Abstract

Aims:

Cadmium exposure is a worldwide problem that has been linked to the development of cardiovascular disease. This study aimed to elucidate mechanistic details of chronic cadmium exposure on the structure and function of the heart.

Main Methods:

Male and female mice were exposed to cadmium chloride (CdCl2) via drinking water for eight weeks. Serial echocardiography and blood pressure measurements were performed. Markers of hypertrophy and fibrosis were assessed, along with molecular targets of Ca2+-handling.

Key Findings:

Males exhibited a significant reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction and fractional shortening with CdCl2 exposure, along with increased ventricular volume at end-systole, and decreased interventricular septal thickness at end-systole. Interestingly, no changes were detected in females. Experiments in isolated cardiomyocytes revealed that CdCl2-induced contractile dysfunction was also present at the cellular level, showing decreased Ca2+ transient and sarcomere shortening amplitude with CdCl2 exposure. Further mechanistic investigation uncovered a decrease in sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a (SERCA2a) protein expression and phosphorylated phospholamban levels in male hearts with CdCl2 exposure.

Significance:

The findings of our novel study provide important insight into how cadmium exposure may act as a sex-specific driver of cardiovascular disease, and further underscore the importance of reducing human exposure to cadmium.

Keywords: Cadmium, cardiovascular disease, heart function, sex-dependent

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of death in the United States and throughout many parts of the world [1, 2]. The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association routinely highlight guidelines on the management of modifiable risk factors for CVD, such as routine physical activity, limiting tobacco use, and consuming a balanced diet. However, even with effective maintenance of these risk factors, CVD prevalence remains high. This suggests that factors beyond those that are modifiable may influence CVD development [3]. Indeed, recent studies suggest an association between exposure to toxic substances in the environment (i.e., air pollution, metals) and the development of CVD [4].

Environmental metals are a primary concern, and growing evidence suggests that exposure to certain metals is strongly associated with adverse CVD outcomes [4]. Cadmium, in particular, has recently emerged as a major cardiotoxicant [5]. Cadmium is naturally found in the Earth’s crust, and is mobilized into food, water, and air as a byproduct of mining, fertilizer application, car exhaust, waste management and as an additive in many consumer products [6]. Cadmium is listed seventh on the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry’s Substance Priority List based on its frequency of occurrence, toxicological profile and potential for human exposure [6], thereby posing a significant threat to public health.

An abundance of epidemiological findings suggest that cadmium is a potential driver of CVD development. These studies report an association between cadmium exposure and hypertension [7], coronary heart disease [8], myocardial infarction [9], left ventricular dysfunction [10] and heart failure [11]. Despite the growing literature supporting an association between cadmium exposure and CVD, mechanistic studies are lacking. In the present study, we sought to bridge this gap by enhancing our understanding of the cardiotoxic effects of cadmium. Male and female C57Bl/6J mice were exposed to cadmium chloride (CdCl2) via drinking water for eight weeks. We report here for the first time that male mice exposed to CdCl2 demonstrate impaired left ventricular function in vivo, altered Ca2+-handling and cell shortening in isolated cardiomyocytes, and decreased sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA2a) expression in the heart, while female mice remain largely protected against the cardiotoxic effects of an eight-week cadmium exposure.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Animals and Cadmium Exposure Protocol:

Male and female C57Bl/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and were seven weeks of age upon arrival. Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions and maintained on AIN-93G chow (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) and Nestle Pure Life water (Nestle Waters North America, Stamford, CT) for one week before CdCl2 exposure. Both the water and chow were reported to have undetectable cadmium levels [12]. The water was confirmed to have a cadmium concentration less than the limit of detection using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS; Agilent 7500ce Octopole; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) as previously described [13].

Following a pre-exposure period of one week, mice were given drinking water containing 0 or 5 mg/L of CdCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) ad libitum for eight weeks. Total cadmium levels were assessed in drinking water using ICP-MS and determined to be 3.3 mg/L. AIN-93 chow and water were refreshed three times per week to minimize oxidation, and cages and bedding were changed weekly. Body weight was measured weekly, and food and water intake were measured three times per week throughout the exposure. No significant changes were observed in these parameters with CdCl2 exposure in either sex (Supplemental Figure 1). CdCl2 exposure was confirmed using ICP-MS by the detection of cadmium in the urine of CdCl2-exposed mice, or lack thereof in non-exposed controls. Prior to all subsequent procedures, mice were anesthetized with a mixture of 90 mg/kg ketamine (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL), 10 mg/kg xylazine (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mL 0.9% sodium chloride solution (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL). Anesthesia was confirmed by testing for the loss of the pedal reflex with a toe pinch. All animal work performed in this study conformed with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments guidelines, the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH; Publication No. 85–23, Revised 2011) and was approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee of Johns Hopkins University.

Transthoracic Echocardiography:

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed by an investigator blinded to experimental conditions as previously described [13, 14]. Briefly, echocardiography was performed in conscious mice using a preclinical ultrasound imaging system (Vevo 2100; FUJIFILM VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada) with a 40-MHz linear transducer. The M-mode echocardiogram was acquired from the short-axis view of the left ventricle at the level of the mid-papillary muscles (200 m/s sweep speed). Semi-automated continuous tracing of the left ventricular walls from this axis view was used to measure, calculate, or extrapolate the following cardiac parameters: interventricular septum thickness at end diastole (IVS;d) and end systole (IVS;s), left ventricular internal dimension at end diastole (LVID;d) and end systole (LVID;s), left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end diastole (LVPW;d) and end systole (LVPW;s), ejection fraction (EF), fractional shortening (FS), left ventricular mass (LV Mass), left ventricular volume at end diastole (LV Volume;d) and end systole (LV Volume;s), stroke volume (SV), cardiac output (CO), and heart rate (HR).

Blood Pressure Analysis:

Systolic blood pressure was measured using a tail-cuff pressure transduction apparatus (BP-2000 Blood Pressure Analysis System; Visitech Systems, Apex, NC) as previously described [14]. Briefly, mice were acclimated to the tail-cuff pressure transduction apparatus for one week before the onset of exposure. For data collection, mice were restrained using opaque, open-bottomed rodent holders (BP-MH0; Visitech Systems) that facilitated breathing and limited light exposure to calm the animal and reduce stress. The platform was preheated and maintained at 38°C in the dark under a laminar flow hood, and the tails were secured to the platform with surgical tape to minimize movement. Five preliminary measurements were collected for each session to allow for the mouse to acclimate, prior to the 20–25 experimental measurements. Measurements were taken twice per week at the same time of day throughout the exposure, and weekly averages were utilized.

Langendorff Heart Perfusion:

Mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine via intraperitoneal injection and anticoagulated with heparin (Fresenvis Kabi, Lake Zurich, IL). Hearts were excised, cannulated on a Langendorff apparatus, and perfused retrogradely with Krebs-Henseleit buffer (95% O2, 5% CO2; pH 7.4) under constant pressure (100 cmH2O) and temperature (37°C) as previously described [13, 14]. Buffer consisted of (in mmol/L): NaCl (120), KCl (4.7), KH2PO4 (1.2), NaHCO3 (25), MgSO4 (1.2), d-glucose (11), and CaCl2 (1.75). Hearts were subjected to either a five-minute perfusion period, after which they were sectioned into two equal halves and snap-frozen with liquid nitrogen for molecular experiments, an ischemia-reperfusion protocol, or digestion for cardiomyocyte isolation, or as detailed below.

Ischemia-reperfusion injury protocol:

Immediately after Langendorff cannulation, hearts were perfused with oxygenated Krebs-Henseleit buffer and allowed to equilibrate for a baseline period of 20 mins. This baseline period was followed by 20 mins of global, normothermic ischemia, in which buffer flow was halted. Subsequently, perfusion was re-established for either 45 or 90 mins of reperfusion. At the conclusion of reperfusion, hearts were perfused with 10 mL of 1% tetrazolium tetrachloride (TTC) solution over the course of 2 mins. Hearts were then incubated in TTC solution for an additional 20 mins at 37°C to stain for infarct and then fixed in 10% formalin solution. Hearts were subsequently sectioned cross-sectionally, imaged using a dissecting scope (Leica) and analyzed for infarct size using Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD) by a blinded investigator.

