulcer disease in childhood. Eur J Pediatr.1999;158(7):541–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franova J, Fingerhutova S, Kobrova K, et al. Methotrexate efficacy, but not its intolerance, is associated with the dose and route of administration. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J.2016;14(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kocharla L, Taylor J, Weiler T, et al. Monitoring methotrexate toxicity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol.2009;36(12):2813–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol.2016;68(1):1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunt PG, Rose CD, McIlvain-Simpson G, et al. The effects of daily intake of folic acid on the efficacy of methotrexate therapy in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. A controlled study. J Rheumatol.1997;24(11):2230–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ravelli A, Migliavacca D, Viola S, et al. Efficacy of folinic acid in reducing methotrexate toxicity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol.1999;17(5):625–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sulfasalazine. http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=524

- 27.Imundo LF, Jacobs JC. Sulfasalazine therapy for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol.1996;23(2):360–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Rossum MA, Fiselier TJ, Franssen MJ, et al. Sulfasalazine in the treatment of juvenile chronic arthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Dutch Juvenile Chronic Arthritis Study Group. Arthritis Rheum.1998;41(5):808–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tremblay L, Pineton de Chambrun G, De Vroey B, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome with sulfasalazine treatment: report of two cases. J Crohns Colitis.2011;5(5):457–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leflunomide. https://www.google.com/url?q=http://products.sanofi.us/arava/Arava.html&sa=D&ust=1607360830623000&usg=AOvVaw3f71RYlHwligW-TWRSuoOh

- 31.Baker C, Feinstein JA, Ma X, et al. Variation of the prevalence of pediatric polypharmacy: A scoping review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf.2019;28(3):275–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hydroxychloroquine. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/009768s037s045s047lbl.pdf

- 33.Wei Q, Wang W, Dong Y, et al. Five years follow-up of juvenile lupus nephritis: a single-center retrospective cohort study. Ann Palliat Med.2021;10(7):7351–7359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azevedo VF, Silva MB, Marinello DK, et al. Leukopenia and thrombocytopenia induced by etanercept: two case reports and literature review. Rev Bras Reumatol.2012;52(1):110–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adalimumab. https://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/humira.pdf

- 36.Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P, et al. Abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal trial. Lancet.2008;372(9636):383–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abatacept. https://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_orencia.pdf

- 38.Tocilizumab. https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.gene.com/download/pdf/actemra_prescribing.pdf&sa=D&ust=1607360830625000&usg=AOvVaw2x3SZrb2wJwqhPzOxP90iG

- 39.Diallo A, Mekinian A, Boukari L, et al. [Severe hepatitis in a patient with adult-onset Still’s disease treated with anakinra]. Rev Med Interne.2013;34(3):168–70. Hepatite aigue medicamenteuse a l’anakinra chez une patiente traitee pour une maladie de Still de l’adulte. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruperto N, Brunner HI, Quartier P, et al. Two randomized trials of canakinumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med.2012;367(25):2396–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tofacitinib. https://www.google.com/url?q=http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id%3D959%23section-5.7&sa=D&ust=1607360830550000&usg=AOvVaw3Y7Tg1OelnKbMKuJSAFggU

- 42.CDC TB Guidelines. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/populations/tbinchildren/default.htm#:~:text=TB%20skin%20testing%20is%20considered,than%205%20years%20of%20age.&text=All%20children%20with%20a%20positive,should%20undergo%20a%20medical%20evaluation

