Abstract

Introduction

Prophylactic total gastrectomy (PTG) can eliminate gastric cancer risk and is recommended in carriers of a germline CDH1 pathogenic variant. PTG has established risks and potential life-long morbidity. Decision-making regarding PTG is complex and not well-understood.

Methods

Individuals with germline CDH1 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants who underwent surveillance endoscopy and recommended for PTG were evaluated. Factors associated with decision to pursue PTG (PTGpos) or not (PTGneg) were queried. A decision-regret survey was administered to patients who elected PTG.

Results

Decision-making was assessed in 120 patients. PTGpos patients (63%, 76/120) were younger than PTGneg (median 45 vs 58 years) and more often had a strong family history of gastric cancer (80.3% vs 34.1%). PTGpos patients reported decision-making based on family history more often and decided soon after diagnosis (8 vs 27 months) compared to PTGneg. Negative endoscopic surveillance results were more common among PTGneg patients. Age >60, male sex, and longer time to decision were associated with deferring PTG. Strong family history, a family member who died of gastric cancer, and carcinoma on endoscopic biopsies were associated with decision to pursue PTG. In the PTGpos group, 30 patients (43%) reported regret which was associated with occurrence of a postoperative complication and no carcinoma detected on final pathology.

Conclusion

The decision to undergo PTG is influenced by family cancer history and surveillance endoscopy results. Regret is associated with surgical complications and pathologic absence of cancer. Individual cancer-risk assessment is necessary to improve pre-operative counseling and inform the decision-making process.

Keywords: Surgical Oncology, Surgical Procedures-Operative, Clinical Decision-Making, Digestive System Neoplasms, Genetic Predisposition to Disease

Précis:

Among patients with germline CDH1 variants the decision to proceed with prophylactic total gastrectomy is driven by family history of gastric cancer and presence of occult carcinoma on surveillance endoscopy; regret was associated with post-operative complications and absence of cancer upon gastrectomy.

Introduction

Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) syndrome is most often caused by germline loss-of-function variants in the CDH1 gene (OMIM 192090). The CDH1 gene encodes the transmembrane protein E-cadherin, which is found in epithelial adherens junctions and is involved in suppressing tumor invasion through cell signaling and intercellular adhesion.[1 2] CDH1 variant carriers have an estimated lifetime risk of 25-42% for developing diffuse-type gastric cancer.[3 4] The lack of a sensitive gastric cancer surveillance modality and the inability to provide patient-specific disease penetrance estimates both contribute to the recommendation for prophylactic total gastrectomy (PTG). Clinical practice guidelines recommend PTG as an early adult (age 20-30 years) for patients who carry pathogenic or likely pathogenic CDH1 variants.[5] Annual endoscopic surveillance with random biopsies aimed at sampling the gastric mucosa for early signet ring carcinoma cells (SRCC) is recommended in patients who defer, or who are not candidates for, PTG.[5]

The goal of PTG is to eliminate the risk of clinically advanced gastric cancer by completely removing gastric mucosa. However, this is a potentially morbid operation with postoperative complication rates reported at 10%, and the likelihood of chronic sequelae.[6-8] Perioperative mortality is reported from 1% to as much as 6% in a recent meta-analysis.[9 10] Post-gastrectomy patients experience a lifetime of disrupted macro- and micro-nutrient absorption, reduction in baseline body weight, and potential bone mineral density loss due to calcium malabsorption. Thus, endoscopic gastric surveillance can be considered an alternative to PTG, however evidence supporting its safety and effectiveness is limited. A potential advantage of surveillance is to allow patients time for informed decision making and to detect progression of early cancers.[11 12] The risks and benefits of cancer surveillance weighed against the acute and chronic sequelae of PTG present a decision-making dilemma for affected patients. It is unknown how these factors, and others, might influence a patient’s decision to proceed with PTG after being diagnosed with a germline CDH1 variant.

The paucity of high-level data to inform individual gastric cancer risk, the chronic sequelae of prophylactic gastrectomy, and the undetermined safety profile of enhanced cancer surveillance results in a complex decision-making process for individuals with germline CDH1 variants. Qualitative investigations have probed individuals’ thought processes through interviews and surveys to understand patient-specific circumstances that lead to a decision to proceed with PTG.[13-17] However, quantitative data examining factors that influence the decision-making process are unknown. Through objective and subjective data in the form of clinical characteristics, operative outcomes, and patient surveys, we aimed to determine factors that influence a patient’s decision to proceed with PTG. Additionally, we sought to identify factors predictive of decision regret that could improve patient counseling and inform decision-making related to PTG.