RNA Isolation, Extraction and cDNA Conversion:

Hearts were homogenized in TRIzol (1 mL, Ambion) using a Precellys Evolution 24 Homogenizer (2 × 30 sec cycles, 0°C, 7200 RPM; Bertin Instruments) with a hard tissue lysing kit. Lysates were mixed with chloroform (200 μL, Thermo Fisher), incubated (5 mins, 25°C), and centrifuged (12,000 × g, 15 mins, 4°C) for phase separation. RNA collected from the upper phase was precipitated by incubation (10 mins, 25°C) with isopropyl alcohol (500 μL) and centrifugation (12,000 × g, 10 mins, 4°C). RNA pellets were washed with ethanol (500 μL, 75% EtOH), centrifuged (12,000 × g, 10 mins, 4°C), and air dried under a laminar flow hood (30 mins). Following RNA solubilization (100 μL, DEPC-treated water), RNA concentration and purity (A260/A280 range 1.96 to 2.08) were measured using a NanoDrop 100 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher), and RNA integrity was confirmed via 18S and 28S rRNA band visualization after agarose (1%) gel electrophoresis (1X TBE (Tris base, boric acid and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)). RNA was then converted to cDNA using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher) per manufacturer’s instructions. The reverse transcription reaction mixture was prepared on ice, RNA (2 μg) was added, and the samples were run on a thermocycler (10 mins, 25°C; 120 mins, 37°C; 5 mins, 85°C; held, 4°C; Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA). The resulting cDNA was stored (−80°C) until use.

Quantitative PCR:

mRNA transcript levels were measured in a 96-well plate format (Thermo Fisher) using a PCR master mix (TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix, Applied Biosystems) on a thermocycler (2 mins, 50°C; 2 mins, 95°C; (1 sec, 95°C; 20 sec, 60°C) × 40), Applied Biosystems)) with the following validated primers (TaqMan, Applied Biosystems): Atp2a2 (Mm01201431_m1), Col1a2 (Mm00483888_m1), Col3a1 (Mm00802300_m1), Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1), Myh6 (Mm00440359_m1), and Myh7 (Mm00600555_m1). Expression was determined using the ΔΔCT method and normalized to Gapdh, which did not change in cycle time with CdCl2 treatment or sex.

Heart Homogenate Preparation and Protein Quantification:

Hearts were homogenized in cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) supplemented with a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Cell Signaling Technology) using a Precellys Evolution 24 Homogenizer (2 × 30 sec cycles, 0°C, 7200 RPM; Bertin Instruments) with a hard tissue lysing kit. The heart homogenate was then incubated briefly on ice for 5 mins, followed by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 10 mins. The supernatant was recovered as total crude heart homogenate. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay, and homogenate aliquots were stored at −80°C until use.

Western Blot:

Whole heart homogenate samples (30 μg) were separated on a 4–12% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). One or two molecular weight markers were included with every gel to delineate molecular weight regions of interest (High Range Color-coded Prestained Protein Marker, Cell Signaling Technology; Novex Prestained Protein Standard, Thermo Fisher). Membranes were initially incubated with No-Stain Protein Labeling Reagent (Thermo Fisher) following the manufacturer’s instructions to covalently label lysine residues. Following incubation, membranes were visualized via fluorescence imaging (488 nm) in order to utilize total protein as a loading control. Membranes were then blocked for 1 hr with Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich). Membranes were subsequently incubated with primary antibodies against SERCA2a (1:500; sc-8094, goat, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), phosphorylated phospholamban (PLB) S16/T17 (1:1000; 8496S, rabbit, Cell Signaling), total PLB (1:1000, PA5–26004, rabbit, Thermo Fisher Scientific), α-actin (1:2500; 66125, mouse, ProteinTech, Rosemont, IL) or myosin-binding protein C (1:1000; ab133499, rabbit, Abcam). Membranes were then probed with the corresponding secondary antibody, either anti-rabbit (7074S, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-mouse (7076S, Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-goat (R1317HRP, OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD), for 1 hr and visualized by electrogenerated chemiluminescence (Life Technologies). In the case of phospho-blots, membranes were stripped with Re-blot Plus Mild Solution (EMD Millipore, Temecula, CA) and re-probed for total protein (i.e., total PLB). Densitometry was assessed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), and normalized to total protein.

Histology:

Formalin-fixed heart sections were paraffin-embedded, sliced, mounted, and stained with either hematoxylin and eosin or Masson’s trichrome to visualize cell morphology and collagen deposition, respectively. Whole slides were scanned at 10x and 20x magnification (Aperio ScanScope) in a blinded fashion and digital slides were subsequently analyzed using a standard positive pixel count algorithm (Positive Pixel Count v.9.1, Aperio, Leica Biosystems) set to read blue pixels as positive and red as negative, categorizing the former into thee bins of intensity. Positivity, representing the number of positive pixels over the total number of positive and negative pixels, quantified myocardial collagen as a percent of total myocardial area and is reported as percent fibrosis.

Cardiomyocyte Isolation, and Ca2+ transient and Sarcomere Shortening Measurement:

Ventricular cardiomyocytes were isolated from male and female mice exposed to cadmium for eight weeks or non-exposed controls, as previously described [15]. Immediately after Langendorff cannulation, hearts were perfused retrogradely (37°C, 1.5 mL/min) with a solution (pH 7.4) containing the following (in mmol/L): NaCl (120), KCl (5.4), NaH2PO4 (1.2), NaHCO3 (20), MgCl2 (1), 2,3-butanedione monoxime (5), taurine (5), and glucose (5.5). Perfusion was then switched to the same solution supplemented with type II collagenase (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ) and type 14 protease (Sigma-Aldrich) for 8–15 mins. Following digestion, hearts were minced and triturated gently. The cell suspension was then filtered (100 μm) and centrifuged at 800 RPM. Isolated cardiomyocytes were rinsed and stored in Tyrode buffer (pH 7.4) containing the following (in mmol/L): NaCl (140), KCl (5), MgCl2 (1), HEPES (10), and glucose (5.5), and were gradually stepped up to a final [Ca2+] of 1 mmol/L. Ca2+ transients and sarcomere shortening were then measured using an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE-2000U) and a custom-built IonOptix system with IonWizard software as previously described [15]. Cells were initially loaded with 2 μmol/L Fura-2-AM (F1221, Thermo Fisher) for 15 mins at room temperature and then washed for at least 30 mins. Cardiomyocytes were stimulated at 1 Hz and maintained at 37°C in Tyrode buffer for all measurements. Fura-2-AM was excited at 340 and 380 nm alternating at 250 Hz and emission recorded at 510 nm by a single photon multiplier tube. Background was subtracted from Fura-2 readings and the results filtered with a Lowpass Butterworth Filter (cutoff frequency of 10 Hz, 2 poles). Multiple baseline Ca2+ transients (10–15) were signal averaged for analysis. The fluorescence ratio value is shown as F/F0 (fluorescence normalized to baseline 340/360). Cardiomyocytes were used for functional measurements within 6 hrs of isolation. For acute cadmium exposure, cardiomyocytes were isolated from male hearts and incubated in Tyrode buffer containing 0, 1, 10 or 100 μmol/L CdCl2 for 20 mins at room temperature and washed before Ca2+ transients and sarcomere shortening were assessed.

Statistical Analysis:

Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM and were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA). Statistical outliers were identified by the ROUT method (Q = 1%). Statistical comparisons between groups were determined using an ordinary one-way ANOVA, a two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, or a two-tailed Mann–Whitney test as appropriate; significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical tests and significant p values are reported in their respective figure legends.

RESULTS

Exposure to CdCl2 impairs left ventricular function and alters cardiac structure in male but not female mice

