Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease is neuropathologically characterized by the deposition of the amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) as amyloid plaques. Aβ plaque pathology starts in the neocortex before it propagates into further brain regions. Moreover, Aβ aggregates undergo maturation indicated by the occurrence of post-translational modifications. Here, we show that propagation of Aβ plaques is led by presumably non-modified Aβ followed by Aβ aggregate maturation. This sequence was seen neuropathologically in human brains and in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice receiving intracerebral injections of human brain homogenates from cases varying in Aβ phase, Aβ load and Aβ maturation stage. The speed of propagation after seeding in mice was best related to the Aβ phase of the donor, the progression speed of maturation to the stage of Aβ aggregate maturation. Thus, different forms of Aβ can trigger propagation/maturation of Aβ aggregates, which may explain the lack of success when therapeutically targeting only specific forms of Aβ.

Keywords: amyloid β protein, Alzheimer’s disease, mouse model, human brain, seeding, maturation and propagation

Li et al. identify molecular features of amyloid plaques that affect their propagation and consolidation in the brain. Taking these factors into account when developing amyloid-targeting therapies could pave the way to better outcomes for patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is the most frequent form of dementia in the elderly.1 The deposition of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ)-containing senile plaques and the generation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) composed of abnormal phosphorylated τ protein (p-τ) are the two main histopathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease.2–4 The propagation of senile plaques and NFTs from one brain region into another follows distinct hierarchical and predictable patterns.5,6 The sequence that describes the topographical spreading of Aβ-plaque pathology in the human brain is referred to as Aβ phases6 and can also be found in mouse models of Aβ pathology such as mutant human amyloid precursor protein (APP) overexpressing mice.7 Experimental evidence showed that both Aβ and p-τ propagate from one brain region into others by following neuronal connections.6,8–11

The progression of Alzheimer’s disease is also accompanied by changes in the composition of Aβ plaques indicated by the sequential occurrence of post-translationally modified forms of Aβ, which is here referred to as maturation.12 This sequence was described as Aβ maturation (B-Aβ) stages. Newly developed Aβ plaques, as found in the first phase of Aβ deposition in the neocortex, most frequently consist only of Aβ that can be detected with antibodies raised against non-modified Aβ. Post-translationally modified forms of Aβ, such as N-terminal truncated and pyroglutamate modified Aβ (AβN3pE) and phosphorylated Aβ (AβpSer8) either occur in a later preclinical stage (AβN3pE) or are mainly restricted to symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease (AβpSer8).12,13 Other authors use the term maturation in the context of the development of amyloid plaques from diffuse to cored plaques.14 Whether this maturation goes along with that of the changes in the biochemical composition (B-Aβ aggregate maturation) has not yet been reported in detail.

A prion-like seeding process is considered to be one of the mechanisms underlying the induction and propagation of the Aβ pathology in the brain.15,16 Moreover, transmission of Aβ deposition has been described in transgenic mouse models,17,18 non-human primates19 and patients receiving Aβ-positive brain extracts via human-derived growth hormone treatment, cadaveric dura grafts or previous neurosurgery.20–22 In these cases, Aβ deposition can be induced and was mainly found in blood vessels. These findings suggest that seeding of Aβ pathology is an important event in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and possibly involved in propagation of Aβ pathology throughout the brain.

Soluble and insoluble Aβ preparations from human Alzheimer’s disease brain homogenates as well as distinct synthetic Aβ strains have been shown to induce seeding in a concentration-dependent manner.17,23–25 However, it is not yet clear whether the maturation stage of seeds has influence on seed-induced propagation and maturation of Aβ plaque pathology. This becomes of increasing interest in the light of antibodies against AβN3pE that are now entering phase 3 trials.26 Since it is theoretically possible to halt the maturation process of Aβ aggregate formation by tackling AβN3pE, it appears to be essential to clarify the role of Aβ maturation for the progression of Aβ plaque pathology.

Induction of Aβ seeding can be induced in vitro within Aβ producing, wild-type and APP-knockout hippocampal slice cultures27 whereas in vivo seeding is restricted to animal models that overexpress APP and produce increased amounts of Aβ, although Aβ aggregates can persist in a hidden form even in APP-knockout mice.17,28 Thus, to study seeding of Aβ in vivo, Aβ producing mouse models are required.

Here, we studied the pattern of Aβ maturation in four different brain regions of human autopsy cases covering early as well as late affected brain regions throughout the phases of Aβ deposition and supplemented this descriptive analysis by functional seeding and propagation experiments in APP transgenic mice. By inducing Aβ seeding with patient-derived Aβ aggregates differing in the Aβ phase, Aβ load and B-Aβ aggregate maturation stage, we show that Aβ deposition was induced by all lysates used. In this context, the speed of propagation was associated with the amount of Aβ in the brain lysates and the donor Aβ phases whereas maturation was also influenced by the presence of AβN3pE and/or AβpSer8 in the lysates of the donor brains.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Forty-six autopsy cases from university and municipal hospitals in Offenbach, Bonn and Ulm (Germany)6,12,29,30 were analysed in this study (Supplementary Table 1A and B). The autopsies were performed with informed consent of the next in kin. This study was approved by the Ulm University (54/08, 342/14) and the UZ/KU-Leuven ethical committees (S-59295, 64378).

All cases were clinically examined at the time point of hospital admission (∼1–4 weeks before death) by clinicians with different specialties according to standardized protocols. These protocols included the assessment of cognitive function (orientation to place, time and person; specific cognitive or neuropsychiatric tests were not performed) and recorded the patients’ ability to care for themselves and to get dressed, eating habits, bladder and bowel continence, speech patterns, writing and reading ability, short-term and long-term memory and orientation within the hospital setting. These data were used to retrospectively assess the clinical dementia rating scores for 39/46 individuals31 without knowledge of the pathological diagnosis. For seven cases, the available clinical data were not sufficient to obtain a clinical dementia rating score retrospectively.

Neuropathology

From all human brains, the right brain hemisphere was cut fresh and specimens were kept frozen for biochemical analysis. The left hemisphere was fixed in a 4% aqueous solution of formaldehyde or phosphate-buffered formaldehyde for ∼3–4 weeks before cutting. Brains were cut in coronal slices and screened macroscopically. For histopathological analysis and for assessing the amounts of amyloid plaques, NFTs and neuritic plaques, paraffin-embedded tissue including parts of the frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, entorhinal cortex, the hippocampal formation at the level of the lateral geniculate body, basal ganglia, thalamus, amygdala, midbrain, pons, medulla oblongata and cerebellum were examined. Paraffin sections of 5–12 µm thickness from all blocks were stained with haematoxylin and eosin.

Data were excluded when the documentation was not clear or when tissue was not available. Cases were assigned to each group [symptomatic Alzheimer's disease (symAD); pathologically-defined preclinical Alzheimer's disease (p-preAD); non-Alzheimer's disease control (nonAD)] based on records of medical diagnosis and post-mortem neuropathological examinations (for details. see Supplementary Table 1A and Supplementary material). The sample size was determined in analogy to a previous study analysing the maturation of Aβ in the neocortex12 and by the limitations of tissue availability (frozen samples from four brain regions of the same brain).

For neuropathological diagnosis sections were stained with immunohistochemical methods with primary antibodies against abnormal phosphorylated τ protein, Aβ17−24, AβN3pE and AβpSer832 (Supplementary Table 5). Primary antibodies were detected with biotinylated secondary antibodies and visualized with diaminobenzidine-HCl and the avidin-biotin complex (Vector).

The phase of Aβ plaque pathology (Aβ phase),6 Braak NFT stage,33 consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease scores for neuritic plaque density,34 cerebral amyloid angiopathy stage,35 stage of maturation of Aβ plaques (B-Aβ plaque stage)12 and the Aβ, AβN3pE and AβpSer8 loads were determined (for details, please see Supplementary material).

The presence of non-modified Aβ was confirmed in cases listed in Supplementary Table 1B with an antibody (7H3D6) detecting non-truncated Aβ without phosphorylation at Ser8. This antibody does not cross-react with AβN3pE and AβpSer8.32

In the temporal neocortex of Brodmann area 36, the presubicular and the cornu ammonis 1 (CA1)/subiculum region of the hippocampal formation we determined the plaque types stained with antibodies against Aβ, AβN3pE and AβpSer8.

Biochemistry

Biochemical analysis was carried out from 38 cases that were already included in previous studies.12,30 In short, protein extraction for biochemical analysis of Aβ maturation from fresh-frozen frontal neocortex (Brodmann area 6), cingulate gyrus (Brodmann area 24), putamen and the cerebellum from cases listed in Supplementary Table 1A was performed as described in detail in Supplementary material. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) measurements for Aβ40, Aβ42, AβN3pE and AβpSer8 were carried out without fractionation. Western blot analysis was done after separating soluble, dispersible, sodium dodecyl sulphate-soluble and formic acid soluble fractions. To detect even very low amounts of AβN3pE and AβpSer8 the blots were detected with longer exposure times (Supplementary material).

