Abstract

Scope:

To avoid ingestion of potentially harmful substances humans are equipped with about 25 bitter taste receptor genes (TAS2R) expressed in oral taste cells. Humans exhibit considerable variances in their bitter tasting abilities, which are associated with genetic polymorphisms in bitter taste receptor genes. One of these variant receptor genes, TAS2R2, was initially believed to represent a pseudogene. However, TAS2R2 exists in a putative functional variant within some populations and can therefore be considered as an additional functional bitter taste receptor.

Methods and results:

To learn more about the function of the experimentally neglected TAS2R2, we performed a functional screening with 122 bitter compounds. We observed responses with 8 of the 122 bitter substances and identified the substance phenylbutazone as a unique activator of TAS2R2 among the family of TAS2Rs, thus filling one more gap in the array of cognate bitter substances.

Conclusions:

The comprehensive characterization of the receptive range of TAS2R2 allowed the classification into the group of TAS2Rs with a medium number of bitter agonists. The variability of bitter taste and its potential influence on food choice in some human populations might be even higher than assumed.

Keywords: bitter taste receptor, calcium-mobilization assay, genetic variant, functional screening, G protein-coupled receptor

Graphical Abstract

The human bitter taste receptor TAS2R2 was for a long time mostly considered to represent a non-functional pseudogene. However, in a few human populations a functional variant of the TAS2R2 gene exists. In the current study, we demonstrate that functional TAS2R2 responds to a medium number of bitter substances including phenylbutazone, a bitter compound previously not associated with any of the other 25 human bitter taste receptors.

1. Introduction

The recognition of bitter compounds in the oral cavity plays an important role for the avoidance of ingestion of potentially harmful food constituents [1]. In humans, approximately 25 potentially functional bitter taste receptors (taste 2 receptors encoded by TAS2R genes) are expressed in a heterogeneous pattern in taste buds of the oral cavity [2]. Thus far, for 21 of the 25 receptors bitter agonists have been identified, which has revealed considerable differences in their agonist selectivities [3,4]. Three receptors, TAS2R10 [5,6], TAS2R14 [7,8] and TAS2R46 [9,10], are broadly tuned and each is able to detect a considerable number of chemically diverse bitter compounds [3,11]. In contrast, several receptors seem to have a very restricted spectrum of agonists [3] and two receptors, TAS2R16 [6] and TAS2R38 [12], are highly selective for β-D-glucopyranosides and isothiocyanates/thioureas, respectively. The majority of TAS2R exhibit intermediate-sized agonist profiles [3]. The differently tuned receptor classes may have played important, complementary roles during evolution, such that the broadly tuned receptors might have been crucial during explorative phases when novel bitter compounds are encountered, while the narrowly tuned or compound selective receptors could represent adaptations to specific habitats [7,13]. When bitter taste receptors were initially discovered, their published numbers, first estimated and then later confirmed, fluctuated to some degree [6,14–19]. This was partly due to the high variability present within many of the TAS2R genes, a fact that was realized subsequently [20,21]. Good examples for this are the frequent copy number mutations affecting TAS2R43 and TAS2R45 as well as the existence of truncated TAS2R variants caused by frame shift mutations or the introduction of stop codons in the polypeptide chain [20,22–24]. The latter resulted in the assignment of TAS2R46 as functional receptor, although a truncated variant occurs with high frequency in the human population [20], and in another instance, the assignment of TAS2R2 as pseudogene although some populations carry a functional TAS2R2 variant [16,19,25,26].

Hence, the number of postulated intact TAS2R genes that an individual carries in the genome fluctuates around 25 and overall, it is likely that, due to segregating TAS2R pseudogenes, more than 25 TAS2Rs contribute to bitterness perception in humans. Recently, we investigated the agonist profiles of three human pseudogenes by restoring their function using the intact sequences of the corresponding chimpanzee orthologs [26]. Among the rescued pseudogenes, TAS2R2 was also re-functionalized by correction of an early stop codon. The re-functionalized TAS2R2 was subjected to a limited screening with 83 natural and synthetic bitter compounds and 3 agonists were identified.

