Abstract

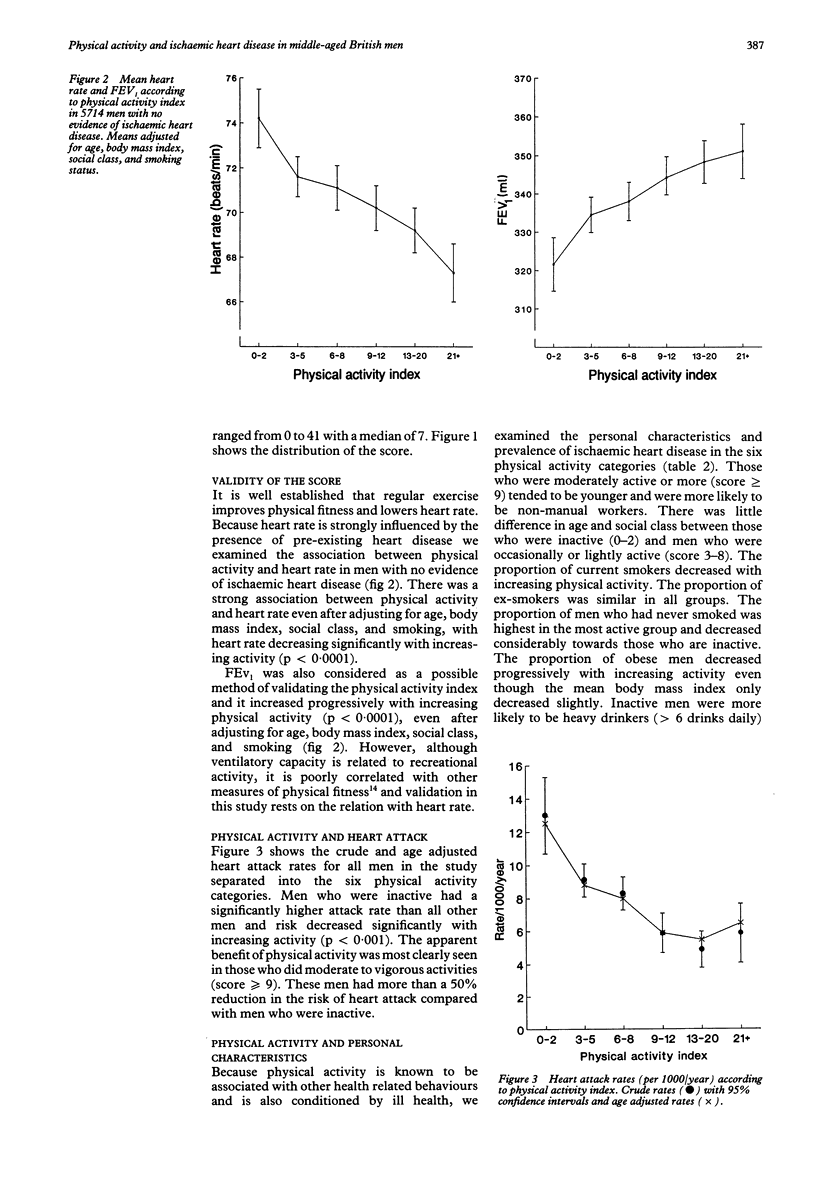

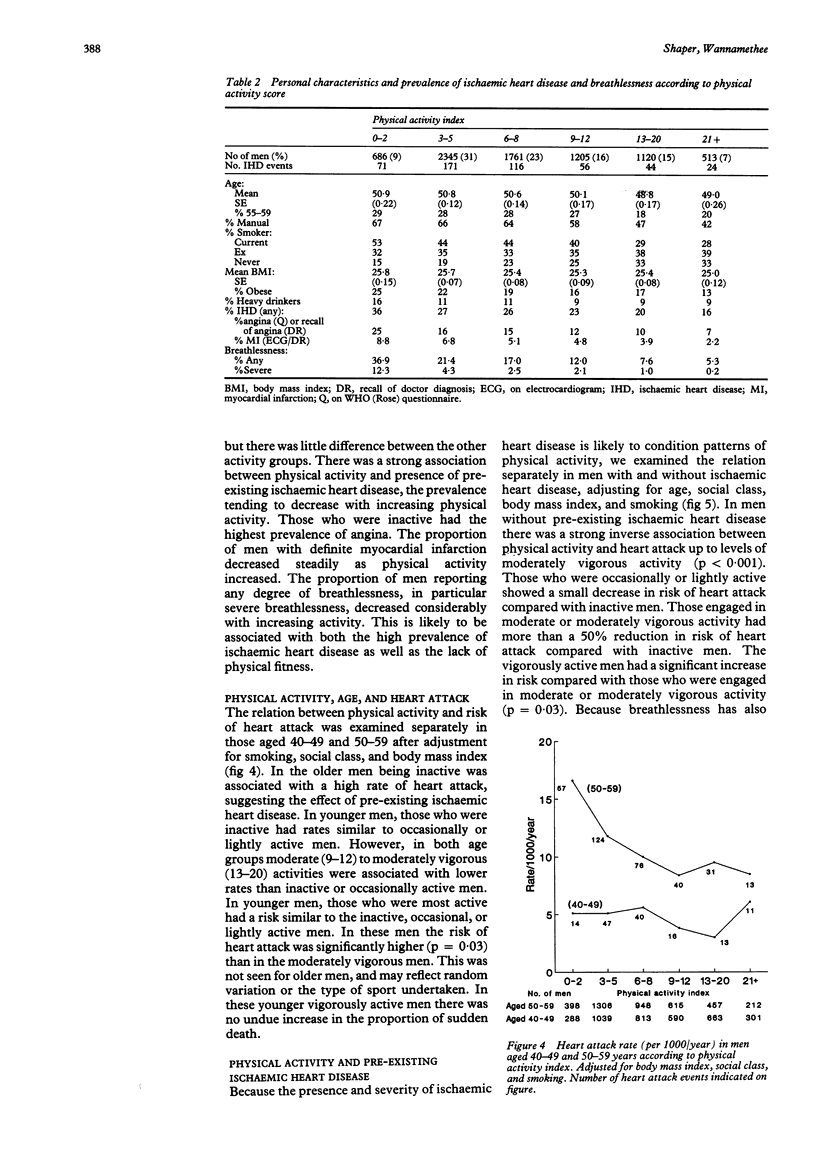

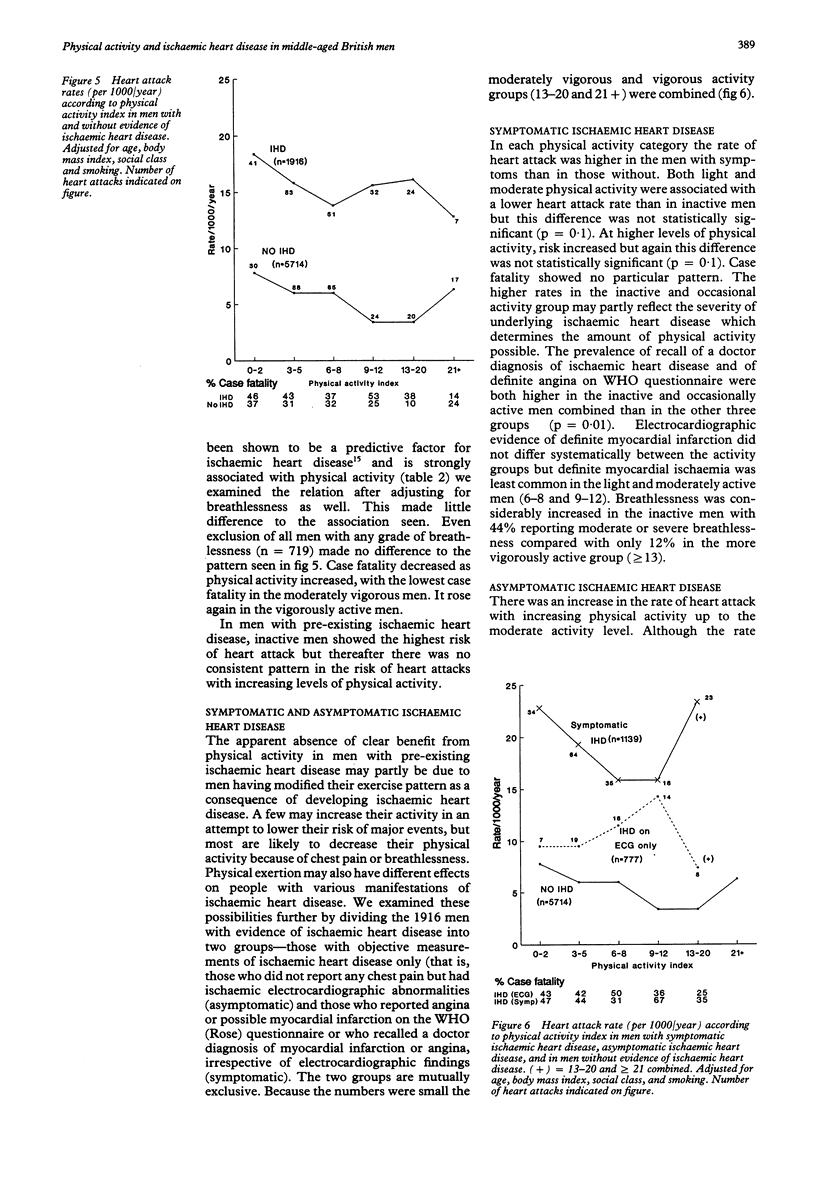

OBJECTIVE--To assess the relation between reported physical activity and the risk of heart attacks in middle aged British men. DESIGN--Prospective study of middle-aged men followed for a period of eight years (The British Regional Heart Study). SETTING--One general practice in each of 24 British towns. PARTICIPANTS--7735 men aged 40-59 years at initial examination. END POINT--Heart attacks (non-fatal and fatal). MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS--During the follow up period of eight years 488 men suffered at least one major heart attack. A physical activity score used was developed and validated against heart rate and lung function (FEV1) in men without evidence of ischaemic heart disease. Risk of heart attack decreased significantly with increasing physical activity; the groups reporting moderate and moderately vigorous activity experienced less than half the rate seen in inactive men. The benefits of physical activity were seen most consistently in men without preexisting ischaemic heart disease and up to levels of moderately vigorous activity. Vigorously active men had higher rates of heart attack than men with moderate or moderately vigorous activity. The relation between physical activity and the risk of heart attack seemed to be independent of other cardiovascular risk factors. Men with symptomatic ischaemic heart disease showed a reduction in the rate of heart attack at light or moderate levels of physical activity, beyond which the risk of heart attack increased. Men with asymptomatic ischaemic heart disease showed an increasing risk of heart attack with increasing levels of physical activity, but with a progressive decrease in case fatality. Overall, men who engaged in vigorous (sporting) activity of any frequency had significantly lower rates of heart attack than men who reported no sporting activity. However, when all men reporting regular sporting activity at least once a month were excluded from analysis, there remained a strong inverse relation between physical activity and the risk of heart attack in men without pre-existing ischaemic heart disease. CONCLUSION--This study suggests that the overall level of physical activity is an important independent protective factor in ischaemic heart disease and that vigorous (sporting) exercise, although beneficial in its own right, is not essential in order to obtain such an effect.