Biochemical stages of Aβ aggregation were determined as previously published and described in detail in the Supplementary material.3,12

Animals

Heterozygous 2-month-old female C57BL/6J-Tg(Thy1-APPK670N; M671L)23 mice (APP23 mice) were used because they are a well-established model for analysing Aβ seeding.17,25 Mice were originally generated by the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research (Basel, Switzerland).36 For this study, we chose heterozygous female mice because they have a well predictable course of Aβ plaque pathology and start to develop the very first neocortical plaques when 5–6 months old.7,37,38 Thus, seeding can be easily identified by the deposition of Aβ plaque material outside the neocortex. Mice were bred by continuous backcrossing of heterozygous males with wild-type females on a C57BL/6 background in a specific pathogen free facility. All mice were housed in individual, type II filter cages with floors covered in wood shavings, with food and water ad libitum (for details see Supplementary material). The experimental procedures were approved by the ethical committee for animal experimentation with project number P125/2016 and carried out according to the Belgian law.

Brain extract preparation for inoculations

Fifty milligrams of fresh-frozen human brain tissue from the occipital cortex (Brodmann area 17) from the cases: symAD 2, p-preAD 2, p-preAD 14, p-preAD 21, nonAD 2 and nonAD 10 were used (Supplementary Table 1B). Tissue was homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) using a micro-pestle (0.1 mg tissue/µl PBS) before being sonicated three times for 5 s. Next, the samples were centrifuged at 3000g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and stored as the total supernatant. Part of the total supernatant (i.e. initial volume for soluble and dispersible fractions) was ultracentrifuged at 121 656g for 30 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was further concentrated 10 times using a 3 kDa Amicon filter (Millipore) before being stored as soluble fraction. The pellet was resuspended in PBS (1/10 of the initial volume), shortly sonicated and stored as dispersible fraction. The neuropathological characterization as well as the quantitative and semi-quantitative biochemical analysis of the occipital cortex samples of these cases was carried out as described for other brain samples under the ‘Neuropathology’ and ‘Biochemistry’ sections.

The seeding activity of the brain tissue was confirmed in an in vitro seeding assay using mCherry-Aβ1−42 expressing human embryonic kidney cell line 293T (HEK293T) cells (Supplementary material).

Stereotactic injection

Sixty-nine female APP23 transgenic mice were used and randomly distributed over 11 groups (n = 6–7 for each group) receiving brain extracts from different cases or PBS as indicated in Table 2. For stereotactic injection, 2-month-old mice were anaesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of Ketamine and Medetomidine. After placing the mice in a stereotactic frame (72-6049, Harvard Apparatus), 1 µl of brain extract was injected in the left hippocampal formation (Bregma: −2.5 mm AP, +2 mm LR, −1.8 mm DV) using a 10-µl syringe with a Hamilton needle. One mouse was injected into the right hippocampal formation (Bregma: −2.5 mm AP, −2 mm LR, −1.8 mm DV). The injection was performed at a speed of 1 µl/min. We used a separate needle and syringe for each treatment group (for more details see Supplementary material). One microlitre of the total fraction of the brain lysates represented 100 µg brain tissue. One microlitre of the soluble and dispersible fraction represented the Aβ content of 1 mg brain tissue due to the 10× concentration.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the cases used for preparing the brain lysates used as seeds with the respective seeding performance in relation to the presence/absence, loads and expansion of induced Aβ, AβN3pE and AβpSer8 deposition in mice

| Induced pathology in the treated mice | Characteristics of lysates | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases and fraction | Antibody | Seeded Aβ speciesa | Total n per group | Average Aβ loadb | Average hAP scorec | Aβ content, ng/µl | Aβ phase | Braak NFT stage | Temp Aβ load | B-Aβ stage | B-Aβ plaque stage | B-Aβ lysate injected |

| Comparison among different fractions of lysates from an Alzheimer’s disease and a p-preAD case | ||||||||||||

| p-preAD2 soluble fraction | Aβ | 50.00 | 6 | 0.037 (0.063) | 13.9 (20.2) | 0.011 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| AβN3PE | 0.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| AβpSer8 | 0.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| p-preAD2 dispersible fraction | Aβ | 50.00 | 6 | 0.021 (0.024) | 27.1 (19.7) | 0.009 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| AβN3PE | 33.33 | 0.001 (0.001) | 8.3 (11.8) | |||||||||

| AβpSer8 | 0.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| p-preAD2 total supernatant fraction | Aβ | 50.00 | 6 | 0.023 (0.035) | 15 (22.4) | 0.007 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| AβN3PE | 0.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| AβpSer8 | 0.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| symAD2 soluble fraction | Aβ | 83.33 | 6 | 0.266 (0.238) | 66.7 (40.4) | 0.017 | 4 | 4 | 10.88 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| AβN3PE | 33.33 | 0.032 (0.064) | 15 (33.5) | |||||||||

| AβpSer8 | 66.67 | 0.043 (0.061) | 46.7 (44.3) | |||||||||

| symAD2 dispersible fraction | Aβ | 100.00 | 6 | 0.882 (0.696) | 69.4 (39.1) | 0.136 | 4 | 4 | 10.88 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| AβN3PE | 83.33 | 0.031 (0.028) | 37.5 (34.4) | |||||||||

| AβpSer8 | 83.33 | 0.003 (0.002) | 18.8 (14.2) | |||||||||

| symAD2 total supernatant fraction | Aβ | 83.33 | 6 | 0.486 (0.611) | 54.4 (45) | 0.039 | 4 | 4 | 10.88 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| AβN3PE | 33.33 | 0.005 (0.009) | 18.1 (28.1) | |||||||||

| AβpSer8 | 50.00 | 0.019 (0.023) | 29.2 (39.4) | |||||||||

| Comparison of the dispersible fraction among lysates from different cases | ||||||||||||

| PBS | Aβ | 14.29 | 7 | 0.001 (0.003) | 1.6 (4.2) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| AβN3PE | 0.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| AβpSer8 | 0.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| nonAD10 | Aβ | 0.00 | 7 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AβN3PE | 0.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| AβpSer8 | 0.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| nonAD2 | Aβ | 33.33 | 6 | 0.016 (0.024) | 9.2 (14.3) | <0.001 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AβN3PE | 16.67 | 0.001 (0.002) | 3.3 (8.2) | |||||||||

| AβpSer8 | 0.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| p-preAD2 | Aβ | 50.00 | 6 | 0.021 (0.024) | 27.1 (19.7) | 0.009 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| AβN3PE | 33.33 | 0.001 (0.001) | 8.3 (11.8) | |||||||||

| AβpSer8 | 0.00 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| p-preAD14 | Aβ | 100.00 | 7 | 0.23 (0.195) | 36.4 (27.9) | 0.031 | 2 | 2 | 1.54 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| AβN3PE | 85.71 | 0.029 (0.029) | 24.2 (22.2) | |||||||||

| AβpSer8 | 71.43 | 0.025 (0.026) | 10.7 (8.6) | |||||||||

| p-preAD21 | Aβ | 100.00 | 6d | 2.767 (1.541) | 91.7 (18.6) | 0.018 | 5 | 2 | 5.53 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| AβN3PE | 83.33 | 0.017 (0.012) | 61.7 (32.6) | |||||||||

| AβpSer8 | 33.33 | 0.001 (0.002) | 15 (20.7) | |||||||||

| symAD2 | Aβ | 100.00 | 6 | 0.882 (0.696) | 69.4 (39.1) | 0.136 | 4 | 4 | 10.88 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| AβN3PE | 83.33 | 0.031 (0.028) | 37.5 (34.4) | |||||||||

| AβpSer8 | 83.33 | 0.003 (0.002) | 18.8 (14.2) | |||||||||

n = number of animals treated for each condition. Values in bold highlight a positive percentage >76%. Note that Case p-preAD21 is exceptional since this case already showed the topographical distribution of Aβ phase 5 whereas AβpSer8 could not be detected within the plaques by immunohistochemistry. We used this case here because it allowed us to extract substantial amounts of Aβ in B-Aβ plaque stage 2. NA = not applicable.

Values presented as % (positive n/total n).

Values presented as % (±SD).

Values presented as mean (±SD).

One mouse from this group received the injection of dispersible fraction from Case p-preAD21 in the right hippocampus.

