Abstract

Introduction

Suicide prevention research is a national priority, and national guidance includes the development of suicide risk management protocols (SRMPs) for the assessment and management of suicidal ideation and behavior in research trials. Few published studies describe how researchers develop and implement SRMPs or articulate what constitutes an acceptable and effective SRMP.

Methods

The Texas Youth Depression and Suicide Research Network (TX-YDSRN) was developed with the goal of evaluating screening and measurement-based care in Texas youth with depression or suicidality (i.e., suicidal ideation and/or suicidal behavior). The SRMP was developed for TX-YDSRN through a collaborative, iterative process, consistent with a Learning Healthcare System model.

Results

The final SMRP included training, educational resources for research staff, educational resources for research participants, risk assessment and management strategies, and clinical and research oversight.

Conclusion

The TX-YDSRN SRMP is one methodology for addressing youth participant suicide risk. The development and testing of standard methodologies with a focus on participant safety is an important next step to further the field of suicide prevention research.

Keywords: Adolescent, Suicidal ideation, Suicide, Risk assessment, Suicide risk management protocol

1. Introduction

Deaths from suicide in youths aged 10–14 and 15–19 have increased 178% and 76%, respectively, over the past decade in the United States [1]. Suicide research is a national priority [2], with the Surgeon General releasing a Call to Action in 2021 (https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/suicide-prevention/index.html). The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) provided guidance on conducting research with participants at elevated risk for suicide, to support research conduct that is safe, ethical, and feasible (available at https://www.nimh.nih.gov/funding/clinical-research/conducting-research-with-participants-at-elevated-risk-for-suicide-considerations-for-researchers). This guidance includes the development of suicide risk management protocols (SRMPs) for the assessment and management of suicidal ideation and behavior in research [3,4].

There are few published studies describing how researchers develop and implement SRMPs, as well as what constitutes an acceptable and effective SRMP [5]. The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study team published one of the earliest procedures for detecting, monitoring, and managing suicidal adult participants in a multi-site depression trial derived from the NIMH SRMP guidance [6]. Other SRMP examples include studies of adult participants in randomized trials in the emergency department [7,8], across primary care and outpatient settings [8], in an under-resourced setting using a community-partnered participatory research framework [9], and during phone screening eligibility assessments [10].

To date, no detailed SRMP example has been published for use with child and adolescent populations. Instead, studies involving suicidal youth participants have typically referenced their SRMPs briefly in outcome papers. The Treatment of Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) published procedures and findings related to their adjunct services to prevent attrition (ASAP) approach; one ASAP qualifying condition included “sudden and significant clinical deterioration including suicidality”, which occurred in 17.8% of the sample [11]. ASAP interventions included additional sessions for unstructured clinical assessment, supportive counseling to provide hope that treatment would be successful, and referral to treatment outside of the TADS protocol [11]. The Treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters (TASA) study described steps to provide human subjects protection, including vigorous pursuit of participants after missed appointments; a safety plan requirement; 24-h clinical back-up at each site; and study removal of participants whose clinical status indicated need for non-study treatment as evaluated by a designated ombudsperson independent of the study team [12]. A large randomized controlled trial comparing dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) to individual and group supportive therapy utilized the Linehan Suicide-Risk Assessment and Management Protocol in the DBT condition, with crisis procedures similar to those in TASA, where participants had a safety plan and access to active crisis intervention per standards of care [13]. Of note, the assessors in this study utilized the University of Washington Risk Assessment Protocol (UWRAP) which details strategies for assessing suicidal and self-injury risk pre- and post-assessment, strategies to decrease distress and improve mood, and guidelines for when the assessor should seek supervisor consultation and/or increase the level of clinical response [13].

The above procedures originate from studies testing suicide-reduction interventions, where youth participants had a study therapist for management of suicide risk; SRMPs for studies that involve assessment-only or that do not provide suicide-prevention interventions as part of the study design may require a different approach. For example, in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, a longitudinal study of preadolescent children, those who reported current suicidality or self-harm received additional assessment by a site-designated clinician. If safety concerns were identified, this was disclosed to the child's caregiver and the child was referred to the hospital for evaluation [14].

Unique challenges in SRMPs with youth populations include confidentiality, developmental factors, and parent/family involvement. More research is needed to understand the impact on youth of disclosure of suicide risk to parents/guardians [15,16]. Study teams also must be informed about state laws on emancipated minors, mature minors, minors’ ability to seek care without parental consent for suicide risk, and other special circumstances around crisis-related interventions (e.g., involuntary commitment to a psychiatric facility). This information must be in the informed consent/assent document when conducting research with suicidal youth [17].

One published review noted five core components of SRMPs, including training, educational resources for research staff, educational resources for research participants, risk assessment and management strategies, and clinical and research oversight. This review was restricted to studies with participants 16 and older [18]. An unpublished systematic descriptive analysis of SRMPs identified three areas in study materials where SRMP tasks should be: overview logistics (e.g., where the SRMP is described, such as in a grant or separate document); entry/exit specifications (e.g., how risk is identified; which instruments and cutoffs are used; how to maintain participants in the study); and process guidelines (e.g., instructions for when risk is identified; documentation protocols) [19].

The Texas Youth Depression and Suicide Research Network (TX-YDSRN), an initiative of the state-funded Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium, was developed as a Learning Healthcare System to align stakeholders around the goal of evaluating screening and measurement-based care in Texas youth with depression or suicidality (i.e., suicidal ideation and/or suicidal behavior). This manuscript will build on prior limited research on SRMPs in youth populations to describe the SRMP and trainings developed for TX-YDSRN, organized around the core components defined by Stevens and colleagues [18]: training, educational resources for research staff, educational resources for research participants, risk assessment and management strategies, and clinical and research oversight. We review the measures utilized for at-risk youth and discuss implications for the SRMP. Additionally, we review the initiative's SRMP guidance regarding immediate management of suicide risk in research settings.

