Abstract

Background

During the novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, there was an overuse of antibiotics in hospitals. The improper use of antibiotics during COVID-19 has increased antibiotic resistance (AR), which has been reported in multiple studies.

Objectives

To assess the healthcare workers’ (HCWs) knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) in relation to AR during the era of COVID-19, and identify the associated factors with good knowledge, positive attitude and good practice.

Methods

A cross-sectional design was used to assess the KAP of HCWs in Najran, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). A validated questionnaire was used to collect participants’ data, which consisted of the following information; socio-demographics, knowledge, attitude and items for practice. Data were presented as percentages and median (IQR). Mann–Whitney and Kruskal Wallis tests were used to compare them. Logistic regression was used to identify the associated factors linked to KAP.

Results

The study included 406 HCWs. Their median (IQR) knowledge score was 72.73% (27.27%–81.82%), attitude score was 71.43% (28.57%–71.43%) and practice score was 50% (0%–66.67%). About 58.1% of the HCWs stated that antibiotics could be used to treat COVID-19 infection; 19.2% of the participants strongly agreed and 20.7% agreed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, antibiotics were overused at their healthcare institutions. Only 18.5% strongly agreed and 15.5% agreed when asked whether antibiotics used properly for the right indication and duration can still result in AR. The significantly associated factors with good knowledge were nationality, cadre and qualification. A positive attitude was significantly associated with age, nationality and qualification. Good practice was significantly associated with age, cadre, qualification and working place.

Conclusion

Although the HCWs had a positive attitude regarding AR during COVID-19, their knowledge and practice need significant improvement. Implementation of effective educational and training programmes are urgently needed. In addition, further prospective and clinical trial studies are needed to better inform these programmes.

Introduction

The ability of bacteria to resist antibiotics has been described as antibiotic resistance (AR). AR has become a global public health crisis due to misuse and overuse of antibiotics.1,2 In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic crisis,3 in which there was overuse of antibiotics in both hospitals and communities.4,5 Improper use of antibiotics during COVID-19 pandemic increased the AR and was reported globally.6–16

One of the WHO's objectives is the worldwide action plan on AR, which aims to enhance the awareness regarding this issue.17 Optimizing the use of antibiotics in healthcare can be fulfilled through holistic cooperation between all different practices. Cooperation in healthcare settings is a key to achieve such objectives. It has been found that a cooperative practice including management, responsibility, experience in drug, actions, tracking, education and reporting has reduced the relative risk of antibiotic use by 34%.18 Appropriate knowledge about bacterial resistance to antibiotics is important in preventing AR, as insufficient knowledge will drive improper use.19,20

Strategies and programmes are the key factors that help to tackle or at least reduce the issue of AR. The Antimicrobial Stewardship Program (ASP) is one of these strategies, which aims to ensure proper selection of antimicrobial prescription and optimal use of antibiotics to reduce AR through specific policies and guidelines.21 In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), the ASP was launched in 2014,19 and after 2 years, it was possible to dispense antibiotics without prescription.22,23 The implementation of ASPs showed positive consequences.24 Thus, continuous education on antibiotics is critical to accept the ASP interventions.25

Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) towards AR among healthcare workers (HCWs) is a topical matter to be explored as HCWs guide patients on using antibiotics so they should be the trusted source of information. As a result, in 2020, a study conducted in Riyadh assessing the KAP of physicians regarding ASP found that ∼56% of them identified the term of ASP and 65% knew the variation between bactericidal and bacteriostatic agents.26 It also reported that >50% of the HCWs were not aware of ASP.25 A nationwide study conducted in the KSA discovered the implementation of ASPs was ineffective and influencing factors were lack of awareness, teams of ASP, experience in the infectious diseases and technical resources.27

After a careful search, only one study was found to assess the KAP of nursing students regarding the antibiotic use and AR during COVID-19,28 and no studies studied HCWs’ KAP in general with regard to AR during COVID-19. However, most previous studies revealed a low level of knowledge of the HCWs towards AR whereas other studies reported good knowledge. While the low level of HCWs’ knowledge about AR before COVID-19 in the KSA has been reported,25,27,29–33 it is expected that the knowledge of the HCWs about AR during pandemic might be lower. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the HCWs’ KAP in relation to AR during COVID-19 period and identify influencing factors.

Materials and methods

Study design, participants and sampling methods

A cross-sectional design was used to assess the KAP of HCWs affiliated with Ministry of Health hospitals on the regional level in Najran, KSA. The Najran region is located south-west of the KSA and has a population of ∼435 000. The area is ∼365 000 km2. The eastern border of the Najran region is the desert of the Empty Quarter. On the western border is the Asir region. It borders the Riyadh region to the north and the Republic of Yemen to the south.

The participants were doctors, dentists, nurses, pharmacists and staff in the following departments: public health, infection prevention and control (IPC), laboratory, radiology, physiotherapy, respiratory therapy and operation room. Administrative staff were not included. The participants were informed about the aim and purpose of the study. Moreover, they were informed about their right to withdraw from the study at any time. Their information was confidential and private.