Mouse neuropathology

At 6 months of age, the mice were sacrificed by decapitation under anaesthesia with Ketamine and Medetomidine. The brains were removed and further processed. Brain tissue of six mice was snap-frozen and stored at −80°C. From 63 animals, the brains were kept fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for ∼4 days and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections of the mouse brain samples were immunostained using the BOND-MAX automated staining system (Leica) with polyclonal antibodies raised against Aβ1−4039 and AβN3pE (Supplementary Table 4). The BOND-MAX automated staining system performs a peroxidase blocking step, incubation with primary antibody, secondary antibody, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine and a haematoxylin counterstaining via an automated protocol. Staining for AβpSer8 was performed with a mouse monoclonal antibody (1E4E11) (Supplementary Table 5)32 according to a staining protocol for mouse tissue with murine antibodies.40 Briefly, the mouse primary antibodies and biotinylated anti-mouse IgG fragment antigen-binding (Fab)-fragments (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were incubated together for 20 min (2 µg Fab-fragment for 1 µg primary antibody) at room temperature. Thereafter, normal mouse serum was added to capture unbound Fab-fragments. After epitope retrieval and subsequent peroxidase and protein blocking, the Fab-fragment linked antibodies were incubated overnight with the sections, followed by detection with horseradish peroxidase-coupled streptavidin (1/1000, 016-030-084, Jackson ImmunoResearch) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. Stained sections were counterstained with haematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted in Leica CV mounting medium.

Morphometric quantitative analysis of seeded amyloid-β

For Aβ-plaque load measurements, digital images of the hippocampal region from the injected and non-injected, plaque-free hemisphere of each mouse were taken with a Leica DM2000 LED microscope connected to a Leica DFC 700T camera at ×5 magnification using the LAS V4.8 software. The images covered a total area of 4.65 mm² (reference area), the Aβ-positive area was measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA), and the Aβ-load was calculated as the percentage of the Aβ-positive area in the given reference area. The Aβ-plaque area was measured by setting a threshold based on the brightness parameter for every individual case, in a manner that the plaque area was covered. To correct for background signals of the transgenic expression of APP, we subtracted the area that was detected in the non-injected hemisphere, when applying the same threshold values as for the injected hemisphere. For plaque load measurements, AβN3pE and AβpSer8 positive plaques in the injected hemisphere were manually delineated with a cursor.41

To determine the spatial expansion of seeded Aβ plaques, the anterior–posterior extent of Aβ pathology was analysed for five to seven mice per group. The animals were selected for this analysis based on two inclusion criteria: (i) induction of seeding; and (ii) availability of paraffin-embedded tissue (frozen brains were not used). Spreading was analysed by scoring 12 coronal sections, covering the entire hippocampal region (−0.655 mm from Bregma until −3.78 mm from Bregma, see Supplementary Table 4 for details about the investigated levels). Scoring was performed based on absence or presence of Aβ pathology, separately in each section as visualized by the polyclonal anti-Aβ1−42 antibody.39 The hippocampal anterior–posterior expansion score (hAP score) was calculated as a percentage of the sum of the positive sections from these 12 sections. A hAP score was also determined for anti-AβN3pE and anti-AβpSer8-stained sections.

Statistical analysis

Assessment and quantification of all neuropathological variables from brain samples of human cases and mice were performed by two blinded observers independently. Statistical analysis was calculated with R (v.3.6.3) and SPSS 27 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc method was carried out when comparing multiple groups. Friedman’s test with Dunn’s post hoc method and Bonferroni correction for multiple tests was carried out when comparing among Aβ, AβN3pE and AβpSer8 pathologies, within human cases and mice pair-wise, the distribution of multiple groups. To compare Aβ quantification by Aβ loads and ELISA measurements a Spearman correlation analysis was carried out. The association of these quantitative measures with positive/negative results determined by western blotting was tested with the Mann–Whitney U-test. Spearman correlation (two-tailed) was used for comparison between seed characteristics and seeding effects in mice. Linear regression controlled for age and sex was used to determine the association of the increasing Aβ phase with the respective Aβ, AβN3pE and AβpSer8 loads in the human brain samples. In the mouse samples we used for this purpose, an ANOVA test since all mice were female and the same age.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ulm University Ethics Committee (Ulm/Germany; Decision No. 54/08, 342/14) and by the UZ-Leuven ethical committee (Leuven/Belgium; Decision No. S-59295, S-64378). In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, informed consent for autopsy and scientific use of autopsy tissue with clinical information was granted. Animal experiments were approved by the KU-Leuven ethical committee for animal experiments (Leuven/Belgium; Decision No. P125/2016). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data availability

All cases are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 with the main parameters obtained throughout this study, with the main clinical diagnosis, age and sex. Due to legislation and privacy protection any medical reports and files of the cases included in this study cannot be made available. Mean and standard deviations from mouse experiments are provided in Table 2. Data describing statistical results are presented in the respective figure legends, in the ‘Results’ section and in Supplementary Table 3. More detailed data will be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Propagation and maturation of Aβ plaque pathology in the human brain

To study maturation of Aβ plaques throughout the different phases of Aβ plaque propagation, 45 autopsy brains covering all Aβ phases were investigated (Supplementary Table 1A). We determined the composition of Aβ plaques in four brain regions that become subsequently affected by Aβ pathology: the neocortex in Aβ phase 1, cingulate gyrus in phase 2, basal ganglia in phase 3 and the cerebellum in phase 5 (Supplementary Table 1).6 In all four regions, an antibody raised against Aβ17−24 detected all Aβ plaques (Table 1). A subset of these plaques exhibited AβN3pE-positive material in some non-demented and all demented cases. AβpSer8 was mainly restricted to demented cases, i.e. symAD, and only observed in cases that already exhibited AβN3pE in the respective regions (Table 1). Aβ deposits lacking anti-AβN3pE and anti-AβpSer8-positivity were considered to mainly contain non-modified Aβ. This was supported by reactivity of Aβ plaques with an antibody not cross-reacting with N-terminal truncated and phosphorylated Aβ species32 in the cases listed in Supplementary Table 1B. The cerebellum exhibited AβpSer8 in only one single case. None of our cases exhibited modified forms of Aβ in the absence of Aβ detectable with antibodies raised against Aβ17−24. The Aβ loads describing the area in a given region covered by Aβ plaques in all investigated brain regions were higher for presumably non-modified Aβ, than for AβN3pE loads, which were higher than the respective AβpSer8 loads (Fig. 1). Given the Aβ phase-related prevalence of Aβ plaques in a given brain region, the temporal neocortex showed Aβ plaques most frequently, followed by the cingulate gyrus, then the basal ganglia and finally the cerebellum (Fig. 1, Table 1). The histopathological sequence of Aβ aggregate maturation from presumably non-modified Aβ to AβN3pE and finally to AβpSer8 in all investigated brain regions was confirmed by western blotting and quantitative ELISA analysis of brain homogenates of the respective brain regions (Supplementary Fig. 1). The methods correlated well for detection and quantification of Aβ, whereas AβN3pE and AβpSer8 were less abundant in ELISA measurements especially in the basal ganglia and the cerebellum.

Table 1.

Prevalence of plaques exhibiting Aβ (detected with antibodies against non-modified Aβ), AβN3pE and AβpSer8 in the human brain

| Brain region | Antibody | Aβ phase 0 (n = 9) | Aβ phase 1 (n = 6) | Aβ phase 2 (n = 8) | Aβ phase 3 (n = 7) | Aβ phase 4 (n = 3) | Aβ phase 5 (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal neocortex | Aβ | 0.00 | 83.33 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| AβN3PE | 0.00 | 66.67 | 87.50 | 87.50 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

| AβpSer8 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 25.00 | 57.10 | 100.00 | 90.90 | |

| Cingulate gyrus | Aβ | 0.00 | 0.00 | 62.50 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| AβN3PE | 0.00 | 0.00 | 50.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

| AβpSer8 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.50 | 57.10 | 100.00 | 54.50 | |

| Putamen | Aβ | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| AβN3PE | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 87.50 | 66.67 | 100.00 | |

| AβpSer8 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 33.33 | 36.40 | |

| Cerebellar cortex | Aβ | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 90.90 |

| AβN3PE | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 90.90 | |

| AβpSer8 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.10 |

Percentages of cases in each Aβ phase exhibiting the respectively stained plaques in the human brain in the temporal neocortex (Brodmann area 36), cingulate gyrus (Brodmann area 24), putamen and cerebellar cortex are provided (n = 44 cases). A single Aβ phase 1 case exhibited plaques only in the occipital neocortex but not in the temporal cortex. Few Aβ phase 2 cases showed plaques in the entorhinal cortex/hippocampus while none were seen in the cingulate gyrus. One Aβ phase 5 case with Aβ plaques in the pons had no cerebellar plaques. Values in bold highlight positive percentage >76%.

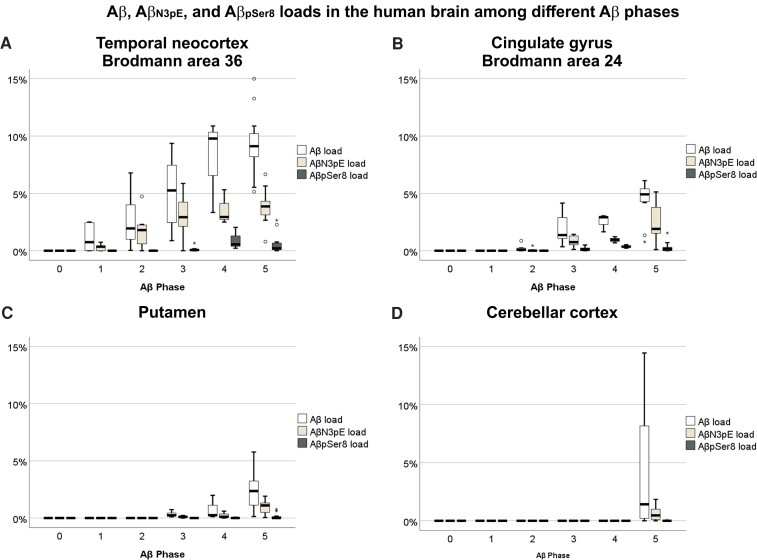

Figure 1.