- 43.Cowger TL, Wortham JM, Burton DC. Epidemiology of tuberculosis among children and adolescents in the USA, 2007-17: an analysis of national surveillance data. Lancet Public Health.2019;4(10):e506–e516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaensbauer J, Young J, Harasaki C, et al. Interferon-Gamma Release Assay Testing in Children Younger Than 2 Years in a US-Based Health System. Pediatr Infect Dis J.2020;39(9):803–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boncuoglu E, Kiymet E, Sahinkaya S, et al. Usefulness of screening tests for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in children. Pediatr Pulmonol.2021;56(5):1114–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hino K, Katoh Y, Vardas E, et al. The effect of introduction of universal childhood hepatitis B immunization in South Africa on the prevalence of serologically negative hepatitis B virus infection and the selection of immune escape variants. Vaccine.2001;19(28-29):3912–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryerson AB, Schillie S, Barker LK, et al. Vital Signs: Newly Reported Acute and Chronic Hepatitis C Cases - United States, 2009-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2020;69(14):399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robinson CL, Bernstein H, Poehling K, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children and Adolescents Aged 18 Years or Younger - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2020;69(5):130–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aikawa NE, Trudes G, Campos LM, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of two doses of a non-adjuvanted influenza A H1N1/2009 vaccine in young autoimmune rheumatic diseases patients. Lupus.2013;22(13):1394–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Toplak N, Subelj V, Kveder T, et al. Safety and efficacy of influenza vaccination in a prospective longitudinal study of 31 children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol.2012;30(3):436–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heijstek MW, Scherpenisse M, Groot N, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the bivalent HPV vaccine in female patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a prospective controlled observational cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis.2014;73(8):1500–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heijstek MW, Kamphuis S, Armbrust W, et al. Effects of the live attenuated measles-mumps-rubella booster vaccination on disease activity in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomized trial. JAMA.2013;309(23):2449–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, 2020-21 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep.2020;69(8):1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benchimol EI, Hawken S, Kwong JC, et al. Safety and utilization of influenza immunization in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Pediatrics.2013;131(6):e1811–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Papp KA, Haraoui B, Kumar D, et al. Vaccination Guidelines for Patients With Immune-Mediated Disorders on Immunosuppressive Therapies. J Cutan Med Surg.2019;23(1):50–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ogimi C, Tanaka R, Saitoh A, et al. Immunogenicity of influenza vaccine in children with pediatric rheumatic diseases receiving immunosuppressive agents. Pediatr Infect Dis J.2011;30(3):208–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Furer V, Rondaan C, Heijstek MW, et al. 2019 update of EULAR recommendations for vaccination in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis.2020;79(1):39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beukelman T, Xie F, Chen L, et al. Rates of hospitalized bacterial infection associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and its treatment. Arthritis Rheum.2012;64(8):2773–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Immunizations and Immunosuppression. https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/immunocompetence.html&sa=D&ust=1607360830423000&usg=AOvVaw1PdJggmI3YSUxGLjspiivV

- 60.Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2012;61(40):816–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strikas RA, Centers for Disease C, Prevention, et al. Advisory committee on immunization practices recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years--United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2015;64(4):93–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis.2014;58(3):309–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uziel Y, Moshe V, Onozo B, et al. Live attenuated MMR/V booster vaccines in children with rheumatic diseases on immunosuppressive therapy are safe: Multicenter, retrospective data collection. Vaccine.2020;38(9):2198–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.American Academy of Pediatrics. Immunization in special clinical circumstances. In: Pickering L BC, Kimberlin D, Long S, eds, ed. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28 ed. American Academy of Pediatrics. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petersen BW, Damon IK, Pertowski CA, et al. Clinical guidance for smallpox vaccine use in a postevent vaccination program. MMWR Recomm Rep.2015;64(RR-02):1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oren B, Oren H, Osma E, et al. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: cervical spine involvement and MRI in early diagnosis. Turk J Pediatr.1996;38(2):189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Malattia C, Damasio MB, Pistorio A, et al. Development and preliminary validation of a paediatric-targeted MRI scoring system for the assessment of disease activity and damage in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis.2011;70(3):440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sureda D, Quiroga S, Arnal C, et al. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis of the knee: evaluation with US. Radiology.1994;190(2):403–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berrington de Gonzalez A, Darby S. Risk of cancer from diagnostic X-rays: estimates for the UK and 14 other countries. Lancet.2004;363(9406):345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Young CM, Shiels WE 2nd , Coley BD, et al. Ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injection therapy for juvenile idiopathic arthritis: 12-year care experience. Pediatr Radiol.2012;42(12):1481–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laurell L, Court-Payen M, Nielsen S, et al. Ultrasonography and color Doppler in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: diagnosis and follow-up of ultrasound-guided steroid injection in the wrist region. A descriptive interventional study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J.2012;10:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Resnick CM, Vakilian PM, Kaban LB, et al. Is Intra-Articular Steroid Injection to the Temporomandibular Joint for Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis More Effective and Efficient When Performed With Image Guidance? J Oral Maxillofac Surg.2017;75(4):694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Adnine A, Nadiri K, Soussan I, et al. Mental health problems experienced by patients with rheumatic diseases during COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Rheumatol Rev.2021; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Golimumab. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/news/fda-approves-golimumab-for-active-polyarticular-juvenile-idiopathic-arthritis-extension-of-psa-indication.

- 75.COVID APPROVAL. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine

- 76.COVIDEUA 5-11. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine-emergency-use-children-5-through-11-years-age

- 77.COVID EUA 12-18. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine-emergency-use

- 78.Curtis JR, Johnson SR, Anthony DD, et al. American College of Rheumatology Guidance for COVID-19 Vaccination in Patients With Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases: Version 3. Arthritis Rheumatol.2021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-approves-label-changes-use-general-anesthetic-and-sedation-drugs .

- 80.Henderson LA, Canna SW, Friedman KG, et al. American College of Rheumatology Clinical Guidance for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated With SARS-CoV-2 and Hyperinflammation in Pediatric COVID-19: Version 2. Arthritis Rheumatol.2021;73(4):e13–e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.