2. Materials & methods

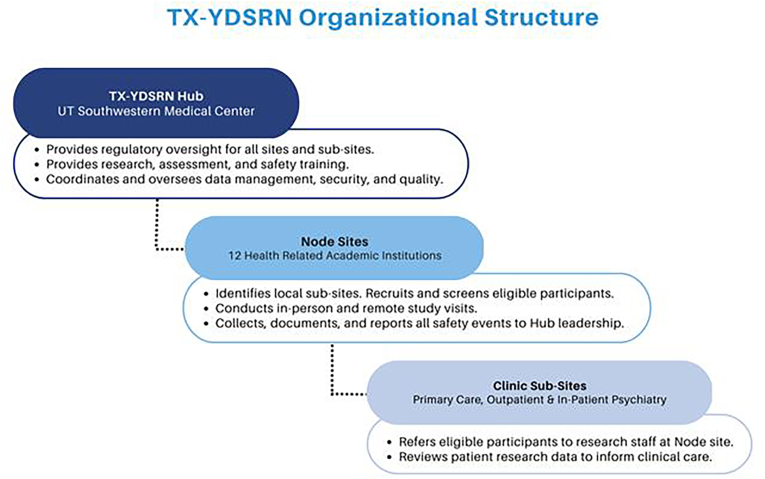

The development, aims, and procedures of TX-YDSRN were described previously (Trivedi et al., Under Review). Briefly, the TX-YDSRN (Fig. 1) is a collaboration among 12 academic medical centers in Texas serving as Nodes to recruit and oversee study recruitment at clinic-based Node Sub-Sites, with UT Southwestern Medical Center serving as the Hub to manage the overall network, provide data management, rater and coordinator training, quality assurance, protocol and manual development, training and support in measurement-based care (MBC), and regulatory aspects for the Network. The protocol called for Node Sub-Sites to continue to provide clinical care throughout the study in this longitudinal observational initiative. TX-YDSRN launched its Network Participant Registry, recruiting youth and young adult participants ages 8–20, and began enrollment in August 2020.

Fig. 1.

TX-YDSRN organizational structure.

The TX-YDSRN SRMP was developed with the Network Participant Registry study protocol, approved by the Hub's Institutional Review Board (IRB). The SRMP noted that the Network Hub had established methods for assessing suicide risk and protective factors, referring to the necessary level of care and for developing safety plans. Nodes would be trained in these protocols, which were based on the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Practice Parameters on Suicidal Behavior [20]. It was clear that the SRMP would need to be adjusted to allow for Nodes to work with their Sub-Site clinic partners to follow any established procedures of the Sub-Site, given that the site would be providing care.

TX-YDSRN Hub and Node leadership reviewed the Network Participant Registry protocol and associated SRMP during bi-weekly Network-wide meetings. Leadership discussions included how to best approach suicide risk and management with youth participants given variability in the 12 academic medical centers across the state, and affiliated Node Sub-Sites, which included primary care, pediatric care, specialty care, and/or community clinics. Some Sub-Sites had well-established screening, assessment, and management procedures for youth suicide, while others had less experience with systematic approaches to assessing and managing youth suicide. To better understand how Nodes might best engage with participants’ referring providers and systems at affiliated Sub-Sites, TX-YDSRN Hub and Node leadership obtained feedback from Sub-Sites through a survey about existing depression and suicide screening approaches, management of positive screens, and whether behavioral health providers were onsite.

Elements of the SRMP were presented at the TX-YDSRN Start-Up Meeting in July 2020 and trainings held with project assessors in July and August 2020. Updates were made to the SRMP during the first year of the project, consistent with a Learning Healthcare System model. Collaboration among the TX-YDSRN Hub and Nodes facilitated development, implementation, and adjustment of procedures based on Node feedback. The final SRMP includes worksheets (detailed below) designed to aid Nodes in individualizing the SRMP to their institution, healthcare system, and Sub-Sites.

