Abstract

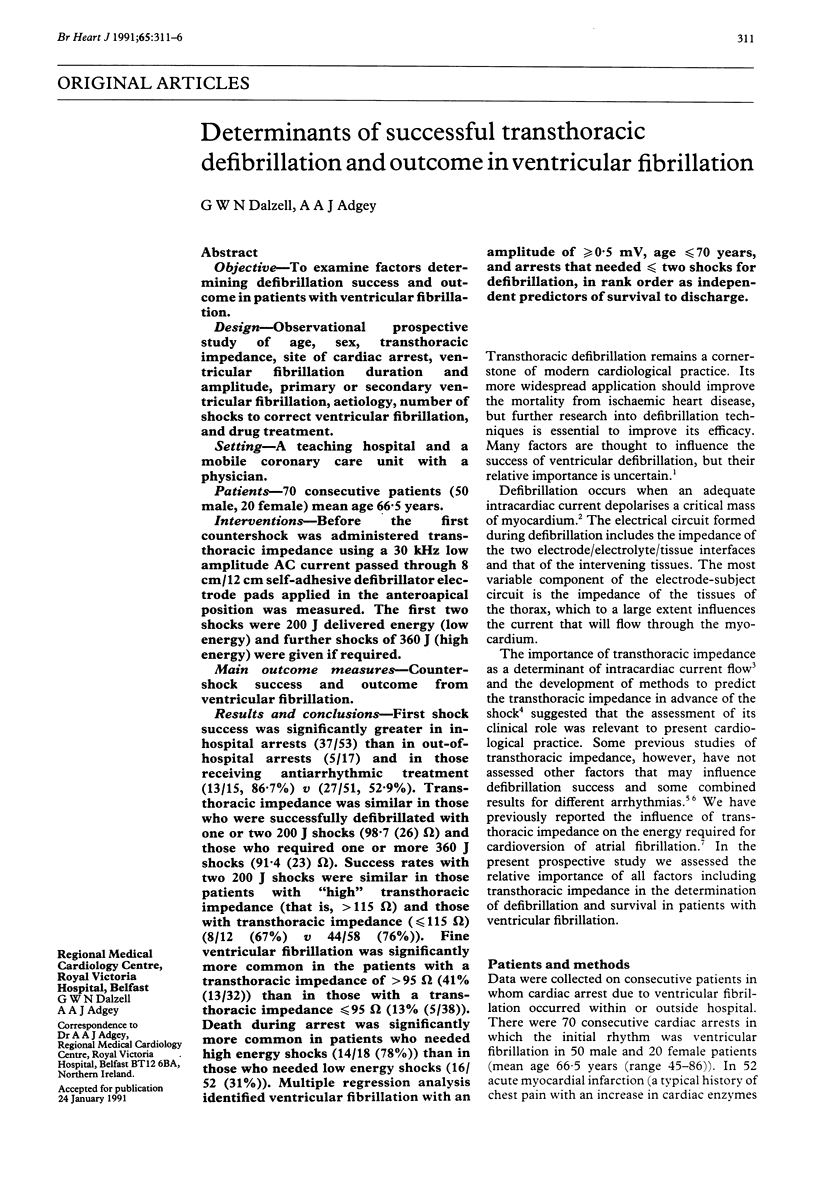

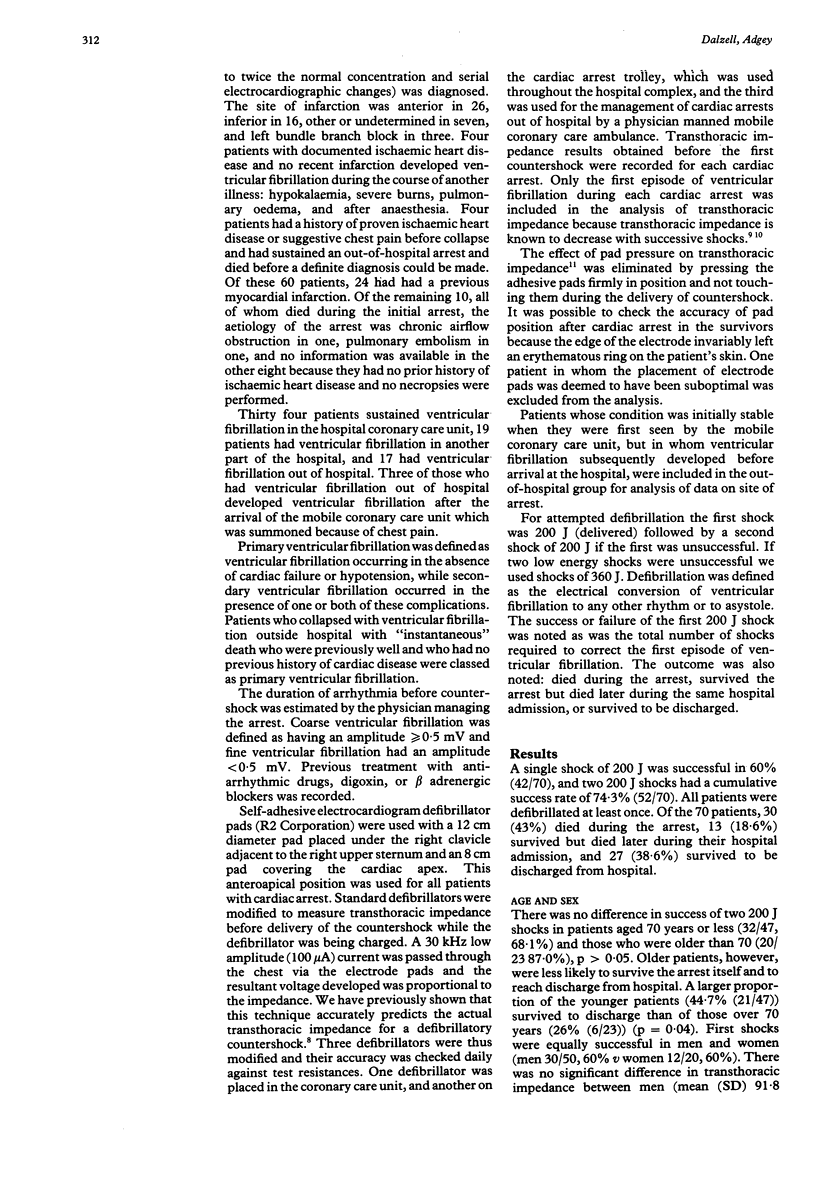

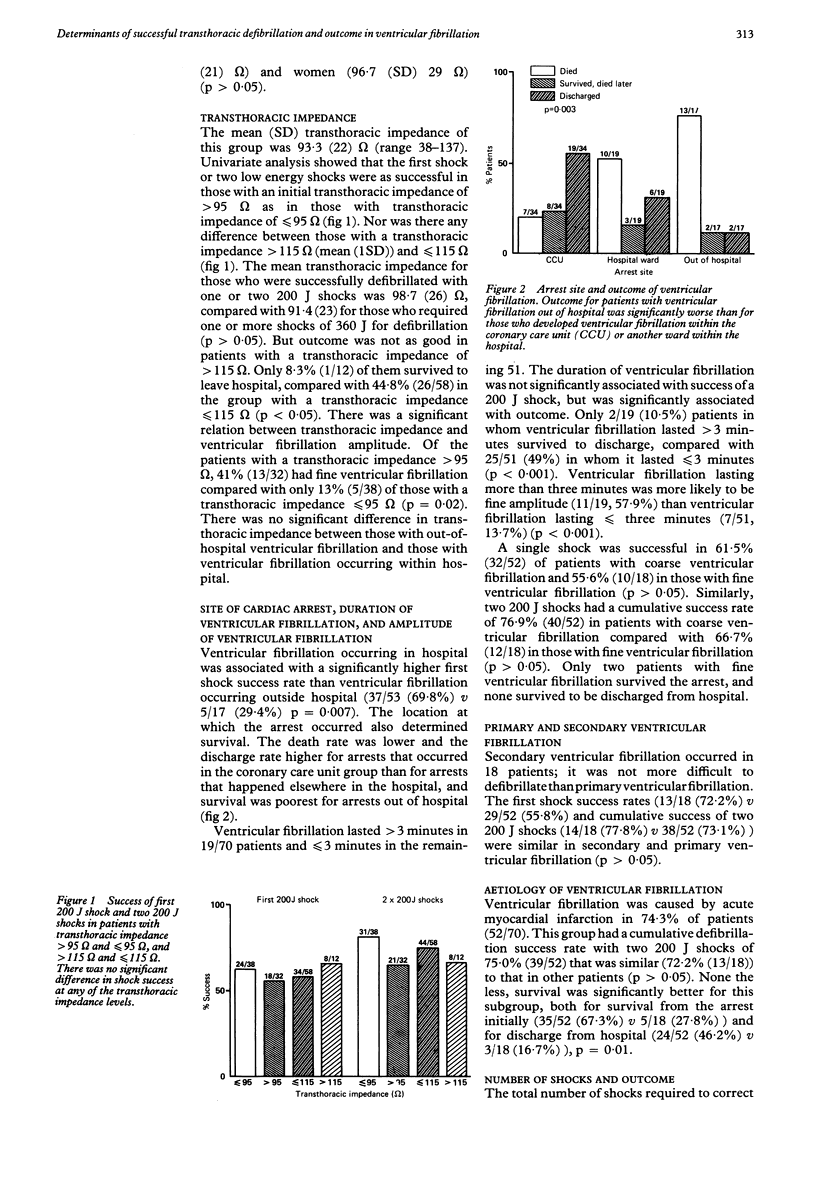

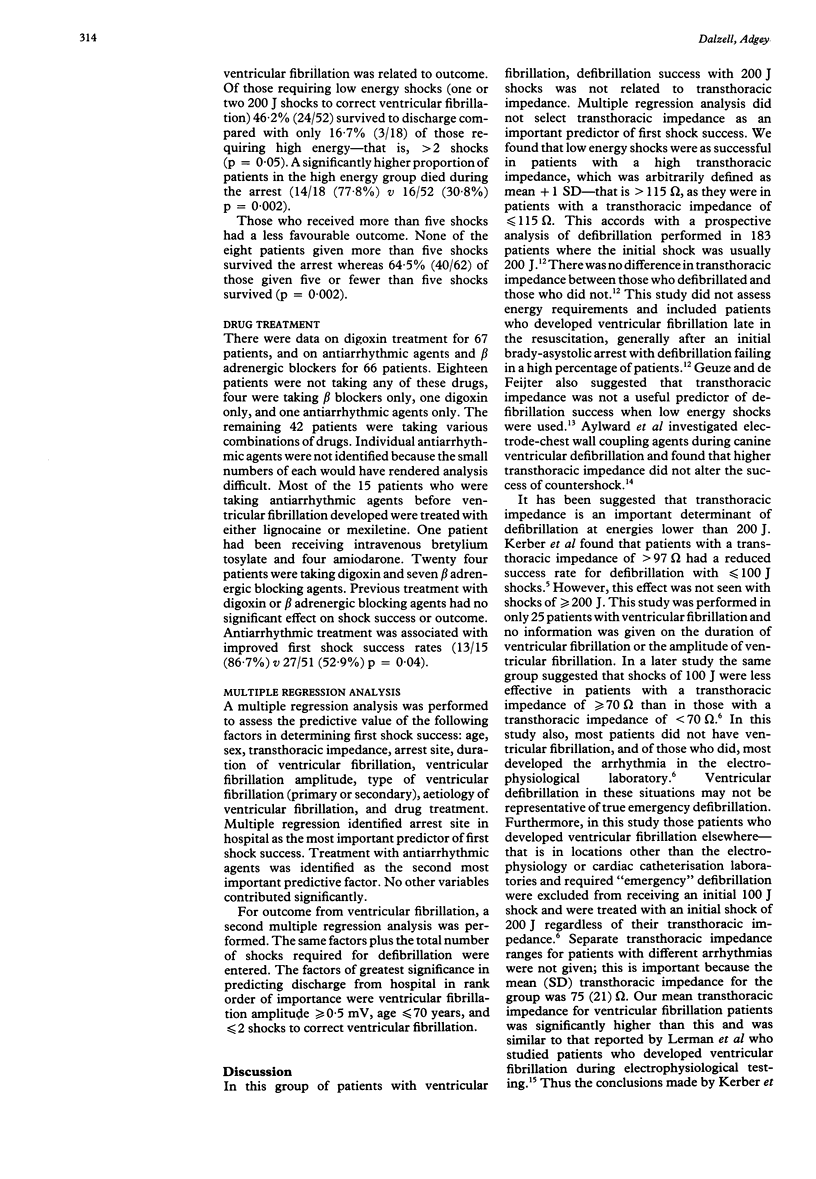

OBJECTIVE--To examine factors determining defibrillation success and outcome in patients with ventricular fibrillation. DESIGN--Observational prospective study of age, sex, transthoracic impedance, site of cardiac arrest, ventricular fibrillation duration and amplitude, primary or secondary ventricular fibrillation, aetiology, number of shocks to correct ventricular fibrillation, and drug treatment. SETTING--A teaching hospital and a mobile coronary care unit with a physician. PATIENTS--70 consecutive patients (50 male, 20 female) mean age 66.5 years. INTERVENTIONS--Before the first countershock was administered transthoracic impedance using a 30 kHz low amplitude AC current passed through 8 cm/12 cm self-adhesive defibrillator electrode pads applied in the anteroapical position was measured. The first two shocks were 200 J delivered energy (low energy) and further shocks of 360 J (high energy) were given if required. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Countershock success and outcome from ventricular fibrillation. RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS--First shock success was significantly greater in inhospital arrests (37/53) than in out-of-hospital arrests (5/17) and in those receiving antiarrhythmic treatment (13/15, 86.7%) v (27/51, 52.9%). Transthoracic impedance was similar in those who were successfully defibrillated with one or two 200 J shocks (98.7 (26) omega) and those who required one or more 360 J shocks (91.4 (23) omega). Success rates with two 200 J shocks were similar in those patients with "high" transthoracic impedance (that is, greater than 115 omega) and those with transthoracic impedance (less than or equal to 115 omega) (8/12 (67%) v 44/58 (76%]. Fine ventricular fibrillation was significantly more common in the patients with a transthoracic impedance of greater than 95 omega (41% (13/32] than in those with a transthoracic impedance less than or equal to 95 omega (13% (5/38]. Death during arrest was significantly more common in patients who needed high energy shocks (14/18 (78%] than in those who needed low energy shocks (16/52 (31%]. Multiple regression analysis identified ventricular fibrillation with an amplitude of greater than or equal to 0.5 mV, age less than or equal to 70 years, and arrests that needed less than or equal to two shocks for defibrillation, in rank order as independent predictors of survival to discharge.