Abstract

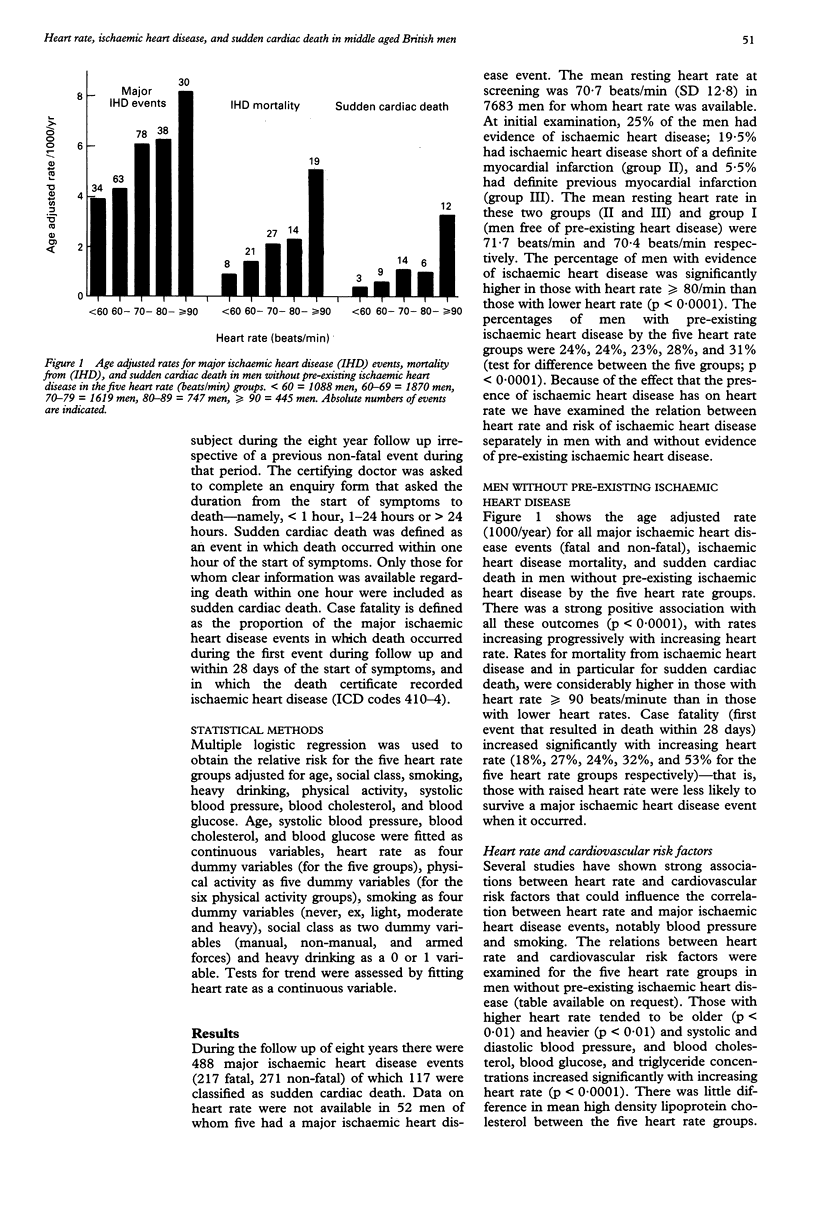

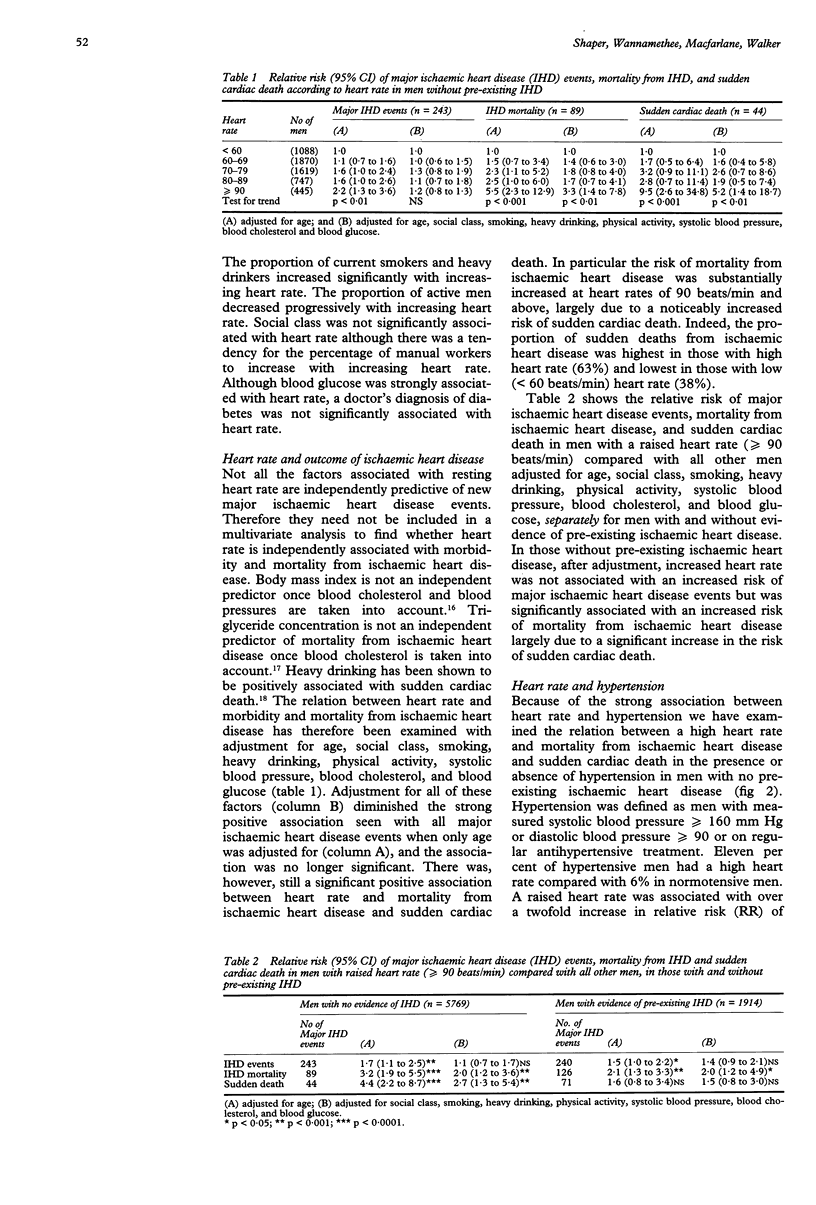

OBJECTIVE--To examine the relation between resting heart rate and new major ischaemic heart disease events in middle aged men with and without pre-existing ischaemic heart disease. DESIGN--Prospective study of a cohort of men with eight years follow up for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality for all men. SETTING--General practices in 24 British towns (the British Regional Heart study). SUBJECTS--7735 men aged 40-59 years drawn at random from the age-sex registers of one general practice in each town. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Major ischaemic heart disease events such as sudden cardiac death, other deaths attributed to ischaemic heart disease, and non-fatal myocardial infarction. RESULTS--During the follow up period of eight years, 488 men had a major ischaemic heart disease event (217 fatal and 271 non-fatal). Of these, 117 were classified as sudden cardiac death (death within one hour of the start of symptoms). The relation between heart rate and risk of all major ischaemic heart disease events, ischaemic heart disease deaths, and sudden cardiac death was examined separately in men with and without pre-existing ischaemic heart disease. In men with no evidence of ischaemic heart disease, there was a strong positive association between resting heart rate and age adjusted rates of all major ischaemic heart disease events (fatal and non-fatal), ischaemic heart disease deaths, and sudden cardiac death. This association remained significant even after adjustment for age, systolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, smoking, social class, heavy drinking, and physical activity, with particularly high risk in those with heart rate > or = 90 beats/min. The increased risk seen in those with increased heart rate was largely due to a significantly increased risk of sudden cardiac death, which was five times higher than in those with heart rate < 60 beats/min. The effect of heart rate on sudden cardiac death was present irrespective of blood pressure or smoking state. In men with pre-existing ischaemic heart disease a positive association was seen between raised heart rate and risk of all major ischaemic heart disease events, ischaemic heart disease death, and sudden cardiac death, but the effect was less noticeable than in men without pre-existing ischaemic heart disease. CONCLUSION--In this study of middle aged British men increased heart rate > or = 90 beats/min) is a risk factor for fatal ischaemic heart disease events but particularly for sudden cardiac death. The effect is not dependent on the presence of other established coronary risk factors and is most clearly seen in men free of pre-existing ischaemic heart disease at initial examination.