Abstract

Objectives

A growing body of evidence shows self-compassion can play a key role in alleviating depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress in various populations. Interventions fostering self-compassion have recently received increased attention. This meta-analysis aimed to identify studies that measured effects of self-compassion focused interventions on reducing depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress.

Methods

A comprehensive search was conducted within four databases to identify relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The quality of the included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration risk-of-bias tool. Either a random-effects model or fixed-effects model was used. Subgroup analyses were conducted according to types of control groups, intervention delivery modes, and the involvement of directly targeted populations with psychological distress symptoms.

Results

Fifty-six RCTs met the eligibility criteria. Meta-analyses showed self-compassion focused interventions had small to medium effects on reducing depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress at the immediate posttest and small effects on reducing depressive symptoms and stress at follow-up compared to control conditions. The overall risk of bias across included RCTs was high.

Conclusions

Fewer studies were conducted to compare effects of self-compassion interventions to active control conditions. Also, fewer studies involved online self-compassion interventions than in-person interventions and directly targeted people with distress symptoms. Further high-quality studies are needed to verify effects of self-compassion interventions on depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress. As more studies are implemented, future meta-analyses of self-compassion interventions may consider conducting subgroup analyses according to intervention doses, specific self-compassion intervention techniques involved, and specific comparison or control groups.

Preregistration

This study is not preregistered.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12671-023-02148-x.

Keywords: Anxiety, Depression, Meta-analysis, Self-compassion, Stress

Compassion can be defined as “a basic kindness, with a deep awareness of the suffering of oneself and of other living things, coupled with the wish and effort to relieve it” (Gilbert, 2009, p. 13). In particular, compassion toward ourselves, or self-compassion, is the ability to be open to and alleviate one’s own difficulties with kindness and nonjudgmental understanding (Neff, 2003). For example, Neff (2003) has conceptualized self-compassion as entailing three interrelated elements: self-kindness (i.e., being supportive and kind to oneself rather than being self-critical with harsh judgment), common humanity (i.e., acknowledging life challenges as part of the human experience), and mindfulness (having a moment-to-moment awareness of one’s experience in a nonjudgmental and accepting way).

A growing body of evidence shows self-compassion can play an important role in alleviating depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress in various populations, including clinical (e.g., individuals with major depressive disorder and individuals with chronic pain) and nonclinical populations (e.g., undergraduate students, family caregivers of people with chronic conditions, and older adults) (Biddle et al., 2020; Bui et al., 2021; Carvalho et al., 2020; Kim & Ko, 2018; Krieger et al., 2013; Murfield et al., 2020). For example, studies found higher levels of self-compassion were related to lower levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and perceived stress (Bohadana et al., 2019; Bui et al., 2021; Kim & Ko, 2018; Krieger et al., 2013; Murfield et al., 2020) and predicted lower levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress (Bates et al., 2021; Biddle et al., 2020; Carvalho et al., 2020). Studies also showed the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship of life challenges (e.g., perceived COVID-19 threat and caregiving stress) with depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress, suggesting self-compassion buffered the impacts of life challenges on depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress (Hsieh et al., 2019; Kavaklı et al., 2020; Lau et al., 2020). Studies suggested that fostering self-compassion may reduce depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress by enhancing mindful awareness and emotion regulation and improving the ability to engage in self-compassionate actions while not engaging in symptom-focused rumination and cognitive and behavioral avoidance (Adie et al., 2021; Bates et al., 2021; Bui et al., 2021; Hsieh et al., 2019; Krieger et al., 2013; Murfield et al., 2020).

Interventions aiming to foster self-compassion have recently received increased attention. To our knowledge, the most recent meta-analyses regarding effects of self-compassion interventions on reducing depressive symptoms, anxiety, or stress were conducted in 2017 (Ferrari et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2019). In Ferrari et al. (2019), the final database search was completed in August, 2017 to identify relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in which interventions focused on self-compassion for both clinical and non-clinical human participants (i.e., without any limits on the population). The meta-analysis of Ferrari et al. (2019) found medium effects of self-compassion interventions on reducing depressive symptoms (based on 15 RCTs), anxiety (based on 14 RCTs), and stress (based on five RCTs). Wilson et al. (2019) also conducted a meta-analysis of self-compassion interventions (database search up to July, 2017) and found small effects on depressive symptoms and anxiety. However, Wilson et al. (2019) included interventions with a self-compassion component rather than including interventions focusing on self-compassion only, which might have allowed the found effects to be influenced by intervention components other than self-compassion.

Considering the increased attention on self-compassion interventions, especially in recent years, an updated meta-analysis is needed to better determine the most up-to-date evidence regarding effects of self-compassion interventions on reducing depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress. Therefore, this meta-analysis aimed to identify studies that measured the effects of self-compassion focused interventions on depressive symptoms, anxiety, or stress. The present study also aimed to conduct subgroup analyses for each outcome according to the type of control groups, when appropriate, to see whether effects of self-compassion interventions differed compared to active control groups provided with other comparable interventions and to passive control groups provided with no intervention. In addition, other subgroup analyses related to the characteristics of the included studies may be conducted and provide useful information. For example, how self-compassion focused interventions (such as in-person programs and online programs) were delivered might affect outcomes differently, and studies that directly targeted populations with psychological distress symptoms might show larger effects on these symptoms compared to non-clinical populations (Thompson et al., 2021). Therefore, the present study also aimed to conduct additional subgroup analyses according to the intervention delivery modes and the use of targeted participants with psychological distress symptoms, when applicable.

Method

This meta-analysis was conducted and reported in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., 2021) and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 5.1.0 (Higgins & Green, 2011), as a guide. The study protocol for the current review was not registered.

Search Strategy

Relevant articles were identified by searching four electronic databases from the date of inception of each database to October 9, 2021; these included PubMed (1966–2021), CINAHL (1981–2021), PsycINFO (1935–2021), and SCOPUS (1966–2021). Key search terms were combined to identify relevant literature using keywords for self-compassion and experimental research or interventions. To broaden the database search, keywords relevant to outcomes were not entered as search terms. The full search strategies for all databases can be found in the Supplemental Materials (Table S1). Articles were also manually searched by examining the reference lists of identified articles and utilizing related article features in databases. In addition, a search for recent articles published from October 10, 2021 to February 2, 2023 was conducted using electronic databases.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (a) the study must be an RCT; (b) the study must involve a self-compassion intervention; (c) self-compassion must be the core intervention component if it was accompanied by another intervention component; (d) the study must address self-compassion theory and/or literature in the introduction; (e) the study must involve a comparison or a control condition other than self-compassion; (f) the study must involve validated measures of depressive symptoms, anxiety, or stress as outcome measures; and (g) the study must be written in English and published in a peer-reviewed journal. Studies were excluded if the self-compassion intervention involved a one-time brief activity (e.g., a one-time 30-min writing activity following self-compassionate prompts) or if the intervention involved self-compassion as an intervention component only without a core focus on self-compassion. There was no limit on characteristics of participants (e.g., age, gender, and clinical conditions).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Characteristics of the included RCTs (e.g., the sample size, characteristics of participants, brief description of intervention and control groups, outcome measures, and results) were extracted into a table. Means and standard deviations (SD) for each data collection time point and sample sizes of intervention and control groups in the included studies were entered into an Excel file. The methodological quality of the included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration risk-of-bias tool (Higgins & Green, 2011). Domains in the tool include random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. Risk of bias in each of the domains was judged as “low risk” of bias, “high risk” of bias, or “unclear risk” of bias following the criteria provided in the Cochrane Collaboration’s handbook (Higgins & Green, 2011). Summary assessments of risk of bias within a study and across studies were also determined based on the handbook’s criteria (Higgins & Green, 2011). One author with extensive experiences in conducting systematic reviews with meta-analysis completed the process for data extraction and quality assessment.

Meta-analysis

Means, standard deviations, and sample sizes of intervention and control groups in the included studies were entered into RevMan Version 5.4 for meta-analyses and pooled for each outcome at the immediate posttest and at follow-up. The I2 statistic was used to measure statistical heterogeneity across studies, and I2 greater than 50% was interpreted as substantial heterogeneity (Higgins & Green, 2011). The decision for using either a random-effects model or a fixed-effects model with the inverse variance method was determined based on the I2 statistic values for each outcome. In other words, a random effects model was used when the I2 statistic for each outcome was greater than 50%, otherwise a fixed effects model was used. The standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals was used as a summary statistic for the size of the intervention effect to account for outcomes measured using different assessment tools (Higgins & Green, 2011). SMDs less than 0.4 indicate a small effect, SMDs between 0.4 and 0.7 indicate a medium effect, and SMDs greater than 0.7 indicate a large effect (Higgins & Green, 2011).

Subgroup analyses for each outcome were conducted according to the type of control groups, when appropriate, to see whether effects of self-compassion interventions differed compared to active control groups provided with other comparable interventions and to passive control groups provided with no intervention (i.e., treatment as usual control groups and waitlist control groups). In other words, Subgroup 1 compared self-compassion intervention groups to active control groups, and Subgroup 2 compared self-compassion intervention groups to passive control groups. Additional subgroup analyses for each outcome were conducted according to the intervention delivery modes (i.e., Subgroup 1: in-person self-compassion interventions vs. control groups; Subgroup 2: online self-compassion interventions vs. control groups) and the involvement of targeted participants with psychological distress symptoms, such as depressive symptoms, anxiety, or stress, as one of the eligibility criteria for study participation (i.e., Subgroup 1: self-compassion intervention groups that targeted distressed participants vs. control groups; Subgroup 2: self-compassion intervention groups that did not target distressed participants vs. control groups), when applicable.

