Abstract

Current combined challenges of rising food demand, climate change and farmland degradation exert enormous pressure on agricultural production. Worldwide soil salinization, in particular, necessitates the development of salt-tolerant crops. Soybean, being a globally important produce, has its genetic resources increasingly examined to facilitate crop improvement based on functional genomics. In response to the multifaceted physiological challenge that salt stress imposes, soybean has evolved an array of defences against salinity. These include maintaining cell homeostasis by ion transportation, osmoregulation, and restoring oxidative balance. Other adaptations include cell wall alterations, transcriptomic reprogramming, and efficient signal transduction for detecting and responding to salt stress. Here, we reviewed functionally verified genes that underly different salt tolerance mechanisms employed by soybean in the past two decades, and discussed the strategy in selecting salt tolerance genes for crop improvement. Future studies could adopt an integrated multi-omic approach in characterizing soybean salt tolerance adaptations and put our existing knowledge into practice via omic-assisted breeding and gene editing. This review serves as a guide and inspiration for crop developers in enhancing soybean tolerance against abiotic stresses, thereby fulfilling the role of science in solving real-life problems.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11032-023-01383-3.

Keywords: Soybean, Salt stress, Osmotic regulation, Ion homeostasis, Transcription regulation, Oxidative stress response

Introduction

The forecasted population growth in the 21st century will not only bring about increased demand in food production, but also accelerated urbanization. The current agricultural output will no longer be sufficient to support the increasing population, while urbanization will shrink the area of available farmland, worsening the situation. Although breeders and scientists are dedicated to increasing crop yield, the increased yield will not be sufficient to satisfy the demand. Exploring ways of utilizing salt-affected land for crop production appears to be an attractive option for increasing crop production (Shrivastava and Kumar 2015). To exacerbate the situation, agricultural irrigation is a major driving force of farmland salinization (Hassani et al. 2021). At the same time, changes in precipitation patterns and global warming due to climate change have been predicted to massively alter the distribution of salinized soil (Hassani et al. 2021). To better utilize saline soil and prevent yield loss due to farmland salinization, researchers are determined to gain a better understanding of the salt stress responses in crops to improve their salt tolerance through molecular breeding or genetic engineering.

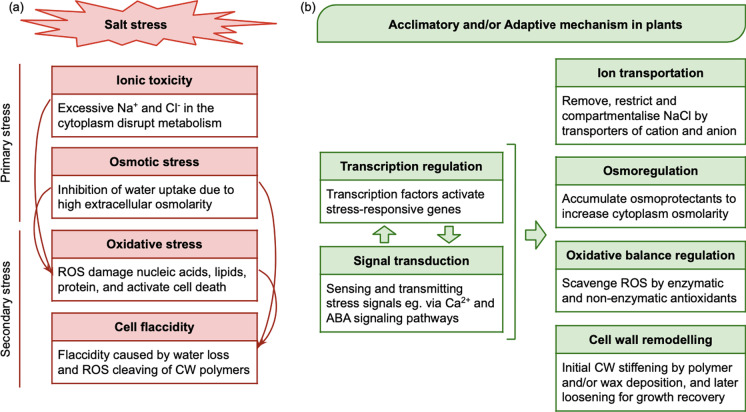

Salt stress is caused by the presence of excessive salt in the soil, which hampers the normal physiology of plants by inducing multiple stressors simultaneously (Fig. 1a). In turn, plants evolved acclimatory or adaptive responses to salinity (Fig. 1b). Salt stress includes the primary stresses of osmotic and ionic imbalance, and secondary stresses caused by reactive oxygen species (Ashraf 1994) and cell flaccidity (Yang and Guo 2018). The excessive salt content in the soil lowers the osmotic potential, and thus reduces the availability of water for uptake by the plant root. This causes physiological drought in the plant, where, despite the presence of water in the soil, the plant cannot uptake enough water through the roots to compensate for the water loss through transpiration. In some cases, the ionic salt is absorbed concurrently with the soil water, then transported and built up in the aerial parts of the plant. The accumulation of the toxic ionic salt causes ionic stress and disrupts cellular functions. The osmotic and ionic stresses then trigger the production of ROS, which damages macromolecules such as DNA and lipid, leading to cell death. Furthermore, net water loss causes cells to collapse from the reduced turgor pressure, which is acerbated by cell wall impairment caused by ROS. The ability to eliminate or tolerate these stress components is hence the key to salt tolerance. Plants have evolved mitigation towards each and different components of salt stress, which have been described in detail by many well written reviews (Deinlein et al. 2014; Hanin et al. 2016; Phang et al. 2008; van Zelm et al. 2020). Briefly, at the molecular level, ion transportation by specialised membrane proteins can restrict the negative impacts of excess salt ions. Water uptake is enhanced, and water loss is reduced by accumulating osmoprotectants to increase the osmolarity inside the cytoplasm. Antioxidants that scavenge and neutralise excessive ROS are produced to restore the oxidative balance. The loss of cell structural support is compensated by cell wall strengthening, and later loosening to enable growth and elongation. Meanwhile, all these responses are regulated and enabled by the interplay between transcription regulation and signal transduction.

Fig. 1.

Salt stress and molecular tolerance mechanisms in plants. Each mechanism and its genetic components in soybeans are discussed in detail in individual sections. Abbreviations: NaCl, sodium chloride; ROS, reactive oxygen species; CW, cell wall; ABA, abscisic acid

Soybean (Glycine max) is a relatively sustainable crop. It could acquire nitrogen through symbiotic nitrogen fixation in the nodules. The surplus of organic nitrogen can also replenish soil fertility. Therefore, compared to other major crops, soybean has a lower dependency on synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, of which production and utilization are energy-demanding and polluting to the environment. Soybean seeds contain roughly 40% protein and 20% oil, making it a good alternative to animal protein and lipid. With soybean being a primary producer, its consumption minimizes the energy and material loss during trophic transfer. Owing to its importance, soybean is also predicted to become a dominant crop in Africa in the future (Foyer et al. 2019).

Soybean is regarded as a moderately salt-tolerant crop (Ashraf 1994), and thus its production and acreage expansion are also hampered by soil salinization. However, unlike the model plant Arabidopsis, there is a lack of mutant collection for soybean. Screening soybean mutants for salt-tolerance genes is, hence, not a viable strategy. Twenty years ago, salt tolerance research in soybean was confined to physiological characterization and some low-resolution mapping. There were limited identification and characterization of functional genes. However, in the past twenty years, the advances in sequencing technologies have enabled the genome-wide identification and characterization of gene families with well-annotated reference genomes. Moreover, sequencing-based genotyping methods, such as genotyping-by-sequencing and genome resequencing, have generated high-density markers for precision mapping of genes related to salt tolerance. Transcriptomic studies have also been able to detect global gene expression changes under salt stress. We have previously reviewed the soybean salt tolerance mechanisms before the genomic age (Phang et al. 2008). In this review, we will explore the progress made in the identification and functional characterization of salt tolerance genes from soybean in the past twenty years (Fig. 2). From that, we will discuss the selection priority of various salt-tolerance mechanisms and suggest methods to incorporate our knowledge into field application.

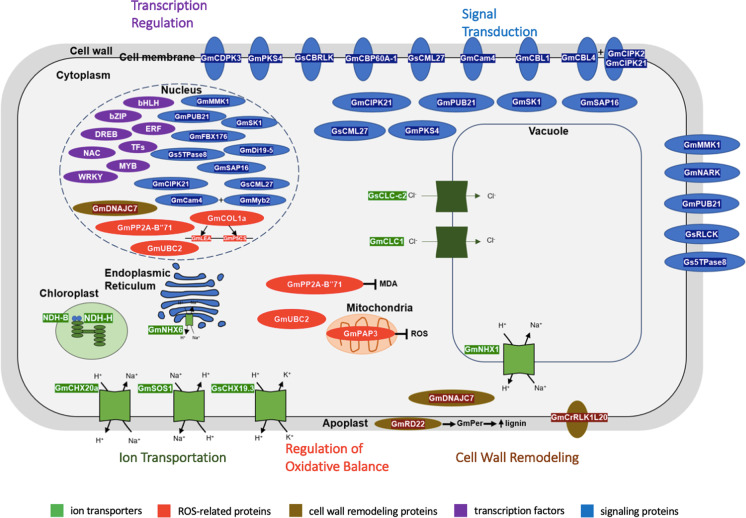

Fig. 2.