Here, we sought to accurately classify TAS2R2 amongst the other 25 TAS2Rs and to expand our functional screening using more bitter compounds to better match our previous TAS2R profiling efforts and to better understand the TAS2R2 agonist profile.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Chemicals

All agonist test substances (see supplementary table 1) were dissolved as stock solutions depending on their solubility in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or C1 buffer (130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES; pH 7.4) and then diluted to the desired maximum concentration (supplementary table 1) and additionally as a 1 to 10 dilution with the C1 buffer. The final DMSO concentration remained below 1% during the measurement.

2.2. Functional calcium mobilization assay

2.2.1. Generation of the TAS2R2 construct

The TAS2R2 open reading frame was modified in vitro to restore its functionality using sequence data of the human functional version of this gene from database information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs57689054) as a template to mutate the non-functional variant. This was done by changing the human stop codon to the respective amino acid in the functional variant by inserting AT at positions 447–448 in the human gene as previously described [26]. The successful expression of the construct in HEK 293T-Gα16gust44 cells was confirmed by immunocytochemical staining using an anti-hsv antiserum recognizing the carboxy terminally added hsv-tag in a previous publication. The determined average expression rate was 10.2% ± 5.2% [26].

2.2.2. Screening of compounds with TAS2R2.

The functional screening experiments were performed as published previously (Lang et al., 2020; Ziegler and Behrens, 2021). Briefly, HEK 293T-Gα16gust44 cells were cultivated on poly-D-lysine coated 96 wells plates under regular conditions (DMEM, 10% FCS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% glutamine; 37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity) and transiently transfected with cDNA constructs coding for TAS2R2 [26] using lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany). Empty vector (mock) was transfected as a negative control. About 24 h after transfection, cells were stained for 1 h with Fluo4-AM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany) in the presence of probenecid (2.5 mM, Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) and then washed with C1 buffer and placed in a fluorometric imaging plate reader (FLIPRTetra, Molecular Devices, San Jose, USA). After automated application of the bitter substances to the cells, changes in fluorescence (at 510 nm excitation and at 488 nm emission) were measured. Cell viability was confirmed by subsequently adding somatostatin 14 (100 nM, Bachem, Bubendorf, Switzerland) to the cells and measuring the fluorescence emitted by stimulation of an endogenous GPCR.

Recording and calculation of dose-response relationships.

HEK 293T-Gα16gust44 cells were transfected with TAS2R2 or an empty vector control identical to that used in screening experiments. The identified bitter activators of TAS2R2 were diluted with C1 buffer and measured analogously to the screening experiments. The determination of the results was based on three independent measurements each performed in duplicate. For calculating the compound-specific fluorescence changes (ΔF/F), mock was subtracted and data were normalized to background fluorescence. Plots were generated using SigmaPlot 14.0.

2.3. Molecular modeling

The 3D computational structures of TAS2R2 were generated by homology modeling using as template the human TAS2R46 receptor structure (PDB ID: 7XP5) [27]. Sequence alignment and homology modeling were performed with Prime (Schrödinger Release 2021–3: Prime, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2021). TAS2R2 has a sequence similarity to TAS2R46 of 47%. The ligand binding site was calculated with Sitemap (Schrödinger Release 2021–3: SiteMap, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2021) and it is predicted to overlap with the orthosteric binding site of TAS2Rs [27].

