Abstract

Background

Following sexual abuse, children and young people may develop a range of psychological problems, including anxiety, depression, post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and a range of behaviour problems. Those working with children and young people experiencing these problems may use one or more of a range of psychological approaches.

Objectives

To assess the relative effectiveness of psychological interventions compared to other treatments or no treatment controls, to overcome psychological consequences of sexual abuse in children and young people up to 18 years of age.

Secondary objectives

To rank psychotherapies according to their effectiveness. To compare different ‘doses’ of the same intervention.

Search methods

In November 2022 we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, 12 other databases and two trials registers. We reviewed the reference lists of included studies, alongside other work in the field, and communicated with the authors of included studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials comparing psychological interventions for sexually abused children and young people up to 18 years old with other treatments or no treatments. Interventions included: cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), psychodynamic therapy, family therapy, child centred therapy (CCT), and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR). We included both individual and group formats.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies, extracted data and assessed the risk of bias for our primary outcomes (psychological distress/mental health, behaviour, social functioning, relationships with family and others) and secondary outcomes (substance misuse, delinquency, resilience, carer distress and efficacy).

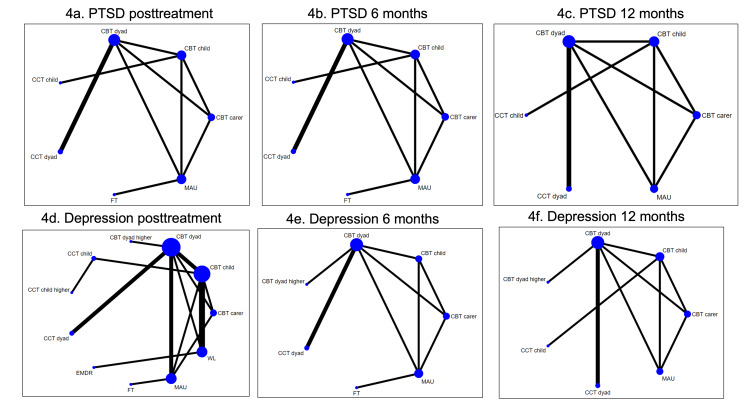

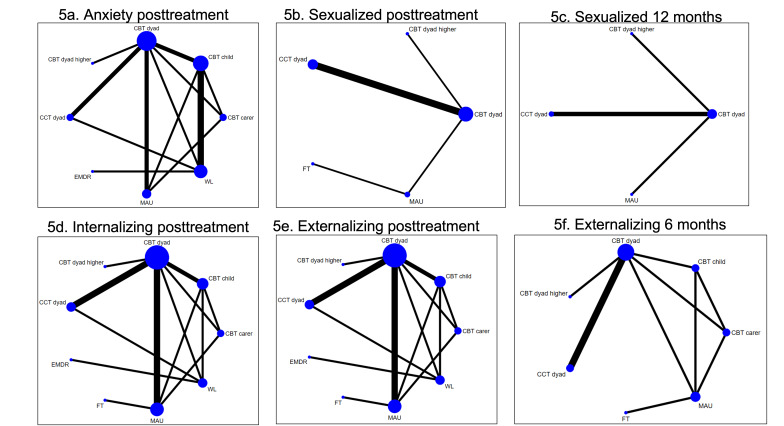

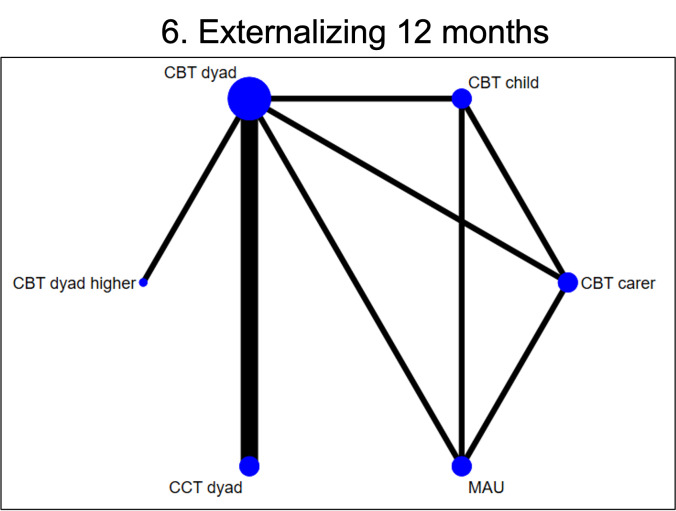

We considered the effects of the interventions on all outcomes at post‐treatment, six months follow‐up and 12 months follow‐up. For each outcome and time point with sufficient data, we performed random‐effects network and pairwise meta‐analyses to determine an overall effect estimate for each possible pair of therapies. Where meta‐analysis was not possible, we report the summaries from single studies. Due to the low number of studies in each network, we did not attempt to determine the probabilities of each treatment being the most effective relative to the others for each outcome at each time point.

We rated the certainty of evidence with GRADE for each outcome.

Main results

We included 22 studies (1478 participants) in this review. Most of the participants were female (range: 52% to 100%), and were mainly white. Limited information was provided on socioeconomic status of participants. Seventeen studies were conducted in North America, with the remaining studies conducted in the UK (N = 2), Iran (N = 1), Australia (N = 1) and Democratic Republic of Congo (N = 1). CBT was explored in 14 studies and CCT in eight studies; psychodynamic therapy, family therapy and EMDR were each explored in two studies. Management as usual (MAU) was the comparator in three studies and a waiting list was the comparator in five studies. For all outcomes, comparisons were informed by low numbers of studies (one to three per comparison), sample sizes were small (median = 52, range 11 to 229) and networks were poorly connected. Our estimates were all imprecise and uncertain.

Primary outcomes At post‐treatment, network meta‐analysis (NMA) was possible for measures of psychological distress and behaviour, but not for social functioning. Relative to MAU, there was very low certainty evidence that CCT involving parent and child reduced PTSD (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.87, 95% confidence intervals (CI) ‐1.64 to ‐0.10), and CBT with only the child reduced PTSD symptoms (SMD ‐0.96, 95% CI ‐1.72 to ‐0.20). There was no clear evidence of an effect of any therapy relative to MAU for other primary outcomes or at any other time point.

Secondary outcomes Compared to MAU, there was very low certainty evidence that, at post‐treatment, CBT delivered to the child and the carer might reduce parents' emotional reactions (SMD ‐6.95, 95% CI ‐10.11 to ‐3.80), and that CCT might reduce parents' stress. However, there is high uncertainty in these effect estimates and both comparisons were informed only by one study. There was no evidence that the other therapies improved any other secondary outcome.

We attributed very low levels of confidence for all NMA and pairwise estimates for the following reasons. Reporting limitations resulted in judgements of 'unclear' to 'high' risk of bias in relation to selection, detection, performance, attrition and reporting bias; the effect estimates we derived were imprecise, and small or close to no change; our networks were underpowered due to the low number of studies informing them; and whilst studies were broadly comparable with regard to settings, the use of a manual, the training of the therapists, the duration of treatment and number of sessions offered, there was considerable variability in the age of participants and the format in which the interventions were delivered (individual or group).

Authors' conclusions

There was weak evidence that both CCT (delivered to child and carer) and CBT (delivered to the child) might reduce PTSD symptoms at post‐treatment. However, the effect estimates are uncertain and imprecise. For the remaining outcomes examined, none of the estimates suggested that any of the interventions reduced symptoms compared to management as usual.

Weaknesses in the evidence base include the dearth of evidence from low‐ and middle‐income countries. Further, not all interventions have been evaluated to the same extent, and there is little evidence regarding the effectiveness of interventions for male participants or those from different ethnicities. In 18 studies, the age ranges of participants ranged from 4 to 16 years old or 5 to 17 years old. This may have influenced the way in which the interventions were delivered, received, and consequently influenced outcomes.

