Abstract

KEY POINTS

Awareness of various venues and tiers of alcohol use disorder (AUD) care offered outside of the liver clinic is important to hepatologists in their role as liaisons and supporters of psychological treatments, which favorably contribute to liver health

Levels of AUD care range from in-clinic interventions to inpatient medical and residential services

No single AUD treatment is appropriate for every patient at every point in their AUD recovery; treatment modality and care venue should be personalized to clinical needs, patient preferences, and available resources

The American Society of Addiction Medicine has published multidimensional criteria and assessment tools that may aid hepatologists in connecting patients with AUD treatment

Not all effective AUD treatment comes from clinicians; other concurrent and adjunctive interventions have shown promise including nonclinical recovery coaches and technology-assisted treatments.

INTRODUCTION

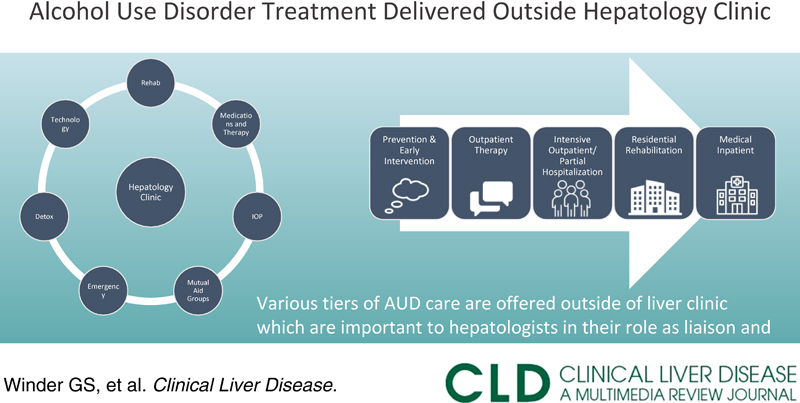

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment is increasingly becoming a foundational element of hepatology research and clinical care. Elsewhere in this issue, elements of AUD treatment feasible within a general hepatology practice have been reviewed such as screening, communication strategies and psychotherapeutic techniques, and pharmacotherapy. Many core aspects of AUD management however are unlikely to be available or feasible within a typical hepatology clinic, and a general review of these crucial components is the focus of this article (Figure 1). While few hepatologists will have the training to administer or oversee higher tiers of AUD treatment in these various settings, this article is written to equip clinicians with practical information enabling them to initiate and/or coordinate treatment and encourage ongoing patient participation.

FIGURE 1.

AUD treatments and resources available outside of the hepatology clinic. Abbreviation: IOP, intensive outpatient.