Methods

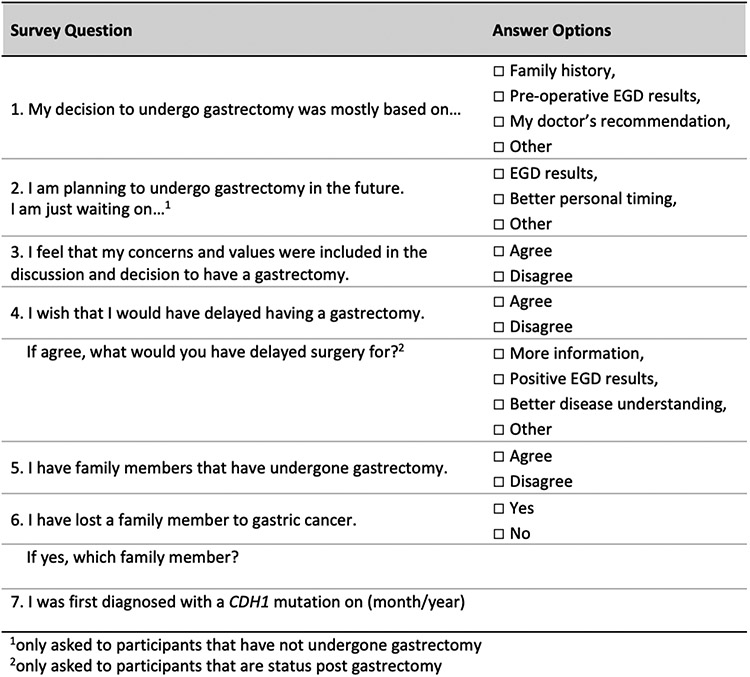

Patients eligible for this analysis were enrolled in a prospective natural history study of hereditary gastric cancers (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT03030404) between January 2017 and January 2021. Our analysis included participants with a germline CDH1 pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) variant that resulted from a genetic testing laboratory that adhered to the American College of Medical Genetics and the Association for Molecular Pathology guidelines for interpretation of sequence variants. Clinical information was collected prospectively and included age, sex, race, and family history of diffuse-type gastric cancer and lobular breast cancer. Strong family history of gastric cancer was defined as two or more 1st or 2nd degree relatives with clinically advanced (stage 1B or greater) gastric adenocarcinoma. All patients with germline CDH1 P/LP variants and family histories of gastric cancer were recommended PTG in accordance with international consensus guidelines.[5] A PTG decision-making survey was administered once to participants by telephone interview sometime between the time they were diagnosed with CDH1 and 4 years post-PTG. (Figure 1).

Figure 1. NIH Prophylactic Total Gastrectomy Decision Making Survey.

Patients were analyzed according to whether they underwent PTG (PTGpos) or not (PTGneg). Clinical and pathologic variables included for analysis were presence of invasive signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) or in situ SRCC on histopathology obtained from endoscopic surveillance biopsies and total gastrectomy. Additional variables from the PTGpos group included perioperative complications (e.g. anastomotic leak, intra-abdominal abscess, and wound complications) and long-term morbidity (e.g. dumping syndrome, bile reflux, iron deficiency anemia). Any comorbid condition present prior to total gastrectomy was not considered a long-term morbidity. Patients in the PTGpos group were administered the Ottawa Decision Regret Scale [18] and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Gastric (FACT-Ga) questionnaires to assess quality of life.[19] Six individuals who elected to proceed with PTG but had not completed the operation at the time of this analysis were included in the PTGpos group for demographic and decision-making analysis, but were excluded from post-operative complications data and decision-regret analyses. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-Square test and continuous variables were compared using either Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test depending on the distribution of the data. Variables found to have a difference with a p-value <0.05 on univariable analysis were included in a multivariable binary logistic regression analysis. All statistical calculations and analysis were performed using SPSS Version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

