This cohort study analyzes biomarker data for patients with ERBB2-positive breast cancer to determine the association between circulating cardiomyocyte cell-free DNA and subsequent cancer therapy–related cardiac dysfunction after anthracycline chemotherapy and ERBB2-targeted therapy.

Key Points

Question

What is the association between circulating cardiomyocyte cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and subsequent cancer therapy–related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) in patients with ERBB2-positive breast cancer receiving anthracycline chemotherapy and ERBB2-targeted therapy?

Findings

In this cohort study, a biomarker analysis showed that the level of circulating cardiomyocyte cfDNA was elevated after completion of anthracyclines and was associated with risk of subsequent CTRCD.

Meaning

Circulating cardiomyocyte cfDNA may be an early predictive biomarker of CTRCD that could be used to risk-stratify patients with breast cancer who are receiving cardiotoxic cancer therapy, and it warrants further validation.

Abstract

Importance

Cancer therapy–related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) is a potentially serious cardiotoxicity of treatments for ERBB2-positive breast cancer (formerly HER2). Identifying early biomarkers of cardiotoxicity could facilitate an individualized approach to cardiac surveillance and early pharmacologic intervention. Circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) of cardiomyocyte origin is present during acute cardiac injury but has not been established as a biomarker of CTRCD.

Objective

To determine whether circulating cardiomyocyte cfDNA is associated with CTRCD in patients with ERBB2-positive breast cancer treated with anthracyclines and ERBB2-targeted therapy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A prospective cohort of 80 patients with ERBB2-positive breast cancer enrolled at an academic cancer center between July 2014 and April 2016 underwent echocardiography and blood collection at baseline, after receiving anthracyclines, and at 3 months and 6 months of ERBB2-targeted therapy. Participants were treated with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy followed by trastuzumab (+/− pertuzumab). The current biomarker study includes participants with sufficient biospecimen available for analysis after anthracycline therapy. Circulating cardiomyocyte-specific cfDNA was quantified by a methylation-specific droplet digital polymerase chain reaction assay. Data for this biomarker study were collected and analyzed from June 2021 through April 2022.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The outcome of interest was 1-year CTRCD, defined by symptomatic heart failure or an asymptomatic decline in left ventricular ejection fraction (≥10% from baseline to less than lower limit of normal or ≥16%). Values for cardiomyocyte cfDNA and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) measured after patients completed treatment with anthracyclines were compared between patients who later developed CTRCD vs patients who did not using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, and the association of post-anthracycline cardiomyocyte cfDNA level with CTRCD was estimated using logistic regression.

Results

Of 71 patients included in this study, median (IQR) age was 50 (44-58) years, all were treated with dose-dense doxorubicin, and 48 patients underwent breast radiotherapy. Ten of 71 patients (14%) in this analysis developed CTRCD. The level of cardiomyocyte cfDNA at the post-anthracycline time point was higher in patients who subsequently developed CTRCD (median, 30.5 copies/mL; IQR, 24-46) than those who did not (median, 7 copies/mL; IQR, 2-22; P = .004). Higher cardiomyocyte cfDNA level after completion of anthracycline chemotherapy was associated with risk of CTRCD (hazard ratio, 1.02 per 1-copy/mL increase; 95% CI, 1.00-1.03; P = .046).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found that higher cardiomyocyte cfDNA level after completion of anthracycline chemotherapy was associated with risk of CTRCD. Cardiomyocyte cfDNA quantification shows promise as a predictive biomarker to refine risk stratification for CTRCD among patients with breast cancer receiving cardiotoxic cancer therapy, and its use warrants further validation.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02177175

Introduction

Anthracyclines and therapy that targets ERBB2 (formerly HER2) are important therapeutic classes used to treat ERBB2-positive breast cancer, but both are associated with a risk of cardiotoxicity especially when used in combination. Cancer therapy–related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) is the most common clinical manifestation of cardiotoxicity in asymptomatic decline of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) or clinical heart failure. Risk factors for CTRCD include older age, hypertension, obesity, Black race, and other multiple cardiotoxic exposures (eg, anthracyclines, radiotherapy, or ERBB2-targeted therapy); however, clinical factors alone are insufficient for predicting which patients are at increased risk.1,2,3

Circulating biomarkers may allow for more precise risk stratification for CTRCD and identify patients who would benefit from cardioprotective medications or increased cardiac surveillance. Circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) is a promising new biomarker in oncology.4 Dead cells release genomic DNA into the bloodstream, where it circulates as cfDNA and is detected with high sensitivity. The patterns of DNA methylation, a common epigenetic modification, are highly tissue-specific and can be resolved by bisulfite treatment. This approach has identified elevated cardiomyocyte cfDNA after myocardial injury by myocardial infarction or sepsis.5,6 The goal of this study was to explore the utility of cardiomyocyte cfDNA in monitoring cardiac safety and identifying patients at risk for developing CTRCD during ERBB2-positive breast cancer treatment.