Overview of subcellular localization of soybean salt tolerance genes at cellular level. Light and dark green boxes indicate cation and anion transporters. respectively. CLC, chloride/proton exchanger or chloride channel; CHX, cation/H+ exchanger; NDH, subunit of NAD(P)H dehydrogenase complex; NHX, SOS (Salt Overly Sensitive), Na+/H+ exchanger. Genes involve in regulation of oxidative balance are colored in red. GmCOL1a, CONSTANS-LIKE 1a protein; GmLEA and GmP5CS are downstream target genes of GmCOL1a. GmPAP3, purple acid phosphatase 3; GmPP2A-B’71, B” subunit of phosphatase 2A; GmUCB2, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. Genes involve in cell wall remodeling are shown in brown. GmCrRLK1L20, Catharanthus roseus RLK1-like protein; GmDNAJC7, co-chaperone DNAJ protein; GmRD22, BURP-domain protein. Transcription factors are indicated in purple. bHLH, basic/helix-loop-helix protein; bZIP, basic leucine-zipper; DREB, dehydration responsive element-binding proteins; ERF, ethylene-responsive factors; MYB, MYB transcription factors; NAC, NAC (NAM, ATAF, CUC) transcription factors; WRKY, WRKY transcription factors; TFs, other transcription factors. Blue boxes indicate genes involve in signal transduction. GmCam4, calmodulin; GmCBL1, GmCBL4, calcineurin B-like protein; GmCBP60A-1, calmodulin-binding protein; GsCBRLK, calcium-dependent calmodulin-binding receptor-like kinase; GmCDPK3, calcium-dependent protein kinase; GmCIPK2, GmCIPK21, GmPKS4, calcineurin B-like protein interacting kinase; GmCML27, calmodulin-like protein. GmDi19-5, drought-induced protein; GmFBX176, F-box protein; GmMMK1, mitogen-activated kinase; GmNARK, nodule autoregulation receptor kinase; GmPUB21, U-box E3-ubiquitin ligase; GsRLCK, receptor-like cytoplasmic serine/threonine protein kinase; GmSAP16, stress associated protein; GmSK1, S-phase kinase-associated protein 1; Gs5PTase8, inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase

Ion transportation

Sodium (Na+) is not an essential nutrient for plants. However, Na+ can serve as a subpar substitute of potassium (K+), an essential macronutrient of plant, when K+ is scarce (Maathuis 2014). Meanwhile, chloride (Cl−) is a micronutrient of higher plants that is involved in vital functions such as photosynthesis, growth and development etc. (Geilfus 2018). Although sodium and chloride are beneficial to plants at low dosage, excessive amount of either one could be toxic. Therefore, to survive salt stress, soybean plant would need to remove excessive NaCl. Ion transportation is the major mechanism for soybean plants to maintain ion homeostasis. Different classes of ion transporters are localized in different subcellular membrane to alleviate salt stress through removing excessive NaCl from the cell, compartmentalization of NaCl into vacuole, and restricting the movement of NaCl from root to shoot (Table S1). Furthermore, it is reported that under salinity, H+-ATPase and H+-PPase located in tonoplast are more active, which provide the proton gradient to drive the active transport of ions from cytoplasm into vacuoles (Yu et al. 2005).

Cation transporters

In the past two decades, the major breakthrough for salt tolerance mechanisms in soybean is the identification of the cation/proton antiporter (CPA)-encoding gene, GmCHX1, which is the major determinant of the salt tolerance level of soybean (Guan et al. 2014; Qi et al. 2014; Qu et al. 2021). A salt tolerance-conferring major quantitative trait locus (QTL) has been mapped repeatedly to chromosome 3 of the soybean genome since 2004 (Ha et al. 2013; Hamwieh et al. 2011; Hamwieh and Xu 2008; Lee et al. 2004; Qi et al. 2014), but it was not until 2014 that the causal gene within this QTL was cloned.

GmCHX1 was first cloned through QTL mapping using a wild-cultivated soybean recombinant inbred population (Qi et al. 2014). It was later further confirmed by map-based cloning using other recombinant populations and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) with different nomenclatures, GmNcl/GmSALT3 (Guan et al. 2014; Patil et al. 2016). To prevent confusions in nomenclature, we will use the gene name reported in the first literature, GmCHX1 in the following sections. The protein sequence of the salt tolerance allele is largely conserved in salt-tolerant soybean varieties, while natural variations of this gene, either in the promoter region or in the coding region, have led to salt sensitivity (Guan et al. 2014; Qi et al. 2014). GmCHX1 is predominantly expressed in the tissue associated with the root vasculature to restrict the loading of Na+ into the shoot, protecting the shoot from salt damage (Guan et al. 2014; Qi et al. 2014; Qu et al. 2021). It is known that GmCHX1 is localized in the ER membrane, but the molecular mechanism of how this protein restricts the loading of Na+ into the shoot is still largely unknown. Interestingly, although GmCHX1 serves primarily as a CPA, transporting Na+ and K+ through the exchange of H+ in the root (Jia et al. 2021; Qu et al. 2021), a functional GmCHX1 is also needed for Cl− exclusion in the shoot in a root-independent manner (Qu et al. 2021).

Besides GmCHX1, the salt tolerance function of another CPA-encoding gene, GmCHX20a, which is located adjacent to GmCHX1 in the soybean genome, was also investigated. Although both GmCHX1 and GmCHX20a are homologs of AtCHX20 in Arabidopsis, the functions of GmCHX1 and GmCHX20a have diverged from those of AtCHX20 (Jia et al. 2021). First of all, the expression of GmCHX1 and GmCHX20a showed a negative correlation in the root upon salt treatment (Jia et al. 2021). That is, the expression of GmCHX1 was suppressed by the initial salt shock and then recovered after prolonged treatment while that of GmCHX20a was highly induced upon salt shock but was slowly reduced after prolonged treatment (Jia et al. 2021). When these genes were overexpressed in tobacco Bright-Yellow 2 (BY-2) cells, the plasma membrane-localized GmCHX20a enhanced the uptake of Na+ while GmCHX1 enhanced its exclusion (Jia et al. 2021). Consistent with this observation, the ectopic expression of GmCHX20a in transgenic Arabidopsis and soybean hairy root led to higher salt sensitivity. On the contrary, the transgenic BY-2 cells expressing GmCHX20a showed higher osmotic stress tolerance (Jia et al. 2021). One possible explanation is that GmCHX20a may function as an osmotic regulator by recruiting Na+ to combat osmotic stress during the early phase of salt stress before GmCHX1 kicks in. A later study demonstrated that the level of histone 3 lysine 9 acetylation (H3K9ac) at the promoter of GmCHX20a was decreased upon mild salt stress priming treatment, implying that switching off GmCHX20a by salt stress priming may contribute to the enhanced salt tolerance in subsequent salt stresses (Yung et al. 2022).

Indeed, another major clade in the CPA family is the Na+/H+ exchanger (NHX). There are 9–10 NHX-encoding genes in the soybean genome (Chen et al. 2015b; Joshi et al. 2021). For example, GmSOS1 is the homolog of the well-characterized AtSOS1/AtNHX7 (Arabidopsis Salt Overly Sensitive 1/Arabidopsis Na+/H+ exchanger 7), which has played crucial roles in salt tolerance in Arabidopsis (Qiu et al. 2002). However, unlike AtSOS1, which has two copies in the Arabidopsis genome, GmSOS1 is a single-copy gene in the soybean genome (Zhang et al. 2022c). The expression of GmSOS1 is salt-responsive and in a dosage-dependent manner in the root (Zhang et al. 2022c). The ectopic overexpression of GmSOS1 can complement the salt overly sensitive phenotype of atsos1 mutant, suggesting that the function of the SOS1 homologs is essentially conserved (Nie et al. 2015). A loss-of-function mutation of GmSOS1 in Williams 82 and Jack backgrounds increased the sensitivity of the plant toward salt stress in terms of the survivability in 160 mM NaCl treatment (Zhang et al. 2022c). It was observed that the gmsos1 mutants had lower net Na+ fluxes but higher K+ fluxes in the root meristem zone. The impaired ion fluxes significantly increased and decreased the Na+/K+ ratio in the root and leaf, respectively, of the mutants (Zhang et al. 2022c). The imbalance in monovalent ions may be the reason for the salt sensitivity. This imbalance of ions also subsequently perturbed the expression of ion transporter-encoding genes such as KEA2, GmCHX20b, NCX1, and CIPK9 (Zhang et al. 2022c).

GmNHX1 is highly induced by NaCl or polyethylene glycol (PEG) treatment. It is localized in the tonoplast membrane and responsible for the compartmentalization of Na+ into vacuoles under salt stress (Li et al. 2006). The ectopic expression of GmNHX1 enhanced the salt tolerance of BY-2 cells (Li et al. 2006), Arabidopsis (Sun et al. 2019a), soybean hairy root (Wang et al. 2011a), and Lotus corniculatus L. (Sun et al. 2006). GmNHX5 was responsive to NaCl treatment in the salt-tolerant cultivar Jidou-7, but not in the salt-sensitive cultivar Mustang (Sun et al. 2021). The overexpression of GmNHX5 in transgenic soybean alleviated the salt stress symptoms and significantly reduced Na+ accumulation while enhancing K+ accumulation in the leaf and root (Sun et al. 2021). Nevertheless, it is still unclear how GmNHX5 alters the accumulation of these ions.

GsCHX19.3 (Jia et al. 2017) and GmNHX6 are two CPA-encoding genes that are responsive to salt-alkaline stress (Jin et al. 2022a). Although GsCHX19.3 was localized to the plasma membrane while GmNHX6 was localized to the Golgi, they both facilitated the uptake of K+ and reduced Na+ accumulation under salt-alkaline stress in transgenic Arabidopsis to maintain a low Na+/K+ ratio (Jia et al. 2017), which may be responsible for the higher salt tolerance of the transgenic Arabidopsis (Jia et al. 2017; Jin et al. 2022a).