A total of 120 patients with germline CDH1 P/LP variants were included in the decision-making analysis (Table 1). Participants were predominantly White (89%, 107/120) and female (69%, 83/120) and resided in the Southern (38%, 45/120) and Western (28%, 34/120) United States. A majority of patients (84%, 101/120) had a positive family history of gastric cancer. All 120 individuals underwent pre-operative surveillance upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with gastric biopsies. Intramucosal (invasive) SRCC foci were detected in 36 patients (30%, 36/120) on histopathologic analysis of random surveillance gastric biopsies. Seventy-six individuals (76/120, 63%) subsequently elected to undergo PTG, six of whom had not completed the operation at time of this analysis. Forty-four individuals (37%, 44/120) elected to defer PTG. The proportion of individuals electing to defer PTG had a higher likelihood of negative (non-cancerous) gastric biopsies compared to those who proceeded to PTG (82% vs 63%, p=0.032). Median age at diagnosis of CDH1 P/LP variant was 54 years in the PTGneg group and 45 years in the PTGpos group (p=0.089). Although most patients had a family history of gastric cancer, a strong family history of gastric cancer was more frequent in the PTGpos group than in the PTGneg group (80% vs 34%, p<0.001). Family history of breast cancer was not associated with decision to proceed with PTG.

Table 1.

Demographics of CDH1 variant carriers

| PTGneg (N=44) |

PTGpos (N=76) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median years (range) | 58 (20-75) | 45 (21-67) | P=0.029 |

| <40, N (%) | 12 (27.3) | 28 (36.8) | P=0.027 |

| 40-60, N (%) | 14 (31.8) | 34 (44.7) | |

| >60, N (%) | 18 (40.9) | 14 (18.4) | |

| Sex | P=0.026 | ||

| Female, N (%) | 25 (56.8) | 58 (76.3) | |

| Male, N (%) | 19 (43.2) | 18 (23.7) | |

| Race | P=0.986 | ||

| White, N (%) | 39 (88.6) | 68 (89.5) | |

| Black, N (%) | 2 (4.5) | 3 (3.9) | |

| Other, N (%) | 3 (6.8) | 5 (6.6) | |

| Region of US | P=0.636 | ||

| Midwest, N (%) | 8 (18.2) | 17 (22.4) | |

| Northeast, N (%) | 6 (13.6) | 9 (11.8) | |

| South, N (%) | 15 (34.1) | 30 (39.5) | |

| West, N (%) | 14 (31.8) | 20 (26.3) | |

| Other, N (%) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Family History of GC | |||

| Positive, N (%) | 37 (84.1) | 64 (84.2) | P=0.986 |

| Strong, N (%) | 15 (34.1) | 61 (80.3) | P<0.001 |

| Surveillance Endoscopy | |||

| SRCC−, N (%) | 36 (81.8) | 48 (63.2) | P=0.032 |

| SRCC+, N (%) | 8 (18.2) | 28 (36.8) |

PTG, prophylactic total gastrectomy; US, United States of America; GC, gastric cancer; BC, breast cancer; SRCC, signet ring cell carcinoma.

Factors Associated with Decision-Making

We sought to analyze decision-making with a structured telephone-based survey that was administered once to participants sometime between CDH1 diagnosis and 4 years post-PTG (Figure 1). Participants were allowed to choose more than one factor upon which they based their decision regarding PTG (Table 2). Patients in the PTGpost group made the decision about whether to proceed with PTG after diagnosis of the CDH1 gene variant sooner than those in the PTGneg group (median 8 months vs 27 months, p<0.001). Within 12 months of diagnosis 46 subjects (60%) in the PTGpos group had decided to undergo PTG compared to 7 (15%) in the PTGneg group who made their decision to forego surgery within the same timeframe (p<0.001). Family history of gastric cancer was cited as the primary factor associated with decision for PTG more often in the PTGpos compared to PTGneg group (71% vs 36%, p<0.001). Furthermore, having any relative who died of gastric cancer was more likely in the PTGpos compared to PTGneg group (83% vs 52%, p<0.001). However, a similar proportion of patients in both groups had more than one family member who died of gastric cancer (29% PTGpos vs 25% PTGneg, p=0.641). Individual factors associated with decision for or against PTG were included in a multivariable regression analysis (Figure 2). Age >60 years, male sex, and longer time from diagnosis were significantly associated with declining PTG. A strong family history of gastric cancer (two or more 1st or 2nd degree relatives), having a relative who died of gastric cancer, or having occult SRCC present on endoscopic biopsies were each independent predictors of the decision to proceed with PTG. A family history of gastric cancer was the strongest independent predictor of opting for PTG (OR 4.93, 95% CI 1.75-13.95).