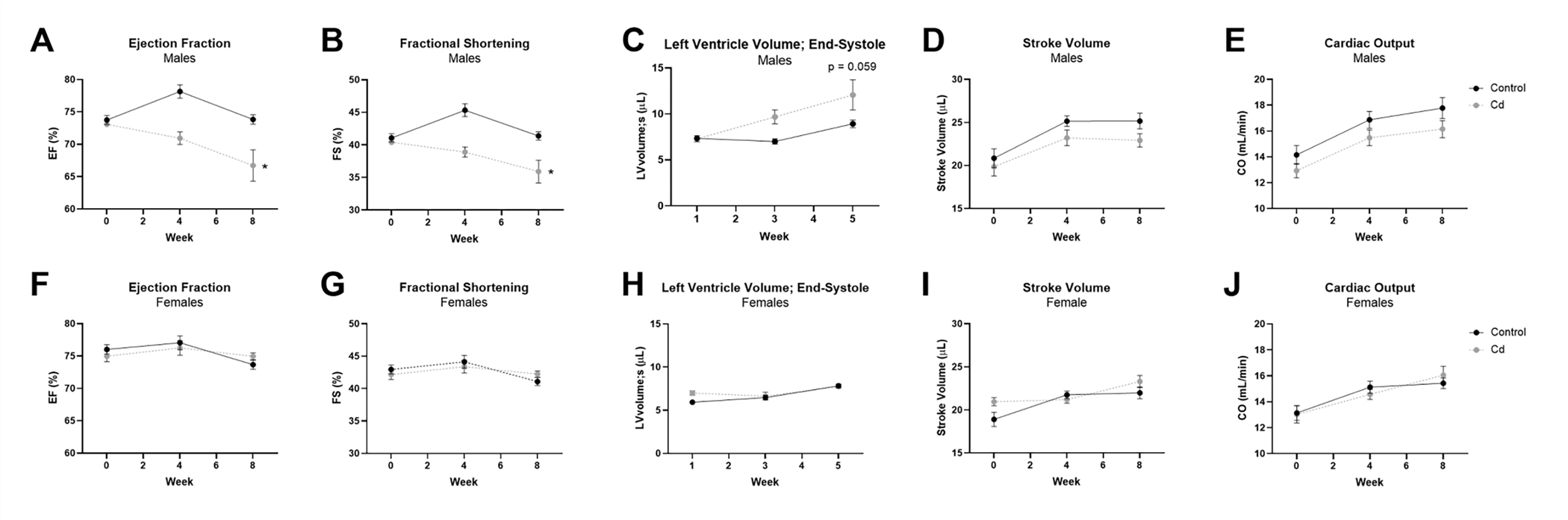

Male and female mice were exposed to 5 mg/L CdCl2 (3.3 mg/L total cadmium measured via ICP-MS) via drinking water and transthoracic echocardiography was conducted to assess potential changes in left ventricular structure and function at zero-, four- and eight-weeks of exposure (Table 1). We noted significant decreases in ejection fraction (Fig. 1a) and fractional shortening (Fig. 1b) with CdCl2 exposure in male mice. Consistent with the decrease in left ventricular function, we also observed an increase in left ventricular volume at end-systole that was trending towards statistical significance (Fig. 1c). Stroke volume (Fig. 1d) and cardiac output (Fig. 1e) were also decreased in male mice with CdCl2 exposure, but these changes were not significant. Interestingly, this functional impairment was completely absent in female mice (Fig. 1f – 1j).

Table 1.

Echocardiographic parameters for male and female hearts at zero-, four-, and eight-weeks of CdCl2 exposure.

| Male Control | Male Cd | Female Control | Female Cd | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 0 | Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 0 | Week 4 | Week 8 | p-value | Week 0 | Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 0 | Week 4 | Week 8 | p-value | |

| IVS;d | 0.915 | 0.854 | 0.971 | 0.925 | 0.894 | 0.888 | 0.063 | 0.919 | 0.905 | 0.873 | 0.890 | 0.909 | 0.877 | 0.779 |

| IVS;s | 1.392 | 1.477 | 1.526 | 1.468 | 1.397 | 1.391 | 0.012 | 1.448 | 1.395 | 1.424 | 1.386 | 1.406 | 1.366 | 0.442 |

| LVID;d | 2.741 | 2.897 | 2.964 | 2.699 | 2.917 | 2.988 | 0.761 | 2.606 | 2.748 | 2.808 | 2.736 | 2.732 | 2.855 | 0.030 |

| LVID;s | 1.613 | 1.583 | 1.738 | 1.607 | 1.786 | 1.925 | 0.052 | 1.486 | 1.535 | 1.654 | 1.583 | 1.548 | 1.649 | 0.053 |

| LVPW;d | 0.971 | 0.929 | 0.907 | 0.888 | 0.923 | 0.917 | 0.346 | 0.952 | 1.001 | 0.897 | 1.003 | 0.984 | 0.852 | 0.342 |

| LVPW;s | 1.310 | 1.330 | 1.286 | 1.311 | 1.328 | 1.272 | 0.985 | 1.229 | 1.348 | 1.223 | 1.285 | 1.385 | 1.232 | 0.791 |

| EF | 73.747 | 78.138 | 73.821 | 73.073 | 70.927 | 66.713 | 0.006 | 76.018 | 77.056 | 73.668 | 74.975 | 76.263 | 74.959 | 0.141 |

| FS | 41.066 | 45.319 | 41.367 | 40.411 | 38.900 | 35.901 | 0.004 | 42.941 | 44.128 | 41.071 | 42.162 | 43.372 | 42.240 | 0.162 |

| LV Mass | 67.122 | 65.965 | 73.846 | 61.027 | 69.075 | 70.816 | 0.435 | 61.721 | 67.600 | 62.436 | 66.453 | 66.254 | 62.069 | 0.588 |

| LV Volume;d | 28.190 | 32.155 | 34.091 | 27.156 | 32.891 | 34.981 | 0.740 | 24.834 | 28.216 | 29.810 | 27.949 | 27.837 | 31.063 | 0.041 |

| LV Volume;s | 7.347 | 7.006 | 8.930 | 7.289 | 9.679 | 12.069 | 0.059 | 5.931 | 6.463 | 7.825 | 6.990 | 6.643 | 7.762 | 0.079 |

| SV | 20.844 | 25.150 | 25.162 | 19.866 | 23.211 | 22.913 | 0.755 | 18.901 | 21.754 | 21.983 | 20.959 | 21.195 | 23.301 | 0.046 |

| CO | 14.153 | 16.869 | 17.780 | 12.926 | 15.480 | 16.155 | 0.950 | 13.135 | 15.128 | 15.427 | 13.019 | 14.568 | 16.057 | 0.436 |

| HR | 680.795 | 670.902 | 705.792 | 656.252 | 669.094 | 704.237 | 0.485 | 695.345 | 695.519 | 703.529 | 619.045 | 687.974 | 688.88 | 0.058 |

Interventricular septum thickness at end diastole (IVS;d) and end systole (IVS;d), left ventricular internal dimension at end diastole (LVID;d) and end systole (LVID;s), left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end diastole (LVPW;d) and end systole (LVPW;s), ejection fraction (EF), fractional shortening (FS), left ventricular mass (LV Mass), left ventricular volume at end diastole (LV Volume;d) and end systole (LV Volume;s), stroke volume (SV), cardiac output (CO), and heart rate (HR). Datasets were analyzed via two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (n = 10 mice/group).

Figure 1. Left ventricular function is impaired with CdCl2 exposure in male mice.

(A-J) Transthoracic echocardiographic measurements for ejection fraction (EF), fractional shortening (FS), left ventricular volume at end-systole (LVolume;s), stroke volume (SV), and cardiac output (CO) from CdCl2-exposed and non-exposed male (A-E) and female (F-J) mice (n = 10 mice/group). Datasets were analyzed via two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (*p < 0.05 vs. non-exposed control).