The high-affinity K+ transporter (HKT) family is another important class of ion transporters conferring salt tolerance in plants (Singh and Lone 2022). There are six HKT-encoding genes identified in the soybean genome, namely GmHKT1;1-GmHKT1;6 (Chen et al. 2014). Thus far, only the function of GmHKT1;1 (GmHKT1) and GmHKT1;4 have been characterized. The ectopic expression of either GmHKT1;1 or GmHKT1;4 was sufficient to confer salt tolerance in transgenic tobacco plants (Chen et al. 2014, 2011). Like other salt tolerance-conferring ion transporters, both of these HKTs reduced Na+ and improved K+ accumulation in the transgenic plants upon salt treatment when compared to the wild type (Chen et al. 2014, 2011).

Through QTL mapping using a recombinant inbred population of Kefeng No. 1 and Nannong 1138–2, QTLs related to salt tolerance at the germination stage, in terms of imbibition rate, germination index, germination potential and germination rate, were mapped to chromosome 8 in the soybean genome (Zhang et al. 2019a). Seventeen single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) significantly associated with the salt tolerance of 211 soybean accessions at the germination stage were also identified in the same regions (Zhang et al. 2019a). Amongst the polymorphic genes between the Kefeng No. 1 and Nannong 1138–2 within the region, only GmCDF1 (soybean cation diffusion factor 1; Glyma.08g102000) was induced by salt stress and was highly differentially expressed between the two parental lines under salt stress (Zhang et al. 2019a). In general, a higher expression of GmCDF1 is associated with a lower salt tolerance, as illustrated by the expression study on soybean accessions with different salt tolerance, and by transgenic composite soybean plants with roots either overexpressing or underexpressing GmCDF1 (Zhang et al. 2019a). Although the expression of GmCDF1 was positively associated with the accumulation of Na+ in the root and affected the expression of other salt tolerance-related genes, the direct link between GmCDF1 and salt sensitivity is still unknown.

Some ion transporters involved in salt tolerance may not be directly involved in NaCl transportation. One example is the calcium/proton exchangers (CAXs). A stress-responsive soybean transcript, GmCAX1, was found to be differentially expressed upon PEG, CaCl2, NaCl, ABA and LiCl treatments. Overexpression of GmCAX1 could alleviate the salt stress symptoms of transgenic Arabidopsis (Luo et al. 2005), probably through increasing the accumulation of Ca2+ and reducing the accumulation of monovalent ions (Na+, K+, and Li+, if present) (Luo et al. 2005). Whether GmCAX1 alters the accumulation of monovalent ions through direct transportation or regulates ion transportation indirectly through calcium signaling is still unknown.

Auto-inhibited Ca2+-ATPases (Rodrigues et al.) regulate the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration that contributes to salt tolerance. A NaHCO3- and NaCl-responsive gene, GsACA1, was cloned from wild soybean (Glycine soja) (Sun et al. 2016). Transgenic alfalfa overexpressing GsACA1 showed better salt tolerance and higher chlorophyll content than the wild type plants upon salt treatment. Moreover, compared to the wild type, transgenic plants showed lower membrane permeability and a lower malondialdehyde (MDA) content but a higher content of proline, which is both an osmolyte and ROS scavenger (Sun et al. 2016). GsACA1 probably regulates salt tolerance through calcium signaling, but that requires further investigation.

Anion transporters

The chloride channel protein (CLCs) family is one of the crucial classes of chloride transporters involved in salt tolerance in plants (Wu and Li 2019). There are eight CLC-encoding genes in the soybean genome (Wei et al. 2019), while only two of them have been demonstrated to be involved in soybean salt tolerance. It was found that GmCLC1, CLC-b1, CLC-b2, CLC-c1, and CLC-c2 were significantly induced by salt treatment in both the salt-sensitive cultivar N23674 and the salt-tolerant wild soybean BB52 (Wei et al. 2019). As the only member containing non-synonymous SNP between N23674 and BB52, GsCLC-c2 from the wild soybean BB52 was able to confer salt tolerance in composite soybean plants with hairy roots overexpressing GsCLC-c2 (Wei et al. 2019). The tonoplast-localized GsCLC-c2 could compartmentalize NaCl in the root and promote the accumulation of NO3− and K+ in the shoot to counteract the damages caused by salt treatment (Wei et al. 2019). An electrophysiology experiment using oocytes injected with GsCLC-c2 cRNA demonstrated that GsCLC-c2 could function as a pH-independent Cl− channel with a higher affinity towards Cl− and NO3− (Wei et al. 2019).

GmCLC1 is another CLC-encoding gene. Although its expression in soybean was highly induced by both NaCl and PEG, its ectopic expression in BY-2 cells could only confer tolerance to salt but not PEG (Li et al. 2006). Lucigenin staining of isolated vacuoles demonstrated that GmCLC1 could compartmentalize Cl− into the vacuoles upon NaCl treatment (Li et al. 2006). An electrophysiology study as well as sequence homology implied that GmCLC1 is a Cl−/H+ antiporter (Wong et al. 2013). The ectopic expression of GmCLC1 could also confer salt tolerance to transgenic Arabidopsis, transgenic soybean hairy roots and transgenic hairy root composite plants (Wei et al. 2016). An in planta experiment suggested that GmCLC1 was able to compartmentalized Cl− in the root to prevent the accumulation of Cl− in the shoot (Wei et al. 2016).

Other transporters

Besides ion transporters, other kinds of transporters were shown to be involved in salt stress responses. Plasma membrane intrinsic proteins (PIPs) govern the water transport across the plasma membrane (Chaumont and Tyerman 2014). The expression of GmPIP1;6 was initially suppressed within the first few hours of salt treatment and then the gene was induced in the following days (Zhou et al. 2014), probably due to its differential functions during the osmotic stress and ionic stress phases. Transgenic soybean plants overexpressing GmPIP1;6 showed better salt tolerance than the wild type in terms of growth, photosynthetic performance, and higher root hydraulic conductance under salt treatment conditions (Zhou et al. 2014). Furthermore, the transgenic plants also bore lower Na+ contents than the wild type (Zhou et al. 2014). Although it is still unsure how GmPIP1;6 confers salt tolerance, the major hypothesis suggests that GmPIP1;6 serves as a filter for the soil water, by allowing water to enter the cell while blocking the uptake of NaCl to maintain the water status of the plant.

Apart from managing material transfer or serving as components of signal transduction pathways, transporters are also essential for maintaining the energy status of the plant under salt stress. Active ion transportation is an energy-intensive process. A collapse of energy production mechanism such as photosynthesis upon salt stress is usually used as an indicator of salt sensitivity. ndhB and ndhH are genes encoding the subunits of NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (NDH), which drives the cyclic electron flow for ATP production (He et al. 2015). The expression of both ndhB and ndhH were induced by salt treatment at both the transcript and the protein levels. Furthermore, the expressions of both genes were higher in both the salt-tolerant soybean S111-9 and the salt-sensitive Melrose in both normal and salt-treated conditions. Interestingly, upon salt treatment, Na+ was mainly compartmentalized in the vacuole of S111-9 and the chloroplast of Melrose, which could be the cause of the difference in salt sensitivity (He et al. 2015). Although direct evidence is lacking, with these observations, it is proposed that the active NDH-dependent cyclic electron flow might be important for providing ATP for active Na+ sequestration into the vacuole to enhance the salt tolerance of the plant (He et al. 2015).

Osmoregulation

Upon the early stage of salt stress, due to the sudden presence of high solute concentration in the soil, the water potential around the root is lowered, and water is thus unavailable to the plant. The water loss through transpiration supersedes the water uptake through the root, leading to water deficit. It is reflected in drooping leaves within the first hour of salt treatment due to the loss of turgor pressure in the cells. In general, the soybean plant is able to cope with this osmotic stress within a few hours through different mechanisms.

Accumulation of osmoprotectants in the cell is one way to balance the osmolarity between the inside and outside of the cell. As mentioned in the previous section, pumping Na+ into the cells as a readily available osmolyte through active transportation could be a quick way to reduce the cellular water potential, though this strategy will likely result in subsequent ion toxicity (Jia et al. 2021). In addition to the ionic salt, the plant also produces and accumulates compactible metabolites such as onium compounds, polyols/sugars, amino acids, and alkaloids (Phang et al. 2008). Since this mechanism has been intensively discussed (Hasegawa et al. 2000; Phang et al. 2008), it will not be covered in this review.

Osmoregulation by late embryogenesis abundant proteins

Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins have been investigated broadly with respect to salt tolerance. The expressions of LEA-encoding genes were highly induced under different stress conditions such as drought, heat, cold and salt stresses (Bhardwaj et al. 2013; Hasegawa et al. 2000). The LEA proteins might function by (i) participating as antioxidant to safeguard against ROS (Sobhanian et al.); (ii) stabilizing the plasma membrane and proteins; (iii) filling the space and maintain the shape of cells upon dehydration (Bhardwaj et al. 2013; Tunnacliffe and Wise 2007). Given that LEA proteins are in general highly hydrophilic, the accumulation of LEA proteins in cells upon desiccation is proposed to be an important mechanism for osmoregulation. LEA proteins can be divided into four groups according to their structures, with each group serving a different function (Bhardwaj et al. 2013; Tunnacliffe and Wise 2007; Wise and Tunnacliffe 2004).