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aylward P. E., Kieso R., Hite P., Charbonnier F., Kerber R. E. Defibrillator electrode-chest wall coupling agents: influence on transthoracic impedance and shock success. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985 Sep;6(3):682–686. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbs C. F. Alteration of defibrillation threshold by antiarrhythmic drugs: a theoretical framework. Crit Care Med. 1981 May;9(5):362–363. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198105000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess M. J., Abildskov J. A., Millar K., Geddes J. S., Green L. S. Time course of vulnerability to fibrillation after experimental coronary occlusion. Am J Cardiol. 1971 Jun;27(6):617–621. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(71)90225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell N. P., Webb S. W., Adgey A. A., Pantridge J. F. Transthoracic ventricular defibrillation in adults. Br Med J. 1977 Nov 26;2(6099):1379–1381. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6099.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow M. S., Kluger J., DiPersio D. M., Lawrence R., Fieldman A. Antifibrillatory effects of lidocaine and bretylium immediately postcardiopulmonary resuscitation. Am Heart J. 1985 Nov;110(5):938–943. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl C. F., Ewy G. A., Ewy M. D., Thomas E. D. Transthoracic impedance to direct current discharge: effect of repeated countershocks. Med Instrum. 1976 May-Jun;10(3):151–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalzell G. W., Anderson J., Adgey A. A. Factors determining success and energy requirements for cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: revised version. Q J Med. 1991 Jan;78(285):85–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalzell G. W., Cunningham S. R., Anderson J., Adgey A. A. Initial experience with a microprocessor controlled current based defibrillator. Br Heart J. 1989 Jun;61(6):502–505. doi: 10.1136/hrt.61.6.