Methods

The current analysis describes a biomarker study to evaluate the association of cardiomyocyte cfDNA with risk for CTRCD during therapy for ERBB2-targeted breast cancer. It includes data from a clinical trial that enrolled patients from July 2014 and April 2016 (NCT02177175). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center institutional review board.

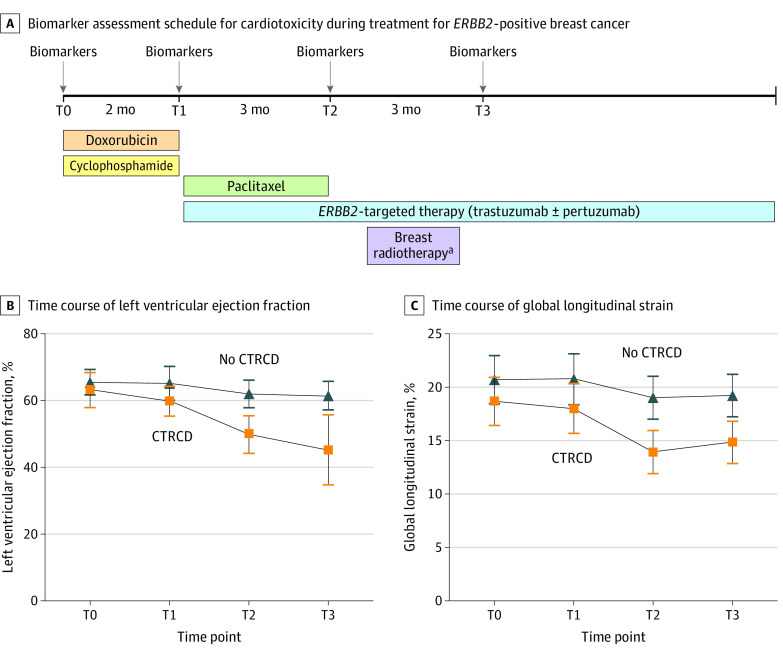

Eighty patients 18 years or older with ERBB2-positive breast cancer were treated with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy followed by trastuzumab (+/− pertuzumab). Blood specimens were collected before doxorubicin (the time point hereafter referred to as T0) and immediately before and after ERBB2-targeted therapy infusion at initiation (T1), month 3 (T2), and month 6 (T3) (Figure 1). Patients with sufficient blood sample volume at T1 for cardiomyocyte cfDNA measurement were eligible for the biomarker study. Biomarker data were analyzed from June 2021 through April 2022. Data about participant race were self-reported at trial enrollment and were categorized by researchers as either Asian, Black, or White.

Figure 1. Biomarker Assessment for Cardiotoxicity During Treatment for ERBB2-Positive Breast Cancer.

Participants in this study received a standard treatment regimen consisting of dose-dense doxorubicin with cyclophosphamide, followed by paclitaxel and trastuzumab (+/− pertuzumab). Biomarkers were measured at the following time points: before doxorubicin (T0), after doxorubicin (T1), and 3 months (T2) and 6 months (T3) after ERBB2-targeted therapy. At T1, T2, and T3, biomarkers were measured before and after administration of ERBB2-targeted treatment. Echocardiograms were performed before doxorubicin, after doxorubicin, and every 3 months during ERBB2-targeted therapy. Panels B and C show the time course of left ventricular ejection fraction and global longitudinal strain among participants with and without cancer therapy–related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) during ERBB2-positive breast cancer treatment.

aForty-seven of 71 participants received breast radiotherapy beginning approximately 4 weeks after completion of paclitaxel.

The primary outcome was 1-year CTRCD, defined by clinical heart failure (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class III/IV) or an asymptomatic drop in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, ≥10% from baseline to less than the lower limit of normal or ≥16%).7 One-year follow-up data were available for all patients enrolled in the study.

A digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) assay to quantify cardiomyocyte cfDNA was performed as described elsewhere (eMethods in Supplement 1).6 Briefly, cfDNA was isolated from plasma and bisulfite converted. Two TaqMan probes specific for unmethylated FAM101A fragments were used to detect cardiomyocyte cfDNA by ddPCR, and values were transformed to number of copies per milliliter of plasma. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) was measured using a single-molecule counting assay (Erenna immunoassay system, Singulex), with a lower limit of detection of 0.1 ng/L and a 99th percentile reference limit of 6 ng/L in healthy individuals.8

Two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography were performed at time points T0 through T3 using a Vivid E9 ultrasound scanner (GE Medical Systems).9 Speckle tracking strain analysis was performed offline (EchoPAC; GE HealthCare) by a single observer (A.F.Y.) as previously described10 and absolute values reported.

Categorical variables are summarized as frequency and percentage and continuous variables as median (IQR). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test assessed for differences in biomarker levels between time points. To evaluate the role of cardiomyocyte cfDNA for identifying patients at risk for CTRCD, the primary analysis focused on biomarker measurements at T1 (post-anthracycline), based on prior studies.11 Maximum levels of cardiomyocyte cfDNA and hs-cTnI at study time points were compared between patients with and without subsequent CTRCD using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between maximum biomarker levels at T1 and CTRCD. Pearson correlation coefficients assessed the relationship between cfDNA and hs-cTnI across all samples. Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1 (GraphPad Software) and Stata version 12 (StataCorp).

Results

Of 71 patients included in this study, median (IQR) age was 50 (44-58) years, all were treated with dose-dense doxorubicin, and 48 patients underwent breast radiotherapy (Table and Figure 1A). Median (IQR) LVEF decreased from 65% (63%-68%) at T0 to 61% (56%-64%) at T3 (P < .001), and median (IQR) global longitudinal strain decreased from 20.3% (19.2%-22.2%) at T0 to 18.8% (17.3%-20.5%) at T3 (P < .001) (Figure 1B and C). Ten patients (14%) developed CTRCD a median (IQR) of 4 (3-5) months after the start of trastuzumab: 2 developed clinical heart failure (NYHA class III), and 8 developed a significant drop in LVEF. Baseline LVEF and global longitudinal strain among patients who developed CTRCD compared with those who did not was 63% vs 66% (P = .18) and 18.8% vs 20.7% (P = .03), respectively.

Table. Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cohort (n = 71) | No CTRCD (n = 61) | CTRCD (n = 10) | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 50 (44-58) | 49 (43-58) | 55 (47-57) | .18 |

| Body mass index, median (IQR)b | 26 (24-30) | 26 (23-30) | 27 (27-30) | .18 |

| Body mass index group | ||||

| <25 | 27 (38) | 25 (41) | 2 (20) | .26 |

| 25-29 | 27 (38) | 21 (34) | 6 (60) | |

| ≥30 | 17 (24) | 15 (25) | 2 (20) | |

| Breast cancer stage | ||||

| I | 6 (8) | 4 (7) | 2 (20) | .23 |

| II | 53 (75) | 47 (77) | 6 (60) | |

| III | 12 (17) | 10 (16) | 2 (20) | |

| Radiation therapy | ||||

| Left | 27 (38) | 23 (38) | 4 (40) | >.99 |

| Right | 21 (30) | 18 (30) | 3 (30) | |

| Mean heart dose, median (IQR), Gyc | 0.9 (0.4-2.5) | 1.0 (0.6-4.0) | 0 (0-1.1) | |

| Cumulative doxorubicin dose, median (IQR), mg/m2 | 240 (240-240) | 240 (240-240) | 240 (240-240) | .41 |

| ERBB2-targeted treatment regimen | ||||

| Trastuzumab | 5 (7) | 4 (7) | 1 (10) | .54 |

| Trastuzumab + pertuzumab | 66 (93) | 57 (93) | 9 (90) | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, median (IQR), % | 65 (63-68) | 66 (63-68) | 63 (60-68) | .18 |

| Global longitudinal strain, median (IQR), % | 20.3 (19.2-22.2) | 20.7 (19.3-22.3) | 18.8 (16.7-19.8) | .03 |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure | .28 | |||

| <130 mm Hg | 48 (68) | 43 (70) | 5 (50) | |

| ≥130 mm Hg | 23 (32) | 18 (30) | 5 (50) | |

| Hypertension | 12 (17) | 10 (16) | 2 (20) | .67 |

| Diabetes | 7 (10) | 6 (10) | 1 (10) | >.99 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 6 (8) | 4 (7) | 2 (20) | .20 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (10) | .14 |