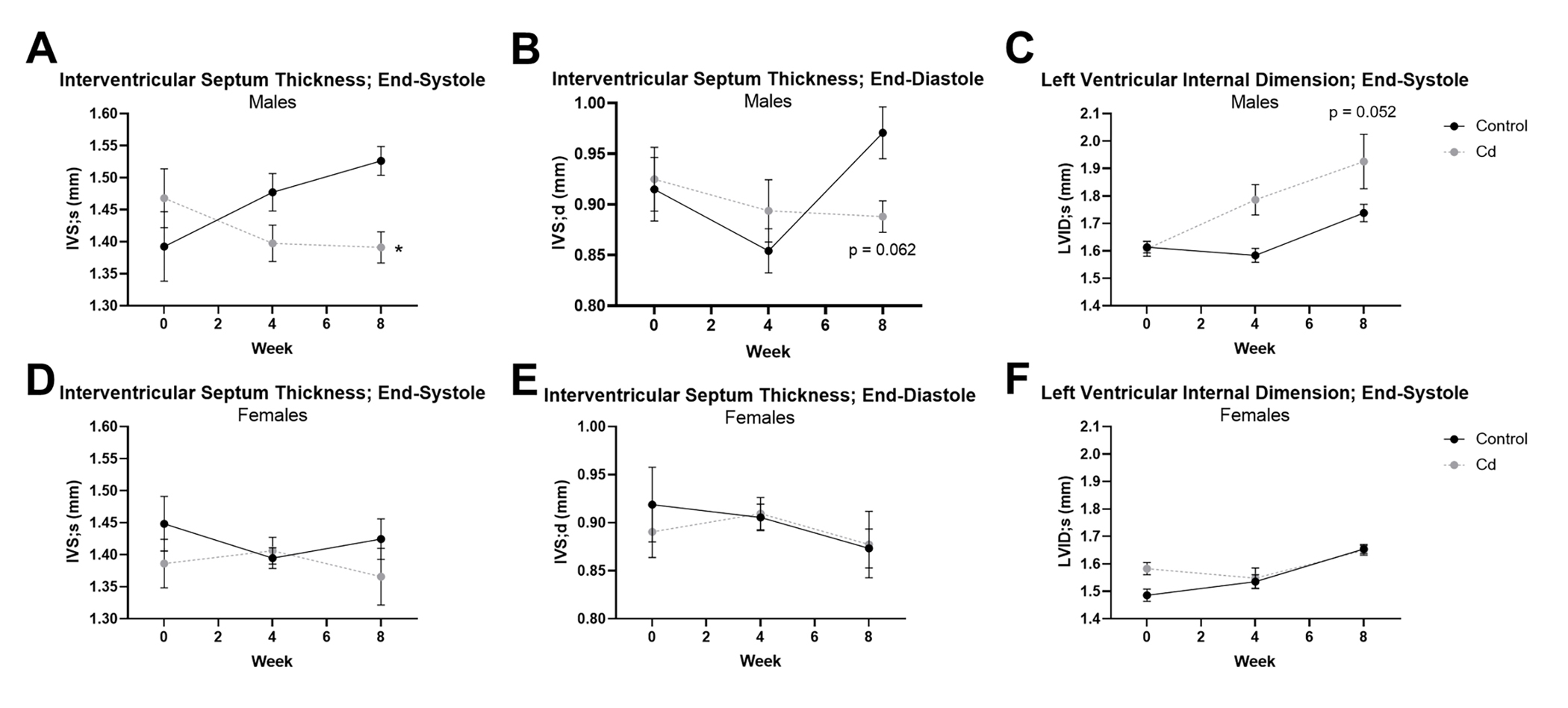

Changes in left ventricle structure were also examined with CdCl2 exposure. We found that interventricular septal thickness was significantly decreased at end-systole (Fig. 2a) and trending towards a significant decrease at end-diastole in male mice exposed to CdCl2 (Fig. 2b). Left ventricular internal dimension was also increased in male mice at end-systole (Fig. 2c), but this change was not significant, nor was it observed at end-diastole. CdCl2-dependent effects in these parameters were once again absent in female mice (Fig. 2d – 2f).

Figure 2. Cardiac structure is altered with CdCl2 exposure in male mice.

(A-F) Transthoracic echocardiographic measurements for interventricular septum thickness at end-systole (IVS;s) and end-diastole (IVS;d), and left ventricular internal dimension at end-systole (LVID;s) from CdCl2-exposed and non-exposed male (A-C) and female (D-F) mice (n = 10 mice/group). Datasets were analyzed via two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (*p < 0.05 vs. non-exposed control).

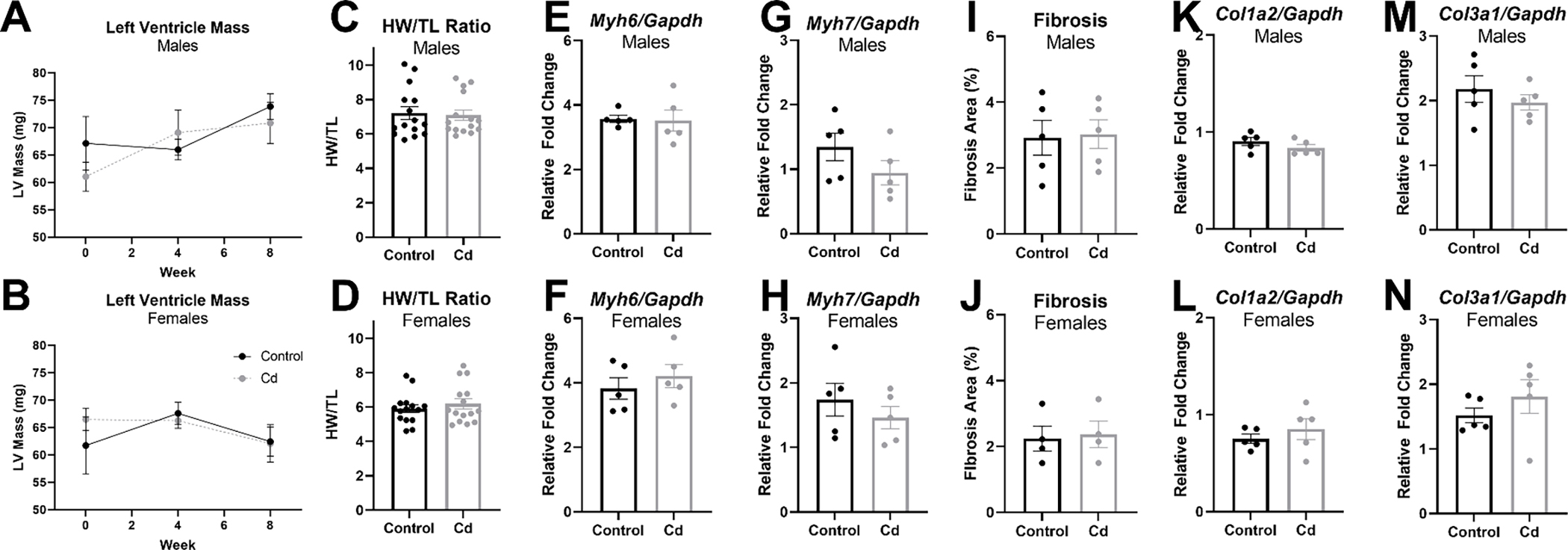

Exposure to CdCl2 does not induce myocardial hypertrophy or fibrosis

Since CdCl2 exposure reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and fractional shortening in male mice, we next examined heart size for evidence of pathologic hypertrophy. In vivo left ventricular mass was extrapolated using transthoracic echocardiography and gravimetric heart weight-to-tibia length measurements were collected, but we observed no difference in left ventricular mass (Fig. 3a – 3b) or heart size (Fig. 3c – 3d) with CdCl2 exposure in male or female mice. We also examined α-myosin heavy chain (Myh6) and β-myosin heavy chain 7 (Myh7) expression as markers of pathological hypertrophy using RT-qPCR, but no changes in the transcript levels of Myh6 (Fig. 3e – 3f) or Myh7 (Fig. 3g – 3h) were observed with CdCl2 exposure in either sex.

Figure 3. CdCl2 exposure does not induce cardiac hypertrophy or fibrosis.

(A-B) Transthoracic echocardiographic extrapolation of left ventricular mass from CdCl2-exposed and non-exposed male (A) and female (B) mice (n = 10 mice/group). (D-C) Heart size as assessed via heart weight-to-tibia length for CdCl2-exposed and non-exposed male (C) and female (D) mice (n = 15 hearts/group). (E-H) mRNA transcript levels in whole hearts from CdCl2-exposed and non-exposed male and female mice for α-myosin heavy chain (Myh6) (E,F) and β-myosin heavy chain (Myh7) (G, H) (n = 5 hearts/group). (I-J) Percent fibrosis/collagen from Masson’s trichrome stained heart sections from CdCl2-exposed and non-exposed male (I) and female (J) mice (n = 4–5 hearts/group). (K-L) mRNA transcript levels in whole hearts from CdCl2-exposed and non-exposed male and female mice for Col1a2 (K, L) and Col3a1 (M, N) (n = 5 hearts/group). Datasets were analyzed via two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (A, B) or Mann–Whitney test (C-N).

Masson’s Trichome stain was also used to assess changes in collagen deposition or fibrosis, but we found no evidence of increased collagen deposition in either sex with CdCl2 exposure (Fig. 3i – 3j). These results were confirmed by measuring transcript levels of two collagen gene markers reported to be associated with fibrosis [16], Col1a2 and Col3a1, but no changes were detected in either male or female hearts with CdCl2 exposure (Fig. 3k – 3n). Taken together, these findings suggest that the decline in cardiac function observed with CdCl2 exposure is unlikely to result from pathological cardiac hypertrophy or fibrosis.

Exposure to CdCl2 does not alter blood pressure

Previous studies have reported that cadmium exposure is associated with increased blood pressure [7, 17, 18]. As such, we next examined the effect of CdCl2 exposure on blood pressure and heart rate. However, we did not detect a change in blood pressure (Supplemental Fig. 2a – 2b) or heart rate (Supplemental Fig. 2c – 2d) in either male or female mice exposed to CdCl2.

Exposure to CdCl2 does not alter cardiac susceptibility to ischemic injury

A previous report also suggests that cadmium may alter cardiac susceptibility to ischemic injury [19], hence we next examined the effect of CdCl2 exposure on myocardial damage caused by ischemia-reperfusion injury using an ex vivo preparation. Infarct size did not change with eight weeks of CdCl2 exposure following 20 mins of global ischemia in either sex, however (Supplemental Fig.3).