Many of the included studies evaluated interventions that were developed by members of the research team. In others, developers were involved in monitoring the delivery of the treatment. It remains the case that evaluations conducted by independent research teams are needed to reduce the potential for investigator bias.

Studies addressing these gaps would help to establish the relative effectiveness of interventions currently used with this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Child, Preschool; Female; Humans; Male; Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Cognitive Behavioral Therapy/methods; Network Meta-Analysis; Psychosocial Intervention; Psychotherapy; Psychotherapy/methods; Sex Offenses

Plain language summary

How effective are the psychological interventions used for treating the consequences of sexual abuse in children and adolescents

Key messages

• A number of psychological therapies are used to help children and young people overcome the consequences of sexual abuse.

• There is largely uncertain evidence to suggest that any particular interventions is better than management as usual in helping children and young people recover from sexual abuse.

• We need more and better studies of interventions to establish whether one is better than another in addressing the various consequences of sexual abuse.

What do we mean by psychological interventions?

Psychological interventions are those that try to bring about change in people. They are often referred to as 'talking therapies' but they also include therapies in which communication between therapist and patient is based on activity, such as play, or art.

There is a range of psychological interventions that are used to help children and young people who have been sexually abused to overcome the sorts of difficulties that can develop as a result of the abuse; for example, post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and a range of behaviour problems.

Why is this important for children and young people who have been sexually abused?

Previous systematic reviews suggest that psychological therapies can improve outcomes for children, but we do not know whether some therapies are more effective than others.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out which interventions were best for treating the range of problems that can occur following sexual abuse. We wanted to find out if we could rank them in order of how well they work. For example, we wanted to find out which intervention was the best at helping children who have PTSD, or children who are depressed. Which was second best? And so on.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that examined the effectiveness of a range of psychological therapies, including cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT), eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (known as EMDR), child‐centred therapy (CCT), psychodynamic therapy, and family therapy. We included studies that compared:

• one therapy to another therapy;

• different 'doses' of therapy; for example, eight weeks of a therapy to 16 weeks of the same therapy;

• one version of a therapy with another version; for example, one that involved parents as well as the child with the same therapy that did not;

• one therapy to management as usual; and

• one therapy to no therapy (mainly those on a waiting list).

We used methods that allowed us to compare the effectiveness of each therapy against others, for particular outcomes. We summarised the results of the studies and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as the number of studies and how large or small they were.

What did we find?

We found 22 studies (1478 participants) and most of them were from North America. Fourteen of these examined the effectiveness of CBT and eight examined the effectiveness of CCT. Psychodynamic therapy, family therapy and EMDR were each examined in two studies. Management as usual was the comparator in three studies and a waiting list was the comparator in five studies.

Main results

On the available evidence it is not clear whether one intervention is more effective than others in helping children and young people who have been sexually abused. There is some evidence, though it is largely uncertain and imprecise, that CBT may be better than management as usual when it comes to reducing the symptoms of PTSD at the end of treatment. No evidence pointed to the effectiveness of other therapies for PTSD, and no therapy appeared to do better than management as usual for the other outcomes we examined.

The evidence base for the effectiveness of other psychotherapeutic interventions for sexually abused children and adolescents is limited, particularly in relation to psychodynamic therapy, family therapy and EMDR.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Our confidence in the results is not strong. The treatment effects we identified were small or close to 'no change' and not very precise. Whilst the studies were broadly comparable in some respects (settings; the use of a manual to deliver the intervention; the 'amount' of therapy), there was considerable variability in others, such as the age of participants and the format in which the interventions were delivered (individual or group).

The results of further research could differ from the results of this review.

How up to date is this evidence?

The evidence is up to date to 1 November 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings table 1. Results of the indirect evidence for post‐traumatic stress disorder post‐treatment in sexually abused people under 18 years old.

| Estimates of effects, confidence intervals, and certainty of the indirect evidence for post‐traumatic stress disorder post‐treatment in sexually abused people under 18 years old | |||

|

Patient or population: sexually abused people under 18 years old Settings: clinical setting Interventions: WL, FT, EMDR, CCT dyad, CCT child, CBT dyad, CBT child, CBT carer Comparator (reference): MAU | |||

|

Total number of studies: 11 Total number of participants: 627 |

Relative effecta (95% CI) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Interpretations of findings |

| WL | ‐0.15 (‐1.85 to 1.55) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of WL overperforming MAU |

| FT | ‐0.58 (‐1.41 to 0.26) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of FT overperforming MAU |

| EMDR | ‐0.48 (‐1.44 to 0.49) | Very Low | Uncertain evidence of EMDR overperforming MAU |

| CCT dyad | ‐0.87 (‐1.64 to ‐0.10) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CCT dyad overperforming MAU |

| CCT child | 0.66 (‐0.42 to 1.75) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CCT child overperforming MAU |

| CBT dyad | ‐0.35 (‐1.55 to 0.85) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CBT dyad overperforming MAU |

| CBT child | ‐0.96 (‐1.72 to ‐0.20) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CBT child overperforming MAU |

| CBT carer | ‐0.46 (‐1.22 to 0.29) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CBT carer overperforming MAU |

| CBT carer: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered only to the carer; CBT child: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered only to the child; CBT dyad: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered to the child and the carer; CCT child: child‐centred therapy delivered only to the child; CCT dyad: child‐centred therapy delivered to the child and the carer; CI: confidence interval; EMDR: eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing; FT: family therapy; MAU: management as usual; NMA: network meta‐analysis; SoF: summary of findings table; WL: waiting list | |||

NMA‐SoF table definitions

aNegative relative effect estimates suggest that the comparator treatments outperformed the reference treatment.

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

We gave a rating of very low confidence to all the estimates of this analysis because of major concerns in 36 effect estimates in the domain 'within‐study bias' (based on the risk of bias assessments), in 28 effect estimates on the domain 'imprecision' (uncertain effect estimates with wide confidence intervals), and concerns about heterogeneity in five estimates (high variability in the results of the studies that contributed to each comparison).

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings table 2. Results of the indirect evidence for depression post‐treatment in sexually abused people under 18 years old.

| Estimates of effects, confidence intervals, and certainty of the indirect evidence for depression post‐treatment in sexually abused people under 18 years old | |||

|

Patient or population: sexually abused people under 18 years old Settings: clinical setting Interventions: WL, FT, EMDR, CCT dyad, CCT child higher, CCT child, CBT dyad higher, CBT dyad, CBT child, CBT carer Comparison (reference): MAU | |||

|

Total number of studies: 12 Total number of participants: 769 |

Relative effecta (95% CI) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Interpretation of findings |

| WL | ‐1.82 (‐5.04 to 1.40) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of WL overperforming MAU |

| FT | ‐0.42 (‐2.61 to 1.76) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of FT overperforming MAU |

| EMDR | ‐0.72 (‐3.82 to 2.37) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of EMDR overperforming MAU |

| CCT dyad | ‐0.51 (‐3.02 to 2.01) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CCT dyad overperforming MAU |

| CCT child higher | ‐1.07 (‐3.57 to 1.43) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CCT child higher overperforming MAU |

| CCT child | ‐0.88 (‐2.69 to 0.94) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CCT child overperforming MAU |

| CBT dyad higher | 0.98 (‐1.55 to 3.51) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of MAU overperforming CBT dyad higher |

| CBT dyad | 0.07 (‐2.56 to 2.69) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of MAU overperforming CBT dyad |

| CBT child | ‐0.80 (‐2.60 to 1.01) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CBT child overperforming MAU |

| CBT carer | ‐0.64 (‐2.45 to 1.17) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CBT carer overperforming MAU |

| CBT carer: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered only to the carer; CBT child: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered only to the child; CBT dyad: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered to the child and the carer; CBT dyad higher: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered to the child and the carer at a higher dose; CCT child: child‐centred therapy delivered only to the child; CCT child higher: child centred therapy delivered only to the child at a higher dose; CCT dyad: child‐centred therapy delivered to the child and the carer; CI: confidence interval; EMDR: eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing; FT: family therapy; MAU: management as usual delivered to the child and the carer; NMA: network meta‐analysis; SoF: summary of findings table; WL: waiting list | |||

NMA‐SoF table definitions

aNegative relative effect estimates suggest that the comparator treatments outperformed the reference treatment.