MATCHING PATIENTS TO APPROPRIATE TREATMENT

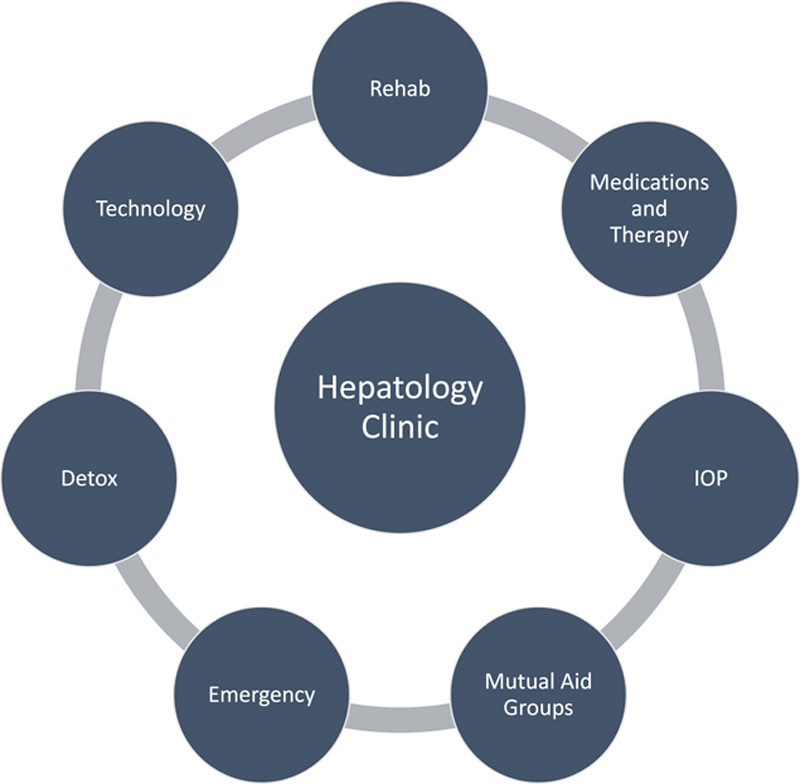

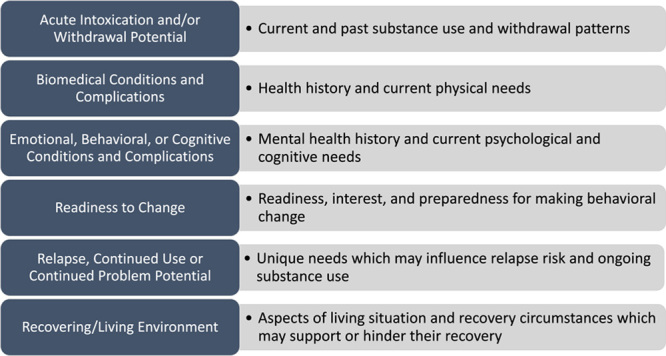

The American Society of Addiction Medicine has published multidimensional criteria (Figure 2) to increase the likelihood that different patient populations are matched to appropriate levels and modalities of care for substance use disorders (SUD) and other addictive behaviors.1 Several general ideas and strategies are pertinent for hepatologists encountering AUD.2 No single AUD treatment is appropriate and effective for all patients given individual problems, needs, resources, skills, and personal strengths. Patients’ level of care should be the least intensive, which still maintains safety and adequately addresses treatment objectives. Prospective objective assessment of patients’ progress across the SUD care continuum (Figure 3) is important to gauge clinical response and adjust the treatment plan. (The use of standardized scales, toxicology, and serial clinical interviews, as discussed elsewhere in this issue, are key components of this work.) Rather than paternalistically directing AUD patients on what to do, ideally clinicians are partners, helping patients discover their own motivations for making changes and engaging with the treatment.3 Motivational interviewing is a paradigm and communication strategy useful in accomplishing the crucial goal of patients’ mobilizing their own reasons and determination for change. Treatment should address myriad needs in patients’ lives, not just SUD symptoms.

FIGURE 2.

Six assessment dimensions in the American Society of Addiction Medicine criteria for substance use disorder treatment.

FIGURE 3.

Ascending levels of AUD treatment in terms of clinical urgency and treatment intensity.

Patients uniquely trust hepatologists since they are frequently focused the most on biomedical aspects of their liver disease rather than their drinking.4 This means that, while hepatologists may not be SUD experts, they play crucial roles in helping patients realize the relevance of AUD treatment to liver health and develop the motivation to engage.

ALCOHOL WITHDRAWAL AND DETOXIFICATION

Hepatologists should routinely evaluate the medical stability of liver patients who are actively drinking or have recently stopped, particularly in circumstances of high frequency, quantity, and chronicity. Patients who are withdrawing are unlikely to engage with or complete any AUD treatment. Active or historical complicated alcohol withdrawal (seizures, delirium tremens, hallucinosis, and intensive care unit admissions) should prompt a hepatologist to recommend inpatient medical admission before any other AUD interventions. A postacute withdrawal syndrome has been described as consisting of the symptoms of anxiety, irritability, and sleep disturbances, which continue past 30 days from the initiation of acute withdrawal; this period constitutes a substantial relapse risk.

Mild withdrawal symptoms (eg, cravings, headaches, insomnia, tremor, anxiety, sweating, and nausea) may not require medical admission but are targets for outpatient pharmacotherapy. Given the risks of benzodiazepines in patients with AUD (ie, misuse, dependence, risks of central nervous system depression when combined with alcohol, etc.) and/or decompensated alcohol-associated cirrhosis (ie, worsening HE),5 hepatologists should avoid prescribing these medications unless absolutely medically necessary. Gabapentin, a renally cleared medication with other off-label AUD uses, can treat mild alcohol withdrawal.6

PSYCHIATRIC EMERGENCIES AND HOSPITALIZATION

As hepatologists become more adept at detecting and interpreting patients’ psychology, it is inevitable that they will encounter psychiatric emergencies. Such emergencies typically involve safety (ie, harm to self or others) and/or the patients’ ability to care for themselves and understand the need for treatment. Like the rationale for emergency department referral when signs of physiological instability are present, which require further assessment, hepatologists should refer to a psychiatric emergency (if present in the community or institution) or the main emergency department upon detecting acute psychological instability and risk.

RESIDENTIAL REHABILITATION

Residential rehabilitation is 24-hour AUD care over days to months in non-hospital settings. Some facilities offer integrated detoxification services. Length of stay is determined by patient consent, clinical need, insurance coverage, and treatment response. Residential services are designed for patients who are unlikely to maintain sobriety outside of a more intensive and structured care environment. Care paradigms in this treatment setting often include elements from the 12 steps and cognitive behavioral therapy. Treatment may integrate with the patients’ employment (ie, occupational training) and any ongoing legal proceedings (ie, drug court). Residential programs may use the therapeutic community model, a longer-term intervention (ie, 6-12 months) where a patient’s living environment includes housing, staff, and other residents all involved in the treatment process. While the literature surrounding residential treatment efficacy is mixed in terms of quality and context, it has shown to be effective for a variety of outcomes.7

INTENSIVE OUTPATIENT / PARTIAL HOSPITALIZATION

Intensive outpatient and partial hospitalization programs are important and effective aspects of AUD treatment.8 They may be prescribed as primary treatment or as a subsequent phase of care following residential treatment, effectively functioning as a step-down and transition to ambulatory care. While format and philosophy vary, they tend to consist of ~9 hours of clinical programming per week, usually in 3-hour sessions, lasting 2–4 weeks. Curricula tend to include individual, group, and family therapies, which focus on facets of substance use and other mental disorders. Patients live at home, which reduces costs and lifestyle impact, as compared with residential treatment, and allows more immediate application of treatment to daily life.