Table 2.

Prophylactic Total Gastrectomy Decision Making Survey Results

| PTGneg (N=44) |

PTGpos (N=76) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at CDH1 diagnosis, median (range) | 54 (17-72) | 45 (20-66) | P=0.089 |

| Time to decision, median months (range) | 27 (8-71) | 8 (1-60) | P<0.001 |

| <12 months, N (%) | 7 (15.9) | 46 (60.5) | P<0.001 |

| ≥12 months, N (%) | 37 (84.1) | 30 (39.5) | |

| Decision for TG | |||

| Family history, N (%) | 16 (36.4) | 54 (71.1) | P<0.001 |

| EGD results, N (%) | 13 (29.5) | 13 (17.1) | P=0.111 |

| Doctor’s Recommendation, N (%) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (17.1) | n/a |

| More information, N (%) | 9 (20.5) | 0 (0.0) | n/a |

| Other, N (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | n/a |

| Concerns/Values Included | P=0.021 | ||

| Yes, N (%) | 41 (93.2) | 76 (100.0) | |

| No, N (%) | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Relative s/p PTG, N (%) | 33 (75.0) | 59 (77.6) | P=0.743 |

| Family Death to GC | |||

| No, N (%) | 21 (47.7) | 13 (17.1) | P<0.001 |

| Yes, N (%) | 23 (52.3) | 63 (82.9) | |

| 1st or 2nd degree relative, N (%) | 19 (43.2) | 51 (67.1) | P=0.010 |

| Multiple Relatives, N (%) | 11 (25.0) | 22 (28.9) | P=0.641 |

PTG, prophylactic total gastrectomy; GC, gastric cancer.

Figure 2. Odds Ratio Plot of Factors Correlating with Decision to Undergo Prophylactic Total Gastrectomy.

FHx, family history; GC, gastric cancer; SRC, signet ring cell carcinoma; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

Decision Regret

Among the individuals who completed PTG, 43% (30/70) expressed some level of regret on the Decision Regret Scale (Table 3). There were no significant differences between patients who did and did not express regret (i.e. age, sex, race, family history, results of endoscopy). Individuals who expressed regret were more likely to have had no evidence of cancer on total gastrectomy explant compared to those without post-operative regret (20% vs 3%, p=0.016) and were more likely to have experienced a post-operative complication (27% vs 5%, p=0.010) (Table 4). Some patients experienced more than one post-operative complication, and each event was included and considered separately in the analysis. Additionally, individuals with regret appeared to have experienced more frequent long-term morbidity (63% vs 43%, p=0.084). The results of the FACT-Ga survey assessing quality of life were similar among those who expressed regret and those who did not.

Table 3.

Pre-operative Factors Effecting Regret on Prophylactic Total Gastrectomy Decision Making

| No Regret (N=40) |

Any Regret (N=30) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median years (range) | 46 (21-67) | 48 (21-66) | P=0.961 |

| <40 years, N (%) | 12 (30.0) | 11 (36.7) | P=0.769 |

| 40-60 years, N (%) | 19 (47.5) | 14 (46.7) | |

| >60 years, N (%) | 9 (22.5) | 5 (16.7) | |

| Sex | P=0.872 | ||

| Female, N (%) | 30 (75.0) | 23 (76.7) | |

| Male, N (%) | 10 (25.0) | 7 (23.3) | |

| Race | P=0.693 | ||

| White, N (%) | 36 (90.0) | 26 (86.7) | |

| Black, N (%) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Other, N (%) | 2 (5.0) | 3 (10.0) | |