Aβ, AβN3pE and AβpSer8 loads in the human brain among different Aβ phases. (A–D) Box plot diagrams comparing Aβ loads in the human brain among Aβ phases 0–5. Aβ, AβN3pE and AβpSer8 loads were obtained immunohistochemically in the temporal neocortex (Brodmann area 36) (A), the cingulate gyrus (Brodmann area 24) (B), the putamen (C) and the cerebellar cortex (D) (n = 44). All Aβ, AβN3pE and AβpSer8 loads increased with advancing Aβ phase as dependent variable (linear regression analysis with age and sex as additional covariates: P < 0.05; β: 0.289–0.731), except for the cerebellar AβpSer8 load (linear regression analysis with age and sex as additional covariates: P = 0.233). Presumably non-modified Aβ prevailed over AβN3pE and AβpSer8 in the temporal cortex, cingulate gyrus and putamen [Friedman test corrected for multiple testing (two-sided): P < 0.05]. AβN3pE was here more abundant than AβpSer8 [Friedman test corrected for multiple testing (two-sided): P < 0.05]. In the cerebellar cortex, which was only involved in Aβ pathology in 10 out of 11 Aβ phase 5 cases, presumably non-modified Aβ was more abundant than AβpSer8 [Friedman test corrected for multiple testing (two-sided): P < 0.001] and a trend was observed for more abundant AβN3pE than AβpSer8 [Friedman test corrected for multiple testing (two-sided): P = 0.059; non-corrected P = 0.019]. Box elements: centre line = median; box limits = upper and lower quartiles; whiskers = 1.5× interquartile range; dots/stars = outliers.

The accumulation of modified Aβ species varied among different plaque types. Fleecy amyloid, a very early type of diffuse plaques occurring in the entorhinal cortex and the subiculum/CA1 region exhibited no AβN3pE and no AβpSer8 (Supplementary Fig. 2A–C). Presubicular lake-like and subpial band-like amyloid were Aβ- and AβN3pE-positive whereas AβpSer8 was seen there only in single cases. The highest percentage of diffuse plaques was stained with anti-Aβ antibodies, followed by anti-AβN3pE. AβpSer8 was only visible in a minority of diffuse plaques (Supplementary Fig. 2). Cored plaques often exhibited all three Aβ forms and represented the main plaque type exhibiting AβpSer8 (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2).

Induction of Aβ seeding and maturation in APP23 mice by human brain-derived seeds from soluble and dispersible fractions of Aβ-containing brains

To analyse the impact of the seed (derived from different phases and maturation stages) on inducing Aβ deposition and maturation in vivo, we determined first which fraction of the brain lysates (soluble or insoluble) was best suited for comparing seeds derived from different brains. To do so, we compared the seeding effects in mice injected with soluble, dispersible (insoluble) and total supernatant (soluble + dispersible) fractions (Fig. 2). To avoid contamination by p-τ pathology, we chose the Brodmann area 17 from cases with a Braak NFT stage lower than V, lacking local p-τ pathology in this region. For this purpose, we used brain lysate fractions from one Aβ phase 4 symAD case (Case symAD2; Supplementary Fig. 3L–N) and one Aβ phase 1 p-preAD case (Case p-preAD2) with single plaques in the occipital cortex (Supplementary Fig. 3C–E). The soluble, dispersible and total supernatant fractions were prepared as indicated in Fig. 2A. The proteins of the soluble and dispersible fraction were concentrated in a standardized manner to gain sufficient yield and to avoid an over-proportional enrichment of Aβ (see Supplementary material for details). The lysates from Case symAD2 contained ∼0.017 to 0.136 ng/µl Aβ (Table 2) and detectable amounts of AβN3pE whereas AβpSer8 could not be seen in the fractions. The fractions from Case p-preAD2 did not contain detectable amounts of Aβ (≤0.011 ng/µl) despite the presence of single Aβ plaques in the occipital cortex observed immunohistochemically (Supplementary Fig. 3). These results were confirmed by ELISA (Supplementary Fig. 3), although due to the lack of sensitivity of the antibodies and the low levels, neither AβN3pE nor AβpSer8 was detected. To determine the seeding activity of these extracts, we used a biosensor cell model expressing mCherry-Aβ1−42 stably in HEK293T cells,42 and we measured mCherry-intensive spots that indicated cellular seeding. We used the sarkosyl-insoluble fractions of the selected cases in this assay. Unlike the wells that were treated with early p-preAD case (p-preAD2) extract that barely showed any positive signal, those with symAD case (symAD2) extracts exhibited Aβ seeding activity with an half-maximum effective concentration of 0.6083 ng/ml total Aβ1−42 (Supplementary Fig. 3T–U).

Figure 2.

Propagation and maturation of Aβ pathology in the mouse brain after seed injection. Schematic representation of the experimental design. (A) Production of nonAD, p-preAD and Alzheimer’s disease brain homogenates for inoculation in the mouse brain. For this purpose, a slightly modified centrifugation protocol according to Meyer-Luehmann et al.17 was used to generate the ‘total supernatant’ fractions, which was in a second step divided into soluble and insoluble but dispersible material. In short, after homogenization of occipital cortex (Brodmann area 17) samples and addition of a proteinase inhibitor cocktail, the lysates were centrifuged at 3000g. The pellet was discarded. The supernatant was considered as the total supernatant fraction. Part of the total supernatant fraction were ultracentrifuged and concentrated 10 times to separate the soluble (supernatant) and dispersible (resuspended pellet) fractions (Supplementary material). (B) Induction of Aβ seeding in the mouse left mouse hippocampal formation by brain homogenates of nonAD, p-preAD and symAD cases by soluble, dispersible and total supernatant fractions. To carry out this experiment, 2-month-old APP23 mice received injections of soluble, dispersible or total supernatant fractions from human brain homogenates from one sympAD and one p-preAD case. Likewise, additional mice received the dispersible fraction of two controls or two additional p-preAD cases.

Next, the soluble, dispersible, and total supernatant fractions of the human brain lysates were injected into the left hippocampus of 2-month-old APP23 mice (n = 6 mice per group) (Fig. 2B). At this age, there were no Aβ plaques present in the hippocampus.7,36 To analyse the seeding effect before intrinsic Aβ deposition takes place in APP23 mice, we euthanized these animals at 6 months of age38 and studied the seeding effect immunohistochemically with antibodies raised against (i) Aβ1−40 lacking post-translational modifications and C terminus specificity [confirmed with the 7H3D6 antibody not cross-reacting with truncated or phosphorylated Aβ32 (Supplementary Fig. 4)]; (ii) AβN3pE; and (iii) AβpSer8.

Nine brains from 12 mice receiving the dispersible fraction of brain lysates of the previously mentioned p-preAD and symAD cases exhibited seeded Aβ plaques (Table 2). A seeding effect was also observed in 16/24 of brains from animals receiving the total supernatant fraction and the soluble fraction, respectively (Table 2). All fractions from Case symAD2 induced Aβ, AβN3pE and AβpSer8 deposition to a certain degree. When focusing only on presumably non-modified Aβ, seeding was found in all mice receiving the dispersible fraction of symAD occipital cortex (Table 2). Both the soluble and the total supernatant fraction of this case induced Aβ seeding in 5/6 of the respectively treated mice. When the dispersible fraction of Aβ phase 1 Case p-preAD2 was used to induce seeding, Aβ and AβN3pE together were observed in two out of six mice (33%), whereas Aβ deposits lacking AβN3pE and AβpSer8 were seen in three out of six (50%) of the injected animals. Total supernatant and soluble fractions of Case p-preAD2 induced a seeding effect less frequently than the dispersible fraction (Table 2A).

The statistical comparison of the induction of seeding by the soluble, dispersible and total supernatant fractions revealed no significant differences among the fractions for the presence/absence of a seeding effect, the induced Aβ loads and the expansion throughout the hippocampus as measured with the hAP score (Supplementary Table 3A). Since the dispersible fraction induced seeding and maturation of Aβ more regularly than the soluble or total supernatant fraction, we continued with the dispersible fraction. We used it to compare the impact of seeds from brains with different levels of Aβ pathology, ranging from Aβ phase 1 to Aβ phase 5 and covering different biochemical stages of Aβ aggregate maturation on Aβ propagation and maturation.