The overall number of employees in the region was 9331 and HCWs represented ∼6000 of this number. The sample size was 362, and then increased to 20% for non-responsive participants. Therefore, the total sample size was 435 participants. The sample size was calculated using Raosoft software (http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html).

A method of proportionate stratified random sampling was used (see Table 1). In the Najran region, KSA, there are six governmental hospitals with a 50–100-bed capacity (Khobash General Hospital, Sharorah General Hospital, Habona General Hospital, Thar General Hospital, Bader Alganoob General Hospital, Yadamah General Hospital and Psychiatric Hospital). Two hospitals had capacities of 200 (New Najran General Hospital and Maternity and Children Hospital). One hospital had a 300-bed capacity (King Khalid Hospital).

Table 1.

A proportionate stratified random sampling method for recruiting HCWs

| Hospital (governmental) | Bed capacity | Total HCWs | Sample (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Khobash General Hospital | 50 | 300 | 14 |

| Sharorah General Hospital | 100 | 1500 | 70 |

| Habona General Hospital | 70 | 400 | 19 |

| Thar General Hospital | 50 | 280 | 13 |

| Bader Alganoob General Hospital | 50 | 231 | 11 |

| Yadamah General Hospital | 50 | 300 | 14 |

| Psychiatric Hospital | 100 | 400 | 19 |

| New Najran General Hospital | 200 | 1600 | 74 |

| Maternity And Children Hospital | 200 | 2000 | 93 |

| King Khalid Hospital | 300 | 2320 | 108 |

| The total sample size | 435 | ||

Data collection and study instrument

A validated questionnaire was used to assess the KAP of HCWs towards AR. The questionnaire was based on designs from previous related studies.29,34–39 Content validity was conducted by three experts in the field independently and a few amendments were made on the basis of their suggestions. In addition, a pilot study was conducted on 30 HCWs, and a few modifications were made accordingly.

An online questionnaire in ‘Google Form’ was the method used to collect the participants’ data and this included four parts; the first part included socio-demographic and professional characteristics of the participants, the second included 11 items for evaluation of knowledge, the third included seven items for attitude and the fourth part had six items for practice. The data were collected between 5 September and 4 October 2022, and the participants spent between ∼10 and 15 minutes answering the questionnaire.

An overall score (for each on of KAP separately) was calculated on the basis of the responses of each participant to each item of KAP in the questionnaire. The overall knowledge score was 11, attitude was 7 and practice was 6. The 75th percentile was used as the cut-off point.40 Thus, scores that were above the 75th percentile of the total score for KAP indicated good knowledge, positive attitude and good practice, while scores that were below the 75th percentile indicated poor knowledge, negative attitude and poor practice.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as proportions (%) and median (IQR). Logistic regression analysis was used to identify associated variables with poor knowledge and negative attitude as well as poor practice. The included variables were age, gender, nationality, cadre, qualification and working place. In the logistic regression, univariate analysis was used first, and then significant variables were included in the multivariate analysis. SPSS v.27 was used for analysing the data.

Ethics

The ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of USM (JEPeM Code: USM/JEPeM/22040202).

Results

Of the 435 HCWs invited to participate in this study, the response rate was 406 (93.1%). Socio-demographic and professional characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 2. Median age was 37 years (IQR = 33–42 and 68.7% of the participants were male. More than 50% of the participants were Saudi and most of them were physicians (35%), whereas only 6.7% and 5.2% were dentists and IPC staff, respectively. Most of the participants had a bachelor degree (49.5%) and the fewest had a PhD (4.9%), Board (3.4%) and Fellowship (4.7). Roughly 42% of the participants worked at secondary care hospitals and 25% in tertiary care hospitals. Regarding the availability of the IPC department at the participants’ places of work, although 53.2% stated they had an ASP, 26.6% stated they did not and 20.2% said they did not know.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic and professional characteristics of the participants

| Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 37 | (33–42)a | |

| Gender | Female | 127 | 31.3 |

| Male | 279 | 68.7 | |

| Nationality | Saudi | 212 | 52.2 |

| Non-Saudi | 194 | 47.8 | |

| Cadre | Physician | 101 | 24.9 |

| Dentist | 27 | 6.7 | |

| Pharmacist | 33 | 8.1 | |

| Nurse | 142 | 35.0 | |

| IPC | 21 | 5.2 | |

| Other | 82 | 20.2 | |

| Qualification | Diploma | 93 | 22.9 |

| Bachelor | 201 | 49.5 | |

| Master | 59 | 14.5 | |

| PhD | 20 | 4.9 | |

| Board | 14 | 3.4 | |

| Fellowship | 19 | 4.7 | |

| Working Place | Primary Care | 133 | 32.8 |

| Secondary Care | 170 | 41.9 | |

| Tertiary Care | 103 | 25.4 | |

| Having ASP | Yes | 216 | 53.2 |

| No | 108 | 26.6 | |

| Do not know | 82 | 20.2 |

Interquartile range.