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn H. M., McComb J. M., MacKenzie G., Adgey A. A. Survival to leave hospital from ventricular fibrillation. Am Heart J. 1986 Oct;112(4):745–751. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(86)90469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J., Sonnenblick E. H., Kirk E. S. Increased ventricular fibrillation threshold with severe myocardial ischemia. Am Heart J. 1982 Jun;103(6):966–972. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(82)90558-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes L. A., Baker L. E. The specific resistance of biological material--a compendium of data for the biomedical engineer and physiologist. Med Biol Eng. 1967 May;5(3):271–293. doi: 10.1007/BF02474537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes L. A., Tacker W. A., Cabler P., Chapman R., Rivera R., Kidder H. The decrease in transthoracic impedance during successive ventricular defibrillation trials. Med Instrum. 1975 Jul-Aug;9(4):179–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes L. A., Tacker W. A., Jr, Schoenlein W., Minton M., Grubbs S., Wilcox P. The prediction of the impedance of the thorax to defibrillating current. Med Instrum. 1976 May-Jun;10(3):159–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geuze R. H., de Feijter P. J. Evaluation of transthoracic countershock with initial energy levels up to 200 J in a coronary care unit. J Electrocardiol. 1985 Jul;18(3):251–258. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(85)80049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. L., Klein G. J. Ventricular fibrillation: the importance of being coarse? J Electrocardiol. 1984 Oct;17(4):393–399. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(84)80077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerber R. E., Grayzel J., Hoyt R., Marcus M., Kennedy J. Transthoracic resistance in human defibrillation. Influence of body weight, chest size, serial shocks, paddle size and paddle contact pressure. Circulation. 1981 Mar;63(3):676–682. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.3.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerber R. E., Jensen S. R., Gascho J. A., Grayzel J., Hoyt R., Kennedy J. Determinants of defibrillation: prospective analysis of 183 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1983 Oct 1;52(7):739–745. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90408-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerber R. E., Kouba C., Martins J., Kelly K., Low R., Hoyt R., Ferguson D., Bailey L., Bennett P., Charbonnier F. Advance prediction of transthoracic impedance in human defibrillation and cardioversion: importance of impedance in determining the success of low-energy shocks. Circulation. 1984 Aug;70(2):303–308. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.70.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerber R. E., Martins J. B., Kienzle M. G., Constantin L., Olshansky B., Hopson R., Charbonnier F. Energy, current, and success in defibrillation and cardioversion: clinical studies using an automated impedance-based method of energy adjustment. Circulation. 1988 May;77(5):1038–1046. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.5.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerber R. E., Pandian N. G., Hoyt R., Jensen S. R., Koyanagi S., Grayzel J., Kieso R. Effect of ischemia, hypertrophy, hypoxia, acidosis, and alkalosis on canine defibrillation. Am J Physiol. 1983 Jun;244(6):H825–H831. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.244.6.H825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerber R. E., Pandian N. G., Jensen S. R., Constantin L., Kieso R. A., Melton J., Hunt M. Effect of lidocaine and bretylium on energy requirements for transthoracic defibrillation: experimental studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986 Feb;7(2):397–405. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80512-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugelberg J. The interelectrode electrical resistance at defibrillation. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1972;6(3):274–277. doi: 10.3109/14017437209134810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman B. B., DiMarco J. P., Haines D. E. Current-based versus energy-based ventricular defibrillation: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988 Nov;12(5):1259–1264. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)92609-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna G., Arcidiacono R. Chemical ventricular defibrillation of the human heart with bretylium tosylate. Am J Cardiol. 