Propagation- and maturation-relevant aspects of Aβ seeds depend on the ‘donor’s’ Aβ phase and maturation stage

To clarify whether the presence or absence of AβN3pE and AβpSer8 plays a role in the capacity of brain-derived Aβ to induce Aβ seeding, propagation and maturation we first produced dispersible fractions of brain homogenates from four human brains (Fig. 2A and B). We chose one Aβ phase 4 Alzheimer’s disease case (Case symAD2), one Aβ phase 2 p-preAD case (Case p-preAD14) with plaques exhibiting AβN3pE and AβpSer8, an Aβ phase 5 p-preAD case (Case p-preAD21) with plaques lacking AβpSer8 and a p-preAD case (Case p-preAD2) in Aβ phase 1 with single plaques containing presumably non-modified Aβ and AβN3pE in the occipital cortex (Table 2B, Supplementary Fig. 3C and D). Biochemically, the amount of non-modified Aβ in the extracts was quantified by comparing the intensity of the 4 kDa bands from the extracts with standard samples containing different amounts of synthetic Aβ1−40 peptide.41 The concentrations of presumably non-modified Aβ in the dispersible fractions from Cases p-preAD14, p-preAD21 and symAD2 were estimated to range from 0.018 to 0.136 ng/µl (Supplementary Fig. 3R). These lysates contained also detectable amounts of AβN3pE. Aβ was nearly not detectable in lysates from Case p-preAD2, nonAD10 or nonAD2 (≤0.009 ng/µl; Table 2B, Supplementary Fig. 3O–R). Lysates of control cases without Aβ plaques (Cases nonAD10 and nonAD2) were used as negative controls (Table 2, for detailed histological and biochemical characterization, and the quantification of the presumably non-modified Aβ, see Supplementary Fig. 3O–R) as well as PBS (pH 7.6). The presence of non-modified Aβ species was confirmed using an antibody detecting non-truncated Aβ lacking phosphorylation of Aβ at Ser8 (Supplementary Fig. 4). The western blot-based results were confirmed by ELISA showing similar patterns of total Aβ1−40 and Aβ1−42 (Supplementary Fig. 3). In the biosensor cell model (mCherry-Aβ1−42 HEK293T cells), both p-preAD cases (p-preAD14 and p-preAD21) exhibited Aβ seeding activity while both nonAD cases (nonAD10 and nonAD2) showed no induction of seeding (Supplementary Fig. 3T–U).

In mice, the highest Aβ loads and hAP scores were induced with lysates from Case p-preAD21, followed by symAD2 and then the other p-preAD cases. In single mice, we could also observe minimal Aβ deposition after treatment with PBS and lysates from Case nonAD2. Since APP23 mice can develop single Aβ plaques ∼6 months spontaneously, we would consider the minimal Aβ lesions in PBS and nonAD lysate-injected mice as part of the spontaneous Aβ deposition, maybe triggered by the minimal tissue damage caused by the injection. A similar seeding in control treated animals has also been reported by others.17 Two-tailed Spearman correlation analysis revealed that the Aβ phase of the donor brain was best associated with the induced Aβ loads and hAP propagation scores in the mice (Aβ load: r = 0.842; P < 0.001; hAP score: r = 0.854, P < 0.001; Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 3B). The temporal cortex Aβ load, the Aβ42 content in the lysates as measured by ELISA and the B-Aβ stage/B-Aβ plaque stage of the donor also correlated with the induced Aβ loads and hAP scores but less well than the Aβ phase (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 3B). Thus, the speed of Aβ propagation as indicated by the hAP score 4 months after seeding induction showed the strongest correlation with the donor’s Aβ phase and Aβ load, whereas maturation was less strongly associated.

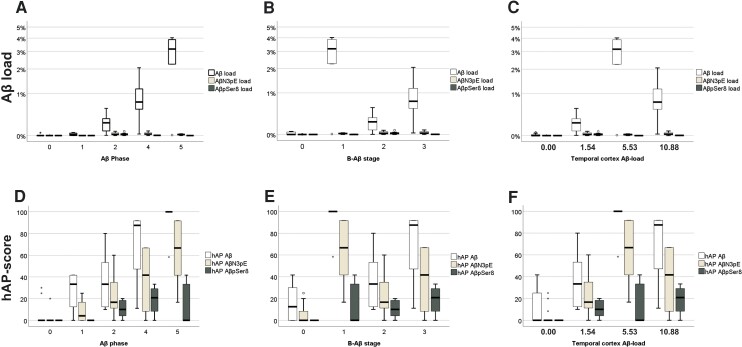

Figure 3.

Relationship between ‘donor’ Aβ pathology and propagation and maturation in the ‘host’ brain. Box plot diagrams of the induced Aβ loads (A–C) and hAP scores (D–F) with the Aβ phases (A and D), B-Aβ stages (B and E) and temporal cortex Aβ loads (C and F), of the respective cases used for the generation of the brain lysates. ANOVA indicated an increasing tendency of the induced hAP scores for all three Aβ species with increasing Aβ phase of the injected ‘donor’ brains (ANOVA: P ≤ 0.023, n = 38 mice) and Aβ load (ANOVA: P < 0.001, n = 38 mice). AβN3pE and AβpSer8 loads did not increase continuously with Aβ phase although ANOVA indicated differences among the groups (ANOVA: P ≤ 0.005, n = 38 mice). Increasing B-Aβ stages and temporal cortex Aβ loads of the ‘donor’ brains did not go along with a continuous increase of the induced Aβ and AβN3pE loads and hAP scores and the AβpSer8 load, whereas the AβpSer8 hAP score continuously rose. Note that the Aβ loads and hAP scores for Aβ detectable with antibodies raised against non-modified forms of Aβ were higher than those for AβN3pE and AβpSer8 in mice with Aβ pathology [Friedman test corrected for multiple testing (two-sided): P < 0.01, n = 24 mice; see also Supplementary Table 2B]. Box elements: centre line = median; box limits = upper and lower quartiles; whiskers = 1.5× interquartile range; dots/stars = outliers.

On the contrary, the induced AβN3pE and AβpSer8 loads and the related hAP scores correlated better with the B-Aβ plaque stage/B-Aβ stage of the donor brains (Supplementary Table 3B). The finding that brain lysates with an advanced B-Aβ stage induce higher hAP scores for modified forms of Aβ than lysates with less advanced B-Aβ stages indicates that the propagation of mature Aβ aggregates is accelerated by the presence of modified forms of Aβ in the seeds, i.e. the respective B-Aβ stage.

Aβ species lacking detectable amounts of AβN3pE and AβpSer8 propagate faster than AβN3pE and AβpSer8

Next, we wanted to know which forms of Aβ expand to what extent after seeding was induced. Presumably non-modified Aβ deposits detected with antibodies raised against non-modified Aβ showed higher hAP scores than those detected with anti-AβN3pE or anti-AβpSer8 (Supplementary Table 3C), indicating a more widespread expansion of presumably non-modified Aβ whereas only few AβN3pE or AβpSer8-positive plaques were found (Figs 3D–F and 4). In none of the mice and regardless of the fractions/lysates that were injected, AβN3pE or AβpSer8 was found in the absence of presumably non-modified Aβ. Likewise, AβN3pE was always present when AβpSer8 was detected (Figs 3 and 4 and Table 3). Since seeding and expansion of Aβ deposition were investigated in a 4-month interval after injecting the seeds, the more widespread distribution of presumably non-modified forms of Aβ represents a higher propagation speed of this Aβ species compared to AβN3pE, which propagates still faster than AβpSer8.

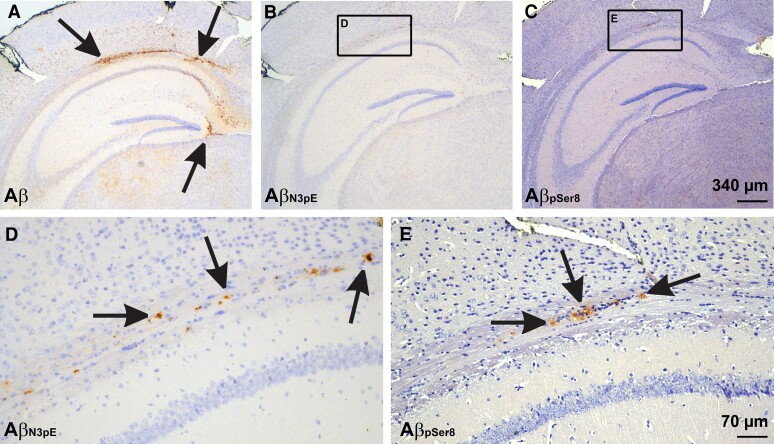

Figure 4.

Seeded Aβ in mice receiving the dispersible fraction from p-preAD case 14. (A) Seeded plaques stained with a non-C terminus-specific polyclonal antibody raised against Aβ1−40. The Aβ deposits were easily detectable even at low magnification level. (B and C) At low magnification level AβN3pE- and AβpSer8-positive plaques were less widespread and less visible. Calibration bar in C is valid for A–C. (D and E) At high power magnification both AβN3pE and AβpSer8 was seen at the white matter next to the hippocampal sector CA1. Note that AβN3pE-positive material was more widely distributed compared to AβpSer8. Calibration bar in E is valid for D and E.