3. Results

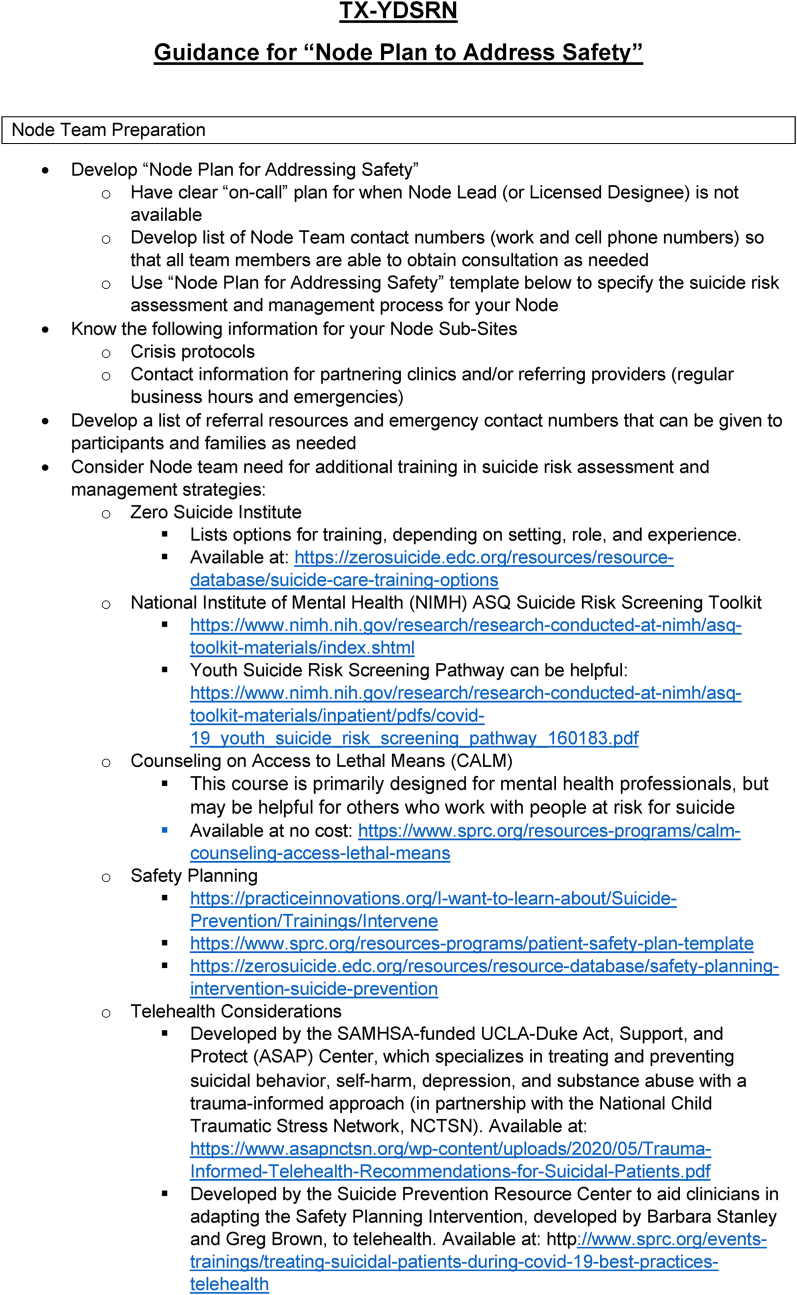

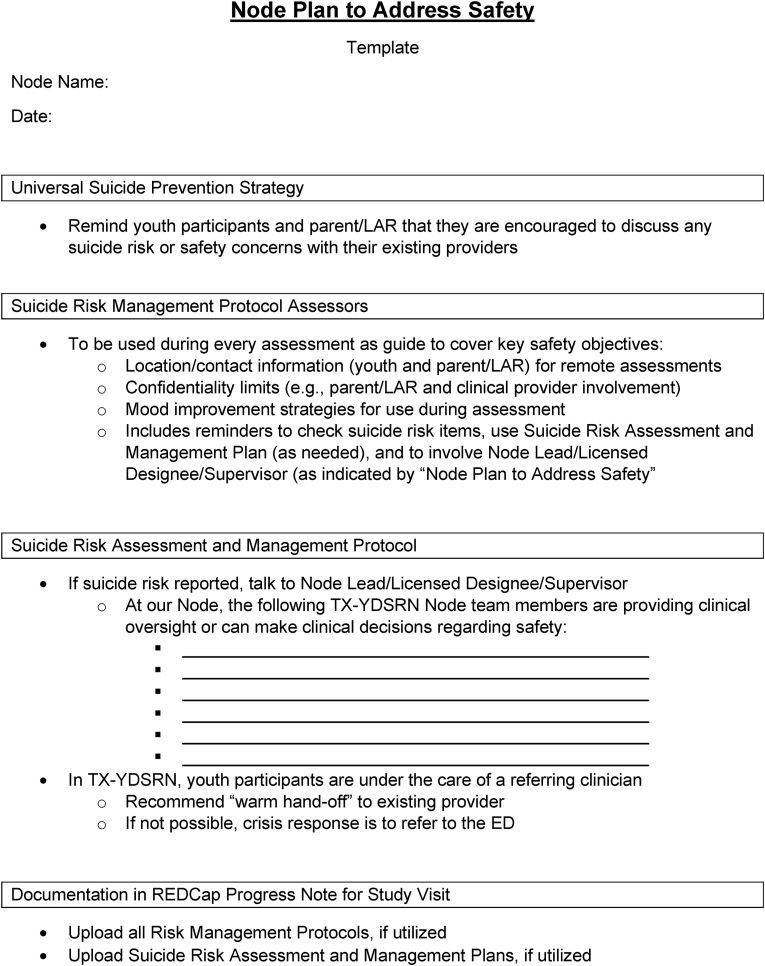

The final SRMP includes worksheets (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4), designed to aid Nodes in individualizing the SRMP to their institution, healthcare system, and Sub-Sites. The Node Plan to Address Safety worksheet (Fig. 2) details the preparatory steps that Nodes are encouraged to consider as they operationalize the SRMP. These points were reviewed at each Node Site Initiation Meeting, which occurred after approval by each Node IRB. Of note, the UT Southwestern IRB served as a single IRB of record for all Nodes; Node IRBs also reviewed the study. Node Site Initiation Meetings were led by Hub leadership and included review of Node Sub-Sites, development of workflow for participant recruitment at Sub-Sites, and development of Node-specific SRMP details.

Fig. 2.

TX-YDSRN node plan for address safety.