3. Results

For functional screening the TAS2R2 was transiently transfected in HEK293T-Gα16gust44 cells and calcium mobilization assays were performed. In total 122 bitter compounds were screened at two different concentrations, the maximal concentration not resulting in receptor-independent cellular signals or, for compounds exhibiting limited solubilities, the maximal soluble concentration (see table 1), as well as 10-fold dilutions thereof. Compounds resulting in fluorescence changes significantly greater than the corresponding empty vector controls were selected for confirmation of receptor responses (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Threshold concentrations of TAS2R2 activating bitter compounds.

| TAS2R2 activator | threshold [mM] |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Chlorhexidine | 0.003 |

| Chloroquinine | 3 |

| 1,10-Phenanthroline | 1 |

| Phenylbutazone | 0.03 |

| Picrotoxinin | 1 |

| PROP | 3 |

| Thiamine | 1 |

| Yohimbin | 0.3 |

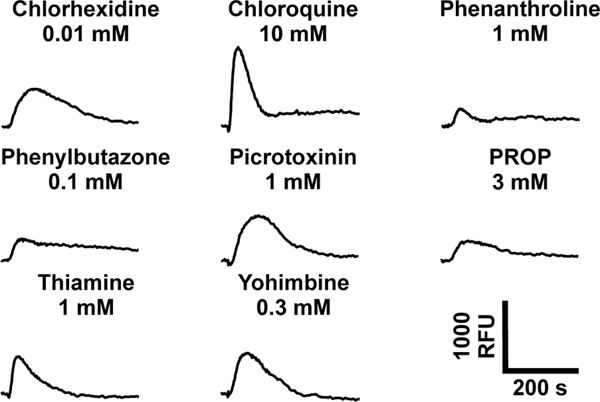

Figure 1. Eight bitter compounds were identified as TAS2R2 agonists.

Shown are the fluorescence traces of TAS2R2 expressing cells stimulated with the indicated bitter substances. The applied concentrations are labeled. Scale bar, bottom right.

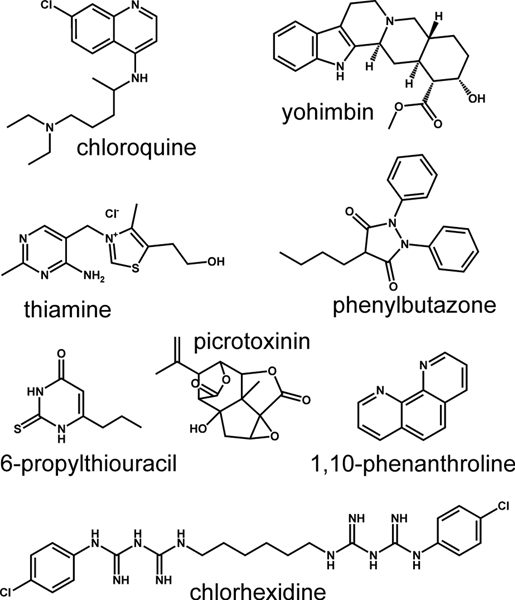

In total we identified 8 substances that activated TAS2R2 expressing cells. The compounds chlorhexidine, thiamine and chloroquine confirmed our previous findings [26]. The five newly discovered agonists are yohimbine, picrotoxinin, 1,10-phenanthroline, phenylbutazone, and 6-n-propyl-thiouracil (PROP). The TAS2R2 response to phenylbutazone, which has been used for screening 25 human TAS2R previously [28] is unique among the 26 TAS2Rs. From these data we can conclude that TAS2R2 detects natural and synthetic bitter compounds without showing a bias for one particular chemical class. The structural formulas of the TAS2R2 activators (Figure 2) suggest that the detection spectrum of this receptor is, unlike the TAS2R16 and TAS2R38, not tailored to a recognizable chemical class, although the existence of at least one, but usually more than one, ring systems, which are mostly aromatic, is clear.

Figure 2. Chemical structures of agonists activating human TAS2R2.

Shown are the structural formulas of the 8 activators among the 122 bitter test compounds used for the screening.