Table 3.

Percentages of mice with seeded Aβ lesions exhibiting all three types of Aβ

| Aβ | Aβ + AβN3pE | Aβ + AβN3pE + AβpSer8 | AβN3pE + AβpSer8 | AβpSer8 | AβN3pE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soluble fraction | 50% (n = 4) | 25% (n = 2) | 25% (n = 2) | 0% (n = 0) | 0% (n = 0) | 0% (n = 0) |

| Dispersible fraction | 20.8% (n = 5) | 29.2% (n = 7) | 50% (n = 12) | 0% (n = 0) | 0% (n = 0) | 0% (n = 0) |

| Total fraction | 62.5% (n = 5) | 12.5% (n = 1) | 25% (n = 2) | 0% (n = 0) | 0% (n = 0) | 0% (n = 0) |

Values with a positive percentage between 50 and 74% are highlighted in bold. The table indicates the percentages of mice with seeded Aβ lesions exhibiting all three types of Aβ (Aβ, AβN3pE and AβpSer8), Aβ lesions lacking AβN3pE and AβpSer8, and Aβ lesions showing only Aβ and AβN3pE but no AβpSer8. We did not observe AβN3pE and AβpSer8 in the absence of non-modified Aβ and AβpSer8 without coexisting Aβ and AβN3pE. It is interesting to note that injection of the dispersible fraction induced more frequently the induction of all types of Aβ species whereas injection of the soluble and total fraction led mainly to the induction Aβ lacking AβN3pE and AβpSer8.

Discussion

The results indicate (i) that propagation of Aβ pathology is led by Aβ species lacking detectable amounts of post-translationally modified AβN3pE and AβpSer8 in the human p-preAD and symAD brain as well as in mouse brains that were triggered to develop Aβ deposits by seeds from symAD or p-preAD brains; (ii) that biochemical maturation in the human brain is associated with the maturation of the plaque morphology from diffuse plaque types to mature cored ones; (iii) that maturation of Aβ aggregates principally takes place regardless of the origin (fraction, symAD or p-preAD brain) or biochemical composition of the brain-derived seeds but is accelerated by the presence of AβN3pE and AβpSer8 in the seeds; and (iv) that the level of Aβ pathology in a given donor brain indicated by the Aβ phase or the Aβ plaque load explains the seed-induced Aβ extent of propagation and plaque load better than the B-Aβ stage of Aβ in the donor brain lysates. With these results, we extend the current knowledge about Aβ pathology propagation and maturation by highlighting the importance of presumably non-modified Aβ species for the induction of Aβ seeding and its propagation while Aβ maturation is accelerated by the presence of the post-translationally modified forms of Aβ, i.e. AβN3pE and/or AβpSer8. This is in line with the occurrence of AβN3pE and AβpSer8 in more mature plaque types, especially cored plaques in Alzheimer’s disease cases.

Our conclusion that presumably non-modified Aβ is the leading force for initiation and propagation of Aβ pathology in the brain is based on two independent findings: (i) the detection of Aβ deposits lacking AβN3pE and AβpSer8 that occur in a given brain region before more mature forms of Aβ aggregates develop in each of the investigated brain regions of the human brain in symAD and p-preAD cases; and (ii) the fastest propagation of Aβ lacking anti-AβN3pE- and anti-AβpSer8-positive material in APP23 mice after induction of seeding. These findings are in line with neuropathological findings in Alzheimer’s disease12,43 as indicated here by the lack of AβN3pE and AβpSer8 in fleecy amyloid, which is an early plaque type preceding diffuse plaques,44 and in Aβ deposits associated with normal pressure hydrocephalus.45 They also fit with the increased propensity of AβN3pE and AβpSer8 to form more stable and less soluble Aβ aggregates than non-modified Aβ.46–48 Quantitative ELISA measurements of the Aβ concentration in the Alzheimer’s disease brain are in line and indicate that the concentration of AβN3pE is more than 20× lower than that of Aβ42. AβpSer8 is even less prominent than AβN3pE and can only be detected by western blotting after long exposure of the blots. Moreover, we found that the Aβ composition of the lysates injected as seeds into the mice had only influence on the speed of accumulation of AβN3pE and AβpSer8 in the seeded Aβ deposits but not on the deposition and propagation of other, presumably non-modified forms of Aβ. That brain lysates from early and late stage Aβ aggregates of different maturation stages induce seeding of modified Aβ species is further supported by our finding that even soluble Aβ from p-preAD cases was capable of inducing Aβ seeding including that of AβpSer8, although soluble AβpSer8 was not detected in the soluble fraction.12

On the other hand, the accumulation of anti-AβN3pE and anti-AβpSer8-positive material is essential for the maturation of Aβ, which is linked with the development of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease cases compared to non-demented individuals12 and to p-τ pathology.49 In this context, the presence of anti-AβN3pE and anti-AβpSer8-positive material in seeds accelerated the accumulation of the post-translationally modified forms of Aβ as indicated by the respective AβN3pE- and AβpSer8-loads.

As expected from earlier studies using mouse brain-derived Aβ, the concentration of Aβ in the seeds determined the severity of the seeding effect.50,25 In our study, the concentration of Aβ in the brain measured by ELISA corresponds to the Aβ loads and the phases of Aβ deposition in the brains of the individuals used to produce the lysates for inducing seeding. Interestingly, even brain lysates from an Aβ phase 1 p-preAD case induced a mild seeding effect in 50% of the mice receiving the lysates whereas plaque-free lysates from younger individuals did not induce significant seeding. Since all lysates were prepared in an identical procedure, their seeding activity is related to the concentration of the relevant Aβ forms in the respective samples that varied among the cases. This was confirmed in our in vitro seeding assay and extends earlier reports about seeding with Alzheimer’s disease and Aβ containing brain lysates from non-demented individuals51 by clearly indicating that p-preAD cases already have a seeding capacity, i.e. the capacity to kick-off the process of Alzheimer’s disease-related β-amyloidosis. By doing so, we deliver another argument supporting the hypothesis that Aβ deposition in the human brain represents one pathobiological process that begins with the very first Aβ plaques in the neocortex of non-demented individuals and ends in symAD. Other arguments are the hierarchical pattern of Aβ deposition and propagation in the human brain6 that is reflected by the progression of Aβ PET tracer retention with increasing Aβ phase over time52–54 and by the sequence of Aβ deposition in the brains of APP transgenic mice.7 Altogether, these arguments strongly support the idea that Aβ plaque deposition, whenever present in the human brain, represents Alzheimer’s disease-related β-amyloidosis even when the concentration of Aβ was not significantly increased as in Aβ phase 1.

Moreover, we found that the speed of propagation of seeded Aβ correlates with Aβ phase, Aβ plaque load and Aβ concentration of the donor brain and the progression speed of maturation with the B-Aβ stage of Aβ aggregate maturation. This finding indicates that these two aspects of Aβ pathology, propagation and maturation, both influence the speed of disease progression. Thus, biomarkers for modified forms of Aβ may help to provide a better prognosis for non-demented individuals with positive amyloid biomarkers because they would add information about a second aspect, i.e. the status of Aβ maturation in the brain.

This study has limitations that need to be mentioned: (i) the number of human autopsy cases used for determining the propagation patterns of Aβ aggregates in the human brain is not very high (n = 45); (ii) the number of cases used for the preparation of brain lysates for the induction of seeding in mice is low (n = 6); (iii) the antibodies raised against non-modified Aβ, AβN3pE and AβpSer8 may vary slightly in their affinity for the respective Aβ variants; and (iv) the seeding effect in the mice can only be measured by morphological methods since a biochemical distinction between injected human Aβ and the transgenically produced human Aβ in APP23 mice is not possible.17 Regarding these limitations, we wish to clarify that the number of human cases investigated here is in the range of similar studies and sufficient from a statistical point of view.17,55,56 Moreover, the cases have been investigated immunohistochemically and biochemically to confirm the results obtained with one method by a second one. The animal experiments confirm on top of it the finding of a pivotal role of presumably non-modified Aβ in Aβ propagation. Statistical analysis confirmed the validity of our findings. The sensitivity of the anti-Aβ17−24, anti-AβN3pE and anti-AβpSer8 antibodies range between 5 and 25 ng/ml but was optimized by the respective antibody concentrations used for staining (Supplementary Table 5). ELISAs can provide high quality quantitative data; however, the amount of AβN3pE and especially AβpSer8 in our extracts was close to the detection threshold with a high signal to noise ratio (Supplementary Fig. 1C). Accordingly, these ELISA results could only complement the western blots and the immunohistochemical results. Moreover, other authors published similar results regarding the subsequent staining with the antibodies against differently modified forms of Aβ.43,45,49,57 In addition, we used a biosensor cell model to determine Aβ seeding activity of extracts from cases of different Aβ phases in vitro. By doing so, we minimized the impact of the limitations in this study as much as possible.