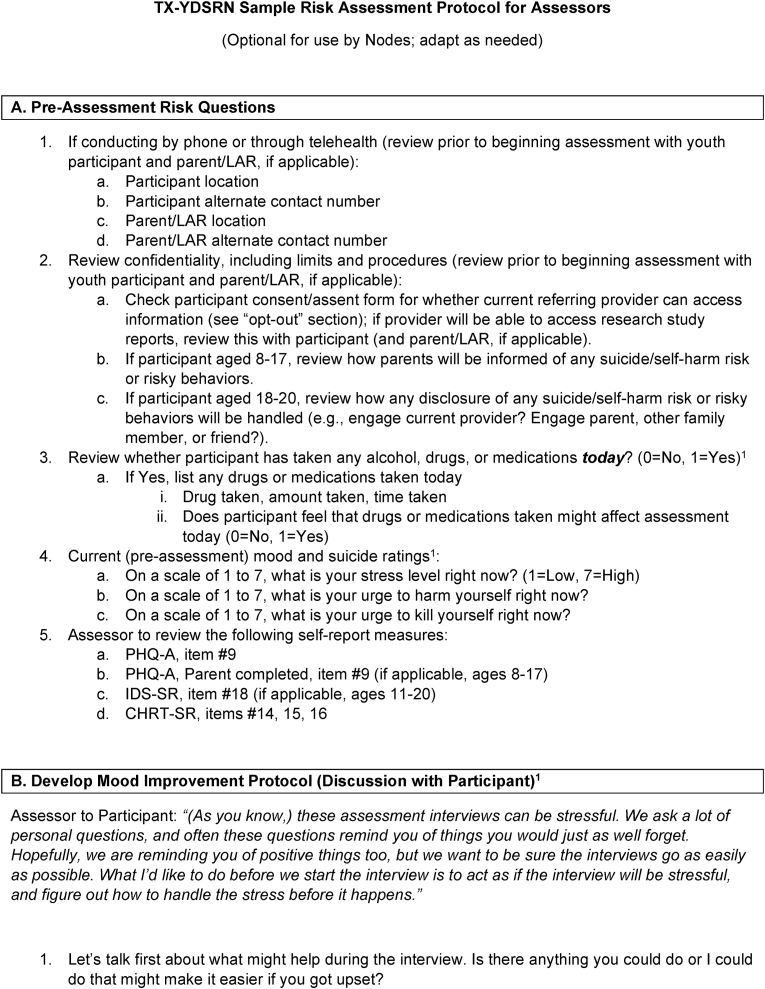

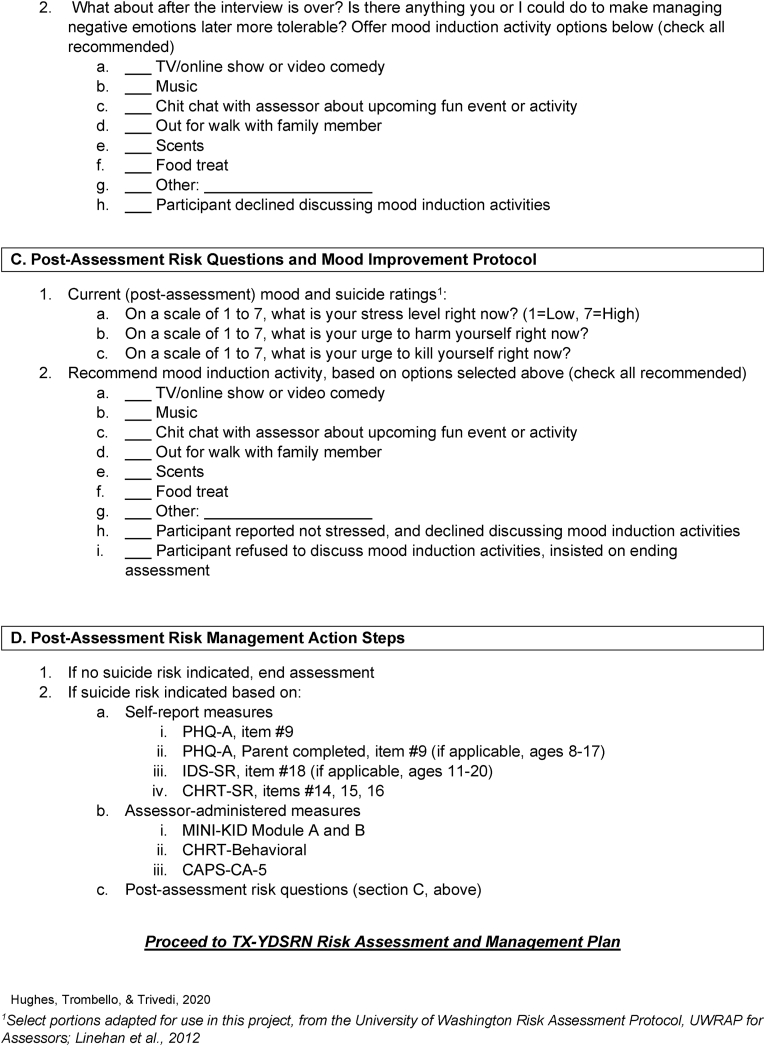

Fig. 3.

TX-YDSRN sample risk assessment protocol for assessors.

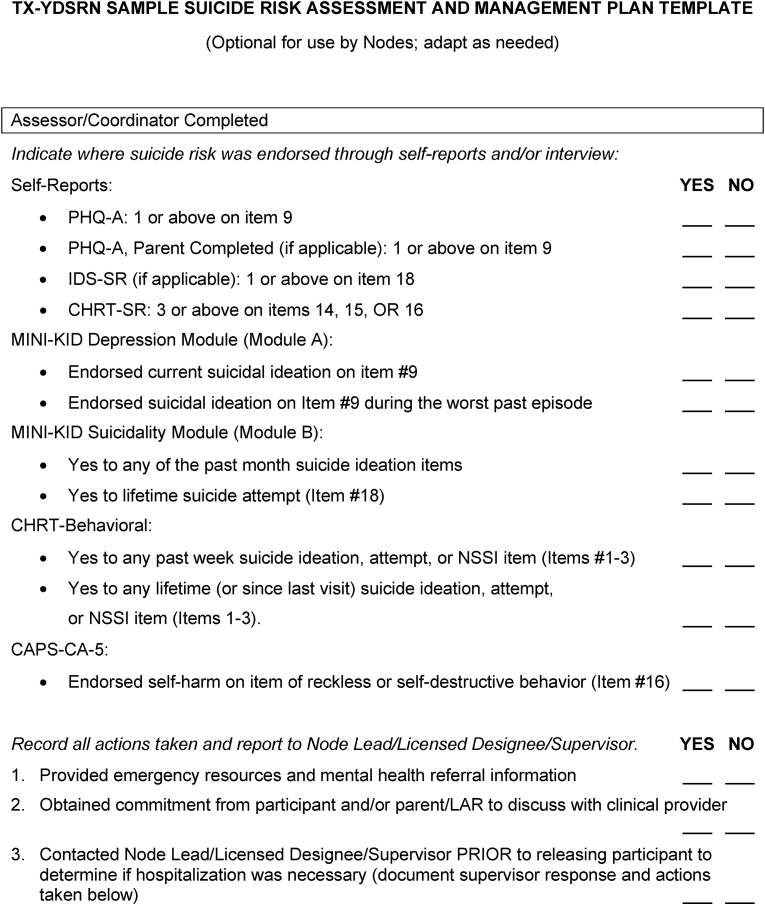

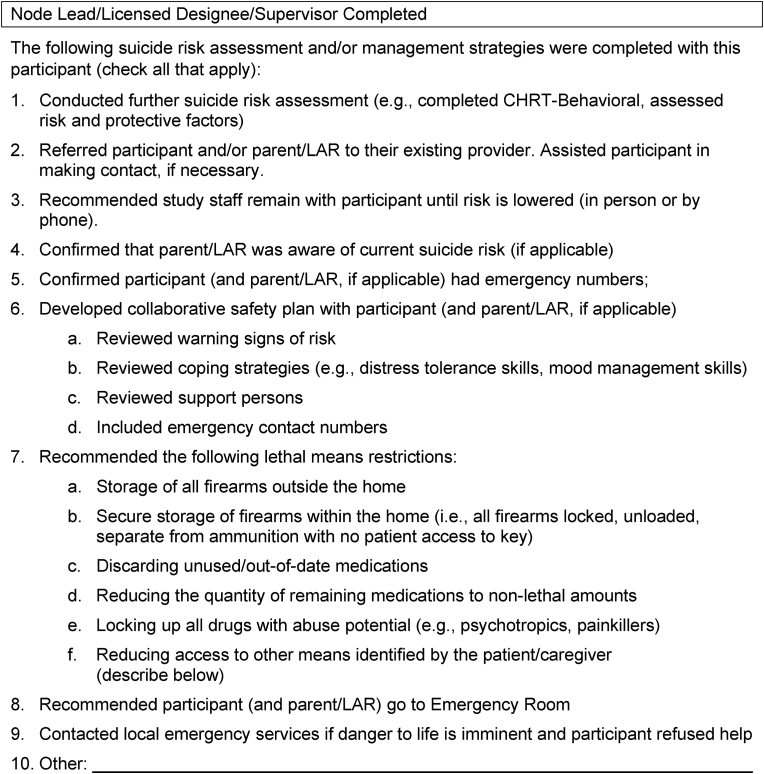

Fig. 4.

TX-YDSRN sample suicide risk assessment and management plan template.