Results

Selection of Studies

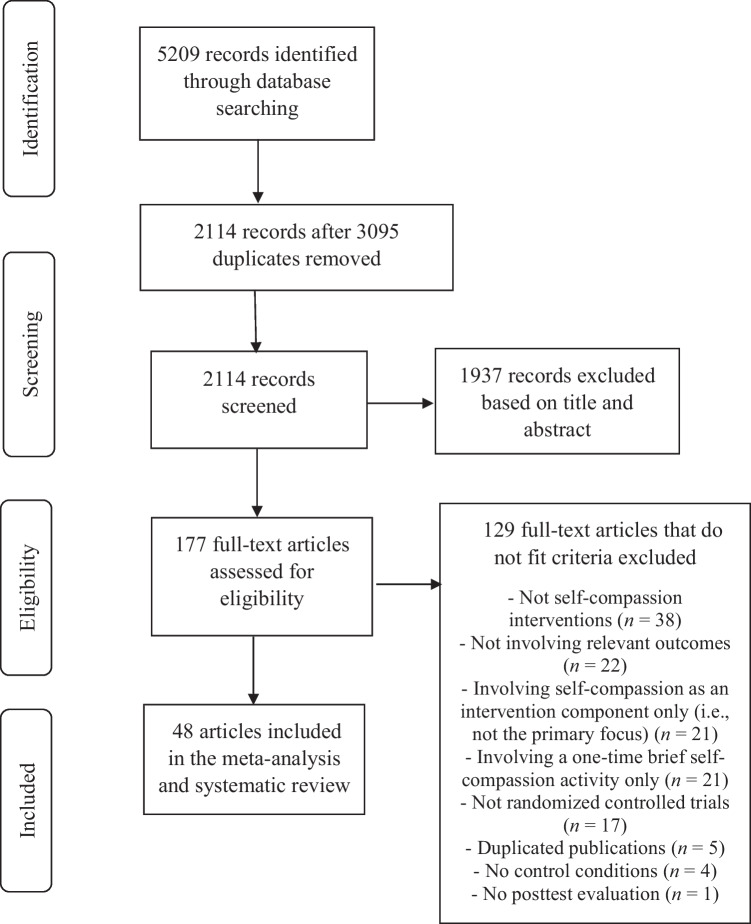

Figure 1 describes the study selection process. The initial database searches identified 5,209 articles. After removing 3,095 duplicates, 2,114 articles were screened and 1,937 were excluded based on title and abstract screening. Of the remaining articles, 177 were assessed for eligibility by reading the full text, and 129 articles were excluded for the following reasons: not a self-compassion intervention (38 articles); not involving measures of depressive symptoms, anxiety, or stress as outcomes (22 articles); involving self-compassion as an intervention component only without a core focus on self-compassion (21 articles); involving a one-time brief self-compassion activity only (21 articles); not an RCT (17 articles); duplicated publications (five articles); not involving a comparison or a control condition other than self-compassion (four articles); and not involving posttest evaluations (one article). Forty-eight studies from the initial search met the eligibility criteria, and eight studies from the second search for recent articles met the eligibility criteria. Thus, 56 studies met the eligibility criteria.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection process

Characteristics of the Included Studies

The main characteristics of the 56 included RCTs are summarized in Table 1. Self-compassion interventions were delivered as in-person interventions in 28 studies; of these, 24 studies included group-based interventions (Anuwatgasem et al., 2020; Arimitsu, 2016; Bluth et al., 2016; Boggiss et al., 2020; Collado‐Navarro et al., 2021; D'Alton et al., 2019; DeTore et al., 2022; Dundas et al., 2017; Friis et al., 2016; Haukaas et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2021; Martínez-Borrás et al., 2022; Matos et al., 2022; Neff & Germer, 2013; Noorbala et al., 2013; Sajjadi et al., 2022; Savari et al., 2021; Schuling et al., 2020; Shahar et al., 2015; Torrijos‐Zarcero et al., 2021; Weibel et al., 2017; Woodfin et al., 2021; Yadavaia et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2022) and one study delivered interventions individually (Javidi et al., 2023). Three studies did not describe whether the interventions were delivered individually or as group-based interventions (Beaumont et al., 2012; Carlyle et al., 2019; Navab et al., 2019). A total of 23 studies involved self-compassion interventions administered online; 20 of these included interventions that ran in a web browser (Beshai et al., 2020; Cândea & Szentágotai-Tătar, 2018; Eriksson et al., 2018; Fernandes et al., 2022; Gammer et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020; Hasselberg & Rönnlund, 2020; Kelly & Carter, 2015; Kelly et al., 2009; Kelman et al., 2018; Krieger et al., 2019; Lennard et al., 2021; Mifsud et al., 2021; Nadeau et al., 2021; Preuss et al., 2021; Shapira & Mongrain, 2010; Stevenson et al., 2019; Teale Sapach et al., 2023; Urken & LeCroy, 2021; Wong & Mak, 2016) and three studies administered interventions via a smartphone app (Al-Refae et al., 2021; Mak et al., 2018; Schnepper et al., 2020). Two studies involved self-compassion interventions that used self-help workbooks (Held & Owens, 2015; Sommers-Spijkerman et al., 2018). The remaining three studies involved one in-person session accompanied by another delivery mode, including one in-person session with daily practice for 2 to 3 weeks in two studies (Matos et al., 2017; Williamson, 2020) and one in-person group-based workshop with online group discussions for 2 weeks in one study (Seekis et al., 2020).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

| Reference; Country | Participants; Mean age; Female (%) | Descriptions of intervention and comparison/control groups | Relevant outcomes (measures); Data collection time points; Relevant results (between-group differences over time only) | Overall RoB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Refae et al. (2021); Canada | 165 adults who owned an iPhone (a diagnosis with a mental health disorder—25%); 25.24 years; 78.8% |

- IG: A 4-week self-compassion-based smartphone app intervention combined with cognitive restructuring training (Serene) involving psychoeducation about self-compassion, mindfulness meditations, mindful journaling and self-compassionate writing, and cognitive restructuring (i.e., identification and modification of unhelpful thoughts or beliefs and developing and applying actions plans to modify one’s behaviors) (n = 78) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 87) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D), anxiety (DASS-21-A), and stress (DASS-21-S); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in DASS-21-D and DASS-21-S over time (p < .05) | High |

| Anuwatgasem et al. (2020); Thailand | 44 adults with diagnosis of MDD; NR; NR |

- IG: 7 weekly sessions (1.5 hr per session) of group-based self-compassion-based therapy (n = 23) - CG: Standard psychotherapy group (n = 11) |

Depressive symptoms (MADRS), anxiety (HADS-A), and stress (PSS); Pretest and posttest; No significant between-group differences in outcomes over time | High |

| Arimitsu (2016); Japan | 40 individuals with low self-compassion (SCS < 17.35, which is the average score in a Japanese sample); 21.34 years; 75% |

- IG: 7 weekly sessions (1.5 hr per session) of a group-based self-compassion program involving loving-kindness meditation practice, mindfulness training, compassionate imagery skill training, compassionate letter writing, and practice of compassionate behaviors (n = 20) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 20) |

Depressive symptoms (BDI-II) and anxiety (STAI); Pretest, posttest, and 3-month F/U; CG > IG in STAI over time (p = .05) | High |

| Beaumont et al. (2012); UK | 32 people with a traumatic incident (e.g., car accidents and accidents at work); NR; NR |

- IG: 12 sessions of self-compassion training and CBT involving compassionate letter writing and use of imagery by bringing to mind a loving, accepting, and caring image (n = 16) - CG: 12 sessions of CBT covering cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, graded exposure, relapse prevention, and Socratic dialog (n = 16) |

Depressive symptoms (HADS-D) and anxiety (HADS-A); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in HADS-D over time (p < .001) | High |

| Beshai et al. (2020); USA | 456 adults with mild to moderate levels of depression, anxiety, or stress; 35.13 years; 43.9% |

- IG: 4 weekly modules of a self-guided online self-compassion intervention involving psychoeducational videos introducing concepts, audio-guided mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation practice, and self-kindness practice (e.g., Self-Compassion Break exercise) (n = 227) - CG: Watching nature videos superimposed onto relaxing meditation music for 4 weeks (watching one video per week) (n = 229) |

Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7), and stress (PSS); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in GAD-7 (p < .05) and PSS over time (p = .001) | Unclear |

| Bluth et al. (2016); USA | 34 adolescents (aged 14 to17 years) with depressive symptoms—score < 13 on a modified KADS; NR; 74% |

- IG: 6 weekly sessions (1.5 hr per session) of a mindful self-compassion adolescent program involving psychoeducation regarding self-compassion, hands-on activities and practices for self-compassion, and guided audio and video recordings of self-compassion practices for home practice (n = 16) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 18) |

Depressive symptoms (SMFQ), anxiety (STAI), and stress (PSS); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in SMFQ over time (p < .01) | Unclear |

| Boggiss et al. (2020); New Zealand | 27 adolescents (aged 12 to 16 years) with type 1 diabetes and a moderate to high instance of disordered eating behaviors as assessed by the DEPS-R; 13.9 years; 60% |

- IG: Two sessions (2.5 hr per session) of a self-compassion intervention delivered 1 week apart involving group exercises and discussions, art activities, meditations, and individual reflection exercises exploring the three components of self-compassion and self-compassion coping tools to use in everyday life when experiencing difficult emotions (n = 13) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 14) |

Stress (PSS); Pretest and posttest; No significant between-group difference in PSS over time | High |

| Cândea and Szentágotai-Tătar (2018); Romania | 136 undergraduate students with social anxiety disorder (30 ≤ LSAS-SR); 21.85 years; 88.23% |

- IG: A 2-week self-compassion online training that involved explanation of self-compassion and exercises (n = 42) - CG1: A 2-week cognitive reappraisal online training that involved explanation of reappraisal and exercises (n = 51) - CG2: Waitlist control (n = 43) |