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

We gave a very low confidence rating for all the estimates as all had major concerns in within‐study bias and imprecision or heterogeneity.

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings table 3. Results of the indirect evidence for anxiety post‐treatment in sexually abused people under 18 years old.

| Estimates of effects, confidence intervals, and certainty of the indirect evidence for anxiety post‐treatment in sexually abused people under 18 years old | |||

|

Patient or population: sexually abused people under 18 years old Settings: clinical setting Interventions: WL EMDR, CCT dyad, CBT dyad higher, CBT dyad, CBT child, CBT carer Comparison (reference): MAU | |||

|

Total number of studies: 10 Total number of participants: 691 |

Relative effecta (95% CI) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Interpretation of findings |

| WL | 0.50 (‐2.09 to 3.09) | Very Low | Uncertain evidence of MAU overperforming WL |

| EMDR | ‐0.84 (‐2.65 to 0.97) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of EMDR overperforming MAU |

| CCT dyad | ‐0.65 (‐1.97 to 0.67) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CCT dyad overperforming MAU |

| CBT dyad higher | 0.66 (‐1.18 to 2.50) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of MAU overperforming CBT dyad higher |

| CBT dyad | 0.56 (‐1.44 to 2.55) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of MAU overperforming CBT dyad |

| CBT child | ‐0.13 (‐1.45 to 1.20) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CBT child overperforming MAU |

| CBT carer | ‐0.01 (‐1.33 to 1.31) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CBT carer overperforming MAU |

| CBT carer: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered only to the carer; CBT child: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered only to the child; CBT dyad: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered to the child and the carer; CBT dyad higher: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered to the child and the carer at a higher dose; CCT dyad: child‐centred therapy delivered to the child and the carer; CI: confidence interval; EMDR: eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing; MAU: management as usual; NMA: network meta‐analysis; SoF: summary of findings table; WL: waiting list | |||

NMA‐SoF table definitions

aNegative relative effect estimates suggest that the comparator treatments outperformed the reference treatment.

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

We gave a very low rating of confidence in the estimates of these analyses because they had major concerns in three domains: inconsistency, heterogeneity and within‐study bias.

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings table 4. Results of the indirect evidence for sexualised behaviour post‐treatment in sexually abused people under 18 years old.

| Estimates of effects, confidence intervals, and certainty of the indirect evidence for sexualised behaviour post‐treatment in sexually abused people under 18 years old | |||

|

Patient or population: sexually abused people under 18 years old Settings: clinical setting Interventions: FT, CCT dyad, CBT dyad higher, CBT dyad Comparison (reference): MAU | |||

|

Total number of studies: 7 Total number of participants: 612 |

Relative effecta (95% CI) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Interpretation of findings |

| FT | ‐0.43 (‐1.19 to 0.33) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of FT overperforming MAU |

| CCT dyad | 0.55 (‐0.02 to 1.11) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of MAU overperforming CCT dyad |

| CBT dyad higher | 0.11 (‐0.52 to 0.75) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of MAU overperforming CBT dyad higher |

| CBT dyad | 0.37 (‐0.13 to 0.87) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of MAU overperforming CBT dyad |

| CBT dyad: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered to the child and the carer; CBT dyad higher: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered to the child and the carer at a higher dose; CCT dyad: child‐centred therapy delivered to the child and the carer; CI: confidence interval; FT: family therapy; MAU: management as usual; NMA: network meta‐analysis; SoF: summary of findings table | |||

NMA‐SoF table definitions

aNegative relative effect estimates suggest that the comparator treatments outperformed the reference treatment.

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

We gave a very low confidence rating to all estimates because of major concerns regarding within‐study bias, precision and inconsistency.

Summary of findings 5. Summary of findings table 5. Results of the indirect evidence for internalising behaviour post‐treatment in sexually abused people under 18 years old.

| Estimates of effects, confidence intervals, and certainty of the indirect evidence for internalising behaviour post‐treatment in sexually abused people under 18 years old | |||

|

Patient or population: sexually abused people under 18 years old Settings: clinical setting Interventions: WL, FT, EMDR, CCY dyad, CBT dyad higher, CBT dyad, CBT child, CBT carer Comparator (reference): MAU | |||

|

Total number of studies: 11 Total number of participants: 770 |

Relative effecta (95% CI) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Interpretation of findings |

| WL | 0.22 (‐0.41 to 0.85) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of MAU overperforming WL |

| FT | ‐1.19 (‐2.54 to 0.15) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of FT overperforming MAU |

| EMDR | ‐0.39 (‐1.05 to 0.28) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of EMDR overperforming MAU |

| CCT dyad | ‐0.17 (‐0.76 to 0.42) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CCT dyad overperforming MAU |

| CBT dyad higher | 0.46 (‐0.24 to 1.17) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of MAU overperforming CBT dyad higher |

| CBT dyad | ‐0.83 (‐1.93 to 0.28) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CBT dyad overperforming MAU |

| CBT child | ‐0.37 (‐0.97 to 0.23) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CBT child overperforming MAU |

| CBT carer | ‐0.42 (‐1.03 to 0.18) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CBT carer overperforming MAU |

| CBT carer: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered only to the carer; CBT child: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered only to the child; CBT dyad: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered to the child and the carer; CBT dyad higher: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered to the child and the carer at a higher dose; CCT dyad: child centred therapy delivered to the child and the carer; CI: confidence interval; EMDR: eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing; FT: family therapy; MAU: management as usual; NMA: network meta‐analysis; SoF: summary of findings table; WL: waiting list | |||

NMA‐SoF table definitions

aNegative relative effect estimates suggest that the comparator treatments outperformed the reference treatment.

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

We gave a very low confidence rating to all the estimates of these analyses because all of them had major concerns in within‐study bias, imprecision, and some concerns regarding inconsistency.

Summary of findings 6. Summary of findings table 6. Results of the indirect evidence for externalising behaviour post‐treatment in sexually abused people under 18 years old.

| Estimates of effects, confidence intervals, and certainty of the indirect evidence for externalising behaviour post‐treatment in sexually abused people under 18 years old | |||

|

Patient or population: sexually abused people under 18 years old Settings: clinical setting Intervention: WL, FT, EMDR, CCT dyad, CBT dyad higher, CBT dyad, CBT child, CBT carer Comparator (reference): MAU | |||

|

Total number of studies: 11 Total number of participants: 749 |

Relative effecta (95% CI) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Interpretation of findings |

| WL | ‐0.01 (‐1.14 to 1.13) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of WL overperforming MAU |

| FT | ‐0.78 (‐2.68 to 1.12) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of FT overperforming MAU |

| EMDR | ‐0.35 (‐1.63 to 0.94) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of EMDR overperforming MAU |

| CCT dyad | ‐0.23 (‐1.25 to 0.79) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CCT dyad overperforming MAU |

| CBT dyad higher | 0.24 (‐0.99 to 1.47) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of MAU overperforming CBT dyad higher |

| CBT dyad | 0.10 (‐1.41 to 1.62) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of MAU overperforming CBT dyad |

| CBT child | 0.06 (‐0.95 to 1.07) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of MAU overperforming CBT child |

| CBT carer | ‐0.61 (‐1.64 to 0.41) | Very low | Uncertain evidence of CBT carer overperforming MAU |

| CBT carer: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered only to the carer; CBT child: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered only to the child; CBT dyad: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered to the child and the carer; CBT dyad higher: cognitive behavioural therapy delivered to the child and the carer at a higher dose; CCT dyad: child centred therapy delivered to the child and the carer; CI: confidence interval; EMDR: eye movement desensitization and reprocessing; FT: family therapy; MAU: management as usual; NMA: network meta‐analysis; SoF: summary of findings table; WL: waiting list | |||

NMA‐SoF table definitions

aNegative relative effect estimates suggest that the comparator treatments outperformed the reference treatment.