3.1. Training

Study staff across the Network complete required Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative training that included Human Subjects Protection and Good Clinical Practice modules, as well as protocol-specific training provided by members of the Hub Team (Trivedi et al., Under Review). TX-YDSRN Node staff participated in the TX-YDSRN Start-Up Meeting, and Assessors participated in Assessor Training in July and August 2020. Recordings of these trainings are provided to new staff who join TX-YDSRN. SRMP procedures related to self-reports are reviewed in both trainings. Supplemental SRMP training is provided annually, and training continues as-needed to reinforce the SRMP and provide additional consultation. During training, coordinators are encouraged to develop a model for checking participant self-reports, with particular focus on items related to suicide risk. Additional SRMP training procedures for assessor training are detailed elsewhere (Trivedi et al., Under Review).

As part of the assessor certification process, assessors created mock assessment recordings and received 1:1 feedback with experienced clinical psychologists from the Hub, (authors JLH and JMT). In these feedback sessions, trainers reviewed mock assessment responses related to suicide risk on the assessor-administered measures (see section 3.4.1 below for a description of measures) and discussed assessor responses and actions based on the SRMP and their Node Plan to Address Safety. Additionally, assessors participated in consultation calls where suicide risk evaluation and management were reviewed by Hub trainers.

The TX-YDSRN Sample Risk Assessment Protocol for Assessors worksheet (Fig. 3) was developed by Hub leadership to aid coordinators and assessors in individualizing these for their Nodes and Sub-Sites. This worksheet was designed to be used during assessments as a guide to cover key safety objectives, including: 1) location and contact information of the youth and parent/legally authorized representative at the time of remote assessments; 2) confidentiality limits for parent/legally authorized representative and clinical provider involvement; 3) mood improvement strategies for use during or after an assessment if youth participant reports distress; and 4) reminders to check suicide risk items included in the SMRP, and to involve the Node Lead (or a licensed designee/supervisor), as specified in the Node Plan to Address Safety, when significant suicide risk is uncovered. This protocol was adapted from the University of Washington Risk Assessment Protocol (UWRAP) for Assessors [8].

3.2. Education resources for research staff

The first page of the Node Plan to Address Safety (Fig. 2) includes educational resources for research staff. Nodes are encouraged to consider the training needs of their research teams and to utilize these national and state educational resources accordingly. Nodes also have access to TX-YDSRN recorded trainings (described above) for onboarding new study staff or for refresher training for existing staff.

Nodes and Sub-Sites are supported in providing evidence-based depression care for youth, which includes screening for suicide risk, developing safety plans and referrals to intervention. The specific approach to treatment remains at the Node and Sub-Site level, and the Measurement-Based Care (MBC) trainings provided for Nodes and Sub-Sites included modules on evidence-based safety planning approaches [[21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]], as well as resources about evidence-based strategies for suicide prevention in youth [[27], [28], [29]]. While these trainings are intended to support Sub-Sites in providing MBC, they also promote evidence-based strategies for the assessment and management of suicide risk.

3.3. Educational resources for research participants

TX-YDSRN provides educational resources for research participants through its web page, which includes a general description of the Network, including leadership, staff, and participating institutions. Additionally, this web page is accessible without restriction, providing educational resources for the public. State and national resources related to youth suicide prevention and youth depression are listed for youth, parents, and families, including resources aimed at consumers from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Resource_Centers/Suicide_Resource_Center/Home.aspx) and the American Psychological Association Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Resource_Centers/Suicide_Resource_Center/Home.aspx). It also includes regularly updated summary findings about the TX-YDSRN initiative's enrollees, such as recruitment, retention, and demographics (https://tx-ydsrn.swmed.org/).

3.4. Risk assessment and management strategies

Given the Network Participant Registry initiative utilizes an assessment-only design, the SRMP provides guidance on responding to positive endorsement of suicide risk, defined as suicidal ideation or behavior. The Network Participant Registry Protocol called for measures to be obtained during monthly self-report assessments or periodic assessor-administered visits (Months 1, 6, 12, 18, and 24). Measures with suicide risk items from the Network Participant Registry Protocol are detailed below.

3.4.1. Assessor-administered sources of data related to suicide risk

Concise Health Risk Tracking Scale Behavioral Module (CHRT-Beh; [30]). The CHRT Behavioral Module is a clinician-rated assessment that is completed via clinical interview with the youth and parent. The scale includes probative questions to obtain clinical information to complete C-CASA criteria, and assessors may ask as many additional follow-up questions as needed. All items are rated as Yes or No. The CHRT-Beh includes items about lifetime and past week occurrence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Based on youth and parent responses, assessors rate the presence or absence of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, non-suicidal self-injury, preparatory acts, completed suicides, self-injurious behavior with unknown intent, death, accidental injuries (with no deliberate self-harm), and nonfatal injury (with insufficient information to classify). All items were relevant for the SRMP, with most focusing on current experiences of suicidal thoughts, behaviors, or self-injury.

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-Kid; [31]). A structured diagnostic interview conducted with study youth and parent, validated for diagnosing psychiatric disorders according to DSM-IV and ICD-10. Module A (Major Depressive Episode) and Module B (Suicidality) were most relevant for the SRMP.

Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 Child/Adolescent Version (CAPS-CA-5; [32]). Conducted with study youth, assesses a child's experience of DSM-5 criteria for PTSD. Item 16, which assesses reckless and self-destructive behavior, “In the past month, have you hurt yourself on purpose?” was relevant for the SRMP.

3.4.2. Self-report of data-sources related to suicide risk

Concise Health Risk Tracking Scale Self-Report (CHRT-SR; [30]). Evaluates thoughts about suicide and thoughts and feelings associated with an increased risk for suicide. Its psychometric properties have been well-established in children and adolescents [33,34]. The last three scale items, which assess suicidal ideation, suicidal ideation with method, and suicidal ideation with plan, were most relevant for the SRMP.

Patient Health Questionnaire-A (PHQ-A; [35]). Nine-item inventory, assesses for symptoms in all nine domains of a major depressive episode. It is the PHQ-9, modified for adolescents. Parents also complete this measure about their child's symptoms (PHQ-A-Parent). Psychometrics with primary care youth samples have previously been detailed [35]. Item 9, which assesses suicidal ideation, was relevant for the SRMP.

Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Self Report (IDS-SR; [36]). 30-item questionnaire, measuring depressive symptoms [36]. Item 18, which assesses suicidal ideation, was relevant for the SRMP.