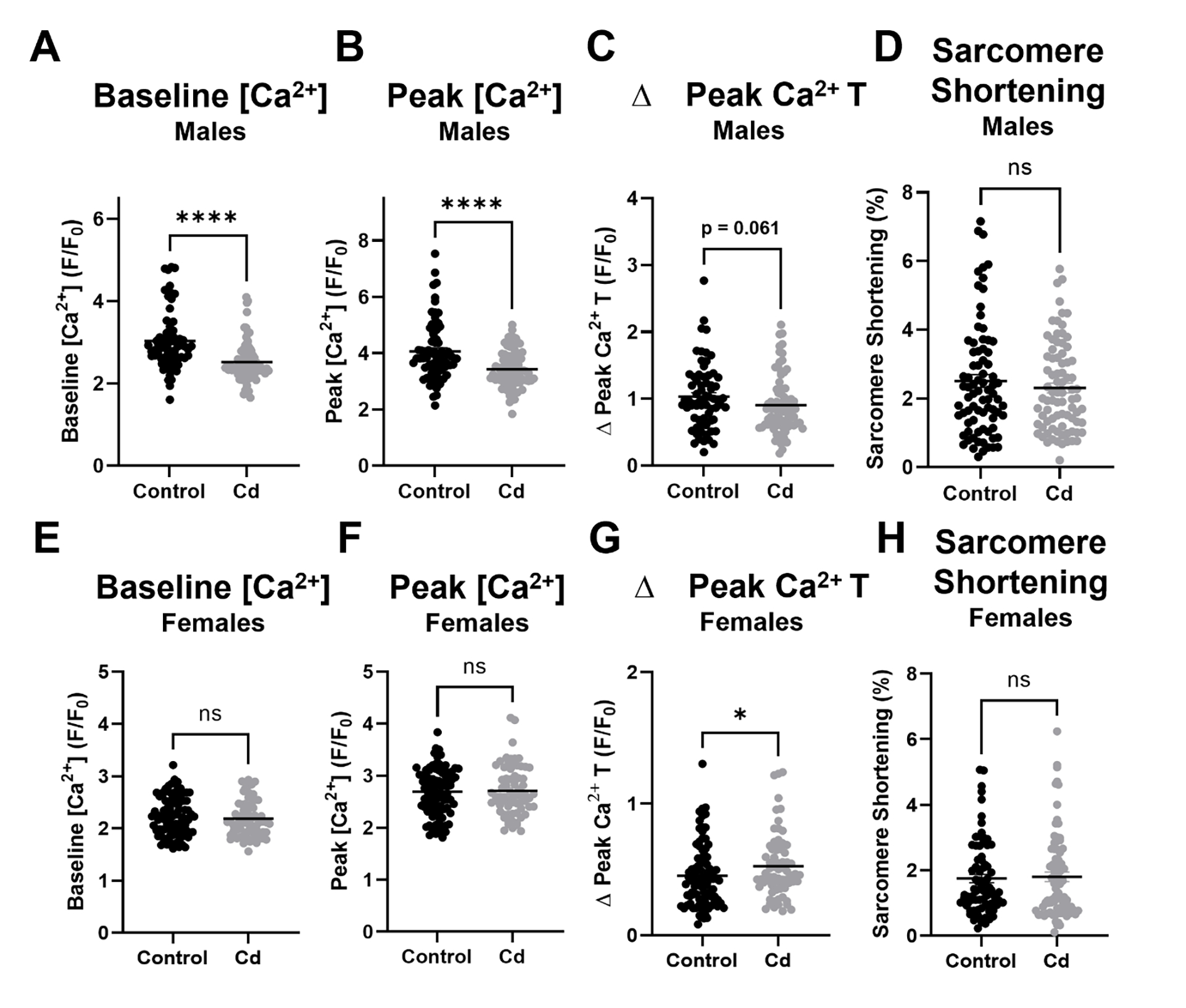

Exposure to CdCl2 alters Ca2+ transients and cell shortening in isolated male cardiomyocytes

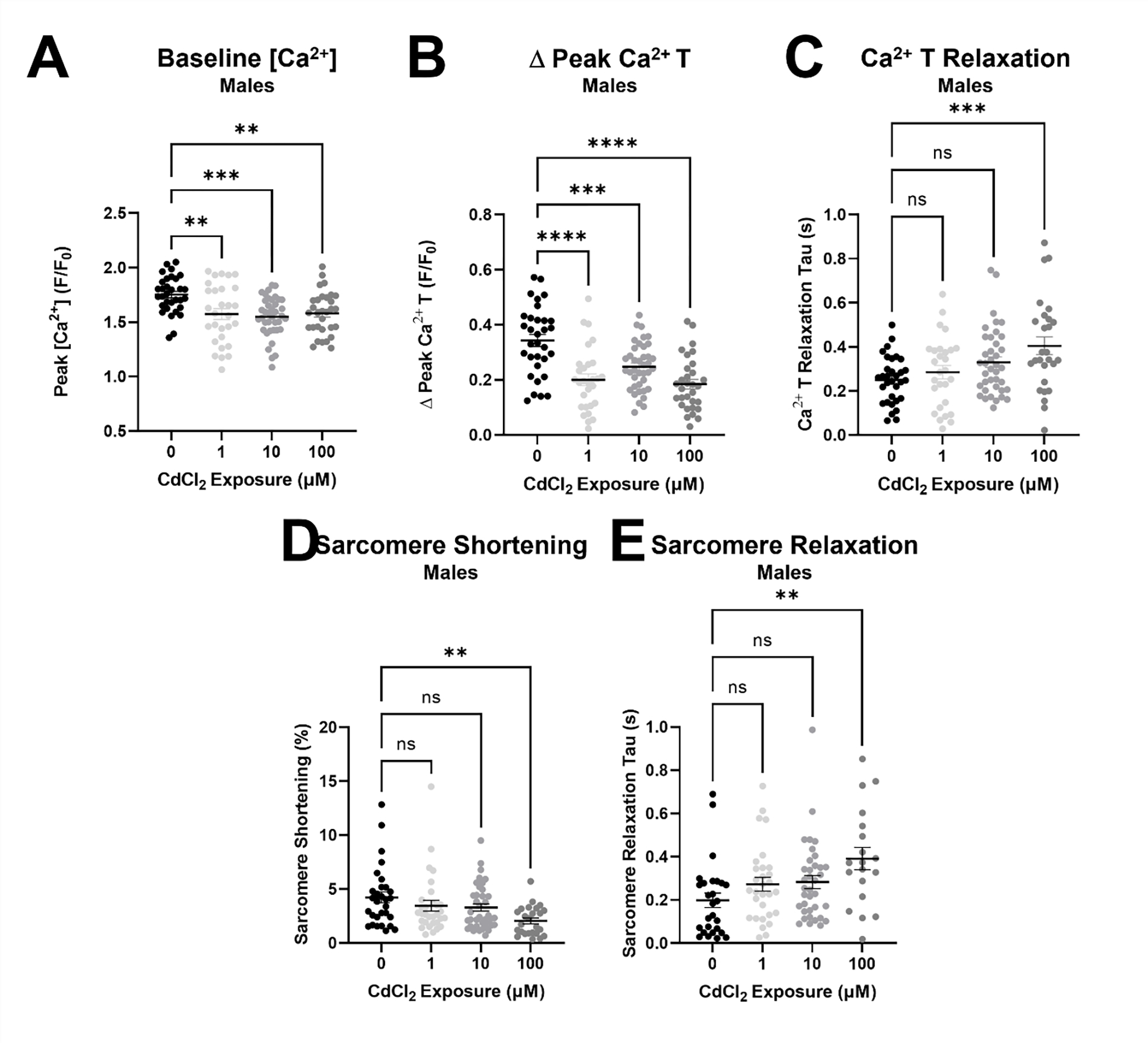

Since CdCl2 reduced ejection fraction and fractional shortening in male mice, we next examined the impact of an eight-week CdCl2 exposure on Ca2+ transients and sarcomere shortening in isolated cardiomyocytes from male and female mice. Cardiomyocytes from cadmium exposed males showed a significant decrease in baseline [Ca2+] (Fig. 4a) and peak [Ca2+] (Fig. 4b) levels vs. non-exposed male cardiomyocytes, along with a trending decrease in Ca2+ transient amplitude (Fig. 4c). Ca2+ transient decay was unaffected in cardiomyocytes from cadmium exposed males, as was sarcomere shortening (Fig. 4d). Conversely, we did not detect any significant changes in the same parameters with cardiomyocytes isolated from cadmium exposed females (Fig. 4e–h), aside from a slight but significant increase in Ca2+ transient amplitude, as compared to non-exposed female cardiomyocytes. As we noted altered Ca2+-handling with an eight week CdCl2 exposure in male cardiomyocytes, we also examined the dose-dependent impact of acute CdCl2 exposure on Ca2+ transients and sarcomere shortening in cardiomyocytes isolated from non-exposed control male mice. Consistent with the effects noted with the eight-week CdCl2 exposure model, acute exposure to CdCl2 induced a dose-dependent decrease in peak [Ca2+] levels and Ca2+ transient amplitude (Fig. 5a). Acute CdCl2 exposure also impaired Ca2+ transient relaxation (Fig. 5b),sarcomere shortening (Fig. 5c) and sarcomere relaxation (Fig. 5d). These findings are consistent with the impairment of in vivo cardiac function that was noted with CdCl2 exposure.

Figure 4. Chronic CdCl2 exposure alters cardiomyocyte Ca2+-handling.