Anxiety (LSAS-SR); Pretest and posttest; No significant between-group difference in LSAS-SR over time | High |

| Carlyle et al. (2019); UK | 38 adults (aged 22 to 62 years) who had a diagnosis of opioid use disorder and took a daily opioid substitute medication; 39.95 years; 36.84% |

- IG: 3 weekly sessions (2 hr per session) of a self-compassion training program that involved psychoeducation regarding self-compassion and self-compassion exercises (e.g., compassionate body scan and writing a compassionate letter to self and an ideal compassionate self) with guided audio recordings for home practice (n = 15) - CG1: 3 weekly sessions (2 hr per session) of a relaxation training program that involved psychoeducation regarding relaxation and relaxation exercises (e.g., belly breathing and progressive muscle relaxation) with guided audio recordings for home practice (n = 12) - CG2: Waitlist control (n = 11) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D), anxiety (DASS-21-A), and stress (DASS-21-S); Pretest and posttest; No between-group differences in outcomes over time | Unclear |

| Collado‐Navarro et al. (2021); Spain | 90 adult outpatients (aged 18 to 75 years) with mild to moderate depressive and/or anxious disorder; 46.34 years; 86.67% |

- IG: 8 weekly sessions (2 hr per session) of a group-based self-compassion program that involved psychoeducation, 30-min daily simple exercises with audio files, meditation, visualizations, and practices for self-compassion (n = 30) - CG1: 8 weekly sessions (2 hr per session) of a group-based MBSR program that involved meditation, individual and group dialogs and inquiries about perceptions and habits, and home practice (n = 30) - CG2: TAU (n = 30) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D), anxiety (DASS-21-A), and stress (DASS-21-S); Pretest, posttest, and 6-month F/U; IG & CG1 > CG2 in DASS-21 subscales over time (p < .05) | Unclear |

| D'Alton et al. (2019); Ireland | 94 adults (≥ 18 years) with mild to moderate psoriasis; 49.89 years; 55.3% |

- IG: 8 weekly sessions (2 hr per session) of a group-based mindfulness-based self-compassion program that involved guided self-compassion meditations (e.g., compassionate body scan), exercises (e.g., eyes on exercise), psychoeducation, and group discussion about the meditations and exercises with guided audio meditation recordings for daily mindfulness practice (n = 25) - CG1: 8 weekly sessions (2 hr per session) of a group-based MBCT program that involved guided mindfulness meditations, sharing experiences of these exercises, and teaching cognitive behavioral skills and techniques (e.g., cognitive defusion and recording pleasant events) with guided audio meditation recordings for daily mindfulness practice (n = 25) - CG2: TAU (n = 22) |

Depressive symptoms (HADS-D) and anxiety (HADS-A); Pretest, posttest, 6-month F/U, and 12-month F/U; No significant between group differences in outcomes over time | High |

| DeTore et al. (2022); USA | 107 undergraduate students with mild to moderate depressive symptoms; 18.82 years; 71.03% |

- IG: 4 weekly group sessions (1.5 hr per session) addressing self-compassion skill practice (e.g., self-compassion break, mindfulness exercise, self-compassion writing exercise, and self-compassion letter writing) with home practice (e.g., 3-min breathing exercise and self-compassion mindfulness exercise) (n = 54) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 53) |

Depressive symptoms (BDI) and anxiety (STAI); Pretest, posttest, and 12-month F/U; IG > CG in BDI (p < .001) and STAI over time (p < .05) | Unclear |

| Dundas et al. (2017); Norway | 158 university students; 25 years; 85% |

- IG: 3 sessions (1.5 hr per session) of a self‐compassion course delivered over 2 weeks that involved lectures, self-compassion exercises, group discussions, and experiential practices with audio guides to self-compassion exercises for daily use (n = 69) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 69) |

Depressive symptoms (MDI) and anxiety (STAI); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in MDI (p < .05) and STAI over time (p < .001) | High |

| Eriksson et al. (2018); Sweden | 101 practicing psychologists; 36.2 years; 96.04% |

- IG: A 6-week web-based mindful self-compassion program involving 15-min exercises per day, 6 days per week, for 6 weeks for self-compassion exercises with guided instructions as audio files such as loving kindness, pause for self-compassion, and body scan (10 hr in total) (n = 52) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 49) |

Stress (PSS); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in PSS over time (p < .001) | High |

| Fernandes et al. (2022); Portugal |

292 postpartum mothers (≥ 18 years) of a child (aged up to 18 months) with moderate or high levels of parenting stress; 34.03 years; 100% |

- IG: 6 weekly modules (1 hr per module) of a self-guided, web-based, mindful, and compassionate parenting training with written materials, visual elements, audio tracks, and homework tasks, addressing psychoeducational materials, formal mediation practices (e.g., breath meditation), self-compassion practices, and mindful parenting exercises (n = 146) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 146) |

Depressive symptoms (EPDS), anxiety (HADS-A), and stress (Parental Stress Scale); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in parental stress over time (p = .05) | High |

| Friis et al. (2016); New Zealand | 63 adult patients (aged 18 to 70 years) with type 1 or type 2 diabetes; 44.37 years; 68.25% |

- IG: 8 weekly sessions (2.5 hr per session) of a group-based mindful self-compassion program that involved general introduction of self-compassion, developing a compassionate inner voice, and skills practice for self-compassion and mindfulness (n = 32) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 31) |

Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) and stress (DDS); Pretest, posttest, and 3-month F/U; IG > CG in PHQ-9 (p < .05) and DDS over time (p < .001) | Unclear |

| Gammer et al. (2020); UK | 206 mothers (≥ 18 years) of infants younger than 1 year; 35.19 years; 100% |

- IG: 5 weekly sessions of a web-based self-compassion program over 5 to 6 weeks that involved 10–15 min per week for contents and a few minutes per day for exercises with a written description and an audio guide (n = 105) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 101) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D), anxiety (DASS-21-A), and stress (DASS-21-S); Pretest, posttest, and 6-week F/U; No significant between group differences in outcomes over time | Unclear |

| Guo et al. (2020); China | 314 female adults (aged 18 to 40 years) who were in the second or third trimester of pregnancy before 34 weeks and had antenatal depressive or anxiety symptoms (EPDS ≥ 9); 30.6 years; 100% |

- IG: A 6-week web-based mindful self-compassion program that involved 10 hr of training with 36 mini-sessions in total (15 min per session, 6 mini-sessions a week) and used self-compassion exercises with guided instructions (n = 157) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 157) |

Stress (PSI); baseline, 3 months, and 1 year postpartum; IG > CG in PSI over time (p < .05) | High |

| Hasselberg and Rönnlund (2020); Sweden | 56 young adults (aged 18 to 25 years); 22.3 years; 89.29% |

- IG: A 2-week web-based self-help self-compassion program (15 min of training per day, 5 days a week) that involved a prerecorded psycho-educative introduction of self-compassion and guided exercises of prerecorded video clips such as loving kindness meditation, breathing exercises, and body scan (n = 28) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 28) |

Stress (PSS); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in PSS over time (p < .01) | High |

| Haukaas et al. (2018); Norway | 81 undergraduate and graduate students (63%—mild to severe depression; 64.2%—mild to severe anxiety); 22.9 years; 75.3% |

- IG: 3 weekly sessions (45 min per session) of a group-based mindful self-compassion program that involved guided meditation and exercises designed to promote self-compassion (e.g., affectionate breathing and loving kindness meditation) provided with prerecorded audiotapes for daily practice (n = 41) - CG: 3 weekly sessions (45 min per session) of a group-based attention training program that involved a 12-min auditory exercise designed to strengthen attentional control and promote external focus of attention provided with prerecorded audiotapes for daily practice (n = 40) |

Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7); Pretest, posttest, and 6-month F/U; No significant between group differences in outcomes over time | Unclear |

| Held and Owens (2015); USA | 27 homeless male veterans who were living in transitional housing facilities; 51.3 years; 0% |

- IG: A 4‐week self‐administered self‐compassion training that involved a workbook (e.g., learning to respond compassionately to one’s own experiences and compassionate letter writing) and 5- to 15-min daily exercises (n = 13) - CG: A 4-week self-administered stress management training that involved a workbook (e.g., deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation) and 5- to 15-min daily exercises (n = 14) |

Stress (PCL-S); Pretest and posttest; CG > IG in PCL-S over time (p < .01) | Unclear |

| Huang et al. (2021); China | 69 college students; 20.55 years; 71.21% |

- IG: 4 weekly sessions (2 hr per session) of a group-based self-compassion program that involved psychoeducation about self-compassion and self-compassion skills training (e.g., affectionate breathing meditation and loving-kindness meditation) (n = 32) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 37) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D), anxiety (DASS-21-A), and stress (DASS-21-S); Pretest, posttest, and 1-month F/U; IG > CG in DASS-21-D (p < .001) and DASS-21-S over time (p < .05) | High |

| Javidi et al. (2023); Australia | 82 adults (aged 18 to 65 years) with a primary diagnosis of either a depressive disorder or PTSD; 38.75 years; 74.2% |

- IG: 12 sessions of an individual self-compassion training program combined with behavioral therapy (i.e., behavioral activation within CBT) that involved psychoeducation on three elements of self-compassion, practice taking a self-compassion break, compassionate letter writing to self, and building a self-compassionate image (n = 41) - CG: 12 sessions of an individual CBT program that involved psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and behavioral activation (n = 41) |

Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) and stress (K10); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in PHQ-9 (p < .01) and K10 over time (p < .001) | High |

| Kelly and Carter (2015); Canada | 41 adults (> 18 years) with binge eating disorder; 45 years; 82.93% |