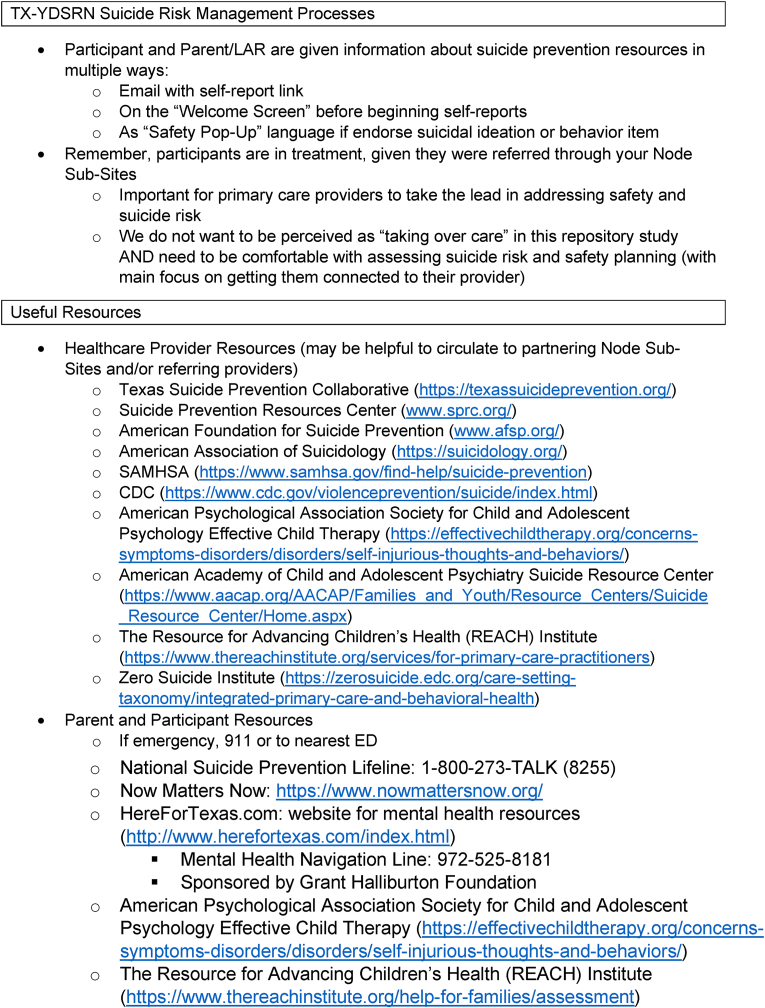

3.4.3. Suicide risk assessment strategies

The TX-YDSRN Hub oversees data management activities, with data being collected through REDCap, a self-managed, HIPAA-compliant web-based electronic data capture (EDC) system. As self-report measures are sent to youth participants and parents for monthly completion, language was developed to clarify the purpose of study measures and to encourage help-seeking behavior if a youth was found to be in distress or if a parent was concerned about their child's safety. During online assessment sessions that are not immediately monitored by study staff, an email is automatically sent with the REDCap link for that session's online self-report measures, stating “If you are in crisis and need immediate assistance, talk to your parents, a family member, or a friend to help you contact your doctor, mental health care provider or therapist, or another qualified healthcare professional. If you are in immediate danger, please call 911 or go to your nearest emergency room.” The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and National Alliance of Mental Illness (NAMI) Helpline numbers are also provided in the email. The welcome screen for the online self-report battery also has a reminder on how to seek help from a therapist or doctor: “As a reminder, these surveys are not to be used to get help from a doctor or therapist. If you need help keeping safe now, talk to your parents, a family member, or friend to help you contact your doctor or therapist – or have your parent make the call for you.” Similar language is on the parent self-report welcome screen.

Additionally, “safety pop-up” language was developed, where if a youth participant or parent positively endorse a self-report item on a measure of suicidal ideation or behavior, a pop-up appears that states, “Based on your response, you might want help right now. If you need help keeping safe, talk to your parents, a family member, or a friend to help you contact your doctor or therapist – or have your parent make the call for you. If you are in immediate danger, please call 911 or go to your nearest emergency room.” The pop-up also includes the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline number and the statement: “As a reminder, the Youth Depression and Suicide Research Network team do not have immediate access to your study survey responses, and these surveys are not to be used to get help from a doctor or therapist. Please see ideas above for how to get help immediately.”

During assessment sessions involving direct interaction, Node staff follow their plan for reviewing the self-report responses prior to a participant leaving the Node or Sub-Site location (if in person visit) or within 1 business day of measure completion (if remote visit). If a participant positively endorses any of the suicidal ideation or behavior items, the Node then implements their Node Plan to Address Safety.

3.4.4. Suicide risk management strategies

Given that TX-YDSRN participants are referred by Node Sub-Site providers and are in treatment for depression and/or suicidality, it is important that those providers take the lead in addressing safety and suicide risk. The TX-YDSRN Hub supports each Node in developing strategies for managing suicide risk that involve collaboration with the participant's provider to support continuity of care. Youth participants and parents are informed in the consent/assent forms about a potential breach of confidentiality for disclosure of suicidal ideation or behavior and specific procedures for informing the youth's mental health care or primary care provider about the suicide risk.

If a participant endorses suicidal ideation or behavior via self-report or in an assessor-administered session, Node staff are advised to alert the referring Sub-Site clinician, and to refer the youth and parent to the referring Sub-Site system. Alternatively, Node staff may conduct further assessment and employ direct clinical management procedures, such as supporting disclosure to the parent, safety planning, addressing lethal means restriction and home safety, or referral to a local emergency department. The optional TX-YDSRN Sample Suicide Risk Assessment and Management Plan Template (Fig. 4) was developed to aid Nodes in reviewing and documenting these steps. If a participant has stopped receiving services from the referring Node Sub-Site, Nodes have developed a list of referral resources and emergency contact numbers that can be given to participants and families to support linkage back into care. Documentation of all suicide risk management procedures is completed in a REDCap study visit note. Serious adverse events (SAEs) are expected in this study and study staff are trained to document and report these events. The Hub reviews all AEs and SAEs as part of regulatory oversight.

The most common brief intervention for response to a positive endorsement of suicide risk is safety planning. As described above, Nodes received training in evidence-based safety planning, with focus on the Family Intervention for Suicide Prevention/SAFETY-Acute [[21], [22], [23]] and the Safety Planning Intervention [[24], [25], [26]]. Additionally, the first page of the Node Plan to Address Safety (Fig. 2) includes educational resources, including safety planning and lethal means restriction counseling trainings for research staff from national and state resources.