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Cook D. G., Shaper A. G. Breathlessness, lung function and the risk of heart attack. Eur Heart J. 1988 Nov;9(11):1215–1222. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D. G., Shaper A. G., MacFarlane P. W. Using the WHO (Rose) angina questionnaire in cardiovascular epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1989 Sep;18(3):607–613. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer A. R., Persky V., Stamler J., Paul O., Shekelle R. B., Berkson D. M., Lepper M., Schoenberger J. A., Lindberg H. A. Heart rate as a prognostic factor for coronary heart disease and mortality: findings in three Chicago epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1980 Dec;112(6):736–749. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum R. F. The epidemiology of resting heart rate in a national sample of men and women: associations with hypertension, coronary heart disease, blood pressure, and other cardiovascular risk factors. Am Heart J. 1988 Jul;116(1 Pt 1):163–174. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M. S., Jucha E., Luz Y. Inconsistencies in the correlates of blood pressure and heart rate. J Chronic Dis. 1986;39(4):261–270. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel W. B., Kannel C., Paffenbarger R. S., Jr, Cupples L. A. Heart rate and cardiovascular mortality: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1987 Jun;113(6):1489–1494. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90666-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel W. B., Wilson P., Blair S. N. Epidemiological assessment of the role of physical activity and fitness in development of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 1985 Apr;109(4):876–885. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90653-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAUL O., LEPPER M. H., PHELAN W. H., DUPERTUIS G. W., MACMILLAN A., McKEAN H., PARK H. A longitudinal study of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1963 Jul;28:20–31. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.28.