Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors are the target of more than 30% of all FDA-approved drug therapies. Though the purinergic P2 receptors have been an attractive target for therapeutic intervention with successes such as the P2Y12 receptor antagonist, clopidogrel, P2Y2 receptor (P2Y2R) antagonism remains relatively unexplored as a therapeutic strategy. Due to a lack of selective antagonists to modify P2Y2R activity, studies using primarily genetic manipulation have revealed roles for P2Y2R in a multitude of diseases. These include inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, fibrotic diseases, renal diseases, cancer, and pathogenic infections. With the advent of AR-C118925, a selective and potent P2Y2R antagonist that became commercially available only a few years ago, new opportunities exist to gain a more robust understanding of P2Y2R function and assess therapeutic effects of P2Y2R antagonism. This review discusses the characteristics of P2Y2R that make it unique among P2 receptors, namely its involvement in five distinct signaling pathways including canonical Gαq protein signaling. We also discuss the effects of other P2Y2R antagonists and the pivotal development of AR-C118925. The remainder of this review concerns the mounting evidence implicating P2Y2Rs in disease pathogenesis, focusing on those studies that have evaluated AR-C118925 in pre-clinical disease models.

Keywords: P2Y2 receptor, AR-C118925, Inflammation, Purinome

Introduction

The cellular response to extracellular nucleotides is coordinated by a diverse cohort of receptors, including P2X ATP-gated ion channels, G protein-coupled P2Y receptors with varying ligand specificities, and G protein-coupled P1 adenosine receptors. The purinome describes this network of purinergic receptors that along with catabolic and anabolic ectoenzymes (e.g., ectonucleotidases and ecto-ATP synthases) collectively modulate purinergic signaling responses [1–4]. These purinome components have been studied in various disease contexts and indeed purinergic receptor antagonism is not a novel therapeutic strategy [5–7]. Clopidogrel (Plavix), one of the most prescribed antiplatelet drugs is a P2Y12R antagonist that serves as an anticoagulant in the prevention of cardiovascular events (e.g., myocardial infarction or stroke) for those with acute coronary syndrome and was designated an Essential Medicine by the World Health Organization in 2015 [8]. In addition to clopidogrel, ticagrelor and prasugrel are additional P2Y12R antagonists indicated for the prevention of myocardial infarction and stroke in patients with acute coronary syndrome [9]. Gefapixant, a P2X3R antagonist that was demonstrated to be moderately effective for the treatment of chronic cough in Phase III trials [10, 11], was approved by the Japan Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) for use in Japan earlier this year but was denied FDA approval in the USA [12]. Meanwhile, a new P2X3R antagonist, BLU-5937, has demonstrated greater efficacy for the treatment of chronic cough in a Phase II trial that was recently completed [13, 14]. Though there is yet to be an approved P2X7R antagonist, there have been several clinical trials investigating P2X7R antagonism as a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of inflammatory disorders (e.g., Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoarthritis) [15–18].

The human P2Y1, 2, 4, 6, 11, 12, 13, and 14 receptors are stratified by the extracellular nucleotides required for their activation and the G protein subunits they bind. Among these, the P2Y2 receptor (P2Y2R) is a known regulator of immune responses and cell repair mechanisms [19–23] that is activated equipotently by adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) or uridine 5′-triphosphate (UTP) and has been implicated in a vast array of disease pathologies. This review will focus on the therapeutic potential of P2Y2R antagonism. The most potent and selective P2Y2R antagonist yet identified, AR-C118925, became commercially available only a few years ago. As such, there have not been any clinical trials to investigate the effects of this P2Y2R antagonist and much of the work investigating P2Y2R in disease models has relied on genetic manipulations, such as P2Y2R deletion. Here we discuss the development of AR-C118925, the pre-clinical studies that have so far evaluated its therapeutic effects, and potential disease targets for P2Y2R antagonism.

P2Y2R: a unique receptor activating multiple signaling pathways

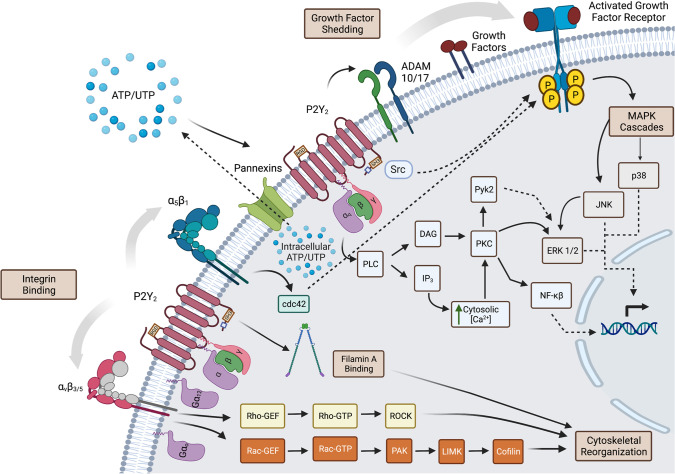

The P2Y2 nucleotide receptor, originally termed the P2U receptor, is a 377 amino acid Gq protein-coupled receptor that is activated equipotently by extracellular ATP and UTP [24]. Among P2Y receptors, the P2Y2R is unique in that it can activate five distinct signaling pathways (Fig. 1). First, like other Gq-coupled P2Y receptors, activation of P2Y2R stimulates the canonical Gαq/PLC/IP3/intracellular Ca2+ signaling pathway [25]. Second, due to an Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motif located in its first extracellular loop, P2Y2R interacts directly with αVβ3/5 and α5β1 RGD-binding integrins, resulting in the activation of the small GTPases, Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 [26–29]. We have previously demonstrated that Rho and Rac activation following integrin binding of the P2Y2R RGD motif is mediated by the heterotrimeric G proteins, Gα12 and Gαo, respectively [27, 28], which in turn activate Rho and Rac GTPase nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) [30, 31]. The precise mechanism by which direct binding between P2Y2Rs and αVβ3/5 integrins results in the activation of Gαo and Gα12 remains unknown. However, mechanisms involving G protein-binding intermediaries such as E-cadherin, Tec tyrosine kinases, and the integrin-associated protein CD47, have been proposed [26, 27, 32]. Third, intracellular Src homology 3 (SH3) binding domains found in the C-terminal tail of P2Y2R promote Src kinase autophosphorylation, leading to Src-dependent transactivation by phosphorylation of growth factor receptors in response to extracellular ATP or UTP [33–35]. This process of growth factor transactivation is also mediated by Cdc42 downstream of P2Y2R binding to α5β1 integrin [29]. Fourth, the P2Y2R C-terminus also contains a binding site that enables its direct association with the cytoskeletal protein filamin A, which promotes cytoskeletal rearrangement and cell migration [36]. Lastly, P2Y2R indirectly promotes epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling through activation of the matrix metalloproteases ADAM10 and ADAM17 [37–39], which regulate the shedding of growth factors that activate EGFR [40, 41].

Fig. 1.

P2Y2R Signaling. Activation of the P2Y2R by ATP or UTP stimulates the Gαq protein-dependent activation of phospholipase C resulting in the intracellular generation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 triggers Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, thereby increasing the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, which activates Ca2+-dependent proteins. DAG activates protein kinase C (PKC) leading to the activation of downstream proteins including the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) ERK1/2. Src-homology-3 (SH3) binding domains located in the P2Y2R C-terminus allow for the stimulation of Src-dependent transactivation of growth factor receptors and their downstream signaling molecules that regulate gene transcription and cell growth. A filamin A binding site, also located in the P2Y2R C-terminus, binds to filamin A to enable the activated P2Y2R to promote cytoskeletal rearrangement. The P2Y2R activation promotes the shedding of growth factors by activating the matrix metalloproteases ADAM10/17. Through an Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motif in its first extracellular loop, P2Y2R interacts directly with αVβ3/5 and α5β1 RGD-binding integrins, which enables P2Y2R activation to transactivate integrin signaling resulting in the Gα12- and Gαo-dependent activation of respectively Rho and Rac, and Cdc42 leading to cytoskeletal rearrangements that enhance cell migration. Created with BioRender.com

In addition to these signaling pathways, P2Y2R has been identified as a critical sensor of extracellular nucleotides (e.g., UTP, ATP) released from apoptotic cells, in turn mediating the recruitment of immune cells for the clearance of cellular debris [21]. There is growing evidence that P2Y2R-mediated immune cell recruitment promotes more than debris removal by phagocytes, and P2Y2R expression has been demonstrated in dendritic cells, eosinophils, B and T lymphocytes, macrophages, mast cells, monocytes, neutrophils, and NK cells [20, 42–48]. Additionally, P2Y2R-mediated growth factor receptor transactivation has been shown to enhance cell proliferation and upregulation of immune cell adhesion molecules (e.g., VCAM-1) [34, 49, 50]. Given the diversity of signaling and biological processes activated by P2Y2R, it is not surprising that P2Y2Rs are involved in a multitude of physiological and pathological processes.