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

We gave a very low confidence rating to all the estimates of this analysis because all of them had major concerns about within‐study bias and imprecision.

Background

Description of the condition

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK defines child sexual abuse (CSA) as follows.

"[CSA] involves forcing or enticing a child or young person to take part in sexual activities, not necessarily involving a high level of violence, whether or not the child is aware of what is happening. The activities may involve physical contact, including assault by penetration (for example, rape or oral sex) or non‐penetrative acts such as masturbation, kissing, rubbing and touching outside of clothing. They may also include non‐contact activities, such as involving children in looking at, or in the production of, sexual images, watching sexual activities, encouraging children to behave in sexually inappropriate ways, or grooming a child in preparation for abuse (including through the Internet). Sexual abuse is not solely perpetrated by adult males. Women can also commit acts of sexual abuse, as can other children." (NICE 2017, pp 46‐7).

Child sexual exploitation is increasingly recognised as a particular form of child sexual abuse, in which an imbalance of power between a child or young person and others is used "to coerce, manipulate or deceive a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity (a) in exchange for something the victim needs or wants, and/or (b) for the financial advantage of increased status of the perpetrator or facilitator." (NICE 2017, pp 42‐3). Exploitation may occur even in circumstances where the sexual activity appears consensual, and it can occur through the medium of technology.

Prevalence

Estimates of the prevalence of CSA vary widely for a number of reasons. Definitions may differ according to the country where the problem is being studied, data may vary in their availability and quality, and there are methodological differences between studies and differences in the contexts in which victims and perpetrators live; for example, conditions of war and social unrest and injustice; low‐, middle‐ or high‐income countries (Gilbert 2009; Latzman 2017; Singh 2014).

Aiming to describe global prevalence rates of CSA, Barth 2013 conducted a meta‐analysis of studies reporting cases of four predefined types of CSA (forced intercourse, mixed sexual abuse, non‐contact abuse, and contact abuse) in children and adolescents under 18 years of age. Studies were excluded when the country was not reported (indicative of low‐quality reporting) and the sample size was smaller than 1000 (low statistical precision). The 55 included studies were published between 2002 and 2009 and covered 24 countries: 16 studies were conducted in Asia, 14 in North America, 11 in Europe, 9 in Africa and 5 in Central and South America. For girls, the review authors reported pooled prevalence rates for forced intercourse, mixed sexual abuse, non‐contact abuse and contact abuse of 9%, 15%, 31% and 13%, respectively; for boys, the figures were 3%, 8%, 17% and 6%, respectively.

Barth and colleagues also explored contextual variables (geographical region, level of development assessed using the Human Development Index (United Nations Development Programme 2009)) and methodological variables that might explain the heterogeneity of the prevalence estimates between studies (Barth 2013). The reviewers found no statistically significant differences in prevalence rates across studies conducted in different regions or degree of development of the country.

Consequences of CSA

As well as the physical and psychological trauma that may be associated with penetrative sexual abuse (e.g. vulval or anal sores, infections, higher risk of sexually transmitted diseases), children who are sexually abused are at risk of adverse effects in many areas of their development and functioning (Fisher 2017). Child sexual abuse is associated with increased risk of poor physical and mental health, impeded cognitive development, and emotional and behavioural problems. Long and intense experiences of stress during childhood disturb brain architecture, affect metabolic mechanisms and the immune system, and increase the risk of stress‐related chronic illnesses such as hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and mental ill health (Allnock 2012). Lifetime consequences can include poorer educational outcomes, low socioeconomic status, unemployment, and revictimisation (Allnock 2012; Fisher 2017; Herrmann 2014; McEwen 2007; NSCDC 2007; Woods 2005).

Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sexualised behaviour, and internalising and externalising problems are some of the most common psychological problems to affect children and young people following sexual abuse (Fergusson 1999; Harvey 2010; MacMillan 2009; Putnam 2003; Trask 2011). According to the criteria of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐5), a child meets the criteria for a PTSD diagnosis if he or she demonstrates concurrence of at least one symptom of re‐experiencing the traumatic experience, three or more symptoms of avoidant behaviours, and two or more symptoms of autonomic hyperarousal (DSM‐5). Sexualised behaviour is characterised by sexualised play with dolls, putting objects into the anus or vagina, excessive or public masturbation, seductive behaviour, requesting sexual stimulation from adults or other children, and age‐inappropriate sexual knowledge. Internalising problems include social withdrawal, depression, fearfulness, inhibition, and over‐controlled behaviour; while externalising problems include aggression, hyperactivity, and antisocial and under‐controlled behaviour (Kendall‐Tackett 1993; Trask 2011). Infants and children up to six years old are more likely to suffer anxiety, nightmares, PTSD, internalising and externalising problems and sexualised behaviours; children aged 7 to 12 years old are more likely to have school problems, hyperactivity, and aggressive and regressive behaviours; and adolescents (13 to 18 years old) are more likely to harm themselves, suffer depression, and engage in substance abuse and criminal behaviour (Kendall‐Tackett 1993).

Along with the impacts for abused children and their families, societies and governments are impacted too. In the UK, the annual cost of child sexual abuse is GBP 3.2 billion, including (in millions): child depression (GBP 1.6); child suicide (GBP 1.9); adult mental health (GBP 162.7); adult physical health, alcohol and drug misuse (GBP 15.4); criminal justice system (GBP 149); services for children (GBP 124); and productivity losses (GBP 2700) (Saied‐Tessier 2014). In Australia and the USA, the costs of child sexual abuse is included in figures for maltreatment overall. In the USA, the average cost per victim of child maltreatment in 2012 was estimated to be USD 210,200 including: childhood health care costs (USD 32,248), adult medical costs (USD 10,530), productivity losses (USD 144,360), child welfare costs (USD 7720), criminal justice costs (USD 6747) and special education costs (USD 7999) (Fang 2012). In 2016, the lifetime costs attributable to child maltreatment in Australia were estimated at AUD 17.4 billion, including (in millions): health system costs (AUD 3.301), special education costs (AUD 196.4), criminal justice system costs (AUD 904.2), child protection system (AUD 818.2), productivity losses (AUD 2529.9), loss of quality of life related to mental health (AUD 16,601.9) and premature mortality (unfulfilled life expectancy) (AUD 757.2) (McCarthy 2016).

Description of the intervention

Psychological interventions used to treat the consequences of sexual abuse amongst children and young people come from different theoretical orientations: psychodynamic or psychoanalytic, cognitive‐behavioural, systemic, humanistic, and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing theory (Sánchez‐Meca 2011). The main characteristics of interventions in these groups are described below. Treatment delivery, as well as overall suitability and accessibility, may vary according to the child's age, symptoms, severity of impairment, settings, contexts, training of therapists, availability of mental health services for victims, and other variables.