3.5. Clinical and research oversight

As part of the Node Plan to Address Safety, Nodes determined the clinical oversight structure for their research team. This varied across Nodes due to the diverse structures in place across institutions. Each Node was required to develop a plan and maintain a copy in their regulatory binder. In some cases, the Node Lead is a licensed clinician who serves as clinical supervisor for assessors and clinicians; in other cases, the assessors are licensed clinicians and Node Leads only provide consultation. As described above, Nodes are encouraged to collaborate with Sub-Sites to support participants and families in seeking clinical care from their established providers whenever feasible.

The Hub meets weekly with each Node separately to address concerns or questions, including participant related safety and regulatory questions. These questions are answered during the meeting, or they are resourced to faculty members within the Hub and answered within the day. In addition to the bi-weekly Assessor meetings, a bi-weekly Coordinator meeting is available. Both the larger Coordinator meeting and the one-on-one individual meetings provide multiple training and support opportunities to the Nodes.

Events meeting SAE criteria are reviewed and signed off on by each Node's Lead or Co-Lead. Hub level quality assurance monitors review safety documentation regularly and advise sites to report any previously unreported safety issues and ensure that safety-related events are followed to resolution and reported appropriately. Every AE/SAE is reviewed to confirm if the event is an UPIRSO (Unanticipated Problem Involving Risks to Human Subjects or Others) and reported to the UTSW IRB, as required. Staff education, re-training or appropriate corrective actions are implemented at sites when unreported or unidentified reportable AEs or serious events are discovered, to help ensure future identification and timely reporting. Annually, a summary of all SAEs is provided to the UTSW IRB.

4. Discussion

Given rates of youth suicide, it is essential to conduct research on identifying, preventing, and treating suicidal ideation and behavior. The TX-YDSRN SRMP was developed to support safe practices in response to serious suicide risk in a state-wide longitudinal registry study of youth with depression and/or suicidality. While we know that there is no inherent risk in conducting mental health research and asking about suicide [37], it is important that research protocols include detailed strategies for responding to and supporting suicidal participants. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that asking about suicide provided small, yet significant, benefits to participants [38].

The TX-YDSRN SRMP includes the five core components of SRMPs as identified by Stevens and colleagues [18]: training, educational resources for research staff, educational resources for research participants, risk assessment and management strategies, and clinical and research oversight. The iterative refining of the SRMP for use across twelve Texas institutions resulted in worksheets to aid research teams in operationalizing suicide risk assessment and management procedures.

There are limitations associated with the process used to develop the TX-YDSRN SRMP. Most people who report suicidal ideation do not attempt suicide; the TX-YDSRN SRMP procedures focuses on suicidal ideation and behavior items, and including other markers of acute risk, such as those in the CHRT-SR which have demonstrated predictive validity in youth samples [33], might result in a better approach to safety. Also, the iatrogenic effects of asking about suicide in pre-teens has not been evaluated [39]; given this SRMP was used with participants as young as age 8, there may be a need to develop different procedures for pre-teens should future research efforts identify a differential risk of asking about suicide in that age range. Further, the initiative's Nodes and Sub-Sites had a wide range of resources and research experience, resulting in a need to develop flexible and adaptable strategies. Varied levels of training were required to ensure that sites were operating at an equivalent level as Nodes and Sub-Sites had differing levels of experience with youth suicide prevention research procedures and risk management processes.

5. Conclusions

While there is not a clear consensus on what constitutes an acceptable and effective SRMP [5], the TX-YDSRN SRMP has been well-received by Nodes, Sub-Sites, participants, and families. While TX-YDSRN was not designed to test its SRMP's effectiveness in reducing immediate suicide risk for participants, there is no evidence that it is ineffective or that it causes harm. Developing and testing standard methodologies for participant safety, particularly in youth populations, is an important next step to further the field of suicide prevention research.

Funding

The Texas Youth Depression and Suicide Research Network is a research initiative of the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium (TCMHCC) and the Center for Depression Research and Clinical Care of the Peter O'Donnell Jr. Brain Institute at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The TCMHCC was created by the 86th Texas Legislature and, in part, funds multi-institutional research to improve mental health care for children and adolescents in Texas. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the various funding organizations. The funding source had no role in the design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Within the past 12 months, Dr. Trivedi has provided consulting services to Axsome Therapeutics, Biogen MA Inc., Cerebral Inc., Circular Genomics Inc, Compass Pathfinder Limited, Daiichi Sankyo Inc, GH Research Limited, Heading Health Inc, Janssen, Legion Health Inc, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Mind Medicine (MindMed) Inc, Merck Sharp & Dhome LLC, Naki Health, Ltd., Neurocrine Biosciences Inc, Otsuka American Pharmaceutical Inc, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc, Praxis Precision Medicines Inc, Relmada Therapeutics, Inc, SAGE Therapeutics, Signant Health, Sparian Biosciences Inc, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd, and WebMD. He sits on the Scientific Advisory Board of Alto Neuroscience Inc, Cerebral Inc., Compass Pathfinder Limited, Heading Health, GreenLight VitalSign6 Inc, Legion Health Inc, and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. He holds stock in Alto Neuroscience Inc, Cerebral Inc, Circular Genomics Inc, GreenLight VitalSign6 Inc, Legion Health Inc. Additionally, he has received editorial compensation from American Psychiatric Association, and Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the youth and families for their participation in the Texas Youth Depression and Suicide Research Network. We also want to acknowledge the hard work and dedication of the Node teams and leadership across Texas (https://tx-ydsrn.swmed.org), as well as to the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium for their support of these efforts (https://tcmhcc.utsystem.edu). Specifically, we acknowledge the TX-YDSRN Team from the following sites: Baylor Medical Center: Gabrielle Armstrong, Emily Bivins, Kendall Drummond, Andrew Guzick, Madeleine Fuselier, David Riddle, Johanna Saxena, Eric Storch; Texas A&M University System Health Science Center: Tri Le, Emily Turek, Olga Raevskaya; Texas Tech University Health Science Center Lubbock: Chanaka Kahathaduwa, Robyn Richmond, Aunththara Lokubandara, Victoria Johnson; Texas Tech University Health Science Center El Paso: Sarah L Martin, Zuber Mulla, Alejandro Fornelli, Caitlin Chanoi; University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School: Ryan Brown, Tyler Wilson, Caroline Lee, and Stephanie Noble Hernandez; University of Texas Health San Antonio: Norma Balli-Borrero, Sofia Ballesteros, Abigail Cuellar, Kristina Martinez Fields; University of Texas Rio Grande Valley: Cynthia Garza, Diana Chapa, Catherine Hernandez; University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center: Graham J. Emslie, Betsy D. Kennard, Laura Stone, Raney Sachs; University of Texas Health Science Center Houston: Cesar Soutullo, Cordelia Collins; University of Texas Health Science Center Tyler: Jamon Blood, Kiley Schneider, Donna Rokahr, University of Texas Medical Branch: Michaella Petrosky, Layla Kratovic, Akila Gopalkrishnan; University of North Texas Health Science Center: David Farmer, Summer Ladd, Aimon Anwar, Amanda Rosenberg.