| Region of US | P=0.499 | ||

| Midwest, N (%) | 10 (25.0) | 7 (23.3) | |

| Northeast, N (%) | 4 (10.0) | 4 (13.3) | |

| South, N (%) | 18 (45.0) | 9 (30.0) | |

| West, N (%) | 8 (20.0) | 10 (33.3) | |

| Family History of GC | P=0.583 | ||

| Positive, N (%) | 34 (85.0) | 24 (80.0) | |

| Negative, N (%) | 6 (15.0) | 6 (20.0) | |

| Surveillance Endoscopy | P=0.659 | ||

| SRC−, N (%) | 26 (65.0) | 21 (70.0) | |

| SRC+, N (%) | 14 (35.0) | 9 (30.0) | |

| Time to decision, mean months (range) | 11.1 (1-60) | 12.4 (2-48) | P=0.405 |

| <12 months, N (%) | 26 (65.0) | 18 (60.0) | P=0.668 |

| >12 months, N (%) | 14 (35.0) | 12 (40.0) | |

| Decision for PTG | |||

| Family history, N (%) | 29 (72.5) | 22 (73.3) | P=0.938 |

| EGD results, N (%) | 4 (10.0) | 6 (20.0) | P=0.237 |

| Doctor’s Recommendation, N (%) | 6 (15.0) | 7 (23.3) | P=0.375 |

| More information, N (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | n/a |

| Other, N (%) | 6 (15.0) | 1 (3.3) | P=0.107 |

PTG, prophylactic total gastrectomy; US, United States of America; GC, gastric cancer; SRC, signet ring cell carcinoma; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

Table 4.

Post-operative Factors Effecting Regret on Prophylactic Total Gastrectomy Decision Making

| No Regret (N=40) |

Any Regret (N=30) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrectomy Explant | P=0.016 | ||

| SRC−, N (%) | 1 (2.5) | 6 (20.0) | |

| SRC+, N (%) | 39 (97.5) | 24 (80.0) | |

| Perioperative Complications, N (%) | 2 (5.0) | 8 (26.7) | P=0.010 |

| Anastomotic leak, N (%) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (10.0) | P=0.181 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess, N (%) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (6.7) | P=0.394 |

| Pleural effusion, N (%) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (13.3) | n/a |

| Wound complication, N (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.7) | n/a |

| Long Term Morbidity, N (%) | 17 (42.5) | 19 (63.3) | P=0.084 |

| Dumping syndrome, N (%) | 7 (17.5) | 5 (16.7) | P=0.927 |

| Reflux, N (%) | 3 (7.5) | 5 (16.7) | P=0.233 |

| Dysmotility, N (%) | 5 (12.5) | 2 (6.7) | P=0.421 |

| Jejunostomy tube dependence, N (%) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (10.0) | P=0.181 |

| Underweight, N (%) | 7 (17.5) | 6 (20.0) | P=0.790 |

| Iron deficiency anemia, N (%) | 6 (15.0) | 3 (10.0) | P=0.536 |

| Osteopenia, N (%) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (3.3) | P=0.733 |

| Osteoporosis, N (%) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | n/a |

| Ouality of Life, mean ± SD* | 128.1 ± 12.3 | 120.5 ± 22.6 | P=0.376 |

Quality of life measured using the Fact-Ga survey

SRC, signet ring cell carcinoma; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

In this analysis of individuals with germline CDH1 P/LP variants, we identified factors associated with the decision to proceed with PTG. Patients reported their decision to undergo PTG was based most often on a family history of gastric cancer, especially if a relative had died of the disease. Moreover, the finding of occult signet ring cell carcinoma on surveillance endoscopy was an independent predictor of the choice for PTG. Further, we found that younger and female patients were more likely to choose PTG. Patients who decided to complete PTG often did so within a year of diagnosis of their CDH1 variant. Finally, we found that decision regret related to PTG was common, and that regret was associated with absence of cancer in the total gastrectomy specimen and the occurrence of a post-operative complication.

International consensus treatment guidelines recommend PTG in affected individuals starting at age 20 years.[5] This guideline likely exists, in part, because of the cumulative risk of gastric cancer over one’s lifetime. Additionally, younger patients are assumed to recover from total gastrectomy more easily than older patients and are considered likely to adapt to the major lifestyle changes associated with PTG. Therefore, our finding that patients who proceed to gastrectomy tend to be younger is not surprising. Aside from younger age, we showed that women chose PTG more often than men. However, the entire cohort of patients was predominantly female. These results may reflect ascertainment bias, and thus should be interpreted with caution.