The functions of a few soybean LEA proteins, such as PM11 and Em belonging to group I LEAs, have been studied (Lan et al. 2005; Cai et al. 2006). Transgenic Escherichia coli expressing PM11 underwent a short lag phase when growing in a medium containing 800 mM NaCl when compared to the vector-only control (Lan et al. 2005). Apart from improving the salt tolerance of transgenic E. coli, Em could also confer salt tolerance in transgenic tobacco plants (Cai et al. 2006). Besides, group II LEA proteins such as GmLEA2-1 can also enhance salt tolerance. Overexpressing GmLEA2-1 in Arabidopsis showed improved tolerance under mannitol and NaCl treatment, in which the expression might be regulated by DREB-, DBF-, CBF-, MYC- or MYB-like transcription factors (Wang et al. 2018b).

The functions of PM30 and PM2, belonging to group III LEA proteins, have also been studied using transgenic E. coli. Similar to PM11, PM30 was able to confer tolerance to transgenic E. coli treated with 800 mM NaCl (Lan et al. 2005). Transgenic E. coli expressing PM2 did not gain any advantage over the control under 1100 mM sorbitol treatment, but it showed improvement in salt tolerance when treated with 500 mM NaCl and 500 mM KCl (Liu and Zheng 2005). Furthermore, the expression of the 22-mer repeating region of PM2 in E. coli demonstrated a similar protective effect as the full-length PM2, suggesting that the 22-mer repeating region is responsible for the tolerance (Liu and Zheng 2005).

Regulation of oxidative balance

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are by-products of redox reactions in aerobic respiration and photosynthesis (Dixon et al. 2010). Integral to plant metabolic pathways, ROS exhibit dual effects depending on their cellular concentrations (Das and Roychoudhury 2014). At low levels, they act as signaling molecules or substrates for metabolism (Czarnocka and Karpinski 2018), whereas at high concentrations, they cause oxidative damage to nucleic acids, proteins, lipids and pigments (Gill and Tuteja 2010). Salinity induces secondary oxidative stress by perturbing ROS homeostasis, by increasing ROS production while slowing their removal (Chawla et al. 2013). The overaccumulation of ROS and their downstream products cause damage to biomolecules and cell tissue, and eventually lead to cell death (Czarnocka and Karpinski 2018; Gill and Tuteja 2010). Therefore, key adaptations in salinity tolerance usually entail enhanced ROS scavenging to restore oxidative balance at the transcription, translation and post-translational modification levels (Lv et al. 2014; Matsuura et al. 2010; Schmidt et al. 2013; Yu et al. 2010). It is thus critical for crop improvement research to investigate the genes responsible for ROS scavenging during salt stress.

To restore oxidative balance under salt stress, soybean employs both antioxidant enzymes and secondary metabolites (Das and Roychoudhury 2014), of which synthesis is activated by high concentrations of ROS and malondialdehyde (MDA), a toxic electrophile produced from the peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acid (Dixon et al. 2010). Enzymatic antioxidants catalyze direct ROS scavenging or reactions that replenish ROS decomposition substrates (Das and Roychoudhury 2014), while non-enzymatic antioxidants serve as scavenging substrates or direct scavengers (Dogan 2011). These two groups complement each other in ROS elimination. Thus far, a number of genes underpinning the production of antioxidants and their ROS scavenging pathways in soybean have been discovered and functionally verified (Table S2).

In general, superoxide dismutase (SOD) catalyzes the conversion of superoxide radicals into less reactive hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and oxygen molecules. Hydrogen peroxide is normally detoxified by catalase (CAT) (Rodrigues et al.), peroxidase (POD) or ascorbate peroxidase (APX) coupled with the ascorbate–glutathione cycle (Das and Roychoudhury 2014). A class III peroxidase-encoding gene, GsPRX9, was cloned from a salt-tolerant wild soybean (Jin et al. 2019). The expression of GsPRX9 was significantly induced by salt stress and the induction was more prominent in salt-tolerant wild soybeans, LY01-10 and LY16-08, than in the salt-sensitive cultivated soybean, Tianlong1, and the salt-sensitive wild soybean, LY01-06 (Jin et al. 2019). Composite soybean plants with roots overexpressing GsPRX9 apparently grew better than those transformed with empty vector, with higher SOD and POD activities and glutathione concentration (Jin et al. 2019). GsPRX9 overexpression also led to the upregulation of seven genes involved in the phenylpropanoid pathway (Jin et al. 2019), which is the major pathway producing secondary metabolites with antioxidant activities.

Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) are another class of potent antioxidants that catalyze the conjugation of the nucleophilic glutathione (GSH) to lipid hydroperoxides, hence preventing the downstream generation of the toxic MDA (Sharma et al. 2004). Under acute salt stress at 200 mM NaCl, GsGST-overexpression in tobacco led to a sixfold increase in GST activities and a significantly higher survivorship and root elongation compared to the wild type (Ji et al. 2010). Meanwhile, under salt treatment, GmGSTL1-overexpression in tobacco BY-2 cells and Arabidopsis reduced ROS accumulation and leaf chlorosis (Chan and Lam 2014), which is a typical symptom of ROS toxicity (Lim et al. 2007). Chan and Lam (2014) elucidated the anti-oxidation mechanism of soybean GST through its conjugation with the secondary metabolites, quercetin and kaempferol, and demonstrated the interactions between quercetin and GST via exogenous applications.

ROS detoxification also entails MDA scavenging by aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDHs), which catalyze the conversion of aldehydes into carboxylic acids (Singh et al. 2013). Under salinity stress, the ectopic expression in Arabidopsis and tobacco of Glycine max turgor-responsive 55 kDa protein (GmTP55), which encodes an antiquitin-like ALDH, resulted in higher germination efficiency and seedling development than the wild-type plants (Rodrigues et al. 2006). Notably, transgenic Arabidopsis under 100 mM NaCl retained the same germination rate as in unstressed condition (Rodrigues et al. 2006). The elevated salt tolerance was achieved by a higher anti-oxidation efficiency as evidenced by GmTP55-overexpressing transgenic plants exhibiting lower MDA levels and less severe oxidative stress symptoms under peroxide and paraquat treatments than wild-type plants (Rodrigues et al. 2006).

Alternative salt stress response pathways involving purple acid phosphatase 3 have also been uncovered (Liao et al. 2003). GmPAP3 is localized in mitochondria, a primary site of ROS generation (Li et al. 2008). Under salt and oxidative stress treatments, the overexpression of GmPAP3 in tobacco BY-2 cells resulted in reduced ROS levels and increased ascorbic acid-like antioxidation pathway activities, while GmPAP3-overexpressing Arabidopsis experienced reduced lipid peroxidation (Li et al. 2008). The ectopic expression of GmPAP3 in rice also yielded increased SOD, POD and CAT activities, a higher proline content, and a reduced MDA content under salt treatment compared to wild type (Deng et al. 2014). Since the ROS-scavenging effects from GmPAP3 overexpression were diminished when an ion chelator was present, it is possible that the redox reactions of GmPAP3 play a role in ROS scavenging (Li et al. 2008). However, whether GmPAP3 acts on ROS directly or through interfering Fenton or Heiber-Weiss reactions is still inconclusive and awaits further investigations.

Increasing the generation of secondary metabolites involved in ROS catabolism can also contribute to the restoration of oxidative balance in soybean. L-ascorbic acid (AA), a prominent antioxidant in photosynthetic eukaryotes, reacts with peroxides to form the nontoxic docosahexaenoic acid (Wheeler et al. 2015). AA synthesis, catalyzed by GDP-D-mannose pyrophosphorylase (GMP), hence acts as a universal defence against oxidative stress (Wheeler et al. 2015). Indeed, under salt stress, overexpressing GmGMP1 in transgenic Arabidopsis conferred higher salt tolerance via significantly elevated AA levels and reduced levels of superoxide radicals and lipid peroxidation (Xue et al. 2018). Other important non-enzymatic antioxidants in soybean include flavonoids and proline. Flavonoids, a class of polyphenolic compounds, can directly scavenge peroxides, singlet oxygen and hydroxyl radicals (Brunetti et al. 2013). Similarly, proline, which also acts as an osmolyte, scavenges singlet oxygen and hydroxyl radicals, and prevents damages from lipid peroxidation (Dogan 2011). In transgenic Arabidopsis, GmMYB12 overexpression improved salt stress tolerance during seed germination, root development, and in the vegetative stage by increasing flavonoid and proline productions and upregulating genes involved in their biosynthesis, alongside increased SOD and POD activities (Wang et al. 2019b).

Some gene products may not act directly on ROS but regulate the downstream expressions of genes that mitigate the salt-induced oxidative stress. Xiong et al. (2022) examined the interactions between ROS, salt tolerance and protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), an enzyme family that is known to modulate oxidative stress in plants. Specifically, PP2A-B”71 was shown to mediate the stress-induced abscisic acid (ABA) signaling (Yang et al. 2020a), and its expression was responsive to salt stress (Xiong et al. 2022). Under salt treatment, GmPP2A-B”71-overexpressing soybean hairy roots had increased levels of chlorophyll, proline, CAT and POD, and lower MDA content, while GmPP2A-B”71-RNA-interference plants exhibited the opposite phenotype (Xiong et al. 2022). Crucially, GmPP2A-B”71 overexpression markedly upregulated genes responsible for the synthesis of CATs (GmCAT1 and GmCAT2) and POD (GmPOD1), and two genes with putative roles in stress-responsive antioxidation (GmLEA15 and GmERF115) (Xiong et al. 2022). Similarly, CONSTANS-LIKE 1a (GmCOL1a), a flowering repressor gene in soybean, was found to participate in oxidative stress alleviation by promoting the accumulation of stress-responsive proteins under salinity treatment (Xu et al. 2022). GmCOL1a proteins, of which expressions are highly induced by NaCl, are localized in the nucleus and promote the transcriptional activation of the stress-tolerance genes, GmLEA and GmP5CS, by binding to their promoters (Xu et al. 2022). Compared to the knockout mutants and wild type, GmCOL1a-overexpressing and GmP5CS-overexpressing soybean hairy roots had much more effective antioxidation under salt treatment via reduced ROS levels, and significantly elevated enzymatic antioxidant activities and proline concentrations (Xu et al. 2022). Both studies attest to the importance of characterizing the regulation of downstream salt-tolerance genes by the target genes under salt stress.