| Smoking (current or former) | 23 (32) | 17 (28) | 6 (60) | .07 |

| Cardiac medications | ||||

| β-Blockers | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | 1 (10) | .37 |

| ACEI/ARB | 7 (10) | 5 (8) | 2 (20) | .25 |

| Raced | .18 | |||

| Asian | 11 (15) | 11 (18) | 0 | |

| Black | 11 (15) | 8 (13) | 3 (30) | |

| White | 49 (70) | 42 (69) | 7 (70) | |

| Cardiomyocyte cfDNA, median (IQR), copies/mLe | ||||

| T0 | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 1 (0-5) | .06 |

| T1 | 10 (2-27) | 7 (2-22) | 31 (24-46) | .004 |

| T2 | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-0) | .18 |

| T3 | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-2) | .66 |

| hs-cTnI, median (IQR), ng/Le | ||||

| T0 | 0.3 (0.2-0.7) | 0.3 (0.2-0.7) | 0.5 (0.2-0.7) | .56 |

| T1 | 8.4 (4.6-16.2) | 6.8 (4.6-13.3) | 15.9 (8.6-25.1) | .10 |

| T2 | 6.9 (4.3-11.2) | 5.6 (4.2-11.2) | 9.9 (7.4-16.2) | .22 |

| T3 | 3.0 (2.1-5.3) | 2.9 (2.2-5.6) | 3.1 (1.7-4.2) | .40 |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; cfDNA, cell-free DNA; CTRCD, cancer therapy–related cardiac dysfunction; hs-cTnI, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I.

P values were calculated by Fisher exact test for categorical variables or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Radiation dosimetry was available for 44 of 48 patients.

Race was self-reported at trial enrollment.

For T1-T3, biomarker levels represent maximum values at each time point.

Cardiomyocyte cfDNA increased from a median of 0 copies/mL at T0 (prior to doxorubicin) to 10 copies/mL at T1 (after completion of doxorubicin) and subsequently decreased to a median of 0 copies/mL at T2 and T3 (Table). Similarly, median hs-cTnI was 0.3 ng/L at T0, increased to 8.4 ng/L at T1, and subsequently declined at T2 (median, 6.9 ng/L) and T3 (median, 3.0 ng/L) but remained above baseline levels (eFigure in Supplement 1).