P2Y2R: a therapeutic target

This review focuses on diseases where P2Y2R antagonism may serve as a therapeutic strategy. However, we note that the P2Y2R agonist Diquafosol has been approved for use in Japan and South Korea, but not in the USA, to treat dry eye disease [51]. Though ultimately unsuccessful, the P2Y2R agonist Denufosol has undergone multiple clinical trials to treat cystic fibrosis, including a Phase III trial that failed to demonstrate clinical benefits [52, 53]. Other selective P2Y2R agonists including Ap4A, Up4U, MRS2768, and PSB1114 [54, 55] have been used to elucidate the role of P2Y2R in physiological and pathological processes.

P2Y2R has been implicated in the pathogenesis of an array of human diseases. The pathologies we discuss in this review as potential targets for P2Y2R antagonism are grouped into six main categories: autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, fibrotic diseases, renal diseases, cancer, nervous system disorders, and pathogenic infections. Despite these groupings, all the diseases discussed in this review and the bulk of pathologies for which P2Y2R contributions have been studied involve inflammatory responses. Thus, developing effective P2Y2R antagonists for clinical applications has been an active endeavor. Initial studies with P2Y2R antagonists utilized compounds including suramin, Reactive Blue 2 (RB-2), and PSB-16133 that were either nonselective or insufficiently potent antagonists of P2Y2R function [56]. Suramin has been used as a P2Y2R antagonist experimentally and is a moderately potent inhibitor [56, 57]. However, suramin is a competitive nonselective P2YR antagonist that also inhibits the P2Y11R for which it was initially described. Further, suramin contains large negatively charged sulfonate groups and has a high molecular weight that makes it unsuitable for oral bioavailability [58]. In addition to P2Y2R, RB-2 is a potent inhibitor of several P2YRs and both RB-2 and suramin can antagonize some P2XR activities [56, 57, 59]. PSB-16133 has the greatest potency for P2Y4R but also antagonizes P2Y1R, P2Y2R, P2Y6R, and P2Y12R [56, 60]. Kaempferol, among other flavone derivatives, was shown to be a P2Y2R antagonist with an IC50 for UTP-induced calcium mobilization between 6 and 19 µM [61]. However, these studies did not ascertain the specificity of flavone derivatives for P2Y2R. Nonetheless, a group at AstraZeneca has reported the development of a potent and selective P2Y2R antagonist, AR-C118925 [62].

Development of AR-C118925

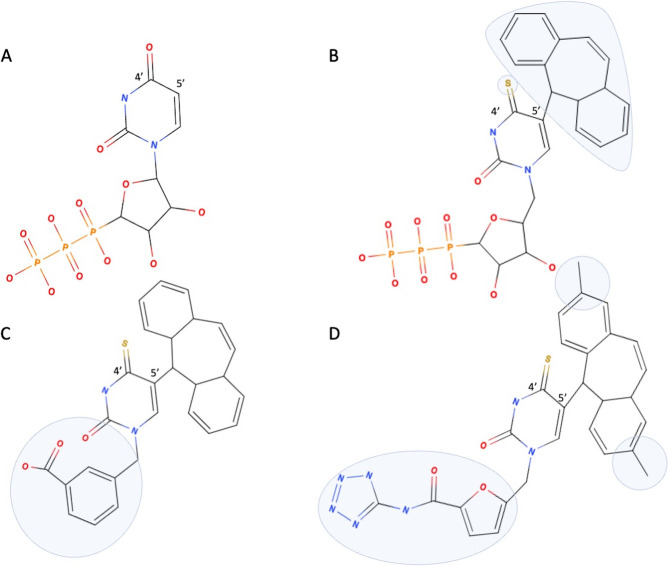

With the potential that a P2Y2R antagonist would be effective for the treatment of multiple pathologies, AstraZeneca designed AR-C118925 for selective targeting of the P2Y2R and subsequently patented the antagonist in 1998 [63]. The design of AR-C118925 used a starting template based on the structure of UTP (Scheme 1A) since this agonist is selective for P2Y2R over most P2Y and all P2X receptors [62]. Initial efforts focused on increasing metabolic stability by replacing the βγ-bridging oxygen of the UTP triphosphate moiety with a dichloromethylene group and substituting the oxygen in the 4-position of the uracil base with sulfur, among other modifications [64–66]. First, a small molecular weight molecule was developed that retained P2Y2R antagonist potency with modifications of the uracil ring that added lipophilic substituents, such as the dibenzosuberenyl group (Scheme 1B) to enhance gastric absorption [67]. Then, the replacement of the ribose 5′-triphosphate group of UTP with 3-methylenebenzoic acid produced an enhancement in antagonist potency (Scheme 1C) with the carboxylic acid group maintaining antagonist stability and minimizing molecular weight. This simplified template was amenable to further substitutions, such as the addition of symmetric methyl groups to the 5-suberenyl moiety and the addition of a monocarboxylic group to further increase antagonist activity (Scheme 1D). Ultimately, the addition of a 1-aminotetrazole at the carboxylic group of the 2-furancarboxylic acid derivative at position-1 of the 4′-thiouracil yielded the potent antagonist AR-C118925 (Scheme 1D). In summary, AR-C118925 is a potent and selective non-nucleotide antagonist of P2Y2R with favorable physiochemical characteristics (MW 537, LogD7.4 coefficient of distribution of 2.26) and pharmacokinetics [i.v. clearance (75 mL/min/kg), Vss steady-state volume of distribution of 4.34 L/kg, T1/2 2.12 h], which served as a competitive antagonist of UTP binding to the P2Y2R [62].

Scheme 1.

Major intermediates in the development of AR-C118925. (A) UTP; (B) substitution of 4-position oxygen of uracil with sulfur and addition of a dibenzosuberenyl group (blue area); (C) creation of non-nucleotide analog by replacement of the ribose 5′-triphosphate with 3-methylenebenzoic acid (blue area); (D) structure of AR-C118925 (blue area highlights symmetrical methyl groups in the 5′-suberenyl moiety and addition of the 1-aminotetrazole to the carboxylic acid of the 2-furancarboxylic acid at position-1 of the 4′-thiouracil)

Therapeutic applications for AR-C118925

In 2002, several years after AR-C118925 was patented [63], the chemical structure was presented at the 224th ACS National Meeting in Boston, Massachusetts by one of the inventors, Premji Meghani [68]. Using the structure presented at that meeting, Dr. Alan Jackson at Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research synthesized the compound and used it to evaluate the effect of P2Y2R antagonism on inhibition of mucin secretion from human bronchial epithelial cells, which was published in 2004 [69]. Subsequently, AR-C118925 did not resurface in the literature until recently. In the last five years, since AR-C118925 was made commercially available [70], there have been more than a dozen publications evaluating the effects of AR-C118925 in a variety of disease models and/or using the compound as a tool to better understand the physiological relevance of P2Y2Rs. The following sections discuss some of the most compelling evidence implicating P2Y2Rs in disease pathogenesis and report the evaluation of AR-C118925 in pre-clinical disease models (Table 1), underscoring the potential to translate P2Y2R antagonism by AR-C118925 to clinical settings.

Table 1.

Pre-clinical studies evaluating AR-C118925

| Pathology | Pre-clinical disease model | Effect of AR-C118295 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases | |||

| Sjögren’s disease (SjD) | NOD.H-2h4, IFNγ−/−, CD28−/− SjD mice | Improved salivary gland function, resolved glandular inflammation, blocked UTP-induced B cell migration and IgM secretion | [43] |

| Vascular disease | Precision‐cut lung slices from Sprague–Dawley rats | Reduced vasoconstriction of small pulmonary veins | [71] |

| Systemic sclerosis (SSc) | Human SSc dermal fibroblasts | Reduced IL-6 expression and secretion, reduced collagen I production | [72] |

| Bleomycin-induced SSc mice | Reduced bleomycin-enhanced dermal thickness and dermal fibrosis, blocked recruitment of α-SMA+ myofibroblasts, CD68+ macrophages, and CD3+ T cells to the dermis | [72] | |

| Atopic dermatitis | Fresh normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK) | Blocked ATP-induced IL-33 production and release | [73] |

| Cancers | |||

| Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) | CAL27 and FaDu human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines | Blocked EGFR and ERK1/2 phosphorylation | [37] |

| Syngeneic tumor model: murine MOC2 oral squamous cell carcinoma cells in male C57BL/6 mice | Reduced tumor growth | [37] | |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) | Human AsPC-1 pancreatic cancer cells | Reduced proliferation, blocked ATP-induced increases in glycolysis | [74] |

| Subcutaneous xenograft model: AsPC-1 human pancreatic cancer cells in athymic male nu/nu mice | Reduced tumor growth | [74] | |

| Orthotopic xenograft model: Panc02 pancreatic cancer cells injected into the pancreatic body of male C57BL/6 mice | Reduced tumor growth; demonstrated synergistic effect on reduced tumor growth and increased survival in combination with gemcitabine | [74] | |

| Inflammation-driven PDAC model via i.p. injection of cerulein | Increased normal pancreatic acinar tissue, reduced PanIN lesion area | [74] | |

| Nervous system disorders | |||

| Orofacial pain | Induced masticatory muscle inflammatory sensitization in Wistar rats via injection of CFA into the masseter muscle | Reduced bilateral mechanical hypersensitivity | [75] |

| Induced trigeminal ganglion inflammatory sensitization in Sprague–Dawley rats via unilateral injection of CFA into the temporomandibular joint | Reduced satellite glial cell activation and reversion of facial allodynia | [76] | |