Besides directly participating in the restoration of oxidative balance, signal transduction (which will be discussed in detail in a later section) is crucial for plants to detect salt stress and acclimatize accordingly. Genes encoding substrate or receptor proteins involved in signal transduction can mediate salinity stress responses including ROS scavenging. The ectopic expression experiments of such soybean genes have implied their potential roles in salt-induced oxidative stress responses. The phytohormone, abscisic acid (ABA), is an important messenger in stress signaling pathways in plants. In both maize and wheat, exogenous ABA applications at low doses increased the activities of SOD, CAT, APX and glutathione reductase (Agarwal et al. 2005; Jiang and Zhang 2001). By increasing ABA sensitivity, a lower threshold is required to activate stress responses, thereby allowing plants to mitigate salinity stress more quickly and preventing the overaccumulation of intracellular ABA, which can be toxic at high concentrations (Agarwal et al. 2005; Jiang and Zhang 2001). GmSAP16, which encodes stress-associated proteins (SAPs) of the zinc-finger protein family, increased ABA sensitivity and proline level, and reduced MDA level when overexpressed in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots (Zhang et al. 2019b). Similarly, in Arabidopsis under salt treatment, the ectopic expression of GmST1, of which function has yet to be characterized, increased ABA sensitivity and reduced peroxide level (Ren et al. 2016). The expressions of lectin receptor protein kinases (LecRLK), another important group of receptors to external stress signals in plants, were induced in wild soybean roots under salt treatment (Zhang et al. 2022d). Under salt stress, GmLecRlk-overexpressing soybean hairy roots had increased proline content and CAT activities, and reduced peroxide and MDA levels compared to the wild-type control (Zhang et al. 2022d). The exact functional mechanism of GmLecRlk in soybean oxidative stress reduction is unknown, but the expression patterns of its homologs in Arabidopsis, rice and other legumes under salinity stress suggested its involvement in mediating the ABA signaling pathway (Joshi et al. 2010; Li et al. 2014; Sun et al. 2013b). The exact physiological mechanisms of these genes in soybean oxidative stress reduction are not as well characterized as their roles in improving ion homeostasis or signal transduction. As a result, their roles in restoring oxidative balance are only implicated. The improved ROS scavenging due to the expressions of these genes is likely due to their downstream regulation of the antioxidation regulatory network, which awaits verification by future research.

Besides salinity, secondary oxidative stress and the subsequent antioxidation metabolism in plants are also inducible by other biotic and abiotic stresses (Cheng et al. 2015; Li et al. 2021a; Mira et al. 2021). In particular, multiple soybean genes responsible for oxidative balance restoration have been functionally verified with drought stress, an agricultural challenge that often occurs concurrently with salinity (Li et al. 2018a, 2013; Wang et al. 2019b). Furthermore, genome-wide identification has been applied to characterize the soybean gene families associated with the enzymatic antioxidants, SOD and glutathione peroxidase (Aleem et al. 2022), while proteomic and metabolomic analyses have uncovered indirect pathways that can improve soybean antioxidation (Pi et al. 2016). Future studies could verify the functions of these genes with salt treatment, thereby expanding the genetic avenues available for improving oxidation–reduction responses in soybean under salinity stress.

Cell wall remodeling

In plants, cell wall (CW) provides structural support by maintaining cell stiffness (Houston et al. 2016), and the apoplast serves as an important site for reactions and signal transduction (Farvardin et al. 2020). The physical and biochemical properties of CW render it indispensable to plant survival under abiotic stress (Farvardin et al. 2020; Le Gall et al. 2015; Tenhaken 2015). Salinity impairs CW functioning and arrests plant growth by inducing osmotic imbalance that reduces cell turgidity (Liu et al. 2021a), and by causing secondary oxidative stress, where excessive ROS results in cell wall loosening (Gigli-Bisceglia et al. 2020). There is increasing evidence suggesting CW remodeling to be a critical adaptation to salt stress (Liu et al. 2021a). To survive under high salinity, plants constantly modulate CW structure and composition to optimize stress signal detection, CW integrity repair, and subsequent loosening to allow for growth under sustained stress (Houston et al. 2016; Le Gall et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2021a; Tenhaken 2015). Exploring the genes underlying the adaptive remodeling of soybean CW under salt stress offers insights into improving crop tolerance against salinity.

CW is a dynamic and complex matrix consisting of polysaccharides, proteins, and other compounds that help maintain or modulate CW functions. The cellulose microfibril scaffold is interconnected by hemicellulose and pectin (Lampugnani et al. 2018; Loix et al. 2017; Somerville et al. 2004). The depolymerization of these polysaccharides via enzymatic or ROS cleavage, their strengthening by increased cross-linkages, or changes in their biosynthetic rates, all combine to modulate CW plasticity and tensile strength as plants respond to abiotic stress (Houston et al. 2016; Le Gall et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2021a; Tenhaken 2015). Cell wall proteins, which can either be embedded in the CW or in soluble forms in the apoplast, include enzymes that catalyze CW component biosynthesis and modifications, as well as those involved in stress signal reception and transduction (Jamet et al. 2006; Tenhaken 2015). Mediating the abundance, composition and distribution of aforementioned CW components are integral to plant survival and development under abiotic stress.

The immediate challenge faced by plants under high salinity is osmotic stress, which causes the loss of cell turgor (Liu et al. 2021a). Furthermore, the ROS generated as the secondary stress response cleave polysaccharide polymer linkages, hence lowering CW tensile strength and aggravating the water loss-induced flaccidity (Tenhaken 2015). Therefore, the first line of CW defense involves increasing mechanical strength by polymer biosynthesis and deposition. In soybean, a co-chaperone DNAJ protein, GmDNAJC7, was found to upregulate and co-express with genes involved in cellulose biosynthesis, where under salt treatment, GmDNAJC7-overexpressing Arabidopsis had a higher germination rate, a higher cotyledon greening rate and greater root length compared to wild type (WT) (Jin et al. 2022b). The production of lignin, a phenolic polysaccharide of which deposition at secondary CW confers tensile strength, is often increased to stiffen CW amidst stresses (Cesarino 2019). GmRD22 encodes a BURP-domain protein localized in the apoplast that interacts with a cell wall peroxidase to increase CW lignification (Wang et al. 2012). Under salt treatment, its overexpression in tobacco BY-2 cells, Arabidopsis and rice resulted in higher survivorship while reducing the negative effects of NaCl on Arabidopsis root elongation (Wang et al. 2012). In both Arabidopsis and rice transgenic systems, GmRD22 overexpression markedly elevated lignin contents, evincing its protective properties in soybean under salt stress (Wang et al. 2012).

Besides CW strengthening, the hydrophobic cuticle is also an important barrier against dehydration, as its waterproofing property could reduce transpirational water loss during salinity stress (Ziv et al. 2018). EARLI (early Arabidopsis aluminium-induced gene1) is a CW-localized protein that contains lipid transfer protein (LTP) motifs (Bubier and Schlappi 2004), which are involved in cutin biosynthesis and membrane formation (Kader 1996). In soybean, GsEARLI17 encodes a hybrid proline-rich protein (HyPRP) (Liu et al. 2015), which is involved in CW reinforcement (Jose-Estanyol and Puigdomenech 2000). Under salt treatment and compared to WT, its overexpression in Arabidopsis led to higher germination rates and healthier cotyledons, while GsEARLI17-overexpressing seedlings had higher rates of leaf opening and greening (Liu et al. 2015). Remarkably, the transgenic line had cuticles up to 167% thicker than those of WT (Liu et al. 2015). This corroborates the role of proline-rich proteins in altering soybean CW structure under salt stress, as proposed by He et al. (2002), where the expression of soybean SbPRP3, encoding a HyPRP with unknown function, was found to be inducible by salinity stress (He et al. 2002).

The growth and functionality of plant cells are constrained by the CW architecture (Lampugnani et al. 2018; Somerville et al. 2004), which is partly underpinned by the cortical microtubule array that directs the arrangement of cellulose and other CW components (Oda 2015). Coumarin, a phytotoxin typically produced by plants to combat pathogens and herbivory (Gnonlonfin et al. 2012; Prats et al. 2007; Sun et al. 2014), has been found to mediate plant growth and development (Lupini et al. 2014). Specifically, it exhibits a dose-dependent effect on Arabidopsis root morphology by indirectly altering the cortical microtubule organization, and hence, the architecture of the root apical meristem (Bruno et al. 2021; Lupini et al. 2014). In soybean, the expression of GmF6′H1, which encodes the enzyme for coumarin biosynthesis, was highly induced by salt stress (Duan et al. 2019). The GmF6′H1-overexpressing transgenic Arabidopsis had higher salt tolerance, along with a higher germination rate and chlorophyll content, produced more siliques and had less growth impairment under NaCl than the WT plants (Duan et al. 2019). Coumarin might play a role in altering the soybean cortical microtubule array, thereby causing adaptive changes in the CW structure to confer salt tolerance. However, since the role of coumarin in soybean CW modification is only implied, future verification is required to characterize the actual changes in CW composition and organization following increased coumarin biosynthesis under salt stress.