The high risk of developing a notoriously aggressive cancer is anxiety-provoking and likely to have a major influence on decision making. Our results indicate that the decision to pursue PTG was often based on family history of gastric cancer, which was anticipated and is consistent with prior qualitative interview based reports.[16 17] However, we observed significant differences in decision-making based on extent of family history of gastric cancer. It was unexpected that 84% of patients who chose not to proceed with PTG also had some family history of gastric cancer. In addition, about half of these individuals had a family death due to gastric cancer, and 25% had multiple relatives who died. Furthermore, the proportion of patients who did not undergo PTG who had a family death was significantly lower compared to the PTGpos group, and the PTGpos group had a higher proportion of patients who had a 1st or 2nd degree relative die from gastric cancer. Although there are these nuanced differences in the rates of family death between groups, the rates in both groups are nonetheless striking because they support the variability and individuality of decision-making. Among individuals who elected for PTG the rate of those who cited their family history as a motivating factor for their decision was double those who deferred PTG. A simple conclusion would be that more relatives in a family with gastric cancer results in higher rates of choosing PTG.

Whereas an individual’s family history of gastric cancer cannot be altered, the rate of post-operative complications due to PTG can. We hypothesized that patients who experienced post-operative complications or long-term morbidity following total gastrectomy would experience some level of regret, which was subsequently borne out in our analysis. Women at increased risk of breast cancer due to the presence of a germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 variant who undergo bilateral prophylactic mastectomy express regret less frequently overall compared to patients in our study.[20 21] However, similar to our results, women who experience any regret following mastectomy were more likely to have had a complication.[20] In our study, there were four individuals who experienced a surgical site infection and three with esophago-jejunal anastomotic leaks. In the setting of prophylactic or risk-reducing surgery, it would seem imperative to prevent or minimize any complications based on the perceived choice for operation. Based on our findings, it seems prudent to fully inform and counsel patients on the risks of surgery as well as the individual surgeon or hospital complication rates following PTG.

An alternative to risk-reducing surgery in CDH1 P/LP variant carriers is regular endoscopic gastric surveillance with random mucosal sampling. Potential benefits of endoscopic surveillance include its very low complication rate, especially when compared to PTG, and the ability to keep one’s stomach. A major unknown of endoscopic surveillance is its safety profile and the potential to miss an advanced cancer when actually present, a so-called false negative finding. Individuals with germline CDH1 variants, especially those with a family history of gastric cancer, must weigh the risk of missing a potentially curative cancer with endoscopy against the life-long morbidity of PTG. Our study demonstrated that patients who chose to forego PTG were more likely to have negative (normal) findings on endoscopic surveillance. Interestingly, we also found that patients who elected for PTG and had no cancer reported in the gastrectomy specimen reported regret more often than patients who had occult cancer in their stomachs. It seems intuitive that the decision to pursue PTG is a logical next step when occult cancer is found on endoscopy; it follows that the lack of cancer on a total gastrectomy specimen leads one to reconsider the decision to undertake a potentially high-risk operation. However, the lack of positive (cancer) findings on pathology simply mean SRCC were not detected but does not mean they are truly absent. That these patients expressed regret more frequently reveals the emotional weight of detecting cancer. Even though SRCC are present in greater than 90% of these patients, inability to detect them on histopathological evaluation may trigger regret due to expectations communicated preoperatively. Furthermore, although it is possible to improve the detection rate of occult SRCC at the time of endoscopic surveillance, increasing the rate of detection alone may only serve to increase the number of patients who choose PTG.[22] The problem remains determining which patients with CDH1 P/LP variants will develop clinically relevant, advanced gastric cancer. The estimated lifetime risk of diffuse-type gastric cancer is 25-42%, which means that most CDH1 variant carriers are unlikely to develop advanced gastric cancer.[3 4]

There are inherent limitations to studying a rare population such as limited sample size, ascertainment bias, treatment heterogeneity, and length of follow-up. We derived our data from a large, prospective study of CDH1 variant carriers that included clinical, pathologic, and outcomes data related to prophylactic total gastrectomy. Patients’ survey responses about what factors influenced their decisions were subject to recall bias, which could have been eliminated with questions administered in real time. Furthermore, decision regret is likely dynamic and thus impacted by when regret is assessed. Longitudinal assessment of decision regret could provide more insight into this complex process.

Conclusions

Among individuals with germline CDH1 variants at increased risk for diffuse-type gastric cancer, young age, female sex, and family history of gastric cancer are associated with a higher likelihood of choosing PTG. Those who proceed to PTG are more likely to do so within one year of diagnosis of CDH1 variant and if endoscopic gastric surveillance reveals occult cancer. Decision regret occurs in individuals who undergo PTG and is associated with post-operative complications and lack of cancer found on final pathology. These data provide valuable insight for consideration by patients and physicians during management discussions about this hereditary cancer syndrome. Informed decision making will be supported by better understanding of individual cancer risk and biologic behavior of early gastric cancer lesions in carriers of germline CDH1 variants.