Table 1 summarizes the studies that have so far evaluated AR-C118925-mediated P2Y2R antagonism in preclinical animal models or human cell studies as a potential therapeutic strategy. This table is not an exhaustive list of all pathologies for which P2Y2R may be important. The following sections will discuss additional disease contexts for which there is evidence that P2Y2R antagonism may be a potential therapeutic strategy

P2Y2R as a therapeutic target in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases

Purinergic signaling is important in the induction of both systemic and local inflammatory responses [77]. Nucleotides are released in a tightly regulated manner under physiological conditions and at high concentrations in response to inflammation and tissue damage [78], activating purinergic receptors that promote inflammatory responses. For example, studies demonstrate that eATP activates the ionotropic P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) to promote cell apoptosis and stimulate the NLRP3 inflammasome leading to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β and IL-18) [79, 80]. IL-1β release, in turn, induces NF-kB-dependent upregulation of P2Y2R [81, 82], an important mediator of immune responses [19–23]. P2Y2R activation has also been shown to be an initiator of inflammasome activation [83]. Given the extensive evidence implicating P2Y2R activity in the initiation of inflammation, a high priority was to develop a selective and potent P2Y2R antagonist for the treatment of inflammatory diseases [68]. Since P2Y2R plays a role in a variety of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, and animal models for these diseases are readily available, the effectiveness of P2Y2R antagonism by AR-C118925 in preventing these disease phenotypes has been evaluated, which we discuss in this section.

Sjögren’s disease

Sjögren’s disease (SjD), until recently referred to as Sjögren’s syndrome [84], is a chronic, inflammatory autoimmune disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of the lacrimal and salivary exocrine glands, leading to dry eye and dry mouth, respectively [85–87]. SjD is extremely sexually dimorphic with a female-to-male ratio estimated between 9:1 and 20:1 [86, 88, 89]. Despite the initiation of primary SjD in salivary and lacrimal glands, SjD is a systemic disease that ultimately impacts multiple organ systems [85, 86, 90–93]. Salivary gland hypofunction in SjD results in an increased incidence of periodontitis, dental caries, yeast and bacterial infections, and digestive disorders [94, 95] while systemic involvement (e.g., pulmonary, neural, renal, hematological, pancreatic) results in a wide range of disease symptoms and signs [85, 96–98]. In a recent quality of life (QoL) survey of SjD patients, the top three aspects of QoL that were impacted were sex life (53%), participating in extracurricular activities (52%), and work (49%) [99], underscoring the systemic nature of this disease. B lymphocytes play an important role in the pathogenesis of SjD and indicators of B cell hyperactivity in SjD include the production of autoantibodies (i.e., anti-Ro/SS-A and less frequently anti-La/SS-B antibodies), hypergammaglobulinemia, and the development of B cell lymphomas [93, 100–103]. Therapeutic options for SjD are limited to the treatment of oral and ocular dryness through topical therapies (e.g., artificial saliva and tears) and oral muscarinic agonists (i.e., pilocarpine and cevimeline) to stimulate fluid secretion from residual glandular acinar tissue as well as immunosuppression to address systemic disease symptoms using either synthetic immunosuppressive agents or biologics [85, 98] that can induce undesirable side effects. Thus, the development of novel therapies that are safe, selective, and effective in the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases is critically needed.

There are multiple mouse models of SjD with varying degrees of glandular inflammation, systemic involvement, and disease progression [104–106]. The P2X7, P2Y2, and P2X4 receptors are expressed in salivary gland epithelium and our lab has shown that P2Y2Rs are upregulated with salivary gland damage or disease, including in SjD mouse models [43, 107, 108]. We have previously shown that genetic ablation of P2Y2R attenuates salivary gland inflammation and restores salivary gland function in the IL-14α transgenic (TG) mouse model of SjD [48]. More recently, using the NOD.H-2h4, IFNγ−/−, CD28−/− mouse model of SjD, we have shown that systemic administration of AR-C118925 blocks P2Y2R function, ameliorates salivary gland inflammation, and improves salivation [43]. In both IL-14αTG and NOD.H-2h4, IFNγ−/−, CD28−/− mouse models of SjD, we detected P2Y2R expression in B lymphocytes present in the salivary glands. P2Y2Rs expressed in B lymphocytes present in salivary glands of NOD.H-2h4, IFNγ−/−, CD28−/− mice were associated with enhanced cytokine release and B cell migration, responses that could be blocked by AR-C118925 treatment [43].

Ischemic heart disease

Approximately 9 million people die from ischemic heart disease each year [109]. Atherosclerosis or arterial plaque build-up that limits blood flow is the most common cause of ischemic heart disease, also referred to as coronary artery disease [110]. Atherosclerosis is caused by factors including hypertension and insulin resistance. The P2Y2R has been shown to play an important role in the underlying causes of ischemic heart disease [111], though current evidence indicates opposing roles for the P2Y2R in disease pathogenesis [71, 112], underscoring the need for additional studies to clarify the contributions of P2Y2R to the development of atherosclerosis and ischemic heart disease.

Endothelial-specific knockout of P2Y2R in ApoE-null mice reduces atherosclerosis and vascular inflammation [111]. At the same time, the authors demonstrated that endothelial P2Y2Rs were responsible for nucleotide-induced aortic vasodilation, i.e., the dilation of the aortic ring that can lower aortic blood pressure [111]. This stands in contrast to evidence in small pulmonary veins in precision‐cut lung slices from Sprague–Dawley rats showing that the P2Y2R is responsible for ATP-induced vasoconstriction, a result that could be reversed by administration of either the non-selective P2YR antagonist, suramin, or the selective P2Y2R antagonist, AR‐C118925 [71]. These experimental differences could be explained by variations in the tissue type and vasculature (e.g., aortic artery vs. pulmonary veins) that were studied.

Providing additional evidence that P2Y2R plays a cardioprotective role, activation of P2Y2R by the administration of the selective P2Y2R agonist, MRS2768, prior to myocardial infarction in male mice leads to reduced ischemic damage to cardiomyocytes [112]. In vitro, the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) from cardiomyocytes cultured under hypoxic conditions is a measure of cardioprotection. LDH release from cardiomyocytes was enhanced by MRS2768 and blocked by AR-C118925, consistent with the hypothesis that the cardioprotective role of LDH release is due to P2Y2R activity [112]. Another study found that P2Y2R promotes cardiac regeneration via YAP activation and subsequent Hippo signaling [113]. The subject of multiple completed and ongoing clinical trials to treat patients with ischemic heart failure is the use of stem cell therapies, including c-Kit+ cardiac progenitor cells. One concern with the use of progenitor cells isolated from aged patients is their diminished proliferative and migratory potential. Compared to fast-growing cardiac progenitor cells, slow-growing progenitor cells have lower levels of P2Y2R expression, and overexpression of P2Y2R or its activation by UTP resulted in increased progenitor cell proliferation and migration. The authors concluded that enhancing P2Y2R activity may provide a means to promote the migration and proliferation of c-Kit+ cardiac progenitor cells to improve the regenerative potential of cardiac progenitor cell therapy [113].

Obesity and insulin resistance

Approximately 39% of the world’s adult population is considered to be overweight or obese [114]. Obesity is associated with elevated risks of developing other chronic conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disorders [115, 116]. Studies from one group found that P2Y2R-deficient mice were resistant to high-fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity, which resulted in a 2018 patent [117, 118]. These studies demonstrate that this result was not due to differences in food intake or intestinal absorption between P2Y2R-deficient mice and wild-type controls, but the P2Y2R-deficient mice displayed altered energy metabolism [118]. Feeding wild-type mice, but not P2Y2R-deficient mice, a HFD resulted in increased white adipose tissue with upregulated expression of P2Y2R and inflammatory cytokines [118]. The same relationship in wild-type mice was found for serum leptin, insulin, and adiponectin expression, with P2Y2R-deficient mice demonstrating no diet-induced changes in the levels of these hormones that control energy homeostasis [118]. Further underscoring these findings, P2Y2R-deficient mice fared better on insulin and glucose resistance tests. Interestingly, lipid metabolism was altered in P2Y2R-deficient mice, with elevated levels of serum triglycerides, irrespective of diet, and modifications to lipase expression including increased adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) and decreased expression of fatty acid translocase (CD36) [118].