The median (IQR) knowledge score of the study group was 72.73% (27.27%–81.82%). Most of the participants showed good knowledge about eight questions with scores >64%. About 53% stated that antibiotics are used to treat common colds and other diseases associated with cough and fever and 58.1% stated antibiotics are used treat COVID-19 infection. However, 30.3% had insufficient knowledge regarding the frequent use of antibiotics during COVID-19 causing side effects (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Responses to questions related to knowledge about antibiotic use and AR during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In terms of the participants’ attitudes, the median (IQR) attitude score was 71.43% (28.57%–71.43%). About 18% and 14% of the participants strongly disagreed and disagreed, respectively, that antibiotics are safe drugs and can be commonly used; 19.2% of the participants strongly agreed and 20.7% agreed that they overused antibiotics during COVID-19 at their healthcare institutions. About 46% of participants strongly agreed and 20% agreed to start an antibiotic course based on the microbiology report; 47% of the participants strongly disagreed and 11.6% disagreed they could access the antibiotics during COVID-19 pandemic without prescription. Only 17% of the participants strongly disagreed and 15% disagreed that the antibiotics would accelerate recovery from COVID-19 disease. Regarding the attitudes of the participants during COVID-19 as to whether inappropriate use of antibiotics can enhance AR, 41.9% strongly agreed it could and 17.5% simply agreed. Only 39.2% of the participants strongly agreed and 23.9% agreed to receive more education on using the antibiotics (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Responses to questions related to attitude towards AR during the COVID-19 pandemic.

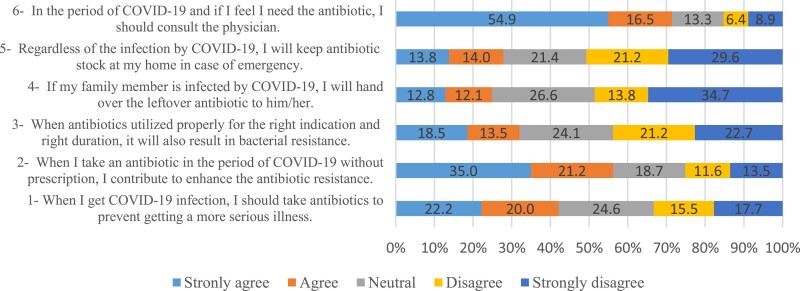

The median (IQR) practice score was 50% (0%–66.67%). Only 17.7% and 15.5% strongly disagreed and disagreed to take antibiotics when they got COVID-19 infection to prevent getting a more serious illness. Less than 56% of the participants strongly agreed and agreed that taking antibiotics without prescription would enhance AR. Only 18.5% strongly agreed and 15.5% agreed that when antibiotics are used properly, they will result in AR. Roughly 35% and 14% of the participants strongly disagreed and disagreed to share the leftover antibiotics with their families. About 13.8% and 14% of the participants strongly agreed and agreed they would keep antibiotic stock at their homes for emergency use. Nearly 55% and 17% strongly agreed and agreed to consult a physician during COVID-19 as to whether they needed antibiotics (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Responses to questions related to practice regarding AR during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Univariate analysis logistic regression for factors associated with (good knowledge, positive attitude and good practice) is presented in Table 3. The significantly associated factors with good knowledge were age, nationality, cadre, qualification and working place. Nationality, cadre and qualification were statistically significantly associated with positive attitude. With regard to factors that significantly associated good practice, these were age, gender, nationality, cadre, qualification and working place.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis for factors associated with (good knowledge, positive attitude and good practice)

| Knowledge | Attitude | Practice | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | COR | (95% CI) | P | COR | (95% CI) | P | COR | (95% CI) | P | |

| Age | 1.046 | (1.019–1.074) | 0.001* | 1.012 | (0.986–1.038) | 0.367 | 1.071 | (1.042–1.101) | 0.001* | |

| Nationality | Non-Saudi | 4.031 | (2.627–6.184) | 0.001* | 2.296 | (1.532–3.441) | 0.001* | 2.849 | (1.894–4.285) | 0.001* |

| Saudi | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Cadre | Physician | 12.020 | (5.734–25.199) | 0.001* | 3.686 | (1.975–6.878) | 0.001* | 3.460 | (1.856–6.449) | 0.001* |

| Dentist | 2.917 | (1.065–7.989) | 0.037* | 1.597 | (0.666–3.833) | 0.294 | 2.052 | (0.835–5.034) | 0.117 | |

| Pharmacist | 5.490 | (2.194–13.736) | 0.001* | 1.065 | (0.473–2.399) | 0.880 | 1.283 | (0.537–3.060) | 0.575 | |

| Nurse | 2.056 | (1.003–4.214) | 0.049* | 1.649 | (0.053–2.852) | 0.074 | 1.574 | (0.873–2.837) | 0.131 | |

| IPC | 6.417 | (2.238–18.388) | 0.001* | 2.076 | (0.777–5.548) | 0.145 | 2.822 | (1.056–7.538) | 0.039* | |

| Other | Ref. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Qualification | Fellowship | 14.625 | (4.669–45.803) | 0.001* | 4.000 | (1.235–12.959) | 0.021* | 5.532 | (1.941–15.773) | 0.001* |

| Board | 9.000 | (2.657–30.479) | 0.001* | 6.400 | (1.357–30.190) | 0.019* | 4.303 | (1.347–13.747) | 0.014 | |