What is already known on this topic:

CDH1 variant carriers are presented with high risk of gastric cancer and the difficult choice of life-altering prophylactic total gastrectomy.

What this study adds:

This analysis adds important insight into the factors patients weigh when making their decision about prophylactic total gastrectomy, and which factors are associated with post procedure regret.

How this study might affect further research and practice:

These data will assist both patients and clinicians to make informed decisions regarding endoscopic surveillance and prophylactic total gastrectomy. This study also highlights the need for further research into whom among CDH1 variant carriers will progress to advanced gastric cancer and how to optimize clinical management.

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to the patients enrolled in our study of hereditary gastric cancer syndromes.

Funding:

This study was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

Ethics Approval Statement: This study was approved by the National Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1.Aberle H, Schwartz H, Kemler R. Cadherin-catenin complex: protein interactions and their implications for cadherin function. J Cell Biochem 1996;61(4):514–23 doi: [published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caldeira J, Figueiredo J, Brás-Pereira C, Carneiro P, Moreira AM, Pinto MT, Relvas JB, Carneiro F, Barbosa M, Casares F, Janody F, Seruca R. E-cadherin-defective gastric cancer cells depend on Laminin to survive and invade. Hum Mol Genet 2015;24(20):5891–900 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv312[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts ME, Ranola JMO, Marshall ML, Susswein LR, Graceffo S, Bohnert K, Tsai G, Klein RT, Hruska KS, Shirts BH. Comparison of CDH1 Penetrance Estimates in Clinically Ascertained Families vs Families Ascertained for Multiple Gastric Cancers. JAMA Oncol 2019;5(9):1325–31 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1208[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xicola RM, Li S, Rodriguez N, Reinecke P, Karam R, Speare V, Black MH, LaDuca H, Llor X. Clinical features and cancer risk in families with pathogenic CDH1 variants irrespective of clinical criteria. J Med Genet 2019;56(12):838–43 doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2019-105991[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blair VR, McLeod M, Carneiro F, Coit DG, D'Addario JL, van Dieren JM, Harris KL, Hoogerbrugge N, Oliveira C, van der Post RS, Arnold J, Benusiglio PR, Bisseling TM, Boussioutas A, Cats A, Charlton A, Schreiber KEC, Davis JL, Pietro MD, Fitzgerald RC, Ford JM, Gamet K, Gullo I, Hardwick RH, Huntsman DG, Kaurah P, Kupfer SS, Latchford A, Mansfield PF, Nakajima T, Parry S, Rossaak J, Sugimura H, Svrcek M, Tischkowitz M, Ushijima T, Yamada H, Yang HK, Claydon A, Figueiredo J, Paringatai K, Seruca R, Bougen-Zhukov N, Brew T, Busija S, Carneiro P, DeGregorio L, Fisher H, Gardner E, Godwin TD, Holm KN, Humar B, Lintott CJ, Monroe EC, Muller MD, Norero E, Nouri Y, Paredes J, Sanches JM, Schulpen E, Ribeiro AS, Sporle A, Whitworth J, Zhang L, Reeve AE, Guilford P. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated clinical practice guidelines. Lancet Oncol 2020;21(8):e386–e97 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30219-9[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Kaaij RT, van Kessel JP, van Dieren JM, Snaebjornsson P, Balagué O, van Coevorden F, van der Kolk LE, Sikorska K, Cats A, van Sandick JW. Outcomes after prophylactic gastrectomy for hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Br J Surg 2018;105(2):e176–e82 doi: 10.1002/bjs.10754[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Worster E, Liu X, Richardson S, Hardwick RH, Dwerryhouse S, Caldas C, Fitzgerald RC. The impact of prophylactic total gastrectomy on health-related quality of life: a prospective cohort study. Ann Surg 2014;260(1):87–93 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000446[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muir J, Aronson M, Esplen MJ, Pollett A, Swallow CJ. Prophylactic Total Gastrectomy: a Prospective Cohort Study of Long-Term Impact on Quality of Life. J Gastrointest Surg 2016;20(12):1950–58 doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3287-8[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vos EL, Salo-Mullen EE, Tang LH, Schattner M, Yoon SS, Gerdes H, Markowitz AJ, Mandelker D, Janjigian Y, Offitt K, Coit DG, Stadler ZK, Strong VE. Indications for Total Gastrectomy in CDH1 Mutation Carriers and Outcomes