Systemic therapies

Systemic therapies view families as contexts that ameliorate or reinforce children’s response to the abuse, whether perpetrated inside or outside the family (Carr 2006; Dallos 2010). Generally, systemic therapies maintain that: (1) the children's needs should be addressed within the relational system in which they occur; (2) the system has circular and evolving patterns of behaviour; (3) beliefs and behaviours are the basis of the system's narratives; (4) the members of the system construe what happens from their own frame of reference; (5) meanings emerge from social interactions and context; (6) the therapist should adopt different stances of power with the client's family and the therapeutic relationship; (7) during the therapy, the therapist and the system construct reality; (8) the therapist should be self‐reflective on his or her own constructions; and (9) the therapists should have a positive view of the family and stress its strengths in order to work as a unit (Karakurt 2014; Lorås 2017).

Systemic therapies can be delivered in structured, strategic and social constructivist models. Each model makes different hypotheses about the roots of the family’s problems and thereby the ways in which the therapy is expected to lead to changes (Tickle 2016). However, similar treatment techniques are employed across models, including (Lorås 2017):

adaptive reframing of situations, using metaphors and externalisation of thoughts, feelings and beliefs;

creation of alternative stories of the family’s problems in which the problem is not the dominant trait of the system;

a focus on strengths and solutions: therapists encourage family members to seek change with their own resources and efforts; and

reflecting: the therapy is seen as a safe space where family members feel free to listen, acknowledge and discuss different positions.

The therapy, which can last several weeks to several months, focuses on improving the family’s functioning as a unit, and involves different elements such as psychoeducation, developing maps of family patterns, and narrative techniques (Carr 2006; Dallos 2010; Goepfert 2015; Solomon 2012; Spain 2017).

Child Centred Therapy

Child‐centred therapy emerged in the 1950s and 1960s as a response to the behavioural and psychoanalytic approaches. Humanistic theory proposed a shift from viewing a lack of free will in human actions, behaviours, cognitions and decisions, towards viewing a client capable of self‐determination. Person‐centred therapy is based on the premise that clients have an inherent tendency to develop their potential (termed 'self‐actualisation'), and regards the therapeutic relationship as curative in its own right (Rogers 1951). The manifestation of the problem in the moment and a focus on present feelings is considered the most important focus for therapy. With its fundamental postulate that play is the child’s natural medium of expression, non‐directive play therapy offers the child the opportunity to ‘play out’ their feelings, problems and difficulties, and therefore to develop a more positive image of themselves rather than relying on external ‘conditions of worth’ (Axline 1947). It is by the constant recognition and clarification of the emotions in the non‐directive (play) therapy that the child’s (or young person’s) insights into the feelings that motivate behaviour and self‐definition can emerge.

The children's free expression of themselves is facilitated by communicating three basic therapist attitudes: (1) empathy; (2) genuineness; and (3) unconditional positive regard. The primary therapeutic objective is to provide the children with the maximum opportunity to express their feelings, so that these can be recognised and clarified, and the children is eventually enabled to identify their own feelings. The treatment is delivered in individual format and the length varies on the basis of the children's needs (Cain 2016; Hofmann 2017).

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) interventions and trauma‐focused CBT (TF‐CBT)

CBT interventions are multi‐component interventions that draw primarily on cognitive theories of learning, with particular attention on how the meaning we attribute to events mediates their impact. More broadly, CBT treatments draw on a range of theories, including systems theory, social learning theory, operant and classical conditioning. Treatment is also informed by what is known about the problems it seeks to address. For example, when used in the treatment of maltreated children, therapists also draw on attachment theory and neurodevelopmental theories of trauma, as well as theories of child and adolescent development.

Trauma‐focused CBT (TF‐CBT) is one of the most widely used cognitive behavioural interventions. Developed by Esther Deblinger, Judith Cohen and Anthony Mannarino (see Cohen 2006; Deblinger 1996a), it takes the form of a sequential programme comprising three phases of similar length (see Cohen 2018 for a full description) and summarised in the acronym PRACTICE.

-

Phase 1 Stabilisation and skills enhancement. This includes:

psychoeducation about the impact of sexual abuse (giving parents and children information about sexual abuse, such as why it happens, who is affected, how children feel and the impact it can have on them and their parents), and parenting skills to help parents support their children and manage the ‘fall‐out’ that sexual abuse can have in relation to child behaviour problems;

relaxation training, to reduce and manage stress;

affective skills, to assist in managing the emotional consequences of trauma (i.e. dysregulation or difficulties to manage emotional distress); and

cognitive processing skills, to help parents and children understand the relationship between thoughts, feelings and behaviours, and to develop more accurate and helpful thoughts.

-

Phase 2

Trauma narration and processing. In this phase children and parents are helped to develop a ‘trauma narrative’ and engage in processing it cognitively.

-

Phase 3 Consolidation. This last phase encompasses:

in vivo exposure (e.g. exposure to environmental cues associated with the abuse, like sounds, smells, locations);

conjoint sessions with parents and children to improve communication, both generally and in relation to the sexual abuse; and

enhancing safety.

This structured, yet flexible, programme (e.g. if children are at risk, issues of safety may be dealt with early on in the programme) is typically delivered in 8 to 16 sessions. It may be delivered in either individual or group format, with separate sessions for carer(s) and child, combined with conjoint sessions. When implemented with young people in residential settings, the length of treatment can extend to some 25 sessions.

Psychodynamic therapies

Psychodynamic therapies encompass all forms of psychoanalysis and psychoanalytically‐derived psychotherapy. Psychoanalysis is a clinical and theoretical discipline originating from Sigmund Freud’s proposition that unconscious mental forces, called instincts or ‘instinctual drives’, motivate and shape human perceptions and behaviour (Likierman 1999). Psychoanalysis is based upon exploration of the unconscious, resulting in insights gained by the analysis of the transference relationship. ‘Transference’ refers to the patient’s unconscious motives and personality structure, as expressed in the relationship with the therapist, and can be defined as a re‐enacted memory of earlier situations, developmental stages and relationships. Unconscious traces of these memories and associated ideas and emotions are believed to shape the patient’s perception of the therapist and their behaviour towards him or her (Prochaska 1999; Shemilt 2007). Following Freud, many diverging psychodynamic theories were developed by emphasising different aspects of personal development as the core organising principles for personality and psychopathology.

Psychodynamic child psychotherapies, as modern variants of child psychoanalysis, are briefer and goal directed, incorporating a psychoanalytic understanding of pathology and its development. The primary focus of child psychotherapy is the strengthening of ego defences and the amelioration of specific symptoms or problem areas. Concurrent with individual therapy for the child, the parents or carers may be engaged in psychotherapy. Close attention is paid to contextual or environmental issues and their active modification (Harper 1995; Kegerreis 2010).

Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR)

Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) is a therapeutic intervention that was originally designed to treat psychological distress associated with trauma (Shapiro 1989). EMDR is one of only two treatments approved by NICE for symptoms of PTSD including children over five years old (NICE 2018). It is recognised by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an effective therapy for people who have experienced trauma (WHO 2013).

During EMDR a three‐pronged approach is used to engage the children with processing: i) the disturbing memory of a traumatic experience that is contributing to the present dysfunction; ii) the triggers that elicit the disturbance (present); and iii) the installation of future templates related to adequately coping with the upsetting events (future) (Shapiro 2001). These are addressed using the following eight phases (Shapiro 2015):

Phase 1 (Children's history): The clinician assesses the children's suitability for the treatment, obtains background information and identifies memory networks that would facilitate the processing of the disturbing memory.

Phase 2 (Preparation): Suitable children are explained about EMDR techniques and processes. The disturbing memory to process is identified. Self‐control techniques are taught to the children for them to use when triggers elicit the disturbing memory.