| PhD | 38.250 | (9.729–150.368) | 0.001* | 6.044 | (1.659–22.024) | 0.006* | 9.682 | (3.161–29.656) | 0.001* | |

| Master | 7.473 | (3.381–16.514) | 0.001* | 2.080 | (1.059–4.086) | 0.034* | 4.706 | (2.323–9.535) | 0.001* | |

| Bachelor | 3.767 | (1.925–7.372) | 0.001* | 1.190 | (0.728–1.947) | 0.488 | 2.004 | (1.941–15.773) | 0.014* | |

| Diploma | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Working Place | Tertiary Care | 2.642 | (1.530–4.561) | 0.001* | 1.218 | (0.725–2.048) | 0.456 | 2.398 | (1.410–4.078) | 0.001* |

| Secondary Care | 1.867 | (1.140–3.056) | 0.013* | 1.342 | (0.848–2.124) | 0.209 | 1.501 | (0.934–2.412) | 0.093 | |

| Primary Care | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

Significant at P = 0.05.

COR: Crude odds ratio

Multivariate analysis for factors associated with good knowledge, positive attitude and good practice is presented in Table 4. The significantly associated factors with good knowledge were nationality, cadre and qualification. Age, nationality and qualification were the significant associated factors with positive attitude. The significantly associated factors with good practice were age, cadre, qualification and working place.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis for factors associated with overall scores (good knowledge, positive attitude and good practice)

| Knowledge | Attitude | Practice | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | AOR | (95% CI) | P | AOR | (95% CI) | P | AOR | (95% CI) | P | |

| Age | 0.992 | (0.957–1.027) | 0.641 | 0.965 | (0.934–0.996) | 0.030* | 1.051 | (1.016–1.087) | 0.004* | |

| Nationality | Non-Saudi | 3.656 | (1.836–7.282) | 0.001* | 2.088 | (1.161–3.754) | 0.014* | 1.790 | (0.502–2.407) | 0.812 |

| Saudi | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Cadre | Physician | 6.303 | (2.554–15.556) | 0.001* | 2.129 | (0.939–4.353) | 0.262 | 1.801 | (1.008–5.112) | 0.048* |

| Dentist | 2.300 | (0.741–7.137) | 0.149 | 1.103 | (0.413–2.941) | 0.845 | 1.512 | (0.562–4.067) | 0.413 | |

| Pharmacist | 9.543 | (3.367–27.050) | 0.001* | 1.048 | (0.453–2.425) | 0.913 | 1.555 | (0.606–3.989) | 0.359 | |

| Nurse | 1.645 | (0.670–4.039) | 0.277 | 1.361 | (0.714–2.595) | 0.349 | 1.649 | (0.796–3.415) | 0.178 | |

| IPC | 8.159 | (2.546–26.144) | 0.001* | 2.342 | (0.846–6.487) | 0.102 | 2.912 | (1.031–8.493) | 0.047 | |

| Other | Ref. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Qualification | Fellowship | 2.703 | (0.691–10.580) | 0.153 | 2.110 | (0.543–8.192) | 0.281 | 1.829 | (0.524–6.379) | 0.344 |

| Board | 5.740 | (1.314–25.071) | 0.020* | 5.756 | (1.085–30.529) | 0.044* | 2.703 | (0.729–10.021) | 0.137 | |

| PhD | 13.580 | (2.630–70.113) | 0.002* | 3.986 | (0.974–16.317) | 0.055 | 4.565 | (1.272–16.381) | 0.020* | |

| Master | 4.261 | (1.662–10.928) | 0.003* | 1.622 | (0.750–3.505) | 0.219 | 3.725 | (1.644–8.438) | 0.002* | |

| Bachelor | 1.960 | (0.885–4.342) | 0.097 | 0.704 | (0.387–1.279) | 0.249 | 1.628 | (0.834–3.178) | 0.153 | |

| Diploma | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Working Place | Tertiary Care | 2.330 | (1.212–4.478) | 0.011* | 1.075 | (0.611–1.890) | 0.802 | 1.971 | (1.096–3.544) | 0.024* |

| Secondary Care | 1.178 | (0.652–2.128) | 0.587 | 1.183 | (0.720–1.944) | 0.507 | 1.067 | (0.629–1.811) | 0.810 | |

| Primary Care | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

Significant at P = 0.05.

AOR: Adjusted odds ratio.

Non-Saudi participants were 3.6 times more likely to have good knowledge compared to Saudi participants (AOR = 3.65, CI = 1.836–7.282, P = 0.001). Compared with other specialities, pharmacists and IPC staff were nine and eight times more likely to have good knowledge, respectively: (AOR = 9.543, CI = 3.367–27.050, P = 0.001) and (AOR = 8.159, CI = 2.546–26.144, P = 0.001), respectively. Participants who had a PhD degree were 13.5 times more likely to have good knowledge than those who had a diploma degree (AOR = 13.580, CI = 2.630–70.113, P = 0.002). Compared with participants who worked in primary care, HCWs who worked in tertiary care were 2.3 times more likely to have good knowledge (AOR = 2.330, CI = 1.212–4.478, P = 0.011).