Given the impact of both, Aβ pathology propagation and maturation, for the progression of Aβ pathology from p-preAD to symAD, there are several suggestions for optimizing Aβ targeting treatment strategies. Currently, active and passive vaccination strategies mainly target distinct forms of Aβ or its aggregates, such as pyroglutamate modified AβN3pE (donanemab26) or soluble oligomeric and insoluble fibrillar Aβ aggregates (aducanumab58). Accordingly, other forms are not targeted. Given our finding that different forms of Aβ aggregates may be able to induce/influence seeding, propagation and/or maturation of Aβ, targeting only one species may be not enough to stop the complex process of Aβ pathology in the brain. However, an option could be focusing on blocking Aβ maturation rather than stopping its propagation, e.g. by targeting Aβ species that are restricted to mature Aβ aggregates. For example, donanemab, an antibody targeting AβN3pE, could be such a maturation blocker.26 A combination of a potential propagation stopper and a maturation blocker could offer synergy effects on counteracting Aβ pathology by interfering, for example, with soluble, diffusible aggregates58 and modified AβN3pE26 at the same time. However, this would mean that propagation of Aβ pathology determined by amyloid PET or pan-Aβ biomarkers would probably not be optimally suited to monitor the success of such a treatment rather than using additional AβN3pE- and/or AβpSer8-specific biomarkers and the clinical outcome. It will also be important to keep in mind that residual Aβ aggregates that escaped, for example, peripherally administered antibodies can still accelerate propagation and/or maturation of Aβ aggregates to a certain extent as shown here by the seeding effect of an Aβ phase 1 p-preAD case. Thus, a potentially general problem of all passive immunization strategies is the survival of seeds that can continue or restart the process of Aβ propagation and maturation. Active vaccination strategies targeting multiple forms of Aβ started in the preclinical phase could be an alternative for future Alzheimer’s disease treatment as well as combination therapies with secretase inhibitors. Thus, re-evaluation of clinical trials using passive and active vaccination against Aβ considering the aspects of Aβ maturation and propagation separately could help to understand why vaccination strategies did not work as good as primarily expected and whether polyvaccination against multiple forms of Aβ could be an option for future trials. In doing so, our findings on the different Aβ forms involved in Aβ propagation provide novel insights for identifying critical aspects in targeting Aβ sufficiently by showing potential ‘escape routes’ for Aβ to allow a re-entering into the vicious cycle of Aβ aggregation, propagation and maturation (Fig. 5).

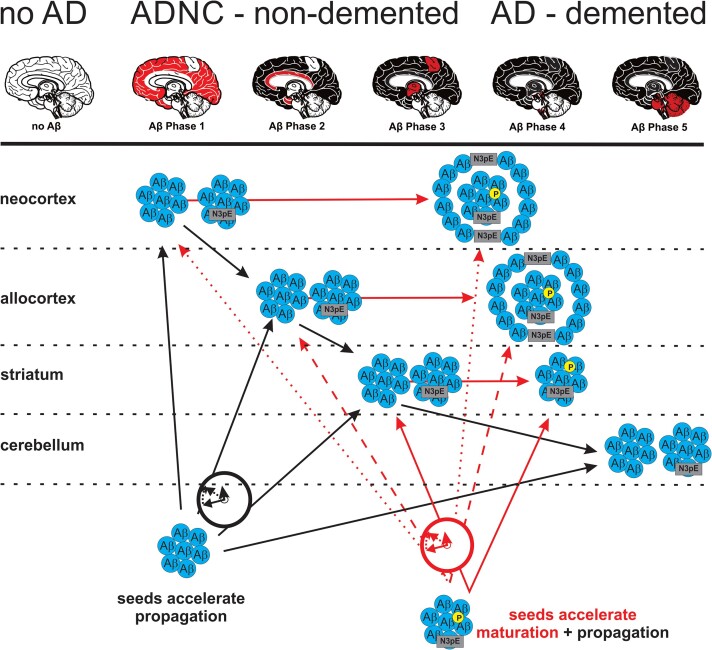

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of Aβ protein deposition, propagation, maturation and its acceleration by seeds. Although Aβ propagation and maturation correlate with one another30 acceleration of these two aspects in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease is modified in a differential manner: propagation of Aβ deposition is accelerated by any kind of Aβ seeds whereas maturation increase depends on the presence of AβN3pE and AβpSer8 in the seeds in a biochemically detectable concentration. Note that AβpSer8-positive plaques are mainly cored plaques.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Irina Kosterin for technical support and Dr A. Piechotta for supporting the production of the J8 anti-AβN3pE antibody.

Abbreviations

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- AβN3pE

N-terminally truncated and pyroglutamate modified Aβ

- AβpSer8

phosphorylated Aβ

- B-Aβ

(biochemical) Aβ maturation stage

- hAP score

hippocampal anterior–posterior expansion score

- NFT

neurofibrillary tangles

- nonAD

control cases

- p-preAD

pathologically diagnosed preclinical Alzheimer’s disease

- p-τ

phosphorylated tau protein

- symAD

symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease

Contributor Information

Xiaohang Li, Department of Imaging and Pathology, Laboratory of Neuropathology, Leuven Brain Institute, KU-Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Simona Ospitalieri, Department of Imaging and Pathology, Laboratory of Neuropathology, Leuven Brain Institute, KU-Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Tessa Robberechts, Department of Imaging and Pathology, Laboratory of Neuropathology, Leuven Brain Institute, KU-Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Linda Hofmann, Institute of Pathology, Laboratory of Neuropathology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany.

Christina Schmid, Institute of Pathology, Laboratory of Neuropathology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany.

Ajeet Rijal Upadhaya, Institute of Pathology, Laboratory of Neuropathology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany.

Marta J Koper, Department of Imaging and Pathology, Laboratory of Neuropathology, Leuven Brain Institute, KU-Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Laboratory for the Research of Neurodegenerative Diseases, Department of Neurosciences, KU-Leuven (University of Leuven), Leuven Brain Institute, Leuven, Belgium; Center for Brain and Disease Research, VIB, Leuven, Belgium.

Christine A F von Arnim, Department of Neurology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany; Division of Geriatrics, University Medical Center Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany.

Sathish Kumar, Department of Neurology, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany.

Michael Willem, Chair of Metabolic Biochemistry, Biomedical Center, Faculty of Medicine, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Munich, Germany.

Kathrin Gnoth, Department of Drug Design and Target Validation, Fraunhofer Institute for Cell Therapy and Immunology, Halle, Germany.

Meine Ramakers, Center for Brain and Disease Research, VIB, Leuven, Belgium; Switch Laboratory, Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, KU-Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Joost Schymkowitz, Center for Brain and Disease Research, VIB, Leuven, Belgium; Switch Laboratory, Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, KU-Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Frederic Rousseau, Center for Brain and Disease Research, VIB, Leuven, Belgium; Switch Laboratory, Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, KU-Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Jochen Walter, Department of Neurology, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany.

Alicja Ronisz, Department of Imaging and Pathology, Laboratory of Neuropathology, Leuven Brain Institute, KU-Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Karthikeyan Balakrishnan, Institute of Pathology, Laboratory of Neuropathology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany; Department of Gene Therapy, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany.

Dietmar Rudolf Thal, Department of Imaging and Pathology, Laboratory of Neuropathology, Leuven Brain Institute, KU-Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; Institute of Pathology, Laboratory of Neuropathology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany; Department of Pathology, UZ-Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Funding

This study was supported by Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen [FWO- G0F8516N, G065721N (D.R.T.)], Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [TH624-6-1 (D.R.T.) and WA 1477/6-6 (J.W.)] and Alzheimer Forschung Initiative [#10810 (D.R.T.) and #17011 (S.K.)]. The Switch Laboratory was supported by the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology (VIB); KU-Leuven; the Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen (FWO, project grant G0C3522N, FWO/Hercules equipment grant NextGenQBio—AH2016.133); the Stichting Alzheimer Onderzoek (SAO-FRA 2020/0009).