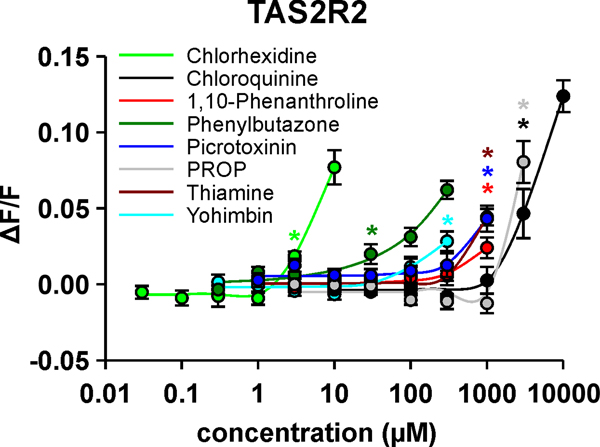

To identify the concentration ranges for the detection of the 8 agonists, dose-response relationships were measured (Figure 3, supplementary figure 1). We observed a range of different sensitivities with different agonists, with chlorhexidine exhibiting the highest potency and PROP and chloroquine exhibiting the lowest potencies. Phenylbutazone, followed by yohimbin and the three substances thiamine, picrotoxinin and 1,10-phenanthroline showed intermediate potencies. As none of the substances could be applied in signal saturating concentrations without resulting in substantial receptor-independent artefacts, EC50-concentrations were not determined.

Figure 3. Determinations of dose-response relationships for agonists of human TAS2R2.

The TAS2R2 cDNA was transiently transfected in HEK 293T-Gα16gust44 cells. 24 h after transfection, cells were loaded with Fluo4-am, placed in a fluorometric imaging plate reader (FLIPRtetra) and challenged with increasing concentrations of the indicated bitter compounds. The changes in fluorescence upon agonist stimulation were monitored and plotted to the y-axis (ΔF/F). The applied concentrations were plotted to the logarithmically scaled x-axis. The obtained response relationships are color coded according to the test compounds. Colored asterisks highlight the lowest compound concentrations eliciting signals significantly different from the corresponding mock controls (= threshold concentrations, p≤ 0.05, Student’s t-test).

The threshold concentrations summarized in Table 1 demonstrate activation by chlorhexidine, phenylbutazone and yohimbine in the low to high micromolar range typical for many TAS2R responses. The other 5 substances start to elicit receptor activities in the low millimolar range, which represent insensitive responses.

Comparing the TAS2R2 response profile with the other 25 receptors, we can classify the TAS2R2 as another intermediately tuned human bitter taste receptor being activated by 8 of 122 bitter compounds (~7%) comparable to the previously defined receptor group showing responses to ~5–15% of the bitter compounds tested [3]. Hence, TAS2R2 can be grouped together with the previously defined group consisting of TAS2R1, -R4, -R30, -R31, -R39, -R40, and -R43.