The same group then investigated the use of the selective P2Y2R antagonist AR-C118925 in vitro [118]. When induced to differentiate and mature, preadipocytes isolated from wild-type mice demonstrated robust accumulation of triglycerides in mature adipocytes. Preadipocytes isolated from P2Y2R-deficient mice showed little triglyceride accumulation in mature adipocytes following induced maturation. These studies also demonstrated that treatment with AR-C118925 blocked triglyceride accumulation during the maturation of wild-type preadipocytes. Further, AR-C118925 was able to block the maturation of 3T3-L1 cells into mature adipocytes.

Other groups have reported corroborating evidence. Similar findings revealed that P2Y2R-deficient mice fed a HFD exhibited similar benefits on an insulin resistance test, increased liver expression of ATGL, and decreased liver expression of CD36 [119]. Another group has also shown in vitro that P2Y2Rs mediate adipocyte differentiation that could be blocked by siRNA-mediated knockdown of the P2Y2R [120].

Inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) include two related conditions, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC) [121]. UC is restricted to the colon while Crohn’s disease can affect any part of the digestive tract. UC is characterized by superficial mucosal inflammation while transmural inflammation is present in Crohn’s disease. These chronic inflammatory diseases lead to a variety of complications [121]. Grbic et al. previously reported that P2Y2R expression is increased in the colon of IBD patients as well as in the dextran sulfate sodium (DDS)-induced acute murine model of colitis [122]. Another group demonstrated upregulation of P2Y2R in a rat model of 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced chronic colitis [123].

Despite the elevated expression of P2Y2Rs in the colons of IBD patients, some data suggest that P2Y2R may play a beneficial role in the healing process. Agonism of P2Y2R has been shown to promote migration and wound healing of rat intestinal epithelial cells, which could be blocked by suramin or the expression of a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting P2Y2R [124]. And in the DDS-induced model of colitis, delivery of the potent P2Y2R agonist, 2-thioUTP (2 µg/g), directly to the distal colon resulted in improved recovery [122]. However, it is noteworthy that the DDS-induced experimental model of colitis displays acute inflammatory symptoms followed by recovery. Thus, the differences between acute and chronic models of IBD may account for these seemingly opposing roles for P2Y2R. Additionally, 2-thioUTP was administered only during the recovery phase in the DDS-induced model of colitis. Further research is needed to elucidate the potentially temporal roles of P2Y2R in IBD.

Atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is an inflammatory skin condition characterized by epidermal barrier dysfunction [125]. Because of this loss of barrier integrity, those with atopic dermatitis also tend to develop frequent allergic conditions including allergic asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, food allergies, and IgE-mediated allergic reactions [125]. These allergic exposures and reactions can also exacerbate atopic dermatitis itself. In one study investigating the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 33 (IL-33), which plays a role in atopic dermatitis pathogenesis, it was demonstrated that IL-33 release from keratinocytes in response to house dust mite (HDM) allergens exacerbates atopic dermatitis [73]. This study found that HDM-induced IL-33 expression and secretion from freshly prepared normal human keratinocytes was mediated by ATP-induced activation of the P2Y2R [73]. IL-33 release could be blocked by treatment with the nonselective P2YR antagonist, suramin, as well as the selective P2Y2R antagonist, AR-C118925. Mechanistically, it was determined that P2Y2R-mediated IL-33 expression was dependent on EGFR transactivation and ERK1/2 signaling, whereas IL-33 release was dependent on ATP-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+ levels [73].

P2Y2R as a therapeutic target in fibrotic diseases

Extracellular ATP has been shown to contribute to fibrosis development in multiple tissues [126–128]. There are several ways in which P2Y2Rs contribute to fibrosis. It has previously been shown that UTP- or ATP-induced activation of P2Y2Rs results in profibrotic responses in cardiac fibroblasts [128, 129], including their increased proliferation and migration, expression of profibrotic genes, and collagen synthesis. In a denervation-induced model of skeletal muscle atrophy and fibrosis, global knockout of P2Y2R in mice reduced fibrosis and muscle loss [130]. Primary skeletal muscle fibroblasts isolated from wild-type and P2Y2R knockout mice revealed that P2Y2R-deficient fibroblasts had reduced rates of proliferation and migration that were dependent on P2Y2R-mediated AKT, ERK, and PKC signaling compared to P2Y2R-expressing fibroblasts [130]. Additionally, agonism of P2Y2R with PSB-1114 increased proliferation and expression of profibrotic TGF-β1, CTGF, collagen 1, and fibronectin 1 in wild-type skeletal muscle fibroblasts, effects that were blocked by administration of the selective P2Y2R antagonist, AR-C118925 [130]. P2Y2Rs may also contribute to fibrosis via TGFβ-induced myofibroblast differentiation [130, 131], recruitment of profibrotic immune cells [21], activation of Rho/ROCK/myosin light chain and/or Hippo/YAP/TAZ signaling in myofibroblasts to promote their contractile activity [113, 132–135], or enhanced secretion of lysyl oxidase (LOX) family members that initiate extracellular crosslinking of collagen and elastin to promote fibrosis [136–138]. However, cystic fibrosis stands in contrast to the other fibrosis studies, which we discuss in this section. Agonism of P2Y2R has been proposed as a means to bypass the defective cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) [139] by stimulating CFTR activity via P2Y2R-mediated Gq/11/PLC signaling [140] to promote Cl− secretion from airway epithelium. This seemingly opposing result for cystic fibrosis may be explained by the dual role of P2Y2R in stimulating signaling cascades that promote exocrine secretion in addition to fibroblast activation that is responsible for fibrosis development.

Systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) or scleroderma, is a rheumatic disease that results in fibrosis of the skin and internal organs as well as microvasculature dysfunction [141]. Perera et al. isolated dermal fibroblasts from skin biopsies of patients with diffuse cutaneous-type SSc and healthy controls and demonstrated that ATP causes increased expression and subsequent secretion of IL-6 in SSc fibroblasts to a much greater extent than in control fibroblasts [72]. IL-6 is also elevated in the serum of patients with early SSc [142, 143], and blockade of IL-6 signaling by treatment with an anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, reduced disease symptoms in a bleomycin-induced SSc mouse model [144], underscoring the importance of this cytokine in SSc pathogenesis. Interestingly, the IL-6-induced responses were blocked by the nonselective P2YR antagonists, suramin and kaempferol, or the highly selective P2Y2R antagonist AR-C118925, which reduced the recruitment of α-smooth muscle actin-expressing (SMA+) myofibroblasts, CD68+ macrophages, and CD3+ T cells to the dermis [72].

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive, fibrotic interstitial lung disease with no known cause [145]. IPF has a poor prognosis, though the FDA approval of two anti-fibrotic drugs, pirfenidone, a drug with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects that blocks the production of pro-fibrotic cytokines, and nintedanib, a broad spectrum tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks VEGF, FGF, and PDGF receptor functions among other activities [146, 147], has encouraged current clinical trials that show promising results for the management of IPF symptoms [148]. IPF patients also have elevated ATP levels in broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) fluid collected during bronchoscopy [149]. Additionally, P2Y2Rs are upregulated in macrophages isolated from BAL fluid and neutrophils collected from the blood of IPF patients compared to healthy controls [149]. In a bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis mouse model, extracellular ATP levels and P2Y2R expression were similarly elevated. Following bleomycin administration, P2Y2R-deficient mice develop less pulmonary fibrosis as well as reduced recruitment of macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils to the lung than wild-type mice [149]. Additionally, this same study revealed that in both murine and human fibroblasts, P2Y2R activation results in increased fibroblast proliferation and pro-fibrotic IL-6 secretion.

P2Y2R as a therapeutic target in renal diseases

P2Y2Rs are expressed in multiple cell types that comprise the kidney and are involved in proper kidney function [150]. However, there is also evidence of a role for P2Y2R in the development of renal diseases [151, 152], including compelling studies on glomerulonephritis and diabetic nephropathy, which we describe in this section. However, these studies have only utilized P2Y2R-deficient mice; to our knowledge, there have not yet been any studies investigating AR-C118925 administration as a therapeutic strategy in any renal disease models.