- IG: 3 weeks of self-help self‐compassion exercises that involved an audio-guided PowerPoint slideshow for psychoeducation on development of a structured eating plan and self-compassion, practice of guided exercises (e.g., two self-compassion imagery exercises and compassionate letter writing to self), and instructions to cultivate a self-compassionate mindset through imagery, self-talk, and letter-writing over 3 weeks plus provision of a link to an online form for self-compassion practice (e.g., self-compassionate imagery visualization and compassionate letter writing to self) every evening before bed (n = 15) - CG1: 3 weeks of self-help behavioral strategies that involved an audio-guided PowerPoint slideshow for psychoeducation on development of a structured eating plan and behavioral activation, such as developing alternate activities with which to replace binge eating when urges arise and monitoring and reviewing strategies used when urges to binge arose over the 3 weeks (n = 13) - CG2: Waitlist control (n = 13) |

Depressive symptoms (CES-D); Pretest and posttest; No significant between group difference in CES-D over time | Unclear |

| Kelly et al. (2009); Canada | 75 adults (≥ 18 years) who suffered from chronic facial acne and experienced significant acne-related distress (≥ 4 on the SKINDEX-16’s emotion distress subscale); 22 years; 77.33% |

- IG: A 2-week online self-help self-soothing intervention that involved a 1-hr PowerPoint session for the rationale, instructions, and exercises for self-compassionate imagery and self-talk (e.g., visualizing a self-compassionate image, writing a self-compassionate letter, and developing self-compassionate phrases) with daily self-help exercises for 2 weeks (e.g., repeating their compassionate self-statements three times per day while engaging in compassionate imagery) (n = 23) - CG1: A 2-week online attack-resisting intervention that involved a 1-hr PowerPoint session for the rationale, instructions, and exercises for resilient and retaliating imagery and self-talk exercise with daily self-help exercises for 2 weeks (n = 26) - CG2: TAU (n = 24) |

Depressive symptoms (BDI) and stress (SKINDEX-16); Pretest and posttest; CG1 > CG2 in BDI (p < .01), IG and CG1 > CG2 in SKINDEX-16 over time (p < .01) | Unclear |

| Kelman et al. (2018); USA & India | 84 women (≥ 18 years) who were pregnant, became pregnant within the last year, and intend to become pregnant in the future (aged 18 to 54 years); NR; 100% |

- IG: A 2-week internet-based compassionate mind training that involved a 45‐min didactic course that introduced the course materials and audio meditations delivered by email three times over the 2-week period (e.g., finding ourselves here in the flow of life and cultivating the compassionate self) (n = 41) - CG: A 2-week internet-based CBT that involved a 45‐min didactic course that introduced the course materials (i.e., thoughts, activities, assertiveness, and sleep) and exercises for CBT delivered by email three times over the 2-week period (n = 43) |

Depressive symptoms (Depression subscale of the PHQ-4) and anxiety (Anxiety subscale of the PHQ-4); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in outcomes over time (p < .05) | High |

| Krieger et al. (2019); Switzerland | 122 adults (≥ 18 years) with increased levels of self-criticism (≥ 20 on the inadequate self subscale of the FSCRS; 37.69 years; 77.69% |

- IG: 7 weekly modules (1 hr per module) of internet-delivered self-help self-compassion training (texts, audio files, and a diary function) that covered descriptions of self-compassion (e.g., common humanity, self-criticism vs. self-kindness, and over-identification vs. mindfulness) and exercises (e.g., mindfulness exercises, loving-kindness meditation, and self-compassionate writing) (n = 60) - CG: TAU (n = 62) |

Stress (DASS-21); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in DASS-21 over time (p < .01) | Unclear |

| Lennard et al. (2021); Australia | 248 mothers (≥ 18 years) of infants (< 2 years); 32.56 years; 100% |

- IG: An 8-week online self-compassion intervention that involved two videos covering psychoeducation about self-compassion in the context of motherhood and a guided self‐compassion visualization exercise with a downloadable tip sheet offering ideas for becoming more self‐compassionate and SMS reminders (n = 94) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 154) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D), anxiety (DASS-21-A), and stress (DASS-21-S); Pretest and posttest; No significant between-group differences in outcomes over time | High |

| Mak et al. (2018); Hong Kong | 2161 adults (> 18 years) who owned a mobile device and had consistent internet access; 33.64 years; 72.88% |

- IG: 4 weekly modules (28 daily sessions, 10–15 min daily) of a mobile app–based self-compassion program that involved reading and graphic contents and audio-guided self-compassion exercises (e.g., compassionate body scan, affectionate breathing, loving-kindness meditation, compassionate walking, soften-allow-soothe, self-compassion break, and self-compassion journaling) (n = 705) - CG1: 4 weekly modules (28 daily sessions, 10–15 min daily) of a mobile app–based cognitive behavioral psychoeducation program that involved problem-solving skills, emotional management skills, cognitive strategies to tackle automatic negative thoughts associated with stress, audio-guided relaxation skills training (e.g., progressive muscle relaxation and imagery relaxation), and information and graphics about mental health, stress, and cognitive behavioral approach for mental health (n = 753) - CG2: 4 weekly modules (28 daily sessions, 10–15 min daily) of a mobile app–based mindfulness program that involved audio-guided mindfulness exercises (e.g., body scan, mindful breathing, mindful eating, mindful walking, and thought-distancing exercise) and readings and graphics to explain concepts of mindfulness (n = 703) |

Stress (K6); pretest, posttest, and 3-month F/U; No significant between group difference in K6 over time | High |

| Martínez-Borrás et al. (2022); Spain | 40 employees of an automotive company; 41.93 years; 37.5% |

- IG: 6 weekly in-person sessions (12 hr in total) of a group-based workplace mindfulness- and self-compassion-based intervention, involving meditation practices and psychoeducation to foster mindfulness and self-compassion to cope with work-related stress (n = 20) - CG: A 6-week, 3-session, in-person group-based workplace stress management program involving psychoeducation regarding work-related stress and coping strategies (n = 20) |

Stress (PSQ); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in PSQ over time (p < .05) | High |

| Matos et al. (2017); Portugal | 93 adults, including college students (78.5%); 23.34 years; 90.3% |

- IG: A 2-week self-compassion program involving a 2-hr group session introducing concepts of self-compassion and compassionate mind training practices and audio files for 2-week independent practice (e.g., an imagery practice to develop a compassionate image of another mind that has caring intent toward the self) (n = 56) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 37) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D), anxiety (DASS-21-A), and stress (DASS-21-S); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in DASS-21-S over time (p < .05) | High |

| Matos et al. (2022); Portugal | 155 public school teachers; 51.35 years; 92.9% |

- IG: 8 weekly sessions (2.5 hr per session) of a group-based compassionate mind training program for teachers aiming to cultivate a compassionate self by using psychoeducation and self-compassion practices (e.g., cultivating the ideal compassionate self, self-compassion break, and mindful breathing) (n = 80) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 75) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D), anxiety (DASS-21-A), and stress (DASS-21-S); Pretest, posttest, and 3-month F/U; No significant between group differences in outcomes over time | High |

| Mifsud et al. (2021); Australia | 79 breast cancer survivors (≥ 18 years) who reported at least one negative event related to the changes that occurred to their body after breast cancer; 58.6 years; 100% |

- IG: A 3-week web-based self-compassion training that included a 30-min self-compassion focused writing activity (e.g., writing a self-compassionate letter to self) to address three components of self-compassion and listening to a 5-min self-compassion based audio meditation each day for 3 weeks with a daily SMS reminder (n = 17) - CG1: A web-based 30-min expressive writing activity about a challenging body image experience, including event details, thoughts, and feelings (n = 23) - CG2: A web-based 30-min self-compassion focused writing activity, including writing a self-compassionate letter to self, to address three components of self-compassion (n = 39) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D), anxiety (DASS-21-A), and stress (DASS-21-S); Pretest and posttest; No significant between group differences in outcomes over time | Low |

| Nadeau et al. (2021); USA | 57 women; 38.12 years; 100% |

- IG: A 10-week online self‐guided self-compassion course that involved video-recorded psychoeducational lectures, an interview with a prominent expert in the field, guided experiential exercises, case interviews, and homework (n = 25) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 32) |

Depressive symptoms (CES-D) and anxiety (GAD-7); Pretest, posttest, and 1-month F/U; No significant between group differences in outcomes over time | High |

| Navab et al. (2019); Iran | 20 mothers (aged 20 to 40 years) of children with ADHD; 30.65 years; 100% |

- IG: 8 weekly sessions (1.5 hr per session) of a self-compassion-based program that included understanding the differences between self-compassion and self-pity, mindfulness training, developing warmth and kindness toward oneself, practicing affectionate self-image, and writing a self-compassionate letter (n = 10) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 10) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D), anxiety (DASS-21-A), and stress (DASS-21-S); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in DASS-21-D and DASS-21-A over time (p ≤ .01) | High |

| Neff and Germer (2013); USA | 51 adults (77% with a graduate degree; 76% with prior meditation experience); 50.16 years; 80% |

- IG: 8 weekly sessions (2 hr per session) of a group-based mindful self-compassion program that involved an introduction to self-compassion and mindfulness, application of self-compassion in daily life, development of a compassionate inner voice, the importance of value-focused living, skills training for difficult emotions and challenging relationships, and how to relate to positive aspects of oneself and one’s life with appreciation, with a half-day retreat for mindfulness training between session 4 and 5 (n = 24) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 27) |

Depressive symptoms (BDI), anxiety (STAI), and stress (PSS); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in BDI and STAI (p < .01) and in PSS over time (p < .05) | High |

| Noorbala et al. (2013); Iran | 19 female adults (aged between 20 and 40 years) with diagnosis of MDD and BDI ≥ 20; 28.15 years; 100% |

- IG: 12 sessions (2 hr per session, two sessions per week) of a group-based mindful self-compassion training delivered for 6 weeks that involved introducing concepts of self-compassion, exploring the way they thought about themselves and how they behave toward themselves, and exercises (e.g., compassionate imagery, soothing breathing rhythm, mindfulness, and compassionate letter writing) (n = 9) - CG: TAU (n = 10) |