Additionally, Cody Dodd, PhD, and Karen Wagner, MD, collaborated in the development of the TX-YDSRN Sample Suicide Risk Assessment and Management Plan Template.

References

- 1.Curtin S.C., Heron M. Death rates due to suicide and homicide among persons aged 10-24: United States, 2000-2017. NCHS Data Brief. 2019;(352):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of the Surgeon . 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action: A Report of the U.S. Surgeon General and of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. US Department of Health & Human Services (US); Washington (DC): 2012. G. and P. National action alliance for suicide, publications and reports of the Surgeon general. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher C.B., et al. Ethical issues in including suicidal individuals in clinical research. Irb. 2002;24(5):9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearson J.L., et al. Intervention research with persons at high risk for suicidality: safety and ethical considerations. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 25):17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schatten H.T., et al. Monitoring, assessing, and responding to suicide risk in clinical research. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2020;129(1):64–69. doi: 10.1037/abn0000489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nierenberg A.A., et al. Suicide risk management for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression study: applied NIMH guidelines. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2004;38(6):583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boudreaux E.D., et al. The emergency department safety assessment and follow-up evaluation (ED-SAFE): method and design considerations. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2013;36(1):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linehan M.M., Comtois K.A., Ward-Ciesielski E.F. Assessing and managing risk with suicidal individuals. Cognit. Behav. Pract. 2012;19(2):218–232. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodsmith N., et al. Implementation of a community-partnered research suicide-risk management protocol: case study from community partners in care. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021;72(3):281–287. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward-Ciesielski E.F., Wilks C.R. Conducting research with individuals at risk for suicide: protocol for assessment and risk management. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2020;50(2):461–471. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.May D.E., et al. A manual-based intervention to address clinical crises and retain patients in the Treatment of Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2007;46(5):573–581. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180323342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brent D.A., et al. The Treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters study (TASA): predictors of suicidal events in an open treatment trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2009;48(10):987–996. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbe4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCauley E., et al. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatr. 2018;75(8):777–785. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeVille D.C., et al. Prevalence and family-related factors associated with suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and self-injury in children aged 9 to 10 years. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3(2) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox K.R., et al. Exploring adolescent experiences with disclosing self-injurious thoughts and behaviors across settings. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2022;50(5):669–681. doi: 10.1007/s10802-021-00878-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hom M.A., et al. Examining the characteristics and clinical features of in- and between-session suicide risk assessments among psychiatric outpatients. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018;74(6):806–818. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King C.A., Kramer A.C. Intervention research with youths at elevated risk for suicide: meeting the ethical and regulatory challenges of informed consent and assent. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2008;38(5):486–497. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.5.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevens K., et al. Core components and strategies for suicide and risk management protocols in mental health research: a scoping review. BMC Psychiatr. 2021;21(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-03005-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vannoy S., Whiteside U., Unutzer J. Current practices of suicide risk management protocols in research. Crisis. 2010;31(1):7–11. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Academy of C., Adolescent P. Summary of the practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):495–499. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes J.L., Asarnow J.R. Enhanced mental health interventions in the emergency department: suicide and suicide attempt prevention in the. Clin. Pediatr. Emerg. Med. 2013;14(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cpem.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asarnow J.R., et al. An emergency department intervention for linking pediatric suicidal patients to follow-up mental health treatment. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011;62(11):1303–1309. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.11.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asarnow J.R., Berk M.S., Baraff L.J. Family Intervention for Suicide Prevention: a specialized emergency department intervention for suicidal youths. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009;40(2):118–125. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanley B., et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (CBT-SP): treatment model, feasibility, and acceptability. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2009;48(10):1005–1013. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbfe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stanley B., Brown G.K. Safety planning intervention: a brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognit. Behav. Pract. 2012;19(2):256–264. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanley B., et al. Comparison of the safety planning intervention with follow-up vs usual care of suicidal patients treated in the emergency department. JAMA Psychiatr. 2018;75(9):894–900. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann J.J., Michel C.A., Auerbach R.P. Improving suicide prevention through evidence-based strategies: a systematic review. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2021;178(7):611–624. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Runyan C.W., et al. Lethal means counseling for parents of youth seeking emergency care for suicidality. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2016;17(1):8–14. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.11.28590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(SAMHSA), S.A.a.M.H.S.A . SAMHSA Publication No. PEP20-06-01-002; 2020. Treatment for Suicidal Ideation, Self-Harm, and Suicide Attempts Among Youth. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trivedi M.H., et al. Concise Health Risk Tracking scale: a brief self-report and clinician rating of suicidal risk. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2011;72(6):757–764. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m06837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheehan D.V., et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. ;quiz 34-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pynoos R.S., Weathers F.W., Steinberg A.M., Marx B.P., Layne C.M., Kaloupek D.G., Schnurr P.P., Keane T.M., Blake D.D., Newman E., Nader K.O., Kriegler J.A. Clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-5 - child/adolescent version. 2015. www.ptsd.va.gov Scale available from the National Center for PTSD at.

- 33.Mayes T.L., et al. Predicting future suicidal events in adolescents using the concise health risk tracking self-report (CHRT-SR) J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;126:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayes T.L., et al. Psychometric properties of the concise health risk tracking (CHRT) in adolescents with suicidality. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;235:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson J.G., et al. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J. Adolesc. Health. 2002;30(3):196–204. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rush A.J., et al. The inventory of depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol. Med. 1996;26(3):477–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polihronis C., et al. What's the harm in asking? A systematic review and meta-analysis on the risks of asking about suicide-related behaviors and self-harm with quality appraisal. Arch. Suicide Res. 2022;26(2):325–347. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2020.1793857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blades C.A., et al. The benefits and risks of asking research participants about suicide: a meta-analysis of the impact of exposure to suicide-related content. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018;64:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes J.L., et al. Suicide in young people: screening, risk, assessment, and intervention. BMJ. 2023;381 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-070630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]