Glomerulonephritis

Glomerulonephritis (GN) is inflammation of the glomerulus, the blood-filtering portion of the kidneys. There are multiple causes of glomerulonephritis. GN can occur following infections, often with Staphylococcus aureus or the group A, β-hemolytic Streptococcus species, though GN can also occur following other infections [153]. GN is also associated with autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus [154], Goodpasture’s syndrome [155], IgA nephropathy [156], or SjD [157, 158]. GN can drive the development of dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease (ESRD), which affects approximately 15% of the US population [159].

One mouse model of GN is induced by the intravenous injection of nephrotoxic serum (NTS). Using this NTS-induced mouse model, Rennert et al. have shown that urine ATP levels were elevated compared to vehicle-injected control mice and that hydrolysis of ATP catalyzed by administration of the enzyme apyrase diminishes GN symptoms in NTS-treated mice [160]. Similarly, the nonselective P2YR antagonist, suramin, blocked NTS-induced GN. This study showed that NTS leads to an increase in P2Y2R expression in the kidney and that P2Y2R-deficient (P2Y2R−/−) mice develop a less severe disease phenotype following NTS administration. Impressive evidence from this publication using the bone-marrow chimera model demonstrates that after bone-marrow ablation via irradiation followed by reconstitution of the bone marrow in wild-type mice with bone marrow isolated from P2Y2R−/− mice, and vice versa, P2Y2R expression in kidney-infiltrating leukocytes is responsible for the responses to NTS rather than renal cells expressing P2Y2Rs [160].

Diabetic nephropathy

Diabetic nephropathy, the reduction or loss of kidney function, is often a complication of diabetes mellitus [161] and eventually progresses to ESRD. One of the most common models for murine diabetes is the streptozotocin (STZ)-induced model [162]. STZ is an antibiotic that depletes pancreatic islet β cells and can generate models of either Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes mellitus, depending on the protocol of STZ administration [162]. Unilateral nephrectomy is used to mimic renal failure in mice [163]. Dusabimana et al. combined STZ-induction, unilateral nephrectomy, and a HFD in male C57BL/6 mice to generate a model of diabetic nephropathy (DN mice) [164, 165]. P2Y2R-deficient DN mice lack plasma and urinary markers of kidney damage [165]. Glomerular sclerosis and podocyte loss in P2Y2R-deficient DN mice were decreased as were other characteristics of diabetic nephropathy including tubular cell apoptosis and interstitial fibrosis. The authors further show that P2Y2R-deficiency in DN mice results in reduced renal cell apoptosis and increased autophagy. Decreased autophagy is known to contribute to the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy [166]. Subsequent mechanistic studies indicate that decreased AKT/FOXO3a signaling in kidney tissue of P2Y2R-deficient mice increases autophagy [165].

P2Y2R as a therapeutic target in cancer

The study of P2Y2R in the context of cancer has been complicated by the pleiotropic role of ATP due to its activity in both the tumor and the host tissue microenvironment [3, 167]. To be able to appreciate this complexity and per the subject matter of this review, we will focus on studies that investigated P2Y2R antagonism utilizing human samples and in vivo mouse models of tumor growth. P2Y2R activation elicits multiple downstream signaling events associated with tumorigenesis, metastasis, and the development of chemotherapeutic drug resistance [3]. These responses include the activation of the MAPK cascade, AP1-regulated genes, the EGFR via growth factor shedding, and Rac and Rho signaling cascades [3] (see Fig. 1). With the ability of P2Y2R to use outside-in signaling initiated by extracellular nucleotides to upregulate pro-survival mechanisms, it is no surprise that P2Y2R has become a therapeutic target for the treatment of various cancers.

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

Carcinomas, the most common cancer type, are epithelial in origin and develop in the skin or tissues that line internal organs [168]. Head and neck cancers are consistently ranked among the top 10 most common cancers worldwide, with the majority being classified as head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) [169]. Our laboratory has previously demonstrated in human Cal27 and FaDu HNSCC cell lines and murine MOC2 oral cancer cells that P2Y2R activation leads to ERK1/2 and EGFR activation [37]. Though tumor resection and cisplatin-based chemoradiation remain the standard of care for HNSCCs and other cancers, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), such as the FDA-approved cetuximab, have proven to be beneficial in treating HNSCC [168, 170]. Additionally, EGFR-targeted small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as the FDA-approved Osimertinib, have been utilized for blocking EGFR mutants that induce non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) in humans [171], but have demonstrated limited success in Phase I-III clinical trials for human HNSCC [172–174]. Despite evidence that ~ 90% of HNSCC biopsies overexpress EGFR [175], targeted EGFR therapeutics have proven unsuccessful, in part because of acquired drug resistance [176, 177]. Our findings using both human Cal27 and FaDu HNSCC cell lines and murine MOC2 oral cancer cells suggest that P2Y2R represents an alternative pathway for EGFR activation and that targeting the P2Y2R may prove more effective in the treatment of HNSCCs than EGFR-targeted therapies [37].

In vivo, we have utilized human Cal27 and FaDu xenograft models and the MOC2 syngeneic mouse oral cancer model to investigate the role of P2Y2Rs in oral cancer progression. Our results demonstrate that genetic ablation of P2Y2Rs in Cal27 and FaDu xenografts slows tumor growth [37]. We have also shown that pharmacological antagonism of the P2Y2R using AR-C118925 inhibits the growth of MOC2 tumors in male C57BL/6 mice [37]. Taken together, these studies highlight the therapeutic potential of P2Y2R antagonism for the treatment of HNSCCs.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

P2YRs are widely expressed in hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, and epithelial cells [178]. The P2Y2R has been shown to regulate physiological hepatocyte proliferation as well as contribute to liver pathologies including fibrosis, hepatitis, and hepatocarcinogenesis [179–183]. The P2Y2R is also highly expressed in human hepatoma cell lines [179]. Schulien et al. investigated the functional relevance of P2Y2R in hepatocarcinogenesis [183]. Using a diethylnitrosamine-induced model of hepatocarcinogenesis in P2Y2R knockout (P2y2r−/−) and C57BL/6 (P2y2r+/+) mice, they demonstrated roles for the P2Y2R in tumorigenesis and protein expression of the AP-1 transcription factor c-JUN, a regulator of liver regeneration [184], but not glucose metabolism [183]. Their data demonstrate that at 8–10 months post hepatocarcinogenesis induction, P2y2r−/− mice had lower tumor burdens compared to their wild-type counterparts. Experiments to study tumor initiation showed that the P2Y2R does not cause liver cell inflammation or death at the early stages of tumorigenesis. However, at later stages of tumor progression, semiquantitative analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells revealed an increase in F4/80+ macrophages and monocytes in P2y2r+/+ mice compared to P2y22r−/− mice, indicating that P2Y2R may play a role in immune cell recruitment. Chemical carcinogenesis via diethylnitrosamine-induced DNA damage was exacerbated by the administration of ATP and reduced in mice that lacked P2Y2R. By analyzing the expression of genes related to genotoxic stress following diethylnitrosamine administration, it was demonstrated that P2Y2R promotes DNA damage in this hepatocarcinoma model. Additional in vitro experiments determined that extracellular ATP promotes hepatocellular DNA damage in a P2Y2R- and calcium-dependent manner [183].

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Evidence indicates that patients with adenocarcinomas of glandular tissues may also benefit from antagonism of the P2Y2R. Hu et al. conducted a bioinformatic analysis of human datasets and used immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of tumor samples from 264 patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and healthy controls [74]. These bioinformatic and IHC studies found that high P2Y2R expression in PDACs correlates with decreased survival of PDAC patients. PDAC is a highly aggressive malignancy with a 5-year survival of less than 10% [185]. The poor prognoses associated with PDAC may be attributable to limited treatment options and a relatively low frequency of early detection.

Hu et al. determined that AR-C118925 reduces human AsPC-1 pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and inhibits ATP-induced increases in glycolysis [74]. The effects of AR-C118925 administration were analyzed in three distinct mouse models of PDAC. First, AsPC-1 cells were subcutaneously injected into athymic male nu/nu mice, where AR-C118925 was found to reduce tumor growth. Second, they utilized an orthotopic xenograft model in which Panc02 pancreatic cancer cells were injected into the pancreatic body of male C57BL/6 mice to demonstrate that AR-C118925 treatment reduced the tumors and acted synergistically with the nucleoside analog gemcitabine to decrease tumor growth and increase mouse survival. Finally, an inflammation-driven PDAC model was generated by intraperitoneal injection of cerulein, an analog of the peptide hormone cholecystokinin that induces the production of reactive oxygen species and the appearance of chronic pancreatitis that leads to the development of PDAC [186, 187]. In this model, AR-C118925 increased normal pancreatic acinar tissue area and reduced the area of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) lesions. This significant study using three distinct in vivo animal models as well as a robust human dataset supports the important role of P2Y2R in PDAC development and further encourages the evaluation of AR-C118925 to treat this highly lethal form of cancer [74].