Depressive symptoms (BDI-II) and anxiety (AS); pretest, posttest, and 2-month F/U; IG > CG in outcomes over time (p < .05) | High |

| Preuss et al. (2021); Germany | 217 parents (≥ 18 years) of at least one child aged 3 to 18 years who had mild depression and stress based on DASS-21 at baseline; 40.63 years; 92.6% |

- IG: Two online video sessions (a 20-min video session on Day 1 and a 10-min video session on Day 3) of a self-compassion program that involved psychoeducation about possible psychological consequences of pandemic restrictions and the practice of mindfulness (i.e., by naming their burdening emotions and acknowledging their suffering and distress), common humanity (i.e., by internalizing this stressful family moment as a shared human experience of suffering during the pandemic), and self-kindness (i.e., by expressing a kind, warm, and soothing self-talk while strengthening their self-esteem in the parental role), with three email reminders to transfer the application of strategies to daily family life (Days 2, 4, 5) (n = 75) - CG1: Two online video sessions (same length and format as the IG) of a cognitive reappraisal program that involved psychoeducation and practice of cognitive restructuring techniques, with three email reminders to transfer the application of strategies to daily family life (Days 2, 4, 5) (n = 73) - CG2: Waitlist control (n = 69) |

Stress (PSS); Pretest and posttest (1 week); IG and CG1 > CG2 in PSS over time (p < .001) | High |

| Sajjadi et al. (2022); Iran | 47 young adults (aged between 18 to 25 years) with a history of childhood maltreatment; NR; 57% |

- IG: 8 weekly sessions (2 hr per session) of a group-based mindful self-compassion program covering the definition of self-compassion and mindfulness with practices (e.g., soothing touch, affectionate breathing, and compassionate letter to myself) (n = 24) - CG: TAU (n = 23) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D), anxiety (DASS-21-A), and stress (DASS-21-S); Pretest, posttest, and 2-month F/U; IG > CG in outcomes over time (p < .01) | Unclear |

| Savari et al. (2021); Iran | 30 female students (aged between 20 and 30 years) with a diagnosis of major depression confirmed by the SCID-I for DSM-V and by scores at least in the moderate range on the BDI-II total score (> 20); 24.3 years; 100% |

- IG: 8 sessions (1.5 hr per session, twice a week) of a group-based self-compassion program that involved psychoeducation about self-compassion, practice of self-compassion exercises (e.g., compassionate self-imagery and compassionate letter writing), and homework assignments (n = 15) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 15) |

Depressive symptoms (BDI-II); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in BDI-II over time (p < .01) | Unclear |

| Schnepper et al. (2020); Austria and Germany | 57 people who wanted to lose weight or develop a healthier eating behavior; 29 years; 84.21% |

- IG: A 14-day self-compassion mobile app intervention that involved daily notifications for daily self-compassion exercises (e.g., compassionate breathing exercises, soothing touch, writing a self-compassionate letter, and journaling exercises) (n = 28) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 29) |

Stress (PSS); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in PSS over time (p < .05) | High |

| Schuling et al. (2020); the Netherlands | 122 adults (≥ 18 years) who had been diagnosed with recurrent depressive disorder and had previously participated in an MBCT course (≥ 4 sessions, at least 1 year prior to this study); 55.6 years; 74.6% |

- IG: 8 sessions (2.5 hr per session, once every 2 weeks) of a group-based MBCL program that involved self-compassion exercises (e.g., compassionate breathing space, compassionate body scan, and soften-soothe-allow: compassion for self), group inquiry, didactic and interactive teaching, and CDs provided for 30-min daily home practice (n = 61) - CG: TAU (n = 61) |

Depressive symptoms (BDI-II); Pretest and posttest (at 4 months after pretest); IG > CG in BDI-II over time (p < .05) | High |

| Seekis et al. (2020); Australia | 76 undergraduate women with high levels of body concerns (≥ 12 on the DT and ≥ 19 on the Body Dissatisfaction Subscale from the EDI-3); 18.04 years; 100% |

- IG: A 50-min in-person group-based mindful self-compassion workshop (i.e., psychoeducation on self-compassion, two brief writing exercise for a self-compassionate mindset, and practice of compassionate body scan) and a 2-week online group discussion (i.e., use of self-compassion techniques when experiencing appearance distress and posting about their experiences on a private Facebook group three times per week for 2 weeks) (n = 42) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 34) |

Anxiety (SAAS); Pretest, posttest, 1-month F/U, and 3-month F/U; No significant between group difference in SAAS over time | Unclear |

| Shahar et al. (2015); Israel | 38 adults (aged 18 to 65 years) with high levels of self-criticism (≥ 30 on the SCP subscale of the DAS); 30.62 years; 60.53% |

- IG: 7 weekly sessions (1.5 hr per session) of a group-based loving‐kindness meditation program involving self-compassion practices and group discussions and provision of CDs of guided meditations for daily home practice (n = 19) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 19) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D), anxiety (DASS-21-A), and stress (DASS-21-S); Pretest, posttest, and 3-month F/U; IG > CG in DASS-21-D over time (p < .05) | Unclear |

| Shapira and Mongrain (2010); Canada | 1002 adults (aged 18 to 72 years) who had moderate levels of depressive symptoms as measured by the CES-D; 34 years, 81.54% |

- IG: 1-week online daily exercises for self-compassion that involved thinking about a distressing event that occurred that day and writing a self-compassionate letter (n = 63) - CG1: 1-week online daily exercises for optimistic thinking that involved visualizing and writing a letter about a future in which current issues were resolved and giving themselves advice on how to get there (n = 55) - CG2: writing freely about an early memory daily online for 1 week (n = 70) |

Depressive symptoms (CES-D); Pretest, posttest, 1-month F/U, 3-month F/U, and 6-month F/U; IG and CG1 > CG2 in CES-D over time (p < .05) | High |

| Sommers-Spijkerman et al. (2018); the Netherlands | 242 adults (≥ 18 years) with low to moderate levels of well-being, as determined by the MHC-SF; 52.87 years; 74.8 |

- IG: 7 weekly modules of a guided self-help compassion program with self-compassion as the primary focus over a 9-week period that involved psychoeducational information on an important aspect of self-compassion and experiential exercises with audio guided recordings (e.g., mindful breathing, keeping a diary of self-critical thoughts, and visualizing one’s ideal compassionate self) with weekly email guidance (n = 120) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 122) |

Depressive symptoms (HADS-D), anxiety (HADS-A), and stress (PSS); Pretest, posttest, and 3-month F/U; IG > CG in outcomes over time (p < .001) | Unclear |

| Stevenson et al. (2019); Australia | 119 adults (≥ 18 years) with elevated levels of social anxiety (≥ 19 on the SPIN); 29.04 years; 76.5% |

- IG: A 14-day online daily self-compassion exercise program that included writing a self-compassionate letter (n = 60) - CG: A 14-day online daily cognitive restructuring program that included identifying a recent social situation causing social anxiety, negative automatic thoughts experienced during or after the situation evidence, and an alternative evaluation of the situation (n = 59) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D) and anxiety (SPS); Pretest, posttest, 1-week F/U, and 5-week F/U; No significant between group differences in outcomes over time | Unclear |

| Teale Sapach et al. (2023); Canada | 59 adults (≥ 18 years) with a primary diagnosis of social anxiety disorder; 34.3 years; 67.8% |

- IG: 6 weekly sessions of a web-based, audio-guided self-compassion training program that covered psychoeducation about self-compassion and self-compassion practice exercises (n = 20) - CG1: 6 weekly sessions of a text-based self-guided applied relaxation training that covered progressive muscle relaxation, cue-controlled relaxation, rapid relaxation, and applied relaxation in anxiety-provoking situations (n = 19) - CG2: Waitlist control (n = 20) |

Anxiety (LSAS-SR); Pretest, posttest, and 3 month F/U; IG > CG2 in LSAS-SR over time (p < .05) & IG = CG1 | High |

| Torrijos‐Zarcero et al. (2021); Spain | 123 adults (≥ 18 years) with chronic pain who had a score ≥ 8 on the HADS-A and/or HADS-D and was diagnosed with adjustment disorder, dysthymia or MDD according to the DSM-V; 48.76 years; 87.8% |

- IG: 8 weekly sessions (2.5 hr per session) of a group-based mindful self‐compassion program that involved psychoeducation on self-compassion and self-compassion practices (e.g., affectionate breathing, loving-kindness meditation, self-compassionate letter writing, and self-appreciation exercise) (n = 62) - CG: 8 weekly sessions (2.5 hr per session) of group-based CBT that involved psychoeducation about chronic pain and the relationship among thoughts, emotions, and physical reactions; relaxation and breathing techniques; cognitive restructuring; behavioral activation; and paced physical activity to prevent pain (n = 61) |

Depressive symptoms (HADS-D) and anxiety (HADS-A); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in HADS-A over time (p < .05) | High |

| Urken and LeCroy (2021); USA | 203 English-speaking adults (≥ 18 years) with a diagnosis of mental disorders (i.e., MDD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder)—85% MDD; 34.59 years; 72.9% |

- IG: A 3-day online self-compassion writing intervention that involved writing with self-compassion prompts focused on three components of self-compassion (i.e., mindfulness, common humanity, and self-kindness) daily for 15 min for 3 days (e.g., writing a self-compassionate letter) (n = 101) - CG: Writing about how they spent their time leaving out emotions with writing prompts daily for 3 days online (n = 102) |

Depressive symptoms (RDQ); Pretest, posttest (after the 3-day intervention), and 1-month F/U; No significant between group difference in RDQ over time | High |

| Weibel et al. (2017); USA | 71 undergraduate students; 19.1 years; 77% |

- IG: 4 weekly sessions (1.5 hr per session) of a group-based loving-kindness meditation program that included psychoeducation, loving-kindness meditation practice, and group discussion (n = 38) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 33) |