1973 Dec;32(7):982–987. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(73)80168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard M. F., Labovitz A. J., Stevens L. L., Buckingham T. A., Redd R. R., Kennedy H. L. Effects of electrophysiologic studies resulting in electrical countershock or burst pacing on left ventricular systolic and diastolic function. Am Heart J. 1988 Aug;116(2 Pt 1):364–370. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90607-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacker W. A., Jr, Niebauer M. J., Babbs C. F., Combs W. J., Hahn B. M., Barker M. A., Seipel J. F., Bourland J. D., Geddes L. A. The effect of newer antiarrhythmic drugs on defibrillation threshold. Crit Care Med. 1980 Mar;8(3):177–180. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198003000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver W. D., Cobb L. A., Copass M. K., Hallstrom A. P. Ventricular defibrillation -- a comparative trial using 175-J and 320-J shocks. N Engl J Med. 1982 Oct 28;307(18):1101–1106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198210283071801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver W. D., Cobb L. A., Dennis D., Ray R., Hallstrom A. P., Copass M. K. Amplitude of ventricular fibrillation waveform and outcome after cardiac arrest. Ann Intern Med. 1985 Jan;102(1):53–55. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-1-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtczak J. Contractures and increase in internal longitudianl resistance of cow ventricular muscle induced by hypoxia. Circ Res. 1979 Jan;44(1):88–95. doi: 10.1161/01.res.44.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakaitis R. W., Ewy G. A., Otto C. W., Taren D. L., Moon T. E. Influence of time and therapy on ventricular defibrillation in dogs. Crit Care Med. 1980 Mar;8(3):157–163. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198003000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipes D. P., Fischer J., King R. M., Nicoll A deB, Jolly W. W. Termination of ventricular fibrillation in dogs by depolarizing a critical amount of myocardium. Am J Cardiol. 1975 Jul;36(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(75)90865-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]