(A) Baseline [Ca2+] levels, (B) peak [Ca2+] levels, (C) Ca2+ transient amplitude in male cardiomyocytes exposed to CdCl2 for eight weeks (n = 68–80 cardiomyocytes from 5 hearts/group). (A) Baseline [Ca2+] levels, (B) peak [Ca2+] levels, (C) Ca2+ transient amplitude in female cardiomyocytes exposed to CdCl2 for eight weeks (n = 69–92 cardiomyocytes from 5 hearts/group). Datasets were analyzed via Mann–Whitney test (****p < 0.05 vs. non-exposed control male, *p < 0.05 vs. non-exposed control female).

Figure 5. Acute CdCl2 exposure blunts cardiomyocyte Ca2+ transients and cell shortening.

(A) Peak [Ca2+] levels, (B) Ca2+ transient amplitude (Δ Peak Ca2+ T) and (C) Ca2+ transient relaxation (Ca2+ T relaxation tau) in male cardiomyocytes exposed to 0, 1, 10, and 100 μmol/L CdCl2 (n = 29–39 cardiomyocytes from 4 hearts/group). (D) Sarcomere shortening and (E) sarcomere relaxation (tau) in male cardiomyocytes exposed to 0, 1, 10, and 100 μmol/L CdCl2 (n = 29–39 cardiomyocytes from 4 hearts/group). Datasets were analyzed via one-way ANOVA (**, ***, ****p < 0.05 vs. non-exposed control).

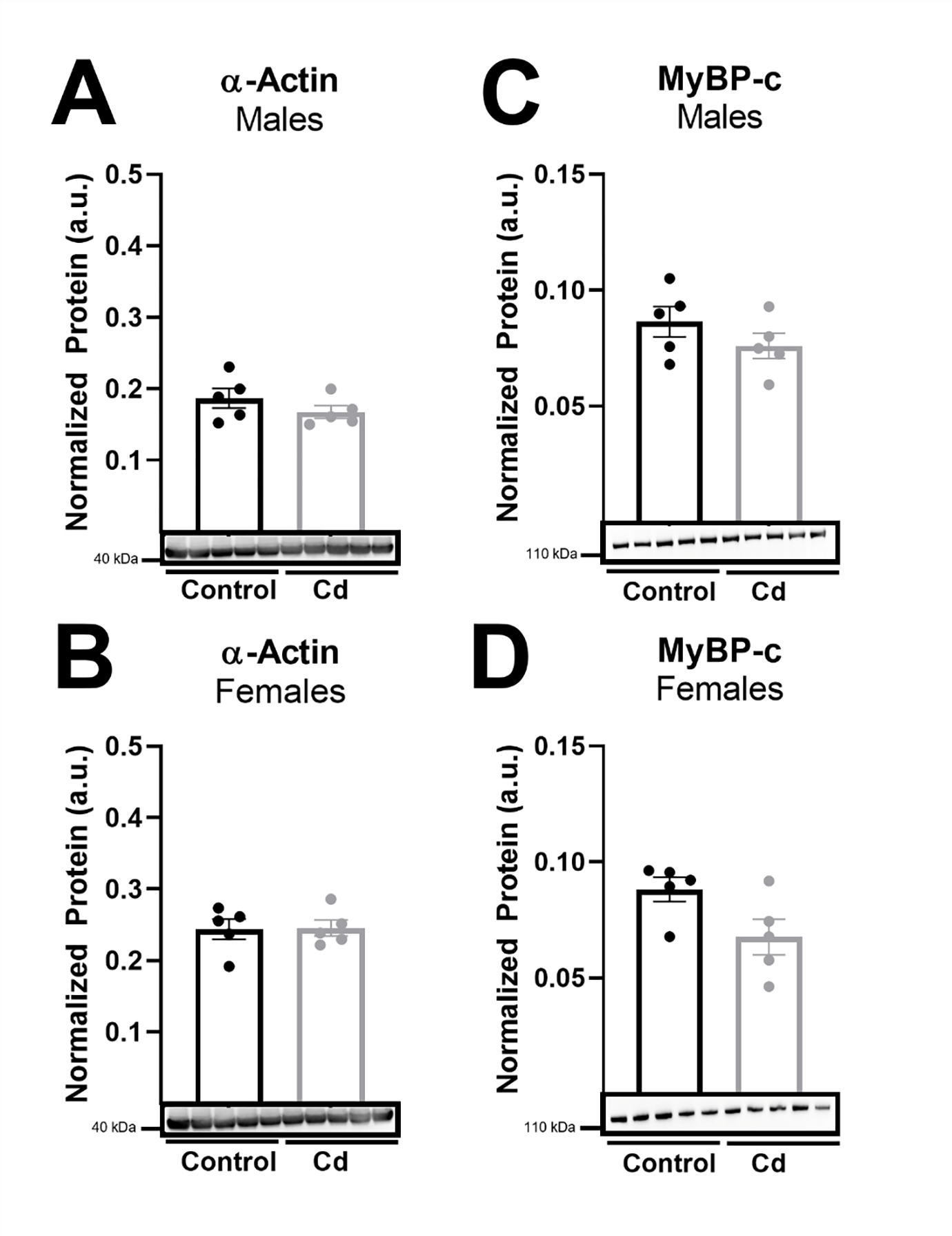

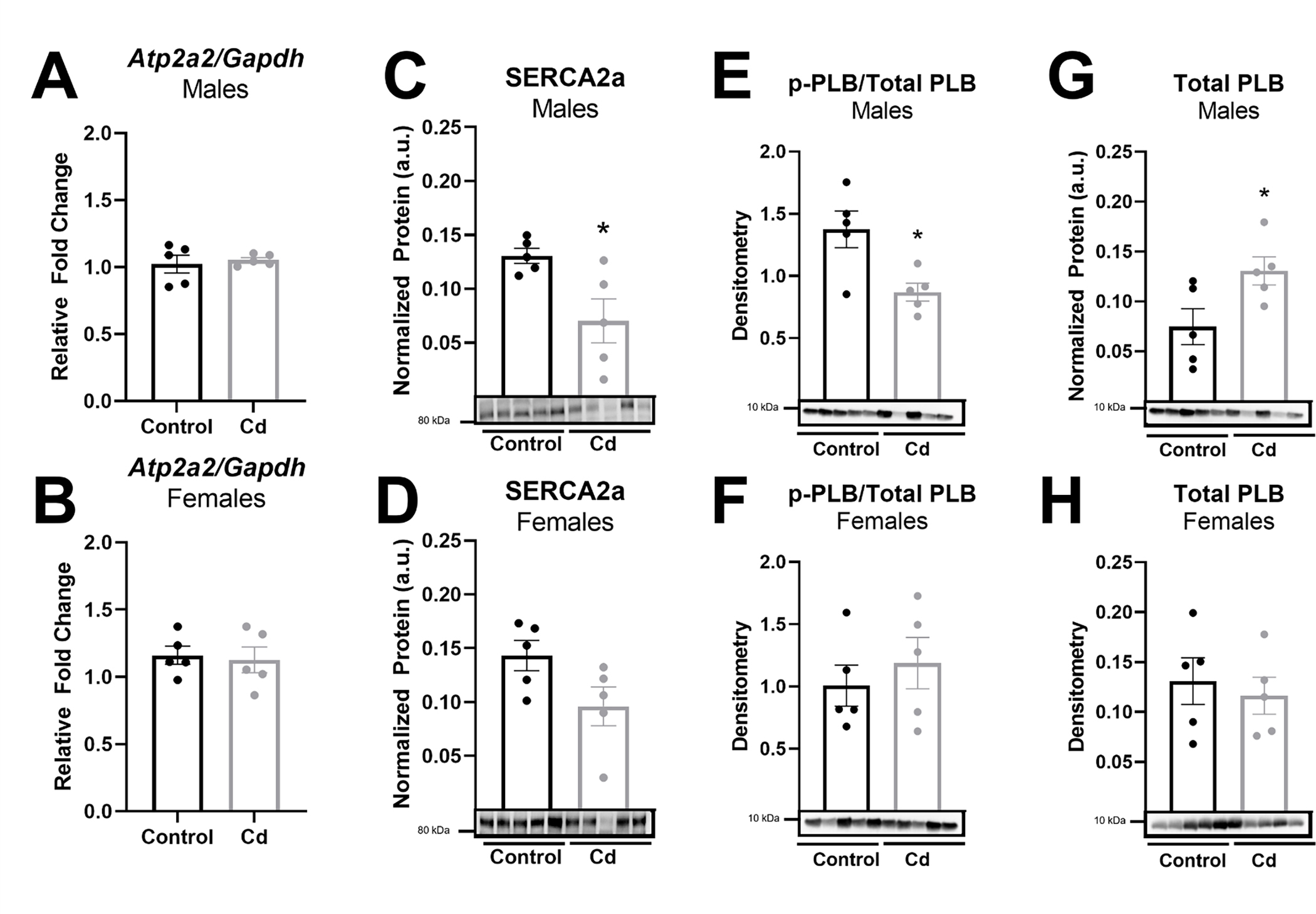

Exposure to CdCl2 alters the expression of Ca2+-handling proteins in male but not female hearts