of Risk-Reducing Minimally Invasive and Open Gastrectomies. JAMA Surg 2020;155(11):1050–57 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3356[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weindelmayer J, Mengardo V, Veltri A, Torroni L, Zhao E, Verlato G, de Manzoni G. Should we still use prophylactic drain in gastrectomy for cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2020;46(8):1396–403 doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.05.009[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim YC, di Pietro M, O'Donovan M, Richardson S, Debiram I, Dwerryhouse S, Hardwick RH, Tischkowitz M, Caldas C, Ragunath K, Fitzgerald RC. Prospective cohort study assessing outcomes of patients from families fulfilling criteria for hereditary diffuse gastric cancer undergoing endoscopic surveillance. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;80(1):78–87 doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.11.040[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynch HT, Kaurah P, Wirtzfeld D, Rubinstein WS, Weissman S, Lynch JF, Grady W, Wiyrick S, Senz J, Huntsman DG. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: diagnosis, genetic counseling, and prophylactic total gastrectomy. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: diagnosis, genetic counseling, and prophylactic total gastrectomy. Cancer 2008;112(12):2655–63 doi: 10.1002/cncr.23501[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGarragle KM, Hart TL, Swallow C, Brar S, Govindarajan A, Cohen Z, Aronson M. Barriers and facilitators to CDH1 carriers contemplating or undergoing prophylactic total gastrectomy. Fam Cancer 2021;20(2):157–69 doi: 10.1007/s10689-020-00197-y[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hallowell N, Badger S, Richardson S, Caldas C, Hardwick RH, Fitzgerald RC, Lawton J. An investigation of the factors effecting high-risk individuals' decision-making about prophylactic total gastrectomy and surveillance for hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC). Fam Cancer 2016;15(4):665–76 doi: 10.1007/s10689-016-9910-8[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hersperger CL, Boucher J, Theroux R. Paving the Way: A Grounded Theory of Discovery and Decision Making for Individuals With the CDH1 Marker. Oncol Nurs Forum 2020;47(4):446–56 doi: 10.1188/20.ONF.446-456[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoskins C, Tutty E, Purvis R, Shanahan M, Boussioutas A, Forrest L. Young people's experiences of a CDH1 pathogenic variant: Decision-making about gastric cancer risk management. J Genet Couns 2022;31(1):242–51 doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1478[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Calzone K, Fasaye GA, Quillin J. CDH1 variants leading to gastric cancer risk management decision-making experiences in emerging adults: 'I am not ready yet'. J Genet Couns 2021;30(4):1091–104 doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1393[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Connor AM, Drake ER, Fiset V, Graham ID, Laupacis A, Tugwell P. The Ottawa patient decision aids. Eff Clin Pract 1999;2(4):163–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garland SN, Pelletier G, Lawe A, Biagioni BJ, Easaw J, Eliasziw M, Cella D, Bathe OF. Prospective evaluation of the reliability, validity, and minimally important difference of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-gastric (FACT-Ga) quality-of-life instrument. Cancer 2011;117(6):1302–12 doi: 10.1002/cncr.25556[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gahm J, Wickman M, Brandberg Y. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with inherited risk of breast cancer--prevalence of pain and discomfort, impact on sexuality, quality of life and feelings of regret two years after surgery. Breast 2010;19(6):462–9 doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.05.003[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stefanek ME, Helzlsouer KJ, Wilcox PM, Houn F. Predictors of and satisfaction with bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. Prev Med 1995;24(4):412–9 doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1066[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtin BF, Gamble LA, Schueler SA, Ruff SM, Quezado M, Miettinen M, Fasaye GA, Passi M, Hernandez JM, Heller T, Koh C, Davis JL. Enhanced endoscopic detection of occult gastric cancer in carriers of pathogenic CDH1 variants. J Gastroenterol 2021;56(2):139–46 doi: 10.1007/s00535-020-01749-w[published Online First: Epub Date]∣. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]