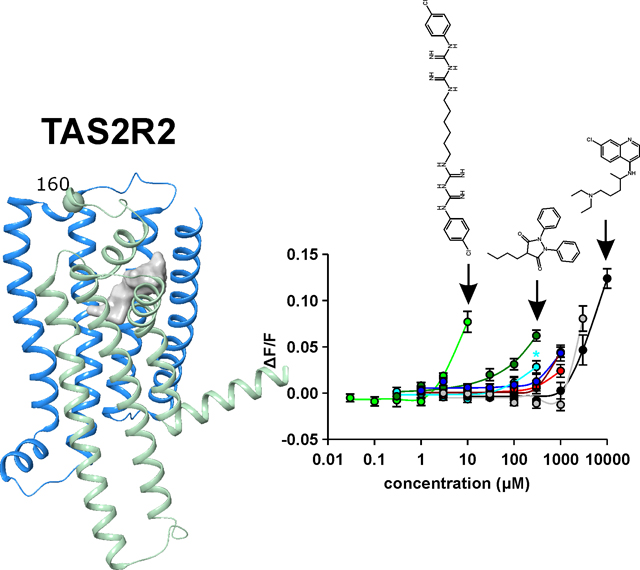

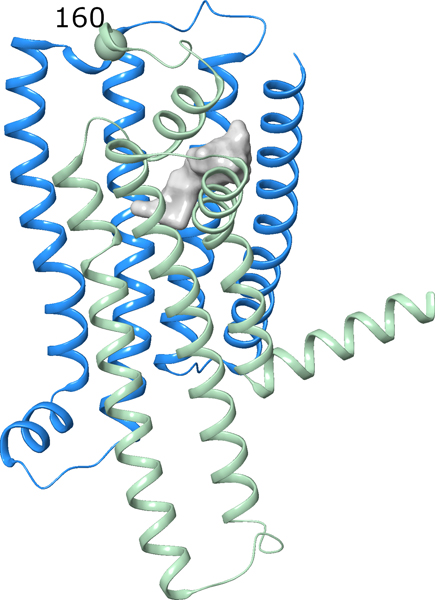

Moreover, molecular modeling of the TAS2R2 suggests that neither the 3D architecture nor the localization of the ligand binding pocket deviates substantially from the other functional TAS2Rs (Figure 4), however, the pseudogenized variant lacks large parts of the polypeptide chain (including transmembrane domains 5, 6 and 7) that leads to its non-functional status.

Figure 4.

3D representation of the TAS2R2 structure model. The ligand binding site (area: 485 Å2, calculated with SiteMap, Schroedinger) is shown as a molecular surface and colored in grey. The region of the receptor that is truncated in the pseudogenized variant is colored in light green, the amino acid position at which the frame-shift mutation occurs in the non-functional variant (160) is labeled by a ball.

4. Discussion

In the current study TAS2R2, a human bitter taste receptor long considered to be a pseudogene, was functionally analyzed with a large set of bitter compounds. In an initial study this receptor was re-functionalized by modifying its coding sequence to correct a frame-shift mutation by the insertion of “AT” at the corresponding position [26]. In previous studies, the modified TAS2R2 was screened and deorphaned, revealing its activation by three agonists among the 83 substances tested. This study was very successful in proving that it is possible to re-functionalize pseudogenized human TAS2Rs and it elucidated which bitter responses might have been lost during evolution. However, to classify this receptor as in previous comprehensive studies [3,28] the number of bitter compounds that were screened was insufficient. Here, screening TAS2R2 expressing cells with the majority of compounds used to deeply characterize the other 25 human TAS2Rs now revealed that TAS2R2 belongs to the class of intermediately tuned receptors. Moreover, the concentration range at which agonists are recognized also fits with that of the “average” TAS2R, starting with a threshold concentration of 3 μM for the synthetic compound chlorhexidine and ending with 3 mM chloroquine and, surprisingly, 6-propyl-thiourea (PROP). A previous screening of TAS2R2 with up to 1 mM PROP did not result in a visible activation [26], suggesting that 3 mM PROP must be at or close to the threshold concentration of this receptor. This is three orders of magnitude above the concentration PTC/PROP tasters can perceive in vivo. While there is overwhelming evidence that the dominant receptor for the sensitive detection of PROP and the related PTC is the taster variant of human TAS2R38 [29], called TAS2R38-PAV, it is commonly observed that homozygous carriers of the non-taster variant, TAS2R38-AVI, respond to high concentrations of these bitter substances [30]. In addition to the TAS2R4, which has been proposed as putative low-affinity receptor for PROP/PTC [15], TAS2R2 could likewise fill this role in populations harboring the functional variant of this gene. The previous study on the re-functionalization of TAS2R2 led to the conclusion that the receptor may have pseudogenized due to functional redundancies with extant TAS2Rs, as none of the originally identified agonists were unique for this receptor. In the current study, we found phenylbutazone, a synthetic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, is an agonist for TAS2R2 that was not detected by one of the other 25 receptors. Therefore, this receptor appears to exhibit specific agonist interactions, although it remains to be seen if natural agonists relevant during human evolution can be identified. The question of why the functional TAS2R2 variant is restricted to genomes of few populations, while the pseudogene is dominant in the majority of populations cannot be answered by our study. However, the set of agonists we have identified seems to indicate a certain specialization for agonists rich in mesomeric ring systems which could have played a major role for human survival in general in the past. The few populations that currently carry a high frequency of the intact TAS2R2 gene might have had longer exposure to the source of toxic TAS2R2 agonists [31,32].