Achieving efficient signal transduction to enable rapid acclimation is as crucial as the direct modulation of the CW structure. For instance, the Catharanthus roseus receptor-like kinase (CrRLK1L) subfamily is crucial in regulating cell expansion via spatially and temporally controlled downstream signal transduction when plants undergo development or respond to stresses (Nissen et al. 2016). In soybean, GmCrRLK1L20 encodes a cell membrane-localized FERONIA receptor kinase that mediates Ca2+ signaling (Feng et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2021b). Under salt treatment, soybean hairy roots overexpressing GmCrRLK1L20 had delayed leaf wilt, longer roots, and higher chlorophyll content compared to wild type (Wang et al. 2021b). Additionally, elevated contents of enzymatic and secondary metabolite antioxidants were coupled with a lower MDA level and less cell membrane damage, as indicated by lower membrane permeability in the transgenic line (Wang et al. 2021b). Importantly, CrRLK1L-mediated Ca2+ signaling is activated by changes in pectin structure and polymerization (Lin et al. 2022; Nissen et al. 2016), which are a common feature of both adaptive and maladaptive salt responses in plants (Feng et al. 2018), evincing the critical role of apoplastic modifications in salt stress responses.

After overcoming the salinity-induced osmotic stress, secondary responses at later stages typically involve CW loosening and cell elongation for plants to continue to grow under prolonged salt stress (Voxeur and Hofte 2016). The brassinosteroid (BR) signaling pathway is involved in cellulose deposition (Planas-Riverola et al. 2019), and is activated as a protective response against the stress-induced loss of CW integrity due to imbalanced pectin modification (Wolf et al. 2012). Meanwhile, BIN2 (brassinosteroid-insensitive 2), a negative regulator of BR signaling (Li et al. 2020c), acts as a molecular switch from immediate salt stress responses to growth recovery (Li et al. 2020c). In soybean, GmBIN2 encodes glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), and its expression is induced by exposure to NaCl (Wang et al. 2018a). Under salt treatment, GmBIN2-overexpressing Arabidopsis had a higher germination rate and Ca2+ content, longer root length, and a reduced Na+ content than WT, while GmBIN2 overexpression in soybean hairy roots resulted in lower cell membrane permeability (Wang et al. 2018a). Given that BIN2 inhibits the cellulose biosynthesis required for early salt responses, future studies could examine the temporal control mechanism of GmBIN expressions and verify the downstream gene regulation cascade in soybean CW remodeling.

Past researches on soybean CW remodeling have mainly focused on growth and development (Hong et al. 1987; Ye and Varner 1991), and responses to pests and pathogens (Borkowska et al. 1998; Liu et al. 2017). Proteomic studies have uncovered enzymes that are key to adaptive CW remodeling and responsive to salinity (Rehman et al. 2022; Sobhanian et al. 2010), but the underlying genes have yet to be determined. Moreover, CW-modifying protein gene families, including those involved in CW loosening, cellulose biosynthesis and pectin modification, have been identified and characterized in genome-wide analyses (Feng et al. 2022; Nawaz et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2021b). Given that CW remodelling is closely tied to salt-induced growth regulation (Julkowska and Testerink 2015), future study could first finely characterize the relative growth rate of different soybean organs and the salt-induced sequential changes in cell wall structure, then investigate the underlying genetic components using functional verification.

Transcription regulation

Plants, when subjected to salt stress, undergo extensive transcriptome reprogramming to make physiological and metabolic adjustments to survive the damage caused by the salt (Liu et al. 2019). In the past 20 years, a number of transcriptomic studies have been conducted to identify the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in soybean under salt stress (Table S3). The global transcriptomic view allows researchers to determine transcriptionally the most affected cellular processes or pathways during salt stress.

Transcription factors (TFs) play a key role in salt stress-induced transcriptome reprogramming by activating or repressing their target genes. A number of TFs belonging to various families, including bHLH, bZIP, AP2/ERF, MYB, NAC, and WRKY, have been reported to participate in plant tolerance against abiotic stress such as drought and salinity (Golldack et al. 2011; Khan et al. 2018). In soybean, in the salt-induced DEGs belonging to these same families of transcription factors are also identified in response to salt stress. For instance, 862 TFs clustering mostly in the WRKY, NAC, AP2-EREBP, ZIM, and C2C2 (Zn) CO-like families were identified among the DEGs in salt-treated soybean (Belamkar et al. 2014). For the remaining 1,235 DEGs under salt stress, 117 were identified as TFs and 17 of them were putative members of the MYB family of TFs (Liu et al. 2021b). A single TF can regulate a series of downstream stress-responsive genes and induce comprehensive phenotypic adjustments for salt tolerance (Khan et al. 2018). Therefore, manipulating the expressions of a few salt stress-related TFs could lead to significant improvements in salt tolerance. Summarized in Table 1 are the functional analyses using transgenic plants to characterize the roles of selected TFs that are differentially expressed under salt stress.

Table 1.

A list of functionally verified soybean transcription factors involved in salt tolerance

| Gene | Phenotype | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| bHLH transcription factor | |||

| GmbHLH3 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance | GmbHLH3 regulates the expression of GmCLC1, which in turn retains NaCl in the root to prevent salt damage in the shoot | (Liu et al. 2022) |

| bZIP transcription factors | |||

| GmbZIP1 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis, wheat and tobacco enhances salt tolerance | GmbZIP1 regulates the expressions of ABA- and stress-related genes to mediate the ABA response | (Gao et al. 2011) |

| GmbZIP2 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance | Ectopic expression of GmbZIP2 can enhance the expressions of stress-responsive genes under normal conditions, salt stress, and mannitol treatment | (Yang et al. 2020b) |

| GmbZIP15 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean results in increased salt sensitivity | GmbZIP15 positively regulates the transcription of GmSAHH1 and negatively regulates GmWRKY12 and GmABF1 under abiotic stress | (Zhang et al. 2020a) |

| GmbZIP19 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean results in increased salt sensitivity | GmbZIP19 upregulates ABA-, JA-, ET-, and SA-inducible marker genes by interacting with their promoters but downregulates salt- and drought-responsive genes | (He et al. 2020a) |

| GmbZIP44, GmbZIP62, GmbZIP78 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GmbZIP44, GmbZIP62, and GmbZIP78 mediate ABA signaling by upregulating ABI1 and ABI2 which regulate downstream stress-responsive genes | (Liao et al. 2008c) |

| GmbZIP110 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance | GmbZIP110 alters the expressions of stress-related genes in the ABA-signaling pathway and those related to ion transportation | (Xu et al. 2016) |

| GmbZIP132 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance at germination stage | GmbZIP132 promotes the transcription of stress-responsive genes including RD29B, DREB2A, and P5CS | (Liao et al. 2008a) |

| GmbZIP152 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GmbZIP152 activates antioxidant enzymes and the transcription of biotic and abiotic stress-related marker genes when stressed. GmbZIP152 can bind directly to the promoters of ABA-, JA-, ET-, and SA-inducible genes | (Chai et al. 2022) |

| GmFDL19 | Overexpression in soybean enhances salt tolerance | GmFDL19 reduces Na+ accumulation and enhances expression of ABA- and stress-responsive genes | (Li et al. 2017b) |

| GmTGA13 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance | GmTGA13 mediates ion homeostasis by facilitating K+ and Ca2+ absorption | (Ke et al. 2022) |

| GmTGA17 |

Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance RNAi soybean hairy roots show increased salt sensitivity |

GmTGA17 upregulates ABA-responsive genes and regulates ABA signaling under salt and drought stress | (Li et al. 2019a) |

| Dehydration-responsive element-binding (DREB) proteins | |||

| GmDREB1 | Overexpression in alfalfa enhances salt tolerance | Transgenic alfalfa exhibits a higher level of P5CS transcripts, which is consistent with a higher level of free proline | (Jin et al. 2010) |

| GmDREB2 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GmDREB2 can induce the expressions of downstream genes RD29A and COR15a | (Chen et al. 2007) |

| GmDREB3 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and tobacco enhances salt tolerance | GmDREB3 can bind to DREs and activate downstream genes | (Chen et al. 2009) |

| GmDREB6 | Overexpression in soybean enhances salt tolerance | GmDREB6 can enhance the expression of GmP5CS and increase the proline content when under salt stress | (Nguyen et al. 2019) |

| Ethylene-responsive factors (ERFs) | |||

| GmERF3 | Overexpression in tobacco enhances salt tolerance | GmERF3 can interact with the GCC box and DRE/CRT and activate the associated genes | (Zhang et al. 2009) |

| GmERF4 | Overexpression in tobacco enhances salt tolerance | GmERF4 possesses GCC-box- and DRE/CRT-binding specificities and inhibits the expressions of GCC-box-containing genes | (Zhang et al. 2010) |

| GmERF7 | Overexpression in tobacco enhances salt tolerance | GmERF7 functions as a transcription activator through binding to the GCC box of its target genes | (Zhai et al. 2013) |

| GmERF057, GmERF089 | Overexpression in tobacco enhances salt tolerance | GmERF057 and GmERF089 are induced by salt, drought, ET, SA, JA, and ABA, suggesting that they may be involved in various stress signaling pathways | (Zhang et al. 2008) |

| GmERF75 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance | GmERF75 is induced in SA, JA, and ET treatments, suggesting its role in integrating the signals from SA and ET/JA pathways | (Zhao et al. 2019b) |

| GmERF135 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance | GmERF135 regulates ET and ABA signaling by activating ET-producing genes, AtACO4, AtACS2, and ABA biosynthesis genes, ABA1, ABA2 | (Zhao et al. 2019c) |

| GRAS transcription factor | |||

| GmGRAS37 |

Overexpression in soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance RNAi soybean hairy roots show increased salt sensitivity |