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock S. J., Shaper A. G., Phillips A. N. Concentrations of high density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, and total cholesterol in ischaemic heart disease. BMJ. 1989 Apr 15;298(6679):998–1002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6679.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroll M., Hagerup L. M. Risk factors of myocardial infarction and death in men aged 50 at entry. A ten-year prospective study from the Glostrup population studies. Dan Med Bull. 1977 Dec;24(6):252–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper A. G., Pocock S. J., Walker M., Cohen N. M., Wale C. J., Thomson A. G. British Regional Heart Study: cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged men in 24 towns. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981 Jul 18;283(6285):179–186. doi: 10.1136/bmj.283.6285.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper A. G., Pocock S. J., Walker M., Phillips A. N., Whitehead T. P., Macfarlane P. W. Risk factors for ischaemic heart disease: the prospective phase of the British Regional Heart Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1985 Sep;39(3):197–209. doi: 10.1136/jech.39.3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper A. G., Wannamethee G., Weatherall R. Physical activity and ischaemic heart disease in middle-aged British men. Br Heart J. 1991 Nov;66(5):384–394. doi: 10.1136/hrt.66.5.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelle D. S., Shaper A. G., Whitehead T. P., Bullock D. G., Ashby D., Patel I. Blood lipids in middle-aged British men. Br Heart J. 1983 Mar;49(3):205–213. doi: 10.1136/hrt.49.3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibblin G., Wilhelmsen L., Werkö L. Risk factors for myocardial infarction and death due to ischemic heart disease and other causes. Am J Cardiol. 1975 Apr;35(4):514–522. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(75)90834-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannamethee G., Shaper A. G. Alcohol and sudden cardiac death. Br Heart J. 1992 Nov;68(5):443–448. doi: 10.1136/hrt.68.11.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P. T., Haskell W. L., Vranizan K. M., Blair S. N., Krauss R. M., Superko H. R., Albers J. J., Frey-Hewitt B., Wood P. D. Associations of resting heart rate with concentrations of lipoprotein subfractions in sedentary men. Circulation. 1985 Mar;71(3):441–449. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.71.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]