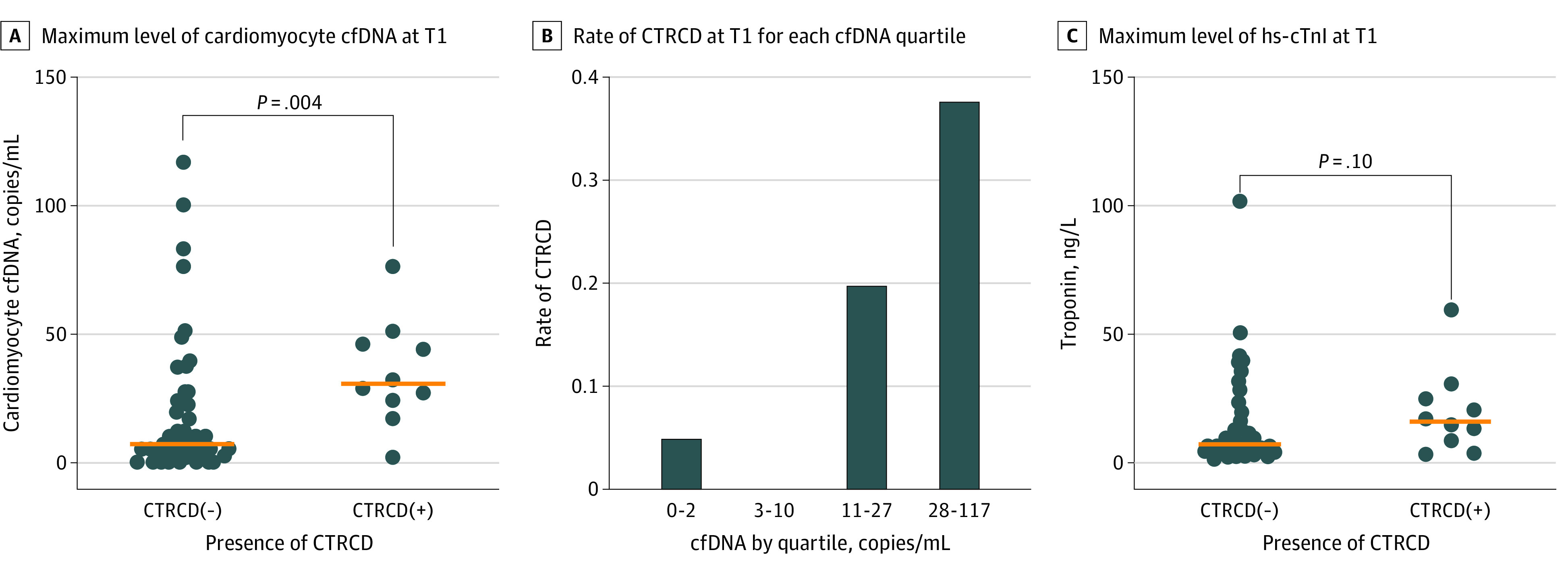

We examined whether maximum biomarker levels at T1 differed between patients who developed CTRCD compared with those who did not. Median (IQR) cardiomyocyte cfDNA at T1 was 30.5 (24-46) copies/mL in patients who developed CTRCD compared with 7 (2-22) copies/mL in patients without CTRCD (P = .004) (Figure 2A). In a sensitivity analysis, we considered the sum of cardiomyocyte cfDNA copies measured at T1 (in the preinfusion and postinfusion specimens). This yielded similar results to the primary analysis, revealing higher cardiomyocyte cfDNA in patients who developed CTRCD compared with those who did not (eFigure in Supplement 1). The risk of CTRCD was significantly associated with cardiomyocyte cfDNA at T1, with an odds ratio of 1.02 (95% CI, 1.00-1.05; P = .048) per 1 copy/mL increase. Clinically relevant thresholds for cardiomyocyte cfDNA are currently unknown. Thus, we assessed the number of patients who developed CTRCD in each quartile of cardiomyocyte cfDNA at T1 to gain insight into the clinical significance of cardiomyocyte cfDNA levels. We observed a graded association between CTRCD and increasing cardiomyocyte cfDNA at T1; 6 patients (38%) in the highest quartile (28-117 copies/mL) developed CTRCD compared with 1 patient (5%) in the lowest quartile (0-2 copies/mL) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Differences in Biomarkers in Patients With and Without Cancer Therapy–Related Cardiac Dysfunction (CTRCD).

A, Maximum cardiomyocyte circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) level detected at T1 in patients with CTRCD vs those without CTRCD. The horizontal line indicates the median value; P = .004 by Wilcoxon rank sum test. B, Rate of CTRCD in each quartile of maximum cardiomyocyte-specific cfDNA level at time point T1 after completion of anthracycline chemotherapy. Q1 = 0-2 copies/mL; Q2 = 3-10 copies/mL; Q3 = 11-27 copies/mL; Q4 = 28-117 copies/mL. C, Maximum high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) at T1 in patients with CTRCD vs those without CTRCD. The horizontal line indicates the median value; P = .10 by Wilcoxon rank sum test.

We also explored the association of hs-cTnI level with the development of CTRCD in a similar analysis. Median hs-cTnI at T1 was 15.9 ng/L in the group who developed CTRCD compared with 6.8 ng/L in the group without CTRCD (P = .10) (Figure 2C). An elevated hs-cTnI value (≥6 ng/L) was not associated with risk of CTRCD (hazard ratio, 2.22; 95% CI, 0.47-10.49). We then assessed the correlation between cardiomyocyte cfDNA and hs-cTnI. Across all samples, cardiomyocyte cfDNA copies and hs-cTnI values were weakly correlated (R2 = 0.014).

Discussion

In this prospective study, we explored for the first time to our knowledge the association between cardiomyocyte cfDNA and CTRCD during treatment for ERBB2-positive breast cancer. The primary findings of this study were that (1) cardiomyocyte cfDNA peaked after completion of anthracycline chemotherapy and (2) higher cardiomyocyte cfDNA at this time point was associated with CTRCD risk. This study builds on prior reports of circulating cardiomyocyte cfDNA as a marker of myocardial injury and heart failure6,12 and supports cardiomyocyte cfDNA as a novel biomarker for risk stratification of CTRCD.