As age increased by 1 year, the odds of having a positive attitude increased by 49% (AOR = 1.051, CI = 1.016–1.087, P = 0.004). Non-Saudi participants were twice as likely to have a positive attitude compared to Saudi participants (AOR = 3.65, CI = 1.836–7.282, P = 0.001). Participants who hold -the board degree were 5.7 times more likely to have a positive attitude than those who had a diploma degree (AOR = 5.756, CI = 1.085–30.529, P = 0.044).

As age increased by 1 year, the odds of showing good practice decreased by 4% (AOR = 0.965, CI = 0.934–0.996, P = 0.030). Being a member of IPC staff lead to participants being 2.9 times more likely to showing good practice than participants with other specialties (AOR = 2.912, CI = 1.031–8.493, P = 0.047). Compared with participants who had a diploma, staff who had a PhD and masters degree were 4.5 and 3.7 times more likely to demonstrate good practice, respectively (AOR = 4.565, CI = 1.272–16.381, P = 0.020) and (AOR = 3.725, CI = 1.644–8.438, P = 0.002), respectively. Compared with participants who work in primary care, those who work in tertiary care were 1.9 times more likely to show good practice (AOR = 1.971, CI = 1.096–3.544, P = 0.024).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in the Arab countries that focuses on the assessment of the HCWs’ KAP towards AR during COVID-19 pandemic. The study participants showed poor knowledge and practice, however, their attitude was positive. Such findings reflected a lack of efficacious educational and training programmes. Furthermore, this study identified some HCWs who need improvement in their knowledge and practice towards AR, especially during the pandemic. This includes youths, Saudi HCWs, health practitioners (such as dentists, nurses, public health officer, laboratory personnel, radiology personnel, physiotherapy personnel, respiratory therapy personnel and operation room personnel), HCWs who hold higher-level qualifications (diploma and bachelor) and HCWs who work at primary and secondary healthcare centres.

Knowledge-related questions

In the current study, the median (IQR) score knowledge of the HCWs was 72.73% (27.27%–81.82%). Recently, a study in Jeddah, KSA, has reported the median (IQR) score knowledge among primary healthcare physicians about antibiotic use was 63.64 (45.45–81.82).41 In Pakistan, clinician’s knowledge about ASP and AR was relatively poor.42 In Najran, KSA, similar findings were also reported among HCWs regarding the COVID-19 pandemic.43 In contrast, in Egypt, the mean (standard deviation) of physicians’ knowledge towards antibiotics was 8.65 (±1.69) out of 11.44

In the current study, most of the participants showed good knowledge on eight questions related to knowledge questions at >64%. However, ∼53% stated that antibiotics are used to treat common colds and any disease related to cough and fever. This is congruent with a study conducted in Norway45 and another study in Saudi Arabia.46 COVID-19 is a viral infection and WHO strongly do not recommend using antibiotics as prophylaxis or therapy for mild or moderate COVID-19 unless there is a strong justification.47 In the current study, 58.1% of the participants stated that antibiotics are used to treat COVID-19 infection. However, 24% of HCWs in Gambia and 6.5% of medical students in Zambia stated that antibiotics could cure viral infections.33,39

Attitude-related questions

The attitude of the HCWs in the current study was positive, which was in line with two previous studies carried out in the KSA and Zambia.39,46 However, the attitude of HCWs in Ethiopia was lax.41 A small percentage of the participants in the current study strongly agreed and agreed with the statement ‘The antibiotics are safe drugs; hence, during a pandemic, can they be commonly used.’, which is similar to the other studies.38,48 About 19.2% of the participants in the current study strongly agreed and 15.5% disagreed that during the COVID-19 pandemic antibiotics were being overused at their healthcare institution. The findings in the study by Tegagn et al.36 agreed with our findings.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, physicians had prescribed antibiotics for COVID-19 patients in cases where most of the patients did not have secondary bacterial infection or a positive bacterial culture.4,5 Less than half of the current study’s participants strongly agreed and agreed to obtain culture and sensitivity reports before starting an antibiotic course. On the other hand, a study conducted by Chandan et al.38 found ∼77% of the study participants strongly agreed and agreed to obtain culture and sensitivity reports before starting an antibiotic course. In our study, 24.4% of the participants agreed to access antibiotics during the COVID-19 pandemic with a physician’s prescription. On the contrary, 43% of the international students in Africa agreed to get a prescription before starting antibiotics.49 In the present study, only 17% of the participants strongly disagreed and 15% disagreed that the antibiotics will accelerate the recovery of COVID disease. In contrast, another study reported that 50% of the respondents stated using antibiotics will speed up recovery from colds.39 Also, 75.9% of the HCWs in Gambia agreed that antibiotics will not speed up the recovery from colds and coughs.33 In line with previous studies that reported most of their healthcare providers (>90%) stated that the improper use of antibiotics can influence the AR,33,44 60% of HCWs in the current study reported correctly. Although the HCWs in the current study showed a negative attitude, only 39.2% of the participants strongly agreed and 23.9% agreed to get more education on adequate use of antibiotics. This was different from high proportions of participants in the other studies who were highly recommended to get more education.33,36,37