GmGRAS37-overexpressing plants show upregulated GmDREB1, GmNCED3, GmCLC1, GmSOS1, and GmSODs under salt stress, so it can regulate ABA biosynthesis, ion transportation and ROS scavenging | (Wang et al. 2020) |

| Early Flowering 3 | |||

| GmJ |

Overexpression in soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance NIL-j soybean hairy roots show increased salt sensitivity |

J is involved in the regulation of downstream salt-responsive genes, including GmWRKY12, GmWRKY27, GmWRKY54, GmNAC11, and GmSIN1 | (Cheng et al. 2020) |

| MYB transcription factors | |||

| GmMYB12 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GmMYB12 activates gene expressions and enzymatic activities of P5CS, SOD, and POD upon salt stress, and therefore helps maintain the proper levels of proline and ROS | (Wang et al. 2019b) |

| GmMYB12B2 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GmMYB12B2 can increase the expressions of salt stress-responsive genes including DREB2A and RD17 | (Li et al. 2016b) |

| GsMYB15 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GsMYB15 reduces the transcript levels of ABA marker genes (ABIs) and activates several TFs, conferring salt tolerance | (Shen et al. 2018a) |

| GmMYB46 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GmMYB46 induces the expressions of salt-responsive genes, P5CS1, SOD, POD, and NCED3 to turn on salt tolerance mechanisms | (Liu et al. 2021b) |

| GmMYB68 |

Overexpression in soybean enhances salt tolerance RNAi soybean shows increased salt sensitivity |

GmMYB68 activates FBP and P5CR to promote the accumulation of soluble sugars and free proline | (He et al. 2020b) |

| GmMYB76, GmMYB92, GmMYB177 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | All three genes lead to the activation of DREB2A, RD17, and P5CS. In addition, GmMYB76 and GmMYB177 can enhance the expressions of RD29B, ERD10, and COR78 | (Liao et al. 2008b) |

| GmMYB81 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance at germination stage | GmMYB81 regulates stress tolerance together with abiotic stress regulator GmSGF14l | (Bian et al. 2020) |

| GmMYB84 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean enhances salt tolerance | GmMYB84 can bind to the cis-regulatory sequence of GmAKT1 to mediate K+ transport and in turn establish a higher [K+]/[Na+] ratio | (Zhang et al. 2020b) |

| GmMYB118 |

Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance CRISPR-edited soybean shows increased salt sensitivity |

GmMYB118 regulates the expressions of stress-associated genes to reduce ROS and MDA levels under salt and drought stress | (Du et al. 2018) |

| GmMYB133 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GmMYB133 confers salt tolerance through inducing the expression of salt tolerance-related genes including EARL1, MPK3 and AZI1 | (Shan et al. 2021) |

| GmMYB173 |

Overexpression in soybean roots enhances salt tolerance RNAi soybean roots show increased salt sensitivity |

Phosphorylated GmMYB173 has a higher affinity to the promoter of GmCHS5 and facilitates the accumulation of dihydroxy B-ring flavonoids | (Pi et al. 2018) |

| GmMYB183 |

Overexpression in soybean hairy roots shows increased salt sensitivity RNAi soybean hairy roots have enhanced salt tolerance |

GmMYB183 regulates GmCYP81E11 and enhances the accumulation of ononin, which has negative effects on soybean salt tolerance | (Pi et al. 2019) |

| NAC transcription factors | |||

| GmNAC06 |

Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance CRISPR-edited soybean hairy roots show increased salt sensitivity |

GmNAC06 promotes the expressions of GmUBC2 and GmHKT1 to maintain ion homeostasis and mediate oxidative stress responses | (Li et al. 2021b) |

| GmNAC15 | Overexpression in soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance | GmNAC15 regulates osmolyte biosynthesis to eliminate osmotic stress and induces the expressions of stress-responsive genes including GmERF3 and GmWRKY54 | (Li et al. 2018b) |

| GmNAC11 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance | GmNAC11 is involved in the regulation of DREB1A and other stress-associated genes | (Hao et al. 2011) |

| GmNAC20 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GmNAC20 activates the DREB/CBF-COR pathway | (Hao et al. 2011) |

| GmNAC085 | Overexpression in soybean enhances salt tolerance | GmNAC085 enhances the expressions of stress-related genes involved in proline biosynthesis, Na+ transport, and dehydrin accumulation | (Hoang et al. 2021) |

| GmNAC109 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GmNAC109 increases the transcript levels of stress-responsive genes such as DREBs, AREBs, RD29A, and COR15A. ABA-responsive genes, ABIs, and auxin-related genes, AIR3 and ARF2, are also induced | (Yang et al. 2019) |

| GmSIN1 |

Overexpression in soybean enhances salt tolerance RNAi soybeans show increased salt sensitivity |

GmSIN1 enhances the expressions of GmNCED3s and GmRbohBs, forming a positive feed-forward loop to amplify the initial salt stress signal by rapidly accumulating ABA and ROS | (Li et al. 2019b) |

| NF-YA transcription factors | |||

| GmNFYA |

Overexpression in soybean enhances salt tolerance RNAi soybean hairy roots show increased salt sensitivity |

Stress-induced GmNFYA destabilizes the GmFVE-GmHDA13 complex by interacting with GmFVE, resulting in the activation of salt stress-responsive genes by histone acetylation | (Lu et al. 2021) |

| GmNFYA13 |

Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean enhances salt tolerance RNAi soybeans show increased salt sensitivity |

GmNFYA13 can bind to and regulate the transcription of GmSALT3, GmMYB84, GmNCED3, and GmRbohB | (Ma et al. 2020) |

| Plant homeodomain finger protein | |||

| GmPHD2 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GmPHD2 may downregulate several negative regulators of stress response-related genes such as CBF2, STRS1, and STRS2 | (Wei et al. 2009) |

| RAV transcription factor | |||

| GmRAV-03 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | (Zhao et al. 2017) | |

| Trihelix transcription factors | |||

| GmGT-2A, GmGT-2B | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | The two GmGTs induce the stress tolerance genes, STZ/ZAT and DREB2A, and activate antioxidative mechanisms. Furthermore, GmGT-2B can enhance the expressions of ABA-dependent genes including NCED3, LTP3, LTP4 and PAD3 | (Xie et al. 2009) |

| VOZ transcription factor | |||

| GmVOZ1G |

Overexpression in soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance RNAi soybean hairy roots show increased salt sensitivity |

GmVOZ1G enhances the activities of POD and SOD under drought and salt stress | (Li et al. 2020a) |

| WRKY transcription factors | |||

| GmWRKY12 | Overexpression in soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance | The promoter of GmWRKY12 contains cis-acting elements including ABER4, MYB, MYC, GT-1, W-box, GARE, and DPBF, suggesting the role of GmWRKY12 in various stress and hormone responses | (Shi et al. 2018) |

| GmWRKY13 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis leads to increased salt sensitivity | GmWRKY13 upregulates ARF6 to promote lateral root development and ABI1 to mediate ABA response | (Zhou et al. 2008) |

| GmWRKY16 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GmWRKY16 enhances the expressions of WRKY8, KIN1, and RD29A in salt stress | (Ma et al. 2019) |

| GmWRKY27 |

Overexpression in soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance RNAi soybean hairy roots show increased salt sensitivity |

GmWRKY27 interacts with GmMYB174 and inhibits the expression of GmNAC29, which negatively regulates stress tolerance | (Wang et al. 2015) |

| GmWRKY45 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | (Li et al. 2020b) | |

| GmWRKY49 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean enhances salt tolerance | GmWRKY49 can bind directly to the W-box and possibly modulates the expressions of downstream stress-related genes | (Xu et al. 2018) |

| GmWRKY54 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GmWRKY54 regulates the expressions of DREB2A and STZ/Zat10 by binding to the W-boxes in their promoter region | (Zhou et al. 2008) |

| GmWRKY111 | Overexpression in soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance | (Xu et al. 2014) | |

| C2H2-type zinc finger protein | |||

| GmZAT4 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | GmZAT4 regulates the expressions of ABA-responsive marker genes including RD29A, RD29B, RAB, and ABI | (Sun et al. 2019b) |

Among the 10 groups of GmbZIPs identified in soybean (131 in total), the group A genes were reported to be involved in ABA-dependent stress signaling (Liao et al. 2008c). For example, the overexpression of GmbZIP1 in Arabidopsis upregulated ABA-regulated genes such as ABA INSENSITIVE 1 (ABI1), ABI2, RESPONSIVE TO DESICCATION 29B (RD29B), and RESPONSIVE TO ABA 18 (Rab18), and downregulated POTASSIUM CHANNEL IN ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA 1 (KAT1) and KAT2, to promote stomatal closure upon salt stress (Gao et al. 2011). The overexpression of GmFDL19 upregulated another subset of stress-responsive genes including the ion transporters GmCHX1 and GmNHX1, and some ABA-responsive TFs such as GmbZIP1, GmNAC11, and GmNAC29 to activate salt tolerance mechanisms (Li et al. 2017b). Thus, these two groups of genes may enhance salt tolerance in an ABA-dependent manner. On the other hand, some non-group A members were determined to be negative regulators of ABA signaling in salt stress. Transgenic plants overexpressing a group D member GmbZIP132, a group S member GmbZIP44, a group C member GmbZIP62, or a group G member GmbZIP78 showed reduced ABA sensitivity but enhanced salt tolerance (Liao et al. 2008a, 2008c). Similar observations were also reported in three MYB genes GmMYB76, GmMYB92, and GmMYB177, which also negatively regulate ABA signaling for soybean salt tolerance (Liao et al. 2008c). Besides, GsMYB15-overexpressing Arabidopsis repressed the expressions of the marker genes in the ABA pathway, AtABI1 and AtABI2, and showed improved salt tolerance, so GsMYB15 may also participate in the ABA-dependent pathway in salt stress responses (Shen et al. 2018a).