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Berlin J. A., Colditz G. A. A meta-analysis of physical activity in the prevention of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1990 Oct;132(4):612–628. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair S. N., Kannel W. B., Kohl H. W., Goodyear N., Wilson P. W. Surrogate measures of physical activity and physical fitness. Evidence for sedentary traits of resting tachycardia, obesity, and low vital capacity. Am J Epidemiol. 1989 Jun;129(6):1145–1156. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair S. N., Kohl H. W., 3rd, Paffenbarger R. S., Jr, Clark D. G., Cooper K. H., Gibbons L. W. Physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy men and women. JAMA. 1989 Nov 3;262(17):2395–2401. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.17.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coats A. J., Adamopoulos S., Meyer T. E., Conway J., Sleight P. Effects of physical training in chronic heart failure. Lancet. 1990 Jan 13;335(8681):63–66. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90536-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D. G., Shaper A. G. Breathlessness, lung function and the risk of heart attack. Eur Heart J. 1988 Nov;9(11):1215–1222. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D. G., Shaper A. G., MacFarlane P. W. Using the WHO (Rose) angina questionnaire in cardiovascular epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1989 Sep;18(3):607–613. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekelund L. G., Haskell W. L., Johnson J. L., Whaley F. S., Criqui M. H., Sheps D. S. Physical fitness as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in asymptomatic North American men. The Lipid Research Clinics Mortality Follow-up Study. N Engl J Med. 1988 Nov 24;319(21):1379–1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811243192104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikssen J. Physical fitness and coronary heart disease morbidity and mortality. A prospective study in apparently healthy, middle aged men. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1986;711:189–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom A. R., Caspersen C. J., Taylor H. L., Jacobs D. R., Jr, Luepker R. V., Gomez-Marin O., Gillum R. F., Blackburn H. Leisure time physical activity and its relationship to coronary risk factors in a population-based sample. The Minnesota Heart Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1985 Apr;121(4):570–579. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Palmieri M. R., Costas R., Jr, Cruz-Vidal M., Sorlie P. D., Havlik R. J. Increased physical activity: a protective factor against heart attacks in Puerto Rico. Am J Cardiol. 1982 Oct;50(4):749–755. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(82)91229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel W. B., Kannel C., Paffenbarger R. S., Jr, Cupples L. A. Heart rate and cardiovascular mortality: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1987 Jun;113(6):1489–1494. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90666-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon A. S., Connett J., Jacobs D. R., Jr, Rauramaa R. Leisure-time physical activity levels and risk of coronary heart disease and death. The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. JAMA. 1987 Nov 6;258(17):2388–2395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. N., Chave S. P., Adam C., Sirey C., Epstein L., Sheehan D. J. Vigorous exercise in leisure-time and the incidence of coronary heart-disease. Lancet. 1973 Feb 17;1(7799):333–339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)90128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. N., Clayton D. G., Everitt M. G., Semmence A. M., Burgess E. H. Exercise in leisure time: coronary attack and death rates. Br Heart J. 1990 Jun;63(6):325–334. doi: 10.1136/hrt.63.6.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. N., Everitt M. G., Pollard R., Chave S. P., Semmence A. M. Vigorous exercise in leisure-time: protection against coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1980 Dec 6;2(8206):1207–1210. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92476-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paffenbarger R. S., Jr, Hyde R. T., Wing A. L., Hsieh C. C. Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni. N Engl J Med. 1986 Mar 6;314(10):605–613. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198603063141003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters R. K., Cady L. D., Jr, Bischoff D. P., Bernstein L., Pike M. C. Physical fitness and subsequent myocardial infarction in healthy workers. JAMA. 1983 Jun 10;249(22):3052–3056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen J. T., Slater J. S., Tuomilehto J., Rauramaa R. Leisure time and occupational physical activity: risk of death from ischemic heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1988 Jan;127(1):87–94. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper A. G., Cook D. G., Walker M., Macfarlane P. W. Prevalence of ischaemic heart disease in middle aged British men. Br Heart J. 1984 Jun;51(6):595–605. doi: 10.1136/hrt.51.6.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper A. G., Pocock S. J., Walker M., Cohen N. M., Wale C. J., Thomson A. G. British Regional Heart Study: cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged men in 24 towns. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981 Jul 18;283(6285):179–186. doi: 10.1136/bmj.283.6285.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siscovick D. S., Weiss N. S., Fletcher R. H., Lasky T. The incidence of primary cardiac arrest during vigorous exercise. N Engl J Med. 1984 Oct 4;311(14):874–877. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198410043111402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slattery M. L., Jacobs D. R., Jr, Nichaman M. Z. Leisure time physical activity and coronary heart disease death. The US Railroad Study. Circulation. 1989 Feb;79(2):304–311. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slattery M. L., Jacobs D. R., Jr Physical fitness and cardiovascular disease mortality. The US Railroad Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1988 Mar;127(3):571–580. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolski J., Kornitzer M., De Backer G., Dramaix M., Abramowicz M., Degre S., Denolin H. Protection against ischemic heart disease in the Belgian Physical Fitness Study: physical fitness rather than physical activity? Am J Epidemiol. 1987 Apr;125(4):601–610. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor H. L., Jacobs D. R., Jr, Schucker B., Knudsen J., Leon A. S., Debacker G. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31(12):741–755. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelle D. S., Shaper A. G., Whitehead T. P., Bullock D. G., Ashby D., Patel I. Blood lipids in middle-aged British men. Br Heart J. 1983 Mar;49(3):205–213. doi: 10.1136/hrt.49.3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson P. W., Paffenbarger R. S., Jr, Morris J. N., Havlik R. J. Assessment methods for physical activity and physical fitness in population studies: report of a NHLBI workshop. Am Heart J. 1986 Jun;111(6):1177–1192. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(86)90022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]