Practice-related questions

Responses of the participants in the current study to questions related to practice indicated a poor result. Interestingly, only 17.7% and 15.5% strongly disagreed and disagreed to take antibiotics when they get COVID-19 infection to prevent getting more serious illnesses, which agrees with a recent study in Saudi Arabia.29 HOwever, a study in Colombia revealed ∼5% of medical students stated that when they have cold, they should take antibiotics to prevent occurring serious ailments.50

About half of the participants in the current study strongly agreed and agreed that when they take antibiotics in the period of COVID-19 without prescription, they enhance the AR. Unfortunately, only 22.7% strongly disagreed and 21.2% disagreed that when antibiotics are used properly for the right indications and duration, this will result in bacterial resistance. Similarly, in Malaysia, ∼40% of public indicated poor practice towards the statement ‘Misuse of antibiotics will accelerate the AR process’.37 On the contrary, >90% of physicians in Egypt reported that inappropriate antibiotic selection, antibiotic self-medication and inappropriate duration of antibiotic drugs contributed to AR.44

Roughly 35% and 14% of the participants in the current study strongly disagreed and disagreed to hand over their leftover antibiotics to family members, and 27.8% agreed to keep an antibiotic stock at their home in case of emergency. Although the HCWs in the current study indicated overall poor practice, the majority (72%) stated they should consult physicians if they felt they needed antibiotics during COVID-19. This is in line with previous studies.46–49

Factors associated with good knowledge, positive attitude and good practice

The current study identified the significantly associated factors with good knowledge, which were nationality, cadre, qualification and working place. A study conducted during COVID-19 in the KSA found the profession and educational level were the associated factors with HCWs’ knowledge about COVID-19.43 On the other hand, a previous study reported that the higher knowledge among health professionals was associated with more working experience and fewer working hours.51 Furthermore, the current study identified the associated factors with positive attitude, including, age, nationality and qualification. In Ethiopia, educational status and level of experience were associated with the attitude of the HCWs on hospital-acquired infection.52 However, a study carried out during COVID-19 did not reveal an association between nursing students’ attitudes towards AR and demographic characteristics.28 Regarding the associated factors with good practice, in the current study the related factors were age, cadre, qualification and working place. In contrast, a previous study stated that the practice score of nursing students regarding AR and antibiotic use was associated with IPC training. However, the study did not find an association with other variables such as gender and experience.28

The current study has several strengths. First, this is the first study at the level of Arab countries focusing on the assessment of KAP of HCWs towards AR, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, the study represents the KAP of HCWs towards AR during COVID-19 who worked in governmental hospitals in the entire governorate. Third, a proportionate sampling method was used to avoid misclassification bias. Finally, associated factors with the KAP of HCWs were identified throughout using univariate and multivariate analyses. Nevertheless, the study has a few limitations. First, generalizability of the findings to all the HCWs in the KSA is not possible because it covers only one city in the southern region of the kingdom. Moreover, there are about three private hospitals that were not included in the current study.

Conclusion

The current study showed the poor knowledge, positive attitude and poor practice of HCWs. The associated factors with KAP were age, nationality, cadre, qualification and work place. A lack of efficacious educational and training programmes contributes to exacerbate the problem of AR. Therefore, implementation of effective educational and training programmes is urgently needed. In addition, further prospective and clinical trial studies are highly recommended to better inform these programmes. Furthermore, HCWs who might get benefits from the interventional programmes were identified in this study.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for study participants as well as all hospitals directors for facilitating the dissemination of the questionnaire and encouraging their staff to participate in this study.

Contributor Information

Hadi Al Sulayyim, Interdisciplinary Health Unit, School of Health Science, Universiti Sains Malaysia (Health Campus), Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, Malaysia; Saudi Ministry of Health, Najran, Saudi Arabia Affiliation.

Rohani Ismail, Interdisciplinary Health Unit, School of Health Science, Universiti Sains Malaysia (Health Campus), Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, Malaysia.

Abdullah Al Hamid, Saudi Ministry of Health, Najran, Saudi Arabia Affiliation.

Noraini Abdul Ghafar, Biomedicine Program, School of Health Science, Universiti Sains Malaysia (Health Campus), Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, Malaysia.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest in the current study.

Funding

This study was conducted as part of main’s author PhD work.

Transparency declarations

None to declare

References

- 1. WHO . Antibiotic resistance. 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance

- 2. Ventola CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2015; 40: 277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO . WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. 2022. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020