MUTUAL HELP GROUPS

Alcoholics Anonymous is the most prominent 12-step recovery program, with evidence supporting its effective treatment of AUD.9 It is a ubiquitous peer fellowship who meet regularly to offer mutual support and share experiences to achieve and maintain sobriety. The program consists of working through 12 steps and adopting 12 traditions, often with sponsorship from another Alcoholics Anonymous member. Al-Anon is another 12-step fellowship that seeks to support the family and friends of patients with AUD. Another widely available non-12-step group is SMART Recovery, a program that focuses on building motivation for sobriety, dealing effectively with cravings, managing emotions, and living a balanced life. Patients can locate meetings online using websites (eg, https://aa.org/find-aa, https://meetings.smartrecovery.org/meetings/location) or apps (eg, Meeting Finder).

SPECIALTY PSYCHOTHERAPY AND MEDICATION MANAGEMENT

Unless a hepatology clinic has integrated psychiatric services, liver clinicians will commonly refer to outside clinicians for specialized AUD psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy modalities, which may be provided by a single clinician or multiple providers (ie, a patient sees a psychiatrist for AUD medications and a social worker for psychotherapy). Psychotherapies may last from months to years in duration and at varying frequencies. Clinical foci and objectives include increasing motivation, identifying triggers and circumstances for use, improved coping with cravings and emotional distress, optimized social functioning, sobriety maintenance strategies, and analyzing the antecedents and consequences of drinking.

Patients with AUD often have comorbid psychiatric conditions for which medications may be helpful. Psychiatric clinicians often have reservations about prescribing to patients with liver disease and complex medication regimens indicating another area where a partnership with hepatology can ensure patient access to adequate treatment. Some psychotherapy modalities and medications have been tested in liver disease and transplant populations.10

OTHER RESOURCES

While care management is most often used for patients with chronic and severe mental illnesses, it also has distinct utility in the management and coordination of medical and psychiatric pathology, particularly when ongoing long-term management is anticipated, patients’ clinicians may not be within the same institution, and the possibility of nonadherence is high. Hepatologists may find that care managers dedicated to ALD may function well to coordinate and organize treatment and address basic social matters, which may interfere with adherence.

Recovery coaches are an increasingly common element of AUD treatment where non-clinicians offer an array of mentoring, education, and support services, often in conjunction with other aspects of the patients’ AUD care. The literature is inconclusive regarding coaching’s effects on clinical outcomes.11

A variety of technology-assisted therapies (online counseling, text messages, and smartphone apps) are becoming increasingly common. Many of these resources are self-directed and show promise for efficacy though the evidence of their effects is mixed.12

CONCLUSION

AUD is increasingly important to the hepatologists’ practice creating their pivotal role as collaborators with and advocates for psychiatric treatments relevant to liver health. The epidemiology of AUD and ALD ensures that this topic will be crucial for the foreseeable future, and future research must include innovative ways to integrate and optimize psychiatric and hepatology care.

Acknowledgments

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Gerald Scott Winder consults for Alexion. Erin G. Clifton has no conflicts to report.

EARN MOC FOR THIS ARTICLE

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; IOP, intensive outpatient; SUD, substance use disorders.

Contributor Information

Gerald Scott Winder, Email: gwinder@med.umich.edu.

Erin G. Clifton, Email: erindef@med.umich.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mee-Lee D, Shulman G, Fishman M. The ASAM criteria. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mee-Lee D, Shulman GD.Ries RK, Fiellin DA, Miller SC, Saitz R. The ASAM criteria and matching patients to treatment. The ASAM principles of addiction medicine, 5th ed. [s.l.]: Wolters Kluwer; 2014:428–441. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change. New York; London: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellinger JL, Scott Winder G, DeJonckheere M, Fontana RJ, Volk ML, Lok ASF, et al. Misconceptions, preferences and barriers to alcohol use disorder treatment in alcohol-related cirrhosis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;91:20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tapper EB, Henderson JB, Parikh ND, Ioannou GN, Lok AS. Incidence of and risk factors for hepatic encephalopathy in a population-based cohort of Americans with cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2019;3:1510–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason BJ, Quello S, Shadan F. Gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2018;27:113–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Andrade D, Elphinston RA, Quinn C, Allan J, Hides L. The effectiveness of residential treatment services for individuals with substance use disorders: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;201:227–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarty D, Braude L, Lyman DR, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Ghose SS, et al. Substance abuse intensive outpatient programs: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:718–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M. Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;3:Cd012880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winder GS, Shenoy A, Dew MA, DiMartini AF. Alcohol and other substance use after liver transplant. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;46-47:101685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eddie D, Hoffman L, Vilsaint C, Abry A, Bergman B, Hoeppner B, et al. Lived experience in new models of care for substance use disorder: A systematic review of peer recovery support services and recovery coaching. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colbert S, Thornton L, Richmond R. Smartphone apps for managing alcohol consumption: a literature review. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2020;15:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]