Except for phenylbutazone, all other TAS2R2 agonists are recognized by at least one of the other TAS2R at similar or lower threshold concentrations (table 2), suggesting that redundancies of agonist spectra with extant receptors might indeed have been a reason for the pseudogenization of TAS2R2 as concluded previously [26].

Table 2.

Comparison of TAS2R2 activating compounds and their threshold concentrations with previously reported [3] TAS2Rs.

| TAS2R2 agonist | Threshold conc. | Other TAS2R | Threshold conc. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Chlorhexidine | 0.003 mM | TAS2R14 | 0.0001 mM |

|

| |||

| Chloroquine | 3 mM | TAS2R3 TAS2R10 TAS2R39 |

0.01 mM 10 mM 0.1 mM |

|

| |||

| 1,10-Phenanthroline | 1 mM | TAS2R5 | 0.1 mM |

|

| |||

| Phenylbutazone | 0.03 mM | - | - |

|

| |||

| Picrotoxinin | 1 mM | TAS2R1 TAS2R10 TAS2R14 TAS2R30 TAS2R46 |

1 mM 1 mM 0.003 mM 1 mM 0.01 mM |

|

| |||

| 6-propyl-thiouracil (PROP) | 3 mM | TAS2R38 | 0.00006 mM |

|

| |||

| Thiamine | 1 mM | TAS2R1 TAS2R39 |

1 mM 1 mM |

|

| |||

| Yohimbin | 0.3 mM | TAS2R1 TAS2R4 TAS2R10 TAS2R38 TAS2R46 |

0.3 mM 0.3 mM 0.3 mM 0.3 mM 0.3 mM |

|

|

|||

It has long been noticed that the intact variant of TAS2R2 is present in one Southeast-European and two separate African (pygmy) populations [25]. Hence, it seems reasonable to assume that the pseudogenization of this gene occurred quite early during Homo sapiens evolution before the migration out-of Africa began. This is consistent with the fact that the Denisovan hominin carried two copies of the functional version of the gene, whereas the Neanderthal was homozygous for the pseudogenized version [26]. It remains to be answered why the intact TAS2R2 gene has been maintained in such different regions of the world. One hypothesis would be that similar toxic bitter compounds may be found in these specific African and European areas. Another hypothesis might be that the populations with intact TAS2R2 have lost another TAS2R and required the activity of TAS2R2 to compensate for this loss. Nevertheless, it is known that chimpanzees possess intact TAS2R2 genes, and thus it seems to have played, and might still play an important role in primate survival.

Taken together our comprehensive characterization of an additional human TAS2R has allowed the classification of this receptor among the other 25 TAS2Rs and it has filled a gap our understanding of the recognition of compounds known to taste bitter. Based on these results, it seems possible that in the future, TAS2Rs currently believed to represent pseudogenes will be found in some populations as intact variants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Eva Boden for excellent technical assistance.