Breast adenocarcinoma and prostate carcinoma

Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), have been implicated in growth and metastasis [188, 189] in which a role for P2Y2R has been linked to the regulation of adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and VE-cadherin in breast adenocarcinoma [190] and E-cadherin and Claudin-1 in prostate carcinoma [191]. Using shRNA to downregulate P2Y2R in the human breast adenocarcinoma cell line, MDA-MB-231, followed by their injection into athymic mice, it was demonstrated that resulting tumors grew more slowly and produced significantly fewer lung metastases than the injection of control cells [190]. Similar findings have been reported using highly metastatic human prostate carcinoma cells (1E8 subclone of PC-3 M cell line) in which siRNA-mediated knockdown of P2Y2R resulted in decreased invasion and migration in vitro and tumor growth and metastasis in vivo due to decreased P2Y2R-dependent expression of the CAMs E-cadherin and Claudin-1 [191].

P2Y2R as a therapeutic target in nervous system disorders

Activation of P2X and P2Y receptors by extracellular nucleotides in the central nervous system regulates a wide range of physiological and pathological processes [192]. The P2Y2R is expressed in murine neurons, astrocytes, and microglia [192] and upregulated in models of spinal cord and accumbens injury [193, 194]. Several studies have revealed the relevance of P2Y2R to normal CNS development and neuroinflammation [195–198], including orofacial pain and Alzheimer’s disease discussed in this section.

Orofacial pain

The trigeminal ganglion (TG) is involved in the development of inflammatory and neuropathic orofacial pain. The TG is composed of clusters of sensory neurons wrapped by satellite glial cells (SGCs) and axonal processes surrounded by Schwann cells [199]. In one study, the application of the pro-algogenic neuropeptide Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) caused selective upregulation of ADP-activated P2Y1Rs and UTP-activated P2Y2Rs in SGCs [76]. It was previously demonstrated that in co-cultures of neurons and SGCs, the neuronal release of CGRP caused an increase in both responses to ADP and UTP in SGCs [200]. It was also shown that neuronal release of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) was responsible for the observed elevated expression of P2Y1Rs and P2Y2Rs in SGCs [76]. Using a rat model of induced TG inflammatory sensitization by unilateral injection of complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) into the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), it was found that P2Y1Rs were upregulated 10 days post-CFA injection while P2Y2Rs were initially downregulated and then upregulated 1-week post-injection, with peak expression around 8 days. These results mirror the timeline for SGC activation and demonstrate that pro-algogenic conditions modulate P2YR expression in vivo as well as in vitro. Studies with the P2Y1R-selective antagonist MRS2179, the P2Y2R-selective antagonist AR-C118925, and the non-selective P2R antagonist PPADS revealed antagonism of the P2Y2R, but not the P2Y1R, blocks SGC activation and decreases orofacial pain [76].

Studies by Knežević et al. utilized an induced model of masticatory muscle (MM) hypersensitivity and inflammation caused by unilateral intramasseteric injection of CFA to demonstrate that P2Y2Rs are required for MM pain transmission in Wistar rats [75]. Results showed that P2Y2Rs were upregulated in the TG following CFA injection in rats and that intramasseteric injection of AR-C118925 relieved CFA-induced MM hypersensitivity, but there was no change in uninjected controls [75]. Taken together, these studies reveal a role for P2Y2Rs in orofacial pain transmission and suggest that P2Y2R antagonism offers new opportunities for blunting pain in these patients.

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative, neuroinflammatory disease characterized by the presence of extracellular amyloid β-protein (Aβ) deposition in the brain and intracellular tau neurofibrillary tangles [201]. Despite decades of research, the pathogenesis of AD is not fully understood. As well-established initiators of neuroinflammatory responses, microglia play an important role in AD pathogenesis, though that role appears to be temporal, with protective roles early on and deleterious roles at later disease stages [202–204]. Several groups have concluded that microglia are important for the clearance of Aβ plaques, suggesting that impaired microglial activity may account for disease pathogenesis [204, 205], whereas others have convincingly demonstrated that Aβ plaque deposition relies on microglial activity and that ablation of microglia with PLX3397, a colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) inhibitor, reduces plaque formation [206].

We have previously reported that the P2Y2R is upregulated in rat and mouse primary cortical neurons in response to exogenous IL-1β [81, 82]. In a 2018 meta-analysis, peripheral IL-1β levels were found to be significantly elevated in AD patients compared to controls [207]. Studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that IL-1β-induced P2Y2R upregulation promotes neurite extension and amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing [39, 81, 82]. Neither of these processes was a result of P2Y2R-mediated canonical Gq protein signaling. Our studies demonstrate that cofilin phosphorylation and subsequent neurite extension were dependent on the association of P2Y2R with RGD-binding integrins via an RGD-domain in the first extracellular loop of the P2Y2R, and UTP-induced cofilin phosphorylation could be blocked by an αV integrin blocking antibody or by inhibitors of downstream ROCK signaling [81]. We also found that P2Y2R activation promotes APP processing by activation of α-secretase, a metalloprotease that catalyzes the release of the non-amyloidogenic peptide sAPPα from APP [39, 82]. Neither blockade of Gq-mediated PKC signaling, nor downregulation of PKC affected P2Y2R-mediated sAPPα production. However, pharmacological blockade or siRNA targeting of the metalloproteases ADAM10 and ADAM17 (i.e., α-secretases) diminishes P2Y2R-mediated, non-amyloidogenic APP processing, indicating that ADAM10/17-mediated sAPPα generation from APP likely prevents the generation by other metalloproteases (i.e., β-secretase) of neurotoxic Aβ from APP [82]. Further supporting a role for the P2Y2R in AD, we have shown that UTP-induced P2Y2R activation results in the phagocytosis and subsequent degradation of amyloidogenic Aβ1–42 by primary mouse microglial cells [208].

P2Y2R expression is upregulated in the cerebral cortex of the TgCRND8 mouse model of AD at 10 weeks of age and decreases after 25 weeks of age [209]. Interestingly, heterozygous P2Y2R deletion (P2Y2R+/−) in the TgCRND8 mouse results in elevated Aβ1–42 levels, Aβ plaque deposition, and reduced expression of the microglial cell marker CD11b in the cerebral cortex, and enhanced neurological deficits compared to TgCRND8 mice fully expressing the P2Y2R (P2Y2R+/+). These P2Y2R+/− mice only survive approximately 12 weeks, whereas homozygous P2Y2R deletion (P2Y2R−/−) in TgCRND8 mice results in a lifespan of only about 25 days [209]. These data support the hypothesis that the decrease in microglial cells in the AD brain due to P2Y2R deletion enhances Aβ plaque formation and accelerates disease progression due to the loss of Aβ-phagocytosing microglia.

P2Y2R as a therapeutic target in pathogenic infections

As has been discussed, P2Y2Rs mediate immune responses in a wide range of inflammatory diseases and may play an important role in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammation that may be treatable with P2Y2R antagonists. P2Y2Rs have also been implicated in mediating immune responses to pathogenic infection [210] as well as viral entry in host cells of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hantaviruses. For both HIV and hantaviruses, P2Y2R antagonists may be beneficial to preventing these infections, whereas P2Y2R may play a protective role against pneumococcal lung infections in mice that might be better treated with P2Y2R agonists [211].

HIV infection

The first step in HIV viral entry involves membrane fusion, which depends on an HIV envelope glycoprotein (gp) complex [212]. Trimeric gp160 undergoes cleavage by a furin-like host protease, yielding the receptor-binding fragment gp120, and a fusion fragment gp41. The mature HIV envelope protein (Env) consists of a complex containing three gp120 and three gp41 subunits [212]. The C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) and C–C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) function as co-receptors for HIV-1 viral entry into CD4+ T cells [213, 214]. A study by Séror et al. showed that binding of HIV-Env to CD4 and CXCR4 mediates the release of ATP by pannexin-1 hemichannels [215]. To determine which P2 receptors mediate HIV viral entry, individual P2 receptor subtypes were deleted in CD4+CXCR4+ target cells and the results indicated that loss of P2Y2Rs results in a pronounced reduction in Env-triggered syncytium formation, i.e., the fusion of multiple cells that occurs during viral infection. Upon HIV-1 infection of human PBMCs and CD4+CXCR4+ HeLa cells, it was demonstrated that P2Y2R protein levels rapidly increase [215]. Further, lymph node and frontal cortex biopsies from HIV-infected patients reveal elevated P2Y2R expression [215]. Pharmacological antagonism of P2Y2Rs with kaempferol or siRNA knockdown of P2Y2R inhibited HIV-1 infection and HIV-induced cell death of CD4+CXCR4+ cells isolated from the PBMCs of healthy volunteers [215]. It was also determined that overexpression of P2Y2R increases the fusion of Env+ with CD4+CXCR4+ T cells [215].