There are around 180 members in the NAM/ATAF/CUC (NAC) family of TF-encoding genes in the soybean genome (Melo et al. 2018). A number of them have been characterized to play roles in salt stress tolerance (Table 1). Some members in the NAC family also play roles in the ABA pathway. For example, the overexpression of GmNAC109 resulted in the upregulation of ABA-responsive genes, ABI1 and ABI5, conferring increased sensitivity to ABA and greater tolerance against salt stress (Yang et al. 2019). SALT INDUCED NAC1 (GmSIN1) regulates the ABA biosynthesis genes, 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenases (GmNCED3s), which in turn leads to the rapid accumulation of ABA and enhances salt tolerance by amplifying the initial salt stress signal (Li et al. 2019b).

At the same time, the ethylene responsive factor (ERF) family of TFs are also involved in ABA and multiple phytohormone signaling pathways upon salt stress. The induction of GmERF75 by exogenous salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) suggested that GmERF75 may integrate signals form the SA and ET/JA pathways and positively regulate salt stress responses (Zhao et al. 2019b). GmERF057 and GmERF089 were also induced by salt, drought, ET, SA, JA, and ABA, implying their participation in various phytohormone-mediated signaling pathways in enhancing salt tolerance (Zhang et al. 2008). Meanwhile, the ET biosynthesis genes, AtACO4 and AtACS2, and ABA biosynthesis genes, ABA1 and ABA2, were upregulated in transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing GmERF135, indicating that GmERF135 modulates salt tolerance by regulating both ET and ABA signaling pathways (Zhao et al. 2019c).

The WRKY TFs are characterized by the core amino acid sequence, WRKYGQK, which binds specifically to the W-box sequence (T)TTGAC(C/T) in the promoters of their target genes (Zhou et al. 2008). GmWRKY54 can regulate the expressions of DREB2A and STZ/Zat10 and induce stress tolerance mechanisms. GmWRKY49 can also bind directly to the W-box in its target gene promoters and possibly modulate the expressions of downstream stress-related genes, leading to enhanced salt tolerance in GmWRKY49-overexpressing plants (Xu et al. 2018).

Signal transduction

When plants sense salt stress, multiple signal transduction pathways, such as the phytohormone-mediated, Ca2+-dependent, and phosphatidylinositol signals, are initiated (Liu et al. 2019). Regulators such as transcription factors are activated and the gene expressions of downstream stress-responsive genes are then changed to induce salt tolerance mechanisms and help plants combat salt stress. In soybean, the Ca2+-mediated as well as ABA-dependent pathways related to salt stress are most extensively documented. Components in the pathways involved in soybean salt tolerance and their functional studies are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

A list of functionally verified components of the Ca2+-mediated and ABA-dependent pathways involved in salt tolerance in soybean

| Putative function | Gene | Role in salt tolerance | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ca2+-mediated pathway | |||

| P-type II Ca2+ ATPase | GsACA1 | Overexpression in alfalfa enhances salt tolerance | (Sun et al. 2016) |

| Calmodulin | GmCam4 |

Overexpression in soybean enhances salt tolerance Silencing in soybean leads to increased salt sensitivity |

(Rao et al. 2014) |

| Calcineurin B-like protein | GmCBL1 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | (Li et al. 2012) |

| Calcineurin B-like protein | GmCBL4 | Overexpression in soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance | (Li et al. 2022a) |

| Calmodulin-binding protein | GmCBP60A-1 |

Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance RNAi soybean hairy roots show increased salt sensitivity |

(Yu et al. 2021) |

| Calcium-dependent calmodulin-binding receptor-like kinase | GsCBRLK | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean enhances salt tolerance | (Ji et al. 2016b; Yang et al. 2010) |

| Calcium-dependent protein kinase | GmCDPK3 |

Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance RNAi soybean hairy roots show increased salt sensitivity |

(Wang et al. 2019a) |

| Calcineurin B-like protein interacting protein kinase | GmCIPK2 |

Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance RNAi soybean hairy roots show increased salt sensitivity |

(Li et al. 2022a) |

| Calcineurin B-like protein interacting protein kinase | GmCIPK21 |

Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance RNAi soybean hairy roots show increased salt sensitivity |

(Wang et al. 2019a) |

| Calmodulin-like protein | GsCML27 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis leads to increased salt sensitivity | (Chen et al. 2015a) |

| Calcineurin B-like protein-interacting protein kinase | GmPKS4 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance | (Ketehouli et al. 2021) |

| ABA-mediated pathway | |||

| Drought-induced protein | GmDi19-5 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis shows increased salt and ABA sensitivities | (Feng et al. 2015) |

| F-box protein | GmFBX176 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis shows increased salt sensitivity and reduced ABA sensitivity | (Yu et al. 2020) |

| Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | GmG6PH7 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance | (Jin et al. 2010) |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase | GmMMK1 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots leads to increased salt sensitivity | (Liao et al. 2021) |

| Nodule autoregulation receptor kinase | GmNARK | Overexpression in Arabidopsis leads to increased salt and ABA sensitivities | (Cheng et al. 2018) |

| U-box E3-ubiquitin ligase | GmPUB21 |

Overexpression in tobacco leads to increased salt sensitivity Knock-down soybean shows increased salt sensitivity |

(Yang et al. 2022) |

| Receptor-like cytoplasmic serine/threonine protein kinase | GsRLCK | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance and reduces ABA sensitivity | (Sun et al. 2013a) |

| Stress-associated protein | GmSAP16 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance and ABA sensitivity | (Zhang et al. 2019b) |

| S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 | GmSK1 | Overexpression in tobacco enhances salt tolerance | (Chen et al. 2018b) |

| Salt tolerance 1 | GmST1 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt tolerance and ABA sensitivity | (Ren et al. 2016) |

| With No Lysine serine-threonine kinase | GmWNK1 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis enhances salt and ABA tolerance | (Wang et al. 2011b) |

| Inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase | Gs5PTase8 | Overexpression in Arabidopsis and soybean hairy roots enhances salt tolerance | (Jia et al. 2020) |

Ca2+-mediated pathway

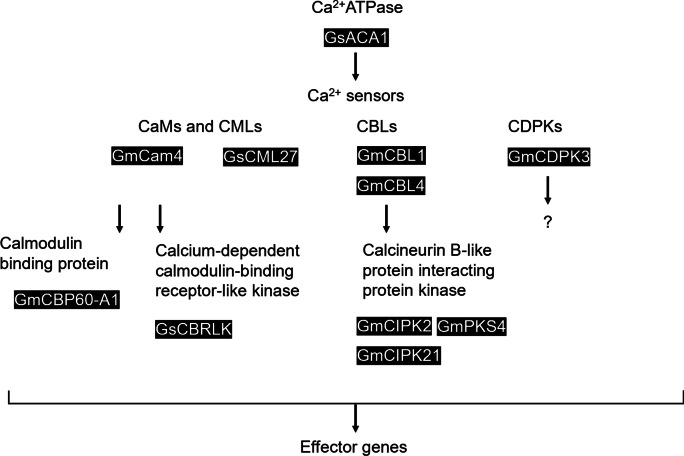

When salt stress is detected, Ca2+ serves as one of the secondary messengers to trigger a series of sequential responses (Phang et al. 2008). Its cytosolic concentration is controlled tightly by Ca2+ transporters such as Ca2+ ATPase. One good example is GsACA1 detailed in a previous section (Sun et al. 2016) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of Ca2+-mediated pathway involve in salt stress in soybean. Upon salt stress, Ca2+ATPase regulate cytosolic Ca2+ level. Ca2+ signals are amplified and transmitted by Ca2+ sensors including calmodulins (CaMs), calmodulin-like proteins (CMLs), calcineurin B-like proteins (CBLs), and calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPKs). Through interacting with their associated interacting proteins, downstream effectors genes are subsequentially activated to give physiological response countering salt stress. Black boxes indicate functionally verified genes in the Ca2+-mediated pathway involve in salt tolerance in soybean