- 4. Emmanuel D, Caméléna F, Deniau Bet al. Bacterial pneumonia in COVID-19 critically ill patients: a case series. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72: 905–6. 10.1093/cid/ciaa762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YMet al. Surviving sepsis campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 854–87. 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Elsayed AA, Darwish SF, Zewail MBet al. Antibiotic misuse and compliance with infection control measures during COVID-19 pandemic in community pharmacies in Egypt. Int J Clin Pract 2021; 75: 1–11. 10.1111/ijcp.14081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tiri B, Sensi E, Marsiliani Vet al. Antimicrobial stewardship program, COVID-19, and infection control: spread of carbapenem-resistant klebsiella pneumoniae colonization in ICU COVID-19 patients. What did not work? J Clin Med 2020; 9: 1–9. 10.3390/jcm9092744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sharifipour E, Shams S, Esmkhani Met al. Evaluation of bacterial co-infections of the respiratory tract in COVID-19 patients admitted to ICU. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 1–7. 10.1186/s12879-020-05374-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li J, Wang J, Yang Yet al. Etiology and antimicrobial resistance of secondary bacterial infections in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2020; 9: 1–7. 10.1186/s13756-020-00819-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gomez-Simmonds A, Annavajhala MK, McConville THet al. Carbapenemase-producing enterobacterales causing secondary infections during the COVID-19 crisis at a New York city hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021; 76: 380–4. 10.1093/jac/dkaa466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sang L, Xi Y, Lin Zet al. Secondary infection in severe and critical covid-19 patients in China: a multicenter retrospective study. Ann Palliat Med 2021; 10: 8557–70. 10.21037/apm-21-833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Despotovic A, Milosevic B, Cirkovic Aet al. The impact of covid-19 on the profile of hospital-acquired infections in adult intensive care units. Antibiotics 2021; 10: 1–17. 10.3390/antibiotics10101146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caruso P, Maiorino MI, Macera Met al. Antibiotic resistance in diabetic foot infection: how it changed with COVID-19 pandemic in a tertiary care center. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2021; 175: 108797. 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wardoyo EH, Suardana IW, Yasa IWPSet al. Antibiotics susceptibility of Escherichia coli isolates from clinical specimens before and during COVID-19 pandemic. Iran J Microbiol 2021; 13: 156–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Temperoni C, Caiazzo L, Barchiesi F. High prevalence of antibiotic resistance among opportunistic pathogens isolated from patients with COVID-19 under mechanical ventilation: results of a single-center study. Antibiotics 2021; 10: 1080. 10.3390/antibiotics10091080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Al Sulayyim H, Ismail R, Hamid Aet al. Antibiotic resistance during COVID-19: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19: 11931. 10.3390/ijerph191911931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. WHO . Antimicrobial resistance: Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. 2021. http://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/drug-resistance/global-action-plan.html