As previously reported, pannexin-1 hemichannels are essential for HIV infection [216]. Séror et al. demonstrated that in addition to depletion or blockade of P2Y2Rs, pharmacological inhibition of pannexin-1 results in less HIV-1 infection and CD4+ T cell depletion [215]. It was further demonstrated that downstream of pannexin-1 and P2Y2R activation, membrane fusion of Env+ with CD4+CXCR4+ cells depends on P2Y2R-mediated activation of proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2) kinase and the transient plasma membrane depolarization that follows [215]. Though pannexin-1-mediated ATP release results in broad P2R activation, including of the P2Y2R, there is evidence that P2Y2R activation promotes pannexin-1 activation [217]. Together, these studies demonstrate that blockade of any component of the pannexin-1/P2Y2R/Pyk2 signaling pathway inhibits membrane fusion of Env+ with CD4+CXCR4+ T cells.

The native CCR5 ligand RANTES (i.e., regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted), blocks HIV-1 entry. Providing additional evidence that P2Y2R may be important for HIV viral entry, ATP-induced stimulation of CCR5-expressing HEK293T cells results in increased RANTES-induced Ca2+ flux, an effect that was blocked by treatment with AR-C118925, suramin, apyrase, and other purinergic signaling inhibitors [218]. The authors propose a mechanism by which P2Y (and P2X) receptors work with CCR5 to amplify their ATP-induced responses [218]. Thus, the use of AR-C118925, perhaps with other purinergic receptor antagonists, may provide therapeutic approaches to inhibit HIV entry.

Hantavirus infection

Pathogenic hantavirus infection, such as with Sin Nombre virus (SNV), can result in serious complications, including hemorrhagic fever and renal syndrome (HFRS) and hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS) [219]. SNV replicates primarily in the vascular endothelium of a range of tissues. Pathogenic hantaviruses bind to the plexin-semaphorin-integrin (PSI) domain of β3 integrin subunits of inactive αvβ3 and αIIbβ3 integrins [220]. Because previous studies demonstrate that P2Y2Rs interact with αVβ3/5 and α5β1 RGD-binding integrins through the RGD motif located in the first extracellular loop of P2Y2R [26–29], Bondu et al. hypothesized that P2Y2Rs might mediate SNV uptake by interacting with the same integrins required for SNV uptake. Results obtained demonstrate that P2Y2Rs bind the inactive, bent form of the PSI domain of β3 integrin [221]. Using CHO-K1 cells and atomic force microscopy (AFM) to measure αIIbβ3-RGD interactions, they found that overexpression of wild-type human P2Y2R, but not a mutant P2Y2R in which the RGD domain is replaced with RGE that does not bind integrins, results in a much higher frequency of adhesion to the AFM probe and requires a much higher force for unbinding [221]. It was also shown that SNV had a higher affinity for the αIIbβ3 PSI-P2Y2R complex than αIIbβ3 alone.

P2Y2Rs are upregulated in lung tissues isolated from HCPS decedents [222], with the highest elevation observed in lung macrophages from these tissues. Immunohistochemical analyses revealed co-staining of P2Y2R with SNV antigen, suggesting that elevated P2Y2R levels lead to increased viral burden. Though additional studies are needed, these findings suggest that antagonizing the P2Y2R following SNV exposure may serve as a means to minimize SNV infection and prevent HCPS.

Future directions and conclusions

The studies evaluated in this review underscore the multiple opportunities for testing P2Y2R antagonism as a clinical approach in humans for treating degenerative chronic inflammation in a variety of diseases and pathogenic conditions. The early successes with the selective P2Y2R antagonist AR-C118925 that blocks these inflammatory responses in pre-clinical disease models, strongly encourage further testing of this compound in clinical settings. Additionally, for many of the pathologies reviewed here no effective therapies currently exist, supporting further evaluation of this compound. However, additional research is needed to reconcile potentially opposing roles for P2Y2R antagonism in some disease contexts that may be explained by species or model differences, differential effects of antagonism on involved cell types, or temporal effects of P2Y2R antagonism during the disease course. We recognize that systemic P2Y2R antagonism in humans may block important P2Y2R-mediated physiological functions in non-diseased tissues leading to undesirable side effects. Accordingly, future studies on localized administration of AR-C118925 in diseased tissues should be undertaken. There are currently three patents for the use of the P2Y2R antagonist AR-C118925 as a therapeutic intervention in human disease. The patents describe the use of P2Y2R antagonism to prevent diet-induced obesity [117], IBD [223], and tumor metastasis by blocking neutrophil migration to the tumor microenvironment and/or sites of metastases [224].

In addition to translational applications, given its specificity and utility, researchers have used AR-C118925 as a starting point for developing new molecular tools to further research P2Y2R signaling [225]. By evaluating the structure–activity relationships of P2Y2R antagonists, Conroy et al. generated two new structural analogs with predicted improved physicochemical properties as P2Y2R antagonists [225]. These studies have led to the addition of BODIPY fluorophores (BODIPY A with a 628 nm absorption max and 642 nm emission max or BODIPY B with a 503 nm absorption max and 509 nm emission max) that serve as P2Y2R-binding fluorescent ligands, which can be used for bioluminescence-resonance-energy-transfer (BRET) P2Y2R ligand-binding assays as well as confocal microscopy [225]. Additional studies measured the effect of the fluorescent ligands on UTP-induced Ca2+ mobilization in P2Y2R-expressing human 1321N1 astrocytoma cells and revealed micromolar affinities for these new fluorophore-conjugated compounds in a BRET assay [225].

In conclusion, the studies discussed above indicate that AR-C118925 is a potent and P2Y2R-selective antagonist with potential clinical applications in treating a wide variety of chronic inflammatory diseases. Based on the research presented, it is apparent that this compound and its potential derivatives will be very useful for future investigations on the physiological and pathological responses coupled with the activation of P2Y2Rs.

Kimberly J. Jasmer

graduated with a B.S. in Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology from the University of Washington and a Ph.D. in Biological Sciences from the University of Missouri. She is currently an Assistant Research Professor of Biochemistry at the University of Missouri. She studies the immunopathogenesis of salivary gland disorders, namely autoimmune Sjögren’s Disease (SjD) and chronic hyposalivation as a collateral side effect of radiotherapy for head and neck cancers. Specifically, these studies have investigated the role of P2X7 and P2Y2 receptors and their extracellular nucleotide ligands in mediating disease pathogenesis. Dr. Jasmer aims to translate her research into effective therapeutic strategies for the treatment of salivary gland dysfunction.

Author contribution

All authors developed the idea for this review. KJJ and KMF performed literature searches, KJJ and KMF drafted the manuscript, and KJJ, LTW, SC, and GAW critically revised the draft.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grants R01DE007389 (GAW), R01DE023342 (GAW), R01DE029833 (GAW, SC, KJJ), and R21AR079693 (SC) and a Sjögren’s Foundation grant (KJJ, SC). KMF is supported by a University of Missouri Life Sciences Fellowship and the Wayne L. Ryan Foundation Fellowship from the Ryan Foundation.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Di Virgilio F, Sarti AC, Falzoni S, De Marchi E, Adinolfi E. Extracellular ATP and P2 purinergic signalling in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(10):601–618. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuccarini M, Giuliani P, Ronci M, Caciagli F, Caruso V, Ciccarelli R, et al. Purinergic signaling in oral tissues. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(14):7790. doi: 10.3390/ijms23147790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woods LT, Forti KM, Shanbhag VC, Camden JM, Weisman GA. P2Y receptors for extracellular nucleotides: contributions to cancer progression and therapeutic implications. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;187:114406. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volonte C, D’Ambrosi N. Membrane compartments and purinergic signalling: the purinome, a complex interplay among ligands, degrading enzymes, receptors and transporters. FEBS J. 2009;276(2):318–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray JM, Bussiere DE. Targeting the purinome. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;575:47–92. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-274-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang Z, Xie N, Illes P, Di Virgilio F, Ulrich H, Semyanov A, et al. From purines to purinergic signalling: molecular functions and human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):162. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00553-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khalafalla MG, Woods LT, Jasmer KJ, Forti KM, Camden JM, Jensen JL, et al. P2 Receptors as therapeutic targets in the salivary gland: from physiology to dysfunction. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:222. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kishore SP, Blank E, Heller DJ, Patel A, Peters A, Price M, et al. Modernizing the World Health Organization list of Essential Medicines for preventing and controlling cardiovascular diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(5):564–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schupke S, Neumann FJ, Menichelli M, Mayer K, Bernlochner I, Wohrle J, et al. Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1524–1534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith JA, Kitt MM, Morice AH, Birring SS, McGarvey LP, Sher MR, et al. Gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist, for the treatment of refractory or unexplained chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, controlled, parallel-group, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(8):775–785. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30471-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGarvey LP, Birring SS, Morice AH, Dicpinigaitis PV, Pavord ID, Schelfhout J, et al. Efficacy and safety of gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist, in refractory chronic cough and unexplained chronic cough (COUGH-1 and COUGH-2): results from two double-blind, randomised, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2022;399(10328):909–923. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02348-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markham A. Gefapixant: first approval. Drugs. 2022;82(6):691–695. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01700-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith JLM, Birring SS, Morice AH, Sher MR, Dicpinigaitis P, Blaiss M, Lanouette S, Harvey L, Yang R, Shaw J, Garin M, Bonuccelli CM (2022) Safety and efficacy of BLU-5937 in the treatment of refractory chronic cough from the phase 2b soothe trial. American Thoracic Society International Conference, San Francisco