To determine molecular mechanisms for our observed reduction in left ventricular and cardiomyocyte function in male mice with CdCl2 exposure, we next examined changes in the expression of select cardiac contractile proteins (see supplementary files for complete western blot images). Since we already determined that myosin transcript levels were not altered with CdCl2 exposure, we examined the protein expression levels of α-actin and myosin binding protein C. However, neither α-actin (Fig. 6a – 6b) nor myosin binding protein C (Fig. 6c – 6d) expression changed in the heart with CdCl2 exposure in male or female mice. We next examined the expression of two key Ca2+-handling proteins, SERCA2a, as well as phosphorylated and total PLB (see supplementary files for complete western blot images). We found that while SERCA2a transcript levels (Atp2a2, Fig. 7a – 7b) remained unchanged with CdCl2 exposure in either sex, SERCA2a protein expression was significantly decreased in hearts from CdCl2-exposed male mice (Fig. 7c) but not in hearts from exposed female mice (Fig. 7d). Phosphorylated PLB levels were also decreased in male mice with CdCl2 exposure (Fig. 7e – 7f), which was driven in part, from an increase in total PLB expression (Fig. 7g – 7h). These findings are consistent with our observed decrease in left ventricular and cardiomyocyte function with CdCl2 exposure in male mice.

Figure 6. CdCl2 exposure does not alter expression of cardiac contractile proteins.

(A-D) Protein expression in whole hearts from CdCl2-exposed and non-exposed male and female mice for α-actin (A-B) and myosin-binding protein C (MyBP-c) (C-D) (n = 5 hearts/group). Datasets were analyzed via Mann–Whitney test.

Figure 7. SERCA2a protein expression and phosphorylated-PLB are decreased with CdCl2 exposure in male hearts.

(A-B) Atp2a2 (SERCA2a) mRNA transcript levels in whole hearts from CdCl2-exposed and non-exposed male (A) and female (B) mice (n = 5 hearts/group). (C-H) Protein expression in whole hearts from CdCl2-exposed and non-exposed male and female mice for SERCA2a (C-D), phosphorylated PLB/total PLB (E-F), and total PLB (G-H) (n = 5 hearts/group). Datasets were analyzed via Mann–Whitney test (*p < 0.05 vs. non-exposed control).

DISCUSSION

Herein, we demonstrate for the first time that an eight-week, environmentally-relevant cadmium exposure impairs left ventricular function in male mouse hearts, but not female hearts. Furthermore, we found that the in vivo contractile dysfunction observed with cadmium exposure in male hearts persisted at the level of the isolated cardiomyocyte, with cadmium exposure blunting Ca2+ transient amplitude and reducing sarcomere shortening. SERCA2a protein expression and phosphorylated PLB levels were also decreased with cadmium exposure in male hearts. Interestingly, we found no evidence for pathology in female hearts. Epidemiological studies have noted an association between cadmium exposure and the development of CVD [20], and we provide a potential mechanism for the cardiotoxic effects of cadmium. We also provide evidence to suggest that the male heart may be more susceptible to the detrimental impacts of cadmium.

Cadmium exposure and cardiac structure and function in male and female hearts

In the current study, we found that ejection fraction and fractional shortening were significantly decreased in male hearts after eight weeks of cadmium exposure (Fig. 1). Importantly, there is also a clear downward trend in left ventricular function over time, suggesting that ejection fraction and fractional shortening may continue to decrease with longer exposure periods. This is corroborated in epidemiological findings and has significant public health ramifications given the long half-life of cadmium in humans and the compounding impact of co-morbidities, including co-exposure to other heavy metals [10]. Consistent with the decline in ejection fraction, left ventricle volume at end-systole was also increased and stroke volume was decreased with cadmium exposure, although these changes were not significant. These findings are consistent with a prior epidemiological study that found left ventricular dysfunction with cadmium exposure in humans [10]. Furthermore, we found that interventricular septal thickness was decreased at end-systole and end-diastole with eight weeks of cadmium exposure in male hearts (Fig. 2). Left ventricular internal dimension was also increased during end-systole at eight weeks of exposure (Fig. 2), but this was not observed at end-diastole.

Taken together, our findings suggest that left ventricular contractility is reduced with cadmium exposure in male mice. However, further experimentation with a longer duration of cadmium exposure would be required to further confirm this phenotype. Interestingly, the aforementioned effects were completely absent in female hearts with cadmium exposure, suggesting that females have a robust mechanism that protects the heart against environmental stressors. Indeed, we have previously found that compared to males, female hearts are largely protected from ischemic injury [21–23] and exposure to other environmental toxicants, including arsenic [14]. Future studies will seek to elucidate this female-specific cardioprotective mechanism(s).

Cadmium exposure and cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis and blood pressure

To determine a potential mechanism for the cardiac functional impairment observed with cadmium exposure in males, we examined cadmium-exposed hearts for indications of hypertrophy and fibrosis. We did not find any evidence for cardiac hypertrophy, however, as heart size remained unchanged with exposure to cadmium in males and females (Fig. 3). Considering the possibility that cadmium may induce the fetal gene program underlying cardiac hypertrophy, we probed mRNA expression levels of cardiac myosin heavy chain in the corresponding α- and β- isoforms, which are differentially expressed under the pathological and physiological conditions, respectively, but we found no change in the ratio of cardiac α- to β-myosin heavy chain in male or female mice exposed to cadmium (Fig. 3) [24]. We also found no evidence for altered collagen deposition or cardiac fibrosis in male or female mice with cadmium exposure (Fig. 3). As such, our findings indicate that the cadmium-induced decline in cardiac function in males is unlikely to result from cardiac hypertrophy or fibrosis.

We further examined blood pressure but found no difference in systolic blood pressure over time with cadmium exposure in either sex (Supplemental Fig. 2). While previous epidemiological reports suggest an association between cadmium exposure and the development of hypertension in humans [7], our findings are consistent with a previous study that reported no significant change in systolic blood pressure over a six-week exposure period to cadmium in the same strain of mice [25]. Differences in cadmium metabolism between mice and humans may account for this lack of effect on blood pressure, and as such, the development of hypertension may potentially occur with more chronic exposure to cadmium over periods of several months to years [6].

Cadmium exposure and cardiomyocyte Ca2+-handling

In agreement with our observed decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction and fractional shortening, we found that an eight-week cadmium exposure decreased baseline [Ca2+] and peak [Ca2+] levels, and reduced Ca2+ transient amplitude in isolated male but not female cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4). We also found that acute cadmium exposure induced a dose-dependent decrease in peak [Ca2+] levels, Ca2+ transient amplitude and relaxation in cardiomyocytes isolated from male mice (Fig. 5). Sarcomere shortening and relaxation were similarly impaired at the highest dose of cadmium. These findings suggest that cadmium has both acute and chronic effects on cardiomyocyte function, since some differences were noted between the acute and chronic (eight week) exposures. Furthermore, several studies support these findings, showing that cadmium decreases baseline [Ca2+], reduces the maximal rate of Ca2+ accumulation, and inhibits SERCA2a activity to cause a generalized alteration in calcium homeostasis [26–28]. Considering that Ca2+ channels have been implicated in the transport of cadmium, it is also possible that cadmium disrupts the Ca2+ transient by acting in direct competition with Ca2+ ions and possibly exhibiting a higher affinity for Ca2+ binding sites, both which have been demonstrated across several cell types, including cardiomyocytes [29–34].