Funding

This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIDCD.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations:

- FLIPR

Fluorometric imaging plate reader

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- TAS2R

taste 2 receptors

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting information is available from the Wiley Online Library.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Lindemann B, Physiol Rev 1996, 76, 718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Behrens M, Foerster S, Staehler F, Raguse JD, Meyerhof W, J Neurosci 2007, 27, 12630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Meyerhof W, Batram C, Kuhn C, Brockhoff A, Chudoba E, Bufe B, Appendino G, Behrens M, Chem Senses 2010, 35, 157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Thalmann S, Behrens M, Meyerhof W, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013, 435, 267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Born S, Levit A, Niv MY, Meyerhof W, Behrens M, J Neurosci 2013, 33, 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bufe B, Hofmann T, Krautwurst D, Raguse JD, Meyerhof W, Nat Genet 2002, 32, 397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Behrens M, Brockhoff A, Kuhn C, Bufe B, Winnig M, Meyerhof W, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004, 319, 479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nowak S, Di Pizio A, Levit A, Niv MY, Meyerhof W, Behrens M, Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2018, 1862, 2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Brockhoff A, Behrens M, Massarotti A, Appendino G, Meyerhof W, J Agric Food Chem 2007, 55, 6236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brockhoff A, Behrens M, Niv MY, Meyerhof W, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 11110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bayer S, Mayer AI, Borgonovo G, Morini G, Di Pizio A, Bassoli A, J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 13916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bufe B, Breslin PA, Kuhn C, Reed DR, Tharp CD, Slack JP, Kim UK, Drayna D, Meyerhof W, Curr Biol 2005, 15, 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wooding SP, Ramirez VA, Behrens M, Evol Med Public Health 2021, 9, 431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Adler E, Hoon MA, Mueller KL, Chandrashekar J, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS, Cell 2000, 100, 693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chandrashekar J, Mueller KL, Hoon MA, Adler E, Feng L, Guo W, Zuker CS, Ryba NJ, Cell 2000, 100, 703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Conte C, Ebeling M, Marcuz A, Nef P, Andres-Barquin PJ, Cytogenet Genome Res 2002, 98, 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Conte C, Ebeling M, Marcuz A, Nef P, Andres-Barquin PJ, Physiol Genomics 2003, 14, 73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Matsunami H, Montmayeur JP, Buck LB, Nature 2000, 404, 601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shi P, Zhang J, Yang H, Zhang YP, Mol Biol Evol 2003, 20, 805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kim U, Wooding S, Ricci D, Jorde LB, Drayna D, Hum Mutat 2005, 26, 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wooding S, Kim UK, Bamshad MJ, Larsen J, Jorde LB, Drayna D, Am J Hum Genet 2004, 74, 637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pronin AN, Xu H, Tang H, Zhang L, Li Q, Li X, Curr Biol 2007, 17, 1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Roudnitzky N, Bufe B, Thalmann S, Kuhn C, Gunn HC, Xing C, Crider BP, Behrens M, Meyerhof W, Wooding SP, Hum Mol Genet 2011, 20, 3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Roudnitzky N, Risso D, Drayna D, Behrens M, Meyerhof W, Wooding SP, Chem Senses 2016, 41, 649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Go Y, Satta Y, Takenaka O, Takahata N, Genetics 2005, 170, 313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Risso D, Behrens M, Sainz E, Meyerhof W, Drayna D, Mol Biol Evol 2017, 34, 1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Xu W, Wu L, Liu S, Liu X, Cao X, Zhou C, Zhang J, Fu Y, Guo Y, Wu Y, Tan Q, Wang L, Liu J, Jiang L, Fan Z, Pei Y, Yu J, Cheng J, Zhao S, Hao X, Liu Z-J, Hua T, Science 2022, 377, 1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lossow K, Hubner S, Roudnitzky N, Slack JP, Pollastro F, Behrens M, Meyerhof W, J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 15358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kim UK, Jorgenson E, Coon H, Leppert M, Risch N, Drayna D, Science 2003, 299, 1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hayes JE, Bartoshuk LM, Kidd JR, Duffy VB, Chem Senses 2008, 33, 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Behrens M, Meyerhof W, J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Risso D, Drayna D, Tofanelli S, Morini G, Curr Opin Physiol 2021, 20, 174. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.