Anxiety (STAI); Pretest, posttest, and 8-week F/U; No significant between group difference in STAI over time | High |

| Williamson (2020); USA | 129 students; 19.43 years; 69.77% |

- IG: One in-person self-compassion training session (i.e., psychoeducation about self-compassion and interactive exercises involving scenarios) and 10-min daily practice of self-compassion for 3 weeks (e.g., engaging in positive, soothing, self-compassionate self-talk in stressful situations, mindfulness practice, and practicing self-kindness by saying words of comfort to themselves) (n = 44) - CG1: Time management that involved one in-person meeting and time management practice for 3 weeks (i.e., creating to-do lists of tasks and writing down completed tasks in their activity log and a brief description of how they felt about completing the task) (n = 47) - CG2: TAU (n = 38) |

Depressive symptoms (ZSDS) and stress (PSS); Pretest and posttest; No significant between group differences in outcomes over time | High |

| Wong and Mak (2016); Hong Kong | 65 university students; 20.5 years; 53.85% |

- IG: Web-based self-compassion writing on 3 consecutive days that involved writing about a recent painful/negative event or any time that they had judged themselves, and then using an accepting and self-compassionate attitude to process the experience provided with three self-compassion prompts (n = 33) - CG: Web-based control writing according to the instruction on 3 consecutive days that involved writing about daily activities in a factual and unemotional manner (n = 32) |

Depressive symptoms (CES-D); Pretest, posttest (1 month F/U), and 3-month F/U; No significant between group difference in CES-D over time | High |

| Woodfin et al., 2021); Norway | 89 university students; 27 years; 78.4% |

- IG: A 3-week group-based self-compassion program that involved 4 weekly seminars (3 hr per seminar) and a silent retreat (4 hr) and that covered short lectures regarding self-compassion, short guided self-compassion and mindfulness exercises (e.g., affectionate breathing, self-compassion break, and loving-kindness for ourselves), and group discussions (n = NR) - CG: Waitlist control (n = NR) |

Depressive symptoms (MDI) and anxiety (STAI); Pretest and posttest; IG > CG in outcomes over time (p < .01) | High |

| Yadavaia et al. (2014); USA | 73 undergraduate students (≥ 18 years) who had low self-compassion (a score on the SCS below the mean score for undergraduates) and high psychological distress (≥ 10 on the GHQ); 20.37 years; 74% |

- IG: A 6-hr ACT-based workshop targeting self-compassion that focused on weakening fusion with self-criticism and self-conceptualizations, building self-perspective-taking and self-as-context, and strengthening a value of self-kindness through self-acceptance with experiential exercises for self-compassion (n = 30) - CG: Waitlist control (n = 43) |

Depressive symptoms (DASS-21-D), anxiety (DASS-21-A), and stress (DASS-21-S); Pretest, posttest (at 1 or 2 weeks), and 2-month F/U; IG > CG in DASS-21-D and DASS-21-A over time (p < .05) | Unclear |

| Zheng et al. (2022); China | 40 adult (≥ 18 years) with nonspecific chronic low back pain; 35.2 years; 75.7% |

- IG: A 4-week self-compassion training, which involved 4 in-person group sessions (2 hr per session) with home practice for psychoeducation about self-compassion and guided self-compassion practices (e.g., affectionate breathing meditation, self-compassion touch, self-compassion writing, and loving kindness meditation for ourselves), combined with core stability exercise (the same exercise condition of CG) (n = 20) - CG: A 4-week core stability exercise program that involved 4 weekly in-person sessions (1.5 hr per session), self-help exercise at home (30–40 min per session, at least 3 times per week), and completion of an electronic daily training diary (n = 20) |

Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7); Pretest, posttest, and 3-month F/U; IG > CG in GAD-7 over time (p < .05) | Low |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AS, Anxiety Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CG, comparison or control group; DAS, Dysfunctional Attitude Scale; DASS-21-A, Anxiety Subscale of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale—21 Items; DASS-21-D, Depression Subscale of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale—21 Items; DASS-21-S, Stress Subscale of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale—21 Items; DDS, Diabetes Distress Scale; DEPS-R, Diabetes Eating Problem Survey Revised; DSM-V, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; DT, Drive for Thinness Scale; EDI-3, Eating Disorder Inventory-3; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; FSCRS, Forms of Self- Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale; F/U, follow-up; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; HADS-A, Anxiety Subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HADS-D, Depression Subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IG, intervention group; KADS, Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale; K6, 6-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; K10, 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; LSAS-SR, Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale—Self-Report Version; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MBCL, mindfulness-based compassionate living; MBCT, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; MBSR, mindfulness‐based stress reduction; MDD, major depressive disorder; MDI, Major Depression Inventory; MHC-SF, Mental Health Continuum-Short Form; NR, not reported; PCL-S, PTSD Checklist–Specific Stressor Version; PHQ-4, Patient Health Questionnaire – 4; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire – 9; PSI, Parenting Stress Index; PSQ, Perceived Stress Questionnaire; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RDQ, Remission from Depression Questionnaire; RoB: risk of bias; SAAS, Social Appearance Anxiety Scale; SCID-I, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Axis I Disorders; SCP, self-critical perfectionism; SCS, Self-Compassion Scale; SMFQ, Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; SMS, Short Message Service; SPIN, Social Phobia Inventory; SPS, Social Phobia Scale; STAI, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; TAU, treatment as usual; ZSDS; Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale

Self-compassion interventions were delivered over an average of 5.1 weeks (SD = 3.2), ranging from 1 to 16 weeks. Self-compassion interventions of the included studies typically involved: psychoeducation about self-compassion and its three components (i.e., self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness); mindfulness practice (e.g., compassionate body scan); self-compassionate letter writing (i.e., writing a compassionate letter to self); visualizing a self-compassionate image (e.g., an imagery practice to develop a compassionate image of another mind that has caring intent toward the self); and daily self-compassion practice with audio guided recordings.

The average sample size for participants in the included RCTs was 156 (SD = 310), ranging from 19 to 2,161. The mean age of participants was 33.3 years (SD = 11.4), ranging from 13.9 years to 58.6 years. Two studies involved adolescents only (Bluth et al., 2016; Boggiss et al., 2020) while the remaining 54 studies involved adult populations. The average percentage of female participants was 77.8% (SD = 19.4), ranging from 0 to 100%. A total of 11 studies involved female participants only (Fernandes et al., 2022; Gammer et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020; Kelman et al., 2018; Lennard et al., 2021; Mifsud et al., 2021; Nadeau et al., 2021; Navab et al., 2019; Noorbala et al., 2013; Savari et al., 2021; Seekis et al., 2020) while one study involved male participants only (Held & Owens, 2015). Of the 56 studies, 20 studies directly targeted people who reported psychological distress symptoms, such as depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress (Anuwatgasem et al., 2020; Beshai et al., 2020; Bluth et al., 2016; Cândea & Szentágotai-Tătar, 2018; Collado‐Navarro et al., 2021; DeTore et al., 2022; Fernandes et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2020; Javidi et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2009; Noorbala et al., 2013; Preuss et al., 2021; Savari et al., 2021; Schuling et al., 2020; Shapira & Mongrain, 2010; Stevenson et al., 2019; Teale Sapach et al., 2023; Torrijos‐Zarcero et al., 2021; Urken & LeCroy, 2021; Yadavaia et al., 2014). Two studies directly targeted individuals with low levels of self-compassion (Arimitsu, 2016; Yadavaia et al., 2014), and two studies directly targeted adults with high levels of self-criticism (Krieger et al., 2019; Shahar et al., 2015).

Thirty-one studies involved passive control groups with no intervention only, 16 involved active control groups provided with other comparable interventions only, and the remaining nine studies involved both active control groups and passive control groups. The included RCTs were conducted in the USA (11 studies), Australia (five studies), Canada (five studies), China (five studies), Iran (four studies), the UK (three studies), Norway (three studies), Spain (three studies), Portugal (three studies), New Zealand (two studies), the Netherlands (two studies), Sweden (two studies), Germany (two studies), Switzerland (one study), Ireland (one study), Romania (one study), Israel (one study), Japan (one study), and Thailand (one study). Six studies were published between 2009 and 2014, 10 studies were published between 2015 and 2017, and 40 studies were published between 2018 and January, 2023.

The following section describes results of meta-analysis regarding the effects of self-compassion interventions on depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress at the immediate posttest and follow-up, with findings of subgroup analyses grouped according to the type of control groups (i.e., Subgroup 1: self-compassion intervention groups vs. active control groups; Subgroup 2: self-compassion intervention groups vs. passive control groups), when applicable.