Phase 3 (Assessment): The memory of the traumatic event is accessed, and its components are disentangled by identifying the physical sensations, emotions, mental images and bad and positive beliefs associated with the memory.

Phase 4 (Desensitisation): Bilateral dual attention stimuli (e.g. eye movements) are utilised to start re‐processing of the disturbing memory.

Phase 5 (Installation): The clinician identifies a children's positive self‐believe and try to link it to positive cognitive networks and to generalise it to the memory that the client has been processing.

Phase 6 (Body scan): The children focus on processing physical discomfort associated to the traumatic event.

Phase 7 (Closure): The focus of the sessions shifts from the disturbing memory to positive memory networks.

Phase 8 (Revaluation): The clinician assesses the psychological status.

Through the bilateral stimulation techniques of EMDR, the distressing memories, sensations and feelings associated with the traumatic experience are surfaced and attempted to be eased by bringing the children to a relaxed state where they can develop coping strategies or positive beliefs about themselves.

During the EMRD session, the children are instructed to focus on recalling a traumatic memory in brief sequential doses, while simultaneously focusing on an external stimulus such as tracking the therapist’s finger being waved back and forth in front of the client in a precisely prescribed manner (though a variety of other stimuli, including hand‐tapping and audio stimulation, are often used) (Shapiro 1993; Shapiro 2007). The process of bilateral stimuli is repeated until the child consigns a positive thought in place of the older negative thought. The number of sessions depends on the severity of traumatic event and negative memories. EMDR therapy can be modified dependent upon the specific needs and developmental stage of the child or adolescent. For some children, especially very young children or those who may struggle to talk about the traumatic event, pictures can be used instead of words. In the course of EMDR therapy, unprocessed memories of traumatic experiences, stored in neural networks, become linked with the adaptively processed memories of positive experiences. This is why it is called 'reprocessing' (Shapiro 2007).

How the intervention might work

Systemic therapies

The treatment includes the following activities: the members of the family are encouraged to share the difficult thoughts and feelings they may be experiencing because of the abuse. They also are encouraged to listen to each other's beliefs and interpretations about what has occurred. Drawings of genograms (family trees) are used to identify system relationships that need to be restored; and solution‐focused ideas and coping skills are used to ease guilt and stress. The understanding of each other’s meanings and the linking of such meanings with beliefs and interpretations about the family’s problems are thought to facilitate the co‐creation of more positive interactions between family members (Lorås 2017).

Structured systemic therapies view family’s difficulties as the result of a disorganised family structure. The therapist will try to restore the system’s boundaries by questioning family members’ interpretations around the dysfunction occurring after the sexual abuse, the structure of the family and the beliefs network of the system. Strategic systemic models attribute families’ difficulties to negative interactions between the family members. The therapist will try to improve these interactions by encouraging the members of the system to assess how the problems influence the system and how each member can contribute to make things better. Social constructivist therapists will prevent the creation of these limitations by offering opportunities for open dialogue and the creation of narratives in which the family’s difficulties are shown as an opportunity for change and moving forward (Tickle 2016).

Child centred therapy

Research about how child‐centred therapy ameliorates a patient's psychological distress is scarce. From a humanistic perspective, the process of change is most accurately conceptualised as a combination of consciousness raising and corrective emotional experiencing, which occurs within the context of a genuine empathic relationship characterised by unconditional positive regard (Cain 2016; Hofmann 2017; Prochaska 1999).

Cognitive behavioural therapy interventions (CBT) and Trauma‐focused CBT (TF‐CBT)

To some extent the description of TF‐CBT provides an indication of how this intervention might work, so we expand a little on the key ‘ingredients’ in this section.

The trauma of sexual abuse, like other trauma, can profoundly and adversely impact the way that children see themselves, the world and their future. Sexual abuse can also adversely impact family cohesiveness and undermine a parent's ability to provide adequate support to affected children. CBT interventions, therefore, include strategies to support or improve family functioning and parenting capacity by addressing parental distress caused by what has happened and how the child is responding.

Psychoeducation is seen as an important component of this support, for both parents and older children, in order to make sense of why children might be thinking, feeling and behaving in particular ways (see Phase 1 of TF‐CBT above under Description of the intervention). Relaxation strategies provide a means of managing the physiological consequences of trauma.

Parenting strategies are designed to help parents managing the behaviour problems that are often associated with sexual abuse, including aggression, withdrawal, anxiety and sexualised behaviours. Teaching children to relax helps to create a context in which they can be helped to express their emotions and acquire cognitive coping skills. Both children (and parents) learn how to label the feelings associated with the abuse and to communicate them to others; they learn to identify maladaptive beliefs and attributions and replace them with those that are more accurate and effective. Depending on their age, children are taught to recognise the signs of anxiety and the internal and external factors that can trigger it, and helped to replace maladaptive responses with adaptive ones.

Unsurprisingly, children and parents may go to some lengths to avoid the reminders of what happened, which may well trigger post‐traumatic stress symptoms or anxiety, but these ‘safety behaviours’ mean that children do not learn that these ‘neutral’ or ‘now neutral’ situations are non‐threatening, and they fail to experience ‘coping’. Gradual exposure (or ‘in vivo mastery’), therefore, is an important component.

TF‐CBT incorporates a specific focus on the trauma itself. This enables the therapist to help the child identify and correct problematic assumptions and concerns that he or she might have as a result of what happened. The explicit focus on the traumatic experience(s) of sexual abuse is thought to help the child to process their experiences in ways that prevent the continuation of intrusive thoughts and flashbacks that can be triggered by current events that themselves carry no threat.

Psychodynamic therapies

In psychodynamic therapies the containment offered by a positive transference relationship with the therapist is thought to facilitate the expression of inner conflicts and the overcoming of resistance. For CSA victims, the defences available to the child to deal with abuse will depend on the maturity of the child at the time of the abuse, as well as the capacity of adults to hear and act on any disclosure. In cases where there has not been suitable intervention at the time, young people are thought to exhibit psychological symptoms and inappropriate behaviour(s), as a result of a reliance on very primitive defence mechanisms (Kegerreis 2010; Lanyado 1999).

The early stages of psychotherapy with sexually abused children focus on building basic trust. The child or young person is encouraged to express their thoughts and fantasies as they occur, and to present them in whatever way they choose (verbally or non‐verbally, or both) using toys, drawings or dramatisation (Harper 1995). While the defences that they have organised must be respected, therapists frequently use a range of psychoanalytic procedures, such as 'clarification' and 'interpretation', to help the child understand the significance of certain behaviours (Horne 1999; Kegerreis 2010). Clarifications may simply involve descriptions of the patient's behaviour or a repetition of the child's statements, to get the child to elaborate on what he or she is doing. At other times they are designed to help the child understand and label feelings of which he or she may be unaware. The technique used by most therapists is 'interpretation' of the child's play or verbal statements, designed to bring unconscious material to awareness. The therapist comments on the relationships between thoughts, feelings and behaviours, or poses tentative hypotheses regarding the 'meaning' of certain behaviours (Harper 1995; Horne 1999; Prochaska 1999).

Through the therapist’s interpretations, unhelpful (i.e. immature) defences can be noted, verbalised and slowly explored, and their meaning analysed when therapy is well established. In the last phases of therapy, the insights that have come about from interpretation of resistance and transference are 'worked through'. The gradual attainment of insight is seen to be a precursor of significant therapeutic change expressed with a strengthened and more mature ego functioning that is better able to cope with the demands of intrapsychic conflicts at the end of therapy (Harper 1995; Horne 1999; Kegerreis 2010).

Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR)

Shapiro’s adaptive information processing (AIP) model posits that mental disorders result from memories of adverse past experiences that were inadequately stored in the memory (Shapiro 2001). Memories stored in a dysfunctional manner can be understood as containing disturbing feelings, thoughts, beliefs and physical sensations that cause continued distress and that may be triggered by present life experiences. Shapiro hypothesises that EMDR therapy facilitates the accessing of the traumatic memory network, so that information processing is enhanced, with new associations forged between the traumatic memory and more adaptive memories or information (Shapiro 1993; Shapiro 2001). These new associations are thought to result in complete information processing, reformulation of associated cognitions, desensitisation of emotional distress, and relief of accompanying physiological arousal, leading to the development of cognitive insights (see Oren 2012; Shapiro 2014; Shapiro 2017).

Common factors and common elements

Although each intervention approach hypothesises a particular set of processes whereby change is brought about, some writers argue that many therapies that appear to be distinct share common elements that account for their impact; for example psychoeducation, exposure, relaxation, etc. (Barth 2012). Others argue that the effectiveness of therapeutic approaches are primarily attributable to nonspecific factors in therapy, such as the nature of the therapeutic relationship (trusting, emotionally charged); the therapeutic context, plus the client's belief that the therapist can help; a narrative that makes sense of the client's problems and a plausible means of dealing with them (see, for example, Frank 1993; Jensen 2005). This review was not designed to explore these factors, but they are discussed in relation to the findings.

Why it is important to do this review

Identifying effective treatments to treat the psychological consequences of child sexual abuse may mitigate the impact of the trauma on the lives of the abused children and youth. Previous systematic reviews assessing the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions to treat the psychological consequences of sexual abuse in children and young people have used pairwise meta‐analyses, which only compare two interventions (Benuto 2015; Corcoran 2008; Harvey 2010; Hetzel‐Riggin 2007; Macdonald 2012; Parker 2013; Reeker 1997; Sánchez‐Meca 2011; Trask 2011). Since not all therapies have been assessed in head‐to‐head comparisons, studies' conclusions may only partially yield information needed to make informed decisions (Tonin 2017).

Network meta‐analysis (NMA) allows comparison of multiple treatments, using direct comparisons of interventions within randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and indirect comparisons across trials based on a common comparator (Hindryckx 2017). NMA provides estimates of the effects of each intervention relative to every other, and allows calculation of the probability of one intervention being the best for a specific outcome (Caldwell 2010). The comparative effectiveness of psychotherapies for adults was already assessed in a previous systematic review with NMA (Wilen 2014). No NMA has been conducted to assess the relative effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions drawn from psychodynamic, cognitive behavioural, systemic and humanistic theories, compared to other treatments or no treatment controls, to overcome psychological consequences of sexual abuse in children and young people up to 18 years of age. A likely reason for this is NMA being a relatively new methodology in 2011, when the latest meta‐analyses in the field were conducted. This review aims to bridge this gap, to explore the applicability of NMA in the field and to provide an up‐to‐date account of what is known about what works for whom, for what outcomes, and under what circumstances for this group of children.

Objectives

To assess the relative effectiveness of psychological interventions compared to other treatments or no treatment controls, to overcome psychological consequences of sexual abuse in children and young people up to 18 years of age.

Secondary objectives

To rank psychotherapies according to their effectiveness.

To compare different ‘doses’ of the same intervention.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing a psychological intervention with an alternate psychological intervention, management as usual (MAU) or no treatment. Studies comparing alternative doses or formats of the same intervention were also eligible for inclusion. (See Types of interventions for more detail.)

Types of participants

We included studies with participants up to 18 years old who had experienced any form of child sexual abuse (CSA), as described above under Description of the condition.

We excluded studies with participants over the age of 18 years.

Additionally, we excluded trials in which participants who had experienced CSA had experienced physical abuse or other traumatic experiences simultaneously when: 1) separate results for participants experiencing only CSA were not reported; 2) the randomisation was not stratified by the specific type of abuse or traumatic experience; 3) the participants experiencing CSA were less than the 50% of the sample (sample would have been too small to have any statistical power); and 4) individual data were not available.

Network meta‐analysis (NMA) relies on the assumption of transitivity, which refers to a similar distribution of effect modifiers across the comparisons included in the network (Caldwell 2005; Cipriani 2013; Salanti 2012). Although the age group is broad, the age of the participants has not been found to be an effect modifier in treating the consequences of CSA. Thus, with our selection criteria, all the interventions explored in this review are legitimate alternatives for participants and therefore jointly randomisable.

Types of interventions

Interventions of direct interest

We included any psychological intervention, delivered by a trained professional in any setting or any format (individual or group), and at any ‘dose’, designed to alleviate psychological distress amongst children and young people who have experienced CSA. We a priori specified these as ‘experimental’ or ‘control’.

Experimental interventions

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT): therapist addressed negative cognitive, emotional and behavioural consequences of sexual abuse; included strategies to support or improve child and family functioning and parenting capacity by addressing parental distress caused by what had happened and how the child was responding.

Psychodynamic therapy (PST): therapist focused on the strengthening of ego defences and the amelioration of specific symptoms or problem areas.

Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR): therapist helped young person to process what had happened to them, identify (surfacing) negative cognitions associated with a traumatic incident and substitute these with a healthy, positive cognition.

Child Centred Therapy (CCT): counsellors sought to facilitate what is believed to be our inherent tendency to develop our potential (termed 'self‐actualisation’).

Family therapy (FT): therapist sought to effect changes in the family that could ameliorate the psychological distress that children experienced following abuse perpetrated either inside or outside the family.

Comparator interventions

An alternate psychological treatment: for example, CBT versus CCT or CBT versus EMDR.

Higher doses of any of the experimental interventions: measured as a greater number of intervention sessions delivered.

MAU: as defined by the trial authors.

Waiting list (WL): participants who were assessed and informed that they would receive the intervention at the end of the waiting list phase.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Psychological distress/mental health, including post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; e.g. the Children's PTSD Inventory (Saigh 2000) or the Trauma Symptoms Checklist (Briere 1989)); depression (e.g. the Children's Depression Inventory (Kovacs 1992)); anxiety (e.g. State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (Spielberger 1973)); and self‐harm (e.g. item nine on the Child Depression Inventory (CDI) (Kovacs 1992)).

Behaviour, including sexualised (e.g. the Child Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI) (Friedrich 1992a)), and internalising and externalising behaviours (e.g. the 'Externalising' subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach 1991)).

Social functioning, including attachment (e.g. the Inventory of Parents and Peer Attachment (IPPA) (Armsden 1987)).

Relationships with family and others, cognitive or academic attainment, and quality of life (e.g. the Warwick‐Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) (NHS Health Scotland 2006).

Secondary outcomes

Substance misuse (e.g. the Youth Risk Behaviour Survey (Brener 2004)).

Delinquency (e.g. the Youth Risk Behaviour Survey (Brener 2004)).

Resilience (e.g. the Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire (CASQ) (Thompson 1998)).

Carer distress and efficacy (e.g. the Revised Scale for Caregiving Self‐Efficacy (Steffen 2002)).

Rating scales

A wide range of instruments is available to measure the behavioural and psychological consequences of CSA (Deblinger 1989; DSM‐5; Kendall‐Tackett 1993; Nakamura 2009; Siddons 2004). Due to anticipated heterogeneity in the use of measurement scales across the studies, we did not prespecify a hierarchy for selection of outcomes in advance of data extraction. We included outcome data when/where instruments were reported to be reliable and valid, and either were self‐report, a relative's or assessor's reports. If an outcome was assessed using a measure with subscales, we used the total score, providing the full scale that addressed the outcome of interest. If self‐ and observer‐rated assessments were available, we gave preference to the latter. When more than one measure of the same outcome was reported in a trial, we used the data from the instrument with higher reliability, as reported by the authors of the trial. We anticipated variation in the timing of follow‐ups, so we analysed data in three categories, as per protocol (Caro 2019): short term (one to three months following therapy), medium term (four to six months following therapy), and long term (six to 12 months following therapy).