Furthermore, since Ca2+-handling and myofilament proteins are major drivers of cardiomyocyte contraction, we examined the expression of select myofilament proteins. We found that cadmium exposure did not alter transcript levels of α- or β-myosin, or the protein expression of α-actin or myosin binding protein C (Fig. 6). As such, we next examined protein expression of SERCA2a, which transports Ca2+ from the cytosol to the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) to facilitate cardiomyocyte relaxation, as well as the phosphorylation and expression of PLB, which inhibits SERCA2a-mediated Ca2+ uptake in its dephosphorylated state [35]. Consistent with our finding of reduced ejection fraction and fractional shortening, we found that SERCA2a protein expression was decreased in hearts from cadmium-exposed male mice (Fig. 7). SERCA2a is a major Ca2+-handling protein in the cardiomyocyte, primarily functioning to drive relaxation by facilitating SR Ca2+ re-uptake. However, SERCA2a can also affect cardiomyocyte contraction by regulating SR Ca2+ load, which is a major determinant of cardiomyocyte contractility. Therefore, decreased SERCA2a expression would be expected to contribute to a decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction and fractional shortening. Decreased SERCA2a expression has also been associated with reduced left ventricular function, impaired contractility, and heart failure [36]. We also found that phosphorylated PLB levels were decreased in hearts from cadmium-exposed male mice (Fig. 7). This reduction likely contributes to our observed decrease in ejection fraction and fractional shortening since PLB inhibits SERCA2a-mediated Ca2+ uptake in its dephosphorylated state. Taken together, these findings suggest that the cadmium-dependent in vivo impairment of left ventricular function (i.e., reduced ejection fraction and fractional shortening) occurs, in part, through the downregulation of SERCA2a protein levels and decreased phosphorylated PLB, thereby impairing Ca2+-handling and shortening in the cardiomyocyte.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that an eight-week cadmium exposure alters cardiac structure and reduces left ventricular ejection fraction and fractional shortening in male but not female hearts. This cadmium-induced decrease in cardiac function was also observed in isolated cardiomyocytes and occurred, in part, from altered cardiomyocyte Ca2+-handling, and decreased SERCA2a protein expression and PLB phosphorylation. These findings are significant because reduced left ventricular function can contribute to pathological remodeling of the heart and could eventually culminate in heart failure. As such, this study provides further mechanistic evidence to strengthen an association between cadmium and cardiovascular disease and highlights the importance of reducing human exposure to cadmium.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the technical assistance of the Small Animal Cardiovascular Phenotyping and Model Core and the Oncology Tissue Services Core at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. We also acknowledge the technical assistance of the TracE Analytical Metals (TEAM) Core at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [T32 ES007141 (NT, HG), K99 HL155840 (BLL), R21 HL157800 (MK) and R01 HL136496 (MK)] and the American Heart Association [CDA938718 (SM), 20POST35180102 (BLL), 20CDA35260135 (GKM)].

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2023 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2023;147. 10.1161/cir.0000000000001123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Measuring the global burden of disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369:448–57. 10.1056/NEJMra1201534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. 2019 acc/aha guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e596–e646. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cosselman KE, Navas-Acien A, Kaufman JD. Environmental factors in cardiovascular disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2015;12:627–42. 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tellez-Plaza M, Guallar E, Howard BV, Umans JG, Francesconi KA, Goessler W, et al. Cadmium exposure and incident cardiovascular disease. Epidemiology. 2013;24:421–9. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828b0631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Faroon O, Ashizawa A, Wright S, Tucker P, Jenkins K, Ingerman L, et al. Toxicological profile for cadmium. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US), Atlanta (GA); 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Swaddiwudhipong W, Mahasakpan P, Limpatanachote P, Krintratun S. Correlations of urinary cadmium with hypertension and diabetes in persons living in cadmium-contaminated villages in northwestern thailand: A population study. Environmental Research. 2010;110:612–6. 10.1016/j.envres.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Liu J, Li Y, Li D, Wang Y, Wei S. The burden of coronary heart disease and stroke attributable to dietary cadmium exposure in chinese adults, 2017. Science of The Total Environment. 2022;825:153997. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Everett CJ, Frithsen IL. Association of urinary cadmium and myocardial infarction. Environmental Research. 2008;106:284–6. 10.1016/j.envres.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yang WY, Zhang ZY, Thijs L, Cauwenberghs N, Wei FF, Jacobs L, et al. Left ventricular structure and function in relation to environmental exposure to lead and cadmium. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017;6:e004692. 10.1161/JAHA.116.004692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Peters JL, Perlstein TS, Perry MJ, McNeely E, Weuve J. Cadmium exposure in association with history of stroke and heart failure. Environmental Research. 2010;110:199–206. 10.1016/j.envres.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ollson CJ, Smith E, Herde P, Juhasz AL. Influence of sample matrix on the bioavailability of arsenic, cadmium and lead during co-contaminant exposure. Science of The Total Environment. 2017;595:660–5. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Veenema R, Casin KM, Sinha P, Kabir R, Mackowski N, Taube N, et al. Inorganic arsenic exposure induces sex-disparate effects and exacerbates ischemia-reperfusion injury in the female heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2019;316:H1053–h64. 10.1152/ajpheart.00364.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kabir R, Sinha P, Mishra S, Ebenebe OV, Taube N, Oeing CU, et al. Inorganic arsenic induces sex-dependent pathological hypertrophy in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;320:H1321–h36. 10.1152/ajpheart.00435.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Muller GK, Song J, Jani V, Wu Y, Liu T, Jeffreys WPD, et al. Pde1 inhibition modulates cav1.2 channel to stimulate cardiomyocyte contraction. Circulation Research. 2021;129:872–86. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Verrecchia F, Mauviel A. Transforming growth factor-beta and fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3056–62. 10.3748/wjg.v13.i22.3056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sompamit K, Kukongviriyapan U, Donpunha W, Nakmareong S, Kukongviriyapan V. Reversal of cadmium-induced vascular dysfunction and oxidative stress by meso-2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid in mice. Toxicology letters. 2010;198:77–82. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Donpunha W, Kukongviriyapan U, Sompamit K, Pakdeechote P, Kukongviriyapan V, Pannangpetch P. Protective effect of ascorbic acid on cadmium-induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction in mice. Biometals. 2011;24:105–15. 10.1007/s10534-010-9379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Devaux S, Maupoil V, Berthelot A. Effects of cadmium on cardiac metallothionein induction and ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;87:617–23. 10.1139/y09-046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tellez-Plaza M, Jones MR, Dominguez-Lucas A, Guallar E, Navas-Acien A. Cadmium exposure and clinical cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 2013;15:356. 10.1007/s11883-013-0356-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Casin KM, Fallica J, Mackowski N, Veenema RJ, Chan A, St Paul A, et al. S-nitrosoglutathione reductase is essential for protecting the female heart from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Circ Res. 2018;123:1232–43. 10.1161/circresaha.118.313956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Shao Q, Casin KM, Mackowski N, Murphy E, Steenbergen C, Kohr MJ. Adenosine a1 receptor activation increases myocardial protein s-nitrosothiols and elicits protection from ischemia-reperfusion injury in male and female hearts. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177315. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shao Q, Fallica J, Casin KM, Murphy E, Steenbergen C, Kohr MJ. Characterization of the sex-dependent myocardial s-nitrosothiol proteome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015:ajpheart.00681.2015. 10.1152/ajpheart.00681.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Taegtmeyer H, Sen S, Vela D. Return to the fetal gene program. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1188:191–8. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Türkcan A, Scharinger B, Grabmann G, Keppler BK, Laufer G, Bernhard D, et al. Combination of cadmium and high cholesterol levels as a risk factor for heart fibrosis. Toxicological Sciences. 2015;145:360–71. 10.1093/toxsci/kfv057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Biagioli M, Pifferi S, Ragghianti M, Bucci S, Rizzuto R, Pinton P. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and alteration in calcium homeostasis are involved in cadmium-induced apoptosis. Cell Calcium. 2008;43:184–95. 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hechtenberg S, Beyersmann D. Inhibition of sarcoplasmic reticulum ca2+-atpase activity by cadmium, lead and mercury. Enzyme. 1991;45:109–15. 10.1159/000468875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hinkle PM, Shanshala ED, Nelson EJ. Measurement of intracellular cadmium with fluorescent dyes. Further evidence for the role of calcium channels in cadmium uptake. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:25553–9. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)74076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ortega P, Custódio MR, Zanotto FP. Characterization of cadmium transport in hepatopancreatic cells of a mangrove crab ucides cordatus: The role of calcium. Aquatic Toxicology. 2017;188:92–9. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hinkle PM, Kinsella PA, Osterhoudt KC. Cadmium uptake and toxicity via voltage-sensitive calcium channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262:16333–7. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)49259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Swandulla D, Armstrong CM. Calcium channel block by cadmium in chicken sensory neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1989;86:1736–40. 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Verbost PM, Senden MHMN, van Os CH. Nanomolar concentrations of cd2+ inhibit ca2+ transport systems in plasma membranes and intracellular ca2+ stores in intestinal epithelium. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1987;902:247–52. 10.1016/0005-2736(87)90302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Shen JB, Jiang B, Pappano AJ. Comparison of l-type calcium channel blockade by nifedipine and/or cadmium in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:562–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ahearn GA, Mandal PK, Mandal A. Mechanisms of heavy-metal sequestration and detoxification in crustaceans: A review. Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 2004;174:439–52. 10.1007/s00360-004-0438-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Gustavsson M, Verardi R, Mullen DG, Mote KR, Traaseth NJ, Gopinath T, et al. Allosteric regulation of serca by phosphorylation-mediated conformational shift of phospholamban. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:17338–43. 10.1073/pnas.1303006110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Shareef MA, Anwer LA, Poizat C. Cardiac serca2a/b: Therapeutic targets for heart failure. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2014;724:1–8. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.