Competing interests

C.A.F.v.A. received honoraria from serving on the scientific advisory board of Biogen, Roche and Dr Willmar Schwabe GmbH & Co. KG, has received funding for travel and speaker honoraria from Biogen, Roche Diagnostics AG and Dr Willmar Schwabe GmbH & Co. KG and has received research support from Roche Diagnostics AG. D.R.T. received speaker honoraria from Novartis Pharma Basel (Switzerland) and Biogen (USA), travel reimbursement from GE-Healthcare (UK) and UCB (Belgium), and collaborated with GE-Healthcare (UK), Novartis Pharma Basel (Switzerland), Probiodrug (Germany) and Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies (Belgium). D.R.T. received additional funding from Stichting Alzheimer Onderzoek (Belgium) in the context of another project and serves in the editorial board of Brain but was not involved in the handling of this manuscript at any stage.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

References

- 1. Alzheimer's Association . 2016Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12: 459–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alzheimer A. Über eine eigenartige Erkrankung der Hirnrinde. Allg Zschr Psych. 1907;64:146–148. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, Multhaup G, McDonald BL, Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4245–4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Quinlan M, Tung YC, Zaidi MS, Wisniewski HM. Microtubule-associated protein tau. A component of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. J Biol Chem 1986;261: 6084–6089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thal DR, Rüb U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of Abeta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology. 2002;58:1791–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thal DR, Capetillo-Zarate E, Del Tredici K, Braak H. The development of amyloid beta protein deposits in the aged brain. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2006;2006:re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Braak H, Del Tredici K. Alzheimer's pathogenesis: is there neuron-to-neuron propagation? Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:589–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Calafate S, Buist A, Miskiewicz K, et al. Synaptic contacts enhance cell-to-cell tau pathology propagation. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1176–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iba M, McBride JD, Guo JL, Zhang B, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Tau pathology spread in PS19 tau transgenic mice following locus coeruleus (LC) injections of synthetic tau fibrils is determined by the LC's afferent and efferent connections. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130:349–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ye L, Hamaguchi T, Fritschi SK, et al. Progression of seed-induced abeta deposition within the limbic connectome. Brain Pathol. 2015;25:743–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rijal Upadhaya A, Kosterin I, Kumar S, et al. Biochemical stages of amyloid β-peptide aggregation and accumulation in the human brain and their association with symptomatic and pathologically-preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2014;137:887–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gerth J, Kumar S, Rijal Upadhaya A, et al. Modified amyloid variants in pathological subgroups of beta-amyloidosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5:815–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dickson DW. The pathogenesis of senile plaques. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:321–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jucker M, Walker LC. Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2013;501:45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peng C, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Protein transmission in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16:199–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Meyer-Luehmann M, Coomaraswamy J, Bolmont T, et al. Exogenous induction of cerebral beta-amyloidogenesis is governed by agent and host. Science. 2006;313:1781–1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Herard AS, Petit F, Gary C, et al. Induction of amyloid-beta deposits from serially transmitted, histologically silent, abeta seeds issued from human brains. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8:205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gary C, Lam S, Herard AS, et al. Encephalopathy induced by Alzheimer brain inoculation in a non-human primate. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jaunmuktane Z, Mead S, Ellis M, et al. Evidence for human transmission of amyloid-beta pathology and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Nature. 2015;525:247–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cali I, Cohen ML, Haik S, et al. Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease with amyloid-beta pathology: An international study. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018;6:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jaunmuktane Z, Quaegebeur A, Taipa R, et al. Evidence of amyloid-beta cerebral amyloid angiopathy transmission through neurosurgery. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;135:671–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Langer F, Eisele YS, Fritschi SK, Staufenbiel M, Walker LC, Jucker M. Soluble abeta seeds are potent inducers of cerebral beta-amyloid deposition. J Neurosci. 2011;31:14488–14495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stohr J, Condello C, Watts JC, et al. Distinct synthetic abeta prion strains producing different amyloid deposits in bigenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:10329–10334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ye L, Rasmussen J, Kaeser SA, et al. Abeta seeding potency peaks in the early stages of cerebral beta-amyloidosis. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:1536–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mintun MA, Lo AC, Duggan Evans C, et al. Donanemab in early Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1691–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Novotny R, Langer F, Mahler J, et al. Conversion of synthetic Abeta to in vivo active seeds and amyloid plaque formation in a hippocampal slice culture model. J Neurosci. 2016;36: 5084–5093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ye L, Fritschi SK, Schelle J, et al. Persistence of Abeta seeds in APP null mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1559–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thal DR, von Arnim C, Griffin WS, et al. Pathology of clinical and preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;263:S137–S145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thal DR, Ronisz A, Tousseyn T, et al. Different aspects of Alzheimer's disease-related amyloid beta-peptide pathology and their relationship to amyloid positron emission tomography imaging and dementia. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7:178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kumar S, Wirths O, Theil S, Gerth J, Bayer TA, Walter J. Early intraneuronal accumulation and increased aggregation of phosphorylated Abeta in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Orantes M, Wiestler OD. Vascular pathology in Alzheimer’s disease: correlation of cerebral amyloid angiopathy and arteriosclerosis/lipohyalinosis with cognitive decline. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:1287–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sturchler-Pierrat C, Abramowski D, Duke M, et al. Two amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse models with Alzheimer disease-like pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13287–13292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sturchler-Pierrat C, Staufenbiel M. Pathogenic mechanisms of Alzheimer's disease analyzed in the APP23 transgenic mouse model. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;920:134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Capetillo-Zarate E, Staufenbiel M, Abramowski D, et al. Selective vulnerability of different types of commissural neurons for amyloid beta-protein induced neurodegeneration in APP23 mice correlates with dendritic tree morphology. Brain. 2006;129:2992–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Page RM, Gutsmiedl A, Fukumori A, Winkler E, Haass C, Steiner H. Beta-amyloid precursor protein mutants respond to gamma-secretase modulators. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:17798–17810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goodpaster T, Randolph-Habecker J. A flexible mouse-on-mouse immunohistochemical staining technique adaptable to biotin-free reagents, immunofluorescence, and multiple antibody staining. J Histochem Cytochem. 2014;62:197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rijal Upadhaya A, Capetillo-Zarate E, Kosterin I, et al. Dispersible amyloid β-protein oligomers, protofibrils, and fibrils represent diffusible but not soluble aggregates: Their role in neurodegeneration in amyloid precursor protein (APP) transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:2641–2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Konstantoulea K, Guerreiro P, Ramakers M, et al. Heterotypic amyloid beta interactions facilitate amyloid assembly and modify amyloid structure. EMBO J. 2022;41:e108591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ashby EL, Miners JS, Kumar S, Walter J, Love S, Kehoe PG. Investigation of Abeta phosphorylated at serine 8 (pAbeta) in Alzheimer's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and vascular dementia. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2015;41:428–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thal DR, Sassin I, Schultz C, Haass C, Braak E, Braak H. Fleecy amyloid deposits in the internal layers of the human entorhinal cortex are comprised of N-terminal truncated fragments of Abeta. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Libard S, Walter J, Alafuzoff I. In vivo characterization of biochemical variants of amyloid-beta in subjects with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus and Alzheimer's disease neuropathological change. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;80:1003–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schlenzig D, Manhart S, Cinar Y, et al. Pyroglutamate formation influences solubility and amyloidogenicity of amyloid peptides. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7072–7078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kumar S, Rezaei-Ghaleh N, Terwel D, et al. Extracellular phosphorylation of the amyloid beta-peptide promotes formation of toxic aggregates during the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. EMBO J. 2011;30:2255–2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rezaei-Ghaleh N, Amininasab M, Kumar S, Walter J, Zweckstetter M. Phosphorylation modifies the molecular stability of beta-amyloid deposits. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mandler M, Walker L, Santic R, et al. Pyroglutamylated amyloid-beta is associated with hyperphosphorylated tau and severity of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:67–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Morales R, Bravo-Alegria J, Duran-Aniotz C, Soto C. Titration of biologically active amyloid-beta seeds in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Duran-Aniotz C, Morales R, Moreno-Gonzalez I, Hu PP, Soto C. Brains from non-Alzheimer's individuals containing amyloid deposits accelerate Abeta deposition in vivo. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2013;1:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Grothe MJ, Barthel H, Sepulcre J, et al. In vivo staging of regional amyloid deposition. Neurology. 2017;89:2031–2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hanseeuw BJ, Betensky RA, Mormino EC, et al. PET staging of amyloidosis using striatum. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:1281–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Thal DR, Beach TG, Zanette M, et al. Estimation of amyloid distribution by [(18)F]flutemetamol PET predicts the neuropathological phase of amyloid beta-protein deposition. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136:557–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gomes LA, Hipp SA, Rijal Upadhaya A, et al. Abeta-induced acceleration of Alzheimer-related tau-pathology spreading and its association with prion protein. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;138:913–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ruan Z, Pathak D, Venkatesan Kalavai S, et al. Alzheimer's disease brain-derived extracellular vesicles spread tau pathology in interneurons. Brain. 2021;144:288–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lemere CA, Blusztajn JK, Yamaguchi H, Wisniewski T, Saido TC, Selkoe DJ. Sequence of deposition of heterogeneous amyloid beta-peptides and APO E in down syndrome: Implications for initial events in amyloid plaque formation. Neurobiol Dis. 1996;3:16–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sevigny J, Chiao P, Bussiere T, et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Abeta plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2016;537:50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All cases are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 with the main parameters obtained throughout this study, with the main clinical diagnosis, age and sex. Due to legislation and privacy protection any medical reports and files of the cases included in this study cannot be made available. Mean and standard deviations from mouse experiments are provided in Table 2. Data describing statistical results are presented in the respective figure legends, in the ‘Results’ section and in Supplementary Table 3. More detailed data will be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.