Search methods for identification of studies

We first ran the searches for this review in April 2019, and updated them in March 2020. A further update was run in November 2022 for all sources apart from AMED, which was unavailable.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases and trial registers (all years).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2022, Issue 10), in the Cochrane Library, which includes the Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Specialized Register (searched 1 November 2022).

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to October Week 4 2022).

MEDLINE Ovid In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (1946 to 1 November 2022).

MEDLINE Ovid Epub Ahead of Print (1 November 2022).

Embase Ovid (1974 to 1 November 2022).

Allied and Complementary Medicine Database Ovid (AMED; 1985 to 31 March 2020).

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to October Week 4 2022).

Child Development & Adolescent Studies EBSCOhost (1970 to 2 November 2022).

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature EBSCOhost; 1937 to 3 November 2022).

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR, 2022, Issue 11), in the Cochrane Library (searched 1 November 2022).

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‒ Science Web of Science (CPCI‐S; 1990 to 3 November 2022).

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‒ Social Science & Humanities Web of Science (CPCI‐SSH; 1990 to 3 November 2022).

SciELO Citation Index Web of Science (2002 to 3 November 2022).

Science Citation Index Web of Science (1970 to 3 November 2022).

Social Sciences Citation Index Web of Science (1970 to 3 November 2022).

ERIC EBSCOhost (Educational Resources Information Center; 1966 to 3 November 2022).

Electronic Theses Online Service, The British Library (EThOS; ethos.bl.uk/Home.do?new=1; 1800 to 4 November 2022).

Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA; current issue; www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb; searched 4 November 2022).

Epistemonikos (www.epistemonikos.org; searched 4 November 2022).

ClinicalTrials.gov (current issue; clinicaltrials.gov; searched 4 November 2022).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform; searched 4 November 2022).

The search strategy for each source can be found in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

Reference lists

We checked the references of previous reviews, meta‐analyses and included studies to identify missing studies or additional unpublished or ongoing relevant studies.

Personal communication

We contacted the authors of some of the trials to request additional trial data (Dominguez 2001; Monck 1994; Trowell 2002).

Data collection and analysis

In this section, we provide information on all methodological decisions set out in the protocol (Caro 2019) and used in this review. Appendix 2 provides information of the methods set out in our published protocol that were not applied in this, first version of the review.

Selection of studies

Working in pairs, three of the four review authors (WT, PC and GM) independently screened the titles and abstracts of studies retrieved from the searches against the selection criteria (Criteria for considering studies for this review).

We eliminated studies deemed irrelevant by both review authors. We obtained the full text of any title or abstract that one or more review author thought might be potentially eligible and assessed it against the inclusion criteria. We discussed any disagreements with the third review author (GM) and, if agreement was not reached, we sought the information necessary to resolve the issue from the study authors. We record the reasons for excluding studies in the table Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

We present our study selection process (along with the number of records and studies, and reasons for exclusion of records at screening of full‐text reports) in a PRISMA flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

PC and GM independently extracted data and entered them onto a structured, pilot‐tested Excel data collection form, which was based on the data collection form for intervention reviews for RCTs only of the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Review Group (CDPLP 2014). The form is available here.

Outcome data

From each included study, we extracted relevant details on all primary and secondary outcome measures used, as defined by the review authors, including length of follow‐up and summary data (means, standard deviations (SD), confidence intervals (CI) and significance levels for continuous data, and proportions for dichotomous data).

Data on potential effect modifiers

From each included study, we extracted data on the following characteristics that could have acted as effect modifiers.

Study characteristics (geographical location of study; study design; study duration; details of attrition; risk of bias concerns; service setting (e.g. hospital or community, research facility or community agency); whether the researchers were members of the treatment agency or independent or external; proportion of families referred or approached who agreed to be randomised; and characteristics of the therapists (e.g. discipline, level of qualification or student, years of experience)).

Participant characteristics (number randomised; nature and duration of sexual abuse, including sexual exploitation; age of participants; specific diagnosis; comorbidities; gender distribution; sexual orientation).

Intervention characteristics (intervention components; format and timing of psychological therapy; duration; frequency; concurrent interventions; whether the treatment is manualised, semi‐structured or unstructured treatment; if participants were required to attend a set number of sessions; and if participants were paid).

Comparison characteristics (format, frequency and duration).

Other data

From each included study, we extracted data on the following additional information.

Study author(s), year of publication, citation and contact details.

Sources of funding and other potential commercial interests.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

PC and WT judged the risk of bias of each of the included studies in accordance with the guidance provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017) and assigned one of the following three ratings.

High risk of bias (plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results).

Low risk of bias (plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results).

Unclear or unknown risk of bias.

We based the risk for bias assessment on the domains outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017), which are set out in Appendix 3.

Measures of treatment effect

Relative treatment effects

We estimated the pairwise relative treatment effects of the interventions by calculating effect sizes appropriate for the type of outcome data provided. All studies reported continuous outcome data and used different measures to assess the same outcome. We therefore used the standardised mean difference (SMD) with its 95% CI (Higgins 2021a).

If an outcome was assessed using a measure with subscales, we used the total score, providing the full scale that addressed the outcome of interest. In this review, negative SMDs indicated that the treatment condition (or treatment A in the head‐on analyses) was more effective (resulted in greater symptom reduction) than the treatment to which it was compared.

An SMD of 0.2 indicates a small effect, an SMD of 0.5 indicates a moderate effect, and an SMD of 0.8 indicates a large effect (Cohen 1988). We present the 95% CI in brackets for each SMD.

Endpoint versus change data

We used mean final values and not change‐from‐baseline scores for the following reasons.

Change scores do not correct pretest imbalances (Fu 2016).

Change scores can be calculated by subtracting the baseline score from the endpoint score, but standard deviations cannot be calculated this way. These would need to be imputed or approximated. When the studies’ original data are transformed, the change scores across participants are reordered and there is no way to guarantee that the transformation applies to the change score (Clifton 2019; Higgins 2021a).

SMDs from change scores are more likely to show significant results, whilst those from endpoints produce more conservative results (Fu 2016).

Most of the time, baseline and endpoints are reported for different number of participants because of withdrawals or attrition. With change scores, reviewers cannot specify the number of participants reporting baseline and endpoint scores (Higgins 2021a).

Endpoint data typically have no negative effects. This can make it easier for clinicians to interpret (Higgins 2021a).

Standard deviations from endpoint data are usually more readily reported by the authors in the studies, which facilitates the creation of a consistent dataset (Higgins 2021a).

Only one of the included studies reported change‐from‐baseline scores (Trowell 2002). We decided not to include this study in the numerical analyses for the following reasons.

Change and postintervention data cannot be combined in an SMD meta‐analysis/network meta‐analysis. Standard deviations of each data reflect different things. Postintervention scores' SDs reflect between‐person variability at a single point in time; whereas change scores' SDs reflect variation in between‐person changes over time.

To include Trowell 2002, we would have had to transform the endpoints of all the other studies to change scores. We decided not to do so. First, there was no methodological justification to transform the original data, as all the endpoints reported by the other studies were estimated using the pretest outcome measure as a covariate in the regression models (ANCOVA; analysis of covariance), which has been argued to be the preferred statistical approach to account for potential baseline imbalances and to reach precise and least biased interventions' effect estimates (Higgins 2021a). Second, switching from endpoints to changes from baselines because of an observed baseline imbalance across the studies introduces bias rather than removes it (Vickers 2001). And third, utilising change scores does not correct baseline imbalances.

Relative treatment ranking