- 14.Garceau D, Chauret N. BLU-5937: a selective P2X3 antagonist with potent anti-tussive effect and no taste alteration. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2019;56:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stock TC, Bloom BJ, Wei N, Ishaq S, Park W, Wang X, et al. Efficacy and safety of CE-224,535, an antagonist of P2X7 receptor, in treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis inadequately controlled by methotrexate. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(4):720–727. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drill M, Jones NC, Hunn M, O'Brien TJ, Monif M. Antagonism of the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor: a potential therapeutic strategy for cancer. Purinergic Signal. 2021;17(2):215–227. doi: 10.1007/s11302-021-09776-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keystone EC, Wang MM, Layton M, Hollis S, McInnes IB, Team DCS Clinical evaluation of the efficacy of the P2X7 purinergic receptor antagonist AZD9056 on the signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis in patients with active disease despite treatment with methotrexate or sulphasalazine. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(10):1630–1635. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-143578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eser A, Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S, Vogelsang H, Braddock M, et al. Safety and efficacy of an oral inhibitor of the purinergic receptor P2X7 in adult patients with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease: a randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind. Phase IIa study Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(10):2247–2253. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacob F, Perez Novo C, Bachert C, Van Crombruggen K. Purinergic signaling in inflammatory cells: P2 receptor expression, functional effects, and modulation of inflammatory responses. Purinergic Signal. 2013;9(3):285–306. doi: 10.1007/s11302-013-9357-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Idzko M, Ferrari D, Eltzschig HK. Nucleotide signalling during inflammation. Nature. 2014;509(7500):310–317. doi: 10.1038/nature13085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott MR, Chekeni FB, Trampont PC, Lazarowski ER, Kadl A, Walk SF, et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461(7261):282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrari D, la Sala A, Panther E, Norgauer J, Di Virgilio F, Idzko M. Activation of human eosinophils via P2 receptors: novel findings and future perspectives. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79(1):7–15. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0505286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A, et al. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314(5806):1792–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parr CE, Sullivan DM, Paradiso AM, Lazarowski ER, Burch LH, Olsen JC, et al. Cloning and expression of a human P2U nucleotide receptor, a target for cystic fibrosis pharmacotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(8):3275–3279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erb L, Liao Z, Seye CI, Weisman GA. P2 receptors: intracellular signaling. Pflugers Arch. 2006;452(5):552–562. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erb L, Liu J, Ockerhausen J, Kong Q, Garrad RC, Griffin K, et al. An RGD sequence in the P2Y2 receptor interacts with αVβ3 integrins and is required for G(o)-mediated signal transduction. J Cell Biol. 2001;153(3):491–501. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao Z, Seye CI, Weisman GA, Erb L. The P2Y2 nucleotide receptor requires interaction with αv integrins to access and activate G12. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 9):1654–1662. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bagchi S, Liao Z, Gonzalez FA, Chorna NE, Seye CI, Weisman GA, et al. The P2Y2 nucleotide receptor interacts with αv integrins to activate Go and induce cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(47):39050–39057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Sayed FG, Camden JM, Woods LT, Khalafalla MG, Petris MJ, Erb L, et al. P2Y2 nucleotide receptor activation enhances the aggregation and self-organization of dispersed salivary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;307(1):C83–96. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00380.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siehler S. Regulation of RhoGEF proteins by G12/13-coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(1):41–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welch HC, Coadwell WJ, Ellson CD, Ferguson GJ, Andrews SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, et al. P-Rex1, a PtdIns(3,4,5)P3- and Gβγ-regulated guanine-nucleotide exchange factor for Rac. Cell. 2002;108(6):809–821. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown E. Integrin-associated protein (CD47): an unusual activator of G protein signaling. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(12):1499–1500. doi: 10.1172/JCI13315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J, Liao Z, Camden J, Griffin KD, Garrad RC, Santiago-Perez LI, et al. Src homology 3 binding sites in the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor interact with Src and regulate activities of Src, proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2, and growth factor receptors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(9):8212–8218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seye CI, Yu N, Gonzalez FA, Erb L, Weisman GA. The P2Y2 nucleotide receptor mediates vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression through interaction with VEGF receptor-2 (KDR/Flk-1) J Biol Chem. 2004;279(34):35679–35686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401799200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soltoff SP. Related adhesion focal tyrosine kinase and the epidermal growth factor receptor mediate the stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by the G-protein-coupled P2Y2 receptor. Phorbol ester or [Ca2+]i elevation can substitute for receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(36):23110–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu N, Erb L, Shivaji R, Weisman GA, Seye CI. Binding of the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor to filamin A regulates migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2008;102(5):581–588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.162271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woods LT, Jasmer KJ, Munoz Forti K, Shanbhag VC, Camden JM, Erb L, et al. P2Y2 receptors mediate nucleotide-induced EGFR phosphorylation and stimulate proliferation and tumorigenesis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Oral Oncol. 2020;109:104808. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ratchford AM, Baker OJ, Camden JM, Rikka S, Petris MJ, Seye CI, et al. P2Y2 nucleotide receptors mediate metalloprotease-dependent phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor and ErbB3 in human salivary gland cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(10):7545–7555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.078170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Camden JM, Schrader AM, Camden RE, Gonzalez FA, Erb L, Seye CI, et al. P2Y2 nucleotide receptors enhance α-secretase-dependent amyloid precursor protein processing. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(19):18696–18702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sahin U, Weskamp G, Kelly K, Zhou HM, Higashiyama S, Peschon J, et al. Distinct roles for ADAM10 and ADAM17 in ectodomain shedding of six EGFR ligands. J Cell Biol. 2004;164(5):769–779. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zbodakova O, Chalupsky K, Sarnova L, Kasparek P, Jirouskova M, Gregor M, et al. ADAM10 and ADAM17 regulate EGFR, c-Met and TNF RI signalling in liver regeneration and fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):11414. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90716-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muller T, Robaye B, Vieira RP, Ferrari D, Grimm M, Jakob T, et al. The purinergic receptor P2Y2 receptor mediates chemotaxis of dendritic cells and eosinophils in allergic lung inflammation. Allergy. 2010;65(12):1545–1553. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jasmer KJ, Woods LT, Forti KM, Martin AL, Camden JM, Colonna M, et al. P2Y2 receptor antagonism resolves sialadenitis and improves salivary flow in a Sjogren’s syndrome mouse model. Arch Oral Biol. 2021;124:105067. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2021.105067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrari D, Idzko M, Dichmann S, Purlis D, Virchow C, Norgauer J, et al. P2 purinergic receptors of human eosinophils: characterization and coupling to oxygen radical production. FEBS Lett. 2000;486(3):217–224. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)02306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin J, Dasari VR, Sistare FD, Kunapuli SP. Distribution of P2Y receptor subtypes on haematopoietic cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123(5):789–794. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang L, Jacobsen SE, Bengtsson A, Erlinge D. P2 receptor mRNA expression profiles in human lymphocytes, monocytes and CD34+ stem and progenitor cells. BMC Immunol. 2004;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gorini S, Callegari G, Romagnoli G, Mammi C, Mavilio D, Rosano G, et al. ATP secreted by endothelial cells blocks CX(3)CL 1-elicited natural killer cell chemotaxis and cytotoxicity via P2Y(1)(1) receptor activation. Blood. 2010;116(22):4492–4500. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-260828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woods LT, Camden JM, Khalafalla MG, Petris MJ, Erb L, Ambrus JL, Jr, et al. P2Y2 R deletion ameliorates sialadenitis in IL-14α-transgenic mice. Oral Dis. 2018;24(5):761–771. doi: 10.1111/odi.12823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harjunpaa H, Llort Asens M, Guenther C, Fagerholm SC. Cell adhesion molecules and their roles and regulation in the immune and tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1078. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baker OJ, Camden JM, Rome DE, Seye CI, Weisman GA. P2Y2 nucleotide receptor activation up-regulates vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 [corrected] expression and enhances lymphocyte adherence to a human submandibular gland cell line. Mol Immunol. 2008;45(1):65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]