- 18. Dukhovny D, Buus-Frank ME, Edwards EMet al. A collaborative multicenter QI initiative to improve antibiotic stewardship in newborns. Pediatrics 2019; 1: 144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Azevedo MM, Pinheiro C, Yaphe Jet al. Portuguese students’ knowledge of antibiotics: a cross-sectional study of secondary school and university students in Braga. BMC Public Health 2009; 9: 1–6. 10.1186/1471-2458-9-359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gajdács M, Paulik E, Szabó A. Public knowledge, attitude and practices towards antibiotics and antibiotic resistance: a cross-sectional study in Szeged District, Hungary. Acta Pharm Hung 2020; 90: 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alomi YA. National antimicrobial stewardship program in Saudi Arabia; initiative and the future. Open Access J Surg 2017; 4: 1–7. 10.19080/OAJS.2017.04.555646 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shibl AM, Memish ZA, Kambal AMet al. National surveillance of antimicrobial resistance among gram-positive bacteria in Saudi Arabia. J Chemother 2014; 26: 13–8. 10.1179/1973947813Y.0000000084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aljadhey H, Assiri GA, Mahmoud MAet al. Self-medication in central Saudi Arabia: community pharmacy consumers’ perspectives. Saudi Med J 2015; 36: 328. 10.15537/smj.2015.3.10523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Enani MA. The Antimicrobial Stewardship Program in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states: insights from a regional survey. J Infect Prev 2016; 17: 16–20. 10.1177/1757177415611220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Baraka MA, Alsultan H, Alsalman Tet al. Health care providers’ perceptions regarding antimicrobial stewardship programs (AMS) implementation—facilitators and challenges: a cross-sectional study in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2019; 18: 1–10. 10.1186/s12941-019-0325-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Almutiri AH, Mohd AB, Al Rahbeni TM. View of antimicrobial-stewardship knowledge, attitude, and practice among professional physicians in Saudi hospitals. Int J Res Pharm Sci 2020; 11: 5665–73. 10.26452/ijrps.v11i4.3208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alghamdi S, Berrou I, Aslanpour Zet al. Antimicrobial stewardship programmes in Saudi hospitals: evidence from a national survey. Antibiotics 2021; 10: 193. 10.3390/antibiotics10020193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jainlabdin MH, Mohd Zainuddin ND, Mohamed Ghazali SA. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance during the COVID-19 pandemic among nursing school students – a cross-sectional study. Int J Care Scholars 2021; 4: 30–9. 10.31436/ijcs.v4i2.196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alnasser AHA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Ahmed HAAet al. Public knowledge, attitude and practice towards antibiotics use and antimicrobial resistance in Saudi Arabia: a web-based cross-sectional survey. J Public Health Res 2021; 10: 2276. 10.4081/jphr.2021.2276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bahlas R, Ramadan I, Bahlas Aet al. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards the use of antibiotics. Life Sci J 2016; 13: 13. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alfalah AM, Alghamdi HA, Alghamdi AAet al. Knowledge and attitude toward antibiotics among the Saudi population. Int J Med Dev Ctries 2020; 4: 038–042. 10.24911/IJMDC.51-1569002779 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yezli S, Yassin Y, Mushi Aet al. Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) survey regarding antibiotic use among pilgrims attending the 2015 Hajj mass gathering. Travel Med Infect Dis 2019; 28: 52–8. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sanneh B, Jallow HS, Singhateh Yet al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of health care workers on antibiotic resistance and usage in the Gambia. GSC Biol Pharm Sci 2020; 13: 007–15. 10.30574/gscbps.2020.13.2.0177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Firouzabadi D, Mahmoudi L. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of health care workers towards antibiotic resistance and antimicrobial stewardship programmes: a cross-sectional study. J Eval Clin Pract 2020; 26: 190–6. 10.1111/jep.13177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. El Sherbiny NA, Ibrahim EH, Masoud M. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and behavior towards antibiotic use in primary health care patients in Fayoum Governorate, Egypt. Alexandria J Med 2018; 54: 535–40. 10.1016/j.ajme.2018.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tegagn GT, Yadesa TM, Ahmed Y. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of healthcare professionals towards antimicrobial stewardship and their predictors in Fitche Hospital. J Bioanal Biomed 2017; 09: 91–7. 10.4172/1948-593X.1000159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chang CT, Lee M, Lee JCYet al. Public KAP towards COVID-19 and antibiotics resistance: a Malaysian survey of knowledge and awareness. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 3964. 10.3390/ijerph18083964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chandan NG, Nagabushan H. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice of interns towards antibiotic resistance and its prescription in a teaching hospital: a cross-sectional study. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol 2016; 5: 442–6. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zulu A, Matafwali SK, Banda Met al. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practices on antibiotic resistance among undergraduate medical students in the school of medicine at the University of Zambia. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol 2020; 9: 263–70. 10.18203/2319-2003.ijbcp20200174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rivera-Lozada O, Galvez CA, Castro-Alzate Eet al. Factors associated with knowledge, attitudes and preventive practices towards COVID-19 in health care professionals in Lima, Peru. F1000Res 2021; 10: 582. 10.12688/f1000research.53689.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Althagafi1 NS, Othman SS. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of antibiotics use among primary healthcare physicians, ministry of health, Jeddah. J Family Med Prim Care 2022; 11: 4382–8. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_60_22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ashraf S, Ashraf S, Ashraf Met al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of clinicians about antimicrobial stewardship and resistance among hospitals of Pakistan: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022; 29: 8382–92. 10.1007/s11356-021-16178-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Al Sulayyim HJ, Al-Noaemi MC, Rajab SMet al. An assessment of healthcare workers knowledge about COVID-19. Open J Epidemiol 2020; 10: 220–34. 10.4236/ojepi.2020.103020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Abdel Wahed WY, Ahmed EI, Hassan SKet al. Physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice concerning antimicrobial resistance & prescribing: a survey in Fayoum Governorate, Egypt. J Public Health (Germany) 2020; 28: 429–36. 10.1007/s10389-019-01027-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Waaseth M, Adan A, Røen ILet al. Knowledge of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance among Norwegian pharmacy customers - a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2019; 19: 1–12. 10.1186/s12889-019-6409-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Alkhalifah1 HM, Alkhalifah2 KM, Alharthi1 AFet al. Knowledge, attitude and practices towards antibiotic use among patients attending Al Wazarat Health Center. J Family Med Prim Care 2022; 11: 1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. WHO . Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public: Mythbusters. 2022. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters? gclid=CjwKCAjwh4ObBhAzEiwAHzZYU9k9PoXXU8kitMsXQ4aQfoQiwAdjE_KT_ivF48xLYkGI8BNFeEdkohoCIBgQAvD_BwE#antibiotics

- 48. Nepal A, Hendrie D, Robinson Set al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices relating to antibiotic use among community members of the Rupandehi district in Nepal. BMC Public Health 2019; 19: 1–12. 10.1186/s12889-019-7924-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sa’adatu Sunusi L, Mohamed Awad M, Makinga Hassan Net al. Assessment of knowledge and attitude toward antibiotic use and resistance among students of international university of Africa, medical complex. Sudan. Glob Drugs Ther 2019; 4: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Higuita-Gutiérrez LF, Roncancio Villamil GE, Jiménez Quiceno JN. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding antibiotic use and resistance among medical students in Colombia: a cross-sectional descriptive study. BMC Public Health 2020; 20: 1–12. 10.1186/s12889-020-09971-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Simegn W, Dagnew B, Weldegerima Bet al. Knowledge of antimicrobial resistance and associated factors among health professionals at the University of Gondar specialized hospital: institution-based cross-sectional study. Front Public Health 2022; 10: 1–7. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.790892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bayleyegn B, Mehari A, Damtie Det al. Knowledge, attitude and practice on hospital-acquired infection prevention and associated factors among healthcare workers at University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital, northwest Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist 2021; 14: 259–66. 10.2147/IDR.S290992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]