Our findings complement existing evidence that troponin levels after completing anthracycline chemotherapy are associated with CTRCD risk.11,13 Although the time course of changes in hs-cTnI and cardiomyocyte cfDNA was similar in this study, the correlation between cardiomyocyte cfDNA and hs-cTnI was poor, suggesting that cardiomyocyte cfDNA and hs-cTnI may be suited to detect different pathologic processes in the myocardium. This may be explained by differing mechanisms of release of cfDNA and troponin from injured or dead cardiomyocytes.14,15

Limitations

This study was limited by its small sample size and need for validation studies. In several patients we observed differences in cardiomyocyte cfDNA from samples collected hours apart. Potential causes include the short half-life of cfDNA, variable sample processing, insufficient sample volume, or the direct effect of trastuzumab, which was delivered between sample collections, and thus the optimal time for biomarker assessment remains uncertain. Not all patients with elevated cardiomyocyte cfDNA at T1 developed CTRCD, although we noted subclinical echocardiographic changes (ie, diastolic dysfunction) among some of these patients that did not meet our prespecified CTRCD criteria. Future studies are needed to determine whether elevated cardiomyocyte cfDNA is associated with physiologic changes in the heart beyond left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Finally, criteria for CTRCD were based on a significant change in LVEF that exceeds the standard variability of LVEF measurement, and all studies were performed in a single echocardiography laboratory using standardized acquisition protocols and interpreted by a group of core readers; however, we cannot exclude the potential for variability in LVEF measurements.

Conclusions

This study found that higher cardiomyocyte cfDNA level after completion of anthracycline chemotherapy was associated with risk of CTRCD. Much is still unknown about the mechanisms of cardiotoxicity after cancer therapy, and further study of cardiomyocyte cfDNA could be revealing. Findings from this study should encourage further investigation to define the role of cardiomyocyte cfDNA as a predictive biomarker for CTRCD from anthracyclines, ERBB2-targeted therapy, and other cardiotoxic cancer therapies.

eMethods

eFigure. Levels of cardiomyocyte cfDNA and high-sensitivity troponin I

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Armenian SH, Lacchetti C, Barac A, et al. Prevention and monitoring of cardiac dysfunction in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):893-911. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Sadawi M, Hussain Y, Copeland-Halperin RS, et al. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in cardiotoxicity among women with HER2-positive breast cancer. Am J Cardiol. 2021;147:116-121. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guenancia C, Lefebvre A, Cardinale D, et al. Obesity as a risk factor for anthracyclines and trastuzumab cardiotoxicity in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(26):3157-3165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.4846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corcoran RB, Chabner BA. Application of cell-free DNA analysis to cancer treatment. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(18):1754-1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1706174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss J, Magenheim J, Neiman D, et al. Comprehensive human cell-type methylation atlas reveals origins of circulating cell-free DNA in health and disease. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5068. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07466-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zemmour H, Planer D, Magenheim J, et al. Non-invasive detection of human cardiomyocyte death using methylation patterns of circulating DNA. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1443. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03961-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1673-1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estis J, Wu AHB, Todd J, Bishop J, Sandlund J, Kavsak PA. Comprehensive age and sex 99th percentiles for a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I assay. Clin Chem. 2018;64(2):398-399. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.276972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. ; Chamber Quantification Writing Group; American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee; European Association of Echocardiography . Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440-1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu AF, Ho AY, Braunstein LZ, et al. Assessment of early radiation-induced changes in left ventricular function by myocardial strain imaging after breast radiation therapy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019;32(4):521-528. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2018.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ky B, Putt M, Sawaya H, et al. Early increases in multiple biomarkers predict subsequent cardiotoxicity in patients with breast cancer treated with doxorubicin, taxanes, and trastuzumab. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(8):809-816. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yokokawa T, Misaka T, Kimishima Y, Shimizu T, Kaneshiro T, Takeishi Y. Clinical significance of circulating cardiomyocyte-specific cell-free DNA in patients with heart failure: a proof-of-concept study. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(6):931-935. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zardavas D, Suter TM, Van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Role of troponins I and T and N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide in monitoring cardiac safety of patients with early-stage human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer receiving trastuzumab: a herceptin adjuvant study cardiac marker substudy. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):878-884. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu H, Wang Z. Cardiomyocyte-derived exosomes: biological functions and potential therapeutic implications. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1049. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabuschnig S, Bronkhorst AJ, Holdenrieder S, et al. Putative origins of cell-free DNA in humans: a review of active and passive nucleic acid release mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21):8062. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eFigure. Levels of cardiomyocyte cfDNA and high-sensitivity troponin I

Data sharing statement