Effects of Self-Compassion Interventions on Reducing Depressive Symptoms

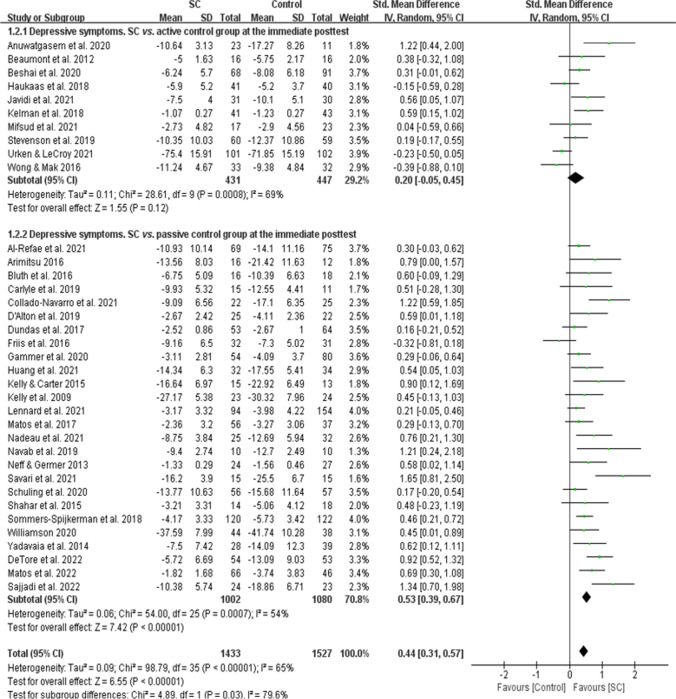

A meta-analysis of 36 RCTs (N = 2,960 participants) showed self-compassion interventions had a medium effect on reducing depressive symptoms at the immediate posttest compared to control groups overall (SMD = 0.44, 95% CI = [0.31, 0.57]; Fig. 2). There was a significant subgroup difference at the immediate posttest (Chi2 = 4.89, p = 0.03), indicating the effects of the two subgroups (i.e., Subgroup 1: self-compassion intervention groups vs. active control groups; Subgroup 2: self-compassion intervention groups vs. passive control groups) at the immediate posttest were statistically different from one another. Self-compassion interventions had a medium effect compared to passive control groups at the immediate posttest (26 RCTs, N = 2,082 participants; SMD = 0.53, 95% CI = [0.39, 0.67]) while self-compassion interventions were not different from active control groups (10 RCTs, 878 participants; SMD = 0.20, 95% CI = [-0.05, 0.45]).

Fig. 2.

A forest plot showing the effects of self-compassion interventions on depressive symptoms at the immediate posttest

A meta-analysis of 14 RCTs with follow-up data (N = 1,261 participants) revealed self-compassion interventions had a small effect on reducing depressive symptoms at follow-up compared to control groups overall (SMD = 0.38, 95% CI = [0.14, 0.61]; Fig. 3). There was a significant subgroup difference at follow-up (Chi2 = 14.10, p < 0.001), indicating the effects of the two subgroups (i.e., Subgroup 1: self-compassion intervention groups vs. active control groups; Subgroup 2: self-compassion intervention groups vs. passive control groups) at follow-up were statistically different from one another. Self-compassion interventions had a medium effect compared to passive control groups at follow-up (10 RCTs, N = 793 participants; SMD = 0.58, 95% CI = [0.37, 0.79]), but self-compassion interventions were not different from active control groups (four RCTs, N = 468 participants; SMD = -0.12, 95% CI = [-0.42, 0.18]).

Fig. 3.

A forest plot showing the effects of self-compassion interventions on depressive symptoms at follow-up

Effects of Self-Compassion Interventions on Reducing Anxiety

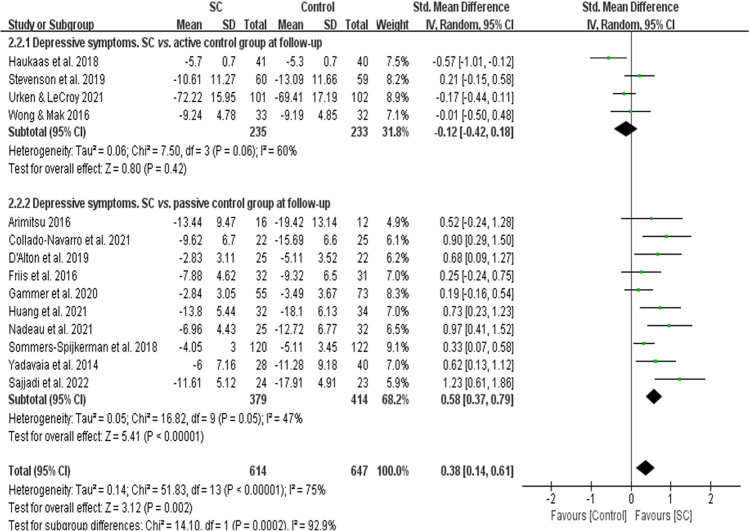

A meta-analysis of 31 RCTs (N = 2,508 participants) revealed self-compassion interventions had a small effect on reducing anxiety at the immediate posttest compared to control groups overall (SMD = 0.36, 95% CI = [0.16, 0.55]; Fig. 4). There was no significant subgroup difference at the immediate posttest (Chi2 = 2.26, p = 0.13), indicating the effects of the two subgroups (i.e., Subgroup 1: self-compassion intervention groups vs. active control groups; Subgroup 2: self-compassion intervention groups vs. passive control groups) at the immediate posttest were not statistically different from one another. Self-compassion interventions had a medium effect compared to passive control groups at the immediate posttest (22 RCTs, N = 1,898 participants; SMD = 0.46, 95% CI = [0.29, 0.64]) while self-compassion interventions were not different from active control groups (nine RCTs, 610 participants; SMD = 0.01, 95% CI = [-0.54, 0.57]).

Fig. 4.

A forest plot showing the effects of self-compassion interventions on anxiety at the immediate posttest

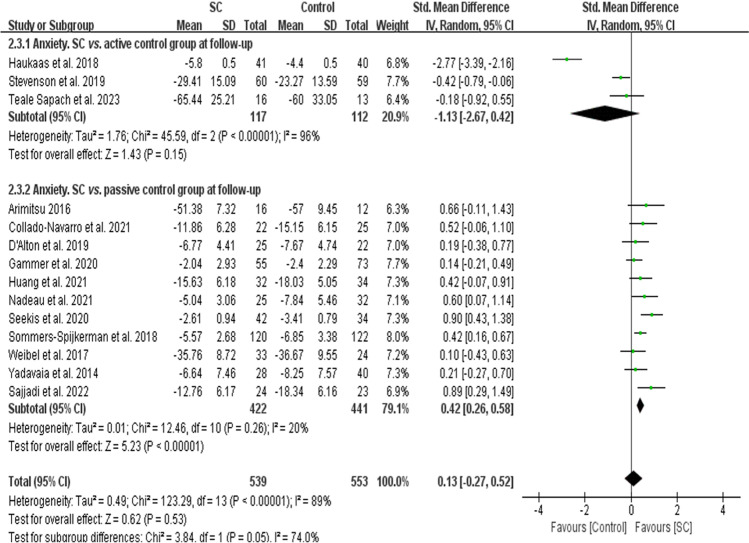

A meta-analysis of 14 RCTs with follow-up data (N = 1,092 participants) showed self-compassion interventions were not significantly different from control groups overall in reducing anxiety at follow-up (SMD = 0.13, 95% CI = [-0.27, 0.52]; Fig. 5). There was a significant subgroup difference at follow-up (Chi2 = 3.84, p = 0.05), indicating the effects of the two subgroups (i.e., Subgroup 1: self-compassion intervention groups vs. active control groups; Subgroup 2: self-compassion intervention groups vs. passive control groups) at follow-up were statistically different from one another. While self-compassion interventions were not different from active control groups at follow-up (three RCTs, N = 229 participants; SMD = -1.13, 95% CI = [-2.67, 0.42]), self-compassion interventions had a medium effect compared to passive control groups at follow-up (11 RCTs, N = 863 participants; SMD = 0.42, 95% CI = [0.26, 0.58]).

Fig. 5.

A forest plot showing the effects of self-compassion interventions on anxiety at followup

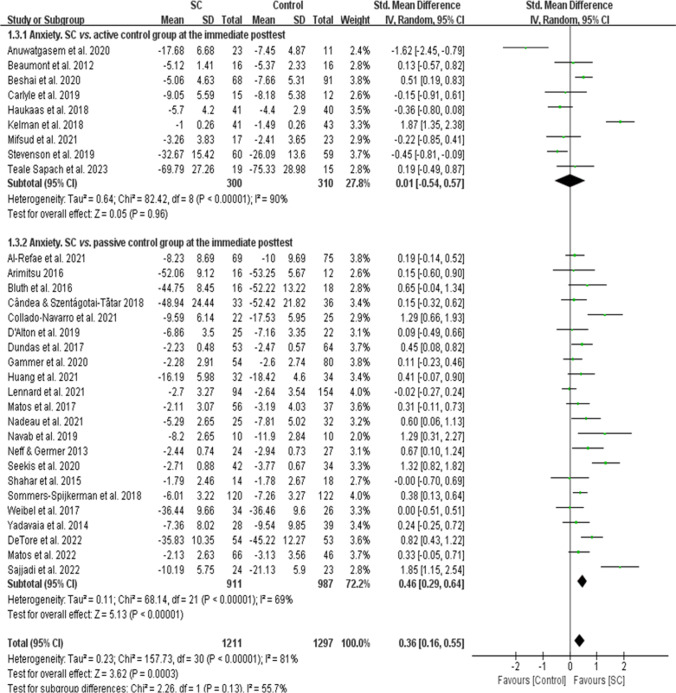

Effects of Self-Compassion Interventions on Reducing Stress

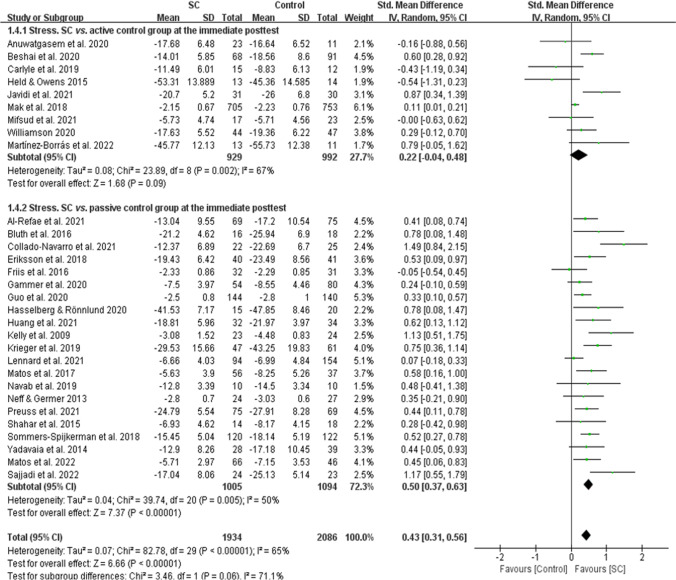

A meta-analysis of 30 RCTs (N = 4,020 participants) showed self-compassion interventions had a medium effect on reducing stress at the immediate posttest compared to control groups overall (SMD = 0.43, 95% CI = [0.31, 0.56]; Fig. 6). There was no significant subgroup difference at the immediate posttest (Chi2 = 3.46, p = 0.06), indicating the effects of the two subgroups (i.e., Subgroup 1: self-compassion intervention groups vs. active control groups; Subgroup 2: self-compassion intervention groups vs. passive control groups) at the immediate posttest were not statistically different from one another. Self-compassion interventions had a medium effect compared to passive control groups at the immediate posttest (21 RCTs, N = 2,099 participants; SMD = 0.50, 95% CI = [0.37, 0.63]) while self-compassion interventions were not different from active control groups (nine RCTs, 1,921 participants; SMD = 0.22, 95% CI = [-0.04, 0.48]).

Fig. 6.

A forest plot showing the effects of self-compassion interventions on stress at the immediate posttest

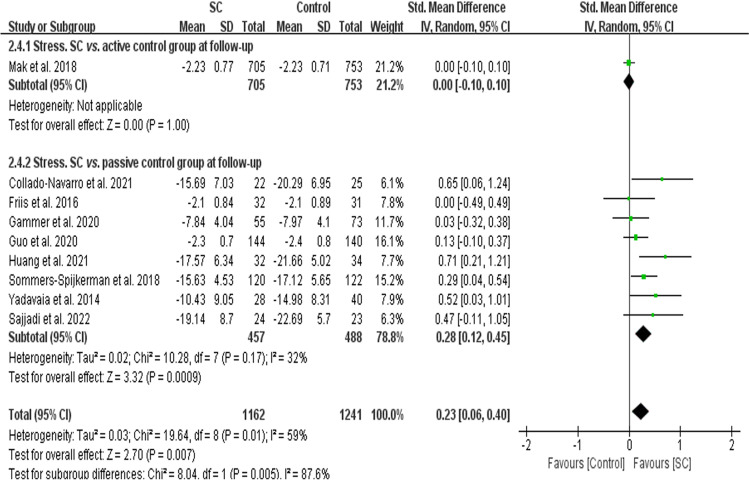

A meta-analysis of nine RCTs with follow-up data (N = 2,403 participants) revealed self-compassion interventions had a small effect on reducing stress at follow-up compared to control groups overall (SMD = 0.23, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.40]; Fig. 7). There was a significant subgroup difference at follow-up (Chi2 = 8.04, p = 0.005), indicating the effects of the two subgroups (i.e., Subgroup 1: self-compassion intervention groups vs. active control groups; Subgroup 2: self-compassion intervention groups vs. passive control groups) at follow-up were statistically different from one another. Self-compassion interventions had a small effect compared to passive control groups at follow-up (eight RCTs, N = 945 participants; SMD = 0.28, 95% CI = [0.12, 0.45]), but self-compassion interventions were not different from active control groups (one RCT, N = 1,458 participants; SMD = 0.00, 95% CI = [-0.10, 0.10]).

Fig. 7.

A forest plot showing the effects of self-compassion interventions on stress at followup

Subgroup Analyses According to the Intervention Delivery Modes

In-person self-compassion interventions showed medium effects on reducing depressive symptoms at the immediate posttest (23 studies that involved 1,390 participants, SMD = 0.57, 95% CI = [0.39, 0.75]) and at follow-up (eight studies that involved 447 participants, SMD = 0.53, 95% CI = [0.12, 0.94]), reducing anxiety at the immediate posttest (20 studies that involved 1,178 participants, SMD = 0.40, 95% CI = [0.13, 0.66]), and reducing stress at the immediate posttest (16 studies that involved 869 participants, SMD = 0.50, 95% CI = [0.29, 0.71]) and at follow-up (five studies that involved 291 participants, SMD = 0.46, 95% CI = [0.20, 0.72]). There was no statistically significant difference of in-person self-compassion interventions from control groups in reducing anxiety at follow-up (nine studies that involved 517 participants, SMD = 0.13, 95% CI = [-0.55, 0.80]).

However, online self-compassion interventions demonstrated small effects on reducing depressive symptoms (12 studies that involved 1,328 participants, SMD = 0.24, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.42]) and stress (12 studies that involved 2,882 participants, SMD = 0.39, 95% CI = [0.23, 0.56]) at the immediate posttest only. There was no statistically significant difference of online self-compassion interventions from control groups in reducing depressive symptoms at follow-up (five studies that involved 572 participants, SMD = 0.20, 95% CI = [-0.13, 0.52]); anxiety at the immediate posttest (ten studies that involved 1,088 participants, SMD = 0.28, 95% CI = [-0.05, 0.62]); anxiety at follow-up (four studies that involved 333 participants, SMD = 0.03, 95% CI = [-0.42, 0.47]); and stress at follow-up (three studies that involved 1,870 participants, SMD = 0.02, 95% CI = [-0.07, 0.11]).

There was no statistically significant subgroup difference in all outcomes (p > 0.05) except for depressive symptoms at the immediate posttest (Chi2 = 6.24, p = 0.01) and stress at follow-up (Chi2 = 9.91, p = 0.002). In other words, there was no statistically significant difference in depressive symptoms at follow-up, anxiety at the immediate posttest and follow-up, and stress at the immediate posttest among studies according to the intervention delivery modes (i.e., in-person self-compassion interventions and online self-compassion interventions). However, there was a statistically significant subgroup difference in depressive symptoms at the immediate posttest (i.e., medium effects of in-person self-compassion interventions and small effects of online self-compassion interventions compared to control groups) and stress at follow-up (medium effects of in-person self-compassion interventions and no significant effect of online self-compassion interventions compared to control groups) among studies according to the delivery modes. Forest plots of subgroup analyses according to the intervention delivery modes are illustrated in Supplemental Materials (Figures S1 − S6).

Subgroup Analyses According to the Involvement of Targeted Participants with Psychological Distress Symptoms

Subgroup analyses found medium effects of self-compassion interventions on reducing depressive symptoms (12 studies that involved 1,021 participants, SMD = 0.56, 95% CI = [0.28, 0.85]) and stress (12 studies that involved 1,060 participants, SMD = 0.64, 95% CI = [0.43, 0.85]) at the immediate posttest and a small effect on reducing stress at follow-up (three studies that involved 399 participants, SMD = 0.35, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.69]) compared to control groups when studies directly targeted participants with psychological distress symptoms. Self-compassion intervention groups did not statistically differ from control groups in the other outcomes (i.e., depressive symptoms at follow-up and anxiety at the immediate posttest and follow-up) when studies directly targeted participants with psychological distress symptoms.

On the other hand, subgroup analyses showed small effects of self-compassion interventions on depressive symptoms at the immediate posttest (24 studies that involved 1,939 participants, SMD = 0.39, 95% CI = [0.24, 0.53]) and stress at the immediate posttest (18 studies that involved 2,960 participants, SMD = 0.31, 95% CI = [0.17, 0.45]) and medium effects of self-compassion interventions on depressive symptoms at follow-up (ten studies that involved 824 participants, SMD = 0.40, 95% CI = [0.10, 0.69]) and anxiety at the immediate posttest (22 studies that involved 1,838 participants, SMD = 0.40, 95% CI = [0.19, 0.62]) compared to control groups when studies did not directly target participants with some type of psychological distress. However, there was no statistically significant difference of self-compassion interventions from control groups in reducing anxiety and stress at follow-up when studies did not directly target participants with some type of psychological distress.

There was no statistically significant subgroup difference in all the outcomes (p > 0.05), except for stress at the immediate posttest (Chi2 = 6.96, p = 0.008). This indicates that there was no statistically significant difference among studies according to the involvement of directly targeted participants with some type of psychological distress in all the outcomes except for stress at the immediate posttest. Forest plots of subgroup analyses according to the involvement of targeted participants with psychological distress symptoms are illustrated in Supplemental Materials (Figures S7 − S12).

Risk of Bias of the Included Studies

Of the 56 included studies, 35 had a high risk of bias, 19 had an unclear risk of bias, and two studies (Mifsud et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2022) had a low risk of bias overall (Supplemental Materials – Table S2). The overall risk of bias across 56 studies was interpreted as high because more than half of the studies had a high risk of bias (i.e., 62.5%) (Higgins & Green, 2011). A blinded outcome assessment domain was not regarded as a key domain in the current review because all included studies used self-reported questionnaires as outcome measures. Twenty-six studies were judged to have a high risk of bias overall due to a high risk in one domain only, including a high risk of bias in the domain of incomplete outcome data in 18 studies due to missing outcome data from attrition across groups while excluding missing data without imputation in data analysis, in the domain of blinding of participants and personnel in seven studies, and in the domain of selective reporting in one study. Of the five key domains, those for allocation concealment, blinding of participants and research personnel, and selective reporting were determined to have an unclear risk of bias in the majority of the studies (i.e., 64.3%, 64.3%, and 58.9%, respectively). These studies did not provide a clear description of whether research personnel enrolling participants could foresee group assignment by using or not using appropriate methods (e.g., using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes), whether participants and research personnel were blinded, or whether the study protocol was available and registered. More than half the studies (i.e., 67.9%) had a low risk of bias in the domain of random sequence generation. Almost half the studies had a high risk of bias in the domain of incomplete outcome data (48.2%) while 44.6% of the studies had a low risk of bias by either having no missing outcome data or imputing missing data using appropriate methods.

Discussion